Abstract

The study of the support of three Armenian manuscripts produced in the 17th century was driven because the possibility of paper support, was considered. The Bible LA 152 and the Gospels LA 193 and LA 253 were made in the Armenian diaspora, in Crimea and Constantinople, respectively. The analytical methods were micro‑Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and micro-ATR spectroscopic imaging, which can identify the main components and their relative proportions. They proved that collagen was present with variable amounts of CaCO3 in the Bible LA 152, Gospels LA 193, and LA 253. Furthermore, CaCO3 is dominant in the Bible LA 152. Other compounds were also identified. In the Bible, LA 152 is a Si-O-based compound, and in Gospel, LA 253 is a cellulose-material. The practical application of the research findings have significant implications for future manuscript studies, underscoring the practical aspects of manuscript production and of carrying out conservation treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Four seventeenth-century Armenian manuscripts (LA 152, LA 193, LA 216, LA 253) took a long path from their places of origin to the Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon. The manuscripts are of religious content and represent the fine art of illuminations. This study analyzed LA 152, LA 193, and LA 253 to determine the writing support and its conditions. LA 152 is a Bible containing the scriptures of the Old and New Testaments, while LA 193 and LA 253 are Gospels with the scriptures of the Four Gospel Books. The text of three manuscripts is written in bolorgir (round minuscule) script in two columns for LA 152 and LA 253 and one for LA 193. The binding of LA 152 (224 × 165 mm) and LA 253 (154 × 114 mm) is made of brown leather with stamped decorations, while that of LA 193 (176 × 133 mm) has decorated silver plaques on the outer faces of its brown leather boards. All the manuscripts are lavishly decorated with full-page narratives, portraits, and ornamental illuminations, Fig. 1.

Seventeenth-century Bible (LA 152) copied in Constantinople, 1623, and seventeenth-century Gospels copied in Crimea (LA 193) and Constantinople (LA 253). The colors used in three manuscripts evident through details of architecture and ornamentation. Gulbenkian Museum, 2019. Folios 981 v, 1002r (LA 152), 111r, 9r (LA 193), 11r, 110r (LA 253). Photos acquired with our Leica microscope with the permission of the Gulbenkian Museum; all rights reserved.

The manuscripts were part of a personal collection of Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian, who acquired them from different intermediaries during his lifetime. After Gulbenkian’s death, these manuscripts and his numerous artworks formed a permanent collection of today’s Gulbenkian Museum. The preserved colophons in LA 152 and LA 193 shed light on their origin and facilitate their dating. LA 253 has no principal colophon preserved; therefore, it was dated through iconographical analysis. LA 152 was copied in the Armenian scriptorium in Constantinople and completed in 1623 by scribe Hakob. It was commissioned by a wealthy Armenian merchant from New Julfa named Khoja Nazar and held in his family for generations. LA 193 was copied and illuminated in Armenian scriptorium in Crimea by famous scribe and artist Nikoghayos. The exact date of its completion is unknown, but the probable period is from 1647 to 1693. LA 253 has no information on its location, date, or producers. However, based on its iconography, the manuscript was attributed to the 17th-century Armenian scriptoria of Constantinople. All three manuscripts are examples of artistic traditions flourishing in Armenian diaspora communities during the early modern period.

Our research began with a thorough analysis of the color palette, a crucial aspect of these seventeenth-century Armenian manuscripts1. The use of precious pigments not only reflects the preferences of the Armenian merchant communities but also suggests the circulation of certain materials between Constantinople, Isfahan/New Julfa, and Crimea. The color palette also serves as a link between medieval traditions and early modern scriptorial practices, as seen in the use of medieval pigments, such as lapis lazuli, vermilion, minium, orpiment, organic reds, mixtures of blue with yellows and organic reds to create greens and purples, lead white, carbon black, and gold. The greens are possibly based on malachite and vergaut. Vergaut, obtained using orpiment and indigo, is the main green in the Bible LA 152 and the Gospels LA 216 and LA 253 (produced in Isfahan and Constantinople, respectively). Malachite is the main green in Gospel LA 193 (Crimea). In the Gospel LA 216, a potentially significant discovery was made by identifying a cobalt blue pigment. This blue was detected in the calf representing the evangelist Luke (f. 141 v) and in the vestment of the evangelist John (f. 213 v), suggesting the use of smalt.

Lapis-lazuli, a precious and symbolic pigment, should be highlighted here. Lapis lazuli is the main blue, except for Gospel LA 253, where azurite is an essential pigment in the illuminations. The other very precious colors are the lake pigments behind reds-pinks-purples, based on carminic acid obtained from a scale insect. Gold is profusely used in the four manuscripts on backgrounds, ornaments, and text1,2.

In this study, we will focus on the support of these colors in the Bible LA 152 and Gospels LA 193 and LA 253 (Supplementary Information 1).

Parchment is a material used as writing support in medieval and early modern manuscript production. For centuries, it was considered a suitable medium for rendering the sophisticated art of calligraphy and illumination. Production of parchment requires elaborate craftsmanship and delicate treatment. Knowledge of parchment production techniques was developed in diverse cultural contexts and environments, representing an overlapping pattern at some point3,4,5.

Through the present study, our group could closely examine the parchment originating from the context of the Armenian written heritage, which urged us to seek information on Armenian parchment making. Thus, we aimed to widen our understanding of local practices and facilitate the interpretation of our analytical results.

Information on Armenian parchment is relatively scarce. Parchment was more likely used as a writing support since the early centuries of Armenian manuscript production. Although paper has been incorporated into Armenian scriptoria since the 10th century6,7, the use of parchment and paper continued simultaneously up to the 17–18th centuries. Parchment was applied to the Bible and Gospel manuscripts to indicate their importance and value. In later centuries, even when paper was widely used in producing manuscripts, extraordinary exemplars were copied on parchment7.

Parchment in Armenia was made from sheep, goat, calf, and other animal hides. Up to a whole flock of sheep was needed to complete some manuscripts. Due to its elaborate manufacture and the quantity of raw material required for a single manuscript, parchment was considered expensive. It was hardly achievable for scriptoria as they had to seek the appropriate amount and good quality and be able to pay the expenses for parchment manufacture and transportation if needed7,8.

Texts on the manufacturing techniques for parchment. The texts attesting to the manufacturing techniques of Armenian parchment have barely been studied7. A recipe compilation published in the 40 s and a paper published in the 70 s are one of the few examples9,10. In the first one, the author transcribes a recipe from Matenadaran manuscript 18499, which is dated by the 15th century (circa 1440) (Supplementary Information 2). Another text found in the same work is a recipe not for parchment but for preparing a paper like parchment. This appears interesting as it may indicate the preference for parchment over paper as a luxurious product (Supplementary Information 2).

The second work reports seven recipes on parchment manufacturing and treatment10. The recipes were retrieved from the Matenadaran manuscripts dated from the 15th to the 18th centuries (Supplementary Information 2). Additionally, a complete text of parchment recipe appears in the catalog of Armenian manuscripts from the St. James repository in Jerusalem, curated by Bishop Bogharian11. This recipe, transcribed from an undated manuscript, gives detailed instructions on how to make parchment (Supplementary Information 2). Other texts on parchment manufacturing in the Armenian context are unknown to us, at least until now. Numerous mentions of parchment recipes indexed in the catalogs of Matenadaran manuscripts are waiting to be revealed and studied thoroughly12. However, the above-mentioned published recipes hint at the local craftsmanship of Armenian parchment. It is possible to resume that the common steps in this process were several soakings of animal hides in lime baths, scraping off the flesh and hair sides with sharp tools, coating the cleaned skins with drying and smoothing substances, and sometimes treating the surface with egg white and linseed oil.

To better understand the Armenian practice of parchment making, perhaps a wider comparative quest within other, especially Near Eastern and Oriental cultures (Coptic, Ethiopic, Syriac, Byzantine, Persian, and Georgian) will be useful, despite the literature on parchment from these cultures also being relatively scarce13,14. Nevertheless, we can trace a dialog between the Armenian and Byzantine practices in the reported Armenian recipes. It can be seen particularly within processes, such as the repetitive soaking of the hides in hydrated lime baths or coating the parchment with egg white and linseed oil. The latter might be an adaptation from a Greek practice13. Although this treatment made the surface of the parchment glossy and smooth, giving a nice appearance, and probably was intended to facilitate the work of the scribe or painter, with time, it caused conservation issues for inks and pigments that deteriorated and detached from the support. This concern was already mentioned in the letter of a Byzantine scholar, Planudes of Constantinople (1260–1330), regarding the vellum. Planudes indicates that the vellum should never be coated with an egg white as it will suffer from it and cause the script and pigments to flake off15. One of the few studies examining the parchment of Byzantine manuscripts of 11–14th centuries reports the coating with egg white and the possible addition of linseed oil to the latter, probably for enhancing the elasticity of dried albumen16. The general image shows that the Greek parchment was mainly treated with organic albuminous and vegetable-origin extract, unlike the Western or Slavic ones. It would be interesting to determine to which extent the Armenian practice has adopted this treatment. It was likely to be understood and interpreted differently in Armenian sources, especially when dealing with several textual recompilations. In this regard, source initiatives and material analyses would be very important.

Regarding Latin sources on parchment making, it is possible to find several texts in medieval treatises (Supplementary Information 2). For instance, a recipe from “Mappae Clavicula” (9th century) advises making parchment from oxhide by keeping it in lime water for three days. Then, the parchment must be stretched, scraped, and dried before use17. Theophilus (12th century) suggests an elaborate washing of goat skins in several lime baths, dehairing, and drying4. Almost the same procedure is described in a recipe from Conradus de Mure (13th century) for a parchment from calf skin3. The manuscript of Jehan le Begue (14th century) indicates how to prepare the surface of the parchment to be suitable for writing and drawing. According to it, the parchment needs to be coated with a paste made of burnt bone and glue, prepared in a detailed way18. More recipes are reported in the referential works by Ronald Reed3,4. In general, in parchment making, the Occidental sources, similar to Oriental ones, mention the exact steps of several lime-bath soakings, dehairing, and drying by stretching but almost omit the finishing step of coating with albumin or vegetable substances.

The Materiality of Parchment. Parchment is a heterogeneous material of organic and inorganic constituents. Its principal constituent is collagen, a fibrous protein and the main organic tissue in an animal’s skin structure19,20,21. During the parchment manufacturing, the collagen composition is altered due to the addition of various organic and inorganic substances. The alkaline treatment with hydrated lime and/or with other additives, such as sodium sulfide, fermented barley or bran, or sour milk, removes the hair and lipids from raw animal skins, making them flexible enough to be stretched in a frame and cleaned furtherly. Hydrated collagen fibers are swollen and can easily rearrange their distribution when stretched to dry. Additional organic and inorganic substances may be applied as finishings for dried skins to make them smooth and suitable for writing. These may include calcium carbonate (chalk), calcium sulfate dihydrate (gypsum), pumice powder, linseed oil, and egg white.

Parchment is prone to degradation due to external/environmental and internal/chemical factors. Its aging depends on the quality of the raw material, manufacturing processes, and preservation conditions. Oxidation, hydrolysis, and biological attack are the main mechanisms of parchment degradation20,22,23.

The physical/chemical analyses of historical and/or modern parchment were mainly performed using optical microscopy, SEM-EDX, XRF, Raman, and ATR-FTIR techniques24. Recently, biomolecular and isotope analyses were also performed in the identification of animal species and provenance of parchment25,26. These analyses almost always detect the presence of calcium carbonate or gypsum (CaSO4⋅2H2O), in addition to proteins and lipids from collagen. Other constituents resulting from treatment processes can also be detected. In case the parchment is degraded, analyses report the aging and degradation agents as well, such as metal carboxylates (soaps) or lipids.

Scientific analyses applied to Armenian parchment are relatively rare. A degraded parchment from a 10th-century Armenian Gospel manuscript was studied by Eliazyan and Keheyan employing FTIR with the aim of its conservation27. The latter was deteriorated from biological attack. A fragment of historical parchment from an Armenian manuscript was studied by Vichi using ATR-FTIR, demonstrating the presence of calcium soaps, calcium carbonate, and lipids and suggesting the application of oil on one of the sides of the parchment24. To the best of our knowledge, there are no further diagnostic studies on parchment from the Armenian cultural context.

The analysis of parchment by infrared spectroscopy. The precision of infrared spectroscopy in identifying protein fingerprints is evident in the characteristic polyamide absorption pattern. This includes the amide I (CO stretching, at circa 1653 cm−1), amide II (CN stretching and NH bending, at circa 1550–1567 cm−1), CN bending at circa 1450 cm−1, and OH/NH stretching at 3400–3000 cm−1 19,28,29, using transmission spectroscopy. Despite the low-intensity signals, the C\H stretching region has proven to be a valuable tool in distinguishing between medieval proteinaceous binders.

The rich information included in an infrared spectrum may further provide precious information on a protein structure, as Barbara Brosky Doyle’s 1975 work discusses30. For more on parchment support and data analysis, see also “Combining infrared spectroscopy with chemometric analysis for the characterization of proteinaceous binders in medieval paints”29.

ATR-FTIR imaging provides insight into studies of cultural heritage showing the advances in chemical specificity and spatial resolution31,32,33,34,35. Discrimination of the origin component and degradation product in space can be observed by ATR-FTIR imaging31. In addition, ATR-FTIR imaging is considered a non-destructive analysis, which benefits the study of fragile samples33,35.

Results

Micro‑Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

The areas analyzed by ATR micro-FTIR were also studied in transmission by micro-FTIR spectroscopy in micro-samples. Smaller fibers of the support were gently compressed.

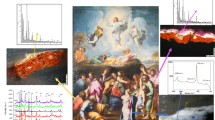

The supports analyzed were from the Bible (LA 152) and two Gospels (LA 193 and LA 253), Figs. 2 and 3. These samples were collected because we considered the possibility of paper support being used. The infrared spectra show that collagen is the support in all three manuscripts. Furthermore, calcium carbonate was also present in different concentrations, as will be discussed next. Other unknowns were detected that will be further discussed in micro-ATR-FTIR spectroscopic imaging.

The spectra were acquired in sample A in three areas where collagen and calcium carbonate (*) are observed. The quantity of calcium carbonate varies in the three areas of analysis. For more details, please see Table 1 and text. Any reuse of these figures requires permission by Melo and Nabais.

The spectra were acquired in sample B, in two areas of analysis, where collagen and calcium carbonate (*) are observed. The quantity of calcium carbonate varies in the three areas of study. For more details, please see Table 1 and text. Any reuse of these figures requires permission by Melo and Nabais.

Table 1 presents the main peaks for collagen, compared with an unaged parchment support (described in the Experimental and Supplementary Information 4). The parchment support is identified in the three manuscripts based on the NH stretching, the amide I and II stretching, and the CN stretching. For the Bible, the amide I and CN are masked by the significant absorption of calcium carbonate. The C-H stretching is more complex. Based on the analysis of parchment glue in ref. 29., the relevant features are the absorptions of the symmetric methyl stretching at 2963 cm−1 and the antisymmetric methylene stretching at 2935 cm−1. For egg white, we have a defined band at 2963 cm-1 and a less defined band at 2935 cm−1 29. Both display an absorption band at 2875 cm−1, assigned to the absorption of the antisymmetric methyl stretching29. In the two Gospels, we observe the methyl stretching at 2961-2 cm−1. Considering this stretching, we cannot exclude the presence of egg white. For the Bible, this peak is at 2955 cm-1. Another band is found at 2923 and 2921 cm−1, for which, at the moment, we cannot find an assignment. The last band is at 2853 and 2852 cm−1, which could match with casein glue or egg yolk.

Calcium carbonate is unequivocally identified in the three manuscripts. The most relevant band for identification is the sharp peak of the carbonate group, with bending at 874–876 cm-1, complemented by the strong absorption of the carbonate ion with a stretching at circa 1410–1425 cm-1. For the Bible, the bending is at 874.6 cm-1, and the Gospels at 874 cm-1 for LA 193 and 875.5 cm-1 for LA 253. The amount of parchment and calcium carbonate varies and is much higher in the Bible. The unknown peaks detected will be discussed in the next section.

Calcium carbonate peaks were also identified in books of hours produced in the 15th century36. The sharp peak of the carbonate group in IL42 is at 874 cm-1; in IL12 and IL21 at 875 cm-1; in IL19 and Ms23 at 876 cm-1; in Ms23, in another fol. at 878 cm-1 In a Renaissance Charter (1512) at 875 cm-1. So, these identification peaks may range from 874–878 cm-1, as observed in the Bible and the Gospels.

Micro-ATR Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic imaging

The parchment samples studied and other supporting information can be found in Supplementary Information 3. Figures 4 to 9 and Figs. S1–S4 in Supplementary Information 3 describe the supports analyzed from the Bible (LA 152) and two Gospels (LA 193 and LA 253).

The resulting micro- ATR FTIR spectra of parchment samples from the Bible (LA 152) and the two Gospels (LA 193 and LA 253) concord with FTIR spectra showing the presence of collagen. The bands of amide I and amide II stretching are distinctly observed in these three samples’ spectra (Fig. 4e, Fig. 5e, and Fig. 7c). The bands of collagen from the sample’s spectra are listed with the reference in Table 2.

The bands relevant to calcium carbonate in the Bible are at 1402–1405 cm-1 and 872–873 cm-1. The front and back sides of the Gospel LA 193 were analyzed. The calcium carbonate bands were observed at 1402–1405 cm-1 and 872 cm-1 in the case of the front side and at 1411–1412 cm-1 and 872 cm-1 in the case of the back side. For the Gospel LA 253, other compounds are possibly interfering, and the peaks are observed at 1411–1412 cm-1 and 874–876 cm-1.

In the Bible, collagen and calcium carbonate are observed. The bands at 1412 and 872 cm-1 are assigned to calcium carbonate and the bands at 1643 and 1543 cm-1 are assigned to collagen, Fig. 4d37. Other strong absorption bands at 1131–33 and 1095–99 cm-1 can be related to the presence of a Si-O, Fig. 4e38. The band at 1095–1099 cm-1 is a good match with a quartz reference with a maximum at 1093.20 cm-1, corresponding to the Si-O antisymmetric stretching plus the vibrations of bridging oxygens38. The first band at ca 1131–33 cm-1, can be assigned to Si–O–Si antisymmetric vibrations of bridging oxygens38. Based on this data, these bands are attributed to a Si-O compound; it could be powdered glass.

a Microscopic image of Bible LA 152 where the black square shows the measurement area by ATR-FTIR imaging. ATR-FTIR spectroscopic images of Bible LA 152 displaying the distribution of (b) Si-O based compound and c collagen. Spectra of (d) Si-O based compound and e collagen with calcium carbonate extracted from the crosspoint of the black lines in the spectroscopic image (b) and (c), respectively. Any reuse of these figures requires permission by Kazarian and Yang.

Micro-ATR FTIR spectroscopic imaging results of the parchment in Gospel LA 193 show the presence of calcium carbonate and collagen, Fig. 5, Figures S2 and S3 in Supplementary Information 337,39. The bands at 1404 and 872 cm-1 are assigned to calcium carbonate (Fig. 5b). The bands at 1635 and 1543 cm-1 are assigned to collagen (Fig. 5c)37.

a Microscopic image of Gospel LA 193 where the black square shows the measurement area by ATR-FTIR imaging. ATR-FTIR spectroscopic images of Gospel LA 193 displaying the distribution of (b) calcium carbonate and c collagen. Spectra of (d) calcium carbonate and e proteinaceous substance extracted from the crosspoint of the black lines in the spectroscopic image (b) and (c), respectively. Any reuse of these figures requires permission by Kazarian and Yang.

The parchment of Gospel LA 253 comprises calcium carbonate, collagen, and cellulose. The bands in the ATR-FTIR are assigned to calcium carbonate and collagen, Fig. 6 and Fig. S4 in Supplementary Information 3. Cellulose was characterized by comparing the infrared spectrum with the online IR spectra database and with a cellulose-based filter paper, Fig. 7 and Fig. S440.

a Microscopic image of Gospel LA 253_1 where the black square shows the measurement area by ATR-FTIR imaging. An ATR-FTIR spectroscopic image of Gospel LA 253_1 displaying the distribution of (b) calcium carbonate. The spectra of (c) calcium carbonate with collagen extracted from the crosspoint of the black lines in the spectroscopic image (b). Any reuse of these figures requires permission by Kazarian and Yang.

a Microscopic image of Gospel LA 253_2 where the black square shows the measurement area by ATR-FTIR imaging. An ATR-FTIR spectroscopic image of Gospel LA 253_2 displaying the distribution of collagen. The spectra of (c) collagen with cellulose extracted from the crosspoint of the black lines in the spectroscopic image (b). Any reuse of these figures requires permission by Kazarian and Yang.

Discussion

This study investigated the parchment support of three seventeenth-century Armenian manuscripts. Contemporary manuscripts in Armenia were made of both paper and parchment. Most were made of paper, while the Bible and Gospel manuscripts were predominantly parchment. This is based on catalog descriptions of Matenadaran and other collections worldwide completed by manuscript experts41,42,43,44. The Gulbenkian Museum’s digital catalog/database (not publicly available) and the museum’s exhibited area describe the manuscripts as made of parchment (vellum, to be precise). This is confirmed by our analysis of the four manuscripts studied using parchment as writing support45. Visual and microscopic examinations revealed that the parchment in Bible LA 152 and Gospel LA 193 is very fine, white-toned, and perfectly made to resemble paper. The parchment in Gospels LA 216 and LA 253 seems thicker and darker than in LA 152 and LA 193. More data on ATR spectra for parchment can be accessed at this database website46.

Infrared spectroscopy corroborates this analysis for Bible LA 152, Gospels LA 216, and LA 253. Other compounds were also identified. In the Bible, a Si-O-based compound, and in Gospel LA 253, a cellulose-based material. The quantity of this cellulose-based material is very high using micro-ATR spectroscopy. The Si-O-based compound, in the form of quartz, was detected both by ATR and transmission (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1 in Supplementary Information 3). It can be applied in the form of a powder, which needs to be further explored.

Furthermore, calcium carbonate is dominant in the Bible (Figs. 2 and 4). In Gospel LA 253, micro-FTIR spectroscopy could not detect the presence of paper, identified by micro-ATR spectroscopy (Fig. 7). The use of cellulose material is intriguing and needs to be further exploited.

Finally, the stretching vibration C-H spectral region is highly relevant, as other tempera (the binding media) can be discussed, although there is some speculation. We identified signals consistent with egg white. These may derive from using eggs in paint binders or as a coating of glair that was applied to the finished parchment to aid ink absorption. We can discuss using a tempera based on egg white for the two Gospels.

Regarding conservation actions, the curator said these manuscripts were probably not restored and had no conservation treatments, at least during the museum’s holding period. Before the museum’s collection, the manuscripts were owned by the collector Calouste Gulbenkian and acquired by him through several intermediaries. Therefore, their conservation/restoration history is unknown. Our findings may be considered for further discussion of the possible conservation treatments.

Methods

Materials and Methods

CaCO3 spectrum was acquired in transmission mode in a diamond cell and was acquired to Roig Farma.

The cellulose-based paper was from a Whatman filter paper.

The parchment was acquired at Musée du parchemin, 4 La Combe du Prieuré, 07100 Annonay, France. Jean-Pierre and Anne-Marie Nicolini manufacture and sell genuine and heritage PARCHEMIN in the tradition of the master parchment makers of the Middle Ages. It was created on 02/04/1983 and closed by 31/12/2020 because Jean-Pierre Nicolini died in December. From 2009 to 2019, we acquired excellent parchment in this museum. More at https://acheterduparchemin.wordpress.com/. Video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ceb0tXv7jks.

More details on the infrared spectra of this parchment are in Supplementary Information 4.

Samples studied

Parchments of one Bible (LA 152) and two Gospels (LA 193 and LA 253) from the collection of Armenian manuscripts in the Gulbenkian Museum were studied. Micro-samples are tiny fragments with lengths in two dimensions.

Micro‑Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

Infrared analyses were performed using a Nicolet Nexus spectrophotometer coupled to a Continuμm microscope (15 × objective) with an MCT-A detector was used. The spectra were collected in transmission mode, in 50 μm2 areas, with a resolution setting of 8 cm−1 and 128 scans, using a Thermo diamond anvil compression cell. CO2 absorption at ca 2400–2300 cm−1 was removed from the acquired spectra (4000–650 cm−1). The spectra were acquired in the spectral range from 4000 to 650 cm-1.

Micro-ATR Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

The ATR-FTIR spectroscopic image analyses were performed using the Agilent 670 spectrometer coupled with a UMA 600 IR microscope. The Agilent 670 spectrometer operates in a continuous scan mode with A 2D FPA (64 × 64-pixel) detector (Santa Barbara, CA, USA). Ge crystal was employed as the IRE connected to the objective of 15X. The IR spectra were collected in the middle infrared region from 3900 to 800 cm-1 with spectral resolution of 4 or 8 cm-1 and 64 scans47.

Data availability

Most of the data on which the conclusions of the manuscript rely is published in this paper, and the full data is available for consultation on request to Tzu-Yi Yang, Hermine Grigoryan, Maria J. Melo and Sergei G. Kazarian.

References

Grigoryan, H. et al. Exceptional illuminated manuscripts at the Gulbenkian museum: the colors of a Bible and three gospels produced in the Armenian diaspora. Heritage 3, 3211–3231 (2023).

Grigoryan, H., Sahakyan, A., Melo, M. J. Vordan Karmir: an attempt to unravel the mystery of Armenian cochineal recipes for paints and inks used in manuscripts. Dyes in History and Archaeology; Kirby, J., Ed. (Archetype Publications, 2023).

Reed R. Ancient Skins, Parchments and Leathers. (Seminar Press, 1972).

Reed R. The nature and making of parchment. (Elmete Press, 1975).

Ryder, M. L. Parchment—its history, manufacture and composition. J. Soc. Archiv. 2, 391–399 (1964).

Matevosyan A. Matenadaran: manuscript No 2679 (in Armenian). Sci. Techn. 4, 1–6 (1982).

Kouymjian D. The Archaeology of the Armenian Manuscript: codicology, paleography, and beyond. In: Calzolari V., editor. Armenian Philology in the Modern Era: From Manuscript to Digital Text. pp. 9–10 (Brill, 2014).

Abrahamyan A. The Manuscript Treasures of Matenadaran (in Armenian). (Matenadaran, 1959).

Harutyunyan A. Paints and Inks According to Old Armenian Manuscripts (in Armenian). pp. 45–77 (Matenadaran, 1941).

Galfayan, K. H. The technology of parchment making according to methods of Armenian craftsmen (in Russian). Artistic heritage: conservation. Res. Restor. 1, 74–79 (1975).

Bogharian N. Grand Catalogue of St. James Manuscripts (in Armenian). Vol. 4., pp. 212–213 (Armenian Convent Printing Press, 1969).

Yeganyan O. General Catalogue of Armenian Manuscripts of the Mashtots Matenadaran (in Armenian). Yeganyan O. et al., editors. Vol. I. (Matenadaran-Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, 1965).

Maniaci M. Codicology. In: Bausi A., editor. Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies: An Introduction. p. 188 (Tredition, 2015).

Maniaci M. Codicology. In: Bausi A., editor. Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies: An Introduction. pp. 72–73 (Tredition, 2015).

Abt, J. & Fusco, M. A. A Byzantine scholar’s letter on the preparation of manuscript vellum. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 28, 61–66 (1989).

Kireyeva, V. Examination of parchment in Byzantine manuscripts. Restaurator 20, 39–47 (1999).

Smith, C. S. & Hawthorne, J. G. Mappae clavicula: a little key to the world of Medieval techniques. Trans. Am. Philos. Soc. 64, 1–128 (1974).

Merrifield M. P. Original treatises dating from the 12th to 18th centuries. Vol. I., pp. 274–278 (John Murray, 1849).

Stuart B. Analytical Techniques in Materials Conservation. pp. 2–3 (Wiley, 2007).

Goffer Z. Archaeological Chemistry. 2nd ed. pp. 321–328 (Wiley, 2007).

Kennedy, C. J. & Wess, T. J. The Structure of Collagen within Parchment – A Review. Restaurator 24, 61–80 (2003).

Ghioni, C. et al. Evidence of a distinct lipid fraction in historical parchments: a potential role in degradation? J. Lipid Res. 46, 2726–2734 (2005).

Možir, A., Cigić, I. K., Marinšek, M. & Strlič, M. Material properties of historic parchment: a reference collection survey. Stud. Conserv. 59, 136–149 (2014).

Vichi A. Degradation of polymers in objects of museum collections at the micro-scale: a novel study with ATR-FTIR spectroscopic imaging. (Imperial College London, 2018).

Fiddyment, S. et al. So you want to do biocodicology? A field guide to the biological analysis of parchment. Herit. Sci. 7, 35 (2019).

Doherty, S., Alexander, M. M., Vnouček, J., Newton, J. & Collins, M. J. Measuring the impact of parchment production on skin collagen stable isotope (δ13C and δ15N) values. STAR. Sci. Technol. Archaeol. Res. 7, 1–12 (2021).

Eliazyan, G., Keheyan, Y., Ajvazyan, A.,. Petrosyan, A. The Conservation and restoration of the Tsughrut Gospel. In: Driscoll M. J., editor. Care and conservation of manuscripts 17. pp. 233–243 (Museum Tusculanum Press, 2021).

Chalmers J. M., Griffiths P. R., editors. Handbook of Vibrational Spectroscopy. Vol. 5., pp. 3400–3424 (Wiley, 2001).

Miguel, C., Lopes, J. A., Clarke, M. & Melo, M. J. Combining infrared spectroscopy with chemometric analysis for the characterization of proteinaceous binders in medieval paints. Chemometr. Intell. Lab. Syst. 19, 32–38 (2012).

Doyle, B. B., Bendit, E. G. & Blout, E. R. Infrared spectroscopy of collagen and collagen-like polypeptides. Biopolymers 14, 937–957 (1975).

Vichi, A., Eliazyan, G. & Kazarian, S. G. Study of the degradation and conservation of historical leather book covers with macro attenuated total reflection–fourier transform infrared spectroscopic imaging. ACS Omega 31, 7150–7157 (2018).

Possenti, E., Colombo, C., Realini, M., Song, C. L. & Kazarian, S. G. Insight into the effects of moisture and layer build-up on the formation of lead soaps using micro-ATR-FTIR spectroscopic imaging of complex painted stratigraphies. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 413, 455–467 (2021).

Liu, G. L. & Kazarian, S. G. Recent advances and applications to cultural heritage using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy and ATR-FTIR spectroscopic imaging. Analyst 147, 1777–1797 (2022).

Gabrieli, F. et al. Revealing the nature and distribution of metal carboxylates in Jackson Pollock’s alchemy (1947) by micro-attenuated total reflection FT-IR spectroscopic imaging. Anal. Chem. 89, 1283–1289 (2017).

Rosi, F., Cartechini, L., Sali, D., Miliani, C. Recent trends in the application of Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy in heritage science: from micro- to non-invasive FT-IR. Phys. Sci. Rev. 4, 20180008 (2019).

Vieira, M., Melo, M. J. & de Carvalho, L. M. Towards a sustainable preservation of medieval colors through the identification of the binding media, the medieval tempera. Sustainability 16, 5027 (2024).

Riaz, T. et al. FTIR analysis of natural and synthetic collagen. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 53, 703–746 (2018).

Abo-Naf, S. M., El Batal, F. H. & Azooz, M. A. Characterization of some glasses in the system SiO2, Na2O·RO by infrared spectroscopy. Mater. Chem. Phys. 77, 846–852 (2003).

Salter, M. A., Perry, C. T. & Smith, A. M. Calcium carbonate production by fish in temperate marine environments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64, 2755–2770 (2019).

Vahur, S., Teearu, A., Peets, P., Joosu, L. & Leito, I. ATR-FT-IR spectral collection of conservation materials in the extended region of 4000-80cm–1. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 11, 3373–3379 (2016).

Yeganyan O. Grand Catalogue of the Armenian Manuscripts of Mashtots Matenadaran. Yeganyan O, et al., editors. Vols. I-VIII. (Matenadaran-Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, 2013).

Der Nersessian S. The Chester Beatty Library, A Catalogue of the Armenian Manuscripts, Vols. I–II (Hodges Figgis & Co, 1958).

Der Nersessian S. Armenian Manuscripts in the Walters Art Gallery. (Walters Art Gallery, 1973).

Baronian S., Conybeare F. C. (1918), Catalogue of the Armenian Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library. (Clarendon Press, 1918).

Doherty, S. P., Henderson, S., Fiddyment, S., Finch, J. & Collins, M. J. Scratching the surface: the use of sheepskin parchment to deter textual erasure in early modern legal deeds. Herit. Sci. 9, 29 (2021).

Charis Theodorakopoulos. Infrared spectra database - Depository of FTIR spectra of IDAP parchments. 2023 [cited 2024 Oct 21]. Available from: https://figshare.northumbria.ac.uk/collections/Infrared_spectra_database_Depository_of_FTIR_spectra_of_IDAP_parchments/6742791/1.

Liu, G. L. & Kazarian, S. G. Characterization and degradation analysis of pigments in paintings by martiros sarian: attenuated total reflection fourier transform infrared spectroscopic imaging and x-ray fluorescence approach. Heritage 6, 6777–6799 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work received financial support from FCT/MCTES (UIDB/50006/2020 DOI 10.54499/UIDB/50006/2020) through national funds. Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation – Armenian Communities Department and National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR). We are deeply grateful to the Director of the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, António Filipe Pimentel, the Deputy Director, João Carvalho Dias, and all the collaborators who supported us during the on-site mission to study the four Armenian manuscripts. Adelaide Miranda and Jorge Rodrigues for their generous collaboration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Y., M.J.M., and P.N coordinated the acquisition and analysis of infrared data. H.G. prepared the introduction, which was finalized by M.J.M. and S.G.K. S.G.K. supervised imaging methodology. M.J.M., P.N., and T.Y. prepared the first version of the Results. All authors contributed to the conclusion, revision, and approval of the article's final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, TY., Grigoryan, H., Nabais, P. et al. Parchment in an Armenian Bible and two Gospels by micro-infrared spectroscopy and micro-ATR spectroscopic imaging. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 598 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02042-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02042-w