Abstract

The Chang Zhen defense area, a critical component of the “Nine Bians and Eleven Zhens,” is strategically significant due to its proximity to Beijing and close association with the Ming Tombs. This study proposes an integrity protection framework through heritage corridor development. Six suitability factors were analyzed using MCR and AHP models. Results indicate that transportation convenience and terrain flatness are pivotal for corridor construction. High-suitability zones largely align with existing Great Wall protection boundaries but extend further into defense-area interiors, including the Ming Tombs. These regions, characterized by flat terrain, infrastructure readiness, and accessibility, present untapped potential for corridor development beyond current heritage zones. The findings underscore the need to prioritize these areas as cultural “windows,” integrating their historical and spatial advantages to enhance coordinated protection between the Great Wall and Ming Tombs. Such efforts would optimize resource utilization while balancing heritage conservation and sustainable development goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Ming Great Wall is the most well-preserved and largest among all the ancient Chinese walls. It was constructed by the Ming government as a defensive system to resist northern nomadic tribes, building upon the walls of the Qin, Han, and Northern Qi dynasties1,2,3. This vast defense system, a complex and well-structured hierarchical system, served as an order zone. In the Ming dynasty, such a large military defense system was constructed and managed according to the “Nine Bians and Eleven Zhens” system. The terms “Bian” (边) and “Zhen” (镇) refer to an ancient Chinese military administrative division, similar to the modern concept of a “province,” but with a stronger military focus4,5. During different periods of the Ming dynasty, the Great Wall was divided into either 9 or 11 “Bians” or “Zhens.” The “Nine Bians” from east to west during the early and mid-Ming periods were: Liaodong Zhen, Ji Zhen, Xuanfu Zhen, Datong Zhen, Shanxi Zhen, Yulin Zhen, Ningxia Zhen, Guyuan Zhen, and Gansu Zhen. The “Eleven Zhens” came into existence in the late Jiajing period, with the establishment of Chang Zhen and Zhenbao Zhen, making up a total of 11 Zhens: the original 9 Zhens plus Chang Zhen and Zhenbao Zhen. In fact, Chang Zhen and Zhenbao Zhen were part of Ji Zhen in the early Ming period, but due to the vast geographical scope of Ji Zhen, it was difficult to govern, so it was divided into three parts: Ji Zhen, Zhenbao Zhen, and Chang Zhen6.

Chang Zhen is located at the junction of the Taihang Mountains and the Yan Mountains to the northwest of Beijing, serving the critical role of guarding the capital and the imperial tombs, making it a strategically important location7. Since the Yuan-Ming wars, the Great Wall settlements in the Chang Zhen area played a crucial military role, and its military and administrative system had undergone numerous changes. After several transitions, the Changping Governor was finally established in the 39th year of the Jiajing reign (1560), marking the official establishment of the Chang Zhen defense area. At this time, Chang Zhen was divided into three sections: Hengling, Juyong, and Huanghua, which included various fortifications, beacon settlements (beacon towers, border forts, enemy observation posts), postal settlements (relay stations, express delivery posts), and the edge walls, along with other subsidiary facilities.

For a long time, there has been a considerable amount of research on the various Great Wall defense areas. However, since Chang Zhen and Zhenbao Zhen were originally part of Ji Zhen, there has been relatively little independent research on them, and most existing studies are included in research on Ji Zhen. Yet, many studies specifically focused on Ji Zhen downplay the discussion of Chang Zhen and Zhenbao Zhen, especially after the latter two became independent. Furthermore, after Zhenbao Zhen became an independent defense zone, it underwent significant construction and is located far from Ji Zhen, making it more autonomous. As a result, there has been a growing body of research dedicated to constructing the Zhenbao Zhen defense system. In contrast, research on Chang Zhen of the Ming Great Wall, one of the “Nine Bians and Eleven Zhens”, is the least among all, with few studies directly focusing on it as an independent subject, showing a clear gap in research.

Although Chang Zhen has received relatively little attention, this does not mean it is unimportant. On the contrary, Chang Zhen is home to globally renowned representative Great Wall cultural heritage sites, such as Badaling, Juyongguan, and Mutianyu, as well as special architectural ruins with high research value8, such as the Nine Eyes Watchtower9 and the Yuntai at Juyongguan10. This has led academic and public focus to be highly concentrated on these specific Great Wall sites, while overlooking the overall construction of the region. The lack of theoretical development in this area has also resulted in inadequate integrity protection of the Great Wall resources in the Chang Zhen defense area. Beyond these well-known points, there is a significant disparity in the preservation and development of other Great Wall sections and large fortresses within the Chang Zhen defense area. Therefore, it is necessary to actively promote the research on the integrity protection of the Chang Zhen defense area under the broader context of the National Great Wall Cultural Park construction.

In the specific context of Great Wall conservation, recent studies have pioneered suitability analysis for corridor planning. For the Ming Great Wall system, its sub-systems—such as the edge wall subsystem, postal subsystem, and beacon tower subsystem—can each be developed into relatively independent heritage corridors. When these sub-systems are interwoven, they form a Great Wall cultural heritage corridor that encompasses more ecological, environmental, social, and economic elements. This aligns with the current goals for the construction of the Great Wall cultural belt and Great Wall cultural parks in China. The concept of a heritage corridor originated in the United States in the 1960s as a conservation strategy for linear cultural landscapes11. It is a product of combining greenways and heritage areas, with particular emphasis on the historical and cultural attributes and multifaceted values within the region. Over the past few decades, it has gained widespread development in the field of ecology12,13. Since the 21st century, its research scope has expanded, gradually incorporating cultural attributes. The research subjects of heritage corridors can include river canyons, canals, roads, railways, and other linear features, or they can be linear corridors that link individual heritage sites of historical significance14,15. This study adopts this method to demonstrate that the Chang Zhen defense area of the Ming Great Wall is not merely a collection of representative Great Wall sites, but rather an integrated whole with potential for heritage corridor development.

In the specific context of Great Wall conservation, some studies pioneered the use of suitability analysis for corridor planning. Concurrently, MCR model, originally developed for habitat isolation assessment, has been increasingly adapted to cultural heritage protection. Such as Li demonstrated its utility in optimizing ecological-cultural network design16, while Chang and Li validated its efficacy for intangible heritage corridor construction in the Yellow River Basin and ecological restoration in mining cities17,18. These applications underscore MCR’s versatility in modeling landscape resistance for human activity-based conservation19. Recent advances in suitability analysis further enhance methodological precision, such as studies integrating MSPA with MCR20, and combing AHP with MCR21. However, a critical gap persists in applying these integrated approaches to the integrity protection of complex military defense systems like the Ming Great Wall, particularly for underrepresented segments such as Chang Zhen.

Moreover, a key scientific problem persists: existing protection frameworks, often focused on individual monuments or linear buffer zones (e.g., the current 500m-3000m protection zones in Beijing), inadequately address the holistic integrity and connectivity required for effective conservation and sustainable utilization of the spatially complex Chang Zhen defense system. This fragmented approach overlooks the synergistic potential between core wall segments, associated fortifications, and the surrounding landscape matrix, particularly areas with high development suitability but currently outside designated protection boundaries. To address this gap, this study sets the following primary objectives: (1) To develop a quantitative spatial assessment framework integrating Minimum Cost Resistance (MCR) and Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) models for evaluating the suitability of heritage corridor development across the entire Chang Zhen defense area; (2) To identify key environmental and socio-economic factors (slope, aspect, land use, vegetation cover, proximity to water, and crucially, transportation accessibility) that shape corridor suitability; (3) To spatially delineate high-potential heritage corridors and critically compare them with the boundaries of existing Great Wall protection zones to reveal mismatches and untapped opportunities.

Methods

Study area

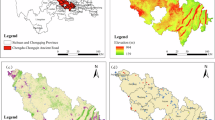

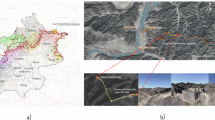

We take the Chang Zhen defense area of the Ming Great Wall as its research subject, which is currently distributed in Beijing (Changping District, Yanqing District, Mentougou District, Huairou District) and Zhangjiakou (Huailai County). Historically, its spatial extent is clearly recorded in the The History of the Four Towns and Three Passes22. It stretches from Mutianyu in the east to Zhenbian Fort in the west, bordering Ji Zhen, Zhenbao Zhen, and Xuanfu Zhen. As shown in Fig. 1, Chang Zhen and Ji Zhen are separated by Mutianyu; there is a section without a boundary wall between Chang Zhen and Zhenbao Zhen, where the space can be used to divide the two towns; Chang Zhen and Xuanfu Zhen are demarcated by the edge walls, with most of the Chang Zhen settlements located inside the walls, while Xuanfu Zhen settlements are distributed outside the walls.

Then, we take the various physical settlement site remains within the Chang Zhen defense area as heritage sources. These are the main protected objects within the study area and the “starting points” of the subject’s experience and perception process. Although there are numerous Ming dynasty Chang Zhen defense area sites, the number of settlements that have been truly excavated and still have remains is much smaller than expected. For example, although Changping Fort is the most prominent fortress in the Chang Zhen defense area, it has now evolved into the Beijing Changping District government and, therefore, is not included within the scope of the heritage corridor construction. According to the current China classification method for heritage protection units, the Great Wall heritage resources in Chang Zhen are divided into four levels, as shown in Table 1, to serve as heritage sources for corridor construction in this research. As shown in Fig. 1 and Table 2, totally there are 163 heritage points, including 4 national heritage, 2 provincial/city heritage, 6 county/district heritage, 33 sub-district heritage and other 118 beacon towers, border forts, or enemy observation posts along the route.

MCR

The Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) is a model used to describe and predict the movement of objects or individuals in space, first proposed by Dutch scholar Knaapen23. This model is commonly applied in fields such as animal migration, urban planning, and traffic flow. In the MCR, moving objects (such as animals, vehicles, etc.) are assumed to choose a path that minimizes the cumulative resistance encountered during their movement24. Resistance can be understood as the difficulties or obstacles faced by an object when moving through different environments. These resistance factors may include terrain, road conditions, the distribution of other objects, etc25. The Minimum Cumulative Resistance Model (MCR) is also widely used in heritage corridor construction. In this context, “resistance” is not simply the distance or slope on land, but refers to the various landscape resistances encountered when people subjectively engage in heritage leisure activities along a certain path. The greater the resistance, the more difficult it is to carry out the activity, and the lower its suitability. The lower the resistance, the easier it is to carry out the activity, and the higher its suitability, making it more appropriate for the construction of heritage corridors26, as Eq. (1).

In this model, MCR represents the minimum cumulative resistance from the heritage source α to a certain point in space; \({D}_{\alpha \beta }\) represents the spatial distance from the heritage source α to the scenic point β; and \({R}_{\alpha }\) represents the resistance at point β to heritage leisure activities. This model can be implemented using the ArcGIS platform.

AHP

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is a method used to decompose complex problems into a main objective, sub-objectives, and various levels of evaluation criteria. It is often combined with expert scoring to assign importance ratings to each level of elements27,28. By solving the eigenvector of the judgment matrix, the priority weight of each element at a given level relative to the elements of the previous level is obtained. Finally, using a weighted summation approach, a hierarchical regression is performed to determine the final weight of the main objective. The alternative with the highest final weight is considered the optimal solution29,30.

First, a judgment matrix \(A\) of size \(n\times n\) is constructed where the element \({a}_{{ij}}\) represents the relative importance between element \(i\) and element \(j.\) The judgment matrix is usually determined through expert scoring or some evaluation criteria, as Eq. (2).

where \({a}_{{ij}}=\frac{1}{{a}_{{ii}}}\) and the diagonal elements \({a}_{i}i=1.\)

Once the judgment matrix \(A\) is constructed, the next step is to calculate its eigenvector. The eigenvector corresponds to the priority weights of the elements. First, the largest eigenvalue \({\lambda }_{\max }\) of the judgment matrix \(A\) is computed, and then the weight vector \(W\) is determined by the following Eq. (3):

where\(W\) is the eigenvector, representing the weights of the factors. And the computed eigenvector needs to be normalized so that the sum of all weights can be caculated by Eq. (4).

where \({w}_{i}\) is the normalized weight. Then, it is important to check the consistency of the judgment matrix to ensure the rationality of the expert evaluations. The commonly used method is the Consistency Ratio (CR) and Consistency Index (CI), as Eqs. (5) and (6).

Random Consistency Index (RI) is a constant related to the size of the matrix, and values for Rl can be found in AHP reference tables for different matrix sizes. Generally when \({CR}\le 0.1\), the judgment matrix is considered to be consistent. After that we can get the final weight by Eq. (7), which is calculated by the weighted summation method.

where \({{\rm{w}}}_{{\rm{ij}}}\) is the weight of the \({\rm{i}}\)-th element at the \({\rm{j}}\)-th level relative to the elements in the previous level, and \({{\rm{w}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) is the weight of the element at the previous level31,32.

In this study, the AHP method is applied without the expert scoring process. Instead, values are assigned based on resistance scores extracted from a large number of literatures, which are then used to determine the weights of various indicators.The data obtained in this study are processed using the Yaahp software for AHP calculations, which is currently the most widely used AHP decision support tool, providing assistance in model construction, calculation, and analysis during the decision-making process.

This study combined AHP and MCR to construct a heritage corridor for the Great Wall in the Changzhen defense area. The overall research framework is shown in Fig. 2.

Influence factors

The MCR model was originally used for urban land suitability assessment, evaluating the characteristics of target land to determine whether it is suitable for specific development projects. In the early stages, the selection of influencing factors mainly focused on elevation, slope, and the distance between the target land and certain key urban service facilities. Over time, the model gradually evolved to assess ecological environments, using a combination of selected ecological suitability factors and applying a weighted evaluation. When this method is applied to heritage corridors, the selection of influencing factors takes into account more elements related to the geographical environment of the heritage site, as well as its overall protection. For example, typical cultural routes such as canal heritage and railway heritage are considered important factors in the selection process. This study combines findings from research over the past five years, as shown in Table 2, selecting key influencing factors that appear in more than half of the 8 most relevant studies33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. These factors include: slope, aspect, land use type, vegetation coverage, distance to urban transportation, and distance to main water sources. These references constitute research on heritage corridor construction for Great Wall heritage sites across diverse regions, demonstrating high relevance to the present study. Although these heritage sites are situated in distinct geographical settings, over half of the studies consistently selected the following six influencing factors, achieving statistically significant analytical results. Moreover, for the Chang Zhen defense area of the Ming Great Wall, all of these six factors are applicable to the region’s natural and social environment. These factors are used as resistance factors for constructing the MCR model.

Data resource

For the six selected resistance factors, it is necessary to assign resistance coefficients by grading them. Referring to grading methods from relevant studies, resistance coefficients for each grade were set, and the results are shown in Table 3.

a. the slope data were generated based on the DEM elevation model released by the National Geomatics Center of China41. The greater the slope, the higher the resistance value.

b. the aspect data were also generated based on the DEM elevation model of the defense area. In the case of grading the aspect resistance for heritage corridor construction, although northern regions typically prefer sunny slopes, most of China’s Great Wall is located in the arid and semi-arid areas of northern China. Sunny slopes have high evaporation, which is detrimental to vegetation survival. Therefore, from the perspective of requiring higher vegetation coverage to improve the quality of heritage corridor construction, south-facing slopes have higher resistance values.

c. for land use types, the classification is based on information from the 2023 version of the Resource and Environment Science and Data Center at the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences42. Forests and grasslands are more suitable for direct heritage corridor construction, while artificial surfaces, including roads, urban buildings, and public facilities, are harder to be converted into heritage protection zones, thus having higher resistance values.

d. vegetation coverage data were obtained from the 250-meter vegetation coverage dataset for China (2022), also from the Resource and Environment Science and Data Center43. The lower the vegetation coverage, the less favorable it is for heritage corridor construction, resulting in a higher resistance value.

e. the distance to the nearest water source was obtained from the major water systems data of China available on the Earth Resources Data Cloud44. Although ancient settlements were typically located near water sources to ensure easy access to water, modern construction in Beijing often places water bodies further away to reduce construction costs. Therefore, the closer the heritage source is to the nearest water source, the higher the resistance value.

f. the distance to the nearest transportation route was derived from the national road data extracted from the Peking University Geographic Data Platform in 202045. Since Chang Zhen’s Great Wall resources are not located in urban centers, road choices were not based on urban road classification but instead on national, provincial, county, and township roads. The further the heritage corridor is from the roads, the harder it is for visitors to reach, resulting in higher resistance values.

Results

Resistance value weight calculation

The resistance values of the six levels and 28 factors obtained in Table 4 are input into the Yaahp to solve the AHP judgment matrix. The consistency check results of this dataset are shown in Table 5, where CI, RI, and CR values are indicators used to measure the validity of the model in the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Generally, the smaller the CR value, the better the consistency of the judgment matrix. If the CR value is less than 0.1, the judgment matrix satisfies the consistency check.

After the consistency test, the final weights are determined as shown in Table 5. Among the six factors, aspect and land use type have relatively smaller proportions. In contrast, proximity to urban transportation and slope have the highest weights, indicating that traffic accessibility and construction difficulty are the most critical considerations in heritage corridor development for this area.

Resistance surface construction

After obtaining the weights of each resistance factor, the acquired element data is graded and classified according to the scoring standards, as shown in Fig. 3.

After determining the graded resistance values for each factor (Table 3), spatial processing was performed using ArcGIS 10.8:

Data standardization

All raster datasets (30 m resolution) were projected to WGS_1984_UTM_Zone_50N and resampled using bilinear interpolation to ensure spatial alignment.

Weighted overlay

The Raster Calculator tool executed the weighted sum: Final Resistance = (Slope × 0.209) + (Aspect × 0.072) + … + (Transportation Distance × 0.237).

Resistance surface generation

Output values were reclassified into five levels via Jenks Natural Breaks (0–150 scale).

The resulting resistance surface (Fig. 4) reveals distinct spatial patterns: Low-resistance zones (green) concentrate around fortress clusters with gentle terrain and road access, while high-resistance areas (red) dominate western mountainous regions.This surface functionally equates to a cost raster for establishing heritage corridors between heritage sources.

Suitability zoning

The derived resistance surface functionally equates to a cost raster for establishing heritage corridors connecting the Great Wall heritage sources. Utilizing this surface, we computed the cost distance to extant heritage sources along the Changzhen Great Wall section. To refine suitability zoning, the cumulative resistance values, calculated from the resistance surface (Fig. 4) with grading criteria (Table 3) and factor weights (Table 5), were classified into five suitability tiers via Jenks Natural Breaks (Fig. 5). Darker hues indicate higher MCR values, signifying lower suitability for corridor development. Specifically: Low-resistance zones (<50) correspond to high-suitability areas, predominantly distributed within fortress clusters (e.g., Gonghua Fort, Nankou Fort) characterized by gentle terrain and accessible transportation. High-resistance zones (>150) concentrate in western mountainous sectors with steep slopes and long transportation distance.

This suitability zoning of the heritage corridor also reflects the depth of the Chang Zhen Great Wall defense system, encompassing not only the main body of the Great Wall but also large fortifications on its interior side. Unlike linear heritage sites such as the Grand Canal or large railway systems, which can center their corridors around waterways or rail lines, the construction of heritage corridors for the Ming Great Wall requires more than just using the wall as the central axis. Instead, it necessitates a combination of points (large fortress sites) and lines (continuous Great Wall sections). The distribution demonstrates three notable characteristics:

a. Continuous Strip Zones Along the Great Wall.

Although the Great Wall’s main body is the core component of Great Wall heritage, from the perspective of heritage corridor construction, the Great Wall was mostly built in rugged and strategically significant locations. These areas generally have poor accessibility and lack sufficient supporting infrastructure. As a result, the suitability zones identified along the main body of the Great Wall along its line tend to form narrow strip-like areas without significant expansion or enlarged nodes.

b. Clustered Zones Centered Around Forts.

As shown in Fig. 5, the high-suitability zones are concentrated around Gonghua Fort, Baiyangkou, Nankou, Juyongguan, Badaling, Huiling, HuanghuaZhen, and Mutianyu, forming substantial clusters. Among these areas, except for Baiyangkou and Nankou Fort, which remain undeveloped, the others have already evolved into significant heritage tourism zones. This alignment demonstrates that the predictive approach corresponds well with actual development trends.

c. Significant Impact of Transportation Accessibility on Heritage Corridor Suitability Zoning.

The largest high suitability zone for heritage corridor construction is located in the central area of present-day Changping, Beijing, spanning from Gonghua Fort to the Ming Tombs. Although this area does not have the highest density of heritage sites, its proximity to the city and excellent transportation accessibility give it a significant advantage. In contrast, a comparison between the western section of the defensive zone and the eastern section reveals that the western section has much lower suitability. This disparity is largely attributable to transportation conditions. The western section, located at the border between Beijing and Zhangjiakou, lacks provincial and national highways, with only a few county and township roads connecting the area east to west. This is far inferior to the dense road network in the northeastern section of the defensive zone. Thus, based on the suitability simulation results for heritage corridor construction, transportation accessibility is the most critical factor, second only to the distribution of heritage resources.

Comparison with existing Great Wall protection zones

To evaluate the alignment of the derived heritage corridor suitability zones with existing Great Wall protection boundaries, we compare the suitability results with the protection policies for the Chang Zhen defensive area, which spans the administrative regions of Beijing and Hebei. Beijing’s current Great Wall Protection Ordinance stipulates that the area within 500 meters on both sides of the Great Wall is a non-construction zone, while the area between 500 and 3000 meters is designated as a construction control zone. In contrast, Hebei’s ordinance defines a narrower range, with 50 meters as the non-construction zone and 500 meters as the construction control zone. Despite these significant differences, the Joint Agreement on Strengthening Coordinated Protection and Utilization of the Great Wall in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region, signed by the cultural heritage bureaus of Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei in 2022, calls for unified standards in conservation policies46. This indicates that a breakthrough and standardization of these boundaries should become a priority.

Since the majority of the Changzhen Great Wall defensive area is located within Beijing, we adopted Beijing’s legally mandated 3000-meter construction control zone as the baseline reference. A 3000-meter protection buffer zone was established encompassing both the Wall structures and associated military settlements (indicated by the blue-striped area in Fig. 6). By overlaying this statutory protection buffer with the heritage corridor core zone derived from our model calculations (orange area in Fig. 6), we quantified their spatial correspondence. Key area metrics are summarized in Table 6. The overlap area between these two zones amounts to 48,198 hectares. This reveals two critical insights:

-

a.

Within statutory protection: The overlap constitutes 25% of the 3000-meter buffer zone, indicating that approximately one-quarter of the current legally protected territory is highly suitable for heritage corridor development.

-

b.

Within model-defined core: The overlap covers 68% of the heritage corridor core zone, demonstrating that nearly two-thirds of the model-identified priority areas already fall within existing conservation boundaries.

These results validate the spatial consistency between our suitability analysis and current protection measures, while also identifying potential zones for refinement in the current conservation strategy.

The comparison reveals significant differences between the heritage protection zones and the high-suitability zones for heritage corridors. In the northern and western parts of the Chang Zhen defensive area, where the terrain is more complex and transportation is less accessible, the control areas defined by existing Great Wall management regulations already encompass the high-suitability zones identified in this study. If these regulations are effectively implemented, they can ensure the continuity of the heritage corridor in these regions. However, in the southeast part, the high suitability zones for heritage corridors expand significantly around Baiyangkou, Nankou, and HuanghuaZhen. Notably, these zones also largely encompass the Ming Tombs Scenic Area, exceeding the boundaries of the original Great Wall protection zones. Unlike mature tourist destinations such as Juyongguan and Badaling, these regions have not yet excelled in Great Wall resource protection and development. Nevertheless, their high suitability for heritage corridor construction indicates considerable potential for future development.

Heritage corridor and existing infrastructure distribution

In addition to the geographical distribution of heritage sites, the construction of heritage corridors is deeply intertwined with existing infrastructure conditions. Areas with well-established municipal infrastructure are more conducive to the development of heritage resources. As of 2024, the distribution of accommodation, catering, shopping, medical, and entertainment POI data points within this region is shown in Fig. 7.

The highest density of POIs is found in the Changping central urban area, which acts as the primary hub for services and logistics in the Chang Zhen defensive area. Furthermore, the regions surrounding Gonghua Fort, Nankou Fort, and the Ming Tombs, which serve as key entrances to the defensive area, also stand out with robust infrastructure. These locations exhibit a level of service provision that even surpasses that of well-known tourist spots like Juyongguan and Badaling. Despite the favorable infrastructure in Nankou Fort and Gonghua Fort, their connection to Great Wall-related cultural industries remains minimal. These areas, which could serve as prominent gateways for showcasing and interpreting the heritage of the Chang Zhen defensive area, are currently underutilized, wasting their potential as prime display points for Long Wall-related narratives. While the Ming Tombs Scenic Area is relatively well-developed, its focus remains largely on the tomb heritage, with scant mention of the region’s Great Wall-related significance. Integrating Great Wall elements into the interpretation of this area could enrich its cultural narrative and enhance its appeal as part of a unified heritage corridor. Then, the POI data reveals that other fortress sites within the Chang Zhen defensive area suffer from sparse infrastructure. The lack of accommodation, catering, and other service facilities in these locations hinders their usability and appeal. Without targeted interventions, these unmaintained castle ruins face increasing risks of degradation and neglect, further exacerbating their underutilization.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that transportation accessibility and terrain gradient fundamentally determine heritage corridor suitability in the Chang Zhen defense area. High-potential zones, extending significantly beyond statutory protection boundaries, concentrate in historically integrated yet overlooked military-tomb complexes centered on the Ming Tombs. These critical regions exhibit substantial development potential due to their spatial advantages and favorable infrastructure. To ensure comprehensive protection, prioritized infrastructure enhancement is required in mountainous fortress areas, coupled with urgent stabilization of remote heritage sites. This strategy balances conservation and utilization by leveraging developed areas as interpretive gateways while addressing infrastructure gaps across the Chang Zhen defensive system, ultimately establishing a sustainable heritage corridor network for the Ming Great Wall.

The principal innovations and anticipated core contributions of this work lie in the novel application of the Minimum Cost Resistance (MCR) model to the specific challenge of Great Wall cultural heritage corridor planning, thereby establishing a robust and replicable methodological framework; this approach crucially enables the quantitative revelation that transportation accessibility and terrain conditions are paramount factors dictating corridor suitability, often surpassing the mere proximity to heritage resources themselves—a significant paradigm shift from traditional conservation focus which, in turn, facilitates the identification of specific, high-suitability zones extending beyond current protection, thereby challenging conventional conservation delineations. Practical implications include redirecting conservation priorities toward newly identified high-suitability areas currently outside legal protections and leveraging existing cultural hubs as interpretive gateways. Acknowledging the omission of non-designated heritage sites and reliance on literature-derived evaluation criteria as limitations, future work should prioritize field validation of model-predicted suitability zones and develop protocols for managing transboundary corridor networks.

Additionally, the original Changping Fort and Gonghua Fort were also military garrison sites for the tomb’s defense forces. On the one hand, the original Changping Fort has since evolved into the site of the Changping District government, with no remnants remaining. While Gonghua Fort is classified as a district-level heritage protection site, the related displays and connections to the Great Wall and the Ming Tombs are not present in the Gonghua Heritage Park. On the other hand, in the currently open Ming Tombs, including the Changling, Dingling, Zhaoling, and Kangling tombs, there is almost no explanation of the relationship between the Ming Tombs and the surrounding Great Wall. In the Ming dynasty, Chang Zhen was specifically designed to provide military settlements for the area around Tian Shou Mountain, primarily including 10 strategic passes under Chang Zhen’s jurisdiction along the Juyong Road (Fig. 8). These passes surrounded the Tian Shou Mountain tomb area, playing a direct role in early warning and defense. These 10 passes are still located around the Ming Tombs scenic area, with some sections of the Ming Great Wall remaining, but they have not yet been fully utilized for wall-centric development. Even in the largest exhibition space of Dingling, the only reference to the Great Wall is found in the first exhibition room, where a map of the entire Ming Tombs is displayed, and the “Zhuishi Col”(Zhuishi Kou) is marked(Fig. 9). The rest of the exhibition space does not mention the Great Wall or the historical connection between the tombs and the surrounding defense system.

In order to solve these problems of unbalanced and inadequate development, Nankou Fort and Gonghua Fort should receive strategic investments in Great Wall-related cultural industries to capitalize on their existing infrastructure. The Ming Tombs Scenic Area should expand its narrative to incorporate the Great Wall of Chang Zhen, leveraging its established visitor base to promote broader regional heritage. Underserved fortresses require targeted infrastructure development to stabilize their preservation and integrate them into the broader heritage corridor network. Balancing infrastructure development across these regions is essential to ensuring the long-term viability and success of the Chang Zhen heritage corridor.

This study also has certain limitations. On the one hand, regarding the selection of influencing factors, we temporarily selected only the six most representative factors from existing studies. These prior studies generally used no more than 10 influencing factors, and our final selection of six factors had recurrence frequencies ranging from 50% to 100% in the literature. While these are widely recognized and representative elements, there remains potential to expand the factors and further improve model construction. On the other hand, the purpose of this research is to propose suggestions for current heritage protection boundary delineation through heritage corridor modeling. Current methods that rely solely on measuring distances between construction land and heritage sites—though easy to implement—are clearly inadequate. Our approach does not aim to delineate precise protection boundaries through this model, but rather focuses on identifying areas with corridor development potential and prioritizing protection targets. In subsequent practical work, more specific on-site conditions will be incorporated to refine boundary-planning methods.

Data availability

The data and materials are included in the article. Additional information can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Waldron, A. The Great Wall of China: from history to myth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; (1992).

Du, Y. From Tun-Bao To Great Wall:The Study of North Defense in Ming China. master’s thesis, Taiwan: National Cheng Kung University. https://hdl.handle.net/11296/23d9rx (2009).

Unesco. Convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage. Paris: UNESCO - Intangible Heritage; https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention#part1 (2003).

Yang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Li, Y. Temporal and spatial distribution characteristics of the Ming Great Wall. Herit. Sci. 12, 81 (2024).

Peterson, W. J. The Cambridge history of China: volume 9, The Ch’ing Dynasty to 1800, part 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; (2016).

Dan, X., Minghao, Z. & Lifeng, T. Study on the spatial characteristics of defensive settlements in Zijingguan defence area of the great wall of the ming dynasty based on gis. China Cultural Herit. 6, 97–104 (2020).

Cao, Y. & Zhang, Y. Efficient space and resource planning strategies: treelike fractal traffic networks of the Ming Great Wall Military Defence System. Ann. Gis. 24, 47–58 (2018).

He, J. GIS-based cultural route heritage authenticity analysis and conservation support in cost-surface and visibility study approaches. The Chinese University of Hong Kong. (2009). CUHK LibrarySearch-b5893854.

Li, Z. et al. From data acquisition to digital reconstruction: virtual restoration of the Great Wall’s Nine Eyes Watchtower. Built Herit. 8, 22 (2024).

Cho, Y. Juyong Gate: Wall Hangings in Stone. Arch. Asian Art. 72, 221–253 (2022).

Correa, A., Mendoza, M., Etter, A. & Salicrup, D. Habitat connectivity in biodiversity conservation: a review of recent studies and applications. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 40, 7–37 (2016).

Jones, T. A. Ecosystem restoration: recent advances in theory and practice. Rangel. J. 39, 417 (2017).

Koen, E. L., Bowman, J., Sadowski, C. & Walpole, A. Landscape connectivity for wildlife: development and validation of multispecies linkage maps. Methods Ecol. Evolution. 5, 626–633 (2014).

Li, J., Shan, M. & Qi, J. Coupling coordination development of culture-ecology-tourism in cities along the grand canal cultural belt. Econ. Geogr. 42, 201–207 (2022).

Tuxill J. L. Reflecting on the Past, looking to the future: sustainability study report: a technical assistance report to the John H. Chafee Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor Commission. Woodstock, VT: USNPS Conservation Study Institute; (2005).

Li, H. et al. Identifying cultural heritage corridors for preservation through multidimensional network connectivity analysis-a case study of the ancient Tea-Horse Road in Simao, China. Landsc. Res. 46, 96–115 (2021).

Chang, B. R. et al. Spatial-temporal distribution pattern and tourism utilization potential of intangible cultural heritage resources in the Yellow River Basin. Sustainability 15, 2611 (2023).

Li, Y. Y., Wang, X. H. & Dong, X. F. Delineating an integrated ecological and cultural corridor network: a case study in Beijing, China. Sustainability 13, 412 (2021).

Ye, H., Yang, Z. P. & Xu, X. L. Ecological corridors analysis based on MSPA and MCR model—a case study of the Tomur world natural heritage region. Sustainability 12, 959 (2020).

Zhang, J. H. et al. A study on the spatiotemporal aggregation and corridor distribution characteristics of cultural heritage: the case of Fuzhou, China. Buildings 14, 121 (2024).

Bai, J. et al. Resource supply and demand model of military settlements in the cold weapon era: case of Zhenbao Town, Ming Great Wall. Herit. Sci. 12, 389 (2024).

Ninghua, M & Fanshi, K. Atlas of Chinese Cultural Relics(Beijing). Beijing: Science Press. (2007).

Knaapen, J. P., Scheffer, M. & Harms, B. Estimating habitat isolation in landscape planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 23, 1–16 (1992).

Bennett, G. & Mulongoy, K. J. Review of experience with ecological networks, corridors and buffer zones. Secretariat Convention Biol. Diversity. Montr., Tech. Ser. No. 23. 23, 5–6 (2006).

Li, X. et al. Research on the construction of intangible cultural heritage corridors in the Yellow River Basin based on geographic information system (GIS) technology and the minimum cumulative resistance (MCR) model. Herit. Sci. 12, 271 (2024).

Sun, W. et al. Construction and optimization of ecological spatial network in typical mining cities of the Yellow River Basin: the case study of Shenmu City, Shaanxi. Ecol. Process. 13, 60 (2024).

Bro, R. & Smilde, A. K. Principal component analysis. Anal. Methods 6, 2812–2831 (2014).

Wulf, J. Development of an AHP hierarchy for managing omnichannel capabilities: a design science research approach. Bus. Res. 13, 39–68 (2020).

Du, Y., Chen, W., Cui, K. & Zhang, K. Study on damage assessment of earthen sites of the Ming Great Wall in Qinghai Province based on fuzzy-AHP and AHP-TOPSIS. Int. J. Architectural Herit. 14, 903–916 (2019).

Igwe, O. et al. GIS-based gully erosion susceptibility modeling, adapting bivariate statistical method and AHP approach in Gombe town and environs Northeast Nigeria. Geoenviron. Disasters 7, 32 (2020).

Abdelouhed, F. et al. GIS and remote sensing coupled with analytical hierarchy process (AHP) for the selection of appropriate sites for landfills: a case study in the province of Ouarzazate, Morocco. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 69, 19 (2022).

Liquete, C. et al. Mapping green infrastructure based on ecosystem services and ecological networks: a pan-European case study. Environ. Sci. Policy 54, 268–280 (2015).

Ma, Y. Research on conservation and utilization methods of the Great Wall heritage corridor based on cumulative resistance evaluation. Beijing: Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, (2022).

Li, W. & Cao, X. Construction method of traditional settlement heritage corridor along the Inner Great Wall of Ming Dynasty in Shanxi Province based on suitability analysis. Small Town Constr. 40, 59–68 (2022).

Su, Y., Ma, Y & Chen, M. Research on heritage corridor construction of Gubeikou Great Wall based on ecological suitability evaluation. Beijing Plann. Rev. 125–129 (2022).

Feng, J., Li, Y & Li, C. Planning of Ming Great Wall heritage corridor in territorial spatial planning system. Proceedings of 2021 China Urban Planning Annual Conference. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press.14, (2021).

Shui, J., Yao, G. & Feng, X. Landscape forest construction strategy in cultural heritage corridors: Case study of Ancient Great Wall cultural heritage corridor in Datong. J. Beijing Forestry Univ. 41, 139–152 (2019).

Feng, J., Sun, J. & Huang, S. Construction method of Ming Great Wall heritage corridor: Case of Yanghe Dao jurisdiction. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press, 8, (2019).

Shui, J. Strategy and method for landscape forest construction in Northern Shanxi Ming Great Wall cultural heritage corridor. Beijing: Beijing Forestry University, (2019).

Li, J. Construction system of heritage corridor for fortress cities along Liaodong Great Wall. Shenyang: Shenyang Jianzhu University, (2019).

National Geomatics Center of China. https://www.ngcc.cn/.

Resource and Environment Science and Data Center. https://www.resdc.cn/

Earth Resources Data Cloud. http://gis5g.com/data/dxdm.

Peking University Geographic data platform. https://geodata.pku.edu.cn/.

Beijing Municipal Bureau of Cultural Heritage, Tianjin Municipal Bureau of Cultural Heritage, Hebei Provincial Bureau of Cultural Heritage. Joint Agreement on Strengthening Coordinated Protection and Utilization of the Great Wall in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant No.52478049 & Tianjin Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project: Special Research on Tianjin Culture, No. TJJWZD03-02 & Tianjin Art Science Planning Project, Grant No.A24011.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z. wrote the main manuscript text, J. H. reviewed the draft and provide funding, L.T. prepared figures and data, S.Y. finished the editing, visualization and methodology. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, J., He, J., Tan, L. et al. Integrity protection of the Chang Zhen Great Wall heritage corridor based on minimum cumulative resistance. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 479 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02044-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02044-8

This article is cited by

-

Identification, evaluation, classification of the Chengdu-Chongqing Ancient Road cultural heritage corridor

npj Heritage Science (2025)