Abstract

This paper reviews the use of holographic displays in museums, highlighting their role in enhancing visitor engagement, accessibility, and artefact preservation. Holography offers realistic 3D representations without special equipment, supporting immersive yet passive experiences. Compared to other digital technologies, it fosters natural viewing and emotional connection. The paper identifies current applications, key challenges, and future research directions to advance the integration of holography in museum contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, using digital technologies in museums has become essential to creating more immersive and interactive visitor experiences1. The theme of International Museum Day 2025, The Future of Museums in Rapidly Changing Communities, affirms the museum’s position as a site of innovation and inclusivity in response to global challenges2. This thematic development underscores the paradigm shift in museology—away from static object presentation toward dynamic, participatory, and emotionally resonant visitor experiences. This trend reflects broader societal shifts driven by the advancement of information and digital technologies, which mark the 21st century as a digital era. The integration of digital media technologies into museum exhibition design has notably improved both the form and function of museum spaces, particularly in art museums, where they have fostered new spatial aesthetics and enriched audience experiences3. Among these technologies, holographic displays have emerged as an innovative tool for enhancing visitors’ engagement with exhibits4. Unlike traditional two-dimensional displays or other interactive technologies, holography offers a unique combination of realism, depth perception, and dynamic interaction, allowing visitors to connect with exhibits more profoundly5.

Holographic displays offer museums the ability to present three-dimensional representations of artefacts, often without the need for special viewing equipment, which makes them more accessible to a wide audience6. By providing a sense of depth and physical presence, holography allows visitors to experience objects as if they are physically in front of them, creating a powerful emotional connection and enhancing the overall visitor experience5,7.

One of the most promising applications of holography in museums is its ability to display fragile or inaccessible objects. Due to their delicate nature, many historical artefacts are often stored away for preservation, limiting public access8,9. Holography enables museums to create highly detailed, full-colour, three-dimensional holograms of these objects, allowing visitors to examine them closely without the risk of physical damage10. Additionally, holography facilitates the digital reconstruction of lost or damaged artefacts, offering representations that maintain historical accuracy and visual authenticity9.

Despite these advantages, the integration of holography in museum exhibitions faces several challenges, such as high implementation costs, technological limitations, and concerns regarding digital authenticity remain key obstacles to widespread adoption8,11. Moreover, the evolving nature of holographic display technologies requires further advancements to enhance realism, improve usability, and optimise cost-efficiency for broader museum implementation.

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the role of holographic technology in enhancing visitor engagement, accessibility, and artefact preservation in museum settings. By synthesising existing research, case studies, and empirical findings, this paper examines the impact of holography on visitor experiences, its comparative advantages over other digital technologies, and the challenges that must be addressed for broader adoption. Finally, the review outlines key research directions for advancing holographic applications in museums, contributing to the ongoing discourse on digital innovation in cultural heritage.

Research objectives

Holography has emerged as a transformative technology in museum exhibitions, offering new ways to enhance accessibility, visitor engagement, and artefact preservation. By enabling three-dimensional visualisations of historical objects, holography provides a more immersive and interactive experience than traditional museum displays. However, implementing this technology raises various challenges, including cost, technical limitations, and questions of digital authenticity. The primary research objectives of this paper are as under:

-

RO1: To examine the role of holography in enhancing visitor engagement and emotional connection within museum exhibitions.

While visual immersion has been widely discussed, the specific emotional affordances of holography remain under-theorised, particularly in comparison to other display technologies.

-

RO2: To explore holography’s perceptual and psychological impact on museum audiences, particularly in comparison to traditional and other digital display methods.

Although many studies describe the visual appeal of 3D technologies, few critically differentiate how holography uniquely influences perception, memory formation, and affective response.

-

RO3: To evaluate the challenges and limitations of implementing holographic museum displays, including technical constraints, cost, and authenticity concerns.

Existing literature tends to focus on the benefits of holography, with less emphasis on its practical barriers or curatorial trade-offs in real-world museum settings.

-

RO4: To identify future research directions and technological advancements to optimise holographic applications in cultural heritage settings.

Despite its growing application, there is a lack of consolidated vision regarding how holography can evolve to meet the emerging needs of inclusive, accessible, and emotionally engaging exhibition practices.

Holography and artistic integration

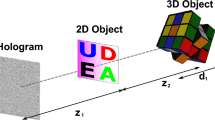

Holography was discovered in 1948 by Denis Gabor who proposed to use this technique to improve the resolution in electron microscopy, for which was awarded the Nobel Prize in 197112. Holograms were successfully created by Emmett Leith and Juris Upatnieks in the USA and Yuri Denisyuk in the USSR in 1962, building on the invention of the Denis Gabor holographic principle as well as the Theodore Maiman laser. Further research by Stephen Benton and others led to the widespread use of holograms, which gradually came into view, enriching human perception and experience13. Holograms record the complex amplitude of light from an object, rather than the intensity distribution of light to an image as in photography, capturing much more data than photographs. The ‘data’ in a hologram refers to the complex amplitude information that is encoded in the interference pattern, capturing both the intensity distribution (amplitude) and the spatial relationships (phase) of light waves scattered from the object. This comprehensive data allows holograms to provide a more accurate and realistic representation of objects compared to traditional two-dimensional photographs. The recording of amplitudes is done by generating an interference pattern, in which a reference beam is superimposed on the object beam, thus recording an interference pattern, which can be recorded on various physical mediums, such as chemical emulsions and photopolymers which enables the recording of amplitudes and phases. This recording can reconstruct a true three-dimensional image of the original object14. Based on these technical features, holograms capture ‘true’ three-dimensional space and any objects which are placed within that space in visual terms. It provides a unique approach to recording and reproducing three-dimensional space on a flat surface, in a way that creates a visual effect that mimics seeing a three-dimensional image. Viewers do not need special glasses or headgear to experience holograms15. Moreover, holograms can range from static to dynamic, with the viewer’s head moving instantly and naturally5. Holography has attracted tremendous interest due to its capability of storing both the amplitude and phase of the light field and reproducing vivid three-dimensional scenes16.

Digital holography is a technological update on traditional holography, using digital imaging sensors and computer processing to capture, reconstruct and display holographic images17. This technique combines the principles of holography with the advantages of digital imaging technology to produce high-quality, versatile holograms. Digital holography has several advantages over traditional holography, such as the ability to manipulate and process holographic data digitally, reduced noise and artefacts, and the possibility of real-time image reconstruction. Digital holography is used today for various purposes, such as microscopy, interferometry, surface measurements, storage and three-dimensional display systems18. However, the process of holographic development was initially published in specialist scientific and optical journals, rarely accessed by the art and design community. As a result, the application of holographic technologies has encountered resistance in the artistic field, giving the impression it is more of a technical subject than an artistic one19.

Consequently, the transfer of practical information about holography from optical scientists to artists is gradual. Nonetheless, as technical reports on holography began to appear in publications, such as Scientific American and Leonardo, more artists began to appreciate the creative possibilities holography offered for art. The first hologram appeared in 1964 by American scientist Emmett Leith, entitled ‘Train and Bird’, shown in Fig. 1. From this moment onwards, the imaging possibilities of holography have intrigued artists from various disciplines and practices.

Train and Bird, laser-viewable transmission hologram (1963) by Emmett N. Leith and Juris Upatnieks. Courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History (Public Domain, CC0)20.

As artistic awareness of holography grew, individual artists began to explore its creative and perceptual possibilities. One such pioneer was Margaret Benyon, who, in the late 1960s, transitioned from painting to holography, recognising its potential as a medium of artistic expression. Her early works demonstrated how holography could be used beyond scientific applications, marking a shift towards its artistic integration.

Visual perception and emotional engagement in holographic displays

Visual stimuli play a pivotal role in eliciting emotional responses through two primary mechanisms: psychological factors, such as perception and attention, and artistic visual cues, including colour, symmetry, and complexity19,20. Perception, as a cognitive process, encompasses the organisation of sensory information and its subjective interpretation, collectively shaping emotional responses21. These visual cues often operate subconsciously, triggering automatic emotional reactions without explicit cognitive processing, highlighting their universality across diverse cultural contexts22. The thoughtful application of visual design elements, such as colour, symmetry, and complexity, influences emotions such as joy and sadness and enhances emotional engagement by creating more immersive and memorable experiences21,22. Sensory design becomes significantly more effective when combined sensory inputs enhance emotional arousal and memory retention22. This principle is particularly relevant in the context of holographic displays in museum settings, where three-dimensional visual effects can immerse visitors and evoke nuanced emotional experiences, fostering deeper connections with cultural artefacts and narratives.

As we grow accustomed and desensitised to traditional forms of presentation, so too does their effectiveness in conveying information diminish. Designers and artists need to provide novel approaches, dimensions and explorations for more ‘stimulated’ perceptions of human beings23. Building on her early experiments, Benyon, in collaboration with D. Canter, conducted studies on audience reactions to holographic art exhibitions. They found that most people were ‘surprised, fascinated, and even shocked’ when they saw holograms, with some viewers even unable to distinguish between the holograms and the objects. As an artist, she also detected that the audience could go through an ‘unspoken illusion’, with a misinterpreted perception of such a sensory experience. Holograms, with their stunning three-dimensional realism and expressive potential, can influence the responses of the ‘human senses’. Benyon suggested that holograms are a more direct medium of perception than paintings, and allow for a more comfortable, realistic and immersive viewing experience24.

Valyi-Nagy provides a theoretical analysis of how holograms provoke embodied and affective responses, focusing specifically on Paula Dawson’s large-scale laser transmission holograms (Fig. 2)25. Drawing upon the concepts of haptic visuality and Einfühlung (“feeling-into”), Valyi-Nagy argues that Dawson’s holograms activate a kinaesthetic mode of viewing, entangling visual and tactile perceptions. Rather than being merely visual representations, these holographic images elicit bodily engagement, prompting viewers to physically move around the virtual image space, often reaching out or leaning forward, despite the impossibility of actual touch. This sensory tension created by the simultaneous visual presence and tactile absence intensifies viewers’ emotional sensitivity and somatic awareness. According to Valyi-Nagy, such perceptual dynamics distinguish holography not only from static images but also from immersive VR environments, positioning holograms within a distinct lineage of materially grounded, experiential visual art.

Paula Dawson, To Absent Friends, 1989, detail of the five o’clock in the evening hologram, Macquarie University Art Collection, Sydney, Australia (photograph by Effy Alexakis, Photowrite; provided by Macquarie University Art Gallery)25.

A recent empirical study by Xu et al. investigated how holographic displays facilitate emotional engagement within museum contexts26. Through structured interviews with sixteen museum professionals, designers, and cultural heritage practitioners, the researchers explored affective responses elicited by a holographic exhibit featuring a Roman intaglio. Utilising TF-IDF textual analysis, the study identified ‘curiosity,’ ‘wonder,’ and ‘lifelike’ as the predominant emotional descriptors. Participants particularly emphasised the hologram’s three-dimensional spatial realism, depth perception, and tactile illusion as primary triggers of emotional responses. Additionally, the findings revealed a clear emotional progression, where initial reactions of fascination and intrigue evolved into sustained cognitive reflection. This suggests that holography can effectively support both immediate and enduring forms of visitor engagement. The insights underscore the emotional affordances inherent in holographic display technologies, highlighting their potential to significantly enhance interpretive depth and create memorable experiences in museum exhibitions.

With modern science and technology development, the construction of places has become more uncomplicated and straightforward. Many visual artists actively respond to the drastic changes in today’s society, to build communication between real and virtual places, where holographic technologies can be used to integrate them organically 27. From a media perspective, virtual reality (VR), with its new ways of communicating information and sensory experiences, produces a disruptive form of communication - immersive communication. While human consciousness is considered a purely natural (biological) phenomenon28, consciousness is also an individual’s awareness of unique thoughts, memories, feelings, sensations, and environments, from others and themselves. Essentially, consciousness is one’s awareness of the world around them, and it is subjective and unique. From the perspective of human consciousness, immersion is inextricably linked to the creation of authentic and believable situations. Immersion has been described as an emotional and cognitive experience that allows people to forget actual reality and see the digitally brought experience as reality 29, while holograms are considered to have the natural parallax and focusing ability to reproduce real scenes. It can present three-dimensional images with realistic visual effects and combine with depth-of-field information from the physical environment.

In addition to content and format, the emotional impact of holography is shaped by its presentation context. A recent experimental study by Wei et al. found that correlated colour temperature (CCT) significantly influences viewers’ emotional reactions to monochromatic holographic images30. Specifically, lighting conditions at both extremes (warm at 3000 K and cool at 6000 K) elicited stronger emotional responses compared to neutral lighting (4000 K), with warm lighting generally preferred for enhancing emotional connectivity and perceived realism. These findings underscore the importance of curatorial lighting design, suggesting that emotional engagement in holographic environments is co-constructed by visual content and its ambient lighting conditions. For curators and exhibition designers, such insights offer practical guidance for optimising the affective atmosphere through precise control of lighting parameters.

Since holograms can produce highly detailed images at multiple angles, viewers are given the opportunity to engage with the scene in unique ways not offered by traditional two-dimensional and stereoscopic three-dimensional displays, such as perceiving depth. Menning and Piper found that three-dimensional space created by holograms can be perceived from a human physiological perspective and suggested that holograms can bring about physical effects and tactility31. As Martina Mrongovius explained, “When the recorded visual perspective matches the spatial perception of the viewer, the hologram produces a visually realistic volume”32. These characteristics of holograms provide the viewer with an incredible sense of visual reality 5. As a result, the expansion of space offered by holograms can construct the narrative content in a multi-dimensional way. Compared with the conventional method, it can provide the spatial dimension of visual narrative with extended possibilities and deliver richer narrative content. The narrative presented by the holograms breaks through the visual limitations of traditional media, bringing tension and a real three-dimensional visual experience to the viewers.

These studies collectively show that the emotional impact of holographic displays in museum settings is shaped by a combination of visual fidelity, spatial depth, and curatorial context. Factors such as perceptual realism, the illusion of tactility, and ambient conditions contribute to how visitors experience and interpret holographic content. Rather than serving purely as a technological novelty, holography emerges as a medium capable of fostering meaningful emotional engagement, enhancing cultural interpretation, and supporting more memorable, affectively rich encounters with heritage.

Theoretical framework of holographic displays in emotional engagement

To bridge empirical insights with conceptual clarity, this section introduces a theoretical framework that elucidates how holographic display technologies mediate emotional engagement in museum contexts. Grounded in our recent empirical study, the framework identifies six interrelated mechanisms through which holography evokes emotional resonance, facilitates memory formation, and enriches interpretive depth26.

Emotional responses such as curiosity and wonder play a critical role in memory formation and knowledge retention, particularly within immersive museum environments. The vividness and lifelikeness of holographic displays allow emotional arousal to act as a cognitive anchor, reinforcing information processing and long-term recall. Participants in our study frequently reported that engaging emotions led to a deeper understanding of artefacts, thus supporting the broader educational mission of museums33,34.

Holographic displays evoke strong emotional reactions through their distinctive sensory characteristics, including three-dimensionality, spatial layering, and vivid colour representation. These passive yet immersive features elicit emotions such as shock, excitement, and wonder, without requiring active interaction5. Visual effects that simulate depth and tactility provoke instinctive emotional responses, often described as lifelike or surreal35. These findings align with current research on how multisensory design influences visitor emotions in cultural spaces22.

Another key theoretical insight concerns the emotional trajectory visitors experience while interacting with holographic exhibits. Our data shows that initial responses of curiosity often evolve into wonder, imagination, and further engagement—an emotional sequence that sustains attention and promotes active reflection. This progression reflects how holography not only captures attention but guides visitors into deeper cognitive and emotional involvement36,37.

Holography’s capacity to support layered storytelling contributes significantly to emotional resonance. Through z-axis layering, spatial realism, and light design, holographic exhibits serve as narrative tools that blend historical information with experiential immersion. This emotional intensity enriches interpretive depth and promotes meaningful visitor-artefact relationships, especially in thematic or storyline-driven exhibitions9,35,38.

Holography also functions as a medium for emotional substitution, allowing visitors to engage meaningfully with artefacts that are absent, unavailable, or fragile. This technological mediation preserves not only informational content but also emotional continuity, particularly when physical displays are limited. By offering realistic three-dimensional substitutes, holography ensures uninterrupted educational and cultural engagement9,35.

Finally, the long-term impact of emotional engagement through holography extends beyond the immediate visit. Participants in our study described strong emotional persistence, such as anticipation for future visits and increased likelihood of recommending exhibitions to others. These findings underscore the potential of holography to shape visitor behaviour over time and enhance cultural participation1,34.

Distinguishing critical perspectives of 3D holographic, stereoscopic, and autostereoscopic displays

In museum contexts, three-dimensional (3D) display technologies are increasingly used to enrich visitor engagement and enhance the delivery of content. However, the blanket label “3D” often masks the fundamental differences among holographic, stereoscopic, and autostereoscopic displays that bear directly on perceptual experience, emotional engagement, and curatorial applicability.

Stereoscopic displays create the illusion of depth by delivering two offset images to the left and right eyes, requiring the viewer to wear glasses to perceive binocular disparity. While this technique is widely implemented, it is often associated with visual discomfort due to the vergence–accommodation conflict, a mismatch between convergence distance and focal depth that may result in eye strain or fatigue39. Autostereoscopic displays, which aim to remove the need for glasses, utilise parallax barriers or lenticular lenses to separate views for each eye. Although they provide a glasses-free experience, these systems often constrain users to narrow “sweet spots” and may suffer from reduced resolution, brightness, or image distortion at oblique angles. As Urey et al. point out, autostereoscopic displays are particularly sensitive to viewer position and ambient lighting conditions, which can significantly limit their effectiveness in public exhibition settings40.

In contrast, holographic displays reconstruct the full light field of an object using interference and diffraction, enabling accurate spatial reproduction of depth, parallax, and perspective shifts. Viewers can move freely around the image without specialised equipment, experiencing depth and realism unattainable in planar displays41. Earlier innovations, including the CHIMERA full-colour holographic printer developed by Gentet, have demonstrated how holography can produce visually compelling, high-resolution 3D images with full parallax and depth cues. These technologies offer promising applications in museum contexts, where spatial fidelity and visual immersion are essential to enhancing visitor engagement42.

Technological distinctions manifest not only in visual realism but also in emotional and interpretive impact. Stereoscopic and autostereoscopic systems tend to provoke initial fascination but lack the perceptual continuity required for sustained immersion. Studies indicate that such displays are often perceived as visually novel but cognitively superficial, especially when discomfort or fixed viewpoints disrupt engagement39,40. By contrast, holography has demonstrated stronger affective affordances in cultural heritage environments. Empirical evidence suggests that holographic museum displays can elicit deeper emotional responses and support more reflective, cognitively engaged forms of interpretation26.

From a curatorial perspective, these distinctions necessitate careful evaluation. Holography offers significant advantages in perceptual realism, multi-viewer accessibility, and narrative potential. While costs and technical complexity remain challenges, developments in hardware and content generation are steadily lowering the barrier to implementation43. In contrast, stereoscopic and autostereoscopic formats may remain viable in constrained contexts but should be used with an awareness of their experiential limitations. Critically, conflating these technologies under the broad label of “3D” risks overlooking the distinctive spatial and emotional affordances of each. A nuanced understanding of these differences enables more deliberate and impactful integration of visual technologies in museum practice.

Evolution of museology: from object-centred displays to visitor-centric experiences

Museology may be regarded as consisting of cultural studies and cultural theory to define new possibilities and methodologies for the curation of artworks, collections and exhibitions and their display9. New museology has recently shifted its focus from museum exhibits to the visitor experience. Museology views the museum as an educational tool in the service of the development of society, an environment for learning and enjoyment for its visitors44. In museums, participatory experience means involving visitors in an exhibition or activity and utilising the experience to better understand and enjoy what the exhibit or activity is about45. Participatory experiences can be achieved in a variety of ways, for example, through the provision of immersive exhibitions, interactive installations, creative displays, etc. Through participatory experiences, visitors can acquire a deeper understanding of the content, obtain the essence more intuitively, and share and exchange with other visitors, thus enhancing the attractiveness of the museum and the visitor experience.

Since the 20th century, much of museology literature has emphasised the importance of improving museum user experience and how to engage visitors. For example, in 2017, Eva Pietroni, an art historian and cultural heritage conservation expert, suggested that museums were often overly redundant: exhibition space is often overloaded with objects, giving the impression that they needed more living space. Too many similar objects repeat, and visitors often experience information overload, causing very limited attention span on individual objects, often skipping many altogether46.

Scholars Hee Soo Choi and Sang-Hyun Kim indicated that the methods of museum exhibitions were rapidly changing. While focusing on visitors’ museum experience, new display methods employed various digital technologies to provide exhibition content that allowed visitors to better understand the artefacts on display47. Professor of psychology and education at the University of Michigan, Scott G. Paris, indicated that museums were moving away from object-based displays. The displaying objects and relative educational interpretation were sufficient to convey the intrinsic meaning of the objects. Museums have experimented with new modes of communication, particularly those that communicate cultural significance through integrating objects, displays, new media and visitors’ psychological narratives48. In this new paradigm, the object’s authenticity was no longer an important issue relative to its potential to support viewer engagement and learning processes. The notion of the viewer gaining experience becomes increasingly crucial in museum studies46.

In 2018, Kosmopoulous and Styliaras argued that in modern museology, museum visitors’ encounters with objects and collections had become the focus of attention49. From the viewers’ perspective, they were no longer satisfied with ordinary, homogenous objects on display, but were looking for bespoke, emotional experiences50. Popularising visitor-oriented concepts has created new challenges for museums, prompting them to seek and provide visitors with memorable experiences. Significantly, this direct and unique experience cannot be replicated. In addition, visitors’ knowledge and interests enable them to participate and interact during the visit and engage in a more extraordinary and intense experience51. As early as 1999, director Doering, project analyst Pekarik and social science analyst Karns developed the concept of ‘satisfying experiences’ and divided these experiences into four aspects: object experiences, cognitive experiences, introspective experiences, and social experiences. Object experiences refer to seeing the ‘real thing’, rare or valuable objects, and being astounded by authenticity. Cognitive experiences focus on interpretive or intellectual experiences, including gaining information or knowledge, or enriching understanding. Introspective experiences emphasise private feelings and experiences, such as imagination, reflection, memory and connection. Social experiences focus on interactions with friends, family, other visitors or museum staff. These conceptions still seem instructive for the present52.

Museum contextual design based on digital media technology is making traditional museum formats increasingly abundant. New technologies are gradually expanding the museum experience from a predominantly visual one to an integrated contextual experience that includes enhanced experiences, immersive experiences, virtual experiences, and personalised experiences, which can significantly enhance the visitor experience. Hence, museums are trying to develop a more viewer-centric perspective, and they are focusing on viewer experience management52,53. Previous research on visitor experience has shown the perceived experience is a major determinant of viewer satisfaction, memory retention, and willingness to recommend or repeat the experience52,54. As a result, museums have become increasingly active and interactive, with visitors constantly stimulated and engaged by the increasingly interactive exhibitions55. Each element engages the visitor in a unique and personalised experience1.

The role of museums in society is changing. Museums are reinventing themselves to become more interactive, audience-centred, community-oriented, flexible, adaptable, and mobile. Museums have become cultural centres, serving as platforms where creativity and knowledge are combined, and visitors can co-create, share and interact. Nowadays, museums seek innovative ways to address contemporary social issues and conflicts, striving to respond positively to society’s challenges. As core public institutions, museums can build dialogue between cultures, build bridges for a peaceful world and define a sustainable future. As museums increasingly grow as cultural centres, they are also finding new ways to commemorate collections, history and heritage, creating new traditions for future generations and being relevant to an increasingly diverse contemporary audience on a global scale56.

Holography in museums: enhancing accessibility, engagement, and immersion

From exhibiting artefacts to installing digital displays, museums are moving into the future through technological innovation57. New technologies such as VR, augmented reality (AR), and holography are reshaping the visitor experience, merging educational content with entertainment57. By enhancing engagement, these tools enrich the educational value of exhibits and appeal to younger, technologically oriented audiences. In particular, holography offers unique advantages over other digital technologies, such as AR and 3D films, particularly in facilitating passive interaction. Barabas and Bove’s exploration into holographic displays reveals a form of interaction where visual realism and depth perception depend on the observer’s movements. This interaction allows the hologram to change its appearance as viewers shift their perspectives, facilitating dynamic experiences such as discovering hidden details or shifting reflections5. Unlike active interactions, where touch or voice commands directly manipulate the system, holography creates a more subtle yet immersive visual engagement.

One of the key strengths of holographic displays compared to other technologies is their ability to offer ‘true’ three-dimensional space without requiring special equipment like glasses6. This makes holograms particularly accessible and suited for collective viewing experiences, allowing multiple visitors to engage with the exhibit simultaneously without needing additional gear6. This contrasts with AR, which typically requires smartphones or headsets, and 3D films, which require special glasses to simulate depth.

Additionally, holographic displays create a sense of depth and realism, where the viewing experience is dynamic and changes naturally with the observer’s movement. In contrast, AR tends to overlay digital elements on top of the real world, which can sometimes detract from the depth perception of physical objects. VR, on the other hand, immerses the user in an entirely virtual environment, often isolating the visitor from the shared experience of others in a museum setting. Holography’s strength lies in its collective immersion, where multiple viewers can share the same exhibit in real time, each experiencing slightly different perspectives depending on their physical position7. This feature makes holography particularly effective for museums.

Dingli and Mifsud highlighted the effectiveness of holograms in capturing visitors’ attention and prolonging their interaction time compared to traditional display methods4. Their study revealed that holographic exhibits foster greater levels of active engagement, such as virtual dialogues and exploratory behaviour. Moreover, the research emphasised the role of holograms in strengthening visitors’ memory retention and emotional connection to the exhibits, particularly when presenting complex historical or cultural narratives. Johnston emphasised that holography can create highly accurate, three-dimensional replicas of artefacts, enabling museums to display fragile or inaccessible objects while maintaining their authenticity58. More recently, Liu et al. advanced the concept of mobile holographic museums as a means of overcoming spatial limitations and enhancing accessibility. Their study highlighted how holographic display technology, when integrated into flexible mobile exhibition design, can deliver cultural artefacts directly to community settings. Such systems allow contact-free, multi-angle viewing of exhibits, significantly increasing interactivity and immersion while maintaining the integrity of fragile collections59.

A recent study has also explored the educational and creative potential of holography in museum-related product design. For instance, a design-driven project based on a Bronze Sitting Dragon artefact from the Capital Museum of China demonstrated how holographic cultural and creative products can extend the museum experience beyond traditional exhibitions60. By integrating holographic technology into product interaction, visual storytelling, and educational engagement, the design allowed users to access multisensory content in a more accessible and playful format. This approach fosters public interest in cultural heritage and enhances cognitive engagement through novel visual formats and interactive functions, particularly among younger or non-traditional museum audiences.

Building on these findings, empirical studies have further explored the impact of holography on visitor engagement, providing additional evidence for its effectiveness in enhancing museum experiences. For example, Xu eth al. investigated emotional engagement with holographic displays7. During the interviews, participants were presented with a comparison of the physical object, its photograph, and a holographic display of the Red Jasper Intaglio Caracalla (Fig. 3). Insights were gathered through interviews with 13 individuals possessing expertise in arts, design, or museology and were analysed using TF-IDF to identify key emotional responses. Curiosity and amazement were the most frequently reported emotions, highlighting holography’s potential to captivate and engage visitors. Visitors also noted that the realism and three-dimensionality of the holograms deepened their emotional connection to the exhibits, with the interactivity of the holograms, adjusting dynamically based on the viewer’s perspective, praised for stimulating exploration. Participants further indicated a long-term impact on their interest in future museum visits and an increased likelihood of recommending holography.

Red Jasper Intaglio Caracalla’s Hologram in Trimontium Museum, Melrose, Scottish Borders7.

Furthermore, holography offers museums the opportunity to display fragile or inaccessible artefacts in new ways. With full-colour holograms, museums can present highly realistic reproductions of valuable or delicate objects that may otherwise be stored away due to preservation concerns. This ability to create lifelike reproductions not only preserves the integrity of rare objects but also democratises access, allowing more visitors to engage with these exhibits up close without risking damage to the original artefacts10.

Holography: a bridge between art, science, and museum preservation

Holography represents an integration of scientific innovation and artistic creativity, offering new possibilities for museum displays9. As demonstrated in digital holographic applications, this technology enhances the presentation of historical artefacts by combining scientific precision with aesthetic expression, thereby stimulating viewer perception and creating a deeper connection between audiences and cultural heritage.

Museums are experimenting with using 3D composite images and holographic technology in practical applications. Frequently, museum collections contain many objects that cannot be displayed for a variety of reasons, such as gallery constraints, fragile artefacts, renovation costs, or the loss or destruction of objects. These problems can be resolved by replacing real objects with holograms, which can also be combined with existing parts of the collection (remnants). This method can be utilised for collections with missing or damaged parts. The use of full-colour holograms alongside the collection conducted the physical parts complement the images and gave a complete experience of viewing the entire collection11. High insurance costs of valuable artefacts also limit museums on what they can feasibly display, an obstacle rendered moot by holographic technology, with the added advantage of mobility to protect the original artefact from dangerous journeys between museums61.

For example, the Byzantine and Christian Museum BXM (Athens) has collaborated with the Hellenic Institute of Holography HiH (Hellenic Institute OF Holography) to document its collection of 12 objects in the form of OptoClones™ (a type of colour hologram of the Denisyuk type) from his collection (Fig. 4)10.

Left: Photograph of the OptoClone-BXM1, two pairs of golden earrings, 4th c AD. Right: Photograph of the OptoClone-BXM6, silver earrings, 4th c. AD10.

The full-colour holograms are on display as part of the museum’s permanent collection, and some have been loaned abroad to replace the originals. As Nikos Konstantios, an archaeologist and museologist at the Byzantine and Christian Museum (BXM), elaborated on this decision: “Our choice to use hologram displays, rather than other digital media technologies, as a visual substitute for selected objects on temporary loan, was rooted in the belief that panchromatic holography’s surreal, one-to-one, three-dimensional optical representation allows viewers to form an accurate perception of the object, even in the absence of the original artefact. This realistic perception is immediately evident upon a viewer’s first encounter with the hologram”10.

Holograms can be utilised to present museum artefacts with high visual accuracy, sometimes making it difficult for viewers to distinguish between a holographic reproduction and the original object9. In the field of cultural heritage, holography has demonstrated potential in two key areas9. Firstly, it serves as a visualisation tool, allowing for the display of digital replicas of fragile artefacts that may otherwise be inaccessible to the public. Secondly, it offers a scientific approach to preservation, enabling researchers to document and reconstruct artefacts before further degradation occurs.

One example of using holography to preserve historical artefacts is the Fabergé Museum in Baden Germany. In 2014, under the assistance of the Mechanics and Optics (ITMO) of Saint Petersburg National Research University of Information Technologies, The Fabergé Museum produced five unique, almost identical holographic optical replicas of 13 selected works of art from the museum, Fig. 5 shows a holographic image of Fabergé Imperial Eggs10.

Holographic Coronation Imperial Easter Egg (Left) and the Rosebud Imperial Egg (Right)10.

In addition to using holographic optical reproductions as an alternative form of exhibition, technology and digitisation also allow museums to share their collections with the public differently. It is well known that many museum collections may be difficult to display and move for various reasons, and even if they can, it is difficult for visitors to see the collections from all angles. Therefore, holography technology has also been utilised to archive and exhibit rare and high-value cultural relics. For example, the Llangollen Museum displayed a Bronze Age axe and its holographic image together (Fig. 6). Holography technology provides the possibility of essentially copying cultural relics and has reached the point where the viewer can hardly tell whether or not they are looking at the real exhibits or holographic copies. Although holographic reproductions can never replace the actual value of physical works of art, it enables museums to achieve one of their most important functions - maintaining the display of exhibits. Analog holography provides a means to preserve the unprecedented microscopic details of faithful visual records, and holography can also help museums to hold itinerant exhibitions.

The Bronze Age axe (down) and its holographic image (top) in Llangollen Museum9.

In 2016, Dr Shuo Wang explored the potential of digital holography as a creative medium for displaying museum artefacts and enhancing their contextual appreciation. This research aimed to utilise digital holographic printing as an innovative technique to recover and represent detailed impressions of cultural relics, contextualising them in their original and discovered environments9.

Collaborating with Jiangxi Gao’an Museum, Wang applied holographic modelling to Yuan blue-and-white porcelains. Due to the museum’s limitations, the collections lacked comprehensive digital scans and primary data. To overcome this, Wang reconstructed 3D models in Maya software using photographic data and dimensional records, employing the “4RE” method (redefinition, recreation, reconstruction, representation) to optimise digital holographic printing9. As shown in Fig. 7, the Yuan blue-and-white porcelain artefacts were digitally reconstructed using Maya software. The simulated 3D models accurately represent the objects’ textures and material properties, ensuring a realistic visualisation for holographic printing.

A view of the simulated Yuan blue-and-white porcelains with texturing in Maya9.

Dr Wang digitally modelled the porcelain artefacts by extracting texture maps from photographs, applying realistic material rendering, and simulating authentic lighting conditions. Furthermore, he introduced Holomontage, a new artistic form that integrates multiple holographic perspectives to create dynamic, narrative-driven museum displays9. Figure 8 illustrates the concept of Holomontage, which integrates multiple stages of the porcelain’s manufacturing process into a single holographic composition. This approach enables viewers to experience a narrative-driven reconstruction of the artefacts.

The simulated scene of a digital hologram montage, representing stages in manufacture in this case9.

One significant outcome was a holographic artwork portraying the excavation site where the largest quantity of Yuan blue-and-white porcelain had been found. The final 4RE-based display methodology provided audiences with unprecedented access to these artefacts, offering both archaeological and artistic reinterpretations9. This holographic installation was successfully exhibited in Beijing in 2016, where public reaction was overwhelmingly positive, demonstrating the potential of digital holography for artistic and hybrid artistic-factual displays. Figure 9 depicts the exhibition set up in Beijing, where artificial soil was used to create a contextual environment surrounding the holographic display. This immersive installation provided visitors with a novel way to engage with the artefacts.

The artificial soil surrounding the hologram9.

One notable application of holography in museums is the “Bringing the Artifacts Back to the People” project, led by the Centre for Modern Optics in collaboration with several museums, including the British Museum and the National Museum of Wales62. The project employed colour holography to create ultra-realistic, three-dimensional images of rare and fragile artefacts, making them accessible to a wider audience through a touring exhibition. Among the recorded artefacts was a 14,000-year-old decorated horse jaw bone from the Ice Age, held at the British Museum in London (Fig. 10). The Denisyuk colour reflection hologram technique enabled the creation of lifelike holograms displayed in several museums across North Wales (Fig. 11). This allowed the public to experience highly detailed, three-dimensional replicas of the original artefacts in locations where the physical objects could not be exhibited due to preservation concerns.

Horse jaw bone recording setup62.

Hans I. Bjelkhagen next to the Horse Jaw hologram62.

The integration of holography in museum object display has demonstrated significant potential in overcoming traditional constraints related to artefact preservation, accessibility, and visitor engagement. Case studies such as the “Bringing the Artifacts Back to the People” project and the OptoClone™ initiative illustrate how holography enables museums to present highly detailed, realistic reproductions of fragile or inaccessible objects. Additionally, projects like the Fabergé Museum holographic replication showcase how museums can use holography to extend the reach of their collections while maintaining an authentic visual experience. These implementations highlight the growing acceptance of holographic displays as a viable tool in cultural heritage preservation.

Conclusions

Holographic technology has emerged as a transformative tool in museum exhibition design, offering an innovative approach to enhancing visitor engagement and perception. This review has examined the impact of holographic displays on museum experiences, highlighting their ability to create immersive, interactive, and emotionally engaging environments. By leveraging advanced optical techniques, holography provides an unparalleled sense of depth and realism, surpassing traditional two-dimensional and digital display methods5.

The integration of holographic displays in museums has influenced visitor perception, fostered emotional connections with artefacts, and enhanced learning outcomes7. Unlike conventional exhibition formats, which rely heavily on static representations, holography enables dynamic and participatory experiences that align with contemporary expectations of digital interactivity. The technology’s ability to present artefacts in three-dimensional space without the need for additional viewing devices also enhances accessibility and collective engagement within exhibition spaces6.

Despite its advantages, several challenges remain in the widespread adoption of holography in museums. High implementation and maintenance costs, technical constraints such as viewing angles and resolution limitations, and concerns regarding the authenticity of digital reproductions continue to pose barriers6. Additionally, the long-term sustainability and scalability of holographic applications require further investigation to ensure their viability as a standard exhibition practice.

Future research should focus on refining the technical aspects of holography to enhance its accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and integration within diverse museum settings. Existing studies predominantly employ subjective research methods, lacking objective, data-driven approaches. Future research could explore a broader participant base, diverse holographic designs, and integrating physiological measures (e.g., EEG, heart rate) to complement self-reported emotional responses. Empirical studies evaluating visitor engagement, cognitive processing, and emotional responses to holographic exhibits would further substantiate the technology’s efficacy in cultural heritage interpretation. Furthermore, interdisciplinary collaboration between curators, designers, and technologists will be essential in developing holographic experiences that complement rather than replace traditional museum practices.

As museums continue to embrace digital innovation, holography presents a compelling opportunity to redefine audience interaction with cultural heritage. While current implementations illustrate its potential, further advancements and critical evaluations will be necessary to fully realise its role in shaping the future of museum experiences.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Elgammal, I., Ferretti, M., Risitano, M. & Sorrentino, A. Does digital technology improve the visitor experience? A comparative study in the museum context. Int. J. Tour. Policy 10, 47–67, https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTP.2020.107197 (2020).

International Council of Museums. The Future of Museums in Rapidly Changing Communities. International Council of Museums. Available at: https://icom.museum/en/news/international-museum-day-2025-the-future-of-museums-in-rapidly-changing-communities/ (accessed 21 July 2025).

Lian, T. Expansion of the Functions of Art Museum Spaces in the Digital Era. J. Humanities, Arts Soc. Sci. 7, 906–908, https://doi.org/10.26855/jhass.2023.05.004 (2023).

Dingli, A. & Mifsud, N. Using holograms to increase interaction in museums. In Advances in Affective and Pleasurable Design (eds. Chung, W. & Shin, C. S.) 117–127 (Cham: Springer, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41661-8_12.

Barabas, J. & Bove, V. M. Visual perception and holographic displays. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 415, 012056, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/415/1/012056 (2013).

Pi, D., Liu, J. & Wang, Y. Review of computer-generated hologram algorithms for color dynamic holographic three-dimensional display. Light.: Sci. Appl. 11, 231, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-022-00916-3 (2022).

Xu, Z., Wang, S., Sun, D. & Xia, G. An investigation into emotional engagement of holography for museum display. In International Workshop on Holography and Related Technologies (IWH2022 & 2023) (X. Tan, X. Lin, T. Shimura, M. Gu & Y. Yang, eds.) Proc. SPIE, 32 (Fuzhou, China: SPIE, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3024851.

Bjelkhagen, H. I. & Crosby, P. G. Color holography and its use in display and archiving applications. In IS&T Archiving Conference Proceedings 239–245 https://doi.org/10.2352/issn.2168-3204.2008.5.1.art00049 (2008).

Wang, S., Osanlou, A. & Excell, P. S. Case study: Digital holography as a creative medium to display and reinterpret museum artifacts, applied to Chinese porcelain masterpieces. In Research and Development in the Academy, Creative Industries and Applications 65–88 (Cham: Springer, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54081-8_6.

Sarakinos, A. & Lembessis, A. Color holography for the documentation and dissemination of cultural heritage: OptoClones™ from four museums in two countries. J. Imaging 5, 59, https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging5060059 (2019).

Markov, V. B. Holography in museums. Imaging Sci. J. 59, 66–74, https://doi.org/10.1179/174313111X12966579709197 (2011).

Ambs, P., Huignard, J.-P. & Loiseaux, B. Holography. In Encyclopedia of Condensed Matter Physics (F. Bassani, G. L. Liedl & P. Wyder, eds.) 332–341 (Oxford: Elsevier, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-12-369401-9/00610-0.

Johnston, S. Holographic visions: A history of new science (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

Boone, P. M. NDT techniques: Laser-based. In Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology (K. H. J. Buschow et al., eds.) 6018–6021 (Oxford: Elsevier, 2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043152-6/01059-7.

Pepper, A. Holography, applications | Art holography. In Encyclopedia of Modern Optics (R. D. Guenther, ed.) 25–37 (Oxford: Elsevier, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-12-369395-0/01248-3.

Zhao, R., Huang, L. & Wang, Y. Recent advances in multi-dimensional metasurface holographic technologies. PhotoniX 1, 20, https://doi.org/10.1186/s43074-020-00020-y (2020).

Tahara, T., Quan, X., Otani, R., Takaki, Y. & Matoba, O. Digital holography and its multidimensional imaging applications: A review. Microscopy 67, 55–67, https://doi.org/10.1093/jmicro/dfy007 (2018).

Blinder, D. et al. Signal processing challenges for digital holographic video display systems. Signal Process.: Image Commun. 70, 114–130, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.image.2018.09.014 (2019).

Oliveira, S. & Richardson, M. The future of holographic technologies and their use by artists. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 415, 012007, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/415/1/012007 (2013).

National Museum of American History. Hologram of Toy Train. Smithsonian Institution. https://americanhistory.si.edu/it/collections/object/nmah_1448340 (accessed 29 May 2025).

Jelinčić, D. A. & Šveb, M. Visual stimuli cues with impact on emotions in cultural tourism experience design. Acta Turistica 33, 39–74, https://doi.org/10.22598/at/2021.33.1.39 (2021).

Jelinčić, D. A., Šveb, M. & Stewart, A. E. Designing sensory museum experiences for visitors’ emotional responses. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 37, 513–530, https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2021.1954985 (2022).

Khalid, H. M. & Helander, M. G. Customer emotional needs in product design. Concurrent Eng. 14, 197–206, https://doi.org/10.1177/1063293X06068387 (2006).

Benyon, M. Holography as an art medium. Leonardo 6, 1, https://doi.org/10.2307/1572418 (1973).

Valyi-Nagy, Z. Feeling into Paula Dawson’s Holograms. Art. J. 81, 14–26, https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.2022.2040240 (2022).

Xu, Z., Sun, D., Xia, G. & Wang, S. Exploring emotional and cognitive engagement with holographic displays in museums. ACM J. Comput. Cultural Herit. 18, 1–24, https://doi.org/10.1145/3736772 (2025).

Zhai, T., Song, Q., Liao, E., Tam, A. M. W. & Zhu, J. An approach for holographic projection with higher image quality and fast convergence rate. Optik 159, 211–221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2018.01.055 (2018).

Kotchoubey, B. Human consciousness: Where is it from and what is it for. Frontiers in Psychology 9 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00567 (2018).

Farkas, T., Wiseman, S., Cairns, P. & Fiebrink, R. A grounded analysis of player-described board game immersion. In Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play (CHI PLAY ’20), 427–437 (ACM, Virtual Event Canada, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1145/3410404.3414224.

Wei, S., Yang, J. & Wang, S. Emotional effects of various display lightings on holograms. In International Conference on Optical and Photonic Engineering (icOPEN 2024). Proc. SPIE 13509, 284–289, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3057955 (2025).

Menning, M. & Piper, J. A. Holography as a medium for the confluence of art and science. Proc. SPIE 4149, 9, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.402489 (2000).

Mrongovius, M. The emergent holographic scene: Compositions of movement and affect using multiplexed holographic images. PhD thesis, RMIT University (2012). Available at: https://research-repository.rmit.edu.au/articles/thesis/The_emergent_holographic_scene_compositions_of_movement_and_affect_using_multiplexed_holographic_images/27586290?file=50758212.

Recupero, A., Talamo, A., Triberti, S. & Modesti, C. Bridging Museum mission to visitors’ experience: activity, meanings, interactions, technology. Front. Psychol. 10, 2092, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02092 (2019).

Addis, M., Copat, V. & Martorana, C. Museum experience and its impact on visitor reactions. J. Philanthr. Mark. 29, e1826. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1826 (2024).

Vila, D. Speaking volumes: Studying depth in holographic narratives. Arts 9, 1, https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010001 (2019).

Hammady, R., Ma, M., Al-Kalha, Z. & Strathearn, C. A framework for constructing and evaluating the role of MR as a holographic virtual guide in museums. Virtual Real. 25, 895–918, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-020-00497-9 (2021).

Pietroni, E., Ferdani, D., Forlani, M., Pagano, A. & Rufa, C. Bringing the illusion of reality inside museums—A methodological proposal for an advanced museology using holographic showcases. Informatics 6, 2, https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics6010002 (2019).

Cvetkovich, T. Holography at the Butler Institute of American Art. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 415, 012016, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/415/1/012016 (2013).

Lu, L. & Bilian, K. Research progress in visual fatigue related to stereoscopic video display terminals. J. Shanghai Jiao Tong Univ. (Med. Sci.) 43, 1038, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-8115.2023.08.012 (2023).

Urey, H., Chellappan, K. V., Erden, E. & Surman, P. State of the art in stereoscopic and autostereoscopic displays. Proc. IEEE 99, 540–555, https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2010.2098351 (2011).

Haleem, A., Javaid, M., Singh, R. P., Suman, R. & Rab, S. Holography and its applications for industry 4.0: An overview. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2, 42–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iotcps.2022.05.004 (2022).

Gentet, Y. & Gentet, P. CHIMERA, a new holoprinter technology combining low-power continuous lasers and fast printing. Appl. Opt. 58, G226–G230, https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.58.00G226 (2019).

Chao, B., et al. Large étendue 3D holographic display with content-adaptive dynamic Fourier modulation. In Proceedings of SIGGRAPH Asia 2024 Conference Papers 1–12 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1145/3680528.3687600.

Sylaiou, S. et al. Exploring the educational impact of diverse technologies in online virtual museums. Int. J. Arts Technol. 10, 58, https://doi.org/10.1504/IJART.2017.083907 (2017).

Florescu, O., Sandu, I. C. A., Spiridon-Ursu, P. & Sandu, I. Integrative participatory conservation of museum artefacts: Theoretical and practical aspects. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 11, 109–116 (2020) Available at: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/integrative-participatory-conservation-museum/docview/2606197125/se-2

Pietroni, E., d’et al. Beyond the museum’s object: Envisioning stories. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies 10118–10127 (Barcelona, Spain, 2017). https://doi.org/10.21125/edulearn.2017.0915.

Choi, H.-S. & Kim, S.-H. A content service deployment plan for metaverse museum exhibitions: Centering on the combination of beacons and HMDs. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 37, 1519–1527, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.04.017 (2017).

Paris, S. G. (ed.) Perspectives on Object-Centered Learning in Museums (Routledge, New York, 2002). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410604132.

Kosmopoulos, D. & Styliaras, G. A survey on developing personalized content services in museums. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 47, 54–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmcj.2018.05.002 (2018).

Neuburger, L. & Egger, R. An afternoon at the museum: Through the lens of augmented reality. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2017 (eds. Schegg, R. & Stangl, B.) 241–254 (Springer, Cham, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51168-9_18.

Antón, C., Camarero, C. & Garrido, M.-J. A journey through the museum: Visit factors that prevent or further visitor satiation. Ann. Tour. Res. 73, 48–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.08.002 (2018).

Packer, J. Beyond learning: Exploring visitors’ perceptions of the value and benefits of museum experiences. Curator.: Mus. J. 51, 33–54, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2008.tb00293.x (2008).

Radder, L. & Han, X. An examination of the museum experience based on Pine and Gilmore’s experience economy realms. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 31, 455, https://doi.org/10.19030/jabr.v31i2.9129 (2015).

Harrison, P. & Shaw, R. Consumer satisfaction and post-purchase intentions: An exploratory study of museum visitors. Int. J. Arts Manag. 6, 23–32 (2004). Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41064817

Prebensen, N. K. & Foss, L. Coping and co-creating in tourist experiences. Int. J. Tour. Res. 13, 54–67, https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.799 (2011).

International Council of Museums. #IMD2019 Museums as cultural hubs: The future of tradition. International Council of Museums (2019). Available at: https://icom.museum/en/news/imd2019-museums-as-cultural-hubs-the-future-of-tradition/ (Accessed 22 Feb. 2025).

Todorova, Z. From exhibiting artifacts to installing digital holograms, museums are moving into the future through technological innovation. Innovative Inf. Technol. Econ. Digitalization ((IITED)) 1, 275–281 (2024). Available at: https://ideas.repec.org/a/nwe/iitfed/y2024i1p275-281.html

Johnston, S. F. Why display? Representing holograms in museum collections. In Illuminating Instruments (eds. Morris, P. & Staubermann, K.) 97–116 (2009).

Li, J. et al. Design and application of holography in mobile museums. In International Conference on Optical and Photonic Engineering (icOPEN 2024). Proc. SPIE 13509, 314–319, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3058010 (2025).

Liang, Z., Wu, J., Wang, S. & Ma, X. Educational holographic cultural and creative product design for museums. In International Conference on Optical and Photonic Engineering (icOPEN 2024). Proc. SPIE 13509, 302–307, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3057999 (2025).

Bjelkhagen, H. I. Ultra-realistic 3-D imaging based on colour holography. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 415, 012023, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/415/1/012023 (2013).

Bjelkhagen, H. & Osanlou, P. Color holography for museums: Bringing the artifacts back to the people. Proc. SPIE – Int. Soc. Optical Eng. 7957, 79570B, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.872101 (2011).

Acknowledgements

Zhan Xu gratefully acknowledges the University of Liverpool for supporting the open-access publication fee. Sincere thanks are also extended to the co-authors for their insightful feedback and guidance throughout the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.X. was responsible for the conception and design of the study, conducted the literature review, and drafted the manuscript. D.S., G.X., and S.W. provided academic supervision throughout the research process, offered critical revisions, and contributed to improving the manuscript’s clarity, structure, and scholarly quality.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Z., Sun, D., Xia, G. et al. A review of holographic technology in museums: enhancing visitor perception and engagement. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 508 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02051-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02051-9