Abstract

Tibetan Buddhism has deeply influenced the political, cultural, and spatial fabric of the Tibetan Plateau. Among its various traditions, the Sakya school is notable for its early theocratic regime. However, the temporal and spatial evolution of its monasteries—as key vehicles for the school’s spread—and the quantitative mechanisms behind their distribution remain unclear. This study combines GIS-based spatial analysis with interpretable machine learning (LightGBM-SHAP) to identify the key natural and human factors shaping Sakya monastery distribution. Emphasis is placed on capturing nonlinear interactions among variables to uncover deeper spatial patterns. Results reveal that human factors—particularly historical population, settlement density, and the presence of other sects—exert a stronger influence than natural conditions. The findings underscore the complex socio-political dynamics embedded in monastic diffusion and highlight the potential of explainable machine learning for advancing research in historical GIS (HGIS) and religious geography.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Buddhism, one of the world’s three major religions1, was founded over 2500 years ago by Siddhārtha Gautama (Shakyamuni), a prince of Kapilavastu in ancient India2. Based on its regional transmission and canonical traditions, Buddhism is generally divided into Southern and Northern Buddhism3,The latter further encompasses Chinese (Han) Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism emerged through the integration of Indian Buddhist teachings with the indigenous Bon religion after entering the Tibetan Plateau4, while also absorbing elements from Chinese Buddhism. As a product of cross-cultural exchange among China’s diverse ethnic groups and regions, Tibetan Buddhism is predominantly found in western China—particularly in Tibet, Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Inner Mongolia—and is also widespread in neighboring countries such as Mongolia, Nepal, and Bhutan.

Following the persecution of Buddhism under King Langdarma in the 9th century, Tibetan Buddhism entered the period known as the “Later Diffusion” (phyi dar). During this era, the diversity of Indian Buddhist lineages, the distinctive doctrines and practices of key masters, geographic isolation, and the patronage of secular political powers all contributed to the emergence of multiple religious schools. Today, Tibetan Buddhism comprises five major traditions: Gelug, Sakya, Nyingma, Kagyu, and Bon. Among them, the Sakya tradition was the earliest to expand into both the Chinese heartland and Mongolia. It is notable not only for its distinctive doctrinal system but also for its significant political role. In the 13th century, with support from the Yuan dynasty, the Sakya school established the first theocratic regime in Tibetan history5, marking a pivotal moment in the integration of religious and secular authority. Against this backdrop, Sakya monasteries functioned not only as centers of religious practice but also as spatial nodes of political administration. This dual role means that the location and spatial organization of Sakya monasteries were shaped by a complex interplay of religious, political, geographical, and social factors. As a paradigmatic example of church-state integration, the Sakya monastic system offers a representative case for understanding the spatial dynamics and formation mechanisms of religious landscapes on the Tibetan Plateau. Based on a geospatial database of Gelug monasteries, Chao et al. analyzed their multi-scale spatial patterns across Tibetan-inhabited regions6, and constructed a hierarchical diffusion model to reconstruct the expansion network and spatial dynamics of the Gelug tradition7. By contrast, studies on the Sakya tradition have primarily emphasized its historical development, doctrinal system, and political-religious relations8,9,10, While some scholars have examined the spatiotemporal characteristics of Sakya monasteries11,12, these efforts have largely remained qualitative and focused on limited regional contexts. A systematic, spatially comprehensive dataset of Sakya monasteries across the Tibetan cultural region has yet to be developed, and the spatial patterns and underlying drivers of their distribution remain insufficiently understood.

With the rapid advancement of Geographic Information Systems (GIS), their powerful spatial data processing and analytical capabilities have been increasingly applied across a wide range of disciplines. Religious sites such as Tibetan Buddhist monasteries are often closely tied to specific geographic settings, natural environments, and socio-economic conditions, making GIS, remote sensing, and spatial statistics inherently well-suited for research in religious geography13. A growing body of research has applied GIS methods to the study of religious geography. In the context of Tibetan Buddhism, Fang et al.14,15 employed various GIS-based spatial analyses to qualitatively and quantitatively investigate the distribution patterns and driving factors of monasteries in the Amdo and Ü-Tsang regions. Chen et al.16 proposed a digital framework for historical geographic information systems and demonstrated its feasibility using Tibetan monasteries in China as a case study. GIS methodologies have also been applied in the study of other religious traditions, including Islam17,18, Christianity19,20, and Hinduism21,22. However, conventional GIS approaches face limitations in capturing complex driving mechanisms, particularly in identifying high-order nonlinear relationships and multifactor interactions. These limitations risk oversimplifying the processes underlying religious spatial patterns and may obscure the influence of critical variables. To address this, integrating machine learning with GIS offers a more powerful modeling framework capable of handling such complexity. Interpretable machine learning methods, in particular, can enhance understanding by quantifying the relative importance and interaction of influencing factors23,24,25, thereby providing a more comprehensive and robust foundation for spatial analysis in religious studies.

Despite their strong predictive performance, many machine learning models often achieve accuracy at the expense of interpretability26. Recent advances in interpretable machine learning have addressed this issue, enabling a better understanding of complex model behavior27. Among these, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) has emerged as a powerful tool for enhancing model interpretability. An increasing number of studies have integrated SHAP with machine learning models in GIS-related research. For instance, Li28 used SHAP to interpret spatial effects derived from an XGBoost model; Ke et al.29 proposed a GeoXAI framework to explore the nonlinear spatial heterogeneity of urban flood drivers; and Zhang et al.30 applied a SHAP-XGBoost framework to investigate the geospatial determinants of landslide susceptibility. In this study, we adopt interpretable machine learning techniques to quantitatively assess the driving factors behind monastery distribution. This approach helps uncover the mechanisms of key influencing variables, deepens our understanding of the spatial patterns of Sakya monasteries, and contributes a novel methodological paradigm to the field of historical GIS.

This study seeks to address the following key questions: What are the primary factors influencing the spatial distribution of Sakya monasteries across Tibetan-inhabited regions? Do these factors exhibit spatial heterogeneity in different areas? To answer these questions, we adopt an interdisciplinary approach that integrates historical documents, religious archives, and field surveys to construct a geospatial database of Sakya monasteries. We analyze their spatial patterns and clustering characteristics, and further apply machine learning models combined with SHAP-based interpretability analysis to quantitatively assess the nonlinear effects and spatial heterogeneity of both natural and socio-cultural drivers shaping monastery distribution.

Methods

Study area

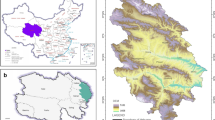

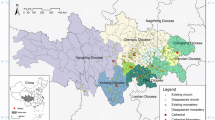

This study focuses on the Tibetan-inhabited areas of China (Fig. 1), encompassing Tibetan communities across five provinces: Tibet Autonomous Region, Sichuan, Yunnan, Qinghai, and Gansu. Covering approximately 2.25 million square kilometers, the region is characterized by towering mountains and snow-capped peaks, with an average elevation exceeding 4000 m. Its distinctive geographic conditions have given rise to a unique cultural, religious, and social landscape.

Historically, during the Yuan dynasty, the Tibetan region was divided into three major cultural areas—Ü-Tsang, Kham, and Amdo—based on geography, dialects, and historical context. Ü-Tsang is the cultural heartland of Tibetan Buddhism, often referred to as “Dharma Land of Ü-Tsang”. It includes the traditional subregions of U (central Tibet, including areas like Shigatse and Ngari) and Tsang (western Tibet). Kham, also known as “Land of the People”, lies between Amdo and Ü-Tsang in the Hengduan Mountains and the deep river valleys of the Jinsha and Yalong rivers. Amdo, referred to as “Land of Horses”, occupies the northeastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau and spans parts of Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, and adjacent areas of Tibet, characterized by its high-altitude grasslands and rugged terrain.

Data sources

All datasets used in this study and their sources are listed in Table 1, covering multiple dimensions including monastery geographic information, natural environmental factors, and historical-cultural background. All data were standardized to the WGS-84 geographic coordinate system and projected using UTM.

The core dataset is derived from the Historical Geographic Information System of Tibetan Buddhist Monasteries developed by our research team16. This database was compiled through systematic integration of diverse historical sources, including historical documents, religious archives, local gazetteers, oral histories, and results from field surveys. Data entry followed a unified coding system and GIS standard formats, resulting in a vector dataset containing information on 3660 monasteries from historical periods to the present across Tibetan-inhabited regions. Attributes include monastery name, geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude), founding date, sect affiliation, size category, partial records of parent-subsidiary monastery relationships, and historical conversion information. In this study, we extracted 310 monasteries explicitly affiliated with the Sakya sect as the study sample.

Administrative boundary data (2024 version) were obtained from the National Geoinformation Public Service Platform (Tianditu) and used to delineate the boundaries of Tibetan-inhabited areas, as well as to support regional-scale clustering and correlation analyses.

Natural factor data include: (a) Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data obtained from the National Geomatics Center of China (www.webmap.cn), used to derive elevation, slope, and aspect; (b) River system data from the China Historical GIS (Fudan University), dated to 1820 and in vector format, used to calculate the shortest distance from each monastery to major rivers; (c) Climate data, specifically mean annual temperature31 and precipitation32 for the year 1901, sourced from the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Human factor data include: (a) Monastery data for other sects (Gelug, Nyingma, Kagyu, and Bon) were extracted from the same historical geographic database as the Sakya data, comprising over 3300 non-Sakya monasteries, and were used for subsequent density estimation and inter-sect spatial interaction analyses; (b) Historical settlement data from the China Historical GIS platform for the year 1820, verified through manual checks and used for kernel density estimation to represent settlement density patterns within Tibetan-inhabited regions; (c) Tea Horse Road data from the Institute for Quantitative Social Science, Harvard University, representing vector route data for 1820, from which primary and secondary routes were extracted to calculate the shortest distance from each monastery to the nearest route; (d) Historical population density data for 1820, obtained from HYDE 3.3 (History Database of the Global Environment) published by Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

Analytical framework and methods

This study establishes a progressive analytical framework of “data integration-spatial analysis-mechanism exploration” to systematically examine the spatial distribution and underlying mechanisms of Sakya monasteries. The framework consists of three interrelated components. First, a geographic information database of Sakya monasteries in Tibetan Buddhism was constructed by integrating data from historical records, field investigations, social media platforms, and geographic information platforms. Second, GIS-based spatial analytical techniques, including descriptive statistics, kernel density estimation, nearest neighbor analysis, local Moran’s I, and multi-distance spatial clustering analysis, were employed to assess the spatial distribution and clustering of monasteries. All natural and human variables were statistically extracted based on the monastery point data to analyze the distributional patterns under different influencing factors. Third, machine learning algorithms were introduced to further explore the relationships between monastery distribution and its driving factors. SHAP values were used to interpret the models, enabling the quantification of the overall importance and local contributions of each variable. The technical framework of this study is illustrated in Fig. 2.

To conduct the spatial analysis, a variety of statistical methods were employed. First, Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) is a non-parametric spatial statistical method used to visualize the density distribution of point data. In this study, KDE was applied to generate spatial density surfaces for monasteries, which helped us identify potential hotspots across the Tibetan cultural region and provided input variables for subsequent analyses. The following formulas define the calculation of point kernel density:

Here, \(i=1,\ldots ,n\) represents the input points, and only points within the radius distance from the location (x,y) are included in the summation; \({{dist}}_{i}\) denotes the distance between point \(i\) and the location (x,y); the radius refers to the search radius, also known as the bandwidth. The bandwidth is determined using Silverman’s empirical rule of thumb33.

Building on this, the Average Nearest Neighbor (ANN) method is a spatial statistical technique that assesses the overall spatial pattern of points by comparing the observed nearest neighbor distance to a random distribution34. We used ANN to provide an initial evaluation of the overall spatial pattern of Sakya monasteries, which served as a diagnostic basis for subsequent analyses. The calculation formula is as follows:

Here, \({\bar{D}}_{o}\) represents the observed average distance between each feature and its nearest neighboring feature, and \({\bar{D}}_{e}\) is the expected average distance between features under a random distribution model.

To further assess clustering and identify outliers, Anselin Local Moran’s I was utilized. It is a fundamental spatial statistical tool for identifying spatial clusters of features with similar values, as well as spatial outliers. In this study, Local Moran’s I was applied to identify spatial clusters of monasteries with comparable density levels in geographically adjacent areas, revealing local structural patterns and potential anomalies in the spatial distribution. The Local Moran’s I statistic for spatial association is calculated as follows:

where \({x}_{i}\) denotes the attribute value of feature \(i\), \(\bar{X}\) is the mean of the attribute across all features, \({w}_{i,j}\) is the spatial weight between features \({i}\) and \(j\), and \(n\) is the total number of features. Furthermore:

For examining patterns at different spatial scales, Multi-Distance Spatial Cluster Analysis (Ripley’s K Function) was employed. This method is a second-order spatial statistical tool used to quantify the spatial dependence between point features across different scales35. We used this method to examine the clustering or dispersion tendencies of monasteries at various scales, allowing us to explore variations in the spatial organization of Sakya monasteries across multiple geographic extents. In this study, we adopt a commonly used transformation of the original Ripley’s K function, known as L(d), defined by the following equation:

Where \(d\) denotes the distance threshold, \(n\) is the total number of features, and \(A\) represents the total area under study. The term \({k}_{i,j}\) refers to the weight assigned to the pair of points \(i\) and \(j\). In the absence of edge correction, \({k}_{i,j}=1\) if the distance between points \(i\) and \(j\) less than or equal to \(d\); otherwise, \({k}_{i,j}=0\). When an edge correction method is applied, the weights\(\,{k}_{i,j}\) are adjusted accordingly to account for boundary effects.

Beyond descriptive spatial statistics, the study also leveraged machine learning for mechanism exploration. Specifically, the LightGBM (Light Gradient Boosting Machine) model was introduced. LightGBM is an efficient gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT) framework designed to optimize computational speed and memory usage while maintaining high predictive accuracy. Compared with spatial regression models such as Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR), LightGBM does not rely on assumptions of linearity or stationarity, enabling it to flexibly capture complex non-linear relationships and high-order interactions among predictors. In contrast to XGBoost and Random Forest, LightGBM incorporates gradient-based one-side sampling (GOSS) and exclusive feature bundling (EFB), which significantly reduce computational time and memory requirements, making it particularly suitable for large-scale, high-dimensional, and sparse datasets36. Due to its efficiency and flexibility, LightGBM has been widely adopted across various tasks37,38,39,40. In this study, LightGBM was employed to model the relationships between the spatial distribution of Sakya monasteries and a wide range of natural and cultural-historical variables. Its ability to handle heterogeneous geographic data, accommodate imbalanced samples, and avoid overfitting makes it well-suited for historical GIS applications where variables operate at different spatial scales and exhibit complex, non-linear effects.

To interpret the complex outputs of the LightGBM model, we relied on the SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) framework. SHAP is a model interpretability framework grounded in cooperative game theory41, designed to elucidate the internal decision logic of complex machine learning models by quantifying the marginal contribution of each feature to an individual prediction. Based on Shapley value theory42, SHAP computes the average marginal effect of a feature across all possible subsets of input features, thereby fairly attributing the output variation to each input variable. Mathematically, the SHAP value \({\varphi }_{i}\) for feature \(i\) is defined as:

Here, \(F\) denotes the full set of features, \(S\) represents a subset of features excluding \(i\), and \({f}(S)\) is the model’s prediction based on the feature subset \(S\).

SHAP’s core advantages lie in its adherence to key axioms—local accuracy, consistency, and additivity—which collectively enable coherent interpretation of both global feature importance and local, instance-level prediction rationales43. Compared to traditional feature importance metrics such as permutation importance or the Gini index, SHAP ensures fair and consistent attribution of feature contributions via game-theoretic equilibrium principles, making it a powerful paradigm in model interpretability research. In this study, SHAP was applied to interpret the LightGBM model outputs by identifying both the global ranking of factor importance and localized effects under specific geographic contexts, thereby linking statistical findings with the spatial and cultural realities of Tibetan Buddhism.

Results

Spatial distribution characteristics of Sakya monasteries

Kernel density estimation was employed to analyze the spatial distribution of Sakya monasteries across multiple spatial scales. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the spatial distribution of Sakya monasteries exhibits significant multi-scale heterogeneity and spatial differentiation across the Tibetan regions. The observed density gradients and spatial configurations reflect not only the physical carrying capacity of the natural environment but also the spatial imprint of religious authority, economic structures, and cultural diffusion throughout history. The global-scale analysis reveals a clear overall pattern of “dense in the east, sparse in the west; concentrated in the south, scattered in the north.” High-density clusters are predominantly located in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau and the transitional zone of western Sichuan—regions adjacent to the core political and religious centers of Ü-Tsang. In contrast, the northeastern Qinghai-northern Tibet Plateau is characterized by fragmented, isolated distributions or low-density zones.

KDE is used here to visualize the spatial concentration and distribution patterns of monasteries across different regions. a KDE of monasteries in the entire Tibetan settlement area. b KDE of monasteries in the Ü-Tsang region. c KDE of monasteries in the Kham region. d KDE of monasteries in the Amdo region.

A scale-sensitive observation reveals distinct spatial structures across different Tibetan subregions. In the Kham region, a pronounced “one-core, one-belt” density pattern emerges. The eastern high-density nucleus is primarily located in the broad interfluvial valleys where the main and tributary streams of the Jinsha and Yalong Rivers converge. Here, the kernel density surface exhibits a feather-like dispersion extending southward, reflecting a “river corridor effect” in religious diffusion. These river-cut linear geographic corridors reduce transportation costs and facilitate cultural exchange, thus serving as primary axes for the expansion of the monastery network. Notably, the river valley segment housing Dezhuling Monastery and Gengqing Monastery—key Sakya institutions—shows an especially high-density peak. This area is also home to the historically significant Derge Printing House, one of the three great cultural centers of old Tibet44, underscoring the anchoring role of religious knowledge production hubs in faith-based geographies.

In the Ü-Tsang region, a tri-core distribution pattern reveals the historical imprint of politico-religious dynamics. Kernel density results suggest that monastery concentration diminishes progressively outward from the vicinity of Sakya Monastery in Shigatse, underscoring its central influence on the spatial organization of surrounding monasteries. Sakya Monastery holds a pivotal role in both Chinese history and the development of Tibetan Buddhism. Its library contains over ten thousand Buddhist texts, earning it the scholarly title of “the second Dunhuang”45. Other notable density peaks are observed in Gonggar County (Shannan Prefecture) and Saga County (Shigatse Prefecture), with many Sakya monasteries situated along the historical Tea Horse Road, reflecting a strategic alignment of religious authority with trade route control.

In the Amdo region, the formation of a dual-core pattern is marked by its function as a cultural transition zone. The eastern part of Amdo lies at the interface of Tibetan Buddhism and Han Chinese religious traditions. The region’s relatively low monastery density exemplifies the “embedded diffusion” of Tibetan Buddhism in peripheral zones. Furthermore, the sparse distribution of Sakya monasteries in Amdo reflects the diminishing influence of the sect with increasing distance from its politico-religious heartland, as well as the competitive displacement effect by the Gelug sect following the Yuan dynasty.

Beyond the analysis of distribution density, we also examined the spatial clustering patterns of the monasteries. We conducted an Average Nearest Neighbor (ANN) analysis on the spatial distribution of Sakya monasteries, yielding an ANN ratio of 0.30 (significantly less than 1) and a Z-score of −23.56 (p < 0.01). These results indicate a strong clustering tendency at the micro spatial scale, closely associated with the monasteries’ location preferences along valley corridors. Deep-cut river valleys on the Tibetan Plateau serve not only as key zones for agropastoral activities but also offer relatively flat terrain and thermal advantages, making them prime sites for religious settlement. The concentration of monasteries within these lower-altitude valleys helps circumvent ecological constraints imposed by alpine deserts—for instance, high monastery densities are observed along the wide middle reaches of the Yarlung Tsangpo River and the dry-hot valleys of the Jinsha River.

While the ANN method reflects the overall degree of spatial autocorrelation, we further employed the Anselin Local Moran’s I to examine clustering at the local scale. Monastery data were aggregated by county-level administrative units, and Local Moran’s I values were computed (Fig. 4). The results reveal significant high-high clustering zones in the eastern counties of the Kham region, whereas low-low clusters are predominantly found in the Amdo region. In the Ü-Tsang region, most counties show no significant clustering, though a few exhibit high-low outliers. Similar low-high and high-low anomalies are also identified in scattered areas of Kham.

The Ripley’s K function curve further reveals the hierarchical characteristics of multiscale spatial organization. As shown in Fig. 5, the observed K-values consistently exceed the upper bounds of the confidence interval across all distances, indicating that the distribution of Sakya monasteries exhibits structured clustering across multiple spatial scales. Notably, the difference between observed and expected values peaks at approximately 300 km, suggesting a geographic threshold in the spatial influence of core monasteries. Beyond this range, natural barriers such as the Nyenchen Tanglha and Hengduan Mountains, as well as historical political fragmentation, may have constrained the further spread of the sect’s influence-manifesting as a gradual attenuation of spatial autocorrelation. Overall, the curve demonstrates that as distance increases, the difference between observed and expected K-values first rises and then declines, with the strongest clustering observed at a distance of 300 km. This pattern suggests that Sakya monasteries exhibit the highest degree of spatial aggregation at this intermediate scale, reflecting both the geographic extent of religious diffusion and the constraints imposed by the plateau’s topography and historical-political landscape.

Analysis of influencing factors

From a historical perspective, the clustered spatial distribution of Sakya monasteries across the three major Tibetan regions—Ü-Tsang, Kham, and Amdo—is deeply intertwined with the sect’s politico-religious history, environmental conditions, and interactions with central authorities. This pattern can be interpreted through three primary dimensions:

First, the dual impetus of theocratic governance and Yuan imperial patronage significantly shaped the Sakya sect’s spatial expansion. In the 13th century, with support from the Yuan dynasty, Sakya established Tibet’s first theocratic regime. Among the Five Founding Masters of the Sakya tradition, the fourth, Sakya Pandita Kunga Gyaltsen, facilitated Tibet’s incorporation into the Yuan empire through the Liangzhou Talks. His nephew and successor, Drogön Chögyal Phagpa, was later appointed Imperial Preceptor by Kublai Khan and granted authority over the Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs. This political ascendancy enabled the Sakya sect to consolidate its religious and administrative control46, especially in Ü-Tsang, with Sakya Monastery at its core. Supported by imperial mandate, the monastery oversaw the extensive construction of a religious network centered on Shigatse. Concurrently, the Yuan government, through the Sakya hierarchy, extended its influence into Kham and Amdo. As Phagpa traveled between the Tibetan Plateau and the Yuan capital, he passed through Kham multiple times, leading to the conversion of several preexisting Bon, Nyingma, and Kadam institutions to Sakya. Additionally, disciples who had taken refuge in Sakya masters such as Phagpa established new monasteries, fueling the sect’s rapid expansion across Tibet.

Second, geographical seclusion and doctrinal continuity were crucial to the post-Yuan endurance of the Sakya tradition. After the 15th century, the decline of Sakya’s political power—marked by its displacement by the Pakmodrupa regime—led to a contraction of its influence in Ü-Tsang. In contrast, Kham and Amdo, located at the confluence of Sichuan, Qinghai, and Tibet, remained relatively autonomous due to their rugged topography and peripheral position in Tibetan polity. These regions often served as “ungoverned zones,” providing refuge for various religious traditions. Even Bon and Jonang, which had been largely marginalized elsewhere, managed to survive and thrive here. This geographical insulation offered Sakya a conducive environment for its doctrinal preservation and development. During the Ming period, although the Sakya school no longer wielded pan-Tibetan authority, it experienced a doctrinal renaissance marked by the emergence of the “Nine Ornaments” (sNar thang dge rgan dgu), a group of illustrious scholars dedicated to the revival and dissemination of Sakya teachings. This era witnessed the proliferation of sub-schools such as the Ngor, Tsar, Dzongpa, and Ewam traditions, which collectively contributed to the flourishing of the Sakya lineage across the broader Tibetan cultural sphere.

Third, the dissemination of Sakya teachings and their entanglement with regional polities formed a distinct mode of politico-religious interaction that profoundly shaped the spatial distribution of monasteries. In Ü-Tsang, Sakya Monastery administered lands and populations through the “Lhachang” system, comprising four major estates—Zhitok, Rinchengang, Lhakang, and Duchö—thereby establishing an integrated religio-economic structure where ecclesiastical and political authority were coextensive. In Kham, the Sakya-affiliated Örapa sub-school flourished under the patronage of the Derge chieftains, who founded Gongchen Monastery as their dynastic temple. This “church-state alliance” model facilitated the sect’s consolidation in the region. Gongchen Monastery remains the principal Sakya institution in Kham today and houses one of the most renowned printing houses in the Tibetan world, playing a pivotal role in the preservation and propagation of Buddhist texts and Tibetan culture. In Amdo, the Sakya sect relied on alliances with prominent local clans such as the Sina family and Mongol nobility to embed its teachings within the social fabric. Through these regional elites, Sakya managed to extend its influence beyond its traditional heartland. This pattern exemplifies a dual structure of “central-peripheral” governance: while the sect’s core institutions were concentrated in central Tibet, its survival and growth in the frontier zones of Kham and Amdo relied on adaptive, localized strategies.

Overall, the spatial pattern of Sakya monasteries essentially reflects their historical transformation from a “centralized” model to a “peripheral survival” mode. Building on this historical foundation, the distribution of monasteries is also closely linked to diverse natural and cultural conditions. To more comprehensively reveal these associations, this study adopts the geographical framework of “human-environment relations” and incorporates six natural factors and seven cultural factors for quantitative analysis.

In terms of natural factors, this study selects slope, aspect, distance to water bodies, mean annual temperature, and mean annual precipitation. Elevation, as a fundamental geographic variable under extreme high-altitude environments, is virtually synonymous with accessibility on the Tibetan Plateau47, exerting strong constraints and shaping effects on the distribution of Sakya monasteries. Statistical analysis reveals that most Sakya monasteries are located between 3000 and 5000 m in elevation, with almost none above 5000 m (Fig. 6a, b).

a, b Elevation. c, d Slope. e, f Aspect. g, h Dis2river. i, j Temperature. k, l Precipitation. The left column (a, c, e, g, i, k) illustrates the spatial distribution patterns of each natural factor across the study area, while the right column (b, d, f, h, j, l) presents the corresponding statistical relationship with the number of Sakya monasteries.

Slope is derived from DEM data. While elevation defines the macro-scale vertical distribution belt, slope determines the micro-topographical suitability for monastery construction within that framework. Results show a clear adaptive pattern of “preference for gentle slopes, avoidance of steep terrain,” with the majority of monasteries located on slopes ranging from 0 to 10° (Fig. 6c, d).

Aspect is also derived from DEM data. The statistics indicate that south-facing slopes host the highest number of monasteries, followed by southwest and west-facing slopes. This is primarily because south-facing slopes receive more solar radiation and precipitation48, and are symbolically associated with prosperity, auspiciousness, and sunlight in Tibetan geomancy (Fig. 6e, f).

Water availability, as one of the most critical resources for habitation and survival on the plateau, also plays a significant role in monastery site selection. We analyzed monastery counts across different distance intervals from water bodies, and results indicate a clear preference for proximity to water: monasteries are most densely distributed within 0–4 km of a water body (Fig. 6g, h).

Temperature (Fig. 6i, j) and precipitation (Fig. 6k, l) are further decisive variables for environmental suitability in high-altitude regions, closely tied to agricultural viability. Using climate data from the year 1901, we find that Sakya monasteries are primarily located in areas with mean annual temperatures between 0 and 5 °C and annual precipitation between 400 and 800 mm. These areas are mainly concentrated in eastern Kham and Amdo, as well as some valley regions in Ü-Tsang, such as the Nyangchu River and Lhasa River basins. These valleys boast over 3500 years of agricultural settlement history49.

Turning to human factors, this study selected population distribution, village and town density, distance to the Ancient Tea Horse Road, and the kernel density of Gelug, Kagyu, Nyingma, and Bon monasteries. Historical population density often closely correlates with the distribution of monasteries. Using population data from the year 1820, the analysis shows that the majority of Sakya monasteries are located in areas with low population density (0–200 people/km²). Such sparsely populated regions not only provide basic labor but also help maintain the environmental seclusion required for religious practice. A considerable number of monasteries are also found in areas with medium population density, whereas in the more densely populated eastern Amdo region, Sakya monasteries are relatively scarce (Fig. 7a, b).

a, b Population. c, d Village density. e, f The Ancient Tea Horse Road. Panels g–j display bivariate kernel density maps comparing the spatial distribution of the Sakya school with other sects. The kernel density of each sect is categorized into high, medium, and low levels, where blue represents the Sakya school and orange represents the corresponding other sect. g Sakya and Gelug. h Sakya and Kagyu. i Sakya and Nyingma. j Sakya and Bon.

The second factor is historical village density, also based on 1820 data. Results show that Sakya monasteries are mainly concentrated in density levels 2–6, presenting a pattern of “more in the middle, fewer at both ends” (Fig. 7c, d). The Ancient Tea Horse Road was a historical trade route in southwestern China focused on tea and horse trade. This study statistically analyzed the number of monasteries at different distances from the route. Nearly half of the monasteries are located within 0–20 km from the road, and the number of monasteries gradually decreases with increasing distance. This hierarchical distribution centered on the route axis reflects the Sakya monasteries’ reliance on convenient transportation conditions (Fig. 7e, f).

The remaining four factors are the kernel density distributions of the other four sects. This study uses binary color maps to compare the differences in density between Sakya and each of the other sects. Regarding the Sakya and Gelug sects (Fig. 7g), the core area of Gelug monastery distribution is mainly in the Amdo region. There is no overlap between the high-density clusters of Gelug and Sakya monasteries, though there are several medium-density overlaps in the Ü-Tsang region. The Kagyu sect (Fig. 7h) shares the most similar distribution pattern with the Sakya sect; both are primarily located in the Kham and Ü-Tsang regions and are nearly absent in Amdo. In eastern Kham, there are numerous high-high and medium-medium clusters. The Nyingma sect (Fig. 7i), the oldest school of Tibetan Buddhism, is widely and evenly distributed across the Tibetan regions, largely because of its family-based monastic tradition, which results in more dispersed sites. The Bon religion (Fig. 7j) is more commonly found in the Amdo and Kham regions and is relatively scarce in Ü-Tsang. This is because, after Buddhism was introduced to Tibet, the indigenous Bon tradition gradually retreated from the core Buddhist areas of Ü-Tsang.

In the following analysis, we selected the following variables as predictors: elevation (X1), slope (X2), aspect (X3), distance to water bodies (X4), historical annual mean temperature (X5), historical annual precipitation (X6), historical population density (X7), historical settlement density (X8), distance to the Tea-Horse Road (X9), kernel density of Gelug monasteries (X10), Kagyu monasteries (X11), Nyingma monasteries (X12), and Bon monasteries (X13). The kernel density of Sakya monasteries was treated as the dependent variable. It should be emphasized that this study focuses on exploring the correlations between these natural and cultural variables and the spatial distribution of Sakya monasteries, rather than inferring strict causal relationships.

Before applying machine learning models to perform regression analysis on these variables, we first conducted a Pearson correlation analysis to preliminarily examine the relationships between variables. As shown in Fig. 8, most factors exhibit relatively low degrees of correlation. A strong negative correlation is observed between historical annual mean temperature (X5) and elevation (X1) (r = −0.85), which aligns with the natural trend of decreasing temperature with increasing altitude. A relatively high positive correlation is found between distance to water bodies (X4) and distance to the Tea-Horse Road (X9) (r = 0.60), indicating that ancient roads often followed river courses. Regarding the relationship between the kernel densities of the four major religious schools and settlement density, the Gelug school (X10) shows the highest correlation (r = 0.65), reflecting its strong social influence. This is followed by the Bon religion (X13, r = 0.54) and the Nyingma school (X12, r = 0.42). The Kagyu school (X11) shows the lowest correlation (r = 0.19), likely because Kagyu monasteries tend to be located in more secluded, tranquil environments, often in remote mountainous areas with minimal human activity.

To further examine the mechanisms through which different factors relate to the spatial distribution of Sakya monasteries, we employed the LightGBM model for regression analysis. The resulting R² values for the training and test sets are 0.977 and 0.974, respectively, demonstrating that the model has strong explanatory capacity. The RMSE for both sets is 0.00004, and the MAE is 0.00002, underscoring the model’s high precision and stability. In addition, we tested the spatial autocorrelation of residuals using Moran’s I. The result (Moran’s I = 0.808, p < 0.001) indicates the presence of spatial clustering. However, given the very small magnitude of residuals, this clustering does not undermine the model’s reliability; rather, it suggests that while the dominant natural and human factors have been effectively captured, certain historical, political, or cultural dynamics not represented in the dataset may contribute to the remaining spatial dependence.

To analyze the multicollinearity of the influencing factors within the model, we applied the SHAP tool to interpret the results. As shown in Fig. 9, we plotted the SHAP summary plot and a bar chart ranking the importance of each feature. The importance scores were derived from the mean absolute SHAP values of each feature. Additionally, we annotated the SHAP bar chart with the Pearson correlation coefficients between each feature and the dependent variable for reference. This dual-dimensional interpretation not only provides a clear visualization of each feature’s contribution to the model but also reflects the strength of its linear relationship with the target variable.

The left side of the figure shows the SHAP summary plot, and the right side presents the feature importance ranking chart. The r values annotated on the bar chart represent the Pearson correlation coefficients between each feature variable and the dependent variable, while the percentages indicate each feature’s relative contribution to the overall model explanation.

The results shown in the figure indicate that the Kagyu sect temple density (X11) has the highest contribution in the model, accounting for 29.7%. Its correlation coefficient with the dependent variable is r = 0.51, which also demonstrates a strong correlation. This high similarity mainly stems from deep connections in their historical diffusion routes, politico-religious interaction patterns, and sectarian competition. Regarding historical diffusion, both originated in the Ü-Tsang region and expanded along similar routes into the Kham region during their early spread, while diffusion into the Amdo region was later or restricted due to geographic and political factors. In terms of politico-religious relations, the Sakya sect received imperial support during the Yuan Dynasty but was later replaced by the Phagmodrupa Kagyu regime. Similar political backgrounds made it easier for both sects to establish temples in the political centers of Ü-Tsang. Concerning sectarian relations, the Gelug sect later dominated the Amdo region, squeezing the development space of both Sakya and Kagyu sects.

From the feature importance ranking bar chart, the top six features are all human factor variables, including the kernel density distribution of the four major sects’ temples, as well as historical town density and population density. This indicates that the distribution of Sakya temples is more influenced by human factors than natural factors. It can also be observed that the order of correlation differs from that of feature importance. For example, Gelug temple density ranks second in overall feature importance, accounting for 20.2%, but its correlation coefficient is relatively low at r = 0.26. This suggests that this factor may influence Sakya temple distribution more through nonlinear interaction effects rather than a simple linear relationship.

Natural factors (X1-X6) contribute relatively little to the model. Slope (X2) and aspect (X3) account for only 0.2% and 0.1%, respectively. The contributions then increase in order: distance to water (X4, r = −0.19, 1.2%), annual average temperature (X5, r = 0.15, 1.2%), annual average precipitation (X6, r = 0.22, 5.1%), and elevation (X1, r = −0.01, 5.8%). The negative correlation coefficients for distance to water (X4) and elevation (X1) align with the pattern that temples tend to be distributed at lower elevations and closer to water sources.

We also examined SHAP interaction values to assess potential joint effects between variables (Fig. 10). The analysis reveals that overall interaction values are very small, suggesting that cross-factor effects contribute little beyond the individual influence of each variable. Relatively higher values are observed for the pairs of Gelug monastery density with mean annual precipitation, Gelug and Kagyu monastery densities, and Nyingma monastery density with historical population. However, their magnitudes remain negligible in comparison to single-variable effects. These findings indicate that while limited interactions can be detected, they play only a secondary role in shaping the spatial distribution of Sakya monasteries, with the model’s explanatory power primarily driven by individual factors.

For further local-scale analysis, the SHAP values of each feature were visualized spatially on the map, as shown in Fig. 11. The results show that the spatial distribution of SHAP values for natural variables does not exhibit pronounced patterns, whereas the overall spatial explanatory power of human-related variables is notably higher. This may be because, within the large-scale spatial context of the Tibetan Plateau, micro-topographic variables such as slope and aspect vary relatively little within suitable elevational zones, meaning their influence on monastery site selection is more evident at the local scale and less distinguishable at the macro-regional level.

Specifically, the SHAP values for Kagyu monastery density display a pronounced high-value cluster in the southeastern part of the Kham region, indicating a marked spatial association between the distributions of Kagyu and Sakya monasteries in this area. This positive association may be related to the fact that, since the Yuan dynasty, the two sects expanded along similar transport corridors and river valleys, leading to spatial co-occurrence in parts of Kham. In contrast, in the Amdo region (the northeastern fringe of the study area), the SHAP values are negative, suggesting a contrasting distribution pattern between the two sects. This pattern may be linked to the rise of the Gelug sect in Amdo during the Ming and Qing dynasties, which reduced the spatial presence of both Sakya and Kagyu monasteries.

For the other three sects, the SHAP values for monastery density mostly fall in the medium range. Among them, the Gelug sect shows the widest distribution of medium values, reflecting its extensive influence in later periods; the Bon religion exhibits fewer medium-value areas and a distinct low-value zone in the southern Kham region. This is largely attributable to the contraction of Bon’s sphere of influence following the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet, leaving Bon mainly in peripheral areas such as eastern Amdo. In addition, the variables representing population distribution and settlement density also show medium-to-high value clusters in the southeastern part of the study area, corresponding to the region’s long-standing transportation accessibility and socio-economic vitality. In contrast, the SHAP values for distance to the Tea Horse Road are generally low, possibly indicating that during the spread of the Sakya sect, the role of this transportation route was overshadowed by interactions among sects and local socio-cultural conditions.

Overall, these results reveal varying degrees of spatial association between different natural and human factors and the distribution of Sakya monasteries, reflecting the combined effects and regional differences that shape macro-scale spatial patterns.

Discussion

This study employs multi-scale spatial statistics, GIS techniques, and machine learning combined with SHAP interpretability to systematically elucidate the spatial distribution patterns and driving mechanisms of Sakya sect monasteries in Tibetan Buddhism. Overall, the Sakya monasteries exhibit a distribution pattern characterized by dense clusters in the east and sparse occurrences in the west, alongside concentrated aggregation in the south and dispersion in the north. This spatial configuration not only reflects fundamental constraints imposed by natural factors—such as elevation, slope, aspect, and hydrological features—but also deeply embodies the complex interplay of historical religious-political dynamics, economic trade routes, and socio-cultural influences. Based on our findings, the ensuing discussion focuses on three key aspects:

First, we compare the spatial distribution patterns and driving factors of Sakya monasteries with those of Gelug monasteries as examined by Chao et al.6. At the scale of the entire Tibetan region, Sakya monasteries are most densely concentrated in the Kham area, whereas Gelug monasteries exhibit their highest density in Lhasa and the Shannan region, reflecting the Gelug sect’s dominant influence and prominence. At the level of the three major Tibetan regions, Sakya monasteries in Ü-Tsang display a tri-centric pattern centered primarily around Shigatse, while Gelug monasteries manifest a dual-core distribution, with the densest core around Lhasa and Shannan, and a secondary, lower-density core east of Shigatse. In Kham, Sakya monasteries form a distinct core-and-belt density pattern, contrasting with the Gelug sect, which lacks a significant high-density cluster there. In Amdo, Sakya monasteries are sparse, whereas Gelug monasteries are widely distributed in the eastern part with a concentrated “one core, two nuclei” pattern, hosting the largest number of monasteries in that region. This dominance in Amdo by the Gelug sect has constrained the spatial expansion of Sakya monasteries.

Regarding factors influencing monastery distribution, previous research on Gelug monasteries has been primarily qualitative, lacking quantitative analysis. Natural factors similarly influence the distributions of both sects, but notable differences arise in human factors. The two sects originated in distinct locales: Gelug with Lhasa (centered on Ganden Monastery), and Sakya in Saga County of Shigatse (marked by Sakya Monastery). Politically, Gelug expanded through the integration of Kagyu monasteries and Mongol alliances, often enforcing conversion of other sects’ temples, while Sakya’s development was closely tied to the theocratic governance model under the Yuan dynasty. Population correlation also diverges: Gelug monastery numbers strongly correlate with population density (e.g., dense populations and monasteries in Amdo), whereas Sakya monasteries, primarily located in moderately populated Kham, show weaker association with population distribution due to Gelug dominance in populous regions.

Beyond spatial patterns and demographic correlations, the observed differences between the two sects may reflect their distinct positions within the politico-religious system. While our analysis does not explicitly differentiate temporal stages, historical records suggest that the Sakya sect’s development was more closely tied to localized centers of influence, whereas the Gelug sect gradually expanded its presence through sustained political-religious alliances, particularly with Mongol and later Qing support. These different institutional linkages may have shaped site selection preferences—concentration around traditional strongholds for Sakya, and wider expansion associated with population corridors for Gelug. While this study focuses on overall distributional characteristics, future research will explicitly incorporate temporal phases and political-economic dynamics to further test these mechanisms.

Second, our machine learning analysis reveals that human factors exert a substantially greater influence on the spatial distribution of Sakya monasteries than natural factors. Although natural variables such as elevation, slope, aspect, and climate impose certain constraints on site selection, their marginal effects are generally weak. In contrast, anthropogenic factors—including historical population, village and town density, transportation networks, and the spatial presence of other sects’ monasteries—dominate linear correlations and further amplify their impact on religious spatial patterns through nonlinear interaction effects. Notably, the interplay among different sects reflects the complex dynamics of political, economic, and cultural forces shaping religious diffusion. This indicates that the formation and evolution of Sakya monasteries rely more heavily on the historical allocation of social resources, societal interactions, and politico-religious negotiations than on passive adaptation to natural environments.

However, these conclusions arise from macro-scale modeling and analysis aimed at elucidating broad regional patterns and spatial heterogeneity across the Tibetan inhabited areas. When the scale shifts to the micro level—such as the siting and construction processes of individual monasteries or localized clusters—natural factors may assume a more prominent role. In practical terms, considerations like terrain flatness, water accessibility, sunlight exposure, and climatic suitability are often critical site-selection criteria that directly affect the feasibility and sustainability of monastery establishment. Thus, the intensity and primacy of influencing factors exhibit clear scale dependence. Future research should integrate macro-regional pattern analysis with micro-level case studies, employing multi-scale nested approaches to more comprehensively unravel the complex drivers of Tibetan Buddhist monastery spatial organization, achieving a progressive understanding from overall trends to localized specifics.

Finally, despite the robustness of the methods applied, this study is subject to several data-related limitations that merit attention. First, the classification of monasteries by sectarian affiliation relies on historical records that may contain uncertainties or inconsistencies, especially in cases of sectarian conversion or contested attribution. Second, the precise geographic coordinates of monasteries are sometimes uncertain. While some coordinates are based on modern survey data, others are reconstructed from historical maps or textual descriptions, leading to varying degrees of uncertainty that could influence spatial density or clustering outcomes. These limitations may influence the precision of spatial statistical results and the interpretation of sectarian distribution patterns. Nevertheless, there are inherent challenges in historical GIS research, where sources are often fragmentary. To mitigate their impact, we relied on cross-referencing multiple historical sources and validated location data wherever possible.

In conclusion, this study combines GIS-based spatial analysis, interpretable machine learning (LightGBM), and SHAP explainability to examine the spatial patterns of Sakya monasteries and how the distribution relates to both natural and human factors. The main findings are as follows:

-

(a)

Sakya monasteries show strong spatial clustering, with high-density areas concentrated in the river valleys of Kham and the Shigatse-Shannan corridor. They are generally located in mid-elevation, gently sloping, and sun-facing valleys with moderate climate, as well as in areas with accessible settlements and transportation.

-

(b)

Human factors, especially the densities of Kagyu and Gelug monasteries, and historical population, are the strongest correlates, underscoring the predominant role of human dynamics relative to natural conditions.

-

(c)

Local SHAP analysis reveals clear spatial heterogeneity in factor contributions. Human factors dominate, with Kagyu density positively correlated with Sakya monasteries in Kham but negatively in Amdo, while other sects and socio-economic variables show moderate effects. These patterns highlight regional differences and complex inter-sect relations.

While these findings provide new insights, the study is primarily framed within a macro-spatial perspective—focusing on overarching distributional patterns and their influencing factors—and therefore does not incorporate temporal dimensions such as monastery founding dates or subsequent transformations. In addition, political regimes and institutional variables related to religious governance are not yet included, which further limits the explanatory depth of the model. Future research should incorporate temporal dynamics, political contexts, and institutional characteristics in order to capture the historical processes underlying monastery establishment and sectarian interactions more fully. Beyond the Sakya case, the methodological framework proposed in this study is adaptable to other religious traditions and forms of cultural heritage, offering both academic value and practical implications for heritage management and preservation planning.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Yu, K. The World’s Three Major Religions and Their Sects (Hunan People’s Publishing House, 1988).

Harvey, P. An Introduction To Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Zürcher, E. The Buddhist Conquest Of China: The Spread and Adaptation of Buddhism In Early Medieval China (Brill, 2007).

Wang, K. D. On the influence of geographical environment on Tibetan Buddhism. J. Guangzhou Inst. Socialism 8, 58–62 (2010).

Duojie, Cairang Historical overview, doctrinal characteristics, and far-reaching influence of the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism. Qinghai Social Sciences 5, 34–41 (2018).

Chao, Z., Zhao, Y. & Liu, G. Multi-scale spatial patterns of Gelugpa monasteries of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibetan inhabited regions, China. GeoJournal 87, 4289–4310 (2022).

Chao, Z., Zhao, Y., Fang, S. & Chen, D. Spatial diffusion processes of Gelugpa monasteries of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibetan areas of China utilizing the multi-level diffusion model. Geo Spatial Inform. Sci. 27, 64–81 (2022).

Xiaoting, W., Yang, L., Jiangxin, Z. & Jorden, L. Z. T. The game between shamanism and Sakya school: the cultural identity significance of “liangzhou alliance” to Han, Tibetan and Mongolian nationalities. J. Sociol. Ethnol. 3, 17–23 (2021).

Lamo, S. Sakya tradition in Tibet & Ladakh region. Tibet J. 44, 19–26 (2019).

Rinpoche, D. The Sakya School of Tibetan Buddhism (Simon and Schuster, 2016).

Wang, L. The spread of the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism in the Amdo region from the perspective of spatiotemporal distribution of monasteries. J. North Minzu University 4, 131–136 (2013).

Wang, K. D. A preliminary study on the spatial distribution and characteristics of Sakya monasteries in the Kham region during historical periods. Religious Studies 4, 178–183 (2011).

Dean, K. Historical GIS (Geographical Information Systems) and the Geography of Religion. Handbook of the Geographies of Religion, 1213-1231 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024).

Fang, S., Zhao, Y., Chao, Z. & Kang, X. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in Amdo Tibetan Inhabited Regions, China. J. Geovis. Spat. Anal. 6, 29 (2022).

Fang, S. B., Zhao, Y. L., Liu, X. X. & Yang, Y. Quantitative characteristics and influencing factors of Tibetan Buddhist religious space with monasteries as the carrier: a case study of U-Tsang. China. Herit. Sci. 12, 23 (2024).

Chen, D., Zhao, Y., Chao, Z., Li, Y. & Fang, S. Constructing a digital system of historical geographic information from the perspective of digital humanities: a case study of the historical geographic information database of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. Digit. Scholarship Humanit. 39, 43–60 (2024).

Alrasheedi, K. G., Lue, G. J., Baby, S. N. & Al-Ansari, N. GIS-based spatial accessibility to Islamic facilities for muslim community in the Melbourne metropolitan area. Earth Sci. Geotech. Eng. 10, 49–68 (2020).

Afnarius, S., Akbar, F. & Yuliani, F. Developing web-based and mobile-based GIS for places of worship information to support halal tourism: a case study in Bukittinggi, Indonesia. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 9, 52 (2020).

Cofrancesco, P., Capolupo, C. & Frisetti, A. Mapping medieval Christianity. CARE-GIS: reusing web digital data in a webGIS application. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 12, 1–12 (2019).

Vargha, M. Modelling Christianisation: A Geospatial Analysis of the Archaeological Data on the Rural Church Network of Hungary in the 11th-12th Centuries (Archaeopress Publishing, 2022).

Saha, K., Kalra, R. & Khare, R. A geospatial approach to enhance religious tourism in India—A case of Ujjain city, Madhya Pradesh. GeoJournal 87, 1793–1810 (2022).

Piarsa, N. & Adi Purnawan, K. Design and implementation of web-based geographic information systems on mapping hindu’s temple. Appl. Mech. Mater. 776, 437–442 (2015).

He, W., Shirowzhan, S. & Pettit, C. J. GIS and machine learning for analysing influencing factors of bushfires using 40-year spatio-temporal bushfire data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 11, 336 (2022).

Huang, D., Su, L., Fan, H., Zhou, L. & Tian, Y. Identification of topographic factors for gully erosion susceptibility and their spatial modelling using machine learning in the black soil region of Northeast China. Ecol. Indic. 143, 109376 (2022).

Avand, M. & Moradi, H. Using machine learning models, remote sensing, and GIS to investigate the effects of changing climates and land uses on flood probability. J. Hydrol. 595, 125663 (2021).

Linardatos, P., Papastefanopoulos, V. & Kotsiantis, S. Explainable AI: a review of machine learning interpretability methods. Entropy 23, 18 (2020).

Du, M., Liu, N. & Hu, X. Techniques for interpretable machine learning. Commun. ACM 63, 68–77 (2019).

Li, Z. Extracting spatial effects from machine learning model using local interpretation method: An example of SHAP and XGBoost. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 96, 101845 (2022).

Ke, E., Zhao, J. & Zhao, Y. Investigating the influence of nonlinear spatial heterogeneity in urban flooding factors using geographic explainable artificial intelligence. J. Hydrol. 648, 132398 (2025).

Zhang, J. et al. Insights into geospatial heterogeneity of landslide susceptibility based on the SHAP-XGBoost model. J. Environ. Manag. 332, 117357 (2023).

Peng, S. 1-km onthly Mean Temperature Dataset for China (1901-2022). (National Tibetan Plateau Data Center, 2019).

Peng, S. 1-km Monthly Precipitation Dataset For China (1901-2020) (National Tibetan Plateau Data Center, 2020).

Silverman, B. W. Density Estimation For Statistics And Data Analysis (Routledge, 2018).

Ebdon, D. Statistics in Geography (Blackwell, 1985).

Getis, A. Interaction modeling using second-order analysis. Environ. Plan. A 16, 173–183 (1984).

Ke, G. et al. Lightgbm: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 30, 3146–3154 (2017).

Wang, D.-n, Li, L. & Zhao, D. Corporate finance risk prediction based on LightGBM. Inf. Sci. 602, 259–268 (2022).

Qiu, Y. & Zhang, H. Prediction of Software User Interaction Data Based on the LightGBM Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Big Data and Internet of Things 226-230 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2024).

Pan, H. et al. The LightGBM-based classification algorithm for Chinese characters speech imagery BCI system. Cogn. Neurodyn. 17, 373–384 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Interpretation of spatial and temporal changes and drivers of ecological source regions based on LightGBM-SHAP. AIP Adv 14, 065036 (2024).

Lundberg, S. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 30, 4768–4777 (2017).

Shapley, L. S. A value for n-person games. Contribution to the Theory of Games 307-317 (Princeton University Press, 1953).

Van den Broeck, G., Lykov, A., Schleich, M. & Suciu, D. On the tractability of SHAP explanations. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 74, 851–886 (2022).

Moreno, M. A. Derge: the heaven of the Tibetan book. PORTO ARTE: Revista de Artes Visuais 23, 137–141 (2018).

Gesang. The ancient Sakya monastery: the second Dunhuang. China Cult. Heritage 46, 40–45 (2009).

Davidson, R. M. Tibetan Renaissance: Tantric Buddhism in the Rebirth of Tibetan Culture (Columbia University Press, 2005).

Li, X., Gao, J. & Zhang, J. A topographic perspective on the distribution of degraded meadows and their changes on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, West China. Land Degrad. Dev. 29, 1574–1582 (2018).

Yao, T. et al. A review of climatic controls on δ18O in precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau: observations and simulations. Rev. Geophys. 51, 525–548 (2013).

Gamble, R., Powers, J. & Hackett, P. Central Tibetan famines 1280-1400: when premodern climate change and bad governance starved Tibet. Bull. Sch. Orient. Afr. Stud. 85, 215–233 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China (No. 23BTQ049).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L.: Conceptualization, methodology design, data analysis, visualization, writing-original and revised manuscript. Y.Z.: Conceptualization, methodology design, Funding acquisition, writing-review and editing. S.F.: Data curation, Resources, Supervision, writing-review and editing. E.G.: Interpretation of historical sources, writing-review and editing. Y.Y.: Supervision, methodology design, writing-review and editing. All authors reviewed the final manuscript and approved its submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Zhao, Y., Fang, S. et al. Unveiling the factors influencing Sakya monastery distribution via interpretable machine learning. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 526 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02086-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02086-y