Abstract

This study presents a multimodal approach integrating infrared thermography with 3D laser scanning for the thermal characterization of bronze antiquities with non-uniform thickness. Traditional methods often conflate material properties and geometric effects, which can lead to inaccurate estimation of thermal diffusivity. To overcome this, a framework was developed to align 3D geometric data with transient thermal responses. Experiments on bronze mirrors demonstrate that the proposed method effectively compensates for thickness gradients, revealing intrinsic material heterogeneity, including localized thermal anomalies linked to tin segregation. COMSOL-based simulations validate the applicability of the 1D heat transfer model in regions with mild thickness variation. By separating geometric and material effects, the methodology enhances defect detection and provides quantitative guidance for conservation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infrared thermography (IRT) is a non-contact, non-destructive testing (NDT) technique that detects surface and subsurface inhomogeneities based on thermal response analysis1,2. It operates either passively, by observing naturally occurring temperature variations, or actively, by applying external thermal excitation, commonly through flash lamps, halogen lamps, or lasers. Active IRT can be further categorized into pulsed thermography (PT), lock-in thermography (LIT), and step-heating thermography (ST). It can be performed in either reflection or transmission geometry, depending on the relative positions of the heat source and the infrared detector.

Over the past two decades, IRT has gained traction in the characterization and conservation of cultural heritage objects, with successful applications ranging from historical buildings, paintings and frescos to metal artifacts, particularly bronze objects3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Pulsed thermography is especially effective for bronzes due to their high thermal diffusivity and conductivity, and has been widely used in the analysis of Western bronze statues under reflection-mode configurations13,14,15,16,17. To accommodate more complex material interfaces and corrosion layers, recent studies have proposed double- and multi-layer thermal diffusion models18,19,20.

There are two principal categories of IRT applications: qualitative imaging to locate defects, and quantitative analysis for extracting thermal parameters such as diffusivity or defect depth21,22. However, thermal responses are jointly influenced by geometry and intrinsic thermal properties, making quantitative interpretation nontrivial. Most existing applications, assume uniform, flat geometries—common in industrial settings such as aerospace composites or metal plates—where either thickness or thermal properties are predefined23,24,25,26.

Cultural heritage artifacts, in contrast, exhibit complex, irregular geometries and heterogeneous material compositions. Bronze artifacts, for example, may have variable thicknesses from casting, internal inclusions, and layered corrosion products, with alloy compositions varying across regions. These factors complicate the interpretation of thermal diffusion and reduce the applicability of standard inversion models. As a result, IRT analysis in heritage contexts faces ongoing challenges in decoupling geometric effects from intrinsic material properties.

Understanding the spatial distribution of thermal properties in cultural heritage artifacts is essential for their effective conservation. It enables a better evaluation of how objects respond to environmental changes, supporting structural stability assessments and the identification of potential deterioration risks. Deviations in thermal behavior can also reveal hidden defects such as voids, inclusions, or corrosion, allowing for early-stage, non-destructive diagnostics. Furthermore, accurate thermal data informs the selection of restoration materials that are thermally compatible with the original, helping to prevent stress-induced damage. In addition, these parameters provide a basis for constructing thermal response models and digital monitoring systems, contributing to more scientific and sustainable preventive conservation strategies.

Recent technological advances, such as 3D scanning and low-cost thermal imaging, have introduced new opportunities. High-resolution geometry enables digital modeling and wall thickness estimation, while smartphone-based thermal detection expands accessibility27,28,29,30. Some studies integrate infrared images with point clouds or visible-light data for 3D thermal mapping of heritage buildings31,32. Yet, most of these approaches remain focused on visualization or architectural chronology, and lack the ability to simulate physically meaningful thermal processes33, underscoring the need for more advanced modeling strategies and adaptive image processing techniques.

A multimodal framework that integrates PT with 3D laser scanning is proposed in this study. A thickness-compensated inversion method for estimating thermal diffusivity is developed by aligning transient thermal data with detailed geometric information.This approach enhances defect detection accuracy and provides a robust solution for characterizing the thermal behavior of complex heritage materials.

Methods

Bronze mirrors are invaluable cultural artifacts that encapsulate ancient metallurgical techniques and symbolic meanings. Due to their age and fabrication processes, they are prone to internal defects such as shrinkage cavities, cracks, and layered corrosion, all of which can significantly alter their thermal behavior and compromise their structural stability under environmental stress34,35. Accurate characterization of their thermal properties is thus essential—not only for assessing internal stress and predicting deterioration pathways, but also for informing evidence-based preventive conservation strategies36.

However, conventional thermal analysis techniques, such as steady-state or transient plane source methods, generally assume simple, homogeneous geometries. These assumptions do not hold for bronze mirrors, which often feature complex curvature, relief decorations, and uneven wall thicknesses. Such geometric irregularities complicate heat diffusion modeling and can obscure or distort the interpretation of subsurface features37. To overcome these challenges, this study employs a multimodal approach that integrates pulsed infrared thermography with 3D geometric data to improve the reliability of thermal parameter extraction.

Study object: Tang Dynasty bronze mirror

The object investigated in this study is a bronze mirror from the Tang Dynasty, illustrated in Fig. 1, measuring ~136.4 mm by 135.2 mm. It features a petal-shaped edge and a slightly convex reflective surface, designed to create a soft magnification effect. The reverse side is elaborately decorated, with ten rams adorning the outer ring and the Eight Trigrams (Bagua) symmetrically arranged around a central Yin-Yang symbol in the inner circle. At the center of the mirror is a raised knob with a perforation, likely for suspension.

A casting defect occurred during the manufacturing process, caused by insufficient separation of the mold during metal pouring, resulting in a hole on the mirror surface. This defect may cause localized variations in thickness and material distribution, leading to slight misalignment of decorative patterns and secondary effects such as microporosity due to interrupted metal flow.

Thermal diffusivity measurement using transmission-mode pulsed IRT

Transmission pulsed thermography is a non-contact, nondestructive testing technique that evaluates thermal properties and detects internal defects by applying a short thermal pulse, typically generated by a flash lamp, to one side of the specimen while recording the temperature evolution on the opposite side using an infrared camera. In homogeneous, defect-free materials, heat diffuses evenly, resulting in smooth temperature changes on the rear surface. Internal defects such as voids, inclusions, or corrosion layers disrupt heat flow, causing localized thermal anomalies that appear as contrasts in thermal images. By analyzing these contrasts, defects’ presence, location, and characteristics can be identified.

Under adiabatic conditions, when a homogeneous material of thickness \({\rm{d}}\) absorbs a surface heat pulse with energy \({\rm{q}}\) per unit area, the rear surface temperature evolution \({\rm{T}}({\rm{d}},{\rm{t}})\) can be described by:

where \({\rm{C}}\) and \({\rm{\rho }}\) represent the material’s specific heat capacity and density, respectively. Thermal diffusivity (\({\rm{\alpha }}\)), a key parameter characterizing heat transfer, can be extracted from the temperature-time curve by iteratively adjusting the fitting parameters through nonlinear curve fitting to achieve the best match with the experimental thermal response data, given the known sample thickness38.

The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 2. A high-power flash lamp provided 2 ms pulses with a maximum energy of 2.4 kJ. A FLIR SC7000 cooled infrared camera (7.7–9.3 \({\rm{\mu }}{\rm{m}}\) spectral range, 320 × 256 resolution) was used to capture thermal data. During testing, the bronze mirror was positioned to fill the camera’s field of view, with the flash aligned to ensure uniform heating. Thermal images were recorded at 200 Hz for 3 s under stable ambient conditions.

3D laser scanning experiment

The surface geometry of the bronze mirror was captured using the HandySCAN 700 laser 3D scanner (Creaform), which employs 7 blue laser lines for data acquisition. The system offers a resolution of 0.2 mm and an accuracy of up to 0.03 mm, making it well-suited for complex and curved surfaces such as those of the bronze mirror.

Before scanning, the device was carefully calibrated, and the mirror was positioned to ensure optimal coverage. Reference targets were placed on and around the specimen to improve spatial alignment and facilitate full-surface reconstruction. Due to the mirror’s thin and irregular edges, the front and back sides were scanned separately. The resulting datasets were then aligned and merged using post-processing software, yielding a high-resolution mesh with alignment accuracy typically within the millimeter range.

Transient 3D heat conduction simulation

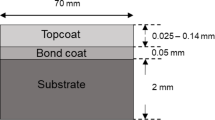

Although thermal diffusivity was estimated using a 1D model, surface curvature and irregularities may induce 3D heat flow, potentially affecting accuracy. To evaluate the validity of the 1D approximation, transient heat conduction simulations were conducted in COMSOL Multiphysics using two models: (a) a self-designed sample incorporating flat, protruding, and sloped surfaces with dimensions marked on the figure, and (b) a high-resolution 3D mesh of the actual bronze mirror obtained via laser scanning (Fig. 3a, b). Both models treated the sample as a homogeneous solid.

In both cases, a 2 ms, 2.4 kJ heat pulse was applied to the smooth bottom side, and temperature evolution on the opposite side was simulated over with a 0.005 s time step, matching the 200 Hz frame rate of the IR camera. Representative regions with the same thickness (2.5 mm for both self-designed and the bronze mirror model) were selected for analysis. To ensure accurate results, the mesh was set to an extremely fine mode, and all surfaces were set as thermally insulated. This setup allowed investigation into how local geometry influences transient heat flow and the applicability of the 1D assumption.

Results

This section combines transmission-mode PT, infrared image processing, and 3D laser scanning to analyze the thermal and geometric characteristics of the bronze mirror. First, subtle casting defect features were revealed through image processing. Subsequently, infrared data were registered to the reconstructed thickness map and used in thermal diffusivity inversion. Fitting lengths were adjusted based on local thickness. The fusion of 2D thermal data with 3D geometry enabled intuitive visualization of thermal property distributions. Comparative simulations further validated the applicability of the 1D heat conduction model in areas with gradual geometric variation, supporting the decoupling of thermal and structural parameters under specific conditions.

Transmission-mode pulsed thermography

In the transmission-mode experiment, a thermal pulse applied to the front surface via flash lamp initiated heat propagation through the sample. To investigate potential casting defects, infrared data were processed using first- and second-order Thermal Signal Reconstruction (TSR). As shown in Fig. 4a, this revealed a thermal barrier signature (blue circle) and multiple linear cracks (red circles). In contrast, reflection-mode IRT detected visible protrusions on the surface (yellow circles in Fig. 4b), demonstrating transmission-mode’s efficacy in identifying deeper flaws obscured in reflection-mode imaging.

A comparison of thermal responses between a thicker region (Region 1) and a thinner region (Region 2), shown on Fig. 5a, reveals that the thicker area exhibited slower heat transfer and a lower peak temperature, while the thinner region responded more rapidly and reached a higher saturation temperature. Normalized thermal curves are shown in Fig. 5b. However, due to their differing thicknesses, these responses cannot be directly used to compare intrinsic thermal properties.

As shown in Fig. 6a, a representative point with measured 2.41 mm thickness (double checked from the thickness map) was selected and input into the iterative fitting program to estimate thermal diffusivity. The fitting curve, as shown in Fig. 6b, demonstrates excellent agreement with the experimental data, indicating high accuracy. The final result shows that the thermal diffusivity is 6.02 mm²/s.

Point cloud data processing

Point cloud data of the bronze mirror surface was acquired using a laser 3D scanner and processed with specialized software for denoising, filtering, and surface reconstruction, shown in Fig. 7a. It was then exported as a VTP file to extract thickness information. A ray-tracing algorithm was employed to compute local thickness values across the surface. The VTP file was imported into ParaView, a data analysis and visualization software, where the model was scaled to its actual dimensions. The model was aligned with the infrared thermography data by adjusting the rotation center and coordinate axes to ensure consistency between geometric and thermal data, as shown in Fig. 7b. It was then segmented according to the resolution of the infrared image to generate a thickness map corresponding to each pixel. Figure 8 shows an example point with ID 18610, which corresponds to a thickness of 1.851 mm. The ID number was then converted to the x and y coordinates of the IR image.

Thermal diffusivity inversion and data fusion

A Python script was developed to automatically incorporate local thickness values into the iterative fitting process, introducing a thickness-dependent fitting duration to enhance accuracy. Selecting an appropriate fitting duration is crucial because the 1D analytical model assumes an adiabatic boundary conditions, leading to a flat temperature curve after saturation. However, in practical experiments, convective heat losses cause the temperature to gradually decline, which can distort the fitting if late-stage data are included. For example, as shown in Fig. 9, fitting a 0.5 mm thick point using 200 frames (1 s) introduces errors due to convective cooling. In thin regions, extended fitting durations can lead to significant deviations in thermal diffusivity estimation.

To address this, the optimal fitting length for minimizing errors at different thicknesses was determined. A functional relationship between the optimal fitting length and the square of thickness was established using the least squares method, as shown in Fig. 10. This relationship was incorporated into the script to allow dynamic assignment of fitting lengths during thermal diffusivity calculations. The resulting thermal diffusivity values were saved to an output file and visualized using scatter plots with color mapping, providing an intuitive representation of the spatial distribution of thermal properties, as shown in Fig. 11. Regions with lower thermal diffusivity correspond to the locations marked in Fig. 4a, while those shown in Fig. 4b exhibit no significant variation in Fig. 11. This suggests that the anomalies observed in Fig. 4b are likely due to thickness variations rather than material defects.

Subsequently, 2D thermal images were mapped onto the 3D bronze mirror model using Blender’s UV mapping technique. As shown in Fig. 12a, b, the pseudo-colored infrared thermogram (JET colormap) and the thermal diffusivity map (RGB scale) were accurately overlaid on the reconstructed surface. This 2D-on-3D fusion allows intuitive visualization of temperature gradients, defect locations, and material properties directly on the object’s geometry. When the model is viewed at an angle (e.g., 80°), features in the thermal image remain precisely aligned with their spatial counterparts, overcoming the limitations of flat thermal images and enhancing interpretation of thermophysical behavior in complex heritage artifacts.

Simulation validation of 3D heat flow effects

To further assess how 3D thermal effects influence the accuracy of thermal parameter estimation using a 1D analytical model, a simulation model was developed. As shown in Fig. 13a, three regions with identical thickness (2.5 mm) but different geometries (flat, protruding, and sloped) were selected. Using the same parameters as the transmission experiment, their thermal responses were simulated and compared, as illustrated in Fig. 13b. The results show that the protrusion area reaches the highest peak temperature, whereas the flat disc and sloped region show little differences in their temperature rise. This is due to heat spreads laterally and along curved surfaces within the structure, with greater curvature exhibiting stronger thermal flow aggregation and higher energy concentration. After normalization, the protrusion area shows faster temperature rise followed by the sloped and the flat area. This outcome confirms the phenomenon that the thermal diffusivity appears higher on the curved surfaces. It is worth noting that this simulations is conducted under specific conditions, where convective heat flux is omitted (heat transfer coefficient h = 0). This analysis contributes to a better understanding of the decoupling between thickness effects and material thermal properties.

Figure 14a presents two locations with sample thickness ~2.5 mm: a sloped point (experimental point 1) and a flat area (experimental point 2). Figure 14b shows the corresponding normalized simulated thermal responses, along with analytical results based on the 1D heat conduction model using averaged thermal parameters measured at these two locations. The simulation data closely align with the theoretical predictions, with a slightly faster temperature rise observed at the protrusion, consistent with simulation outcomes from the designed sample. These results suggest that the higher thermal diffusivity observed on non-flat surfaces may be partially influenced by 3D thermal effects.

Discussion

This study integrates 3D data to develop a locally thickness-compensated IRT model, which effectively decouples geometric effects from intrinsic thermal behavior in bronze mirrors with non-uniform thickness. By compensating for local thickness, the model enables more accurate extraction of thermal diffusivity. However, as a multi-element alloy, bronze often exhibits spatial heterogeneity in thermal properties due to compositional segregation, microstructural differences, and casting variability. These intrinsic factors, coupled with geometric complexity, introduce significant challenges in 3D heat transfer modeling and interpretation. Therefore, a comprehensive analysis must account for both 3D heat flow and material inhomogeneity.

The influence of alloy composition on thermal properties has been well documented. For instance, pure copper has a thermal diffusivity of ~116 mm²/s, while tin’s diffusivity is much lower, around 40 mm²/s. In copper-tin alloys, increasing tin content reduces both thermal conductivity and diffusivity. Previous IRT studies reported thermal diffusivity values of 4–8 mm²/s for bronze containing 10–20% tin39, and established an empirical correlation between thermal diffusivity and weighted concentration of tin and lead.

In this study, certain areas, especially near voids, exhibited noticeably higher thermal diffusivity than the average. These anomalies likely reflect local compositional or microstructural variations. One possible explanation is localized copper enrichment due to segregation during casting, which enhances heat conduction. Another factor could be the presence of microcracks or structural features that re-direct thermal flux, sometimes leading to elevated apparent diffusivity values, even though cracks are generally heat barriers. These interpretations demonstrate the importance of integrating material science understanding with thermal imaging analysis.

To reduce computational complexity, a 1D thermal diffusion model was adopted for parameter inversion. While this model performs reasonably well in regions with gentle thickness gradients, it becomes less reliable in areas with abrupt thickness changes or sharp curvature, where lateral heat flow cannot be ignored. Finite element simulations confirm that thermal diffusion is most rapid at protruding regions, and that 3D effects become significant in geometrically complex zones. This is particularly evident in the Eight Trigrams pattern. In such cases, more accurate 3D transient heat transfer models are needed to capture the true thermal behavior and improve defect detection.

Beyond the limitations of the 1D model, the methodology faced challenges in both data processing and interpretation. Data alignment relied on adjusting surface normals from the 3D scan to the camera’s line of sight, followed by manual registration using symmetry axes and edge features. Although validation against reference points indicated no significant misalignment, this manual procedure remains subjective and resolution-limited. On the interpretative side, IRT’s inherent ambiguity in separating thickness variations from material properties persists. While combining IRT with 3D scanning compensates for thickness, the accuracy of this approach is highly dependent on registration precision, and surface alterations such as corrosion layers or patina can further complicate material structure. Consequently, even when spatially resolved diffusivity maps are obtained, the origins of local anomalies arise from alloy segregation, voids, or microstructural damage remains difficult using thermal data alone. These challenges underscore the need for methodological refinements, including automation, and the integration of complementary analytical approaches.

Future work should aim to implement automated registration using feature-based recognition and gradient-based alignment, potentially supported by machine learning. Structured light projection or fiducial markers during data acquisition could further enhance spatial precision.

While the proposed method increases the diagnostic value of IRT by incorporating shape-related corrections, it does not eliminate the need for complementary analysis techniques and expert evaluation. It should therefore be viewed as part of a broader, integrated approach to the study and conservation of cultural heritage materials.

In practical conservation applications, the proposed 3D diffusivity mapping approach can identify zones of stress concentration, evaluate the integrity of historical metalwork, and even inform the assessment of restoration treatments. The technical framework developed here can be extended to other single-layer metallic artifacts, and has potential for adaptation to more complex objects. Further research should also explore the integration of environmental factors such as humidity into multiphysics thermal analysis, providing a broader basis for preventive conservation strategies.

In summary, this study proposes a novel, thickness-compensated IRT method that combines 3D scanning and thermal wave imaging to accurately extract thermal diffusivity in non-uniform bronze mirrors. By addressing both geometric and compositional complexity, the method improves the reliability of defect detection and material assessment. It offers a valuable tool for heritage science, with broader implications for the structural analysis and preventive conservation of metallic artifacts.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Liu, K., Wang, F., He, Y., Liu, Y. & Yang, J. Data-augmented manifold learning thermography for defect detection and evaluation of polymer composites. Polymers 15, 173 (2022).

Jiang, G. M., Wang, X., Hu, J. & Wang, Y. Simulation-aided infrared thermography with decomposition-based noise reduction for detecting defects in ancient polyptychs. Herit. Sci. 11, 223 (2023).

Mercuri, F. et al. Active infrared thermography applied to the investigation of art and historic artefacts. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 104, 475–485 (2011).

Grinzato, E., Bressan, C., Marinetti, S., Bison, P. & Bonacina, C. Monitoring of the Scrovegni Chapel by IR thermography: Giotto at infrared. Infrared Phys. Technol. 43, 165–169 (2002).

Brooke, C. Thermal imaging for the archaeological investigation of historic buildings. Remote Sens. 10, 1401 (2018).

Zhang, H. et al. Non-destructive investigation of paintings on canvas by continuous wave terahertz imaging and flash thermography. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 36, 34 (2017).

Bodnar, J. L. et al. Stimulated infrared thermography applied to help restoring mural paintings. NDTE Int. 49, 40–46 (2012).

Grinzato, E., Bison, P., Marinetti, S. & Vavilov, V. Nondestructive evaluation of delaminations in fresco plaster using transient infrared thermography. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 5, 257–274 (1996).

Avdelidis, N., Koui, M., Ibarra-Castanedo, C. & Maldague, X. Thermographic studies of plastered mosaics. Infrared Phys. Technol. 49, 254–256 (2007).

Theodorakeas, P., Avdelidis, N. P., Cheilakou, E. & Koui, M. Quantitative analysis of plastered mosaics by means of active infrared thermography. Constr. Build. Mater. 73, 417–425 (2014).

Yue, S. et al. Infrared thermography evaluation for Xuan Paper: safety validation and applications in Chinese painting conservation. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 372 (2025).

Wang, C. et al. Nondestructive detection of murals in tombs by square-heating thermography. Acta Opt. Sin. 41, 1611002 (2021).

Bottoni, M. & Fabretti, G. Model for the analysis of sun radiation structures exposed to open air: consideration of its validity and usefulness based on its experimentation in situ. Proc. SPIE 4360, 421051 (2001).

Orazi, N. et al. Thermographic analysis of bronze sculptures. Stud. Conserv. 61, 236–244 (2016).

Orazi, N. et al. Thermographic investigation of bronze artefacts: characterization of structure elements and casting faults in masterpieces of the bronze statuary of Rome. Int. J. Thermophys. 39, 141 (2018).

Mercuri, F., Paoloni, S., Orazi, N., Cicero, C. & Zammit, U. Pulsed infrared thermograph applied to quantitative characterization of the structure and the casting faults of the Capitoline She Wolf. Appl. Phys. A 123, 327 (2017).

Tao, N., Wang, C., Zhang, C. & Sun, J. G. Quantitative measurement of cast metal relics by pulsed thermal imaging. QIRT J. 19, 27–40 (2020).

Mercuri, F. et al. Depth-resolved analysis of double-layered cultural heritage artifacts by pulsed thermography. Int. J. Thermophys. 41, 6 (2020).

Yang, X., Chen, B., Hu, G. B. & Wang, X. Y. Pulsed infrared thermographic study of a Chinese Bronze Lei. Herit. Sci. 10, 73 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Revealing hidden flaws: Infrared thermography for detecting delamination in Chinese cloisonné enamels. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 92 (2025).

He, Y. et al. Research progress of laser thermography non-destructive testing (invited). Infrared Laser Eng. 53, 20240144 (2024).

Bison, P., Maldague, X., Sfarra, S. & Vavilov, V. Introduction to the QIRT journal special issue on: “2012–2022 in memory of Dr. Ermanno Grinzato: a landmark in Quantitative InfraRed Thermography”. Quant. Infrared Thermogr. J. 21, 335–337 (2024).

Yang, B., Huang, Y. & Cheng, L. Defect detection and evaluation of ultrasonic infrared thermography for aerospace CFRP composites. Infrared Phys. Technol. 60, 166–173 (2013).

Ali, Z., Addepalli, S. & Zhao, Y. Thermal material property evaluation using through transmission thermography: a systematic review. Appl. Sci. 14, 6791 (2024).

Ali, Z., Addepalli, S. & Zhao, Y. Effective thermal diffusivity measurement using through-transmission pulsed thermography: extending the current practice by incorporating multi-parameter optimisation. Sensors 25, 1139 (2025).

D’Accardi, E. et al. Evaluation of typical rail defects by induction thermography: experimental results and procedure for data analysis during high-speed laboratory testing. Quant. Infrared Thermogr. J. 22, 173–194 (2024).

Pawlak, S. Application of IR thermography with thermal diffusivity analysis for detection of plies displacement in CFRP composites. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 27, 6545–6551 (2018).

Diao, C. & Ning, B. 3D scanning and digital conservation efforts of the Yungang Grottoes Research Academy. ARS Orient. 50, 20220203 (2020).

Capolupo, A. Accuracy assessment of cultural heritage models extracting 3D point cloud geometric features with RPAS SfM-MVS and TLS techniques. Drones 5, 145 (2021).

Yang, M.-D., Su, T.-C. & Lin, H.-Y. Fusion of infrared thermal image and visible image for 3D thermal model reconstruction using smartphone sensors. Sensors 18, 2003 (2018).

Spodek, J. & Rosina, E. Application of infrared thermography to historic building investigation. J. Archit. Conserv. 15, 65–81 (2009).

Zhang, L. & Liu, Y. A scoping review: applications of deep learning in non-destructive testing of building conditions. Electronics 14, 1124 (2022).

Patrucco, G., Gómez, A., Adineh, A., Rahrig, M. & Lerma, J. L. 3D data fusion for historical analyses of heritage buildings using thermal images: The Palacio de Colomina as a case study. Remote Sens. 14, 5699 (2022).

Mercuri, F. et al. Infrared thermography applied to the study of cultural heritage. Int. J. Thermophys. 36, 1189–1194 (2014).

Orazi, N. The study of artistic bronzes by infrared thermography: a review. J. Cult. Herit. 42, 280–289 (2020).

Sutherland, N., Marsh, S., Priestnall, G., Bryan, P. & Mills, J. Infrared thermography and 3D-data fusion for architectural heritage: a scoping review. Remote Sens. 15, 2422 (2023).

Dritsa, V. et al. Thermographic imaging in cultural heritage: a short review. Sensors 22, 9076 (2022).

Li, X.-L. et al. Application of nonlinear data fitting method to thermal diffusivity of carbon-carbon composite measured by transmission pulsed thermography. Acta Phys. Sin. 66, 188702 (2017).

Mercuri, F. et al. Interface thermal conductance characterization by infrared thermography: a tool for the study of insertions in bronze ancient statuary. Infrared Phys. Technol. 90, 31–39 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62305234), Open Project of the Key Scientific Research Base of Metal Conservation (National Museum of China) (2024JSBH007), as well as Beijing Social Science Fund (23LSC011) and Scientific and Technological Research Projects of Cultural Relics under the National Cultural Heritage Administration (2023ZCK 002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Y. and B.C. conceptualized the study; Z.X. performed data curation and investigation; X.Y., B.C., and W.L. acquired funding; X.Y. developed the methodology; C.W. provided resources; Z.X. and H.T. conducted validation; Z.X. created visualizations; Z.X. wrote the original draft; X.Y., B.C., and W.L. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, Z., Yang, X., Tang, H. et al. Multimodal non-destructive analysis of bronze mirror combining IR thermography and 3D scanning. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 525 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02104-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02104-z