Abstract

Interest in tattoos has grown significantly due to their cultural, artistic, historical, and anthropological value, representing personal and social expressions that reflect traditions and identities across different cultures. This study examined tattooed skin fragments preserved in the “Luigi Cattaneo” Anatomical Collection (Bologna), recently restored for the exhibition “TATTOO - Tales from the Mediterranean” at the MUDEC Museum in Milan. Non-destructive spectroscopic techniques were employed to characterize the chemical composition of pigments and organic materials, and to assess their preservation state. The results supported the conservation process and enriched the scientific and cultural significance of the collection. This research documents a nearly disappeared cultural practice, offering valuable insights into the moral, social, and religious dimensions of tattooing in 19th-century Italy. The work contributes to understanding tattooing’s evolution from a devotional and identity-based practice to a contemporary art form, illuminating a unique aspect of Italian cultural history.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The term “tattoo” was coined in 1769, when the English Captain James Cook landed in Tahiti, observed and documented the customs of the local population, and transcribed for the first time the word Tattow (later “tattoo”)1,2, using it for describing the human impulse to embellish their own bodies3. However, the most ancient evidence, for instance, comes from a mummified man dating back to 3000 BC, rediscovered in the Ötztal Alps on the Italian-Austrian border in 1991 4. In Classical Antiquity, tattooing had a punitive purpose: Persians, Thracians, ancient Greeks, and ancient Romans all had the custom of marking slaves and prisoners, particularly those who attempted to escape, with signs, although sometimes it was more a question of branding with heated irons, which revealed the nature of their crime punishment5. According to historical evidence, the practice was banned by Emperor Constantine after his conversion to Christianity, likely in reference to the prohibition in Leviticus 19:28, and Corinthians 6:19–205,6. However, tattooing in Bible did not necessarily carry a negative connotation. As reported in ref.7 there were several references to the practice of body marking, both in the Old and in the New Testament. The practice, related to the experience of Christ’s pain and suffering, could have been, for Early Christians, a sign of their affiliation with the new religion, transforming a “humiliating mark” of slavery into a sign of “divine election”5,6,8. During the Crusades, those without religious symbols on their bodies could not be buried in consecrated ground. Since objects that testified to religious affiliation, often made of gold or other precious materials, could be stolen, tattoos emerged as a more permanent and secure alternative9. Throughout the medieval period, Christian pilgrims tattooed themselves with religious symbols to commemorate the sanctuaries they visited, a practice still widespread among the Copts10. Tattooing, whose origins date back to prehistoric times, has continued in the Western world, evolving in method, use, and meaning throughout history, since at least the late Middle Ages8.

On the other hand, the particular aspect of collecting tattooed human skin represents a dark and little-known side of human heritage, a form of “black heritage”11. These collections frequently raise important ethical and moral questions related to the treatment of human remains, their conservation and display, issues on which the debate has particularly intensified in recent years12,13,14.

Scientific interest in tattoos has deep roots and developed notably between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when tattoos were not merely regarded as artistic or cultural expressions but also as elements of medical, legal, and anthropological interest15,16,17. In this period, tattoos were analyzed for their symbolic value, their connection to individual and collective identities, and their significance in specific contexts, such as social and criminal settings. In criminology, tattoos were used to identify individuals involved in criminal activities or belonging to specific groups, such as gangs or clandestine organizations. In this context, they were believed to represent visible indicators of affiliation or social status, often recorded as evidence in police files. From an anthropological point of view, researchers analyzed tattoos as cultural and traditional practices, studying their origins, techniques, and meanings in various societies and indigenous populations18, providing insights into the cultural history and spiritual or religious beliefs of different communities. These aspects were linked to those of psychiatry: tattoos were sometimes viewed as signals of specific psychological or behavioural traits, associated with disorders, trauma, or the expression of personal identity19.

Especially during the 19th century, the field of Anatomy and Forensic Medicine became increasingly involved in research and understanding of tattoos. Criminologists from Italy and France began to systematically study this practice: convicts’ tattoos were then associated with stories of corruption and quickly became a strong symbol of crime20,21. Hence, tattoos came to be viewed negatively, not only as a sign of discomfort or censorship, but also as a semantic marker within the prison world, especially with the spread of the theories of Cesare Lombroso22,23. With the publication in 1876 of the essay The Criminal Man, Lombroso closely correlated tattoos with the innate moral degeneration of criminals:“the tattooed sign is among those anatomical anomalies capable of recognizing the anthropological type of the criminal. The born criminal shows specific anthropological characteristics that bring him closer to animals and primitive men and the act of tattooing repeat criminals is a symptom of a regression to the primitive and wild state” 24. The essay is filled with descriptions of tattoos and the stories of the men who wore them - soldiers, but above all, convicts, criminals and deserters. It became an in-depth catalogue of all the various types of tattoos found at the time, providing a broad glimpse into the customs and social codes of the period. Lombroso categorized tattoos into several groups: signs of love (initials, hearts, verses); symbols of war (dates, weapons, coats of arms); occupational signs (work tools, musical instruments), religious symbols (crosses, images of Christs, Madonnas, saints), and animals depictions (snakes, horses, birds). Interestingly, some of the secret symbols documented by Lombroso are still used today by members of the Camorra, an Italian criminal organization with mafia connotations24.

The lack of scientific evidence in Lombroso’s theories, along with the classism, racism, and sexism underlying his interpretations of tattooing, has rendered his ideas largely outdated in modern times, freeing the practice of tattooing from subjective judgment, and reaffirming it as what it has always been: an “intimate expression of identity”25,26. Regardless of the negative judgment we assign to these theories today, the association between crime and tattoos likely spread across Europe. By the end of the 19th century, in Poland, prisoners’ tattoos were removed postmortem from their bodies and stored in an archive in an attempt to identify links among inmates27. These kinds of studies led to the preservation of tattooed skin in museums dedicated to criminology, natural history, anatomy, and in university collections. The aim was both educational and scientific, allowing scholars to deepen their understanding of the human body, social behaviour, and cultural traditions28.

The work here presented stemmed from the interest in studying and characterizing fragments of tattooed skin preserved at the “Luigi Cattaneo” Anatomical Wax Collection. In 2024, these fragments were requested for the exhibition “Tattoo. Tales from the Mediterranean” organized from March 28 to July 30, 2024 at the Museum of Cultures in Milan (MUDEC) and curated by Luisa Gnecchi Ruscone and Guido Guerzoni, in collaboration with Jurate Francesca Piacenti29. The exhibition traced the history of tattooing from prehistoric evidence to the present day, focusing particularly on the Mediterranean area, but also showcasing extra-European materials to provide an opportunity for a global and more in-depth study of the items involved in this analysis.

The “Luigi Cattaneo” Anatomical Wax Collection is part of the University of Bologna Museum Network (SMA, consisting of 15 facilities dedicated to various academic and research disciplines) and is hosted at the Anatomical Institutes. The original nucleus of the Museum of Human Anatomy dates to 1742, when pope Benedict XIV sponsored the project to establish a “stanza della notomia” (anatomy room) at the Academy of Sciences of Bologna Institute. At that time, Bologna was already a museological hub of great importance, and it would continue to be so over the centuries30. In 1907, the collection, by then significantly expanded, was moved to the newly built Anatomical Institutes, where it was displayed in magnificent gilded showcases. At the end of the 1990s, the Museum’s layout underwent a major transformation: the 18th-century wax models were transferred back to the original anatomy room at the Academy of Sciences. The resulting display space, though almost empty, remained visually striking and provided an opportunity to reconstruct the 19th-century context by bringing together, under the same roof, sections of normal and pathological anatomy, as had been the case during the 19th century. Therefore, after a period of closure, the Museum reopened in 2002 under the new title “Anatomical Wax Collection” and was named after Luigi Cattaneo (1925 – 1992), professor of human anatomy and distinguished scholar of science and art.

It hosts an impressive collection of waxwork models, natural dried specimens, injected preparations, scientific instruments, anatomical illustrations, and tomes of the “Memorie dell’Accademia delle Scienze” (essays of the scientific academic discussion), all dating back to the 19th century. It is a heterogeneous assemblage of diverse human remains, as was common in the context of the 18th- and 19th-century collecting, which originated from the cabinet of curiosities. Such cabinets, designed to attract and astonish visitors by displaying unique objects, ensured public and popular exhibitions at fairs, circuses, and freak shows. Over time, due to their expansion and a more scientific approach, these collections became unified under the aegis of public institutions and served as instruments for research and teaching31.

At the “Cattaneo” Collection, the main topics were pathology and congenital malformation, reflecting the growing interest among scholars of anatomy for “monstrosity”. In fact, Bologna was the first university to institutionalize the teaching of pathological anatomy in 1859. The modus operandi for investigating, describing, and presenting a clinical case began with an autopsy. A detailed publication in the “Memorie dell’Accademia delle Scienze” would have followed, and the removed organs were then processed to obtain dried anatomical specimens. These were accompanied by tables, engravings, and wax replicas, which together served both as iconographic materials for the published paper, and as didactic tools to be displayed32. Moreover, late 19th-century scientific investigations also focused on physical anthropology, through which scholars ascribed objects with meanings often associated with primitivism and criminality. It is worth mentioning an impressive collection of over two thousand skulls, as well as objects dispersed across different showcases and displayed with no clear connection to a systematic classification, such as tattooed skin flaps. Unfortunately, neither archival records nor reference to the harvesting and processing of these samples have survived, and it is interesting to note that this lack of documentation is quite common in European museum collections of tattooed skin17,33,34.

Nowadays, the “Luigi Cattaneo” Anatomical Wax Collection represents a popular destination for scholars, students, and the general public, all united by their curiosity about this impressive cultural heritage. It preserves and promotes its collection through didactic, educational, scientific, and restorative initiatives combining tradition with technological innovations. The ethical awareness required when exhibiting human remains, recognized as sensitive material, is addressed by considering their cultural and social significance, public reception, and the fundamental value of human dignity35,36.

The fragments of tattooed skin requested for the exhibition at MUDEC were discovered a few years ago in the storage house of the Department of Biomedical and Neuromotor Sciences (DIBINEM) at the University of Bologna and were retrieved by Professor Luisa Leonardi, who was, at the time, the Scientific Curator of the “Luigi Cattaneo” Anatomical Wax Collection. The tattooed skin fragments were displayed primarily for conservation purposes, with the aim of preserving and protecting them from further deterioration, prioritizing their safeguarding over public exhibition. As mentioned earlier, little information was available about the fragments, despite extensive archival and inventory research. Their placement in a display case was therefore a measure driven by conservation needs, pending further studies aimed at their proper enhancement.

The opportunity for a more detailed analysis arose within the framework of a multidisciplinary collaboration that enabled non-invasive examinations as part of a research project on museum artifacts. This initiative aligned with the institution’s commitment to scientific research, which represents, on the one hand, a key aspect of its management policy and, on the other, a reflection of the true nature of its collections, which have evolved over time through studies conducted by scholars in Bologna over the centuries.

The study, which involved the management of collected human remains, obtained ethical approval from the University of Bologna Bioethics Committee (Prot. 0184746, 02/07/2024).

Methods

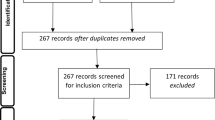

The entire tattoo collection was mounted on two black-painted wooden panels, identified with inventory label “Anatomia Umana Normale” (Normal Human Anatomy) 67a and 67b, and bearing, respectively, fourteen and five fragments of human skin with tattoos, along with a paper label providing summary information (Fig. 1). Before the conservation treatment, the fragments were anchored to the wooden panels with metal fasteners (tacks and nails), probably dating from different historical periods.

Table 1 and Fig. 2 present a summary of the skin samples, including indications of the subject depicted and the colours of the inks used. Sacred and profane themes were identified based on the available literature and the historical photographic documentation, such as those reported in ref. 37. The examined tattoos reveal a rich religious symbolism and offer valuable insights into the historical and devotional context of pilgrimages. The presence of specific elements, such as those related to the Holy House, underscores the importance of these artifacts as historical and cultural testimonies. The inclusion of cosmic symbols such as the sun and moon, along with the ornamental details of the Holy House, suggests a deep connection between tattoos and popular devotion. These elements not only commemorated visits to shrines but also symbolized the participation of all creation in Christian redemption38.

The skin fragments show clean-cut edges. Due to the absence of jagged edges and holes typically associated with tensioning and drying process, such as those described in ref. 39 reporting on the work of Stieda40, it is possible to assume that the tattooed skin fragments were trimmed after conservation treatments.

They vary in thickness, likely due to the fleshing process. In some samples, the human skin is so thin that the colour of the underlying panel dominates, reducing the necessary contrast for an optimal readability of the tattoo. In contrast, others are so thick that they still show the texture of the connective tissue.

Moreover, the fragments showed powdery deposits, stains of various natures, discolouration, undulations, small holes, and colour alterations, all of which negatively impacted the readability of the tattoo subjects. The use of inadequate metal fastenings caused additional mechanical and chemical damage to the skin, leading to numerous holes, strong undulations, and traces of oxidation.

Furthermore, a clumsy cleaning attempt probably transferred black paint from the wooden panels onto the skin and paper labels, resulting in colour inhomogeneities and further compromising the legibility of the specimens.

The Loreto tattoo fits into the long history of tattooing as an extremely particular practice, geographically confined to central Italy and intimately connected to the pilgrimage to the Holy House of Loreto. According to the fascinating legend of this sanctuary, the Holy House of Nazareth, where the Virgin Mary received the Annunciation and where Jesus lived, was taken by some angels and carried away from Palestine, which at that time was under the rule of the Mamluks of Egypt (1291). The House was first left in Croatia; then, to protect pilgrims from criminals and thieves, the angels decided to lift it up again and bring it to Italy. After at least three different flights to various locations in the Marche region, the angels placed it in its current position in 1294, on the night of December 10th 41.

Since the founding of the sanctuary, the inhabitants of the surrounding territories (especially those of central Italy) began to undertake pilgrimages to the Holy House, often facing hardship along the way. As a sign of having completed the pilgrimage and as an act of devotion, they were marked with a tattoo on the forearms or wrists, attesting to their faith, much like the tradition of wearing medals. This extreme form of ex-voto represented a request for salvation through the intercession of Mary, creating a physical bond with the Passion of Christ, and evoking the transfiguration of Christ’s pain on the cross and of Saint Francis in receiving the stigmata (hence the placement of the tattoo mainly on the wrists)8,42.

This intimate bond with faith is reflected in the subject of the tattoo, which always has a strong symbolic value: the effigy of the Madonna of Loreto, crucifixes in various forms, emblems of the Passion of Christ, symbols of the Eucharistic sacrament, Christograms, all-seeing eye, archangels, the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and the Heart of the Seven Sorrows, sometimes accompanied by the year of the pilgrimage37.

The scarcity of documentation regarding this practice is probably because it was mainly carried out by pilgrims from peasant and rural contexts38. This practice must have been so common and widespread that it did not even arouse the interest of scholars who studied tattoos among “barbaric and primitive populations” as defined by Caterina Pigorini Beri in her work published in 188937,43.

According to Pigorini Beri, the practice of tattooing following the pilgrimage to the Holy House of Loreto has been attested since at least the pontificate of Pope Sixtus V (1585–1590). Her reconstruction was mainly based on the images present on some wooden cliché, employed as stamps and line-guides by the “marker” who performed the tattoo (see Fig. S1_1 in Supplementary Information_1). In particular, the presence in some of these tables of the depiction of the “Madonna del Pero” (Mary sitting on the foliage of a pear tree crowned by two putti) recalls the coat of arms of both the city of Loreto and of the Pope himself, who had granted the use of his coat of arms to the city37,38.

Attestation of this practice also comes from the stories of Antonio Stoppani collected in his work “Il bel Paese”, published in 1876, in which he described the execution of tattoos in the streets of Loreto during the celebrations for one of the anniversaries associated with the sanctuary. The author identified shoemakers as the individuals responsible for performing the tattoos, who attracted the attention of the pilgrims by banging together the wooden stencils used to create the designs. Although to the practice and the pilgrims were decidedly negative, the source is significant as it provided the earliest detailed visual description of the tattooing procedure. Once the image was selected from the stencils, it was impressed on the skin using black ink and then, permanently marked by means of an iron stiletto, which was used to pierce the skin to the point of bleeding, thereby allowing the ink to be absorbed38,44.

Antonio Stoppani’s experience probably refers to events that occurred a few years before the publication of his volume, since on November 25th, 1871, the Municipality of Loreto imposed a ban on tattooing by approving a proposal submitted by the lawyer Augusto Ciccolini. As well described by Bagattini in his thesis38, in addition to health-related reasons, the ban likely reflected the influence of positivist ideology, which sought to modernize the country by moving beyond certain religious practices deemed to be closely associated with superstition. Interestingly, Bagattini links the ban to the work of Cesare Lombroso, who also described the practice of tattooing in Loreto, clearly with a negative connotation, in his own writings24. More broadly, Lombroso associated the practice of tattooing with anatomical and psychological anomalies indicative of moral degeneration, remarking the connection between tattoos, lower social classes, and criminality24. According to Lombroso, when criminals received a tattoo of the Madonna of Loreto, it was not an expression of religious devotion, but rather a behaviour characteristic of the so-called of “savage” populations, thus relegating the practice to the realm of superstition and the apotropaic rituals22.

Despite the ban, the practice of tattooing in Loreto persisted. A description of the tattooing technique can be found, for example, in the work of Pigorini Beri. It remains unclear whether her account is based on second-hand reports or direct observation, given that the practice had already been officially banned at the time. According to her description, after inking the cliché and pressing it onto the skin to leave an imprint, the operator, using a pen made up of three sharp steel points hafted to a handle with a binding of thick, tarred thread, traced the contours with a series of dense punctures. Once the outline was completed, the operator stretched the skin slightly on either side until bleeding occurred; at that point, a blue ink (indigo) was applied, which penetrated and fixed into the dermis. Reportedly, any resulting pain disappeared within 24 hours37. A similar description can be found also in45 which specified the use of a cloth dipped in blue ink that was rubbed onto the punctured area to facilitate the ink absorption.

More recent research reconstructed tools and procedures not dissimilar to those just described46, underlining the hygienic issues and the use of common household ingredients for the ink recipe, such as lampblack, mistrà liqueur, and cherry juice42.

Currently, the tradition of the Loreto tattoo is still carried on by a professional tattoo artist from the Marche region, Jonatal Carducci, who has thoroughly studied historical sources and collected them alongside oral testimonies from people involved in the practice of the Loreto sacred tattooing (https://www.tatuaggilauretani.it/leonardo-conditi-la-storia-dellultimo-marcatore-lauretano). Figure 3 shows the tattoo artist at work (A) using a replica of the cliché traditionally employed to transfer the drawing onto the skin, and the tattooing tool built on the basis of the written and oral sources (B, C). It also includes a comparison with similar original instruments employed for the same traditional practise in Jerusalem8, currently carried on by the tattoo artist Razzouk (D) (https://razzouktattoo.com/pages/history). The authors have obtained written consent to publish the images and the details of the person filmed during the tattooing procedure.

In the classification of tattoos reported by Pigorini Beri in her aforementioned work, tattoos with love subject were also reported among those performed in Loreto. Different images of hearts (among which also the Sacred Heart of Jesus), a heart tied with chains, and dove with olive branch as symbols of peace were usually tattooed, often representing a naive combination of sacred and profane elements. According to the scholar, such tattoos were found on young brides, widows, and even sailors37,42.

De Blasio also dedicated part of his study to love tattoos, noting that many criminals he examined exhibited tattoos on the chest, at the height of the heart, dedicated to a loved woman, and often accompaniend by her name45. In his work, he distinguished between love tattoos, expression of simple and sincere affection, and what he referred as “obscene” tattoos. The latter were often explicit pornographic images, crudely rendered in a rudimental style, yet relatively widespread. The judgement expressed by the 19th-century positivist anthropologists such as Cesare Lombroso was strongly negative. In their view, erotic arousal in such individuals could be provoked merely by the observation of their own tattoos, even something as simple as the initials of a lover’s name. According to these scholars, erotic and obscene tattoos therefore represented a surrogate form of pornography for lower classes, typically uneducated and often illiterate individuals, who could not access erotic literature that was popular at the time22,23.

Three human tattooed skin specimens, the first two with religious themes and third with an erotic one, were selected from the group of artifacts. The two religious skin specimens (1A and 6A) came from wooden panel 67a, while the erotic one (5B) from panel 67b (Figs. 2 and 3 and Table 1). The selection process was conducted according to several criteria, including iconographic theme, the state of preservation, the thickness of the skin flaps, and the presence of peculiar characteristics such as coloured details.

The skin sample 1A contains two discoloured and poorly preserved tattoos. The upper part features a depiction of Madonna of Loreto, while the lower part shows a more detailed Sacred Heart. Both tattoos appear drawn in a bluish or black faded ink. Additionally, the Madonna tattoo exhibits some red-coloured spots possibly representing shoes and some decorations of the gown (Fig. 4a).

The skin sample 6A features a total of four tattoos: the one in the upper part of the skin specimen depicts a Madonna of Loreto with Child and reports the date, 1881, likely indicating the year when the tattoo was done. This representation of the Madonna of Loreto reports some decorative details such as lamps and an iconostasis arch surrounding the Madonna. These elements resemble the architectural features installed in the Holy House of Loreto during the renovation works in 1885, which were later removed after the fire that occurred inside the Holy House on 23 February 192138. The discrepancy in dates suggests that even before 1885 (precisely 1881), the statue was placed inside a similar arch of the iconostasis. In this sense, the tattoo could serve as an indirect visual testimony of the presence of a decorative apparatus, including lamps, around the simulacrum of the Madonna Lauretana, preceding the intervention of the architect Sacconi (designer of the aforementioned iconostasis arch). In personal communication with the authors of this work, A. Bagattini reported on the discovery of some representations of the Madonna of Loreto, in particular a postcard bearing a French-made engraving dated 1880, in which a conspicuous number of hanging lamps can be recognized, even more numerous than those currently present. Further historical-artistic research on this material is ongoing.

The central part of the skin sample displays a monstrance, while the lower left and right corners feature a sun and a Sacred Heart, respectively. All tattoos are rendered in black ink (Fig. 4b).

The skin sample 5B depicts a naked woman in profile with male genitalia in her hand and sticking out her tongue. The woman’s outline is tattooed in black ink and appears to be wearing boots or socks, which seem to be tattooed in brown ink. The pubic region appears to be accentuated by a reddish ink. (Fig. 4c). An interesting comparative study could explore the convention of representing women in erotic and pornographic themed tattoos wearing boots or socks. Notably, similar motifs can be found in tattoo specimens from the collection of the Department of Forensic Medicine at Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland27. Moreover, a closely comparable representation of a naked woman wearing boots or socks is also present in the thesis of Dr. Pontecorvo, who graduated in 1891, from the University of Rome in medicine and surgery. In his thesis, entitled “The tattoo and its anthropological and medico-legal importance”, Table 4, Fig. 9, illustrates this erotic tattoo (Images and an excerpt from the thesis are available at the link https://www.tatuaggilauretani.it/il-tatuaggio-importante-antropologica-e-medico-legaletesi-di-laurea-del-dott-carlo-pontecorvo-roma-1891).

Non-invasive and non-destructive techniques play a crucial role in the study and conservation of artworks, manuscripts, sculptures, and archaeological findings. Among the most widely used methods, infrared (IR) spectroscopy enables the identification of organic and inorganic compounds by analyzing molecular vibrations, making it particularly useful for characterizing pigments, binders, and degradation products. X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy, on the other hand, provides elemental composition data without requiring direct contact with the artifact, aiding in material identification and provenance studies. These techniques allow conservators and researchers to assess deterioration, authenticate works of art, and develop targeted conservation strategies while preserving the physical and historical integrity of cultural heritage objects.

In this study, both IR and XRF analyses were performed on tattooed skin fragments thanks to the collaboration between the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) and the Chemical and Life Science branch (SISSI-Bio)47 of SISSI beamline of Elettra Sincrotrone Trieste. Access to the Elettra facility was granted by the Central European Research Infrastructure Consortium (CERIC-ERIC) as part of a research call for scientific excellence. The proposal project was selected, receiving recognition for its originality, innovation, and contribution to advancing knowledge in the field. Fig. S2_1 in Supplementary Information_2 provides a comprehensive visualisation of all the areas and spots measured with both IR (red frames) and XRF (green frames) spectroscopy.

Infrared spectroscopy is based on the interaction of infrared radiation with matter and allows for the identification of chemical bonds and functional groups present in the analyzed materials. Specifically, this technique provides information on the chemical composition of the skin and the tattoo pigments, determining the organic or inorganic nature of the components. In this study, the Micro-Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (µ-ATR FTIR) method was employed.

Several points on each sample were analysed using a Bruker VERTEX 70 v interferometer coupled with the Hyperion 3000 Vis/IR microscope. The microscope was equipped with a 20× micro-ATR objective with a germanium IRE (Internal Reflection Element), and imaging measurements were performed with a conventional IR source (Globar) and FPA (focal plane array) detector (64 × 64 sensitive elements), with 8 × 8 pixel binning (pixel size ~ 4 μm). Each FPA map was collected by averaging 128 scans at a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1. All the FPA maps were corrected for atmospheric contribution, rubberband baselined, and vector normalised.

X-ray fluorescence is a technique based on the interaction of X-rays with the atoms of the material, inducing the emission of radiation characteristic of the present chemical elements. For this study, Macro-XRF (MA-XRF), an advanced version of XRF designed for spatial mapping of elements over large surfaces, was employed48. Unlike conventional single-point analysis, MA-XRF uses a scanner to collect data over extended areas, providing both elemental mapping and spatial visualization of their distribution in the sample’s surfaces.

The experimental MA-XRF scanner used for this study is under development as a collaboration effort between NSIL-IAEA49 and MLAB-ICTP. It uses a precision mechanical system with automatic detector-to-sample distance adjustment, ensuring uniformity in photon collection and allowing scans as close as 1 mm from the surface of the object. This close proximity enhances the signal-to-noise ratio by collecting a higher number of photons per unit of time. The X-ray tube has a palladium (Pd) anode target, operated at 50 kV and 500 µA, with a collimated spot size of ~500 µm50. The scanner also has a silicon drift detector (SDD) with 10 mm2 active area and 8 μm beryllium entrance window51. With this setup, the typical analysis energy range is from ~2.3 keV to ~32.2 keV, which allows to check of the presence of chemical elements from sulfur to barium. The data acquired by the SDD are processed by a Brightspec Topaz-X multichannel analyzer (MCA) in a time-list acquisition mode with 40 μs of time resolution52.

The scanning was performed using a horizontal raster path with vertical steps of 500 µm and different speeds ranging from 0.7 to 5 mm/s. The speed was adjusted to ensure a sufficient photon collection rate depending on the material composition and concentration of fluorescent elements. The elemental map reconstruction was carried out by plotting the number of collected photons per pixel at characteristic element XRF energy ranges. The photons collection was performed in continuous mode obtaining the energy and acquisition time of single photons allowing to reconstruct elemental maps with different pixel sizes, a technique named single-photon mapping53. The acquired spectra were then analysed using the bAxil software used to identify and select the ROIs corresponding to specific elemental signatures54.

In support of spectroscopic analyses, optical microscopy images were collected on the recto/verso of the samples with different equipments. Optical images were collected with a Stand K LAB ZEISS Stemi 305 equipped with reflected light LED electronics and a tiltable mirror-based transmitted light unit, with manual zoom magnifications ranging from 0.8× to 4.0×. Moreover, a Dino-Lite Premier Digital Microscope AM4113T has been used to collect images after the restoration treatment.

Results

The optical images collected on the specimens showed different pigmentations of the untattooed skin (Fig. 5a–c). It is possible to notice that hair has not been removed from the skin during the process of preserving the specimens after their removal from the body. Specimen 1A showed brown hair (Fig. 5a), while white hair has been observed on specimens 6A and 5B (Fig. 5b, c), possibly suggesting a difference in the age at death of the individuals. In addition, on the front side of the specimens, epidermis furrows are clearly recognizable. Panels d and e of Fig. 4 show details of the tattooed skin in blackish and reddish inks on specimen 1A, and black ink on specimen 6A. Panels f and i show different pigmentations observed in the pubic region (red and black) and in the socks area (brown), respectively, on specimen 5B.

The observation of back side of the skin samples 1A and 5B (see Fig. S2_2 in Supplementary Information_2) revealed the presence of a peculiar structure characterized by rounded hollows, of diameter ranging between 50 and 200 µm (see Fig. 5g) associated with greyish fibers dispersed across the sample and particularly evident especially on specimens 1A (red arrow in Fig. 5g). These hollows may represent the dermal ridges, suggesting that, during the procedure of preservation of the tattooed specimens, only the epidermis was removed and stored. One of the fibers was collected from the back side of specimen 1A (panel h) to be analyzed by IR microscopy in transmission mode. The tattoos are not visible on the back side of these two samples. Conversely, on the back side of sample 6A the tattoos were clearly visible (see Fig. S2_2 in Supplementary Information_2), suggesting a deeper penetration on the ink in the skin during the tattooing procedure, or the removal of a thinner layer of skin for this specimen, during the preservation procedure, if compared with the two previously described samples.

Figure 6a shows a comparison between the average spectra of one point of untattooed skin from specimen 6A (Fig. S2_1b, skin1 red frame) and the fiber collected from the back side of specimen 1A. Both the spectra show very intense Amide I and II band peaked at 1655 and 1540 cm−1, respectively. The Amide I band originates from the C=O stretching vibration (~80%) and from both CN stretching and NH bending vibrations (~20%), while the Amide II is due to C-N stretching and N-H bending vibrations. In the 1310–1175 cm−1 spectral range the Amide III, associated with CN stretching and NH bending vibrations (~30% each), CC stretching (~20%) and CH bending (~10%), can be observed55. Interestingly, the Amide III of the fiber (red spectrum) shows a more intense and well-defined profile if compared with the black spectrum of the untattooed skin. Its peculiar shape, characterized by a main peak at 1235 cm−1 and two weaker peaks at 1280 and 1205 cm−1, allows us to recognize the fiber as composed by pure collagen55. The position of the Amide III main peak and the presence of an additional peak at 1335 cm−1, usually associated with aggregated collagen structures, suggest a strong dehydration of the collagen fiber56. It is interesting to highlight that collagen fibers in close association with dermal ridges may represent residues of type IV collagen forming sheets in basement membrane, or type VII collagen forming anchoring fibers and acting as dermoepitelial junction57.

a IR spectra of untattooed skin of sample 6A (black line) compared with collagen fiber collected from the back side of sample 1A; b Representative IR spectra extracted from both tattooed and untattooed skin spots on sample 1A and 6A, c XRF spectra comparing untattooed and tattooed skin spots; d Area comparison for sulphur, calcium, iron and zinc on black ink in sample 6A and bare skin; e XRF maps of zinc and copper on specimen 5B and false-colour map showing the elements distribution, f IR spectrum of zinc carboxylates from red ink on sample 1A (inset: false-colour map obtained by integrating the 3000–2800 cm−1 spectral range, the average IR spectrum has been extracted from the hotspot).

Archives reporting information on the process of removal and preservation of the skin specimens for anatomical purposes were not found in the museum collection. However, FTIR measurements provided results that can be useful for a possible reconstruction of the procedure. In almost all the analyzed points collected on the three specimens, intense signals of calcium carbonates at around 1410 cm−1 and calcium carboxylates, at 1575–1540 cm−1, were detected. Figure 6b plots, as example, some representative spectra extracted from both untattooed and tattooed spots (see red frames, skin2 and black2 in Fig. S2_1b) of specimen 6A, ahowing the aforementioned characteristic features (red, black, and green lines). This evidence can suggest a possible use of lime (CaO and Ca(OH)2) or calcite (CaCO3) for preserving the skin. Since ancient times, these compounds were used for dehairing during the first phases of parchment production58. However, as it is possible to appreciate from the optical images in Fig. 5a–c, in this case, hair has not been removed. These compounds sometimes can react with skin components to produce gypsum (CaSO4•2H2O)58. Traces of gypsum were detected in both specimens 1A and 6A and the related spectra are shown in Fig. 6b, pink and purple lines.

Two single-points XRF measurements were collected on a tattooed and on an untattooed spots of sample 6A (see Fig. S2_1b, small green frames labelled skin1 and black2). The obtained spectra, reported in Fig. 6c revealed a significant increase in the number of photons collected around the peak of interest corresponding to sulfur, with an increase of the relative abundance of photons from 0.11% to 0.57% on the K-line at 2.758 keV; calcium, with an increase from 1.2% to 2.02% on the K-line at 3.69 keV; and zinc, with an increase from 0.48% to 0.78% on the K-line at 8.631 keV. In contrast, other elements, such as iron, showed little abundance variation, increasing only from 0.81% to 0.87% on the K-line (6.399 keV), as shown in panel 6d. To ensure a fair comparison, both spectra were normalized by the total number of photons collected and overlaid. The complete comparison of all the elements identified by the XRF analysis for this study is provided in the Supplementary Information, 2 (Table S2_1).

FPA maps collected on a red ink area (Figs. S2, 1a, spot red 1) on sample 1A also revealed details on the presence of zinc. By integrating the 3000–2800 cm−1 spectral range due to CH2 and CH3 stretching vibrations, an intense rounded spot of around 20 µm of diameter was highlighted (see false-colour map, inset of Fig. 6f). The IR spectrum reported in Fig. 6f extracted from this spot showed an intense peak at 1537 cm−1, accompanied by two peaks at 1456 and 1398 cm−1. These features are indicative of the presence of zinc carboxylates, possibly originating from the interaction between zinc ions and skin lipids59. Interestingly, XRF analyses detected intense small spots of zinc (K-line at 8.639 KeV) associated with very low traces of copper (K-line at 8.048 KeV) on the mapped area of specimen 5B (Fig. 6e, elemental maps and reconstructed false-colour map, see also Fig. S2_1c, green frame). In this case, they seem not to be directly correlated with the brown ink as they are spread on the entire mapped surface, potentially outside the tattooed area of the socks. No information was found in the literature about intentional mixing of zinc in red/brown inks or even the possible presence of this element as impurity in the pigments. However, the antimicrobial, disinfecting, and deodorizing properties of zinc chloride (ZnCl2) were well known since the mid-1830s when Sir William Burnett promoted his pioneering patent for his zinc chloride solution to be used both for medical purposes and wood preservation60. We found no precise information about Burnett’s liquid’ application in anatomical specimens preservation practice, however, more recently, Goodarzi et al. tested the efficacy of zinc chloride as embalming agent, proposing it as a healthier alternative to formaldehyde61, allowing us to hypothesize the possible use of a zinc-based solution as a preservative agent for skin specimens under study.

For specimen 6A, FTIR measurements were focused on the ostensory tattooed in black ink. The black spot n. 1 (Fig. S2_1b) did not show any informative features, excepting for the infrared bands, already described in the previous paragraph, due to the skin. On the spot n. 2 (Fig. S2_1b), traces of silicates62, identified by the peak at 1073 cm−1, were detected (data not shown). This finding can be associated with contamination possibly deriving from tools and containers used for ink preparation and storage, or drying agents that could have been intentionally added63,64. On the other hand, the average spectra collected on spot 3 (red frame and black spectrum in Fig. 7a, c) exhibit interesting features in the range 1280–945 cm−1 that could be attributed to C-O, C-O-C, C-O-H vibrations of cellulose, possibly due to traces of unburnt vegetal materials (see green reference spectra in Fig. 7c for comparison)65. These features can be directly correlated with black ink used for tattooing suggesting the possible use of black carbon deriving from the combustion of vegetal materials.

MA-XRF analysis of the area corresponding to the ostensory delimited by the green frame in Fig. 7a, was done at a speed of 1 mm/s. However, the number of acquired photons was not sufficient to observe a significant pattern (see Fig. 7d) above the noise level on the most relevant elements (sulfur, calcium, iron, and zinc) as reported in table 6d, confirming the possible organic origin of the black ink.

FTIR measurements were also performed on the blueish/blackish ink of specimen 1A. One point was collected on the ink of the Madonna, and two on the ink of the Sacred Heart (see Fig. S2_1a). Among these, only one point on the Sacred Heart (point blue2) provided possible information on the ink itself (Fig. 7b), while the other two (points blue1 and blue3 in Fig. S2_1a) showed contributions solely from the skin substrate. As in the previous case, the infrared band in the range 1150–950 cm−1, detected on the blueish ink may indicate the presence of unburnt vegetal materials such as cellulose (blue spectrum in Fig. 7c). This result does not provide any useful information on the chemical composition of a possible blue ink, supporting the more probable hypothesis that the ink used is a carbon black ink which has strongly faded66,67.

The red ink in the Madonna of Loreto tattoo on specimen 1A was analysed by µ-ATR FTIR spectroscopy. Among the three analysed points (Fig. 8a, red frames), only point red2 provided useful information for the characterisation of the red ink, while the other two points mainly showed thecontribution of the skin. The false-colour map inserted in Fig. 8b was obtained by integrating the spectral range 3000–2800 cm−1. The average spectrum extracted from the most intense region of the false-colour map revealed very intense CH2 stretching absorption likely due to compounds characterised by very long aliphatic chains. Moreover, peculiar infrared features in the fingerprint region were detected, showing multiple bands with regular spacing of around 20 cm−1 in the 1350–1150 cm−1 spectral range (panel b). The comparison with the database resulted in a match of 84% with a glyceryl distearate (the reference spectrum is reported in black in panel b). Since the 20th century glycerol was added to tattoo inks as a solvent and carrier for pigments, ensuring the ink achieved the appropriate viscosity for a controlled application during the tattooing process68. Although glycerol is expected to be largely cleared from the dermis after tattooing69, its historical use as a pigment carrier suggests that trace amounts may remain trapped in association with pigment particles. Over time, under specific post-mortem or environmental conditions, interactions between residual glycerol and stearic acid–rich skin lipids could lead to the formation of partial esters such as glyceryl distearate70. However, since glyceryl stearate is also a common emulsifier in cosmetic preparations69, further evidence would be required in order to distinguish ancient in-situ formation from modern contamination, possibly due to past manipulation of the skin pieces. In addition, the pink spectrum also shows weak signals due to the Amide I and II band, due to proteins composing the skin. Another average spectrum (red line in panel b) extracted from the edge of the hotspot in false colour-map showed more intense features at 1538 and 1456 cm−1 if compared with the pink spectrum (see spectrum inset in panel b). These features, together with the multiple bands in the range 1350–1150 cm−1 could also indicate the presence of lead carboxylates71, possibly originating from the interaction between lead and skin fatty acids. The detection of lead can suggest the red ink used is minium, a lead oxide-based (Pb3O4) pigment.

a Optical image of the Madonna of Loreto tattoo on specimen 1A; b left inset: FPA false-colour map obtained by integrating the 3000–2800 cm−1 spectral range of the measured point red2; Infrared spectra (pink and red lines) extracted from the framed areas of the hotspot in false-colour map, glyceryl distearate reference spectrum (black line) is reported for comparison, Right inset: zoom of the spectral range 1700–1350 cm−1; c XRF elemental maps showing the spatial distribution of the main L-lines for lead (Pb) and mercury (Hg). d False-colour map generated by integrating the most intense L-lines of Pb and Hg, overlaid on the optical image to highlight the correlation between elemental presence and the red-spots features.

XRF mapping reported in Fig. 8c revealed a good co-localisation for traces of mercury and lead, corresponding to the faded red spots on the tattoo, as shown in the false-colour map in Fig. 8d. The overlay was done by integrating the most intense L-lines for lead (red) and mercury (green) aligning them with the optical image. Traces of sulphur, calcium, iron, copper, and zinc were found, but not in enough quantity to generate elemental maps with clear correspondence with the object 1A. The presence of Pb3O4 suggested by IR spectroscopy is supported by the XRF results, however the detection of Hg suggests the possible use of cinnabar (HgS) or of a mixture of the two.

As reported by G. Angel, Chinese cinnabar was considered a superior hue because of its exceptional purity and brilliance. However, due to its high cost, in Europe it was often mixed with adulterants such as brick, orpiment, iron oxide, Persian red, iodine scarlet, and minium (red lead)17. This practice could cause a reduction of colour saturation and made the pigment more susceptible to light-degradation over time.

Finally, the IR measurements on specimen 5B have been focused on the reddish/brownish inks used for tattooing the socks and the pubis area of the naked woman (Fig. 9a). The analysis of the ink on the pubis (pubis1) area revealed intense peaks of silicates at 1029–1007 cm−1, which together with peculiar features in the range 3750–3500 cm−1 can indicate the presence of kaolinite (Fig. 9b, red line). This mineral, in association with the reddish colour in the pubis area, could suggest the use of a natural ochre (iron oxides + clay minerals). Similar but less intense features were observed in the average spectrum extracted from point sock1 (panel b, purple line), while peaks of silicates at 1076–1050 cm−1 in the average spectrum extracted from point sock2 can be indicative of the presence of quartz (panel b, brown line).

The XRF mapping of the socks (green frame), shown in Fig. 9c, d, revealed a predominant presence of iron, as indicated by distinct spectral lines at 6.404 KeV (Fe-K-L3) and 7.058 KeV (Fe-K-L2). Manganese was also detected; however, its verification relied primarily on the spectral line at 5.899 KeV (Mn-K-L3), as the Mn-K-L2 line at 6.490 KeV is too close to the Fe-K-L3 line, making it difficult to distinguish between the two. These findings suggest that the brownish colour of the socks was possibly obtained by a burnt umber, a natural pigment composed by a mixture of clay minerals, iron, and manganese oxides (Fe2O3 + MnO2+clay)72.

Infrared measurements also provide some interesting information on the preservation state of the specimens and on possible on-going degradation processes.

The average spectrum in green (Fig. 10b) extracted from the hotspot of the false-colour map reported in Fig. 10a revealed very intense signals at 1625 and 1316 cm−1. They are characteristic of calcium oxalates, a bio-product forming as a consequence of fungi growth and activity73. The RGB map in panel c was obtained by integrating the carbonates band in the range 1500–1350 cm−1, the oxalates one in the range 1340–1290 cm−1 and the carbohydrates region in the range 1200–900 cm−1. The map clearly shows the spreading on the fungi colony in blue, inducing the formation of calcium oxalates (in green) in close proximity of spots of calcium carbonates (in red).

a False-colour map of point sock1 on specimen 5B; b average spectra extracted from the framed area in a, b (green and black lines, respectively); c RGB map from untattooed skin spot (see skin1in Fig. S2_1a) on specimen 1A.

Discussion

The study focused on tattooed human skin samples preserved at the “Luigi Cattaneo” Anatomical Wax Collection of the University of Bologna (inventory label “Anatomia Umana Normale” 67a and 67b), with particular reference to three of them, identified as 1 A, 6 A, and 5B, selected for more in-depth chemical investigations. The main purpose of this work was the comprehensive characterization of tattooed skin fragments in order to identify the most appropriate strategies for the restoration and conservation of these unique artifacts. The application of non-invasive spectroscopic techniques allowed the characterization of historical tattoo pigments, shedding light on past tattooing practices while preserving the integrity of these delicate organic materials for future studies. At the same time, the material analysis of these samples provided the opportunity to explore historical, cultural, and anthropological aspects of tattooing. This included the documentation of oral histories related to the practice of the Loreto tattoo, made available to scholars through newly collected audio sources (see Supplementary Information 1). Morphological analysis of the posterior side of the samples revealed rounded cavities with diameters ranging from 50 to 200 μm, associated with grayish fibers, and probably corresponding to dermal ridges. This anatomical structure provides essential information to understand the structure and fragility of the material, but it also sheds light on the procedure of preparing the anatomical specimens. In fact, it suggests that during the conservation process only the epidermis was removed and preserved, leaving characteristic imprints of the underlying dermal architecture.

Furthermore, FTIR analyses of the historical conservation treatments identified intense signals of calcium carbonates at approximately 1410 cm⁻¹, calcium carboxylates in the 1575–1540 cm⁻¹ range, and traces of gypsum in some samples. These spectroscopic signatures suggest the historical use of lime (CaO, Ca(OH)₂) or calcite (CaCO₃) for preservation, compounds traditionally employed in parchment production. The detected presence of zinc compounds could indicate the use of zinc chloride as an antimicrobial preservative agent, consistent with historical practices for preserving anatomical specimens.

In the analysis of the tattoo inks, the black pigment exhibited consistent characteristics across samples, with spectroscopic analysis revealing the presence of silicates and traces of unburned plant materials, particularly cellulose. These findings supported the hypothesis that the black ink was composed of carbon black derived from plant combustion, with residual organic matter indicating incomplete carbonization of the source material. The organic origin of these black pigments was confirmed by the absence of significant inorganic elements in MA-XRF mapping.

Red and brown inks showed more complex compositions, reflecting different pigment sources and preparation methods. The red ink analysed on the Madonna di Loreto tattoo on sample 1A revealed the presence of glyceryl distearate, suggesting the possible use of glycerol as a solvent or emulsifier from the 20th century. The co-localization of lead and mercury detected through XRF mapping is consistent with the use of minium (Pb₃O₄) and/or cinnabar (HgS), traditional red pigments often mixed to achieve desired chromatic properties and reduce costs.

Brown inks, particularly those found in the sock tattoos of sample 5B, showed the presence of iron and manganese, indicating the use of burnt umber (Fe₂O₃+MnO₂+clay), a natural earth pigment. Additionally, the detection of kaolinite in the reddish tattooed pubic area suggests the use of natural ochre, another traditional earth-based pigment commonly employed in historical tattooing practices.

Current analyses have identified several chemical markers of degradation, providing information on ongoing deterioration processes affecting these historical samples. The formation of calcium oxalates, characterized by spectroscopic peaks at 1625 and 1316 cm⁻¹, indicates the production of metabolic byproducts resulting from fungal activity. The presence of active fungal colonies was confirmed through spectroscopic mapping, showing their role in inducing oxalate formation near calcium carbonate deposits, and revealing a complex degradation pattern that threatens the long-term stability of these artifacts.

The detailed information obtained during the measurement campaign supported and guided the restoration of the tattooed skin fragments, with the main intent of improving the structural stability and enhancing the legibility of the tattoos, while preserving the historical and material integrity of the artifacts. The restoration strategy required careful consideration of the fragility and complexity of the materials, as well as the lack of specific protocols for preservation of tattooed human skin and leather-based anatomical specimens. In defining the treatment approach, the specimens were compared to parchment, due to the shared physical characteristics and the flattening process undergone (probably tension drying). This comparison enabled the application of conservation treatments normally used for parchment, and supported the adoption of well-established practices for the treatment of dried organic materials74.

The fragments were dismantled from the wooden panels and dry-cleaned on the recto and verso using soft brushes, an archival vacuum cleaner with HEPA filter, polyurethane sponge, and PVC-free erasers75. Before any wet cleaning procedure, ink solubility tests were performed with both aqueous and hydroalcoholic (20:80) solutions. The surface of all the fragments was then treated with the aforementioned hydroalcoholic solution to remove small stains and black paint residues, probably deposited during a previous cleaning attempt. The oxidation stains caused by the metal pins were removed using compresses of PVOH/Borax gel, with the addition of a chelating agent (0.5% citric acid)76. To rehydrate the skin fragments, a controlled humidification was performed with Gore-Tex® followed by a flattening by tensioning the skin with magnets on a metal surface. The small losses were filled with Japanese paper of adequate thickness and weight, using 4% dispersion of Methylcellulose MC 2000 in alcohol to limit the release of humidity from the adhesive used.

To respect the history of the objects and their original mounting, the same assembly was maintained with limited variations to make it more suitable for conservation. Specifically, thin museum-grade cardboard spacers were inserted between the skin fragments and the wooden panels to avoid direct contact with the painted substrate. The cardboards, precisely shaped to match the contours of the fragments, were adhered to the panel surface, and the fragments were then fixed onto them using remoistenable hinges. The final result of the aforementioned conservation treatments is shown in Fig. 11. They improved the legibility of the tattoos while preserving their historical authenticity.

The skin fragments on the wooden panels numbered 67a (A) and 67b (B) after the restoration treatments and the relocation on the original frames. When compared with Fig. 2, after the surface cleaning and the flattening treatments, a good improvement in the readability of the figurative apparatus is appreciable.

This work is therefore part of the research that, in recent years, has focused attention on the chemical characterization of these extraordinary objects (see, for instance, the recent works reported in refs. 77,78 but also the less recent works in refs. 67,79,80). The authors propose a methodological framework for the study of historical tattoos, highlighting the importance of the multidisciplinary approach in preserving these unique testimonies of human history. However, some challenges remain, particularly regarding the lack of documentation on the provenance and treatment of the tattooed skin fragments. Further research into historical and archival sources, exploration of their anthropological significance, and comparative studies with similar collections worldwide could support the reconstruction of their complete historical and cultural context.

Looking ahead, this study confirms the need to expand scientific investigations by integrating additional non-invasive techniques to gain a deeper understanding of the molecular composition, past chemical treatment, and ongoing degradation processes affecting historical tattoos. This effort is directed towards the development of tailored conservation protocols for tattooed skin fragments, considering not only their organic nature but also, and above all, the historical and cultural significance they embody.

References

Caplan, J. Introduction. In Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History xi–xxiv. :Caplan, J. (ed.) (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2000).

Pesapane, F., Nazzaro, G., Gianotti, R. & Coggi, A. A short history of tattoo. JAMA Dermatol 150, 145 (2014).

Levi Strauss, C. Le dédoublement de la représentation dans les arts de l’Asie et de l’Amérique. in Anthropologie structurale (Agoras, Paris, 2003).

Deter-Wolf, A., Robitaille, B., Krutak, L. & Galliot, S. The world’s oldest tattoos. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 5, 19–24 (2016).

Jones, C.P. Stigma and tattoo. In: Caplan, J. (ed.) Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History 1–16 (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2000).

Gustafson, M. The Tattoo in the Later Roman Empire and Beyond. In Caplan, J. (ed.) Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History 17–31 (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2000).

Scheinfeld, N. Tattoos and religion. Clin. Dermatol. 25, 362–366 (2007).

Guerzoni, G. Tatuajes devocionales en la Italia de la Edad Moderna. Espacio Tiempo y Forma Ser. VII Hist. Arte 6, 119–136 (2018).

Béreiziat-Lang, S. & Ott, M.R. From tattoo to stigma: Writing on body and skin. In Writing Beyond Pen and Parchment 193–208 (2019).

Lewy, M. Jerusalem Under the Skin: The History of Jerusalem Pilgrimage Tattoos. In: Dauge-Roth, K. & Koslofsky, C. (eds) Stigma: Marking Skin in the Early Modern World 85–123 (Penn State University Press, University Park, 2023).

Lacassagne, A. Les tatouages: étude anthropologique et médico-légale (Baillière, Paris, 1881). https://doi.org/10.3406/linly.1881.11456.

Bonney, H., Bekvalac, J. & Phillips, C. Human Remains in Museum Collections in the United Kingdom. In: Squires, K., Errickson, D. & Márquez-Grant, N. (eds) Ethical Approaches to Human Remains 211–237 (Springer, Cham, 2019).

Licata, M. et al. Study, conservation and exhibition of human remains: the need of a bioethical perspective. Acta Biomed 91, e2020110 (2020).

Ahrndt, W. et al. Recommendations for the care of human remains in museums and collections (Deutscher Museumsbund, Berlin, 2013).

Andrieux, J.-Y. & Frangne, P.H. Patrimoine, sources et paradoxes de l’identité (Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2011).

Lodder, M. A medium, not a phenomenon: an argument for an art-historical approach to Western tattooing. In: Martell, J. & Larsen, E. (eds) Tattooed Bodies. Palgrave Studies in Fashion and the Body (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86566-5_2.

Angel, G. Recovering the Nineteenth-Century European Tattoo: Collections, Contexts, and Techniques. in Ancient Ink: The Archaeology of Tattooing 107–129 (Krutak, L. & Deter-Wolf, A. eds) (2018).

Hardy, D.E. Life and Death tattoos. Tattootime 4 (Hardy Marks, 1989).

Whitlock, F. The Beasts of Buchenwald, Karl and Ilse Koch, Human skin lampshades, and the war-crimes trial of the century (Cable Publishing, Brule, Wisconsin, 2011).

Fisher, J. A. Tattooing the body, marking culture. Body Soc 8, 91–107 (2002).

Caplan, J. “National Tattooing”: Traditions of Tattooing in Nineteenth-Century Europe. in Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History (ed. Caplan, J.) (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2000).

Leschiutta, P. Le pergamene viventi. Interpretazioni del tatuaggio nell’antropologia positiva italiana. La Ricerca Folklorica 129–138 (1993).

Petrizzo, A. Pelli criminali? La scuola lombrosiana e il corpo tatuato a fine Ottocento. Contemporanea 19, 43–68 (2016).

Lombroso, C. L’uomo delinquente studiato in rapporto alla antropologia, alla medicina legale ed alle discipline carcerarie (Hoepli, Milano, 1876).

Bride, S. The Vagabond Venus: Cesare Lombroso Colonizes Tattoos. In: Mounsey, C. & Booth, S. (eds) Bodies of Information: Reading the Variable Body from Roman Britain to Hip Hop 191–205 (Routledge, New York, 2019).

Ferguson, C. Societal Deviance or an Expression of Identity? The Tattoo in 19th-Century Europe [dissertation]. (University of Reading, Reading, 2020).

Campbell, A. 18 Preserved Prison Tattoos That Are Still Attached To Skin. HuffPost News https://www.huffpost.com/entry/preserved-prison-tattoos-poland_n_5222032 (2014) (accessed 26 Apr. 2025).

le Goarant de Tromelin. Le tatouage: considerations psychologiques et medico legales (Bosc frères M. et L. Riou, Lyon, 1933).

Tatuaggio. Storie dal Mediterraneo. Exhibition catalogue (Milan, 28 March–28 July 2024) (2024).

Laurencich-Minelli, L. Museography and ethnographical collections in Bologna during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. in The Origin of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Europe (eds. Impey, O. & MacGregor, A.) 19–27 (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1985).

Olmi, G. Science, honour, metaphor: Italian cabinets of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. in The Origin of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Europe (eds. Impey, O. & MacGregor, A.) 1–17 (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1985).

Quaranta, M. et al. An early scientific report on acromegaly: solving an intriguing endocrinological (c)old case?. Hormones 19, 611–618 (2020).

Angel, G. The Tattoo Collectors: Inscribing Criminality in Nineteenth-Century France. Bildwelten Des Wissens 9, 29–38 (2012).

Alker, Z. & Shoemaker, R. Convicts and the Cultural Significance of Tattooing in Nineteenth-Century Britain. J. Br. Stud. 61, 835–862 (2022).

Manzoli, L., Ratti, S. & Cocco, L. Anatomy and Ceroplastic School in Bologna: a heritage with unexpected perspective. Ital. J. Anat. Embryol. 126, 93–101 (2022).

Marvi, M. V. et al. The anatomical wax collection at the University of Bologna: bridging the gap between tradition and scientific innovation. Ital. J. Anat. Embryol. 128, 9–16 (2024).

Pigorini-Beri, C. Costumi e superstizioni dell’Appennino marchigiano (S. Lapi, 1889).

Bagattini, A. La fede sulla pelle. I tatuaggi di Loreto tra storia, teologia ed iconografia. Tesi di Licenza in Scienze Religiose, Istituto superiore di scienze religiose di Milano (2024).

Angel, G. In the Skin: An Ethnographic-Historical Approach to a Museum Collection of Preserved Tattoos. PhD Thesis, University College London (2013).

Stieda, L. Etwas über Tätowierung. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 61, 893–896 (1911).

Vélez, K. The Miraculous Flying House of Loreto: Spreading Catholicism in the Early Modern World (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2019). https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv301ggq.

Cattaneo, M. Storie incise sulla pelle: i tatuaggi lauretani (secc. XVI–XXI). In Partenope degli spiriti. Fantasmi, fluidi e (finte) resurrezioni nel Regno di Napoli di età moderna 89–109 (Viella, 2024).

Morello, G. The case for tattoos as religious practices. From footnote to survey indicator. Crit. Res. Relig. 12, https://doi.org/10.1177/20503032241254368 (2024).

Stoppani, A. Il bel paese (Edizioni Theoria, 2019).

De Blasio, A. Il tatuaggio (Ed. Priore, 1906).

De Laurentiis, Marchiati. Breve storia del tatuaggio in Italia (Momo edizioni, 2021).

Birarda, G. et al. Chemical analyses at micro and nano scale at SISSI-Bio beamline at Elettra-Sincrotrone Trieste. Proc. SPIE 11957, 1195707 (2022).

Ricciardi, P., Legrand, S., Bertolotti, G. & Janssens, K. Macro X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) scanning of illuminated manuscript fragments: potentialities and challenges. Microchem. J. 124, 785–791 (2016).

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Nuclear Science and Instrumentation Laboratory (NSIL). Online resource. https://www.iaea.org/about/organizational-structure/department-of-nuclear-sciences-and-applications/division-of-physical-and-chemical-sciences/nuclear-science-and-instrumentation-laboratory-nsil (accessed 2025).

Uhlir, K. et al. Applications of a new portable (micro) XRF instrument having low-Z elements determination capability in the field of works of art. X-Ray Spectrom 37, 450–457 (2008).

Ketek. AXAS (Analog X-ray Acquisition System). Tech. Rep. (FAST ComTec, 2007); https://www.fastcomtec.com/fwww/datashee/det/axas.pdf.

BrightSpec. Topaz-X Compact Digital MCA for ED XRF Specification. Tech. Rep. (BrightSpec, 2015); https://www.brightspec.be/brightspec/downloads/Topaz-X_Spec_V1.1.pdf.

García Ordóñez, L.G. et al. MA-XRF Scanner: Implementation of Elemental Maps Reconstruction Algorithm Based on Single Photon Detection for Cultural Heritage Studies. X-Ray Spectrom. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1002/xrs.3496.

BrightSpec. bAxil Software Package Specification. Manual (BrightSpec, 2015); http://www.brightspec.be.

Stani, C. et al. FTIR investigation of the secondary structure of type I collagen: New insight into the amide III band. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 229, 118006 (2020).

Cheheltani, R. et al. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic imaging of cardiac tissue to detect collagen deposition after myocardial infarction. J. Biomed. Opt. 17, 056014 (2012).

Van der Rest, M. & Garrone, R. Collagen family of proteins. FASEB J. 5, 2814–2823 (1991).

Bicchieri, M. et al. Non-destructive spectroscopic characterization of parchment documents. Vib. Spectrosc. 55, 267–272 (2011).

Hermans, J. et al. The Identification of Multiple Crystalline Zinc Soap Structures Using Infrared Spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 74, https://doi.org/10.1177/0003702820935183 (2020).

McLean, D. Protecting wood and killing germs: ‘Burnett’s Liquid’ and the origins of the preservative and disinfectant industries in early Victorian Britain. Bus. Hist. 52, 285–305 (2010).

Goodarzi, N. et al. Zinc Chloride, A New Material for Embalming and Preservation of the Anatomical Specimens. ASJ 15, 25–30 (2018).

Ellerbrock, R. H., Stein, M. & Shaller, J. Comparing silicon mineral species of different crystallinity using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Front. Environ. Chem. 5, 1462678 (2024).

Christiansen, T. et al. Chemical characterization of black and red inks inscribed on ancient Egyptian papyri: the Tebtunis temple library. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 14, 208–219 (2017).

Blando, J. B. & Guigni, V. A. Potential chemical risks from tattoos and their relevance to military health policy in the United States. J. Public Health Policy 44, 242–254 (2023).

Sibilia, M. et al. A multidisciplinary study unveils the nature of a Roman ink of the I century AD. Sci. Rep. 11, 7231 (2021).

Kaye, T.G., Bak, J., Marcelo, H.W. & Pittman, M. Hidden artistic complexity of Peru’s Chancay culture discovered in tattoos by laser-stimulated fluorescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 122, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2421517122 (2025).

Pabst, M. A. et al. The tattoos of the Tyrolean Iceman: a light microscopical, ultrastructural and element analytical study. J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 2335–2341 (2009).

Moseman, A. P. et al. What’s in My Ink: An Analysis of Commercial Tattoo Ink on the US Market. Anal. Chem. 96, 3906–3913 (2024).

Lodén, M. & Wessman, W. The influence of a cream containing 20% glycerin and its vehicle on skin barrier properties. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 23, 115–119 (2001).

Blanco, M. et al. Study of the Lipase-Catalyzed Esterification of Stearic Acid by Glycerol Using In-Line Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 48, https://doi.org/10.1021/ie900406x (2009).

Vagnini, M. et al. Non-invasive detection of lead carboxylates in oil paintings by in situ infrared spectroscopy: How far can we go?. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 301, 122962 (2023).

Cortea, I. M. et al. Assessment of easily accessible spectroscopic techniques coupled with multivariate analysis for the qualitative characterization and differentiation of earth pigments of various provenance. Minerals 12, 755 (2022).

Pinzari, F. et al. Biodegradation of inorganic components in paper documents: formation of calcium oxalate crystals as a consequence of Aspergillus terreus Thom growth. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 64, 499–505 (2010).

Mazzarino, S. Humidification and tensioning of parchment documents: an evaluation of different techniques. in Parchment and Leather Heritage (Nikolaus Copernicus University, 2012).

Daudin-Schotte, M., Van Keulen, H. & Van Den Berg, K. J. Analisi e applicazione di materiali per la pulitura a secco di superfici dipinte non verniciate. Quaderni del CESMAR7 12 (Il Prato, Padova, 2014).

Giuffredi, A., Del Bianco, A. & Di Foggia, M. La rimozione dei depositi superficiali del gesso mediante idrogel viscoelastici di alcol polivinilico e borace. in XVII Congresso Nazionale IGIIC - Lo Stato dell’Arte 17 (Nardini Editore, Firenze, 2019).

Mangiapane, G. et al. Rare tattoos shape and composition on a South American mummy. J. Cult. Herit. 73, 561–570 (2025).

Smith, M. J., Starkie, A., Slater, R. & Manley, H. A life less ordinary: analysis of the uniquely preserved tattooed dermal remains of an individual from 19th century France. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 13, 55 (2021).

Pabst, M. A. et al. Different staining substances were used in decorative and therapeutic tattoos in a 1000-year-old Peruvian mummy. J. Archaeol. Sci. 37, 3256–3262 (2010).

Alvrus, A., Wright, D. & Merbs, C. F. Examination of tattoos on mummified tissue using infra-red reflectography. J. Archaeol. Sci. 28, 395–400 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Roberto Balzani, President of the SMA- Sistema Museale di Ateneo dell’Università di Bologna till April 2024, and Professor Giuliana Benvenuti, current President; Dr. Francesca Tomba and all the officials of the Superintendency for Fine Arts and Landscape of Bologna, to allow the analytical investigation on the tattooed skin fragments. The authors acknowledge Dr. Andrea Bagattini for making available his thesis on the Loreto tattoo practice and for the willingness to help and discuss. The authors would like to thank Jonatal Carducci and Raddouk, currently the last tattoo artists carrying on this tradition, for their help and images of their instruments. The authors wish to thank Dr. Luisa Gnecchi Ruscone and Dr. Jurate Francesca Piacenti, organizers of TATTOO - Tales from the Mediterranean public exhibition at the Museo delle Culture (MUDEC) in Milan for their support in identifying some sources of study. Thanks to Dr. Francesco Aquilanti and Dr. Francesca Uccella of Museo delle Civiltà (MUCIV) in Rome which preserves the testimonies of traditional Italian culture, from the XVI to the XX century, including numerous original wooden matrices used for Loreto tattooes and for contributing to the supplementary information_1.We would like to acknowledge the CERIC-ERIC Consortium for the access to Elettra Sincrotrone Trieste via fast-track beamtime n. 20237252, and for the financial support. Moreover, we thank the CH-ERIC Project, CERIC-ERIC for Cultural Heritage Research, for the technical and scientific support. Finally, the authors wish to thank the Nuclear Science and Instrumentation Laboratory, part of the Department of Nuclear Sciences and Applications of the IAEA, and its Head, Dr. Kalliopi Kanaki, for their support in the development of the MA-XRF scanner. The research presented in this work does not represent the institutional activities or scientific scope of the Italian Space Agency (ASI). The affiliation is provided solely for identification purposes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing of part of the Introduction and Methods paragraphs, translation and review of supplementary information_1, review of the entire manuscript. A.C.: Resources, Formal analysis. M.L.C.: Resources, Formal analysis. L.G.G.O.: Experimental Measurements, Formal analysis, Writing part of Methods and Results paragraphs and supplementary information_2. C.D.R.: Resources, Writing part of the Methods and Discussion paragraph. E.L.: review and editing final manuscript. C.N.: Resources, Writing part of the introduction paragraph. E.O.: Writing part of the introduction paragraph. S.R.: Supervision, Funding acquisition. C.S.: Experimental Measurements, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing part of Methods and Results paragraphs and supplementary information_2, review and editing final manuscript. L.V.: Resources, Formal analysis. M.V.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Supervision, Writing and review of the Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion paragraphs, translation and review of supplementary information_1, review and editing final manuscript. C.L.Z.: Resources, Writing part of the Methods and Discussion paragraph. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions