Abstract

A one-hundred-year-old hypothesis regarding the transfer of the brick building technology from Lombardy to Denmark by the mid-1100’s has been tested. Two churches in Denmark and two in Italy have been re-examined by their architectural traits. 305 brick samples have been analysed by TL-dating, magnetic susceptibility, TL-sensitivity, XRD, FTIR, XRF, LA-ICP-MS, and spectrophotometric colour measurements. Mortar samples have been analysed by Py-GC-MS and thin section examination allowed a comparison of the manufacturing technologies. The scarce historical references on the transfer theory have been re-examined in perspective of the archaeometric evidence. Although not decisive by themselves one by one, collectively our results point to a rejection of the direct transfer hypothesis. Considering the results of the present investigation it seems more likely that the diffusion of knowledge about brick building technology followed a more convoluted path from the Cistercian communities in Lombardy towards Denmark with stops underway, likely in Germany.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When the art of burning clay into bricks was introduced in Denmark in the middle of the 1100’s, it marked a breakthrough in the domestic building culture. At a time when all Danish buildings, regardless of function and status, were made of wood or natural stone—brown or whitewashed - churches and castles now rose with bright-red facades that must have appeared both alien and overwhelming at the same time. In the early days, there was great prestige associated with building with bricks, which is emphasized by a lead-plate in the grave of King Valdemar the Great (1157-1182) with a Latin inscription stating that he had built with ‘baked stone’ (ex lateribus coctis) (Worsaae and Herbst 18581, p. 58–592,3;). Around 1160 Valdemar the Great initiated the erection of a large Benedictine monastery church in Ringsted, which until the beginning of the 14th century became the preferred burial church for the royal family (Fig. 1a). In 1177, the church is referred to as being ‘under construction’, and in the 15th Century, the king is referred to as the ‘expander of the church’. This designation is quite accurate, as the brick church replaced an older church on the same site (Danmarks Kirker Sorø Amt 1936–19384, p. 1125;).

During his reign, Valdemar the Great also began an expansion of the century-old defensive wall ‘Danevirke’, which stretched across the root of Jutland from Hedeby towards the west, as a several kilometres long, south-facing defensive brick wall6. Measured in scope, King Valdemar’s defensive wall can be considered one of the largest single building projects in the Danish Middle Ages – not just in brick, but in general.

Almost simultaneously the powerful bishop of Roskilde Diocese, later Archbishop of Lund, Absalon (1158–1192/1178–1201) began the erection of a similar burial church for his influential Hvide-family, in Sorø just 15 kilometres west of Ringsted (Fig. 1b). Construction began here shortly after 1161, when Absalon founded a Cistercian monastery on the site (Danmarks Kirker Sorø Amt 1936–19384, p. 17-182). These new constructions, the monastery churches in Ringsted and Sorø, as well as the new part of the Danevirke defence wall towards Germany and the first use of bricks in the city of Ribe are assumed to belong to the first brick buildings in Denmark, where burnt clay bricks are still among the most important building materials today, nearly 900 years after.

Like Valdemars Wall, the two monastic churches were also extensive construction tasks. Both churches are c. 70 m long and laid out as a three-nave basilica with a chancel in extension of the central nave and projecting transepts, each with two small east-facing chapels. The plan of the two churches, however, are different in the way that the high choir and the four chapels of the transepts are finished by an apse in Ringsted, which gives the eastern part of the church a spectacular appearance (see Fig. 1b). In Sorø, the high choir and the chapels of the transept are simply rectangular, as the plan here is laid out in strict accordance with the usual plan of churches in the Cistercian order. Recognizable in Cistercian monasteries across Europe, this design, referred to as Fontenay type, was originally based on the order’s important monastery at Citeaux, some 25 km south of Dijon, which was destroyed in the turbulent years following the French Revolution of 17897,8,9,10. It is therefore unlikely that the Fontenay type layout of all four churches investigated presently is enough to argue for a common architectural origin.

The exact datings of the earliest Danish brick buildings are still discussed. The beginning of the erection of the Romanesque churches in Ringsted and Sorø is approximately 1160, while their completion is more difficult to specify, as written sources can only vaguely be linked to Denmark’s medieval building culture. From recent research into the building history of the churches and from the few written sources, it can be argued that Sorø was completed at least when the builder, Absalon, was buried in front of the main altar in 12012. In Ringsted, the monastery church was probably only completed by the beginning of the 13th century when King Valdemar Sejr (1202–1241) reigned5. Correspondingly, the chronicler Svend Aggesen attributes the completion of the Valdemars Wall to the king’s successor, King Knud 6 (1182–1202)3.

While Valdemar’s Wall at Danevirke fell into disrepair early in the Middle Ages, the two mid-Zealand monastery churches are well preserved to this day, and due to their detailed architecture, they have early on been the starting point for the rather widespread view that the early Danish brick architecture came to the country directly from Lombardy. Here, by the end of the 11th Century, a cultivated brick culture flourished, which in the following century found its way to several church constructions around Milan in the Po Valley11,12,13,14,15,16. In Pavia, bricks were produced early on, which were used in facades with varying round-arched friezes. Distinguished and well-preserved representatives of the period’s early brick art can also be seen in the large, well-preserved Cistercian churches in Chiaravalle and Abbadia Ceretto near Lodi southeast of Milan, which have been dated roughly to the second part of the 12th century (Fig. 1c–d)4,11,12,14,17. Just as in Sorø, these two large monastic churches are laid out using the characteristic ground-plan of the Cistercian order with a basilica nave, transepts with rectangular chapels and a rectangular high choir.

The close connection between the early Lombard and Danish brick architecture was noticed at the beginning of the 20th Century by the Danish restoration architect Mogens Clemmensen (1885–1943), who in 1920 and 1923 undertook expeditions to Northern Italy, where he described and registered several Romanesque brick churches. Upon his return, Clemmensen shared his impressions in the long article “The relationship between Lombard and Danish brick architecture”, which for a century has been among the most important papers on Denmark’s earliest brick architecture and the international relations of construction3,5,13,14.

Since the early studies of Mogens Clemmensen4,13, the hypothesis has been that the brick architecture was introduced in Denmark during the second half of the 12th Century with direct inspiration from Lombardy. This hypothesis has been discussed by the Danish art historian Hugo Johannsen14 and the German building archaeologist Jens Christian Holst18 and by recent archaeological publications19 bringing new information through written sources and the study of building constructions. The investigation undertaken by Perlich20 in Northern Europe led her to believe that the use of brick technology was not coming from a single site or even a specific area; more likely the development of brick architecture was inspired by the Italians and took place simultaneously in Denmark and the German-Roman Empire. A completely similar and presumably simultaneous development took place in the northern part of Germany and on the south side of the Baltic Sea21, most prominently in Lübeck, where brick construction was introduced approximately in 1180 as a renewal of the existing half-basement wooden construction22. On the other hand, no similar contemporaneous buildings are seen in Switzerland nor in the rest of Germany. Consequently, Denmark and Northern Germany seemingly developed completely in parallel despite their different political and dynastic circumstances.

Three main hypotheses are generally used to explain the spreading of the brick architecture in Northern Europe: (1) the growing influence of the monastic orders such as the Cistercians has been the preferred explanation to the spreading of brick architecture for a long time. The international connections of the Cistercians and their capacity to adapt quickly partly explained their rapid growth in Europe during the 12th and 13th centuries23; (2) the crucial role of the monarchs and the local elites is an opinion defended by Perlich20. This idea is supported by the strong military influence of the emperor of the German-Roman Empire, Frederic Barbarossa (1152–1190), in Northern Italy and the rise of brick architecture in Northern Germany in the second half of the 12th Century - notably the cathedrals of Brandenburg and Ratzeburg built between the end of the 12th Century and the beginning of the 13th Century; (3) the rise of the international commerce through the new trading routes coupled to a growing urbanization in Western Europe is another explanation defended by researchers such as Debonne24 to explain the diffusion of brick architecture in Europe.

However, at present no single ready-made factor seems to be able to confirm the century-old theory by Clemmensen13 suggesting a direct communication between Lombardy and Denmark3. Working in the same direction as Perlich, other studies published in Technik des Backsteinbaus20, have come to indicate that the stylistic studies and historical sources were insufficient to provide a good understanding and a reliable chronology of the spread of brick architecture in Europe. The recent studies performed by the research groups of archaeometry from the Universities of Bordeaux and Durham about the chronology of brick buildings match the same conclusions about the need of further archaeometric analyses. Using thermoluminescence dating, these researchers have tried to improve and correct previous chronologies of early medieval churches in France and in England25. In the present work, we will fill a similar gap in knowledge but relating to a much longer and much more stunning transmission allegedly taking place from Italy all the way to Denmark, be it a direct or indirect connection, a continuous or discontinuous one.

In the present work, it will be attempted to bring the direct-technology-transfer hypothesis to the test. This will be done using a suite of archaeometric techniques: TL-dating of the bricks, provenancing the clay resource and the mortars, and by comparing building archaeological traits in four churches, Ringsted, Sorø, Chiaravalle, and Cerreto. The TL-datings are intended to reveal the chronology or erection of the churches, and most likely place the two Italian churches before the Danish ones, provided the direct transfer hypothesis is correct.

From the brick samples taken, analyses of the mineralogy and provenance by magnetic susceptibility, FTIR, and XRD have been made, which have the potential to reveal construction phases in the individual church buildings and thereby perhaps clarify the organization of the construction. Furthermore, colour analyses of intact facades and rear walls has been carried out, with a view to demonstrate the most notable architectural expression of the buildings – their vivid colours. The colour measurements are therefore intended to show possible similarities in the architectural thinking of the building masters. Finally, a few mortar samples from each of the four churches have been analysed to quantify the binder/aggregate ratio (B/A) and to look for possible traits in the production technologies that might allow a comparison of the four churches. These include both the aggregate mineralogy of the mortars as well as the organic constituents of the mortars.

These archaeometric data will be compared with new architectural and building archaeological observations and compared to the scarce literature references in order to bring Clemmensen’s hypothesis regarding the direct transfer of brick building technology between Lombardy and Denmark to the test.

Methods

Selection and description of the churches

The church of the abbey of Chiaravalle Milanese has been chosen because it is allegedly the first Cistercian church in Italy and one of the two important starting points of the Cistercian order spreading into Lombardy26,27. This building is typical of the Romanesque Cistercian architecture from the 12th Century, built according to the Latin cross plan of the French Clairvaux Abbey, the so called Fontenay plan. The original building material is red bricks which is also used in later Gothic additions12. The abbatial church of Santo Pedro e Santo Paolo of Cerreto near Lodi was allegedly built onto a pre-existing Benedictine monastery by the first abbot of Chiaravalle. The church plan is generally quite similar to the plan in Chiaravalle, and according to De Longhi28 just as the two churches are roughly the same age, they also share an architectural expression. Both churches have been discussed by Clemmensen and Johannsen. The Benedictine Abbey Sankt Bendts in Ringsted and the Cistercian Abbey Church in Sorø have been chosen because according to stylistic and historic studies, both were built in the second part of the 12th Century4,5. Thus, they are assumed to be among the oldest brick buildings in Denmark and, on a wider scale, also belong to the oldest brick churches in Northern Europe. Beyond the use of brick material, the presence of architectural details such as miniature column friezes betray a potential Lombardian influence on these Danish churches4.

Sampling

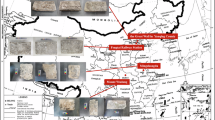

305 brick samples were procured on site with hammer and chisel. The sampling sites are indicated in Fig. 2 and listed in Table 1. The abbreviations S (Sorø), R (Ringsted), C (Chiaravalle, and L (Abbadia Cerreto a Lodi) are used in the remained of the paper. Each site and each brick sampled were recorded. Generally, ten samples were procured from the same wall segment allowing for making robust averages of the radiation coming from U, Th, and K from the environment of the individual bricks, and of course it also allows a better uncertainty to be determined for the TL-ages when averaged. In one case only five samples were taken (C190-C194), and in one case it was later realized that the ten samples constituted two sperate groups (L215-L218 and L219-L224).

Plan drawings of the four churches. a Sorø; b Ringsted; c Chiaravalle; d Abbadia di Cerreto a Lodi. Sampling sites are marked with numbers referred to in Table 1.

A total of 30 mortar samples were procured from the four churches (see list in Table 2). In Sorø and Ringsted the strategy for selecting the sites for sampling mortars were places where joints were wide and overflowing with original mortar. Except for one sample (KLR-13392), these places were not coinciding with the places where bricks were sampled. In Chiaravalle and Cerreto a Lodi the strategy had to be different, because places with excess mortar were not to be found. Instead, the mortar samples in Chiaravalle and Cerreto were taken in the thin joints close to places where bricks were sampled.

Thermoluminescence dating (TL)

The entire set of brick samples was dated by thermoluminescence (TL)29,30,31,32,33. A fraction of each sample was crushed and sieved in a dark room and 40 mg of the granulometric fraction between 100 and 300 μm was taken out for TL-measurement.

The TL measurements were performed on a DA-12 TL-reader from Risø National Laboratory using the Single Aliquot Regeneration method adapted from Hong et al.34 taking the average of four subsamples. To calculate the age, it is needed to determine the doses received from the environment. These are assumed to originate from three sources: (1) the internal source which consists of the four radioactive isotopes present in the sample: 40K, 235U, 238U, and 232Th; (2) the external source from the same four isotopes in the surrounding wall segment; and (3) the cosmic flux.

Another part of each sample was cut on a low velocity saw, embedded in Epoxy resin, and polished to a finish of 1 μm diamond paste. The radioactive isotopes from the sample were measured using LA-ICP-MS (for K, Th, and U), see below. The cosmic flux was assumed to be 180 ± 30 μGy y−1. The calculation was performed using the “Luminescence” package on R software35. The procedure required adjustment from factors affecting the dose rates: (1) the self-shielding was calculated with a measured average density of 1.8 ± 0.3 g cm−3, (2) the grain diameter after sieving was assumed to be 200 ± 100 µm, (3) the alpha efficiency was assumed to be 0.08 ± 0.02 according to Olley et al.36, and (4) the water content, which was determined to be 1 wt%. No HF etching was applied; thus, the alpha particle dose was included in the annual dose rate calculation37. These parameters were computed and processed through the AGE software by Grün38 to provide the dose rates and the TL-age.

Laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS)

Uranium, Th, and K were determined by Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS)39,40,41,42,43. The ablation was performed with a CETAC LXS-213 G2 equipped with a NdYAG laser operating at the fifth harmonic at a wavelength of 213 nm. A 25 µm circular aperture was used. The shot frequency was 20 Hz. A line scan was performed with a scan speed of 20 µm s−1 and was ca. 6 mm long. The helium flow was 600 mL m−1. The laser operations were controlled by the DigiLaz G2 software provided by CETAC. The inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analyses were carried out using a Bruker Aurora M90 equipped with a frequency matching RF-generator. The basic parameters were as follows: radiofrequency power 1.30 kW; plasma argon gas flow rate 16.5 L min−1; auxiliary gas flow rate 1.65 L min−1; sheath gas flow rate 0.18 L min−1. The following isotopes were measured without skimmer gas: 39K, 232Th, and 238U. No interference corrections were applied to the selected isotopes as recommended by the Bruker software. The analysis mode used was peak hopping with 3 points per peak, and the dwell time was 4 ms on 39K, 50 ms on 232Th, and 100 ms on 238U. The quantification was performed with a method similar to Gratuze44. Three standard reference materials were run before and after each batch: NIST610 and NIST612 glass standards and NIST2711 Montana soil II in pressed pellets. The performance was monitored on an in-house standard of ceramic material sample. The NIST2711 and the in-house ceramic standard had quite similar matrices to the samples analysed. Instrument drift was monitored and if it occurred, the measurement was discarded and repeated. A relative error of ca. 10% is assumed from these measurements, mainly due to the mineral heterogeneity of the sample.

Magnetic susceptibility and TL-sensitivity

Magnetic susceptibility was measured using ca. 1 g samples with a KLY-2 susceptibility-metre capable of reaching ca. 1 × 10−6 Sl-units. The thermoluminescence (TL) sensitivity was measured on four 10 mg aliquots of the crushed and sieved grain size fraction 100–300 µm. For the TL-measurements a TL/OSL-system TL-DA-12 manufactured at Risø National Laboratory, Denmark is used. The palaeosignals are erased by heating the samples to 400 °C. Subsequently, the samples were irradiated for 60 s under a 0.8 GBq 90Sr-source. The samples were then annealed for 30 s at 200 °C, and the TL-signal measured from 202 to 235 °C and integrated in order to yield the TL-sensitivity. Drift in photodetector high tension, optical transmission and other system parameters are monitored by measuring four aliquots of a standard sample daily. The method and its application are described elsewhere45.

Colour measurements

The colour measurements were made using a Minolta CM-23d spectrophotometer yielding the colour coordinates (L*, a*, b*) as recommended in 1976 by the Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage (CIE)46,47,48. The following experimental conditions were used: Illuminant D65; observer 10°; specular component: excluded. The rationale for the (L*, a*, b*) system is to approximate the human perception of differences in colours with proportional distances in this colour space. From the (L*, a*, b*) was calculated the chromaticity, c*, as the square root of a* squared plus b* squared. The photo spectrometer also downloaded the spectral components in steps of 10 nm from 400 to 700 nm. Two parameters were calculated from the spectral components, S(400–450) and S(650–700), which are the averages of the spectral content from 400 to 450 nm and 650 to 700 nm, respectively.

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The structural mineralogical content was established by XRD49,50,51. The analysis was performed using a PANalytical X’Pert PRO MPD system (PW3050/60) with Cu Kα radiation as the source (λ = 1.54 Å) and a PIXcel3D detector. The X-ray generator was set to an acceleration voltage of 45 kV and a filament emission current to 40 mA. The divergence slit was fixed at 0.43°. The capillary sample holder was mounted in an HTK 1200 N Capillary Extension (Anton Paar) with a ceramic anti-scatter shield. The sample was scanned while spinning between 5° (2θ) and 90° (2θ) using a step size of 0.013° (2θ) with a count time of 260 s. Data were collected using X’Pert Data Collector. The qualitative analysis was performed using Highscore Plus software. The ICDD PDF-2 database and the updated COD database have been used to interpret the results. The semi-quantitative results were obtained using Rietveld refinement with the software PROFEX 5.4.1 and the BGMN database52. As no internal standards were used, the reference structure “silicabgm” was used for accounting the presence of the amorphous phase.

Micro X-ray fluorescence analysis (µ-XRF)

µ-XRF analyses were carried out using an ARTAX-800 manufactured by Bruker-Nano53,54,55,56, which is a laboratory µXRF model. The beam size was 60 μm. A high tension of 50 kV and a current of 600 μA were used. The measurement atmosphere was ambient air. The measurements were conducted on pellets made from homogenized sieved fraction below 100 µm applying a pressure of 120 kN, thus avoiding any surface contamination that may have been present on the surface of the bricks. Absolute calibration of the concentrations was done using the DCCR-method (Direct Calibration from Count Rates) provided by the Bruker software using a pressed pellet of the standard reference material SRM NIST-2711.

FTIR

A Fourier Transform Infrared instrument from Agilent Technology, Cary 630, was used equipped with a diamond crystal ATR accessory49,50,57. In this instrument, spectra were collected from 32 co-added scans in the spectral range 4000–650 cm-1, with a resolution of 8 cm−1 and the background was subtracted. No further corrections were applied to the data. Data were processed with Spectragryph software58 (v.1.2.14).

Analytical pyrolysis coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Py-GC-MS)

Py-GC-MS analysis were performed using a multi-shot pyrolyzer EGA/PY-3030D (Frontier Lab, Japan) coupled with an 8890 gas-chromatograph, combined with a 5977B mass selective single quadrupole mass spectrometer detector (Agilent Technologies, USA)59,60,61,62. The deactivated steel cups used for the pyrolysis experiments were cleaned before use with a butane blow torch at 1400 °C. The Py-GC-MS system was cleaned between analyses by performing two subsequent fast runs. The first run was performed using a clean empty cup containing 2 µL of the silylating agent hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) to remove any polar, low-volatile contaminants from the GC-MS system, followed by a second analysis performed on the same empty cup without HMDS to remove the excess of derivatizing agent from the system. For both the runs the pyrolysis furnace was set at 550 °C. The Py-GC interface was set at 280 °C. The GC injector was operated in split mode at 280 °C, with a 20:1 ratio. Separation of the pyrolysis products was achieved with an HP-5MS capillary column (30 m x 0.25 mm, film thickness 0.25 μm, Agilent Technologies, USA). The GC oven temperature programme was as follows: 40 °C for, 20 °C/min to 315 °C kept for 10. The observed m/z range of the mass spectrometer was 35–700.

Agilent Qualitative Analysis 10.0 software (Agilent Technologies, USA) was used for data analysis and the peak assignment was based on a comparison with libraries of mass spectra (NIST 20) and the literature data63. The detection limit was in the microgram range.

Optical polarized light microscope (PLM)

Thin sections (30 µm thickness) of the mortars were examined via polarized optical microscopy using an AxioScope A1 microscope at various magnifications, equipped with video camera, 5 Megapixel resolution and AxioVision image analysis software. It allows the identification of the most important aspects of binders, including their texture and microstructure, as well as possible recrystallizations and reactions with the aggregates, e.g., the presence of neoformation phases. Regarding the aggregates, this provides an initial evaluation of their types, average grain size, grain size distribution and shape, in addition to the binder/aggregate ratio (B/A) and macroporosity64. Image analyses software (Image J) was used to calculate morphometric data and B/A ratios.

Results

The TL-dates

As is to be expected, some parts of these four buildings have at times over the centuries been exposed to fire. Other parts may have been repaired or replaced years after the time of erection. For this reason, wall segments with visibly newer bricks have been avoided during the fieldwork for this study. The newer bricks can for instance be identified by the trained eye by a slicker surface, a slightly different brick format, or by the building archaeological context. This was the case for all four churches, but especially so for the two Danish churches, where we more or less exhausted the supply of new wall segments suited for further sampling in the Ringsted church. For instance, has the entire southern façade of the Ringsted St Bendts Church been rebuild following a fire in 1806 devastating the adjacent monastery and a large part of the city. The two Italian churches seem to have been exposed to fire or rebuilding to a lesser extent, although the action of both fire and rebuilding do occur. In Fig. 3 is shown the average TL-dates for each wall segment; the entire data set is given in Supplementary Data 1. The average TL-dates for the individual wall segments are listed in Table 3.

Average TL-dates for the 32 wall segments in the four churches investigated in this study shown on a time range from AD 600 to 1850. a The entire dating range; b the interval from AD 1050 to 1300. The average dates are indicated by red dashed lines with the average date and one standard deviation attached to each of them. Dates identified as outliers are marked by a green circle. These were omitted when taking the averages. In the three instances where a date was older than expected a corrected date was produced using an environmental radiation of 1/1 (4 π steradians) of the samples in the wall segment changes instead of ½ of the environmental radiation of the wall itself (a half-space of 2 π steradians). See text for explanation. These corrections are marked by blue arrows.

Eight of the 32 wall segments are interpreted to be affected by fire or constitute later repair phases and are marked with green circles in Fig. 3a. These outliers are identified by analytical criteria all being more than seven standard deviations younger than the calculated averages. From the data set without these outliers, shown in Fig. 3b, averages for the building phases are calculated and marked as dashed lines, and listed in Table 3 with 1 standard deviations.

Three wall segments out of a total of 32 appear older than expected, S31-S40 from Sorø, C304-C313 from Chiaravalle, and L219-L224 from Abbadia Cerreto near Lodi. These segments in Sorø and Cerreto are situated on interior walls on the attic facing inwards towards the centre of the churches. The too-old segment from Chiaravalle is situated on top of the vault in the southern transept. The only conceivable reason for these anomalously old wall segments, is a hypothesis that some sort of material, such as a pile of unused bricks or perhaps an epitaph, was for a prolonged period of time stored up against these wall segments. If we as a hypothesis - a qualified guess - assume that the said material consisted of bricks with a composition similar to the bricks of the wall under investigation, we have a situation where the radiation budget of the samples in the wall segment changes from ½ of the environmental radiation of the wall itself (a half-space of 2 π steradians) to a scenario where the environmental radiation is approximately 1/1 (4 π steradians). This corresponds approximately to a scenario where a sample now taken at the surface of the wall, were for a prolonged time in the past sitting inside a massive wall of bricks. Three of the recalculated dates using this increased environmental radiation are added as points to the diagram with the designation “1/1 Wall”. In the cases from Cerreto and Chiaravalle this correction brings the 1/1-Wall dates in line with the other dates from the erection of the church. In the third case, S31-S40 from Sorø, the correction is seemingly too large, resulting in a date of 1351 ± 16, and that date is consequently classified as an outlier (green circle around it in Fig. 3a). In this case, the date is not discarded due to having been exposed to fire or rebuilding, but rather to an obviously inaccurate correction for the assumed material stored in front of the bricks, or alternatively for a considerably smaller amount of time. The explanation could also have been that an epitaph with a U and Th inventory less than that of the bricks were stored in front of this wall segment.

When all the wall segments interpreted to be later repair work or affected by fire (the points with a green encirclement in Fig. 3a) are discarded from the calculation, the best estimate of the time of erection of the four churches, Sorø, Ringsted, Chiaravalle, and Cerreto can be calculated to be 1185 ± 17, 1181 ± 16, 1258 ± 10, and 1108 ± 18, respectively (uncertainties are one standard deviation). Within the calculated uncertainties, a hypothesis of similarity of the time of erection for the two Danish churches will be statistically accepted, whereas Chiaravalle is significantly younger, and Cerreto significantly older than the two Danish churches. The uncertainties of our averages of the TL-dates do not allow to estimate the time difference between the erection of the two Danish churches, or even which one was built first.

The meaning of the dates for the late-dating bricks

As mentioned above nine of the 32 wall segments analysed in the present study were interpreted as outliers when considering the time of erection of the churches. There was four such later dating wall segments in Ringsted, and one in each of Sorø, Chiaravalle, and Cerreto. The initial hypothesis is of course that these later dates are the results of fires taking place in the churches. For Sorø we have historical records of two known fires: 1247 and 1813, and the one wall segments with later dates are dated to 1306 ± 21. In this case, we have obviously not sampled bricks that were affected by the fire in 1247. The measured date of 1306 ± 21 could of course be the result of a fire not recorded in the historical sources. But alternatively, it could also be the result of an incomplete resetting of the TL-clocks in the fire of 1813. That is, a situation where the temperature at the site of the sampled bricks possibly did not reach a sufficiently high value to allow a full emptying of the electron traps. For Ringsted there are historical records of fires in 1241, 1300, and 1806. Here the four later dated wall segments dates to 1709 ± 10, 1793 ± 9, 1542 ± 13, and 1510 ± 19. Again, as in Sorø, we have obviously avoided bricks affected by the fires in 1241 and 1300, but the fire in 1806 may conceivably in a similar way be the cause of all the four observed later datings, namely if the resetting of the TL-clocks has been only partial.

As mentioned above, it was attempted to avoid bricks suspected to be affected by fire during the fieldwork of this project. In another case, the Danish UNESCO World Heritage Site of Roskilde Cathedral, it was directly attempted to sample wall segments suspected to be affected by fire, and here six out of six known fires were TL-dated accurately65.

Appearance and characterisation of bricks—a question of Geology versus Technology

The appearance of a brick is dependent on three factors, firstly on the clay used and secondly on the processes involved in the manufacture, i.e., the possible tempering of the clay with other materials, and finally the firing process66,67. Even if two batches of bricks are made from the same clay source and mixed and treated in the same way, they can still be fired at different firing conditions. The most important parameter in the firing process is the oxygen tension, which is controlled by the amount of air let into the oven. Of lesser importance is the maximum firing temperature obtained during the firing process68. The outcome two different firing conditions can result in different mechanical properties of the bricks, e.g., density, strength, and porosity, but most notably from an architectural point of view it can result in widely different colours, to which we shall return shortly69. In the present work, we have not included mechanical testing of density, strength, porosity, or permeability. The appearances of the bricks are, however, of major concern in this investigation, because in the end similarities or dissimilarities of the buildings’ visual appearances are parameters which could relate to the intentions of the building masters.

The colours of the bricks, here reported in the (L*, a*, b*) colour system made by the Commission on Illumination (CIE) in 197646,47,69 are dependent on both the firing technology and on the geological characteristics of the clay resource, the latter mainly the Fe and the CaCO3 content of the clay70,71,72. Iron is the main source of colours in bricks by the formation of Fe2O3 upon firing, while the carbonate content is decisive for whether the brick turns yellowish or reddish in hue depending on the whether the concentration of calcite is higher or lower than c. 24 wt%, respectively73,74.

Variations in the geological details of the clay resource - even if mainly invisible to the naked eye - can be used for other archaeometric purposes. Differences in the provenance of the clay resource can be ascertained by differences in main- and trace-element concentrations, magnetic susceptibility, TL-sensitivity, and mineralogy. Mapping the differences in clay resources can in some instances be used to distinguish the various building phases in a particular church from each other, and in this way help to disentangle which parts of the building were built with bricks originating from the same clay resource. Consequently, the detailed geological characteristics, although only occasionally directly visible, can be helpful revealing details of the building archaeology. Aspects of the mineralogy, for instance, the occurrence of neo-formation minerals, can be utilized as signs of the passing of a certain temperature during the firing process. For instance, can the minerals gehlenite (Ca2Al[AlSiO7]) and wollastonite (CaSiO3) be formed during the firing process75, while for instance calcite (CaCO3), siderite (FeCO3), and goethite (α-FeO(OH)) can be destroyed during the firing process depending on the maximum temperature obtained. Such observations can supplement the direct measurement of the maximum firing temperature by stepwise re-heating and measurement of the magnetic susceptibility76.

The clay resource—the Geological aspects

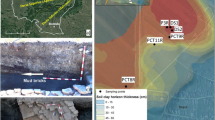

The two Danish churches are situated approximately 15 km apart by line-of-sight. It is therefore a pertinent question if these churches were built with bricks manufactured from the same clay resource, and a similar question can be raised for the two Italian churches lying ca. 20 km apart by line-of-sight. In Fig. 4 can be seen a comparison of the two material parameters: the magnetic susceptibility and the TL-sensitivity of the all the brick samples analysed from the two Danish churches (Fig. 4a) and the two Italian churches (Fig. 4b).

The bricks in one section of brickwork added on the western side of the front hall of Chiaravalle (C180-C189) are distinctly different from all the other bricks in this church by featuring a distinctly lower TL-sensitivity (see Fig. 4b). This section likely constitutes a repair phase or a new addition to the church from ca. 1540’s (see discussion of the TL-dates above). Apart from the bricks C180-C189, the bricks from the two Italian churches occupy the same area in the magnetic susceptibility versus TL-sensitivity plot and nothing speaks against a common clay resource, at least in this general term and what concerns these two material parameters. In opposition to this, the bricks from Sorø feature generally higher TL-sensitivity and slightly lower magnetic susceptibility than those from Ringsted (Fig. 4a). Therefore, the bricks from the two Danish churches are likely not generally derived from the same clay source.

Repair phases or original bricks affected by fire?

It could be speculated if the bricks dated to later periods were part of a repair phase using bricks fired at these later times. Alternatively, they could be original bricks from the time of the erection of the church—just later exposed to fire, at which time the TL-clocks were reset. To discriminate between these two scenarios, it can be investigated if the bricks dating from the time of the erection of the church is similar or dis-similar in clay provenance to the later dating wall segments. This was very clearly seen for the segment C180-C189 from Chiaravalle mentioned above, but what about the other less obvious cases?

The magnetic susceptibility and the TL-sensitivity is cross-plotted for the later dating wall segments and segments dated to the times of the erection for the cathedrals in Ringsted (Fig. 5a–b), Cerreto (Fig. 5c), and Sorø (Fig. 5d). In Fig. 5a is shown two sets of bricks from later dating wall segments R51-R70 (blue squares) and from the two later dated segments R71-R90 (orange triangles) for the cathedral in Ringsted. No clear differentiation can be seen in the diagram, which means that there is likely no difference in clay provenance between two sets of later dating wall segments. In Fig. 5b is shown data for the bricks from the six wall segments from Ringsted Cathedral dating to the time of the erection of the church R91-R303 (yellow squares) as well as all the bricks from the four later dating wall segments (green circles). Also, in this case, no systematic differences can be observed, indicating that the clay provenance is quite similar for the six wall segments dating to the time of erection of the church and the four later dating segments. It is therefore likely, that the four later dating wall segments are indeed the original bricks from the erection of the church, only exposed to higher temperatures later in time.

TL-sensitivity versus magnetic susceptibility of bricks dated to the time of erection and those dated later. a Ringsted cathedral, four wall segments dated later than the erection of the building, R51-R70 (blue squares) and R71-R90 (orange triangles); b Ringsted Cathedral, all samples dated to the assumed time of erection, R91-R303 (yellow squares), and all samples dated later, R51-R90 (green circles); c the same for Cerreto; d the same for Sorø.

For the church in Cerreto, Fig. 5c shows the bricks from wall segments dating to the time of the erection (yellow squares) and from the one segment, L205-L214, dating to a later time (green circles). In this case, however, the segment dating to a later time exhibit systematically lower TL-sensitivity values, and it is therefore likely in this case, that the brickwork here is a later addition or repair phase and not part of the original building when it was erected.

The data from the bricks dating to the time of erection in Sorø are shown in Fig. 5d (yellow squares) together with the bricks dating later (green circles). In this case, no differences in clay provenance are observed, and it is therefore likely that bricks dating to later times were identical to those dating to the time of the erection of the church and only exposed to fire later.

In all the cases, there is, however, also an alternative possibility, namely that newer bricks could have been manufactured later from the exact same clay resource as was used originally, but this is considered an unlikely scenario, because of the difficulty of locating and extracting precisely the same clay after several hundred years.

This is an important finding also in another aspect, namely that it allows the bricks from late-dating wall segments in some instances to be used in terms of all other parameters than the TL-dating. For instance, can the magnetic susceptibility, the mineralogical assemblages, or the colours of these bricks still be valuable pieces of information concerning the time of erection of the buildings.

The brick’s colours in general

An overview of the architecturally important colour measurements can be seen in Fig. 6. Even though the bricks of Chiaravalle and Cerreto are likely derived from the same clay source, as far as we can tell from magnetic susceptibility and the TL-sensitivity (see above), the colours, i.e., the appearances, are quite different (see Fig. 6c–d). The Chiaravalle bricks are generally less bright (lower L*) and have slightly higher chromaticity (higher c*) than those from Cerreto. This could be due to the age-difference (1105 ± 19 for Cerreto, versus 1267 ± 14 for Chiaravalle) whereby the clay resource could have changed slightly during the 150 years of exploitation possibly resulting in a difference CaO content77, or it could be an intended architectural decision obtained by sorting the bricks delivered at the building site or elsewhere as has previously been suggested for Sorø Cathedral69.

The colours of the bricks in the two Danish churches also differs on a general scale, as can be seen by comparing Fig. 6a–b. Most distinct is the many points with high L* (L* > 60) in Ringsted, which are missing altogether in Sorø. Furthermore, Ringsted features a subseries with low luminosity and low chromaticity, also not present in Sorø.

One pertinent question is if the colours are a dependant on the firing temperature. For 88 of the samples in the present study the firing temperature has been determined, and these have been plotted against the four parameters L*, a*, b*, and c* in Fig. 7. However, no discernible systematic correlations can be seen in any of these four plots, which leads to the likely inference that the magnitude of the firing temperature does not influence the colours of the bricks produced.

Maximum firing temperatures determined according to Rasmussen et al.76, versus a a*; b b*; c c*, and d L*.

Variations in the colour of the bricks between wall segments

The (L*, c*) diagram of colours are shown for the four churches in Fig. 8.

The plots of Fig. 8 can be rather confusing due to the high number of data points. If one instead compares only a couple of selected wall fragments instead of the entire data set, it becomes easier to discern some systematic variations of the colours. In Fig. 9 (L*, c*) is shown for a limited selection of wall segments. Bricks with two different appearances are present in almost equal amounts in wall segments S11-S20 and S31-S40 in Sorø Cathedral (Fig. 9a encircled areas). In Ringsted the bricks in wall segment R101-R110 is distinct from R51-R60 and R61-R70, both of which mutually overlap in the (L*, c*) diagram (Fig. 9b). The bricks from R101-R110 have, however, higher chromaticity (higher c*) and are less luminant (lower L*) than the other two sets of samples.

In Chiaravalle two distinctly different colours are discernible, mostly following C130-C139 and C195-C204 on the one side with the brightest and highest chromaticity bricks, and C160-C169 and C170-C179 on the other side with less colourful and less bright appearing bricks (Fig. 9c encircled areas). Finally, the bricks from Abbadia Cerreto a Lodi L205-L214 and L215-L224 are mostly distinct in colours, except for a single brick from L215-L224 being placed in the realm of L205-L215. Half of the bricks in wall segment L225-L234 exhibit lower luminosity than L205-L214 and L215-L224, the other half are indistinguishable from L205-L214 and L215-L224 in luminosity, while placed in between L205-L214 and L215-L224 in chromaticity saturation (Fig. 9d). There can, therefore generally speaking, in several cases and in all four churches be made distinctions between the appearances of the bricks in various wall segments. The only remaining question is, then, to which degree these measurable differences were premediated, and if so for what purpose the architects did as they did. This systematic variations in colours - and therefore in visual appearances - can hardly be haphazard.

In the case where two sets of bricks with different appearances were used intermixed in two different wall sections, like the case shown in Fig. 9a, c for S11-S20 and S31-S40 in Sorø and for several wall fragments in Chiaravalle, it is possible and even likely that the building masters intentionally mixed the two types of brick in order to avoid that stones of different shades would form abrupt transitions in the facade. On the other hand, when one appearance of the bricks is constrained to one wall segment, and a different appearance to another wall segment, like R101-R110 and R61-R70 in Ringsted, and L205-L214 and L215-L224 in Cerreto, the intentions of the building master could have been to control light and colour on a larger scale in the construction. One could argue that these examples could be due to haphazard coincidences, but such a possibility is diminished when it is found systematically in several of the churches.

Mineralogy of the bricks revealed by XRD and FTIR

The XRD results show that samples from Chiaravalle can be divided into two main groups. The first and larger group is C130-C179, C190-C204, and C304-C313, and the second and smaller group is the brickwork added on the western side of the front hall of Chiaravalle, C180-C189. The primary minerals in the first group are quartz, k-feldspars (microcline), and Na-plagioclase (albite) which are present in all the samples; a typical pattern from Chiaravalle is shown in Fig. 10. Trace amounts of calcite were also found, though it remains unclear whether the calcium carbonate is original to the clay or results from secondary deposition post-firing78,79. Some phases, such as hematite and Ca-plagioclase (anorthite), appear consistently and may reflect either residual components of the raw material or high-temperature neoformations formed during firing. A low gypsum content, likely due to environmental weathering80 is present in most samples. Other minor minerals include illite/muscovite, goethite, dolomite, hornblende, and akermanite.

The FTIR data support and enrich these mineralogical findings by indicating thermally induced transformations (Fig. 11)81,82. Rather than presenting a detailed list of spectral bands, the principal FTIR assignments and their implications are summarized in Table 4 for clarity.

FTIR spectra for two representative samples from Chiaravalle, KLR-12989/C141 (blue curves) and KLR-13028/C180 (light brown curves). The latter one of the high-Ca bricks later added to the western front hall. Top: measured transmittance. Bottom: second derivative. Abbreviations: Q: quartz, Cal: calcite, M-sm: meta-smectite, Dp: diopside, An: anorthite, Gh: gehlenite, M: muscovite, Sm: smectite, Mr: microcline.

The progression from band splitting to a single peak in the Si–O region is particularly telling: it reflects the reorganization of the silicate matrix as temperature increases. This, along with the appearance of high-temperature phases like gehlenite and diopside, indicates firing conditions exceeding 850 °C. The diminishing presence of muscovite and illite further corroborates this, as these clays dehydroxylate above 800 °C.

Although muscovite is described as rare in the mineralogical discussion, its detection in multiple samples, particularly through FTIR spectroscopy, reflects its partial preservation rather than abundance. This apparent contradiction is resolved when considering the sensitivity of FTIR to trace amounts of hydroxyl-bearing minerals. The weak bands associated with muscovite suggest it is present in low concentrations and may be vestigial remnants of incompletely transformed phases due to local temperature variability or incomplete firing. Thus, its presence does not contradict the broader interpretation of high firing temperatures but instead highlights heterogeneities within or between firing events.

Together, the FTIR and XRD evidence suggest that most bricks from Chiaravalle were fired above 800 °C, consistent with the observed mineralogical transformations and estimated firing temperatures ranging from 630 to 1090 (see Fig. 7).

The second group of Chiaravalle samples (C180-C189) exhibits higher levels of Ca-pyroxenes (6% to 15%) and slightly lower quantities of gehlenite ( < 5%). These are accompanied by notably higher calcite content, typically between 5% and 10% (Fig. 11). If Ca-clinopyroxenes were absent from the raw materials, their presence strongly supports high-temperature neoformation processes, likely resulting from calcite decomposition during firing above 850 °C83. The mineralogical profile of this group suggests either an alternative technological choice or constraints such as fuel availability or kiln design.

Bricks from Cerreto a Lodi display a broadly similar mineralogical composition to those from Chiaravalle, including quartz, feldspars, and albite (Figs. 12 and 13). However, the feldspar suite in Cerreto bricks is more diverse, incorporating orthoclase and sanidine in addition to microcline. The consistent absence of low-temperature clays and the increased presence of high-temperature minerals like anorthite and Ca-pyroxenes point to firing conditions equal to or exceeding those in Chiaravalle. This inference is supported by XRF data, which reveal elevated calcium levels in the Cerreto samples.

FTIR spectra from representative samples from Cerreto a Lodi (KLR-13202/L246, blue curves), Ringsted (KLR-12745/R51, dark red curves), and Sorø (KLR-12704/S10, light brown curves). Top: measured transmittance. Bottom: second derivative. Q: quartz, Cal: calcite, M-sm: meta-smectite, Dp: diopside, An: anorthite, Gh: gehlenite, M: muscovite, Sm: smectite, Mr: microcline.

In summary, the combined mineralogical and spectroscopic data clearly differentiate between inherited and neoformed phases, revealing nuanced information about firing temperatures and techniques. The thermal signatures embedded in these bricks reflect not only the materials and environmental context but also the technical proficiency of the artisans. Their ability to produce ceramics with targeted mineralogical traits highlights an intimate understanding of firing behaviour, likely passed down through generations of empirical practice.

The mineralogical and spectroscopic analyses of bricks from the Danish churches of Sorø and Ringsted offer valuable insights into both raw material selection and the technological knowledge embedded in the firing process. These data, particularly the identification of neoformation versus inherited mineral phases, allow us to reconstruct firing conditions and infer aspects of craftsmanship.

At Sorø, FTIR spectroscopy reveals a mineral assemblage comprising both inherited and thermally altered phases (Fig. 13). Quartz is present in all samples, evidenced by multiple strong bands, and is clearly a residual component of the original clay matrix. The presence of feldspathic and mica phases such as muscovite, microcline, and sanidine further confirms the geological origin of the raw materials. Simultaneously, the detection of high-temperature silicate phases like pyroxenes (e.g., diopside) and gehlenite suggests partial fusion and substantial chemical transformation within the ceramic matrix (Fig. 13). These mineralogical signatures point to firing temperatures in the range of 900–1100 °C. The co-occurrence of both neoformed and original minerals indicates a nuanced firing regime where temperature was sufficiently high to promote vitrification and structural strength yet controlled enough to preserve certain original components. This reflects a high degree of craftsmanship: the brickmakers were capable of tuning thermal conditions to produce optimal material properties.

The FTIR results are best understood in terms of broad compositional trends rather than isolated peak assignments. For clarity, key spectral assignments and their interpretations are summarized in Table 5.

Although muscovite is identified in multiple samples, its classification as “rare” refers to its typically low intensity and marginal abundance in both FTIR and XRD analyses. This apparent contradiction can be understood by considering the detection limits and sensitivity of the methods used: FTIR can register muscovite’s presence even in trace quantities, while XRD requires more crystalline content for reliable identification. Furthermore, muscovite’s thermal stability is limited, and its partial persistence suggests heterogeneities in firing conditions - either spatial variation within kilns or incomplete transformation due to moderate temperature exposure. Thus, its presence, while limited, does not undermine the interpretation of high-temperature firing but highlights localized variability in firing effectiveness.

The integration of FTIR and XRD data allows for a coherent interpretation of thermal treatment. In Sorø, the presence of gehlenite and pyroxenes aligns well with elevated firing temperatures and the partial breakdown of clay minerals. Meanwhile, the survival of smectite and kaolinite signatures suggests that these transformations were incomplete, either due to firing duration or local temperature variability within kilns. This mineralogical mix exemplifies a technologically sophisticated firing approach, were artisans likely balanced energy efficiency with structural durability requirements.

XRD data from Sorø further support this interpretation, showing dominance of quartz and amorphous phases, with variable amounts of K-feldspars, plagioclase, and hematite (Fig. 14). High-temperature phases such as Ca-clinopyroxene and gehlenite appear sporadically. The selective occurrence of these phases might be attributed to spatial variations in kiln conditions or differences in raw material batches.

In contrast, Ringsted samples show distinct mineralogical and thermal profiles. FTIR spectra indicate a firing temperature range of approximately 800–950 °C. This is slightly lower than at Sorø but still sufficient to induce the formation of neoformed minerals like diopside and possibly wollastonite (Fig. 13). The strong FTIR signals for calcite, however, point to either incomplete decomposition or significant re-carbonation. The presence of albite and muscovite alongside calcite and quartz suggests that a substantial portion of the original clay matrix remained intact (Fig. 13).

The variation between Sorø and Ringsted reflects more than just temperature differences; it also indicates differing technological choices or resource availability. Higher calcite content in Ringsted bricks could signal the use of different clays or intentional inclusion of calcareous materials. The limited appearance of high-temperature phases in some Ringsted samples may further imply shorter firing durations or the use of kilns with lower maximum temperatures.

Overall, the comparison between Sorø and Ringsted highlights how mineralogical findings—especially the distinction between inherited and neoformed phases—can inform our understanding of firing technology and craftsmanship. The careful orchestration of firing temperature to trigger specific transformations, while preserving certain functional mineral properties, underscores the expertise of historical brickmakers in adapting their methods to local materials and construction needs. Such evidence demonstrates that these materials are not merely passive remnants but active indicators of technological choices and artisanal knowledge.

The binders in the mortars

The binder-to-aggregate ratio in the mortars, B/A, is an important measure of the technology of the mortar production84. These ratios are shown in Fig. 15 for the 30 mortar samples investigated in the present work. The three churches Chiaravalle, Sorø, and Ringsted (excluding the two samples with extraordinarily high B/A-ratios in Ringsted, KLR-13311 and KLR-13314) feature similar average B/A-ratios within the uncertainties. Distinctly different from these three are the B/A-ratios for church in Cerreto, featuring c. 25% lower B/A-ratios.

The B/A ratio can be supplemented by the characteristics of the binders and the aggregates. The presence of lime lumps and remnants of unburnt limestone is likewise parameters depending on the technology applied in the mortar production64,84,85. In Sorø, mortars with remnants of unburnt limestone are common, while in Ringsted lime lumps are more frequent. In Chiaravalle and Cerreto this feature is also heterogeneous, there are samples with large lumps of unburnt limestone and lime lumps and others without. Through XRD analysis of an unburned fragment from L215-L224 and of a lump of lime from L245-L254 revealed the presence, respectively of magnesian calcite and magnesite, so we were able to conclude that the raw material used for the production of the lime was a magnesian limestone. The use of a calcitic air hardening lime binder is confirmed for the other three churches, so Mg-rich phases attributable to the binder were not registered in the XRPD analyses, nor were they observed in PLM. Furthermore, no recrystallisation phenomena or reactions with aggregates were observed in any sample of the church mortars.

Provenancing the aggregates in the mortars

Regarding the raw materials used for mortars production, we observe different lithologies in the aggregates of the mortar samples in Chiaravalle and Cerreto. The mortars contain quartz, metamorphic rocks, such as quartzite, lithofeldspathoquartzose, meta-sandstones, mica-schist, schist, and more, volcanic rock fragments, and less abundant, carbonate rock fragments and ophiolites, i.e., serpentinite and gabbros. All these lithologies are compatible with the sediments of Po Plain in Northen Italy, especially with the fluvial sediments of the western part of the plain from local rivers as the paleo-Adda and the paleo-Lambro in the last 1 Ma.

In the mortar samples from Cerreto, the main types of aggregates are quartz, quartzite, metamorphic rock fragments, and less frequently carbonate rock fragments or volcanic rock fragments, serpentinite, and serpentine-schists. All these lithotypes are widespread in the Pre-Alps86,87. They are compatible with the sediments transported by the Adda River88.

In the mortar samples C130, C138, C144, C160b, C170, C186, and C182 from Chiaravalle quartz is always present together with metamorphic rock fragments such as lithofeldspathic quartz-bearing, quartzite, mica-schist, meta-sandstones (consisting of quartz and phyllosilicates). Volcanic and meta-volcanic rock fragments and carbonate rock fragments are also very common; sedimentary rock fragments (siltites) are found less frequently. Mortar sample C150 differs somewhat from the others in that it contains volcanic rock fragments, metamorphic rock fragments, and secondary quartz. The origin of all these sediments is consistent with the sediments of the Po Plain near Milan and the deposits transported by the paleo-Lambro and paleo-Adda rivers88.

As mentioned above, two of the Ringsted mortars have such peculiar characteristics that they can easily be distinguished from the other samples (KLR-13311 and KLR-13314). Their aggregates consist mainly of quartz, carbonate rock fragments (mainly fossils), and granitoid holocrystalline rock fragments which consists of quartz, and microcline with oxides. The five remaining mortar samples feature similar aggregate compositions: carbonate rock fragments, quartz, granitoid rock fragments, and microcrystalline quartz. Finally, there is sample KLR-13313 from Ringsted, which can be considered an outlier as it has a visibly different binder (more greyish), aggregates of quartz, carbonate rock fragments and quartzite and a B/A-ratio of c. 1/3. This kind of aggregate deals with the Mid Danish Till that contains deposits that are probably of Baltic origin, but also sometimes sediments originating from Central Sweden89,90,91.

For the mortar samples from Sorø the composition of the aggregate varies, although quartz and carbonate rock fragments are most common in most of the samples, except for sample KLR-13395. This sample has aggregates consisting of sedimentary rock fragments, mainly pelite as the main component, with grain sizes of up to 9 mm. Samples KLR-13393 and KLR-13398 show other interesting features. The first sample contains a red granite fragment with a grain size of 8 mm and containing quartz with granophiric cuneiform texture compatible with the red granite from Dalarna in central Sweden92. The availability of rock fragments from central Sweden in the Zealand region is well known and due to the glacial transport of sediments during the last ice age. As for KLR-13398, it is noteworthy that this mortar contains a large, reused mortar fragment93. The latter has a micritic texture, a B/A ratio of 2/1 to 1/1 and a low macroporosity, while the newer mortar in which it is embedded has a B/A ratio of 1/3 and a micritic to microsparitic texture and a medium to high macroporosity.

The organic content of the mortars

The identification of the organic additives in the mortars was performed by Py-GC-MS analysis. Both samples from Italy and Denmark highlighted the presence of the pyrolysis products characteristic of a polysaccharide material; as an example, Fig. 16 shows the extract ion chromatograms of the ions with m/z = 217, representative of the markers deriving from the pyrolysis of this class of materials. In detail the analysis highlighted the presence of levoglucosan, together with anhydrosugar and disaccharide. No traces of pyrolysis products of lignin were detected in the chromatograms94,95,96,97. These pyrolytic profiles are consistent with a material characterized by high glucose content, such as for instance starch63,98. Glucose has also recently been suggested in the mortars of the terracruda statue in Afghanistan99.

From a qualitative point of view the chromatograms of the samples from Cerreto and Ringsted were characterized by similar pyrolytic profiles, suggesting the use of the same polysaccharide material used in the mortar formulation. From a semi-quantitative perspective, the samples from Sorø exhibited lower relative abundances of these species compared to those from Cerreto and Ringsted, while the samples from Chiaravalle contained only trace amounts.

The analysis also highlighted the presence of markers associated with proteinaceous material, with the same profile of diketopiperazines100,101. However, due to their low abundance, it was not possible to unambiguously identify these materials. Therefore, we cannot rule out the presence of other materials, or possible biological contamination.

Masonry observations—the building archaeological evidence

It is evident that the early Danish brick constructions included masonry craftsmanship and architectural details that can be found in Lombard brick churches as well. In Ringsted and Sorø, the facades’ cornice friezes of round arches supported by small columns have close parallels among Pavia’s churches, but other early Zealand brick buildings also contain eye-catching references. Both the North Zealand village church in Tikøb and the Benedictine monastery church in Skovkloster near Næstved had a portal inserted around 1200 with a decorative frieze of rhombuses in the arch, which exactly corresponds to the tracery in a choir window on the heavily rebuilt Milano Santa Maria di Brera from the end of the 1100’s. Correspondingly, there is a widespread use of bricks with a characteristic grooved surface, which can be attributed both decorative and technical significance, both in the Lombard brick architecture and in Northern European construction5. When looking at the interior decoration of the churches, it is worth noting that within recent years it has been established that the early Danish brick churches originally had a red plastering applied to the walls with white drawn joints, which has reproduced a tight and tactful brick limitation2,102. Similar wallpaper decoration can still be observed in the monastery churches of Chiaravalle and Ceretto, where the painting is also assumed to be original.

That the two large monastery churches in Chiaravalle and Cerreto can be attributed overall similarities with the approximately equally old monastery churches in Ringsted and Sorø is beyond any doubt. Most striking is the coincidence in the ground plans of the four churches, but this feature is basically not carried by Lombard building traditions, but rather the tradition of the Cistercian order. Based on these selected churches, the architectural detailing, on the other hand, shows no close commonalities, which confirms an influence from Lombardy to a distant region of northern Europe. Apart from the plan, the four monastery churches seem to be clearly tied together across borders by the painted brick decoration.

Considering the high technical quality of masonry that accompanies the early Danish brick constructions, it is beyond doubt that these first tasks with a new building material were carried out with the involvement of experienced builders and craftsmen, but they hardly came directly from Lombardy. This is evident from the present study of the four churches in Lombardy and Denmark, which were erected using a widely different masonry technique. While stone formats and alternations across the regions agree in the four churches, there are decisive differences in the walling itself, which in the two Lombard monastery churches is carried out with an accuracy that cannot be traced in the Danish parallels. In Chiaravalle and Cerreto, the walling of the well-preserved church rooms is done with very narrow joints of just a few millimetres in thickness. The individual bricks are also made with precise, right-angled edges, and to ensure even masonry flushes and precise detailing, the walls are further sanded after the masonry (Fig. 17). This masonry technique has required a great deal of specialist knowledge and has meant that the buildings came to appear as pure brick monoliths – the subsequent, tightening brick imitation seems almost redundant.

Masonry-wise, the two Danish monastery churches in Ringsted and Sorø follow completely different guidelines. The joints are up to 2 cm wide, just as the individual bricks are more irregular and the walls are not sanded (Fig. 18). The walling, which is no different from the solutions that otherwise followed in Denmark’s medieval brick architecture, must be attributed to the fact that the two churches on Mid-Zealand were not built by craftsmen who learned the masonry craft in Lombardy, where the masonry technique was handled with greater care. Rather, the two Danish monastery churches were built by a circle of craftsmen who knew the Lombard brick tradition second hand and passed it on in their own interpretation. In this ongoing transformation of the architectural starting point, only a few characteristic details and the brick-imitated paintings have been handed down in unbroken tradition.

Discussion

As was shown above the estimated times of erection of the four churches, 1185 ± 19, 1181 ± 16, 1258 ± 10, and 1108 ± 18 (1σ uncertainties), for Sorø, Ringsted, Chiaravalle, and Cerreto, respectively, do not as such support a direct transfer hypothesis, rather the opposite. Chiaravalle is considerably younger than expected, and the present datings do not speak for Chiaravalle to be a starting point for the spread of the Cistercian building activity on the Po Valley. Within the uncertainties the times of erection of the two Danish churches are similar (1185 and 1181), whereas Cerreto is considerably older (1105) and Chiaravalle significantly younger (1267) than the Danish churches. Cerreto is therefore ca. three generations older than the two Danish churches, while Chiaravalle is about 4 generations younger, using a conservative estimate of 25 years for a generation. The difference between the Danish churches and Cerreto is so large, that the data most likely speak against a direct transfer of knowledge from the building master’s responsible for the erection of the Cerreto Basilica. It is of course possible, that the transfer occurred not from the builders of Chiaravalle or Cerreto, but from some other sites in Lombardy, but that is beyond the scope of the present investigation to ascertain.

Concerning the details of the brick material, the clay sources seem to be similar in Cerreto and Chiaravalle which are situated some 20 km from each other and being erected some 150 years from each other, whereas they are different in the two Danish churches being built only 15 km from each other and at the same time - considering the uncertainty of the TL-datings. The mineralogical assemblages of the clay resource and the brick manufacturing techniques vary from church to church, both between the Danish churches and the Italian churches. These are not proofs as such of different modii operandi, but still some technical differences are observed here.

For all four churches, it seems likely that the building masters utilised nuance-differences in the bricks for architectural purposes. The acquired data do not support these differences in nuances to originate from differences in firing conditions, and it is therefore possible that the stones were purposely sorted according to colour on the building sites.

As was to be expected the aggregates in the mortars reflected the local geologies in Seeland and the Po Valley. The binder/aggregate ratios could potentially to a larger degree reflect a building master’s recipe. However, the B/A-ratios are similar within the uncertainties for Chiaravalle, Ringsted and Sorø, whereas Cerreto exhibits a somewhat lower binder/aggregate ratio. Concerning the organic components of the mortars, then they were characterized by using a polysaccharide material. Semi-quantitatively, the mortar samples from Sorø had lower relative abundances of polysaccharides than the mortars from Cerreto and Ringsted, while the mortars from Chiaravalle contained only trace amounts. All in all, the mortar analyses yielded no clear picture of similarities or south-north progression.

The architectural observations regarding the masonry are not as such supporting a hypothesis of a direct transfer from Lombardy to Denmark. The walling in the Italian churches is done with joints only a few millimetres wide, whereas the joints in the Danish churches are much more irregular and up to 2 cm wide.

Regarding the feeble hints in the historical sources, Clemmensen assumed that it was King Valdemar the Great’s chaplain, the later Bishop Radulf of Ribe (unknown – 1171), who had personally seen Pavia’s magnificent brick architecture when he was believed to have met Emperor Frederik Barbarossa (1155-1190) in 116013,14. However, recently this role for Radulf has been thoroughly refuted3. The historical sources therefore leave us without any real hints of a connection between Denmark and Lombardi at the time. This does not prove that there could not be a connection, it simply says that we do not know of any.

Collectively, the archaeometric data and the building archaeological observations do not point towards systematic similarities between the four churches or a south-to-north progression. Based on the new data and observations presented here there is therefore reason to question Clemmensen’s long-accepted hypothesis of a direct architectural influence from Lombardy to Denmark. The builders of the Middle Ages were indeed itinerant, but most likely the road from Lombardy to Denmark followed a more convoluted path, likely with an important stop in Northern Germany.

Data availability

Any data in addition to the data supplied in the **Supplementary Data 1** can be supplied by writing to the corresponding author.

References

Worsaae, I. I. A. & Herbst, C. F. The royal graves in Ringsted Cathedral. in Danish, Kongegravene i Ringsted Kirke (1858).

Bertelsen, T. in Sorø Abbey Church - Studies in History, Art and Architecture (in Danish, Klosterkirken i Sorø - Studier i historien, kunsten og arkitekturen) (eds Bertelsen, T. & Madsen, P. K.) (Odense University Press, 2025).

Madsen, P. K. Radulf, a mastermind from the 1200s–or the warm stone in the bed (in Danish, Radulf, en bagmand fra 1100-årene–eller den varme sten i sengen). Kirkehistoriske Samlinger, 7-60 (2022).

Denmark’s Churches, Sorø County (in Danish, Danmarks Kirker Sorø Amt). (1936–1938).

Bertelsen, T. Ringsted Abbey Church and the earliest brick (in Danish, Ex lateribus coctis: Ringsted Klosterkirke og den tidligste tegl). (Aristo bogforlag, 2021).

Witte, F. Baked Stones – Valdemar the Great and the Brick Wall in the Danevirke (in German, Gebackene Steine – Waldemar der Große und die Backsteinmauer im Danewerk). Ziegelei-Mus. 37, 6–25 (2020).

Kristensen, H. K. Øm Monastery (in Danish, Øm Kloster). Vol. 111 (Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2020).

Lester, A. E. in The Oxford Handbook of Christian Monasticism 232 (Oxford University Press (UK), 2020).

Jamroziak, E. Cistercian Customaries. A Companion to Medieval Rules and Customaries, 77–102 (2020).

Herrmann, C. & von Winterfeld, D. Medieval architecture in Poland: Romanesque and Gothic architecture between the Oder and Vistula rivers (in German, Mittelalterliche Architektur in Polen: romanische und gotische Baukunst zwischen Oder und Weichsel) Vol. 2 (Michael Imhof Verlag, 2015).

Stiehl, O. Brick construction of the Romanesque period, particularly in Northern Italy and Northern Germany: a technical-critical study (in German, Der Backsteinbau romanischer Zeit besonders in Oberitalien und Norddeutschland: eine technisch-kritische Untersuchung) (Baumgärtner, 1898).

Bagnoli, R. The Abbey of Chiaravalle Milanese: historical illustration, description of the church and the monastery (in Italian, L’ abbazia di Chiaravalle milanese: illustrazione storica, descrizione della chiesa e del monastero). (1934).

Clemmensen, M. The relationship between Lombard and Danish brick architecture (in Danish, Slægtskabet mellem lombardisk og dansk Teglstensarkitektur). Aarbøger for Nordisk Oldkyndighed R. XII (1924).

Johannsen, H. On the origin of our early brick churches: an overview and commentary on Mogens Clemmensen’s studies on the relationship between Lombard and Danish brick architecture (in Danish, Om vore tidlige teglstenskirkers oprindelse: en oversigt og kommentar til Mogens Clemmensens studier om slægtskabet mellem lombardisk og dansk teglstensarkitektur). Vol. Festskrift til Olaf Olsen på 60-års dagen den juni 1988 (1988).

Guarisco, G. & Oreni, D. The Chiaravalle Abbey and its refectory. Int. Arch. Photogrammetry Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 42, 587–594 (2019).

Sabaté, F. Life and religion in the Middle Ages (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015).

Cariboni, G., Cossandi, G. & D’Acunto, N. A border monasticism: the Cistercian Abbey of Cerreto in the Middle Ages (in Italian, Un monachesimo di confine: l’abbazia cistercense di Cerreto nel medioevo). Incontr. du Stud. 18, 1–297 (2020).

Holst, J. C. Did brick come with the monasteries?(in German, Kam der Backstein mit den Klöstern?). Vol. IV 112–122 (2014).

Radis, U. New Building Materials for Lübeck: The Interconnected Paths of Brick and Lime Mortar to Lübeck in the 12th Century (in German, Neue Baustoffe für Lübeck. Die vernetzen Wege des Backsteins und des Kalkmörtels nach Lübeck im 12. Jahrhundert). Mitteilungen Dtsch. Ges. für. Arch. Mittelalt. Neuzeit 30, 73–84 (2017).

Perlich, B. Medieval brick construction: on the question of the origin of brick technology (in German, Mittelalterlicher Backsteinbau: zur Frage nach der Herkunft der Backsteintechnik). Vol. 5 (Imhof, 2007).

Schöfbeck, T. in Backsteinarchitektur im Ostseeraum (ed Herrmann, C.) Ch. 42–53, (2015).

Rieger, D. & Schneider, M. Ordered, delivered, built – standardization in Lübeck (in German, Bestellt, geliefert, gebaut–Standardisierung in Lübeck). Archäol. Deutschland 32–35 (2020).

Lehouck, A. The very beginning of brick architecture north of the Alps: The case of the Low Countries in the question of the Cistercian origin. L’industrie cistercienne (XIIe-XXIe siècle), 41-56 (2019).

Debonne, V. From the clay, in bond. Building with bricks in the county of Flanders 1200-1400 (in Dutch, Uit de klei, in verband. Bouwen met baksteen in het graafschap Vlaanderen 1200-1400) dr. thesis, (2015).

Blain, S. et al. Combined dating methods applied to building archaeology: The contribution of thermoluminescence to the case of the bell tower of St Martin’s church, Angers (France). Geochronometria 38, 55–63 (2011).

Rapetti, A. M. The Milanese parchments of the 12th century from the Chiaravalle Abbey (1102-1160), preserved at the State Archives of Milan (in Italian, Le pergamene milanesi del secolo XII dell’abbazia di Chiaravalle (1102-1160), conservate presso l’Archivio di Stato di Milano). (2004).