Abstract

Cultural heritage value is essential for heritage protection and utilization. However, existing evaluation methods remain subjective and labor-intensive. To address these challenges, we propose the Vision Transformer-based Heritage Value Evaluation (ViT-HVE) model, the first deep learning-based model for heritage value evaluation. Taking heritage sites along the Yellow River in Shaanxi as a case study, we construct a ten-dimensional value system using Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) and establish the first Cultural Heritage Value Recognition (CHVR) dataset. To enable quantitative evaluation, we introduce the Top-k Heritage Value Weighting (TK-HVW) method, which derives value weights by extracting and normalizing probability distributions across value categories. Extensive experiments demonstrate that ViT-HVE outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods, achieving 0.890 Precision, 0.887 F1-Score, and 0.889 Accuracy. Furthermore, the predicted value distributions show strong alignment with expert evaluations, substantiating the reliability of our method and highlighting its potential for cultural heritage value evaluation and decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cultural heritage, recognized as a crucial repository of human history and civilization, holds immense academic value and profound cultural significance1. The protection and transmission of cultural heritage are essential for maintaining cultural diversity2, fostering international cultural exchange3, and promoting economic development4. Nevertheless, the preservation of cultural heritage frequently encounters challenges such as outdated value frameworks, inadequate regulations, and ambiguous priorities. A key underlying cause of these issues is the lack of a comprehensive and systematic value evaluation framework5.

The core component of cultural heritage—its value—offers individuals a sense of identity6, facilitates the transmission of historical and cultural knowledge 7, and fosters the sustainable development of both society and the economy8. The sustainable development of cultural heritage depends on evidence-based decision-making and management systems, with the central focus of these systems being the comprehensive and scientific evaluation of cultural heritage value9. In recent years, an increasing body of research has concentrated on the multidimensional evaluation of cultural heritage, encompassing aspects such as history, tourism, economics, and risks, with the aim of providing systematic and scientifically grounded decision-making support for the preservation and development of cultural heritage10. Consequently, determining how to conduct a scientifically rigorous, objective, and standardized evaluation of cultural heritage value has become a pressing issue that demands immediate attention.

Traditional methods of cultural heritage value evaluation typically depend on qualitative research from disciplines such as sociology, anthropology, and philosophy11,12,13. Qualitative research can provide in-depth insights into the intrinsic value and cultural significance of cultural heritage, contributing to an understanding of its socio-cultural context, historical evolution, and public perception. It plays an indispensable role in enhancing the connotation and depth of heritage evaluation. However, it exhibits limitations regarding universality and quantitative standards.

Data-driven quantitative evaluation approaches have attracted growing attention and recognition within academic research. By integrating multidimensional information, these methods enhance the accuracy of evaluations and offer more objective evaluation results, gradually establishing themselves as the dominant approach in the field of cultural heritage value evaluation. At present, quantitative evaluation methods primarily focus on economics and statistics. Bertacchini and Frontuto14, Bedatel et al.15, and Provins et al.16 have applied economic approaches to evaluate cultural heritage; Ma et al.17, Fan et al.10, Liu et al.18, and Chen et al.19 have utilized the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and other methods for evaluating heritage value. However, these methods exhibit certain limitations. For instance, while the AHP method offers a relatively objective quantitative research approach, it is often combined with the Delphi expert scoring method, which heavily relies on the subjective judgments of decision-makers. The construction of judgment matrices is susceptible to the influence of personal preferences and experiences of decision-makers. These limitations significantly hinder their ability to assess the value of cultural heritage in an objective, accurate, and efficient manner.

In recent years, machine learning technologies have made notable advancements in the field of cultural heritage. The technology has been successfully applied to various aspects, including analysis of heritage driving factors20,21, risk assessment22,23, travel evaluation24,25, and climate impact forecasting26,27, significantly enhancing the precision and efficiency of heritage documentation, analysis, and conservation. Building on this progress, our study employs Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) to systematically investigate the Yellow River cultural heritage in Shaanxi Province, aiming to identify, analyze, and synthesize its ten core values and establish an objective classification framework for further research.

Deep learning has demonstrated significant potential in the preservation and utilization of cultural heritage. Advanced image recognition and classification algorithms have been effectively applied to tasks such as heritage damage detection28,29,30,31,32, architectural style identification33,34,35,36,37 and artwork categorization38,39,40,41,42. Despite the impressive progress brought by deep learning in cultural heritage research, the automatic identification and evaluation of heritage value remain unexplored. Current research predominantly emphasizes physical elements, such as doors, windows, and rivers43, while neglecting a comprehensive analysis of both tangible and intangible values, including historical, preservation, and artistic significance. Although several studies44,45,46,47,48 have attempted to extract value-related features from images using deep learning, they predominantly focus on single value types or isolated visual characteristics, and are often confined to domains such as tourism and urban studies. This highlights a critical gap in the field: although deep learning has proven effective in recognizing physical features, there remains a pressing need for methods capable of evaluating the multidimensional values of cultural heritage. To address this challenge, our work focuses on the extraction of diverse value-related features that encompass both tangible and intangible aspects within the cultural heritage domain. Specifically, we introduce the first benchmark dataset for cultural heritage value recognition and develop a quantitative framework that integrates machine learning and deep learning techniques for the automated evaluation of heritage values.

Objectively and accurately recognizing and evaluating the value of cultural heritage serves as the foundational basis for its protection and utilization. Consequently, the application of machine learning and deep learning techniques for value identification, evaluation, and quantification becomes critically important. Building upon the results of recognition and evaluation weightings, our ultimate objective is to offer guidance and insights for the protection and utilization of cultural heritage. This approach not only provides a novel perspective and solution for cultural heritage protection and utilization, but also fosters theoretical innovation and practical progress within the field of cultural heritage research. Our contributions can be summarized as follows:

-

We propose an LDA-based approach that objectively identifies and classifies ten distinctive value dimensions of Yellow River cultural heritage in Shaanxi, providing a novel approach and a systematic foundation for heritage evaluation.

-

We present CHVR, the first large-scale dataset for cultural heritage value recognition, containing 30k images systematically annotated according to ten LDA-derived value dimensions, enabling comprehensive visual-based heritage evaluation.

-

We propose the first deep learning-based framework (ViT-HVE) for cultural heritage value recognition and quantitative evaluation by fine-tuning ViT model on the CHVR dataset. Additionally, we introduce TK-HVW, a novel probability-driven weighting method that extracts and assigns weights to the top three heritage value attributes from cultural heritage images, enabling objective and precise evaluation.

-

We assessed three fine-tuning strategies and conducted comparative evaluations of the ViT-HVE model against six state-of-the-art deep learning models. Furthermore, we performed an interpretability analysis using Grad-CAM to elucidate the decision-making process of our model. Extensive experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Methods

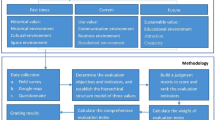

Figure 1 presents the overall workflow of our study, which systematically addresses cultural heritage value recognition and evaluation through four key stages: defining heritage value categories, constructing a labeled image dataset, selecting and fine-tuning evaluation models, and ultimately recognizing and conducting weighted evaluation of heritage values based on the model’s predictive outputs. In the following sections, we provide a detailed description of each stage to clarify the methodological design and implementation of our framework.

Study area

The Yellow River basin is one of the primary cradles of Chinese civilization, fostering the growth and development of the Chinese nation49. It harbors a vast and dispersed cultural heritage, which serves as a significant symbol of Chinese civilization. Shaanxi Province is situated in the heart of the Yellow River cultural region, and the importance of its cultural heritage is indisputable. This study is based on the Yellow River basin boundary data provided by the Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and focuses on the Shaanxi region of the Yellow River basin, covering an area of 132,872 km2, as the research scope.

Throughout history, Shaanxi, recognized as one of the key birthplaces of Chinese civilization, witnessed the Yellow River fostering early agricultural civilizations. The Yellow River not only provided a foundation for agriculture but also played a crucial role in the development of the country’s political system. The Guanzhong Plain, characterized by its fertile soil and abundant water resources, emerged as the political center for multiple dynasties. As a vital transportation and cultural exchange route, the Yellow River played a pivotal role in transforming the Guanzhong region into the starting point of the Silk Road and a hub for the convergence of diverse cultures, most notably reflected in religious sites and international cultural exchanges during the Tang Dynasty. The Yellow River cultural heritage system encompasses a rich historical, political, and cultural legacy, including its role as a Silk Road hub, folk culture, and ecological symbiosis, offering a comprehensive representation of the richness and diversity of Chinese civilization. Its profound historical and cultural significance holds immense value both domestically and internationally.

Based on information from national and local government websites, the Bureau of Cultural Heritage, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, and other platforms, a comprehensive database of cultural heritage resources along the Shaanxi Yellow River has been compiled. As of September 2024, a total of 1,675 cultural heritage sites have been identified in the Shaanxi Yellow River region, including 1,242 cultural heritage sites, 318 scenic spots, and 115 settlements. Spatial analysis using Arc GIS 10.8 reveals that the Shaanxi Yellow River basin is predominantly characterized by plateaus and plains (see Fig. 2). Cultural heritage sites are predominantly located along the main course of the Yellow River and the Wei River basin, with a spatial distribution exhibiting a central concentration and peripheral sparsity. Notably, there are more sites in the south and fewer in the north, with a strong concentration in the Guanzhong region, resulting in a clustered spatial distribution.

While our case study focuses on cultural heritage sites in the Yellow River region of Shaanxi Province, it is intended as a paradigmatic example rather than a limitation of scope. The value types proposed, such as Historical, Artistic and Preservation values, are broadly applicable across diverse cultural heritage contexts around the world. Given that cross-cultural or typological differences may influence the interpretation or prioritization of these values, the framework allows for adaptation to other regions by refining the value typology and incorporating localized image data for model fine-tuning. This flexibility enables broader applicability of the proposed approach to global cultural heritage settings.

Heritage value category construction

A comprehensive and objective analysis of cultural heritage value types serves as a critical prerequisite for both image data collection and subsequent recognition tasks. In contrast to the commonly employed AHP and Delphi expert scoring methods, our approach predominantly employs machine learning and bibliometric techniques. We systematically collect and download all papers related to the “Cultural Heritage Value of the Shaanxi Yellow River” from the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and Web of Science databases. Moreover, we compile local chronicles and relevant gazetteers from the Shaanxi Yellow River Basin, sourced from the official websites of local gazetteers, to serve as the text corpus. Subsequently, the LDA topic model is employed to extract themes from these data, with theme consistency used as the evaluation criterion for determining the optimal number of topics. Theme consistency refers to the degree of similarity between keywords within the same theme in the text corpus and is commonly used to measure the co-occurrence of thematic keywords within documents. By calculating theme consistency, we derive consistency scores for varying numbers of topics. When the number of topics reaches the optimal value, the consistency score attains its maximum50. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the consistency score reaches its peak when the number of topics is set to 10, which is therefore the chosen theme number for this study.

Based on the word clustering automatically generated by LDA, and in accordance with conventional practice, each topic was manually assigned a name by analyzing the associated keywords and considering relevant regional contexts51. The topics were subsequently identified as follows: Historical value, Developmental value, Geographical value, Folk value, Tourism value, Preservation value, Archival value, Revolutionary value, Ecological value and Artistic value (see Table 1). This process not only guarantees the scientific validity and logical coherence of the topic naming but also establishes a clear theoretical framework for the subsequent recognition and evaluation of cultural heritage values.

Data processing and collection

This study investigates the “Shaanxi Yellow River Cultural Heritage” with a primary focus on collecting image data and value characteristics of relevant heritage sites. Through extensive accumulation and research, more than 52,000 high-quality images have been collected, encompassing representative scenes from the majority of heritage sites. These images exhibit broad scope, abundant resources, and strong representativeness. The research team has undertaken numerous national and provincial-level projects focused on ‘Yellow River Cultural Heritage,” spanning over ten years, and has established a robust research foundation and extensive experience.

The process of dataset collection is illustrated in Fig. 4. In the initial stages of the research, a substantial amount of raw data was collected through various methods, including field visits, camera and drone photography, and surveys. These data comprehensively documented the current status, spatial distribution, architectural features, historical characteristics, and ecological environment of the Yellow River cultural heritage, thereby providing a solid foundation for subsequent research. Additionally, to further supplement and refine the data, inference and summarization were conducted based on specific keywords extracted from the LDA model, followed by internet searches to collect images and information related to the Shaanxi Yellow River cultural heritage, thereby constructing a comprehensive, accurate, and representative database of the Yellow River cultural heritage.

To enhance the analysis of cultural heritage values and improve the training efficiency of deep learning models, we summarized and inferred the value themes and keywords extracted from the LDA topic model for the Shaanxi Yellow River cultural heritage, and then conducted multiple rounds of image retrieval, filtering, cleaning, and classification on our database. Ultimately, 30,000 images with typical and representative characteristics were selected to create the Cultural Heritage Value Recognition dataset. These images were evenly distributed across the ten major value categories of the Shaanxi Yellow River cultural heritage, with each category containing 3,000 images, to facilitate the accurate recognition and evaluation of cultural heritage values. To visually illustrate the image diversity and value classification results, Fig. 5 presents representative samples from the ten defined cultural heritage value categories. Each value is presented with a typical image example and a description of the corresponding dataset, demonstrating the distribution and characteristics of the dataset used in value recognition tasks.

As a measure of annotation consistency, we conducted an inter-annotator agreement analysis using Cohen’s Kappa. To support this evaluation, three cultural heritage experts were invited to independently annotate a randomly selected subset of 2,000 images (200 per category) from the CHVR dataset. The results (Fig. 6) demonstrate a high level of agreement, with the distribution of Kappa scores concentrated above 0.85 and an overall mean of 0.869. These findings confirm that the annotation process achieved reliable and consistent labeling, thereby validating the robustness of the expert screening protocol adopted for dataset construction.

Additionally, image processing was carried out to ensure data consistency and analytical accuracy, as well as to address issues arising from variations in resolution, pixel density, and shooting angles across different devices. All images were subjected to normalization and resizing, irrelevant channels were removed from specific images, data quality was improved, noise caused by device discrepancies was minimized, and image naming was standardized, thereby ensuring a reliable foundation for subsequent analysis.

Compared to collecting images solely from the internet, the integration of field photography with images collected online (including social media) enhances the authenticity, comprehensiveness, and diversity of cultural heritage value assessment. Field photographs provide an accurate reflection of the current state of heritage, mitigating potential distortion or bias in online data and reducing one-sidedness. Conversely, images collected from the internet, particularly from social media, reflect public preferences and perceptions, offering diverse perspectives, emotions, and historical memories, thus enriching the representation and historical narrative of heritage. Moreover, this integrated approach incorporates standardized field data while incorporating diverse information from social media, thereby enhancing the accuracy of recognition and analysis.

To ensure ethical compliance, all collected images were either taken in publicly accessible and photography-permitted locations (e.g., outdoor heritage sites, museums, scenic areas) or sourced from open-access online platforms. The study does not involve any individuals, private data, or culturally sensitive/restricted sites, and therefore does not require IRB approval or community consent.

Model overview

Problem Definition: We formally define the heritage image value recognition task as follows: Let \({{\mathscr{D}}}={\{({x}_{i},{y}_{i})\}}_{i = 1}^{n}\) denote our proposed cultural heritage value recognition dataset, where each xi represents a heritage site image and yi ∈ {1, 2, …, l} corresponds to its discrete heritage value label. The model aims to learn a mapping function f: xi ↦ yi that associates images with their semantic labels. Heritage images frequently exhibit multi-value characteristics, and our objective is to capture all potential value labels associated with each image. Although our training paradigm adopts single-label supervision to predict the primary value yi, the model’s robust feature learning capabilities, enhanced by a transfer learning framework, enable it to implicitly capture latent inter-value correlations and structural semantics among value dimensions. Despite being trained under a single-label regime, the model leverages the rich semantic priors embedded in the pretrained backbone to internalize co-occurrence patterns across value categories. As visualized in Fig. 9, it not only distinguishes fine-grained semantic features of individual value types but also reveals underlying associations (e.g., the semantic proximity between “Historical value” and “Archival value”). This emergent behavior suggests strong multi-label generalization potential, which is crucial for real-world cultural heritage applications. To enable a probabilistic interpretation of the model’s predictions, we employ the softmax function \(\sigma {({{\bf{z}}})}_{j}={{\rm{Softmax}}}({{\bf{z}}})\) on the final layer logits z. This transformation maps the raw outputs to a categorical probability distribution over the l heritage value classes, where each component σ(z)j represents the relative evidence for value category j.

In this work, we propose a novel heritage value recognition and evaluation framework based on transfer learning with a Vision Transformer (ViT)52 backbone. Figure 7 illustrates the architecture of our proposed model. The processing pipeline begins with patch-wise decomposition of the input image into non-overlapping 16 × 16 patches. Each patch undergoes linear projection into an embedding space, augmented with positional encodings to preserve spatial relationships and a heritage value class token for global representation. The combined embeddings serve as input to our transformer encoder, which employs stacked self-attention layers to model long-range visual dependencies. The encoder’s output corresponding to the value class token is subsequently processed by an MLP head to produce the final logits.

To quantify the multi-faceted value composition of heritage images, we apply the softmax function to convert logits into a normalized probability distribution across value categories. Building upon this probabilistic framework, we introduce the Top-k Heritage Value Weighting (TK-HVW)—a novel quantification method that identifies the three most probable values and assigns importance weights proportional to their relative probabilities. In the following section, we provide a detailed description of each component of the model.

Linear embedding layer

Since Transformer models are inherently designed to process one-dimensional sequences, a two-dimensional image must be appropriately transformed into a compatible format before being input into the model. Let \({{\bf{x}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{H\times W\times C}\) represent a heritage image, where H, W, and C denote the height, width, and number of channels of the image, respectively. To standardize the input, we first resize the image to a fixed resolution of 224 × 224 pixels. Subsequently, the image is divided into N non-overlapping patches, each of size p × p, where N = HW/p2. Each patch, denoted as \({{{\bf{x}}}}_{p}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{p\times p\times C}\), is treated as a local region of the image. To ensure the preservation of fine-grained local features and intricate details in the heritage image, we set the patch size to p = 16. This choice balances computational efficiency with the ability to capture meaningful spatial information, which is critical for accurate heritage image analysis.

After the image is partitioned into several fixed-size patches, each patch undergoes a linear projection via a learned embedding matrix E, transforming it into a D-dimensional vector representation. This yields the patch embedding for each patch. Subsequently, these patch embeddings are augmented by a learnable heritage value token vvalue, which plays a pivotal role in the heritage value recognition task. To preserve the spatial relationships between image patches and prevent the transformer from interpreting them merely as unordered blocks, positional encoding Epos is incorporated into the embedding representation of each patch. Finally, the sequence of image patch embeddings, processed with positional encoding and combined with the value token, forms the token z0, as illustrated in the following equation:

Transformer encoder

After passing through the linear embedding layer, the sequence of patch embeddings z0 is fed into the transformer encoder (Fig. 7 (b)) for further processing. The encoder consists of 24 identical stacked layers. Each layer includes three core components: a Layer Normalization (LN) module to stabilize the training process by normalizing input embeddings, a Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) (Fig. 7 (c)) mechanism to capture global dependencies among image patches while preserving input information through residual connections, and a fully connected feedforward network to apply non-linear transformations and feature expansions, thereby enhancing the model’s representational capacity. Residual connections are employed between each component to ensure the stability of deep networks and facilitate effective feature propagation across layers. The input flow of the encoding layer can be described by the following equation:

MLP

The proposed ViT-HVE employs a two-layer Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) module, where the first fully-connected layer is followed by a Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU) activation function, defined as:

where Φ(x) represents the standard normal cumulative distribution function. This nonlinear transformation significantly enhances the model’s representational capacity. For the recognition task, we utilize a dedicated MLP-Head consisting of a single linear layer. The recognition process begins by extracting the first element \({{{\bf{z}}}}_{L}^{0}\) from the output sequence of the final transformer encoder layer, which corresponds to the learned value token embedding. This token, having aggregated global image information through the self-attention mechanism, is then processed by the MLP-Head to generate the heritage value prediction:

where W and b denote the learnable weight matrix and bias term, respectively, and y represents the output logits for heritage value recognition.

Top-k heritage value weighting

Heritage images inherently contain multi-dimensional value information that collectively forms their complex significance. The output of the MLP-Head does not fulfill the requirements of the heritage value evaluation. As ViT applies an argmax operation to the final output, it produces only the most dominant value in a heritage image as the predicted label. To adapt the model to the heritage value evaluation task and extract multiple value types along with their corresponding weights, we propose a probability-based Top-k Heritage Value Weighting (TK-HVW) method for quantitative analysis of multi-dimensional heritage values. Our approach first utilizes a fine-tuned ViT model to identify potential values in heritage images, then processes the model outputs through a Softmax function. This transformation converts the logits into a probability distribution, allowing the estimation of value-specific probabilities for each category. Subsequently, the obtained probability distribution is fed into the TK-HVW module to quantify and assign value weight within the heritage images. The TK-HVW method is formally defined as follows:

where pi denotes the predicted probability for the ith value category, and Sk represents the set of top-k categories (k = 3) with highest probabilities. This formulation ensures normalized weights within [0, 1] while preserving inter-category probability relationships. To determine the optimal number of value dimensions (k) in TK-HVW, we conducted a statistical validation using the Elbow Method. Specifically, for each image, we computed the cumulative contribution Ck of the top-k predicted value probabilities, defined as:

where pn denotes the nth highest predicted value probability. We then averaged Ck across all images to obtain \({\bar{C}}_{k}\). The resulting Elbow Curve, shown in Fig. 8, exhibits a clear inflection point at k = 3, capturing over 83% of the total semantic contribution. Beyond this point, additional categories contribute only marginally. We additionally examined the probability outputs of three randomly selected images, and observed similar results (as shown in Fig. 9). Therefore, we adopt k = 3 as the statistically optimal setting for value selection in TK-HVW.

The TK-HVW method enables balanced and interpretable weighting of multiple heritage values by normalizing the top-3 predicted probabilities. Unlike raw probabilities that may exaggerate disparities and hinder comparative evaluation, normalization preserves relative importance while mitigating the dominance of a single value. This supports cross-image comparison and subjective interpretation without distorting semantic differences.

Our method retains both the original probability distribution (reflecting the model’s confidence) and the normalized weights (enhancing comparability), ensuring a balance between objectivity and interpretability. In cases where normalized weights appear similar, this typically reflects genuinely close probability values—suggesting the coexistence of multiple significant heritage dimensions rather than a skewed prediction. Thus, normalization does not obscure meaningful differences but highlights semantic plurality.

Transfer learning

Deep learning methods in cultural heritage research typically require training models from scratch, which heavily relies on large annotated datasets and leads to inefficient training and poor generalization due to inadequate use of prior knowledge. To address these limitations, our model employs transfer learning53, reusing knowledge from models pre-trained on large-scale datasets to reduce dependency on labeled data and improve performance. Specifically, we fine-tune a ViT model pre-trained on ImageNet-21k54 on our cultural heritage value recognition dataset, effectively transferring prior knowledge to enhance accuracy.

To rigorously evaluate the effectiveness of transfer learning, we examined three distinct fine-tuning strategies as illustrated in Fig. 10: full fine-tuning, Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA)55, and linear probe. Full fine-tuning updates all parameters of the pre-trained model, enabling complete knowledge transfer while adapting to the target task requirements. In contrast, LoRA employs a parameter-efficient approach by freezing most model parameters and only training newly introduced low-rank matrices. The linear probe strategy represents the most computationally efficient approach, where only the MLP head is fine-tuned while keeping the entire backbone network frozen. We present a comprehensive comparison of these strategies’ transfer learning performance in section 3.3.

Grad-CAM

Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping)56 is a widely used visualization method that improves the interpretability of deep learning models by highlighting regions in the input that strongly influence predictions. It operates by computing the gradients of the target class with respect to the feature maps of a selected convolutional layer to assess the importance of each channel. These gradients are globally averaged to obtain channel-wise weights, which are then used to compute a weighted combination of the feature maps. The resulting class activation map is passed through a ReLU function to retain only the features with a positive impact on the prediction and is finally overlaid on the input to visualize critical regions.

In this study, Grad-CAM was employed to visualize and analyze the ViT-HVE model’s decision-making process and attention to heritage value features. The results reveal the model’s capacity to capture both global semantic context and fine-grained local details, offering valuable insights for the design and optimization of task-specific models.

Results

In this section, we thoroughly present the experimental details of the proposed method, followed by a comprehensive evaluation and discussion of its performance across various metrics.

Experimental setup

ViT-Large is adopted as the backbone network, with all experiments conducted within the PyTorch framework57 and executed on a 24GB NVIDIA 4090 GPU. The model pretrained on ImageNet-21k54 is loaded and fine-tuned on the CHVR dataset. During the fine-tuning process, the following experimental setup was employed: the optimization process was carried out for a maximum of 25,000 steps. The Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD)58 optimizer was utilized with a learning rate of 0.005 and a weight decay of 0.0005 to regularize the model. A warm-up period of 1,000 steps was incorporated to gradually increase the learning rate during the initial phase of training. The batch size was set to 64 to balance computational efficiency with model performance. For LoRA fine-tuning, we set the rank r and alpha to 8 and 16, respectively.

Evaluation metrics

To comprehensively assess the model’s capacity for identifying the main value of the heritage image, we employed four widely recognized metrics: precision, recall, f1-score, and accuracy. These metrics provide complementary insights into the model’s effectiveness in distinguishing between different heritage value categories.

Precision quantifies the proportion of correctly identified positive instances among all predicted positives for a given value class, defined as:

where TP (true positives) refers to instances that are correctly predicted as belonging to the target value class, while FP (false positives) denotes instances that are incorrectly predicted as such. A higher precision reflects the model’s ability to reduce false positive errors, which is especially important for heritage value categories characterized by subtle visual differences prone to misclassification.

Recall evaluates the model’s ability to identify all relevant instances of a class, defined as the ratio of correctly predicted positives to all actual positives:

where FN denotes false negatives - instances that were incorrectly predicted as other categories despite belonging to the target class. This metric is particularly important when missing positive cases (false negatives) carries significant consequences.

F1-score provides a harmonic mean of precision and recall, offering a balanced performance measure:

Accuracy represents the overall heritage value recognition performance across all categories:

where TN indicates true negatives - correctly rejected instances.

Comparison of Fine-tuning Method

We explore the influence of different fine-tuning strategies on the recognition performance of primary values in heritage images by comparing three representative approaches: Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA)55, linear-probe, and full fine-tuning. The hyperparameter configuration for each method was carefully optimized according to their respective trainable parameter scales. We referred to the hyperparameter settings reported in55 and59 as a starting point, and further employed grid search to identify the best-performing configurations for our task, particularly for sensitive parameters such as learning rate and weight decay. In our evaluation framework, each image’s primary heritage value served as the ground truth label, with model performance quantified by recognition accuracy.

As shown in Table 2, the full fine-tuning approach demonstrated superior performance in identification of the primary value, achieving significantly higher accuracy than both LoRA and linear-probe methods. This performance gap can be attributed to the fundamental architectural constraints of the latter approaches: while parameter-efficient methods like linear-probe and LoRA offer computational advantages through frozen backbone parameters, their limited adaptability proves inadequate for the nuanced task of heritage value recognition. The complexity of visual heritage features and the substantial scale of our dataset necessitate comprehensive parameter updates throughout the network architecture. Therefore, full fine-tuning was applied to both the ViT model and the baseline methods to ensure a fair comparison.

Model training

We trained the ViT-HVE model for 60 epochs and continuously monitored both the loss and accuracy during this process. The loss curves, shown in Fig. 11a, exhibit a sharp decline in both the training and validation losses in the initial epochs. This rapid decrease suggests that the model was quickly learning and adapting to the underlying patterns in the data. After approximately 20 epochs, the rate of decrease in both the training and validation loss curves began to slow, indicating that the model was approaching convergence and the learning process was stabilizing. Notably, throughout the training process, the training loss and validation loss remained closely aligned, demonstrating that the model was not overfitting to the training data and maintained a stable performance on the validation dataset.

In terms of accuracy, Fig. 11b demonstrates that both the training and validation accuracies increased steadily over time. Initially, the training accuracy increased rapidly, reflecting the model’s capacity to effectively learn the task. As training progressed, the rate of accuracy increase slowed, which is typical as the model refines its learned representations. Collectively, the accuracy and loss curves provide compelling evidence that the ViT-HVE model effectively learned the task without overfitting and demonstrated robustness across both training and validation datasets.

Model performance comparison

To validate the superiority of the model in this study for heritage image value recognition, we conducted comparative experiments with six representative models: EfficientNet-B560, ResNet-3461, DenseNet-12162, MobileNet-V263, GoogLeNet64, and Swin Transformer65. To ensure a fair and unbiased comparison, we used the pre-trained versions of these models and fine-tuned them on the same training dataset as ViT-HVE. In the experiments, we carefully optimized the hyperparameters of each network to ensure that each model achieved its optimal performance on the cultural heritage value recognition dataset. We further report the evaluation metrics for the recognition of the most significant heritage values to highlight the performance differences among the models.

Table 3 presents the comparative performance of various models on the CHVR dataset. The ViT-HVE model proposed in this study exhibits exceptional performance across all evaluation metrics, substantially outperforming the other six models. This superior performance indicates ViT-HVE’s remarkable capability in capturing complex image features, especially when processing heritage images with intricate visual details. Among the comparative models, DenseNet121 ranks second, benefiting from its dense connectivity architecture that enables effective feature propagation. Nevertheless, its performance in processing fine-grained heritage images remains inferior to our model.

ResNet-34 and EfficientNet-B5 demonstrate comparable performance, yet neither surpasses DenseNet-121, indicating inherent constraints of traditional CNN architectures in heritage value recognition tasks. Notably, MobileNet-V2 and GoogLeNet exhibit significantly lower performance metrics, with GoogLeNet achieving only 0.604 precision, 0.479 f1-score, and 0.500 accuracy. While these lightweight models offer advantages in computational efficiency for real-time applications, their simplified architectures and reduced parameters substantially limit their effectiveness in handling complex image recognition tasks.

In addition to the five CNN-based baselines, we also evaluated the Swin Transformer, which adopts a shifted-window attention mechanism to model local contextual features. Although its performance surpasses several CNN models, its F1-score (0.702) is still significantly lower than that of our proposed ViT-HVE (0.887).

This discrepancy mainly arises from its structural characteristics: Swin emphasizes localized attention, making it more suitable for tasks such as object detection and segmentation that demand fine-grained spatial details. However, in cultural heritage value recognition, images often contain elements that require a holistic understanding, such as symbolic motifs, compositional layouts, and narrative structures, that are difficult for Swin’s localized modeling strategy to capture. In contrast, ViT-Large employs global self-attention throughout the network, enabling it to effectively model long-range semantic relationships. This mechanism is particularly advantageous for tasks that require comprehensive semantic understanding. Moreover, the larger model capacity of ViT-Large enhances its ability to capture abstract cultural semantics. Therefore, although Swin offers efficiency benefits, its modeling capacity is less effective than ViT-Large in our task context, further supporting the rationale for adopting ViT-HVE.

Heritage value recognition performance of ViT-HVE

To thoroughly assess ViT-HVE’s performance, we conducted extensive experiments on the cultural heritage value recognition dataset. As shown in the confusion matrix (Fig. 12) and Table 4, our model demonstrates reliable performance in heritage value recognition. It achieves the highest F1-scores (0.93) in Revolutionary value and Preservation value. Archival, Folk, and Artistic values also show strong results, with an F1-score of 0.90. The confusion matrix further highlights that most predictions are concentrated along the diagonal, confirming the model’s overall discriminative ability, though occasional misrecognition occur among semantically close categories.

In contrast, slightly lower performance is observed for Historical (0.84) and Ecological (0.86) values compared to other categories. For the Historical value in particular, the modest decrease in F1-score can be explained by inherent challenges such as feature overlap and visual ambiguities within certain subcategories. For instance, historical heritage sites including ancient tombs, ruins, and excavation areas often suffer from low integrity and severe damage, which may visually resemble preservation-related scenes and thereby introduce classification difficulty. Grad-CAM analysis further indicates that, in these cases, the model occasionally attends to structural decay or protective components rather than historically discriminative attributes. Importantly, such confusion is not prevalent across all forms of Historical value, but rather limited to specific ambiguous instances. Similar challenges may also arise between other semantically adjacent value categories, which could be effectively mitigated in future work by incorporating metadata or multi-modal information.

The precision-recall (PR) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves provide further insights into the performance of our model. Figure 13 presents the PRC and ROC curves of the ViT-HVE model across all heritage value categories. The model achieves high average precision (AP) and area under the curve (AUC) scores for most classes, with APs exceeding 0.89 for nine out of ten categories and AUCs above 0.93 for all. Notably, Developmental value, Revolutionary value, and Preservation value achieve AUCs of 0.99, indicating excellent discriminative ability. Although Artistic value shows the lowest AP (0.80), its AUC remains high at 0.97, suggesting reliable overall performance. These results demonstrate the robustness of the model in both precision-recall trade-offs and recognition confidence across diverse value types.

Analysis of Grad-CAM results

Grad-CAM is employed to elucidate the decision-making process of ViT-HVE model. By computing the gradient of the target category with respect to the feature maps, we generate heatmaps that highlight the regions of the image that the model deems important. Areas in red and yellow indicate regions that contribute significantly to the recognition, whereas blue areas denote parts that contribute minimally or are irrelevant.

Figure 14 presents the visualization results obtained by applying Grad-CAM on ViT-HVE model. The results indicate that our model exhibits reasonable attention patterns for certain categories. For instance, in samples of cultural relics (such as ancient books and historic buildings), the model’s focus is predominantly on the key structural elements of the heritage, such as textual content and architectural details, suggesting that the model effectively learns features relevant to heritage value. However, in categories with more abstract characteristics (such as Developmental value, Ecological value, and Preservation value), the heatmaps are more dispersed, and there are instances of misalignment, indicating some limitations in the model’s ability to recognize these types of heritage values.

Furthermore, a comparison of Grad-CAM results across different categories reveals that the model’s attention is more concentrated on heritage categories with high contrast and well-defined structures (such as the Terracotta Army and traditional handicrafts), whereas it is more scattered for categories with low contrast or complex backgrounds (such as architectural complexes and natural landscapes). This discrepancy may be related to factors such as the distinguishability of visual features in the data.

User study

As mentioned in section 2.8, the proposed TK-HVW method enables the evaluation and quantitative weighting of cultural heritage values. To assess the accuracy of this method, we randomly selected ten cultural heritage images as validation samples. Figure 15 presents ten randomly selected images along with their corresponding recognition and evaluation results produced by the TK-HVW method. Blue-highlighted regions indicate the primary cultural heritage values identified for each image, and the top three value categories, together with their associated weights, are provided to facilitate comparison with expert evaluations.

To ensure scientific rigor and evaluation accuracy, this study engaged ten domain experts with extensive experience in cultural heritage preservation and utilization. Each expert independently ranked and scored cultural heritage images according to distinct value categories, ensuring both objectivity and diversity in the assessment outcomes. Prior to evaluation, experts received detailed methodological explanations, standardized review protocols, and unmodified heritage images (adjusted only for size and clarity) to minimize potential bias. Following predefined criteria for cultural heritage value types, the experts conducted their evaluations, guaranteeing a fair and reliable evaluation process.

The expert rating process for cultural heritage images was conducted in a structured manner. Each image was first examined with reference to the ten predefined categories of cultural heritage values. Experts then identified the three values that most appropriately characterized the image and established their relative ranking. Subsequently, numerical scores were assigned to the selected values in proportion to their perceived significance, with the constraint that the scores collectively summed to 1.0.

Based on the expert evaluation results, we constructed a manual scoring chart (see Fig. 16). The comparative analysis revealed a strong alignment between the deep learning model’s outputs and expert evaluations. The model achieved a 93.3% ranking hit rate for value selection accuracy (the blank areas in the figure denote values that were not assessed by experts) and 76.7% ranking accuracy for precise order matching, yielding an overall accuracy of 85%. While complete scoring alignment wasn’t achieved due to the broad value ranges, bar chart comparisons demonstrated that the model’s evaluations maintained substantial consistency with expert judgments overall, particularly in value identification and ranking. Through quantitative comparative analysis, the reliability and effectiveness of the proposed method were validated. These findings demonstrate that the deep learning model can accurately capture the true cultural heritage value of images, thereby offering empirical support for the ongoing refinement and application of the deep learning evaluation method.

Cross-regional generalization

To evaluate the cross-cultural generalization ability of our framework, we tested the ViT-HVE model on a set of heritage images from non-East Asian regions, including Southern and Eastern Europe, Sub-Saharan Africa and so on. These samples encompass diverse heritage types such as architectural sites, ritual performances, sculptural art, commemorative structures, and distinctive natural landscapes and landforms.

Figure 17 presents examples of heritage value recognition and evaluation for non-East Asian heritage images. Although the model was trained solely on East Asian cultural heritage data, it still demonstrates strong generalization ability across diverse non-East Asian contexts, including architecture, dance, and natural landforms. This indicates that the model has effectively learned the semantic attributes associated with different heritage values from large-scale data, enabling it to make contextually appropriate predictions across culturally and visually diverse inputs.

These results demonstrate that the model can generalize its value recognition capabilities to visually distinct and culturally diverse heritage contexts, even though it was trained on the East Asian-centric CHVR dataset. The consistency in identifying semantically meaningful values—such as Artistic, Historical, and Folk—across regions suggests that these value dimensions possess a degree of visual universality that transcends cultural boundaries.

Small-sample robustness

To assess the robustness of ViT-HVE under data-scarce conditions, we conducted a K-shot evaluation with K ∈ {1, 5, 10, 20}, where only K labeled samples per class were available for training. As shown in Table 5, the accuracy of ViT-HVE increases steadily with the number of labeled samples, demonstrating strong adaptability to small-sample scenarios. Specifically, when only one labeled image per class is provided (K = 1), the model attains 51.21% accuracy, indicating its ability to generalize from extremely limited supervision. As the number of labeled samples increases, the performance improves consistently, reaching 58.82%, 63.45%, and 69.73% at 5-, 10-, and 20-shot settings, respectively. These results confirm that ViT-HVE maintains competitive performance even with scarce labeled data, while scaling effectively as more annotations become available.

Discussion

In this paper, we introduce a deep learning-based framework, ViT-HVE, for the recognition and evaluation of cultural heritage values. This framework is the first to apply deep learning techniques to heritage value evaluation, effectively addressing the issues of subjectivity and inefficiency in existing methods. This study takes the Shaanxi Yellow River Cultural Heritage as a case study and utilizes the LDA topic model to construct a comprehensive classification system for cultural heritage values. Based on this foundation, we introduce the first cultural heritage value dataset, CHVR. To improve the model’s ability to recognize cultural heritage values, we adopt a transfer learning strategy by fine-tuning a pre-trained ViT-Large model on the CHVR dataset and compare three training methods: LoRA, linear probing, and full fine-tuning. We further compare the resulting ViT-HVE model with six baseline approaches to evaluate its effectiveness. Experimental results show that full fine-tuning yields the highest robustness in value recognition, and our method achieves superior overall performance.

Additionally, this paper introduces a probabilistic heritage value weighting method, TK-HVW, which transforms the model’s output into a probability distribution for each cultural heritage value category, facilitating the recognition and evaluation of the three most prominent values in an image. The expert evaluation confirmed that the model evaluations are highly consistent with those of the experts, demonstrating substantial alignment overall. This method offers a more objective approach to the quantification of heritage value.

Beyond performance metrics, this study contributes a practical and generalizable framework for cultural heritage analysis across three interrelated dimensions. To begin with, the proposed method achieves both high efficiency and accuracy in identifying value features of heritage images. By leveraging a deep learning architecture (ViT-HVE) guided by LDA-derived semantic labels, the model enables rapid feature extraction and quantitative evaluation, outperforming traditional manual or qualitative approaches that often suffer from low consistency and subjectivity. These findings provide robust technical support for tasks such as heritage classification, value assessment, and resource management. In addition, by integrating textual topic modeling with visual learning, the framework introduces a novel perspective to explore the implicit meanings, historical context, and classification structures embedded within cultural heritage datasets. This not only improves model interpretability but also contributes to constructing a clearer and data-driven understanding of value systems within heritage studies. Moreover, the proposed method demonstrates strong potential for real-world applications. It can be employed by heritage conservation agencies and cultural institutions for digital archiving, intelligent tagging, and content-based retrieval. By facilitating efficient and accurate value recognition, the approach supports broader initiatives in cultural heritage preservation, digital resource management, and knowledge dissemination. Its adoption could significantly enhance the accessibility, educational relevance, and governance capacity of cultural heritage informatics in the digital era.

Although this study has made outstanding contributions to the recognition and quantitative evaluation of cultural heritage value, it still faces certain limitations:

In this work, we adopt deep learning techniques to perform single-label, single-task classification of cultural heritage images. The model is initialized with pre-trained weights obtained under a single-label supervision setting, and subsequently fine-tuned on our dataset. To preserve the prior knowledge embedded in the pre-trained model and avoid potential interference with its internal representations, we adopt a single-label training paradigm. This approach enables the model to focus on the most salient cultural value per image, while minimizing annotation ambiguity and training instability. Although the single-label framework can effectively identify dominant cultural values, multi-label classification remains a promising direction and is left for future exploration.

Furthermore, the scope of this study is confined to the recognition and evaluation of cultural heritage values from images, with particular attention to tangible heritage—such as architectural structures, cultural relics, and physical sites—as well as selected forms of intangible heritage that have been visually documented. These types of heritage can be visually observed and digitally represented. Accordingly, certain forms of intangible cultural heritage, such as traditional oral literature, the languages in which it is conveyed, traditional music, and other non-visual cultural expressions, fall outside the scope of the present study. Furthermore, although many tangible heritage items are accompanied by nonvisual contextual information, including historical documents, ecological data, and oral narratives, such information was not incorporated due to challenges in data acquisition, restricted access to relevant sources, and limitations inherent in the current vision-based model architecture. However, relying solely on the image modality may not fully capture the complexity and multidimensional characteristics of cultural heritage. Although visual data provides valuable insights into its observable features, it may offer limited access to the deeper symbolic, historical, and sociocultural dimensions. Therefore, future research could benefit from exploring the integration of multimodal techniques - combining image, text, audio, and other data sources - to support cross-modal feature learning and semantic association extraction, thus improving the model’s comprehensive understanding of cultural heritage.

Data availability

Code and dataset will be available at https://github.com/wenlunxu/VIT-HVE.

Change history

09 December 2025

In this article, the funding source "Chinese Universities Scientific Fund (2452025075)" was inadvertently included in the Acknowledgements section. This has now been corrected.

References

Zhang, J., Jiang, L., Wang, X., Chen, Z. & Xu, S. A study on the spatiotemporal aggregation and corridor distribution characteristics of cultural heritage: the case of fuzhou, china. Buildings 14, 121 (2024).

Logan, W. Cultural diversity, cultural heritage and human rights: towards heritage management as human rights-based cultural practice. In World heritage management and human rights, 19–32 (Routledge, 2016).

Lähdesmäki, T. & Čeginskas, V. L. Conceptualisation of heritage diplomacy in scholarship. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 28, 635–650 (2022).

Galluccio, C. & Giambona, F. Cultural heritage and economic development: Measuring sustainability over time. Socio-Economic Plan. Sci. 95, 101998 (2024).

Jixiang, S. Step in the world of cultural landscape heritage (2010).

Yang, Y., Wang, Z., Shen, H. & Jiang, N. The impact of emotional experience on tourists’ cultural identity and behavior in the cultural heritage tourism context: An empirical study on dunhuang mogao grottoes. Sustainability 15, 8823 (2023).

Cao, K., Liu, Y., Cao, Y., Wang, J. & Tian, Y. Construction and characteristic analysis of landscape gene maps of traditional villages along ancient qin-shu roads, western china. Herit. Sci. 12, 37 (2024).

Buragohain, D., Meng, Y., Deng, C., Li, Q. & Chaudhary, S. Digitalizing cultural heritage through metaverse applications: challenges, opportunities, and strategies. Herit. Sci. 12, 295 (2024).

Díaz-Andreu, M. Heritage values and the public (2017).

Fan, X., Wang, Z. & Li, S. Value evaluation model (vem) of ancient chinese military settlement heritage: a case study of liaoxi corridor in the ming dynasty. Herit. Sci. 12, 97 (2024).

Fredheim, L. H. & Khalaf, M. The significance of values: Heritage value typologies re-examined. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 22, 466–481 (2016).

Mydland, L. & Grahn, W. Identifying heritage values in local communities. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 18, 564–587 (2012).

Apaydin, V. The entanglement of the heritage paradigm: values, meanings and uses. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 24, 491–507 (2018).

Bertacchini, E. & Frontuto, V. Economic valuation of industrial heritage: A choice experiment on shanghai baosteel industrial site. J. Cultural Herit. 66, 215–228 (2024).

Bedate, A., Herrero, L. C. & Sanz, J. Á. Economic valuation of the cultural heritage: application to four case studies in spain. J. cultural Herit. 5, 101–111 (2004).

Provins, A., Pearce, D., Ozdemiroglu, E., Mourato, S. & Morse-Jones, S. Valuation of the historic environment: The scope for using economic valuation evidence in the appraisal of heritage-related projects. Prog. Plan. 69, 131–175 (2008).

Ma, H., Li, S. & Chan, C. Analytic hierarchy process (ahp)-based assessment of the value of non-world heritage tulou: A case study of pinghe county, fujian province. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 26, 67–77 (2018).

Liu, F., Zhao, Q. & Yang, Y. An approach to assess the value of industrial heritage based on dempster–shafer theory. J. Cultural Herit. 32, 210–220 (2018).

Chen, X. et al. Evaluating urban industrial heritage value using industrial heritage matrix analytic hierarchy process models a case study of mawei shipbuilding in fuzhou city. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 12, 99–118 (2024).

Shao, D., Zoh, K. & Xie, Y. The spatial differentiation mechanism of intangible cultural heritage and its integration with tourism development based on explainable machine learning and coupled coordination models: a case study of the jiang-zhe-hu in china. Herit. Sci. 12, 1–22 (2024).

Fan, X., Mao, L., Zou, C., Wang, C. & Mo, D. Settlement strategies and their driving mechanisms of neolithic settlements using machine learning approaches: a case study in zhejiang province. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 186 (2025).

Rodriguez, J. M. P., Guida, A. G. & Fattore, C. Integrated analysis of urban heat islands in historical heritage contexts: The case of matera (2024).

Chen, Z., Gao, Q., Li, X., Yang, X. & Wang, Z. Beyond inundation: a comprehensive assessment of sea level rise impact on coastal cultural heritage in china. Herit. Sci. 12, 121 (2024).

Wang, J., Fan, W. & You, J. Evaluation of tourism elements in historical and cultural blocks using machine learning: a case study of taiping street in hunan province. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 30 (2025).

Zheng, X., Huang, Y., Xie, Z. & Zheng, A. Quantifying tourist perception of cultural landscapes in traditional towns in china using multimodal machine learning. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 320 (2025).

Boesgaard, C. et al. Prediction of the indoor climate in cultural heritage buildings through machine learning: first results from two field tests. Heritage Science10 (2022).

Wang, T., Zhang, M. & Li, Z. Explainable machine learning links erosion damage to environmental factors on gansu rammed earth great wall. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 366 (2025).

Kumar, P., Ofli, F., Imran, M. & Castillo, C. Detection of disaster-affected cultural heritage sites from social media images using deep learning techniques. J. Comput. Cultural Herit. (JOCCH) 13, 1–31 (2020).

Hou, M., Huo, D., Yang, Y., Yang, S. & Chen, H. Using mask r-cnn to rapidly detect the gold foil shedding of stone cultural heritage in images. Herit. Sci. 12, 46 (2024).

Qiu, H. et al. Research on intelligent monitoring technology for roof damage of traditional chinese residential buildings based on improved yolov8: taking ancient villages in southern fujian as an example. Herit. Sci. 12, 231 (2024).

Yang, S., Zheng, L., Chen, Y., Huang, Y. & Huang, Y. Artificial intelligence assists the identification and application of rural heritage wall surface damage in zhejiang. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 143 (2025).

Chen, X., He, J. & Wang, S. Deep learning-driven pathology detection and analysis in historic masonry buildings of suzhou. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 197 (2025).

Sasithradevi, A., Chanthini, B., Subbulakshmi, T. & Prakash, P. et al. Monunet: a high performance deep learning network for kolkata heritage image classification. Herit. Sci. 12, 1–14 (2024).

Han, Q., Yin, C., Deng, Y. & Liu, P. Towards classification of architectural styles of chinese traditional settlements using deep learning: A dataset, a new framework, and its interpretability. Remote Sens. 14, 5250 (2022).

Tao, J. et al. Classification and distribution of traditional grass-roofed dwellings in china based on deep learning. Land 13, 1595 (2024).

Gao, C. et al. Cross-cultural insights into traditional jiangnan gardens of china and japanese gardens through algorithm-enhanced comparative analysis. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 315 (2025).

Zhang, S. et al. A coordinate-to-semantic attention network for multi-label ancient chinese architecture image classification. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 14 (2025).

Sasithradevi, A., Sabarinathan Shoba, S., Roomi, S. M. M. & Prakash, P. Kolamnetv2: efficient attention-based deep learning network for tamil heritage art-kolam classification. Herit. Sci. 12, 60 (2024).

Dorozynski, M. & Rottensteiner, F. Deep descriptor learning with auxiliary classification loss for retrieving images of silk fabrics in the context of preserving european silk heritage. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 11, 82 (2022).

Varshney, S., Lakshmi, C. V. & Patvardhan, C. Madhubani art classification using transfer learning with deep feature fusion and decision fusion based techniques. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 119, 105734 (2023).

Sandoval, C., Pirogova, E. & Lech, M. Two-stage deep learning approach to the classification of fine-art paintings. IEEE access 7, 41770–41781 (2019).

Hu, Y., Wu, S., Ma, Z. & Cheng, S. Integrating deep learning and machine learning for ceramic artifact classification and market value prediction. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 1–17 (2025).

Tan, G., Zhu, J. & Chen, Z. Deep learning based identification and interpretability research of traditional village heritage value elements: a case study in hubei province. Herit. Sci. 12, 200 (2024).

Xiao, X., Fang, C., Lin, H. & Chen, J. A framework for quantitative analysis and differentiated marketing of tourism destination image based on visual content of photos. Tour. Manag. 93, 104585 (2022).

Zhang, K., Chen, Y. & Li, C. Discovering the tourists’ behaviors and perceptions in a tourism destination by analyzing photos’ visual content with a computer deep learning model: The case of beijing. Tour. Manag. 75, 595–608 (2019).

Xiao, X., Fang, C. & Lin, H. Characterizing tourism destination image using photos’ visual content. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 9, 730 (2020).

Zhang, H., Jiang, J. & Guo, X. Hsvi-net: a deep learning network for scene understanding based on panoramic street-view images within historical districts. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 383 (2025).

Ogawa, Y., Oki, T., Zhao, C., Sekimoto, Y. & Shimizu, C. Evaluating the subjective perceptions of streetscapes using street-view images. Landsc. Urban Plan. 247, 105073 (2024).

An, Z. & Wang, K. Yellow river culture and chinese civilization. Journal of Literature, History & Philosophy 3–13 (1992).

Zhang, S. Exploring thematic evolution in interdisciplinary forest fire prediction research: A latent dirichlet allocation–bidirectional encoder representations from transformers model analysis. Forests 16, 346 (2025).

Büschken, J. & Allenby, G. M. Sentence-based text analysis for customer reviews. Mark. Sci. 35, 953–975 (2016).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16 x 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2021).

Weiss, K., Khoshgoftaar, T. M. & Wang, D. A survey of transfer learning. J. Big data 3, 1–40 (2016).

Ridnik, T., Ben-Baruch, E., Noy, A. & Zelnik-Manor, L. Imagenet-21k pretraining for the masses. In Thirty-fifth Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems Datasets and Benchmarks Track (2021).

Hu, E. J. et al. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2021).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 618–626 (2017).

Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Advances in neural information processing systems 32 (2019).

Robbins, H. & Monro, S. A stochastic approximation method. The annals of mathematical statistics 400–407 (1951).

Zhu, Y. et al. Melo: Low-rank adaptation is better than fine-tuning for medical image diagnosis. In 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 1–5 (IEEE, 2024).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In International conference on machine learning, 6105–6114 (PMLR, 2019).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 770–778 (2016).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K. Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 4700–4708 (2017).

Howard, A. G. et al. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. doi: 10.48550. arXiv preprint arXiv.1704.048611704 (2017).

Szegedy, C. et al. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 1–9 (2015).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 10012–10022 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China (Art Studies Western Region Project, Grant No. 25EH283): Research on the Value Evaluation of Yellow River Cultural Heritage and the Construction of Cultural Tourism Brand.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wenlun Xu and Bo Huang conceptualized the research idea, conducted the experiments, collected the data, and drafted the manuscript. Ying Tang contributed to the manuscript revision and data collection. Chengyong Shi provided guidance on the paper's innovative direction, offered revisions, and supervised the entire process. Yifei Wang was responsible for data collection, analysis, and manuscript revision. Shuya Kong and Pengyue Yan contributed to data collection and manuscript analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, W., Huang, B., Tang, Y. et al. ViT-HVE: a vision transformer-based framework for recognition and weighted evaluation of cultural heritage values. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 571 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02143-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02143-6