Abstract

This study presents a multi-analytical investigation of six Renaissance drawings by Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, and Perugino, focusing on their materials and techniques. Using a combination of microscopy, multiband imaging, X-ray fluorescence mapping, and Raman spectroscopy, the research revealed the complex layering and application of media such as red chalk, metalpoint, and iron gall ink. Findings include the identification of bone ash preparatory layers, amalgamated silver metalpoint, lead white highlights, and iron gall inks with varied compositions. These discoveries offer insights into the artists’ working processes, material choices, and the broader practices of the Renaissance workshop. Until this study, the artistic media in these works had been assessed by visual examination only. The study demonstrates how non-invasive scientific methods can uncover otherwise invisible aspects of artistic production, enriching both technical understanding and art historical interpretation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drawings are a window into the working process of an artist. Renaissance artists continuously experimented with forms and compositions, working out details of gesture, light and shadow, and the interplay of figures, drapery, architecture, and landscape. Over the past several decades, studies of Renaissance drawings involving traditional connoisseurship, stylistic analysis and increasingly sophisticated methods of examination and analysis have highlighted the central role these works played in the creative processes of artists and have provided further insights into how artists used materials to plan and refine their designs1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. More recently, advances in non-invasive methods, such as X-ray fluorescence mapping (MA-XRF), multiband imaging, microprofilometry, and optical coherence tomography, have expanded the analytical capabilities for studying fragile drawings11,12,13. The integration of scientific analysis with art historical inquiry has thus provided a fuller, more nuanced understanding of how Renaissance artists conceived, constructed, and refined their drawings, affirming the significant role of materiality in their creative processes.

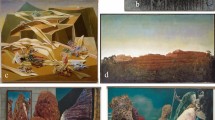

In this study, four drawings by Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio or Santi, Urbino 1483–1520 Rome), one by Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452–1519 Amboise), and one by Perugino (Pietro di Cristoforo Vannucci, Città della Pieve, active by 1469–died 1523 Fontignano) were studied to characterize and analyze the paper support preparations and the various applied drawing media such as chalk, metalpoint, and ink. Table 1 lists the drawings’ titles, their dimensions, names of the artists, credits lines, and the main components of media identified.

This investigation was prompted by the Raphael: Sublime Poetry exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (March–June 2026) which will be accompanied by a comprehensive catalog that fully discusses the history and context of these drawings14. Below are summaries and brief references for each of the works examined and analyzed in the present study.

C.C. Bambach has proposed that Studies of the Christ Child, 1513-14 is a preparatory drawing for a composition of the Holy Family with the Infant Saint John, known from two painted versions mostly executed by Raphael’s close assistants (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna and Galleria Borghese, Rome)(Bambach, C.C., 2006 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/340579, accessed 07/24/2025). The recto of Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist, ca. 1506-7 was in a preparatory composition of the ‘Holy Family with the Infant Saint John,’ one of several that survive, with art historical research suggesting that it is the last in the sequence of extant preparatory drawings. The drawing on the verso, Study of a Nude Male Figure (Nude Male for short), also relates to several paintings on the subjects of Entombment and Descent from the Cross (Bambach, C.C., 2006 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/340577, accessed 07/24/2025). C.C. Bambach related the working drawing Lucretia,1508-10 to the famous large-scale preliminary studies for the figures in the Parnassus and the School of Athens, painted in fresco in the Stanza della Segnatura (Vatican Palace) (Bambach, C.C., 2009 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/337075, accessed 07/24/2025)15. The head on the recto of Small Head of a Christ Child or Saint John the Baptist, 1504-5, the only drawing of the group studied that is in a private collection, is close in pose and appearance to that of the Christ Child in the ‘Ansidei Madonna,’ 150516 (https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2004/old-master-drawings-l04040/lot.23.html, accessed 07/24/2025). Also included in this investigation are Perugino’s Study of a Kneeling Youth and of the Head of Another, 1500, where the kneeling youth depicted wearing a hooded habit is a study for one of the members of the Confraternity of St. Augustine in a ca. 1500 painting by Perugino now in the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh17 (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/340467, accessed 07/24/2025); and Leonardo’s Compositional Sketches for the Virgin Adoring the Christ Child, with and without the Infant St. John the Baptist; Diagram of a Perspectival Projection (recto); Slight Doodles (verso), 1480-85 (Bambach, C.C. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/337494, accessed 07/24/2025)18. For this last drawing, C.C. Bambach states that the composition in the center is closest to the ‘Virgin of the Rocks’; like many drawings from this period, it was used to work out formal aspects and details of the composition18.

These drawings are complex, both in terms of their visual construction and material composition. They reflect a sophisticated interplay of multiple media—such as red chalk, metalpoint, iron gall ink, and white highlights and exemplify intentional planning, adaptation, and revision, offering insight into the artists’ evolving thought processes. The use of preparatory layers, the integration of amalgam metalpoint, and the subtle shifts in technique across different areas of the paper contribute to the intricate nature of these works. Until the present study, the artistic media in these six drawings had been assessed by visual examination only. Our work contributes to the identification of patterns in the material practices of Renaissance artists, while also distinguishing the working habits of individual artists.

Methods

The drawings were examined with the naked eye under normal, raking, transmitted, and UV illuminations, under the magnification of a stereomicroscope, in concert with imaging, followed by non-invasive methods of characterization and chemical analysis. Visual examination revealed information about how the artist applied the media, how these media interacted with the support, and how they influenced the current appearance of the drawings. Images were acquired with different types of radiation, from long-wave ultraviolet to near infrared, in normal, specular, transmitted, and raking configurations, to visualize features and contribute to the characterization of the materials. Non-invasive techniques of chemical imaging and analysis, including X-ray fluorescence (XRF) mapping and Raman spectroscopy, were also used.

Microscopy

Observations were made using stereo binocular and digital microscopes. All digital micrography was recorded with epi-illumination unless otherwise stated in caption and was completed with a Hirox HRX-01 digital microscope, equipped with a telecentric auto-zoom lens (10-200x).

Multiband imaging

For multiband imaging (MBI), a modified Canon 5DSR camera with full spectrum conversion (270–1100 nm) was used. The workflow consisted of using a standard copy set-up with LED fixtures designed at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. These ISO 3664 compliant, linear and rotating lights comprise seventy-two LEDs for each configuration, including visible white, 365 nm ultraviolet and 950 nm infrared radiation channels.

Different combinations of filters were added to the camera lens, a Coastal Optics Apochromatic, 60 mm; to record a set of images including an IDAS-UIBAR III, 400–680 nm, for visible (VIS); XNite 330 C + XNite BPI, 270–400 nm, for ultraviolet reflected (UVR); IDAS-UIBAR III + Wratten 2E, 420–680 nm, for ultraviolet induced visible fluorescence (UVF); and XNite 830, 830–1100 nm, for infrared imaging (IR). Once captured, the digital files were calibrated using a standardized color profile for both VIS and UVF imaging, and four grades of Spectralon® material for IR and UVR.

Point X-ray fluorescence (p-XRF)

P-XRF measurements were performed under a He atmosphere, using a Bruker Artax 400 instrument equipped with a Rh-target X-ray tube operated at 20–30 kV and 800–1000 μA, and a 1 mm collimator. Unfiltered radiation and a 200 s live collection time were used.

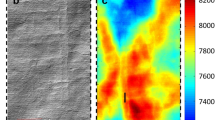

X-ray fluorescence mapping (XRF mapping)

XRF mapping analyses were done using a Bruker M6 Jetstream system equipped with a Rh source operated at 50 kV and 600 μA. The parameters used for the drawings studied were the following: 200 μm spot size, 180 μm step size, and 70 msec/pixel dwell time for Studies of the Christ Child; 200 μm spot size, 180 μm step size, and 60 msec/pixel dwell time for Madonna and Child and Nude Male; 200 μm spot size, 180 μm step size, and 40 msec/pixel dwell time for Small Head; 330 μm spot size, 300 μm step size, and 55 msec/pixel dwell time for Lucretia; 200 μm spot size, 150 μm step size, and 70 msec/pixel dwell time in Study of a Kneeling Youth. For scanning the full area of Compositional Sketches for the Virgin Adoring the Christ Child a 300 μm spot size, a 250 μm step size, and a 70 msec/pixel dwell time were used; a smaller area including all the human figures on the recto was mapped with a 200 μm spot size, a 150 μm step size and a 70 msec/pixel dwell time. The data was processed using the Bruker software and, in selected cases, open source PyMCA (5.9.2 version) and Datamuncher19.

Raman spectroscopy

Non-invasive Raman analyses were performed in all the drawings using a Renishaw System 1000 coupled to a Leica DM LM microscope. The spectra were acquired with a 785 nm laser excitation focused on the drawings using a long-working distance 20× objective lens. A 1200 lines/mm grating and 30–60 s integration times were used, and powers were set between 0.5 and 5 mW using neutral density filters.

Results and discussion

The presentation and discussion of the results in this section are organized by medium, namely red chalk, white highlights, iron gall ink, and metalpoint.

Red chalk

Three of the drawings examined, Studies of the Christ Child (Fig. 1a), Small Head (Fig. 2a) and Madonna and Child (Fig. 3a), show Raphael’s masterful handling of a friable orange-red medium typically called red chalk. Red chalk, an iron-containing mineral, often an iron oxide, has been used for thousands of years as a drawing material that does not require any type of binder or processing, only to be cut into handheld size sticks or chunks; no preparation of the paper substrate is necessary to draw with red chalk20. The artists’ material is sufficiently compacted to be used in stick form and will transfer and adhere color to paper when stroked across the surface of the paper. Chalks can be powdery and soft, but also, they can make thin precise lines depending upon the hardness of the naturally occurring material and the drawing technique of the artist.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1997 (1997.153). a Visible light image. b Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence (UVF) image. c Combined Fe (orange) and Pb (white) distribution maps. Blue arrows indicate areas of what appear to be features not intended by Raphael and possibly later repairs. d Mn (purple) distribution map.

a Visible light image. b Infrared image showing Pb metalpoint markings. c Raking infrared image showing incised lines. d Combined Fe (orange) and Pb (white) distribution maps. The Fe distribution reflects the presence of red chalk and iron gall ink on the recto, and iron gall ink on the verso; the Pb distribution reveals the location of Pb metalpoint as seen in (b). e Verso, visible light image. f Verso, infrared image showing heavy application of iron gall ink and a black medium. g Zn (white) distribution map. h Photomicrograph of the area of the sitter’s nose, indicated by blue arrow in a, showing the presence of various media: (1) white material identified as gypsum, (2) Pb metalpoint, (3) iron gall ink, and (4) red chalk. Original magnification: 90x.

Studies of the Christ Child depicts three figures that are trials for the body in different postures (Bambach, C.C., 2006 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/340579, accessed 07/24/2025). In this drawing, Raphael used thin definite lines, applied with some pressure, to define and reinforce the outlines of the figures, particularly of the torsos. He employed softer lines, done with less force and a blunt piece of chalk, to allow the color to land on the high points of the sheet only, to give the effect of shadow in the jawline and eyes of the right-side figure. A rapidly applied series of almost scribbled lines run along the sides of the figures to create the illusion of three-dimensionality by defining the shadows. Raphael’s skilled use of the medium is also evident in Small Head, where the nuanced application of red chalk in line and shadow is evident (Fig. 2a). The elemental distribution maps showed that in both drawings the red chalks contain Fe (Figs. 1c and 2d), as expected, and some Mn (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. S2b, Supplementary Information File, SI), a naturally occurring component associated with some Fe-containing minerals21,22. Raman spectroscopy analysis gave, in both cases, main bands at ca. 291, 406, and 608 cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. S1, spectra a and c, SI File), consistent with features expected for a red ochre22.

Madonna and Child (Fig. 3a) demonstrates Raphael’s ability to make quick light marks to generally suggest the composition before reinforcing outlines and deepening shadows with the same medium, creating a dexterous array of lines that formed complex overlapping figures. With red chalk, Raphael effectively conveys a range of textures such as the soft flesh of the pudgy baby limbs to the crisply folding drapery, while capturing the figures’ demeanor and the focus of the final arrangement. The chalk medium enabled him to draw quickly, shifting the composition during his working process. Similar to Studies of the Christ Child and Small Head, the elemental distribution maps showed that the red chalk is composed of Fe (Fig. 3c) and Mn (Supplementary Fig. S4d, SI File), and Raman analysis confirmed the presence of a red ochre (Supplementary Fig. S1d, SI File). Fe and Mn are also components of the ink used for the Nude Male drawing on the verso of Madonna and Child, therefore the ink strokes register in the corresponding maps; the composition of this ink is discussed below. It is notable that the chalk hue in Studies of the Christ Child and Small Head is more orange than that of Madonna and Child, which veers slightly toward maroon; these variations in hue are typical of red chalks.

White highlights

Multiband and chemical imaging of Studies of the Christ Child exposed the presence of an additional medium. UVF showed a brush-applied material in areas on the rounded forms (Fig. 1b), clearly meant to be highlights, which can be found in other drawings of this period23. XRF mapping revealed the presence of Pb (Fig. 1c), and in situ Raman spectroscopy analysis confirmed Raphael’s use of the lead white pigment, 2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2, with a main band at 1050 cm−1 24 (Supplementary Fig. S1b, SI File), giving insight into the artist’s original intent to emphasize the volumetric character of the figures and to position the direction of the light in his approach to rendering these forms. Highlights also serve the purpose of broadening the range of tones depicted. In Studies of the Christ Child, the lead white highlights are not visible with the naked eye; their appearance in the UVF image suggests that the lead white is bound in a drying oil, which often causes the paint to become more transparent over time due to an increase in the refractive index of the binding medium25. The Pb distribution map also shows that other areas in this drawing contain lead white, such as those in the lower left corner, which may correspond to repairs executed over the years emphasizing the complexity of materials studies.

Iron gall ink

Nude Male is executed in an ink that has a mid-tone brown to deep golden hue and the typical visual appearance of iron gall (Fig. 3b). Raphael’s approach in this work is like that in his other drawings where he used multiple lines in one feature, such as the shoulder, to seek and refine the figure’s forms through the drawing process. Chemical analysis by XRF mapping showed that the main components of the ink are Fe (Fig. 3c) and Mn (Supplementary Fig. S4d, e, SI File), consistent with an iron gall26.

Iron gall ink was used for the drawing of the vessel on the verso of Small Head (Fig. 2e). In this case, in addition to Fe and Mn, Zn was detected (Figs. 2d, 2g and Supplementary Fig. S2b, SI File). On the recto, a stroke of brown ink that visually appears to have been applied intentionally was observed by microscopy on the tip of the nose (Fig. 2h); XRF mapping indicates that it contains the same elements as the iron gall ink in the vessel. Historical recipes for making iron gall inks generally call for boiling a mixture of three basic ingredients: a source of tannins, such as gall nuts, small growths formed on oak trees as a defense against insects, primarily wasps; an Fe-containing mineral, typically vitriol or powdered scrap metal; and a natural resin or tree gum such as gum Arabic to act as a binder27,28,29. Iron gall inks can have substantial variations in their compositions. For example, iron vitriols, in addition to their main component FeSO4.7H2O, have varying amounts of Cu, Mn, Zn, Al, K and Mg, in proportions that vary depending on the mining site and the method used for extracting the mineral30. In general, multiple variations in the ingredients other than vitriol and in the recipes also result in different ink compositions27,28,29,31,32.

On the recto of Small Head, a white mark was observed by microscopy on the tip of the nose (Fig. 2h). The white material was analyzed by Raman spectroscopy and found to be gypsum, CaSO4. 2H2O, by its characteristic bands at ca. 1136, 1008, 670, 491 and 414 cm−1,24; no gypsum was detected in other areas. This composition and the absence of a distribution that would be consistent with the presence of white highlights suggest that this is a stray mark.

As mentioned above, in Nude Male, the ink is a rich mid-tone brown to a deep golden color. Iron gall inks are generally a rich black color but over time become the warm brown typically associated with Old Master drawings, a phenomenon not yet completely understood33. Iron gall inks will often migrate creating slight halos around the drawn lines and/or through the thickness of the paper, which accounts for strokes of the Nude Male drawn on the verso to be visible on the recto (Fig. 3a). In some circumstances, iron gall inks can induce the scission of cellulose by acid catalysis and/or through redox reactions, deteriorating the paper support enough to create losses34 but Nude Male remains in very good condition allowing for full appreciation of the drawing process.

The moderately large size drawing Lucretia also has an ink with a golden-brown hue that captures the major outlines of the figure and features, and the crisp delineations of the drapery (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. S6b, SI File). A series of hatch marks are sparingly placed to suggest areas of shadow. This ink rendering is over a preliminary sketch readily visible as gray strokes, which show the initial design, often blocky and angular, that Raphael used to anchor onto the sheet some of the basic proportions of the standing arm-outstretched figure onto the sheet. This is most visible in the figure’s right arm, left leg and foot (Fig. 4a). These first marks, when examined under magnification, were found to have particles with a range of sizes, the result of the artist’s working technique.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1997 (1997.153). a Visible light image, blue arrows point to preliminary sketch in C-based black medium. b Fe (orange) distribution map due to iron gall ink. There are losses to the drawing along the right side and upper left corner; additional paper pieces were added by a conservator at an unknown date before the work entered the Museum’s collection. These additions to the paper support register as dark areas in this map. c Detail of infrared image showing the C-based black medium outline. d Detail of raking infrared image showing the incised lines from transfer.

The ink used by Raphael in Lucretia has the visual appearance of an iron gall. XRF mapping analysis indicated that it is mainly composed of Fe (Fig. 4b); Fe was observed by p-XRF carried out under a He atmosphere in this ink but no Mn, Cu, or Zn, confirming the XRF mapping results. XRF mapping also showed P, Cl, K, and Ca overall (Supplementary Fig. S5b–e, SI File); p-XRF measurements carried out on the support under a He atmosphere revealed Al, Si, and S, in addition to P, Cl, K and Ca, while Raman analysis identified CaCO3 by its strong band at ca. 1086 cm−1 24 (Supplementary Fig. S5f, SI File), indicating the presence of a preparatory layer applied to the paper. The identification of Al, Si, P, S, Cl, and K by XRF indicates that components other than CaCO3 are present in the preparatory layer. For a full identification of its composition, X-ray diffraction analysis is necessary.

Infrared imaging indicated that the gray drawing medium in Lucretia absorbs radiation in the 830–1100 nm range (Fig. 4c), and Raman analysis of this material gave bands at ca. 1330 and 1570 cm−1 characteristic of an amorphous C-based black such as charcoal and lamp black35,36 (Supplementary Fig. S1e, SI File). On the verso, in the area of the standing figure, there is a field of friable black medium (Fig. 5a), evidence that this drawing was used as a template for transfer. This medium also showed the broad Raman bands typical of an amorphous C-based black (Supplementary Fig. S1f, SI File). This method of transfer, calco, entailed placing the drawing face up on top of the surface to which the design was to be transferred and tracing it with a stylus23, causing the black media on the verso to transfer to the new substrate. This was one of several methods employed by artists of this period to copy drawings, and it leaves strong incised marks on the surface of the original drawing as it did in Lucretia (Fig. 4d). The incised lines follow some but not all the ink lines and do not have the fluidity of the drawn lines, suggesting this was done after the drawing was completed (Supplementary Fig. S6, SI File). Among these drawn lines and incisions, a prominent watermark with a motif of ladder in a shield with a star was detected (Fig. 5b, c). This design is closest to nos. 5926, 5927, 5932, and 5933 in Briquet37 (https://briquet-online.at/5926; https://briquet-online.at/5927; https://briquet-online.at/5932; https://briquet-online.at/5933; accessed 07/24/2025). The discussion of the watermark is beyond the scope of this article.

On the verso of Small Head, lines in an amorphous C-based black medium (Fig. 2e, f), as determined by Raman spectroscopy, were observed. These lines roughly follow yet do not align with the red chalk on the recto drawing (Supplementary Fig. S3c, SI File) and are in proximity with a series of incised lines (Fig. 2c).

Metalpoint

Metalpoint drawings may be executed with a variety of soft metals and alloys, such as Ag, Pb, Sn, Cu, Pb-Sn alloys, and Au, though the latter is rare. For most metalpoints, except for Pb which is the softest, the paper substrate needs to be prepared with some kind of thin ground to add roughness or ‘tooth’ to its surface. This allows the artist to make marks with the stylus while also conferring enough slippage to permit drawing smooth and very fine lines, one of the characteristics that made the medium appealing as a primary drawing. As metalpoint can be used to draw with great precision it was a preferred medium for working through small and precise details1,38.

In Madonna and Child (recto) and Nude Male (verso), XRF mapping showed the presence of Ca overall and in situ Raman spectroscopy analysis of areas with no drawing media on the recto and verso gave spectra with similar main features in the 100–700 cm−1 and 900–1200 cm−1 spectral ranges (Supplementary Fig. S1g, SI File). In the higher wavenumber range, bands observed at ca. 967 and 1007 cm−1 can be assigned to SO4−2 vibrational modes; and the shoulder at ca. 1086 cm−1 and peak at ca. 1095 cm−1 are consistent with CO3−2 stretching modes39, the latter is within the values reported for dolomite, MgCa(CO3)240. The peak at ca. 967 cm−1 is also within the range of the PO4−3 main band at ca. 927–994 cm−1.39. The spectra obtained likely reflect the presence of a mixture of salts. Perhaps one or more of these salts have more than one cation in their formula; therefore, to firmly identify the material, X-ray diffraction analysis will be necessary. This material is most likely a preparatory layer for what XRF mapping revealed to be a Pb metalpoint drawing in Nude Male (Fig. 3d). While subtle and not visible to the unaided eye, enough of the preparation particulate became lodged in the paper fibers when the sheet was rubbed with the powder, a technique used often in the preparation of parchment38.

In Nude Male, Raphael used the Pb metalpoint as the first medium to sketch out the form and later reinforced the figure outline and areas of shadow with iron gall ink, as discussed above. Overlapping the distribution maps of Fe from the ink and Pb from the metalpoint allowed for a clear visualization of the two distinct sets of lines (Fig. 3c). This practice of combining direct media (one that does not require any preparation or binder, such as metalpoint and chalk) followed by definitive lines of ink, was a common drawing practice. Compounding different media gives artists a wider range of possibilities for mark making; this is part of artistic practices across many media, time periods, and locales and is found extensively in drawings from the Renaissance in Italy1,9. In the case of Male Nude, the metalpoint was used in a first sketch and the darker ink was applied to solidify the form.

IR imaging of Small Head revealed lines in the deepest shadows of the eyes, mouth, and chin (Fig. 2b), which XRF mapping revealed to be Pb metalpoint (Fig. 2d). However, no overall preparatory layer was detected in this drawing. While a preparation was observed in the paper support of Nude Male, Pb metalpoint in principle requires little or no preparation, as mentioned above. Other metalpoint styli such as Au, Ag, and Cu did require robust preparation of the drawing surface with gesso or chalk mixed with an organic binder like glue or gum1,38.

Preparatory layers can be subtle or readily visible as brushstrokes across the paper’s surface as in Perugino’s Kneeling Youth (Fig. 6a). In this drawing, XRF mapping showed the presence of Ca and P overall on the paper substrate (Fig. 6b and Supplementary S7, SI File) and in situ Raman analysis of the paper preparation gave a band at ca. 961 cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. S1h, SI File), characteristic of a phosphate stretching mode36, expected for bone ash as the material is made by grinding calcined animal bones38. A band at ca. 1085 cm−1, due to CaCO3 was also observed in the spectra acquired in the paper support preparation. Bone ash is primarily composed of hydroxyapatite but it may contain some calcite41. In the case of the drawings where the presence of bone ash was observed, it is not possible to state if the CaCO3 detected is a component of the bone ash, if it was mixed with it, or both.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Walter C. Baker, 1971 (1972.118.265). a Visible light image, where the blue arrow indicates the location of the details shown in (d) and (e). b Ca (white) distribution map showing the brushstrokes in the application of the bone ash preparation, where the blue arrow indicates metalpoint stylus incisions in the preparation layer as illustrated in Fig. 8. c Hg (red) distribution map reflecting the use of an amalgamated Ag metalpoint. d Detail of visible light image, showing lines of metalpoint (brown) and of the C-based black medium (black). e Detail of infrared image corresponding to the same area as d, illustrating the black C-based medium and the transparency of the Ag amalgam metalpoint. Close examination of the strokes shows how Perugino manipulated the character of the drawing via the angle and pressure of application.

Visual examination of Kneeling Youth strongly suggests the use of a metalpoint which now appears a light gray/ brown color. The distribution map presented in Fig. 6c indicated that Hg is present in an amalgam metalpoint, but the amalgamated metal was below the detection limit of XRF mapping. Further analysis by p-XRF revealed the presence of Ag confirming that Perugino used a Ag-Hg amalgam stylus (Fig. 7, left). Ag-based metalpoint with minor amounts of Cu, Zn, and Hg have been observed in Renaissance drawings4,9,42, however it is possible that the occurrence of amalgamated Ag has been underreported because of the difficulties involved in identifying it without chemical imaging. The presence of Hg may have other origins, such contamination from the artist’ studio environment.

Left: P-XRF spectra, acquired, respectively, in the spot of drawing medium shown in the upper right corner image (red spectrum), and in an area of the paper substrate without drawing (gray spectrum), revealing the presence of Ag and Hg in the metalpoint. Pb was detected by XRF mapping all over the paper sheet and this result explains the presence of Pb in the p-XRF spectra. Right: Raman spectra representative of those acquired in the black drawing medium identified as black chalk (spectrum a), and in some spots within this mostly black chalk medium, showing the additional presence of a more amorphous C-based black particles (spectrum b). λ0 = 785 nm.

Close examination of the strokes and of the Ca distribution map revealed how Perugino manipulated the character of the drawing via the angle and pressure of the stylus and how this stylus incised the surface in some areas showing the pliability of the preparation layer (Figs. 6b and 8). In other areas, thinner blacker lines are visible, indicating that the artist employed a secondary drawing medium to emphasize specific features of the garment (Fig. 6d). This black medium absorbs IR radiation in the 830–1100 nm range (Fig. 6e) and displays Raman bands at ca. 1309 and 1575 cm−1 (Fig. 7, right, spectrum a). The amalgamated Ag metalpoint is almost completely transparent to IR radiation in the 830–1100 nm range (Fig. 6e). This response has been explained by the formation of Ag corrosion products that transmit IR radiation to a certain extent, particularly Ag2S and with the exception of AgO4.

Photomicrograph acquired using a 360-degree raking light attachment: Hirox AC-1020S. Original magnification: 90×. The location of this image is indicated by a blue arrow in Fig. 6b. Automated focus stacking software was used to create a 3-dimensional heat map and XY chart in micrometers of the area, showing the variable depth caused by the metalpoint stylus incisions in the preparation layer.

In general, C-based black pigments present two broad Raman bands in the 1300–1600 cm−1 range, respectively the graphitic G mode at lower wavenumbers and the D mode, arising from lattice defects, at higher wavenumbers; more amorphous C-based blacks, such as lamp black and charcoal, have broadened D and G bands because of additional vibrational modes associated with defects35,43,44,45,46. The Raman features mentioned for the black drawing medium in Study of a Kneeling Youth are consistent with those reported for black chalk, also called black earth35. Black chalk is a general term used for a friable black medium that produces gray to black lines, visibly distinctive from other black media. The composition of black chalk is quite variable and not always clear, reported as consisting of graphite or defective graphite in association with quartz and other minerals1,47,48. Therefore, Raman bands reported for black chalk reflect a less amorphous material than the more frequently observed lamp and charcoal blacks35. In some spots of the drawing lines, particles of a more amorphous C-based black were detected (Fig. 7, right, spectrum b); visually, these particles appear to be components of the same medium where the black chalk was identified.

An example of a complex drawing made by layering ink and metalpoint is Leonardo da Vinci’s Compositional Sketches for the Virgin Adoring the Christ Child (a detail of the recto is shown in Fig. 9a and the full recto in Fig. 11a). Like many other metalpoint drawings, the paper support is coated with a preparatory layer that in this case has a pink hue due to the presence of red lead (Pb3O4), identified by Raman spectroscopy by its peaks at ca. 122, 150, 224, 313, 390, and 548 cm−1; the particles of red lead are visible when the drawing is examined under magnification (Fig. 10, right). The red lead is mixed with finely divided bone ash, with a characteristic PO43- mode at ca. 961 cm−1; CaCO3, with a main feature at ca. 1086 cm−1,24,36, was also detected in this preparation. The Pb distribution map (Fig. 9b), together with the Ca and P maps due to the bone ash in the preparation (Supplementary Fig. S8b, c, SI File), highlight the application and brushstrokes. Tinting preparations with hues such as pinks, violets, greens, blues, grays, and reds49 expanded the options for the artist in an era when paper colors were restricted to white, off-white, brownish, blue, and dark gray49,50. These preparations changed the texture and performance of the drawing surface but also functioned as a mid-tone to expand the tonal range.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1917 (17.142.1). a Visible light image. b–f Elemental distribution maps acquired in the detail area shown in (a): b Pb (white) distribution due to the presence of red lead coloring the bone ash preparation; c Ag (purple); d Hg (red); e combined Fe and Cu (orange and blue, respectively); f Fe (orange). Ag, Hg, and some Cu are present in the metalpoint; Fe together with some Cu reflect the use of iron gall ink. The white arrows in Figs. (a) and (e) indicate the sketch of two babies in the middle bottom that were executed in metalpoint only, as the medium there contains no Fe.

Left: Raman spectrum acquired in the red pigment particles of the paper preparation, identified as red lead. Weak peaks at ca. 961 and 1086 cm−1 are due, respectively, to bone ash and CO3Ca particles present in the preparatory layer on the paper substrate. λ0 = 785 nm. Right: Raking light photomicrograph showing red lead particles coloring the bone ash preparation. Original magnification: 90×.

Leonardo began this drawing using metalpoint; he built the cluster of robust sketches with moderately thick strokes of gray-brown lines. The group of infants in the central lower area show how readily metalpoint can be used as a sketching tool. Leonardo also employed a long series of looping strokes to create areas of shading in the drapery and architectural elements. The co-location of Ag and Hg in the maps shown in Fig. 9c, d and the Cu distribution in Fig. 9e indicate that the metalpoint is amalgamated Ag, which also contains some Cu. On top of the metalpoint, Leonardo continued to work on the composition with pen-applied iron gall ink, reflected in the Fe distribution map shown in Fig. 9f. This ink has relatively small amounts of Cu (Fig. 9e) and Mn (Supplementary Fig. S9c, SI File), as well. As mentioned above, the combination of artistic media has been widely reported in Italian Renaissance drawings, and in works by Leonardo1,18,51. A comparison of the Ag, Hg, and the combined Cu and Fe distribution maps in Fig. 9 illustrates how the composition of the metalpoint can be discriminated from that of the iron gall ink in some areas. For example, the sketches of the infants in the middle lower region only contain metalpoint, therefore they register in the Ag, Hg, and Cu distributions, but not in the Fe map.

As Leonardo applied iron gall ink, a liquid medium, over the metalpoint, Hg and Ag were likely mobilized in the paper substrate so the distributions of these two elements are not as sharp as that of Fe, for example. This makes it difficult to discriminate some areas from the inspection of the elemental distribution maps only. False color infrared (FCIR) imaging confirmed the use and placement of the iron gall ink in areas where the medium was more liberally applied, which appear red in Fig. 11b. The stronger red response is only seen in areas with multiple layers of iron gall ink, such as in the leg of the central figure. However, where the metalpoint and iron gall ink overlap, lines appear gray showing that the response is dominated by the metalpoint.

a Visible light image, b False-color infrared image, where iron gall ink appears as red in the areas where it was more heavily applied, and metalpoint shows in black. c Photomicrograph showing the heavy iron gall ink application in the area indicated by the blue arrow in (b). Original magnification: 30×.

This technical study of drawings by Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, and Perugino, which until now had only been assessed by visual examination, demonstrates how the integration of non-invasive analytical techniques can enrich our understanding of Renaissance draftsmanship. The imaging, chemical mapping and molecular analysis revealed complex layering strategies and material choices—often invisible to the naked eye—that speak to both the shared conventions and individual preferences of these artists.

Moreover, the analysis confirmed that materials like red chalk and iron gall ink were not only central to compositional development but also offered a range of expressive possibilities, from delicate tonal shading to decisive contouring, across varied supports and preparations. These findings support the view that drawings were not mere preparatory steps but critical arenas of artistic invention and experimentation.

Without the application of advanced imaging and mapping techniques, some of these observations, including the specific use of amalgams in metalpoint and the compositions of the materials in the preparatory surface treatments, would have remained undetected. This research affirms the essential role of scientific analysis in uncovering the material choices of Renaissance artists and offers a model for future studies at the intersection of conservation science and art historical inquiry.

Data availability

The dataset is available on reasonable requests.

References

Bomford, D. et al. Art in the Making. Underdrawings in Renaissance Paintings 38–192 (National Gallery of Art, 2002).

Reiche, I. et al. Spatially resolved synchrotron-induced X-ray fluorescence analyses of metal point drawings and their mysterious inscriptions. Spectrochim. Acta B 59, 1657–1662 (2004).

Ioele, M., Sodo, A., Casanova Municchia, A., Ricci, M. A. & Russo, A. P. Chemical and spectroscopic investigation of the Raphael’s cartoon of the School of Athens from the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana. Appl. Phys. A 122, 1045 (2016).

Tanimoto, S. & Verri, G. A note on the examination of silverpoint drawings by near-infrared reflectography. Stud. Conserv 54, 106–116 (2009).

Dahm, K. The stylus revealed: a metalpoint identification study of fifteenth-and sixteenth-century Italian drawings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Pap. Conservator 28, 75–86 (2004).

Milota, P. et al. PIXE measurements of Renaissance silverpoint drawings at VERA. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B 266, 2279–2285 (2008).

Bescoby, J., Rayner, J. & Tanimoto, S. Dry Drawing Media. Italian Renaissance Drawings. Technical examination and analysis, 39–56 (London: Archetype Publications—The British Museum, 2010).

Donnithorne, A. & Russel, J. in Leonardo da Vinci’s Technical Practice. Paintings, Drawings and Influence (ed. Menu, M.) 267–282 (Hermann Editors, 2014).

Ambers, J., Higgitt, C. & Saunders, D. Italian Renaissance Drawings: Technical Examination and Analysis (Archetype Publications, In Association with the British Museum, 2010).

Donnithorne, A. in Leonardo de Vinci. A Closer Look, 20–31 (Royal Collection Trust, 2019).

Bicchieri, M., Biocca, P., Caliri, C. & Romano, F. P. Complementary MA-XRF and μ-Raman results on two Leonardo da Vinci drawings. X-Ray Spectrom. 50, 401–409 (2021).

Dal Fovo, A., Striova, J., Pampaloni, E. & Fontana, R. Unveiling the Invisible in Uffizi Gallery’s Drawing 8P by Leonardo with Non-Invasive Optical Techniques. Appl. Sci. 11, 7995 (2021).

Quintero Balbas, D., Dal Fovo, A., Montalbano, L., Fontana, R. & Striova, J. Non-invasive contactless analysis of an early drawing by Raffaello Sanzio by means of optical methods. Sci. Rep. 12, 15602 (2022).

Bambach, C. C. Raphael: Sublime Poetry (The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 2026).

Bambach, C. C. Recent Acquisitions, a selection: 1997-1998. Metrop. Mus. Art. Bull. 56, 18 (1998).

Oberhuber, K. Raphael: The Paintings, 46 (Prestel Verlag, 1999).

Bean, J. & Turčić, L. 15th and 16th Century Italian Drawings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 183 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982).

Bambach, C. C. Leonardo Da Vinci, Master Draftsman, 366–370 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003).

Alfeld, M. & Janssens, K. Strategies for processing mega-pixel X-ray fluorescence hyperspectral data: a case study on a version of Caravaggio’s painting Supper at Emmaus. J. Anal. Spectrom. 30, 777–789 (2015).

Mayhew, T. D., Hernandez, S., Anderson, P. L. & Seraphin, S. Natural Red Chalk in Traditional Old Master Drawings. JAIC. 53, 89–115 (2014).

Genestar, C. & Pons, C. Earth pigments in painting: characterisation and differentiation by means of FTIR spectroscopy and SEM-EDS microanalysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 382, 269–274 (2005).

Bikiaris, D. et al. Ochre-differentiation through micro-Raman and micro-FTIR spectroscopies: application on wall paintings at Meteora and Mount Athos, Greece. Spectroch Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 56, 3–18 (2000).

Bambach, C. C. Drawing and Painting in the Italian Renaissance Workshop: Theory and Practice, 1300-1600, 56; 297 (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Burgio, L. & Clark, R. J. H. Library of FT-Raman spectra of pigments, minerals, pigment media and varnishes, and supplement to existing library of Raman spectra of pigments with visible excitation. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 57 https://doi.org/10.1016/s1386-1425(00)00495-9 (2001).

Laurie, A. P. The refractive index of a solid film of linseed oil rise in refractive index with age. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 159, 123–133 (1937).

Gerken, M., Sander, J. & Krekel, C. Visualising iron gall ink underdrawings in sixteenth century paintings in-situ by micro-XRF scanning (MA-XRF) and LED-excited IRR (LEDE-IRR). Herit. Sci. 10, 78 (2022).

Lehner, S. Ink Manufacture, Including Writing, Copying, Lithographic, Marking, Stamping, and Laundry Inks, 15–35 (Scott, Greenwood & Son., 1902).

Mitchell, C. A. & Hepworth, T. C. Inks. In Their Composition and Manufacture. Including Methods of Examination and a Full List of English Patents, 124–135 (Charles Griffin & Co., 1937).

Lehner, S. & Brannt, W. T. The Manufactrure of Ink: Comprising the Raw Materials, and the Preparation of Writing, Copying, and Hektograph Inks, Safety Inks, Inks Extracts and Powders, Colored Inks, Solid Inks, Lithographic Inks and Crayons, 34–60 (H.C. Baird & Co., 1892).

Krekel, C. The Chemistry of Historical Iron Gall Inks. Int. J. Forensic Doc. Exam. 5, 54–58 (1999).

Díaz Hidalgo, R. J. et al. New insights into iron-gall inks through the use of historically accurate reconstructions. Herit. Sci. 6, 63 (2018).

Teixeira, N., Nabais, P., de Freitas, V., Lopes, J. A. & Melo, M. J. In-depth phenolic characterization of iron gall inks by deconstructing representative Iberian recipes. Sci. Rep. 11, 8811 (2021).

Liu, Y., Fearn, T. & Strlič, M. Photodegradation of iron gall ink affected by oxygen, humidity and visible radiation. Dyes Pigments 198, 109947 (2022).

Melo, M. J. et al. Iron-gall inks: a review of their degradation mechanisms and conservation treatments. Herit. Sci. 10, 145 (2022).

Coccato, A., Jehlicka, J., Moens, L. & Vandenabeele, P. Raman spectroscopy for the investigation of carbon-based black pigments. J. Raman Spectrosc. 46, 1003–1015 (2015).

Bell, I. M., Clark, R. J. H. & Gibbs, P. J. Raman spectroscopic library of natural and synthetic pigments (pre~ 1850 AD). Spectrochim. Acta A 53, 2159–2179 (1997).

Briquet, C.-M. S. Les filigranes. Dictionnaire historique des marques du papier dès leur apparition vers 1282 jusqu’en 1600 (Watermarks. A historical dictionary of paper marks from their appearance around 1282 to 1600). Vol. 2, 345 (Alphonse Picard et fils, 1907).

Schenck, K. in Drawing in Silver and Gold: Leonardo to Jasper Johns (eds, Stacey Sell & Hugo Chapman) 9–23 (National Gallery of Art; The British Museum; Princeton University Press, 2015).

Nyquist, R. A., Putzing, C. A. & Leugers, M. A. Infrared and Raman Spectral Atlas of Inorganic Compounds and Organic Salts. Vol. I (Academic Press, 1997).

Griffith, W. P. in The Infrared Spectra of Minerals (ed V.C. Farmer) Ch. 8, 119–135 (Mineralogical Society, 1974).

Morgulis, S. Studies on the chemical composition of bone ash. Journal of Biological Chemistry 93, 455–466 (1931).

Russell, J., Rayner, J. & Bescoby, J. in Drawing in Silver and Gold: Leonardo to Jasper Johns (eds, Stacey Sell & Hugo Chapman) 261–273 (National Gallery of Art, The British Museum and Princeton University Press, 2015).

Tomasini, E. P., Halac, E. B., Reinoso, M., Di Liscia, E. J. & Maier, M. S. Micro-Raman spectroscopy of carbon-based black pigments. J. Raman Spectrosc. 43, 1671–1675 (2012).

Daly, N. S., Sullivan, M., Lee, L. & Trentelman, K. Multivariate analysis of Raman spectra of carbonaceous black drawing media for the in situ identification of historic artist materials. J. Raman Spectrosc. 49, 1497–1506 (2018).

Van der Weerd, J., Smith, G. D., Firth, S. & Clark, R. J. Identification of black pigments on prehistoric Southwest American potsherds by infrared and Raman microscopy. J. Archaeol. Sci. 31, 1429–1437 (2004).

Tuinstra, F. & Koenig, J. L. Raman Spectrum of Graphite. J. Chem. Phys. 53, 1126–1130 (1970).

Winter, J. The Characterization of Pigments Based on Carbon. Stud. Cons. 28, 49–66 (1983).

Eastaugh, N., Walsh, V., Chaplin, T. & Siddall, R. Pigment Compendium. A Dictionary of Historical Pigments, Butterworth-Heinemann (Elsevier, (2004).

Cennini, C. D. A. The Craftman’s Handbook.Translated by Daniel V. Thompson Jr. 9–12 (Dover Publications, 1960).

Hunter, D. Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft, 224 (Dover Publications, 1978).

Bambach, C. C. Leonardo da Vinci Rediscovered, (Yale University Press, 2019).

Acknowledgements

The investigation was prompted by the forthcoming exhibition Raphael: Sublime Poetry, curated by Carmen C. Bambach, that will take place at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from March to June 2026.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization. R.M. performed a comprehensive conservation examination of the works. L.M.R. and R.M. carried out microscopy and multiband imaging, L.M.R. processed and interpreted the imaging data, took the micrographs, and designed all the figures for publication. S.A.C. carried out XRF mapping, point-XRF and Raman spectroscopy measurements, processed and interpreted the data, and contributed with optical microscopy. All authors contributed to writing the text and to drawing overarching conclusions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors declare no financial interests. RM and LMR declare no non-financial competing interests. Silvia A. Centeno is an Associate Editor at npj Heritage Science.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Centeno, S.A., Mustalish, R. & Ramsey, L.M. Materiality and techniques revealed in drawings by Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, and Perugino. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 597 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02175-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02175-y