Abstract

Archeological surveys and excavations indicate that during the Late Neolithic Age, the Linfen Basin featured a multi-tiered settlement hierarchy centered in Taosi. This study focuses on the pottery artifacts in the Linfen Basin, aiming to explore the relationship between pottery production and the development of social complexity in the middle reaches of the Yellow River Basin. We analyzed 109 pottery sherds collected from the Linfen Basin using XRF and inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). This study finds no difference in the chemical composition of pottery clay among the Longshan sites in the Linfen Basin, either diachronically or synchronically. Considering the distribution of clay resources in the Linfen Basin, it is possible that these Longshan communities shared a clay resource near Taosi, which possibly controlled the clay resources. The chemical analysis of pottery clay sherds points to further study of resource acquisition patterns in the development of social complexity in Neolithic China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China’s cultural landscape underwent a major transformation during the Late Neolithic Age. Following the collapse of Neolithic societies in the Yangzi River Basin, the Yellow River Basin emerged as a new social center for political experimentations around 2300 BCE. Zhang Chi summarized notable characteristics of this change as follows: first, the rapid decline of Neolithic centers in the middle and lower Yangzi River regions around ca. 2300 BCE in the Longshan period; second, the rise of societies in the northern part of China, marking a profound change of the prehistoric Chinese cultural landscape; and third, the beginning of “globalization,” which greatly impacted the cultures in the Bronze Age1. Similarly, Li Min2 found that following the decline of Neolithic centers in the Yangzi River Basin, the highland societies emerged as political hotspots during the Late Neolithic Age.

In the widespread reconfiguration of China’s cultural landscape during the Late Neolithic Age, Taosi, located in the Linfen Basin of southern Shanxi province, emerged as a prominent political hotspot in China. Owing to its importance in investigating the development of social complexity in the Neolithic Age in China and its ambiguous relationship with the legendary Hero Yao, the Taosi site has received substantial global attention from archeologists. Through more than 40 years of excavation, the Taosi site has yielded the most extensive Late Neolithic archeological remains in this region3. Taosi emerged as a walled settlement covering 300 ha during the Late Neolithic Age. Archeologists have identified various functional precincts at Taosi, such as the palatial precinct, cemeteries, workshops, and ceremonial areas. Its large-scale and distinct spatial organization makes Taosi the focal point of investigating state formation in early China4.

Although Taosi became the regional center in southern Shanxi during the Longshan period, it did not initially span 300 ha. Taosi’s development underwent three phases. During the early phase of development, around 2300–2100 BCE, Taosi initially spanned approximately 160 ha. Archeologists have uncovered a palatial precinct with several rammed-earth foundations, an elite cemetery, storage zones, and ordinary residential areas. Taosi was extended to 280 ha during the middle phase of development, around 2100–2000 BCE. During this phase, more features such as a palatial precinct, an outer wall enclosure, an elite cemetery, an astronomical observation and sacrificial platform, a workshop for craft production managed by officials, and ordinary residential areas were built. Within the palatial precinct, archeologists have uncovered the largest rammed-earth platform of the Neolithic Age in China (Palace Foundation No. 1), covering approximately 6500 m2, with the largest known single building (Palace D1) constructed on top of it. These findings suggest that Taosi reached its apogee during the middle phase of development. During the later part of development (around 2000–1900 BCE), although the area remained 300 ha, the most important features, such as walls, rammed-earth foundations, and the astronomical observatory, were demolished, suggesting that Taosi was no longer considered the political center in the Linfen Basin. Most high-status graves were damaged or looted during the late phase, suggesting that the collapse of Taosi was likely attributed to political turbulence during this time.

The emergence of Taosi built momentum for the increasing social complexity in southern Shanxi. However, owing to limited data, archeologists could not analyze the settlement patterns to delineate the development of social complexity in southern Shanxi for a long time. In 2009–2010, an archeological survey of the Linfen Basin identified 54 Longshan-period sites contemporaneous with Taosi. The sizes of these sites were categorized into five tiers, from the smallest, ranging <1 ha to 300 ha, the latter representing Taosi. This categorization suggests the existence of a complex, multi-tiered settlement hierarchy centered around Taosi in the Linfen Basin during the Longshan period5. The survey, along with the large amounts of archeological remains from Taosi, provided a detailed overview of the trajectory of increasing social complexity in the middle Yellow River Basin.

An increase in social complexity is often accompanied by the emergence of a labor division and specialized production. Rice argued that craft specialization is consistently associated with the development of social complexity. Taking pottery as an example, she claimed that changes in pottery technology, styles, or decoration were likely related to the change of production modes6,7. She believed that craft specialization is a dynamic adaptation process between nonindustrial societies and the environment rather than a static structural feature. Through this process, the diversity of behaviors and materials involved in extraction and production activities is managed or standardized. In complex societies, this diversity is managed in different ways and to varying degrees.

This study aims to analyze the pottery technology in the Linfen Basin during the Longshan period through scientific testing of ceramics collected from Taosi and the aforementioned 2009–2010 survey. Pottery is the prevalent artifact found at archeological sites. As an artifact closely related to daily life, pottery contains important cultural information and is also a key entry point for archeologists to explore the development of prehistoric complex societies8,9,10. Therefore, analyzing pottery technology may provide insights into the organization of craft production, offering a new perspective on the role of craft production in the development of social complexity in the Linfen Basin. The chaîne opératoire approach, which encompasses a comprehensive study of the production, distribution, usage, and disposal of technologies, was used to analyze pottery production in this study7. The first stage of pottery production––the procurement of raw materials––offers critical insight into the production organization at the outset of chaîne opératoire. The raw materials used for pottery in the Neolithic Age primarily comprised clay and temper, among other constituents. The chemical composition of clay serves as a key indicator of its source, as clay retains geochemical signatures, including chemical composition, isotopic ratios, and mineral structures, from its place of origin11. Therefore, analyzing the composition of clay in pottery is an important approach12,13,14. Major elements such as sodium, magnesium, aluminum, silicon, potassium, calcium, and iron determine clay properties, as well as pottery production techniques. Conversely, trace elements (<0.5% in concentration) are less affected by manufacturing processes, depositional conditions, or weathering, making them useful for identifying the provenance of raw materials15.

Studies have shown that Taosi pottery primarily consists of silica and alumina and that the clay used in pottery production is a common, high-iron, easily fusible clay, suggesting reliance on local raw materials16,17. Using energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence (EDXRF) spectroscopy, Wang et al. found that common household pottery in the Taosi phase likely involved the use of a single clay material, suggesting that a specialized division of labor in clay sourcing was absent in the region18. Among the various techniques of compositional analysis, portable X-ray fluorescent analyzer has been widely and effectively used in pottery research around the world because it facilitates non-destructive testing while enabling the acquisition of large quantities of compositional data from samples in a short period of time. For example, Cristina et al. studied the sources of pottery unearthed from two different archeological sites in Sicily19. Lu et al. studied the pottery manufacture and exchange at the Qixingdun site in Hunan Province, China20. Parviz Holakooei et al. studied the provenance study on the ceramics excavated at the Varzaneh Plain, central Iran21. The above studies have effectively solved some archeological problems. However, XRF is not as accurate and precise as other destructive analytical methods. It is not sufficiently sensitive to detect trace elements, limiting the ability to identify the origins of raw materials in detail22. This underscores the need for a precise source detection method.

Laser ablation inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) has been widely used in pottery analysis owing to its high precision. For example, Eckert et al. used LA-ICP-MS to study the production and distribution of plain pottery in the Samoan archipelago, demonstrating its effectiveness in distinguishing clay sources, even in geologically similar regions23. Similarly, Kennett et al. used this method to analyze Lapita pottery from Fiji, Tonga, and New Ireland, revealing profound elemental differences among similar pottery types produced in different regions24. They found that LA-ICP-MS was an effective tool for tracing the circulation of Lapita pottery both within and between island groups in the Pacific. Therefore, in this study, we combined XRF and LA-ICP-MS methods to identify the sources of raw materials used in pottery in the Linfen Basin of southern Shanxi in the Late Neolithic Age. In fact, some studies have comprehensively used multiple analytical methods to study pottery, solving some archeological problems25,26,27,28,29,30,31.

Methods

Selection of pottery samples

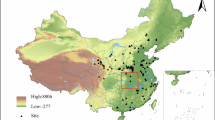

We examined a total of 109 pottery sherds, including 97 sherds collected from 11 Longshan period sites during the aforementioned 2009–2010 survey and 12 sherds from the 2023 excavation of a ceramic production workshop at the Taosi site (Fig. 1). Among the 109 sherds, 67 were sandy-paste pottery sherds and 42 were fine-paste pottery sherds. Most of the sherds were identifiable by the vessel type, including fuzao stoves, hollow-leg li tripods, flat-based hu bottles, small-mouthed shouldered guan jars, and ring-footed guan jars, which are typical utilitarian ceramics of the Taosi culture. Additionally, there are some unidentified pottery sherds. These samples provided insights into the production of utilitarian ceramics across sites within the Linfen Basin. Details of the sherds are shown in ancillary form, and some are shown in Table 1 and Figs. 2 and 3.

The geographical locations of the Taosi site and other sites mentioned in this study (base map converted by ArcGIS 10.3, using free data from the Geospatial Data Cloud, http://www.gscloud.cn). 1. DD Dongduan, 2. BX Beixi, 3. LB Lingbo, 4. XM Xinmin, 5. ZC Zhangcuan, 6. TS Taosi, 7. NC Nanchai, 8. FC Fangcheng, 9. CY Chaoyang, 10. ZZ Zhouzhaung, 11. TC Tingcheng, and 12. YM Yimen.

Chemical composition analysis

We used the XGT-7000 EDXRF spectrometer produced by Horiba Inc. for the chemical composition testing. The detection limits for analyzing samples were based on a 90 s total analysis time (30 s for the high filter,30 s for the low filter, and another 30 s for the main filter) in the soil mode. We tested two available readings from different parts of each piece of pottery. The instrument was calibrated by using the fundamental parameters method designed by the manufacturer. The experiment was conducted in the laboratory of the Archeological Science Center of Sichuan University. We analyzed all 109 samples, mainly testing chemical elements including Na, Mg, Al, Si, K, Ca, Ti, Fe—all expressed as oxides.

In addition, we selected 46 identifiable samples for LA-ICP-MS analysis(Table 1 and Figs. 2 and 3). The trace element contents in all samples were determined using a 193-nm ArF excimer laser system (RESOLution S155-LR, ASI) coupled with an Agilent 7900 ICP-MS system at the State Key Laboratory of Continental Dynamics, Xibei University. The analysis was performed under the following conditions: beam diameter, 80 μm; frequency, 6 Hz; helium flow rate, 0.28 mL/min; and argon flow rate, 1.16 L/min. Each single-point analysis consisted of background collection for 20 s followed by 45 s of ablation for signal collection and 50 s of washing to reduce memory effects. The trace element compositions of the samples were calibrated using reference materials (NIST 610, NIST 612, BCR-2G, and BHVO-2G) without using an internal standard. The Excel-based software ICPMS Data Cal was used for offline selection and integration of background and analyzed signals, time-drift correction, and quantitative calibration of trace element content. The analytical approach followed the procedure described by Bao et al.32.

Results

Analysis of major elements

Eight major elements were identified from the 109 pottery samples: the Al₂O₃ content ranged from 14.2 to 24.3 wt% (mass percentage, same below), Na2O from 0.3 to 2.8 wt%, MgO from 0.1 to 4.1 wt%, SiO2 from 54.5 to 71.4 wt%, K₂O from 2 to 10.3 wt%, CaO from 0.4 to 13.5 wt%, FeO from 3.2 to 8.2 wt%, and TiO₂ from 0.1 to 1.7 wt%.

Li categorized the clay used in pottery production from the Neolithic Age to the Han Dynasty in China into four types based on the composition of major elements in the products33. The first type, ordinary fusible clay, is characterized by low silica, low alumina, and high cosolvent levels. The second type, high-magnesia melting clay, is characterized by low silica, low alumina, and high magnesia levels. The third type, high-alumina refractory clay, is characterized by low silica, high alumina, and low combustion aid levels. The fourth type, high-silica clay, is characterized by high-silica dioxide and low cosolvent levels. Based on this categorization, Wang et al.18 summarized the SiO2, Al2O3, and the average and range of flux content, including oxides such as FeO, Fe2O3, CaO, MgO, K2O, Na2O, and TiO2 (Table 2).

Most of the pottery samples in this study were made from common fusible clay. However, TS1, NC2, CY4, and YM1 samples exhibited high-alumina characteristics, with the Al2O3 contents of 21.06 wt%, 24.37 wt%, 20.51 wt%, and 21.48 wt%, respectively. These samples were likely made from high-alumina refractory clay (Fig. 4). Additionally, three samples—TS9, XM1, and FC5—had relatively high SiO2 content, indicating that they were made from high-silica clay. Most samples had CaO levels below 6 wt%. However, four samples—NC1, NC3, TC2, and TC4—exhibited higher CaO content (9.43 wt%, 13.54 wt%, 6.98 wt%, and 6.95 wt%, respectively). These samples were categorized into two groups on the SiO2–CaO scatter plot (Fig. 5). Although the four samples were likely made from common fusible clay, their relatively high CaO content demonstrated a certain level of uniqueness.

Clay is a type of soil mineral composed mainly of hydrous aluminum silicates, with a high content of silicon and aluminum oxides. Variations in clay types reflect the potter’s choices of clay sources. Clay is abundant on the Earth and is easy to obtain and process. Its defining features include plasticity when wet and high mechanical strength and hardness after high-temperature firing, making it the primary raw material for pottery production16. The late Tertiary red silty clay deposit found beneath Quaternary loess–paleosol sequences, widely distributed in the Loess Plateau34, is characterized by a high carbonate content, with calcium levels usually exceeding those found in Quaternary loess–paleosol sequences35. The Linfen Basin is located at the southern edge of the Loess Plateau, where the predominant soil type is carbonate-rich brown soil. Alluvial carbonate-rich brown soils are distributed on alluvial fans, whereas loess-like and red-yellow carbonate-rich soils are found on secondary terraces36.

The study showed that the soil near the Taosi site can be categorized into high- and low-calcium types16. The CaO content of high-calcium loess can reach up to 11.66%, whereas low-calcium red soil contains <2% CaO. As shown in Fig. 5, the pottery samples analyzed in this study were divided into high- and low-calcium groups based on the CaO content. The CaO content of NC1, NC3, TC2, and TC4 samples was comparable to that of high-calcium loess, indicating that the clay used for manufacturing these items likely originated from high-calcium loess. The remaining samples, with lower CaO contents, were most likely produced using low-calcium red clay.

Major element data were used to determine the provenance of the clay used in pottery from different sites in the Linfen Basin. Figure 6 presents the results of principal component analysis (PCA) of the major element data from pottery samples across sites. The clay varieties used for daily-use pottery across sites were indistinguishable, indicating a common source. However, one discrete point was observed, a li-tripods (TS8) made of high-alumina refractory clay. This pottery sherd became a discrete point due to its elevated aluminum content.

We selected 70 pieces of ceramics that can identify the shape, analyzed their major elements, and made them into Fig. 7. The results show that it is difficult to distinguish the major elements of these ceramic pieces. Figure 7 shows the results of PCA of various types of pottery. However, one discrete point was observed, a li-tripods (TS8) made of high-alumina refractory clay. The sample TS8 will be further explained in the analysis of trace elements later.

Analysis of trace elements

Because PCA of major element data could not distinguish the clay sources, and trace elements provide better information on the place of origin, statistical analysis was performed on trace elements. A total of 52 trace elements were analyzed, among which six elements, S, V, Cr, Zn, Rb, and Sr, had relatively high concentrations and statistical significance. The remaining elements had extremely low concentrations and were not analyzed.

Figure 8 shows the composition of trace elements in pottery samples from different sites. Only one discrete point (TS8) was found, and all other pottery samples across sites remained indistinguishable. These results suggested that the source of pottery raw materials at various sites in the region was the same, consistent with the results of PCA of major elements.

Figure 9 shows the composition of trace elements in various types of pottery samples. The same discrete point, TS8, appears in both scatter plots. TS8 is a li-tripods with a significantly different chemical composition from other samples. From the analysis results of major elements, there is basically no difference between TS8 (li-tripods) and other samples. The analysis results of trace elements showed significant differences between this sample and other samples. In the remaining samples that have undergone trace element detection, the content of V is between 70.2 and 149 ppm, and the V content of TS8 is 1.05 ppm. The Cr content of the remaining samples is between 52.59-115.45ppm, and the TS8 content is 2.32 ppm. The Zn content of the remaining samples is between 67.1-204.63 ppm, and the Zn content of TS8 is 9.98 ppm. The Rb content of the remaining samples ranges from 89.06 to 186.98 ppm, while the TS8 content is 268.33 ppm. The Rb content of the remaining samples is between 111.24 and 505.37 ppm, and the TS8 content is 1098.52 ppm. The results of trace elements indicate that the clay source of TS8 is highly likely to be inconsistent with the other samples. The TS8 device is a fragment, and based on its morphological characteristics, it can be inferred that it is a li-tripods, but it is unknown whether it is a monaural or binaural device. In the late Neolithic Age of China, except for the Linfen Basin, this type of artifact was found in the surrounding areas. Due to the difficulty in identifying the specific form, it cannot be ruled out that TS8 was imported from another location.

Except for TS8, the two scatter plots suggested that the composition of major or trace elements in the pottery samples cannot be distinguished. Based on the composition of major and trace elements, no significant differences were observed in the elemental composition of pottery samples across sites. These findings suggest that the pottery raw materials used across sites in the Linfen Basin originated from the same source, possibly a fixed location for clay procurement.

Discussion

The Taosi culture endured for approximately 400 years and is typically divided into three phases, each with a distinct set of pottery assemblages3. Although the pottery samples examined in this study cover these three phases, their chemical compositions showed no marked differences. Furthermore, no strong correlation was observed between pottery style and function. Three pieces of pottery made of high-silica clay were identified: a small-mouthed, shouldered jar (TS9), a sand-tempered flat-based hu bottle (FC5), and a sand-tempered fuzao stove (XM1), which functioned as a storage vessel, a water-fetching container, and a cooking utensil, respectively. However, no profound correlation was observed between high-silica clay and the functions of pottery vessels. It is noteworthy that four samples (TS1, NC2, CY4, and YM1) exhibited high-alumina characteristics. TS1 and NC2 samples were collected from fuzao stoves, and CY4 and YM1 samples were collected from li tripods, both of which were cooking vessels. These findings suggest that potters had some understanding of the properties of high-alumina clay and made conscious choices when making pottery. The fire resistance of high alumina clay is stronger than that of ordinary clay, which may be the reason why potters use it to make cookware. However, pottery made of high-alumina clay has higher hardness and is more prone to damage, making it unsuitable for everyday use as cookware. So, in the Linfen Basin, the number of cookware made from high alumina clay is relatively small. Therefore, using high alumina clay to make cookware may have been an innovative experiment by potters during the production process, but it was not later promoted.

Based on the composition of major elements, most of the samples were made of common fusible clay, with some containing a high calcium content. Additionally, a small number of pottery sherds were made of high-alumina refractory clay and high-silica clay. Pottery made of high-alumina refractory clay was found at different sites, including the primary center Taosi, the second-tiered settlement Nanchai, and the fourth-tiered settlement Yimen. Similarly, pottery made of high-silica clay was found in both Taosi and the fifth-tiered settlement Xinmin. The use of these two types of ceramic raw materials was not associated with settlement hierarchy, suggesting that technological choices in pottery making were not directly related to settlement hierarchy in the Linfen Basin. Notably, four samples (NC1, NC3, TC2, and TC4) exhibited a high calcium content. These samples were collected from the Nanchai and Tingcheng sites, suggesting that potters at these two sites had unique choices for pottery paste.

Taosi was not culturally insular, it interacted with cultures in different regions. Wang et al. analyzed the chemical composition of exotic cultural artifacts such as gui vessels, grid-patterned sand-tempered jars, and small grid-patterned li tripods from the Taosi site13. Results showed that these artifacts were made of high-alumina clay. According to the data released by Wang et al., the aluminum content of these exotic pottery clays ranges from 21.61% to 26.48%18. In this study, we found that sandy stoves and sandy li tripods made of high-alumina clay were present at several sites across the Linfen Basin, including Taosi, Nanchai, Chaoyang, and Yimen. The aluminum content of these specimens ranges from 20.51 to 24.37%. These findings suggest that the chemical compositions of local and exotic pottery were not different.

Overall, the chemical composition of daily-use pottery from different phases, sites, types, and origins of the Taosi culture cannot be distinguished, suggesting the high consistency and stability of pottery making in the Linfen Basin during the Longshan period. The paste of the 109 pottery sherds showed no obvious difference in chemical composition, suggesting potters in the Linfen Basin might use similar clay sources. It is possible that a specific clay source was shared by these Longshan communities. The distribution of clay resources in the Linfen Basin provides us with a geological background for interpreting these data. The Linfen Basin is located on the southern edge of the Loess Plateau, and loess is widely distributed within the basin. An examination of the relationship between the chemical composition of pottery from Taosi and surrounding environments showed their similarities, suggesting that the clay used for pottery production was primarily collected locally16. According to the research of Wang et al.18, there are differences in the distribution of clay in the Linfen Basin, especially high alumina clay, which is only found in the area where the Taosi site is located. However, pottery made of high alumina clay is not only found at the Taosi site, but also in other sites distant from Taosi, indicating that these sites far from Taosi probably also acquired the clay resources of the high alumina clay near Taosi. The analysis results show that it is difficult to distinguish trace elements between these samples, with only the TS8 sample showing significant differences from other samples. Based on this, it is possible that the local communities in Linfen Basin shared clay from a location near the Taosi site during this period.

Ceramics were not only important for daily lives, but also one of the important markers of social status for the Longshan communities in the Linfen Basin, as shown by the large amounts of ceramic vessels placed in the elite burials at Taosi3. As the most important key material, the acquisition of clay was critical for the success of the Chaǐne Opératoire of ceramic production and the succeeding use. As mentioned above, the chemical analysis of pottery sherds indicates that clay was probably acquired from the resources near Taosi. Considering the social importance of ceramics for the Longshan communities in the Linfen Basin, it is possible that the clay resource was managed under a central regulatory system or even controlled by Taosi. Archeological findings have demonstrated the existence of resource control at the Taosi site. The high-value objects, such as drums made of alligator skins, alligator bone plates, cinnabar, and precious woods, were most often found in large burials or high-status architectures3. Thus, as suggested by the chemical analysis, the possibility of clay resource control cannot be ruled out. Taosi stood out as the center of the multi-level settlement hierarchy in the Linfen Basin for nearly 400 years, but the chemical analysis shows the consistent use of clay resources since the early phase of Taosi, indicating the clay resource near Taosi was possibly shared, or even controlled, from the beginning of the Taosi culture. As Rice argues, economic specialization often accompanies the development of social complexity, the allocation and management of resources are important aspects of it6. The wide share of clay resources among the communities was possibly the result of social complexity and economic specialization in the Linfen Basin during the Longshan period. This study, of course, cannot answer all the questions about the complex relationships between pottery production and social evolution in this region. More nuanced studies are needed.

Moreover, it is worth noting that Li et al. conducted chemical analysis on Qujialing culture pottery unearthed from the Zoumaling site and suggest that the acquisition of clay resource did not differ based on household status37. The analysis of the chemical composition of pottery unearthed from the Zoumaling site by Wu et al. showed that there was no difference in the chemical composition of the pottery, and the clay always came from the same location. Even though households inside Zoumaling walled town had different social statuses or wealth, there was little difference in obtaining pottery clay raw materials among them38. In another study, Yao et al. conducted an analysis of chemical composition on the pottery in elite and civilian graves in the Liangzhu site complex, and found that the raw materials for the two types of pottery were acquired from different sources. They believed that elites were probably involved in pottery production and controlled production of specific pottery as a means of sustaining their status39. In this article, the study shows that there is no difference in the chemical composition of pottery among the Longshan sites in the Linfen Basin, indicating that they might share a clay resource near the Taosi site. It is possible that Taosi controlled the clay resources in the Linfen Basin during the Longshan period. These different ways of obtaining clay reflect the diverse ways of resource acquisition and distribution in the development of social complexity in the Neolithic Age of China.

This article still has limitations. Most of the materials we use are obtained through archeological surveys, and some samples are obtained through archeological excavations. Due to the limited number of pottery samples obtained from archeological surveys at most sites, it is currently not possible to obtain more samples for testing through archeological excavations. Therefore, there is an imbalance in the number of samples between different sites, which may lead to biases in interpretations. More excavations and data are needed to solve this problem. Moreover, a more comprehensive analysis of the interrelationship between politico-economic development and pottery production is also needed in the future.

Data availability

All data supporting the conclusions of this study are available for download in the Supplementary Information.

References

Zhang, C. Longshan-Erlitou: changes in the pattern of prehistoric chinese culture and the formation of globalization in the Bronze Age. Cult. Relics 6, 50–59 (2017). (In Chinese).

Li, M. The social turning point of the Longshan era: political experiments and the expansion of interactive networks. In Longshan Culture and Early Civilization: Proceedings of the Zhangqiu Satellite Conference at the 22nd International Congress of Historical Sciences (eds Shandong University Cultural Heritage Research Institute, Zhangqiu Municipal Bureau of Culture, Radio, Film and Information Technology) 16—31 (Cultural Relics Press, 2017). (In Chinese).

CASS (Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academic of Social Sciences), Linfen Municipal Culture Relics Bureau, Shanxi Province. Taosi Site in Xiangfen: Report on Archaeological Excavations in 1978–1985 (Cultural Relics Press, 2015). (In Chinese).

He, N. Taosi: The Starting Point of the Formation of the Core of Chinese Civilization (Shanghai Chinese Classics Publishing House, 2022). (In Chinese).

He, N. Archaeological practice and theoretical achievements of the settlement form of Taosi site group in 2010. Commun. Anc. Civiliz. Res. Cent. Chin. Acad. Soc. Sci. 21, 1–12 (2011). (In Chinese).

Rice, P. M. Evolution of specialized pottery production: a trial model. Curr. Anthropol. 22, 219–240 (1981).

Rice, P. M. Pottery Analisis—A Sourcebook (University of Chicago Press, 1987).

Costin, C. L. Craft production systems. In Archaeology at the millennium: a sourcebook (Feinman, G. M. & Price, T. D.) 273–327 (Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2001).

Underhill, A. P. Craft Production and Social Change in Northern China (Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2002).

Drennan, R. D., Peterson, C. E., Lu, X. & Li, T. Hongshan households and communities in Neolithic northeastern China. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 47, 50–71 (2017).

Olin, J. S. et al. Elemental Compositions of Spanish and Spanish-Colonial Majolica Ceramics in the Identification of Provenance, Vol. 171 (American Chemical Society, Washington D.C., 1978).

Finley, J. B. et al. Compositional analysis of intermountain Ware pottery manufacturing areas in western Wyoming, USA. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 18, 587–595 (2018).

Gjesfjeld, E. The compositional analysis of hunter-gatherer pottery from the Kuril Islands. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 17, 1025–1034 (2018).

Glascock, M. D. et al. Compositional characterization of pottery and clays from Guam by NAA. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 50, 14098 (2023).

Peacock, D. P. S. The scientific analysis of ancient ceramics: a review. World Archaeol. 1, 375–389 (1970).

CASS (Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academic of Social Sciences). Testing and analysis of ceramic fragments from Taosi site in Xiangfen, Shanxi Province. Archaeology 2,176–188 (1993). (In Chinese).

Wang, X. & Wang, X. Analysis of the composition of pottery soil at the taosi site in Xiangfen, Shanxi Province. Archaeol. Cult. Relics 2, 106–111 (2013). (In Chinese).

Wang, X., He, N. & Dai, X. EDXRF analysis of clay raw materials for pottery making in the late Neolithic Age in Jinnan area. J. Natl. Mus. China 5, 146–160 (2020). (In Chinese).

Belfiore, C. M. et al. In situ XRF investigations to unravel the provenance area of Corinthian ware from excavations in Milazzo (Mylai) and Lipari (Lipára). Herit. Sci. 10, 32 (2022).

Lu, Q. et al. Pottery manufacture and exchange at the Qixingdun site in Hunan Province, China. npj. Herit. Sci. 13, 308 (2025).

Holakooei, P. et al. A provenance study on the ceramics excavated at the Varzaneh Plain, central Iran. Herit. Sci. 12, 416 (2024).

Odelli, E. et al. Pottery production and trades in Tamil Nadu region: new insights from Alagankulam and Keeladi excavation sites. Herit. Sci. 8, 56 (2020).

Eckert, S. L. & James, W. D. Investigating the production and distribution of plain ware pottery in the Samoan archipelago with laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS). J. Archaeol. Sci. Vol. 38, 2155–2170 (2011).

Kennett, D. J. et al. Geochemical Characterization of lapita pottery via inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (ICP–MS). Archaeometry Vol. 46, 35–46 (2004).

Chen, Z. et al. Verifying the feasibility of using Hand-Held X-ray fluorescence spectrometer to analyze Linqing brick: evaluation of the influencing factors and assessing reliability. Herit. Sci. 8, 92 (2020).

Kloužková, A. et al. Multi-methodical study of early modern age archaeological glazed ceramics from Prague. Herit. Sci. 8, 82 (2020).

LeMoine, J. & Halperin, C. T. Comparing INAA and pXRF analytical methods for ceramics: a case study with Classic Maya wares. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 36, 102819 (2021).

Tsoupra, A. et al. A multi-analytical characterization of fourteenth to eighteenth century pottery from the Kongo kingdom, Central Africa. Sci. Rep. 12, 9943 (2022).

Li, T. et al. Surface treatment of red painted and slipped wares in the middle Yangtze River valley of Late Neolithic China: multi-analytical case analysis. Herit. Sci. 10, 188 (2022).

Lu et al. A preliminary analysis of pottery from the Dantu site, Shandong, China: perspectives from petrography and WD-XRF. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 47, 103710 (2023).

Choi, H. et al. A study on the characteristics of the excavated pottery in Hanseong and Sabi periods of the Baekje Kingdom (South Korea): mineralogical, chemical and spectroscopic analysis. Herit. Sci. 12, 236 (2024).

Bao, Z. et al. Simultaneous determination of trace elements and lead isotopes in fused silicate rock powders using a boron nitride vessel and fsLA-(MC)-ICP-MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 31, 1012–1022 (2016).

Li, W. Research on Ancient Chinese Pottery Craftsmanship, 329–342 (Science Press,1996). (In Chinese).

Peng, H. & Wu, Z. Preliminary exploration into the characteristics and distribution patterns of red beds. J. Sun Yat Sen. Univ. 5, 109–113 (2003). (In Chinese).

Chen, Y., Chen, J. & Liu, L. Chemical composition and chemical weathering characteristics of late tertiary red clay in Xifeng, Gansu Province. J. Geomech. 2, 167–175 (2001).(In Chinese).

Linfen Local Chronicles Compilation Committee. Linfen City Chronicles (Zhonghua Book Company, 2014). (In Chinese).

Li, T., Yao, S., He, L., Yu, X. & Shan, S. Compositional study of household ceremic assemblages from a Late Neolithic (5300–4500cal.BP) earthen walled-town in the middle Yangtze River valley of China. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 39, 103159 (2021).

Wu, J. et al. Chemical insights into pottery production and use at Neolithic Zoumaling earthen-walled town in China. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 115 (2025).

Yao, S. et al. Composition analysis of pottery from the Jiangjiashan and Bianjiashan cemeteries in Liangzhu Ancient City, China. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 231 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This project is funded by Major Special Project of the Ministry of Education for the Construction of Independent Knowledge System in Chinese Archeology (grant no. 2024JZDZ055), the National Social Science Fund of China (grant no. 22& ZD242), and the Fundamental Research funds for Central Universities at Sichuan University (grant no. scuhistory2024-1). We thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their insightful comments, suggestions and assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.H.: writing—review and editing, writing—original draft, project administration, methodology, data curation, and conceptualization. L.Z.: methodology and data curation. Q.L.: methodology and data curation. N.H.: resources and data curation. J.G.: resources and data curation. T.S.: writing—review and editing, writing—original draft, project administration, methodology, data curation, funding acquisiton, and conceptualization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, L., Zou, L., Li, Q. et al. Ceramic manufacturing and development of social complexity in the Neolithic Linfen Basin, China. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 596 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02178-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02178-9