Abstract

This paper presents the multi-analytical study of the pictorial ensemble in Room 3 of the Domus of Salvius in Carthago Nova with the aim of deepening knowledge of the technical processes and recipes used in the city’s pictorial ensembles. Dating from the late 1st—early 2nd century, it is one of the best preserved and most comprehensive examples in the city. Thin section and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of the mortars confirmed the use of locally sourced materials, noting the use of different extraction points between the beginning of the 1st century AD and the 2nd century AD. Pigment analysis with Raman spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) identified the painting techniques and the chromatic palette, highlighting the use of cinnabar, only documented until the middle of the 1st century AD. The results indicate the use of a recipe for applying pigments not previously observed on the peninsula.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carthago Nova is one of the most notable Hispanic Roman cities. In recent years, it has yielded a vast array of archaeological finds that have enabled scholars to trace its evolution from the Late Republic to the Early Empire1. Topics in numerous publications have included domestic environments2,3,4 and architecture, such as the city’s forum5 and theatre6. Within the broad spectrum of preserved materials and structures, the extensive and varied preservation of wall paintings stands out. This diversity has allowed researchers to trace their implantation and evolution from the 2nd century BCE to the 3rd century CE through Italic and local workshops7,8,9, making Carthago Nova a centre for the study of this form of art, along with Augusta Emerita and Bilbilis.

Although the city’s wall paintings have been extensively studied from an archaeological and compositional perspective, archaeometry analysis has been limited to examples of the III style10 and partial findings from the 2nd century11. This is due to a lack of technical and material data, which particularly affects the archaeometric study of painting in the provinces.

In this regard, it is especially in recent years that a large number of studies have been carried out focusing on the archaeometric analysis of pigments and mortars, allowing us to go beyond compositional studies and compare the data provided by classical sources (Vitruvius, De Architectura, 7.3.5–7, 7.6 and 7.7–14; Pliny the Elder, 35 and 36.176) with archaeological reality12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. As a result of this dynamic, two different approaches have emerged: on the one hand, those focused on the exhaustive study of the production process in specific contexts. These are particularly relevant in sites that are exceptionally well preserved, with most of this work being carried out in Campania20,21,22. On the other hand, studies focused on comparative analysis between sites on a micro and macro scale and from a diachronic point of view. These have made it possible to identify the existence of recipes for the manufacture and preparation of mortar, as well as for the mixing and application of pigments, through which workshops can be identified, favouring a closer approximation of fragmentary productions in other areas of Italy and the provinces of Gaul and Hispania23,24,25,26.

Based on this methodological approach and the issues affecting the largely fragmentary paintings of Carthago Nova, the analysis carried out in the entire room 3 of the Domus of Salvius aims to expand the line of research focused on characterising the paintings of Carthago Nova from an archaeometric perspective. The data obtained makes it possible to establish a comparison with studies already carried out in the city, while also allowing changes and continuities to be determined with respect to productions from the first and second centuries. The case of Salvius is particularly relevant in this regard, as it is one of the few examples preserved in its entirety in its primary context, allowing for a reading of its entire elevation and enabling the fragments analysed to be reliably located within the compositional scheme. In addition, the results allow us to delve deeper into the transitional period between the 1st and 2nd centuries (when Hispania witnessed a compositional transformation), with the goal of reconstructing the technical and compositional evolution of the city’s workshops from the Late Republic to the Middle Empire.

Regarding the archaeological context, the Domus of Salvius is on plot no. 2 of PERI CA-4, now known as the University District of Cartagena, between Alto Street and Don Matías Street. The area includes several dwellings that bear witness to the significant urban changes of the late Republican and Augustan eras, making PERI CA-4 one of the city’s foremost districts, despite its distance from the forum or theatre, though it was close to the amphitheatre27,28 (Fig. 1).

Because of its morphology, the dwelling falls within the typology of an atrium and peristyle domus, with 10 rooms partially or totally preserved (Fig. 2). The south wing rooms 2, 3, and 4 are the best preserved, while rooms 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 in the east wing are in a poor state; looting and alterations after the domus was apparently abandoned have made it difficult to determine their function. The south wing rooms open onto an ambulatory around the peristyle, as do rooms 6 and 8 in the east wing. Although it has been suggested that it was built during the Augustan period, the first study of the domus, which identified materials in the cocciopesto from an upper floor, indicates a date between 10−15 AD. We cannot, therefore, rule out the possibility that it was constructed during the Tiberian period29. Moreover, the incised decorations between rooms 2, 3, and 4 are likely post-Augustan, the workshop likely dates from the second quarter of the 1st century, and there is an absence of any preserved earlier decoration. In any case, it seems that most of the architectural structure would have been in place from the outset. The domus underwent major renovation towards the last quarter of the 1st century or the beginning of the 2nd century, when some of the decorative programmes (e.g., including those in rooms 2 and 3) recommenced. Room 4 was divided into a narrow corridor (room 11) and two smaller rooms (rooms 12 and 13, the latter with a bread oven).

The dwelling was originally believed to have been abandoned between the end of the 1st century and the beginning of the 2nd century AD. The middle of the 2nd century AD has also been suggested29; this seems more likely, especially if we take two facts into account. On the one hand, the confirmation of a renovation of the second decorative phase of room 2, which must have taken place after the first half of the 2nd century AD. On the other hand, the appearance of fragments from room 3 piled up in room 6 suggests its subsequent reuse.

Regarding the wall painting, Room 3, which measures 5 m wide and 7.8 m long, might have been a biclinium based on the morphology of the mosaic, and the pictorial ensemble is the best preserved in the domus30. The lower section consists of a black and red mottled skirting board on a yellow background measuring 15 cm and an 80 cm-high plinth divided into wide and narrow imitation marble slabs. These are organised into serpentine bands applied with a sponge, a technique common in Hispania between the end of the 1st century and the beginning of the 2nd century31,32. Other slabs are in giallo antico. Both have central inlays alternating between peltae in the narrow ones and lozenges in the wide ones, both in red porphyry. These were used primarily from the second half of the 1st century and throughout the 2nd century AD, almost exclusively for geometric shapes in complex inlays33,34. The structure of the plinth follows the model of complex wall opus sectile imitations35, one of the principal decorative fashions of the Flavian period onwards. It was particularly prevalent in the Antonine−Severan period36,37.

The plinth is bordered above by a 12 cm-high imitation cornice, reminiscent of those found in Second Style complexes38. One fragment reveals a layer of mortar superimposed on the end of the middle section, indicating that each section was built on different days (Fig. 3a).

The middle zone features red panels with yellow openwork borders and black interpanels, with vegetal candelabra. These are surrounded by blue bands characteristic (though not exclusively) of 2nd-century AD productions39,40. The pattern is bordered by a black band providing continuity with the interpanels. The most interesting part of the ornamental programme is the interpanelling, 29 cm wide, which differs on the south and east walls. On the former, they are structured around a crater-like metal vessel, from which a vertical thyrsus-like green stem sprouts, decorated with red lines that cross and ascend, and imitations of pinecones, surrounded by a thin stem with leaves and flowers that ascends in a zigzag pattern.

Two other models are documented on the east wall. The one located at the southern end has a vegetal candelabra sprouting from a metal-like container with a small wading bird in profile. The central trunk of the candelabra consists of green leaves with white strokes, from which branches with leaves sprout on both sides. These are decorated with imitation precious gems, an element previously used during the Second Style41,42, and thereafter during the Third and Fourth Styles in various guises. The candelabra is topped by a crater without handles, also in faux metal, crowned by an only partly preserved motif (perhaps some kind of plant). The central and left side panels repeat the use of a plant candelabra sprouting from a container, which in this case is truncated, conical in shape, and decorated with flowers and red ribbons with geometric motifs arranged in a helical pattern, a model with parallels in the present chronology, between the first and second half of the 1st century AD33,43,44 (Fig. 3b).

In the central section, the candelabra is interrupted by a purple background panel, of which there must have been four, arranged two-by-two on the west and east walls, depicting the seasons. Only one is almost completely preserved: a female figure personifying Spring. The ensemble is completed with the remains of the personifications of Summer, Fall, and Winter (Fig. 3c).

Mortar fragments, which would have served as the base for a cornice, stand above the closure of the middle section. Indeed, three types of mortar from room 3 or adjoining rooms have been identified, albeit not clearly; consequently, they were not included in the present study (Fig. 4).

Methods

Description of the analysed samples

Representative samples were selected from different areas of the compositional scheme and decorative motifs with the aim of answering specific questions, as is the case in any archaeometric study45.

Samples containing as much mortar as possible were analysed to detect the number, thickness, and characteristics of the layers. For their analysis, the layers have been numbered in opposite order to their arrangement, from the paint layer to the wall, as the layers closest to the wall are usually not well preserved or are not complete46. To study pigments and decorative techniques, samples were selected based on their placement in the compositional scheme, differentiating between those used on large and small surfaces of the ensemble. Pigments are usually applied to small surfaces using a secco technique and superimposed on other colours, while those used to decorate large spaces are generally applied using a fresco technique. This differentiation is fundamental when analysing the social hierarchy of spaces. For instance, it was common in the period under study to use richer or more complex patterns and pigments of greater economic value in rooms of higher order47,48,49,50. Finally, six samples were selected to provide an overview of the collection (see Table 1).

Thin section

The mineralogy and textural properties of the samples were studied on 30 μm-thick polished thin sections using transmitted light microscopy at the Laboratorio de Petrología Aplicada (LPA-UA). Photomicrographs were performed using a ZEISS Assioskop petrographic microscope with a USB UI-1490SE digital camera.

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis

X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy enabled the semi-quantitative identification of the composition of the mortars. Spectra were recorded using a wavelength-dispersive sequential spectrometer (Rigaku ZSX Primus IV model) capable of detecting and quantifying chemical elements ranging from beryllium to uranium. The equipment included a medium-frequency X-ray generator with a minimum power output of 4 kW operating at 50 kV and 120 mA. It was fitted with a front-window rhodium anode X-ray tube. Both voltage and current could be adjusted in 1 kV and 1 mA increments, respectively. The system features six selectable analysing crystals (LiF200, Ge, PET, RX25, LIF220, and RX6), chosen according to the wavelength of the target element, and six collimators with apertures ranging from 0.1 mm to 35 mm. The system was equipped with a gas flow proportional counter for light elements and a scintillation detector for heavier ones. Scraped mortar samples were ground in an agate mortar to a particle size suitable for compression into solid pellets.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis

XRD analysis was performed using a Siemens D-5000 diffractometer equipped with a goniometer and an automated data acquisition system (DACO-MP). The radiation source employed was the copper Kα line (λ = 1.54 Å). The device features a nickel filter and a graphite monochromator, operating at a goniometer scanning speed of 1° per minute. Scraped mortar samples were ground in an agate mortar to a fine-grained powder. This was then placed on a plastic sample holder and compressed to achieve a smooth and uniform surface.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra of the mural painting fragments were obtained using a Renishaw Raman spectrometer (InVia Raman Microscope model) coupled to a Leica microscope equipped with various lenses, monochromators, filters, and a CCD detector. Excitation was performed using a 532 nm green laser, and spectra were recorded in the 140–1700 cm−1 range. For each sample, the number of accumulations, exposure time, and laser power were individually adjusted to optimise the signal-to-noise ratio. Spectral data processing, including baseline correction and smoothing, was performed using Peakfit software (ver. 4.11). Samples were obtained by carefully scraping the targeted areas with a spatula, as in situ analysis of the pigments on the fragment was not feasible. Given the cultural and material significance of the fragments, the samples could not be removed from the site for laboratory examination.

Scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS)

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images and EDS spectra were obtained using a JEOL JSM 6300 microscope, operating at 15 kV, with a working distance of 10 mm and a probe current of 3 × 10−10 A. Due to the requirement for high-vacuum conditions, the samples were limited to a maximum of 3 cm. The instrument is equipped with a secondary electron (SE) detector, which provides detailed topographic images of the sample surface, and a backscattered electron (BSE) detector, which aids in identifying elements within internal layers based on differences in electron absorption relating to atomic number. These differences produce greyscale contrast, which was assessed using the EDS detector. SEM-EDS analysis was performed on cross-sectional samples to investigate the painting technique employed by the artisans. This approach involved examining the pigment layers and their elemental distribution to provide information relevant to the application method.

Results

Mortar analysis

Macroscopic study of the mortar has revealed an approximate thickness of between 3 and 3.5 cm, with only two layers visible. However, a microscopic study has made it possible to differentiate clearly four layers that, due to their thickness or similar composition, are not visible to the naked eye. The layers have therefore been defined using French terminology (Coutelas, 2021) as finishing layer (A) for the first (known as intonachino in Italian terminology), and preparatory layers for the next three (called intonaco/arricio/rinzaffo), identified as B (1st preparatory layer), C (2nd preparatory layer) and D (3rd preparatory layer) (Fig. 5). Thin section of the aggregate and binder has been applied to the mortar in fragment F2 for petrographic analysis, as it is the most complete of all. This selection of a single fragment for the thin section, in addition to preserving all of the mortar, is also based on the fact that all of the fragments, with the exception of sample 6, too small to make a thin section, and sample 1, from which it was not possible to extract mortar samples because it was consolidated, belong to the east wall of the room. The final layer varied in thickness between 30 and 150 μm and contained a low concentration of grains or aggregate, primarily calcite and quartz (Fig. 5.1–2). Most grains were angular and did not exceed 100 μm in size. The binder consists of micritic lime rich in clays and oxides.

1–2. Upper part of the sample with the finishing layer (A) and first preparatory layer (B). 3–4 Boundary between first (B) and second (C) preparatory layers 5. The boundary between the second (C) and third (D) preparatory layers. 6 Detail of reaction edge in calcareous aggregate (sparitic limestone). NP parallel nicols, NX crossed nicols, Bi bioclast, Frs sedimentary rock fragment, Frv volcanic rock fragment, Li calcareous granule (lime lump).

The first preparatory layer was ~0.9 cm to 1 cm thick, with a binder-to-aggregate ratio of 2–3:1 and aggregate grains around 0.5 mm in size. The latter varied in composition and size, consisting primarily of metamorphic rock (marble, quartzite, and schist) and sedimentary rock (limestone; Fig. 5.1–6). Minor components included opaque quartz grains and ceramic fragments (inorganic additives). The clast size varied from 25 to 500 μm, with abundant subangular to subrounded grains. The size distribution (grading) of the clasts was poor, and no preferential orientation was observed. The binder consisted mainly of microcrystalline calcium carbonate (calcite, or micritic limestone). Its texture and density ranged from homogeneous to heterogeneous, with a tendency to be lumpy. Recognisable lime lumps of varying size (0.2 mm–1 mm) were present (fig. 5.3–4), and reaction rims were conspicuous around calcareous fragments. Clay and iron oxide content were low ( < 5%); porosity was relatively low and predominantly vacuolar (50–250 μm).

The second layer was approximately 1 cm thick, with a granular texture, a binder-to-aggregate ratio of approximately 1:2, and aggregate grains around 0.5 mm in size. The aggregate consisted of fragments of metamorphic rock (marble, quartzite, schist) and sedimentary rock (limestone), with minor amounts of volcanic rock fragments, quartz grains, and opaque particles (Fig. 5.3–5). Ceramic fragments (inorganic additives) were also present. Clast sizes varied significantly (up to 5 mm), with a predominance of subangular grains. The clast size distribution was poor, lacking a preferred orientation. The binder was primarily microcrystalline calcium carbonate (calcite, or micritic limestone) with a homogeneous to heterogeneous texture, often appearing lumpy. Lime lumps varied in size from 0.2 mm to 1 mm, and reaction rims around calcareous fragments were conspicuous. Clay and iron oxide content were low ( < 5%); porosity was relatively low and predominantly vacuolar (25–300 μm).

The third layer was ~1–1.5 cm thick and had a grainy texture and a binder-to-aggregate ratio of approximately 1:2 to 1:3. Aggregate size averaged 0.6 cm. Aggregates consisted mainly of sedimentary rock fragments (limestone and dolomite) and metamorphic rock fragments (marble, quartzite, phyllite, slate, and schist). Minor components included quartz, feldspar, and opaque grains. Ceramic fragments (inorganic additives) were more abundant than in the upper layers. Clast sizes varied widely (25 μm–6 mm), with abundant subangular grains. Clast size distribution was poor, with no preferred orientation. The binder consisted primarily of microcrystalline calcium carbonate (calcite, or micritic lime), with texture and density varying from homogeneous to heterogeneous, and often exhibiting a lumpy appearance. Lime lumps (0.2–1 mm) were identified, sometimes with a lumpy texture, and reaction rims around calcareous fragments were common (Fig. 5.6). Clay and iron oxide content was low ( < 5%); porosity was mostly vacuolar (50–250 μm), with fissures surrounding the aggregate and granules, likely enlarged through dissolution (Table 2).

X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy determined and quantified the chemical elements of the mortars (Table 3 and S1). In each case, the primary element in the mortars was calcium (Ca), with percentages ranging between approximately 50% and 65%, followed by silicon (Si), whose percentages vary between 20% and 30%. Minor elements included aluminium (Al) at 6%–7%, iron (Fe) at 4%–6%, potassium (K) at 1%–1.5%, and sulphur (S), with values ranging from 0.3% to 0.9%.

The mortars were then subjected to XRD analysis to identify their crystalline components. Figure 6 shows the diffractograms of mortars from fragments F1 and F6. (Diffractograms of the other fragments are similar to that of F1 and are therefore not shown.) In each case, the most intense reflections are attributed to calcite (CaCO3, JCPDS No. 05-0586) and quartz (α-SiO2, JCPDS No. 46-1045), which is consistent with the data obtained by XRF. Other components included gypsum (gypsum hydrate, CaSO₄·2H₂O); muscovite (KAl₂(AlSi₃O₁₀)(OH)₂), a silicate from the mica family; anorthite (CaAl₂Si₂O₈, a plagioclase from the feldspar family); and kaolinite (Al₂Si₂O₅(OH)₄), a hydrated aluminium silicate formed primarily by the decomposition of feldspathic rocks. These latter components come from ceramic fragments that were likely added to the mortar to modify its properties51,52. Fragment F6, a different component replaced: dolomite (CaMg(CO₃)₂), a mixed calcium and magnesium carbonate commonly mixed with calcite in many limestone deposits53.

Pigment analysis

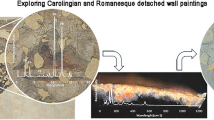

Raman spectroscopy identified the pigments used to create the decorative motifs on the mural painting fragments stored in the Municipal Archaeological Museum of Cartagena. Six fragments were examined (see Table 1). Samples were collected by scraping the desired areas with a spatula. The macroscopic colours included white, red, yellow, blue, green, and black. Each pigment was analysed at multiple points (minimum of three) using micro-Raman spectroscopy, obtaining similar results with only minor variations observed in peak intensities.

White appeared in fragments F1 and F3 (Fig. 7). Both spectra were characterised by a strong signal at 1085–1086 cm−1, accompanied by other less intense bands at 277–280 cm−1 and 151–155 cm−1, indicating the presence of calcite54,55. In Roman mural paintings, lime played a fundamental role not only as a binder (the fresco technique) but also as a white pigment. It was used for technical and economic reasons. Unlike other more expensive mineral whites (e.g., lead white), lime was inexpensive, abundant, and compatible with the fresco technique, as it reacted with atmospheric carbon dioxide to form an insoluble and durable layer of calcium carbonate. This ensured the longevity of the paintings, even in humid environments or when exposed to the elements.

Although classical sources such as Pliny the Elder more frequently mentioned melinum (a white earth from the island of Melos) or cerussa (lead white)56, archaeological evidence suggests that lime was the predominant white pigment in many murals. It served aesthetic and structural functions, providing brightness and contrast. Its presence in Roman mural painting attests to the technical mastery of the artisans, as evidenced by their ability to incorporate inexpensive pigments into compositions of great beauty and complexity.

Black, or a very dark shade close to black, appeared in samples F1, F3, and F4. Figure 8 shows that the Raman spectra of these black areas were similar. Two intense and broad bands, centred around 1600 cm−1 and 1350 cm−1, were observed; these may be attributed to the presence of carbon.

When carbon is present as hexagonal graphite, its Raman spectrum shows a single band at 1582 cm−1, which in the present case appeared near 1600 cm−1. This band corresponds to the G band, which is related to the tensile vibration of carbon–carbon bonds within the aromatic ring plane, with E₂g symmetry57. However, the presence of disordered sp²-hybridised carbon modifies the spectrum, causing a broadening of the G band and the appearance of a new band at 1350 cm⁻¹, called the D band, which lacks a definitive assignment. The exact wavenumber at which this band appears depends on the laser wavelength used. Additionally, the intensity of these bands varies depending on the type of carbon, the degree of disorder, the crystal orientation relative to the laser, and other experimental measurement conditions58. In the present case, the spectra showed a small signal at 1086 cm−1, which may be attributed to the presence of calcite.

Charcoal was one of the most widely used materials because it was abundant, cheap, and easy to prepare. It was produced through the incomplete combustion of plant materials under low-oxygen conditions, a process that produced different varieties of black depending on the source material59. Two types of carbon black were used. Charcoal black (carbon black) was produced by the controlled combustion of wood or plant remains. It was lightweight, finely grained, and had a greyish-black tone. Bone black was produced by calcining animal bones. This pigment contained a significant proportion of phosphates and calcium oxides, giving it a higher density. The presence of phosphate helps differentiate these two pigments in Raman spectroscopy, as phosphate groups produce a strong stretching band around 960 cm−1. The absence of this band in our spectra indicates that the pigment used was carbon black. The calcite band in all three spectra suggests that the fresco technique was used for the paintings under study.

Yellow appeared in all fragments. The Raman spectra (Fig. 9) are consistent with the use of goethite. In all cases, a strong and broad band at 384 cm−1 was observed, along with other less intense bands at 252, 299, 442, 486, and 550 cm−1. These values correspond to those reported by other authors for goethite, an iron oxyhydroxide with the formula α-FeOOH60,61. The band at 384 cm−1 is assigned to the symmetric Fe−O−Fe stretching mode, while the one at 252 cm−1 corresponds to symmetric Fe−O stretching. The bands at 486 and 550 cm−1 may be attributed to asymmetric Fe−OH stretching, and the band at 299 cm−1 to symmetric Fe−OH bending. The number of Raman bands in goethite spectra indicates a high degree of crystallinity, since poorly crystalline samples show fewer signals, though bands near 385 and 299 cm−1 are always present60.

Goethite was widely used in Roman mural painting, above all to achieve earthy yellow tones, golden ochres, and soft browns, depending on the degree of hydration and thermal treatment62,63. This is because goethite, when subjected to heat treatment, dehydrates and transforms into haematite, an iron oxide with a red colour. The resulting red hues vary depending on the degree of dehydration. This pigment, known during antiquity as yellow ochre, was valued for its abundance and its chromatic stability, making it a consistent choice in pictorial decoration.

While Raman spectroscopy can identify this compound, the spectra must be acquired with great care, as heating can lead to dehydration and alter its composition. In particular, the laser heats the irradiated area. To prevent dehydration, spectra must be acquired using very low laser power. The authors of a previous study dealt with this issue by optimising conditions64.

Almost all the spectra generated a sharp and intense signal at 1086 cm−1. This signal, together with other less intense bands at 155, 280, and 712 cm−1, indicated the presence of calcite55. As with the red pigment in fragment F4, this was probably present because the pigment was applied using the fresco technique and, in some cases, might have been mixed with lime to modify the tone. This is consistent with the photographs in Table 1, where the yellow tones vary slightly between fragments.

Red appeared in fragments F1, F2, F3, and F4 (Figs. 10 and 11). The spectra showed a broad and intense band centred around 1320 cm−1, characteristic of haematite60,65 (see Fig. 10). Relatively intense bands near 220, 290, and 405 cm−1, along with weaker bands at higher wavenumbers, indicate that haematite was used61. Haematite was one of the most widely used red pigments in Roman mural painting. It produced a deep, earthy, and opaque red and was highly valued for its durability and its strong adhesion to lime-based plasters.

A common practice involved mixing haematite with lime (in both the fresco and secco techniques). The subsequent compound not only facilitated the integration of the colour with the plaster but also modified the red tone, softening or lightening it depending on the proportion used. Lime acted as a whitening agent, transforming the intense red of the haematite into a more pinkish or orange hue for different decorative or symbolic purposes. Indeed, in the Raman spectrum for fragment F4, the signals of calcite at 1086 and 712 cm−1 are clearly visible, suggesting that calcite was used to soften the red colour (cf. fragments F1 and F3).

By contrast, the Raman spectra for fragments F2, F5, and F6 were completely different (see Fig. 11), featuring a strong band at 254 cm−1 and two additional weaker bands at 282–284 and 340–342 cm−1. These signals are associated with the vibrational modes of the S–Hg bonds in cinnabar, a mercury sulphide66. Cinnabar, known for its intense red hue, was extremely expensive because the processes involved in extracting and preparing it were complex and hazardous.

Blue appeared in fragment F1 only (in the separation band between panel and interpanel; Table 1). Figure 12 shows two intense signals at 440 and 1086 cm−1; these are consistent with the use of Egyptian blue67. The presence of other weaker bands at 1006, 989, 564, 470, 375, 358, 231, and 195 cm−1 confirmed its presence.

Egyptian blue was one of the most valued synthetic pigments in Roman mural painting. Rare in nature, it gave frescoes a special and often luxurious character. It was first produced in ancient Egypt around the third millennium BC, making it the earliest known artificial pigment. Its manufacture involved heating a mixture of silica-rich sand, calcium carbonate, a copper compound (such as malachite or limonite), and a flux like natron or plant ash at temperatures between 800 and 1000 °C. The result was an opaque copper and calcium silicate glass that, once finely ground, yielded the pigment.

The Romans inherited this technical know-how from the Greeks and Hellenised Egyptians, and kept the tradition alive68. They used Egyptian blue not only for its chromatic intensity but also for its stability, because it resisted moisture, light, and ageing better than organic blue pigments (which tended to fade).

Egyptian blue was employed for sky backgrounds, the garments of mythological or divine figures, faux architectural elements, and as a constituent of mixtures that created greenish tones when combined with yellow pigment. It was relatively costly, though it did not reach the price of ultramarine (lapis lazuli), which was practically non-existent in Roman painting because it was so rare.

Green appeared in fragments F3 and F4. In Roman times, green pigment was less common than red, ochre, or white. One of the principal sources was green earth, which consisted of minerals such as glauconite and celadonite; both belong to the phyllosilicate group and exhibit hues ranging from olive green to greyish green, depending on their purity and the methods used to process them. They are subtly different in their chemical composition, morphology, and crystal structure69,70. Their general chemical formula is (K,Na)(Fe³⁺,Al,Mg)₂(Si,Al)₄O₁₀(OH)₂, but they differ primarily in the relative content of aluminium and silicon in the tetrahedral layer. A higher substitution of Al³⁺ by Si⁴⁺ favours the formation of glauconite, while a lower substitution favours celadonite formation. Both often contain impurities such as pyrite and calcite71. Glauconite and celadonite also differ in the green tone they produce: celadonite yields a green with bluish hues, whereas glauconite yields a more yellowish green72.

Raman spectroscopy facilitates the identification of these minerals. Figure 13 displays the Raman spectra corresponding to the green colour in fragments F3 and F4. When analysing the spectral region between 300 and 800 cm−1 which is associated with the vibrations of the SiO₄ tetrahedra, a characteristic band below 600 cm−1 was observed. If this band appears around 590 cm⁻¹, it indicates glauconite; if near 545 cm−1, celadonite57,73. Since the bands in the Raman spectra of fragments F3 and F4 are at 583 and 585 cm−1, respectively, we can confidently state that the green earth used in these samples corresponds to glauconite.

Raman microscopy revealed the presence of blue spots on the green surfaces in various areas (not shown). The Raman spectra corresponding to these blue zones exhibited characteristic bands of Egyptian blue. Mixing Egyptian blue and green earth in Roman mural painting (in the present case, glauconite) was a well-documented practice; our research group has detected it in various locations across Hispania26,74,75.

When Roman artisans combined these pigments, they achieved a rich range of bluish or turquoise greens impossible to obtain with a single pigment. This allowed them to simulate effects such as greens in bright foliage, the colour of water, or transitional sky tones, especially in landscape scenes or painted garden decorations. Beyond the visual effect, this mixture had a solid technical basis, as both pigments were compatible with the fresco technique and stable over time. Green earth, with its silicate structure, and Egyptian blue, also a copper-calcium silicate, share a chemical foundation facilitating their integration into wet plaster without adverse reactions.

Analysis of painting technique

White, yellow, black, blue, and green pigments were applied using the fresco technique, or a variant known as fresco secco or mezzo fresco, which involves applying pigments onto dry plaster suspended in aqueous lime rather than water. In this case, the mechanism for fixing colour on the wall is similar to that of true fresco, as the chemical reaction is the same (i.e., the carbonation of lime).

To identify the painting technique used for pigment application, we conducted a study using SEM coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS). This technique allowed us to conduct a cross-sectional study of the different pigment layers and perform elemental mapping of the chemical components present74,76,77. The presence or absence of calcium would confirm the use of one or other of the above techniques.

Figure 14, which displays the SEM-EDS results for sample F2, shows how the pigments were applied. Over the mortar layer (which is rich in calcium and contains silicon) is an iron-containing layer ~80 µm thick, corresponding to the yellow (goethite) and red (haematite) layers. Calcium is also present in this layer (although in lesser amounts than in the mortar), indicating the use of a fresco technique. Finally, atop the goethite layer is an outer red layer containing iron, calcium, mercury, and sulphur. This is essentially a mixture of haematite and cinnabar; the presence of calcium again suggests a fresco technique was used. Although the observed penetration does not exceed 100 µm, the incorporation of calcium within the pigment layers provides evidence of chemical interaction with the plaster, supporting the proposed painting technique.

Discussion

En lo que respecta al studio del mortero, The XRF and XRD results and the thin-section analysis confirmed the abundance of calcite, quartz, and feldspars in different layers. Unlike the results of other mortars analysed on the peninsula where air lime is used as a binder78, a type of lime that hardens slowly due to the action of CO2 in the air, the layers that make up this group have a matrix of micritic lime, a very fine-grained limestone formed by inorganic chemical precipitation in marine or continental environments with calm waters, which hardens in the presence of air and underwater thanks to the clay impurities (silicates) it contains.

In this regard, although air lime is more suitable for plastering, in the case of room 3 of Salvius’ house, a more impure but more resistant type of lime has been used, probably the local limestone from the Cartagena mountains, composed mainly of limestone and dolomite of Triassic origin, specifically due to its petrographic characteristics, from the ‘roca tabaire’ outcrop79, a porous calcareous sandstone formed by quartz grains and heavily impregnated with iron oxides.

On the other hand, although aggregate is not usually found in the top layer, it is, in our case, composed mainly of quartz. In the three distinct preparation layers, metamorphic rock (marble, quartzite and schist) predominates as aggregate, together with sedimentary rock (limestone) and, to a lesser extent, quartz, opaque materials and ground ceramic, with a difference between the first and third layers with respect to the second, as the latter also contains volcanic rock alongside quartz and ground ceramic. With regard to the use of ground ceramic, we could say that its moisture-proofing properties would combine with the action of micritic lime for the same purpose, and the fact that it is found in the composition of the three preparation layers could confirm its purpose. However, as the volume or proportion of aggregate is much lower compared to metamorphic rocks, it could also be that this contamination occurred when the mixing site was used several times during the building’s decoration process. On the other hand, the abundant presence of marble crystals in all its layers, except for the final one, testifies to the care and high quality of the workmanship, something that can also be seen in the decorative composition of the whole. In the case of the third preparatory layer, the presence of phyllites and dolomites could lead us to the Triassic Alpujárride complex of Peñas Blancas (IGME)80.

The paintings in the Monte Sacro domestic complex have a similarly high quantity of quartz (α-SiO2) and calcite (CaCO3), a lime and sand mortar. However, despite the difference in the predominant use of one aggregate or the other, the fragments in the present study did not contain remains of mollusc shells or bioclasts (unlike at Monte Sacro). We are thus presented with important information, namely that, despite using the same technique to decorate both domus, the craftsmen who decorated Salvius’ did not use the same quarry for raw materials as that of Monte Sacro, whose aggregate and bioclasts came from the Pleistocene levels of Escombreras10. Marble, schists, and limestone (biomicrites and biosparites) are the most common lithic clasts, but dolomites and lithic fragments of igneous (volcanic) origin are also present locally. The presence of materials of volcanic origin also suggests local provenance (e.g., Cabezo Beaza and Cabezo de la Viuda, on the outskirts of Cartagena).

Most of the pigments we identified are consistent with the colour palettes and minerals used in virtually all the pictorial ensembles documented to date, notwithstanding differences in painting techniques. Roman craftsmen combined technical ability, knowledge of materials, and an aesthetic sense. Their methods also reflected the social status of the owners and the cultural tastes of the time. The most commonly used was fresco, which involved directly applying pigment dissolved or suspended in water onto a layer of still-wet stucco. The colours chemically bonded to the wall as the stucco dried, resulting in a durable surface. This required quick and precise execution, as the pigment had to be applied before the stucco dried out. The technique was used in conjunction with others such as tempera (where pigment was applied to an already dry wall, mixed with an organic binder such as animal glue, egg yolk, or fat, which acted as an adhesive) and the more unusual encaustic (which involved mixing pigment with hot wax for wood panel painting). Although tempera or encaustic techniques allowed for more flexibility, these were less durable and more vulnerable to humidity and the passage of time. It was generally used for the execution of the remainder of the decorative motifs, which were smaller in size (e.g., the clasts of the marble imitations, bands and fillets in the middle area, openwork borders on the panels, and those between the panels). Yellow was used to decorate the plinth, specifically in the imitation of giallo antico, and before separating certain plates (fragments F3 and F4). In the middle section, it is applied wet for the backgrounds, acting as a sublayer for the haematite and cinnabar, and wet-dry for the execution of details (e.g., the openwork borders and the decoration of the interpanels).

The green colour in the baseboard, where it was mixed with Egyptian blue, and in the clasts of the serpentine imitation (fragments F3 and F4), has been widely documented in pictorial production. However, we could not determine whether this mixture was an attempt to add brightness and luminosity to the green pigment and improve its adhesion, given that glauconite is a mineral that is difficult to apply81,82,83 or an attempt to falsify malachite, as recorded in classical sources56. In any case, the presence of green pigment in small elements is consistent with studies that have pointed to the use of this mineral for smaller spaces and of celadonite for large surfaces due to their greater ease of application and adhesiveness26,84.

The red pigment was the most variable from a technical standpoint, having been applied in different ways in various locations. Haematite was evident in the imitation of red porphyry on the plinth (fragment F3) and in cinnabar and/or goethite sublayer mixtures on the panels in the middle zone (fragments F1, F2, and F5). Cinnabar must have been used in the ornamentation of the interpanels as well as in the panels themselves, as can be seen in the background of the paintings depicting the seasons (fragment F6). It was perhaps mixed with haematite or calcite, which was not detected; its presence in fragment F4 might have been due to contamination of the brush.

A fresco technique appears to have been used to apply the red obtained from haematite. We could not determine whether it was used in combination with cinnabar in the sample corresponding to the south wall (fragment F1), unlike the east wall panels (fragments F2 and F5), because it did not appear in the Raman analysis, although it might have been lost. Cinnabar mixed with haematite is widely attested both in the execution of large spaces in 1st-century Bilbilis, Asta Regia, and Hispalis, and in small elements85. Taking into account the results of fragments F2 and F5, this suggests that it was also the method of application used in fragment F1. A goethite sublayer was found in the panels preserved in situ during the excavation and in the east wall panel fragments.

Fragment F2 contained a layer of goethite onto which an outer layer of haematite and cinnabar was applied. As we have pointed out, the use of red pigment mixtures, particularly cinnabar (HgS) and haematite (Fe₂O₃), is a practice widely documented in scientific analyses and historical sources, citing a chronologically close example from an Adrianic-era room in the Domus del Celio in Rome86. Hispanic archaeochemical studies have, however, not identified a case where a mixture of haematite and cinnabar has been used in combination with a goethite sublayer, and we have only been able to locate it in a sample from Ephesus, specifically belonging to tavern IV, dated between 17 and 140 AD, although in this case there is also a second ochre sublayer beneath the yellow87. It is more common to find the aforementioned mixture or one of the two pigments, sometimes mixed with minium, placed on a sublayer of goethite, as seen in Sisapo, Augusta Emerita and Bilbilis38,75,85. It is interesting to note that the use of these mixtures is particularly evident in large surface areas dating from the first half to the second half of the 1st century AD, with few examples observed later, such as in the river port of Caesaraugusta or in the Mithraeum house in Mérida85,88. From this point onwards, it seems that the use of cinnabar began to be restricted to small areas and decorative motifs, although there is no evidence of a decline in the Sisapo mines until the end of the 2nd century AD89. A similar situation can be observed in the rest of the western provinces, where, although the use of cinnabar is evident until the end of the 2nd century or the beginning of the 3rd century AD, it is only documented in small areas90,91. There only appears to be some continuity in its use over large areas in the eastern provinces. This is evident from recent analyses carried out on sets from Hanghaus 2 in Ephesus, whose cinnabar was probably related to mines in the Balkans or Turkey87. These data could indicate a change in the dynamics of decorative processes in relation to the transformations in the pictorial programmes themselves that began to be observed towards the end of the 1st century AD.

In the latter instance, the mixing of cinnabar with another pigment was referred to by Pliny the Elder, who observed that this pigment was obtained by mixing lead red (minium/minium secundarium) and red ochre (haematite) to make what is known as sandyx, or by mixing red ochre and sandarac (arsenic sulphide) to obtain syricum34,56. Pliny56 claimed that the latter was used less often than cinnabar (minium) because it was so expensive; sinopis was another option. Only the elite could afford to decorate large surfaces with cinnabar, making it use a clear display of social prestige and economic power. Various studies have addressed this issue; in the present case, the procedure was not an attempt at forgery but a way to cut costs. Painters could reduce the proportion of cinnabar by mixing it with haematite, achieving a visually attractive red tone without using the most expensive material92 and protecting the pigment from degradation23,85,93. Indeed, the use of the mixture for stability and durability has been confirmed, as haematite is more chemically stable than cinnabar, especially when exposed to light, humidity, and pollutants. Its inclusion might have had a stabilising effect, slowing down changes in the cinnabar94.

The need to protect the pigment stems from the fact that direct contact between cinnabar and mortar calcite causes the latter to sulphate, resulting in a darkening of the pigment95. In the present instance, the presence of black spots on some of the fragments of the panels and the interpanel paintings containing cinnabar is evidence of such degradation. This might have been the result of a technical problem with the sublayer or direct exposure to light during the filling of the room, which altered the stoichiometry of the mercury sulphide (regardless of whether it came into contact with the calcite).

Cinnabar tends to darken in certain environmental conditions. Light and humidity play a fundamental role, as do chlorides. Calomel, a mercury (I) chloride mineral (Hg2Cl2), which decomposes in the presence of light or oxidising agents, can contribute to the darkening process96.

Terrapon and Béarat97 showed, as already indicated by ancient sources56,98, that sets painted with cinnabar and preserved in situ in humid and contaminated environments undergo rapid chemical reactions. Such conditions accelerate the darkening of cinnabar. In areas where salt crystallises, this black colour forms a layer as sulphates attack adjacent calcareous materials (e.g., calcium carbonate in mortar); water plays a crucial role in both chemical and biological reactions. The amorphous surface of the altered cinnabar then gives way to visible dark spots, or islands. The blackening process has been observed in collections from the Vesuvian area, which were excavated and exposed to different humidity and lighting conditions. The effects are considered irreversible.

In conclusion, compositional and archaeometric analysis of room 3 of the Domus of Salvius has allowed us to delve deeper into the craft dynamics of wall painting at the peninsular level. We have verified the continued use of technical processes and recipes observed elsewhere in the city (e.g., Monte Sacro). Mortar analysis revealed the use of local materials and combinations of minerals from different sources. Only one of the mortar layers contained substances of volcanic origin; bioclasts and molluscs identified in Monte Sacro mortar were absent in the present case, indicating that mortar from Escombreras (as used in Monte Sacro) was not used in the Domus of Salvius. Our data have, therefore, allowed us to compare results from the Third Pompeian Style productions of Monte Sacro and the Hadrianic period of the Roman theatre.

The presence of cinnabar allows us to extend the chronological horizon of its use. Hitherto, it has only been found in products of the Second and Third Pompeian Styles. Our results open up the possibility (despite it having previously been ruled out by archaeologists and despite the city’s gradual economic decline from the second half of the 1st century) that it was used over a longer period. From a technical point of view, the method of application (cinnabar mixed with haematite and a goethite sublayer) is a novelty in the Spanish context, as only other mixtures or red pigments alone had been documented with or without a yellow sublayer, and it is one of the few examples of this recipe. However, the data provided by studies carried out to date and the recent findings on the paintings of Ephesus could indicate the existence of a kind of ‘family of recipes’ for the application of cinnabar on large surfaces, which does not seem to have developed beyond the Hadrianic period due to its limited use on small surfaces and decorative motifs, except for what has been observed in the eastern part of the empire. The use of cinnabar in the decoration of the panels in the middle area, therefore, highlights Salvius’ considerable economic power.

From a technical perspective, the application of a yellow goethite sublayer and cinnabar−haematite mixture currently constitutes an exception in Spanish painting. Although the three minerals are disproportionately represented in the red background panels, the specific intention behind using this particular mixture is unclear. Feasible explanations include an attempt to reduce expenses and to protect the cinnabar from darkening. The latter may have been the result of sunlight and humidity when the room caved in and silted up. Nevertheless, the use of this mixture, along with green and Egyptian blue earths, denotes a high level of craft knowledge. Finally, although we did not identify any binders, they may have been used for the figures of the stations, and as such would exemplify a technical prowess and pictorial and compositional richness that was in keeping with the significance of the space and the purchasing and social power of its owner.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Noguera Celdrán, J. M. Carthago Nova. In: Roman Cities of Hispania (Ciudades romanas de Hispania) (ed. Nogales Basarrate, T.) 351–364 (L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2021).

Fernández Díaz, A. & Quevedo Sánchez, L. La configuración de la arquitectura doméstica en Carthago Nova desde época tardo-republicana hasta los inicios del bajoimperio. An. Prehist. Arqueol. 23–24, 273–309 (2007).

Gómez Marín, J. et al. Contextos domésticos en Cartagena (siglos III a.C. al IX d.C.): procesos de cambio y continuidad. In: Vivere in urbe (eds. Mateos Cruz, P. & Granados Chiguer, I.) 183–220 (Instituto de Arqueología de Mérida, 2024).

Noguera Celdrán, J. M. et al. (eds.) Tarraco Biennal. Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on Archaeology and the Ancient World: Domus 155–169 (Universitat Rovira i Virgili, 2024).

Noguera Celdrán, J. M., Madrid Balanza, M. J., Velasco Estrada, V., García-Aboal, M. V. & Ruiz de Arbulo, J. El foro deCarthago Nova (Cartagena, España): Informe de las campañas arqueológicas de 2017–2020 y nuevas propuestas deinterpretación). Madr. Mitt. 64, 210–317 (2024). (in Spanish).

Ramallo Asensio, S. F. & Moneo Vallés, J. R. The Roman Theatre of Cartagena (Teatro Romano de Cartagena) (Fundación Cajamurcia, 2009).

Fernández Díaz, A. La pintura mural romana de Carthago Nova (Museo Arqueológico de Murcia, 2008).

Velasco Estrada, V. La pintura romana del siglo III d.C. en Carthago Nova: la habitación 13 del edificio del Atrio. In: Roman painting in Hispania (eds. Fernández Díaz, A. & Castillo Alcántara, G.) 121–131 (Editum, 2020).

Castillo Alcántara, G. & Fernández Díaz, A. La decoración pictórica de la porticus post scaenam del Teatro Romano de Cartagena. In: La porticus post scaenam en la arquitectura teatral romana (eds. Ramallo Asensio, S. & Ruiz Valderas, E.) 155–180 (Editum, 2020).

Castillo Alcántara, G., Fernández Díaz, A., Cosano Hidalgo, D. & Ruiz Arrebola, J. R. A compositional and archaeometric study of the Third Pompeian Style located at the Mons Saturnus of Carthago Nova (Cartagena, Spain). J. Archaeol. Sci: Rep. 46, 103670 (2022).

Fernández Díaz, A. et al. De Gades a Carthago Nova: análisis fisicoquímicos de morteros y restos pictóricos en dos enclaves costeros peninsulares. In: Roman painting in Hispania (eds. Fernández Díaz, A. & Castillo Alcántara, G.) 295–313 (Editum, 2020).

Miriello, D. et al. New compositional data on ancient mortars and plasters from Pompeii (Campania, southern Italy): archaeometric results and considerations about their time evolution. Mater. Charact. 146, 189–203 (2018).

Coutelas, A. Le mortier de chaux dans la peinture murale gallo-romaine: l’apport des analyses à la compréhension d’un patrimoine technique ancien. In: La peinture murale antique (eds. Cavalieri, M. & Tomassini, P.) 149–160 (Quasar, 2021).

Elisabetta, G. & Pizzo, A. Mortars, plasters and pigments—research questions and sampling criteria. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 13 (2021).

Salvadori, M. & Sbrolli, C. Wall paintings through the ages: the Roman period—Republic and early Empire. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 13, 187 (2021).

Dilaria, S. Archeologia e archeometria delle miscele leganti di Aquileia romana e tardoantica (II sec. a.C.–VI sec. d.C.) (Quasar, 2024).

Dilaria, S. et al. High-performing mortar-based materials from the Late Imperial baths of Aquileia: an outstanding example of Roman building tradition in northern Italy. Geoarchaeology 37, 637–657 (2022).

Dilaria, S. et al. Early exploitation of Neapolitan pozzolan (pulvis puteolana) in the Roman theatre of Aquileia, northern Italy. Sci. Rep. 13, 4110 (2023).

Dilaria, S. et al. Production technique and multi-analytical characterization of a paint-plastered ceiling from the Late Antique villa of Negrar (Verona, Italy). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 16, 1–21 (2024).

Varone, A. & Béarat, H. Pittori romani al lavoro: materiali, strumenti, tecniche. In: Roman wall painting: materials, techniques, analysis and conservation (eds. Béarat, H. et al.) 199–214 (Institute of Mineralogy and Petrography, 1997).

Piqué, F. et al. Observations on materials and techniques used in Roman wall paintings of the tablinum, House of the Bicentenary at Herculaneum. In: Beyond Iconography (eds. Lepinski, S. & McFadden, S.) 57–76 (2015).

Miriello, D. et al. Pigments mapping on two mural paintings of the “House of the Garden” in Pompeii (Campania, Italy). Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 21, 257 (2021).

Allag, C. & Grotembril, S. Le rôle des sous-couches. In: La peinture murale antique (eds. Cavalieri, M. & Tomassini, P.) 205–212 (Quasar, 2021).

Dilaria, S. et al. Caratteristiche dei pigmenti e dei tectoria ad Aquileia. In: La peinture murale antique (eds. Cavalieri, M. & Tomassini, P.) 125–148 (Quasar, 2021).

Baragona, A. J., Bauerová, P. & Rodler, A. S. Imperial styles, frontier solutions: Roman wall painting technology in the province of Noricum. In: Conservation and Restoration of Historic Mortars and Masonry Structures (eds. Bokan Bosiljkov, V. et al.) 3–17 (Springer, 2022).

Íñiguez Berrozpe, L., Cosano Hidalgo, D., Coutelas, A., Guiral Pelegrín, C. & Ruiz Arrebola, J. R. Methodology for the identification of Roman pictorial workshops: application to the Second Style sets of the municipium Augusta Bilbilis (Calatayud, Saragossa, Spain). Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 24, 154–179 (2024).

Madrid Balanza, M. J. First advances on the urban evolution of the eastern sector of Carthago Nova, PERI CA-4 / University District (Primeros avances sobre la evolución urbana del sector oriental de Carthago Nova PERI CA-4/barrio universitario). Mastia 3, 31–70 (2004).

Madrid Balanza, M. J. Excavaciones arqueológicas en el PERI CA-4 o Barrio Universitario de Cartagena. In: XVI Conference on Historical Heritage (coords. Collado Espejo, P. E. et al.) 264–266 (Comunidad Autónoma de la Región de Murcia, 2005).

Madrid Balanza, M. J., Celdrán Beltrán, E. & Vidal Nieto, M. La Domus de Salvius. Una casa de época altoimperial en la calle del Alto de Cartagena. Mastia 4, 117–152 (2005).

Castillo Alcántara, G., Fernández Díaz, A. & Madrid Balanza, M. J. La decoración pictórica de la estancia 11 de la Casa de Salvius (Cartagena). Arch. Esp. Arqueol. 96 (2023).

Guiral Pelegrín, C., Íñiguez Berrozpe, L., Justes Floría, J. & Fuchs, M. The pictorial decoration of the Municipium Urbs Victrix Osca (Huesca) (La decoración pictórica del Municipium Urbs Victrix Osca (Huesca)). Veleia 35, 213–239 (2018).

Íñiguez Berrozpe, L., Voltan, E. & Fuchs, M. La decoración pictórica del yacimiento de Iruña-Veleia (Iruña de Oca, Vitoria). Veleia 43 (in Spanish).

Esposito, D. Le officine pittoriche di IV stile a Pompei: dinamiche produttive ed economico-sociali (L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2009).

Becker, H. Pigment nomenclature in the ancient Near East, Greece, and Rome. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 14, 20 (2022).

Thorel, M., Balmelle, C., Eristov, H. & Monier, F. The role of opus sectile imitations in Gallo-Roman wall painting (second half of the 1st century–end of the 3rd century AD) (Le rôle des imitations d’opus sectile dans la peinture murale gallo-romaine (deuxième moitié du Ier siècle–fin du IIIe siècle p.C. Aquitania Suppl. 20, 485–497 (2011).

Loschi, I. Las decoraciones pintadas de Colonia Augusta Firma Astigi (Écija, Sevilla). In: Roman Painting in Hispania (eds. Fernández Díaz, A. & Castillo Alcántara, G.) 237–253 (Editum, 2020).

Fernández Díaz, A. et al. Novedades sobre la gran arquitectura de Carthago Nova y sus ciclos pictóricos. In: Ancient Painting between Local Style and Period Style (ed. Zimmermann, N.) 473–484 (ÖAW, 2014).

Zarzalejos Prieto, M. et al. Caracterización de pigmentos rojos en las pinturas de Sisapo (Ciudad Real, España). In: Ancient Painting between Local Style and Period Style (ed. Zimmermann, N.) 607–614 (ÖAW, 2014).

Guiral Pelegrín, C. et al. En torno a los estilos locales en la pintura romana: el caso de Hispania en el siglo II d.C. In: Ancient Painting between Local Style and Period Style (ed. Zimmermann, N.) 277–288 (ÖAW, 2014).

Castillo Alcántara, G. La decoración pictórica y en relieve de Augusta Emerita (SPAL, Monografías Arqueología, 2025).

Mulliez, M. Le luxe de l’imitation. Les trompe-l’œil de la fin de la République romaine (Collection du Centre Jean Bérard, 2014).

Dubois Pelerín, E. Les décors de parois précieux en Italie au Ier siècle ap. J.-C. Mélanges de l’École française de Rome - Antiquité 1, 103–124. (in French).

Barbet, A. La peinture murale en Gaule romaine (Picard, 2008).

Fernández Díaz, A. & Suárez Escribano, L. Les pintures de la Domus d’Avinyó de Barcelona. In: La Domus d’Avinyó MUHBA 13, 21–56 (2018).

Íñiguez Berrozpe, L. Metodología para el estudio de la pintura mural romana: el conjunto de las musas de Bilbilis (Ausonius Éditions, 2022).

Nimmo, M. Pittura murale: proposta per un glossario (Associazione Giovanni Secco Suardo, 2001).

Wallace-Hadrill, A. The social structure of the Roman house. Pap. Br. Sch. Rome 56, 43–97 (1988).

Allison, P. M. The relationship between wall decoration and room type in Pompeian houses: a case study of the Casa della Caccia Antica. J. Rom. Archaeol. 5, 235–249 (1992).

Allison, P. M. How do we identify the use of space in Roman housing? In: Functional and Spatial Analysis of Wall Painting (ed. Moormann, E.) 1–8 (Peeters, 1993).

Tybout, R. A. Roman wall painting and social significance. J. Rom. Archaeol. 14, 33–56 (2001).

Franquelo, M. et al. Roman ceramics of hydraulic mortars used to build the Mithraeum House of Mérida (Spain). J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 92, 331–335 (2008).

Dilaria, S. et al. Making ancient mortars hydraulic. In: Conservation and Restoration of Historic Mortars and Masonry Structures (eds. Bokan Bosiljkov, V. et al.) 36–52 (Springer, 2022).

Pérez-Alonso, M. et al. Analysis of bulk and inorganic degradation products of stones, mortars and wall paintings by portable Raman microprobe spectroscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 379, 42–50 (2004).

Gunasekaran, S. & Anbalagan, G. Spectroscopic characterization of natural calcite minerals. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 68, 656–664 (2007).

Sun, J., Wu, Z., Cheng, H., Zhang, Z. & Frost, R. L. A Raman spectroscopic comparison of calcite and dolomite. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 117, 158–162 (2014).

Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Books XII–XVI (Historia natural. Libros XII–XVI) (Biblioteca Clásica Gredos 388, 2016).

Wang, Y., Alsmeyer, D. C. & McCreery, R. L. Raman spectroscopy of carbon materials: structural basis of observed spectra. Chem. Mater. 2, 557–563 (1990).

Coccato, A., Jehlička, J., Moens, L. & Vandenabeele, P. Raman spectroscopy for the investigation of carbon-based black pigments. J. Raman Spectrosc. 46, 1003–1015 (2015).

Berrie, B. H. (ed.) Artists’ pigments: a handbook of their history and characteristics, vol. 4 (National Gallery of Art, 2007).

Hanesch, M. Raman spectroscopy of iron oxides and (oxy)hydroxides at low laser power and possible applications in environmental magnetic studies. Geophys. J. Int. 177, 941–948 (2009).

De Faria, D. L. A., Venâncio, Silva, S. & De Oliveira, M. T. Raman microspectroscopy of some iron oxides and oxyhydroxides. J. Raman Spectrosc. 28, 873–878 (1997).

Edwards, H. G. M., De Oliveira, L. F. C., Middleton, P. & Frost, R. L. Romano-British wall-painting fragments: a spectroscopic analysis. Analyst 127, 277–281 (2002).

Aliatis, I. et al. Pigments used in Roman wall paintings in the Vesuvian area. J. Raman Spectrosc. 41, 1537–1542 (2010).

Cosano Hidalgo, D., Mateos Luque, L. D., Jiménez-Sanchidrián, C. & Ruiz Arrebola, J. R. Identification by Raman microspectroscopy of pigments in seated statues found in the Torreparedones Roman archaeological site (Baena, Spain). Microchem. J. 130, 191–197 (2017).

Jubb, A. M. & Allen, H. C. Vibrational spectroscopic characterization of hematite, maghemite, and magnetite thin films produced by vapor deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2, 2804–2812 (2010).

Scheuermann, W. & Ritter, G. J. Raman spectra of cinnabar (HgS), realgar (As₄S₄) and orpiment (As₂S₃). Z. Naturforsch. A 24, 408–411 (1969).

Pagès-Camagna, S., Colinart, S. & Coupry, C. Fabrication processes of archaeological Egyptian blue and green pigments enlightened by Raman microscopy and scanning electron microscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 30, 313–317 (1999).

Lazzarini, L. & Verità, M. First evidence for 1st century AD production of Egyptian blue frit in Roman Italy. J. Archaeol. Sci. 53, 578–585 (2015).

Rafalska-Lasocha, A., Kaszowska, Z., Lasocha, W. & Dziembaj, R. X-ray powder diffraction investigation of green earth pigments. Powder Diffr. 25, 38–45 (2010).

Tóth, E. et al. Submicroscopic accessory minerals overprinting clay mineral REE patterns (celadonite–glauconite group examples). Chem. Geol. 269, 312–328 (2010).

Grissom, C. Green earth. In: Artists’ pigments (ed. Feller, R. L.) vol. 1, 141–167 (Cambridge University Press, 1986).

Moretto, L. M., Orsega, E. F. & Mazzocchin, G. A. Spectroscopic methods for the analysis of celadonite and glauconite in Roman green wall paintings. J. Cult. Herit. 12, 384–391 (2011).

Pérez-Rodríguez, J. L., De Haro, M. C. J., Sigüenza, B. & Martínez-Blanes, J. M. Green pigments of Roman mural paintings from Seville Alcazar. Appl. Clay Sci. 116–117, 211–219 (2015).

Cerrato, E. J. et al. Multi-analytical identification of a painting workshop at the Roman archaeological site of Bilbilis (Saragossa, Spain). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 38, 103108 (2021).

Castillo Alcántara, G., Cosano Hidalgo, D., Fernández Díaz, A. & Ruiz Arrebola, J. R. Archaeological and archaeometric insights into a Roman wall painting assemblage from the Blanes Dump (Mérida). Heritage 7, 2709–2729 (2024).

Cerrato, E. J., Cosano Hidalgo, D., Esquivel, D., Jiménez-Sanchidrián, C. & Ruiz Arrebola, J. R. A multi-analytical study of funerary wall paintings in the Roman necropolis of Camino Viejo de Almodóvar (Córdoba, Spain). Eur. Phys. J. 135, 1–20 (2020).

Cerrato, E. J., Cosano Hidalgo, D., Esquivel, D., Jiménez-Sanchidrián, C. & Ruiz Arrebola, J. R. Spectroscopic analysis of pigments in a wall painting from a high Roman Empire building in Córdoba (Spain) and identification of the application technique. Microchem. J. 168, 106–113 (2021).

Guiral Pelegrín, C. et al. Las pinturas de la domus de Can Cruzate de Iluro (Mataró, Barcelona): estudio técnico y decorativo. Pyrenae 54, 133–158 (2023).

Arana Castillo, R. et al. The “Roca Tabaire” quarries of Canteras (Cartagena, Murcia): geological context and importance as geological and mining heritage (Las canteras de “Roca Tabaire” de Canteras (Cartagena, Murcia): contexto geológico e importancia como patrimonio geológico y minero. Cuad. Mus. Geomin. 2, 75–85 (2003).

Instituto Geológico y Minero de España. Mapa geológico de España a escala 1:50.000 (IGME, 2023).

Aliatis, I. et al. Green pigments of the Pompeian artists’ palette. Spectrochim. A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 73, 532–538 (2009).

Béarat, H. Chemical and mineralogical analyses of Gallo-Roman wall painting from Dietikon, Switzerland. Archaeometry 38, 81–95 (1996).

Piovesan, R., Siddall, R., Mazzoli, C. & Nodari, L. The Temple of Venus (Pompeii): a study of the pigments and painting techniques. J. Archaeol. Sci. 38, 2633–2643 (2011).

Groetembril, S. & Sanyova, J. Les décors à champ vert en Gaule. In: La peinture murale antique (eds. Cavalieri, M. & Tomassini, P.) 161–171 (Quasar, 2021).

Guiral Pelegrín, C. & Íñiguez Berrozpe, L. El cinabrio en la pintura romana de Hispania. In: El “oro rojo” en la Antigüedad (eds. Zarzalejos Prieto, M. et al.) 337–372 (UNED, 2020).

Fermo, P., Piazzalunga, A., De Vos, M. & Andreoli, M. A multi-analytical approach for the study of the pigments used in the wall paintings from a building complex on the Caelian Hill (Rome). Appl. Phys. A 113, 1109–1119 (2013).

Rodler-Rørbo, A. et al. Cinnabar for Roman Ephesus: material quality, processing and provenance. J. Archaeol. Sci. 173, 106122 (2025).

Edreira, M. C., Feliu, M. J., Fernández-Lorenzo, C. & Martín, J. Spectroscopic analysis of Roman wall paintings from Casa del Mitreo in Emerita Augusta, Mérida, Spain. Talanta 59, 1117–1139 (2003).

Zarzalejos Prieto, M. et al. La decadencia urbana de Sisapo-La Bienvenida (Ciudad Real, España). In: Signs of weakness and crisis in the Western cities of the Roman Empire (eds. Andreu, J. & Blanco-Pérez, A.) 83–90 (Franz Steiner Verlag, 2019).

Coupry, C. Analyse physico-chimique des pigments de la maison III. In: Le Clos de la Lombarde à Narbonne (eds. Sabrie, M. & Sabrie, R.) Rev. Archéol. Narbonnaise 27–28, 191–251 (1994).

Béarat, H. & Fuchs, M. Analyses physico-chimiques et peintures murales romaines à Avenches, Bösingen, Dietikon et Vallon. In: Roman wall painting (eds. Béarat, H. et al.) 181–191 (Institute of Mineralogy and Petrography, 1997).

Clarke, J. R. Art in the lives of ordinary Romans (University of California Press, 2006).

Barbet, A. L’emploi des couleurs dans la peinture murale romaine antique. In: Pigments et colorants de l’Antiquité et du Moyen Âge 255–269 (CNRS Éditions, 2002).

Doménech-Carbó, M. T. Novel analytical methods for characterising binding media and protective coatings in artworks. Anal. Chim. Acta 621, 109–139 (2008).

Cotte, M. et al. Blackening of Pompeian cinnabar paintings: X-ray microspectroscopy analysis. Anal. Chem. 78, 7484–7492 (2006).

Neiman, M. K., Balonis, M. & Kakoulli, I. Cinnabar alteration in archaeological wall paintings: an experimental and theoretical approach. Appl. Phys. A 121, 915–938 (2015).

Terrapon, V. & Béarat, H. A study of cinnabar blackening: new approach and treatment perspective. 7th Int. Conf. Sci. Technol. Archaeol. Conserv. 1–11 (2010).

Vitruvius. The ten books on architecture (Los diez libros de arquitectura) (Cícon Ediciones, 1999).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Research Group PAI FQM-346, IQUEMA and the Central Research Support Service (SCAI) of the University of Córdoba for their help with the experimental part. D.C. acknowledges the FEDER funds for Programa Operativo Fondo Social Europeo (FSE) de Andalucía (PP2F_L1_07). The authors are also grateful to Juan Carlos Cañavera Jiménez and David Benavente from the Earth and Environmental Sciences Department of the University of Alicante for their help with the thin section analysis. This research was funded by Grant PP2F_L1_07 funded by FEDER funds for Programa Operativo Fondo Social Europeo (FSE) de Andalucía. This research was also funded by Grant 22085/PI/22 of the Seneca Foundation-Science and Technology Agency of the Region of Murcia and by Grant “La pintura de los espacios públicos de Carthago Nova: caracterización petrográfica, Cartagena- Murcia” of Palarq Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Cosano Hidalgo, D.: methodology, conceptualisation, investigation, experimentation, data collection, writing—original draft, writing—review, editing, validation, visualisation and funding acquisition. Castillo.-Alcántara, G.: Methodology, Conceptualisation, Investigation, Experimentation, Data collection, Writing—original draft, Writing—review, editing, Validation and visualisation. Fernández-Díaz, A; Noguera-Celdrán, J; Ruiz Arrebola, J.R.: conceptualisation, methodology, writing—review, editing and funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cosano Hidalgo, D., Castillo Alcántara, G., Fernández Díaz, A. et al. Archaeometric characterisation of materials and techniques in Roman wall painting: the Domus of Salvius in Cartagena, Spain. npj Herit. Sci. 14, 58 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02198-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02198-5