Abstract

The decorative patterns on bronze jin from the late Shu culture in Southwest China are considered by archaeologists to possibly represent production emblems of specific workshops. This study investigates bronze jins from the Shuangyuan Village Cemetery in Southwest China using the typology, pXRF, and MC-ICP-MS methods. The bronze jin can be categorized into Type Aa-c and B, four types based on their typological characteristics and production emblems. Type Ab and B show significant differences in overall length. All types of bronze jin are high-tin bronzes. The lead sources for Type Ab bronze jin are more diverse compared to those of other types. This research refines the understanding of the workshop-level production differences of technological choices and resource acquisition within the late Shu culture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bronze played a pivotal role in the development of ancient civilizations in the Sichuan Basin in southwestern China. The renowned Sanxingdui site (1117–1015 BC) marked the emergence of the first regional cultural center, signaling the beginning of the Bronze Age in the Chengdu Plain. By the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770–221 BC), the Bronze Age in the Chengdu Plain had entered a new stage, commonly referred to as the late Shu culture. A broad spectrum of bronzes, including weapons, vessels, and tools, have been unearthed in the tombs of the late Shu culture. Key domains of archaeological research comprise typology, alloy composition, metal provenance, and cultural exchanges of late Shu bronze1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Previous research has mainly focused on the bronze weapons and vessels frequently found in the late Shu culture. In contrast, bronze tools have received comparatively limited scholarly attention.

However, the bronze tools unearthed in the tombs of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty in Sichuan are not only abundant but also diverse, especially in the Chengdu region and surrounding areas. These tools reflect a high degree of technological development, evident in their abundance, diverse forms, and complex functions. Although Shu bronze tools have not received the same level of scholarly attention as weapons and ritual vessels, their importance as essential implements in ancient manufacturing, daily life and even ritual norms should not be overlooked.

Given the warm and humid climate and the abundant vegetation in the Sichuan Basin during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty, there was a pressing need to process and utilize natural materials such as wood, bamboo, and thatch for construction, shipbuilding, and tomb building13. The widespread use of bronze tools enhanced labor productivity, promoted the development of production technologies, and facilitated the emergence of specialized handicraft industries. This environmental and economic context underscores the vital role that bronze tools played in both daily life and production activities. Moreover, bronze tools were not merely utilitarian; their presence in burials suggests that they also carried symbolic meanings—as emblems of social power and as material expressions of control over productive resources14. For example, the complete set of bronze tools unearthed in the tombs at Xindu Majia Cemetery in Sichuan reflects both the high status of the burial and the tomb owner's adherence to ritual norms. A systematic study of the bronze tools of late Shu culture can therefore contribute to a more comprehensive and nuanced reconstruction of the bronze production of the ancient people of the late Shu culture.

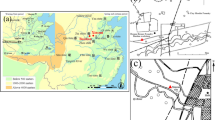

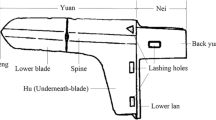

Among these tools, the bronze jin 斤 is especially noteworthy due to its high frequency of appearance, good preservation, and unique emblems, making it an ideal subject for further investigation. While its shape resembles that of a bronze axe (see Fig. 1), it differs in both size and function. The jin typically features a narrower and sharper blade, making it better suited to precision woodworking—particularly for tasks such as smoothing the surface of wooden boards through detailed shaping. In contrast, bronze axes usually have broader blades designed primarily for felling trees. This distinction in function is also supported by historical texts. For example, the Shuowen Jiezi 说文解字, compiled during the Eastern Han Dynasty (100–121 CE), defines the jin as “a tool used for smoothing wood” confirming its role as a specialized instrument for fine carpentry work.

Archaeologists have extensively categorized the bronze jin found in tombs of late Shu culture, with a particular emphasis on the evolution of their shapes13. Notably, many bronze jin from the late Shu culture feature casting patterns. According to Jiang and other researchers, the casting patterns and other markings on these tools were likely intended to identify their owners or producers15. Wang Tianyou further pointed out that the patterns cast on the bronze jin differ significantly from the decorative patterns on bronze weapons of the late Shu culture. These patterns of the bronze jin can serve as production emblems rather than being related to the actual usage of the tool16. Therefore, these features of bronze jin artifacts, which may encode information about producers or workshop traditions, provide a valuable entry point for investigating patterns of bronze production and metal resource use.

Building on this important characteristic, this study focuses on the bronze jins from Shuangyuan Village Cemetery dated to the Eastern Zhou Dynasty and located in Chengdu City, Sichuan Province, southwestern China. The center coordinates of Shuangyuan Village Cemetery are 104°14'16" E, 30°51'35" N (Fig. 1). 274 tombs were excavated by the staff of Chengdu Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and the Qingbaijiang District Cultural Relics Protection Center from March 2016 to July 2018. A multitude of funerary items, such as pottery, lacquerware, and bronze, were unearthed in the tombs of this cemetery. The tombs of Shuangyuan Village Cemetery cover a broad chronological range, offering valuable material for long-term research on bronze artifacts of the late Shu culture. The cemetery exhibits clear social differentiation, with tombs ranging from high-ranking nobles to commoners. This diversity provides a solid foundation for reconstructing the lives of different social classes in ancient Shu society.

A large number of bronze jin artifacts were unearthed in Shuangyuan Village Cemetery, and these pieces are well preserved and come from clear archaeological contexts. These favorable conditions make this relatively limited but distinctive cemetery an ideal case study. It not only mitigates potential confounding factors like mixed chronological phases and cultural attribute differences, but also provides an appropriate framework for a comprehensive investigation and analysis of the similarities and differences in styles, technologies, and raw materials among various production workshops or craftsmen.

The present study aims to examine whether bronze jin of different types and emblems exhibit significant differences in alloy composition or lead isotope ratios. By integrating the analytical results with typological observations and archaeological background information, we further explore how such differences may relate to the organization of bronze production, resource acquisition strategies, and the broader social structures within late Shu society. Ultimately, this study seeks to shed new light on the bronze, craftsmen, and workshops that shaped the technological landscape of the late Shu culture.

Methods

Component analysis

The bronze jin samples were well preserved; therefore, all analyses were carried out using non-destructive and minimally-destructive methods to ensure the integrity of the artifacts. A Thermo Fisher Niton XL3t 950He portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (pXRF) was used to analyze the alloy composition of bronze jin samples. All the samples were tested after removing the surface corrosion products of the bronzes with a surgical blade. The alloy mode was used. The acquisition time was set to 90 s for the collection of compositional data, with 30 s each for Main, High, and Low filters. Each sample was tested at three points, and the average composition was obtained. The instrument performance was validated and calibrated with the tin-bronze standard (32X SN6). The analytical performance of the pXRF instrument, based on repeated measurements (n = 5) of the tin-bronze standard 32X SN6, is presented in Table 1. The data demonstrate the instrument performance, showing relative errors (δ) of 0.21% for Cu, 6.88% for Sn, and 3.05% for Pb, with coefficients of variation for all major elements generally below 2%.

Lead isotope analysis

The study of isotope ratios of corrosion rinds on copper and copper-alloy archaeological artefacts revealed that these rinds can be used instead of the valuable metal core to provide information relating to the provenance of the ore17,18,19,20. The surfaces of bronze jin samples are covered with green and bluish-green patinas, with minor pitting and localized mineralization. Therefore, corrosion products of bronze jin samples were used for lead isotope ratio analysis in this study. We pretreated our samples following the standard procedure of the Archaeometallurgical Lab in the School of Archaeology and Museology, Peking University21.

Approximately 5 mg of corrosion products were carefully scraped from inconspicuous areas of each bronze jin sample using a surgical blade. The powders were placed in a beaker and dissolved in aqua regia (HNO3·3HCl) under a closed-container system on a heating plate at 80 °C. After complete dissolution, the clear solution was transferred to a volumetric flask and diluted with deionized water to a constant volume of 100 ml. A 25 ml solution was taken for analysis. The Pb content of the solution was determined by ICP-AES at the School of Archaeology and Museology, Peking University. The solution was further diluted to a Pb concentration of ~50 ppb, after which 5 ml of thallium (Tl) standard solution (SRM 997) was added as an internal standard before measurement. Lead isotope ratios were analyzed by MC-ICP-MS (VG-ELEMENTAL) at the School of Earth and Space Sciences of Peking University. In order to ensure the stability and accuracy of the instrument, SRM981, a standard solution for lead isotope testing of American National Bureau of Standards, was used to calibrate the instrument under the identical conditions.

Results

Typology of Shuangyuan bronze jins

In Shuangyuan Village Cemetery, 35 pieces of bronze jin artifacts were unearthed in 32 tombs. Considering the prolonged use and re-working of tools, blade wear is inevitable. To minimize the impact of such wear on the typological analysis, this study prioritized bronze jins with relatively well-preserved blade surfaces. Experimental archaeology indicates that bronze tools, such as hammers, exhibit characteristic signs of wear through use, including the formation of horizontal lines, bending, and fracturing22. These experiments suggest that while moderate use may lead to notching or chipping at the blade edge, the overall contour and morphology of the jin blade remains relatively stable.

Based on the shape of straight socket, Shuangyuan bronze jin can be divided into two types: Type A and B (Fig. 2). The socket portion of bronze jin features a casting pattern, and the head and body of Type A jin are distinctly separated. In contrast, Type B jin lacks any decorative patterns on the socket, and there is no obvious distinction between the socket and the body. Type A jin can be further subdivided into three sub-types based on the pattern on both sides of the socket. Type Aa jin has a right-angle ruler pattern on one side of the socket and two raised lines on the other, with a vertical dot pattern below. Similarly, the socket of Type Ab jin also has a right-angle ruler pattern on one side and two rows of raised ridges on the other; however, it is distinguished by a “v”-shaped pattern below. The socket of Type Ac jin has right-angle ruler patterns on both sides.

Chemical compositions of Shuangyuan bronze jins

This study analyzed 14 bronze jin samples, which encompass all the types of bronze jin classified in the previous section, ensuring the comprehensiveness of the analysis. The chemical compositions are listed in Table 2. Although surface corrosion was removed prior to pXRF analysis, the tin content may still be slightly overestimated due to the inevitable influence of residual corrosion products and subsurface decuprification. This issue has been noted in previous studies, which have demonstrated that tin tends to become enriched in corroded bronze substrate layers. A significant amount of intergranular corrosion, which would result in some tin enrichment even if the artefact was cleaned to a depth where visually sound metal was exposed23. Nevertheless, the overall alloy classification remains reliable, allowing us to preliminarily identify most of the jin samples as lead-tin bronze, and the tin content is high (Sn: 16.7–49.3 wt%, mean = 30.37 wt%; Pb: 1.9–13.4 wt%, mean = 3.85 wt%).

Lead isotope ratios of Shuangyuan bronze jins

The lead isotope ratios of the Shuangyuan bronze jin are presented in Table 3. The results of repeated measurements of the SRM981 standard and the published reference values from Cattin24 are listed in Table 4. The analytical uncertainty (2σ) of the isotope analysis is less than 0.084%. Given that the lead content of most of the samples exceeds 2%, the lead isotope ratios are considered reliable indicators for tracing the provenance of the lead used in the bronzes25,26,27. The 206Pb/204Pb values range from 18.041 to 18.628, the 207Pb/204Pb values from 15.583 to 15.720, and the 208Pb/204Pb values from 38.398 to 39.028. All samples fall within the range of common lead (as opposed to highly radiogenic lead), as indicated by 206Pb/204Pb values below 19.028.

Discussion

Bronze decorative patterns were typically manufactured by specific workshops, which developed consistent stylistic and technical traditions through prolonged practice. For instance, bronze artifacts sharing identical decorative systems generally originated from the same workshop, indicating that decorative patterns standardization correlates closely with production workshops29. Besides, drawing upon the research perspectives of archaeologists of late Shu culture presented earlier, it can be inferred that the shape and pattern of bronze jin may serve as production emblems, with variations in their shapes potentially indicating multiple production workshops. Therefore, this study conducts a further typological analysis and explores whether bronze jins with different shapes and emblems exhibit corresponding differences in alloy composition and lead provenance.

Although bronze jins exhibit relatively simple shapes compared with intricately designed bronze vessels, subtle changes in their shapes may still encapsulate significant cultural and technological information. This is particularly important given that individual workshops may adhere to unique manufacturing standards. Building on this insight, this study not only employs traditional typology methods but also introduces statistical data analysis to more thoroughly explore the diversity in the shapes of bronze jins. Specifically, this study conducted a detailed statistical analysis of all bronze jin artifacts excavated from the Shuangyuan Village Cemetery across four key dimensions: socket width, socket thickness, blade width, and overall length. Violin plots (Fig. 3) visualize the dispersion and central tendency of each characteristic indicator, providing a basis for preliminary assessments of whether significant differences exist among different bronze jin artifacts across these critical dimensions. Notably, although only two instances of Type Aa bronze jin were unearthed in Shuangyuan Village Cemetery, making the data relatively limited, these two samples can represent the shape characteristics of this type of bronze jin from the cemetery during that specific period. The socket width, socket thickness, and blade width numerical distributions are somewhat concentrated, indicating that there are no notable differences across the various bronze jin samples. However, there is a noticeable difference in total length, a critical parameter for evaluating the overall size of bronzes. In particular, Type B jins are shorter in overall length, which might be related to the absence of a distinct socket. Type Ab jins display the greatest variability across the overall length.

The composition data reveal no significant differences in alloy types among the different typological categories of jin. The compositional characteristics of the bronze jin are primarily related to their function. As mentioned earlier, the bronze jin was a type of tool used for woodworking. A similar situation also observed in the bronze si 鐁 for processing wood from the Zhou Dynasty in Hunan Province, with tin content ranging from 21% to 24%30. This suggests that high-tin bronze tools were often employed for woodworking purposes. Experimental studies demonstrate that within the 20–24% tin content range, the hardness of bronze alloys exhibits a significant positive correlation with increased tin content31. The microstructure of high-tin bronzes would have had a greater baseline hardness and were, therefore, more resistant to abrasion from the start of testing22, resulting in superior impact resistance and reduced plastic deformation when interacting with wood. This also indicates that all the craftsmen involved in casting the Shuangyuan bronze jins were aware of the properties of high-tin bronze.

To further investigate whether there are differences and changes of lead materials of jin with different emblems, the lead isotope ratios of jin samples from various emblems were compared across different time periods. This comparison provides insights into the selection and use of lead materials by different production systems or groups of craftsmen, and whether these practices evolved over time. Since the shape of the bronze jin has remained largely unchanged over time, determining the burial date of the tomb offers a feasible approach for dating the jin (Table 2). According to the report of Shuangyuan Village Cemetery, Phase 1 corresponds to the middle to late Spring and Autumn Period (672–477 BC), Phase 2 to the early Warring States Period (476–397 BC), and Phase 3 to the middle Warring States Period (396–377 BC).

The lead isotope data of the bronze jin samples are systematically grouped into two clusters—Group I and Group II—based on the clustering characteristics and the theory of geochemical provinces (Fig. 4). Following the geochemical province theory proposed by Zhu Bingquan32, samples with 206Pb/204Pb ratio greater than 18.3 are classified as Group I, corresponding to the South China Geochemical Province. In contrast, samples with 206Pb/204Pb ratio between 17.5 and 18.2 are designated as Group II, representing the Yangtze Geochemical Province.

Type Aa bronze jins are exclusively found during the middle Spring and Autumn Period and have not been discovered in other regions. At the Shuangyuan Village Cemetery, only two specimens of Type Aa have been unearthed. The lead isotope ratios indicate that this type of bronze jin predominantly utilized Group I lead resources. In contrast, Type Ab jins span three phases and show the widest isotopic range, occurring in both Group I and Group II. This indicates that the workshops producing Type Ab jins had access to a relatively wide range of lead sources. Type Ac jins were present throughout all three phases, and in each phase, the majority of lead isotope ratios consistently fall within the range associated with the South China Geochemical Province. This continuity in raw material sourcing suggests that the production of Type Ac jins was likely carried out by a workshop or group of craftsmen with sustained access to the ore sources from the South China Geochemical Province. Type B jins appear only in Phases 2 and 3, and with the exception of one outlier, all samples fall within Group I. This suggests that the Type B jins were also primarily produced using lead resources from the South China Geochemical Province. Overall, from Phase 1 to Phase 3, Type Aa, Ac, and B jins were primarily produced using lead resources from the South China Geochemical Province. In contrast, Type Ab jins exhibit a wider range of lead sources, with a notable increase in the use of lead from the Yangtze Geochemical Province during Phase 2.

Archaeological evidence from the Shuangyuan Village Cemetery points to interaction networks between the late Shu culture and the cultures of the Yangtze region extending far beyond bronze metallurgy. In addition to the bronze jins, many artifacts unearthed in the Shuangyuan Village Cemetery suggest influence or exchange with the Yangtze region. For example, M154 yielded the nineteen-string lacquered zither (se 瑟) and the double-lobed lacquered ear-cup, both stylistically consistent with artifacts from the Chu culture. Furthermore, high-status burials at the site contained not only typical Chu-style bronze ritual vessels but also Chu-style ceramic imitations of bronze vessels, including jars, gui 簋, zhan 盏, and zunfou 尊缶. The coexistence of these Chu-style artifacts with late Shu bronzes supports the view that the region participated in long-distance exchange networks that transmitted not only raw materials such as lead but also lacquerware, ceramic traditions, and the ritual system. The material evidence aligns with historical records, which document frequent interactions between the late Shu and Chu states, suggesting deep cultural, economic and political interconnections.

Taken together, the typological, compositional, and isotopic evidence presented in this study offers new insights into the organization and complexity of bronze tool production in the late Shu culture. Based on the typological features and production emblems of bronze jin, this research categorizes them into four types. Among them, Type Ab jins exhibit the greatest variability in overall length, while Type B jins are the shortest and show the least variation in overall length. In terms of alloy composition, all types share similar characteristics, consistent with a high-tin bronze standard. This high level of tin content suggests that different workshops shared a common understanding of the functional requirements of bronze jin. From the Spring and Autumn Period to the Warring States Period, Type Ab bronze jins exhibit diversity in resource utilization, including two distinct groups of lead resources (the South China Geochemical Province and the Yangtze Geochemical Province), which suggests broader access to raw materials. Moreover, the craftsmen of the Type Ab jins in the Shu region may have maintained trade exchanges of lead resources with other regions. In contrast, Type Aa, Ac and B bronze jins have mainly utilized lead resources from the South China Geochemical Province, exhibiting a consistent preference and stability in the selection of raw materials. These disparities in lead resource origins likely reflect variations in raw material procurement channels among different production workshops of bronze jin with different production emblems. These findings, therefore, not only reveal the characteristics of typology, composition and raw material source of bronze jins with different emblems and forms, but also offer a preliminary exploration of the relationship between bronze production and workshop organization in the Shu region during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty, while simultaneously providing scientific evidence for the close cultural interactions and material exchange between the late Shu culture and Chu culture.

Data availability

The authors confirm that all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Li, H. C. et al. Fighting and burial: the production of bronze weapons in the Shu state based on a case study of Xinghelu cemetery, Chengdu, China. Herit. Sci. 8, 36 (2020).

Li, H. C. et al. Copper alloy production in the Warring States period (475-221 BCE) of the Shu state: a metallurgical study on copper alloy objects of the Baishoulu cemetery in Chengdu, China. Herit. Sci. 8, 67 (2020).

Li, H. C., Cui, J. F., Zhou, Z. Q. & Zuo, Z. Q. Observations on the Phenomenon of ‘Interethnicity and Common Customs’ in the Perspective of Science and Technology --The Bronze Artifacts of Bashu as an Example. Archaeology 12, 104–115 (2021) (in Chinese) https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=iSoVlldxB1MOqPI_etwm2c-p0-es9KAQOuFIgiqt8xkC63QEkjj9ylIAZksl2zDi0QIj7AsFX9OEKOYRSBy9tuJS_c2_Pq-h4_N4S7CJDznrw8sM4KaAs8majp8tqVNM02SxvTG1pGi1S99Iha4wD51-WlzvGaxlAahwMeSALiAt6jDcmNhe2w==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

Chen, D., Yang, Y. D., Wang, T. Y., Wang, X. T. & Luo, W. G. Imitation or importation: Archaeometallurgical research on bronze dagger-axes from Shuangyuan Village Cemetery of the Shu State in the Eastern Zhou Dynasty. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 40, 103218 (2021).

Wang, X. T., Yang, Y. D., Wang, T. Y., Chen, D. & Luo, W. How can archaeological scientist integrate the typological and stylistic characteristics with scientific results: A case study on bronze spearheads unearthed from the Shuangyuan village, Chengdu city, southwest China. Curr. Anal. Chem. 17, 1044–1053 (2021).

Chen, D., Yang, Y. D., Wang, T. Y., Wang, X. T. & Luo, W. G. Improvement and integration: scientific analyses of willow-leaf shaped bronze swords excavated from the Shuangyuan Village Cemetery, Chengdu, China. Herit. Sci. 10, 92 (2022).

Li, Y. X., Yang, Y. D., Wang, T. Y., Wang, X. T. & Luo, W. G. Cultural exchange and integration: archaeometallurgical case study on underneath-blade bronze dagger-axes from Shuangyuan Village Site in the Eastern Zhou Dynasty. Herit. Sci. 10, 151 (2022).

Wang, X. T., Yang, Y. D., Wang, T. Y. & Luo, W. G. Subdivision of culture and resources: raw material transformation and cultural exchange reflected by bronze poleaxes from the Warring States sites in the Chengdu Plain. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 14, 121 (2022).

Qiu, T., Liu, Z. Y., Li, Y. F., Yan, X. & Li, Y. N. Scientific analysis of bronze objects of the first millennium to the second century BCE excavated from the Jiangkou Site, Pengshan, Sichuan. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 15, 151 (2023).

Wang, X. T., Yang, Y. D., Wang, T. Y. & Luo, W. G. A feast: Indigenous production and interregional exchange reflected by the bronze vessels unearthed from Shuangyuan Village Cemetery in southwestern China. Archaeometry 66, 352–367 (2024).

Wang, X. T., Yang, Y. D., Wang, T. Y. & Luo, W. G. A typology and lead isotope and cultural exchange study on bronze knives from Shuangyuan cemetery, Chengdu City, Southwest China. Curr. Anal. Chem. 20, 637–645 (2024).

Li, Y. X. et al. Analyzing the unique phenomenon of ‘Sword Emphasis’ in Shu culture: a lead isotope perspective on willow-leaf-shaped bronze swords unearthed from the Shuangyuan Village Cemetery in Chengdu. Curr. Anal. Chem. 21, 1–18 (2025).

Huang, X. F. Study on bronze tools in the tombs of the Warring States period in Sichuan. Huaxia Archaeology 04, 72–81 (2002).

Xiang, M. W. Archaeological Perspective on Ba’s and Shu’s Ancient Histories - Focusing on the Graves of Ba-Shu Culture from East Zhou to West Han Periods. (A Dissertation submitted to Jilin University for Doctor Degree, 2017) (in Chinese) https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=iSoVlldxB1OXe8wKJqpphTSf5Kpt7E2QBqSToFVYTtdaK__5_b3gaIITF3FqkffesPrzIpOiSY9ETqwrUl7xKmZJ-WYmgsT_UlIF3olHOqcHdzzwRIITNamkNFE9eVqjGjRQ3c1ppxRyZ1W_zyAHc7rFELO9W675zQNN4c9l-zbq9Xld3W1C0pAJQildt7-6&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

Jiang, Z. H. Analysis on the Changes and Properties of Bashu Symbols. Sichuan Cultural Relics 01, 77–86 (2020) (in Chinese) https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=iSoVlldxB1NpQkuynvCDBH2ANq5oEfI9LGO88uidCNo0pvmk6_7zLnfAo7CfalLGEGjZ6v82D3nL8Mu8TMo9-q41OYW6LJnces_Asem6GAisEKMW75vAKrCN-oaPKnor4bIHlo3Hb0SXbtx0d76T3cNzRHu9lYjMmEsKv0gSsQjmef302wbAOA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

Wang, T. Y. Early Beliefs and Choice of Identification: A Re-investigation of the Symbols of Bashu. Archaeology and Cultural Relics 09, 78–88 (2025) (in Chinese) https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=iSoVlldxB1Mv4UhUjBaa0rXqiVo6tma612VXtcTUYFGUNwX_QMZeVjFrZ5LOzJFrCI9aBmx4a3-x0-0GxDAbeeKx-uzcH8H9YApbIrtzGuOQ4X6x5mEJMojGHfSAeNXDQrYt8CSRMMdqyRSuaVVxrovba660hWS3D3nPcT4VP_SUoQPCYI9L5A==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

Snoek, W., Plimer, I. R. & Reeves, S. Application of Pb isotope geochemistry to the study of the corrosion products of archaeological artefacts to constrain provenance. J. Geochem. Explor. 66, 421–425 (1999).

Chen, K. et al. Hanzhong bronzes and highly radiogenic lead in Shang period China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 101, 131–139 (2019).

Karasiński, J., Bulska, E., Halicz, L., Tupys, A. & Wagner, B. Precise determination of lead isotope ratios by MC-ICP-MS without matrix separation exemplified by unique samples of diverse origin and history. J. Anal. Spectrom. 38, 2468–2476 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. The first discovery of Shang period smelting slags with highly radiogenic lead in Yingcheng and implications for the Shang political economy. J. Archaeol. Sci. 149, 105704 (2023).

Cui, J. F., Lei, Y., Jin, Z. B., Huang, B. L. & Wu, X. H. Lead isotope analysis of tang sancai pottery glazes from gongyi kiln, henan province and huangbao kiln, shaanxi province. Archaeometry 52, 597–604 (2010).

Andrews, M., Polcar, T., Sofaer, J. & Pike, A. W. G. The mechanised testing and sequential wear-analysis of replica Bronze Age palstave blades. Archaeometry 64, 177–192 (2022).

Orfanou, V. & Rehren, T. A (not so) dangerous method: pXRF vs. EPMA-WDS analyses of copper-based artefacts. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 7, 387–397 (2015).

Cattin, F. et al. Provenance of early bronze age metal artefacts in western Switzerland using elemental and lead isotopic compositions and their possible relation with copper minerals of the nearby Valais. J. Archaeol. Sci. 38, 1221–1233 (2011).

Jin, Z. Y. Lead Isotope Archaeology in China. (Press of University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, 2008) (in Chinese)

Wang, Y. J., Wei, G. F., Li, Q., Zheng, X. P. & Wang, D. C. Provenance of Zhou dynasty bronze vessels unearthed from Zongyang County, Anhui province, China: Determined by lead isotopes and trace elements. Herit. Sci. 9, 97 (2021).

Luo, Z. et al. Scientific analysis and research on the warring states bronze mirrors unearthed from Changsha Chu Cemetery, Hunan province, China. Archaeometry 64, 1187–1201 (2022).

Liu, R., Hsu, Y.-K., Pollard, A. M. & Chen, G. A new perspective towards the debate on highly radiogenic lead in Chinese archaeometallurgy. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 13, 33 (2021).

Cao, B. On the Relationship Between Bronzes with Specific Decoration and Production Foundries: Case Studies of Yazhi, Yachou, and Daijiawan Bronzes and Xiaomingtun Bronze Foundry. Archaeology and Cultural Relics 07, 75–81 (2024). (in Chinese) https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=iSoVlldxB1PyTWsToLPQoLR0Kn4CojrzlDbYdDYTznVv7mCIzGePRaPZSNZA9tyw9jwqOUpMSe65fLkP-jjcbIqqgkmC3wrxIf5l1ql-SY8BOgzXO56XgtwA-MDtpOcivb3COZpPOPExeSWoMFih1wsk2cly8_E_G9r6WNv12EvjnqFCQM6lpw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

Ma, J. B. & Wu, X. T. Metal technology and related issues of bronze scrapers of Yue people at Zhou Dynasty unearthed in Hunan Province. Nonferrous Metals (Extractive Metallurgy) 07, 72–76 (2017). (in Chinese).

Nadolski, M. The evaluation of mechanical properties of high-tin bronzes. Arch. Foundry Eng. 17, 127–130 (2017).

Zhu, B. Q. The map of geochemical provinces in China based on Pb isotopes. J. Geochem. Explor. 55, 171–181 (1995).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 20VJXG018 and No. 25CKG018) and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF under Grant Number GZC20251162. We are grateful to anonymous reviewers whose comments greatly improved the quality of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W. and W.L. pretreated the samples, performed the experiments, wrote the main manuscript text and prepared tables and figures. Y.Y. and T.W. provide the samples and archaeological background. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Yang, Y., Wang, T. et al. Typology and lead source diversity of late Shu bronze jin from Shuangyuan village cemetery. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 641 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02202-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02202-y