Abstract

Anchorage is the key technique to ensure the structural stability of earthen sites. However, the traditional anchor often fails to fully utilize the interfacial bond strengths, and may cause cracking damage, and not align with the “minimal intervention” principle. This study proposes an innovative two-section pressure-tension composite (P-T type) anchor. Pull-out tests were conducted to compare the anchoring performance of Tension type, Pressure type, P-T type anchor. The influence of the proportion of pressure section length (PPSL) on failure modes, bearing efficiency, and interfacial stress evolution was investigated. Finally, two improvement strategies of the P-T type anchor are proposed. The results indicate that bearing capacity shows a significant positive linear correlation with PPSL, which can provide superior anchoring forces with reduced anchorage lengths. However, higher PPSL is prone to cause cracking damage. It is therefore necessary to achieve an equilibrium between anchoring forces and site damage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Eurasian Silk Road was one of the main trade routes between ancient China and European countries, driving the continuous economic prosperity of cities along the route. This facilitated the emergence of numerous earthen buildings, which are widely distributed across countries such as China, Pakistan, and Turkey1,2.

However, after centuries of exposure to natural forces such as wind and rain erosion, soluble salt corrosion, freeze-thaw cycles, and earthquakes3, the earthen sites commonly suffer from damages like fissure development4, foundation undercutting5, and strength degradation6,7, which severely compromise their overall integrity and stability. Therefore, urgent and appropriate reinforcement measures are needed to ensure their safety.

Unlike traditional geotechnical engineering, the conservation of heritage sites must adhere to the special principles of “safety first”, “minimal intervention”, and “preservation of the original appearance”8. Traditional steel rebars and other metal anchors9,10,11 present challenges in terms of applicability. The primary reasons are as follows: (a) the significant stiffness difference between steel and earthen materials leads to deformation incompatibility; (b) metal materials are prone to corrosion, resulting in a shorter service life compared to earthen materials; (c) metal anchors require the use of high-strength cement12 or resin-based grouts13 to achieve optimal anchorage performance, but these grouting materials may cause irreversible contamination of the site.

It is important to note that the principle of “minimal intervention” entails not only mitigating damage induced by hole drilling during the anchor installation stage, but also safeguarding the structural integrity of the site body during its service period. In particular, the objective is to avoid cracking of the surrounding soil during the loading-to-failure process. For the installation stage, there are also differences in the required drilling depth for the anchoring system with different anchoring efficiencies under the same bearing capacity design requirements. When the borehole diameter is fixed, the anchoring system with higher load-bearing efficiency often requires a lower drilling depth and can better meet the “minimal intervention” principle. Therefore, finding an anchoring system that offers both higher load-bearing efficiency and minimal structural damage during failure is crucial to current research in earthen sites conservation.

Field investigations reveal that many existing earthen sites extensively employ structural techniques such as round timber ties, branch layers, and natural fiber mixtures in rammed earth14, as shown in Fig. 1. The sites that incorporate these structural techniques are typically better preserved than purely rammed earth sites, thus strongly validating their effectiveness in enhancing the structural stability. Furthermore, earthen sites usually have low moisture content in arid regions, so the natural plant-based materials have coexisted with the rammed earth for thousands of years without showing significant deterioration, and still maintain a certain level of tensile strength, demonstrating their good compatibility with earthen sites.

In light of this, scholars have developed various new types of wooden-based anchors for earthen sites, such as Carbon fiber-ribbed bamboo anchors15, Variable-diameter waxwood anchors16, and Bamboo-steel cable composite anchors17, along with their accompanying ecologically modified grouts18,19,20,21. These anchors have been widely applied in the reinforcement of earthen sites using full-length bonded anchoring technology.

However, studies have shown that for the full-length bonded tension type (T-type) anchors, regardless of the grouting material used, the failure mode primarily manifests as slippage at the rod–grout (R-G) interface22, necessitating deeper drilled holes to achieve their maximum load-bearing capacity. Additionally, the anchoring interface stress distribution of T-type anchors is significantly uneven, with high-stress zones concentrated near the loading end (front end) of the anchor and rapidly decaying towards the anchored end (back end)15. This indicates that the bonding strength of the anchoring interface in deep areas is difficult to fully utilize, and the anchoring system has a critical load-bearing limit.

For pressure-type (P-type) anchoring systems, the load is directly transferred to the bearing plate, and the failure mode primarily manifests as slippage at the grout-soil (G-S) interface23. Since the grout near the back end of the anchor often bears significant pressure, the shear inflation and Poisson effect become pronounced, which may cause severe cracking damage to the anchored structure itself24,25, making it difficult to meet the “minimal intervention” principle, despite its load-bearing capacity being much greater than that of the T-type anchors.

As the conservation needs for large-scale earthen sites like city walls, beacon towers, and bearing platforms continue to grow, developing new types of anchors that combine high load-bearing capacity, minimal site damage, and good material compatibility has become a key focus in earthen site anchoring research.

In response to these requirements, a typical single-section pressure-tension (P-T) composite wooden anchor for earthen sites has been developed26,27. This anchor is still full-length bonded with grout. The key difference is the addition of a load-bearing body at the back end of the anchor, which more effectively utilizes the compressive strength of the grout, thereby significantly enhancing its load-bearing capacity. However, when the anchoring depth is large, a conical slurry will form in front of the bearing body and then generate significant expansive pressure on the surrounding soil. In geotechnical applications, tension-compression composite anchors also have been successfully applied in reinforced engineering, such as soil slopes28, tunnel rock masses29, and foundation pit anti-floating systems30, further validating their superior load-bearing performance and displacement ductility.

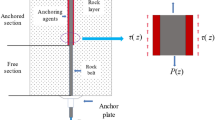

However, for the aforementioned single-section P-T composite anchor26,27, the grout is continuously distributed along the entire length. While this enhances the load-bearing capacity, it also leads to the formation of an integral grout cone in front of the bearing plate upon failure, generating significant radial expansion pressure that may induce cracking in the surrounding soil (a phenomenon similar to that observed in pure P-type anchors). To overcome this inherent limitation, this study proposes a novel two-section wooden-based pressure-tension (P-T type) composite anchor for earthen sites conservation (as shown in Fig. 2). This anchor is based on a waxwood rod, with an annular expansion bearing plate fixed to the middle, and an isolation tube fitted onto the rod in front of the bearing plate. This configuration forms a two-section structure designed to mechanically isolate the tension zone from the pressure zone. The core hypothesis is that by interrupting the continuous transmission of compressive stress in the grout layer in front of the bearing plate, the radial stress distribution can be more effectively controlled, thereby suppressing unfavorable failure modes of the anchor system and restricting failure to interfacial slip—a failure mode more favorable for the conservation of earthen sites. During installation, the gap between the rod and the soil behind the bearing plate is fully grouted, and the force characteristics of this section are similar to those of the T-type anchoring system22. In contrast, only the gap between the isolation tube and the soil in front of the bearing plate is grouted, i.e., there is no contact between the rod and the grout, giving it force characteristics similar to those of the P-type anchoring system31.

Consequently, after installation, the P-T type anchor exhibits both T-type and P-type anchor characteristics. However, due to the significant differences in structural form, material properties, and interfacial mechanical behavior between the existing anchors and the P-T type anchor proposed in this study, existing research findings may not be fully applicable. Thus, systematic research on the anchoring performance of P-T type anchors is needed to provide a scientific basis for their application in the anchoring projects of earthen sites.

Methods

To clarify the advantages of the P-T type anchor compared to traditional T-type and P-type anchors, as well as to reveal the influence of the length ratio between the tension and pressure section on anchoring performance, the axial pullout tests were conducted on anchoring system models for T-type, P-type, and P-T type anchors, and Digital Image Correlation (DIC) technology was employed to obtain the strain data.

Materials properties

The structure of the P-T type anchor is illustrated in Fig. 2a. In this study, the P-T type anchor innovatively combines the advantages of both P-type and T-type anchors. Through the expanded body and isolation tubes, it cleverly separates the tension section and pressure section of the anchor. The core innovative mechanism of this two-section design lies in the mechanical decoupling of the tension and pressure sections achieved by the isolation tube. In traditional single-section P-T anchors or P-type anchors, the grout material forms a continuous medium. Under load, the entire grout in front of the bearing plate is pushed forward, generating significant radial expansion pressure (due to the Poisson effect and shear dilation), which may cause cracking in the surrounding soil. To overcome this inherent limitation, this anchor uses a waxwood rod as the main body, with a ring-shaped expanded bearing plate fixed in the middle and an isolation tube installed in front of the bearing plate and sleeved over the rod, thereby forming a two-section structure aimed at mechanically isolating the tension and pressure zones. The core hypothesis is that by blocking the complex stress interactions at the R-G interface in the grout layer ahead of the bearing plate, the distribution of radial stress can be more effectively controlled. This helps suppress undesirable failure modes of the anchorage system and ultimately better ensures the integrity of the site itself during failure.

This anchor primarily consists of a waxwood rod, an expanded bearing plate, and an isolation tube. The waxwood rod was selected as a straight, uniform circular rod with a radius r of approximately 14 mm, free of knots or other defects. Since these rods were not originally intended for experimental applications, their mechanical specifications were independently verified through laboratory testing. According to the test method provided in refs. 32,33, the average tensile strength parallel to the grain of the waxwood rod was measured as 103.94 MPa34, and the average bending strength was 118 MPa34.

The bearing plate is made of brass, with an outer radius R of 30 mm, closely matching the radius of the anchor hole. Its stiffness and strength significantly exceed those of waxwood and rammed earth. To facilitate grouting and DIC measurement, the circular cross-section of the bearing plate was modified into a quasi-elliptical shape using a chord-cutting method.

The isolation tube is made from a 3-mm-thick PVC tube with an inner radius of 16 mm, slightly larger than that of the wooden rod.

During the fabrication process, the bearing plate is initially fixed onto the wooden rod according to the designed pressure and tension section length. Epoxy resin is used for bonding, and several wooden wedges are preset in the gap to prevent axial relative sliding between the bearing plate and the waxwood rod. The pressure section is then fitted with a PVC tube to prevent bonding between the rod and the grout, as depicted in Fig. 2b. It should be noted that, for the convenience of model preparation, the brass bearing plate and PVC isolation tube have relatively poor durability. In actual heritage conservation projects, durable, high-strength materials such as fiber-reinforced plastic (FRP) can be used as substitutes.

To compare the anchoring performance of different anchors, the T-type, P-type, and P-T type anchors had the same total anchoring length of 450 mm. The P-T type anchors were further categorized into three types based on pressure-tension section length ratios of 1:1, 2:1, and 3:1, as shown in Fig. 2c.

To facilitate subsequent comparative analysis, the difference among these anchors can be uniformly represented by the proportion of the pressure section length (PPSL), i.e., the T-type and P-type anchors can be considered as having PPSLs of 0% and 100%, respectively. The P-T type anchors with pressure-tension section length ratios of 1:1, 2:1, and 3:1 correspond to PPSLs of 50%, 66.6%, and 75%, respectively.

To promote compatibility and ensure coordinated deformation of the anchoring system, an eco-friendly grouting slurry suitable for earthen sites was previously developed. This grouting slurry uses calcined ginger nut, sticky rice pulp (6% concentration), and loess as raw materials, with the ratio of 20 wt%, 20 wt%, and 60 wt%, respectively. A water-to-solid ratio of 0.55 was adopted, defined as the weight ratio of water to the total weight of solid materials (calcined ginger nut, sticky rice flour, and loess). Additionally, 0.6 wt% of 6-mm-long coir fibers was added to improve its mechanical strength and ductility while reducing the curing shrinkage rate. The prepared grout exhibits the following physical and mechanical properties: fluidity exceeding 106.3 mm, curing shrinkage rate below 1.66%, unconfined compressive strength around 1.64 MPa, and flexural strength ~0.71 MPa35. Fluidity test was conducted following GB/T 2419-200536; unconfined compressive and three-point flexural strengths were tested per GB/T 17671-202137, while shrinkage was measured according to JC/T 603-200438. Detailed testing procedures and material performance data can be found in ref. 35.

The Loess utilized for model compaction originated from Huyi District, Xi’an, China, at a depth ranging from 2.0 m to 3.5 m. The undisturbed soil was air-dried, crushed, and passed through a 5 mm mesh sieve, and sealed for model ramming. According to refs. 39,40, the properties indices of loess were characterized, with results in Table 1.

Modeling procedure

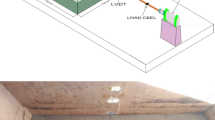

This study employs DIC technology to measure the strain evolution of the anchoring system. Therefore, the anchoring system model was redesigned to meet the specific requirements for DIC measurement. A transparent tempered glass pane of 1.4 cm thickness was utilized to make the geotechnical box. The internal dimensions of the box were 500 mm (length) × 450 mm (width) × 650 mm (height). The anchor was installed tightly against the observation surface to fully expose internal deformation and potential damage within the anchoring system. The modeling procedure is as follows (Fig. 3(a)):

-

(1)

Preparation of the geotechnical box. To prevent soil and grout from adhering to the observation glass during the ramming and grouting processes, a 2 mm thick steel plate (matching the size of the observation surface) was pre-positioned on the observation side before soil ramming. The isolation steel plate was removed before loading.

-

(2)

Pre-reservation of anchor holes using PVC tubes. PVC tubes with a radius of 30 mm were used as pre-reserved anchor holes during modeling, and the cross-section of the PVC tubes was modified into a chord shape. The cut side was fixed tightly against the observation glass to fully expose the anchoring system deformation.

-

(3)

Model ramming. The loess was thoroughly mixed to achieve an optimal moisture content of 14.2%. The model was then prepared using a layered, manually ramming method, with each layer compacted to a thickness of 75 mm ± 2 mm. Upon completion of compaction of each layer, samples were extracted using a cutting ring to determine the compaction coefficient40. The compaction coefficient was no less than 0.941.

-

(4)

Anchor installation and grouting. After soil ramming, the PVC tubes were moved, and the anchor was installed centrally. Low-pressure grouting was then performed and cured for at least 35 days before testing. If shrinkage cracks appeared during this period, secondary grouting should be conducted.

-

(5)

Application of reaction force. The geotechnical box was bolted to the loading device. Two sets of counterweights, each 20 cm in diameter and 15 kg in weight, were placed on the top of the model, with four weights stacked per set, to provide extra reaction force, as shown in Fig. 3b.

It should be noted that, to facilitate optical observation (during DIC measurement), the anchor was positioned close to the glass surface in this experiment. This arrangement may have somewhat weakened the interfacial bond strength between the anchor and the rammed earth, potentially resulting in measured absolute bearing capacity values that are lower than their actual values in earthen structures. However, it is important to emphasize that all comparative tests were conducted under this uniform condition, meaning the influence of this factor on the observed trends is systematic and consistent across all results. The core conclusions of this study focus on the comparative performance evaluation among different anchor types, rather than the precise numerical values of their absolute bearing capacity. Therefore, we maintain that this experimental setup does not affect the key findings of this paper regarding the relative performance of different anchors.

Loading and measurement scheme

This experiment utilized a universal testing machine to apply continuous pullout loads to the anchor, as shown in Fig. 3c. The loading scheme was developed according to refs. 42,43. The displacement-controlled loading process was carried out at a monotonic rate of 2 mm/min. Loading is terminated when the anchor rod fractures, significant slippage occurs, or the recorded load fluctuates continuously within ±2% of the current value for 1 min, indicating that the specimen has reached a stable residual state, the test was stopped. When the specimen exhibited a distinct peak, the peak load was defined as the load value at the peak of the curve (this definition was applied to all PPSL cases except PPSL = 75%). For PPSL = 75%, after reaching the turning point, the load gradually stabilized, and the peak load was taken as the load value at the turning point.

During the loading process, the DIC system was employed to track full-field strain evolution on the observation surface. It was configured to capture images at 500 ms intervals with a resolution of 4090 × 3000 pixels. Before image acquisition, a calibration board was used to calibrate measurement accuracy, ensuring a confidence level of no less than 95%.

Previous studies have revealed that the T-type anchor primarily experiences slip failure at the R-G interface22,26,27. However, this interface is often encased in grout, making it difficult to obtain effective strain data through DIC. Therefore, strain gauges were also attached along the wooden rod in the tension section to measure the strain distribution at the R-G interface.

Results

Load–displacement relationship

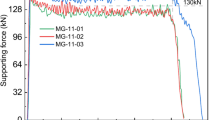

The load-displacement curves of the T-type, P-type, and P-T type anchoring systems are presented in Fig. 4a. It is evident that the curve shapes of the three types of anchors differ significantly. In the case of the T-type anchor, the load increases rapidly before reaching the peak value of 4.47 kN. However, once the peak load is reached, it drops sharply, with the residual load decreasing by more than 80% relative to the peak load. This finding is consistent with those from previous studies9,26,27, where the performance of this type of anchoring system is primarily governed by the bond strength of the R-G interface44.

For the P-T type anchor with a PPSL of 50%, it exhibits a similar trend to that of the T-type anchor, though the peak load is markedly higher. However, when the PPSL increases to 75% and 100%, the post-peak curve does not show a significant decline. Instead, the load maintains a slight increase with displacement and eventually stabilizes, demonstrating a high residual bearing capacity, with decreases of only 6.04% and 8.81% compared to the peak load, respectively.

This behavior is attributed to the compressive force exerted by the bearing plate on the grout, causing a radial expansion tendency. However, the rammed earth surrounding the anchor constrains this expansion, resulting in strong frictional and mechanical interlocking effects among the anchor, grout, and soil, thereby maintaining a higher interfacial bonding stress.

It can also be found from Fig. 4b that, since the anchor with a pressure section must compress and densify the gap between the bearing plate and the grout to form bearing capacity, the curve remains relatively flat during the initial loading phase (displacement within 0–5 mm). In contrast, the T-type anchor can quickly generate bearing capacity due to the bonding effect at the R-G interface, resulting in a steeper curve. This indicates that the initial stiffness of the T-type anchoring system is higher than that of anchors containing a pressure section. Thus, the T-type anchor is more suitable for anchoring projects where strict deformation control is required, while the P-T type and P-type anchoring systems offer better deformation capacity and ductility.

The variation trends of peak load and residual load with PPSL for the three types of anchoring systems are shown in Fig. 5a. It is evident that, as the PPSL increases, the peak load shows an approximately linear growth trend. Therefore, in terms of load-bearing capacity, the P-type anchor demonstrates superior performance. This is mainly because in the later stages of loading, as the anchor rod is gradually pulled out, the tension section enters the friction or debonding stage first, and then the bearing capacity is primarily provided by the pressure section, with its peak load being positively correlated with the pressure section length23. The trend in residual load is similar to that of the peak load. The aforementioned linear relationship can be fitted by the following equation:

For Peak load:

For Residual load:

Where, YP and YR represent the peak load and residual load, respectively; X represents the value of PPSL.

The discovered approximately linear relationship between bearing capacity and PPSL indicates that, although not strictly linear due to interfacial interactions, the contributions of the tension and pressure sections are largely additive. This finding is crucial for engineering, as it validates the effectiveness of the simplified design method—namely, that the P-T anchor achieves decoupling, with its total capacity being the sum of the contributions from each section and a direct function of their respective bond areas and strengths. This linear trend arises because a change in PPSL proportionally alters the bond area of the pressure and tension sections, thereby scaling its contribution linearly.

It should also be mentioned that, as PPSL increases, the pullout displacement corresponding to the peak load also gradually increases. However, when the PPSL exceeds 75%, the rate of increase decreases to a negligible level, indicating a certain marginal effect, as shown in Fig. 5b.

Typical failure mode

The 2D full-field strain contour maps within the observation plane obtained through DIC are presented in Fig. 6, and typical cracking damage and failure modes are shown in Fig. 7. Three characteristic points were selected for each model in the linear growth phase, yielding phase, and strengthening phase of the load–displacement curve to illustrate the strain evolution. These points were labeled as A, B, and C, respectively, as shown in Fig. 4a.

It should be noted that, for the T-type anchor (PPSL = 0%), slip failure mainly occurs at the R-G interface22,26,27, resulting in no significant deformation at the observation surface, thus the strain data cannot be efficiently captured by DIC. Therefore, the strain field of the T-type anchoring system is not shown in Fig. 6.

Regarding the P-T type anchoring system: (ⅰ) When PPSL = 50%, at the early stage of loading (Point A), significant strain growth can be observed in the pressure section along the G-S interface, which also causes some grout deformation in the tension section. As the load increases, the strain evolution in the two sections diverges, with the R-G interface strain in the pressure section continuing to grow while the strain in the tension section gradually decreases (from Point B to Point C). This discrepancy primarily arises from the nature of DIC measurements, where strain is calculated based on the relative displacement of pixel points on the observation plane. In the later stages of loading, debonding occurs at the R-G interface of the anchorage system, and the tension section of the anchor rod is pulled out from the grout while the grout remains in its original place. As a result, the relative displacement between pixel points in this region, as captured by DIC, ceases to change, leading to correspondingly low strain values in this area. Ultimately, the typical failure mode involves slip failure at the R-G and G-S interfaces in the pressure and tension sections, respectively, as shown in Fig. 7a, b. The rammed earth remains relatively intact, and the anchor hole wall is smooth after failure (Fig. 7c), which is beneficial for site conservation.

(ⅱ) When PPSL = 66.6%, the overall strain evolution trend is similar to that of PPSL = 50%. However, when the load reaches 5.73 kN, the strain in the compacted layer near the bearing plate significantly increases, and small horizontal cracks occur and rapidly expand (Point B–C), as shown in Fig. 7a. This crack results in some energy release, after which the strain growth rate slows. This phenomenon corresponds to the notable load drop after the first peak point in Fig. 4a, indicating that the compacted layer may become a weakness of the anchoring system.

(ⅲ) When PPSL = 75%, the anchoring system primarily fails due to slip failure at the G-S interface, with partial compression bulging of the grout in front of the bearing plate, as shown in Fig. 7b. However, during this process, the grout behind the bearing plate is also partially pulled out along with the anchor rod, while only a small portion at the bottom experiences R-G interface slip failure. This may be caused by significant shrinkage deformation of the grout at the tension section during solidification, weakening the bond strength at the G-S interface.

In contrast to the P-T type anchor, the P-type anchor (PPSL = 100%) not only experiences slip failure at the G-S interface, but also causes significant cracking damage to the surrounding rammed earth. Specifically, a high-strain “V”-shaped area forms, with an angle of about 35–40° relative to the axial direction of the anchor (Point C), which is consistent with the findings by Tóth45.

Therefore, despite the P-type anchor having the highest load-bearing capacity, it is prone to causing cracking damage to earthen sites itself. Thus, it is unsuitable for the anchoring projects where high load-bearing capacity is required.

With an increase in the PPSL value, the evolution of the failure mode exhibits an overall trend rather than a completely linear transition. At PPSL = 50%, the dominant behavior is interfacial slip. For specimens with PPSL = 66.6%, localized horizontal cracks appear near the bearing plate (Figs. 6b and 7a). These specific cracks are attributed to the shear dilation effect, which is exacerbated by the parallel and adjacent interfaces between the bearing plate and the rammed earth layer. At PPSL = 66.6%, the angle between the rammed layers and the anchor rod in the test was 90°, which facilitated the development of horizontal cracks near the bearing plate due to shear dilation. However, in actual engineering applications, this angle typically ranges from 5° to 30°, significantly reducing the likelihood of such crack propagation along horizontal interfaces; In contrast, at PPSL = 75% (Fig. 6c), the deeper embedment of the bearing plate, possibly located within the soil layer, leads to enhanced confinement. No extensive surface cracks are observed, although internal damage is present (Fig. 7a). The strain field contour maps (Fig. 6) do not capture distinct crack damage, primarily because deformation at the G-S interface dominates the internal soil deformation. However, post-failure observations (Fig. 7a) clearly reveal the formation of a V-shaped crack pattern in the surrounding soil, confirming the presence of internal damage. Therefore, although the risk of soil cracking increases with higher PPSL values, the specific manifestation (such as horizontal layered cracking versus V-shaped cracking) can be influenced by local heterogeneities, such as the interfaces of rammed earth layers. The overall trend remains consistent: lower PPSL values promote interfacial slip, while higher PPSL values exacerbate soil cracking.

Strain distribution and evolution

As demonstrated by Section “Loading and measurement scheme”, the R-G interface in the pressure section and the G-S interface in the tension section are the primary control surfaces for the slip failure of the anchoring system. Therefore, considering the convenience of strain data acquisition, strain gauges and DIC strain point extraction methods were used to obtain the strain distribution of the R-G and G-S interfaces, respectively. The strain gauges (dimensions: 6.9 mm × 3.9 mm, sensitivity: 2.0% ± 1%) were attached to the mid-section of the anchor rod (see Fig. 8) to measure the axial strain distribution. Although strain gauges may locally affect interfacial adhesion, their small size and axial alignment of wiring minimized this impact. The results are shown in Fig. 8.

In Fig. 8, it can be observed that for P-T type anchors, most of the interface strain values are positive, which may differ from those typically reported in conventional P-type anchorage systems. Previous studies have shown that in fully bonded T-type systems, the interface strain is generally positive due to axial tensile strain in the anchor rod under pull-out loading46. However, for P-type anchors or novel anchors featuring a local expansion body (e.g., bearing plates, air bags, or helical blades), the expansion body compresses the grout during loading. Under the combined action of axial compressive forces, confining pressure from surrounding soil, dilation, and Poisson’s effect, the grout may undergo complex deformation. This can result in compressive strain (i.e., negative strain) at the G-S interface near the expansion body47.

In this study, although compressive strain was indeed observed near the G-S interface around the bearing plate in the P-type anchorage system, such strain was not observed in the P-T type anchorage system. This phenomenon primarily stems from the unique load-transfer mechanism of the P-T anchor and the observational design of this test:

(a) The dominant mechanism is interface slip rather than local compression: Unlike traditional P-type anchors that are deeply embedded and strongly constrained, the bearing plate of the P-T anchor in this study is shallowly embedded with weak top constraint. Under pull-out load, the overall slip along the loading direction between the grout and the surrounding soil constitutes the dominant deformation. The tensile strain generated by this slip far exceeds in magnitude the minor local compressive strain that the bearing plate might induce in the grout.

(b) As mentioned in the original text, the asymmetric layout of the specimen (with the anchor close to the glass surface), adopted to facilitate DIC measurement, weakened the interface bond. This systematically promoted the slip-dominated deformation mode, making the tensile strain more pronounced. Furthermore, although efforts were made to minimize eccentric loading through base fixation and alignment of the anchor with the loading device, the inherent asymmetry of the specimen inevitably introduced eccentricity during loading. This led to further concentration of tensile strain near the bearing plate, while the compressive strain zone was reduced or completely overshadowed by the tensile strain.

Similar to the results disclosed in refs. 26,27,48, the strain distribution at the R-G interface is highly uneven. At lower loads, the strain distribution follows an exponential pattern, with the higher strain region concentrated at the front end of the anchor. As load increases to 4 kN, a strain inflection point appears at an anchoring depth of approximately 10–15 cm, and the strain change decreases in this region. According to the interface bonding stress calculation method provided by Biscaia Hugo49, the interfacial bonding stress near the front end significantly decreased, gradually entering a softening or friction state.

The critical anchorage length refers to the ultimate anchorage length, that is, beyond this length, the load-bearing capacity of the anchor will no longer increase significantly. For the P-T type anchor, since the tensile load is transmitted from the bearing plate to both the front end and the back end, the critical anchorage length is significantly increased. However, the mechanical behavior of the R-G and G-S interfaces differs significantly, with a notable strain discontinuity occurring on both sides of the bearing plate. Specifically, the strain distribution and evolution patterns at the R-G interface in the tensile section are similar to those of the T-type anchor, with the maximum strain concentrated at 400–600 με. In contrast, the strain values at the G-S interface in the pressure section are generally higher than those at the R-G interface, and the strain decays exponentially from the bearing plate to the front end. However, at higher loads, the strain across the entire pressure section maintains a relatively high value, indicating that the interface has entered the strengthening or friction state23.

These strain distribution characteristics provide crucial evidence for understanding the effective anchorage length of the P-T anchor. As shown in Fig. 8, the high-strain zone of the T-type anchor is concentrated near the loaded end, and the strain decays rapidly with distance, indicating a limited effective anchorage zone. In contrast, the strain distribution of the P-T anchor exhibits a notable “dual-zone synergy” characteristic: the load is transferred from the bearing plate towards both the starting end and the far end. High-strain zones not only appear in the pressure section near the bearing plate but also maintain considerable strain levels at the R-G interface within the tension section (see Fig. 8b-d). The advantage of the P-T anchor lies in the decoupling of the tension and pressure sections. This dual-zone synergistic effect indicates that the cumulative effective anchorage length, composed of both the tension and pressure sections of the P-T anchor, is significantly greater than that of T-type anchors. Consequently, the P-T anchor can mobilize interfacial bond strength over a longer distance to resist pull-out loads.

The strain distribution trend at the G-S interface of the P-type anchor is generally similar to that of the pressure section of the P-T type anchor. However, it is noteworthy that a negative strain appears in a smaller area in front of the bearing plate, which may be due to the combined compression effects from the bearing plate and the surrounding rammed earth, leading to a complex deformation of the grout. The strain evolution pattern at an anchoring depth of 25 cm deviates from expectations, possibly due to the internal force redistribution induced by the “V”-shaped cracking and rammed layer cracking. As also observed in Fig. 6d, the interface strain in front of the bearing plate is notably lower than that near the front end.

Overall, the high-strain area of the T-type anchor is concentrated at the front end, whereas for the P-T type anchor, it is localized near the bearing plate. Thus, the P-T type anchor has a longer critical anchorage length, allowing it to better mobilize the interface bonding strength at different depths to resist the load. Therefore, from a design perspective, the P-T type anchor can meet a specific anchoring force requirement with a shallower drilling depth compared to the T-type anchor, better aligning with the “minimal intervention” principle for earthen sites conservation.

Load-bearing efficiency of P-T type anchors

In the P-T type anchor, the applied pull-out load is typically transmitted directly through the anchor rod to the bearing plate, which subsequently distributes the force toward both the free end and the anchoring end. This bidirectional load transfer mechanism endows the system with superior load transmission efficiency compared to conventional T-type or P-type anchorage systems.

To assess the anchorage efficiency of the proposed P-T type anchor, the assumption of average shear stress distribution was utilized to compute both the average bond stress (defined as the ratio of ultimate load to the interface area) and the unit-length anchorage capacity (defined as the ratio of ultimate load to anchorage length).

As illustrated in Fig. 9, the average bond stress—calculated under the assumption of a uniform shear stress distribution—exhibits minor fluctuations across different PPSL values, consistently falling within 103–113 kPa. This indicates that the average bond stress is effectively independent of variations in PPSL. In contrast, the load-bearing capacity per unit length, also derived under the uniform shear stress assumption, increases with rising PPSL. When the PPSL increases from 0% to 100%, the unit load-bearing capacity increases from 9.93 to 19.93 kN/m, representing an increase of ~100.7%, indicating that an increase in the bonding area of the pressure section is beneficial for improving the unit load-bearing capacity.

Given that the total anchorage length of the P-T type anchors remains constant across all PPSL configurations, the trend of unit load-bearing capacity is consistent with that of the ultimate load-bearing capacity. Both exhibit a clear linear positive correlation with PPSL, as shown in section “Load–displacement relationship”.

Since existing studies on anchorage systems for earthen sites have primarily focused on T-type or single-section P-T type anchors, we mainly compared our results with those reported in refs. 26,27. to clarify the load-bearing characteristics and anchorage efficiency of the proposed system, as shown in Table 2. The anchorage efficiency calculated based on the assumption of average shear stress distribution shows a significant deviation from the results reported in refs. 26,27. Specifically, the average bond stress is lower by more than 55%, while the anchorage capacity per unit length is lower by more than 29%.

Compared to the single-section P-T composite anchor (denoted as WTCB in Table 2) reported by Wang et al.26,27, significant differences in calculated bearing efficiency are observed. The WTCB anchor demonstrates higher load-bearing capacity per unit length and higher average bond stress. This is primarily attributed to its full-length bonding technique, which maximizes the utilization of bond strength at both the R-G and G-S interfaces along the entire anchor length. In contrast, the proposed two-section design in this study intentionally disconnects the bond between the rod and the grout layer through an isolation tube. Although this results in a reduced total bond area and a lower calculated “efficiency” under the uniform stress assumption, it fundamentally alters the failure mode. The WTCB anchor typically fails through the formation of a conical grout wedge, generating significant radial stresses. By decoupling the zones, our design is engineered to induce a more progressive interface slip failure. Thus, the advantage of the proposed anchor lies not in maximizing nominal bond efficiency, but in sacrificing partial efficiency to achieve a less destructive and more controllable failure mechanism—while maintaining sufficient load-bearing capacity for most practical anchorage needs—which holds higher priority for the conservation of vulnerable earthen heritage sites.

Ideal failure mode by PPSL control

As detailed in Section “Loading and measurement scheme”, an increase in PPSL will lead to a typical failure mode transition among different anchoring systems, as shown in Fig. 10a. Specifically, the T-type anchor primarily exhibits slip failure at the R-G interface22,26,27. As PPSL increases, the P-T type anchor with low PPSL mainly experiences slippage failure at the G-S and R-G interfaces in the pressure and tension sections50, respectively. This is mainly attributed to the limited constraint on the grout at the front end of the anchoring system. When the PPSL is high, although the P-T type and P-type anchors’ bearing capacity are substantially increased, they will cause the region near the bearing plate to be subjected to significant multi-directional compressive forces, leading not only to anchoring interface damage but also to grout crushing and soil cracking (including “V”-shaped cracking and ramming layer cracking).

It is evident that, although the load-bearing capacity of the anchoring system increases approximately linearly with PPSL, the potential damage to the rammed earth structure is also more severe. For heritage sites conservation, the anchorage design must align with the principle of “maximizing safety” and “minimizing intervention”. Therefore, there is a conflict between the two optimal objectives, necessitating a balance based on specific engineering requirements.

Accordingly, this study underscores the importance of identifying an optimal PPSL that achieves a desirable balance between enhancing the load-bearing capacity and minimizing the risk of site cracking. For instance, when PPSL = 50%, the system exhibits a 43.4% improvement in load capacity relative to the T-type anchor, while its failure mode remains confined to interface slip at the R-G and G-S interfaces, without observable soil body cracking. This configuration, therefore, presents a more favorable trade-off for site preservation compared to the P-T type (with large PPSL) and P-type anchors, despite their higher load-bearing capacities.

Taking advantage of the flexibility in adjusting PPSL in the two-section P-T type anchor, the core of the P-T type anchor design should focus on determining the optimal PPSL to maximize anchoring force while confining the failure mode to G-S and R-G interface slip.

Simplified calculation methods for load-bearing capacity

To clarify the load-bearing efficiency of the tension and pressure sections of the P-T type anchor, we propose a simplified method for calculating the load-bearing capacity based on the average bond stress.

The method is based on the average bond stress at the R-G interface of the T-type anchor (PPSL = 0%) and the average bond stress at the G-S interface of the P-type anchor (PPSL = 100%). These values are multiplied by the corresponding bond areas of the tension section and the compression section of the P-T anchor, respectively, and then summed to obtain the total bearing capacity (i.e., bearing capacity = average bond stress × bond area).

The simplified calculation steps are as follows:

-

(a)

Obtain the average bond stress \({\tau }_{Av}^{t}\) at the R-G interface from the T-type anchor system (PPSL = 0%), as shown in Eq. (3), where \({P}_{\max }^{t}\) represents the ultimate bearing capacity of the T-type anchor system, measured experimentally, and \({A}_{bond}^{t}\) denotes the G-S interface bond area of the T-type anchor;

-

(b)

Obtain the average bond stress \({\tau }_{Av}^{p}\) at the G-S interface from the P-type anchor system (PPSL = 100%), as shown in Eq. (4), where \({P}_{\max }^{p}\) represents the ultimate bearing capacity of the P-type anchor system, and \({A}_{bond}^{p}\) denotes the R-G interface bond area of the P-type anchor;

-

(c)

Calculate the R-G interface bond area \({A}_{bond}^{R-G}\) and the G-S interface bond area \({A}_{bond}^{G-S}\) of the P-T anchor;

-

(d)

Calculate the total bearing capacity \({P}_{P-T}\) of the P-T anchor using \({\tau }_{Av}^{t}\) and \({\tau }_{Av}^{p}\), as shown in Eqs. (5)–(7).

The calculation results are shown in Table 3, and a comparison between the calculated bearing capacity and the actual anchorage capacity is presented in Table 4.

Table 4 presents a comparison between the calculated bearing capacity and the actual anchorage capacity. It can be observed that although the calculation process only considers the influence of the interfacial bond effect (while ignoring soil cracking under high PPSL conditions), the maximum error between the calculated and measured values remains below 5%. Therefore, this simplified calculation method can be used to evaluate the load-bearing capacity of P-T type anchors.

However, special attention should be paid to the applicable conditions and limitations of this simplified method. The calculations are based on the assumptions of uniformly distributed bond stress and pure interface slip failure. Under high PPSL conditions (e.g., ≥66.6%), when significant soil cracking occurs (as shown in Figs. 6 and 7), the actual bearing capacity may be slightly higher than the calculated value (for example, in Table 4, at PPSL = 66.6% and 75%, the actual bearing capacities are both higher than the calculated values; moreover, at PPSL = 66.6%, since the bearing plate is closer to the rammed layer, soil layer cracking is more pronounced, resulting in a relatively larger discrepancy between the actual and calculated bearing capacities). This is because soil cracking introduces an additional energy dissipation mechanism not considered in the model.

Thus, although this method can provide effective evaluation with errors controlled within 5% across various PPSL levels and is suitable for straightforward and conservative preliminary design estimates, its predictions for high-PPSL anchors in critical applications must still be validated through field tests or numerical simulations.

Discussion

The P-T type anchor combines the characteristics of both the T-type and the P-type anchors51. The pullout load will be directly transferred to the bearing plate via the wooden rod, which compresses and pushes the grout outward at the pressure section, while simultaneously pulling out the rod in the tension section. Consequently, the bond stress at the G-S interface in the pressure section is transmitted from the bearing plate towards the front end, while the shear stress at the R-G interface in the tension section is transmitted in the opposite direction.

Benefiting from this special force transmission mode, the deep interface bonding strength of the P-T type anchor is more effectively mobilized, and the effective anchoring length is significantly increased. Therefore, the peak load and residual load of the P-T type anchor are significantly superior to those of the T type anchor. The peak load shows an approximately linear relationship with the PPSL. This means that under the premise of providing the same load-bearing capacity, the required drilling depth for P-T type anchor is significantly less than T-type anchor, aligning with the “minimal intervention” principle. The core of this study lies in optimizing the PPSL system to achieve a balance between two conflicting objectives in earthen site conservation: maximizing anchorage capacity and minimizing the degree of intervention. The “minimal intervention” principle is realized through a dual approach: (1) Reducing construction damage: By significantly enhancing the load-bearing capacity per unit length (as shown in Fig. 9), the proposed P-T anchor, compared to T-type anchors, allows for shallower borehole depths under equivalent design loads, thereby reducing physical impact during installation. (2) Mitigating long-term service risks: More importantly, by controlling the PPSL (e.g., maintaining it at around 50%), the failure mode can be shifted from destructive soil cracking (as observed in P-type anchors) to the less damaging interface slip. This ensures that the anchor itself does not become a new source of cracks threatening the long-term stability of heritage structures. Thus, the PPSL optimization strategy faithfully implements the “minimal intervention” principle across both the construction phase and long-term maintenance. For instance, when PPSL = 50%, the load-bearing capacity increases by 43.40%, meaning that the drilling hole depth under the same load-bearing capacity requirement can be reduced by approximately 30%. This will significantly reduce the damage to the site caused by the installation of the anchor.

However, when PPSL exceeds 75%, the increase in load-bearing capacity is very limited, indicating a marginal effect. In contrast, the corresponding peak displacement is significantly increased, and the residual load remains high, demonstrating excellent ductility and post-peak performance.

It is also worth noting that while increasing PPSL enhances load-bearing capacity, it also leads to a shift in failure mode. At low PPSL, e.g., 50%, failure is dominated by interfacial slippage (R-G and G-S interfaces) without significant soil cracking. However, high PPSL (≥75%) triggers compressive stress accumulation near the bearing plate, leading to “V”-shaped cracking in rammed earth. To avoid cracking damage to the site body during the pull-out process of the P-T type anchor rods, the ideal failure mode of this anchor is considered to be the slip failure at the G-S interface and R-G interface in the pressure section and tension section, respectively. This highlights the necessity for balancing anchoring force and structural safety by optimizing PPSL.

Experimental results indicate that when PPSL is set at 50%, the P-T anchor system achieves an optimal balance between significantly enhanced bearing capacity (43.4% improvement compared to the T-type anchor) and avoidance of severe soil cracking. Therefore, a PPSL value of 50% is recommended as a practical starting point for design in earthen sites conservation projects where structural damage control is prioritized. It should be noted that this recommended value is primarily based on a comprehensive performance evaluation under the conditions of this study; in practical applications, further verification and comprehensive judgment considering specific soil properties, anchorage depth, environmental loads, and other site-specific conditions are necessary.

It should be noted that this study is a laboratory-scale model test. Nevertheless, key dimensions within the model—such as anchor rod diameter (2–5 cm) and grout thickness (5–12 cm)—are largely consistent with commonly employed field dimensions. Moreover, the measured bearing capacity already satisfies the required magnitude for anchoring most earthen sites, indicating that the model possesses sound field representativeness in terms of core stress mechanisms. Although differences in anchor length and soil conditions compared to in-situ conditions may influence displacement control and post-peak softening behavior, these factors do not significantly alter core patterns such as the performance trends across anchor types, the fundamental shape of load-displacement curves, or the dominant failure mode governed by PPSL. Consequently, the primary trends and failure modes revealed in this study are anticipated to provide valuable reference for in-situ applications and subsequent prototype development.

The P-T anchor involved in this study still has certain limitations, such as the relatively low strength of the rod material (waxwood rod) and the tendency for stress concentration to occur under high PPSL conditions. Therefore, to address these limitations and meet the anchoring requirements of large-scale site structures, we propose two structural improvement strategies: the Multiple pressure-tension type (MP-T type) anchor and the Extension-type bamboo/FRP tension-pressure composite anchor (EBTP type). The MP-T anchor aims to mitigate stress concentration by distributing the compressive load across multiple pressure sections, while the EBTP anchor significantly enhances the rod strength based on the existing P-T anchor design by embedding a high-strength FRP anchor rod inside and sleeving it with hollow bamboo. This multi-layered configuration is purposefully engineered to extend the service life of the anchor rod and resolve the deformation compatibility issue between the high-strength rod and the low-strength rammed earth.

-

(1)

Multiple pressure-tension type composite anchor (MP-T type). Section “Load–displacement relationship” revealed that when the PPSL is large, the compressive stress on the grout in front of the bearing plate cannot be adequately released via grout displacement, potentially causing severe cracking damage in the rammed earth. To address this issue, a Multiple pressure-tension type (MP-T type) composite anchor was proposed. This structure divides the pressure section of P-T type anchor into multiple shorter pressure sections, then the force transfer characteristics are similar to those of pressure-dispersing anchors31,52, as shown in Fig. 11a.

When the anchor is pulled out, each bearing plate simultaneously generates axial displacement, and the stress in each pressure section is transmitted from the bearing plate towards the front end 53. Once the bearing plate moves, it provides space for sliding or deformation of the grout in the adjacent pressure section, thereby effectively releasing the compressive stress on the grout, and limiting the failure mode to G-S interface slip. In this mode, the tension section is no longer essential. However, if strict deformation control of the sites structure is required, a tension section with an appropriate length can also be added to provide higher initial stiffness.

-

(2)

Extension-type bamboo/FRP tension-pressure composite anchor (EBTP type). For large-scale anchoring projects with high anchoring force requirements, the mechanical strength of the wooden rod itself becomes the primary limiting factor in anchoring performance26,27. Replacing the wooden rods with high-strength metal rods, such as rebar or steel strand, could effectively address the issue of anchor fracture under high pullout loads. However, the significant disparity in stiffness between these metal rods and other earthen-based materials makes achieving deformation coordination challenging. Moreover, the poor durability also restricts their application in earthen sites conservation.

Drawing on the hollow structure of bamboo, researchers have proposed a new bamboo-steel composite anchor that insert steel bar into the hollow cavity of the bamboo, and fill and seal the gap with epoxy resin17,54. This structure not only solves the corrosion problem of metal materials, but also creates a multi-layer structure with mechanical strength and stiffness radial gradient variation in anchoring system, effectively improves deformation coordination between the different components of the anchoring system55,56.

Inspired by those studies, an extension-type bamboo/FRP pressure-tension (EBPT) composite anchor was developed, as shown in Fig. 11b. This anchor replaces wooden rods with FRP or other high-strength, durable materials. The FRP rod is encased within a bamboo tube. In the tension section, the rod is firmly bonded to the bamboo using epoxy resin, whereas in the pressure section, a gap is reserved between the rod and bamboo. During installation, only the gaps between bamboo and soil need to be filled by grouting. The EBPT type anchor structure still maintains the main mechanical characteristics of the P-T type anchor, i.e., involving both pressure and tension sections, offering greater potential for enhancing the anchoring performance, while effectively reducing damage to the sites body. However, these anchors are still in the conceptual design stage, and their manufacturing techniques, anchoring mechanisms, and analytical methods, etc. still need to be further investigated.

Although this study preliminarily clarifies the variation patterns of bearing performance and failure modes of the two-section P-T type anchorage system with increasing PPSL, limitations due to indoor model simplification and insufficient parallel specimens necessitate more extensive parallel tests and on-site pull-out experiments in the future to provide adequate data support for engineering applications.

Data availability

The data are included in this article.

References

Sun, M., Wang, X. & Li, Z. A Preliminary Discussion on the Conservation of Earthen Sites (In Chinese) (Beijing, 2010).

Richards, J., Zhao, G., Zhang, H. & Viles, H. A controlled field experiment to investigate the deterioration of earthen heritage by wind and rain. NPJ Herit. Sci. 7, 51 (2019).

Jaquin, P. & Augarde, C. E. Earth Building: History, Science and Conservation (UK, 2012).

Li, W. et al. Experimental study on morphological characteristics of vertical fissure grouting in earthen sites. Measurement 239, 115537 (2025).

Peng, N. et al. A vulnerability evaluation method of earthen sites based on entropy weight-TOPSIS and K-means clustering. NPJ Herit. Sci. 12, 161 (2024).

Chang, B., Shen, C., Luo, X., Hu, T. & Gu, Z. Moisturizing an analogous earthen site by ultrasonic water atomization within Han Yangling Museum, China. J. Cult. Herit. 66, 294–303 (2024).

Guo, Q. et al. Key issues and research progress on the deterioration processes and protection technology of earthen sites under multi-field coupling. Coatings 12, 1677 (2022).

National Cultural Heritage Administration. Principles for the Conservation of Heritage Sites in China (Revised 2015),(Cultural Relics Press, 2015) (In Chinese).

Chen, J. et al. Anchorage performance of a modified cable anchor subjected to different joint opening conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 336, 127558 (2022).

Blanco Martín, L., Tijani, M., Hadj-Hassen, F. & Noiret, A. Assessment of the bolt-grout interface behaviour of fully grouted rockbolts from laboratory experiments under axial loads. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 63, 50–61 (2013).

Grindheim, B., Li, C. C. & Høien, A. H. Full-scale pullout tests of rock anchors in a limestone quarry focusing on bond failure at the anchor-grout and grout-rock interfaces. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 15(9), 2264–2279 (2023).

Salcher, M. & Bertuzzi, R. Results of pull tests of rock bolts and cable bolts in Sydney sandstone and shale. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Tech. 74, 60–70 (2018).

Cao, C., Ren, T. & Cook, C. Calculation of the effect of Poisson’s ratio in laboratory push and pull testing of resin-encapsulated bolts. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 64, 175–180 (2013).

Chen, W., Du, Y., Cui, K., Fu, X. & Gong, S. Architectural forms and distribution characteristics of beacon towers of the Ming Great Wall in Qinghai province. J. Asian Archit. Build. 16, 503–510 (2017).

Lu, W., Zhao, D., Mao, X. & Ai, Y. Experimental study on bond-slip behavior of bamboo bolt-modified slurry interface under pull-out load. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 6960285 (2018).

Wang, N., Zhang, J., Chen, W., Liao, R. & Li, W. Pulling resistance of two wooden bolts subjected to continuous loading in anchoring conservation of earthen sites. Int. J. Geomech. 23, 04023007 (2023).

Wang, X., Zhang, H. & Lü, Q. Laboratory study of the static properties of bamboo-steel cable composite anchor (In Chinese). China Civ. Eng. J. 44, 108–115 (2011).

Lu, W., Luo, K., Liu, C., Sun, H. & Li, D. Revamp of the eco-friendly grouting materials by mixing basalt fiber for earthen sites conservation: Compressive performance and constitutive models. Constr. Build. Mater. 448, 138234 (2024).

Jiang, H., Lu, W., Luo, W. & He, M. Basalt fiber as natural reinforcement to improve the performance of ecological grouting slurry for the conservation of earthen sites. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 62, 20230139 (2023).

Wang, N. et al. Evolution of properties under realistic curing conditions of calcined ginger nut grouting mortars used in anchoring conservation of earthen sites. J. Cult. Herit. 40, 69–79 (2019).

Wang, S. et al. Revamp of the sticky rice-lime binder with metakaolin and natural fiber for restoration: Properties and characteristics. J. Cult. Herit. 57, 1–15 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Pull-out behaviour of wood bolt fully grouted by PS-F slurry in rammed earth heritages. Geomech. Geoeng. 12, 1–12 (2016).

Sun, H., Lu, W., Zhao, D. & Li, D. Analytical method for interfacial slip failure processes based on UFL bond-slip Model: Study of grout/soil anchorage interfaces in earthen sites. Comput. Geotech. 176, 106778 (2024).

Nilforoush, R., Nilsson, M. & Elfgren, L. Experimental evaluation of influence of member thickness, anchor-head size, and orthogonal surface reinforcement on the tensile capacity of headed anchors in uncracked concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 144, 04018012 (2018).

Bokor, B., Sharma, A. & Hofmann, J. Experimental investigations on concrete cone failure of rectangular and non-rectangular anchor groups. Eng. Struct. 188, 202–217 (2019).

Wang, D., Cui, K., Wu, G., Feng, F. & Yu, X. Performance and working mechanism of tension-compression composite anchorage system for earthen heritage sites. NPJ Herit. Sci. 7, 52 (2019).

Wang, D., Cui, K., Wu, G. & Yu, L. Comparative study on the anchor performance of wooden tension anchor bolts and tension-compression composite anchor bolts in earthen sites. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 17, 1221–1239 (2022).

Tu, B. et al. Analysis of anchorage performance on new tension-compression anchor Ⅲ: field test (In Chinese). Chin. J. Geotech. 41, 846–854 (2019).

Yang, L., Zhu, X., Xia, H. & Yang, S. Numerical and model experimental application study on the anchoring mechanism of tensile and compression composite anchor rods (In Chinese). J. Xi’an Technol. Univ. 40, 132–142 (2024).

Xia, K., Zhang, M., Zhang, X., Liang, E. & Lei, B. Study on the influence of length variation of tension-compression section on anchorage performance of composite anchor (In Chinese). Chin. J. Undergr. Sp. Eng. 20, 152–161+180 (2024).

Hsu, S. & Chang, C. Pullout performance of vertical anchors in gravel formation. Eng. Geol. 90, 17–29 (2007).

GB/T 1927.2-2022, Test methods for physical and mechanical properties of small clear wood specimens—Part 2: Sampling Methods and General Requirements [S](In Chinese). (China Standard Press, 2022).

GB/T 1927.14-2022, Test methods for physical and mechanical properties of small clear wood specimens—Part 14: Determination of Tensile Strength Parallel to Grain [S](In Chinese). (China Standard Press, 2022).

Mao X. The Protection of Gaochang Site and Research on Consolidated Technology of Bolt (In Chinese). Ph.D thesis. (Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, 2009).

Lu, W., Luo, W., Li, D., Liu, Q. & Liu, J. Performance of coir fiber reinforced eco-grouting material used in earthen sites (In Chinese). J. Build. Mater. 27, 90–98 (2023).

GB/T 2419-2005, Test Method for Fluidity of Cement Mortar [S](In Chinese) (China Standard Press, 2005).

GB/T 17671-2021, Test Method of Cement Mortar Strength (ISO method) [S](In Chinese) (China Standard Press, 2021).

JC/T 603-2004, Standard Test Method for Drying Shrinkage of Mortar [S](In Chinese) (China Architecture & Building Press, 2004).

WW/T 0039-2012, Testing Techniques Specifications for Preservation of Earthen Sites [S] (In Chinese) (Cultural Relics Press, 2012).

GB/T 50123-2019, Standard for Geotechnical Testing Method [S](In Chinese) (China Planning Press, 2019).

GB 50209-2010, Code for Acceptance of Construction Quality of Building Ground [S](In Chinese). (China Planning Press, 2010).

WW/T 0038-2012, Design Specification for Preservation and Reinforcement Engineering of Arid Earthen Sites [S](In Chinese) (Cultural Relics Press, 2012).

CECS 22:200, Technical Specification for Ground Anchors [S] (In Chinese). (China Planning Press, 2005).

Teymen, A. & Kılıç, A. Effect of grout strength on the stress distribution (tensile) of fully-grouted rockbolts. Tunn.Undergr. Sp. Tech. 77, 280–287 (2018).

Tóth, M., Bokor, B. & Sharma, A. Numerical study on closely spaced anchor groups of identical configurations under centric tension loading. Eng. Struct. 224, 111245 (2020).

Lu, W., Zhao, D., Li, D. & Mao, X. Study on the force transfer process of the anchorage interface of bamboo bolt in the rammed earth sites (In Chinese). Lixue Xuebao 51, 524–539 (2019).

Lu, W., Sun, H., Li, D., Yan, X. & Wang, Y. Analytical method of interfacial stress transfer and bearing capacity of pressure-type anchorage system at earthen site with crack sealed by grouting (In Chinese). Lixue Xuebao 56, 198–211 (2024).

Zhang, W., Huang, L. & Juang, C. H. An analytical model for estimating the force and displacement of fully grouted rock bolts. Comput. Geotech. 117, 103222 (2020).

Biscaia Hugo, C., Chastre, C., Borba Isabel, S., Silva, C. & Cruz, D. Experimental evaluation of bonding between CFRP laminates and different structural materials. J. Compos. Constr. 20, 04015070 (2016).

Lu, W., Xue, K., Yan, X., Liu, J. & Li, D. Analysis of pullout failure mode and group anchor effect of the two-anchor system of EBTP anchorage in earthen sites (In Chinese). Chin. J. Solid Mech. 45, 547–564 (2024).

Kim, N. Performance of tension and compression anchors in weathered soil. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 129, 1138–1150 (2003).

Barley, A. D. & Windsor, C. R. Recent advances in ground anchor and ground reinforcement technology with reference to the development of the art. In Proc. ISRM International Symposium 2000.

Zhang, Z., Liu, J., Ye, G., Liang, Z. & He, Z. Performance tests on pressure-dispersed compression anchors in cohesive soils. Int. J. Geomech. 21, 04021012 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Research and prospects of bamboo bolts in China: state of the art. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 80, 1015–1038 (2022).

Zhang, J., Chen, W., Li, Z., Guo, Z. & Wang, N. Analysis of in-situ anchoring characteristics of composite anchor containing steel bar (Ф 22 mm) (In Chinese). Rock Soil Mech 35, 3139–3147 (2014).

Li, Z. et al. Conservation of Jiaohe ancient earthen site in China. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 3, 270–281 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52378195 and 52008332); General Program of Shaanxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No.2025JC-YBMS-506). In addition, the authors would like to express their gratitude to Qinlong Liu for his help during the experimental process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L.: (1) Conceptualization; (2) Methodology; (3) Writing—Review & Editing; (4) Funding acquisition. K.L. and X.Y.: (1) Methodology; (2) Writing—Original Draft; (3) Investigation. D.L.: (1) Investigation; (2) Funding acquisition; (3) Project administration. R.R.: (1) Methodology; (2) Investigation. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, W., Luo, K., Yan, X. et al. Anchoring performance of a novel two-section pressure-tension composite anchor for earthen sites conservation. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 627 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02209-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02209-5