Abstract

Archive storage boxes are preventive tools used by museums and archives to mitigate the impact of adverse external factors. In this study, quaternized chitosan and polyacrylamide double-network gel were used to load sodium octaborate tetrahydrate, which was then combined with paper fibers to produce storage boxes. By analyzing the physiological and biochemical changes of microbial cells and the microenvironment around the boxes, the antifungal effect of these storage boxes was explored. In addition to physical barrier function, the storage boxes can damage the permeability and morphological structure of mold spore membranes. They inhibit mold reproduction by affecting metabolic pathways such as protein synthesis, which can significantly reduce the number of microorganisms and the proportion of dominant bacterial species in library environments. This enhances the ability of the collection environment to resist harmful organisms and reduces the incidence of microbial diseases in cultural relic collections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Culture relics are a precious historical and cultural heritage, holding the surviving traces of human activities with historical, artistic, and scientific value1. As one of the main carriers for traditional culture and art, paper-based relics have a pivotal role in the inheritance of invaluable cultural information. The enduring threat of microbial contamination to historical and contemporary objects of art in archives and in museums remains one of the principal problems of cultural heritage conservation2,3. Microbes can penetrate deep within the microstructures of materials, causing material loss from acid corrosion, enzymatic degradation, and mechanical attack, all of which induce esthetical spoiling of paintings, sculptures, textiles, ceramics, metals, books, and manuscripts alike. Regular decontamination of infected artefacts, exhibition areas, and storage rooms/depots results in significant expenditures for museums, local authorities, and private collectors4,5,6. Ultimately, material loss brought about by prolonged microbial attack can result in loss of the cultural and historical value of paintings, books, and manuscripts, the socioeconomic cost of which is inestimable. Furthermore, microbial contamination in libraries, museums, and their storage rooms/depots can also represent a serious threat to the health and occupational safety of restorers, museum personnel, and the general public7,8.

The degradation rate of movable tangible cultural heritage objects and artifacts can considerably increase due to exposure to unstable climatic conditions, light, and environmental pollutants9. As a well-known example, acidic historic papers and documents containing iron gall ink are prone to deterioration when exposed to temperature and humidity fluctuations10,11,12. However, the majority of precious documents and artifacts owned by museums and archives are often stored in climatically uncontrolled storage areas and in museum building basements, for example. Archival packaging boxes have zero contact with paper documents, which is the direct barrier against mold of paper documents, and is also the most important component of the library environment13,14,15. The demand for archive packaging boxes has been on the rise, accompanied by increased expectations for quality and safety. Paper and paper-based products, especially corrugated fiberboard boxes, have shown potential in meeting these demands. However, traditional archive packaging box often falls short in preserving the freshness and safety of products over extended periods.

The concept of active packaging refers to the state of interacting with the product, packaging, and environment to monitor the food product and better protect its quality. Today, the process of adding materials that will add antimicrobial and antioxidant activity to the packaging has become widespread to provide better protection against microbiological risks. However, the additional processes applied to the packaging should not disrupt the basic functions of the packaging material. This is where nanotechnology comes into play. Today, thanks to nanomaterials (NPs), it is possible to design multifunctional packages at the point of shelf life, product protection, and monitoring16,17,18. The use of different types of NPs in paper production is becoming widespread to gain antimicrobial or antioxidant properties19. Applying nanotechnology to the conservation of heritage artifact-based objects can establish a foundation for innovative approaches that complement and enhance conventional methods of disinfection, treatment, and preservation. Alexandru Ilieș et al. studied the antibacterial effect of environmentally friendly silver nanoparticles on textiles20. Biopolymer coatings based on gelatin and gelatin incorporated with modified curcumin were successfully applied to paper. Coating significantly altered the morphological and structural properties of the paper, resulting in thicker materials with smoother and continuous surfaces. Coated paper with curcumin had antioxidant activity, and the presence of gelatin imparted heat-sealing ability to the paper21. Shiv Shankar et al. prepared low-density polyethylene nano-composite films for food packaging by using the blow molding method, adding citrus extract, melanin nanoparticles, and zinc oxide nanoparticles. These films can effectively reduce the water absorption and oil absorption rate of paper, and also effectively inhibit the growth of bacteria22. Kapphapaphim Wanitpinyo et al. fabricated paper packaging using paper coated with silver-exchanged zeolite. This method effectively enhanced the barrier properties and antibacterial activity of the paper packaging while maintaining good mechanical properties over an extended period23. In recent years, the superior physical barrier properties and multifunctional drug loading performance of hydrogels have been widely applied in the fields of medicine, materials, food, and cultural relic protection materials24,25,26,27. Selecting packaging materials with properties similar to those of the cultural relics themselves can effectively mitigate the stress differences between materials caused by environmental changes, which is crucial for the preventive protection of cultural relics28. Paper-based materials are biodegradable and renewable, effectively easing resource overconsumption and environmental pollution issues29. At present, in the research of preventive conservation, the main focus is on the study of the original objects of cultural relics. There are relatively few research groups studying the work of archival protection equipment. In preventive conservation, archival boxes are a valuable tool that can protect archival materials and effectively reduce the impact of external environmental disturbances on the original archives. Morana Novak proposed in her 2024 paper that before the publication of her paper, no method for evaluating the environmental conditions of paper-based archival boxes had been developed14. Effective mold prevention and micro-environment regulation of paper archives can be achieved through the packaging materials themselves, providing a new research idea for the preservation of paper archives. In the reinforcement and anti-mold protection of paper-based cultural relics, chitosan and its derivatives can inhibit various microorganisms, such as mold and bacteria, and through hydrogen bonds, they interlock with the long-chain paper fibers, enhancing the mechanical strength of the paper and improving the dispersibility of fillers.

In our previous research, it was found that the introduction of sodium octaborate tetrahydrate in archival packaging materials can effectively enhance the anti-mold and fire-resistant properties of the paper30. The stability of sodium octaborate tetrahydrate when in contact with the paper, after paper deposition, can effectively increase the alkali reserve of the paper and prevent paper acidification31. This study proposes a permeable packaging material, which is composed of quaternary ammonium salt chitosan (QCS) and polyacrylamide (PAM) Double-Network gel encapsulating inorganic NPs (Na2B8O13·4H2O) combined with paper fibers to form QCS/PAM-Na2B8O13·4H2O Hydrogel (QCB) (Fig. 1). In this study, this gel was applied to the packaging surface for the preservation of paper-based cultural relics to analyze its anti-mold mechanism. The mechanism of microbial damage caused by QCB double-network hydrogel for the anti-mold of paper-based cultural relics was explored through the combination of morphological and physiological changes of microorganisms and transcriptomic metabolomics analysis (Scheme diagram 1). This has proposed a new method for the protection of paper-based cultural relics and also provided new assistance for improving the archival environment (Table 1).

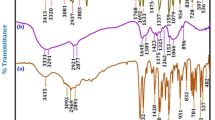

SEM (A) and FTIR (B) of QCB hydrogel. C Schematic diagram of the inhibition zone experimental design, D quantification of the inhibition zone effect of QCB and the radius of the inhibition zone, E shows the quantification of the radius of the antifungal zone and F observation of the damage effect of QCB on mold by scanning electron microscopy.

Methods

Materials

Na2B8O13·4H2O, N,N'-methylene bisacrylamide (BIS), acrylamide (AM), 3,8-Diamino-5-[3-(diethylmethylammonio)propyl]-6-phenylphenanthridinium diiodide(PI), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, mold (Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus flavus, P. citrinum, Cladosporium sp., Alternaria alternata, Trichoderma harzii, Mucor circinelloides) was derived from mold isolated from mold files.

QCB double-network hydrogel synthesis

QCS and Na2B8O13·4H2O were dissolved in 10 mL sterile deionized water, AM and BIS were added to the QCS solution, stirring for 30 min, blowing with nitrogen for 10 min to remove oxygen, and then coated on the surface of paper packaging. This was followed by 1 h of illumination under a UV lamp (365 nm, 20 W, 10 cm from the mold) to form the gel. Form QCS/PAM-Na2B8O13·4H2O Hydrogel (QCB) on the surface of the paper. After freeze-drying the samples, the surface morphology was observed by scanning electron microscopy, while the surface characteristic absorption peaks of the synthesized QCB samples were observed by infrared spectroscopy.

The antimold properties of the QCB hydrogel

Select Aspergillus niger, A. flavus, T. harzii, and M. circinelloides. Adjust the spore concentration to 1 × 103 CFU/mL and coat them evenly on PDA plates, respectively. The QAC—polyacrylamide solution-sodium octaborate tetrahydrate solution, and polyacrylamide were respectively placed on the PDA medium using Oxford cups. In addition, 200 μL of the QCB hydrogel and Solvent liquid were dropped into the drug-sensitive tablets, and the drug-sensitive tablets were placed on the PDA medium and left at 28 °C. Culture under 80% RH conditions.

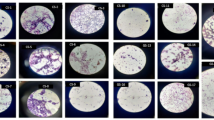

Different kinds of mold were inoculated on the plate, and the paper pieces of the ordinary paper and QCB hydrogel paper were placed on the plate, and then cultured at 28 °C for 24 h. The inhibiting effect of the paper on the mold was observed. The surface morphology of the paper was observed under an optical microscope.

The 1 × 104 CFU/mL of A. niger spores were uniformly sprayed on the paper, and the paper was placed in the ordinary paper box and the QCB hydrogel paper box, respectively, and the growth of the mold was observed after 45 days. The paper was taken out and dried at 37 °C, and then photographed by scanning electron microscope (SEM).

A. niger and Penicillium citrine cultured on PDA medium for about a week were washed with ultra-pure water, the mycelium was filtered by three layers of gauze, the filtrate was centrifuged, and the spores were collected and added to paperboard for treatment. Mold spores were placed on the surface of ordinary paper and on the surface of QCB-treated paper for culture, and the spores were collected after 6 h of culture. The collected spores were put into 3% (v/v) glutaraldehyde solution with pH = 7.0, 0.05 mol/L phosphate buffer. Then it was placed in a refrigerator at 4 °C for 12 h, washed with ultra-pure water every 20 min, and repeated three times. The rinsed samples were dehydrated with ethanol solutions of different concentrations. The concentration gradients of ethanol were 30%, 50%, 70% and 95%, and each gradient was treated for 20 min. At last, the samples were dehydrated with anhydrous ethanol for 45 min. The samples were then frozen overnight in an ultra-low temperature refrigerator at −80 °C and taken out. Then the samples were dried by a vacuum freeze dryer and sprayed with gold (120 s, 1.8 mA, 2.4 kV) by ion sputtering coating. Then, the structure and morphological changes of the mold were observed by SEM.

The activated mold was inoculated into the PDA medium plate and cultured in a constant temperature and humidity incubator at 28 ± 2 °C for a week. Then, the gray mold was picked up with sterilized tweezers and placed in a conical bottle containing a small amount of sterile water (glass beads were placed), and the filtrate was filtered with sterile gauze after shaking and dispersing. The number of spores was calculated using a blood cell counting plate. The spore suspensions of A. niger and P. citrine were adjusted to 1 × 105 CFU/mL, and then the shaken spore suspensions were added to the pasteurized PDB medium with a pipette gun, sealed with a sealing film, and placed in a shaking table at 28 ± 2 °C. Mold spores were placed on the surface of ordinary paper and on the surface of QCS/ PAM-Na2B8O13·4H2O-treated paper for culture, and the spores were collected after 6 h of culture (Scheme diagram 2). The spores were collected after 3 h of oscillating culture at 200 rpm/min and centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min. The collected spores were rinsed with PBS with pH = 7.0 and 10 mM for 2–3 times, then centrifuged, and then re-suspended with PBS containing 10 μg/mL PI. Then, the spores were treated at 28 ± 2 °C without light for 30 min for staining, centrifuged at 5000 rpm/min at room temperature for 5 min, and then washed with PBS for 2–3 times to remove the residual PI. Finally, the spores were resuspended in sterile water. Finally, the spores were re-suspended with sterile water and diluted to a suitable concentration. After absorbing 2 μL of the spore suspension, the morphology and staining of the spore were observed under an ordinary optical microscope and a fluorescence microscope. Three fields were randomly selected, and the number of spores in each field was about 100.

Mold spores with a concentration of 1 × 105 CFU/mL were prepared, and then 200 μL spore suspension was absorbed with a pipette gun and added to the PDB medium, which was packaged and sterilized, sealed with a film, and placed in a water bath thermostat at 28 ± 2 °C. After a week of oscillating culture at 150 rpm/min, the mycelium was collected by filtration with a circulating water vacuum pump, and rinsed with 0.1 M PBS with pH = 7.0 for 2–3 times. The 1.0 g wet heavy mycelium was weighed and re-suspended in 30 mL sterile water, and then incubated with file box cardboard. The supernatant was centrifuged at 1000 rpm/min for 10 min, and the supernatant was retained. Three replicates were set in each parallel group. The extrinsic conductivity of the mold was determined by a DDs-307A conductivity meter, and the pH was determined by a PBs-BW pH meter.

Liquid medium and spore suspension were prepared, and then 200 μL spore suspension was absorbed with a pipette gun and added into the liquid medium, that into QCB and destroyed by bacteria, sealed with film, placed in a water bath constant temperature oscillator, incubated at 28 ± 2 °C and 150 rpm/min for a week, and then filtered and collected mycelium with circulating water vacuum pump. Rinse with PBS of 0.1 M and pH = 7.0 for 2–3 times, weigh 1.0 g wet heavy mycelium and suspend it in 30 mL sterile water, add cardboard suspension, and continue to oscillate in a water bath thermostatic oscillator at 0, 30, 60, 120, respectively. One hundred twenty minutes later, sample 1000 rpm and centrifuge for 10 min, and retain the supernatant. The K+ content in the supernatant was determined by an AA7000 atomic absorption photometer.

A storage space of 1.2 m3 was designed, where water and glycerin were placed to adjust the relative humidity to about 80%. The 1 × 105 CFU/mL spore suspension was made from the separated mold spores, which were uniformly sprayed on the paper in the storage space and incubated for more than 2 months to form a simulated environment of high temperature and humidity.

Before sampling, the glass fiber filter membrane was put into the culture dish for 121 °C, 30 min high temperature and high pressure sterilization. After sterilization, it was dried and put into the super-clean table for use. Before sampling, a six-level sampler was set up at the sampling point, the sampling height was set at 1.5 m, and the six-level sampler was disinfected with 75% alcohol. After 10 min of vacuuming, the sampling starts. The sampling duration is 60 min. After sampling, the membrane samples were put into sterile centrifuge tubes with sterilized tweezers, refrigerated at −20 °C, and sent to the testing company in time for high-throughput sequencing(Scheme diagram 3).

Sequencing methods:

-

(1)

DNA purification of samples: gDNA was purified by Zymo Research BIOMICS DNA Microprep Kit (Cat# D4301), and gDNA integrity was detected by 0.8% agarose electrophoresis. This was followed by nucleic acid concentration detection using Tecan F200 (PicoGreen dye method).

-

(2)

PCR amplification: according to the sequencing region, a specific primer with an index sequence was synthesized to amplify the 16S rDNA V4 and ITS V1 regions of the sample. The amplification primer sequence was as follows: primer 5’–3’ :515F(5’-GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3’) and 806 R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’) F:GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG and R:GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC.

-

(3)

PCR product detection, purification, and quantification: the PCR product was mixed with a 6-fold loading buffer, and the target fragment was then detected by electrophoresis using a 2% agarose gel. The qualified samples were collected with the target strip, and the Zymoclean Gel Recovery Kit(D4008) was used for recovery. Quantification with Qubit@2.0 Fluorometer(Thermo Scientific); Finally, equimolar mixing.

-

(4)

Library construction: the library was built using the NEW ENGLAND BioLabs NEBNext Ultra II DNALibrary Prep Kit for Illumina(NEB#E7645L).

-

(5)

High-throughput sequencing: the PE250 sequencing method was adopted, and Illumina HiSeq Rapid SBS Kit v2(FC-402-4023 500 Cycle) was used as the sequencing kit.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 19.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) with Values expressed as means±standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were made using a one-way analysis of variance, and the differences between means were compared using Tukey’s test, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant and p < 0.01 as highly significant.

Results and discussion

Evaluation of the anti-mold performance of the QCB hydrogel

SEM observation showed that the synthesized QCB hydrogel had uniform porous results, formed protection on the surface of paper packaging materials, and played an effective antibacterial role (Fig. 1A). Infrared spectroscopy (Fig. 1B) showed that the gel had O–H stretching vibration characteristic peaks at 3300 cm−1 and C=O stretching vibration absorption peaks at 1700 cm−1. A C-O stretching vibration absorption peak exists at 1400 cm−1. The above results confirm that QCS and PAM are connected by amide bonds to form QCB hydrogel. Figure 1C shows the grouping of our inhibition zone experiment. In one petri dish, the upper two are the control groups, and the lower ones are the QCB and solvent control groups, respectively. The soaking solution of QCB hydrogel has a significant inhibitory effect on four kinds of microorganisms, and the bactericidal effect of the drug-sensitive tablets is consistent with that of Oxford cups. The polish solution soaked in paper has no obvious bactericidal effect (Fig. 1D). The quantification results of the inhibition zone show that the diameter of the inhibition zone in the drug-sensitive tablet is greater than 3 mm, and the detection results of the inhibition zone experiment in the Oxford Cup indicate that the diameter of the inhibition zone is greater than 19 mm, suggesting that the synthesized QCB gel has good antibacterial properties (Fig. 1E). It was observed by SEM that after the solution treatment of QCB hydrogel paper, the mold spores showed varying degrees of collapse and depression, the spores on the mold mycelium decreased, and the roughness on the spores decreased (Fig. 1F).

QCB hydrogel paper anti-mold effect

The synthesized QCB hydrogel paper was coated on the surface of the paper, and the antibacterial effect and surface morphology of the ordinary paper and the treated paper were compared. As shown in Fig. 2A, the mold color around the QCB hydrogel paper was weak and almost transparent, indicating that the QCB hydrogel paper had a good inhibition effect on all kinds of mold. In addition, when the paper of the two kinds of equipment is placed in the mold culture environment, as shown in Fig. 2B, the paper of ordinary paper turns black and becomes wet, while the paper of the QCB hydrogel paper remains unchanged (Fig. 3).

The paper packaging of QCB hydrogel paper treated before and after treatment is filled with filter paper inoculated with mold. After one month, the filter paper was placed in the culture medium,f respectively. A different mold appeared in the culture medium of the control group, while almost no mold appeared in the treatment group. However, the two kinds of filter paper that had been packaged and treated were placed in the humid culture environment again, the QCB hydrogel paper treatment group still did not breed new mold colonies, while the control paper was seriously affected, and the comparison effect was significant. The above results show that the packaging of paper treated with QCB hydrogel has a good inhibition effect on the mold of paper, and a large number of uses of the QCB hydrogel paper packaging in the library can effectively avoid the spread of bacteria and fungi in the contact process. At the same time, in the process of moving archive books, the packaging material can effectively avoid microbial erosion in the process of transportation and storage.

Mechanism of damage to A. flavus after loading paper treatment

The results of the effect of cardboard on the structure of mold spores are shown in Fig. 4A. As can be seen from the SEM, the mycelium and spores of the control group were full and full, and the surface was smooth. In the treatment group, the surface wrinkled and collapsed, the spores ruptured, and the contents leaked seriously. The above results suggest that after mold spores come into contact with paper, they can effectively damage the cell membrane structure of mold spores, resulting in varying degrees of collapse and depression. PI dye can penetrate the ruptured cell membranes to cause bright staining of mold cells. The staining results show that the cell membranes of mold spores in contact with the new type of file box have ruptured to varying degrees, resulting in red fluorescence in the mold cells. The same situation occurred in both A. flavus and P. citrinum (Fig. 4B).

The trend of the effect of cardboard treatment on the pH outside the spores of A. flavus as a function of concentration and time is shown in Fig. 4C. As can be seen from the figure, the control group showed a slight decrease in the extra-sporulation pH with the extension of the treatment time, and the change was not large. The extra-sporulation pH of all treatment groups decreased with the increase of treatment time, and the decrease rate was the fastest within 0–30 min. The decreasing trend of extra-sporulation pH was positively correlated with treatment concentration and treatment time. After 120 min of treatment, the pH value of the treatment group was 24.7% lower than that of the control group. According to the above experimental results, it can be speculated that the intracellular acidity of the mold, and the decrease of the extra-sporulation pH value may be the result of the release of acidic substances in the sporulation after the cell membrane is damaged. The changes in the extraporific conductivity of A. flavus after treatment with the cardboard suspension are shown in Fig. 4D. It can be seen from the figure that the control group did not show significant changes in its extra-sporulation conductivity as a function of treatment time. The extra-sporulation conductivity of the treatment group increased with the extension of treatment time. When the treatment time was 120 min, the extra-sporulation conductivity of the treatment group was 1.6 times that of the control group. According to the above results, it can be inferred that the paperboard treatment destroys the cell membrane, resulting in the release of conductive particles in the spore, which leads to the increase of extra-spore conductivity. The changes of K+ leakage in A. flavus cells treated with different concentrations of neotype cardboard suspension for different times are shown in Fig. 4E. As one of the important components in cells, K+ plays an extremely important role in regulating the balance of osmotic pressure inside and outside the sporulation and the function of various enzymes. It can be seen from the figure that the concentration of K+ in the control group, A. flavus cells, does not change with time. The concentration of K+ in the treatment group showed an overall trend of gradual increase with the extension of treatment time, and the increasing trend was the largest in the time period of 30–60 min, and the increasing trend began to decrease in the time period of 60–120 min. At 120 min of treatment, the K+ concentration in the treatment group was 11.75 mg/mL, which was 1.7 times that of the control group. In the above experimental results, the concentration change of K+ indicated that the cardboard suspension treatment may destroy the integrity of the cell membrane, resulting in the leakage of K+ from the spore, thus increasing the concentration of K+ outside the spore. The effect of cardboard suspension treatment on the leakage of A. flavus cell contents is shown in Fig. 4F. The figure shows that the absorbance value of the treated mold cell contents at 260 nm basically does not change with the change of treatment time. The absorbance value of the paper can be increased after processing, and it increases with the extension of processing time. When the treatment time was greater than 60 min, the rising trend was gradual. When the treatment time was 120 min, the absorbance values of the treatment group were 0.63, respectively, which tended to be gentle, but were all higher than the value of 0.26 of the control group. As can be seen from the above results, the content of cells increased after treatment, which is also presumed to be the result of the destruction of cell integrity.

Transcriptomic analysis

To study the effects of treatment on the gene expression of A. flavus during its growth process before and after treatment, the changes in gene expression levels between the blank control group and the paper treatment group were analyzed and compared, as shown in Fig. 5. There were a total of 330 differentially expressed genes, including 132 up-regulated genes and 198 down-regulated genes. The number of down-regulated genes of differentially expressed genes is higher than that of up-regulated genes, which indicates that after the multifunctional gel paper is treated, it mainly functions through down-regulated expression genes (Fig. 5A, B). Cluster analysis of differentially expressed genes is used to determine the expression patterns of differentially expressed genes under different treatment conditions (Fig. 5C). It mainly predicts the functions of positional genes by comparing their functions with those of known and similar genes.

Figure 6A shows that from the perspective of the cellular components classified by Gene Ontology (GO) annotation, the paper treatment mainly affected the composition of the cell membrane, the functions of organelles, etc. The main changes in biological processes include the metabolic processes of cells, cell composition, and the process of reproduction. The changes in cell composition mainly occur by influencing the important components of the cell membrane. The molecular functions mainly affect the catalytic activity of enzymes, the activity and metabolism of nucleic acid-binding transcription factors, etc., suggesting that the contact of paper with microorganisms in the environment mainly inhibits the growth and physiological metabolic functions of molds by influencing the regulation and expression of these genes. Figure 6B shows Ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes, the Pentose phosphate pathway, and Carbon metabolism of A. flavus treated with QCB hydrogel. The Biosynthesis of amino acids was significantly altered. These four pathways do not operate independently but form an interrelated core metabolic network. Their combined changes strongly indicate that gel treatment exerts significant environmental stress on A. flavus (such as nutritional stress, oxidative stress, or cell wall damage), compelling the fungus to comprehensively adjust its basal metabolism in response to the crisis. Ribosome biosynthesis has been significantly altered, and cells are globally adjusting their growth and proliferation plans. Upregulation indicates that A. flavus is attempting to synthesize a specific batch of proteins (such as stress proteins, detoxification enzymes) in response to the specific components in the gel. NADPH is a key molecule in biosynthesis (such as fatty acids and amino acids) and in resisting oxidative stress. If this pathway is upregulated, it strongly suggests that gel treatment has triggered oxidative stress, and the fungus requires a large amount of NADPH to maintain the operation of the antioxidant system (such as glutathione). Amino acid biosynthesis was significantly upregulated for the synthesis of stress-related proteins and resistant secondary metabolites. As shown in Fig. 6C, sample difference gene Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Pathway (KEGG Pathway) annotations classification as a result, the A. flavus transcriptome sequencing annotation to the KEGG database includes 70 differentially expressed genes in the genetic variations, including 38 KEGG metabolic pathways. There are 32 annotations to metabolic processes, 2 annotations to cellular processes, 3 annotations to genetic information processing, and 1 annotation to environmental information processing. During the metabolic process, five differentially expressed genes were annotated into the tyrosine metabolic pathway, five differentially expressed genes into the phenylalanine metabolic pathway, four differentially expressed genes into the fatty acid metabolic pathway, three differentially expressed genes into the tryptophan metabolic pathway, and three differentially expressed genes into the carbon metabolic pathway. Three differentially expressed genes were annotated into the amino acid bioanabolic pathway, and three differentially expressed genes were annotated into the unsaturated fatty acid bioanabolic pathway. During the process of environmental information processing, one ABC transporter is annotated. Among them, the rise in the main pathways, including ribosomal biosynthesis, peroxidase, carbon-containing compounds synthesis, and biosynthesis of amino acids, etc. The down-regulated pathways include processes such as tryptophan, arginine, proline, alpha-linolenic acid metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, tyrosine metabolism, and phenylalanine metabolism. It is suggested that our multi-functional gel paper mainly inhibits the growth of microorganisms by influencing the protein synthesis of mold cells and the synthesis of other organic substances. Meanwhile, during contact with microorganisms, it can also destroy the biological composition on the surface of microbial cells to kill them.

QCB hydrogel paper achieves powerful antibacterial effects by reprogramming the physiological activities of A. flavus at the gene transcription level. Its mechanism of action is two-pronged: on the one hand, it inhibits key metabolism; on the other hand, it induces stress defense, but the latter is not sufficient to reverse the overall metabolic collapse. Ribosomal biosynthesis & partial amino acid biosynthesis are upregulated: This might be a brief effort made by cells to synthesize a batch of specific stress repair proteins after sensing damage. When QCB hydrogel comes into contact with mold cells, its physicochemical properties (possibly by adsorbing key nutrients or releasing active functional groups) first disrupt the cell surface structure and trigger intense oxidative stress (upregulation of peroxidase genes). When the cell nucleus receives stress signals, it directly downregulates a large number of key metabolic genes, including those responsible for the synthesis of amino acids (tryptophan, tryptophan, proline, tyrosine, phenylalanine) and fatty acids. This cuts off the basic raw materials needed for growth from the root. Due to the inhibition of gene expression of raw materials (amino acids, fatty acids), protein synthesis and the synthesis of new cell membranes/cell walls have come to a standstill. Fungi are unable to grow, repair damage, and have incomplete membrane structures, ultimately leading to effective inhibition of growth until cell death.

LC-MS non-targeted metabolomics

Metabolites exhibiting a p-value of less than 0.05, a Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) score greater than 1, and a Fold Change (FC) exceeding 1 were identified as differential metabolites through principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). The findings were illustrated using a volcano plot and a VIP score plot. A total of 24822 differential metabolites were identified between the Control and QCB hydrogel treatment groups, with 9835 metabolites being up-regulated and 14,987 down-regulated, as depicted in Fig. 7A. For each group of comparisons, the Euclidean distance matrix was calculated for the quantitative values of the differential metabolites, and the differential metabolites were clustered by the complete linkage method, and the heat map was displayed. Here, taking the control group to the QCB hydrogel group as an example, the top ten differentially expressed substances with significant up-regulation and down-regulation were selected, respectively, as shown in Fig. 7B.

A Volcanic map of differential metabolism. The red dots represent significantly up-regulated metabolites, the blue dots represent significantly down-regulated metabolites, and the gray dots represent non-significantly differentiated metabolites. B Radar chart analysis for the group. C Statistics of differential metabolites in the KEGG pathway. D Enrichment analysis of differential metabolites by KEGG pathway.

Annotation and enrichment analysis of differential metabolites using the KEGG database revealed that Packaging treatment group influence alters metabolite expression, disrupting regulatory pathways and associating with phenotypic changes. Differential metabolites predominantly clustered in metabolism pathways (90.13%, number 177) and Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (39.17%, number 79). Within metabolism, ABC transporters (20.39%, number 37), Biosynthesis of amino acids (18.42%, number 35), and 2-Oxocarboxylic acid metabolism (13.16%, number 26) were the most frequently affected categories (Fig. 7C). Based on the enrichment results of differential metabolites in KEGG metabolic pathways, the Rich Factor (the ratio of the number of differential metabolites annotated in a pathway to the number of all metabolites in that pathway) was calculated, and a higher value indicated a greater degree of enrichment. The p-value is the p-value of Fisher’s test, and the calculation parameters used are the number of annotated differential metabolites in a pathway, the number of all metabolites in the pathway, the number of all annotated differential metabolites, and the number of all metabolites in the species. The KEGG enrichment map of differential metabolites is shown Fig. 7D. The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that differential metabolites were significantly enriched in the Metabolic pathways, Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, ABC transporters, Biosynthesis of amino acids, Biosynthesis of cofactors, 2-Oxocarboxylic acid metabolism, Nucleotide metabolism, and Amino acid Metabolism, with a significance level of p < 0.01. Additionally, significant enrichment was observed in Lysine biosynthesis, with a significance level of p < 0.05. QCB gel treatment triggered a fundamental metabolic reprogramming of A. flavus. The strategy of fungi is to fully switch from “growth mode” to “survival mode”, which is core manifested as: urgently halting cell growth and proliferation, and reallocating resources and energy to the defense and stress systems to cope with the huge pressure caused by QCB gel. Amino acid biosynthesis and amino acid metabolism, and lysine biosynthesis: as the cornerstones of proteins, the disruption of these pathways directly means that protein synthesis is globally inhibited. Fungi cannot or no longer need to synthesize new proteins to maintain growth. Nucleotide metabolism: As a building block of DNA and RNA, the disturbance of this pathway echoes the inhibition of “ribosomal biosynthesis” (from previous analysis), jointly demonstrating that cell division and proliferation activities have largely come to a standstill. Cofactor biosynthesis: Coenzymes and cofactors act as the “lubricating oil” for all metabolic reactions. The changes in this pathway indicate that the overall metabolic network of the cell is in an imbalanced and unstable state. Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites: This perfectly corresponds to the previously detected alkaloids, flavonoids, phenolic acids, etc. The activation of this pathway is solid evidence that fungi have initiated their “chemical defense system”. QCB hydrogel treatment (possibly through physical adsorption, chemical action, or triggering oxidative stress) causes initial damage to aflatoxin cells. QCB hydrogel forces A. flavus into a metabolic exhaustion defense state by triggering extensive metabolic stress. Its antifungal mechanism is multi-target, encompassing both indirect inhibition of primary metabolism leading to growth arrest and direct activation of the fungus’s own defense system (such as the ABC transporter), causing it to be overwhelmed. The ABC transporter and 2-oxy-carboxylic acid metabolism are highly promising targets for in-depth research. The expression changes of key genes in these pathways can be analyzed.

As shown in Table 2, we classified the metabolites after the treatment of QCB gel, mainly including peptides, glycerol phospholipids, fatty acids and derivatives, amino acids, fatty acylates carboxylic acids and their derivatives, sugar, alkaloid, nucleosides, organic heterocyclic compounds, phenolic acid flavonoids, nicotinic acid alkaloids, these products cover central carbon metabolism, amino acid metabolism, lipid metabolism, nucleotide metabolism and secondary metabolism, indicating that the treatment of QCB gel triggered global and profound metabolic recombination in fungi, rather than just minor adjustments in one or two pathways. The changes in glycerophospholipids, fatty acids, and their derivatives, and aliphatic acyl compounds, as well as the variations in their content and types, strongly indicate that QCB gel has disrupted the cell membrane integrity of A. flavus. Fungi are actively adjusting the composition of membrane lipids to maintain their fluidity and stability, which is usually an energy-consuming process. The changes in carboxylic acids and their derivatives suggest that the hubs of central carbon metabolism and energy production have been disturbed. These molecules (such as pyruvate, oxaloacetic acid, citric acid, etc.) are key intermediates in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and glycolysis. Their changes directly confirm the alteration of the “carbon metabolism” pathway, indicating that the energy factory of fungi is adjusting its production line. The accumulation or consumption patterns of amino acids can illustrate the issue. If the content of many amino acids rises, it may indicate that protein synthesis (consistent with the inhibition of “ribosomal biosynthesis”) is globally downregulated, leading to the accumulation of “raw materials”. Meanwhile, certain specific amino acids may be extracted for the synthesis of stress molecules. Nucleotides are the cornerstone of the synthesis of DNA and RNA. The changes correspond to the inhibition of “ribosome biosynthesis”, jointly demonstrating that the reproduction and growth activities of fungi have been severely curbed. QCB gel triggers a comprehensive defensive metabolic reprogramming of A. flavus by inducing oxidative stress and cell membrane damage. The strategy of fungi is to sacrifice growth and fully activate their chemical defense system (synthesis of antioxidant and antibacterial compounds) to maintain survival.

Environmental microbial community structure after the introduction of QCB hydrogel archival boxes

As shown in Fig. 8A, after 6 h of incubation by the air sedimentation method in the simulated library, the plates were covered with microorganisms, and after the introduction of archive equipment, the number of microorganisms in the library was significantly reduced. The number of mold settlements was less than 2500 CFU/m3 in 6 h.

The fungal species collected before treatment were mainly Ascomycetes (95.18%, 95.57% and 97.08%, respectively) and basidiomycetes (3.19%, 2.69% and 2.33%, respectively) (Fig. 8B). After the introduction of archive equipment, the proportion of Ascomycetes in the ambient air was significantly reduced. It is suggested that archival fixtures can effectively reduce the amount of mold in the environment. As shown in Fig. 8C, before the collection of fungal species, the main species were Aspergillus (respectively 71.28%, 62.23%, and 79.96%), Podospora (21.91%, 46.56%, and 58.12%), and after the introduction of archival furniture, the Aspergillus microorganisms in the environment were reduced to (21.91%, 46.56%, and 58.12%), and the Podospora microorganisms were reduced to (3.15%, 7.10%, and 2.09%). The microorganisms were more dispersed. Similar to the fungal results in the environment, the phylum-level species classification of bacteria changed from very concentrated before treatment to dispersed after treatment, and the introduction of archival equipment greatly reduced the number of dominant species. The proportion of bacteria in the simulated environment included Proteobacteria (99.44%, 98.71%, 95.22%, 99.35%, and 96.23%) (Fig. 8D), and the proportion of bacteria in the environment after the introduction of the archive equipment included Proteobacteria (54.19%, 44.04%, 47.10%, 61.11%, and 50.84%). The content of Firmicutes was increased (26.75%, 32.55%, 29.52%, 38.66%, and 15.42%) (Fig. 8E). The QCB hydrogel archival paper significantly alters the microbial ecological structure of the archival environment by continuously releasing active ingredients, successfully transforming a high-load, monotonous and high-risk microbial environment into a low-load, diverse and low-risk one, thereby achieving biological protection of archival documents. QCB gel archive paper continuously releases active ingredients, significantly altering the microbial ecological structure of the archive environment. It successfully transforms a high-load, monotonous, and high-risk microbial environment into a low-load, diverse, and low-risk one, thereby achieving biological protection of archive documents. QCB gel archive paper significantly reduces the total number of microorganisms in the air and on object surfaces, especially Aspergillus and Pseudomonas, which pose the greatest threat to archive protection. The equipment did not create a “sterile” environment (which is neither realistic nor necessary), but successfully regulated the community structure of microorganisms. It transforms an unstable “pathological” ecosystem dominated by a few harmful bacteria into a “healthy” one with a richer species and a more even distribution. It effectively inhibits the original microbial components, thereby achieving a new steady-state equilibrium in the case of a decrease in microorganisms.

Using QCS/PAM double network gel coated with Na2B8O13·4H2O as QCB hydrogel paper packaging material can effectively kill microorganisms in the preservation environment, mainly by affecting the composition and physiological process of mold spore cell membrane to inhibit the growth of microorganisms. The results of transcriptome and metabolome show that, Protein synthesis and other metabolic pathways were significantly affected by the contact treatment of mold spores with archive boxes, thereby inhibiting microbial growth. At the same time, this gel material can also effectively protect the packaged material from microbial erosion when used as a packaging material, which indicates that this new type of packaging material can be used as an archive protection device to help archives resist the harsh external pollution environment. In the simulated high temperature and high humidity environment, the introduction of new archival equipment can effectively suppress the number of fungi in the air, which provides a guarantee for the protection of paper cultural relics and the health of library staff.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any data based on experiments in humans or animals.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Xu, Z. & Geng, C. Color restoration of mural images based on a reversible neural network: leveraging reversible residual networks for structure and texture preservation. Herit. Sci. 12, 351 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Biodeterioration of collagen-based cultural relics: a review. Fungal Biol. Rev. 39, 39 (2022).

Zhao, M. et al. Microbial corrosion on underwater pottery relics with typical biological condensation disease. Herit. Sci. 11, 260 (2023).

Mazzoli, R., Giuffrida, M. G. & Pessione, E. Back to the past: “find the guilty bug—microorganisms involved in the biodeterioration of archeological and historical artifacts. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 6393–6407 (2018).

Petraretti, M. et al. Deterioration-associated microbiome of a modern photographic artwork: the case of Skull and Crossbones by Robert Mapplethorpe. Herit. Sci. 12, 172 (2024).

Xiong, J. et al. Microbial pollution assessment in semi-exposed relics: a case study of the K9901 pit of the mausoleum of emperor Qin Shihuang. Build. Environ. 262, 111744 (2024).

Skóra, J. et al. Assessment of microbiological contamination in the work environments of museums, archives and libraries. Aerobiologia 31, 389–401 (2015).

Simon, L. et al. Microbial fingerprints reveal interaction between museum objects, curators, and visitors. iScience 26, 107578 (2023).

Ashley-Smith, J., Burmester, A., Eibl, M. Climate for collections-standards and uncertainties. In Postprints of the Munich Climate Conference 7 to 9 November 2012 (Doerner Institut, Munich, 2013).

Rouchon-Quillet, V., Remazeilles, C., Bernard, J., Wattiaux, A. & Fournès, L. The impact of gallic acid on iron gall ink corrosion. Appl. Phys. A 79, 389–392 (2004).

Kolar, J. et al. Historical iron gall ink containing documents—properties affecting their condition. Anal. Chim. Acta 555, 167–174 (2006).

Institution B. S. Specification for Managing Environmental Conditions for Cultural Collections: PAS 198 (British Standards Limited, London, 2012).

Cao, Z. et al. Near-field communication sensors. Sensors 19, 3947 (2019).

Novak, M. et al. Evaluation and modelling of the environmental performance of archival boxes, part 1: material and environmental assessment. Herit. Sci. 12, 24 (2024).

Kompatscher, K., Kramer, R. P., Ankersmit, B. & Schellen, H. L. Indoor airflow distribution in repository design: experimental and numerical microclimate analysis of an archive. Buildings 11, 152 (2021).

Kouvati, K. et al. Leuco crystal violet-Pluronic F-127 3D radiochromic gel dosimeter. Phys. Med. Biol. 64, 175017 (2019).

Enescu, D., Cerqueira, M. A., Fucinos, P. & Pastrana, L. M. Recent advances and challenges on applications of nanotechnology in food packaging. A literature review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 134, 110814 (2019).

Huang, Y., Mei, L., Chen, X. & Wang, Q. Recent developments in food packaging based on nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 8, 830 (2018).

Youssef, A. M. & El-Sayed, S. M. Bionanocomposites materials for food packaging applications: concepts and future outlook. Carbohydr. Polym. 193, 19–27 (2018).

Ilieș, A. et al. Antibacterial effect of eco-friendly silver nanoparticles and traditional techniques on aged heritage textile, investigated by dark-field microscopy. Coatings 12, 1688 (2022).

Kennya Thayres dos, S. L., Jéssica de, M. F., Alcilene Rodrigues, M., Germán Ayala, V. Bilayer paper-gelatin films with modified curcumin for sustainable packaging applications. Polym. Adv. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.70342 (2025).

Shankar, S., Bang, Y. J., & Rhim, J. W. Antibacterial LDPE/GSE/Mel/ZnONP composite film-coated wrapping paper for convenience food packaging application. Food Packaging Shelf Life 22, 100421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2019.100421 (2019).

Kapphapaphim, W. et al. Enhancing antibacterial characteristics of paper through silver-exchanged zeolite coating for packaging paper. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 22, 171–179 (2025).

Wu, W. et al. Rheological and antibacterial performance of sodium alginate/zinc oxide composite coating for cellulosic paper. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 167, 538–543 (2018).

Peppas, N. Hydrogels in Medicine and Pharmacy; Volume 1 Fundamentals (CRC Press Inc., Boca Raton, 1986).

Ulanski, P. & Rosiak, J. M. The use of radiation technique in the synthesis of polymeric nanogels. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B 151, 356–360 (1999).

Kozicki, M. How do monomeric components of a polymer gel dosimeter respond to ionising radiation: a steady-state radiolysis towards preparation of a 3D polymer gel dosimeter. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 80, 1419–1436 (2011).

ISO 11799: 2015. Information and Documentation—Document Storage Requirements for Archive and Library Materials. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:11799:ed-2:v1:en (2015).

Jingting, F., Jing, W., Yingying, H., Dongming, Q. & Tao, C. Bio-based waterproof and oil-repellent coatings for paper packaging: synergistic effect of oleyl alcohol and chitosan on performance enhancement. Prog. Org. Coat. 208, 109526 (2025).

Bingjie, M. et al. Mould prevention of archive packaging based microenvironment intervention and regulation. J. Cult. Herit. 57, 16–25 (2022).

Xin, L. et al. Study on the fungicidal effect of Na2B8O13·4H2O combined with discontinuous vacuum treatment for mass sterilization on mold-infested paper. J. Cult. Herit. 74, 22–34 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Engineering Research Center of Historical and Cultural Heritage Protection, Ministry of Education, Shaanxi Normal University, for their support and research cooperation. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 22572155 and 22102094), the State Administration of Cultural Heritage Science and Technology Research Project (no. 2023ZCK028), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (no. GK 202205024 and GK202309016), the Science and Technology Projects of the National Archives Administration of China (no. 2022-B-007), and the Key Laboratory of Archaeological Exploration and Cultural Heritage Conservation Technology (Northwestern Polytechnical University), Ministry of Education (project no. 2024KFT05).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was prepared through the contributions of all authors. J.C. planned the study together with B.M., conducted all data analysis, and wrote most of the manuscript. Z.C., X.L., S.Y., and Y.L. designed part of the experiment. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, J., Chen, Z., Liu, X. et al. Smart packaging solution: Na2B8O13·4H2O-loaded QCS/PAM double-network hydrogel for microbial control in paper heritage preservation. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 654 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02212-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02212-w