Abstract

This study focuses on the three-dimensional visualization of intangible cultural heritage of the tie-dye handicraft, proposing a craft logic-oriented virtual modeling method to reconstruct fabric shaping and dyeing in virtual space. Based on a particle system, it adds stretching, bending, and penetration constraints for an operation-responsive fabric structure, with bending constraint tolerance adjusted to simulate fabric stiffness. It virtualizes four key shaping operations, including folding, twisting, bundling, and clamping via geometric positioning, external forces, and constraints, respectively. For dyeing, it uses spatial confinement calculations to determine fabric sections’ dyeability for pattern generation and prediction. A comparative analysis of 3 virtual vs. real patterns (via image feature extraction and cluster analysis) showed virtual-real differences smaller than real patterns’ inherent variations, confirming the model’s fidelity and reliability. This provides a practical pathway for modeling traditional handicrafts, and also brings inspiring ideas for extending visual models to non-static, procedural targets in heritage preservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tie-dye is an ancient traditional printing technique. Through manual operations such as folding, binding, and compressing, it creates regions with varying dye receptivity on the fabric, resulting in diverse patterns after immersion in dye. The history of Chinese tie-dye can be traced back to the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317-420 AD), reaching its zenith during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD) and once widely disseminated across East and South Asia1. Japanese Shibori, Indian Bandhani, and Chinese tie-dye each possess distinct characteristics while sharing fundamental techniques like tying, clamping, and stitching. Currently, Chinese tie-dye is primarily practiced in ethnic minority regions of Yunnan, Guizhou, and Sichuan provinces, each with unique stylistic features. Recognized as national intangible cultural heritage, examples include those shown in Fig. 1.

With the rapid advancement of digital technology, the preservation and transmission of cultural heritage have entered a new phase. The application of three-dimensional visualization models has significantly propelled the recording and exhibition of cultural heritage, while also providing innovative tools for its modeling, restoration, and risk assessment.

Currently, 3D models are primarily used for the exhibition and publicity of cultural heritage, offering proxy access to otherwise inaccessible assets. Online exhibitions built on 3D models allow global audiences to remotely explore underwater cultural heritage sites like those off Sicily2. Immersive 3D environments created with VR technology present archeological artifacts within realistic contexts of their original sites, enhancing audience understanding and memory3,4. In 3D model worlds incorporating AR and XR technologies, users can explore and practice by manipulating virtual objects, leading to more interactive and engaging learning experiences5,6. Advancements in spatial data acquisition techniques—from photogrammetry7 and structured light scanning8 to laser scanning9 and drone scanning10 —yield increasingly precise and detailed 3D point clouds, facilitating the creation of realistic and comprehensive “digital twins” of cultural heritage11,12. The integration of IoT and next-generation sensor technology further enables the real-time acquisition of precise asset states, supporting dynamically updated 3D models13. Notably, extensive research on 3D models is continuously unlocking their potential and explanatory power, extending their utility beyond visualization to serve broader purposes14, including:

-

Reconstruction and Restoration. Detailed geometric analysis on 3D models can reveal the principal forms and overall structures of cultural heritage assets with high precision. This facilitates the restoration of missing parts on ancient Greek warships15, the reconstruction of facial bones and tissues of ancient humans16,17, or the reassembly of fragmented medieval painted terracotta sculptures18. Such virtual reconstruction, based on historical evidence and archeological data, aids in understanding the original appearance and function of cultural heritage, enabling deeper historical and archeological interpretation19. Furthermore, by evaluating and optimizing restoration measures on digital models, it minimizes the risk associated with physical interventions after conservation planning20.

-

Comparison and Identification. Comparing 3D models created at different time points allows monitoring changes or deterioration patterns in cultural heritage assets, informing conservation strategies21. By comparing two photogrammetric models of the Omega House created in different years, researchers identified patterns of structural change over time22. When 3D models are acquired in real-time, the resulting timeline of digital twins can monitor immediate changes at heritage sites under natural disasters and climate change23. Comparative studies of 3D models from different artifacts or sites can identify similarities, differences, or evolutionary patterns. For instance, search engines like ArcheoShape use 3D shape descriptors to retrieve similar archeological objects, enabling comparison and classification based on geometric properties, potentially revealing hidden patterns and relationships between different cultural heritages24.

-

Simulation and Prediction. Potential damage or unstable areas can be inferred from 3D models to assess the current or future state of cultural heritage assets. Using nonlinear finite element methods and fuzzy inference approach on 3D models of historical buildings, researchers have simulated structural degradation to evaluate seismic resistance25, weathering trends26, and future risks27. Proposed multi-level, heterogeneous digital twin frameworks aim to incorporate complex sociological variables, enabling 3D models to predict future indicators of cultural heritage using big data and AI methods28.

Cultural heritage encompasses tangible heritage based on physical existence (e.g., ancient buildings, heritage sites) and intangible heritage rooted in traditional knowledge (e.g., rituals, handicrafts)29. Owing to their inherent physical form, tangible heritage has become a field where visualization models are intensively applied. As observed, existing methods and models—whether for virtual display, reconstruction, comparison, or prediction—are exclusively developed for tangible heritage. When this paradigm is transferred to intangible heritage (e.g., traditional handicrafts), it often only covers the tangible components of the heritage (e.g., tools, raw materials, finished products), leaving these elements in an isolated state without forming an organic system, as shown in Fig. 2. The missing components are precisely the intangible parts of the heritage, which constitute the core of the heritage. Therefore, intangible heritage poses a unique challenge to the application of visualization models: it requires breaking free from the limitations of static tangible entities and enabling the model to convey the rules and processes of traditional knowledge.

To proactively address this challenge, our research focuses on traditional tie-dye craftsmanship and constructs a visualization model for dyeable fabrics. Rather than merely reflecting the existing state and surface structure of the fabric, this model is dedicated to exploring the transformation logic underlying dyeable fabrics—specifically, the mechanisms of fabric shaping and coloring—and integrating this logic into the physical model. This endows the virtual fabric with the capability of shaping and dyeing, which compensates for the key intangible components of heritage in virtual space and reproduces the organic process of traditional craftsmanship.

Methods

Fabric model

Fabric is the central object in tie-dye craft and all craft operations are performed upon it. This establishes fabric as the primary carrier of the visualization model. Simultaneously, fabric is the tangible element of the traditional craft. To reflect the transformation of craft process through the fabric requires modeling oriented towards craft logic. In tie-dye, the underlying craft logic primarily encompasses two stages: shaping and dyeing.

Shaping is characteristic of traditional tie-dye. The fabric shaping process is defined by two key features: (1) Fabric morphology is manually shaped using a series of classifiable hand techniques. (2) Manual operations induce minimal stretching but significant bending and compression of the fabric. In other words, the bending stiffness of the fabric significantly influences the shaped morphology, while the effect of tensile strength is negligible. Therefore, our model focuses on realizing the dynamics of fabric under manual operations and the impact of fabric stiffness on morphology, aligning with the characteristics of the shaping process. We achieve this by constructing a bounded particle system.

Tie-dye fabric typically uses woven inelastic cotton cloth formed by two sets of interlaced yarns, presenting uniformly distributed interlacing points on the fabric surface (Fig. 3a). In virtual space, these interlacing points are represented by a particle array, constituting the initial prototype of the fabric (Fig. 3b).

Particles are mass points obeying Newton’s laws of motion. Their instantaneous velocity (V) and spatial position (P) at any given time are determined by solving Newton’s equations of motion:

Where F is the external force, \({P}_{p{rev}}\) is the particle’s position at the previous timestep, \({V}_{p{rev}}\) is the particle’s velocity at the previous timestep, and ∆t (∆t → 0) is the timestep increment. Since the initial positions of particles in the array are known and their initial velocities are zero, iterative calculations using the above formulas along the timeline yield the spatial position of any particle at any time. Thus, we obtain a particle system with dynamics, capable of responding to forces applied during manual operations. However, the particle responses are isolated and the internal structure of the particle system is not yet established.

In real fabric, interlacing points are connected by yarns, resulting in interactions. These interactions resist fabric deformation, tending to restore the initial distance between interlacing points and maintain the original shape. In virtual space, constraints30 are used to represent these interactions (Fig. 4).

Two types of constraints exist: stretching constraints and bending constraints. Directly adjacent and diagonally adjacent particles possess stretching constraints, counteracting stretching and contraction in all directions across the fabric surface to preserve its planarity. Particles separated by two units in the warp/weft direction possess bending constraints, counteracting displacement normal to the fabric surface to resist bending. Both stretching and bending constraints influence particles by correcting the distance between them, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Consider a particle pair a,b with an initial distance \({l}_{0}\). At a given time, their spatial positions are \({P}_{a},{P}_{b}\). The current distance is \(l=\left|{P}_{a}-{P}_{b}\right|\), and the distance change is \(\Delta l=l-{l}_{0}\). The constraint moves the involved particles in the direction that minimizes \(\left|\Delta l\right|\):

Where \({P}_{a}^{{\prime} },{P}_{b}^{{\prime} }\) are the corrected positions, and NORM is the spatial vector normalization operator, used to extract the vector direction. In these formulas, particles a,b move equal distances, each half of \(\Delta l\). Considering particles a,b may have different masses \(({m}_{a},{m}_{b})\), the particle with larger mass should move a smaller distance. The formulas are thus refined:

Through these constraints, the internal structure of the particle system is perfected, enabling it to react as a cohesive whole to external forces.

As mentioned earlier, the correction in Eq. (4) returns particles a, b to their initial distance, representing an intolerant or unreserved correction. When applied to stretching constraints, it signifies that the fabric cannot be stretched or compressed, aligning with the characteristics of tie-dye shaping. However, the shaping process involves significant fabric bending. Therefore, for bending constraints, a tolerant correction is necessary to allow varying degrees of bending deformation in tie-dye fabric. To achieve this, a stiffness coefficient \(\sigma (0 < \sigma < 1)\) is introduced, adjusting Eq. (4) to:

The stiffness coefficient σ effectively controls the tolerance to bending deformation. A larger σ results in a larger correction magnitude, less tolerance to deformation, and macroscopically manifests as higher fabric stiffness. When \(\sigma \to 1\), the fabric approaches a rigid body, becoming difficult to bend. Values of σ between 0 and 1 result in fabric exhibiting varying degrees of bending morphology, reflecting the influence of stiffness, as shown in Fig. 6.

In Fig. 6, the fabric is folded. Under its own weight, bending occurs near the fold line. The fabric structural units encompassed by the bent section are termed the bending length (indicated by arrows). According to textile mechanics, there is a monotonically increasing functional relationship between fabric stiffness and bending length. The figure shows that the bending length increases with rising σ, indicating a concurrent increase in fabric stiffness. Furthermore, the bending length can be used to unify real and virtual fabrics. By measuring the bending length of real fabric and ensuring the structural units and bending length of the virtual fabric match, a virtual clone of the real one that is suitable for tie-dye shaping can be obtained.

Significant bending and compression during tie-dye shaping can easily cause penetration phenomena in the fabric model. This is particularly evident after rendering, becoming a visual artifact (Fig. 7a). The particle array constituting the virtual fabric contains numerous voids. During shaping, moving particles can pass through these voids, causing penetration. While in real fabric, the surface is densely filled with interlacing points without gaps, preventing penetration.

Therefore, we address this by filling the voids in the model and introducing penetration constraints. First, particles are assumed to be spheres with a specific size. The particle diameter d is set equal to the spacing between particles in the array, enabling them to fill the voids. Second, the output positions are further corrected to separate penetrating particles. For any particle pair a,b, if their distance is less than the diameter d, they are in a penetrating state, requiring position correction. The correction, similar to the stretching constraint, restores their distance to d, achieving separation:

Where \({P}_{a}^{{\prime} {\prime} },\,{P}_{b}^{{\prime} {\prime} }\) are the corrected positions, and the distance change \(\Delta d=\left|{P}_{a}^{{\prime} }-{P}_{b}^{{\prime} }\right|-d\). After applying the constraints, the fabric state is as shown in Fig. 7b, eliminating penetration.

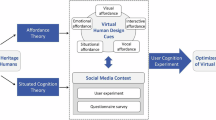

In summary, our model calculates particle velocity and displacement based on Newtonian mechanics according to applied forces. It uses stretching constraints to ensure structural integrity, tolerant bending constraints to control stiffness, and penetration constraints to eliminate penetration artifacts. Finally, it outputs particle positions corrected by the constraint mechanism. The operational framework is shown in Fig. 8.

This model is a self-organizing system capable of reacting as a cohesive whole to applied external forces and adjusting its morphology. Simultaneously, it is an iterative simulation system, driving fabric morphological changes through iterative calculations along the timeline, realizing the dynamics of manual operations. The speed of change is controllable via the timestep ∆t in Eq. (1). Setting ∆t = 0 freezes the fabric, while ∆t > 0 activates it.

Shaping methods

The fabric model can alter its morphology under external forces, possessing shaping capability. Building upon this, we propose methods and steps for realizing common shapes corresponding to tie-dye shaping operations. The rich diversity of tie-dye patterns stems from the flexible variations in manual shaping. Exhaustively modeling all possible fabric morphologies is infeasible. Therefore, we decompose the shaping process, extracting fundamental, common operational units for implementation on the fabric model. Based on observation and understanding of the traditional craft, we identified four basic operations: folding, twisting, bundling, and clamping.

Folding is the most common shaping operation. Varied folding forms help generate diverse tie-dye patterns. The spatial positions of fabric sections after folding can be roughly calculated. Therefore, folding of the virtual fabric is achieved by assigning coordinate positions to relevant particles. The specific steps are: First, freeze the fabric. Second, rotate a portion of particles 180 degrees around the fold line. Finally, activate the fabric (Fig. 9a).

Figure 9a illustrates basic half-folding: particles are moved to designated positions while frozen, resulting in a naturally bent appearance upon release. By superimposing the basic folding methods on the fabric model, various complex folded configurations can be created, as shown in Fig. 9b.

Twisting involves pressing the fabric center with fingers and rotating, causing the fabric to contract spirally. The complex morphology formed by twisting is difficult to achieve by assigning coordinates or fixing points. Therefore, it is implemented by applying extra forces (Fig. 10a).

During twisting, fabric sections move towards the center while rotating. This displacement can be decomposed into tangential and centripetal components. Hence, tangential and centripetal forces are introduced. Using the twist center as the origin and the particle’s distance to the center as the radius, each particle is assigned a tangential force perpendicular to the radius and a centripetal force pointing towards the center along the radius (Fig. 10a). These extra forces participate in driving the particles according to Eqs. (1) and (2). After a sustained period, the fabric forms the morphology shown in Fig. 10b, closely resembling real twisted fabric.

Bundling uses auxiliary cords to tightly bind the fabric, maintaining or reinforcing the formed shape (Fig. 11a). Bundling induces complex compressive interactions between fabric sections, difficult to achieve solely by applying forces. Therefore, it is implemented using external constraints.

External constraints confine particle movement within designated containers, achieving gathering and compression of the fabric. The principle is similar to internal constraints between particles, with one key difference: internal constraints act between particles, while external constraints act between particles and external containers. Consequently, corrections from internal constraints are mutual (both particles participate in position correction, sharing the correction magnitude ∆l, as in Fig. 5). Corrections from external constraints are unilateral: the particle bears the full correction magnitude, while the container boundary remains fixed (Fig. 12a).

In Fig. 12a, a simple round container confines particles within its interior, correcting the position of any escaping particle radially back to the boundary. Extending this round container with a certain thickness yields the waisted, open-capped cylinder shown in Fig. 12b, serving as the external container for bundling. The cylinder’s height corresponds to the cord diameter, and its diameter corresponds to the bundling circumference. When a particle moves within the cylinder’s height range but outside its surface, the external constraint activates, correcting the particle radially inward to the cylinder surface. Simultaneously compressing the cylinder’s diameter gradually tightens the cord, visualized in Fig. 11b.

Clamping uses auxiliary clamps or tablets to compress the shaped fabric (Fig. 13a). The corresponding external container is a capped, non-waisted cylinder (Fig. 12c). The cylinder’s caps correspond to the contact surfaces of the clamp/fabric, and its height corresponds to the clamped fabric thickness. When a particle’s projection along the central axis falls into the cylinder’s cap and lies outside the height range, the external constraint activates, correcting the particle to the nearest projection point on the cap. Simultaneously compressing the cylinder’s height gradually compresses the fabric beneath the clamp (Fig. 13b).

By introducing container-based external constraints, the fabric model gains the ability to incorporate auxiliary tools. Morphologically, containers can be cylindrical or prismatic (Fig. 13c). Switching between them requires merely adapting the mechanism determining the positional relationship between particles and the container’s caps.

Through this craft-logic-oriented modeling, we have realized the shaping process on the fabric model, embedding the intangible craft process within a tangible model. This allows our visualization model to transcend static, superficial representation and fully map the traditional craft process.

Dyeing method

Another underlying logic of craft in fabric is dyeing. In the final stage of the traditional process, shaped fabric is immersed in dye liquor. Areas subjected to compression resist dyeing, remaining white, while uncompressed areas readily absorb dye, generating blue-and-white patterns on the fabric. Compression induced by shaping operations manifests in two ways: First, within the direct action range of the shaping operation, significant compression creates hard-to-dye regions, leaving prominent white areas in the pattern. Second, beyond this range, interactions between different fabric sections caused by the shaping operation can induce indirect compression. Within wrinkles and folds created by shaping, regions with intermediate dyeability emerge, capable of light dyeing (Fig. 14).

The figure shows the tie-dye pattern from the bundled fabric in Fig. 11a. The cord’s direct action creates hard-to-dye regions, corresponding to the most prominent horizontal white stripe; wrinkles and folds induced by the bundling operation create longitudinal, tentacle-like regions of light dyeability; the remaining uncompressed areas, heavily dyed, are easy-to-dye regions.

Compression from shaping operations, whether direct or indirect, places the affected fabric sections in a state of confinement, preventing or hindering dye liquor penetration. Conceivably, the higher the degree of confinement in a fabric region, the lower its dyeability. Therefore, we implement the dyeing process and predict the final pattern on the fabric model by evaluating the confinement level of particles within their surrounding space.

As mentioned earlier, particles were assigned a size to solve penetration. This provides the basis for evaluating particle confinement. The space occupied by the fabric is subdivided into contiguous cells. The cell size equals the particle diameter, allowing exactly one particle per cell. The confinement level of a particle is quantified by the number of occupied neighboring cells surrounding it (Fig. 15).

In the simplified 2-D space shown, the particle being evaluated has 23-1 = 8 neighbor cells. These neighbor cells can be occupied by other particles or containers. The rules are:

-

If any particle’s center point is located within a neighbor cell, or if any container intersects its area, the cell is occupied, and the particle’s occupied neighbor count increases by 1.

-

The particle’s confinement level = occupied neighbor count / total neighbor count. Take the particle in Fig. 15 for example, its occupied neighbors = 4, so confinement level = 0.5.

This principle also applies to 3-D space, with the only difference being 33-1 = 26 total neighbor cells per particle. Calculating the confinement level for each particle in the shaped virtual fabric within 3-D space yields the fabric’s dyeability distribution (Fig. 16).

Figure 16a shows folded virtual fabric after bundling. Figure 16b depicts the particle system behind the virtual fabric, with particles colored according to their dyeability. It shows: the lowest dyeability (hard-to-dye) occurs in the region directly acted upon by the cord; the highest dyeability (easy-to-dye) occurs at the fabric ends farthest from the cord; and intermediate dyeability occurs within wrinkles and folds induced by the cord’s action. This distribution aligns with empirical knowledge. Therefore, by evaluating particle dyeability and coloring particles accordingly, the dyeing process can be realized on the fabric model. Figure 16c shows the colored and flattened virtual fabric, and the pattern closely resembles the real one in Fig. 14.

Results

The above model demonstrates its capability in fabric shaping and dyeing, recreating the process of traditional craft within virtual space. However, thus far, judgments of visualization effects—both shaping and dyeing—have been based on experience or intuition. The model’s validity requires further verification. Therefore, we manually crafted three representative tie-dye patterns in a real environment. The same tie-dye operations were then conducted on the model to generate virtual patterns. The virtual patterns were compared with the real patterns to examine their differences.

Radial pattern

The fabric corner was folded back and forth, followed by equidistant bundling from top to bottom. The resulting dyed pattern is shown in Fig. 17a. On the model, “folding” and “bundling” were combined to reconstruct the process (Fig. 17b).

Grass pattern

The fabric center was pressed and rotated, causing spiral contraction towards the center. The contracted fabric was then secured by bundling. The resultant pattern is shown in Fig. 18a. On the model, “twisting” and “bundling” were combined to reproduce it (Fig. 18b).

Grid pattern

The four corners of the fabric were repeatedly folded towards the center and fixed with clamps. The resultant pattern is shown in Fig. 19a. On the model, “folding” and “clamping” were combined (Fig. 19b).

Discussion

Intuitively, the three pattern pairs appear similar. However, a key challenge for validation is the inherent randomness of tie-dye patterns. In practice, even under identical processes and conditions, no two handcrafted tie-dye patterns are exactly the same, as illustrated in Fig. 19.

For each of the three patterns above, we conducted five manual productions under identical conditions. For group 1, we obtained five real patterns (1-1, 1-2, …, 1-5) and one virtual computational pattern (1-6). Similarly, group 2 had real patterns 2-1 to 2-5 and virtual pattern 2-6; group 3 had real patterns 3-1 to 3-5 and virtual pattern 3-6. As Fig. 20 shows, the five real patterns within a group are structurally similar but exhibit detail variations.

Therefore, the visual similarity between a virtual pattern and a real pattern is insufficient proof of validity. Conversely, even if a virtual pattern differs significantly from one particular real instance (e.g., 1-6 vs 1-2), it does not prove invalidity. This complicates the validation work.

Our solution is to examine the distance between the virtual pattern and the real patterns within its group. If this distance is smaller than the average distance between the real patterns themselves, it indicates that the virtual pattern can harmoniously blend into the group of real patterns, validating the model. Otherwise, it is invalid.

To calculate pattern distances, the Haar transformation was applied to each pattern, yielding a feature vector representing the pattern. Haar features are invariant to spatial transformations (translation, scaling & rotation), mitigating interference from relative movement. The difference between the two patterns is then expressed as the Euclidean distance between their feature vectors. For each group, patterns were preprocessed into feature vectors. Hierarchical clustering was performed on the six feature vectors (5 real plus 1 virtual), iteratively merging the two closest samples (or sample clusters) based on Euclidean distance until all samples form one cluster. The hierarchical structure is represented by a binary tree dendrogram, where each binary joint (from right to left) connects the two closest samples/clusters. The clustering structures for the three groups are shown in Fig. 21.

Observing the topmost binary joints (highlighted in red): If sample #6 (virtual) connects at the topmost joint, meaning the samples split into two clusters (#6 vs #1-#5), then the distance between the virtual and real patterns is larger than the distances within the real patterns. Conversely, if sample #6 does not connect at the topmost joint, it indicates the virtual-real distance is smaller than the intra-real distances. As seen in Fig. 21, all three cases belong to the latter scenario. This demonstrates that the virtual patterns integrate well with the real patterns; their differences from the real patterns are smaller than the possible differences among the real patterns themselves. Thus, our model and its pattern generation are proven valid.

Evidently, the innovative cloth model for handicraft and dyeability algorithms has successfully established a visualization system capable of demonstrating the process of traditional craftsmanship. In the craft-logic-oriented modeling, a mechanics and constraint model based on a particle system effectively captured the operational characteristics of minimal stretching, significant bending, and high compression inherent in manual fabric manipulation. The introduced fabric stiffness mechanism ensured that morphological changes in the virtual space align with the real world. For the shaping process, we mapped four fundamental manual operations: folding, twisting, bundling, and clamping. While not exhaustive, this demonstrates the model’s potential for implementing more complex shaping operations. For the dyeing process, we proposed calculating particle dyeability via spatial confinement, achieving computable pattern generation within the fabric model for the first time. This transforms the experiential knowledge of “dyeability” in traditional craft into a quantifiable metric, enhancing the model’s scientific rigor and controllability. Validation through image feature extraction and hierarchical clustering of real and virtual patterns confirmed the virtual patterns’ validity, proving the model’s ability to reproduce the traditional process while also possessing predictive power for the final product.

Furthermore, mapping the process of traditional craftsmanship into virtual space not only enhances the model’s visualization effect but also suggests broader application possibilities. Notably, the ability to generate patterns without physical implementation can significantly improve pattern design efficiency and optimize the tie-dye process itself. This extends the utility of the 3-D model beyond mere visualization, enabling reflection upon the real world, inspiring new paradigms for integrated virtual-physical heritage preservation.

In summary, by conducting transformation logic-oriented modeling on physical objects, we have constructed a bridge for the conversion between heritage elements in virtual space. This approach integrates isolated elements into an organic whole, breaks through the static constraints of physical entities in the visualization model, and realizes the transmission of knowledge and processes—thereby truly achieving the complete visualization of intangible heritage. This effective method of embedding intangible, procedural content into visualization models holds significant implications and application value for fields such as digital humanities, craftsmanship simulation, and virtual cultural heritage preservation.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Sun, Y. & Liu, M. In 7th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2021). 135−139 (Atlantis Press).

Bucci, G. The WAS Project—Waterscape Archaeology in Sicily at Isola delle Femmine (PA, Italy): Submerged and Emerged Heritage. Heritage 5, 2773–2803 (2022).

Bruno, F. et al. From 3D reconstruction to virtual reality: A complete methodology for digital archaeological exhibition. J. Cult. Herit. 11, 42–49 (2010).

Ch’Ng, E., Li, Y., Cai, S. & Leow, F.-T. The effects of VR environments on the acceptance, experience, and expectations of cultural heritage learning. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 13, 1–21 (2020).

Aliprantis, J. & Caridakis, G. A survey of augmented reality applications in cultural heritage. Int. J. Comput. Methods Herit. Sci. 3, 118–147 (2019).

Zhang, K., Luo, J. & Pan, Y. Design and evaluation of touch and touchless interfaces for interactive digital heritage experiences. Herit. Sci. 13, 313 (2025).

Lauro, V. & Lombardo, V. The Cataloging and Conservation of Digital Survey in Archaeology: A Photogrammetry Protocol in the Context of Digital Data Curation. Heritage 6, 3113–3136 (2023).

Bruno, F., Bianco, G., Muzzupappa, M., Barone, S. & Razionale, A. V. Experimentation of structured light and stereo vision for underwater 3D reconstruction. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 66, 508–518 (2011).

Liu, S. & Bin Mamat, M. J. Application of 3D laser scanning technology for mapping and accuracy assessment of the point cloud model for the Great Achievement Palace heritage building. Herit. Sci. 12, 153 (2024).

Mackinnon III, S. The ontological multiplicity of digital heritage objects: 3D modelling in the cherish project. Heritage 6, 1397–1410 (2023).

Themistocleous, K., Evagorou, E., Mettas, C. & Hadjimitsis, D. In Earth Resources and Environmental Remote Sensing/GIS Applications XIII Vol. 12268, 55-64 (SPIE, 2022).

Vuoto, A., Funari, M. F. & Lourenço, P. B. Shaping digital twin concept for built cultural heritage conservation: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 18, 1762–1795 (2024).

Pepe, M., Alfio, V. S., Costantino, D. & Herban, S. Rapid and accurate production of 3D point cloud via latest-generation sensors in the field of cultural heritage: a comparison between SLAM and spherical videogrammetry. Heritage 5, 1910–1928 (2022).

Scopigno, R. Sampled 3D models for Cultural Heritage: which uses beyond visualization?. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 3, 109–115 (2012).

Arapakopoulos, A. et al. 3D Reconstruction & Modeling of the Traditional Greek Trechadiri: “Aghia Varvara. Heritage 5, 1295–1309 (2022).

Tong, Y., Cai, Y., Nevin, A. & Ma, Q. Digital technology virtual restoration of the colours and textures of polychrome Bodhidharma statue from the Lingyan Temple, Shandong, China. Herit. Sci. 11, 12 (2023).

Papagrigorakis, M. J. et al. An Integrated Study of the Mesolithic Skeleton in Theopetra Cave, Greece: From the Skeleton Analysis to 3D Face Reconstruction. Heritage 5, 881–895 (2022).

Di Angelo, L., Di Stefano, P. & Guardiani, E. A review of computer-based methods for classification and reconstruction of 3D high-density scanned archaeological pottery. J. Cult. Herit. 56, 10–24 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Using Source Feature Matrix for interpreting the result in virtual reconstruction of cultural heritage sites. Herit. Sci. 13, 83 (2025).

Ma, Y., Tong, Q., He, X. & Su, B. Exploring virtual restoration of architectural heritage through a systematic review. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 167 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. A review of the tools and techniques used in the digital preservation of architectural heritage within disaster cycles. Herit. Sci. 11, 199 (2023).

Panagiotopoulou, A., Wallace, C. A. B., Ragia, L. & Moullou, D. Change Detection between Retrospective and Contemporary 3D Models of the Omega House at the Athenian Agora. Heritage 6, 1645–1679 (2023).

Themistocleous, K. in Earth Resources and Environmental Remote Sensing/GIS Applications XV Vol. 13197, 290-294 (SPIE, 2024).

Jiménez-Badillo, D., Mendoza-Montoya, O. & Ruiz-Correa, S. Application of computer vision techniques for 3D matching and retrieval of archaeological objects. F1000Research 12, 182 (2024).

Gil-Martín, L. M., Hdz.-Gil, L., Kohrangi, M., Menéndez, E. & Hernández-Montes, E. Fragility curves for historical structures with degradation factors obtained from 3d photogrammetry. Heritage 5, 3260–3279 (2022).

Hatır, M. E. Determining the weathering classification of stone cultural heritage via the analytic hierarchy process and fuzzy inference system. J. Cult. Herit. 44, 120–134 (2020).

Angjeliu, G., Coronelli, D. & Cardani, G. Development of the simulation model for Digital Twin applications in historical masonry buildings: The integration between numerical and experimental reality. Comput. Struct. 238, 106282 (2020).

Karatzas, S., Lazari, V., Fouseki, K., Pracchi, V. N. & Balaskas, E. Digital twins-enabled heritage buildings management through social dynamics. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-08-2023-0136 (2024).

Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 11, 321–324 (2010).

Müller, M., Heidelberger, B., Hennix, M. & Ratcliff, J. Position based dynamics. J. Vis. Commun. Image Repr. 18, 109–118 (2007).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.T. designed the research methodology, conducted handicraft experiments, developed the core programming framework, and drafted the initial manuscript. X.H. created data visualization graphs, conducted data analysis/validation, critically reviewed the work, and edited the manuscript for academic rigor. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tao, C., Hong, X. A three-dimensional visualization model for intangible heritage of tie-dye handicrafts. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 648 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02223-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02223-7