Abstract

Based on the Web of Science literature (2004-2024), this review synthesizes integrated applications of solar, geothermal, wind, and other renewables in architectural heritage. It proposes principles centered on authenticity and assesses the potential of renewables for improving energy efficiency, carbon reduction, and environmental comfort, while identifying emerging trends in technological innovation, composite materials, and digital management to guide international research and support the sustainable development of architectural heritage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Architectural heritage encompasses monuments1, historical buildings2, and traditional structures of cultural importance that have yet to be formally recognized. Fabbri3 categorized historical buildings into three types: monuments and buildings with exceptional architectural value; structures built before established historical milestones (i.e., historical thresholds); and buildings that exhibit unique construction and technological systems. The concept of architectural heritage has evolved continuously with the gradual development of cultural heritage preservation frameworks. Today, it encompasses both the heritage entities themselves and their built environments (Table 1). As a key bearer of local cultural identity, architectural heritage serves as both a tangible historical asset and a cultural resource that is vital for societal development4,5. Europe, as the birthplace of architectural heritage studies, has exerted considerable international influence on both preservation theory and technical research. The 1931 Athens Charter was the first to explore the principles and methods of architectural heritage preservation, defining it as monumental buildings and their surrounding environments possessing historical, artistic, and scientific value, and emphasizing the historical, artistic, and scientific importance of such heritage. The 1964 Venice Charter further refined these ideas by introducing “authenticity” and “integrity” as fundamental principles of heritage conservation, with a focus on the authenticity of the materials used in architectural heritage. In 1994, the Nara Document on Authenticity expanded the concept of “authenticity,” stressing the importance of understanding the history and importance of heritage, and allowing for restoration and enhancement when necessary. This approach also placed greater emphasis on the cultural spirit embedded within the heritage, offering a more inclusive perspective than the stringent requirements outlined in the Venice Charter. The 2005 Xi’an Declaration extended heritage protection to include environments surrounding architectural heritage, highlighting their vital role in contributing to the uniqueness and importance of such structures. These international heritage conservation documents clarify the definition of architectural heritage, its value assessment, and conservation methodologies, providing both theoretical principles and technical guidelines for protecting architectural heritage.

Based on the shared global challenges of population growth, resource scarcity, environmental pollution, and climate change, scholars worldwide have shifted their research focus toward renewable energy and energy conservation technologies for carbon reduction6,7,8. In this context, the sustainable development of architectural heritage has become increasingly important, necessitating a more comprehensive approach to its preservation and utilization. This includes improving energy efficiency and reducing carbon emissions, which are critical environmental considerations9,10,11. The rapid advancement of renewable energy technologies has provided key technical support for achieving synergy between the conservation and energy efficiency of architectural heritage12.

Supporting the sustainable development of architectural heritage under the principle of authenticity while simultaneously achieving carbon neutrality, as well as integrating both heritage preservation and energy-efficient retrofitting13,14,15, has become major issues in research. Some scholars have employed measures such as building envelope insulation16, cooling materials, and window renovations to improve the energy efficiency of architectural heritage structures. For example, Ardente17 discussed renovation strategies for European buildings, including the thermal insulation of building envelopes, the upgrade to high-efficiency windows, and the utilization of advanced lighting components. However, these energy retrofit technologies may cause irreversible damage to the structure of heritage, along with its environment and value. Karimi et al.18 analyzed the significance of architectural heritage in energy conservation and carbon reduction and developed a framework for assessing the feasibility of integrating renewable energy technologies into architectural heritage. Their work underscores the importance of safeguarding architectural heritage while advancing energy efficiency goals. Moschella et al.19 suggested the installation of solar energy systems at specific locations of architectural heritage sites, such as windowless and secondary façades. However, this approach may compromise the aesthetic integrity of heritage buildings. A research team led by Lucchi20 modeled selected photovoltaic (PV) systems for architectural heritage, integrating them into the workflows of Heritage Building Information Modeling (HBIM), thereby expanding the application pathways of renewable energy technologies in conjunction with digitalization. Cavagnoli21 considered the preservation characteristics of architectural heritage and implemented geothermal systems within heritage buildings to improve the energy efficiency. Shayegani et al.22 utilized wind-driven ventilation systems, integrating wind catchers, earth tubes, and solar-powered ventilation systems, thereby enhancing the thermal comfort in architectural heritage. Regarding Chohan23, wind catchers were positioned on the exterior of the heritage building to maximize the effectiveness of natural ventilation; however, this design overlooked the need for coordination with the surrounding heritage environment. Vita’s24 adaptive reuse approach, which focused on enhancing the internal comfort of heritage environments, highlights the fact that adaptive interventions may ensure full reversibility while respecting and preserving historical and architectural values.

In summary, (1) There has been substantial research on energy-efficient technologies for architectural heritage25,26, with considerable focus on solar27 and wind energy28. However, research on the technological integration of other renewable energy sources, such as geothermal and biomass energy, remains relatively limited. (2) Studies on the integration of renewable energy technologies into architectural heritage are scattered, predominantly analyzing the application of individual renewable energy technologies, while lacking a comprehensive, multidisciplinary framework that provides guidance for the development of cutting-edge technologies. (3) There is a notable lack of guidelines necessary for the protective and utilitarian integration of renewable energy into architectural heritage, leading to potential damage to both heritage structures and their built environments. Consequently, a comprehensive framework for the integration of renewable energy technologies into architectural heritage is still lacking. Therefore, this study investigates the integrated application of renewable energy technologies within architectural heritage, with the principle of “authenticity” in architectural heritage conservation as the primary criterion. In this context, four key preservation elements—form, environment, materials, and technology—are considered. Specifically, the “principle of harmony” is followed in terms of form, the “principle of minimal intervention” governs the environmental aspect, the “principle of reversibility” is applied to technology, and the “principle of recognizability” guides material use. Ultimately, this research sought to explore pathways for integrating renewable energy technologies into architectural heritage29, utilizing digital and intelligent tools, with the aim of achieving the sustainable development of both heritage itself and its operations3,30,31 (Table 1). The sustainability of architectural heritage refers to the adoption of diverse technologies for its maintenance, under the guiding principle of authenticity, ensuring its correct preservation and utilization, thus revitalizing the heritage and enabling its regenerative development. The sustainability of heritage operations, on the other hand, addresses global carbon neutrality goals. It aims to enhance the carbon reduction potential of architectural heritage sites during their functional use by relying on integrated renewable energy technologies to achieve zero-carbon, green, and ecological outcomes. The primary objectives of this study were as follows: (1)To analyze the unique characteristics of architectural heritage preservation and utilization, clarify the guidelines and strategies for integrating renewable energy technologies within architectural heritage, and establish a comprehensive technical framework for such integration. (2)To trace the research trajectory of renewable-energy integration in the field of architectural heritage, synthesizing the hot topics and challenges surrounding solar, geothermal, wind, and other renewable energy technologies in this domain. (3)To present the major trends and future challenges of renewable-energy integration into architectural heritage within the context of the digital, intelligent, and low-carbon era.

Finally, guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses methodology, this study systematically collected cutting-edge international research and findings. Using the bibliometric analysis tools CiteSpace and VOSviewer, the collected literature was subjected to visualized quantitative analysis. This approach aimed to identify research hotspots and emerging trends in the integration of renewable energy technologies into architectural heritage, providing a robust theoretical and technical foundation for this study. The research framework is as follows: The methods section integrates the findings of cutting-edge international research, and presents a detailed data analysis and interpretation, focusing on key aspects such as research theme networks, geographical distribution, institutions and publications, authors, and journal citations. The results section explores research hotspots related to the integration of solar, geothermal, wind, and other renewable energy sources in architectural heritage, based on which a framework for the engineering and technological applications of renewable energy in architectural heritage is proposed. This section elaborates on the multidimensional integration of technologies within the heritage context. Furthermore, we investigate the future trends and strategic recommendations for zero-carbon, green, and smart architectural heritage, compiling an adaptive analysis table for renewable energy technologies in architectural heritage. This section also identifies sustainable pathways for integrating renewable energy into heritage buildings. Finally, the discussion section presents conclusions, offering strategies and challenges for the future integration of renewable energy technologies into architectural heritage.

Methods

Data statistics

Data source

This study relied on the Web of Science (WOS) database to systematically retrieve global research on energy consumption, energy-saving technologies, and carbon reduction outcomes in the field of architectural heritage, with particular focus on the integration of renewable energy technologies. Using CiteSpace and VOSviewer, the relevant literature was analyzed to generate knowledge maps that clarify international research hotspots, key issues, and emerging trends. CiteSpace, with its powerful time-series analysis and co-occurrence clustering capabilities, identified the main thematic networks and major advancements in the integration of renewable energy technologies into architectural heritage. In contrast, VOSviewer provided a visual co-occurrence network analysis that revealed the intrinsic relationships between research themes and the distribution of knowledge structures. The complementary strengths of both tools enabled precise visual analytics and offered empirical support and a scientific methodology for advancing research in this field.

Literature selection

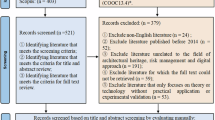

The WOS database was searched for research on the integration of renewable energy technologies into architectural heritage (Fig. 1). The search criteria were set to the “WOS Core Collection,” with the search field designated as “ALL Fields” and the Boolean operator “AND” applied to expand the scope of the search, ensuring comprehensive coverage of key terms. The focus was on “built heritage,” “vernacular heritage,” “vernacular buildings,” “heritage buildings,” “historic buildings,” “traditional building,” “Listed building,” and “architectural monument,” with particular emphasis placed on studies related to the application of renewable energy technologies, including research directions such as “energy utilization,” “carbon reduction effects,” “ecological impact,” and “intelligent integration.” In addition, special attention was paid to research objectives concerning “zero-carbon architectural heritage,” “green architectural heritage,” and “smart architectural heritage.” The selected research domains included “engineering,” “architecture,” and “energy fuels,” with the article type specified as “Article.” Irrelevant or loosely related literature was excluded, followed by a secondary manual screening performed to enhance the relevance of the database results and ensure data accuracy and reliability. By December 2024, 721 relevant studies were identified and selected for bibliometric analysis.

Theme Network

Annual-publication-volume analysis (Fig. 2) revealed that, since 2004, the number of studies on the integration of renewable energy technologies into architectural heritage has increased steadily, with a notably significant exponential trend. Meanwhile, The number of publications increased sharply after 2016 and again after 2022. Time-zone mapping analysis (Fig. 3) indicated that, in 2005, research on renewable energy applications in architectural heritage was centered on the materials and forms of vernacular architecture. This suggests that, as early as 19 years ago, adaptive reuse studies on architectural heritage had already yielded relevant findings. From 2013 onwards, the research focus gradually shifted towards the development of various building materials32, such as lime mortars33,34,35,36 and phase-change materials37, aimed at enhancing the energy efficiency of architectural heritage and promoting its sustainable development. Since 2012, academic studies have increasingly focused on the “energy efficiency” of architectural heritage, with centrality reaching 0.09. Additionally, concepts such as “performance,” “thermal comfort,” and “design” were highlighted (Fig. 4), indicating that the construction of digital models, as well as energy efficiency improvements, are key research hotspots. After 2017, the field of architectural heritage research placed greater emphasis on renewable energy technologies such as building microclimate, solar38, geothermal, and wind power, with particular focus on adaptive reuse and integration39. Advancements in information technology, specifically simulations40,41, digital twins42, and artificial intelligence (AI)43, have provided crucial support for research (Fig. 5).

The application of emerging technologies such as 3D modeling44,45, numerical analysis46, and smart predictions47 has provided key technical support for current research on material development48, energy efficiency utilization12, adaptive reuse14,30,49, energy conservation6,50, and comfort enhancement51 in architectural heritage. These developments have broadened the scope of research and enhanced its quality. A keyword trend mutation graph (Fig. 6) indicated that historical building and energy saving in architectural heritage have attracted interest over time, while the number of recent studies on the optimization51, Energy refurbishment, and sustainable development52,53 of architectural heritage continues to rise. It is foreseeable that interdisciplinary integration will certainly become a focal point of future research, with focus on the development of reversible technologies for architectural heritage. Ensuring the adaptive integration of renewable energy without damaging the integrity of a heritage site will be key to achieving a balance between preserving heritage value and promoting sustainable development10,54.

Research distribution

Geographical analysis

According to a country distribution map (Fig. 7), research on the integration of renewable energy technologies in architectural heritage is predominantly centered on the Eurasian continent, with scattered contributions from the Americas, Africa, and Oceania. With its abundant architectural heritage resources and rapidly advancing scientific and technological capabilities, Italy has emerged as the global leader in terms of the volume of research related to renewable energy technologies for architectural heritage (Fig. 8); research in this field began in 2011, with 192 publications and a centrality of 0.61. China closely followed, with 141 publications and a centrality of 0.28, Overall, European countries such as Italy and Spain, which are the birthplaces of architectural heritage research and renewable energy, have higher research enthusiasm and influence in the field of integrating renewable energy into architectural heritage compared to countries in Asia, America, Africa, and Oceania. In recent years, the research enthusiasm in Asia has been continuously increasing. Among them, China leads in terms of academic output scale, but Italy still maintains its global highest influence by virtue of its standard setting and technology transformation.

Institutional analysis

An institutional-relationship knowledge map (Fig. 9) revealed that the leading research institutions in the field of renewable energy technology integration in architectural heritage include Southeast University of China, Polytechnic University of Milan,Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Egyptian Knowledge Bank, and University of Sevilla. Since 2011, Southeast University of China has successively conducted research in the field of renewable energy technology application for architectural heritage, with rich results. There have been 51 related articles published, ranking first. Polytechnic University of Milan followed closely with 27 academic articles, ranking second. Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche published 23 articles, ranking third. The Egyptian Knowledge Bank published 21 articles; although it ranked fourth, its research center nature ranked second, at 0.1. Overall, institutions in China and Italy have contributed considerably, producing a wealth of high-quality research that has played a critical role in advancing the field. However, the centralities of most institutions are generally lower than 0.1, indicating a lack of strong inter-institutional collaboration. In addition, there is an urgent need to establish cross-institutional research alliances, connect global collaborative networks, and optimize cooperation pathways to overcome barriers to technology transfer and advance the field.

Co-citation analysis

Literature analysis

A minimum citation threshold of five citations per paper was set, resulting in the identification of 58 key citation nodes. Additionally, the minimum number of citations per literature node was set to five. Based on the similarities in research directions among the cited studies, the analysis generated five clusters. These clusters were defined by the number of literature nodes they contained, with Cluster 1 having the highest number of nodes (16), followed by Cluster 2, with 13 nodes, and so on. Cluster 5 contained the fewest nodes (8). The frequency of citations for each paper within a cluster was represented by the prominence of the node, with more prominent nodes indicating a higher citation frequency, indicating the importance of these papers in their respective research areas. The links between co-cited papers reflect their interconnections, with stronger linkages indicating closer research relationships and more similar directions. As shown in Fig. 10, Paper[49] and paper55 belonged to Cluster 2 and Cluster 4, where Paper[49], cited 50 times and having a link strength of 281, evaluated energy retrofitting in architectural heritage and offered feasible suggestions for primary and secondary standards, thereby guiding future research in this area. Paper55, cited 49 times and having a link strength of 266, provided a comprehensive review of energy efficiency and thermal comfort in architectural heritage, summarizing methods and technologies while proposing new research avenues and significant paths. Both papers, as review articles, were closely related in terms of research focus, making them highly co-cited and foundational in the field. An analysis of the citation counts and link strengths revealed that the primary research focus was energy simulation experiments for architectural heritage and innovations in renewable energy integration technologies. These studies emphasize the application of multi-omics techniques for exploring the adaptive energy retrofitting of architectural heritage, aiming to achieve energy sustainability while preserving and utilizing heritage buildings.

Author analysis

A minimum citation threshold of 10 was established, resulting in the identification of 52 author nodes (Fig. 11). Among them, the top 5 in terms of citation frequency are respectively Lucchi from the Renewable Energy Research Institute of Eurac Research Center in Italy, with 150 citations and a link strength of 851, ranking first and having the highest research impact; From Federico II University in Naples, Italy, Ascione, F, with 107 citations and a link strength of 882, ranked second; From the National Committee for Atmospheric Sciences and Climate Research of Italy, camuffo, d, with 64 citations and a link strength of 290, ranked third; The European Commission, cited 58; and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), cited 57. These scholars have made remarkable contributions to the theoretical, methodological, and technical foundations of renewable-energy integration into architectural heritage, placing them among the most influential researchers in this field. The analysis revealed that scholars from regions rich in architectural heritage resources, such as Italy, China, and Spain, dominate the field. Italy, as a leading hub for architectural heritage preservation research, has cultivated numerous outstanding experts, whose work continue to have considerable influence within the domain.

Journal analysis

A minimum citation threshold of 15 was established, which resulted in the identification of 70 journal nodes (Fig. 12). The international journal Energy and Buildings ranked first, with an impact factor of 6.6 and 2,089 citations, along with a link strength of 47,514. This journal is distinguished by its comprehensive approach to the application of engineering technologies, focusing on cutting-edge advancements in building energy use, and publishes articles aimed at reducing building energy demands and improving indoor environmental quality. The second-ranking journal was Building and Environment, with an impact factor of 7.1, 1,044 citations, and a link strength of 27,735. This journal primarily covers frontier research on building environments and performance and requires rigorous validation through measurements and analysis. It is considered a high-quality journal in the field and has substantial influence. The third-ranking journal, Sustainability, had an impact factor of 3.3, with 645 citations and a link strength of 18,674. It focuses on a wide range of topics related to technological, environmental, cultural, economic, and social sustainability, making it an important journal in this domain. The analysis revealed that high-impact journals in this field predominantly focus on energy technologies, optimization and renovation, green materials, indoor environments, and the protection and utilization of architectural heritage. The articles published in these journals exhibit strong technical depth and interconnectivity, providing a vital platform for exchange and advancing research in the field. These core journals, combining high quality and influence, provide important directions for future studies. Thus, it is evident that research on the integration of coupled energy technologies for architectural heritage will remain a key focus in coming years.

Results

Shifts in themes and emerging issues

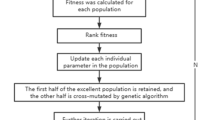

Current research on the integration of renewable energy technologies within architectural heritage remains constrained by a lack of necessary protective utilization guidelines. This gap often leads to irreversible damage to heritage buildings and their surrounding environments. Additionally, existing approaches to the non-destructive or minimally invasive integration of technologies are somewhat limited, with a notable absence of broad interdisciplinary perspectives. However, the advent of technologies such as HBIM for precise heritage building modeling20, coupled with AI algorithms for optimizing the layout and operational strategies of renewable energy systems56, presents a considerable opportunity. Moreover, the application of metaverse technologies57,58 for virtual simulations and evaluations can facilitate the efficient integration of renewable energy technologies without compromising heritage structures or their environments. This trend marks a major direction for future research in the field and is becoming a hot topic of investigation52,59. In light of these developments, this study proposes an engineering application framework for integrating renewable energy within architectural heritage (Fig. 13). The framework consists of three stages: data collection, equipment installation, and integrated application. During the data collection phase, heritage building databases are constructed using methods such as historical document review and laser scanning60,61,62, which serve as a foundation for energy and environmental analyses. Techniques such as computational fluid dynamics63, wind tunnel testing64, and numerical analysis46 have been employed to assess the energy suitability of heritage structures. In the equipment installation phase, energy devices are selected based on an environmental analysis of the building’s energy requirements. Studies have focused primarily on installing solar PV panels to harness solar energy65,66, ground-source heat pumps (GSHPs)67 to capture geothermal energy, and wind turbines for wind energy applications68,69. Finally, in the integrated application phase, technologies such as HBIM43,50, digital twins70,71, and AI72 are used to develop cloud platforms for simulating the energy use of a heritage structure73, regulating its operational energy consumption74, and monitoring structural issues. This approach facilitates multi-energy complementarity in the energy integration of architectural heritage.

Solar energy technology integration into architectural heritage

Studies have explored the intersection of architectural heritage with solar energy technologies18, low-carbon transitions, and near-zero energy consumption. The primary focus of solar energy applications in architectural heritage is PV66 and solar thermal (ST) systems75. On the one hand, PV systems can address the challenges associated with lighting systems, specifically the uneven natural light distribution, poor visual comfort, and excessive energy consumption. On the other hand, integrating PV systems with ST technologies to convert solar energy into electrical and thermal energy can significantly reduce the reliance of architectural heritage on conventional energy sources65. This integration not only reduces lighting energy consumption but also mitigates heating issues, promoting the sustainable use of energy53,76. Research has indicated that proactive adaptive carbon reduction and energy-saving retrofits for architectural heritage can efficiently integrate solar energy technologies into heritage spaces75, making this a key focus in the field. The major research directions in this area encompass both the invasive77 and non-invasive integration78 of solar energy technologies into architectural heritage. This focus reflects ongoing efforts to optimize the application of renewable energy systems while preserving the integrity and authenticity of heritage buildings.

The integration of invasive solar energy technologies into architectural heritage refers to the deep incorporation of solar energy systems with the structural elements of heritage buildings. This includes technologies such as building-integrated PV (BIPV)79 and building-integrated ST (BIST) systems80. BIPV systems, for example, encompass PV solar roof tiles, PV façades, and PV canopies. Unlike the simple attachment of building-attached PVs (BAPV), BIPV systems integrate solar PV systems directly into the architectural fabric, serving both as functional building components and as self-sustaining energy sources. Invasive solar technologies, by integrating PV or ST components into heritage buildings, can effectively blend with the heritage environment81, aligning with the principle of “form harmony” in renewable-energy integration guidelines for architectural heritage. As an integral part of the building structure, these systems perform three key functions: enclosure, energy conservation, and monitoring. They meet the functional needs of heritage buildings while facilitating energy conversion and utilization. However, the invasive nature of these technologies, which requires the integration of PV or ST components, inverters, controllers, and energy storage devices82,83,84, inevitably results in irreversible damage to the heritage structure. Therefore, these invasive systems are currently unsuitable for buildings with a high protection status, such as national treasures. Such systems are recommended only for use in more common historical buildings and traditional residential heritage sites. In cases where national treasure-level heritage buildings are structurally unstable or have suffered considerable collapse, however, the integration of protective support structures with invasive solar technologies may offer a solution for technical restoration. In this context, the development of tiered standards for the installation of solar technology systems becomes an important issue for future research. Additionally, BIPV systems often rely on modern materials. Ensuring that these new materials are independent of, and do not interfere with, a heritage building’s original material system is essential for maintaining the “recognizability” principle of materials. Following the “minimal intervention” principle, the field is increasingly concerned with employing “minimally invasive” techniques that preserve the integrity of the built environment while allowing for the installation of solar technology. For example, using colored glass, color-changing PV glass, and other colored PV components83,85, which mimic the materiality of the heritage structure while maintaining distinction from the original materials, helps to achieve material “recognizability.” Furthermore, using thin-film PV components and micro-inverters86, controllers, and storage devices allows for minimal intervention in the structure while restoring the building’s original appearance, adhering to the “minimal intervention” principle and ensuring both structural enclosure and ecological energy efficiency.

The non-intrusive integration of solar technology into architectural heritage refers to the attachment of solar energy systems to supporting structures78, which avoids structural alterations to the original building. A key example is with BAPV systems84, formed by independently installing PV modules on the surface of a building’s envelope, using auxiliary components such as clips, rail supports, and flexible substrates. These PV systems function as supplementary energy-generation equipment, rather than contributing to the structural or enclosing functions of the building, making them easy to replace or maintain. Moreover, upon dismantling, they do not cause considerable damage to the building, in accordance with the “reversibility” principle outlined in the renewable-energy integration guidelines for architectural heritage. Non-intrusive solar technology is widely adopted in the field of architectural heritage conservation because it is suitable for high-level protected buildings. However, care must be taken during removal so as to avoid damaging the original structure. Presently, the predominant PV technologies used in architectural heritage are crystalline silicon, copper indium selenide, and cadmium telluride photovoltaics84, which utilize crystalline silicon or thin-film semiconductors as materials. These modules are coated with anti-reflective or anti-glare films, mounted on adaptive tracking supports87, and connected using magnetic connections. This technology meets the “recognizability” principle of materials in architectural heritage, ensuring the independence of a system from the heritage building itself. However, the continuous placement of PV modules can disrupt the original aesthetic of heritage structures. Moreover, the high reflectivity of metallic surfaces creates a visual contrast with traditional materials, which complicates adherence to the “harmony” principle of form. A critical challenge in the application of non-intrusive solar technologies is the employment of PV components, support structures, and connection parts that mimic the form, color, and texture of heritage buildings, possibly by integrating traditional craftsmanship methods to achieve form coherence. Moreover, the equipment used for non-intrusive solar systems occupies a considerable amount of space in the heritage environment, potentially jeopardizing the historical continuity and integrity of the space. This presents a challenge to the “minimal intervention” principle. Therefore, an important consideration for the future integration of BAPV systems in architectural heritage is the development of lightweight components that can be discretely installed on the non-historic parts of a building’s envelope.

Integration of geothermal energy technology in architectural heritage

Geothermal energy, which is derived from the heat produced by Earth’s molten core and the decay of radioactive materials, accounts for most of the energy harnessed from beneath Earth’s surface. This energy can be utilized for both geothermal power generation and temperature regulation within buildings88. Traditional geothermal technologies include hydrothermal systems and shallow-GSHP technologies89. In response to the growing demand for energy-efficient solutions in resource-constrained environments, advancements in geothermal energy have focused on enhancing circulation, drilling techniques, and heat-exchange technologies. These innovations have enabled the exploitation of geothermal resources beyond shallow layers, progressing toward deeper subsurface energy extraction, thus expanding the potential for geothermal applications in architectural heritage. Existing studies have indicated that the adoption of geothermal energy technology in architectural heritage is rapidly evolving towards greater efficiency, intelligence, and sustainability. Research in this field is primarily focused on two aspects: the integration of GSHP technology within architectural heritage, and the integration of geothermal energy monitoring and management systems.

GSHP technologies are highly efficient heating and cooling systems that uses underground soil, groundwater, or surface water as low-temperature heat sources. These systems primarily consist of an outdoor heat exchange unit, the GSHP main unit, and end-use systems within the building, such as fan coil units, radiators, or underfloor heating systems90. Heat pumps, as energy-efficient devices59,67, effectively convert geothermal energy, regulate indoor temperature in architectural heritage, and enhance thermal comfort21,67. Currently, GSHP technology can optimize pipe connections through series configurations and modular designs, which streamline installation and decommissioning processes. By pre-designing dismantling paths for the GSHP system components, the impact on the heritage structure is minimized, aligning with the technical “reversibility” principle in renewable-energy integration guidelines for architectural heritage. Additionally, cutting-edge equipment such as horizontal ground heat exchangers91, single-effect ammonia/lithium nitrate heat-pump transformers92, and high-density polyethylene geothermal exchangers48 enable cost-effective and efficient geothermal energy use in heritage buildings. These advanced materials differ considerably from original materials in terms of form, color, and texture, ensuring adherence to the “material recognizability” principle. However, the need for surface drilling to access geothermal energy, along with the installation of buried pipes and heat exchangers, can remarkably disrupt the heritage environment, thus failing to meet the “minimal intervention” principle. As a result, GSHP technology is not suitable for buildings with high protection levels, such as monuments and historic buildings, but is more appropriate for traditional dwellings in areas with abundant geothermal resources and lower conservation requirements. Therefore, the future challenge lies in developing minimally invasive installation techniques for geothermal energy systems in architectural heritage. Furthermore, it is crucial to ensure that the size of a GSHP system is minimized through modular design, landscape integration, and spatial concealment strategies, which would reduce the spatial occupation and impact. The design should also aim for achieving a cohesive aesthetic in the heat exchanger, support structures, and other system components to satisfy the “form harmony” principle. Achieving a balance between the volume and layout of geothermal equipment is pivotal for future applications of GSHP technology in architectural heritage.

Geothermal energy monitoring and management technologies represent integrated systems that combine geological exploration, sensor technologies, data analysis, and intelligent decision-making. Through Internet of Things (IoT) sensing, smart analytics, and remote control, such systems provide dynamic monitoring and optimization throughout the process of geothermal resource extraction, transmission, and utilization, facilitating the intelligent management of geothermal resources in architectural heritage93. In the context of architectural heritage, geothermal energy monitoring employs infrared thermography77,94 and remote-sensing technologies to assess microclimates95, alongside with the use of ground-based laser scanning and thermal imaging data to create digital thermal models96 of heritage buildings. This integrated approach helps prevent structural damage and reduces environmental energy consumption, aligning with the “minimal intervention” principle of renewable-energy integration guidelines for architectural heritage. The digital and automated non-invasive integration of geothermal energy is a highly recommended method in the field of architectural heritage conservation, making it applicable to heritage buildings at all protection levels, including monuments, historic buildings, and traditional dwellings. Geothermal energy monitoring technologies include Distributed Acoustic Sensing97, Fiber-optic Humidity and Temperature Coaxial Cable98, Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar99, and distributed energy monitoring systems. These systems deploy radar and sensor devices equipped with identification and numbering systems for data analysis and intelligent decision-making, thus meeting the “material recognizability” principle for heritage buildings. However, the deployment of radar and sensors at key nodes of a building may create visual noise, potentially leading to damage to the building’s aesthetic. Additionally, seamlessly installing cables in the architectural environment is often difficult. Therefore, a key challenge for future research lies in the development of radar systems and humidity/temperature sensors that can be discreetly installed within the existing voids of architectural heritage, using concealed cable systems to ensure form “coherence” and minimize disruption to the building’s appearance. Furthermore, the current physical attachment methods for monitoring cables and sensors may cause irreversible damage to the structure of buildings, such as peeling walls. However, the development of lightweight monitoring systems and easy-to-remove components could satisfy the “reversibility” principle in renewable energy technology. Consequently, independent cable systems and lightweight sensors hold remarkable potential for the adaptive integration of geothermal energy into architectural heritage.

Integration of wind energy technology in architectural heritage

The integration of wind energy technology into architectural heritage is becoming a critical approach for achieving green building objectives and reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions. Existing research has focused on structural wind engineering22 for heritage buildings, the optimization of wind energy recovery devices100, and both indoor and outdoor natural ventilation63. Studies have indicated that the application of wind energy technologies in the context of architectural heritage primarily centers on three key areas: the integration of wind energy recovery devices, passive ventilation technology, and structural wind-proofing techniques.

Wind energy recovery technologies, such as wind turbines101,102,103 and high-altitude wind power generation systems104,105,106,107, capture, convert, and utilize various forms of wind energy from the environment through wind power generators, energy capture devices, and energy storage and regulation systems. These technologies transform wind energy into electrical and mechanical power, thereby enhancing the energy efficiency of architectural heritage sites and improving their ventilation environments. Wind turbines in energy recovery systems use recyclable wind turbine blades, thus minimizing white pollution, while modular detachable supports and prestressed assembly towers are designed with removable pathways to prevent permanent damage to the structures of heritage buildings. Furthermore, current high-altitude wind power systems, using tethered kite technology108 and tethered aircraft technology108,109, capture wind energy at higher altitudes and transmit it to the ground via cables. These systems are simple and highly recyclable, adhering to the “reversibility” principle in the integration of renewable energy technologies into architectural heritage. To further integrate with architectural heritage, wind turbine casings or custom blades and connection components are made from materials similar to those used in heritage buildings, with each component marked using a modern material identification system for digital management and dynamic simulation47. This enables remote control of wind energy recovery devices through automated systems, aligning with the “recognizability” principle for materials in architectural heritage. However, the geometric form and material composition of modern components such as small-to-medium-sized wind turbines102 and supporting towers significantly differ from those of traditional materials, making it challenging to meet the “form harmony” principle. To address this, unifying the texture and material of generator units and supporting towers, as well as minimizing visual interference, are crucial for achieving form harmony in the integration of wind energy recovery systems into architectural heritage. Additionally, the installation of wind turbine towers and cable systems often requires substantial space within the heritage environment, potentially disrupting the architectural layout and altering the original spatial structure, thereby conflicting with the “minimal intervention” principle. Consequently, such systems are primarily suitable for historical buildings, traditional dwellings, or heritage sites with lower conservation classifications. In contrast, high-altitude wind power systems—offering minimal spatial intervention, low environmental impact, high recognizability, and reversibility—are poised to become the focal point of future research on the integration of wind energy recovery devices into architectural heritage.

Passive ventilation relies on wind pressure and thermal buoyancy to drive air circulation, facilitating natural airflow without requiring mechanical systems, thereby reducing carbon emissions and offering considerable economic and energy-saving advantages110. As core components in passive ventilation systems, wind caps and air collectors are responsible for capturing, directing, and regulating airflow. These devices can enhance the stability and efficiency of passive ventilation in architectural heritage sites by optimizing both indoor and outdoor airflow exchanges. Studies on the integration of passive ventilation technology into architectural heritage employed methods such as wind tunnel testing and numerical simulations to assess wind environments and focused on the scientific integration of wind caps and air collectors to improve ventilation performance. Additionally, passive ventilation in architectural heritage sites can be achieved by strategically placing windows and doors to create a natural cross-ventilation effect, or by using skylights and courtyards to promote air convection. Since this approach does not require active mechanical systems, it preserves the original architectural aesthetics, thereby adhering to the “form harmony” principle in the integration of renewable energy technologies in architectural heritage. However, the installation of wind caps and air collectors on the roofs or external walls of heritage buildings can disrupt form harmony, rendering it suitable only for traditional dwellings. Furthermore, wind caps and air collectors are often constructed using modern materials, such as metals and composites, to enhance durability, thermal insulation, and corrosion resistance, which aligns with the “recognizability” principle for materials in architectural heritage. Nevertheless, structural modifications111 for creating ventilation openings, intended to induce the wind tunnel effect and facilitate natural airflow, could irreversibly affect the heritage structure, violating the “reversibility” principle. Consequently, passive ventilation technology is unsuitable for buildings with higher protection classifications and is primarily applicable to traditional dwellings seeking improved energy efficiency. Moreover, modifications to skylights on roofs and courtyards for ventilation purposes can disrupt the original environment, making it difficult to adhere to the “minimal intervention” principle. Therefore, careful consideration of the selection and spatial arrangement of passive ventilation systems is essential for minimizing environmental disruption and achieving optimal integration.

Structural wind resistance technology in architectural heritage sites can be used to assess the impact of regional wind environments on heritage buildings112,113. Using methods such as wind tunnel testing64,114, numerical simulations115, and digital visualization116, and leveraging software-based analysis117,118,119, this technology identifies wind load and energy control pathways for heritage buildings120,121, thereby reducing the adverse effects of wind on these structures122. This research provides guidance for technical modifications to architectural heritage, aimed at improving energy efficiency and reducing emissions. For high-rise or wind-sensitive heritage buildings, structural interventions can either integrate wind resistance measures to harness wind energy or employ non-intrusive wind resistance systems, such as protective wind barriers, to convert wind energy and improve the microclimate surrounding the building. Intrusive structural wind resistance techniques, such as intelligent dynamic façades, smart dampers, and advanced flow-directing devices, alter airflow patterns to reduce external wind pressure. These solutions, along with self-healing biomimetic coatings, can align with the original forms and materials of the heritage building, thus adhering to both the “form harmony” and “material recognizability” principles. However, structural modifications for wind resistance may damage the original heritage structure, violating the “reversibility” principle of technological interventions. In contrast, non-intrusive wind resistance technologies, which involve modifying a building’s envelope, structure, and spatial organization, can cause irreversible damage to buildings and their environments and are, therefore, unsuitable for highly protected heritage buildings. However, they are more applicable to historic buildings or traditional dwellings with a lower protection status. In this context, defining classification standards for intrusive structural wind resistance systems for architectural heritage sites will be a key issue for future research. Non-intrusive wind resistance technologies, on the other hand, can improve the environment around heritage buildings by modifying the terrain, planting vegetation, or creating artificial barriers, thereby altering the airflow patterns around the structures. Additionally, integrating smart monitoring technologies123 can reduce the wind load on a heritage building, fulfilling the “form harmony” principle and the “material recognizability” principle in renewable-energy integration. For example, Li et al.124 proposed the use of non-invasive methods, such as tree planting, to reduce wind pressure and load on architectural heritage sites while simultaneously enhancing a building’s structural wind resistance and environmental adaptability. However, these non-intrusive modifications still impact the surrounding environment and do not align with the “minimal intervention” and “reversibility” principles. Despite their limited impact, they are an optimal solution for improving wind resistance in all levels of protected heritage buildings, historic structures, and traditional dwellings.

Integrated multi-technology applications of renewable energy in architectural heritage

In the context of carbon reduction and energy efficiency in architectural heritage, the integration of renewable energy technologies is progressively emerging as a key pathway for achieving energy-saving and emission reduction goals125. In addition to mainstream renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, other renewable energy technologies, including biomass energy126 and marine energy, are increasingly becoming focal points of research within this field. Among these, marine energy, such as tidal, wave, and ocean current energy, harnesses the ocean’s power to convert energy. Although the application of marine energy in architectural heritage remains limited, it holds considerable potential for development, particularly in coastal heritage buildings. Existing research has indicated that renewable-energy integration into architectural heritage is evolving toward a more diversified and comprehensive approach. The multidimensional integration of renewable energy technologies within architectural heritage sites provides crucial technical support for the construction of green, smart, and zero-carbon heritage buildings (Fig. 14). Prominent research trends in this field include the integration of biomass energy technologies, application of “photovoltaic–energy-storage–direct–flexible” (PEDF) systems, and integration of carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies. Biomass energy, which is the solar energy stored in the form of chemical energy within plants, animals, and microorganisms, can be harnessed through technological pathways such as direct combustion, biochemical conversion, and thermochemical conversion. These processes provide energy for cooking and heating127. Biomass power plants can supplement electricity supply, while biomass-derived materials can be utilized for the restoration and reinforcement of architectural heritage. Owing to its unique carbon cycle characteristics, biomass energy is the only renewable zero-carbon energy source, offering considerable potential for low-carbon transformation within architectural heritage structures. The appearance of biomass boilers128 and biomass gasification systems129 can be customized to align them with the aesthetic of architectural heritage sites, adhering to the principle of “form harmony.” These systems are also designed with detachable mounting structures that can be fixed to the auxiliary spaces or external environments of heritage buildings, thus preserving the original state of the architectural heritage and aligning with the “reversibility” principle of technology.

Furthermore, the standardized and modular nature of biomass energy equipment makes them easily identifiable and distinct from the original materials of the heritage building, thus meeting the “material recognizability” criterion. This makes biomass energy applicable to heritage buildings with high preservation value, including historic monuments, buildings, and traditional dwellings. Biomass energy technology has evolved from simple combustion to efficient conversion and high-value utilization, positioning it as one of the most promising renewable energy technologies for future low-carbon energy-efficient applications in architectural heritage. However, harmful gases produced during direct biomass combustion can contribute to environmental pollution, and the use of large-scale modular biomass boilers for heating often requires installation outside buildings, occupying considerable space within the heritage environment. Additionally, the installation of heating pipelines may disturb the heritage environment, making it difficult to satisfy the “minimum intervention” principle for the environment. Therefore, the selection of biomass energy facilities in terms of size and classification is a critical factor influencing their integrated application in architectural heritage.

PEDF technology combines four key components: PV solar energy, distributed energy storage, direct current (DC) distribution, and flexible interaction mechanisms130,131. Through this integrated building energy system, PEDF technology can enhance the electrification level of architectural heritage sites, effectively address issues related to resource consumption and carbon emissions132, improve energy efficiency, and reduce dependency on conventional energy sources, thereby playing a pivotal role in advancing zero-carbon energy solutions in architectural heritage. The envelopes of buildings, particularly the roofs and façades, provide ideal spaces for the installation of PV panels. By integrating BIPVs or supplementary PV systems, these panels efficiently harness solar energy. Battery devices within a distributed energy storage system are typically installed in the interior of heritage buildings. For larger heritage spaces, such as those found in rural settlements, the system can be deployed in a shared configuration, using DC distribution facilities to provide direct power supply and management. Flexible interaction is achieved through machine-learning algorithms that intelligently adjust energy consumption based on user demand, simulating power needs under varying weather conditions, thereby ensuring timely storage and continuous use of electricity. BIPVs align with the form of architectural heritage sites, while small-scale energy storage devices are placed inside heritage buildings, avoiding disruption to the surrounding environment. DC distribution systems simplify the complex wiring of traditional distribution systems by utilizing existing architectural gaps for cable routing, in accordance with the “form harmony” principle. The adaptive brackets and modular battery housing materials of supplementary PV systems exhibit material differentiation from the heritage structure, ensuring adherence to the “material recognizability” principle. Furthermore, supplementary PV system (BAPV) modules are independently installed, relieving the construction of structural or envelope-related duties. The non-invasive installation of sensors within flexible interaction technologies ensures that no damage occurs to a building’s surfaces during disassembly, fulfilling the “reversibility” principle of technology. A distributed energy storage system that employs small-scale storage batteries is installed within the interior spaces of heritage buildings, minimizing the impact on usable space. Flexible energy consumption is controlled via intelligent algorithms, actively adjusting power usage without disturbing the heritage environment, thus adhering to the “minimum environmental intervention” principle. As an integrated energy technology system, the cutting-edge components of PEDF technology are diverse. A key issue for future academic inquiry is the development of classification and selection standards for equipment used in the integrated application of renewable energy within architectural heritage, ensuring compliance with the guidelines for energy integration in heritage buildings.

The adoption of CCUS technology is crucial for achieving carbon neutrality in the building sector133. CCUS technology plays a pivotal role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions by capturing, utilizing, and storing carbon dioxide (CO₂) from industrial emission sources surrounding buildings. In architectural heritage, biological methods, such as the use of green plants, along with physical or chemical techniques, such as the adoption of adsorbent materials, can be employed. Using absorption towers, carbon transport, utilization, and storage facilities, these methods incorporate advanced technologies such as machine learning to facilitate carbon capture and utilization134. CCUS technology, with its underground transport systems and compact capture devices, minimizes visual disturbances in heritage environments, thus adhering to the “form harmony” principle in the guidelines for renewable-energy integration in architectural heritage. Additionally, CO₂ capture reactors, compressors, and monitoring equipment are constructed using modern technology, harmonizing with architectural heritage aesthetics and featuring unique identifiers for material traceability, thereby complying with the “material recognizability” principle. The modular capture technology of CCUS, which utilizes small-scale direct-air-capture systems135, adsorbs CO₂ while discharging clean air. These systems are placed within the ancillary spaces of heritage buildings, ensuring that the installation and disassembly processes do not impact the structural integrity of the heritage site, thereby fulfilling the “reversibility” principle. However, the underground transportation systems for carbon storage require deep surface excavation, which considerably disrupts the heritage environment and fails to meet the “minimum environmental intervention” principle. Therefore, CCUS technology is not suitable for the preservation of high-value heritage buildings, including monuments and historical structures. However, it can be applied to buildings with lower protection levels, such as historical buildings or traditional dwellings. In cases where the industrial CO₂ emissions surrounding heritage buildings are excessive, CCUS technology may serve as a supplementary measure to enhance energy efficiency and reduce emissions. By converting CO₂ into clean building materials for adaptive reuse, it improves the carbon reduction potential of heritage structures and contributes to achieving net-zero carbon emissions136. Although this technology holds great promise for lower-level heritage protection, its high cost and complex processes currently limit its application in architectural heritage.

Cutting-edge progress and future prospects

The integration and application of renewable energy technologies hold substantial research potential for the sustainable development of architectural heritage137,138,139. Existing studies have shown that, on one hand, there is still a need for further exploration of renewable energy types suitable for architectural heritage. For instance, the integration of biomass energy into heritage buildings remains under-researched. On the other hand, a challenge lies in minimizing the destructive impacts of current interventionist technologies on both the heritage structure and its built environment, while simultaneously developing non-invasive energy integration technologies that adhere to authenticity principles. An adaptation analysis of renewable energy technologies within architectural heritage (Table 2) revealed that the integration of renewable energy technologies is still not sufficiently refined, particularly in terms of establishing necessary protective and utilization guidelines. This gap in research may result in irreversible damage to heritage fabrics and their surrounding environments. Future research will focus on addressing these technological challenges to align carbon reduction and energy conservation strategies with the preservation of the intrinsic value of architectural heritage54,140. This will be achieved through a combination of active75 and passive strategies141, proposing pathways for the sustainable integration of renewable energy technologies in architectural heritage (Fig. 15). The ultimate aim is to facilitate the adaptive transformation of architectural heritage towards energy-saving, carbon-reducing, and eco-friendly objectives, leading to the realization of zero-carbon heritage buildings, green heritage architecture, and smart heritage buildings (Fig. 16).

Zero-carbon heritage buildings and innovations in energy engineering

Zero-carbon heritage buildings aim to achieve near-zero annual CO₂ emissions by leveraging efficient energy-saving measures and renewable energy technologies, and even provide energy supplementation, thereby achieving a carbon-negative status. This approach represents a critical pathway toward achieving carbon neutrality. Innovations in energy engineering, through technological advancements and system optimization, enhance the efficiency of renewable-energy utilization, offering systematic strategies for energy storage technologies, energy efficiency optimization, and technical synergies within zero-carbon heritage buildings. These innovations serve as key drivers for the realization of zero-carbon heritage buildings and the enhancement of their operational efficiency. In the future, the innovation, improvement, and development of renewable energy integration technologies will be pivotal in research on zero-carbon heritage buildings. The primary focus will be on developing novel series-connected storage technologies, increasing the efficiency of renewable-energy utilization, and optimizing the coupling of renewable energy with emerging technologies.

Novel series-connected energy storage technologies comprise three primary pathways

electricity storage, thermal storage, and hydrogen storage. These systems consist of storage units, energy conversion devices, and control systems. Known for their high flexibility, safety, and ease of operation, these technologies are crucial for ensuring energy supply and facilitating energy storage in zero-carbon heritage buildings142,143. Series-connected energy storage systems address the “barrel effect” inherent in traditional centralized storage systems, enabling the individual management and optimization of each cluster, thereby remarkably improving the balance of the battery packs and the efficiency of charge and discharge cycles. Furthermore, these systems are modular in design, with smaller cabinet sizes that can be installed within the auxiliary spaces of zero-carbon heritage buildings. Their easy installation and removal do not disrupt the original structure or aesthetics and they adhere to the principles of reversibility and architectural harmony. Additionally, storage batteries and energy conversion devices are labeled and distinguishable from the original materials of heritage buildings, fulfilling the material recognizability principle.

The modularity and compact size of series-connected storage technology144 offer considerable advantages in terms of flexible placement, making it well-suited for zero-carbon heritage buildings with auxiliary spaces, while complying with the minimal-environmental-intervention principle. However, for zero-carbon heritage buildings without such spaces, or those with limited architectural volume, the installation of this technology may require external placement, leading to greater environmental disruption and, thus, failing to meet the minimal-environmental-intervention standard. Moving forward, the trend for novel series-connected energy storage technologies in zero-carbon heritage buildings will focus on lightweighting and integrated management, which will be critical for the future development of these systems.

To enhance the utilization efficiency of renewable energy, current research is primarily focused on the development of tools136,145, technological innovations, digital monitoring systems74,146, and intelligent management techniques50,74. Specifically, studies have aimed to identify high-efficiency energy-saving and carbon reduction technologies to advance digital and automated strategies for renewable energy systems, thereby adhering to the principles of reversibility, material recognizability, and minimal environmental intervention. However, the installation of smart technologies, such as sensors and detectors, in prominent areas of zero-carbon heritage buildings may result in visual disruptions, thereby violating the principle of architectural harmony. Meanwhile, passive energy-saving technologies, such as high-performance insulation materials, energy-efficient windows, and wind catchers23,147,148, along with renewable energy systems, including PV array76,81, geothermal storage, and wind power generation systems, provide essential technical support for achieving zero-carbon buildings. In this regard, considerable breakthroughs continue to emerge in the field of zero-carbon heritage-building energy efficiency149. While the current research landscape predominantly focuses on mainstream energy sources such as solar, geothermal, and wind, there has been relatively limited exploration of other renewable resources such as hydropower, wave energy, and biomass. Future studies should address the lightweighting and applicability of digital monitoring technologies for renewable energy while also exploring the targeted integration of renewable energy systems in zero-carbon heritage buildings with abundant local energy resources. This will improve energy integration methods and enhance the overall energy efficiency of zero-carbon heritage buildings, providing practical solutions with considerable implications for their sustainable development.

Emerging technologies provide vital tools for regulating and controlling renewable-energy utilization in zero-carbon heritage buildings. They serve as the technological backbone for enabling digital and automated management and decision-making in such buildings. In the context of big data, the application of emerging technologies to zero-carbon heritage buildings focuses on modern architectural design137,150, energy-saving100 and carbon reduction strategies, energy storage70, and engineering management42. By integrating renewable energy technologies such as BIPV151, BIST, and ATES systems with advanced tools such as HBIM152, AI72, IoT153, and energy simulation models151, these technologies facilitate intelligent simulations of the impacts of light, wind, and thermal environments on buildings. They also enable the dynamic monitoring of energy acquisition and data usage74,154, offer early disaster warning capabilities, enhancing both indoor and outdoor environmental quality110, and improving human comfort levels51.Meanwhile, these technologies enable the precise coordination of a building’s energy systems, leveraging the complementary advantages of passive energy-saving techniques and active equipment. This integration adheres to the principles of reversibility and material recognizability. However, the installation of such systems may require considerable external space in zero-carbon heritage buildings, leading to considerable visual disparities that disrupt the building’s overall aesthetic and substantially disturb the surrounding environment, thus violating the principles of architectural harmony and minimal environmental intervention. Future advancements in optimizing the coupling of renewable energy with emerging technologies will focus on improving the utilization rate of reversible energy technologies and enhancing the accuracy of digital simulations. By minimizing damage to the structure and appearance of heritage buildings while providing targeted energy facility regulation strategies, this approach will enhance the indoor comfort of zero-carbon heritage buildings. Such developments represent an inevitable trend toward realizing intelligent, zero-carbon heritage buildings.

Green building heritage and ecological composite materials

Green building heritage refers to the preservation of building heritage and its built environment, with an emphasis on sustainable development and environmental protection. It is grounded in green building theory and technologies117,138, aiming to ensure the long-term sustainability of architectural heritage and enhance the comfort of its surrounding environment55. Green building heritage relies primarily on the use of indigenous construction materials to achieve insulation, thermal regulation, and energy efficiency, thus fostering ecofriendly, comfortable, and low-carbon conditions. However, over time, the original materials used in green buildings inevitably degrade, leading to a gradual loss of their energy-saving and comfort-enhancing properties. In this context, ecological composite materials have emerged as key materials for the restoration and energy efficiency of green building heritage. These materials, celebrated for their environmental sustainability, provide a critical means of maintaining and enhancing the performance of heritage buildings. As such, ecological composite materials represent an essential tool for the future conservation and energy optimization of green building heritage.

Novel energy-efficient materials are developed through scientific innovations that significantly enhance energy utilization or reduce energy consumption. These materials can improve both the carbon footprint and the durability of green building heritage. Current research predominantly focuses on intervention-based energy-saving measures, such as wall insulation155, roof insulation, and window retrofitting, which enhance the structural performance of green building heritage while simultaneously improving environmental comfort. These solutions adhere to the principles of “architectural harmony,” “material recognizability,” and “minimal environmental intervention.” However, their structural integration with green building heritage does not fully align with the principle of “reversibility.” Future research on intervention-based energy-efficient materials for green building heritage should not only aim to improve their efficiency but also prioritize ease of installation and reversibility. Conversely, non-invasive, novel energy-saving materials—such as solar-absorbing coatings156, energy-generating tiles157, high-efficiency insulation coatings158, and heat-reflective films159—can be applied by spraying or adhering to the surfaces of green building components. These materials reduce energy consumption while providing power, and their ease of removal and replacement ensures compliance with the principles of “reversibility,” “material recognizability,” and “minimal environmental intervention.” However, their modern appearance may disrupt the original aesthetic of green building heritage, violating the principle of “architectural harmony.” Therefore, in the future, the development of non-invasive energy-efficient materials should focus on optimizing the adaptive exteriors of these materials, allowing them to actively adjust and harmonize with the original architectural style of green building heritage. Given the current high-quality technological advancements, the future trend will be to combine indigenous materials with novel, reversible, coordinated, and economically feasible energy-efficient materials. This will be crucial for enhancing both the energy efficiency and comfort of green building heritage.

Nanoparticles remarkably enhance the strength, firmness, and durability of composite materials, which is of paramount importance for reducing energy consumption and extending the lifespan of green building heritage. Materials such as functional mortars160,161,162,163,164,165, aerogel composites166,167,168, and composite phase-change materials150, for example, have been shown to improve the acoustic insulation, thermal resistance, heat endurance, and self-cleaning properties165 of green building heritage. These materials can also regulate indoor temperature and humidity, and, when customized to match the appearance of the original materials of the heritage, they can effectively enhance comfort without compromising the integrity of the environment. This approach adheres to the principles of “architectural harmony,” “material recognizability,” and “minimal environmental intervention.” However, the removal of such materials, often achieved through methods such as manual scraping, chemical decomposition, or laser heating, presents considerable challenges and may lead to damage of the original building, violating the principle of “reversibility.” On the other hand, reversible materials use natural fibers or biopolymers as substrates, reducing environmental burdens and energy consumption during disposal and enabling renewable recycling. In summary, improving the strength, resistance, coordination, and reversibility of composite materials is a key research direction in green building heritage. The development of composite materials with self-sensing and self-repairing capabilities, as well as those that allow for non-destructive removal and installation, will enable these materials to autonomously respond to environmental changes, adjust their properties, reduce relative energy consumption, minimize damage to heritage structures, and improve overall energy efficiency. This will be a major trend for future research in this field.

In terms of continuing traditional material techniques, to preserve the cultural authenticity of green building heritage, future composite materials should replicate the texture and appearance of traditional building materials without damaging architectural heritage or its historical aesthetics. By pre-treating the surface textures of composite materials and utilizing traditional material techniques, it is possible to accurately reproduce architectural elements and enhance cultural recognition169. Furthermore, these materials can be integrated with ecological design principles to ensure the harmonious coexistence between green building heritage and the natural environment, thus fostering a fusion of tradition and modernity. To restore green building heritage, new composite materials can be employed in conjunction with traditional craftsmanship techniques, such as mortise and tenon joints, molding, polishing, carving, and weaving. This intervention can improve the fundamental functionality of a heritage site while enhancing its energy efficiency, maintaining its original appearance, and adhering to the principles of “architectural harmony,” “material recognizability,” and “minimal environmental intervention.” However, this approach may not fully satisfy the principle of “reversibility.” In addition, non-invasive bio-material technologies, such as microbially induced carbonate precipitation170, can be applied to fill cracks and pores on the stone surfaces of heritage buildings through biogenic mineralization. This forms a continuous protective layer that enhances a building’s resistance to wind and salt corrosion, while retaining the original material’s appearance and craftsmanship. The close integration of this technology with heritage structures remarkably improves their structural durability and generally does not require removal. Additionally, the thermo-sensitive properties of bio-based adhesives allow for their complete removal upon heating, leaving no chemical residue and preserving the original condition of the building. This method satisfies the principles of “reversibility,” “architectural harmony,” “material recognizability,” and “minimal environmental intervention.” In the future, the protection and restoration of green building heritage should focus on the use of reversible technological solutions and the continuation of traditional material techniques, which would achieve a deep integration of modern technology and traditional craftsmanship.

Smart building heritage and digital-intelligent management systems

The digital transformation of building operations management is a critical strategy for reducing carbon emissions and enhancing energy efficiency. By leveraging digital-intelligent management systems, this approach utilizes simulation technologies to model scenarios and analyze the overall environment of smart building heritage. This allows for the development of targeted risk response frameworks aimed at bolstering the structural integrity of heritage sites and improving their modern usability. Concurrently, a unified digital-intelligent monitoring system can be established to meet both intelligent and personalized user needs, ensuring the preservation of heritage values while optimizing energy management and spatial utilization. The prospects of this field lie in three key areas: enhancing the safety and convenience of functional spaces, exploring the integration of virtual and physical simulation technologies in application scenarios, and advancing intelligent and personalized services in spatial environments.