Abstract

Identification of archaeological wood species is critical for decoding the biogeographical, historical, and cultural narratives of artifacts, but remains a challenge in practice. To address this challenge, we developed a deep learning framework integrating computer vision and archaeological wood species analysis. Images of modern and waterlogged archaeological wood specimens were collected and augmented through rotation, scaling, and contrast adjustments. The deep learning model was established through embedded self-attention mechanisms, optimizing feature extraction capabilities. The model yielded an overall accuracy of 94.20% on 12 modern woods and 97.83% on 2 archaeological woods. The binary classifier was further evaluated on three batches of archaeological woods and achieved the accuracy of 98.31%, 96.19% and 91.82%, respectively. The deep learning approach proposed in this study achieved good performance on waterlogged archaeological wood identification while requiring less wood anatomy expertise and minimal intervention of cultural artifacts, providing a critical advancement for archaeology applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Trees have profoundly influenced human societies across prehistoric and historic periods1. Beyond actively modulating ecological and cultural landscapes, trees furnish critical survival resources, including timber, fuel, food, and medicinal derivatives. The wood excavated from archaeological sites contains not only ecological information in relation to trees but also evidence of human activities. By analyzing the wooden relics, researchers can gain insights into ancient people’s use of wood, and explore the relationships between humans and nature, helping uncover connections between ancient people’s selection and utilization of wood, their production systems, and social structures. To some extent, such analyses also facilitate reconstruct regional vegetation, paleoenvironment, and paleoclimate2,3,4.

In recent years, significant researches have been conducted on wood excavated from archaeological sites in China, primarily focusing on the identification of materials used in funerary tools, burial objects, ships, and construction materials5,6. Among these studies, funerary tools and burial objects have received the most attention, particularly in the areas of Yangtze and Yellow Rivers, largely associated with waterlogged burial environments7,8,9,10. The selection of tree species by ancient peoples followed certain rules, especially in the context of burial tools and their relation to funeral customs, social hierarchy, and prevailing ideological concepts. The desire to better understand and preserve these cultural heritage for future generation has long been a major driver in the exploration of wooden relics in the natural science. For instance, due to the hierarchical system, tombs of the Chu State predominantly favored catalpa wood, especially for coffin construction in high-grade tombs11. In contrast, tombs from the Warring States Period in non-Chu Tombs, demonstrate a utilitarian selection of wood, maximizing the material’s utility12. An analysis of wood used in burial tools from the Western Han Dynasty reveals different classifications of wood based on tomb grade. High-quality woods like catalpa, phoebe, pine, and cypress, known for their strong resistance to corrosion and decay, were selected to ensure the long-term preservation of corpses in higher-grade tombs7,13,14,15,16. In the construction of tombs and the production of burial objects, vast quantities of wood were consumed. The selection and utilization of wood constituted a crucial element of the ancient funeral system, and in-depth research into this aspect holds great significance.

In order to understand how ancient peoples used wood and to analyze the relationships between ethnic groups, social hierarchies, burial practices, and ideological beliefs, identifying the species of archaeological wood is critically essential. The identification of archaeological wood are relying on traditional wood identification method conducted by experienced wood anatomists to examine anatomical features at both macroscopic and microscopic levels17. However, traditional techniques, which rely solely on visual observation, frequently fail to capture fine anatomical differences between closely related species, limiting identification to the genus or class level rather than the species level. Furthermore, traditional method requires taking wood samples from cultural relics, which can cause irreversible damage to the wooden relics. Identifying archaeological wood presents additional challenges due to degradation over time, which alters the wood’s appearance, texture, color, and anatomical features. This difficulty is exacerbated by a shortage of wood identification specialists, while archaeologists often lack the necessary expertise and must send the archaeological wood samples to laboratories for species determination18,19. Therefore, a fast and automated method for identifying archaeological wood species is urgently needed to support on-site excavations.

With the rapid advancement of machine learning, particularly deep learning, computer vision has emerged as a prominent research area in archaeology20,21,22,23,24,25. Machine learning methods are increasingly employed in the processing and analysis of wood images, aiming to address the challenge of accurately identifying wood at the species level26,27. The wood identification process using computer vision involves capturing images of correctly identified wood specimens, constructing a dataset from these images, and partitioning the dataset into training and testing subsets. The training subset is used to train the machine learning models, while the testing subset is employed for model evaluation28. However, the corrosion of archaeological wood during the burial process, leading to structural damage, chemical changes, and compression deformation significantly alter the appearance, complicating feature extraction and image recognition29. Moreover, the unique degradation processes of different archaeological wood samples result in significant variations in image features, requiring machine learning models to possess strong generalization capabilities30. Additionally, the limited availability of archaeological wood samples and the difficulty in obtaining large-scale labeled datasets pose challenges for training machine learning models.

To address these challenges, this study presents a deep learning-based approach for species identification of waterlogged archaeological wood. An image dataset of modern wood was created and image argumentation and self-attention techniques were applied to build state-of-art deep learning models. Archaeological wood images are captured through minimally invasive techniques, and the deep learning models are tested to perform species identification. The proposed method offers a convenient, automated, and reliable solution for the identification of wood species in archaeological studies.

Methods

Dataset creation

More than 1000 coffin logs were excavated from Wuwangdun Tomb dating back to the late Warring States period (475–221 BC) in Anhui Province of China, which has been recognized as one of China’s Top Ten New Archaeological Discoveries in 202431. A number of 100 wood samples with demisions of 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm were taken from these coffin logs using a sterile knife carefully and sent to the laboratory in Chinese Academy of Forestry for species identification. These samples were identified by experienced wood anatomists using traditional method, and the results shows two species, i.e., Catalpa ovata and Zelkova schneideriana.

Because of the rarity of wooden relics, it is difficult to process cultural relics and collect images on a large scale. Herein, modern wood specimens from Wood Collections of the Chinese Academy of Forestry (CAFw) were taken out for standard image dataset creation. This dataset was used to train deep learning models. To test the model’s ability of identifying archaeological wood, images of two wood species, i.e., C. ovata and Z. schneideriana, were collected from coffin logs of Wuwangdun Tomb.

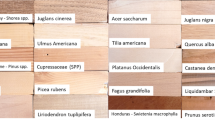

Standard images

The transverse end surface of the modern wood specimens are well polished successively with 180, 240, 400, 800, and 1000° of sanding in the laboratory, and the images are collected from the fine surface using a portable device of iWood system developed by the Research Institute of Wood Industry, Chinese Academy of Forestry32. In terms of hardware, it features an MT6761 CPU, a 5-inch high-definition touchscreen, and a 5000 mAh battery, alongside four low-angle side LED lights and two cameras, offers 8GB of storage space, and comes with a USB Type-C data interface and Wi-Fi connectivity. The camera system supports dual-mode shooting (macro and micro), featuring approximately 8.35 million effective pixels, delivering 8-megapixel high-definition images with a pixel size of 1.55 μm, ensuring exceptional light sensitivity, and supports 4 K video recording at 30 frames per second. The divice is also equipped with the iWood App, which can be downloaded from the Google Play Store and features functions such as image capture, species identification, wood name lookup, and a comprehensive gallery of common used wood species with images and descriptions. A total of 5661 high-quality images of 96 modern wood specimens, each with a resolution of 2048 × 2048 pixels, were captured to create a dataset consisting of 12 wood species, which are look-alike species and common used species for tombs in China including C. ovata and Z. schneideriana33 (Fig. 1). These images were divided into training and testing sets in an 8:2 ratio, maintaining proportional distribution across all species. The training set underwent further data augmentation using techniques such as image flipping and color jittering to enhance data diversity.

Archaeological wood Images: Images collected from archaeological wood are used for model generalization ability testing, focusing on two specific species, C. ovata and Z. schneideriana. As shown in the right panel of Fig. 1, we collected wood images in three batches using the same iWood device on site instead of taking destructive samples from the archaeological wood (Fig. 2). The first batch (89 images of C. ovata and 88 images of Z. schneideriana) comprised not-well polished wood samples sanded with sandpapers with grit size of 240°, 400° and 800°, the second batch (141 images of C. ovata and 95 images of Z. schneideriana) likewise from not-well polished specimens sanded with sandpapers with grit size of 240° and 400° and the third batch (83 images of C. ovata and 27 images of Z. schneideriana) from archaeological wood by cutting the transverse end surface slightly using a sterile knife. The sanding and cutting operations were conducted in full compliance with cultural relic preservation protocols, resulting in no discernible alteration to the archaeological wood’s appearance. These images are all 2048 × 2048 pixels, contain substantial noise, and thus pose a greater challenge for classification (Fig. 3).

For standard images, the number of images among classes varies, ranging from approximately 240 to 771 per species. The archaeological wood images include only two aforementioned species, with the first batch serving as the primary test set. We designed two experiments to evaluate model generalization: one using only the standard images for both training and testing, and another using all standard images for training and the first-batch archaeological images for testing, with the second and third batches serving as additional test sets to evaluate the model’s robustness and generalization across different surface conditions.

Image augmentation

Figure 1 highlights a notable imbalance in the distribution of images across wood species classes, which may bias the model toward over-represented categories. To address this issue, we adopted a dual strategy: first, we applied extensive data augmentation techniques to increase dataset diversity and visual variability; second, we incorporated class weighting into the focal loss function to compensate for imbalanced sample distributions during training.

To enrich the training set and improve robustness, we firstly random crop the original images, then applied data augmentation techniques to the images’ patches, including random brightness contrast, color adjustment, random rotation, random re-sizing, contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) and horizontal flipping, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The specific types, parameters, and implementations of all augmentation operations are listed in Table 1.

To further improve robustness to the wide range of lighting and contrast conditions encountered in field images, we apply two key image-level transforms in a unified pipeline. First, ColorJitter perturbs each original pixel intensity \(x\) (normalized to [0,1]) by adding a random brightness offset \({\grave{o}}_{b} \sim u(-0.2,0.2)\), yielding

and by scaling contrast with a factor \(1+{\mathop{{\rm{O}}}\limits^{\mbox{'}}}_{c}\), \({\mathop{{\rm{O}}}\limits^{\mbox{'}}}_{c} \sim u(-0.2,0.2)\), as

Analogous uniform disturbances are applied to saturation and hue in Hue, Saturation, Value (HSV) space, covering variations in brightness, contrast, saturation, and color tone.

Next, CLAHE34,35 divides the image into an 8×8 grid of tiles and, for each tile, computes its histogram \(H(i)\) over \(N\) bins. Each bin count is clipped at a specified clip_limit (2.0), then the total excess \({\sum }_{j}\,[H(j)-{\rm{clip}}\_{\rm{limit}}]\) is redistributed equally:

Local mapping functions are then bilinearly interpolated across tile boundaries to avoid visible seams. These comprehensive image-level augmentation strategies not only enrich the training data but also enhance the model’s generalization ability and robustness to varied field acquisition conditions.

In addition to data augmentation, we addressed class imbalance during training by assigning class-specific weights in the focal loss function36,37. The initial weights \({w}_{j}\) were computed as the inverse of the class frequency \({f}_{j}\):

These weights were then normalized such that \({\sum }_{j}{w}_{j}=1\). Furthermore, based on cross-validation performance, the weights of several underperforming or frequently confused classes (e.g., C. ovata) were empirically increased to further guide model optimization38. The final class weights were integrated into a customized focal loss function defined as:

where \(N\) is the number of samples in the batch, \(C\) is the number of classes, \({p}_{i,c}\) is the predicted probability that sample \(i\) belongs to class \(c\), \({y}_{i,c}\in \{0,1\}\) is the one-hot encoded ground truth label indicating whether class \(c\) is the true class for sample \(i\), The term \({w}_{c}\) denotes the class-specific weight, and \(\gamma\) is the focusing parameter used to down-weight well-classified examples and emphasize harder, misclassified ones.

Overall, this combination of class-weighted focal loss and targeted data augmentation mitigates the effects of class imbalance more effectively than synthetic oversampling techniques such as SMOTE39 or MixUp40, which may introduce unrealistic image features that are particularly problematic for anatomical texture classification. Our approach ensures both the visual realism of input data and the optimization of minority class performance.

Deep learning model architecture

In multi-class image classification tasks, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), especially those with very deep architectures, are predominantly employed41, while the Transformer can model long-range dependencies through a self-attention mechanism and improve the understanding of complex image features42. Therefore, in this study, we integrate a ResNet-5043 backbone with a Transformer encoder and decoder to combine strong local feature extraction with global context modeling (Fig. 5).

Specifically, the model takes a 640 × 640 pixels wood image as input to the ResNet-50 backbone. The backbone outputs three multi-scale feature maps from the last three stages of the backbone, each projected into a 256-dimensional space. Considering that a shallow encoder can effectively capture long-range dependencies while maintaining better generalization44, these multi-scale features are jointly fed into a single Transformer encoder layer to achieve global context modeling and cross-scale feature fusion. The encoder adopts the Multi-Head Self-Attention mechanism proposed by Vaswani et al.45, with the scaled dot-product formulation defined in Eq. (7):

where \(Q\), \(K\), and \(V\) are the query, key, and value matrices, and \({d}_{k}\) is the key dimension used for variance-stabilizing scaling. Following the encoder, a six-layer Transformer decoder is employed to progressively refine the encoded representations and enhance feature discrimination. This depth choice is consistent with the standard configuration of the Deformable DETR architecture proposed by Zhu et al.46, which has been shown to strike a favorable balance between representational capacity and computational cost. The decoder aggregates information from multiple backbone stages through Multi-Head Self-Attention in combination with Multi-scale Deformable Attention. The latter adaptively samples a small set of learnable key points from multi-resolution features, enabling accurate spatial alignment and robust feature fusion under complex visual conditions. Table 2 summarizes, for each component, the inputs, outputs, strides with respect to the input image, the channel and dimension settings, and the attention modules.

After decoding, a linear classifier maps the final representation to logits \(z\in {{\rm{R}}}^{C}\) for \(C=12\) classes. Class probabilities are obtained by the softmax in Eq. (8).

The predicted class is the one with the maximum probability, where \(p\left(y={c|x}\right)\) denotes the predicted probability of class \(c\) given input \(x\), \({z}_{c}\) is the logit for class \(c\). This design allows the model to capture long-range dependencies and complex texture patterns while preserving strong local representations, leading to improved accuracy and robustness in the classification task. In this study, the model’s prediction results in a probability distribution over 12 classes, with the class corresponding to the highest probability selected as the final classification result (as illustrated in Fig. 5).

Model training and testing

Training phase. Firstly, the standard dataset is used to train the model of 12 modern wood species. Due to the imbalance in data quantity across classes, different initial weights were assigned to each class based on the data quantity to balance the model’s attention. During training, the model continuously updated these weights, particularly fine-tuning them for classes that were easily confused, to improve classification accuracy. To further optimize model performance, the AdamW optimizer was used, which controls model complexity through regularization to prevent overfitting47. Additionally, exponential moving average (EMA) was used as a smoothing metric to reduce parameter update fluctuations, making the model more stable and improving generalization during training. EMA has been widely adopted in computer vision tasks such as object detection, semantic segmentation, and image classification, where it helps stabilize convergence and maintain a performance baseline during training by maintaining a shadow copy of model parameters that evolves more smoothly than the raw weights. Following its proven effectiveness in works such as Mean Teacher48, we applied EMA to ensure stable training dynamics and reduce the impact of noisy parameter updates, which is particularly beneficial in datasets with class imbalance and complex intra-class variations.

Figure 6 shows the Focal Loss variations during the training phase for both the standard images and the archaeological wood images. The blue line represents the loss curve for the standard dataset, while the orange line indicates the loss for the archaeological wood image dataset. In the early training epochs, the loss curve for the standard images is higher than that for the archaeological wood images, reflecting differences in dataset distribution and preprocessing. As training progresses, both curves converge to similar and low loss levels, indicating that the model can transfer the texture features learned from standard images to archaeological images, demonstrating its robustness under conditions such as texture degradation or vessel occlusion.

Testing Phase. In addition to the 12-class test images from the standard dataset, we introduced archaeological wood images solely for validation. The 12-class standard dataset was first split into training and test subsets at an 8:2 ratio, with the model trained exclusively on the training portion. Performance was then evaluated on both the standard test set and the first-batch archaeological images of C. ovata and Z. schneideriana. To further adapt the framework to the practical scenario of archaeological species identification, where only these two species were available, we developed a dedicated binary classifier. This binary model was trained on the same standard dataset, using the first-batch archaeological images as a validation set for selecting optimal weights. The selected weights were subsequently applied for direct inference on the second- and third-batch archaeological images.

In the formal testing phase of the binary classification model, the first-batch not-well polished images were used to evaluate baseline robustness and exhibit obvious pore occlusion and pronounced texture irregularities. The second-batch not-well polished images further verified performance consistency under similar surface conditions. The third-batch slight-blade-cut images were employed to assess generalization across different surface treatments; these razor-cut surfaces suffer more severe texture loss than the not-well polished specimens. Model performance was quantified using Recall and Precision as defined in Eq. (9) and Eq. (10).

True Positive (TP): Wood species A is correctly identified as wood species A.

False Positive (FP): A different wood species is incorrectly identified as wood species A.

True Negative (TN): Wood species other than A is correctly identified as not being wood species A.

False Negative (FN): Wood species A is incorrectly identified as a different wood species.

Top-1 and Top-3 accuracy is defined as the proportion of test samples for which the model’s top-ranked prediction matches the ground truth label, mathematically expressed as:

where \(N\) is the total number of test samples, \({\hat{y}}_{i}\). is the predicted label (i.e., the class with the highest predicted probability) for the \(i\)-th sample, \({y}_{i}\) is the true label, \(1(\cdot )\) is the indicator function that equals 1 if its argument is true and 0 otherwise, and where \({\hat{Y}}_{i,3}\). represents the set of the three highest-probability predicted classes for the \(i\)-th sample. Top-3 accuracy measures the proportion of test samples for which the correct label appears within the model’s three most confident predictions.

Implementation details and reproducibility

The proposed method is implemented using PyTorch 2.0.1 and accelerated with CUDA 11.8. All experiments are conducted on a workstation running Ubuntu 22.04.4 LTS equipped with an NVIDIA A100 GPU (80GB VRAM). The model is optimized using the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of 5e-5, betas 0.9, and a weight decay of 0.005. Training is performed with a batch size of 8 for at least 10 epochs. An exponential moving average (EMA) with a decay of 0.999 is used to stabilize training. The total number of trainable parameters in the model is approximately 42.7 M.

To address class imbalance, the focal loss function is combined with a class-weighting scheme, where initial class weights are computed as the inverse of class frequency and subsequently normalized. The final normalized weights applied during training are approximately: [0.0182, 0.2663, 0.0839, 0.0557, 0.0376, 0.0292, 0.1047, 0.0219, 0.0586, 0.0206, 0.0714, 0.0500, 0.1821], corresponding to the 12 wood species listed in Fig. 1 in alphabetical order from top to bottom, ensuring reproducibility. An additional background-class weight (eos_coef = 1 × 10⁻⁴) is applied to the end-of-sequence (EOS) category, which represents predictions assigned to “no-object” cases. This very small value reduces the influence of background predictions on gradient updates, allowing the network to focus on learning discriminative features of the target classes.

To further quantify computational efficiency, we measured the average batch processing time during inference on the NVIDIA A100 GPU, excluding outliers using the interquartile range method. The results indicate that the average time per batch for standard images is approximately 0.49 s, while archaeological wood images require around 0.68 s due to their higher resolution and more complex surface textures. The distribution of batch times for both datasets is illustrated in Fig. 7, highlighting the relatively stable inference speed across different input conditions.

Results and discussion

The discrimination of twelve modern woods species and two archaeological woods

For these 12 species, all images of C. ovata, Cinnamomum camphora, Kalopanax septemlobus and Ulmus pumila were correctly discriminated (Fig. 8). Few images of Betula albosinensis, Phoebe chekiangensis and Z. schneideriana were misidentified to another species, and it’s not surprising that Phoebe chekiangensis was predicted as Phoebe sheareri within the same genus, due to their similarity in the appearance49. It is interesting that the other four specie of Phoebe, P. bournei, P. hungmaoensis, P. nanmu and P. sheareri showed the similar accuracy (around 90%), and most of the misidentified images were assigned to the species within the genus and few to its phylogenetic related species (Cinnamomum camphora), and this result is highly consistent with previous studies50. Specifically, Phoebe neurantha has a low identification accuracy (51.00%), and nearly half the images were misidentified to P. nanmu, P. bournei and P. sheareri. The genus Phoebe, within the family Lauraceae, is predominantly distributed across Asia and tropical America, with 34 species and 3 varieties native to China51. The congruence in geographical distribution, climatic conditions, and edaphic factors has engendered analogous xylological traits within the genus, thereby presenting a formidable challenge in the accurate identification of timbers derived from these species. The results indicated that the deep learning model designed in this study have a relatively high resolution to discriminate these 12 species, especially between genera. As shown in Table 3, the recall and precision for each of the 12 species were calculated, resulting in an overall accuracy of 94.20%. Notably, the genus Phoebe exhibits an average recall of 88.25% and an average precision of 89.21%, whereas all other genera achieve over 95% average precision. It is noted that the images used for model training and testing were collected from scientific wood collections, where the wood specimens were carefully polished to capture fine anatomical details. This condition may lead to the model exhibiting stronger discrimination performance on high-quality images, while its accuracy could decrease when applied to noisy images, such as archaeological wood specimens with surface degradation or occluded vessels19.

To further investigate the contribution of the self-attention mechanism, we compared our proposed CNN–Transformer hybrid model against two representative baselines: ResNet-5043, which does not incorporate attention, and ViT-Base52, a pure Transformer architecture with global self-attention. As shown in Table 4, ResNet-50 achieved 90.28% top-1 accuracy on standard images, while ViT-Base reached 92.47%. Our model, integrating a CNN backbone for local feature extraction with a Transformer encoder-decoder for global dependency modelling, achieved the highest accuracy of 94.20%. This demonstrates that combining local and global feature representations via the self-attention mechanism provides a tangible performance gain over both CNN-only and Transformer-only baselines. We adopted an input size of 640 × 640 for our model to capture fine-grained anatomical details in high-resolution wood images, which is critical for distinguishing between closely related species. In contrast, ResNet-50 and ViT-Base were evaluated at their standard input size of 224 × 224, as these models are designed and pre-trained for this resolution, and directly increasing the input size would require substantial retraining and re-tuning to avoid degraded performance due to mismatched receptive field scaling. Our goal here was to provide a fair baseline comparison using each architecture’s typical configuration, rather than re-engineering the baselines, to isolate the effect of the attention mechanism itself.

Identification of archaeological wood species

A total of 89 images of Catalpa ovata and 88 images of Zelkova schneideriana were collected from the archaeological wood excavated from the Wuwangdun Tomb, corresponding to the first-batch on-site sampling. As shown in Fig. 9, when tested on these archaeological images using the model trained on 12 modern wood species, the overall accuracy reached 97.83%, with C. ovata achieving 98.17% recall and Z. schneideriana achieving 97.46% recall. However, when identify these samples using the traditional method, the personnel engaged in the preservation of cultural relics are required to take samples from the cultural relics, which are subsequently submitted to a wood identification laboratory for analysis. In the laboratory, sectioning of wood tissue was conducted and examine these sections microscopically, and then juxtapose them with reference materials housed in the wood collections to ascertain the result49. Typically, the entire process takes a minimum of two or three days to complete53. Compared to traditional wood anatomy techniques, which require destructive sampling and time-consuming microscopic analysis, deep learning approach offers a non-destructive and efficient alternative. By simply capturing images of archaeological wood using iWood device on-site, the model can rapidly predict species, making this method especially valuable in archaeological contexts where timely and accurate material identification is crucial. Moreover, this approach reduces the dependency on specialized wood anatomy expertise to some content3, enabling archaeologists to perform effective species identification with less-time training in wood science.

As detailed in Fig. 10, the model correctly classified 136 of 141 C. ovata images (96.5% recall) and 91 of 95 Z. schneideriana images(95.8% recall). Only a handful of misclassifications occurred, illustrating that moderate surface noise and irregularities exert minimal influence on the model’s discriminative power. The near-identical performance compared to the first-batch results confirms that, so long as key anatomical features are preserved, the network’s learned representations remain stable across modest variations in polishing quality. Furthermore, the balanced error rates for both species indicate no systematic bias toward one taxon, this consistency in performance on similarly processed samples is crucial for practical field use, where sample preparation may be complicated54.

Using the model weights from first-batch evaluation, we performed direct inference on the third-batch blade-cut images and achieved a Top-1 accuracy of 91.82% (Fig. 11). As Fig. 12 shows that C. ovata maintained a high recall of 97.6% (81/83), whereas Z. schneideriana achieved a lower recall of 74.1% (20/27). This discrepancy is partly attributable to the novel surface noise and edge artifacts introduced by blade-cut preparation, which can obscure key anatomical features. In addition, the relatively small evaluation size for Z. schneideriana (n = 27) makes the recall value more sensitive to a few misclassifications. Limited representation of blade-cut images for this species in the training data and the increased inter-class similarity under texture loss conditions further contribute to the performance gap. Nonetheless, the model still maintained over 90% overall accuracy on these challenging specimens, reflecting its ability to capture discriminative anatomical patterns. The third-batch blade-cut images were captured with minimal intervention to the archaeological wood specimens, ensuring the authenticity and integrity of cultural relics.

The deep learning model demonstrates strong discriminative power and robustness across polished modern specimens and noisy archaeological samples. It achieved nearly perfect accuracy on 12 modern wood species, with outstanding inter-genus distinction. When applied to archaeological wood, the binary classification model delivered approximately 98.31% accuracy on first-batch not-well-polished images. It sustained high performance on second-batch not-well-polished images with 96.19% accuracy and on third-batch blade-cut samples with 91.82% accuracy despite varying surface conditions. These results show that the model can reliably extract key anatomical features under diverse noise and preparation scenarios and provide a rapid image-based alternative to traditional wood anatomy2,55. This performance gradient validates the adaptability of selected model to real-world archaeological scenarios where specimen preparation quality varies substantially. The approach requires minimal specialized sampling or expert processing and offers practical value for in-situ wood identification in archaeological and conservation settings.

The application of deep learning in archaeological wood identification

Deep learning has seen increasingly widespread application in archaeological wood identification: for instance, explainable classifiers applied to microscopic images of endangered wood have not only achieved high recognition accuracy but also illuminated the anatomical features driving the model’s decisions27, and multi-scale convolutional networks integrated with portable near-infrared spectrometers have enabled rapid, non-destructive identification of weathered and degraded wood in the field56. Building on these advances, our study demonstrates the significant potential of deep learning models augmented with a rich suite of image-enhancement techniques and self-attention modules to identify archaeological wood species. As shown in Fig. 8 and Table 3, the model achieved high accuracy in species classification tasks. However, archaeological wood samples are often influenced by environmental factors, which can result in images with noise, distortion, or low resolution. To address these challenges, this study incorporates image augmentation techniques and attention mechanisms into the deep learning framework.

Image augmentation stands as a pivotal technique within the realm of deep learning, demonstrating notable efficacy in scenarios involving images with substantial noise or inferior quality27. This process involves subjecting original images to a spectrum of transformations, thereby generating a rich and varied training dataset, which in turn markedly bolsters the model’s resilience in intricate environments. Within the specific context of wood sample analysis, the deployment of image augmentation techniques is indispensable. This necessity arises from the challenging acquisition of wood specimens, the scarcity of samples at hand, and the inherently destructive process associated with sampling archaeological wood. The utility of image augmentation is further underscored by its capacity to maintain the fidelity of the original image data while amplifying texture attributes and broadening the scope of the dataset. Beyond simulating the diverse visual conditions encountered in practical settings, this technique fortifies the model’s ability to generalize from the training data to unseen scenarios.

To capture wood anatomical features at multiple spatial scales, each 2048 × 2048 image was systematically divided into a set of cropped patches at varying resolutions—8 at 1000 × 1000, 6 at 1200 × 1200, 4 at 1400 × 1400, and 2 at 1600 × 1600 pixels. This multi-scale cropping strategy is designed to improve the model’s sensitivity to anatomical details that may manifest differently across magnifications. The patch sizes were empirically chosen to strike a balance: on one hand, they are large enough to preserve essential macro-level features such as vessel distribution and fiber orientation; on the other hand, they are small enough to enable multiple samples per image, facilitating dataset expansion. Multiple patches per image also reduce overfitting risks and improve statistical diversity, especially for underrepresented classes. Following cropping, each patch was subjected to a series of augmentation operations including color jitter, brightness and contrast perturbation, random rotation (±30°), CLAHE, resizing, and horizontal flipping. These transformations are summarized in Table 1, which lists the parameter settings used.

To assess the effectiveness of geometric augmentation, we conducted comparative experiments with and without rotation. As shown in Table 5, introducing rotation raises Top-1 accuracy on the second-batch not-well-polished set from 95.75% to 96.19%, and on the third-batch blade-cut set from 90.40% to 91.82%, confirming that rotation significantly enhances performance consistency on similarly processed samples. Moreover, this combined cropping and rotation scheme effectively enlarges the dataset and reduces overfitting19,57. By simulating different angles and scales, the model learns orientation-invariant and scale-robust anatomical representations, which is especially beneficial for underrepresented classes in the archaeological wood dataset.

Photometric adjustments were also carefully selected. Among them, CLAHE was particularly effective in enhancing local contrast while avoiding the global noise amplification often associated with conventional histogram equalization. This technique adaptively redistributes pixel intensities within local tiles, making it especially suited to uneven illumination conditions. Wu et al. demonstrated the robustness of CLAHE in enhancing image details without introducing excessive noise, especially in scenarios involving degraded image quality58,59. This supports its use in our archaeological wood dataset, where visual degradation is common due to sample aging and uneven lighting. Figure 13 compares sample patches before and after CLAHE, showing crisper cell boundaries and richer texture details. Together, these photometric augmentations preserve fine anatomical structures while broadening the model’s resilience to real-world illumination shifts and low-contrast scenarios.

Together, the synergistic use of multi-scale cropping, rotation, and localized photometric enhancement not only expands data diversity but also serves the specific visual challenges posed by archaeological wood. Rather than generic augmentation, these strategies reflect deliberate choices made to accommodate the non-standard visual characteristics of heritage biological materials.

In this study, we also explored the positive impact of the self-attention mechanism on wood species classification, particularly its ability to focus on critical anatomical features such as the arrangement of axial parenchyma near the vessels. The introduction of the self-attention module allows the model to adaptively focus on key regions of the image, overcoming the limitations of traditional convolutional neural networks in capturing long-range dependencies52. By effectively modeling both local and global dependencies, the self-attention module enhances the model’s overall understanding of wood anatomical structures, especially when discriminating between closely related species, where subtle feature differences play a crucial role. Feature visualization results in Fig. 14 show the self-attention maps generated by the Transformer encoder in our model, rather than early-layer convolutional feature maps. The color intensity reflects the attention weight assigned to each spatial location, with warmer colors (red/yellow) indicating higher attention. The highlighted activation regions are predominantly concentrated around the vessels and the surrounding axial parenchyma, demonstrating the self-attention mechanism’s ability to accurately capture these critical anatomical features18. By assigning varying attention weights to different regions, the model automatically focuses on areas essential for species differentiation, thus significantly improving classification accuracy. Moreover, by combining the self-attention mechanism with the ResNet-50 backbone, we not only enhanced the feature extraction capability of the model but also enabled it to capture both local and global dependencies effectively. Traditional CNNs, which may struggle with long-range dependencies, the Transformer architecture, through the self-attention mechanism, addresses these challenges, achieving a significant improvement in model accuracy and robustness60,61. The integration of CNNs and Transformers allows the model to handle more complex and diverse wood sample features, resulting in improved classification performance, particularly under varying image quality and environmental conditions in archaeological field.

The archaeological significance of wood identification

Wood, as a significant carrier of ancient cultural heritage, plays a pivotal role in archaeological research through species identification. Scientific analysis of the timbers in Wuwangdun Tomb has confirmed that C. ovata and Z. schneideriana woods were the primary materials used62. This discovery sheds light on the construction system of the royal tombs of the Chu State and highlights their multidimensional academic value31. The choice of tree species reflects the resource utilisation wisdom of ancient societies. C. ovata and Z. schneideriana are native tree species in China and widely distributed in the area of Wuwangdun Tomb, which reveals that the inherent wisdom of ancient people in utilizing locally available materials to construct tombs, demonstrating their harmonious adaptation to the natural environment63. Additionally, C. ovata and Z. schneideriana woods has good physical properties with outstanding decay resistance, and are perfect for burial environments64. This precise correspondence reflects the ancient people’s profound understanding of material properties, providing valuable physical evidence for the study of engineering technology during the Warring States period. Furthermore, the selection of tree species has rich cultural connotations. C. ovata wood was found in a large number of royal-level tombs, forming the ‘Catalpa Palace’ burial ritual system in ancient China33. The determination of species used for the Wuwangdu Tomb deepens our understanding of the spiritual dimension of Chu culture. Therefore, Wood identification serves as a crucial approach to unveiling ancient material civilization, social systems, and ecological awareness. In the era of artificial intelligence, deep learning models will provide novel tools for wood identification, thereby making the authentication of archaeological wood simpler, more efficient, and more accurate, while fostering cross-disciplinary integration between computer science and archaeology.

The global excavation of wooden cultural relics has yielded a substantial corpus of archaeological wooden remains. The species identification of archaeological wood is critical for uncovering natural, historical, and cultural information embedded in these artifacts, but is also challenging for archaeologists. This study proposes a deep learning-based approach for archaeological wood species identification to address longstanding challenges in this field, including the scarcity of archaeological wood image datasets, the destructive sampling requirements of traditional methods, prolonged analysis time, high costs, and the limited expertise of archaeologists in wood identification. This study provides a simple, convenient, and reliable tool for archaeologists, with promising applications in archaeological wood species identification. Limitations remains that we only build deep learning models on the waterlogged archaeological wood, not applied to charred wood and other archaeological wood, due to the lack of image dataset. Future work would focus on expanding reference datasets to cover more archaeological wood species and promoting the broader adoption of this technology in archaeological applications.

Data availability

We have made the code of the deep learning models used in the manuscript publicly available on website (https://github.com/Linaikun77/iWood-pytorch). Data inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Roberts, P. et al. The deep human prehistory of global tropical forests and its relevance for modern conservation. Nat. Plants 3, 1–9 (2017).

Cartwright, C. R. The principles, procedures and pitfalls in identifying archaeological and historical wood samples. Ann. Bot. 116, 1–13 (2015).

Jiao, L. et al. Molecular archaeology of wood: Progress and prospect. S. Silv. Sin. 60, 118–127 (2024).

Radkau, J. Wood: A History. (Wiley, 2012).

Chen, H. et al. Rosin reinforcement and protection of the unearthed outer coffin from the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng in Hubei, China. Herit. Sci. 12, 247 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Systematic study of the material, structure and lacquering techniques of lacquered wooden coffins from the Eastern Regius Tombs of the Qing Dynasty, China. Microchem. J 168, 106369 (2021).

Zhang, G. et al. Wood analysis of an outer coffin unearthed from the Qian Zhang tomb (AD 1535) in Wuxi of East China. J. Ethnobiol. 36, 930–952 (2016).

Yang, Y. et al. Wood utilized for wooden components in ancient buildings of Tingbao Yang’s former residence. IAWA J. 45, 535–552 (2024).

Guo, J. et al. Deterioration of the cell wall in waterlogged wooden archeological artifacts, 2400 years old. IAWA J. 40, 820–844 (2019).

Liu, Y. Archaeological manifestations of rank and status, the wooden chamber tombs in the Mid-Yangzi Region (206 BC-AD 25), University of Oxford (2015).

Zhou, Y. et al. Versatile cross-linking strategy using water-soluble silane and dialdehyde for consolidation and dehydration of waterlogged archaeological wood. Wood Sci. Technol. 59, 20 (2025).

Zhou, M. et al. The Spring-Autumn and Warring States period coldness (400–350 BCE) contributed to the social unrest evidenced from coffin tree rings in southeastern China. Quat. Sci. Rev 369, 109617 (2025).

Yuan, C., et al. Species identification and chemical analysis of coffin wood in the Han Dynasty excavated in Xuzhou. J. For. Eng. 4, 52-59 (2019).

Wang, Q. et al. The wood in the pits of terracotta figures and its architectural application. J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 555–561 (2009).

Wu, T. et al. The discovery and extraction of Chinese ink characters from the wood surfaces of the Huangchangticou tomb of Western Han Dynasty. Archaeol. Anthrop. Sci. 11, 4147–4155 (2019).

Cai, W. et al. Identification and characterization of wood from antique Chinese guqin zithers. J. Cult. Herit. 53, 72–79 (2022).

Gasson, P. How precise can wood identification be? Wood anatomy’s role in support of the legal timber trade, especially CITES. IAWA J. 32, 137–154 (2011).

He, T. et al. Developing deep learning models to automate rosewood tree species identification for CITES designation and implementation. Holzforschung 74, 1123–1133 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. How to discriminate wood of CITES-listed tree species from their look-alikes: using an attention mechanism with the ResNet model on an enhanced macroscopic image dataset. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1368885 (2024).

Bustos-Pérez, G. & Ollé, A. The quantification of surface abrasion on flint stone tools. Archaeometry 66, 247–265 (2024).

Sferrazza, P. Archaeological and experimental lithic microwear classification through 2D textural analysis and machine learning. J Archaeol. Method Th. 32, 31 (2025).

Sferrazza, P. Grey level co-occurrence matrix and learning algorithms to quantify and classify use-wear on experimental flint tools. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep 48, 103869 (2023).

Bonilla, S. D. & Mazzucco, N. A quantitative approach to decoding pottery technology: Confocal microscopy applied to the traceological and textural analysis of surface treatment. Journal of Archaeological ScienceJournal of Archaeological Science: Reports 64, 105152 (2025).

Youssef, D., Motto-Ros, V. & Abdel-Harith, M. Machine learning-based novel approach of image analysis in LIBS elemental mapping for discriminating archeological human bone. Spectroc. Acta Pt. B-Atom. Spectr. 224, 107108 (2025).

Eleftheriadou, A., McPherron, S. P. & Marreiros, J. Machine Learning Applications in Use-Wear Analysis: A Critical Review. J. Comput. Appl. Archaeol. 8, 188-205 (2025).

Voulodimos, A. et al. Deep learning for computer vision: A brief review. Comput. Intel. Neurosc. 2018, 7068349 (2018).

Zheng, C. et al. Opening the black box: explainable deep-learning classification of wood microscopic image of endangered tree species. Plant Methods 20, 56 (2024).

Zhou, Z.-H. Machine Learning. (Springer Nature, 2021).

Blanchette, R. A. A review of microbial deterioration found in archaeological wood from different environments. Journal of Archaeological ScienceJournal of Archaeological Science: Reports 46, 189–204 (2000).

Geiß, C. et al. On the effect of spatially non-disjoint training and test samples on estimated model generalization capabilities in supervised classification with spatial features. IEEE Geosci. Remote S. 14, 2008–2012 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Degradation state and preservation quality of archaeological bamboo from a 2000-year-old Chinese royal tomb. Herit. Sci. 13, 223 (2025).

He, T., et al. Iwood: an automated wood identification system for endangered and precious tree species using convolutional neural networks. S. Silv. Sin., 152-159 (2021).

Wang, S. Xylonarchaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice. (Science Press, 2022).

Zuiderveld, K. Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization. (Elsevier, 1994).

Campos, G. F. C. et al. Machine learning hyperparameter selection for contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization. EURASIP J. Image Vide. 2019, 59 (2019).

Lin, T.-Y., et al. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proc. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2980-2988 (IEEE, 2017).

Mukhoti, J. et al. Calibrating deep neural networks using focal loss. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 15288–15299 (2020).

Fernando, K. R. M. & Tsokos, C. P. Dynamically weighted balanced loss: class imbalanced learning and confidence calibration of deep neural networks. IEEE T. Neur. Net. Lear. 33, 2940–2951 (2021).

Chawla, N. V. et al. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 16, 321–357 (2002).

Zhang, H., et al. mixup: Beyond empirical risk minimization. In Proc. International Conference on Learning Representations 1-13 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. A survey of convolutional neural networks: analysis, applications, and prospects. IEEE T. Neur. Net. Lear. 33, 6999–7019 (2021).

Han, K. et al. A survey on vision transformer. IEEE T. Pattern Anal. 45, 87–110 (2022).

He, K., et al. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proc. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 770-778 (IEEE, 2016).

Wu, H., et al. Cvt: Introducing convolutions to vision transformers. In Proc. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 22-31 (IEEE, 2021).

Ashish, V., et al. Attention is all you need: Advances in neural information processing systems. In Proc. NeurIPS Proceedings (MIT, 2017).

Zhu, X. et al. Deformable detr: Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. In Proc. International Conference on Learning Representations, (2021).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. In Proc. International Conference on Learning Representations (2019).

Tarvainen, A. & Valpola, H. Mean teachers are better role models: Weight-averaged consistency targets improve semi-supervised deep learning results. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 1-10 (2017).

Jiao, L. et al. Ancient plastid genomes solve the tree species mystery of the imperial wood “Nanmu” in the Forbidden City, the largest existing wooden palace complex in the world. Plants, People, Planet 4, 696–709 (2022).

Hwang, S.-W. et al. Automated identification of Lauraceae by scale-invariant feature transform. J. Wood Sci. 64, 69–77 (2018).

Yin, W. et al. DNA Barcoding Provides Taxonomic Clues for Identifying Five Endangered Phoebe Species in Southern China. Plants 14, 2895 (2025).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proc. Int. Conference Learning Representations, (2021).

Dormontt, E. E. et al. Forensic timber identification: It’s time to integrate disciplines to combat illegal logging. Biol. Conserv. 191, 790–798 (2015).

Ravindran, P. et al. Field-deployable computer vision wood identification of Peruvian timbers. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 647515 (2021).

Čufar, K. et al. Anatomy, cell wall structure and topochemistry of water-logged archaeological wood aged 5200 and 4500 years. IAWA J. 29, 55–68 (2008).

Wang, J. & Perez, L. The effectiveness of data augmentation in image classification using deep learning. Convolutional Neural Networks Vis. Recognit. 11, 1–8 (2017).

de Geus, A. R. et al. Amazon wood species classification: a comparison between deep learning and pre-designed features. Wood Sci. Technol. 55, 857–872 (2021).

Wu, Z. et al. LTE-ACN: A human activity recognition system using lte signals and attention-guided convnext networks. IEEE T. Instrum. Meas. 74, 5505912 (2025).

Chen, H. et al. DCAM-Net: A rapid detection network for strip steel surface defects based on deformable convolution and attention mechanism. IEEE T. Instrum. Meas. 72, 1–12 (2023).

Wiedenhoeft, A. C. et al. Fraud and misrepresentation in retail forest products exceeds US forensic wood science capacity. PloS One 14, e0219917 (2019).

Wagle, S. A. Comparison of Plant Leaf Classification Using Modified AlexNet and Support Vector Machine. Trait. Signal 38, 79-87 (2021).

Zhang, Z. Chinese Cultural Relics Network, http://www.zhongguowenwubao.com/portal/DigitPager/paperDetail/publishdate/2025-01-10/paperId/21234/id/106985 (2025).

Dong, M. et al. Wood used in ancient timber architecture in Shanxi Province, China. IAWA J. 38, 182–200 (2017).

Cheng, J. Atlas of Woods in China. (China Forestry Publishing House, 1992).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Archaeological Talent Promotion Program of China (Grant No. 2025-206), the Youth Foundation Project of National Centre for Archaeology of China (Grant No. 2024-C-QN-001) and the Technical Service Project of the National Centre for Archaeology of China (Grant No. 2024-H-KJ-006). Yafang Yin gratefully acknowledges financial support by the China Scholarship Council (CSC) (Grant No. 202403270010). We would like to thank Mr. Yu Sun of the Research Institute, the Chinese Academy of Forestry and Mr. Hongli Chen of National Centre for Archaeology for image collection during the preparation of this manuscript. We sincerely thank Prof. Jiang Xiaomei for her kind assistance in the identification of archaeological wood species using traditional methods in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J Wang, Z Zhang; methodology, J Wang, A Lin and Z Zou; data analysis, J Wang and A Lin; investigation and resources, J Wang, Ling F, Y Lu, Z Zhang and Y Yin; writing—original draft preparation, J Wang and A Lin; writing—review and editing, J Wang and A Lin and Y Yin; visualization, J Wang and A Lin; supervision, Z Zhang and Y Yin; funding acquisition, Z Zhang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Lin, A., Fang, L. et al. Inferring ancient from modern: a deep learning approach for species identification of archaeological wood. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 675 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02254-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02254-0