Abstract

Archaeological Predictive Model is crucial for efficient site identification but faces challenges like high uncertainty in negative samples, limited accuracy, and simplistic analyses of site-environment interactions. This study, based on 189 Kushan-period sites in the Surkhandarya Region of Uzbekistan, introduces a kernel density estimation (KDE)-based strategy to improve negative sample selection. Five machine learning models, incorporating geomorphological, climatic, and terrain variables, were assessed for predicting site locations. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis was used to investigate the relationship between environmental factors and settlement patterns. Results show that the proposed strategy significantly enhances predictive performance, with AUC and accuracy increasing by 12.1% and 14%, respectively. Random Forest outperformed other models in robustness across various conditions. Land cover, slope, and precipitation emerged as key factors influencing site distribution. This research offers a novel framework for archaeological prospection, combining machine learning with environmental analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Contemporary archaeological practice is undergoing a methodological transformation driven by cutting-edge technologies, reshaping all facets of the research paradigm. In this context, machine learning, as a powerful computational analysis tool, exhibits significant potential to revolutionize archaeological research. Particularly in critical domains such as the automated classification and identification of excavated remains, the construction of predictive models for the geospatial distribution of sites, and the interpretation of archaeological data, ML is forging important new pathways for the discipline’s advancement1. The rapid expansion of human societies—marked by urbanization, infrastructure development, and agricultural intensification—poses escalating threats to cultural heritage. Consequently, archaeologists are confronted with the challenge of comprehensively discovering and safeguarding archaeological sites under constraints of limited time and resources2. Traditional archaeological survey methods, however, are often time-consuming, labour-intensive, and inherently characterized by a degree of randomness and inherent limitations. Therefore, enhancing the efficiency of site discovery through scientific methodologies has become a pressing imperative.

Early archaeological research primarily focused on human adaptation to the environment, positing that site selection aimed to minimize the effort required to obtain critical resources3. Geostatistical methods were widely applied because they effectively revealed the relationship between spatial patterns and environmental factors. In particular, regression kriging proved useful for simulating distribution patterns and reducing the effort required to locate archaeological sites4. Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) introduces spatial non-stationarity into archaeological prediction by allowing the effects of environmental factors to vary locally. It is often employed to assess the mismatch and bias of traditional global models across different geomorphological units. Related studies have demonstrated that GWR can more precisely reveal localized relationships between cemeteries, settlements, and environmental gradients, thereby providing a basis for zonal modelling and multi-scale sampling5. The advent and application of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) significantly propelled the development of archaeological predictive models6. Kvamme (1990) noted that GIS technology offered new possibilities for applying single-sample statistical tests in regional archaeological location analysis, providing a comprehensive description of the entire regional environmental context7,8,9. For small archaeological datasets, Vanacker et al. (2001) proposed using Monte Carlo simulations for environmental analysis, successfully applying this to Mesolithic sites in northeastern Belgium and revealing the importance of proximity to water sources in site selection10. Concurrently, researchers began to systematically analyze the distribution patterns of archaeological sites in specific geomorphological contexts using GIS databases. For example, Bauer et al. (2004) studied sites in the southern part of the lower Cuyahoga River valley in Ohio, exploring the influence of cultural activities, burial processes, geomorphological development, and archaeological surveys on site distribution patterns11. As research progressed, the methodologies for APMs became increasingly diverse, with growing emphasis on the testing and validation of model predictions. Finke et al. (2008) proposed a method for mapping probable locations of archaeological sites using Bayesian inference, emphasizing the importance of using both site and non-site data12. Jasiewicz and Hildebrandt-Radke (2009) combined multivariate statistics and fuzzy logic systems to analyze prehistoric settlement preferences in temperate lowland regions13. Meanwhile, the integration of archaeological theory with predictive modelling emerged as a new research direction. Verhagen and Whitley (2012) discussed the challenges of integrating contemporary archaeological theories with predictive models to overcome their perceived theoretical impoverishment14. Balla et al. (2013, 2014) successfully applied predictive models to locate tombs in Macedonia and discussed their broad application prospects in archaeological research and cultural heritage management15,16. Regarding predictive algorithms, methods initially applied in other geospatial analysis domains, such as landslide susceptibility and species distribution modelling—including Frequency Ratio (FR)17,18, Weights of Evidence (WoE)19, and Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt)20,21—began to be introduced into APM research, offering benchmarks for evaluating the efficacy of different approaches.

In recent years, the introduction of machine learning algorithms has brought revolutionary changes to archaeological predictive models, while the integrated application of advanced geospatial technologies has reached new heights22. Researchers began to compare the performance of traditional statistical methods with various machine learning algorithms. For instance, Noviello et al. (2018) compared GIS-based Multi-Parametric Spatial Analysis (MPSA) with the Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) model in archaeological prediction, also exploring the potential of remote sensing data23. Wachtel et al. (2018), through case studies in northern Israel and northeastern China, found MaxEnt models to be superior to logistic regression in both efficiency and results24. The application of advanced geospatial technologies such as high-resolution remote sensing imagery (e.g., multispectral, hyperspectral), Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) data, and Google Earth Engine (GEE) is becoming increasingly widespread25,26,27. Nsanziyera et al. (2018) successfully predicted archaeological sites in the desert regions of southern Morocco using remote sensing and GIS models 28.

In archaeological predictive modelling, environmental variables are essential explanatory factors whose selection, quantification, and integration directly shape a model’s explanatory power and predictive accuracy. Their theoretical foundation lies in the systematic coupling between human activities and environmental conditions. Recent advances have emphasized constructing variable systems with explicit spatiotemporal features through the integration of multi-source environmental data. Topographic variables, such as elevation, slope, aspect, terrain ruggedness, and curvature indices, are among the most widely used22,29,30,31,32,33. These variables capture surface morphology, which constrains settlement location, defensive strategies, visibility, and agricultural suitability. For example, gentle low-elevation slopes are often associated with cultivation and permanent settlement, whereas steep terrain may indicate temporary activities or specialized resource use. Hydrological variables—including distance to rivers, the Topographic Wetness Index, and water resource availability—are directly linked to essential water supply and irrigation potential. Archaeological evidence frequently shows nonlinear patterns of higher site density within certain distances of water sources13,34. Soil and geological variables, such as soil type, fertility, and mineral resource distribution, shape agricultural productivity, construction material access, and tool-making resources. Fertile alluvial soils, in particular, have been tied to the emergence of more complex agricultural societies35,36. Vegetation and land-cover variables, derived from remote sensing or paleoenvironmental reconstructions, reflect the availability of foraging and hunting resources, while also capturing anthropogenic impacts such as deforestation and burning37,38. Climatic variables—including temperature, precipitation, seasonal regimes, and paleoclimate proxies such as pollen sequences and lake cores—play a critical role over long timescales, influencing population movements, agricultural cycles, and cultural transformations35,39. Additional factors, such as coastal change40, geomorphic processes11, and visibility analysis16, also contribute to specific regional models. In recent years, both the spatial resolution and temporal depth of environmental variables have advanced substantially. Multi-scalar integrated modelling has become a dominant trend, with growing attention to nonlinear effects, variable interactions, and spatiotemporal nonstationarity. These developments are shifting predictive modelling from simple environmental correlations toward more sophisticated simulations of complex human–environment systems.

Currently, research on archaeological predictive models still faces several unresolved issues. Existing studies often employ traditional algorithms like Logistic Regression24,30,39,41, which, despite their simple structure and ease of implementation, frequently yield suboptimal predictive accuracy under the influence of complex environmental factors and struggle to fully capture the underlying patterns of site distribution. The selection of negative samples (non-site points) lacks scientific optimization strategies, typically being generated randomly, which leads to significant biases in sample distribution31,42. This randomness not only reduces the stability of model training but may also result in insignificant feature differences between site and non-site points, ultimately compromising the model’s predictive accuracy. Furthermore, current research predominantly relies on traditional mathematical statistical methods for analyzing site environmental factors39,43,44, while lacking necessary interpretability analysis for the prediction results of modern machine learning algorithms, thus failing to deeply reveal the specific impacts of environmental factors on site distribution 45.

Addressing these critical issues in archaeological predictive modelling, this study proposes a negative sample optimization strategy based on kernel density estimation (KDE) to mitigate the high randomness and inconsistent quality associated with traditionally selected negative samples, thereby enhancing the sample quality and overall performance of predictive models. Concurrently, we systematically explore the applicability of common and state-of-the-art machine learning methods in archaeological predictive modelling, evaluating the performance of different algorithms in complex environmental contexts to provide guidance for selecting appropriate predictive models. Furthermore, this research introduces the SHAP interpretability method into the study of APMs. By explaining model prediction results, it globally and locally analyzes the influence of environmental factors on prediction outcomes, aiming to further reveal the underlying driving mechanisms of archaeological site distribution.

Methods

Study area

The Surkhandarya River Basin, located at a crucial Central Asian crossroads of the Silk Road, served as a major thoroughfare for East-West cultural exchange, North-South agropastoral interactions, the convergence of diverse cultures, and the migration and fusion of various populations. The complex environment and resources of Central Asia prompted human civilizations in different zones—such as steppes, oases, and river valleys—to adopt distinct modes of production and lifestyles, including agriculture, pastoralism, and nomadism, resulting in a mosaic of coexisting cultures. The selection of settlement environments by early humans was the result of multiple interacting factors; natural conditions provided the foundation, while socioeconomic and technological advancements fostered the development and stability of settlements 46.

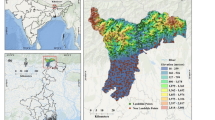

The study area for this research is the Surkhandarya Region in the southeastern part of the Republic of Uzbekistan. It is situated at the southern foothills of the Zarafshan and Gissar Mountains, which are remnants of the Western Tian Shan range, and lies between these two mountain systems, which have an average elevation of approximately 3000 metres. The region covers an area of about 20,800 km², bordered by Tajikistan to the east and north, Turkmenistan to the southwest, and Afghanistan to the south along the Amu Darya River. According to archaeological data accumulated over the past century, cultural remains unearthed in the Surkhandarya River Basin indicate that the cultures from the early ancient Yuezhi to the Kushan Empire period are the most abundant, with clear and continuous developmental trajectories observed for these two periods. Figure 1 shows the distribution of ancient city sites excavated to date by the joint Sino-Uzbek archaeological team, totalling 189 sites 47.

The map illustrates the physiographic background of the Surkhandarya River Basin, flanked by the Zarafshan and Gissar Mountains. Elevation gradients are shown from white (high) to blue (low). The Amu Darya River defines the southern boundary. Red dots represent 189 ancient sites documented by the Sino–Uzbek survey.

Environmental factors

A total of fifteen environmental variables were selected as input features for the archaeological site prediction model, covering five categories: topography, hydrology, climate, land cover, and soil type (Table 1). All preprocessing and calculations of environmental variables were conducted using ArcGIS 10.8 and SAGA GIS 9.9.0, with the coordinate system aligned to the basic geographic data of the study area.

The Digital Elevation Model (DEM) used for terrain analysis in this study is the 12.5-metre resolution product derived from the Phased Array type L-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (PALSAR) sensor, which was onboard the Advanced Land Observing Satellite (ALOS). As a radar-derived product (InSAR), this dataset is technically a Digital Surface Model (DSM); its elevation values represent the first reflective surface (e.g., vegetation canopies and built structures) rather than the bare earth. The reported absolute vertical accuracy for the associated ALOS World 3D (AW3D) product is estimated to be 5 metres (Root Mean Square Error, RMSE)48. From this DSM, a suite of topographic variables was extracted for analysis, including slope, aspect, positive openness49, multi-scale topographic position index (MS TPI)50, profile curvature, terrain ruggedness index (TRI)51, and relative deviation of land surface (RDLS)52. These variables collectively capture landform characteristics and surface accessibility, providing important insights into ancient human settlement choices. For example, gentle slopes are more suitable for habitation and agricultural development, while aspect influences solar radiation and microclimatic conditions, thereby affecting settlement decisions. Positive Openness and MS TPI assist in identifying geomorphological units such as plateaus and valleys; profile curvature reflects erosion–deposition processes; TRI express the combined effect of slope and local surface roughness. RDLS represent overall terrain complexity and mobility constraints, often used to assess defensive potential and resource distribution patterns.

Hydrological variables include the Topographic Wetness Index (TWI)53 and distance to rivers. TWI, derived from flow accumulation and slope based on the DEM, identifies areas with higher potential soil moisture, serving as an indicator of agricultural and water-management potential in antiquity. Distance to rivers was calculated using Euclidean distance to quantify site proximity to the nearest river, reflecting ancient reliance on water sources for drinking, irrigation, and transportation routes.

Climatic variables were obtained from the WorldClim database and include mean annual temperature, annual precipitation, mean annual wind speed, and annual solar radiation (SRAD). Climate factors directly shape crop growth cycles, habitability, and energy availability, thereby constraining the spatial extent of human activity and subsistence strategies. Paleoclimatic studies provide evidence of climate variability in Central Asia over the past 2,000 years. For instance, Uzbekistan indicate alternating warm-humid and cold-dry phases influenced by westerlies and moisture circulation from the Aral Sea basin54. However, these variations primarily reflect fluctuations in overall trends, while relative spatial patterns of precipitation may have remained stable, making modern datasets a reasonable proxy for modelling.

Land cover data were derived from the ESRI Land Use Land Cover product and reclassified into major categories to capture potential vegetation environments and the history of human disturbance. Soil texture data were obtained from the Harmonized World Soil Database v2.0, with emphasis on surface soil texture, serving as a proxy indicator for agricultural suitability 55.

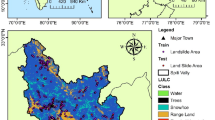

Variables were categorized as continuous or discrete. Continuous variables were subjected to a normalization process (dimensionless scaling) and subsequently classified into nine ascending levels using the natural breaks (Jenks) method to standardize the measurement scale (Fig. 2).

This multi-panel figure presents fifteen environmental factors after normalization and reclassification. a annual precipitation, b aspect, c slope, d terrain ruggedness index, e land use/land cover, f positive openness, g profile curvature, h soil type, i mean annual temperature, j multi-scale topographic position index, k distance to river, l solar radiation, m mean annual wind speed, n relative deviation of land surface, and o) topographic wetness index. These classified layers provide standardized inputs for archaeological site prediction.

Archaeological prediction framework

Figure 3 illustrates the primary workflow employed in this study, which comprises the following stages: (1) data preparation and feature factor optimization; (2) construction of an optimized sample dataset; (3) machine learning model prediction; and (4) model evaluation and analysis.

Machine learning models

Logistic Regression (LR): As a fundamental probabilistic discriminative model, LR maps a linear combination of inputs to a probability value within the [0,1] interval via the Sigmoid function, making it particularly suitable for binary classification tasks. Its output probability directly quantifies the likelihood of archaeological remains existing in a specific spatial unit, providing an intuitive basis for archaeological prediction. The model is trained by maximizing the log-likelihood of the observed data.

Random Forest (RF): This ensemble algorithm significantly enhances model robustness and generalization ability by constructing a multitude of decision trees and aggregating their predictions. Its core mechanism lies in a dual randomization process: Bootstrap sampling of training instances effectively mitigates issues of spatial autocorrelation and sample bias common in archaeological data; random selection of feature subsets during node splitting reduces model variance and improves its capacity to capture complex interactions among high-dimensional archaeological environmental covariates, Splitting criteria are used to optimize tree structure.

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost): As an efficient gradient boosting framework, XGBoost iteratively trains decision trees to fit the residuals of the current model, progressively correcting prediction errors. Its key advantages include the incorporation of explicit regularization terms (L1/L2 regularization) to control model complexity and the utilization of second-order derivative (Hessian) information from the loss function for more precise optimization. This effectively prevents overfitting on limited and potentially noisy sample data, thereby enhancing predictive accuracy.

Support Vector Machine (SVM): SVM aims to find an optimal separating hyperplane in the feature space that maximizes the margin between different classes of archaeological phenomena. This model is particularly adept at handling prediction problems with small sample sizes and high dimensionality. By employing kernel tricks, SVM can map originally non-linearly separable environmental data into a higher-dimensional space to achieve effective separation, addressing the complex non-linear mapping challenges between surface features and the distribution of subsurface remains 56.

K-Nearest Neighbours (KNN): KNN is a lazy learning algorithm based on spatial similarity. For a spatial unit to be predicted, its class membership is determined by a majority vote among the K nearest known sample points in the feature space, typically based on Euclidean distance. This method does not require explicit model training, and its predictions directly reflect the local clustering patterns of archaeological remains in the environmental feature space, demonstrating strong adaptability to local spatial heterogeneity 57.

SHAP interpretability framework

To elucidate the decision-making logic of complex “black-box” models in archaeological prediction, this study employs the SHAP interpretability framework. Grounded in the Shapley value principle from cooperative game theory, SHAP objectively quantifies the marginal contribution of each environmental covariate (feature) to specific prediction outcomes. By computing the average impact of a feature across all possible feature subset combinations, SHAP delivers transparent and individualized explanations for model predictions. This facilitates the identification of key environmental factors driving archaeological site distribution and their directional influence, thereby furnishing data-driven insights for the interpretation of archaeological mechanisms.

The SHAP value \({\varphi }_{i}\) for a feature \(i\) given a model \(f\left(x\right)\) is calculated as:

where:

\(S\) is a subset of features that does not include feature i.

\(N\) is the set of all features.

\(f\left(S\bigcup \left\{i\right\}\right)\) is the model’s prediction when considering the feature subset \(S\bigcup \left\{i\right\}\).

\(f\left(S\right)\) is the model’s prediction when considering the feature subset \(S\).

ROC curve (Receiver operating characteristic curve)

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the predictive models across various discrimination thresholds, this study utilizes ROC curve analysis. The ROC curve depicts the trade-off between the True Positive Rate (TPR), representing the correct identification of archaeological sites, and the False Positive Rate (FPR), representing the misclassification of non-sites as sites, across all possible threshold values. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) serves as a comprehensive metric, quantifying the overall ability of the model to distinguish between spatial units containing archaeological sites and those without. An AUC value approaching 1 signifies superior model performance in discriminating the spatial occurrence of archaeological remains.

The ROC curve is generated by plotting the True Positive Rate (TPR) against the False Positive Rate (FPR) at various threshold1 settings, illustrating the model’s classification performance across these thresholds.

True Positive Rate (TPR), also known as recall or sensitivity, represents the proportion of all actual positive samples that are correctly predicted as positive by the model. It is calculated as:

where \({TP}\) is True Positives and \({FN}\) is False Negatives.

False Positive Rate (FPR) represents the proportion of all actual negative samples that are incorrectly predicted as positive by the model. It is calculated as:

where \({FP}\) is False Positives and \({TN}\) is True Negatives.

Results

Optimization and selection of environmental factors

Pairwise correlation analysis, using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r), was performed on all independent variables to identify potential multicollinearity. The Pearson correlation coefficient quantifies the strength and direction of the linear association between variables, with a value range of [-1, 1]. Positive values approaching 1 signify a strong positive correlation, negative values approaching -1 indicate a strong negative correlation, and values near zero suggest a weak linear relationship. Adopting a commonly used empirical threshold in the domain (|r | ≥ 0.7)58,59, variable pairs with absolute correlation coefficients exceeding this value were identified as highly correlated, necessitating caution regarding their potential contribution to multicollinearity in subsequent regression analyses.

The pairwise correlation matrix (Fig. 4), displaying Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between site environmental indicators, revealed high correlations (r ≥ 0.7) between Slope and variables such as positive openness, RDLS, TRI, temperature, and SRAD. Consequently, after eliminating all factors exhibiting high correlation with the slope variable, a final set of ten environmental factors for archaeological prediction was determined.

Negative sample optimization Scheme

The sphere of influence of ancient settlements, as determined by kernel density analysis, exhibited spatial heterogeneity; in densely settled regions, these spheres overlapped, creating central zones of significant interaction, whereas isolated settlements demonstrated more expansive individual spheres of influence60. The randomly generated negative samples were spatially distributed uniformly, deliberately avoiding areas within the established settlement spheres of influence, aligning with their expected distribution characteristics. The methodology involved the following steps: first, areas within the spheres of influence identified by kernel density analysis were excluded; second, sample points were generated with a uniform random distribution within the remaining areas (Fig. 5); finally, the generated negative sample points are checked for spatial consistency. The consistency mainly includes checking the consistency of the coordinate system and checking one by one whether the non-site points coincide with the site points or fall into lakes, rivers and other areas to ensure that their distribution pattern accurately reflects the actual conditions.

Machine learning model accuracy comparison

The classification performance of five distinct machine learning models across datasets utilizing different negative sampling strategies was comparatively analyzed using ROC curves and performance evaluation metrics (Fig. 6). ROC curves illustrate the classification performance of each model at various thresholds, while performance metrics quantify the overall classification efficacy 61.

Receiver Operating Characteristic curves compare Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, Extreme Gradient Boosting, K-Nearest Neighbours, and Logistic Regression under random and kernel density sampling. The curves plot the true positive rate against the false positive rate across thresholds. Higher curves correspond to stronger discrimination.

Performance evaluation of five machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, KNN, XGBoost, SVM, and Logistic Regression) using different sampling methods for the archaeological prediction model yielded the following results (Table 2).

Under the random sampling method, Random Forest demonstrated the best overall performance, with an accuracy of 0.798, an F1 score of 0.785, and an AUC of 0.844. Conversely, Logistic Regression exhibited the weakest performance, with an Accuracy of only 0.737, an F1 score of 0.727, and an AUC of 0.808. With the kernel density sampling method, the performance of all models improved markedly. Random Forest maintained its superior performance, reaching an Accuracy of 0.912, and F1 score and AUC of 0.921 and 0.958, respectively. Other algorithms, such as KNN and SVM, both achieved an Accuracy of 0.912, with F1 scores of 0.922 and 0.921 respectively, demonstrating their robustness under kernel density sampling. Although Logistic Regression under kernel density sampling showed slightly lower performance compared to other models with this sampling, it still outperformed its random sampling counterpart, with an Accuracy of 0.895, an F1 score of 0.906, and an AUC of 0.944 (Fig. 6). Overall, the kernel density sampling method significantly enhanced all evaluated performance metrics of the archaeological prediction models, notably improving model robustness and classification capability.

Predictive outcome comparison

Figure 7 displays the predicted probability maps of archaeological site distribution in the study area generated by KNN、LR、RF、SVM and XGBoost models. The results reveal significant spatial variations in the likelihood of site presence, categorized into five probability levels: very low (0-0.3), low (0.3-0.5), medium (0.5-0.7), high (0.7-0.9), and very high (0.9-1.0) (Fig. 7). Areas with the highest probability (0.9-1.0) are concentrated in the central and southeastern parts of the region, marked in red, indicating the most evident aggregation of potential sites. These high-probability zones likely correspond to environmental and topographical conditions favourable for historical settlement 62,63.

Discussion

Archaeologists frequently employ two-sample statistical tests in regional locational analyses, comparing environmental measurements from known site locations with those from randomly selected locations within the broader landscape64. Previous research has often treated ancient settlements as discrete point locations, thereby neglecting their broader spatial influence55,61. This influence can encompass multiple facets, including resource distribution, cultural transmission, and social interaction networks. Consequently, investigating the extent of ancient settlement influence and quantitatively analyzing their spatial distribution characteristics is of critical importance.

Negative sample optimization strategies are frequently applied in landslide prediction models, where research has primarily focused on aspects such as the quantity, distribution strategy, and reliability of these samples62,65,66,67,68. Our comparative experiments revealed that negative sample optimization strategies significantly impact model performance. The introduction of negative sample optimization led to an average increase in AUC of 12.1% across the five machine learning models, an approximate 14% increase in accuracy, a 14.1% improvement in recall, and a significant growth in F1 scores. This demonstrates that negative sample optimization not only enhances the models’ learning capabilities but also effectively mitigates biases arising from the stochasticity of negative samples. Specifically, the negative sample optimization strategy yielded a particularly notable improvement in recall rates. Supported by this optimization, models could more comprehensively learn the distribution characteristics of negative samples, thereby more accurately distinguishing between potential archaeological sites and non-site areas based on environmental factors.

Methods for generating negative samples based on feature space similarity outperformed random generation methods, more closely approximating the distribution characteristics of non-site areas in actual archaeological contexts. This strategy significantly reduced model misclassification rates, particularly in small-sample environments. Prior archaeological predictive modelling research has predominantly focused on positive sample augmentation or data balancing techniques, with less consideration given to the importance of negative sample optimization8,14,61,69. In contrast to traditional random sampling, reliance solely on random sampling fails to effectively enhance model generalization capability; however, negative samples generated based on the kernel density of positive sample feature space can substantially improve model robustness.

This study investigated the predictive capabilities of various algorithms in an archaeological context and discussed their practical applicability. The five models were selected based on their widespread adoption and established theoretical advantages in classification tasks, considered in conjunction with the specific characteristics of archaeological geospatial data; this research aimed to develop more precise decision-support tools for site discovery.

Figure 8 shows that, under random sampling, Random Forest, SVM, and XGBoost exhibited broadly comparable overall performance, with accuracies of 0.798,0.789 and 0.781, and F1 scores of 0.785, 0.789 and 0.779, respectively. This suggests these three algorithms adapted well to the dataset, achieving relatively stable results. Random Forest demonstrated a balanced performance across accuracy, precision, and recall, indicating good generalization ability. SVM showed well-matched precision and recall, ensuring both low false positive rates and high detection rates. XGBoost, while having slightly lower accuracy, achieved an AUC of 0.849, demonstrating strong classification power. In comparison, KNN and Logistic Regression performed less adequately, particularly Logistic Regression, whose accuracy and F1 score were only 0.737 and 0.727, respectively, with an AUC of 0.808, suggesting limitations in handling complex non-linear data. Furthermore, although KNN achieved a recall of 0.808, its precision was only 0.754, indicating a high false positive rate alongside its high detection rate, which could impair the model’s practical utility.

With kernel density sampling, the performance of all algorithms improved significantly compared to random sampling. Random Forest, KNN, and SVM, in particular, delivered excellent results, each achieving accuracy and F1 scores exceeding 0.90. Specifically, both SVM and Random Forest exhibited high predictive performance, with identical accuracy (0.912) and F1-scores (0.921). The AUC value of SVM was slightly higher than that of RF, suggesting that SVM was somewhat more effective in capturing the underlying structure of the dataset and classifying categories accurately. However, when considering overall performance across both sample sets, Random Forest demonstrated greater stability and precision. KNN also demonstrated high accuracy (0.912) and F1 scores, but overall performance a little weak, further validating the efficacy of the kernel density sampling method in enhancing model performance. This improvement may be attributed to the data resampling strategy of kernel density sampling, which likely resulted in a more balanced training data distribution, thereby augmenting the models’ learning capacity. Moreover, XGBoost and Logistic Regression also showed marked improvements under kernel density sampling; XGBoost’s F1 score increased from 0.779 to 0.938, and Logistic Regression’s F1 score reached 0.906, demonstrating the general applicability of kernel density sampling across different model types.

Performance disparities among the machine learning algorithms also highlighted their respective strengths and weaknesses. Random Forest, an ensemble learning method, constructs multiple decision trees and aggregates their outputs, demonstrating strong robustness and generalization capabilities; its superior performance across all metrics under kernel density sampling underscores its suitability for complex archaeological prediction tasks70. While KNN excelled in recall, its relatively lower precision may be linked to its sensitivity to data distribution and susceptibility to noise. SVM, a hyperplane-based classification method, exhibited high precision and recall, particularly under kernel density sampling (0.912 precision, 0.921 F1 score), indicating strong classification ability and stability. XGBoost, a gradient boosting-based ensemble algorithm, showed a notable AUC, suggesting an advantage in distinguishing between classes, though its precision and F1 score were slightly inferior to Random Forest and SVM. Logistic Regression, a traditional linear model, though underperforming with random sampling, showed significant improvement with kernel density sampling, suggesting its continued utility when data distribution is balanced.

Overall, Random Forest emerged as the optimal model choice in this study due to its stability and superior performance. In contrast, while Logistic Regression performed relatively poorly with non-linear data, its enhancement via kernel density sampling suggests that linear models retain application value under specific conditions.

Existing research predominantly relies on simple mathematical statistical methods (e.g., regression coefficients from logistic regression models) to assess the importance of environmental factors. Such analyses are often confined to a global perspective and neither adequately integrate with the prediction algorithms themselves nor offer in-depth insights into individual site characteristics. Consequently, this study employed the SHAP method to elucidate the key drivers of the archaeological prediction model.

Since the random forest model has better accuracy and robustness, we conduct an explainable analysis on the prediction results of the random forest. An interpretive analysis of the archaeological prediction model revealed the contributions and mechanisms of different environmental variables in model predictions. Figure 9 presents the SHAP feature contribution plot for the Random Forest archaeological prediction model, illustrating the distribution of SHAP values for each feature and their positive or negative impact on model output. Figure 10, the SHAP feature importance ranking plot, further quantifies the importance of each feature, ordered by the absolute mean SHAP values. These interpretability plots provide empirical support for understanding the model’s predictive logic and offer a scientific basis for discussing the relationship between environmental variables and site distribution in archaeological research. As shown in Fig. 10, land use/land cover (LULC), slope, and precipitation were the three variables contributing most significantly to the model’s prediction outcomes, with mean SHAP values of 0.38, 0.22, and 0.15, respectively. This indicates these variables exert a dominant influence on predicting archaeological site distribution and are consistent with the known settlement patterns and environmental conditions of the Surkhandarya Basin.

LULC demonstrated the highest contribution to model predictions, with its SHAP values predominantly concentrated in the positive region, suggesting that specific land use types (e.g., agricultural land, residential areas) significantly increase the likelihood of site presence. This finding aligns with early human activity patterns, as settlements and agricultural activities typically favoured areas with abundant and easily exploitable land resources, which are more likely to preserve archaeological traces. The influence of slope was more complex than that of LULC32,71; the SHAP feature contribution plot (Fig. 9) indicated that slope SHAP values were distributed on both positive and negative sides, signifying a non-linear impact on archaeological site prediction. Figure 10 reveals that for gentle slopes, SHAP values were mostly positive, implying flatter terrain is more conducive to human activity and settlement. Conversely, as slope increases, SHAP values progressively shift to negative, indicating that steep terrain is unfavourable for human habitation and site preservation. Precipitation also exhibited a significant non-linear relationship: moderate precipitation levels showed positive SHAP contributions, while extreme levels negatively impacted predictions. This is likely because adequate rainfall provides favourable conditions for agriculture and human survival, whereas excessive or insufficient rainfall adversely affects environmental suitability, thereby reducing the probability of site occurrence. By contrast, the influence of MS-TPI and aspect is relatively modest, yet both exhibit distributions of positive and negative contributions, suggesting that micro-topographic variation and slope orientation exert a moderating effect on settlement location choices under specific local environmental conditions. In comparison, wind speed, soil type, profile curvature, and the topographic wetness index (TWI) make only limited contributions to the overall model predictions. This indicates that their explanatory power is weaker at the macro scale, although they may still play a supplementary role in particular regions or at finer spatial scales. The SHAP value distribution for plan curvature suggests that terrain features influence site distribution; for instance, flat or slightly convex areas are more likely to have been utilized by humans. Distance to rivers showed weaker positive and negative contributions; proximity to rivers is traditionally considered important for early human activities due to the critical role of water resources for survival and agriculture, a finding consistent with established archaeological understanding. Wind speed’s contribution was relatively minor, with a dispersed SHAP value distribution, suggesting its role in archaeological site distribution is not prominent, though it might interact with other features in specific areas to indirectly affect human activities. Soil type and aspect had the lowest contributions, with fairly uniform SHAP value distributions, indicating these features had a weaker influence on model output, although they might interact with land use or terrain conditions in localized areas to affect site distribution.

The SHAP analysis for a representative non-site point (Fig. 11a) revealed that ‘Grassland’ as the land use/land cover type exerted the strongest influence (SHAP value = +0.16), being the primary factor driving its classification as a non-site. This aligns with the current conditions in the Surkhandarya region: extensive, undeveloped grassland areas often lack the environmental foundation to support sustained ancient human activity. Slope and precipitation also exhibit relatively high positive contributions (+0.14 and +0.12), indicating that steeper terrain and higher rainfall are treated in the model as environmental conditions unfavourable to site formation or preservation. This pattern may be attributed to geomorphological and hydrological processes: steep slopes hinder the construction and long-term stability of settlements, while excessive precipitation may accelerate the erosion and removal of cultural deposits. By contrast, distance to rivers, wind speed, soil type, and the topographic wetness index (TWI) exert only minor influence on the prediction of non-site locations, all showing positive contributions. Furthermore, aspect, the multi-scale topographic position index (MS_TPI), and profile curvature play an almost negligible role in non-site prediction, suggesting that micro-topographic factors contribute little to the model’s ability to distinguish non-site points. Overall, the explanatory results for non-site predictions demonstrate that the model primarily relies on macro-scale geomorphological and climatic conditions, while showing limited sensitivity to micro-topographic variables.

(Figure 11b) presents the SHAP contribution analysis for a site point, An annual precipitation of 166 mm also showed a significant positive contribution (+0.19), suggesting that moderate rainfall levels are more favourable for ancient human settlement and agriculture. The clay soil type had the SHAP value (+0.14), indicating that clay soil type is a positive environmental factor for predicting site presence. Clay soils often possess high water retention and fertility, beneficial for agricultural production, which was a critical subsistence base for ancient agrarian settlements. A slope of 3.5° likewise contributed positively (+0.1), further corroborating the preference for gently sloping terrain for ease of cultivation and construction, contrasting with the negative effect of steeper slopes observed for the non-site point. ‘Grassland’ as LULC in the site point context had a SHAP value of −0.2, representing a strong negative contribution. This starkly contrasts with the strong positive contribution of grassland (+0.16) for the non-site point in Fig. 11a, collectively indicating that grassland cover is a negative indicator for site presence in this study, almost acting as an “exclusionary feature” for site distribution. Other factors, such as the topographic wetness index (TWI), wind speed, and distance to rivers, all show positive contributions, indicating that moisture availability, climatic conditions, and proximity to water sources remain important environmental determinants of site distribution. By contrast, profile curvature contributes only slightly in a negative direction (–0.01), while the effects of aspect and the topographic position index remain minimal. Overall, the explanatory results for site locations suggest that macro-environmental variables play a central role in the model, although certain micro-topographic conditions may influence the visibility and preservation of sites at local scales.

Comparing the SHAP analyses for the non-site (Fig. 11a) and site (Fig. 11b) points provides deeper insights into the environmental selection logic for archaeological site distribution in the Surkhandarya region. LULC is a primary driver in the distribution of archaeological sites, as it captures the imprint of past human activity, reflecting both the degree of landscape modification and the perceived utility of the landform for ancient inhabitants. Slope, as an important topographical factor, showed opposing influences for site versus non-site points: gentle terrain is a positive indicator for sites, while steep terrain correlates with non-sites. The impact of precipitation is also noteworthy, with moderate levels positively influencing site formation. The influence of distance to river proximity was not prominent in either case, potentially suggesting diverse water procurement strategies in the study area, It might also imply that sites are not strictly linearly distributed along riverbanks but rather within an optimal distance range, or that the precision and type of river data (e.g., differentiating perennial from seasonal rivers) require further refinement. Factors such as TWI, MS TPI, wind speed, aspect, and profile curvature, while reflected in the model, had relatively low overall contributions, possibly indicating they are secondary influencing factors or their effects are more complex and require consideration in conjunction with other variables.

This study addressed a critical challenge in archaeological predictive modelling related to spatial site distribution: the significant impact of sample quality on model efficacy and its constraining effect on the practical utility for archaeological survey. We systematically evaluated the performance of five commonly used machine learning models—Random Forest, K-Nearest Neighbours, Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine, and XGBoost—in archaeological prediction, with a particular focus on investigating the influence of a Kernel Density (KD) based negative sample optimization strategy on these models. Based on the experimental results and analyses, the following main conclusions are drawn: Firstly, a novel kernel density-based negative sample optimization strategy was proposed. Application of this strategy resulted in AUC value improvements for RF, KNN, XGBoost, SVM, and LR models by 11.4%, 11.4%, 8.7%, 15.2%, and 13.6%, respectively, with an average increase in overall Accuracy of approximately 12.1%. These results demonstrate the strategy’s strong robustness and wide applicability across various machine learning models, effectively enhancing data quality and thereby augmenting model generalization capabilities. Secondly, the study identified the machine learning model with optimal performance for archaeological site prediction. Although Logistic Regression has been widely employed in previous research due to its algorithmic simplicity, ease of implementation, and inherent interpretability, our findings clearly indicate that ensemble learning models significantly outperform single models in predictive accuracy when handling complex archaeological geospatial data. The Random Forest model exhibited the best stability and predictive performance in this research; its AUC value increased from 0.844 to 0.958 after applying the negative sample optimization strategy, validating its superiority in constructing high-precision archaeological prediction models. Thirdly, an interpretable methodology based on global and individual drivers of ancient human environmental dependency was introduced. Through the SHAP interpretability method, the contributions of various environmental factors to the predictive model construction for the Kushan period in the Surkhandarya Basin were quantified. The analysis revealed that Land Use/Land Cover (LULC), Slope, and Precipitation were the primary environmental drivers influencing ancient human settlement choices during this period. This SHAP-based analysis not only provides explanations from a holistic perspective down to individual sample predictions but also deepens the understanding of human-environment dependency relationships in specific historical contexts. In summary, this research not only validates the pivotal role of negative sample optimization strategies in enhancing archaeological prediction model performance but also compares the suitability of different machine learning algorithms and leverages the SHAP method to improve model interpretability. The integrated archaeological prediction framework proposed herein—amalgamating negative sample optimization, advanced machine learning algorithms, and interpretability analysis—is poised to offer archaeologists novel approaches and data-driven decision support for more precise and efficient site prediction, thereby better serving the discovery and preservation of cultural heritage.

While Archaeological Predictive Models (APMs) have made significant strides in enhancing the precision of site discovery and localization, several areas warrant further improvement. Firstly, the primary constraint on analyzing fine-scale settlement influences is the quality and resolution of the underlying Digital Elevation Model (DEM). This data limitation precluded a detailed and reliable study of fine-scale surface roughness72. Consequently, the environmental parameters utilized by the model are restricted to a macro-scale, which risks failing to resolve the more granular or dynamic factors central to early human settlement decisions. Secondly, the present study primarily focuses on kernel density (KD) as a geostatistical method. Although KD demonstrates satisfactory performance in the current case study, the field of geostatistics offers a range of well-established approaches for spatial sampling and optimization, such as regression kriging and median distance sampling. Each of these methods has its own theoretical advantages and may yield markedly different results depending on the geographical setting and the spatial distribution of archaeological sites. However, this study has not yet undertaken systematic comparative experiments across these approaches. Thirdly, the modern land use/land cover (LULC) data and climatic variables employed in this study (e.g., annual precipitation and accumulated temperature) primarily reflect contemporary environmental patterns and long-term climate trends. While they serve as meaningful proxy variables for predicting site location, they cannot precisely reconstruct the instantaneous and fine-grained environmental conditions of past periods, especially during times of intensive human activity. This “temporal lag” effect may introduce noise, thereby limiting the model’s ability to accurately infer the strategies underlying ancient human settlement choices. Future research is directed toward addressing the current model’s limitations through the integration of multi-proxy datasets and detailed palaeoclimatic reconstructions. Specifically, variables approximating past realities will be generated by introducing high-resolution records, such as pollen analyses, stable isotope data from lake sediments, and historical documentary evidence of climatic anomalies. The direct incorporation of this palaeo-environmental data into model computation is expected to achieve greater accuracy in the reconstructions of the ecological context underpinning ancient human subsistence and activity. Furthermore, the future availability of high-resolution Digital Elevation Models, particularly those derived from airborne LiDAR, will enable a more detailed investigation of geomorphometric derivatives in archaeological modelling. The rigorous selection and application of more sophisticated fine-scale surface roughness indices is identified as a key area for further exploration.

Data availability

The data and materials used in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Cacciari, I., Pocobelli, G. F. Machine learning: A novel tool for archaeology. Handb. Cult. Herit. Anal. [Internet]. Springer, Cham; p. 961–1002 (2022).

Luo, L., Wang, X., Guo, H., Jia, X. & Fan, A. Earth observation in archaeology: A brief review. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 116, 103169 (2023).

Zhen, Q. Exploring the early anthropocene: Implications from the long-term human–climate interactions in early China. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 21, 133–133 (2021).

Lloyd, C. D., Atkinson, P. M. Archaeology and geostatistics. J Archaeol Sci. Acad. Press. 31,151–65 (2004).

Löwenborg, D. Using geographically weighted regression to predict site representativity. Mak Hist Interactive, Proceedings CAA Conf 37th Annu Meet. Williamsburg, Virginia. p. 203--215 (2009).

Matyukira, C., Mhangara, P. Advancement in the application of geospatial technology in archaeology and cultural heritage in south africa: A scientometric review. Remote Sens. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. 15, 4781 (2023).

Kvamme, K. Computer processing techniques for regional modeling of archaeological site locations (1983).

Kvamme, K. L. One-sample tests in regional archaeological analysis: New possibilities through computer technology. Am. Antiq. 55, 367–381 (1990).

Kvamme, K. L. A predictive site location model on the high plains: An example with an independent test. Plains Anthropol. Routledge (1992).

Vanacker, V. et al. Using Monte Carlo simulation for the environmental analysis of small archaeologic datasets, with the mesolithic in northeast Belgium as a case study. J. Archaeol. Sci. 28, 661–669 (2001).

Bauer, A., Nicoll, K., Park, L. & Matney, T. Archaeological site distribution by geomorphic setting in the southern lower Cuyahoga River Valley, northeastern Ohio: Initial observations from a GIS database. Geoarchaeology 19, 711–729 (2004).

Finke, P. A., Meylemans, E. & Van De Wauw, J. Mapping the possible occurrence of archaeological sites by Bayesian inference. J. Archaeol. Sci. 35, 2786–2796 (2008).

Jarosław, J. & Hildebrandt-Radke, I. Using multivariate statistics and fuzzy logic system to analyse settlement preferences in lowland areas of the temperate zone: an example from the Polish Lowlands. J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 2096–2107 (2009).

Verhagen, P. & Whitley, T. G. Integrating Archaeological Theory and Predictive Modeling: a Live Report from the Scene. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 19, 49–100 (2012).

Balla, A., Pavlogeorgatos, G., Tsiafakis, D. & Pavlidis, G. Modelling archaeological and geospatial information for burial site prediction, identification and management. Int J. Herit. Digit Era 2, 585–609 (2013).

Balla, A., Pavlogeorgatos, G., Tsiafakis, D. & Pavlidis, G. Recent advances in archaeological predictive modeling for archeological research and cultural heritage management. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 14, 143–143 (2014).

Li, L., Nahayo, L., Habiyaremye, G. & Christophe, M. Applicability and performance of statistical index, certain factor and frequency ratio models in mapping landslides susceptibility in Rwanda. GEOCARTO Int. 37, 638–656 (2022).

Wang, Y., Fang, Z., Hong, H., Costache, R. & Tang, X. Flood susceptibility mapping by integrating frequency ratio and index of entropy with multilayer perceptron and classification and regression tree. J. Environ. Manag. 289, 112449 (2021).

Ozdemir, A. GIS-based groundwater spring potential mapping in the Sultan Mountains (Konya, Turkey) using frequency ratio, weights of evidence and logistic regression methods and their comparison. J. Hydrol. 411, 290–308 (2011).

Phillips, S. J., Anderson, R. P., Dudik, M., Schapire, R. E., Blair, M. E. Opening the black box: An open-source release of maxent. ECOGRAPHY. Hoboken: Wiley. 40, 887–93 (2017),

Fourcade Y., Besnard A. G., Secondi J. Paintings predict the distribution of species, or the challenge of selecting environmental predictors and evaluation statistics. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. Hoboken: Wiley 27, 245–56 (2018).

Tonini, M. An Explorative Application of Random Forest Algorithm for Archaeological Predictive Modeling. A Swiss Case Study. J. Comput. Appl. Archaeol. 4, 110–125 (2021).

Noviello, M., Cafarelli, B., Calculli, C., Sarris, A. & Mairota, P. Investigating the distribution of archaeological sites: Multiparametric vs probability models and potentials for remote sensing data. Appl. Geogr. 95, 34–44 (2018).

Wachtel, I., Zidon, R., Garti, S. & Shelach-Lavi, G. Predictive modeling for archaeological site locations: Comparing logistic regression and maximal entropy in north Israel and north-east China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 92, 28–36 (2018).

Luo, L., Wang, X. & Guo, H. Transitioning from remote sensing archaeology to space archaeology: Towards a paradigm shift. Remote Sens Environ. 308, 114200 (2024).

Luo, L., Wang, X., Guo, H. Remote sensing archaeology: The next century. The Innovation. Elsevier. 3 (2022).

Wang, S., Han, W., Zhang, X., Li, J. & Wang, L. Geospatial remote sensing interpretation: From perception to cognition. Innov. Geosci. Innov. Geosci. 2, 100056 (2024).

Nsanziyera, A. F. et al. Remote-sensing data-based Archaeological Predictive Model (APM) for archaeological site mapping in the desert area, South Morocco. Comptes Rendus Géosci. 350, 319–330 (2018).

Cuthbertson, P. et al. Finding karstic caves and rockshelters in the Inner Asian mountain corridor using predictive modelling and field survey. PLOS One Public Libr. Sci. 16, e0245170 (2021).

Li, L., Li, Y., Chen, X., Sun, D. A Prediction Study on Archaeological Sites Based on Geographical Variables and Logistic Regression—A Case Study of the Neolithic Era and the Bronze Age of Xiangyang. Sustainability. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. 14, 15675 (2022).

Carleton, W. C., Conolly, J. & Ianonne, G. A locally-adaptive model of archaeological potential (LAMAP). J. Archaeol. Sci. 39, 3371–3385 (2012).

Wang, Y., Shi, X., Oguchi, T. Archaeological Predictive Modeling Using Machine Learning and Statistical Methods for Japan and China. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. 12, 238 (2023).

Brouwer Burg, M., Peeters, H., Lovis, W. A., editors. Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis in archaeological computational modeling [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing. (2016).

Graves, D. The use of predictive modelling to target Neolithic settlement and occupation activity in mainland Scotland. J. Archaeol. Sci. 38, 633–656 (2011).

Yan, L. et al. Towards an Operative Predictive Model for the Songshan Area during the Yangshao Period. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. 10, 217. (2021).

Kempf, M. The application of GIS and satellite imagery in archaeological land-use reconstruction: A predictive model?. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 25, 116–128 (2019).

Yang H. et al. Predicting ancient city sites using GEE coupled with geographic element features and temporal spectral features: A case study of the Neolithic and Bronze Age of the Jianghan region, China. Npj Herit. Sci. Nature Publishing Group. 13, 1–15 (2025).

Klehm, C. et al. Toward archaeological predictive modeling in the Bosutswe region of Botswana: Utilizing multispectral satellite imagery to conceptualize ancient landscapes. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 54, 68–83 (2019).

Cui, J. Mapping landscape in Longshan period’s hierarchical society (3000–2000BCE) of North Loess Plateau: from archaeological predictive model to GIS spatial analysis. Herit. Sci. 12, 78 (2024).

Flores-Aqueveque, V. et al. Machine learning-based identification of geomorphological units in Quintero Bay (32°S) and its implications for the search for early drowned archaeological sites on the western coast of South America. Quat. Int 712, 109585 (2024).

Zhu, X., Chen, F., Guo, H. A Spatial Pattern Analysis of Frontier Passes in China’s Northern Silk Road Region Using a Scale Optimization BLR Archaeological Predictive Model. Heritage. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute 1, 15–32 (2018).

Chefaoui, R. M. & Lobo, J. M. Assessing the effects of pseudo-absences on predictive distribution model performance. Ecol. Model. 210, 478–486 (2008).

Vojteková, J. et al. Prediction of potential occurrence of historical objects with defensive function in Slovakia using machine learning approach. Sci Rep. Nature Publishing Group. 14, 30350 (2024).

Li, G. et al. GIS and machine learning models target dynamic settlement patterns and their driving mechanisms from the Neolithic to Bronze Age in the northeastern Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. 16, 1454 (2024).

Li, C., et al. Interpretable foundation models as decryptors peering into the Earth system. The Innovation. Elsevier. 5, (2024).

Różkowski, J., Rzętała, M. Uzbekistan’s aquatic environment and water management as an area of interest for hydrology and thematic tourism. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. ASERS Ltd. 12, 642–53 (2021).

TANG Yun-peng, W. A. N. G. J. ian-xin The Main Results of Archaeological Work in the Surkhandarya Basin, Uzbekistan: Archaeolgical Observation of Yuezhi and Kushan Culture. J. Northwest Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 51, 80–92 (2021).

Takaku, J., Tadono, T., Tsutsui, K. Generation of high resolution global DSM from ALOS PRISM. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. Copernicus GmbH XL–4, 243–8 (2014).

Yokoyama, R., Shirasawa, M. & Pike, R. J. Visualizing topography by openness:A new application of image processing to digital elevation models. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 68, 257–266 (2002).

Guisan, A., Weiss, S. B. & Weiss, A. D. GLM versus CCA spatial modeling of plant species distribution. Plant Ecol. 143, 107–122 (1999).

Riley, S. J., DeGloria, S. D., Elliot, R. A Terrain Reggedness Index that Quantifies Topographic Heterogeneity. Intermt. J. Sci. 5–5. (1999).

Feng, Z., Yang, Y., Zhang, D. & Tang, Y. Natural environment suitability for human settlements in China based on GIS. J. Geogr. Sci. 19, 437–446 (2009).

Moore, I. D., Grayson, R. B. & Ladson, A. R. Digital terrain modelling: A review of hydrological, geomorphological, and biological applications. Hydrol. Process 5, 3–30 (1991).

Cheng, H. et al. Climate variations of central Asia on orbital to millennial timescales. Sci. Rep. Nature Publishing Group. 6, 36975. (2016).

Wu, H., Wang, X., Wang, X., Zhang, L. & Dong, S. Predictive modeling for neolithic settlements in the Lingnan Region, South China. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 49, 103992 (2023).

Oonk, S., Spijker, J. A supervised machine-learning approach towards geochemical predictive modelling in archaeology. J. Archaeol. Sci. Academic Press. 59, 80–88 (2015).

Elliot, T., Morse, R., Smythe, D., Norris, A. Evaluating machine learning techniques for archaeological lithic sourcing: A case study of flint in Britain. Sci Rep. Nature Publishing Group. 11, 10197 (2021).

Iban, M. C., Sekertekin, A. Machine learning based wildfire susceptibility mapping using remotely sensed fire data and GIS: A case study of Adana and Mersin provinces, Turkey. Ecol Inform. Amsterdam: Elsevier. 69, 101647 (2022).

Hong, H., Liu, J. & Zhu, A.-X. Modeling landslide susceptibility using LogitBoost alternating decision trees and forest by penalizing attributes with the bagging ensemble. Sci. Total Environ. 718, 137231 (2020).

Tian, Y. et al. Evolution of influence ranges of Neolithic-Bronze Age cities in the Songshan Mountain region of central China based on GIS spatial analysis. REMOTE Sens. 14, (2022).

Comer, J. A., Comer, D. C., Dumitru, I. A., Priebe, C. E. & Patsolic, J. L. Sampling methods for archaeological predictive modeling: Spatial autocorrelation and model performance. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 48, 103824 (2023).

Zhao, F. et al. Refined landslide susceptibility mapping in township area using ensemble machine learning method under dataset replenishment strategy. Gondwana Res. 131, 20–37 (2024).

Lan, X. et al. Prediction of the potential distribution and preservation of archaeological wooden artifacts in Yangzhou City, China. J. Cult. Herit. 71, 346–357 (2025).

Castiello, M. E. Computational and machine learning tools for archaeological site modeling [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing. (2022).

Wang, C. et al. The influences of the spatial extent selection for non-landslide samples on statistical-based landslide susceptibility modelling: A case study of Anhui province in China. Nat. Hazards 112, 1967–1988 (2022).

Hong, H., Wang, D., Zhu, A.-X. & Wang, Y. Landslide susceptibility mapping based on the reliability of landslide and non-landslide sample. Expert Syst. Appl. 243, 122933 (2024).

Yang, S. et al. Sample size effects on landslide susceptibility models: A comparative study of heuristic, statistical, machine learning, deep learning and ensemble learning models with SHAP analysis. Comput Geosci. 193, 105723 (2024).

Dou, H., He, J., Huang, S., Jian, W., Guo, C. Influences of non-landslide sample selection strategies on landslide susceptibility mapping by machine learning. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk. Taylor & Francis. 14, 2285719 (2023).

Jochim, M. A. Dots on the Map: Issues in the Archaeological Analysis of Site Locations. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 30, 876–894 (2023).

Yaworsky, P. M., Vernon, K. B., Spangler, J. D., Brewer, S. C., Codding B. F. Advancing predictive modeling in archaeology: An evaluation of regression and machine learning methods on the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Lozano S, editor. PLOS ONE. Public Library of Science. 15, e0239424 (2020).

Mihu-Pintilie, A., Nicu, I. C. GIS-based Landform Classification of Eneolithic Archaeological Sites in the Plateau-plain Transition Zone (NE Romania): Habitation Practices vs. Flood Hazard Perception. Remote Sens. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. 11, 915 (2019).

Trevisani, S., Teza, G. & Guth, P. L. Hacking the topographic ruggedness index. Geomorphology 439, 108838 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Construction of the China-Central Asia Human and Environment "Belt and Road" Joint Laboratory and Joint Research on Ancient Human Culture and Environment in the Sulh River Basin: [Grant number 2022YFE0203800], National Natural Science Foundation of China: [Grant number 42471370], The Archaeological Talent Promotion Program of China [Grant number 2024-267], The Youth Innovation Promotion Association of CAS: [Grant number 2023135].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used: “Conceptualization, L.L., J.Y.; methodology, J.Y.; software, J.F.; validation, R.T., L.L.and X.F.; formal analysis, J.Y.; investigation, J.Y.; resources, J.Z.; data curation, D.J., X.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.Z., L.L. and X.W.; visualization, J.S., R.T.; supervision, L.L.; project administration, L.L.; funding acquisition, X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript”.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., Luo, L., Zhao, J. et al. Explainable artificial intelligence with negative sample optimization for archaeological site prediction in Surkhandarya Uzbekistan. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 689 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02267-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02267-9