Abstract

Identifying ancient textile fibers is crucial for conservation and reflects ancient subsistence and economic practices. This study investigates fiber and textile fragments from two neighboring turquoise mining sites in the Hexi Corridor, dating to the Early Western Zhou and Spring and Autumn periods. Using ultra-depth-of-field microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS), and attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy, we found morphological analysis alone insufficient for identification. Fourier self-deconvolution and Gaussian-fitting of spectral data revealed consistent protein secondary structures, while mass spectrometry confirmed identical primary structures, indicating that fibers from both sites belong to the same wool species. The presence of sheep wool textiles demonstrates continuity in animal fiber use across different periods, offering material evidence of pastoral economies and stable technological support for early turquoise mining in the Hexi Corridor, highlighting regional technological interactions before the Silk Road.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ancient Silk Road, a key conduit for trade and cultural exchange between the East and West, significantly advanced human civilization and societal development. The Hexi Corridor in the northwest region of China is a crucial conduit for material and cultural exchanges along the Silk Road1. The arid, temperate continental climate of the region has preserved numerous organic relics, which offer invaluable materials for research2,3,4,5. Among these relics, a notable collection of textiles has been uncovered through archaeological excavations6. These textiles, characterized by unique weaving techniques and vibrant colors, reflect advanced textile technology and cultural context, providing insights into ancient climate and agricultural practices through variations in raw materials7,8. Analyzing ancient textiles and their raw materials is thus pivotal to understanding historical contexts, and also providing invaluable insights into the degradation of natural organic materials.

Modern analytical techniques provide feasible approaches for the analysis of ancient textiles9,10,11. Wang et al. used morphological analysis to identify fibers from an early 20th-century waistcoat as bamboo and cotton, based on their longitudinal and surface characteristics12. Li et al. employed fiber slicing to identify animal hair from the Shanpula Cemetery in Xinjiang6. Morphological observation is commonly used for fiber identification but has limitations with degraded fibers13. This is particularly true for morphological similar fibers that have undergone degradation, as they are difficult to distinguish14. Therefore, it is necessary to obtain further information on the fibers through molecular structure characterization.

By exploiting the crystallinity of organic fiber molecules and using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) to study crystallization kinetics, different types of animal fibers can be distinguished15,16,17. The crystalline structure in natural fibers can also be analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) for identification18. However, these techniques require fiber extraction, which can cause irreversible damage to archaeological samples19.

For fragile organic fibers recovered from archaeological sites, non-destructive or minimally invasive analytical techniques that maximize the information obtained are of critical importance20,21. Mass spectrometry (MS), a fingerprinting analytical technique, provides high accuracy with minimal sample requirements22. For instance, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with MS enabled the extraction and successful identification of insect- and plant-derived dyes from a single textile fiber excavated in Bazhou, Xinjiang, Furthermore, optimized MS protocols permit analysis of trace fibers (<1 mg)23. Moreover, in cases where fiber extraction is not feasible, non-destructive spectroscopic analysis proves more advantageous24.

Portable non-destructive spectroscopy successfully distinguishes between different types of natural textile fibers, offering a practical approach for classifying archaeological textiles25. Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy is particularly suitable for analyzing organic cultural relics26. This technique non-destructively identified ramie fibers in textile residues from Qin Shihuang’s Terra-Cotta Warriors17. Due to the infrared sensitivity of organic materials, mid-infrared spectroscopy also probes secondary structures of protein molecules. Akada et al. applied Gaussian fitting and peak separation to spectral data, identifying peak positions associated with specific secondary structure arrangements in aged silk protein. This established a foundation for spectroscopic studies of ancient silk textiles27. Similarly, Chiaramaria et al. correlated infrared spectral peak variations with molecular chain conformations in protein-based fibers, advancing molecular-level spectroscopic interpretation28. Our team further demonstrated that red and blue dyes accelerate fiber aging in dyed fibers from ancient mining areas through molecular structure analysis29. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that infrared spectroscopy technology can rapidly and effectively extract molecular structural information from ancient textiles.

Based on prior excavations at the ancient turquoise mining site of Heishanling, Xinjiang, a newly discovered early turquoise mining site has recently been identified in the adjacent Hami region. Notably, both sites are situated in areas characterized today by an extremely harsh climate, marked by year-round aridity and intense heat, resulting in impoverished flora and fauna resources. Remarkably, however, ancient peoples conducted both production and habitation activities in this location30,31,32. Therefore, the study of archaeological remains in this region contributes significantly to revealing the subsistence patterns of past populations. In this study, several textile fragments from the two sites were selected for analysis. The morphology was characterized using scanning electron microscope (SEM) and optical microscope (OM). The analysis employed mid-infrared ATR spectroscopy combined with Fourier self-deconvolution (FSD) and Gaussian fitting to investigate the molecular structure of ancient fibers. Mass spectrometry further confirmed these findings at the primary structure level. Through these multi-scale analyses, we identified the sources of organic fibers, thereby providing key material evidence for reconstructing the animal resource utilization that supported these early mining communities.

Methods

Sample preparation

Seven archaeological samples were obtained from two early ancient turquoise mining sites in southern Xinjiang, China. Adjacent to Lop Nur, these sites experience an extremely arid climate with minimal rainfall, resulting in severe desertification and the formation of gravel deserts (Gobi). This same aridity has also resulted in the exceptional preservation of organic artifacts.

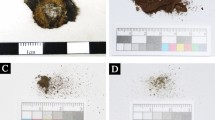

Figure 1 shows the geographical distribution of the sites and sample photographs. One site, named Tianhudong, is located in Ha-mi and was dated to 3020-2380 years ago32. Since archaeological excavations began in 2023, three ancient animal hair samples were recovered from layer T12① in the western sector of the site. These samples, designated T1, T2, and T3, were found in association with other artifacts including a painted pottery jar and a turquoise bead ornament (see Supplementary material 1.1 for excavation photographs and artifact images).

The other site, named Heishanling, is situated at the eastern terminus of the Heishanling mountains in Luobunao’er Township, Ruoqiang County, adjacent to the border of Ha-mi City and the Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture. Excavations since 2018 have yielded leather artifacts, animal bones, bronze ware and spinning implements, and textiles. Typological analysis of these artifacts, combined with radiocarbon dating of osteological remains, indicates that the site was occupied approximately between 2695 and 2390 years ago31. Preliminary morphological classification of textiles collected from the K16II excavation unit led to the identification of four fragments exhibiting clearly visible yellowish-brown fibrous structures, which were designated as H1, H2, H3, and H4, respectively. (Detailed archaeological context and photographs of associated artifacts are provided in the Supplementary material Section 1).

Morphological observation

All samples were examined using ultra-depth-of-field microscopy (ZEISS Smartzoom 5) to analyze fiber morphology. For cross-sectional observation, partially detached fibers were bundled, wrapped with yarn, and sectioned using a Hacker rotary microtome. The sections were placed section-side up on a glass slide with a drop of paraffin oil, and then flattened under a cover glass for observation.

The longitudinal and surface morphology of the fibers were characterized using a TESCAN Vega-3 scanning electron microscope (SEM) at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV.

FT-IR spectroscopy analysis

Infrared spectra of the original fibers were acquired using a Bruker LUMOS FT-IR microscope equipped with a germanium ATR crystal accessory. The instrument permitted direct, non-destructive analysis of both animal hairs and textile fragments without sample preparation. The spectra were collected after ATR-correction using an instrument equipped with a ZnSe beam splitter, a signal acquisition window accessory, and a deuterated triglycine sulfate (DTGS) detector. The ATR crystal was cleaned with ethanol and optical cleaning paper before each analysis. The spectra were recorded by averaging 32 scans at a resolution of 4 cm-1 over the range of 600 cm-1 to 4000 cm-1. Two points were tested for each sample to obtain an average spectrum for analysis.

The acquired spectra were automatically baseline-corrected and processed by Fourier self-deconvolution (FSD) using Omnic software. Subsequent second-derivative analysis was performed in Origin software to identify the initial positions of constituent peaks based on their negative spectral features. These positions served as inputs for Gaussian curve fitting within the same software. The fitting procedure was iteratively refined until convergence was achieved, resulting in clear separation of overlapping bands. The resolved sub-peaks were assigned to specific secondary structures, and their relative percentages were quantified based on their integrated area.

Protein extraction and MALDI-TOF mass analysis

Approximately 1 mg of detached fiber per sample underwent sequential processing: initial rinsing with deionized water followed by drying, alkylation in a 50 μL mixed solution (10 mM tris (2-carboxyethyl)phosphine/40 mM 2-chloroacetamide) at 99 °C for 20 min, followed by protein extraction in 0.1 M ammonium hydrogen carbonate (NH₄HCO₃). Finally, the proteins were enzymatically digested with 0.5 μg sequencing-grade trypsin (Promega) in 50 mM NH₄HCO₃ buffer at 37 °C for 18 h. The resulting digestates were purified using C18 solid-phase extraction columns, mixed with α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) matrix solution at a 1:1 volume ratio, and spotted (1 μl) onto a stainless steel MALDI target plate. Spectra were acquired after solution crystallization.

Mass analysis was performed on a Bruker autoflex max MALDI-TOF-MS spectrometer in positive ion reflector mode. Spectra were acquired by accumulating 1000 laser shots across a mass range of 800–4000 Da.

Raw spectral data were processed using the integrated FlexAnalysis software (Bruker Daltonics). The raw spectra were subjected to baseline correction, smoothing, and noise reduction, followed by peak picking to generate a list of monoisotopic masses. This peak list was exported to the Mascot search engine (version 2.8) for a Peptide Mass Fingerprint (PMF) search against the SwissProt database, with the taxonomy restricted to Mammalia. The search parameters were set as follows: fixed modification of carbamidomethyl (C); variable modification of oxidation (M); one missed cleavage allowed; mass values set as monoisotopic; and a peptide mass tolerance of ± 50 ppm. Protein identifications were considered statistically significant at a confidence threshold of p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Morphological analysis

The surface morphology and textile weaving structures of the seven samples were examined using an optical microscope, as shown in Fig. 2. Fibers from the Tianhu Dong site (T1, T2 and T3) exhibited brown and yellow hues with a characteristic luster, indicating an animal hair origin for all samples. Furthermore, the twisting of fibers into Z-plied yarns was clearly visible in the four textile fragments.

Relevant studies confirm that taxonomic identification of animal species is achievable through morphological analysis of hair cross-sections and scale patterns33,34. To analyze sample morphology in detail, fiber cross-sections were observed, and the results are shown in Fig. 3. The cross-sections predominantly exhibited elliptical profiles, with occasional dumbbell-shaped variants. Furthermore, fine-diameter fibers, as represented by samples H3 and H4, were found to lack a medulla entirely. Additionally, fibers with slightly larger diameters (T1, T2, H1) exhibited a thicker cortex and occasionally contained small medullary structures. Notably, distinct medulla formations were observed in the coarse-diameter fibers of samples T3 and H3. Based on these morphological characteristics observed in the cross-sections, the presence of fibers with varying diameters twisted together suggests that they may originate either from the hair of different animal species, or from the same species at different growth stages.

SEM micrographs of fiber longitudinal surfaces are presented in Fig. 4. Morphometric analysis suggested a probable wool origin for the fibers, as these structural features are consistent with published research on archaeological textiles excavated from Xinjiang-associated sites22,35.

Notably, SEM micrographs of textile fragments from Heishanling revealed pronounced scale exfoliation, with complete scale layer degradation observed in several fibers. In contrast, animal hair fibers of T1, T2 and T3 from the chronologically earlier Tianhudong site exhibited intact scale structures. This differential state of degradation can likely be attributed to the combination of ancient weaving processes and variations in the micro-depositional burial environments.

ATR-FTIR spectroscopic analysis

The molecular structure of the organic samples was further investigated by FTIR spectroscopy. Figure 5 presents the full-range spectrum (a) and the corresponding fingerprint region (b). The high-frequency region from 4000 cm-1 to 800 cm-1 corresponds to the functional group region, reflecting the characteristic vibrations of various functional groups present in the fibers. The band observed between 3600 cm-1 and 3500 cm-1 can be assigned to free O-H stretching vibrations. However, due to extensive hydrogen bonding between molecular chains, the O-H vibration shifts to lower wavenumbers and overlaps with the N-H stretching mode, resulting in a broad absorption band centered at 3288 cm-1. This feature is known as the amide A band36. The absorption peaks between 2900 cm-1-2800 cm-1 are characteristic of C-H stretching vibrations in -CH3 and -CH2- groups. The presence of strong amide bands (I, II, and III) between 1700 cm-1 and 1200 cm-1 confirms the proteinaceous nature of the fibers, which is consistent with the morphological observations37. Furthermore, a strong characteristic peak at 1035 cm-1 is assigned to S = O stretching vibrations. This suggests the photo-oxidation of disulfide (S-S) bonds in keratin during long-term burial. Given their relatively low bond dissociation energy (263.71 kJ/mol), S-S bonds are prone to cleavage, forming sulfhydryl groups (S-H) that are subsequently oxidized to sulfoxide (S = O) structures38.

The spectral region between 800 cm-1 and 600 cm-1 contains rich vibrational information highly sensitive to molecular structure. However, the characteristic peaks are difficult to identify in the raw spectra due to significant band overlap and complexity, as depicted by the dotted lines in Fig. 5b. To address this, the FSD method was applied, which effectively resolved the closely overlapping infrared bands typical of condensed-phase samples39. The FSD-processed curves, shown by the solid lines in Fig. 5b, reveal the peak at 606 cm-1 is attributed to out-of-plane bending vibrations. The range from 690 cm-1 to 600 cm-1 is primarily associated with bending vibrations of O-C-N bonds40. The region between 800 cm-1 and 640 cm-1 exhibits contributions from out-of-plane bending of protein amide N-H groups, though these signals are often intertwined with other vibrational modes. Importantly, the high spectral consistency observed across all FSD-processed samples suggests a common underlying chemical structure.

The amide I band is pivotal in the infrared spectroscopic analysis of proteins, as it provides critical information on the stretching vibrations of the protein backbone carbonyl group (C = O) and reflects the secondary structure of protein macromolecules. This band, comprising approximately 80% carbonyl group (C = O) stretching and 20% C-N stretching and N-H bending vibrations28,40,41, typically exhibits characteristic absorption between 1750 cm-1 and 1600 cm-1.

To analyze the protein secondary structures in the ancient samples, the fourth-derivative spectrum and its Gaussian fitting results for the amide I band are presented in Fig. 6. The original and fitted spectra are represented by the colored solid lines and black dashed lines, respectively. Analysis of the fourth-derivative spectra reveals 11 absorption peaks, including shoulder and narrow bands, which display a high degree of similarity across all samples. The peak fitting assigned these features to specific secondary structures: peaks between 1713 cm-1 and 1667 cm-1 were attributed to β-turns42; components from 1661 cm-1 to 1649 cm-1 correspond to the α-helix27, peaks in the range of 1635 cm-1 to 1621 cm-1 indicate random coils; and those between 1610 cm-1 to 1590 cm-1 are characteristic of β-sheets43. Quantitative analysis based on the integrated areas of the fitted peaks reveals that the α-helix and random coils constitute the most prominent components, followed by β-turns, with β-sheets exhibiting the lowest intensity (more details for curve-fitting and results, see the Supplementary material).

The amide II band, originating from the coupling of N-H bending and C-N stretching vibrations, was observed within the range of 1470 cm−1 to 1570 cm−127. Figure 7 displays the fourth-derivative spectrum along with its Gaussian fit, where the original and fitted spectra are represented by colored and black lines, respectively.

Six constituent peaks were resolved in the fourth-derivative spectra, all exhibiting similar intensity profiles across the samples. The assignment of these peaks (Table S1) reveals that β-sheet structures were the least abundant, followed by β-turns, whereas α-helix and random coils represented the dominant and comparable components44,45,46. This consistency in spectral features indicates a nearly identical local environment for the associated molecular vibrations, confirming a high degree of similarity in the protein secondary structures among all samples.

The amide III band is highly sensitive to changes in protein secondary structure. It primarily arises from the coupling of C-N stretching and N-H bending vibrations, and is also influenced by C-C stretching and C-H bending modes. Although its intensity is weaker than that of the amide I and amide II bands, a clear peak profile for the amide III region was achieved after fourth-derivative processing, as shown in the corresponding spectral fitting, performed in the range starting from 1210 cm⁻¹, identified constituent peaks that were assigned to α-helix, random coil, β-turn, and β-sheet structures.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis

Figure 9 presents the MALDI-TOF mass spectra of the modern wool fibers and the seven archaeological samples. Where the observed peaks correspond to peptide fragment ions generated by enzymatic digestion and subsequent ionization47. All samples exhibited characteristic peptide ion peaks within the 800-2500 m/z (mass-to-charge ratio) range, consistent with the fragmentation pattern of modern wool keratin. This consistency indicates a common protein composition.

Furthermore, the mass spectrometric signal intensity of modern wool fibers was generally stronger than that of their ancient counterparts; this discrepancy may stem from partial keratin degradation in archaeological specimens over time, which would reduce the yield of peptide fragments. Notably, the ion peak at m/z = 2144 was detected in archaeological fibers with relatively weak intensity but was entirely absent in textile samples. This discrepancy is likely attributed to the combined effects of textile processing and long-term burial at the Heishanling site, which likely prevented the effective detection of this peptide fragment ion.

To unambiguously determine the protein origin, mass spectral data were searched against the SwissProt database using Mascot. The search yielded significant matches, with the highest score of 58 corresponding to keratin type I microfibrillar, component 8C-1 (K1M1_SHEEP) from Ovis aries (expectation value 0.1; 6 matched peptides), providing conclusive evidence for a sheep wool origin. The complete Mascot search summary is provided in Table S2 (Supplementary material).

Table 1 lists the principal peptide ion peaks identified in both archaeological and modern sheep wool spectra. These peaks, validated by Mascot alignment with a modern Ovis aries keratin standard and cross-referenced with existing literature48, were assigned to type I and II keratins. Together, these results provide robust molecular evidence that the textile artifacts from both Tianhudong and Heishanling are of sheep wool origin.

The consistent identification of sheep wool across all samples from both ancient turquoise-mining sites, despite their occupation during distinct historical periods, points to a continuity in animal fiber exploitation strategies among ancient mining communities in the Hexi Corridor. This continuity, considered alongside the archaeological recovery of animal bones and weaving tools at these sites32, strongly suggests that a pastoral-based economy was integral to sustaining long-term turquoise mining activities.

In conclusion, this study established a multi-analytical approach incorporating macroscopic morphology, micro-fingerprinting spectroscopy, and biomolecular analysis for the minimally invasive identification of severely degraded archaeological protein fibers.

The results demonstrate that the organic fibers from both the Tianhudong and Heishanling sites are of faunal origin. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy combined with Gaussian fitting and derivative analysis confirmed their proteinaceous nature and revealed consistent molecular structures across all samples. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry provided definitive biomolecular evidence, identifying all fibers as sheep wool (Ovis aries).

Collectively, the convergence of evidence—including the identification of wool textiles, excavated animal bones, and weaving tools—within turquoise-mining areas indicates a cohesive system of pastoral resource use supporting early mining activities. This strongly suggests that the Hexi Corridor had already functioned as a dynamic zone of technological and material interaction long before the formal establishment of the Silk Road. This work not only establishes a robust scientific protocol for the minimally invasive analysis of ancient protein fibers but also provides molecular-level insights into the subsistence economies and resource strategies of prehistoric communities in northwestern China.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the partial data of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Material. Other original data of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Zhang, F. et al. The genomic origins of the Bronze Age Tarim Basin mummies. Nature 599, 256–261 (2021).

Betts, A. et al. A new hypothesis for early Bronze Age cultural diversity in Xinjiang, China. Archaeol. Res. Asia 17, 204–213 (2019).

Jia, Y. et al. The identification of wool textiles from Zagunlukeand Shanpula tombs (from Western Zhou to Eastern Han) in Xinjiang. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 1, 18–23 (2008).

Guo, D. et al. Research on species and ageing of unearthed silk fibers from Yingpan of Xinjiang. Text. Res. J. 31, 11–14 (2010).

Cork, C. R. et al. Analysis and evaluation of a group of early Roman textiles from Vindolanda, Northumberland. J. Archaeol. Sci. 24, 19–32 (1997).

Li, J. Discussion on the role of fiber embedding and slice method in the study of un-earthed textile taking the textile unearthed in Shanpula as an example. Turfanol. Res. 2, 88–92 (2020).

Benson, L. V., Hattori, E. M. & Taylor, H. E. Isotope sourcing of prehistoric willow and tule textiles recovered from western Great Basin rock shelters and caves—proof of concept. J. Archaeol. Sci. 3, 1588–1599 (2006).

Zhang, Y., Mo, D. & Hu, K. Holocene environmental changes around Xiaohe Cemetery and its effects on human occupation, Xinjiang, China. J. Geogr. Sci. 27, 752–768 (2017).

Madkour, F. A. et al. Performance scanning electron microscopic investigations and elemental analysis of hair of the different animal species for forensic identification. Microsc. Res. Tech. 85, 2152–2161 (2022).

Dallongeville, S. et al. Proteins in art, archaeology, and paleontology: from detection to identification. Chem. Rev. 116, 2–79 (2016).

Brandt, L. Ø, Schmidt, A. L. & Mannering, U. Species identification of archaeological skin objects from Danish Bogs: comparison between mass spectrometry-based peptide sequencing and microscopy-based methods. PLoS ONE 9, e106875 (2014).

Wang, Y., Zhan, L. & Zhou, Y. Technical study on the early twentieth century’s embroidered women waistcoat in Gyalrong Tibetan area in Sichuan, China. Herit. Sci. 12, 166 (2024).

Karpova, E., Vasiliev, V. & Mamatyuk, V. Xiongnu burial complex: a study of ancient textiles from the 22nd Noin-Ula barrow (Mongolia, first century AD). J. Archaeol. Sci. 70, 15–22 (2016).

Zhou, Y., Long, B. & Li, J. Degradation analysis of wool fabrics from Small River Cemetery. Text. Res. J. 35, 67–72 (2014).

Li, J. et al. Ultrasensitive electrochemical immunosensor reveals the existence of silk products on the maritime silk road. ACS Sens. 4, 3203–3209 (2019).

Xuesong, H., Pu, C. & Jingyan, L. Commentary on the review articles of spectroscopy technology combined with chemometrics in the last three years. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 59, 423–482 (2024).

Yang, L., Huang, J. & Shen, M. FTIR spectral and microscope analysis of textile residues on the surface of the bag for storing bows excavated from Qin Shihuang’s Terra Cotta Warriors Museum. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 40, 3623–3627 (2020).

Segal, L., Creely, J. J. & Martin, A. E. An empirical method for estimating the degree of crystallinity of native cellulose using the X-Ray diffractometer. Text. Res. J. 29, 786–794 (1959).

Sarmiento, A., Pérez-Alonso, M. & Olivares, M. Classification and identification of organic binding media in artworks by means of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and principal component analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 399, 3601–3611 (2011).

Riu, J. & Giussani, B. Analytical chemistry meets art: the transformative role of chemometrics in cultural heritage preservation. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 247, 105095 (2024).

You, Q., Li, Q. & Zheng, H. Discerning silk produced by Bombyx mori from those produced by wild species using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay sombined with conventional methods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 65, 7805–7812 (2017).

You, Q., Liu, M. & Liu, Y. Lanthanide-labeled immunochromatographic strip assay for the on-site identification of ancient silk. ACS Sens 2, 569–575 (2017).

Suyun, G. & Narenggaowa, Y. M. Identification of fibers and dyes in archaeological textiles from Bazhou, Xinjiang (220-420 CE), and their Silk Road origins. J. Archaeol. Sci. 164, 105941 (2024).

Serafini, I. et al. Development of a combined protein and dye extraction approach for the analysis of keratin-based textiles. J. Proteome Res. 9, 3890–3903 (2024).

Xuesong, H. et al. Commentary on the review articles of spectroscopy technology combined with chemometrics in the last three years. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 59, 423–482 (2024).

Zhao, H. et al. Spectral reflectance characterization and fiber type discrimination for common natural textile materials using a portable spectroradiometer. J. Archaeol. Sci. 111, 105026 (2019).

Akada, M., Sato, M. & Okuyama, M. Studies on the degraded state of excavated archaeological silk fibers using infrared micro-spectroscopy and curve fitting analysis. Sen- Gakkaishi 65, 262–266 (2009).

Stani, C., Vaccari, L. & Mitri, E. FTIR investigation of the secondary structure of type I collagen: New insight into the amide III band. Spectrochim. Acta A. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 229, 118006 (2020).

Xiao, W. et al. Microinvasive analysis of textile relics from an ancient Silk Road turquoise mining site. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 66, 2286–2296 (2023).

Xian, Y. et al. A method to characterize turquoise deposits in china using sedimentary environment sensitive elements. Herit. Sci. 11, 236 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. A Survey of the ancient turquoise mining site at Heishanling in Ruoqiang, Xinjiang. Cult. Relics 8, 4–13 (2020).

Li, Y., Tan, Y. & Jia, Q. Preliminary investigation of two turquoise mining sites in Hami. Archaeol. Cult. Relics 6, 22–27 (2019).

Madkour, F. A. & Abdelsabour-Khalaf, M. Performance scanning electron microscopic investigations and elemental analysis of hair of the different animal species for forensic identification. Microsc. Res. Tech. 6, 2152–2161 (2022).

Wildman, A. B. The identification of animal fibres. J. Forensic Sci. Soc. 2, 115–119 (1961).

Liu, J. et al. Identification of ancient textiles from Yingpan, Xinjiang, by multiple analytical techniques. J. Archaeol. Sci. 38, 1763–1770 (2011).

Yang, H. et al. Obtaining information about protein secondary structures in aqueous solution using Fourier transform IR spectroscopy. Nat. Protoc. 10, 382–396 (2015).

Kramell, A. et al. Dyes of late Bronze Age textile clothes and accessories from the Yanghai archaeological site, Turfan, China: determination of the fibers, color analysis and dating. Quat. Int. 348, 214–223 (2014).

Jones, D. C., Carr, C. M. & Cooke, W. D. Investigating the photo-oxidation of wool using FT-Raman and FT-IR spectroscopies. Text. Res. J. 68, 739–748 (1998).

Beauchaine, J. P., Peterman, J. W. & Rosenthal, R. J. Applications of FT-IR/microscopy in forensic analysis. Mikrochim. Acta 94, 133–138 (1988).

Yao, J., Liu, Y. & Yang, S. Characterization of secondary structure transformation of stretched and slenderized wool fibers with FTIR spectra. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 3, https://doi.org/10.1177/155892500800300205 (2008).

Glassford, S. E., Byrne, B. & Kazarian, S. G. Recent applications of ATR-FTIR spectroscopy and imaging to proteins. BBA Proteins Proteom. 12, 2849–2858 (2013).

Lomont, J. P., Ostrander, J. S. & Ho, J.-J. Not all β-Sheets are the same: amyloid infrared spectra, transition dipole strengths, and couplings investigated by 2D-IR spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 121, 8935–8945 (2017).

Cao, J. Melting study of the α-form crystallites in human hair keratin by DSC. Thermochim. Acta 335, 5–9 (1999).

Barth, A. & Zscherp, C. What vibrations tell about proteins. Q. Rev. Biophys. 35, 369–430 (2002).

Dousseau, F. & Pezolet, M. Determination of the secondary structure content of proteins in aqueous solutions from their amide I and amide II infrared bands. Comparison between classical and partial least-squares methods. Biochemistry 29, 8771–8779 (1990).

Byler, D. M. & Susi, H. Examination of the secondary structure of proteins by deconvolved FTIR spectra. Biopolymers 25, 469–487 (1986).

KIM, Y., KIM, T. & CHOI, H. M. Qualitative identification of cashmere and yak fibers by protein fingerprint analysis using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 16, 5563–5571 (2013).

Cardamone, J. M. Investigating the microstructure of keratin extracted from wool: peptide sequence (MALDI-TOF/TOF) and protein conformation (FTIR). J. Mol. Struct. 969, 97–105 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. 22BKG009), Gansu Provincial Science and Technology Major Projects (Grant No. 25ZDFA014), the opening project of the Key Laboratory of the Ministry of Education, School of Cultural Heritage, and the opening project of Gansu Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology (Grant No. SJDK-2024-001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.X.: performed experimental, data analyses, and drafted the manuscript. Y.W.: major revision of the manuscript, project supervision, and contributed equally to the article. W.C.: revised and provided guidance for the manuscript. Y.X.: revised the manuscript and provided materials for research. C.Y.: revised the manuscript. H.T.: organized the archaeological materials for the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, W., Wei, Y., Chen, W. et al. Spectral and biomolecular evidence from fibers of two Hexi Corridor ancient turquoise mining sites. npj Herit. Sci. 14, 8 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02272-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02272-y