Abstract

Desiccation cracking and salt accumulation are major deterioration mechanisms in earthen sites within site museums, primarily caused by coupled moisture and salt migration under controlled environmental conditions. However, limited research on soil moisture–salt interactions has hindered the development of effective environmental control strategies. This study develops a moisture–salt migration model for the partition walls of Pit 1 at the Emperor Qin’s Mausoleum Site Museum, using the Richards equation and Fick’s law. The model was validated through soil column evaporation experiments and numerical simulations. Simulations over a six-year period under natural ventilation revealed that this condition was ineffective in preventing moisture loss and salt accumulation. While unsaturated humidity control provided short-term delay in deterioration, only saturated humidity (100% RH) effectively prevented long-term moisture loss and salt crystallization. These findings indicate that sustaining a saturated humidity environment is an effective strategy for the long-term preventive conservation of earthen sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Earthen sites, primarily composed of soil, are archaeological remains predominantly found in Asia but also distributed globally1. In China, over 250,000 earthen sites have been identified, primarily consisting of ancient settlements and tombs2. Although most of these sites are preserved in situ within site museums, inadequate environmental control leads to widespread deterioration, severely limiting their long-term stability. The Emperor Qin’s Mausoleum Site Museum serves as a typical example of earthen site preservation in China. Since its opening in 1979, common deterioration phenomena, such as desiccation cracking and salt efflorescence, have frequently occurred on the site’s surface3. These phenomena directly damage the soil structure and cause further deterioration through processes such as pulverization, exfoliation, and collapse, indirectly threatening the terracotta warriors in the mausoleum pits. Earthen sites hold significant historical and cultural value, and preserving their environments requires in-depth investigation.

The preservation environment of earthen sites is directly affected by the surrounding air, with changes in soil moisture content playing a critical role in their deterioration4. Once exposed, evaporation accelerates, and salts migrate upward, resulting in efflorescence and progressive structural damage5. However, research on moisture regulation in earthen sites remains limited, hindering effective suppression of deterioration6,7,8.

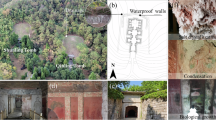

A representative example is the Terracotta Army pits, a key component of the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum, which includes four excavated pits covering over 25,000 m² 9. Pit 1, opened to the public in 1979, was originally located 3–5 m underground, in long-term equilibrium with the surrounding deposits (Fig. 1a). Excavation transformed it into an air-soil coupled system, with direct exposure to the atmosphere triggering rapid evaporation and capillary-driven salt migration. These processes have caused persistent desiccation cracking and salt efflorescence (Fig. 1b, c), particularly on the earthen partition walls. Since Pit 1 has remained under natural ventilation without effective environmental control, the need for scientifically sound preservation measures has become increasingly urgent.

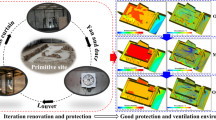

However, existing environmental control strategies are primarily designed for movable cultural relics, especially those housed in enclosed display cases. These strategies cannot be directly applied to immovable, open-site earthen sites, such as the Terracotta Army pits (Fig. 2). In recent years, researchers have increasingly focused on the specific requirements for environmental control to preserve earthen sites in site museums. Gu et al.10 found that strong air convection in large halls accelerates moisture and salt loss, and recommended using air curtains to maintain a stable microenvironment. Chen et al.11 conducted a year-long environmental monitoring campaign at the Laohuling site of the Liangzhu ruins and found that under high-humidity conditions, condensation consistently exceeded evaporation, which helped maintain the moisture stability of earthen heritage. Huang et al.12 pointed out that when temperature and humidity gradients on the surface of stone relics are reduced, internal condensation of water vapor may preferentially occur, leading to latent moisture damage. Luo et al.13 developed a high-humidity (relative humidity (RH) around 100%) localized environment using evaporative cooling technology, which effectively delays moisture loss. These studies indicate that current approaches to controlling the environment of earthen sites focus primarily on regulating humidity. One approach uses air conditioning systems to maintain constant temperature and humidity to mitigate cracking, while another creates high-humidity environments to reduce evaporation and slow moisture migration. However, these control measures still lack a systematic evaluation of their effects on moisture-salt migration mechanisms within earthen sites.

The exhibition area of the Terracotta Army pits is vast, with highly complex pit structures9. Conducting large-scale environmental control experiments directly in the pits presents operational and structural safety risks, as well as high costs and limited reproducibility. Therefore, this study uses numerical simulations to systematically evaluate the effects of various preservation environments on moisture-salt dynamics in earthen sites. This study utilizes the HYDRUS platform14, incorporating Richards and Fick equations, to simulate moisture and salt migration in earthen sites. The current use of HYDRUS in this context is still limited. Previous studies by Xia et al.15 and Chang et al.16 focused on unregulated museum environments, examining moisture and salt distribution in soil layers or at the interface with buried artifacts. However, the role of controlled indoor humidity, closely linked to desiccation and salt accumulation, remains insufficiently studied. This research fills that gap by simulating both natural conditions and various humidity control strategies to inform preventive conservation.

The main objectives of this study are: (1) to develop a mathematical model of moisture-salt migration in earthen sites relevant to museum preservation and validate its accuracy through soil column evaporation experiments; (2) to simulate the evolution of moisture-salt dynamics in Pit 1 of the Terracotta Army under uncontrolled conditions; (3) to evaluate the effects of existing humidity control strategies on moisture-salt migration in earthen sites. Through these efforts, the study aims to identify deterioration risks under the current preservation environment of Pit 1 of the Terracotta Army, assess the adaptability and feasibility of various humidity control strategies, and provide both theoretical and simulation-based support for implementing future environmental control measures in museums.

Methods

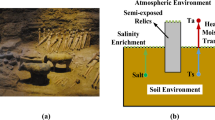

Influence of Air Humidity on Moisture-Salt Migration in Earthen Sites

Air humidity significantly influences moisture-salt migration in earthen sites by regulating surface evaporation (Fig. 3). In unsaturated soils, lower surface RH reduces water potential, steepens the gradient, and enhances the upward migration of liquid water and vapor17. This accelerates surface evaporation and salt accumulation. In contrast, a high-humidity environment reduces the gradient, inhibits evaporation and salt migration, and slows the development of desiccation cracking and salt-induced damage. This process can be quantified using the Kelvin equation18, as shown in Eq. (1). The Kelvin equation used in this study is expressed in its equivalent moisture head form, aiming to establish a relationship between air RH and matric potential in unsaturated soils. It describes the moisture potential response of the soil matrix, rather than pore-scale effects.

where \(h\) denotes the equivalent pressure head at the soil surface (m, with negative values indicating suction), \(R\) is the universal gas constant (8.314 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹), \(T\) is the temperature (K), \({\rho }_{w}\) is the moisture density (kg·m⁻³), \(g\) is the gravitational acceleration (9.81 m·s⁻²), \({V}_{w}\) is the molar volume of moisture (m³·mol⁻¹), and RH is the RH of the environment (dimensionless, with values ranging from 0 to 1). Although high humidity can suppress moisture evaporation from earthen sites, its long-term effects on coupled moisture-salt migration processes still require further investigation.

Geometric and Mathematical Model

Moisture-salt migration in earthen sites is governed by mass transport processes in unsaturated porous media. Classical models based on the Richards equation and Fick’s law have been widely used in agricultural and environmental contexts to simulate moisture-salt migration. Their accuracy and generalizability have been validated through laboratory and field studies under diverse hydrological and climatic conditions19,20,21,22,23. However, their application to immovable archaeological sites, such as the Terracotta Army pits, is still limited. Given that the soil in the pits exhibits typical unsaturated characteristics, this study develops a Richards-Fick-based model, supported by experimental validation and numerical simulation, to investigate the coupling between indoor environmental regulation and moisture-salt migration in earthen partition walls.

Pit 1 of the Emperor Qin’s Mausoleum Site Museum is a large underground corridor-type earthen structure, with sidewalls and internal partition walls made of rammed earth. This earthen structure is an integral part of the Terracotta Army site, providing essential environmental support for the preservation and display of the terracotta warriors, with irreplaceable protective and structural functions24. In Pit 1, the earthen partition walls have a rectangular symmetrical configuration, with an average height of approximately 170 cm. To simplify the modeling, the soil of the partition walls was assumed to be homogeneous, with contact surfaces uniformly exposed to surrounding air. Based on field survey data and actual structural characteristics, a two-dimensional geometric model of the partition wall was created (Fig. 4). The values for wall height, width of the upper surface, and the widths of the adjacent corridor on each side were set to 170 cm, 208 cm, and 100 cm, respectively.

Partial differential equations were solved numerically using the finite element method (FEM) to simulate two-dimensional unsaturated flow within the partition wall. The two-dimensional Richards equation was used to describe moisture movement in the partition wall14, as shown in Eq. (2).

where \(\theta\) is the volumetric moisture content (\({{\rm{L}}}^{3}\cdot {{\rm{L}}}^{-3}\)); \(K(\theta )\) is the unsaturated hydraulic conductivity (\({\rm{L}}\cdot {{\rm{T}}}^{-1}\)), \(t\) is time (\({\rm{T}}\)), \({\rm{x}}\) is the horizontal coordinate (\({\rm{L}}\)) and \(z\) is the vertical coordinate (\({\rm{L}}\)).

The van Genuchten–Mualem constitutive relationships were used to describe the soil moisture-retention curve and unsaturated hydraulic conductivity of the partition wall14,25. These relationships are expressed in Eqs. (3) and (4).

where \({\theta }_{s}\) is the saturated moisture content (\({{\rm{L}}}^{3}\cdot {{\rm{L}}}^{-3}\)), \({\theta }_{r}\) is the residual moisture content (\({{\rm{L}}}^{3}\cdot {{\rm{L}}}^{-3}\)), \(h\) is the pressure head (\({\rm{L}}\)), \(K(h)\) is the unsaturated hydraulic conductivity (\({\rm{L}}\cdot {{\rm{T}}}^{-1}\)), \({K}_{s}\) is the saturated hydraulic conductivity (\({\rm{L}}\cdot {{\rm{T}}}^{-1}\)), \({S}_{e}\) is the effective saturation, given by correlation: \({S}_{e}=\frac{\theta (h)-{\theta }_{r}}{{\theta }_{s}-{\theta }_{r}}\), \(\alpha\) is an empirical parameter related to soil’s physical properties, \(l\) is the pore-connectivity parameter, commonly assumed to have a value of 0.5 and \(n\) is a pore-size distribution parameter of the porous medium, which is obtained using the correlation: \(m=1-\frac{1}{n}\).

The two-dimensional advection-dispersion equation (expressed in Eq. (5)) was used to describe the transport of soluble salts in the soil of the partition wall, incorporating advection, diffusion, and dispersion14.

where \(C\) is the solute content (\({\rm{M}}\cdot {{\rm{L}}}^{-3}\)), \(q\) is the moisture flux density (\({\rm{L}}\cdot {{\rm{T}}}^{-1}\)), \(t\) is time (\({\rm{T}}\)), and \(D\) is the hydrodynamic dispersion coefficient under saturated–unsaturated conditions (\({{\rm{L}}}^{2}\cdot {{\rm{T}}}^{-1}\)).

In addition, adsorption equilibrium between the solute content in solid and liquid phases of the soil of partition wall is described by Eq. (6)14,25.

where \(S\) is the solute content adsorbed in the solid phase (g·g⁻¹), \({k}_{d}\) is the solute adsorption coefficient, and \(\beta\) and \(\eta\) are empirical parameters. In the present study, adsorption of soluble salt ions in soil was relatively weak and approximated using the Langmuir nonlinear adsorption model, with \(\beta\) and \(\eta\) set to have values of 1 and 0.005, respectively.

Equations (2) to (6) were solved using the HYDRUS 5.03 software package. The governing partial differential equations were discretized using the Galerkin linear finite element method, with time discretization handled by an implicit finite difference scheme. The resulting nonlinear equations were linearized through an iterative process.

Model Input Parameters

The compacted soil of the partition walls in Pit 1 of the Emperor Qin’s Mausoleum Site Museum has an average bulk density of 1.6 g/cm³ and is classified as light clay loam. The soil particle composition was used as input for a neural network-based pedotransfer function to estimate hydraulic parameters, including the moisture retention curve and saturated hydraulic conductivity14. This method considers sand, silt, and clay content, along with bulk density, to derive key soil hydraulic properties (Table 1). The physical properties and texture of the soil were directly obtained from museum data to ensure realistic model inputs.

Sodium sulfate (Na₂SO₄) is the dominant soluble salt at the site and was selected as the representative solute in the model26. Although multiple salts coexist, Na₂SO₄ was prioritized due to its high frequency and strong deterioration potential. Specifically, dissolved Na⁺ and SO₄²⁻ ions can combine to precipitate as sodium sulfate decahydrate (Na₂SO₄·10H₂O, mirabilite), a phase whose crystallization is accompanied by significant volumetric expansion.

To simplify the model, the migration behavior of Na₂SO₄ was approximated by using the transport parameters of Na⁺ ions. The model focused on macroscopic moisture-salt dynamics under long-term humidity regulation, rather than microscopic crystallization behavior. For solute transport, longitudinal dispersivity was set to 10 cm, and transverse dispersivity to 1 cm.

All soil hydraulic, solute transport, and adsorption parameters used in the model are summarized in Table 2.

Initial and Boundary Conditions

The computational domain of the partition wall in Pit 1 was constructed in HYDRUS-2D and discretized using an unstructured finite element mesh (Fig. 5). Since the upper surface of the partition wall was directly exposed to air, where evaporation and soluble salt transport were most active, the mesh in this region was locally refined to improve computational accuracy. To test the independence of the grid number, four discretization schemes were designed, containing 8093, 10,682, 23,766, and 43,535 triangular elements. The results showed that the relative error in mass balance for all schemes was less than 1%, and the differences in simulated moisture content and salt content between the 23,766- and 43,535-element schemes were within 1%. This indicated that the simulation results were insensitive to mesh density, demonstrating good grid independence for the 23,766-element scheme, which was used for all subsequent simulations.

According to survey data from the Emperor Qin’s Mausoleum Site Museum, the average moisture content of the partition wall at excavation was approximately 0.20 cm³·cm⁻³, while the Na₂SO₄ content was approximately 2 µmol·cm⁻³9. Therefore, the initial moisture content of the computational domain was set to 0.20 cm³·cm⁻³, and the initial salt content was set to 2 µmol·cm⁻³.

For boundary conditions, the upper surface of the computational domain was defined as the soil-atmosphere interface, with moisture fluxes driven by meteorological inputs. The evaporation flux was calculated using the Penman equation to estimate potential evaporation rates. Solute transport at the upper boundary was defined using a third-type (Cauchy) boundary condition, allowing both convective and diffusive salt migration driven by moisture movement. The lower vertical boundaries on both sides were specified as no-flux boundaries for both moisture and solute, implying no cross-boundary exchange. The bottom boundary was defined as a free-drainage condition for moisture, permitting downward flow under gravity. For solutes, a third-type boundary condition was also applied at the bottom, allowing downward transport with moisture movement.

Additionally, since desiccation cracking in earthen sites typically occurs within the upper 10 cm, observation points were placed at the surface, 5 cm, and 10 cm depths in the computational domain to monitor the distribution and dynamics of moisture-salt migration.

Soil Column Experiment and Simulation Configuration

To validate the applicability of the proposed model, a soil column evaporation experiment was conducted, and the results were compared with those obtained from numerical simulations. As shown in Fig. 6a, b, the experiment used a soil column 100 cm in height and 30 cm in diameter, with soil texture parameters consistent with those of the partition wall soil at Emperor Qin’s Mausoleum Site Museum. In this study, the soil column simulation experiments were conducted under naturally ventilated indoor conditions (Fig. 7). Similar to the environment in the Emperor Qin’s Mausoleum Site Museum, both temperature and humidity exhibited unstable fluctuations. The temperature ranged from 22.6 °C to 33.4 °C, with an average of 28.7 °C, while the RH ranged from 42.3% to 79.9%, with an average of 60.6%.

The initial moisture content of the soil column was set to 0.20 cm³·cm⁻³, with the top surface exposed to laboratory air. All other surfaces of the column were sealed. The experiment lasted for 60 days. Sampling points were placed within 10 cm below the surface of the soil column at 2 cm intervals, yielding a total of six samples. After sampling, the specimens were oven-dried at 105 °C for 8 hours to determine gravimetric moisture content, which was then converted to volumetric moisture content. In parallel, the salt content in the samples was determined using ion chromatography.

As shown in Fig. 6c, a two-dimensional soil column model matching the experimental conditions was constructed. The initial conditions of the model were identical to those in the experiment. Specifically, the initial moisture content was 0.20 cm³·cm⁻³, and the initial salt content was 1.85 µmol·cm⁻³. The top surface was defined as the atmospheric boundary, with potential evaporation calculated using the Penman equation. All other boundaries were set as zero-flux. Observation points in the model were placed at the same positions as the experimental sampling points to enable direct comparison of the moisture and salt evolution patterns.

Simulation Scenarios

Since Pit 1 is located in an enclosed exhibition hall, solar radiation was excluded from the model to simplify calculations. The ambient airflow velocity around the pit was set to 0.15 m/s, consistent with the safety threshold commonly adopted in museum micro-environments15. In all regulated scenarios, the temperature was maintained at a constant 20 °C to eliminate the influence of thermal fluctuations. Based on these considerations, two categories of simulation scenarios were designed, as follows.

-

Scenario I: Natural Ventilation (Case 1)

This scenario simulated the evolution of moisture-salt dynamics in the partition walls of Pit 1 under the current preservation conditions at the Emperor Qin’s Mausoleum Site Museum. The objective was to reveal moisture-salt migration patterns under natural ventilation and predict potential deterioration risks. The environmental boundary conditions were derived from measured temperature and RH data of the museum from 2018 to 2024 (six years), as shown in Fig. 8.

-

Scenario II: Humidity Control (Case 2–5)

This scenario simulated moisture-salt migration in the partition walls under different RH conditions, aiming to evaluate the applicability of various strategies to regulate humidity for site preservation. Since most earthen sites in museums exhibit visible desiccation cracking within three years of excavation, the simulation period was set to three years. The detailed simulation conditions are provided in Table 3.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the performance of the proposed model, both the root mean square error (RMSE) and the mean relative error (MRE) were used to compare experimental and simulation results. Specifically, the measured moisture content and salt content at each sampling position in the soil column experiment were used as references and compared with the corresponding simulated values at the observation points, as defined by Eqs. 8 and 9.

where \({a}_{i}\) and \({b}_{i}\) denote the measured (experimental) and predicted (simulated) values of moisture content or salt content, respectively, and \(n\) is the total number of observation points.

Results

Model Validation

The accuracy of the proposed model was validated by comparing the results from the soil column experiments with those from numerical simulations. Figure 9 shows the distributions of moisture and salt content in the soil column on Day 60, derived from both experimental measurements and simulations. Table 4 lists the RMSE and MRE for the measured and simulated moisture and salt contents. The results indicated strong agreement between the simulated and measured values in both magnitude and spatial distribution. The calculated RMSE values were 0.003 cm³·cm⁻³ for moisture and 0.044 µmol·cm⁻³ for salt content. The corresponding MRE values were 1.28% for moisture and 1.92% for salt, further demonstrating the model’s reliability in reproducing moisture-salt migration processes. The simulation may underestimate early-stage evaporation and salt crystallization because it does not explicitly account for vapor-phase diffusion, which can become significant under low RH due to steep vapor pressure gradients. Given that the soil texture and ambient conditions in the experimental setup closely resemble those of the partition walls in Pit 1 at the Emperor Qin’s Mausoleum Site Museum, the validation supports the model’s applicability for simulating moisture-salt dynamics in actual earthen sites.

Moisture–Salt Distribution in the Partition Walls of Pit 1 under Natural Ventilation

Figure 10 presents the simulation results of moisture-salt dynamics in the partition walls of Pit 1 over six years under current preservation conditions. Under natural ventilation, the moisture content in the surface layer decreases rapidly, with the rate of decline slowing as depth increases. Among the three observation points, the surface (Obs. 1) exhibited the fastest decline, followed by the 5 cm depth (Obs. 2) and the 10 cm depth (Obs. 3). According to the museum’s survey data, desiccation cracking is likely to occur when the moisture content falls below 0.17 cm³·cm⁻³ 27. As shown in Fig. 10a, the surface soil reached approximately 0.17 cm³·cm⁻³ on Day 12, entering the desiccation risk zone, while the 5 cm and 10 cm depths reached this threshold on Days 227 and 948, respectively. The contour plots for moisture content (Fig. 11) further illustrated a consistent “low surface–high interior” gradient, with the surface consistently maintaining low values in later stages. Notably, the upper corners exhibited the lowest moisture content, suggesting that these regions were most vulnerable to desiccation cracking.

In response to changes in moisture content, the salt content in the surface layer increased markedly as moisture content decreased, eventually stabilizing at a high level. As shown in Fig. 10b, salt accumulation was fastest at the surface and slower at the 5 cm and 10 cm depths. The contour plots for the distribution of salt (Fig. 12) showed minimal changes in the soil interior, with accumulation concentrated at the surface and gradually extending downward to the 5 cm depth over time. Additionally, the highest concentrations occurred at the bottom corners and intensified over time, suggesting that these regions were at high risk of severe salt damage.

In summary, under natural ventilation conditions, the moisture-salt dynamics of the partition walls were largely governed by environmental factors. The surface quickly entered the desiccation cracking risk zone, accompanied by accelerated salt accumulation, leading to coupled deterioration driven by both cracking and salt damage. Since the present simulation did not account for airflow disturbances caused by visitors’ activities, the actual rate of surface moisture loss may be even higher, further intensifying localized salt accumulation and crack development, thereby posing a greater threat to the long-term stability of the earthen site.

Moisture Content Dynamics in Partition Walls under Different Humidity Conditions

Figure 13 illustrates variations in moisture content at various observation points in the partition walls of Pit 1 under different humidity conditions (Fig. 13a, b, c), as well as the average surface moisture content during the first month of simulation (Fig. 13d). The results indicated that among the five scenarios, only Case 5 (RH = 100%) achieved sustained and significant suppression of moisture loss. During the first 30 days, moisture content decreased fastest under the dry conditions of Cases 2 and 3, followed by natural ventilation (Case 1) and the high-humidity condition (Case 4), while Case 5 showed the slowest decrease in moisture content. Notably, at certain times, the decrease in moisture content for Case 1 was slightly lower than that for Case 4, primarily because relatively humid external conditions increased indoor humidity under natural ventilation conditions. This difference gradually diminished over the course of the simulation. Overall, the inhibitory effect of high-humidity environments on moisture loss was strongest during the early stages of the simulation.

Figure 14 presents contour plots of moisture content distribution in the partition walls under different humidity conditions. Overall, Cases 2 and 3 showed little difference from the natural ventilation conditions (Case 1), whereas under the high-humidity conditions of Cases 4 and 5, the loss of surface moisture in the partition walls was significantly delayed during the early stages. As the simulation progressed, the overall moisture content in Case 4 gradually approached that of Cases 1–3. In contrast, Case 5 consistently exhibited the strongest suppression of moisture loss, with overall moisture content in the partition walls remaining at a relatively high level throughout the simulation.

In summary, compared to natural ventilation, environmental control effectively slowed the decline in moisture content of the partition walls, with the effect being most pronounced during the first 30 days of regulation. Overall, high-humidity conditions outperformed dry conditions, with the saturated state at 100% RH (Case 5) providing the most effective and sustained moisture preservation throughout the simulation period.

Salt Content Dynamics in Partition Walls under Different Humidity Conditions

Figure 15 shows variations in salt content in the partition walls of Pit 1 under different humidity conditions, with Fig. 15a, b, c illustrating changes at the observation points and Fig. 15d showing the average surface salt content during the first month. The results indicated that among the five scenarios, only Case 5 (RH = 100%) significantly suppressed the increase in salt content. Cases 1–4 exhibited similar variation trends, characterized by a continuous increase in salt content. As shown in Fig. 15d, Case 5 exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect on surface salt accumulation under saturated conditions. Case 4 also exhibited partial suppression in the early stage, but the effect gradually diminished, ultimately approaching the levels of Cases 1–3.

Figure 16 presents contour plots of salt distribution in the partition walls of Pit 1 under different humidity conditions. Overall, Cases 2 and 3 showed little difference from the natural ventilation conditions (Case 1), while under high-humidity conditions (Cases 4 and 5), surface salt accumulation was significantly reduced, with Case 5 exhibiting the strongest effect. In Case 5, surface salt accumulation in the partition walls of Pit 1 was reduced by approximately half compared to other scenarios, indicating that saturated humidity conditions provided the strongest inhibition of salt damage risk.

In summary, compared to natural ventilation, high-humidity environments effectively slowed the accumulation of surface salt on the partition walls, with the effect being most pronounced during the early stages of regulation. Among the various scenarios, 100% RH (Case 5) consistently provided the strongest inhibition of salt damage throughout the simulation, significantly reducing the risk of surface salt accumulation.

Discussion

This study systematically investigated the spatiotemporal dynamics of moisture and salt migration in earthen sites under controlled museum environmental conditions. A coupled moisture–salt transport model, incorporating Richards’ equation and Fick’s law, was developed and validated using a 60-day soil column evaporation experiment. Simulation results showed strong agreement with measured moisture and salt distributions, confirming the model’s reliability in capturing the drying behavior of rammed earth. The model was further applied to simulate the long-term evolution of moisture and salt in the partition walls of Pit 1 at the Emperor Qin’s Mausoleum Site Museum under natural ventilation. The results revealed rapid surface drying and progressive salt accumulation, especially in the upper and corner regions, indicating a substantial risk of structural deterioration in the absence of environmental control.

Humidity regulation strategies were subsequently evaluated using the model. Among the simulated scenarios, saturated conditions (RH = 100%) consistently suppressed both moisture loss and surface salt accumulation throughout the simulation period. Moderate humidity levels (e.g., RH = 90%) offered limited protective effects during the early stages, whereas natural ventilation and low RH conditions were largely ineffective. These findings offer quantitative evidence that localized high-humidity environments can play a crucial role in mitigating deterioration risks in earthen heritage displays.

However, fully saturated environments may pose additional challenges. High relative humidity can facilitate microbial growth and condensation, potentially accelerating the deterioration of organic materials, including the Terracotta Warriors. Therefore, an integrated environmental control strategy is essential. A hybrid approach is recommended: maintaining localized microenvironments with RH close to 100% around vulnerable walls using physical enclosures or air curtains, while controlling the ambient RH of the exhibition hall at approximately 60% to minimize microbial risks. This strategy provides targeted protection without compromising the overall safety of the exhibition environment.

Although the current model successfully simulates coupled moisture–salt transport, several limitations warrant further consideration. Phase transitions, such as freeze–thaw cycles and salt crystallization–deliquescence dynamics, were not explicitly incorporated into the model. Under low-temperature conditions, freezing can reduce soil permeability and alter water transport pathways. Similarly, sodium sulfate (Na₂SO₄) can undergo repeated crystallization and dissolution, leading to volume expansion and pore structure alteration, which may significantly influence long-term salt redistribution. Incorporating these multiphysical processes into future models will enhance simulation fidelity.

Additionally, the study adopted a single-salt assumption, selecting sodium sulfate (Na₂SO₄) as the representative species due to its high detection frequency at the site and its known potential to cause damage via phase transitions. Although various salts often coexist and interact in complex ways under fluctuating relative humidity and temperature conditions, the single-salt approach allowed for a clearer assessment of RH effects. Despite this simplification, the results offer a representative foundation for prioritizing humidity control strategies in conservation practices. Future studies should incorporate multi-salt systems and examine their competitive or synergistic transport behaviors to better reflect real-world complexity.

Overall, this study provides both theoretical insights and practical guidance for the environmental management of earthen archaeological sites in museum settings. The findings emphasize the critical role of precise microclimate regulation and underscore the value of model-based analysis in optimizing heritage conservation strategies.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

References

Briseghella, B. et al. Seismic analysis by macroelements of fujian hakka tulous, chinese circular earth constructions listed in the UNESCO world heritage list. International Journal of Architectural Heritage 14, 1551–1566 (2020).

Chang, B., Shen, C., Luo, X., Hu, T. & Gu, Z. Moisturizing an analogous earthen site by ultrasonic water atomization within Han Yangling Museum, China. Journal of Cultural Heritage 66, 294–303 (2024).

Hu, T. et al. Characterization of winter airborne particles at Emperor Qin’s Terra-cotta Museum, China. Science of the Total Environment 407, 5319–5327 (2009).

Luo, X. et al. Environmental control strategies for the in situ preservation of unearthed relics in archaeology museums. Journal of Cultural Heritage 16, 790–797 (2015).

Chang, B., Wen, H., Yu, C. W., Luo, X. L. & Gu, Z. L. Preservation of earthen relic sites against salt damages by using a sand layer. Indoor and Built Environment 31, 1142–1156 (2022).

Qu, J., Sun, M., Wang, F., Liu, K. & Miao, W. Analysis of microenvironment characteristics and the impact on the preservation of heritage sites: a case study of the Jinsha Earthen Site. npj Heritage Science 13, 109 (2025).

Liu, B. et al. Study on the control effectiveness of relative humidity by various ventilation systems for the conservation of cultural relics. Heritage Science 12, 305 (2024).

Yao, X. & Zhaso, F. A comprehensive evaluation of the development degree and internal impact factors of desiccation cracking in the Sanxingdui archaeological site. Heritage Science 11, 93 (2023).

Zhang, Z. Research on the Preservation of the Terracotta Warriors of the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum. 1998: Shaanxi People’s Education Publishing House. 200.

Gu, Z. et al. Primitive environment control for preservation of pit relics in archeology museums of China. Environmental science & technology 47, 1504–1509 (2013).

Chen, M., Sun, H., Zhang, B., Gao, H. & Hu, Y. Hu, Analysis of evaporation-condensation cycles at archaeological earthen sites preserved under high-humidity conditions, The European Physical Journal Plus. 139 (2024).

Huang, J., Zheng, Y. & Li, H. Study of internal moisture condensation for the conservation pof stone cultural heritage, J. Cultural Heritage, (2022).

Luo, X., Chang, B., Tian, W., Li, J. & Gu, Z. Experimental study on local environmental control for historical site in archaeological museum by evaporative cooling system. Renewable Energy 143, 798–809 (2019).

Šimůnek, J., Brunetti, G., Jacques, D., van Genuchten, M. T. & Šejna, M. Developments and applications of the HYDRUS computer software packages since 2016. Vadose Zone Journal 23, e20310 (2024).

Xia, Y., Fu, F., Wang, J., Yu, C. W. & Gu, Z. Salt enrichment and its deterioration in earthen sites in Emperor Qin’s Mausoleum Site Museum, China. Indoor and Built Environment 32, 1862–1874 (2023).

Chang, B. et al. Dynamic modeling of the moisture and salt’s transport in the unearthed terracotta warriors of emperor Qin’s mausoleum museum, China. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer 156, 107664 (2024).

Luo, S., Lu, N., Zhang, C. & Likos, W. Soil water potential: A historical perspective and recent breakthroughs. Vadose Zone Journal 21, e20203 (2022).

Xie, H., Gong, G. & Wu, Y. Investigations of equilibrium moisture content with Kelvin modification and dimensional analysis method for composite hygroscopic material. Construction and Building Materials 139, 101–113 (2017).

Nimmo, J. R. New insights on the origin of the Richardson-Richards equation. Hydrological Sciences Journal 69, 2153–2158 (2024).

Lazarovitch, N. et al. Modeling of irrigation and related processes with HYDRUS. Advances in Agronomy 181, 79–181 (2023).

Nick, S. M. et al. Impact of soil compaction and irrigation practices on salt dynamics in the presence of a saline shallow groundwater: An experimental and modelling study. Hydrological Processes 38, e15135 (2024).

Guo, S. et al. Experimental and numerical evaluation of soil water and salt dynamics in a corn field with shallow saline groundwater and crop-season drip and autumn post-harvest irrigations. Agricultural Water Management 305, 109119 (2024).

Kim, D. H., Kim, J., Kwon, S. H., Jung, K.-Y. & Lee, S. H. Simulation of soil water movement in upland soils under sprinkler and spray hose irrigation using HYDRUS-1D. Journal of Biosystems Engineering 47, 448–457 (2022).

Wang, Y., Li, J., Xia, Y., Chang, B. & Luo, X. A case study investigation-based experimental research on transport of moisture and salinity in semi-exposed relics, Heritage Science. 12 (2024).

Simunek, J., van Genuchten, M. T. & Sejna, M. Development and applications of the HYDRUS and STANMOD software packages and related codes. Vadose zone journal 7, 587–600 (2008).

X.y. Liu, Mechanism and simulation of efflorescence at K9901 funerary pit of the Emperor Qin. 2015, Northwest A&F University.

Rong, B. et al. Research on soil excavated from pit No. 2 of the First Emperor Qin Shihuang shrinkage characteristic curves. Northern Cultural Relics 1, 41–44 (2012).

W. M. Haynes, CRC handbook of chemistry and physics. 2016, Boca Raton: CRC press.

A. Handbook, HVAC applications Chapter 23: Museum, galleries, archives, and libraries, American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, SI Edition; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, (2015).

J. 66-2015, Code for Design Museum Building, Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China, Beijing, 2015.

U. 10829, Works of art of historical importance. Ambient conditions for the conservation. Measurement and analysis. 1999, UNI Ente Nazionale Italiano di Unificazione Milano.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi (2024SF-YBXM-679) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52078417).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.B. and L.X. conceptualized the study and were responsible for the methodology, data curation, and visualization. The original manuscript draft was prepared by C.B. and L.X. Y.X. and F.F. contributed to the investigation. T.Y., Z.C., and C.M. participated in reviewing and editing the manuscript. L.X. was responsible for software development, supervision, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, B., Tu, Y., Yang, X. et al. Prediction of the Effects of Indoor Relative Humidity on Moisture and Salt Migration in Earthen Sites at the Emperor Qin’s Mausoleum Site Museum. npj Herit. Sci. 14, 18 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02288-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02288-4