Abstract

Jiandu, ancient China’s primary writing medium before paper, frequently exhibits severe inscription degradation due to prolonged burial, making the texts difficult to decipher. To enhance textual visibility, this study proposes an adaptive infrared-visible image fusion method driven by Salient Spatial Attention (SSA), integrating the complementary strengths of both modalities to produce images with clear ink, texture, and color. First, an SSA module selectively enhances infrared ink features via adaptive feature selection, improving the visibility of faint inscriptions. Second, a multi-scale information measurement strategy ensures balanced representation of material texture and ink details. Finally, a tailored unsupervised loss function eliminates reliance on ground-truth images while preserving authentic visual characteristics. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed approach outperforms existing methods, particularly in preserving text details, material texture, and color fidelity. The resulting enhanced images offer valuable support for cultural-heritage preservation and Jiandu research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Jiandu, bamboo and wooden slips used for writing in ancient China1,2, served as the primary form of Chinese books before the invention of paper and significantly influenced later book systems. Their importance lies not only in preserving historical documents across political, economic, military, and cultural domains but also in serving as crucial evidence of the development and prosperity of the ancient Silk Road3. These artifacts hold significant historical, scientific, and artistic value. Compared to other ancient document carriers like oracle bones and bronze inscriptions, Jiandu were widely used due to their abundant raw materials and ease of production, serving as invaluable primary sources for understanding ancient society.

However, these bamboo and wooden artifacts are highly prone to damage, and their ink traces fade easily, making conventional visible imaging methods ineffective in preserving the original historical information. To overcome this challenge, researchers have utilized short-wave infrared technology, which can penetrate mineral pigments while being strongly absorbed by ink traces. Using infrared imaging, they successfully revealed hidden ink characters embedded within the fibers of bamboo slips and wooden tablets4,5. This method has produced two types of image data for the digitization and dissemination of Jiandu. One consists of Jiandu color images captured via conventional photography, and the other includes infrared images of ink traces obtained through infrared imaging.

To meet the urgent demands for Jiandu digital processing, researchers have concentrated on improving Jiandu infrared images. Zhang et al.6,7 introduced methods for character restoration and recognition using horizontal-vertical projection and threshold segmentation, while Zhang8 investigated threshold-based segmentation techniques for Jiandu. Wang et al.9 utilized multi-scale Retinex algorithms to enhance Jiandu images, while Zhang, Jia, and colleagues10,11 studied the use of Canny edge operators and unsharp masking methods for character enhancement. Zhang12 systematically studied Jiandu digital image enhancement and segmentation. These studies mainly relied on traditional image processing techniques applied to single Jiandu images for enhancing ink traces, but still needed to combine complementary information from both image types for effective research and analysis. As shown in Fig. 1, visible Jiandu images closely resemble what the human eye perceives, presenting high-definition textures, patterns, and color information of the material, although the ink traces show varying levels of degradation. In contrast, infrared images offer clearer ink trace information but lack the ability to distinguish material textures, which are crucial for Jiandu organization. Scholars studying Jiandu must integrate information from both modalities to perform tasks such as character identification, interpretation, segmentation, collation, and compilation. Cross-modal image comparison and switching analyses increase the workload for Jiandu research. As the quantity of excavated Jiandu increases and research advances in China, traditional multi-image comparison methods face unprecedented challenges. Thus, creating comprehensive images that combine the strengths of both modalities to replace the current dual-image comparison approach has become a pressing need in Jiandu research and cultural dissemination.

(left) Visible images clearly show the material texture of Jiandu slips while ink traces remain recognizable. (right) Ink traces in visible images have degraded, while infrared images still clearly present textual content. Color and infrared images of Han slips from Interpretation of the New Juyan Bamboo Slips, Volume 1.

Image fusion technology, as an effective method for integrating multi-source information, opens new research avenues for tackling Jiandu dual-modal image challenges. This technology integrates image information from different sources or modalities to generate fusion images with richer information. Traditional image fusion methods primarily include multiscale transforms, saliency detection, sparse representation, and subspace representation techniques13,14. Multi-scale transform methods such as wavelet transforms and non-subsampled contourlet transforms15,16 achieve information fusion by decomposing images into subimages at different scales; saliency detection methods17 simulate human visual attention mechanisms, guiding the fusion process by identifying important regions in images. Sparse representation methods18,19, relying on the principle that image signals can be linearly represented with a small number of atoms in an over-complete dictionary, integrate images via dictionary learning and coefficient fusion. Subspace representation methods20,21 extract independent components of images using techniques such as PCA, ICA, and NMF. Optimization-based methods22 guide fusion by designing objective functions to balance intensity fidelity and texture structure. Hybrid methods23,24 combine multiple technical advantages to alleviate edge blurring and detail loss issues. While these traditional methods excel in specific scenarios, their dependence on hand-crafted features and fusion rules limits adaptability to complex scenes and heterogeneous information.

Neural networks’ exceptional feature learning and non-linear fitting capabilities have led researchers to explore data-driven deep learning methods for infrared and visible image fusion25. Autoencoder-based methods26 retain the fundamental framework of traditional image fusion algorithms while enabling deep feature extraction. Prabhakar et al.27 introduced DeepFuse, pioneering the use of deep learning in image fusion; Li et al.28 developed DenseFuse, which extracts multi-scale features and enables feature reuse via dense connections; Li et al.’s NestFuse29 employed a multi-scale encoder-decoder architecture to enhance fusion performance. Autoencoder-based methods successfully achieve deep feature extraction, but their reliance on hand-crafted fusion rules limits their potential performance. For end-to-end CNN-based fusion algorithms, Zhang et al.30 developed frameworks preserving proportional gradient and intensity paths; Tang et al.31 proposed SeAFusion, bridging image fusion with high-level vision tasks through cascaded modules and semantic segmentation; Tang et al.32 introduced PIAFusion, which leverages dual attention mechanisms to enhance fusion quality. Ma et al.33 defined essential fusion information by introducing salient target masks, while Wu et al.34 proposed the U2Fusion framework, addressing training data limitations with unsupervised learning. End-to-end CNN methods overcome the limitations of hand-crafted fusion rules but encounter difficulties in handling images with significant modal differences.

As research advances, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have shown great promise for image fusion. Ma et al.35 introduced FusionGAN, the first application of GANs to infrared and visible image fusion; Ma et al.36 created DDcGAN, tackling data distribution imbalance with dual discriminators; Tang et al.37 proposed AttentionGAN, integrating multi-scale attention mechanisms with adversarial learning; Zhang et al.38 applied adversarial loss to general image fusion frameworks in IFCNN. GAN methods produce realistic fusion results but are prone to training instability and modal imbalance.

The introduction of Transformer architecture has provided new insights into image fusion. Li et al.39 introduced the DFENet fusion framework, integrating CNNs with Vision Transformers for medical image fusion. Li and Wu40 developed CrossFuse, using cross-attention mechanisms to enhance complementary information across modalities. Recent advancements in diffusion models have opened new pathways for fusion technology. et al.41 introduced the DDFM model, the first to apply diffusion models to multimodal image fusion. Liu et al.42 developed the Dif-Fusion model, which preserves high-fidelity color using novel color-fidelity loss and cross-modal guided sampling. Yang et al.43 proposed LFDT-Fusion, integrating diffusion models with transformers to improve general fusion efficiency. Emerging Transformer and diffusion models exhibit strong feature learning capabilities but are computationally intensive and mainly designed for general scenarios.

Despite significant advancements in image fusion, these methods are largely designed for natural scene images with uniform information distribution, such as surveillance and remote sensing. They rely on fixed fusion strategies that cannot adapt to image content and require extensive annotated data for supervised learning, limiting their utility in domains without ground truth labels. These methods are challenging to adapt directly to the unique requirements of Jiandu images. Jiandu image fusion faces unique technical challenges. First, visible and infrared Jiandu images differ significantly in their information distribution. Visible images capture globally distributed textures and colors, while infrared images highlight locally discrete, high-contrast ink traces. Existing general fusion methods struggle to handle such heterogeneous features effectively. Second, achieving adaptive information balance during fusion is crucial. Dynamically adjusting fusion weights for each Jiandu image pair, considering factors like ink trace degradation and bamboo slip texture complexity, is essential. Without adaptive capabilities, ink traces risk being overshadowed by background textures, or material authenticity might be compromised by overemphasis on ink traces. Finally, the primary goal of Jiandu image fusion is to recreate the ideal state of complete ink traces before historical fading occurred. This ideal state reflects the original appearance of Jiandu at the time of writing completion. However, this “perfect” state is unattainable in reality, and no ground truth label data exist for learning objectives. Therefore, Jiandu image fusion necessitates the development of entirely unsupervised learning frameworks.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a novel adaptive fusion method for Jiandu infrared-visible images utilizing salient spatial attention. This method effectively integrates dual-modal information using an end-to-end unsupervised network. The main contributions can be summarized as follows:

-

The dual-path attention network for differentiated feature enhancement introduces a novel SSA module that adaptively selects spatial locations to precisely enhance infrared ink signals while suppressing noise.

-

Multi-scale information measurement strategy for adaptive fusion: Distinct norms for different modalities dynamically evaluate multi-scale information, enabling intelligent weight allocation to balance ink clarity and material detail representation.

-

Unsupervised loss function tailored for Jiandu characteristics: A label-free loss function uses adaptive weights to guide optimization, ensuring the fusion result preserves key structural and pixel information from the source images while maintaining the original visual fidelity of the artifact.

Experimental results show that this method surpasses existing approaches in both subjective visual quality and objective evaluation metrics, offering more effective tool support for Jiandu digital research.

Methods

This section provides a detailed description of the adaptive fusion method for infrared-visible Jiandu images. The discussion starts with an introduction to the overall framework of the fusion task and its core challenges, followed by an analysis of the multi-modal characteristics of Jiandu images. Subsequently, the image registration module is described in detail, addressing the key challenge of cross-modal image alignment. The text further elaborates on complementary modal feature representation and the attention enhancement mechanism, including specialized feature extraction networks tailored to the distinct characteristics of visible and infrared images. Following this, a gradient-based multi-scale information measurement method and an adaptive feature importance evaluation mechanism are introduced, enabling dynamic optimization of the fusion process. The section concludes by describing the multi-objective loss function design and the fusion network architecture built on dense connections.

Overall Framework

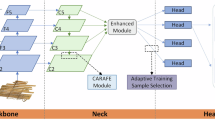

The slip image fusion task involves two different modal inputs: visible images Ivi ∈ RH×W×3 and infrared images Iir ∈ RH×W×1, where H and W denote the height and width of the images, respectively. Visible images capture material texture and color information of the slips, while infrared images emphasize ink information. The fusion framework aims to generate a fused image If that retains material details from visible images Ivi and text information from infrared images Iir. The specific fusion framework mainly consists of four core modules: an image registration module, a feature extraction module, a fusion module, and an image reconstruction module. For Jiandu infrared-visible images, registration alignment is performed first. Then, in the feature extraction module, we design dedicated feature extraction networks for the different characteristics of infrared and visible images, and calculate information measurements for the different extracted features to evaluate the importance of features at different scales. The fusion module adaptively combines multi-modal features based on the measurement results, while the image reconstruction module ensures that the fused image retains color and clarity consistent with the input images. The general flow of the algorithm is shown in Fig. 2.

Image Registration

This section introduces a prerequisite task for image fusion. The primary challenge in cross-modal registration of ancient slip images is managing the modal differences between visible and infrared images. Due to ink degradation in slip text, the images exhibit weak texture features, discontinuous edges representing structural information, and sparse corner details. These characteristics hinder traditional registration methods based on local features from achieving satisfactory results. To address this issue, we propose the similarity transform and affine image registration (STAIR) algorithm, which integrates similarity transformation and affine registration. This method constructs a multi-modal optimization framework that avoids reliance on unstable local feature matching and leverages overall structural information for registration, as shown in Fig. 3.

The STAIR algorithm employs a two-step registration strategy. The first step applies similarity transformation for preliminary registration. During this process, the visible image serves as the reference, while the infrared slip image is registered against it. Using a transformation matrix, the infrared image is transformed to align with the position of the reference visible image. The transformation matrix can be represented as:

where Ts is the matrix of similarity transformation, θ is the rotation angle of the infrared image to be registered relative to the visible image, s is the scaling factor and tx and ty are the translation distances of the infrared image to be registered relative to the visible image in the x and y directions, respectively. The similarity transformation preserves the overall shape features of the image, achieving rough alignment by optimizing these parameters. This transformation based on the overall structure avoids the instability brought about by the direct reliance on local feature points. The second step introduces a more flexible affine transformation model for precise registration, which can be represented as:

where Ta is the affine transformation matrix, a11 and a22 are the scaling factors of the infrared image to be registered in the x and y directions, used to adjust the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the infrared image to match the reference visible image, and a12 and a21 are the shear transformation coefficients of the infrared image to be registered, used to correct nonlinear deformations. In particular, we introduced a spatial reference mechanism, maintaining the position and scale information of the image in the world coordinate system through the imref2D function, ensuring the accuracy of the transformation process. At the same time, by setting reasonable edge filling values and enabling edge smoothing processing, we effectively solved the boundary problems in the transformation process.

Complementary Modal Feature Representation

This section describes the feature representation framework designed for the characteristics of Jiandu infrared-visible images. Visible images of Jiandu reflect mainly material texture and color information, showing a globally uniform distribution. In contrast, infrared images focus on displaying ink distribution, presenting as discrete local high-contrast areas. Based on this difference, we adopt modality-specific feature extraction strategies. The initial feature extraction for infrared and visible images uses the same model, constructing a cascade feature extraction network from shallow to deep layers. First, two convolutional layers extract low-level texture features, followed by three feature extraction blocks that progressively expand feature channels to 64, 128, and 256, achieving multi-scale representation from local texture to global structure. Finally, different attention mechanisms are designed for infrared and visible images to enhance their unique visual features.

Figure 4 shows the architecture of the feature extraction network. The network consists of consecutive convolutional and max-pooling layers. The dimensions of the feature map decrease from [224, 224, 64] to [14, 14, 512] as we progress from ϕ1(f) to ϕ5(f), while the number of channels gradually increases. This structure completes the transition from local details to global semantics. Figure 5 shows the feature extraction effect for the two modal images. Below the original infrared and visible images are the feature maps of ϕ1(f) to ϕ5(f). The shallow feature maps ϕ1(f) and ϕ2(f) mainly contain the texture and shape details of the bamboo surface, showing a uniform distribution; deep feature maps ϕ4(f) and ϕ5(f) preserve more semantic structural information.

For visible images, RGB images are first converted to YCbCr space, with features primarily extracted from the Y channel (luminance component). Chrominance components are incorporated during the subsequent fusion process to ensure color preservation. In the Y channel of visible images, Jiandu material texture information appears as response patterns distributed across the global range of feature maps, rather than being localized to specific spatial positions. Therefore, a CAM is introduced to enhance the network’s capability in expressing texture features. As shown in Fig. 6, the CAM first compresses deep feature maps F ∈ RC×H×W into global statistical information z ∈ RC×1×1 using adaptive average pooling, effectively aggregating the global brightness distribution for each channel. Subsequently, a dimensionality reduction-nonlinearity-dimensionality increase structure learns the importance relationships between channels:

where W1 and W2 are dimensionality reduction and increase weight matrices, respectively, and σ is the Sigmoid activation function. Finally, the original characteristics are adaptively enhanced through channel multiplication \(\widehat{F}=F\cdot s\).

The infrared image feature extraction module focuses on capturing ink information. It shares the same backbone network structure as the visible feature extraction network, but differs significantly in its attention mechanism design. Ink in infrared images exhibits unique distribution characteristics. Ink possesses specific absorption properties in the infrared spectrum44, creating high-contrast local areas in infrared images that distinguish itself distinctly from background material. This physical property enables inscriptions that have faded in visible images to retain significant contrast in infrared images. Unlike the global distribution of material texture in visible images, ink information in infrared images appears concentrated in discrete local regions, showing up as high response values at specific spatial locations. Based on these modality-specific distribution characteristics, we propose a SSA mechanism, as illustrated in Fig. 7.

The SSA module comprises three input transformation layers, a salient position selection block, and a feature integration layer. This design is based on self-attention principles but is specifically optimized for ink feature detection. The transformation θ (Query) projects input features onto the query vectors while maintaining the original dimension (n × D). These transformed features are subsequently used for weighted calculations with Softmax-generated attention weights, which capture structural information of ink in infrared images. The transformation ϕ (Key) projects the input features into key vectors with reduced dimensions (n × D/4) to lower computational complexity and sends its output directly to SSABlock for the selection of the dominant position, identifying key spatial locations containing information on the ink. The transformation V (value) projects input features onto value vectors with dimensions (n/4 × D), which carry content information to be combined with attention weights and the output of the G module in subsequent processing steps, generating improved feature representations.

The SSA Block localizes ink regions by computing a saliency score for each position in the feature map. For input features F ∈ R(B×N×C) (where B represents batch size, N represents the number of spatial positions, and C represents the number of channels), the saliency score is calculated by squaring feature values and then summing across all channels:

Using the saliency score S, a top k operation selects the k positions with the highest response values as key positions, allowing the precise localization of ink regions. Enhanced features are then generated through feature transformation and attention weighting mechanisms:

where A denotes the attention weight matrix, and ϕ(⋅) represents the key position feature transformation function, which projects features from selected key positions into the attention space. θ(⋅) represents the global feature transformation function, mapping all input features to a unified feature space for attention weight calculation, and Fk represents the features at the selected key positions. The final output features are computed as:

where W represents a learnable transformation matrix, g(⋅) represents the post-attention feature transformation function that further processes attention-weighted features to generate the final output, BN denotes batch normalization, and the enhanced features are ultimately obtained through residual connections.

Multi-scale information measurement

To accurately evaluate the information content of features from different modalities and at different scales, this section proposes a gradient-based multi-dimensional information measurement method. Image gradients represent the rate of change of pixel values in space and are particularly sensitive to local structural changes such as edges and textures. In deep learning frameworks, gradient computation is more efficient and requires less storage space compared to traditional information theory measures such as entropy or mutual information. This makes it more suitable for application in convolutional neural networks for feature evaluation. Considering that visible images primarily contain texture structure information, while infrared images emphasize ink information, we adopted differentiated information measurement strategies for the two modalities to more accurately assess their respective characteristics.

For the j-th layer feature map ϕj(fvi) of the visible image, a gradient measure based on the Frobenius norm is defined as follows:

where Hj, Wj, and Dj represent the height, width, and number of channels of the feature map, respectively, φj(fvi) represents the feature map of the convolutional layer before the j-th maximum pooling layer, k represents the k-th channel of the channels Dj, ∣∣⋅∣∣F represents the Frobenius norm and ∇ represents the gradient operator. When applied to gradient matrices, the Frobenius norm comprehensively captures the magnitude of changes in various directions, making it suitable for detecting texture structures distributed across multiple directions in visible images.

For infrared images, the ink information appears as discrete local high-contrast regions in space, exhibiting clear low-rank properties. The nuclear norm can effectively capture this low-rank structure, making it more suitable for characterizing the spatial distribution of ink features. To highlight ink information in infrared images and suppress background interference, we define the information measurement by combining the nuclear norm with the salient attention mechanism:

where \({g}_{j}^{ir}({f}_{ir})\) is the information content of the j-th layer feature map \({\varphi }_{j}^{k}({f}_{ir})\) of the Jiandu infrared image, Aj is the attention weight matrix of the j-th layer, and ⊙ represents element-wise multiplication. The total information content of the image is obtained by a weighted combination of features across all levels:

where αj is a weight coefficient that balances features at different levels.

Adaptive feature importance evaluation

Based on the modality-specific information measurements described above, this section presents an adaptive feature importance evaluation mechanism. Addressing the challenge of limited labeled data in Jiandu image fusion, the proposed adaptive mechanism evaluates the importance of features in source images and dynamically adjusts fusion weights based on image content. For each layer of features, their importance weights are calculated as follows:

where c is a scaling factor controlling the smoothness of the weight distribution. When a region in the image contains more valuable information, the corresponding weight automatically increases, ensuring that this information is adequately preserved during the fusion process. For infrared features, since they incorporate salient attention information, their weight calculation tends to preserve features in ink regions. The final feature importance weights are obtained through normalization:

The weights ωvi and ωir, derived through adaptive feature importance evaluation, are directly applied in subsequent loss functions to control the degree of information preservation from each source image during fusion. When the visible image contains more effective information, ωvi increases, preserving more texture details from the visible image in the fusion result. In contrast, when the ink information in the infrared image is more significant, ωir increases, resulting in a fusion that emphasizes the ink information more prominently. By evaluating information content purely based on the features themselves, this mechanism eliminates the need for labeled data, addressing the lack of standard fusion images in the Jiandu image fusion domain.

Loss function

A multi-objective loss function is designed to optimize the network by balancing structural information and pixel-level reconstruction quality, and is defined as:

where λ is a balancing coefficient that controls the trade-off between structural preservation and pixel-level accuracy.

The loss of structural similarity aims to maintain consistency in structural features between the fused image and the source images. By calculating the structural similarity between the fused image If and the visible image Ivi and infrared image Iir, and incorporating adaptive weight coefficients, the loss function is defined as:

where F represents the fused image, vi denotes the visible image ir denotes the infrared image and SSIM is defined as:

where μx and μy represent the mean pixel values in the local window, σx and σy represent the standard deviations, σxy represents the covariance and C1 and C2 are constants. The weight coefficients ωvi and ωir are derived from the adaptive characteristic importance evaluation mechanism described in the previous subsection. The mean squared error loss ensures the reconstruction quality of the fused image at the pixel level:

This loss function design based on adaptive weights allows the fusion process to take into account both structural information preservation and pixel reconstruction, effectively guiding the network to generate high-quality fusion images.

Fusion network

After determining the feature extraction and information measurement strategies, effective fusion of features from different modalities becomes a critical component. This section describes the proposed adaptive feature fusion network architecture based on dense connections which corresponds to the Fusion Block and Reconstruction block components in the overall framework Fig. 2, and its overall structure is shown in Fig. 8. The network comprises source image processing, multi-level feature fusion and image reconstruction modules, achieving adaptive fusion of Jiandu infrared and visible images from end to end.

To fully utilize the multi-level features provided by the feature extractor, we design a hierarchical feature fusion mechanism. First, 1 × 1 convolutional layers unify feature dimensions at each level, ensuring that features from different levels can be effectively integrated; next, features from all levels are concatenated with source image features along the channel dimension, constructing multi-scale feature representations:

As shown in Fig. 8, the concatenated features undergo deep fusion through three consecutive ResBlocks. Each structure adopts a residual learning architecture, with residual connections that ensure effective information flow and mitigate gradient vanishing/explosion problems45 in deep networks; multiple convolutional and non-linear transformations enhance the depth of feature fusion, improving the network’s ability to express complex features; the application of BatchNorm layers improves training stability and convergence speed. After completing deep fusion of multi-level features, the final fusion image is generated through the reconstruction network. As shown on the right side of Fig. 8, the reconstruction network consists of two parts: Reconstruction Layers (RL) and Detail Enhancement (DE). The reconstruction layers include multiple convolutional layers, with channel numbers gradually reducing from 256 to 3, each followed by BatchNorm and LeakyReLU activation functions. The detail enhancement part further processes the features and generates the fusion image If through Tanh activation in the final layer, normalizing the output.

To maintain brightness consistency between fusion results and visible images while incorporating ink information from infrared images, we designed a Brightness Constraint Module (BC). The BC module operates at the final reconstruction stage, positioned at the rightmost end of the Reconstruction block in Fig. 8, where it integrates with the Detail Enhancement output via element-wise addition. This module computes the mean squared error between the brightness components of the fused and visible images:

where Y(⋅) represents the operation to extract the brightness component of the image. By adjusting this constraint, we ensure that the fusion image maintains a natural brightness distribution, avoiding brightness distortion caused by excessive incorporation of infrared information, resulting in better visual quality while preserving ink information.

Unlike traditional fusion methods, the proposed end-to-end learning network does not require manually designed fusion rules, but instead provides an effective solution for high-quality fusion of Jiandu images through adaptive feature evaluation and multi-scale feature fusion, achieving balanced representation of ink information and material texture.

Results

In this section, we verify the effectiveness of the proposed model for Jiandu infrared-visible image fusion through a series of experiments. First, we introduce the Jiandu infrared-visible image dataset that we constructed and its development process. Next, we detail the experimental settings and evaluation metrics, comparing our method with existing approaches to demonstrate its superiority. Finally, we analyze the contribution of each module through ablation studies.

Construction of Jiandu infrared-visible image dataset

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method in Jiandu image fusion, this section presents a data set specifically constructed for Jiandu infrared-visible image fusion based on the proposed STAIR registration algorithm. Significant unearthed documents, such as Han Dynasty Wooden Slips Unearthed from Diwan, New Juyan Bamboo Slips, Han Dynasty Wooden Slips from Majuanwan, Xuanquan Han Slips, and Han Dynasty Wooden Slips from Yumen Pass, providing a reliable foundation for unsupervised Jiandu image fusion research.

During data collection, we implemented a standardized digital imaging protocol. For infrared image acquisition, we used a 940 nm wavelength light source and a professional cultural relic infrared imaging system, which ensured optimal visualization of ink features. Visible images were captured under standard D65 light sources, ensuring accurate color reproduction. All images were collected at a 300dpi resolution to capture fine textures and ink details on the Jiandu surface.

The data set comprises 2175 pairs of high-quality registered images, which were processed through a consistent pre-processing workflow. The preprocessing steps included: initially correcting the original images to eliminate lens distortion and uneven illumination effects; then applying a non-local means filtering algorithm to reduce noise while preserving detailed textures; and finally utilizing the STAIR algorithm to achieve pixel-level precise registration, ensuring strict spatial correspondence between infrared and visible images.

Experimental setup

All experiments were conducted on a server equipped with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Silver 4210 CPU @ 2.20 GHz processor and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU. The method was implemented using the PyTorch framework.

Ablation experiments

To comprehensively assess the performance of the proposed method, this study adopts multiple objective evaluation metrics. Given the unsupervised nature of the Jiandu image fusion task, an ideal ‘ground truth’ image does not exist in reality. Therefore, all reference-based evaluation metrics, such as CC, PSNR, and SSIM, use the input source images (i.e., the original visible and infrared images) as references. This approach aims to quantify the degree to which the fusion result preserves information from both modalities, respectively. Following this framework, CC is used to measure the correlation between the fused image and the source images; PSNR reflects the quality of the reconstructed image; SSIM46 evaluates the degree of structural preservation; MI47 measures the ability of the fused image to retain information from the original images; SD measures the image contrast level; and DeltaE48 quantifies the color difference between the result of the fusion and the original visible image, with a smaller value indicating less color distortion. These multidimensional metrics together form a comprehensive evaluation system that reflects the quality of fusion results from different angles.

The brightness constraint mechanism aims to ensure that the brightness distribution of the fused image remains consistent with that of the original visible image. As shown in Fig. 9, we tested the impact of different weight configurations on the fusion results. When the constraint range is 0.85-1.15, the model achieves the best balance between multiple evaluation metrics. This configuration achieves a visible CCvi of 0.7536 and an infrared CCir of 0.7830, indicating that the fusion result maintains a high correlation with both source images. In terms of PSNR, SSIM, and MI, the 0.85–1.15 configuration performs excellently. Particularly in SD and Delta E, this configuration has a SD value of 40.5065, maintaining an appropriate image contrast, while the color difference is only 20.8214, far lower than other configurations, proving its advantage in maintaining original color characteristics. Experiments show that a constraint range that is too small (like 0.95–1.05), while maintaining high brightness consistency, would limit the extraction of infrared features, whereas a constraint range that is too large (like 0.7–1.3) might lead to brightness distribution distortion. The 0.85–1.15 constraint range achieves the best balance between maintaining brightness consistency and feature extraction.

The SSA module represents the core innovation of our method, where the k-value (number of selected key positions) serves as a critical parameter determining its performance. Figure 10 demonstrates that fusion performance improves significantly as k increases from 5 to 8. At k = 5, the infrared correlation coefficient CCir equals 0.120, indicating extremely limited network capability for infrared feature extraction. When k = 8, this metric increases substantially to 0.7830.

SSIM increases steadily with the k value, reaching 0.7249 for visible images and 0.3365 for infrared images at k = 8. SD achieves the highest value of 58.51, while Delta E drops to the lowest point of 20.8214, indicating that this configuration can maintain color fidelity while preserving richer information. When the value k increases further to 9 or 10, due to the introduction of too many background region features that interfere with the accurate extraction of ink regions, performance improvement tends to plateau or decline. Taking into account both computational efficiency and fusion performance, k = 8 is the optimal choice.

To evaluate the impact of MSE loss weight λ on fusion effects, we conducted comparative experiments with different λ values. We tested five configurations ranging from λ = 18 to λ = 22.

The model achieves the best performance on multiple key metrics when λ is 20. As shown in Fig. 11, in terms of SSIM, the infrared and visible metrics are 0.7249 and 0.3265, respectively, the highest among all configurations. It also shows clear advantages in color reproduction. Although λ = 21 has slight advantages in some visible-related metrics, considering all metrics, especially the balance between infrared and visible features, λ = 20 is the reasonable optimal choice.

Three different norm usage schemes were designed to verify the contribution of differentiated norm selection to fusion effects: both modalities using the Frobenius norm; visible features using the Frobenius norm and infrared features using the nuclear norm (the proposed approach); and both modalities using the nuclear norm.

The differentiated norm strategy achieves the best balance in multiple metrics. As illustrated in Fig. 12, although the all Frobenius norm scheme scores slightly higher in visible CCvi, the differentiated norm reaches 0.7830 in infrared CCir, higher than other schemes. In terms of PSNRvi and SSIMvi, the differentiated norm strategy reaches 29.1756 and 0.7249, respectively, performing best. In particular, in Delta E, the differentiated norm strategy is only 20.8214, much lower than other schemes, proving its superiority in maintaining the original color characteristics. These results demonstrate that adopting a differentiated norm calculation strategy for different modal images is reasonable and effective, fully utilizing the complementary characteristics of the two modal images to achieve a more balanced fusion effect.

To validate the choice of YCbCr color space in our method, we conducted comparative experiments across three color space processing strategies for visible images. These included the L channel from Lab space, the V channel from HSV space, and the Y channel from YCbCr space. For each strategy, the three-channel visible image was converted to a single-channel representation to match the infrared modality, with all other parameters held constant to ensure a fair comparison.

As demonstrated in Table 1, the quantitative results confirm that the YCbCr-based approach achieves the best overall performance. Our method consistently outperforms the others in key metrics related to information retention and fidelity to the source images, such as CC, SSIM, and MI. Critically, it shows a distinct advantage in the two areas most pertinent to the practical goals of Jiandu research. It achieves the highest color fidelity with the lowest Delta E value and ensures robust contrast for ink legibility with the strongest SD value.

The superior performance of YCbCr can be attributed to its effective separation of luminance and chrominance information. The Y channel encapsulates the brightness variations corresponding to the material texture and ink traces, allowing our fusion network to precisely target these features for enhancement. Concurrently, the Cb and Cr channels preserve the original color information, which is seamlessly reintegrated during the reconstruction phase. This architectural choice facilitates the precise processing of texture and contrast while ensuring maximum color fidelity. These results validate that the YCbCr color space provides an optimal balance between texture preservation, contrast enhancement, and color fidelity for the application of Jiandu infrared-visible image fusion.

An ablation experiment was conducted on the SSA module to verify the effectiveness of the SSA mechanism in the infrared feature extraction process. The spatial attention module was removed from the infrared feature extractor and replaced with a feature enhancement module consisting of ordinary 1 × 1 convolutional layers, batch normalization, and ReLU activation functions.

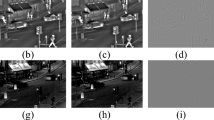

Figure 13 shows that the fusion image exhibits significant degradation in ink information preservation after the SSA module is removed, especially in the areas marked by red boxes. The ordinary feature enhancement module cannot accurately capture key ink information, resulting in blurred strokes, reduced edge clarity, and compromised readability of text on slips.

The quantitative evaluation results shown in Table 2 indicate that after removing the SSA module, the model exhibits a significant decline in metrics such as SSIM, PSNR and SD, confirming the critical contribution of the SSA module to fusion quality improvement.

To validate the effectiveness of varying scale layer numbers in the proposed multi-scale information measurement strategy, this section conducts ablation experiments focusing on this key parameter. Modifying the network structure could significantly impact the model’s feature representation capacity, parameter optimization process, and module dimensional matching relationships, potentially compromising the fairness and scientific validity of ablation studies. To address this, the experimental design keeps the feature extraction network architecture unchanged, retaining the original five-layer structure to ensure consistent feature information is passed to the CAM and SSA modules. Fixing the network architecture allows for a focused evaluation of how varying scale layer numbers in the multi-scale information measurement strategy influence the final fusion quality.

The feature extraction network outputs five scale feature maps (ϕ1 to ϕ5), with dimensions progressively decreasing from [224 × 224 × 64] to [14 × 14 × 512]. This experiment focuses on evaluating how varying the number of scale layers used for weighted combination calculations in the multi-scale information measurement process affects fusion performance. As shown in Fig. 14, five configurations ranging from 3-scale to 7-scale layers are evaluated, with the 5-scale configuration representing the standard setting of the proposed method. The 6-scale and 7-scale configurations are exploratory extensions of the five-layer feature foundation, designed to verify whether additional scale layers improve information measurement precision.

Visual analysis shows that the 3-scale configuration for information measurement involves limited feature participation, resulting in insufficient precision when evaluating texture distribution in visible images and ink intensity in infrared images. Consequently, the fusion results exhibit low ink contrast and poor material texture preservation. The 4-scale configuration improves measurement accuracy, but inaccuracies persist when handling complex ink degradation regions, especially in critical areas marked by red boxes where ink extraction remains suboptimal.

The standard 5-scale configuration achieves optimal information measurement precision. By simultaneously utilizing the complete information gradient, from shallow texture features to deep semantic features, it accurately performs multi-scale weighted combination, providing robust foundational data for adaptive feature importance evaluation. This configuration ensures accurate measurement of globally distributed material textures in visible images and precise capture of locally distributed, high-contrast ink details in infrared images. Experimental results show that with this configuration, fused images greatly enhance ink clarity and readability while preserving the natural textures of bamboo slip materials.

Extending to 6-scale and 7-scale configurations for information measurement yields slight improvements in certain detail regions, but overall performance enhancement saturates. This result suggests that configurations exceeding the 5-scale setting offer no significant improvements in fusion quality. Additional scale layers may introduce redundant information during adaptive weight calculations, reducing allocation accuracy and negatively impacting weight optimization in the loss function.

From the perspective of computational efficiency, increasing the number of measurement scale layers has minimal impact on overall computational complexity, but diminishing returns render such extensions practically meaningless. Comprehensive analysis confirms that using five scale layers for multiscale information measurement is the most reasonable strategy for this method. This configuration fully leverages the multi-level feature information provided by the original network architecture, achieving an optimal balance among information measurement precision, adaptive weight optimization, and computational efficiency. It provides robust technical support for the dual objectives of ink enhancement and material texture preservation in Jiandu infrared-visible image fusion.

The ablation experiments validate the effectiveness of key components in our proposed method and establish optimal parameter configurations. Results demonstrate that five components are essential for improving infrared-visible image fusion performance: the SSA module with optimal k-value selection, appropriate MSE loss weighting, scale layer impact analysis, differentiated normalization strategy, and the brightness constraint Module. These components synergistically exploit the complementary characteristics of infrared and visible images, achieving improved fusion balance.

Comparative experiments

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed method, we conducted comprehensive comparisons with seven established image fusion techniques.These methods include DifFusion42, DenseFuse28, SeAFusion31, PiAFusion32, MaeFuse49, CrossFuse40, and U2Fusion34. The primary objective was to assess method performance on ancient slip infrared-visible image datasets, with particular emphasis on preserving inscription information and maintaining overall fusion quality. Inscription information in ancient slip images is particularly significant. Maintaining inscription clarity during fusion while achieving harmonious integration with bamboo slip material details represents the central challenge of this research.

Figures 15 and 16 show that the proposed method outperforms other methods in detail preservation and inscription information fusion. Visible images display the material texture and natural color of Jiandu, but inscriptions often appear blurred due to degradation. Infrared images highlight ink information but lack material texture and natural color. Ideal fusion results should combine the advantages of both modalities: inscription clarity and natural material texture.

Regarding overall fusion performance, the DifFusion method improves inscription readability but introduces noticeable noise in multiple samples and lacks color fidelity. DenseFuse shows insufficient contrast between inscriptions and the background, compromising readability and resulting in an overall dark appearance. SeAFusion excessively enhances image contrast, causing background texture distortion. While inscriptions appear relatively clear, the overall visual experience is unsatisfactory. PIAFusion exhibits color shifting in some samples. Despite improved inscription clarity, the overall visual effect lacks naturalness. MaeFuse performs similarly to SeAFusion and PIAFusion in terms of inscription visibility but suffers from poor color fidelity and noticeable color distortion. U2Fusion partially succeeds in balancing inscriptions and materials but struggles with instability when processing complex character forms, leading to lost details. CrossFuse performs comparably to or slightly better than U2Fusion, demonstrating good inscription clarity and texture preservation. However, it still suffers from color distortion and fails to effectively maintain the natural color of bamboo slips. Compared to other methods, the proposed method enhances inscription clarity and readability while preserving the natural texture of bamboo slip materials. Particularly in severely degraded ink regions, the method restores inscription details more effectively while avoiding excessive background texture sharpening. The fusion results exhibit natural color balance, moderate contrast, and clear inscription edges without noticeable noise, demonstrating excellent adaptability across samples with varying preservation states.

Figure 17 illustrates the cumulative distribution curves of various evaluation metrics for different fusion methods in the test data set. This representation method more comprehensively reflects the performance distribution of algorithms compared to single average values. In terms of CC, the proposed method maintains a relatively high position across most cumulative probability intervals, with particular advantages in the range of 0.4–0.8. The PSNR distribution indicates that as sample difficulty increases, the proposed method consistently maintains high performance levels and exhibits superior robustness when processing challenging samples.

In the cumulative distribution of SSIM, the proposed method and DenseFuse lead in most intervals, demonstrating advantages in structural preservation. With respect to MI, the proposed method performs excellently in metrics related to visible image features. Notably, in the SD distribution, our method’s curve significantly exceeds all comparison methods, including CrossFuse, demonstrating consistent contrast enhancement across the entire dataset. The DeltaE distribution confirms the advantage of the proposed method in maintaining original color fidelity.

The average quantitative evaluation results of each method on the test dataset are presented in Table 3. The proposed method achieves 0.9105 in correlation with visible images CCvi, second only to DenseFuse; in PSNR metrics, it reaches 29.0154 (visible) and 29.0632 (infrared), demonstrating excellent overall performance. In terms of SSIM, it reaches 0.7658 for visible images, second only to DenseFuse; in MI, it reaches 1.2763 for visible images, achieving the highest value among all methods. The SD is particularly noteworthy, where the proposed method reaches 72.7627, significantly higher than all comparison methods, including CrossFuse (68.6475), indicating that the fusion results possess enhanced contrast and clarity. In Delta E, the value is only 21.8470, considerably lower than other methods, which confirms superior color fidelity. As shown in Table 4, the proposed method uses 14.84M parameters and requires 22.5 GFLOPs. Although not the most lightweight, it maintains a practical balance between model size and performance. The average inference time is 124.2 ms, which remains acceptable for heritage imaging tasks where detail preservation outweighs real-time speed.

Combining qualitative and quantitative analyzes clearly demonstrates that the adaptive fusion method based on SSA proposed in this paper achieves significant advantages in two key objectives: enhancing inscription information and naturally integrating material texture. This provides more effective technical support for the digital preservation and research of ancient slips.

To further illustrate the practical effectiveness and robustness of our method, Fig. 18 presents a series of fusion results on samples that encompass a spectrum of real-world degradation scenarios, including varied and potentially non-uniform lighting conditions. The figure is organized to show the source infrared images (top row), the corresponding visible images (middle row), and our final fused results (bottom row). The samples are arranged from left to right to demonstrate the method’s performance across a progression of challenges: from partially faded inscriptions, to completely faded text, and finally to the most challenging cases of severely damaged characters on physically compromised slips. It is visually evident that our method consistently produces a fused image that enhances textual clarity. For partially or completely faded text, our method effectively integrates the ink information from the infrared channel into the visible context, significantly improving legibility. Even in the most extreme cases on the right, where concurrent inscription and material damage are severe, the fused result, while not a perfect restoration, still offers a marked improvement in the interpretability of the fragmented characters compared to either source image alone. This series of results validates the robustness of our approach in addressing the diverse range of conditions encountered in Jiandu artifacts.

The figure compares the source infrared images (Top Row) and visible images (Middle Row) with our fused results (Bottom Row). The ten samples in each row are arranged from left to right to show a progression of challenges under varied lighting conditions: partially faded inscriptions, completely faded inscriptions, and finally, severely damaged inscriptions on physically compromised slips.

Discussion

This paper presents an adaptive fusion method for Jiandu infrared-visible images based on SSA, marking the first application of image fusion technology for enhancing ink information on this specific type of cultural heritage. The proposed method addresses the dual challenge of preserving ink clarity from infrared images and material texture from visible images. When applied to the Jiandu dataset, experimental results demonstrate that our approach outperforms several mainstream fusion techniques in both visual quality and multiple objective metrics, effectively improving ink readability while mitigating common issues such as color distortion and artifacts.

While the quantitative results validate the effectiveness of our method, its practical relevance extends across both scholarly research and public engagement. The utility for specialists is particularly evident in the critical and painstaking task of reassembling fragmented slips. This work requires scholars to meticulously cross-reference both the material texture from visible images and the textual information from infrared images50. Our proposed method directly addresses this bottleneck by producing a single, coherent image that presents all necessary visual cues in one unified view, potentially improving both the efficiency and success rate of such tasks. Furthermore, the fused image serves a broader purpose as a digital restoration, approximating the artifact’s original appearance before the ink degraded over time. This single, comprehensive representation not only streamlines scholarly analysis but is also ideal for public dissemination. It provides an intuitive and accessible view for museum exhibitions and educational materials, eliminating the need for a general audience to switch between and interpret two separate image modalities. This directly aligns our technical contribution with the dual needs of specialized research and broader cultural heritage communication.

Building on this practical validation, it is also crucial to acknowledge the limitations of the current study and define the trajectory for future research. The proposed model was specifically trained and validated on a custom dataset of Jiandu with carbon-based inks. This focused approach, while effective for the target problem, underscores the specialized nature of our method. Its extension to other contexts is not straightforward, primarily due to data availability and methodological mismatches. Common public infrared-visible fusion datasets (e.g., MSRS51, RoadScene34) are designed for disparate applications like thermal object detection and are thus unsuitable. Furthermore, our investigation into other cultural heritage datasets, such as the HYPERDOC dataset for ancient manuscripts52, revealed that artifacts with iron-gall ink often show clear text in visible light and obscured text in the near-infrared—the inverse of the problem our method is designed to solve. Therefore, a primary objective for our future work will be to formalize the connection between our metrics and expert assessment through direct collaboration, and to investigate the adaptability of our framework as more suitable datasets for other types of cultural heritage become available.

Data availability

The datasets used for experiments and evaluation in this study, including the infrared and visible image pairs of ancient bamboo and wooden slips, have been deposited in the repository at https://github.com/charlieqjz/JDSSAFusion. Sample images and experimental results are also provided in the repository, along with all necessary implementation details and algorithms described in this paper, to facilitate reproduction of our findings.

References

Yu, X.Language and State: A Theory of the Progress of Civilization 2nd edn (FriesenPress, 2021).

Allen, S. M., Zuzao, L., Xiaolan, C. & Bos, J. History and Cultural Heritage of Chinese Calligraphy, Printing and Library Work: Edited By Susan M. Allen…[Et Al.] (IFLA publications, 141) (De Gruyter, 2010).

Ge, C. A re-understanding of the Silk Road reflected by the Han slips from Xuanquan, Dunhuang. The Western Regions Studies (2), 107–113 (2017).

Zhao, G. & Jia, L. Protection and requirements in the process of bamboo slip image information collection. Excav. Lit. (1), 13–19 (2023).

Bai, G., Song, P. & Zhang, X. An overview of the application of technology for clarity extraction of fuzzy information in cultural relics. Fujian Cultural Relics and Museology (4), 91–96 (2022).

Na, Z., Lujun, C. & Xuben, W. A method for archaeological text restoration and recognition based on horizontal and vertical projection. Sci. Technol. Bull. 30, 185–187 (2014).

Jinquan, L., Na, Z. & Xuben, W. Research on bamboo slip text image processing based on threshold segmentation. Sci. Technol. Bull. 28, 128–129+132 (2012).

Yangjie, Z.Application of Threshold-Based Image Segmentation Technology in Bamboo Slips. Master’s thesis, Chengdu University of Technology (2010).

Liuyan, W. & Xuben, W. Application of multi-scale retinex algorithm in bamboo slip image enhancement. Comput. Sci. 36, 288–290 (2009).

Zhang, W., Wang, X. & Jin, P. Application of Canny edge operator in bamboo slip text restoration. Microcomp. Inf. (9), 241–242 (2008).

Qin, Q., Wang, X. & Jiang, W. Application of unsharp masking method in bamboo slip text enhancement. Microcomp. Inf. (3), 241–242 (2008).

Na, Z.Research on Bamboo Slip Image Enhancement and Segmentation. Master’s thesis, Chengdu University of Technology (2007).

Li, S., Kang, X., Fang, L., Hu, J. & Yin, H. Pixel-level image fusion: a survey of the state of the art. Inf. Fusion 33, 100–112 (2017).

Li, H., Wu, X.-J. & Kittler, J. Mdlatlrr: a novel decomposition method for infrared and visible image fusion. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 29, 4733–4746 (2020).

Chen, J., Li, X., Luo, L., Mei, X. & Ma, J. Infrared and visible image fusion based on target-enhanced multiscale transform decomposition. Inf. Sci. 508, 64–78 (2020).

Liu, Y., Jin, J., Wang, Q., Shen, Y. & Dong, X. Region level based multi-focus image fusion using quaternion wavelet and normalized cut. Signal Process. 97, 9–30 (2014).

Bavirisetti, D. P. & Dhuli, R. Two-scale image fusion of visible and infrared images using saliency detection. Infrared Phys. Technol. 76, 52–64 (2016).

Li, S., Yin, H. & Fang, L. Remote sensing image fusion via sparse representations over learned dictionaries. IEEE Trans. Geosci. remote Sens. 51, 4779–4789 (2013).

Liu, Y., Chen, X., Ward, R. K. & Wang, Z. J. Image fusion with convolutional sparse representation. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 23, 1882–1886 (2016).

Cvejic, N., Lewis, J., Bull, D. & Canagarajah, N. Region-based multimodal image fusion using ica bases. In Proc. International Conference on Image Processing, 1801–1804 (IEEE, 2006).

Li, H., Liu, L., Huang, W. & Yue, C. An improved fusion algorithm for infrared and visible images based on multi-scale transform. Infrared Phys. Technol. 74, 28–37 (2016).

Ma, J., Chen, C., Li, C. & Huang, J. Infrared and visible image fusion via gradient transfer and total variation minimization. Inf. Fusion 31, 100–109 (2016).

Ma, J., Zhou, Z., Wang, B. & Zong, H. Infrared and visible image fusion based on visual saliency map and weighted least square optimization. Infrared Phys. Technol. 82, 8–17 (2017).

Hou, R. et al. Infrared and visible images fusion using visual saliency and optimized spiking cortical model in non-subsampled shearlet transform domain. Multimed. Tools Appl. 78, 28609–28632 (2019).

Zhang, H., Xu, H., Tian, X., Jiang, J. & Ma, J. Image fusion meets deep learning: a survey and perspective. Inf. Fusion 76, 323–336 (2021).

Li, H., Wu, X.-J. & Kittler, J. Rfn-nest: An end-to-end residual fusion network for infrared and visible images. Inf. Fusion 73, 72–86 (2021).

Ram Prabhakar, K., Sai Srikar, V. & Venkatesh Babu, R. Deepfuse: a deep unsupervised approach for exposure fusion with extreme exposure image pairs. In Proc. IEEE International Conference On Computer Vision 4714–4722 (2017).

Li, H. & Wu, X.-J. Densefuse: a fusion approach to infrared and visible images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 28, 2614–2623 (2019).

Li, H., Wu, X.-J. & Durrani, T. S. Nestfuse: an infrared and visible image fusion architecture based on nest connection and spatial/channel attention models. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 69, 9645–9656 (2020).

Zhang, H., Xu, H., Xiao, Y., Guo, X. & Ma, J. Rethinking the image fusion: a fast unified image fusion network based on proportional maintenance of gradient and intensity. In Proc. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 12797–12804 (AAAI, 2020).

Tang, L., Yuan, J. & Ma, J. Image fusion in the loop of high-level vision tasks: a semantic-aware real-time infrared and visible image fusion network. Inf. Fusion 82, 28–42 (2022).

Tang, L., Yuan, J., Zhang, H., Jiang, X. & Ma, J. Piafusion: a progressive infrared and visible image fusion network based on illumination aware. Inf. Fusion 83, 79–92 (2022).

Ma, J., Tang, L., Xu, M., Zhang, H. & Xia, G. Stdfusionnet: an infrared and visible image fusion network based on salient target detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 70, 1–13 (2021).

Xu, H., Ma, J., Jiang, J., Guo, X. & Ling, H. U2fusion: a unified unsupervised image fusion network. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44, 502–518 (2020).

Ma, J., Yu, W., Liang, P., Li, C. & Jiang, J. Fusiongan: a generative adversarial network for infrared and visible image fusion. Inf. Fusion 48, 11–26 (2019).

Ma, J., Xu, H., Jiang, J., Mei, X. & Zhang, X.-P. Ddcgan: a dual-discriminator conditional generative adversarial network for multi-resolution image fusion. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 29, 4980–4995 (2020).

Tang, W., Yang, S., Niu, Y. & Sun, Z. Attentionfgan: infrared and visible image fusion using attention-based generative adversarial networks. Inf. Fusion 67, 88–100 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Ifcnn: a general image fusion framework based on convolutional neural network. Inf. Fusion 54, 99–118 (2020).

Li, W., Zhang, Y., Wang, G., Lu, W. & Gao, F. Dfenet: a dual-branch feature enhanced network integrating transformers and convolutional feature learning for multimodal medical image fusion. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 80, 104402 (2023).

Li, H. & Wu, X.-J. Crossfuse: a novel cross attention mechanism based infrared and visible image fusion approach. Inf. Fusion 103, 102147 (2024).

Zhao, Z. et al. Ddfm: denoising diffusion model for multi-modality image fusion. In Proc. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 8082–8093 (IEEE, 2023).

Yue, J., Fang, L., Xia, S., Deng, Y. & Ma, J. Dif-fusion: toward high color fidelity in infrared and visible image fusion with diffusion models. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 32, 5705–5720 (2023).

Yang, B. et al. Lfdt-fusion: a latent feature-guided diffusion transformer model for general image fusion. Inf. Fusion 113, 102639 (2025).

Xue, L., Meng-lei, W., Yuan, L. & Yi-chen, Z. Nondestructive techniques in the research and preservation of cultural relics. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 38, 2026–2031 (2018).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proc. IEEE Conference On Computer Vision And Pattern Recognition 770–778 (IEEE, 2016).

Wang, Z., Bovik, A. C., Sheikh, H. R. & Simoncelli, E. P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 13, 600–612 (2004).

Qu, G., Zhang, D. & Yan, P. Information measure for performance of image fusion. Electron. Lett. 38, 313–315 (2002).

Sharma, G., Wu, W. & Dalal, E. N. The ciede2000 color-difference formula: Implementation notes, supplementary test data, and mathematical observations. Color Res. Appl. 30, 21–30 (2005).

Li, J., Jiang, J., Liang, P., Ma, J. & Nie, L. Maefuse: Transferring omni features with pretrained masked autoencoders for infrared and visible image fusion via guided training. In Proc. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing (IEEE, 2025).

Yao, L. A study on the rejoining and interpretation of the new Juyan slips. Huaxia Archaeol. 154–160 (2023).

Tang, L., Li, C. & Ma, J. Mask-difuser: a masked diffusion model for unified unsupervised image fusion. In Proc. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 1–18 (IEEE, 2025).

López-Baldomero, A. B. et al. Hyperspectral dataset of historical documents and mock-ups from 400 to 1700 nm (hyperdoc). Sci. Data 12, 1248 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Gansu Province 2023 Key Talent Project (Grant No. 2023010) and the Innovation Fund Project for Higher Education Institutions in Gansu Province (Grant No. 2025A-004). The funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Q. performed data curation, conducted analysis and experiments, handled validation, and contributed to manuscript writing. Q.Z. provided supervision, acquired funding, and contributed to project administration and manuscript review and editing. Y.Q. contributed to manuscript writing, review and editing, project administration, and funding acquisition. T.W. and S.C. contributed to manuscript review and editing. L.Y. restructured and polished the manuscript, performed data curation and analysis, and handled experimental validation. C.W. conducted analysis. X.Z. performed data curation. J.H. and F.Q. conducted data collection. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Q., Qin, J., Qi, Y. et al. SSA-based adaptive infrared-visible image fusion for ink enhancement in ancient bamboo slips. npj Herit. Sci. 14, 25 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02293-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02293-7