Abstract

Cave-air CO₂, one of the key indicators of cave ecosystem stability and human disturbance, plays a significant role in regional carbon cycles but has long been overlooked. Existing studies have primarily focused on cave resource development and restoration, resulting in an insufficient understanding of tourism-induced CO₂ dynamics. This study conducted high-resolution monitoring in Jiutian Cave (northern China) for the first time and integrated tourist data. The results showed that the air CO₂ concentration in Jiutian Cave was lower during summer-autumn and winter-spring, with soil CO₂ identified as the primary carbon source. However, tourism activities disrupted the synergistic relationship between soil CO₂ and cave-air CO₂, causing pulsed increases in cave-air CO₂ concentration. From the perspective of cave resilience, factors such as the duration of tourist visits, the structural characteristics of different internal cave regions, and ventilation status all influence the recovery rate of cave-air CO₂ concentration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to the relatively enclosed environment of caves, CO₂ concentrations in cave air are typically higher than those in the external atmosphere. Through ventilation effects, storage effects, and accumulation processes, cave systems actively regulate carbon cycling within the Earth’s surface system, significantly impacting regional carbon budgets and overall carbon balance1,2,3,4. In general, the more developed a cave is, the larger the available space for CO₂ storage, and the greater the amount of CO₂ that can be regulated5. This significantly impacts the regional carbon cycle. The concentration of cave-air CO₂ serves as a critical indicator of subterranean environmental changes, directly influencing the growth of secondary chemical deposits (e.g., speleothems) and altering cave landscapes. Karst secondary speleothems—particularly stalagmites—are globally widespread, environmentally sensitive, and precisely datable, making them exceptional archives of paleoclimate information6,7,8,9.

Relevant studies have demonstrated that soil CO2 is the primary source of air CO2 in most caves. Gaseous CO2 can be stored in soil fissures and pores10,11,12, and it is primarily transported or diffused into caves through these pores and fractures3,13,14. Additionally, environmental changes such as variations in vegetation and climate can influence the migration of soil CO₂, thereby affecting the characteristics and fluctuations of CO₂ in cave air15. Relevant studies indicate that ventilation effects are one of the primary mechanisms governing the dynamics of CO₂ concentration in cave air16,17,18,19. De Freitas et al. (1982)16 argued that the reversal of airflow between caves and the outside environment is primarily influenced by differences in air density, which are caused by variations in temperature, pressure, and relative humidity20. When continuous ventilation occurs in a cave, it promotes the exchange of air between the cave, which has a high CO₂ concentration, and the external atmosphere, which has a low CO₂ concentration2,21,22, and modifies the CO₂ concentration and its dynamic variations in cave air19,23. Numerous studies have examined the relationship between cave ventilation and cave-air CO₂ concentration24. However, due to the complexity and uniqueness of each cave’s structure, as well as varying meteorological conditions25, the ventilation status differs among various caves.

With the development of cave landscape resources, tourism activities have become a significant factor influencing cave-air CO₂ concentrations. Both the number of tourists and the duration of their visits substantially affect the cave-air CO₂ concentration. Studies by Baldini et al. (2008)23 and Lang et al. (2015)26 have indicated that tourist activities can cause the concentration of cave-air CO₂ to increase by an order of magnitude within a relatively short period. Specifically, during brief time frames, high-intensity tourist activities result in a substantial influx of anthropogenic CO₂, which significantly impacts the cave environment. The concentration of cave-air CO₂ peaks when the number of tourists is at its highest and subsequently decreases as air circulation resumes after the conclusion of tourist activities27,28. However, most current studies on tourist caves have concentrated on cave resources and landscape restoration29. Insufficient attention has been given to the dynamic variations in cave-air CO₂ concentrations resulting from tourist activities. Furthermore, research on how cave-air CO₂ concentrations respond to these activities, including their dynamic variation processes, abrupt concentration changes, and reduction mechanisms, remains inadequate. By utilizing high-resolution automatic monitoring technology, we systematically monitored cave-air CO₂ concentration, soil CO₂ concentration, and related meteorological parameters in Jiutian Cave, a typical tourist cave located in the temperate karst region of northern China. This study, in conjunction with tourist visitation data for Jiutian Cave, investigates the dynamic variation processes, mechanisms, and primary influencing factors of cave-air CO₂ in response to tourist activities. The findings of this research have significant scientific implications for the protection and sustainable development of tourist caves, as well as for the assessment of CO₂ budgets in karst regions.

Methods

Sampling locations and description

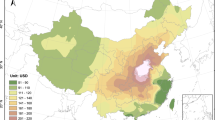

Jiutian Cave is situated at the southern base of Lushan Mountain in Zhu’a Village, Lushan Town, Yiyuan County, Zibo City, Shandong Province (118°04′E, 36°16′N) (Fig. 1). It is a notable example of a karst cave within the temperate climate zone of northern China. The area surrounding the cave experiences a semi-humid temperate climate, with an annual average temperature ranging from 12 to 13 °C. July is the warmest month, while January is the coldest. Annual average precipitation varies between 700 and 900 mm. The entrance to Jiutian Cave is located at an altitude of 475 m, positioned in an east–west trending erosional valley that is surrounded by mountains on three sides. The cave entrance is ~60 m above the valley floor30.

Jiutian Cave is a single-entry cave that generally trends nearly north–south, featuring a relatively simple passage structure consisting of a single corridor. The cave floor is predominantly flat, with slight topographic undulations. The total length of Jiutian Cave is 618 m, and the height within the cave typically ranges from 5 to 18 m. The expansive cave chambers have an average height of about 10 m and can reach a width of 20 m, while the narrower sections have both width and height measurements of <1.8 m. The total volume of the cave is ~22,000 m³. It is situated within the carbonate rock strata of the Middle Ordovician Majiagou Formation (O₂mb)31. The lithology consists of gray, thick-bedded micritic limestone, with the thickness of the limestone at the cave’s roof ranging from approximately 20 to 80 m, increasing in thickness toward the deeper sections of the cave. The thickness of the overlying soil layer outside Jiutian Cave is approximately 30–40 cm, and it features excellent vegetation coverage exceeding 90%. Most of the vegetation consists of artificial forests, primarily composed of numerous tree species and shrubs, while the soil predominantly consists of brown soil. The temperature within Jiutian Cave remains ~15 °C year-round, and the cave is abundant in secondary chemical sediments, including cave flowers, helictites, stone pillars, and moonmilk (Fig. 1c–e). These sediments encompass a variety of deposits, ranging from gravitational water deposits to non-gravitational, synergistic, and superimposed deposits, characterized by a rich diversity of types, dense distribution, and varied forms. It is a typical example of karst caves found in northern China and temperate regions, and it is also a renowned tourist attraction.

Experimental setup and data acquisition

Based on the structure and characteristics of the cave, four monitoring sites (Site 1, Site 2, Site 3, and Site 4) were selected from the entrance of the Jiutian Cave for monitoring courses (Fig. 1). The monitoring period extended from March 2023 to January 2025. At each cave monitoring site, instruments were installed to measure cave-air CO₂ concentration, relative humidity, and air temperature, with a monitoring frequency of once every 10 min. The CO₂ sensors were installed at a height of 1.3–1.5 m above the ground, positioned 5–8 m away from the tourist path. The distance from each sensor to the path varied by location: 5.5 m for the first sensor, 6 m for the second, 8 m for the third, and 8 m for the fourth. The placement of the CO₂ sensors was aligned with the tourist route, and their moderate height ensured effective capture of CO₂ emissions from tourist activities. Additionally, the four monitoring points were evenly distributed throughout the cave, eliminating the interference of spatial heterogeneity on the data and ensuring that the monitoring results accurately reflected the overall environmental conditions of the cave. Cave-air CO₂ concentration was monitored using a GMP252 probe, while temperature and relative humidity were measured with an HMT120STB transmitter (Vaisala Co. Ltd., Finland). The CO₂ sensor has a monitoring accuracy of 10 ppmv, the temperature sensor has an accuracy of 0.2 °C, and the humidity sensor has an accuracy of 2%. The electrode of the CO₂ sensor utilizes self-calibration technology, which ensures measurement accuracy and reduces maintenance costs. Given the characteristics of the cave environment, a wired transmission method was employed to relay data to the external data center, thereby enhancing the reliability of data transmission. Meanwhile, on-site calibration was conducted monthly. Prior to calibration, standard gases, a zero-gas generator, and a constant temperature and humidity chamber were prepared. The instruments to be calibrated were placed inside the constant temperature and humidity chamber to eliminate the effects of temperature and humidity fluctuations during transportation. During calibration, the zero-gas generator was first connected to the instrument’s sampling port, and gas was continuously supplied for 30 min. After the instrument stabilized, calibration was performed using three types of standard gases: high-concentration, medium-concentration, and low-concentration. The deviation was calculated to ensure the accuracy of the sensors. All sensors were connected to the same server, which performed automatic calibration every day at midnight. Data were extracted on a weekly basis for random inspection. In cases of repeated instrument data drift or inconsistent sensor timestamps, re-synchronization was performed to ensure uniform timing. Meteorological data, including air temperature, atmospheric humidity, wind speed, rainfall, and air pressure in the study area, were collected from a scientific research-grade weather station installed on the mountain slope above the cave (WXT536, Vaisala Co. Ltd., Finland). The automatic monitoring time and frequency were synchronized with those of the in-cave monitoring instruments. In addition, soil CO₂ sensors (GMP251, Vaisala, Finland) and temperature sensors (AV-10T, Avalon, USA) were installed in a relatively flat area near the weather station to monitor the CO₂ concentration and temperature of the overlying soil above the cave. The sensors were buried at a depth of 30–40 cm, with monitoring accuracies of 10 ppmv and 0.1 °C, respectively. The relevant monitoring data were integrated into the data logger of the weather station and ultimately aggregated to the external data center. Tourists primarily enter Jiutian Cave by swiping purchased tickets at the turnstiles. Therefore, the 2024 tourist data were mainly obtained from turnstile records, which were used to calculate the daily number of tourists. This dataset includes the entry time of all tourists; however, since no turnstile scanning is required upon exiting the cave, the exact duration of each tourist’s visit cannot be determined. Tourists typically move at a leisurely pace while sightseeing inside the cave. Meanwhile, daily precipitation data from Yiyuan Meteorological Station (2023–2024) were compared with the precipitation data collected by the scientific research-grade weather station at Jiutian Cave to ensure data accuracy.

Correlation analysis

Pearson correlation analysis assesses the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables. The Origin 2024 software was used to perform a correlation analysis between cave-air CO2 concentration and soil CO2 concentration.

Virtual temperature (T v)

The foundation of cave ventilation primarily depends on the temperature difference between surface air and cave air, which results in buoyancy-driven variations in CO₂ concentration. Meteorologists utilize virtual temperature (Tv) to characterize air buoyancy, which is defined as the temperature at which dry air must be at the same pressure to possess the same density as moist air. The virtual temperature of the atmosphere is approximately expressed as

where T and Tv are the absolute temperature (K) and virtual temperature (K), respectively, and r is the mixing ratio (dimensionless), defined as the ratio of the mass of water vapor to that of dry air. Thus, variations in the virtual temperature serve as a proxy for those in air density, which can be obtained through the equation of state for moist air:

where p, ρ, and Rd are the pressure (Pa = J m−3), air density (kg m−3), and particular gas constant for dry air (286.97 J kg−1 K−1), respectively. Equation (2) makes clear that, for a given altitude level (pressure), air density is related directly to Tv, which serves therefore as a surrogate variable for determining buoyancy. Equation (2) is only valid for the free atmosphere, while for caves or soils, it should not be used due to high concentrations of CO2 in the air. because the molar mass of dry air (md) is very constant, 0.02897 kg · mol−1, since air composition is very constant once water vapor has been excluded.

Consequently, Kowalski and Sanchez-Cañete32 established the correct equation to calculate the virtual temperature and provide a template calculation: http://fisicaaplicada.ugr.es/pages/tv/!/download. The governing equation is below33:

where T = temperature (°C); rv = water vapor mixing ratio; rc = carbon dioxide mixing ratio.

The calculation formula for the virtual temperature difference (dTv) between the inside and outside of the cave34:

Continuous wavelet analysis

Continuous wavelet analysis (CWA)35 is a time–frequency analysis method widely used in signal processing, geophysics, ecology, and other fields. It primarily overcomes the limitation of traditional Fourier analysis, which cannot simultaneously capture the dual “time–frequency” information of non-stationary signals. By decomposing a signal into a set of “wavelets” with finite energy, adjustable scales (corresponding to frequency), and positions (corresponding to time), CWA enables precise analysis of the signal’s dynamic characteristics. In this study, MATLAB software was used to process the time-series data of cave-air CO₂ concentration for continuous wavelet analysis. The Morlet wavelet was chosen as the mother wavelet, and the analysis scales were set as a logarithmically spaced sequence. The Cone of Influence (COI) was depicted as an automatically calculated conical shadow, and the significance test was conducted based on a Monte Carlo simulation under a red noise background.

Results

Variations of climatic and soil environmental parameters

Jiutian Cave is situated in a temperate monsoon climate zone. From March 2023 to January 2025, the ambient atmospheric temperature outside the cave ranged from −16 to 39 °C, with an average of 14.92 ± 10.54 °C (Fig. 2), showing a characteristic pattern of higher values in summer and lower values in winter. Soil temperature ranged from −0.6 to 24.9 °C, with an annual average of 11.76 ± 7.48 °C, reflecting the seasonal characteristics of atmospheric temperature (higher in summer and lower in winter). Soil moisture varied from 4.6% to 60.9%, with an annual average of 19.45 ± 3.48%. It also displayed a seasonal pattern, showing higher values in summer and lower values in winter, and was strongly correlated with variations in summer precipitation. The CO₂ concentration in the overlying soil of Jiutian Cave ranged from 429 to 9432 ppmv, with an annual average of 2810 ± 2210 ppmv. Its seasonal characteristics were consistent with those of soil temperature and moisture, with soil CO₂ content being higher in summer when precipitation was more abundant.

Atmospheric temperature (a), soil temperature (b), average cave-air temperature at 4 points (c), atmospheric humidity (d), soil moisture (e), average relative humidity of the cave at 4 points (f), atmospheric CO₂ (g), soil CO₂ (h), Site 1 CO₂ (i), Site 2 CO₂ (j), Site 3 CO₂ (k), Site 4 CO₂ (l), number of tourist visits (m), virtual temperature difference (n), and precipitation (o). The flattened peaks of CO₂ concentrations at Sites 3 and 4 are due to the upper monitoring limit of the instrument being 20,000 ppmv. There are 1913 cutoff data points at Site 3 and 5972 cutoff data points at Site 4, accounting for only 2.1% and 6.7% of the total data, respectively. The dashed line segments represent different seasons. The data plots of a, c, d, f, i, j, and n were all smoothed using a second-order Savitzky–Golay smoothing filter with a 150-point window.

Characteristics of cave environment parameters

Jiutian Cave features a single-corridor structure that facilitates air exchange. From the perspective of the virtual temperature difference between the atmosphere and the cave, Jiutian Cave demonstrates seasonal ventilation. Analysis indicates that ventilation in Jiutian Cave primarily occurs in January, February, March, October, November, and December, while ventilation is absent from May to September (Fig. 2). Jiutian Cave is a popular tourist destination that attracts tourists year-round. However, the number of tourists peaks during four major public holidays: the Spring Festival in February (February 10–17), the Qingming Festival in April (April 4–6), Labor Day in May (May 1–5), and National Day in October (October 1–7). During these periods, the minimum number of tourists exceeds 500 person-visits. Consequently, these four major public holidays are classified as concentrated tourism periods, while the remaining months are categorized as scattered tourism periods.

The mean values of cave-air temperature at four monitoring sites during the monitoring period were as follows: Site 1 (16.23 ± 1.28 °C) < Site 2 (16.4 ± 0.49 °C) < Site 3 (17.41 ± 0.27 °C) < Site 4 (17.66 ± 0.29 °C). The cave-air temperature increased as one moved closer to the deeper sections of the cave (Table 1), with a temperature difference of ~1 °C between the cave entrance and the deeper areas. Additionally, there was no consistent spatial variation in relative humidity within the cave. The mean relative humidity in the deeper sections of the cave was ~0.48% lower than that at the entrance, indicating a minimal difference.

Characteristics and variations of cave-air CO2 concentration

During the monitoring period, the cave-air CO₂ concentrations at the four monitoring sites ranged as follows: Site 1: 317 to 5604 ppmv; Site 2: 338 to 9638 ppmv; Site 3: 383 ppmv to over 20,000 ppmv; and Site 4: 321 ppmv to over 20,000 ppmv. Higher CO₂ concentrations were observed in areas closer to the deeper sections of the cave (Fig. 2). In addition, the cave-air CO₂ concentration exhibited a sharp increase from Site 2 to Site 3, primarily because both sites are situated at the turning points of the cave corridor (Fig. 1). This section of the cave corridor functions like a watershed, separating the front and rear spaces of the cave, which hinders air exchange and leads to the continuous accumulation of CO₂ gas in the hall where Site 3 is located. Over time, the fluctuation curves of CO₂ concentrations at the four monitoring sites in the cave displayed similar patterns, generally showing seasonal variations characterized by higher values in summer and autumn and lower values in winter and spring (Figs. 2, 3). On a diurnal scale, the curves of cave-air CO₂ concentrations at Site 1 and Site 2 exhibited significant diurnal variation, while those at Sites 3 and 4 were relatively stable. This indicates that the external environment can significantly influence the cave conditions between Sites 1 and 2, while the cave environments at Sites 3 and 4 remain relatively stable and less impacted by external factors. Throughout the entire monitoring period, the cave-air CO₂ concentrations at all four monitoring sites displayed four consistent high-intensity pulsed increases (indicated by the dashed shaded areas in Fig. 2), which corresponded with the peak periods of tourist visits to Jiutian Cave. This indicates that tourism activities significantly impact the cave-air CO₂ concentration in Jiutian Cave.

Discussion

High-resolution monitoring in many caves has demonstrated that the primary source of cave-air CO₂ is soil CO₂36 (see Text S1 in the Supplementary Material for more information). However, the transfer of CO₂ from the soil to the cave is a long-term process that can be disrupted by various factors during this transfer37, thereby altering the correlation between cave-air CO₂ concentration and soil CO₂ concentration (Table 1). In terms of correlation, the associations between soil CO₂ concentration and cave-air CO₂ concentration vary among the four monitoring sites. Site 1 exhibits the weakest correlation between cave-air CO₂ concentration and soil CO₂ concentration, while Site 4 shows a strong positive correlational trend between the two. Spatially, the correlation between cave-air CO₂ concentration and soil CO₂ concentration strengthens with increasing cave depth. These features primarily stem from the fact that Site 1, located closest to the cave entrance and frequently exchanging air with the external environment, is susceptible to disturbances. In contrast, Site 4, which is the farthest from the entrance, is less influenced by environmental factors. As a result, soil CO₂ is continuously transported to and accumulated in the deeper sections of the cave. Sites 2 and 3, situated in the middle of the cave, exist within the transition zone between external disturbances and deep stability. While they may also be impacted by significant changes in the external environment, the effects are likely to be less pronounced.

Due to the impact of tourism activities, significant discrepancies remain between the changes in soil CO₂ concentration and those in cave-air CO₂ concentration within the study area (Fig. 4). The most notable of these discrepancies is the four substantial pulsed increases in cave-air CO₂ concentration that occurred during the four periods of concentrated tourism activities (Figs. 2, 4). When excluding the pulsed increases in cave-air CO₂ concentration caused by tourism activities (dashed ellipse in Fig. 4), the cave-air CO₂ concentration, as previously mentioned, displays a seasonal variation trend akin to that of soil CO₂ concentration. Specifically, higher values are observed in summer and autumn, while lower values occur in winter and spring. However, the peak concentration of cave-air CO₂ lags behind that of soil CO₂ concentration by a specific period. During the monitoring periods in 2023 and 2024, the peak soil CO₂ concentration all occurred from August 5 to 11, while the peak cave-air CO₂ concentrations at the four monitoring sites in Jiutian Cave were recorded from August 25 to 28, August 20 to 25, August 25 to over 26, and August 25 to over 26, respectively, resulting in a lag of at least approximately 14 to 21 days. In terms of the causes for the lag, the delay in the peak cave-air CO₂ concentration may be attributed to the regulation and storage effect of the overlying bedrock cap, which slows down the downward migration rate of CO₂.

Site 1 CO₂, Site 2 CO₂, Site 3 CO₂, and Site 4 CO₂ and soil CO₂ concentrations from March 2023 to January 2025 (dashed ellipses indicate peak periods of tourism activity in May and October), and the number of tourists in 2024 is also included (the red arrows represent the lagged input of soil CO2 into the cave, and the yellow dashed lines divide different seasons).

Cave-air temperature and relative humidity are crucial environmental factors within caves, and fluctuations in these parameters directly influence the cave-air CO₂ concentration38. Artificial light sources in tourist caves, along with heat generated by human activities, can lead to an increase in cave-air temperature and a decrease in relative humidity. Analyzing the four periods of concentrated tourism activities (Fig. 2), it is evident that a higher number of tourists correlates with more pronounced changes in cave-air temperature and relative humidity. However, there are differences across different cave zones. Variations at Site 1 during concentrated tourism periods were smaller than those at the other three sites, while the variations at Site 4 were the largest during these periods. This is because the impact of tourism activities on the open environment at the cave entrance is buffered by various disturbances from the external environment. In contrast, the environment at the deepest part of the cave (where Site 4 is located) is stable, and it is difficult to discharge the large amount of heat brought by tourism activities in a timely manner. For example, during the Spring Festival in February (when the number of tourists was the smallest), the cave-air temperature at Site 1 increased by ~0.5 °C, while the cave-air relative humidity decreased by ~2%. In contrast, the cave-air temperature at Site 4 increased by ~0.7 °C, and the relative humidity decreased by ~2.1%. During the Labor Day holiday in May (when the number of tourists was the largest), the cave-air temperature at Site 1 increased by ~1 °C, with the cave-air relative humidity decreasing by ~3.2%. Meanwhile, the cave-air temperature at Site 4 increased by ~1.3 °C, and relative humidity decreased by ~3.5%. (gray shaded areas in Fig. 5).

The orange line represents cave-air temperature in °C; the blue line represents cave-air relative humidity in %. All lines were all smoothed using a second-order Savitzky–Golay smoothing filter with a 150-point window, except for the one representing tourist data. The gray dashed lines indicate the four concentrated tourism periods.

However, the cave-air temperature and relative humidity recover very quickly. Approximately one day after the end of the concentrated tourism period, these levels can return to over 90% of those recorded the day before the holiday. In contrast, the cave-air CO₂ concentration cannot recover to more than 90% of the pre-holiday level within one day after the end of the concentrated tourism period, and its recovery rate is significantly slower than that of the cave-air temperature and relative humidity (Fig. 2). This occurs because, after the cessation of tourism activities, the cave walls can rapidly absorb excess heat, causing the cave-air temperature to approach the baseline temperature of the walls39. Additionally, Jiutian Cave experiences perennial dripping water, which helps to compensate for the moisture loss caused by tourists’ respiration and light exposure31. However, the significant amount of CO₂ generated by tourists’ respiration during concentrated tourism periods tends to accumulate in the cave and diffuses slowly. Moreover, the reduction of cave-air CO₂ concentration mainly relies on ventilation with the external environment, and the mechanisms for its removal are limited40,41.

Studies have demonstrated that tourism activities can elevate cave-air CO₂ concentrations by an order of magnitude over a specific period. This increase persists as the number of tourists rises and the duration of visits extends12. In Jiutian Cave, the cave-air CO₂ concentration showed a pulsed increase corresponding to surges in tourist numbers during concentrated tourism periods (Figs. 2, 6). The extreme fluctuations of cave-air CO₂ concentrations at the four monitoring sites in Jiutian Cave closely correlate with fluctuations in tourist numbers. During the two concentrated tourism periods—the Labor Day holiday in May and the National Day holiday in October—the cave-air CO₂ concentrations at all four sites exhibited significant pulsed growth characteristics. Meanwhile, there were slight increases in cave-air CO₂ concentrations during the minor tourist peaks of the Spring Festival in February and the Qingming Festival in April (gray shaded areas in Figs. 2, 6). This suggests that tourism activities can impact the entire cave system. As previously mentioned, the cave environments at Sites 1 and 2, which are closer to the entrance, are more fragile and highly sensitive to tourism activities. In contrast, the environments at Sites 3 and 4, located farther from the entrance, are more stable and exhibit a slower response to tourism activities. This is evident in Fig. 6: during the Spring Festival holiday in February, Sites 1 and 2 reached their monthly peak cave-air CO₂ concentrations on February 14, while Sites 3 and 4 reached theirs on February 16, resulting in a lag of approximately 2 days. The same pattern was observed during the Qingming Festival in April and the Labor Day holiday in May, where Sites 1 and 2 reached their monthly peak CO₂ concentrations at least one day earlier than Sites 3 and 4.

In examining the relationship between tourism activities and cave-air CO₂ concentration (Fig. 6), it was observed that during four periods of concentrated tourism, a significant increase in cave-air CO₂ concentration could be triggered when the number of tourists exceeded 100 person-times for four consecutive days. In this case, the spatial distribution of cave-air CO₂ concentration was approximately as follows: Site 1 (1726 ppmv) < Site 2 (2667 ppmv) < Site 4 (4416 ppmv) < Site 3 (4598 ppmv). However, when the number of daily tourists exceeds 300 person-times, the cave-air CO₂ concentration exhibits a significant pulsed increase. During the study period, the highest growth rate of CO₂ concentration was recorded on a day with 933 tourists. On this occasion, the spatial distribution of cave-air CO₂ concentration was approximately as follows: Site 1 (4172 ppmv) < Site 2 (8692 ppmv) < Site 4 (16,260 ppmv) < Site 3 (17,895 ppmv). During the scattered tourist periods, the highest total monthly tourist numbers were recorded in March (744 person-times) and September (609 person-times). Additionally, the daily tourist numbers reached 123 person-times on March 17 and 120 person-times on September 16, 2024. However, none of these instances caused a noticeable increase in cave-air CO₂ concentration. Therefore, for tourist activities to induce a significant change in cave-air CO₂ concentration, the average daily tourist number must exceed 100 person-times for at least four consecutive days.

Studies have demonstrated that caves possess self-recovery capabilities. As tourism activities introduce substantial volumes of CO₂, cave ventilation facilitates air exchange with the surrounding atmosphere, resulting in a reduction of the cave-air CO₂ concentration19. However, the impact of excessive human activities in tourist caves on the original ecological environment requires a longer period for self-repair29. Therefore, it is essential to assess the self-recovery capacity of caves and provide recommendations and measures for the subsequent management of tourist caves to achieve the sustainable development of cave tourism.

Based on the continuous wavelet transform of CO₂ concentrations in Jiutian Cave, the variation cycle of cave-air CO₂ concentrations primarily occurs over a 24-h period. However, recovery is most rapid at the entrance, while the deeper sections of the cave exhibit a slower recovery rate. Furthermore, these diurnal variations in cave air are most pronounced during autumn and winter (Fig. 7). This phenomenon can be attributed to Jiutian Cave being a single-entry cave (Fig. 1) with no significant skylights on the cave ceiling; thus, cave ventilation predominantly depends on air exchange through the entrance passage. Additionally, the internal elevation of the cave is lower than that of the entrance, which results in the accumulation of dense cold air in the lower-elevation areas. Consequently, this leads to significant seasonal stagnation of cave air42,43, resulting in a diminished recovery capacity in the deeper sections of the cave.

Regarding the recovery of changes in cave-air CO₂ concentration, this study defines the cave’s recovery capacity as the ability of the daily average cave-air CO₂ concentration to decrease to the average cave-air CO₂ concentration recorded during the week prior to holidays. This average concentration is referred to as the “pre-interference concentration”. The cave’s self-recovery capacity varies under different disturbance conditions. In terms of tourist numbers, the Qingming Festival in April, Labor Day in May, and National Day in October (Fig. 8a–c) were the three concentrated tourism periods, attracting the largest number of tourists to Jiutian Cave in 2024. Among these holidays, the number of tourists during Labor Day (2439 person-times) was higher than during National Day (1530 person-times), which, in turn, exceeded the number during the Qingming Festival (516 person-times). In terms of the number of holiday days, there were also differences: National Day (7 days) > Labor Day (5 days) > Qingming Festival (3 days). Calculations indicate that (Fig. 9a–c) at Site 1, the increase in cave-air CO₂ concentration during the Qingming Festival in April was ~1100 ppmv, with a recovery period of about 6 days. During the Labor Day in May, the increase in cave-air CO₂ concentration reached approximately 4445 ppmv, with a recovery period of about 10 days. Finally, during National Day in October, the increase in cave-air CO₂ concentration was approximately 3639 ppmv, with a recovery period of about 13 days. Among the various festivals, the Qingming Festival in April attracted the fewest tourists and had the shortest holiday duration. It also experienced the smallest increase in cave-air CO₂ concentration and the fastest recovery rate. Although the number of tourists during the National Day in October was nearly 1000 fewer than that during Labor Day in May, the recovery period was about 3 days longer than that of Labor Day. This suggests that a higher number of tourists can lead to a short-term increase in cave-air CO₂ concentration, while the duration of tourism may be a crucial factor influencing the recovery capacity of cave-air CO₂ concentration.

a Diagrams illustrating cave-air CO₂ concentrations at four monitoring sites alongside tourist numbers from March to April 15, 2024 (covering the Qingming Festival holiday). b Diagram of cave-air CO₂ concentrations at four monitoring sites and tourist numbers from April 15 to June 15, 2024 (covering the Labor Day holiday). c Diagram of cave-air CO₂ concentrations at four monitoring sites and tourist numbers from September 15 to November 15, 2024 (covering the National Day holiday), and d Diagram of ventilation status in April, May, and October 2024 (dTv = Surface Tv−Cave Tv; when dTv > 0, the cave lacks ventilation).

a–c Represent the decay times at Site 1 following the Qingming Festival (April), Labor Day (May), and National Day (October), respectively. d–f represent the decay times at Sites 2–4 after Labor Day (May), respectively. The time data are recorded at 10-min intervals, e.g., t₁ = 10 min, t₂ = 20 min, t₃ = 30 min, and so on.

The recovery capacity varies across different sections of the cave. For instance, during Labor Day in May, when tourist numbers peaked (Figs. 8b and 9d–f), Site 1, located at the cave entrance, is significantly influenced by the surrounding open environment. The CO₂ concentration curve exhibited a sharp increase followed by a steep decline, with a full recovery to the pre-interference concentration occurring approximately 5 days after the holiday ended. Similarly, the CO₂ concentration curve at Site 2 demonstrates a sharp rise followed by a steep drop. However, approximately 14 days post-holiday, its CO₂ concentration begins to stabilize but does not return to the pre-interference concentration, remaining about 750 ppmv above the daily average. In contrast, the CO₂ concentration curves at Sites 3 and 4, which are located farther from the cave entrance, exhibit a pattern characterized by a sharp increase followed by a gradual decline and a slow recovery. Specifically, these two sites require approximately 13 and 19 days, respectively, to stabilize, and they continue to struggle to return to their daily average values. Moreover, the CO₂ concentrations at Sites 3 and 4 after the holiday are approximately 6000 and 7000 ppmv higher, respectively, than the pre-interference concentrations. This indicates that CO₂ generated by holiday tourism activities accumulates in the deeper sections of Jiutian Cave, causing a continuous increase in the cave’s air CO₂ concentration. Furthermore, in terms of the variation in recovery time and recovery status, the order of recovery time is Site 4 (19 days) > Site 3 (13 days) > Site 1 (10 days) > Site 2 (5 days). Among these monitoring sites, all except Site 1 fail to recover to the daily background level. This suggests that when the cave-air CO₂ concentration is significantly disturbed by external factors, the shallower areas of the cave can relatively easily return to the pre-interference concentration. Although the deeper sections of the cave possess self-regulating capabilities, they struggle to return to the pre-interference concentration due to the stability of the internal cave environment.

Generally, ventilation is the primary mechanism for removing CO₂ from cave air19. In this study, the virtual temperature difference (dTv) was utilized to simulate the ventilation status of cave air. When dTv is negative [dTv = surface Tv−cave Tv], it indicates that the cave is ventilated; conversely, when dTv is positive, the cave lacks ventilation. In terms of ventilation intensity, the order is October > April > May (Fig. 8d). Notably, October experienced nearly complete ventilation, whereas May showed a lack of ventilation. In April, the durations of ventilation and lack of ventilation were approximately equal. To analyze the impact of ventilation on the recovery capacity of cave-air CO₂ concentrations, a comparison was made based on the recovery status of cave-air CO₂ concentration during these three holidays (Fig. 8a–c). In April, although ventilation occurred occasionally, only the cave-air CO₂ concentrations at Sites 1 and 2 were able to return to pre-interference concentrations after the conclusion of tourism activities. The cave-air CO₂ concentrations at Sites 3 and 4 did not return to the pre-interference concentration, remaining approximately 3300–3500 ppmv above the pre-interference concentration. A detailed analysis conducted for May indicated that the recovery of cave-air CO₂ concentrations was consistent with the trends observed in April. Furthermore, due to limited ventilation, the cave-air CO₂ concentrations at Sites 3 and 4 were 6000–7000 ppmv higher than the pre-interference concentration, nearly double the levels recorded in April. In October, however, due to improved ventilation, the cave-air CO₂ concentrations at all four monitoring sites were able to return to the pre-interference concentrations following the conclusion of tourism activities. Even in December, the cave-air CO₂ concentrations continued to decrease due to ongoing ventilation throughout the winter, which leads to a reduction in cave-air CO₂ concentration. By the end of winter, specifically before the Spring Festival in February, the entire cave-air CO₂ concentration reaches its lowest level. At this time, the minimum CO₂ concentration at Site 1 is 471 ppmv, which is 5132 ppmv lower than the maximum CO₂ concentration observed during the concentrated tourism periods. The minimum at Site 2 is 473 ppmv, which is 9166 ppmv lower than the maximum recorded during the concentrated tourism periods. At Site 3, the minimum concentration is 653 ppmv, which is at least 19,349 ppmv lower than the maximum recorded during the concentrated tourism periods. At Site 4, the minimum concentration is 839 ppmv, which is at least 19,161 ppmv lower than the maximum recorded during the concentrated tourism periods. Therefore, it can be concluded that cave ventilation can enhance the recovery rate of cave-air CO₂ concentration.

Jiutian Cave is open to tourists primarily from 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., and no tourists are permitted outside these hours. Therefore, the CO₂ generated by tourism activities occurs mainly during business hours, while the cave undergoes self-recovery during non-business hours. As shown in Table 2, both January and February fall within the ventilation season. Additionally, the Spring Festival in February marked the first concentrated tourism period at Jiutian Cave in 2024. In January, the daily number of tourists did not exceed 100, so the cave-air CO₂ concentration was not significantly influenced by human activity. Therefore, comparing these two periods better illustrates the impact of a substantial increase in tourist numbers on cave-air CO₂ concentration (Fig. 10). The period from the 11 to 14 January 2024 was selected for comparison because there were no tourist visits to Jiutian Cave on January 10 or from 15 to 16 January. Based on the average cave-air CO₂ concentrations at the four monitoring sites during the operating and non-operating periods in January, the concentrations during non-operating periods were generally lower than those during operating periods. Additionally, after four consecutive operating days in January, no significant increase in cave-air CO₂ concentration was observed at the remaining four monitoring sites. In contrast, the situation reversed in February. On the first day when tourist numbers reached 100 person-times, the cave-air CO₂ concentrations at Sites 3 and 4 during non-operating periods were already higher than those during operating periods. After four consecutive days with tourist numbers exceeding 100 person-times, the CO₂ concentrations were more than twice as high as those on the first day. Furthermore, the cave-air CO₂ concentrations at Sites 1 and 2 on 14 February 2024 were at least double those on 11 February 2024. Since the tourist volume during the February Spring Festival was the lowest among the four concentrated tourism periods, we conclude that when the number of tourists exceeds 100 person-times in a single day, it leads to a significant increase in cave-air CO₂ concentration. Furthermore, when tourist numbers exceed 100 person-times for several consecutive days, they cause a substantial cumulative increase in cave-air CO₂ concentration.

Therefore, in subsequent management, restrictions should primarily focus on limiting the number of tourists entering the cave and the duration of their stay during concentrated tourism periods. For instance, a strict online ticket reservation system could be implemented—not only to control the number of tourists entering the cave each hour but also to regulate the length of each visit. This system would ensure that tourists enter the cave only during their reserved time slots, allowing staff to effectively manage the staggered entry and exit of tourists. Furthermore, distinct management strategies should be implemented for different cave zones. From a resilience perspective, the area from the cave entrance to Site 2 should serve as the primary tourist activity zone; the area between Sites 2 and 3 as the transition zone; and the area between Sites 3 and 4, which has the most stable environment, as the core zone. No restrictions on tourist residence time are necessary in the tourist activity zone, whereas such restrictions are required in the transition zone. In the core zone, if the number of tourists becomes excessive, opening hours can be reduced, or tourist entry can be prohibited altogether.

In summary, Jiutian Cave is a popular tourist cave. The overlying soil CO₂ serves as the primary carbon source for the CO₂ concentration in cave air. However, during peak tourist periods, CO₂ released from tourists’ respiration causes a pulsed increase in the cave’s air CO₂ concentration. Additionally, a higher number of tourists results in a sustained short-term increase in the cave-air CO₂ concentration. From the perspective of the resilience of cave-air CO₂ concentration, tour duration is a key factor influencing this resilience. The recovery capacity of cave-air CO₂ concentration varies across different parts of the cave. Ventilation is another key factor controlling the seasonal variation of cave-air CO₂ concentration in Jiutian Cave, and it can enhance the resilience of cave-air CO₂ concentration. Jiutian Cave is mainly ventilated in winter but has limited ventilation in summer, with the fastest recovery rate of CO₂ concentration occurring in winter. Finally, from the perspectives of ecological environmental protection and the sustainable development of tourism activities in Jiutian Cave, tourism should primarily take place in winter, while the number of tourists should be strictly controlled during the summer.

Overall, this study systematically reveals the spatial and temporal variation characteristics of air CO₂ concentration in Jiutian Cave and clarifies the key controlling mechanisms. It provides valuable data to support regional karst carbon cycle research and cave environmental protection. However, to contextualize these findings more comprehensively, several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, high-frequency monitoring depends on numerous precision sensors. However, during long-term monitoring, these sensors are vulnerable to factors such as high humidity, excessive dust inside the cave, and abnormal weather conditions outside the cave. These influences can cause data drift or equipment malfunctions, impeding the analysis of long-term trends. Future studies should increase the frequency of sensor calibration and maintenance to address these issues. Second, due to the lack of real-time ventilation data, modeling discussions cannot be conducted. Therefore, the analysis of the variation characteristics of cave-air CO₂ concentration and tourist activities in this study is primarily based on empirical concentration trends. These trends represent observational data rather than quantitative flux measurements. Consequently, the results reflect site-specific observations. Third, due to the absence of synchronous measurements of airflow, radon levels, or pressure gradients to validate ventilation intensity in this study, only virtual temperature was used to infer the cave’s ventilation intensity. This limitation may result in a certain degree of overestimation of the cave’s ventilation intensity in the present research. Fourth, because the upper detection limit of the monitoring instrument for cave-air CO₂ concentration is 20,000 ppmv, data truncation may lead to an underestimation of the results. The number and percentage of truncated data points are reported in this study, and qualifiers such as “approximately” and “at least” have been consistently applied in analyses involving truncated values. Consequently, the impact on conclusions regarding overall trends is minimal. Fifth, the absence of data on the specific duration of stay and the number of tourists in different cave regions prevents the calculation of CO₂ emissions from tourist respiration in each area, making modeling analyses infeasible. Therefore, the assessment of the tourist threshold is primarily based on descriptive observations of the data.

Data availability

All data used during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary materials. The datasets generated and used during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Liu, Z. H., Dreybrodt, W. & Wang, H. J. A new direction in effective accounting for the atmospheric CO2 budget: considering the combined action of carbonate dissolution, the global water cycle and photosynthetic uptake of DIC by aquatic organisms. Earth Sci. Rev. 99, 162–172 (2010).

Serrano-Ortiz, P. et al. Hidden, abiotic CO2 flows and gaseous reservoirs in the terrestrial carbon cycle: review and perspectives. Agric. For. Meteorol. 150, 321–329 (2010).

Frisia, S. et al. Carbon mass-balance modelling and carbon isotope exchange processes in dynamic caves. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 380–400 (2011).

Faimon, J., Troppová, D., Baldík, V. & Novotný, R. Air circulation and its impact on microclimatic variables in the Císařská Cave (Moravian Karst, Czech Republic). Int. J. Climatol. 32, 599–623 (2012).

Walvoord, M. A., Striegl, R. G., Prudic, D. E. & Stonestrom, D. A. CO2 dynamics in the Amargosa Desert: fluxes and isotopic speciation in a deep unsaturated zone. Water Resour. Res. 41, W02006 (2005).

Polyak, V. J. & Asmerom, Y. Late Holocene climate and cultural changes in the Southwestern United States. Science 294, 148–151 (2001).

Baldini, J. U. L., McDermott, F. & Fairchild, I. J. Structure of the 8200-year cold event revealed by a speleothem trace element record. Science 296, 2203–2206 (2002).

Spötl, C., Fairchild, I. J. & Tooth, A. F. Cave air control on dripwater geochemistry, Obir Caves (Austria): implications for speleothem deposition in dynamically ventilated caves. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69, 2451–2468 (2005).

Frisia, S., Borsato, A., Preto, N. & McDermott, F. Late Holocene annual growth in three Alpine stalagmites records the influence of solar activity and the North Atlantic Oscillation on winter climate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 216, 411–424 (2003).

Jennings, J. N. Karst Geomorphology (Basil Blackwell, 1985).

Breecker, D. O. et al. The sources and sinks of CO2 in caves under mixed woodland and grassland vegetation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 96, 230–246 (2012).

Jobbágy, E. G. & Jackson, R. B. The vertical distribution of soil organic carbon and its relation to climate and vegetation. Ecol. Appl. 10, 423–436 (2000).

Miorandi, R., Borsato, A., Frisia, S., Fairchild, I. J. & Richter, D. K. Epikarst hydrology and implications for stalagmite capture of climate changes at Grotta di Ernesto (NE Italy): results from long-term monitoring. Hydrol. Process. 24, 3101–3114 (2010).

Borsato, A., Frisia, S. & Miorandi, R. Carbon dioxide concentration in temperate climate caves and parent soils over an altitudinal gradient and its influence on speleothem growth and fabrics. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms. 40, 1158–1170 (2015).

Bourges, F. et al. Hydrogeological control on carbon dioxide input into the atmosphere of the Chauvet-Pont d’Arc cave. Sci. Total Environ. 716, 136844 (2020).

De Freitas, C. R., Littlejohn, R. N., Clarkson, T. S. & Kristament, I. S. Cave climate: assessment of airflow and ventilation. J. Climatol. 2, 383–397 (1982).

Troester, J. W. & White, W. B. Seasonal fluctuations in the carbon dioxide partial pressure in a cave atmosphere. Water Resour. Res. 20, 153–156 (1984).

Buecher, R. H. Microclimate study of Kartchner Caverns, Arizona. J. Cave Karst Stud. 61, 108–120 (1999).

Banner, J. L., Guilfoyle, A., James, E. W., Stern, L. A. & Musgrove, M. Seasonal variations in modern speleothem calcite growth in Central Texas, U.S.A. J. Sediment. Res. 77, 615–622 (2007).

James, E. W., Banne, R. J. L. & Hardt, B. A global model for cave ventilation and seasonal bias in speleothem paleoclimate records. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 16, 1044–1051 (2015).

Weisbrod, N., Dragila, M. I., Nachshon, U. & Pillersdorf, M. Falling through the cracks: the role of fractures in earth-atmosphere gas exchange. Geophys. Res. Lett 36, L02401 (2009).

Sanchez-Cañete, E. P., Serrano-Ortiz, P., Kowalski, A. S., Oyonarte, C. & Domingo, F. Subterranean CO2 ventilation and its role in the net ecosystem carbon balance of a karstic shrubland. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L09802 (2011).

Baldini, J. U. L., McDermott, F., Hoffmann, D. L., Richards, D. A. & Clipson, N. Very high-frequency and seasonal cave atmosphere Pco2 variability: implications for stalagmite growth and oxygen isotope-based paleoclimate records. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 272, 118–129 (2008).

Baldini, J. U. L., McDermott, F. & Fairchild, I. J. Spatial variability in cave drip water hydrochemistry: implications for stalagmite paleoclimate records. Chem. Geol. 235, 390–404 (2006a).

Fairchild, I. J. & Baker, A. Speleothem Science: from Process to Past Environments (John Wiley & Sons, 2012).

Lang, M., Faimon, J. & Ek, C. A case study of anthropogenic impact on the CO2 levels in low-volume profile of the Balcarka Cave (Moravian Karst, Czech Republic). Acta Carsol. 44, 71–80 (2015).

Ek, C. & Gewelt, M. Carbon dioxide in cave atmospheres. New results in Belgium and comparison with some other countries. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 10, 173–187 (1985).

Liñán, C., Vadillo, I. & Carrasco, F. Carbon dioxide concentration in air within the Nerja Cave (Malaga, Andalusia, Spain). Int. J. Speleol. 37, 99–106 (2008).

Zhang, M. L., Zhu, X. Y., Wu, X., Zhang, B. Y. & Pan, M. C. Impact of tourism activities on the cave environment and landscape of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) deposits at Shujinggong cave, Bama county. Carsol. Sin. 36, 119–130 (2017) (in Chinese).

Ma, Q. Q. Research on the Seasonal Variation of Trace Elements in Drip Water of Jiutian Cave in Shandong Penisula and their Implications for Climate and Environment. Master Thesis, Ludong University (2014).

Zheng, Z. H. Hydrochemical Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Drip Water in the Jiutian Cave of Shandong Peninsula. Master Thesis, Ludong University (2019).

Kowalski, A. S. & Sánchez-Cañete, E. P. A New Definition of the virtual temperature, valid for the atmosphere and the CO2-rich air of the Vadose Zone. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 49, 1692–1695 (2010).

Sánchez-Cañete, E. P., Serrano-Ortiz, P., Domingo, F. & Kowalski, A. S. Cave ventilation is influenced by variations in the CO2-dependent virtual temperature. Int. J. Speleol. 42, 1–8 (2013).

Sekhon, N. et al. Diurnal to seasonal ventilation in Brazilian caves. Glob. Planet. Change 197, 103378 (2021).

Argoul, P. & Erlicher, S. On the use of continuous wavelet analysis for modal identification. In: Frémond, M. & Maceri, F. (eds) Mechanical Modelling and Computational Issues in Civil Engineering. Lecture Notes in Applied and Computational Mechanics, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 359–368 (2005).

Wong, C. & Banner, J. L. Response of cave air CO2 and drip water to brush clearing in central Texas: implications for recharge and soil CO2 dynamics. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 115, 6291–6297 (2010).

Mattey, D. P. et al. Carbon dioxide, ground air and carbon cycling in Gibraltar karst. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 184, 88–113 (2016).

Zhu, X. Y. & Zhang, M. L. Study on cave environment factors based on karst cave tourism activities. Carsol. Sin. 39, 426–431 (2020).

Yang, M. F. & Yin, J. J. Relationship between temperatures of karst caves and local average temperatures: taking Pailong cave of Puzhehei, Yunnan as an example. Carsol. Sin. 43, 780–795 (2024).

Pan, Y. X., Zhou, Z. F., Zhang, J., Wang, Y. L. & Tian, Z. H. Temporal and spatial distribution characteristics of microclimate environmental elements in Karst tourism caves—a case study of Zhijin cave in Guizhou province. Sci. Technol. Eng. 18, 20–30 (2018).

Baldini, J. U. L., Baldini, L. M., McDermott, F. & Clipson, N. Carbon dioxide sources, sinks, and spatial variability in shallow temperate zone caves: evidence from Ballynamintra Cave, Ireland. J. Cave Karst Stud. 68, 4–11 (2006b).

Ridley, H. E., Baldini, J., Prufer, K. M., Walczak, I. W. & Breitenbach, S. F. M. High-resolution monitoring of Yok Balum Cave, Belize: an investigation of seasonal ventilation regimes and the atmospheric and drip-flow response to a local earthquake. J. Cave Karst Stud. 77, 183–199 (2015).

Wang, Y. W. et al. High 222Rn concentrations and dynamics in Shawan Cave, southwest China. J. Environ. Radioact. 199-200, 16–24 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Thanks are given to Yiyuan New Scene Culture and Technology Development Co., Ltd (沂源新场景文化科技发展有限公司), Mr. Wei Wang (王伟) and Mr. Lei Zhang(张磊) for their significant assistance in the field work. This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (42577087, W2412149), the National Special Support Plan for High-Level Talent to Junbing Pu (Young Talent Plan, 2022), Taishan Industry Leading Talent Program (tscy20200416), National Science and Technology Key Project on Deep Earth (2024ZD1004103-6) and The government-sponsored overseas study program of the Shandong Provincial Government (202402030).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.P.: Data curation, software, formal analysis, visualization, methodology, and writing—original draft. W.L.: Formal analysis, data curation, and investigation. T.Z.: Formal analysis, data curation, and investigation. J.P.: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, and writing—review and editing. Z.Z.: Resources, writing—review and editing, Project administration. H. L.: Formal analysis, Data Curation, Investigation. Y.Z.: Formal analysis and data curation. R.N.N.: Resources, writing—review and editing, and project administration. G.A.: Software, resources, data curation, writing—review and editing, and project administration. H.E.: Software, resources, data curation, writing—review and editing, and project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, S., Liu, W., Zhang, T. et al. Dynamic patterns and resilience of cave-air CO₂ under tourism interferences in the Lushan National Geopark, north China. npj Herit. Sci. 14, 31 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02306-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02306-z