Abstract

This study investigates the provenance of Tang-dynasty black-glazed porcelain excavated from the Yingou site in Fuping, Shaanxi, through comparative analysis with authenticated Tang-dynasty Yaozhou kiln samples. A multi-analytical approach combining EDXRF, ICP–MS, XRD, SEM–EDS and Raman spectroscopy reveals that the Yingou samples exhibit minimal internal variability and share the high-alumina, low-silica signature characteristic of northern porcelains. Their glaze compositions, microstructural features, and diffusion behaviors closely match those of the Yaozhou samples. Major, trace, and rare-earth-element patterns show substantial overlap, with no meaningful compositional separation. The results show that Tang-dynasty black-glazed porcelains from the Yingou site exhibit strong compositional and technological consistency with Yaozhou black-glazed wares. This similarity supports production within a shared raw-material and technological framework, likely reflecting a common geological resource base or closely connected production systems, while acknowledging that finer-scale attribution requires broader comparative datasets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

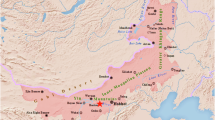

The Yingou Site, as shown in Fig. 1, located in Fuping County, Weinan City, Shaanxi Province, has been archeologically confirmed as a large, multi-component archeological complex encompassing diverse cultural sites, including urban foundations and ceramic relics. Before systematic excavations at the site, several locations from different historical periods had already been documented in the Fuping area. The site’s discovery provides crucial evidence for researching craft-production systems in northern China during the Tang and Song periods and attests to a strong continuity of regional civilization.

Black-glazed porcelains plays a crucial role in the history of Chinese ceramics. Its firing techniques originated from the experimental stages of southern celadon kilns during the Eastern Han Dynasty. During the Tang Dynasty, northern kilns, building upon the expertise from southern porcelain production, achieved both maturity and innovation in black-glazed porcelain craftsmanship. By the Song Dynasty, black-glazed porcelain reached its zenith, driven by the popular culture of tea competitions. From 2011 to 2013, the Yingou site underwent systematic excavation for archeological research purposes. The site includes a variety of kiln-like structures, such as round, semicircular, and horseshoe shapes, exhibit typical characteristics of northern kilns. Among the numerous porcelain samples recovered was a group of high quality black-glazed porcelains. These porcelains are distinguished by their refined craftsmanship, uniformly smooth and lustrous glazes, and minimal decorative patterns. Geographically, the Yingou site is located in close proximity to the renowned Yaozhou kilns. This geographical and administrative context has sparked ongoing scholarly debate over the provenance of the black-glazed porcelains excavated at the Yingou site: specifically, whether these Tang-dynasty porcelains were locally produced or from elsewhere?

Junding Xia1 carried out thermoluminescence (TL) dating on porcelain unearthed from the Yingou site. The results indicate that the celadon and black-glazed porcelain samples date to approximately 1200–1550 years ago, corresponding to the Tang dynasty. Li and Zhang2 analyzed the chemical compositions of the bodies and glazes of several black porcelain sherds unearthed from the Yingou site and compared them with Jian kiln black porcelain. The results indicate that the Yingou bodies are characterized by a distinct “high-alumina, low-silica” composition, thereby effectively excluding the possibility that the black-glazed porcelains from Yingou was produced at the Jian kiln. Liu and Li3 employed portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) to compare the chemical compositions of the bodies and glazes of Qingbai porcelain sherds unearthed from the Yingou site and the Hutian kiln. The results show that both belong to high silica, low alumina porcelains, but they differ markedly in several trace elements. Zhu et al.4 and Wang et al.5 investigated trace elements in the bodies of Qingbai porcelain from the Xicun kiln using LA-ICP-MS. The results indicate that thin-walled vessels unearthed at the Xicun kiln site were produced at the Hutian kiln, whereas thick-walled vessels were fired locally at Xicun. The concentrations of trace elements (V, Rb, Ba, Ta, Pb, and Th), together with the Nb/Ta ratio, can be used to discriminate between products from the Xicun and Chaozhou kilns. This approach further demonstrates the effectiveness of trace elements as indicators for determining ceramic provenance. Shen et al.6 used LA-ICP-MS to investigate trace elements in the glazes of Yaozhou kiln celadon from the Tang to Five Dynasties periods and found that glazes with the same geological signature were employed across different historical periods. According to the literature, this raw material may correspond to the so-called “Fuping glaze stone”, providing strong material evidence for the close relationship between the Yingou site and the Yaozhou kiln. Shi and Yong7 conducted multiple analyses and characterizations of unearthed Jun-glazed wares—using ED-XRF, ICP-MS, and SEM-EDS—the results indicate that some of the artifacts unearthed in Inner Mongolia may have originated from the Ding kiln in Hebei, while other artifacts are very likely from the Jun kilns in central and western Henan. As discussed above, although some preliminary research has been carried out on the celadon and Qingbai porcelain unearthed at the Yingou site, very limited work has focused on black porcelain. Black porcelain is generally considered to be produced from relatively high grade raw materials with complex chemical compositions and compared with celadon and white porcelain, its manufacture depends more strongly on locally available resources. Consequently, provenance studies based on black porcelain are of particular importance for determining the place of production with greater accuracy.

Previous studies have examined Yingou celadon, Qingbai porcelain, and regional clay resources, establishing that the area contains abundant kaolin and related raw materials suitable for ceramic production. Compositional analyses have excluded a Jian kiln origin and identified similarities and differences with other northern kilns. Trace-element studies on Yaozhou glazes further suggest that certain raw materials may have been sourced from the Fuping region. However, no study has yet undertaken a systematic, multi-method comparison specifically targeting Yingou black-glazed porcelain, despite its high provenance sensitivity and its greater reliance on local raw-material systems compared with celadon and white porcelains.

This study addresses this gap by analyzing the major, trace, and rare-earth element compositions, mineralogical phases, and microstructural characteristics of Yingou black-glazed porcelains using EDXRF, ICP-MS, XRD, SEM–EDS, and Raman spectroscopy. By comparing 15 samples from Yingou site with 8 authenticated Tang-dynasty Yaozhou kiln black-glazed porcelains, we aim to clarify whether the Yingou black-glazed porcelains were locally produced or formed part of the Yaozhou technological system.

Methods

A total of 15 Tang-dynasty black-glazed porcelains excavated from the Yingou site and 8 Tang-dynasty black-glazed porcelains from Yaozhou kiln were selected for analysis, descriptions of their bodies and glazes are given in Table 1, and representative photographs of the black-glazed porcelain samples are presented in Fig. 2. No intentional surface ornamentation or relief decoration was observed on the glaze surfaces, either through macroscopic examination or under optical microscopy. The visual characteristics of these wares are therefore defined primarily by glaze color, gloss, and surface texture rather than by decorative patterning, a feature consistent with typical Tang-dynasty northern black-glazed porcelains. The samples were sectioned using an SYJ-160 low-speed cutting machine and then embedded in epoxy resin for subsequent analyses.

This study did not involve human participants, human tissue, personal data, animals, or any procedures requiring ethical approval. According to the institutional guidelines of the Shaanxi University of Science and Technology, research involving archeological ceramic sherds does not fall under the scope of ethics committee or institutional review board oversight. Therefore, no ethical review or approval was required, and all analyses were conducted in accordance with institutional and national research guidelines.

Analytical methods

Cross-sections of all samples were examined using a KEYENCE VHX-7000 optical microscope to document microstructural features and to guide the selection of analytical points. The chemical compositions of the cross-sections were measured with an XGT-7200V X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF). For each sample, three to five spots were selected on the body region while explicitly avoiding glaze–body transition zones to prevent compositional mixing. The instrument was operated at 30 kV and 0.8 mA with a 120 s acquisition time, and mean values were calculated for subsequent interpretation.

Trace element concentrations were obtained using a NexION 5000 ICP-MS system. Prior to analysis, 100 mg of each powdered sample was digested in a closed-vessel system with a mixed acid matrix (HNO3-HF-HCl) at 180 °C for 90 min. Excess HF was removed by repeated evaporation with HNO3. The digested solutions were diluted to 50 mL with ultrapure water. QA/QC procedures included analysis of procedural blanks, duplicate digestions (RSD < 5%), and the certified reference material GBW 07105 (Chinese pottery clay), which showed recoveries of 92–105%. Each ICP-MS measurement consisted of 20 scans and triplicate runs.

Raman spectra were acquired using a Renishaw inVia confocal micro-Raman spectrometer to characterize crystalline phases at the glaze–body interface. A 532 nm excitation laser was applied at 1.31 mW to avoid thermal alteration, with an integration time of 10 s and three accumulations per spectrum. Raman spectral data were compared with the RRuff Raman standard spectral database (website: https://rruff.info/).

The microstructure and elements were observed using a FlexSEM 1000II scanning electron microscope equipped with an EDS detector. The polished cross-section was coated with gold and analyzed at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV.

The present study is based on 15 Yingou site and 8 Yaozhou kiln black-glazed porcelain samples. While this sample size is appropriate for an initial multi-method provenance comparison, it inevitably constrains the statistical resolution, particularly for distinguishing closely related production contexts within a large and temporally extensive kiln complex such as Yaozhou. Moreover, the Yaozhou kiln samples analyzed here derive from a limited number of kiln contexts and therefore may not capture the full compositional variability of the broader production system. Nevertheless, the strong internal coherence observed within each group, together with the convergence of multiple independent analytical proxies, lends confidence to the comparative interpretations presented in this study.

Results

Chemical composition analysis

The chemical compositions of all sample bodies are summarized in Table 2. The results indicate that the Tang-dynasty Yingou black-glazed porcelain bodies exhibit the typical high-alumina and low-silica characteristics of northern porcelains. The main oxide contents in the bodies are as follows: the mean SiO2 content is 67.66%, and the mean Al2O3 content is 21.91%. These values are very close to those of Tang-dynasty Yaozhou kiln samples (mean SiO2 67.98%; mean Al2O3 22.10%). This similarity suggests that the Tang-dynasty Yingou samples may have shared highly consistent raw-material choices and body recipes with those of the Yaozhou kiln. The Yingou site in Fuping County, Shaanxi Province, is located in close proximity to the Yaozhou kiln in Tongchuan City, Shaanxi Province. Given that raw materials for porcelain production were typically obtained locally, it is reasonable to infer that Yingou black porcelains most likely made use of kaolin or clay resources similar to, or even identical with, those exploited by the Yaozhou kiln, suggesting a relatively close geological relationship between the two areas.

Figure 3 presents box plots of the main oxide contents in the bodies of the black porcelain samples. First, the Tang-dynasty Yingou samples and the Tang-dynasty Yaozhou kiln samples display very similar median values and dispersion ranges for SiO2, Al2O3, and MgO. Second, the TiO2 contents of the Tang-dynasty Yingou samples (mean of 1.57%) differ only slightly from those of the Tang-dynasty Yaozhou kiln samples (mean 1.79%), and the Fe2O3 contents of the Tang-dynasty Yingou samples (mean 3.88%) and the Tang-dynasty Yaozhou kiln samples (mean 3.77%) are similarly distributed and relatively high. During high temperature firing, the similar ionic radii of Ti4+, Fe2+, and Fe3+ (rTi4+ = 0.068 nm, rFe2+ = 0.077 nm, rFe3+ = 0.069 nm)8 allow iron–titanium solid solutions to form readily, thereby producing a darker body color. Because the iron content in all samples is higher than the titanium content, the overall body color appears predominantly gray9.However, the relatively high TiO2 contents of the Tang-dynasty Yaozhou kiln samples enhance the yellow component of the body color, resulting in an overall grayish-yellow appearance.These observations are consistent with those reported in ref. 9: black porcelain bodies from the Yaozhou kiln of the Tang dynasty are predominantly dark gray, with some examples appearing gray, yellow, or grayish-yellow in tone, and most are coarse and relatively heavy.

Box plots of major oxide contents in the bodies of the Yingou (T-YG) and Yaozhou (T-YZY) samples. PCA score plot based on the selected major oxides showing the compositional relationship between groups. Symbols/colors distinguishing T-YG and T-YZY are as indicated in the figure; box plots show median, interquartilerange, and whiskers.

With respect to fluxing components, the K2O contents of the Tang-dynasty Yaozhou kiln samples (median ≈ 1.73%) are slightly lower than those of the Tang-dynasty Yingou site samples (median ≈ 2.20%). This difference may reflect variations in the proportions of fluxing agents or raw materials used in the Yingou black porcelain bodies. The CaO contents of the Tang-dynasty Yingou and Yaozhou kiln samples differ very little (median values of 0.58% and 0.57%, respectively), suggesting that the calcareous content of the clays and the control of the firing atmosphere were broadly similar.

A principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out on seven oxides (MgO, Al2O3, SiO2, K2O, CaO, TiO2 and Fe2O3) in the chemical-composition dataset for the sample bodies. Principal components 1 (34.6%) and 2 (27.7%) together account for 62.3% of the total variance, which adequately captures the overall differences among the samples. In the PC1–PC2 score plot, the two sample groups show substantial overlap with no clear boundary, indicating that their overall chemical compositions are similar and do not exhibit pronounced separation by provenance. In comparison, the T-YG samples exhibit greater dispersion along PC1, whereas the T-YZY samples are more tightly clustered. This slight separation occurs primarily along PC1 and is likely related to intrinsic factors such as variations in raw-material proportions within each group. Overall, however, the two groups show highly consistent body elemental compositions, indicating that the raw-material sources for the ceramic bodies were very similar. The substantial overlap between Yingou and Yaozhou samples in both major-oxide compositions and PCA space indicates a high degree of chemical similarity between the two groups. However, this overlap should be interpreted with caution. In geologically homogeneous regions such as northern Shaanxi, where ceramic raw materials are derived from broadly similar loess-related and sedimentary systems, compositional convergence may reflect the exploitation of shared geological resources rather than production within a single kiln or workshop. Accordingly, the PCA results support similarity at the level of raw-material background and technological tradition, but do not, in isolation, permit unequivocal attribution to a unique production center.

The chemical compositions of the glaze layers of the black porcelain samples are summarized in Table 3. For the Tang-dynasty black porcelain unearthed at the Yingou site, the mean SiO2 and Al2O3 contents are 64.66% and 11.86%, respectively, whereas for the Tang-dynasty Yaozhou kiln black porcelain samples the corresponding values are 66.27% and 10.51%. Because the T-YZY group has a higher SiO2 content and a lower Al2O3 content, the proportion of clay in the glaze is reduced, and the glaze is therefore expected to appear clearer (more transparent). Both T-YG (mean CaO 5.80%) and T-YZY (mean CaO 7.11%) contain relatively high amounts of CaO, which is conducive to enhancing the gloss and melt fluidity of the glaze10. Consequently, the glazes of both sample groups can be regarded as relatively high in quality. Both groups also show high Fe2O3 contents (T-YG mean 7.81%; T-YZY mean 7.56%), indicating that iron is the principal chromophore responsible for the black glaze coloration in both sample groups, which is consistent with the established color-development mechanism of black-glazed porcelain.

Cluster analysis based on seven oxides (MgO, Al2O3, SiO2, K2O,CaO, TiO2, and Fe2O3) in the glaze composition datasets of the above samples was carried out, as shown in Fig. 4. Principal components 1, 2, and 3 (PC1 = 43.0%, PC2 = 32.4%, PC3 = 13.8%) together account for 89.2% of the total variance, indicating that these three components adequately capture the main differences among the samples. In the plot, each sphere represents an individual sample, and each ellipsoidal surface denotes the confidence region of a sample group in multidimensional space. As shown in the figure, the ellipsoids corresponding to the Tang-dynasty Yingou samples and the Tang-dynasty Yaozhou kiln samples are relatively compact and largely overlapping, and their confidence regions likewise exhibit a high degree of overlap. This indicates that the main chemical characteristics of the Tang-dynasty Yingou black porcelains and the Tang-dynasty Yaozhou kiln black porcelains are highly similar, and further suggests that the glaze composition ratios and technological control in the two sample groups are broadly comparable.

The use of rare earth elements (REEs) in geochemical studies is now well established, and they have been widely employed as effective geochemical indicators11. According to previous studies, the types of raw materials used for porcelain production vary between regions, and the corresponding REE contents also differ. Moreover, because rare earth elements are highly stable, their abundances do not readily undergo significant changes over time12. Therefore, REE signatures can be used to constrain the provenance of the raw materials employed in the production of Tang-dynasty black porcelain unearthed at the Yingou site. In this study, the average rare earth element (REE) abundances of chondrites reported by Boynton13 were used as the reference standard. Following published procedures14,15,16, the REE contents of the Tang-dynasty black porcelain samples excavated from the Yingou site were normalized to chondrite, and the logarithms of the normalized values were plotted with log-normalized REE content on the vertical axis and atomic number on the horizontal axis. In addition, trace elements such as Zr, Nb, Cr, Ni, V, Sr, Rb, Tl and Pb were employed as auxiliary tracers to more accurately constrain the provenance of the Tang-dynasty black porcelain samples from Yingou site.

Box plots were constructed for the nine trace elements listed in Table 4 (excluding the rare earth elements) to present the results more intuitively. As shown in Fig. 5, the overall contents of Zr, Nb and Rb in the Tang-dynasty Yaozhou-kiln black-porcelain samples are slightly higher (Zr mostly 500–750 ppm, Nb mostly >20 ppm, Rb mostly 90–170 ppm), whereas the Tang-dynasty black-porcelain samples unearthed from the Yingou site show relatively lower levels (Zr approximately 300–680 ppm, Nb approximately 10–16 ppm, Rb mostly 40–160 ppm). The median values and distribution ranges of Cr, Ni, Ti, V, Sr, Tl and Pb show a high degree of overlap, indicating that the two groups share broadly consistent patterns in key trace-element compositions. Although the overall trace-element distributions of the two groups show substantial overlap, the Tang-dynasty Yaozhou samples display slightly higher median concentrations of Zr, Nb, and Rb than those from Yingou cite. These elements are commonly associated with accessory mineral phases, including zircon (Zr), rutile or ilmenite (Nb), and mica or K-feldspar (Rb). Their modest enrichment in the Yaozhou samples may therefore reflect minor differences in the abundance of heavy-mineral or mica-bearing components within otherwise comparable clay deposits, rather than fundamentally distinct geological sources. Importantly, these variations are small relative to the total compositional ranges and do not disrupt the overall similarity of trace-element patterns between the two groups. Consequently, they are best interpreted as expressions of local raw-material heterogeneity within a shared or closely related geological basin.

The rare earth element (REE) distribution patterns for the ceramic bodies of Tang-dynasty black porcelain samples from the Yingou site and Tang-dynasty Yaozhou kiln black porcelain samples are shown in Fig. 6. As illustrated, the overall REE distribution characteristics of the two sample sets are broadly consistent: the contents of the light REEs from La to Nd are markedly higher than those of the other REEs, with log10 normalized values above 1. In addition, the REE distribution curves of the three sample groups are generally similar and follow nearly identical trends. These features indicate that the raw materials used to prepare the bodies of the two sets of black porcelain samples most likely derive from geologically similar sources.

According to historical records, the Yaozhou kiln industry expanded progressively in area from the Tang to the Song dynasty, and large-scale ceramic remains uncovered in subsequent archeological excavations led later generations to refer to the complex as the “ten-mile-long kiln site”. The porcelain clay used at the Yaozhou kilns was reportedly extracted from collapsed rock formations beneath the loess terraces on both banks of the Qishui River. In addition, “ni chi” clay was the principal body material used in the ancient Yaozhou kilns, with further sources located along the Xiaoqing River, at Tuhuang Gou and beneath nearby terraces17. These accounts indicate that more than one clay source existed in the vicinity of the ancient Yaozhou kiln sites18, which may also help to explain the slight differences in trace-element compositions observed in the ceramic bodies of the Yingou samples compared with those from the Yaozhou kiln19,20.

Rare-earth-element (REE) analysis in this study was conducted on the ceramic bodies rather than on the glaze layers. This methodological choice is based on the premise that ceramic bodies more directly preserve the geological signatures of primary clay raw materials, whereas glaze compositions are more strongly influenced by technological interventions, including flux addition, raw-material mixing, and melt homogenization during firing. These processes may partially overprint or obscure the original REE provenance signals.

Micromorphology and structural analyses

The cross-sectional structures of representative black porcelain samples from different periods and locations were examined using an optical microscope (OM) with extended depth of field. As shown in Fig. 7, the Tang-dynasty Yingou sample contains bubbles within the glaze and exhibits a fine black glaze layer; the body includes partially unmelted particles, has a beige tone and relatively coarse texture, and short needle-like crystals can be observed at the body–glaze interface. The Tang-dynasty Yaozhou kiln sample likewise contains bubbles in the glaze, with a dark-brown, relatively translucent glaze layer in which distinct layered color bands can be seen near the surface; the body is rough and heavy, densely packed with fine particles and gray in color, and the body–glaze interface is particularly prominent, displaying neatly arranged needle-like crystalline precipitates.

Representative samples were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD), and the results are presented in Fig. 8. As shown in the figure, representative black-porcelain samples from the Yingou site and the Yaozhou kiln display distinct diffraction peaks at 2θ ≈ 16.3°, 26°, 33°, 35°, 40.8° and 60°, which match the standard reference pattern for mullite (3Al2O3·2SiO2, PDF#89-2645). Characteristic peaks near 2θ ≈ 26.6°, 50° and 59° correspond to quartz (SiO2, PDF#65-0466), and the peak at around 2θ ≈ 21.9° is attributable to cristobalite (SiO2, PDF#39-1425). The diffraction-peak positions of the two sample groups are nearly identical over the range 2θ = 10°–80°, indicating that their main crystalline phases are essentially the same.

To further compare the compositions and contents of the ceramic bodies and glazes, EDS elemental mapping and semi-quantitative analysis were carried out on polished cross-sections of the samples. As shown in Fig. 9, the Si distribution in the bodies of T-YG-12 and T-YZY-7 exhibits pronounced blocky enrichment, which is most likely attributable to residual, incompletely melted quartz particles formed during firing. The spatial distribution of Si also differs between phases: in both T-YG-12 and T-YZY-7, Si enrichment in the glaze is markedly higher than in the body, whereas the Al distribution shows the opposite pattern, with stronger enrichment in the ceramic body than in the glaze. At the body–glaze interface, both T-YG-12 and T-YZY-7 display a distinct Ca-enriched band.

Figure 10 shows the crystalline phases at the body–glaze interface of representative Tang-dynasty black porcelain samples from the Yingou site and the Yaozhou kiln, as identified by Raman spectroscopy. The peaks marked in red in T-YG-12 (198, 484, 506, 556 and 768 cm−1) and T-YZY-7 (484, 506, 556 and 761 cm−1) correspond to anorthite. In addition, the peaks near 678 cm−1 (T-YG-12) and 667 cm−1 (T-YZY-7) are identified, on the basis of comparison with the Raman database, as O–Si–O asymmetric stretching vibrations in SiO2 crystals.In addition, the band at 205 cm−1 observed in T-YZY-7 is consistent with the characteristic Raman band of quartz, whereas the bands at 983 cm−1 in T-YG-12 and 999 cm−1 in T-YZY-7 are attributable to vibrations of the glassy phase21. This behavior is likely due to the crystals being located very close to the glaze layer, so that during Raman analysis the laser spot simultaneously excites signals from the adjacent glassy matrix22.

In addition to Raman bands attributable to anorthite, several spectral features observed in the low-wavenumber region (approximately 680–700 cm−1) may also be consistent with Fe–Ti oxide phases, such as ilmenite. In the present study, baseline correction was applied to enhance weak interfacial signals; however, this processing step can influence peak intensities and background characteristics, particularly in complex multiphase assemblages. Given the spectral overlap between silicate and oxide phases, together with the sensitivity of Raman spectra to baseline treatment, the identification of minor Fe–Ti phases should therefore be considered tentative.

Although anorthite is thermally stable up to ~1550 °C, its occurrence in archeological ceramics does not necessarily imply firing at such extreme temperatures. In this study, anorthite was detected exclusively at the glaze–body interface by micro-Raman spectroscopy and was absent from bulk-body XRD patterns, indicating its highly localized formation and low overall abundance. This phase is interpreted as an interfacial reaction product generated by CaO diffusion from the lime-rich glaze into the aluminosilicate body during high-temperature firing. Under liquid-phase conditions, anorthite may precipitate at temperatures significantly lower than its equilibrium stability limit (typically ~1200–1300 °C), yet remain confined to a thin reaction zone, where its weak diffraction signal is readily obscured by dominant crystalline phases such as mullite and quartz, as well as by the amorphous glassy matrix. Owing to its high spatial resolution and sensitivity to minor phases, micro-Raman spectroscopy is therefore more effective for identifying such interfacial products. The coexistence of mullite, quartz, cristobalite, and interfacial anorthite thus reflects efficient glaze–body interaction and a mature firing technology, rather than anomalously high firing temperatures. The foregoing spectroscopic and phase analyses indicate that the Yingou black porcelains were produced using mature firing technology, yield high quality porcelains, and basically similar to Yaozhou kiln black porcelain.

The occurrence of anorthite at the glaze–body interface, together with possible minor Fe–Ti oxide phases, reflects localized interfacial reactions during high-temperature firing rather than equilibrium bulk crystallization. Importantly, these Raman observations should be interpreted as micro-scale interfacial phenomena, rather than as direct indicators of bulk firing temperature or kiln-specific technological markers. Their significance lies primarily in demonstrating effective glaze–body interaction and a mature firing process shared by both the Yingou and Yaozhou samples.

Discussion

On the basis of the foregoing experimental analyses and discussion of the results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

The major oxides in the bodies of both sample groups display the typical high alumina, low silica characteristics of northern porcelains. The glaze are calcium-alkaline glaze dominated by CaO+MgO, with Na2O + K2O as subordinate fluxes, and the relatively high Fe2O3 contents are consistent with the development of black glaze coloration. XRD analyses show that the principal crystalline phases in the bodies of both groups are mullite, quartz and cristobalite. Cross-sectional microscopy combined with elemental mapping reveals similar body–glaze transition zones and Ca-enriched bands, and Raman spectroscopy reveals the presence of calcium aluminosilicate phases at the glaze–body interface, together with possible minor Fe–Ti oxide phases, suggesting localized interfacial reactions during firing. When considered alongside XRD results and microstructural observations, these features indicate effective glaze–body interaction and broadly comparable firing practices, rather than serving as standalone indicators of firing temperature or kiln attribution.

The shapes of the rare earth element distribution curves and the positions of their peaks and troughs are generally consistent, indicating that the clay raw materials derive from similar geological sources. Although trace elements such as Zr, Nb and Rb are slightly enriched in the Yaozhou samples, the overall trace-element patterns overlap closely and remain within the normal range of variability expected for the raw materials.

Integrating major-element and trace-element chemistry, rare-earth-element patterns, mineralogical phases, and microstructural features, the Tang-dynasty black-glazed porcelains from the Yingou site and those from the Yaozhou kiln exhibit a consistently high degree of similarity. These results support the interpretation that both groups were produced within closely related raw-material and technological systems, most plausibly linked to a shared or overlapping geological resource base and a common technological tradition. While the current dataset does not allow unequivocal attribution to a single production center, it provides strong evidence for a tight provenance relationship between Yingou site and Yaozhou kiln black-glazed porcelains during the Tang dynasty.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its tables).

References

Xia, J. & Wang, D. TL dating of porcelains from Fuping Yingou remains in Shaanxi (富平银沟遗址陶瓷标本热释光测年研究). China Ceram. S1, 50–65+190 (2017).

Li, C. & Zhang, X. Considerations to Fuping Yingou ceramic specimens from technological perspective (关于富平银沟遗址陶瓷标本的工艺思考). China Ceram. S1, 107–121+189 (2017).

Liu, S. & Li, Q. Chemical analysis of glaze and body for ceramic wares collected from Yingou site in Fuping (富平银沟遗址陶瓷标本胎釉化学成分检测). China Ceram. S1, 66–81+189 (2017).

Zhu, T. et al. Study on the provenance of Xicun Qingbai wares from the northern Song dynasty of China. Archaeometry 54, 475–488 (2012).

Wang, M., Zhu, T., Zhang, W., Mai, D. & Huang, J. Provenance of Qingbai wares from Shabian kiln archaeological site in the Northern Song dynasty using XRF and LA-ICP-MS*. Archaeometry 62, 538–549 (2020).

Shen, J. et al. Chemical and strontium isotope analysis of Yaozhou celadon glaze. Archaeometry 61, 1039–1052 (2019).

Shi, K., Yong, M. & Dong, L. Composition and microstructure of Yuan Dynasty Jun glazed stoneware from Yanjialiang site, Inner Mongolia. China npj Herit. 13, 157 (2025).

Shi, P. et al. Coloring and translucency mechanisms of Five dynasty celadon body from Yaozhou kiln. Ceram. Int. 43, 11616–11622 (2017).

Hay, R., Haider, S., AlTantawi, A. & Celik, K. Color modification of ceramics with controlled firing. Ceram. Int. 50, 566–574 (2024).

Yang, T. et al. Mixed-alkaline earth effects on the network structure and properties of alkali-free aluminosilicate glasses. J. Non-Crystall. Solids. 634, 122984 (2024).

Gao, S. & Wedepohl, K. The negative Eu anomaly in Archean sedimentary rocks: implications for decomposition, age and importance of their granitic sources. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 133, 81–94 (1995).

Bishop, R., Rands, R. & Holley, G. Ceramic compositional analysis in archaeological perspective. Adv. Archaeol. Method Theory 5, 275–330 (1982).

Boynton, W. Cosmochemistry of the rare earth elements: meteorite studies. Rare Earth Elem. Geochem. 16, 63–114 (1984).

Evensen, N., Hamilton, P. & O’Nions, R. Rare-earth abundances in chondritic meteorites. Geochim. et. Cosmochim. Acta 42, 1199–1212 (1978).

Allen, R. et al. A geochemical approach to the understanding of ceramic technology in predynastic Egypt. Archaeometry 24, 199–212 (1982).

Li, B., Kuang, T., Wang, C. & Wang, X. ICP-MS trace element analysis of Song dynasty porcelains from Ding, Jiexiu and Guantai kilns, north China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 32, 251–259 (2005).

Tian, Z. Tongguan County Annals (Tongguan Xianzhi), Vol. XI: Mining Annals(〈〈同官县志》卷十一:矿业志. (Xi’an: Xijing Taihua Printing House, 1944). (in Chinese)

Zhang, K. Archaeological Research on Yaozhou Kiln Celadon from the Five Dynasties to the Song and Jin Dynasties (〈〈五代宋金耀州窑青瓷的考古学研究〉〉). (Doctoral dissertation, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2025). (in Chinese)

Ellery, F. Ceramic studies using portable XRF: from experimental tempered ceramics to imports and imitations at Tell Mozan, Syria. J. Archaeol. Sci. 90, 12–38 (2018).

Cui, J. et al. Chemical analysis of white porcelains from the Ding Kiln site, Hebei Province, China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 39, 818–827 (2012).

Chen, P. et al. Nondestructive study of glassy matrix of celadons prepared in different firing temperatures. J. Raman Spectrosc. 52, 1360–1370 (2021).

Colomban, P. On-site Raman identification and dating of ancient glasses: a review of procedures and tools. J. Cult. Herit. 9, 55–60 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52272020), the Shaanxi Province Technology Innovation Guidance Special Project (2024QY-SZX-04), and the Central Guidance Fund for Local Science and Technology Development Project (2024ZY-JCYJ-04-06).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Caoyuan Ma was responsible for the experimental work and wrote both the initial draft and the final version. Hongjie Luo is responsible for overall supervision and providing methodology. Fen Wang was involved in the experimental design and drafting of the manuscript. Jianfeng Zhu provided financial support and experimental design. Deyi Wang provided samples support. Tian Wang provided support for the testing equipment. Chen Chen provided the parts of the article manuscript involved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to publish

All authors have agreed to the publication of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, C., Luo, H., Wang, F. et al. Provenance study of Tang-dynasty black-glazed porcelains unearthed at the Yingou site. npj Herit. Sci. 14, 48 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02321-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02321-0