Abstract

During the Eastern Han Dynasty, privately produced bronze wares dominated the market, with utilitarian vessels such as Xi and Hu demonstrating significant commercialization. However, there has been no research from an archaeometallurgical perspective on the commercialization of bronze wares during the mid-to-late Eastern Han period. This study analyzes the metallurgical features of four Xi excavated from the Huofeng hoard in the Wuling Mountains. The four Xi are all lead-tin bronze and were cast, which retains the low-tin characteristic inherited from the Western Han period. Coupled with the lead isotope ratios and the morphological characteristics of the studied Xi, we believe that the four bronze Xi should be products of the commercialization of bronzes in southwestern China during the middle to late Eastern Han Dynasty. The low tin content and the casting of bronze Xi should be related to the commercialization aimed at saving production costs and improving production efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bronzes of the Three Dynasties (2070-256 BCE, refer to Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties) have commanded sustained academic attention due to their profound cultural significance. In comparison, the study of bronzes from the Han Dynasty (202 BCE-221 CE) and later periods remains fragmentary, hindering the reconstruction of the development and evolution of ancient bronzes. Additionally, the ritual significance of bronzes during the Han Dynasty had been greatly diminished, shifting towards practical functions. Nevertheless, bronzes still hold an important position in daily life, distinguished by their substantial quantity, typological diversity, refined decorative artistry, and rich inscriptions1.

The production and management systems of bronze artifacts during the early Western Han Dynasty (202 BCE-8 CE) encompassed state-operated and privately-operated systems. State-operated production was stratified into central and local administrative tiers, while private-sector manufacturing involved participation from wealthy merchant conglomerates and local feudal lords2. Scholars have discovered through lead isotope ratio analysis of bronze wares excavated from Han Dynasty tombs across multiple regions that the mineral materials used in early Western Han were relatively complex, while those from the middle and late Western Han periods were more uniform3. These changes in raw material sources may reflect the centralized management of bronze production by the central government after the middle period of the Western Han Dynasty. During the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-221 CE), the production mechanism of bronze wares changed. Official workshops largely withdrew from the manufacturing of bronze objects, with only those related to the national economy and people’s livelihood, such as measuring implements and weapons, continued to be manufactured by the official workshops4. Therefore, in the middle and late Eastern Han Dynasty, a large number of private workshops emerged, enabling a large amount of bronzes to be produced and put into the market, which further promoted the commercialization of bronzes.

The previous studies on Han Dynasty bronze have predominantly focused on alloying techniques, ore sources, and resource circulation of unearthed Western Han bronzes5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. The research on Eastern Han Dynasty bronzes has been relatively scarce. Lin et al.15, Huang et al.16,17, Jin et al.18, Sun et al.19, and others have conducted scientific testing and analysis on Eastern Han bronzes unearthed in Binzhou (Hunan), Wuchuan (Guizhou), Qiaojiayuan cemetery (Hubei), and Zhaotong (Yunnan), respectively. Zhangsun analyzes the production and dissemination of bronze mirrors during the Western and Eastern Han dynasties from the perspective of lead isotope ratios20,21. Ma et al. have explored the source of the ores and the changes on Wuzhu coins excavated from the Chengdu and Tianjin regions during the Eastern Han Dynasty22,23.

During the Eastern Han period, the commodification of bronze ware was evident, but no specialized study on highly commercialized bronze wares such as Xi (washing vessels) and Hu (pots) in the middle and late Eastern Han period has been found in existing research. This hinders our understanding of the production mechanisms and circulation of bronzes from the perspective of archaeometallurgy. Therefore, this study conducts a scientific analysis on Xi excavated from the Huofeng hoard in the Wuling Mountain. This investigation holds pivotal significance for elucidating bronze commodification processes and socioeconomic development.

Methods

Materials

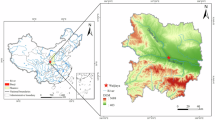

The Wuling Mountain Area (Fig. 1) derives its name from the Wuling Mountain, which is located at the intersection of Hunan, Hubei, Guizhou, Guangxi, and Chongqing. It borders the provinces of Hunan and Hubei in the east, connects to Bashu (Sichuan and Chongqing) to the west, links to the Guanzhong region to the north, and extends to Guangdong and Guangxi to the south. Serving as a vital corridor between central and western China, it also acts as an intermediary zone for the diffusion of Central Plains culture to the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau. During the Warring States Period (475–221 BCE), the Wuling region was incorporated into the administrative territory of the Chu State. As recorded in Zhan Guo Ce (战国策, a state-classified historical text compiled by Liu Xiang of the Western Han Dynasty, primarily documents the political doctrines and strategies of the School of Vertical and Horizontal Alliances during the Warring States period: “In the west of Chu’s territory lay Qianzhong and Wu Commanderies”24. This indicates that the Chu State had already established the Qianzhong Commandery in the Wuling region. After the establishment of the Han Dynasty, to effectively govern the local areas, Qianzhong Commandery was changed to Wuling Commandery, which was under the jurisdiction of Jingzhou. During the Eastern Han Dynasty, the territorial boundaries of Wuling Commandery remained largely identical to those established during the Western Han Dynasty.

Since the 1950s, bronze hoards have frequently been discovered in the Wuling Mountain Area, with the unearthed artifacts mainly including Xi, Hu, Wan (bowls), Bianzhong (chime bells), etc.

In 1981, a hoard pit was discovered on the north bank of the Yangtze River in Huofeng, Badong County. A total of 21 bronze artifacts were unearthed, including various types such as chime bells, Xi (Fig. 2a, b), Hu, Fu (cauldrons), and Fang (square-mouthed jars). Bronze Xi and Hu from the Eastern Han Dynasty exhibit distinctive characteristics, with their forms demonstrating a trend toward unified style. The two intact Xi (Fig. 2a, b) unearthed from the Huofeng hoard are largely similar in characteristics to those discovered in the southwest region, featuring a wide-flared or dish-shaped mouth, a globular belly, and a flat base4. The four Xi discussed in this study are severely damaged, but some of their features can still be exhibited, such as a wide flared rim and flared mouth (BDHF-1), and string patterns on the belly(BDHF-2, BDHF-3). These features are common characteristics of bronze Xi in the Middle Eastern Han Dynasty. Detailed specifications can be found in Table 1 and Fig. 2.

Analytical methods

Before observing the microstructure, the samples were first sanded to remove contaminants and patina from the surface and then mounted with epoxy resin. After that, the inlaid samples were polished and ground with metallographical sandpaper of different grits. Then the samples were etched with an alcoholic ferric chloride solution (FeCl3), and the metallographic structure images were taken using a Keyence VHX-2000 digital microscope in the Technological Archeology Laboratory of Anhui University.

Scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) analysis were conducted in the Modern Experimental Technology Center of Anhui University. A German Zeiss Crossbeam 550/550 L electron beam/ion beam dual-beam electron microscope was used, equipped with a British Halifax Rd, HP12 3SE type energy dispersive spectrometer. For the electron beam system, the optimal resolution is ≤ 0.7 nm @ 15 kV, and the STEM resolution is ≤0.6 nm @ 30 kV. For the ion beam system, the accelerating voltage ranges from 500 V to 30 kV, and the maximum beam current is ≥ 100 mA. All samples were processed under high-vacuum conditions. During the detection, the accelerating voltage was set to 15 kV, with a detector dead time of approximately 30 s. There were no standard samples in the test, and the detection limit of the EDS measurement is 0.1%. Each sample was selected from 3 to 5 areas for surface scanning detection, and then the average value was calculated.

Lead isotopes were carried out in the Continental Dynamics Laboratory of Northwestern University, using a Nu Plasma ICP-MS from Nu Instruments, UK. During the testing, samples were first rinsed with ultrapure water and anhydrous ethanol to prevent contamination, then digested using high-pressure and temperature bomb digestion to extract Pb. After separation, purification, and evaporation, the Pb element is analyzed and determined using MC-ICP-MS. One quality control sample plus four samples and one quality control sample were conducted in sequence. The quality control sample used was NBS 981 (certified isotopic ratios: 208Pb/206Pb = 2.167710, 207Pb/206Pb = 0.914750, 206Pb/204Pb = 16.9405, 207Pb/204Pb = 15.4963, 208Pb/204Pb = 36.7219). The measurement error ranges for the overall analysis of 206Pb/204Pb, 207Pb/204Pb, and 208Pb/204Pb are 0.0003–0.0007, 0.0003–0.0004, and 0.0010–0.0011, respectively.

Results

Elemental composition analysis

In this study, alloy composition analysis was performed on four Xi, with results summarized in Table 2 (The results of each detection are shown in supplementary material Table S1). All samples consist of lead-tin bronze, showing copper content ranging from 82.11% to 84.41% (mean: 83.52%), tin content between 6.16% and 7.97% (mean: 6.78%), and lead content from 8.98% to 9.59% (mean: 9.31%). The four bronze Xi have a similar lead-tin content, suggesting a potential origin from the same production batch. Notably, except for BDHF-4, iron, silver, and other elements commonly analyzed in compositional studies were undetected, likely due to concentrations below the detection limits of EDS. This absence further indicates that the raw materials probably underwent intensive refining or remelting processes15.

Metallographic analysis

This article conducted a metallographic analysis on four Xi (Fig. 3), and combined with scanning electron microscopy to perform EDS analysis on the inclusions in the samples (Fig. 4).

Metallographic analysis reveals that all four bronze Xi were cast, with no signs of secondary processing or heat treatment observed. Specimens BDHF-1 and BDHF-2 display essentially identical microstructures, characterized by copper-tin α-solid solution, with a small amount of isolated distribution of (α + δ) eutectoid structures. The BDHF-3 and BDHF-4 matrices are copper-tin α-solid solution dendrites with intragranular segregation, and (α + δ) eutectoid structure distributed between crystals. Backscattered electron imaging identifies scattered lead particles and minor sulfide inclusions (Fig. 4). In contrast, BDHF-4 contains larger lead particles due to its slightly elevated lead content. Both BDHF-1 and BDHF-4 exhibit increased shrinkage porosity, a phenomenon attributed to the broad solidus-liquidus temperature range of their copper-tin alloy. This extended solidification interval impaired molten metal fluidity, resulting in dispersed shrinkage cavities and microporosity formation within casting cross-sections during cooling15.

Lead isotope analysis

The results from MC-ICP-MS detection (Table 3) show that the range of the 206Pb/204Pb ratio for the four bronze Xi from Huofeng is 18.5155 to 19.1664, the range of the 207Pb/204Pb ratio is 15.7118 to 15.7727, the range of the 208Pb/204Pb ratio is 38.9449 to 39.5608, the range of the 208Pb/206Pb ratio is 2.06408 to 2.10338, and the range of the 207Pb/206Pb ratio is 0.822947 to 0.848581. It is generally considered that geologically highly radiogenic lead is 207Pb/206Pb < 0.84, while the common lead is 207Pb/206Pb > 0.8425. The 207Pb/206Pb ratios of samples BDHF-1, BDHF-2, and BDHF-3 are all less than 0.84, indicating that they are highly radiogenic lead. The 207Pb/206Pb ratio of sample BDHF-4 is 0.848581, greater than 0.84, indicating that it is common lead. Regarding the indicative significance of lead isotopes, when the lead content in bronze artifacts exceeds 2%, the lead is considered intentionally added, reflecting the source characteristics of the lead ore26. In this study, the lead content in all four Xi exceeds 2%; hence, their lead isotope ratios indicate the source of the lead material.

To demonstrate the lead isotope characteristics of the four bronze samples from Huofeng, we plotted a scatter diagram with 207Pb/204Pb-206Pb/204Pb and 208Pb/204Pb-206Pb/204Pb, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5, the lead isotope ratios of the four Huofeng bronze Xi are concentrated in areas A and B, respectively. The common lead sample BDHF-4 falls into area A, while the three highly radiogenic lead samples (BDHF-1, BDHF-2, and BDHF-3) exhibit nearly identical isotopic ratios, scattered in area B. Combining the alloy composition, the three highly radiogenic lead samples should be classified as products from the same production batch.

During the Eastern Han Dynasty, bronze Xi was popular in southern China, particularly those produced in the southwestern regions of Shu Commandery and Zhaotong, which became widely circulated commodities across various regions. And the high-radiogenic lead bronze artifacts have also been frequently discovered in southwestern China16,19,27,28. Based on existing published data, we conducted a comparative study on the lead isotope ratios of Huofeng bronze artifacts with those of Eastern Han Dynasty bronzes unearthed from Wuchuan (Guizhou Province)16,17, Zhaotong (Yunnan Province)19, and Heimajing (Yunnan Province)29 in southwestern China (Fig. 1).

As shown in Fig. 6, the lead isotope ratios of Huofeng common-lead bronzes (BDHF-4) cluster closely with those of common-lead bronzes unearthed from Wuchuan, Zhaotong, and Heimajing. Meanwhile, the highly radiogenic lead bronze Xi from Huofeng exhibits the closest isotopic affinity to bronzes from Wuchuan. This indicates that the lead material sources of Huofeng common-lead Xi are similar or identical to those of bronzes from Wuchuan, Zhaotong, and Heimajing. Similarly, the three highly radiogenic lead bronze Xi share comparable or identical lead sources with the highly radiogenic bronzes from Wuchuan.

The Yunnan-Guizhou region, located in the southwest of China, is rich in mineral resources. It is also the main distribution area for highly radiogenic lead deposits in China. In the year 69 CE, the Eastern Han Dynasty established the Yongchang Commandery (present-day Yunnan Province) in the ancient Ailao region (present-day central and southern Yunnan Province), incorporating all of the southwestern barbarian areas into the Han imperial administration. Historical texts such as the Houhanshu (后汉书, a book of historical annal-biography compiled by Fan Ye, a historian from the Southern Dynasties’ Song period (420-479 CE), documenting the history of the Eastern Han Dynasty) and Huayang Guo Zhi (华阳国志, a regional gazetteer written by Chang Qu during the Eastern Jin period (317-420 CE), provides unparalleled insights into the ethnic diversity, administrative systems, and ecological adaptations of Southwest China) frequently document mineral resources in southwestern China. For instance, the Houhanshu states that Yongchang Commandery “produces copper, iron, lead, tin, gold, silver, etc”30. Similarly, the Huayang Guo Zhi notes: “Tanglang County (present-day Qiaojia County in Yunnan Province) produces silver, lead, copper, nickel alloy, copper, and medicinal herbs”31.

According to metallurgical studies of unearthed bronzes from the Yunnan-Guizhou region, the ore materials for Zhaotong’s common-lead bronzes originated from the metallogenic zone along the Sichuan-Yunnan-Guizhou border, while highly radiogenic lead bronzes utilized lead ores from central Yunnan’s mining region19. Eastern Han Dynasty bronzes from Wuchuan were sourced from four different mines, with at least three located on the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau. Notably, the lead materials for highly radiogenic lead bronzes were likely derived from lead deposits containing highly radiogenic lead in Zhaotong, northeastern Yunnan Province16. The Heimajing bronze wares primarily used ore materials from local mines in Gejiu, Yunnan29. It is evident that the mineral resources in the Yunnan-Guizhou region were already being exploited and utilized on a large scale during the early Eastern Han Dynasty.

Referring to the geochemical provinces established by Zhu32, we found that the lead isotope ratios of Huofeng bronzes fall within the geochemical provinces of southern China (206Pb/204Pb > 18.4). Based on the comparative study of lead isotope ratios in bronzes, we selected lead isotope data from galena in the Yunnan region28,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 and lead-zinc deposits in Guizhou42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49 for comparative study to further explore the source of lead materials for Huofeng bronzes.

As shown in Fig. 7, the lead isotope ratios of common-lead bronzes from Area A of the Huofeng site exhibit significant overlap with those of lead-zinc deposits in the Yunnan-Guizhou metallogenic belt, suggesting a potential shared lead source from this region. Meanwhile, the three highly radiogenic lead bronzes from Area B demonstrate isotope ratios that align more closely with lead-zinc deposits in central and eastern Yunnan. This correlation gains particular significance when considering China’s geological context: anomalous lead deposits are predominantly concentrated in Yunnan Province, where multiple mining districts document the coexistence of both common lead and highly radiogenic lead50,51. These patterns strongly indicate that the lead materials for the three highly radiogenic lead bronze artifacts were likely procured from central and eastern Yunnan.

Discussion

During the Eastern Han Dynasty, the production and management of bronze artifacts gradually shifted from state monopolies to privatized operations, with marked commercialization of bronze wares. The types of artifacts made during this period were mainly focused on practical daily use items, including bronze basins, pots, plates, bowls, etc. Two major bronze production centers emerged at that time: one in southwestern China, represented by Zhuti-Tanglang Xi, and another in the Lingnan region, characterized by incised-pattern bronzes such as Ou (an ancient bronze measuring vessel), Qi (cookware), and bowl4,52. These products began to gradually disseminate nationwide. To cater to the psychology of buyers and promote sales, some producers often crafted bronze artifacts with auspicious inscriptions and so on, as well as a large number of decorations. These abundant ornamentations, including double-fish pattern, sheep pattern, egret pattern, ding pattern, and coin pattern, reflect the practical pursuit of prosperity and auspiciousness for descendants4.

During the Eastern Han Dynasty, bronze Xi bearing the inscriptions “Zhuti”, “Tanglang” or “Zhuti- Tanglang” have been discovered in the greatest quantities. The workshops producing the Zhuti-Tanglang Xi included both state-run establishments under local supervision53 and private workshops54, and the products they manufactured were directly distributed outward from the place of production55. To date, 85 Zhuti-Tanglang Xi bearing definitive chronological and provenance inscriptions have been documented (supplementary material Table S256). These artifacts have been found extensively throughout China, with reported discoveries in Yunnan, Sichuan, Shandong, Guizhou, Hubei, Henan, Shaanxi, Hunan, Liaoning provinces and Chongqing city, demonstrating that these had achieved interregional circulation. Supplementary material Table S2 reveals that the inscriptions are uniform in content and format. Primarily comprising the reign era and place of manufacture, lacking family names and rarely containing auspicious phrases. The commercialization of bronze Xi during the Eastern Han Dynasty is evidenced by its mass production, standardized inscriptions, and interregional circulation.

With the excavation of archeological materials, a substantial number of commercially distributed bronze artifacts have been excavated in the Wuling Mountain area. Notably, a bronze Xi discovered in the Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture of western Hunan features a clerical script inscription cast on its interior base, stating “Yangjia 3rd Year, manufactured in Zhuti”, and another significant find from Yangdong, Xianfeng (Hubei Province) is a bronze Xi bearing the inscription “Yongyuan 12th Year, manufactured in Tanglang”57. These archeological discoveries demonstrate that bronze Xi produced in the “Zhuti-Tanglang” region of Yunnan-Guizhou had already entered commercial circulation as far as the Wuling Mountain area during the Eastern Han Dynasty. The characteristic features of “Zhuti-Tanglang” bronze Xi include string patterns on the vessel belly and cast designs or inscriptions on the base. Typical decorative motifs consist of double fish patterns, fish-and-heron combinations, and sheep motifs58. Three particularly illustrative examples from the Wuling Mountain region include: Two bronze Xi unearthed at Datianba, Enshi, featuring both double-fish patterns and inscriptions reading “Yi Hou Wang” and “Made in the 12th year of Yongyuan”59. A bronze Xi from Tunbao, Enshi, displaying a double-fish pattern at its base59. These artifacts share distinct stylistic and technical characteristics strongly suggesting Zhuti-Tanglang origins. The accumulated evidence indicates that the majority of Eastern Han bronze artifacts found in the Wuling Mountain area were commercially produced goods, reflecting established trade networks and standardized manufacturing practices during this historical period.

Additionally, the phenomenon of commercialization is also well-reflected in the Huofeng bronze Xi. The Huofeng Xi exhibits low lead and tin contents. The characteristically low tin content with significant fluctuations represents a technical hallmark of Western Han Dynasty bronze wares15. The potential connection between low-tin bronze and Han Dynasty commercialization has been proposed in previous works6,15. Generally, cast bronze with 5-10% tin content achieves both good malleability and adequate strength60. Low-tin bronze vessels were prevalent throughout the Han Dynasty, with tin content mostly below 10%. For instance, most Western Han bronzes from the Paomadi cemetery in Hubei Province display tin levels between 2.60% and 13.80%61; three bronze artifacts from the Tianchang Western Han tomb in Chuzhou, Anhui Province, exhibit tin contents from 5.58% to 6.21%8; bronze containers from Fengpengling-Taohualing in Changsha, Hunan, range from 2.31% to 8.85% tin12; and the majority of bronze vessels from Heimajing contain tin levels between 6.6% and 8.60%29. As shown above, the tin levels observed in Han Dynasty bronzes generally satisfied the functional demands of copper alloy artifacts, demonstrating that the alloying technology had already been mastered during the Western Han period. From Fig. 8, it can be seen that the composition of the four Xi from Huofeng is similar to that unearthed during the Western Han Dynasty, basically continuing the low tin characteristics of the Western Han Dynasty.

During the early Western Han period, the imperial administration implemented relatively lenient economic policies to stabilize social order and revive production. These measures relaxed state control over metal resources, permitting diverse entities to participate in bronze production and circulation, ultimately resulting in free-market commodity circulation. By the mid-to-late Western Han era, the government enforced monopolies on salt and iron production to consolidate state authority. Concurrently, bronze manufacturing became a state-controlled industry primarily managed by central and regional government workshops, with some official supervision extending to private workshops62. During Emperor He’s reign in the Eastern Han Dynasty, the policy shifted to “abolish salt and iron monopolies, permitting private entities to engage in salt boiling and metal casting”30, which led to the proliferation of private workshops and intensified bronze commercialization. This historical progression demonstrates that private workshops persisted throughout both the Western and Eastern Han periods. Driven by commercial profit motives, these private operations systematically minimized manufacturing costs while maintaining functional bronze quality. Given the scarcity of tin resources and limited mining capabilities during the Han period6, reducing tin usage while preserving bronze functionality became a key cost-saving strategy. The alloy composition of Huofeng bronze Xi shows no significant deviation from typical Western Han characteristics, maintaining low-tin ratios with an average tin content of 6.78% that meets both bronze performance requirements and practical usage needs. As commercial bronze production typically involved large-scale manufacturing, the reduced tin content likely reflects deliberate cost reduction measures.

In addition, in terms of manufacturing techniques, all four Huofeng bronze Xi were made by casting, demonstrating distinct differences from the manufacturing techniques of Western Han Xi. Open-mouthed vessels such as bronze basins, bowls, and washbasins were particularly suited for hot-forging techniques. This process enhanced ductility while producing thinner walls, thereby conserving raw materials61. Following increased government control over bronze production during the mid-to-late Western Han, bronze ware styles became remarkably standardized4. Existing research confirms that Western Han bronze basins were predominantly manufactured through hot forging (supplementary material Table S3). Chadwick’s simulated forging experiments on 5-30% tin bronzes identified a ductile forging zone at 200–300 °C for alloys below 18% tin content, making them suitable for controlled hot-working63. Statistical analyses of Western Han bronze Xi reveal tin contents ranging from 2.67% to 16.90% (supplementary material Table S3), aligning closely with the tin thresholds for low-temperature hot-forging. While Eastern Han bronze Xi maintained similar alloy compositions to their Western Han counterparts, their manufacturing techniques shifted decisively toward casting processes, with hot-forging becoming markedly less prevalent. This technological transition likely responded to commercial production demands. Commercialized bronze manufacturing required enhanced production efficiency, and casting offered distinct advantages over hot-forging through higher output rates, simplified operational processes, and better compatibility with large-scale production systems - all crucial factors for rapid market responsiveness.

During the Eastern Han Dynasty, bronze production became predominantly privatized, with evident commercialization of copperware. The southwestern region emerged as one of China’s principal bronze production centers, distributing utilitarian objects such as bronze Xi nationwide. Although the Huofeng bronze Xi were severely damaged, the surviving portions still exhibit distinctive features such as folded lips and raised ribbed patterns on the abdomen, which align with characteristics of bronze Xi from southwestern China. When combined with lead isotope ratios indicating their lead materials originated from the Yunnan-Guizhou metallogenic belt, along with their low-tin composition and cast characteristics, these four bronze Xi should be identified as products of commercial circulation. Their low-tin composition and adoption of casting techniques reflect producers’ strategic choices to minimize costs and optimize production efficiency.

The government loosened restrictions on bronze production, accelerating its commercialization in the Eastern Han Dynasty. As bronze artifacts circulated as commodities, they not only promoted the development of the commodity economy but also strengthened regional economic exchanges within the unified Han imperial realm. The four Xi from the Huofeng hoard indirectly demonstrate bronze commercialization and economic interaction between the Wuling Mountains and southwestern China, providing important insights into understanding socioeconomic conditions and daily life during the Eastern Han period.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

References

Du, Q. History of Chinese Bronzes (Forbidden City Publishing House, Beijing, 1995).

Wu, X. A study of the modes of management used to produce bronze vessels in the Han Dynasty and their development as seen from inscriptions. Palace Mus. J. 4, 100–107 (2007).

Yang, D. et al. From diversity to monopoly: major economic policy change in the Western Han Dynasty revealed by lead isotopic analysis. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 15, 1–14 (2023).

Wu, X. On the integration of bronze ware in the Qin and Han Dynasties. J. Zhejiang Univ. 52, 116–125 (2022).

Chen, D., Luo, W., Zeng, Q. & Cui, B. The lead ores circulation in Central China during the early Western Han Dynasty: a case study with bronze vessels from the Gejiagou site. PLoS ONE 13, e0205866 (2018).

Zeng, Q., Chen, D., Cui, B. & Luo, W. Preliminary scientific analyses and studies of bronze wares unearthed from the Gejiagou site, Xichuan County. Nanyang City Mus. 2, 89–96 (2020).

Zhao, F., Li, X. & Zhang, Y. Technical study of bronze objects excavated from the Kele Cemetery, Guizhou Province. China Cult. Herit. Sci. Res. 3, 81–86 (2012).

Yan, D., Qin, Y., Chen, Q. & Zhang, Z. Research on metal objects unearthed from Western Han Dynasty Tombs in Tianchang County. Nonferrous Met. 9, 56–61 (2011).

Lv, L. Study of the mineral source of Western Han bronzes unearthed in Guangzhou. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 5, 27–34 (2023).

Li, Q., Wei, G. & Gao, S. Scientific analysis on the Han bronze wares unearthed from Xiangyang, Hubei Province, China. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 15, 10 (2023).

Hu, Y., Li, W. & Hu, D. A preliminary analysis of the manufacturing technology of the bronzes unearthed from the main chamber of the tomb of Marquis of Haihun in Jiangxi. Cult. Relics South. China 3, 209–218 (2021).

Hu, P. et al. The production of bronze wares of the Changsha State in the Western Han Dynasty—a case study of the Fengpengling-Taohualing cemetery in Changsha. Hunan Prov. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 17, 103 (2025).

Liu, Z., Yang, Y. & Luo, W. A lead isotope study of the Han Dynasty bronze artifacts from Liangshan Yi autonomous prefecture museum, Sichuan Province, southwest China. Curr. Anal. Chem. 12, 553–559 (2016).

Qin, Y., Li, S., Yan, D. & Luo, W. Scientific analysis of hot forged bronze vessels from the Eastern Zhou to the Qin and Han Dynasties unearthed in Hubei and Anhui. Cult. Relics 7, 89 (2015).

Lin, Y. & Luo, S. Analysis of the bronze wares in the southern Jingzhou (Chenzhou area) during the Han Dynasty and related problems of the Han Dynasty bronze industry. Cult. Relics South. China 3, 134–146 (2023).

Huang, M., Wu, X., Tao, L. & Shi, M. Study on mineral sources of Eastern Han Period bronzes in Wuchuan, Guizhou. Nonferrous Met. 4, 114–120 (2022).

Huang, M. et al. Wuchuan bronzes and cinnabar mining immigrants during the Qin and Han Dynasties—new perspectives from typological and lead isotope analysis. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 13, 198 (2021).

Jin, R., Luo, W. & Wang, C. Metallographical and elemental analysis of the bronzes of the Warring State Period and the Eastern Han Dynasty excavated from Qiaojiayuan burial site in Yunxian, Hubei Province. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 2, 7–14 (2013).

Sun, S., Zhang, R., Wei, G. & Zhang, C. Regionalism and diversity: the supply characteristics of metal resources in Southwestern China during the Eastern Han dynasty reflected by the bronzes from Zhaotong, Yunnan Province. Eur. Phys. J. 139, 389 (2024).

Zhangsun, Y. The production and dissemination of Han Dynasty bronze mirrors—a perspective from lead isotope ratio analysis. Archaeol. Cult. Relics 9, 121–128 (2024).

Zhangsun, Y. et al. Lead isotope analyses revealed the key role of Chang’an in the mirror production and distribution network during the Han dynasty. Archaeometry 4, 685–713 (2017).

Ma, D., Gan, C. & Luo, W. Lead isotope and trace element analysis of the Wuzhu coins from Doujiaqiao hoard, Tianjin City, North China. Eur. Phys. J. 136, 193 (2021).

Ma, D. et al. How the metal supply for mintage shifts in the transforming monetary system of the Han Empire: archaeometallurgical study of the Wuzhu coins from the Guanghuacun cemetery, Chengdu, Southwest China. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 53, 104341 (2024).

Li, X. Zhan Guo Ce (in Chinese) (Harbin Publishing House, Harbin, 2011).

Liu, R. et al. Two sides of the same coin: a combination of archaeometallurgy and environmental archaeology to re-examine the hypothesis of Yunnan as the source of highly radiogenic lead in early dynastic China. Front. Earth Sci. 9, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2021.662172 (2021).

Wang, H. The theory, method, and practice of lead isotope archaeology. Identif. Apprec. Cult. Relics 3, 22–25 (2010).

Wang, X. et al. Preliminary discussion on the highly radiogenic lead in unalloyed copper artifacts of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty: starting from the Huili copper spearheads. Metals 10, 1252 (2020).

Jin, Z. China Lead Isotope Archaeology (University of Science and Technology of China Press, 2008).

Huang, M., Wu, X., Jiang, Z. & Jin, Z. Metal resources and Han immigrants: Lead isotope analysis of metal relics excavated from Heimajing cemetery in Gejiu, Yunnan, China. Archaeometry 4, 1 (2024).

Fan, Y. Houhanshu (In Chinese) (Zhonghua Book Company, 1965, Houhanshu (In Chinese), Beijing).

Chang, Q. Huayang Guo Zhi (in Chinese) (Qilu Press, 2010).

Zhu, B. The mapping of geochemical provinces in China based on Pb isotopes. J. Geochem. Explor. 55, 171–181 (1995).

Wang, W. Common lead isotope age test data. Yunnan Geol. 3, 294–309 (1984).

Isotope Geology Research Office of Geological Institute of Yichang. Basic Problems of Geological Research on Lead Isotopes (Geological Publishing House, 1979).

Pu, C. & Qin, D. The study of stable isotopes and fluid inclusions in Muding copper mine. Yunnan Geol. 2, 166–176 (1994).

Li, Q. & Bao, Z. Pb isotope constraints on the origin of the Jinding Zn-Pb deposit, Yunnan Province, China. Geochimica 47, 169–181 (2018).

Li, K. et al. New understanding on lead isotopic compositions and lead source of the Bainiuchang polymetallic deposit, southeast Yunnan, China. Geochimica 43, 116–130 (2013).

Peng, Z. et al. Lead isotope tracing study on the sources of Yunnan copper drums and some copper and lead ores. Chin. Sci. Bull. 37, 731–733 (1992).

Gao, Z. Lead isotope characteristics of major Lead-Zinc deposits in Yunnan. Yunnan Geol. 16, 359–367 (1997).

Li, G., Yang, G. & Yang, X. Sulfur and lead isotopic characteristics of volcanogenic silver polymetallic mineralization zone in the Huangtian-Xiaodong area, Jianshui, Yunna and their geological Implications. Earth Environ. 26, 21–26 (1998).

Xiao, X. et al. Metallogenic geochemistry characteristics of the lead-zinc polymetallic mineralization concentration area in Cangyuan, western Yunnan. Acta Petrol. Sin. 24, 589–599 (2008).

He, F. et al. Lead Isotope Compositions of Dulong Sn-Zn polymetallic deposit, Yunnan, China: contraints on ore-forming metal sources. Acta Mineral. Sin. 35, 309–317 (2015).

Tang, S. et al. Pb isotope composition of the Fulaichang lead-zinc ore deposit in Northwest Guizhou and its geological implications. Geotect. Metallog. 36, 549–558 (2012).

Zhou, J. et al. Sources of the ore metals of the Tianqiao Pb—Zn deposit in northwestern Guizhou province: constraints from S‚ Pb isotope and REE geochemistry. Geol. Rev. 56, 513–524 (2010).

Jin, C. et al. Characteristics of sulfur and lead isotope composition and metallogenic material source of the Nayongzhi Pb-Zn deposit, northwestern Guizhou Province. Mineral. Petrol. 35, 81–88 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. Sources of the ore-forming material from Yunluheba ore field in northwest Guizhou Province, China: constraints from S and Pb isotope geochemistry. Acta Mineral. Sin. 36, 271–276 (2016).

Zheng, C. The geological origin of the lead-zinc ores in northwestern Guizhou. J. Guilin Metall. Geol. Inst. 14, 114–124 (1994).

Zeng, G. et al. Pb isotopic composition of Guanziyao lead-zinc ore deposits in west Guizhou and its geological implications. Geotect. Metallog. 41, 305–314 (2017).

Yu, Y. et al. The metallogenic epoch and ore-forming material source of the Tangbian Pb-Zn deposit in Tongren, Guizhou Province: evidence from Rb-Sr dating of sphalerites and S-Pb isotope. Geol. Bull. China 36, 885–892 (2017).

Chen, Y., Mao, C. & Zhu, B. The lead isotope composition characteristics of Phanerozoic metal deposits in China and a discussion on their genesis. Geochimica 3, 215–229 (1980).

Qin, G. & Zhu, S. The genesis model and exploration prediction of the Jinding lead-zinc deposit. Yunnan Geol. 2, 145–190 (1991).

Wu, X. The archaeological research in bronze vessels from Han tombs in Zhejiang. Cult. Relics East 1, 37–55 (2018).

Yu, W. Archaeological Explorations of Ancient History (Cultural Relics Press, Beijing, 2002).

Xia, B. & Yang, F. The dissemination and function of the Zhutitanglang bronze Xi Vessels of the Eastern Han dynasty. South. Cult. Relics 1, 229–239 (2023).

Chen, Z. Compendium of Economic Historical Materials from the Han Dynasties. (Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing, 2008).

Wu, X. & Wei, R. Research on Shushitanglang wares. Acta Archaeol. Sin. 3, 365–380 (2021).

Lin, S. Eastern Han Dynasty bronze ware unearthed from a cellar in Jishou, Western Hunan. Hunan Archaeol. Ser. 0, 264–272 (1986).

Ma, Q., Ling, Y. & Peng, H. The History of the Dongchuan Copper Mine Development (Yunnan University Press, Kunming, 2017).

Hu, X. & Huang, B. Encyclopedia of the Tujia Nationality in China (Hubei People’s Publishing House, Wuhan, 2021).

Zhao, J. Cast Alloys and Their Melting (Mechanical Industry Press, Beijing, 1985).

Liu, J. et al. Scientific study on bronzes unearthed from the Paomadi Cemetery in Yicheng, Hubei Province. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 30, 114–125 (2018).

Song, Z. Copper casting handicraft industry of the Han Dynasty. J. Chin. Hist. Stud. 2, 13–25 (1985).

Chadwick, R. Effect of composition and constitution on the working and on some physical properties of the tin bronzes. J. Inst. Met. 64, 331–378 (1939).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Xiaoyu Liu, Anhui University, for assistance with Fig. 1. We also appreciate Yu Huang, Curator of the Badong County Museum in Hubei Province, for providing photos of the 2 intact bronze Xi (Fig. 2a, b) unearthed from the Huofeng hoard. This research was supported by the 2023 Anhui Province University Collaborative Innovation Project (Grant No. GXXT-2023-094), and the Grant recipient is Guofeng Wei.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. Wang: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis and investigation, and the writing of the original draft preparation; G. Wei: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing, and project administration; Q. Li: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis and investigation, and the writing of the original draft preparation; X. Wu: resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Wei, G., Li, Q. et al. Archaeometallurgical analysis of bronze Xi from Huofeng hoard in the Wuling Mountains, China. npj Herit. Sci. 14, 80 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02329-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02329-6