Abstract

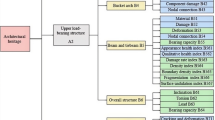

This study applies high-precision industrial metrology to the conservation of rammed-earth buildings (Tulou), establishing a structural health monitoring (SHM) framework based on 3D laser scanning and UAVs. By fitting “ideal” geometric reference surfaces through reverse engineering and incorporating efficient point cloud subsampling algorithms to significantly enhance processing efficiency, we utilized graphical data to develop specific deformation detection methods for irregular walls. This enabled the precise quantitative assessment of roundness, verticality, flatness, and column inclination. This approach effectively bridges the gap between advanced point cloud processing and traditional architectural pathology, successfully transforming assessments from subjective manual inspections to industrial-grade, objective geometric diagnoses. These findings not only enhance the scientific accuracy of World Heritage conservation but also provide a reproducible digital technical solution for the preservation of rammed-earth heritage globally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Architectural heritage serves as a critical repository of historical memory, cultural transmission, and artistic value, establishing vital connections between past and future generations. The preservation of architectural heritage is essential for shaping national identity and promoting sustainable development. Currently, the field is transitioning from reliance on inefficient traditional management systems toward the adoption of innovative conservation technologies1,2. Significantly, recent developments favor non-contact measurement techniques—including Terrestrial Laser Scanning. Close-Range Photogrammetry (CRP)3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-based oblique photogrammetry14,15,16,17,18. These methods are crucial for generating precise three-dimensional (3D) documentation of historic structures, effectively capturing external landscapes and complex interior spatial configurations, which are fundamental requirements for modern conservation and planning19,20.

Tulou (Earthen Structures) represent a distinctive and profoundly important manifestation of traditional Chinese vernacular architecture, embodying substantial historical, cultural, and artistic achievements. These rammed-earth structures face escalating deterioration risks due to temporal degradation and persistent environmental erosion. Traditional manual inspection and rudimentary measurement techniques fundamentally fail to meet contemporary high-precision conservation standards. In stark contrast, advanced 3D point cloud technology offers a transformative, non-contact, high-precision solution for conservation and scholarly research21,22,23. The rapid acquisition of detailed spatial information is critical for comprehensive deformation detection and structural pathology analysis, enabling precise monitoring of structural changes, timely identification of potential safety hazards, and provision of scientifically rigorous foundations for conservation interventions24.

Recent advances in laser point cloud-based wall deformation detection have significantly enhanced structural health assessment capabilities for heritage buildings. Emerging methodologies employ sophisticated algorithms for automated deformation analysis, including surface deviation mapping, geometric feature extraction, and multi-temporal comparative analysis25,26,27. These innovations enable millimeter-level accuracy in detecting subtle structural movements, inclinations, and surface irregularities that would be imperceptible through conventional inspection methods26,27,28,29. Studies have demonstrated that integrating machine learning algorithms with point cloud data facilitates predictive modeling of deterioration patterns, thereby supporting proactive conservation strategies30,31,32,33. Such achievements provide scientific monitoring data and innovative technical solutions for structural safety assessment and damage detection, establishing a robust framework for evidence-based heritage management34. To achieve maximum data precision and comprehensive documentation, this study employs an integrated approach that strategically combines laser scanning (Trimble X7) and digital photogrammetry (UAV oblique photography)35,36,37,38,39. This methodology relies on multi-source data fusion, a technique proven effective in complex applications such as heritage conservation and architectural analysis40. Oblique photographic images provide essential surface texture information, while point cloud data significantly enhances structural geometric information, yielding highly accurate and realistic 3D models41. The fusion of these datasets facilitates enhanced pathology identification through more comprehensive analysis of surface characteristics and underlying structures42,43. The primary objective of this research is to develop and validate a robust methodology for deformation detection and pathology analysis of Tulou using integrated 3D point cloud technology, ultimately establishing a scalable and applicable technical paradigm for the conservation of similar cultural architectural complexes. However, efficient management of monitoring data during the conservation process remains essential. This study does not address the implementation of Heritage Building Information Modeling (HBIM) projects for Fujian Tulou, an approach that has been successfully applied in other published research to buildings with extensive histories and temporal transformations44,45. Future integration of HBIM environments could further enhance data interoperability, facilitate longitudinal monitoring, and support collaborative conservation decision-making46,47,48,49 (Fig. 1).

Fujian Tulou are globally recognized as World Cultural Heritage for their unique designs that exemplify harmonious coexistence between human ingenuity and nature44,50. Among these structures, Jinjiang Tulou in Zhangpu County stands out as a nationally designated key cultural relic protection unit (Fig. 2).

This distinctive architectural structure is renowned for its multi-tiered umbrella-shaped pattern and concentric circular design, symbolizing the Chinese cosmological concept of round heaven and square earth51,52,53,54. Dating back to the Qing Dynasty, Jinjiang Tulou carries rich architectural and social information, rendering it an invaluable tangible resource for studying the evolutionary trajectory of regional Tulou construction techniques55. Although Jinjiang Tulou’s current conservation status remains stable, the structure is inherently susceptible to the cumulative effects of long-term natural erosion and subtle structural movements56,57. To ensure the building’s continued safety and development, the application of advanced surveying technologies—particularly 3D laser scanning and UAV oblique photogrammetry—is indispensable58,59. This approach transcends basic inspection, enabling comprehensive and accurate pathology detection. This study is dedicated to leveraging these advanced technologies to provide a solid technical foundation for formulating scientifically sound, evidence-based conservation schemes, thereby promoting the modernization of conservation techniques and ensuring the perpetual existence of this outstanding architectural treasure.

Methods

3D point cloud and multi-source data acquisition and fusion from UAV

This study employed an integrated multi-source data acquisition and fusion framework combining terrestrial laser scanning (TLS), unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) photogrammetry, and DSLR imaging to obtain comprehensive three-dimensional documentation of the Jinjiang Tulou. The workflow was designed to overcome the limitations of single-sensor approaches and to maximize geometric completeness, accuracy, and surface detail fidelity in complex architectural environments60 (Fig. 3).

Terrestrial laser scanning was conducted using the Trimble X7 system, which enables non-contact, high-resolution measurement of architectural surfaces through phase-shift or time-of-flight ranging61,62. Operating with a typical accuracy of ±1–2 mm at a 50 m range, TLS provides dense spatial sampling rates of up to one million points per second, producing detailed geometric data suitable for cultural heritage applications requiring millimeter-level precision. The scanner consists of a laser transmitter, receiver, and prism assembly mounted on a motorized rotational platform, enabling full 360° horizontal and vertical coverage63. Laser pulses emitted across a specific wavelength range are reflected from target surfaces and received by the detector, where the time-of-flight and angular information are used to compute point coordinates through triangulation64. Although TLS provides highly accurate data for ground-level and mid-height architectural elements, its vertical scanning angle and line-of-sight constraints lead to occlusions in upper-level or overhanging structures65.

To address these limitations, UAV-based photogrammetry was employed to capture high-resolution nadir and oblique imagery of elevated features, roof structures, and upper facades13. UAV acquisition significantly improves coverage efficiency, achieving up to 10 hectares per flight hour, and effectively fills the typical TLS blind zones occurring above approximately 15 m. The integration of aerial imagery enhances both geometric and texture quality, providing a more complete dataset for modeling the Tulou’s circular and multi-level architectural form66.

Following data acquisition, a feature-based point cloud fusion method was used to integrate the UAV-derived point cloud with the RealWorks® TLS point cloud. Geometric feature points—such as corners, edges, and surface inflection points—were extracted from both datasets. Table 1 Local feature descriptors were calculated to identify corresponding feature pairs between UAV and TLS point clouds, enabling robust cross-source matching. Based on these matched feature pairs, a transformation matrix incorporating rotation, translation, and scale parameters was computed to align the two datasets66 (Fig. 4).

The UAV point cloud was subsequently transformed into the TLS coordinate system to achieve initial alignment, after which fine registration was performed to optimize the fusion accuracy67. This multi-source integration significantly improves geometric completeness and produces a unified high-fidelity 3D model suitable for deformation detection68, structural disease analysis, and long-term conservation documentation. The underlying principles of the feature-based fusion algorithm, along with the mathematical formulations used to compute the transformation matrix and registration accuracy, are presented in Eqs. (1)–(8).Calculate the centroid using the transformation matrix. For the point cloud model of the unmanned aerial vehicle, assume that the point cloud set is:

\({\rm{Pd}}=\left\{{\rm{pd}}1,{\rm{pd}}2,\cdots ,{\rm{pdn}}\right\}\), its centroid \({{\rm{C}}}_{{\rm{d}}}\) calculation formula is:

Among which \({{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{di}}}=\left({{\rm{x}}}_{{\rm{di}}},{{\rm{y}}}_{{\rm{di}}},{{\rm{z}}}_{{\rm{di}}}\right)\) is the i point in the point cloud of the unmanned aerial vehicle.

For the RealWorks® point cloud model, let the point cloud set be \({{\rm{P}}}_{{\rm{r}}}=\left\{{{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{r}}1},{{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{r}}2},\cdots ,{{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{rm}}}\right\}\). Its centroid \({{\rm{C}}}_{{\rm{r}}}\) can be obtained by this formula:

In which \({{\rm{p}}}_{\mathrm{rj}}=({{\rm{x}}}_{\mathrm{rj}},{{\rm{y}}}_{\mathrm{rj}},{{\rm{z}}}_{\mathrm{rj}})\) is RealWorks® the j point in the point cloud, construct and calculate the covariance matrix through the following formula:

\({{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{di}}}-{{\rm{C}}}_{{\rm{d}}})\) and \(\left({{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{ri}}}-{{\rm{C}}}_{{\rm{r}}}\right)\) is the vector difference, after the transpose of \({({{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{ri}}}-{{\rm{C}}}_{{\rm{r}}})}^{{\rm{T}}}\) is \(\left({{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{ri}}}-{{\rm{C}}}_{{\rm{r}}}\right)\), perform singular value decomposition on the covariance matrix \({\rm{H}}\).

\({\rm{U}}\) and \({\rm{V}}\) are orthogonal matrices, \(\Sigma\) is a diagonal matrix, the formula for calculating the rotation matrix is:

Then, perform vector translation.

Then, transform the matrix by the following formula:

Through this transformation matrix, the UAV point cloud model can be transformed to RealWorks® fuse the point cloud models under the coordinate system of the target point cloud.

Finally, conduct an evaluation of the fusion accuracy - root mean square error. RMSE(root mean square error); Suppose N is three points in the fused point cloud model corresponding to the actual reference point cloud model, the coordinates of the points after fusion are \(\left({{\rm{x}}}_{{\rm{i}}},{{\rm{y}}}_{{\rm{i}}},{{\rm{z}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\right)\), and the coordinates of the actual reference points are \(\left({{\rm{x}}}_{{\rm{i}}},{{\rm{y}}}_{{\rm{i}}},{{\rm{z}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\right)\).

RMSE smaller the value is, the more it indicates that the accuracy of the fused point cloud model is higher (Fig. 5).

Following the feature-based fusion of the TLS and UAV point clouds, an expanded multi-source data acquisition strategy was applied to further enhance the completeness and richness of the dataset69. The continuous advancement of multi-source data fusion technologies has greatly accelerated progress in architectural mapping, providing essential spatial and visual information for high-precision 3D modeling and structural analysis. In this study, the accurate three-dimensional coordinate measurements obtained from the Trimble X7, the aerial imagery captured by UAV platforms, and the fine-grained ground-level texture data recorded by handheld DSLR cameras were jointly integrated to establish a comprehensive, high-resolution geospatial and architectural information database (Fig. 6).

This multi-dimensional dataset not only strengthens the robustness of the fused 3D model but also provides a solid foundation for subsequent deformation detection, structural disease analysis, and long-term digital conservation.

Laser point cloud dataset

While 3D laser scanning is a substantial tool in digital heritage conservation and architectural information extraction, this study implements a high-fidelity data acquisition strategy specifically tailored to the material characteristics of Jinjiang Tulou using the Trimble X7 system. The core innovation of this application lies in leveraging the system’s ultra-high sensitivity laser technology to address the challenges of varying surface reflectivity inherent in rammed-earth structures. Unlike conventional scanning methods, this technology effectively captures complex surface gradients from dark to light, ensuring complete data coverage even on low-reflectivity earth walls70. The system rapidly acquires 360-degree panoramic imagery and high-density point clouds, providing a comprehensive, occlusion-free geometric dataset essential for subsequent industrial-grade deviation analysis. Furthermore, the high interoperability of the output data supports direct export to multiple standard formats, enabling a seamless integrated workflow from on-site acquisition to advanced processing in software such as RealWorks, thereby ensuring the precise mapping of the physical structure into the digital domain71.

3D point cloud data decimation processing

The laser scanning of Jinjiang Tulou involved 185 stations, yielding a dataset exceeding 2 GB points. However, the raw data from individual stations operated within independent coordinate systems and contained significant noise and redundancy. These issues resulted in inefficient modeling and compromised accuracy. To address this, the point cloud files were fused using Trimble RealWorks®. This integration unified the surveyed data, ensuring greater completeness and reduced error compared to isolated scans. To further enhance processing efficiency, data decimation was applied72. The mainstream decimation methods available in Trimble RealWorks® include random sampling, spatial sampling, and intensity-based weighted sampling (Fig. 7).

Random sampling

The core principle of the random sampling method lies in determining whether each point in the point cloud dataset is retained through a stochastic process governed by random numbers. Below are the detailed mathematical formulation and theoretical explanation:

Step 1: Set the sampling ratio, let the sampling ratio be denoted as \({\rm{p}}\), where \(0 < {\rm{p}}\leqslant 1\). Example: if \({\rm{p}}=0.5\), this implies retaining 50% of the points from the original point cloud data.

Step 2: Generate random numbers: for every point \({\rm{Pi}}({\rm{i}}=1,\cdots ,{\rm{n}},{\rm{n}},{\rm{n}}\) denote the total number of points in the original point cloud dataset within the original point cloud data, generate a uniformly distributed random number within the interval \(\left[0,1\right]\). Mathematically, the random number \({{\rm{r}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) satisfies \({{\rm{r}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\sim {\rm{U}}\left(0,1\right)\), where \({\rm{U}}\left(0,1\right)\) denotes a uniform distribution over the interval.

Spatial sampling decimation

The main principle of spatial sampling decimation is to determine whether to retain points based on the spatial distance between them. First, a distance threshold \({\rm{d}}\) is set. For each point in the point cloud, the distance to nearby points is calculated. If the distance from a point to its nearest neighbor is less than \({\rm{d}}\), that point may be deleted, retaining only those points that are relatively isolated, thus achieving the purpose of decimation. The following formulas (9)–(13) are the decimation calculation formulas.

Step 1: Perform the Euclidean distance calculation:

For two points \({{\rm{P}}}_{{\rm{i}}}=\left({{\rm{x}}}_{{\rm{i}}},{{\rm{y}}}_{{\rm{i}}},{{\rm{z}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\right){\rm{and}}\) \({{\rm{P}}}_{{\rm{j}}}=({{\rm{x}}}_{{\rm{j}}},{{\rm{y}}}_{{\rm{j}}},{{\rm{z}}}_{{\rm{j}}})\) in three-dimensional space, the formula for calculating the Euclidean distance \({{\rm{d}}}_{{\rm{ij}}}\) between them is expressed as:

Step 2: Down-sampling criterion Let \({\rm{d}}\) denote the predefined distance threshold. For a given point \({\rm{d}}\), if its Euclidean distance to neighboring points satisfies \({{\rm{d}}}_{{\rm{ij}}}\)> \({\rm{d}}\), the point \({{\rm{P}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) is retained; otherwise, it is flagged for potential removal.

For a point \({\rm{P}}=\left({\rm{x}},{\rm{y}},{\rm{z}}\right)\), the formula for calculating its index \(\left({\rm{i}},{\rm{j}},{\rm{k}}\right)\) in a voxel grid is expressed as:

where \({\rm{s}}\) denotes the edge length of the voxel, and \(\left\lfloor \cdot \right\rfloor\) represents the floor function.

Step 3: Voxel center calculation; for a voxel with index\(\left({\rm{i}},{\rm{j}},{\rm{k}}\right)\), the coordinates of its geometric center \(\left({{\rm{x}}}_{{\rm{c}}},{{\rm{y}}}_{{\rm{c}}},{{\rm{z}}}_{{\rm{c}}}\right)\) are computed as:

Selection of representative points within voxels: given a point \(\left\{{{\rm{P}}}_{1},{{\rm{P}}}_{2},\cdots ,{{\rm{P}}}_{{\rm{n}}}\right\}\) set within a voxel, for each point \({{\rm{P}}}_{{\rm{m}}}=\left({{\rm{x}}}_{{\rm{m}}},{{\rm{y}}}_{{\rm{m}}},{{\rm{z}}}_{{\rm{m}}}\right)\), compute its distance \({{\rm{d}}}_{{\rm{m}}}\) to the voxel center \(\left({{\rm{x}}}_{{\rm{c}}},{{\rm{y}}}_{{\rm{c}}},{{\rm{z}}}_{{\rm{c}}}\right)\):

The point with the minimum distance \({{\rm{d}}}_{{\rm{m}}}\) is selected as the representative point within the voxel.

Intensity-based weighted sampling for down-sampling

The principle of this down-sampling method lies in assigning each point an intensity-dependent weight \({\rm{w}}\left({{\rm{I}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\right)\), where points with higher weights have a greater probability of being selected. The computational formula is expressed as follows:

The probability of point \({{\rm{P}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) being selected is quantified as \({{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\):

Sampling is then performed according to this probability distribution, and a stochastic sampling algorithm can be employed to determine the final retained point set (Fig. 7).

To visually compare the effectiveness of the three decimation strategies, a portion of the point Table 2 cloud corresponding to a single column located on the second-floor gable corridor of the Jinjiang Tulou was extracted (Fig. 8).

The original, unthinned point cloud is shown in Fig. 8a, while the results of random sampling, spatial sampling decimation, and intensity-based sampling decimation are presented in Fig. 8b–d, respectively. A comparative examination reveals clear differences in the preservation of surface features. The intensity-based approach fails to retain the concave–convex geometric characteristics of the column surface, leading to substantial loss of structural detail. In contrast, both spatial sampling and random sampling effectively maintain the primary morphological features of the column, with spatial sampling exhibiting particularly robust preservation of surface continuity and geometric clarity.

Results

Pathological damages and deformation monitoring of the Tulou exterior walls

Fujian Tulou, a traditional Hakka residential architecture, is characterized by massive rammed-earth load-bearing walls. These structures are highly vulnerable to long-term environmental stressors, including rainfall, moisture infiltration, and lateral wind loading. Cumulative exposure frequently results in cracks, surface spalling, weathering, siding deformation, and localized material loss on rammed-earth walls, while timber components commonly exhibit cracking, distortion, corrosion, decay, and insect damage72 (Fig. 9).

While non-contact inspection technologies are increasingly adopted in heritage conservation, traditional practices remain fragmented, often lacking the systemic integration required for precise diagnosis73. To address this limitation, recent advancements in digital documentation emphasize multi-source data fusion—specifically combining Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS) with UAV photogrammetry—to compensate for the field-of-view limitations of single data sources74. This approach offers comprehensive, occlusion-free modeling and texture mapping solutions for complex vernacular architecture. Aligning with this trend, this study establishes an information-integrated monitoring workflow for the Jinjiang Tulou. High-precision point clouds acquired by the Trimble X7 were deeply integrated with multi-view aerial and terrestrial imagery within the Trimble RealWorks® environment, thereby establishing a robust data foundation for subsequent detailed structural diagnosis75.

In the Jinjiang Tulou, images captured by UAV and DSLR revealed multiple surface cracks of varying depths and distinct areas of moisture seepage across the exterior walls. To quantify these conditions, a 3D point cloud model was generated76. Following standardized protocols for point cloud processing—denoising, trimming redundant background information, and segmentation—a clean, isolated point cloud of the exterior wall was obtained77,78 (Fig. 10).

Wall Verticality and Geometric Deformation The assessment of wall verticality utilized the Trimble RealWorks® platform, leveraging an automated inspection workflow (Fig. 11).

This approach addresses the growing demand for objective, algorithmic safety monitoring in historic structures, reducing the subjectivity inherent in manual surveys79. Points on each slice were fitted to derive an idealized reference surface, allowing for the calculation of deviations between the actual geometry and the theoretical plane (Fig. 12).

Figures 13 and 14 display the verticality detection results for the bottom and top slices, respectively. White squares denote sampled detection points, while color-coded zones represent deviations from the theoretical reference profile (black line). The green region marks the acceptable tolerance zone. Consistent with deformation studies on cylindrical heritage structures, the visualization clearly highlights sections exceeding allowable limits80,81 (Figs. 13 and 14).

To intuitively evaluate the overall vertical deformation trends, the bottom and top slice results were superimposed (Fig. 15).

The divergence between the projected curves reflects variations in wall inclination. This visualization method supports recent findings that comparative slice analysis provides robust quantitative evidence for structural tilting in earthen heritage (Table 3).

These low compliance rates indicate that the exterior walls of the Jinjiang Tulou deviate significantly from their visually perceived circular form. Validated through high-precision point cloud acquisition and automated computational analysis, the proposed workflow demonstrates the effectiveness of modern geospatial technologies and point cloud data in large-scale deformation monitoring, thereby contributing to the digitalization and intelligent conservation of rammed-earth architectural heritage (Fig. 16).

Flatness detection of Tulou floors

The floor flatness of the Jinjiang Tulou was evaluated using the floor-flatness inspection module in Trimble RealWorks®, which conducts analysis through automated processing of point cloud data. The software employs proprietary algorithms to extract height information from the scanned surface and perform comparative assessment across the entire floor plane.

Field investigation indicates that the second-floor surface of the Jinjiang Tulou exhibits several defects, including cracks, floor tile bulging, and localized unevenness (Fig. 17).

In this study, the flatness detection tool in RealWorks® was applied to conduct a comprehensive assessment of the second-floor surface. The resulting measurements enable an initial diagnostic interpretation of the floor’s condition while establishing a scientific test dataset to support future monitoring and comparative analysis. The flatness evaluation is based on height deviation maps generated directly from the laser-scanned point cloud (Fig. 18).

Within the “Floor Inspection” module of RealWorks®, areas exceeding the mean elevation are displayed in red, whereas areas below the mean are displayed in blue, indicating zones of relative uplift and depression. Figure 19 presents the horizontal section analysis for the floor surface, where the red curve represents the ideal reference plane and the green curve indicates the measured surface profile. Table 4 The deviation between the two curves provides an intuitive visualization of floor flatness, allowing for clear identification of uneven areas and the severity of deflection across the floor slab (Fig. 19).

Safety assessment of timber structures in Tulou

To address the limitations of traditional manual inspection regarding efficiency, accuracy, and spatial comprehensiveness, this study proposes a structural safety assessment framework based on 3D laser scanning and Trimble RealWorks®. By replacing discrete single-point measurements with non-contact, high-density point clouds, this approach effectively eliminates human error and provides a high-precision, fully digital diagnostic solution for heritage buildings (Fig. 20).

In this study, column point cloud data were first segmented within Trimble RealWorks® to isolate the geometry of the structural elements (Fig. 21).

Horizontal slices were extracted from the top and bottom sections of each column, after which the “Best-Fit” tool was applied to reconstruct the idealized cylindrical geometry of the slices (Fig. 22).

To ensure accuracy, deviations between the fitted cylinder and the column’s actual base plane were minimized, accounting for surface irregularities and local flatness variations. Following the fitting process, the software generated the center coordinates and diameters of both the top and bottom fitted cylinders, enabling direct comparison of the two reconstructed geometries82.

A total of six columns were selected as test specimens. For each column, the center coordinates of the upper and lower slices were recorded, and the horizontal offset distance between these two points was calculated (Fig. 23).

Using the measured vertical height of each column, the inclination angle was obtained based on basic trigonometric relationships. Additionally, orthographic projections of the reconstructed cylinders were generated, enabling direct visualization of the relative displacement between top and bottom center points on the same horizontal plane. Deviations in projection position were used to determine both the direction and magnitude of column inclination.

Further assessment of column verticality was conducted by measuring discrepancies between the original point cloud and the reconstructed reference cylinders. This comparison also enabled the identification of potential deformation patterns, including bending or asymmetric displacement, based on deviation distributions along the column height.

According to the Technical Standard for Maintenance and Strengthening of Ancient Timber Structures (GB/T 50165-2020), the allowable inclination rate iii of cylindrical structural elements between upper and lower floors in multi-story ancient buildings must satisfy:

i < H300i < \frac{H}{300}i < 300H

where HHH represents the story height. As shown in Fig. 23, each of the six sampled columns in this study has a height of 1750 mm. The measured horizontal offsets between the top and bottom centers range from 1 mm to 5 mm, corresponding to inclination rates (tanθ) between 0.0011 and 0.0022. All values fall within the permissible threshold stipulated in GB/T 50165-2020, indicating that the verticality of the Jinjiang Tulou columns meets the required safety and stability standards (Fig. 24).

Compared with traditional inspection methods, this integrated approach provides substantially higher measurement precision, operational efficiency, and diagnostic reliability. It offers a robust technical framework for the structural safety assessment of columnar components in Tulou and other earthen architectural heritage structures, contributing to more scientific and data-driven conservation practices.

Discussion

This study advances the methodology of structural health assessment by applying high-precision industrial metrology to the conservation of irregular rammed-earth heritage. We established a workflow based on reverse engineering that derives geometric reference surfaces from point cloud data and incorporates optimized point cloud sampling algorithms. This approach resolves the computational conflict between processing massive datasets and maintaining the sensitivity required to detect minute deformations. Consequently, it enables the precise calculation of wall roundness, verticality, surface flatness, and column inclination, transforming the assessment mode from subjective manual inspection to data-driven, industrial-grade quantitative diagnosis.

However, relying solely on geometric quantification is insufficient to fully explain the complex structural status of these buildings. This study indicates that distinguishing between historical settlement and active failure mechanisms still requires the professional judgment of structural engineers and conservation experts. Therefore, future research will focus on establishing a “hybrid diagnosis” mechanism. This involves cross-validating the deviation data provided by industrial metrology with qualitative expert assessments to calibrate damage classification standards, thereby ensuring that diagnostic results possess definitive structural engineering significance.

Looking ahead, the high-precision datasets obtained in this study will demonstrate practical utility across multiple dimensions. First, they provide static benchmark data for establishing long-term Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) mechanisms, facilitating the construction of a 4D monitoring system that incorporates the temporal dimension to record the slow, non-linear deformation processes of rammed-earth buildings. Second, by embedding quantitative deviation data into parametric objects, this approach resolves the technical challenges of integrating irregular components with Heritage Building Information Modeling (HBIM). Furthermore, these real-world datasets will serve directly as training samples for Artificial Intelligence (AI) models, supporting the development of automated pathology segmentation and classification algorithms. Ultimately, this digital technical solution validates the effectiveness of industrial-grade inspection protocols in the conservation of Fujian Tulou, providing a scientific and reproducible technical reference for the preservation of rammed-earth heritage globally.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to the proprietary nature of certain computational models and experimental data, access may be granted for academic and research purposes under appropriate agreements.

Code availability

The software and UAV point cloud processing codes used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to the ongoing nature of the research and potential proprietary considerations, access to specific code components may be granted under a collaborative research agreement.

References

Omar, H., Mahdjoubi, L. & Kheder, G. Towards an automated photogrammetry-based approach for monitoring and controlling construction site activities. Comput. Ind. 98, 172–182 (2018).

Larsen, J. K., Shen, G. Q., Lindhard, S. M. & Brunoe, T. D. Factors affecting schedule delay, cost overrun, and quality level in public construction projects. J. Manag. Eng. 32, 04015032 (2016).

Zhang, C., Zou, Y. & Dimyadi, J. Integrating UAV and BIM for automated visual building inspection: a systematic review and conceptual framework. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1101, 062030 (2022).

Tan, Y. et al. Intelligent inspection of building exterior walls using UAV and mixed reality based on man-machine-environment system engineering. Autom. Constr. 177, 106344 (2025).

Sestras, P. et al. Land surveying with UAV photogrammetry and LiDAR for optimal building planning. Autom. Constr. 173, 106092 (2025).

Costa, R. P., Fernandes, L. L. D. A., Muta, L. F., Isatto, E. L. & Costa, D. B. Modelagem 3D De Edificação Gerada Por Fotogrametria Com Uso De Veículos Aéreos Não Tripulados (VANT). Ambient. Constr. 24, e131377 (2024).

Yu, R., Li, P., Shan, J., Zhang, Y. & Dong, Y. Multi-feature driven rapid inspection of earthquake-induced damage on building facades using UAV-derived point cloud. Measurement 232, 114679 (2024).

Guedes, J. V. F., Meira, G. D. S., Bias, E. D. S., Pitanga, B. & Lisboa, V. Performance of sensors embedded in UAVs for the analysis and identification of pathologies in building Façades. Buildings 15, 875 (2025).

Seo, D.-M., Woo, H.-J. & Seo, H. Quantitative estimation of asbestos-containing slate roof areas using UAV imagery and GIS-based correction. J. Build. Eng. 113, 113853 (2025).

Fang, Z. & Savkin, A. V. Strategies for optimized UAV surveillance in various tasks and scenarios: a review. Drones 8, 193 (2024).

García-Nieto, M. C., Huesca-Tortosa, J. A., Martínez-Segura, M. A., Espín De Gea, A. & Navarro, M. Structural deformation monitoring using UAV photogrammetry to assess slender historic buildings. J. Build. Eng. 100, 111766 (2025).

Rezk, M. Y., Mohamed, N. H. & Nagy, N. M. Structural health monitoring with UAV. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2616, 012051 (2023).

Keong, K. F. et al. The adoption of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) technology in the construction industry: construction stakeholders’ perception. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1238, 012024 (2023).

Ahmad Kamal, A. A., Ahmad, M. A., Ahmad, M. J. & Srivanit, M. 3D Model of Tunku Tun Aminah Library using unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. 14, 408–415 (2023).

Fiorillo, F., Perfetti, L. & Cardani, G. Automated mapping of the roof damage in historic buildings in seismic areas with UAV photogrammetry. Procedia Struct. Integr. 44, 1672–1679 (2023).

Zhang, C., Zou, Y., Wang, F. & Dimyadi, J. Automated UAV image-to-BIM registration for planar and curved building façades using structure-from-motion and 3D surface unwrapping. Autom. Constr. 174, 106148 (2025).

Tan, Y., Li, S., Liu, H., Chen, P. & Zhou, Z. Automatic inspection data collection of building surface based on BIM and UAV. Autom. Constr. 131, 103881 (2021).

Duan, Z. et al. Automating exterior BIM for existing buildings using GIS data and UAV-based 3D modeling. Autom. Constr. 178, 106422 (2025).

Limongiello, M. et al. Parametric GIS and HBIM for archaeological site management and historic reconstruction through 3D survey integration. Remote Sens. 17, 984 (2025).

Lin, X. X. B. A study on the architectural features of Lin Fujian Coastal Tulou - Jinjiang Tower. Fujian Archit. Constr. 10, 1–10 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. 3D model-based terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) observation network planning for large-scale building facades. Autom. Constr. 144, 104594 (2022).

Willkens, D. S., Liu, J. & Alathamneh, S. A case study of integrating terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) and building information modeling (BIM) in Heritage Bridge Documentation: The Edmund Pettus Bridge. Buildings 14, 1940 (2024).

Munasinghe, I., Perera, A. & Deo, R. C. A comprehensive review of UAV-UGV collaboration: advancements and challenges. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 13, 81 (2024).

Cui, S. Research on the protection of traditional villages from the perspective of living heritage: taking Hekeng Village in Fujian Province as an example. Archit. Cult. 1, 63 (2025).

Damięcka-Suchocka, M., Katzer, J. & Suchocki, C. Application of TLS technology for documentation of brickwork heritage buildings and structures. Coatings 12, 1963 (2022).

Batar, O. S., Tercan, E. & Emsen, E. Ayvalıkemer (Sillyon) Historical Masonry Arch Bridge: a multidisciplinary approach for structural assessment using point cloud data obtained by terrestrial laser scanning (TLS). J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 11, 1239–1252 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Comparative analysis of point clouds acquired from a TLS survey and a 3d virtual tour for HBIM development. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. XLVIII-M-2–2023, 959–968 (2023).

Ma, J., Liu, D., Yan, W., Wang, J. & Liu, G. Detection of cracks in ancient wooden buildings based on RPA oblique photography measurement and TLS. J. Field Robot. 42, 742–759 (2025).

Liu, J., Willkens, D. & Gentry, R. Developing a practice-based guide to terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) for heritage documentation. Heritage 8, 313 (2025).

Oytun, M. & Atasoy, G. Effect of terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) parameters on the accuracy of crack measurement in building materials. Autom. Constr. 144, 104590 (2022).

Algadhi, A., Psimoulis, P., Grizi, A. & Neves, L. Experimental assessment of the performance of terrestrial laser scanners in monitoring the geometric deformations in retaining walls. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 15, 1885–1900 (2025).

Klapa, P., Mitka, B. & Zygmunt, M. Integration of TLS and UAV data for the generation of a three-dimensional basemap. Adv. Geodesy Geoinf. https://doi.org/10.24425/agg.2022.141301 (2022).

Ahmed, F., Mohanta, J. C., Keshari, A. & Yadav, P. S. Recent advances in unmanned aerial vehicles: a review. Arab J. Sci. Eng. 47, 7963–7984 (2022).

Gao, X., Zhou, D. & Cui, W. Research on the application of ancient architecture based on 3D laser scanning and BIM. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. X 11, 2246.0172 (2019).

Zhao, Y., Huang, B., Zhu, Z., Guo, J. & Jiang, J. Building information extraction and earthquake damage prediction in an old urban area based on UAV oblique photogrammetry. Nat. Hazards 120, 11665–11692 (2024).

Zakiyon, A. M. A. A., Idris, A. N., Hezri Razali, M., Ghani, M. N. A. & Syafuan, W. M. Evaluating the accuracy of UAV and TLS for 3D indoor modelling in large-scale building environments. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1240, 012003 (2023).

Shan, J., Zhu, H. & Yu, R. Feasibility of accurate point cloud model reconstruction for earthquake-damaged structures using UAV-based photogrammetry. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2023, 1–19 (2023).

Kong, X., Pettijohn, T. F. & Torikyan, H. From photogrammetry to virtual reality: a framework for assessing visual fidelity in structural inspections. Sensors 25, 4296 (2025).

Ma, L. et al. Hollowing defect detection and risk assessment of facade tile shedding in high-rise residential buildings using the UAV–mounted infrared thermography method. J. Build. Eng. 113, 113840 (2025).

Wang, S., Zheng, G. & Wang, G. Building fine modeling of Hakka earth buildings (Tulou) based on multi-source point cloud data fusion. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 20, 43–48 (2020).

Wei, S. et al. Indoor and outdoor multi-source 3D data fusion method for ancient buildings. J. meas. eng. 10, 117–139 (2022).

Yin, H. & Yang, J. Application of multi-source heterogeneous point cloud fusion technology in ancient building information preservation. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 3, 97–102 (2020).

Li, H., Jin, T. & Zhang, Y. Research on structural inspection methods based on 3D laser scanning technology. Bull. Surv. Map. 43, 10–24 (2024).

Liu, L., Zhou, K., Li, H. & Liu, C. Application of 3D laser scanner technology in historical building surveying. Urban Geotech. Investig. Surv. 33, 86–90 (2018).

Wang, J., Yi, T., Liang, X. & Ueda, T. Application of 3D laser scanning technology using laser radar system to error analysis in the curtain wall construction. Remote Sens. 15, 64 (2022).

Nowak, R., Kania, T., Rutkowski, R. & Ekiert, E. Research and TLS (LiDAR) construction diagnostics of clay brick masonry arched stairs. Materials 15, 552 (2022).

Wu, J., Shi, Y., Wang, H., Wen, Y. & Du, Y. Surface defect detection of Nanjing City Wall based on UAV oblique photogrammetry and TLS. Remote Sens. 15, 2089 (2023).

Klapa, P. & Gawronek, P. Synergy of geospatial data from TLS and UAV for heritage building information modeling (HBIM). Remote Sens. 15, 128 (2022).

Markiewicz, J., Kot, P., Markiewicz, Ł & Muradov, M. The evaluation of hand-crafted and learned-based features in terrestrial laser scanning-structure-from-motion (TLS-SfM) indoor point cloud registration: the case study of cultural heritage objects and public interiors. Herit. Sci. 11, 254 (2023).

Hua, L., Huang, H. & Chen, C. Three-dimensional modeling of Hakka earth buildings (Tulou) based on laser scanning point cloud data. Sci. Surv. Mapp. 40, 115–119 (2015).

Stałowska, P. & Suchocki, C. TLS data for cracks detection in building walls. Data Brief. 42, 108247 (2022).

Balestrieri, M., Valmori, I. & Montuori, M. UAS and TLS 3D data fusion for built cultural heritage assessment and the application for St. Catherine Monastery in Ferrara. Italy Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. XLVIII-M-4–2024, 9–16 (2024).

Nowak, R., Orłowicz, R. & Rutkowski, R. Use of TLS (LiDAR) for building diagnostics with the example of a historic building in Karlino. Buildings 10, 24 (2020).

Li, J., Wang, L. & Huang, J. Wall length-based deformation monitoring method of brick-concrete buildings in mining area using terrestrial laser scanning. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 13, 1077–1090 (2023).

Masciotta, M.-G., Roque, J. C. A., Ramos, L. F. & Lourenço, P. B. A multidisciplinary approach to assess the health state of heritage structures: the case study of the Church of Monastery of Jerónimos in Lisbon. Constr. Build. Mater. 116, 169–187 (2016).

Yi, C., Lu, D., Xie, Q., Xu, J. & Wang, J. Tunnel deformation inspection via global spatial axis extraction from 3D raw point cloud. Sensors 20, 6815 (2020).

Borkowski, A. S. & Kubrat, A. Integration of laser scanning. Digit. Photogramm. Bim Technol. A Rev. Case Stud. Eng. 5, 2395–2409 (2024).

Jang, A., Ju, Y. K. & Park, M. J. Structural stability evaluation of existing buildings by reverse engineering with 3D laser scanner. Remote Sens. 14, 2325 (2022).

Jeftha, K. J. & Shoko, M. Mobile phone based laser scanning as a low-cost alternative for multidisciplinary data collection. S. Afr. J. Sci 120, 1 (2024).

Selbesoglu, M. O., Bakirman, T. & Gokbayrak, O. Deformation measurement using terrestrial laser scanner for cultural heritage. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. XLII-2/W1, 89–93 (2016).

Pu, X., Gan, S., Yuan, X. & Li, R. Feature analysis of scanning point cloud of structure and research on hole repair technology considering space-ground multi-source 3D data acquisition. Sensors 22, 9627 (2022).

Yuanyuan, F. E. N. G., Hao, L. I., Chaokui, L. I. & Jun, C. H. E. N. 3D modelling method and application to a digital campus by fusing point cloud data and image data. Heliyon 10, e36529 (2024).

Wang, Y., Huang, X. & Gao, M. 3D model of building based on multi-source data fusion. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. XLVIII-3/W2-2022, 73–78 (2022).

Ji, H. & Luo, X. 3D scene reconstruction of landslide topography based on data fusion between laser point cloud and UAV image. Environ. Earth Sci. 78, 534 (2019).

Sadeghineko, F., Lawani, K. & Tong, M. Practicalities of incorporating 3D laser scanning with BIM in live construction projects: a case study. Buildings 14, 1651 (2024).

Yusof, H., Anjang Ahmad, M. & Abdullah, A. M. T. Historical building inspection using the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV). Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. 11, 17–20 (2020).

Falorca, J. F., Miraldes, J. P. N. D. & Lanzinha, J. C. G. New trends in visual inspection of buildings and structures: study for the use of drones. Open Eng. 11, 734–743 (2021).

Wang, Y., Zhang, T. & Wang, J. Building 3D realistic modeling based on air-ground multi-source data fusion. E3S Web Conf. 213, 03025 (2020).

Yang, S., Hou, M. & Li, S. Three-dimensional point cloud semantic segmentation for cultural heritage: a comprehensive review. Remote Sens. 15, 548 (2023).

Mou, C. & Wang, Z. Application of multi-source point cloud fusion technology in urban renewal data acquisition. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 11, 151–155 (2024).

Kim, H., Kim, J.-Y. & Shin, Y. Reverse engineering of building layout plan through checking the setting out of a building on a site using 3D laser scanning technology for sustainable building construction: a case study. Sustainability 16, 3278 (2024).

Morero, L. et al. The use of a heritage building information model as an effective tool for planning restoration and diagnostic activities: the example of the Troia Cathedral rose window. Acta IMEKO 12, 1–8 (2023).

Zhang, J., Zhuo, L. & Fei, Y. Construction of HBIM information management system for modern regional historical buildings in Southern Fujian: a case study of Xiamen Haicang Juren House. J. Civ. Archit. Environ. Eng. 15, 47–52 (2023).

Sun, J., Wang, P., Li, R., Zhou, M. & Wu, Y. Fast tree skeleton extraction using voxel thinning based on tree point cloud. Remote Sens. 14, 2558 (2022).

Ramamurthy, M. B., Doonan, J., Zhou, D. J. & Liu, D. Y. Skeletonization of 3D plant point cloud using a voxel based thinning algorithm. https://api.semanticscholar.org/https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:66271 (2015).

Wu, G. Building Structure Health Monitoring and Evaluation Method based on Three-Dimensional Laser Scanning Technology. Master’s thesis, Anhui Jianzhu Univ. (2024).

Masciotta, M.-G., Ramos, L. F. & Lourenço, P. B. The importance of structural monitoring as a diagnosis and control tool in the restoration process of heritage structures: a case study in Portugal. J. Cult. Herit. 27, 36–47 (2017).

Wen, Y., Feng, S. & Qiu, Z. Application of handheld laser scanner in obtaining 3D model of underground garage. Electron. Technol. Softw. Eng. 22, 156–159 (2022).

Lee, M., Lee, S., Kwon, S. & Chin, S. A study on scan data matching for reverse engineering of pipes in plant construction. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 21, 2027–2036 (2017).

Sivasuriyan, A. et al. Practical implementation of structural health monitoring in multi-story buildings. Buildings 11, 263 (2021).

Zhan, J., Zhang, T., Huang, J. & Li, M. Maintenance approaches using 3D scanning point cloud visualization, and Bim+ data management: a case study of Dahei Mountain buildings. Buildings 14, 2649 (2024).

Wang, J., Sun, W., Xiao, L., Zhou, Y. & Liu, Y. Tilt observation method of dragon post for 3D laser scanning. Sci. Surv. Mapp. 21, 45 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The project is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Project (52578022), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (2025J01163), and Huaqiao University’s Academic Project supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2025HQYJ07).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiahao Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - First Draft, Writing - Original Draft, Review and Editing. Shengjin Zou: Data Curation, Data Processing and Analysis, Validation, Writing and Editing. Wei xin Zhang: Data Acquisition. Hua Tian: Equipment.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Zou, S., Zhang, W. et al. Deformation and disease detection of Tulou based on multi-source 3D point cloud fusion. npj Herit. Sci. 14, 66 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02333-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02333-w