Abstract

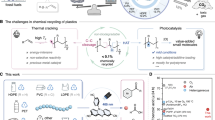

Plastics, omnipresent in 20th-century museum collections, pose major conservation challenges due to their often rapid, irreversible degradation. At the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Paris), nearly 12,000 plastic objects raise urgent concerns. This study establishes a degradation atlas based on polymer identification and condition assessments of 142 representative objects, using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy supported by micro-analyses. Results highlight the predominance of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and polyurethane (PU), often combined with polyethylene (PE) and polystyrene (PS) in composite objects. PU is the most vulnerable, particularly in fashion objects, where degradation leads to sticky surfaces and delamination. PVC primarily exhibits yellowing and plasticizer migration, while PE and PS are generally more stable. Composite objects pose additional challenges due to incompatibilities. Degradation is most severe in objects from the 1960s-1990s. By linking materials to alterations, the atlas and database provide conservators a practical reference tool to improve preventive strategies, staff training, and long-term monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Once hailed as both a technological marvel and an aesthetic revolution, plastics have profoundly reshaped modern life since their introduction in the early 20th century. Their lightness, malleability, and low production cost made them indispensable across industries—from packaging and construction to art, design, and architecture—thanks to their ability to imitate a wide range of materials and textures1. Their ubiquity extends into museum collections, whether in institutions dedicated to plastic materials such as contemporary design or industrial heritage, or within broader cultural and artistic collections such as fine arts museums2,3,4,5.

While plastics symbolise modernity and mass production, they also present a paradox: durable in the environment yet instable in museum collections. Many plastic artefacts in heritage collections risk rapid, sometimes irreversible degradation5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, threatening the long-term preservation of objects defining twentieth and twenty-first century visual and material culture. Keene was one of the earliest authors to propose a systematic approach to assessing the condition of plastic materials in museum collections, at a time when these materials were still relatively new and poorly understood14. Then, the European Preservation Of Plastic Artefacts (POPART) project highlighted the fragility of plastic objects and laid the groundwork for a long-term strategy for their preventive conservation8. Based on evaluations of several collections (in the U.K. at the Victoria and Albert Museum, in the Netherlands at the Stedelijk Museum, and in France at the Musée d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporain of Nice, the Musée d’Art Moderne of Saint-Etienne, and the Musée Galliera), the project aimed to establish reproducible protocols to develop generalisable methods, tools, and recommendations. It also demonstrated that much remains to be done: plastics are highly diverse, additives complicate analyses, and their sensitivity to environmental conditions or restoration treatments varies greatly depending on the material. More recently, an identification and condition survey was conducted on the collections of SMAK (Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst) and the Design Museum Gent13. The plastic materials of more than 2000 objects and artworks were characterised using sensory and archival approaches or scientific analyses. Each object underwent a condition assessment and was assigned a conservation priority. Like other organic materials—wood, textiles, or paper—plastics are vulnerable to environmental and chemical factors. Ultraviolet (UV) and visible light, fluctuations in temperature and humidity, oxygen, pollutants, and unsuitable storage can compromise their chemical structure, causing discoloration, embrittlement, cracking, and loss of flexibility4,8,15,16,17,18. Unlike ‘traditional’ organic materials, plastics are harder to identify due to their chemical diversity and the visual similarity between formulations.

Tools such as the Plastic Identification Tool19 offer visual clues but are rarely sufficient. Minimally invasive analytical techniques—particularly Raman and Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopies—are preferred to identify polymer types20,21,22,23,24,25, increasingly supported by reference databases and machine learning tools26,27. When greater specificity is required, chromatographic methods, especially coupled with mass spectroscopy, are employed3,28. Composite objects further complicate identification, as degradation can vary widely even between objects made from the same base polymer, due to additives, manufacturing processes, and evolving industrial standards3,8,29,30.

The Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris (MAD) holds around 12,000 plastic objects out of 1.4 million items. The Fashion, Toys, Advertising, and Design departments house a rich, varied collection from the mid-19th century to today, including both mass-produced and unique items with diverse usage and storage histories. Identifying their materials, assessing their condition, and defining intervention strategies have thus become pressing priorities. Although several studies address these issues8,21, comprehensive visual and descriptive tools linking observable degradation patterns to specific plastic types still need to be further developed for use by professionals. This gap is critical because similar degradation symptoms may arise from different materials, complicating diagnosis and treatment planning.

This study responds by proposing a standardised framework for describing plastic degradation processes, illustrating each with representative examples and linking alterations to their potential causes. The outcome is a practical resource for preventive conservation, staff training, and consistent monitoring of MAD collections. By facilitating systematic condition assessments, it also aims to enhance communication among conservators, curators, conservation scientists and researchers, and to document the plastic objects’ condition of MAD by correlating their condition with material composition.

Objects were selected based on catalogue references to plastics, diversity of polymer types, typologies, and chronology. While the initial sample was statistically chosen, additional objects exhibiting degradation—identified by conservators—were added to inform the degradation atlas. Consequently, the final corpus is less statistically representative than other surveys13,14,31, but better suited to document deterioration phenomena.

Non-sampling methods were favoured: most analyses used a portable FTIR spectrometer equipped with an Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) accessory. Micro-sampling occurred only when necessary—particularly for coated objects, analysed from both sides to distinguish bulk polymer from surface treatments.

By providing a detailed characterisation of the material composition and condition of plastics within the exceptionally large, diverse and historically rich collections of the MAD, this study complements broader initiatives such as the POPART project8, and other international efforts13,14. While POPART and similar programmes have established general frameworks for understanding plastic degradation and developing preventive conservation strategies, the present work focuses specifically on linking observable alterations to individual polymer types within the MAD collection. It provides a collection-specific resource that documents condition trends across a uniquely diverse set of objects from mass-produced to one-of-a-kind artefacts spanning the mid-19th century to the present.

Methods

Methodology

Material names are abbreviated following the POPART notation system8, with a full list in Supplementary Table 1.

To analyse an object, a thorough visual examination was performed first. Initial identification relied on prior experience, considering the object’s shape and visible manufacturing indicators (casting burrs, vents, remnants, ejection marks, maximum thickness, apparent density). Potential markers, such as triangular recycling symbols (introduced in the 1970s), were also checked. The Plastic Identification Tool19 supported initial hypotheses, with acknowledged limitations32. A systematic photographic record was then made, and all available documentation (condition reports, catalogue records, etc.) was reviewed and compiled.

Second, when possible, ATR-FTIR spectroscopy was used (Fig. 1). If the spectrum matched a database reference, e.g. the SamCo database developed during the POPART project8 (see section ‘Characterisation Methods’), the material was identified as a component. The spectral database was expanded with new spectra from reliable sources, e.g., Griffine Industries (Nucourt, France) supplied pigmented/unpigmented, varnished/unvarnished plasticised polyvinyl chloride (p-PVC) samples.

If identification was unreliable (score lower than 0.85, see section ‘Characterisation Methods’), micro-sampling was performed and observed under a microscope, both in natural and ultraviolet light. If the two sides differed, the object was considered coated, and ATR-FTIR was done on both sides to identify the surface and bulk materials. If identical, ATR spectra confirmed the absence of coating, but further analyses could be needed (e.g. polyurethane object coated with polyurethane varnish).

Following this methodology, an object was considered mono-material if it consists of a single polymer, and composite if it contains multiple materials, each covering more than 15% of the surface. Finally, a condition assessment (see Section ‘Condition assessment’) was carried out. All relevant data, new or existing, were recorded in a publicly accessible database (Access Database: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17855344).

Condition assessment

A standardised vocabulary and an alphanumeric grading system were established to indicate damage severity. Based on POPART project8 and Keene et al.14, 20 types of degradation were identified:

-

Discoloration

-

Weeping and sticky surfaces

-

Hardening

-

Crumbling

-

Deformation

-

Folds and creases

-

Losses

-

Cracking

-

Crazing

-

Tears

-

Brittleness

-

Loss of transparency

-

Scratches

-

Lifting and delamination

-

Blistering

-

Bloom

-

Dirtiness

-

Staining

-

Damage to packaging (alterations of materials in contact with the object)

-

Handling (other degradations from handling).

Each object was visually inspected, focusing on plastic parts. Every type of degradation was assessed independently, and each assessment received a grade according to an alphabetical scale:

-

A: No degradation; object in good condition and safe to handle

-

B: Localised, limited degradation

-

C: 25-50% affected; significant portion impacted; handling difficult

-

D: Widespread degradation; object unsafe to handle.

For specific types of damage (e.g. cracks or tears), a supplementary numerical scale was used to indicate the severity of the defect:

-

1: Minor (<5 mm),

-

2: Moderate (<1 cm),

-

3: Major (<2 cm),

-

4: Major (>2 cm).

In this numerical scale, the size primarily corresponds to the length of the tear or crack, as the tears and cracks in the corpus could not be distinguished by their depth. Moreover, this scale was designed to avoid multiplying criteria, which would have made the classification more difficult to handle.

Finally, an overall condition assessment was expressed using a colour-coded system, based on the combination of individual grades:

-

Green: ≤3 ‘B’ ratings, no ‘C’ nor ‘D’; object in good condition, exhibitable,

-

Yellow: Several ‘B’ and ≤2 ‘C’ ratings,

-

Orange: ≤3 ‘C’ and few ‘D’ ratings,

-

Red: Multiple ‘D’ or 4–5 simultaneous degradations; object not exhibitable.

Database construction

The database was created using Access 2016 on Windows 10 (Access Database: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17855344) to facilitate retrieval of all information on examined MAD plastic objects, including condition assessments.

Each object has a form structured into three tabs. The first records key data (title, dating, size, and plastic composition) and whether the object could be analysed. The second details the condition assessment, listing and quantifying degradations using the classification system (‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’, or ‘D’, and when applicable, ‘1’, ‘2’, ‘3’, or ‘4’), with overall condition and space for comments. The third tab contains photographs highlighting the most visible damage; close-ups were preferred. Some fragile objects could not be fully photographed due to handling restrictions.

The database also incorporates a ‘degradation atlas’, similar to that developed in the POPART project8, listing degradations by plastic type. The main plastics identified are polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyurethane, polyethylene, polystyrene, polymethyl methacrylate and polycarbonate.

Users can search the database by plastic type (if known) or by degradation type to identify comparable cases.

Finally, a simplified form was created to define the database’s notations and terminology.

Characterisation methods

The objects were photographed using an iPhone 7 [Model A1778, 2016] in automatic mode. In addition, all items exhibiting significant damage were systematically photographed against a grey background—first in full view, then in close-up focusing on the damaged area.

Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectra were recorded using an Agilent 4100 ExoScan Series handheld spectrometer equipped with a room temperature-stabilised DTGS detector. Spectra were collected in the 4000–600 cm−1 range by averaging 32 consecutive scans at a resolution of 8 cm−1.

Spectra were compared to both Perkin Elmer and laboratory-made databases (SamCo database8), using the PerkinElmer Spectrum software. Comparisons were performed using the software’s “Search” function, which relies on a Euclidian distance. For each use of the search function, the software gives a score, which is the correlation between the analysed spectrum and the database spectra. The result of the ‘Search’ function was considered reliable when, without any issue to acquire the spectra, the score of the analysis is above 0.85.

Objects whose materials could not be identified by ATR-FTIR were sampled in non-visible areas using a scalpel. When crumbling was observed, loose fragments were used as samples. All samples were stored in glass vials and sealed with Teflon® caps.

The microsamples were observed on both sides using either a Nikon LV100D confocal microscope or a Nikon SMZ18 stereo microscope. Images were captured with a digital camera and processed using the NIS-Elements software. Observations with the confocal microscope were performed under both white light and UV.2A illumination.

If needed, the samples were analysed using an Agilent 8890 gas chromatograph coupled with an Agilent 5977 C single-quadrupole mass spectrometer (GC-MS, Agilent, USA). Samples were prepared as a 95:5 dichloromethane/methanol dilution, and 1 µL was injected without derivation. The GC was equipped with a CP-Sil 8 CB low-bleed capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm, 5% diphenyl/95% dimethyl siloxane, highly cross-linked). The temperature programme was: initial 35 °C held for 2 min, ramped at 10 °C/min to 320 °C, and held for 5.5 min. Helium was used as carrier gas at 1 mL/min column flow. Mass spectra were recorded under electron ionisation at 70 eV, with an ion source temperature of 230 °C, a split ratio of 1/80, and m/z range 35–650. Component identification was performed using ADMIS software with the NIST library.

Results

Confronting museum records with analytical characterisations

The number of objects identified as ‘plastic’ in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (MAD) collections is estimated at 12,616, based on data from the museum’s SKINsoft database. In general, MAD objects are stored in areas maintained at 19–25 °C with around 50% relative humidity. Small toys are kept in their original packaging or wrapped in acid-free tissue and grouped in cardboard boxes, while heavily damaged toys are stored individually. Larger toys are placed on open shelves, protected by polyethylene tarpaulins. Advertising collection items are kept under similar conditions in plastic boxes. Inflatables are stored either partially inflated or deflated. Films are stored flat, folded, or unfolded. Clothing is kept on hangers, in drawer, or in boxes, wrapped in Tyvek® or acid-free tissue. Accessories (hats, shoes, buttons, etc.) are stored in drawer units to minimise contact, and smaller Design collection items are boxed, while larger ones are placed on open shelves and protected by polyethylene film. These storage conditions provide context for interpreting degradation phenomena, such as sticky surfaces or exudation, observed on some objects. To illustrate the challenges of tracking ‘plastics’ and assessing their degradation, four multi-component objects were selected from different departments of the MAD for detailed characterisation and comparison with the museum’s records. Selection was guided by documentation suggesting the presence of at least PVC. PVC was chosen as a focus because it is among the plastics that exhibit the most significant degradation in museum collections. PVC objects are often considered high-priority for monitoring and preventive conservation7, which guided our selection of objects for this study.

In the Fashion and Textile Department, several raincoats by designer Popy Moreni (1985–1995) are primarily made of matte, translucent material with glossy black collars and decorative bands. Museum’s records identify them as PVC, consistent with garment labels (‘100% PVC’).

ATR-FTIR analyses of one raincoat (UF 90-35-6 A—Fig. 2a) confirmed all components as plasticized PVC (p-PVC) (scores 0.95 for transparent parts and 0.85 for black bands), except buttons, which are polyoxymethylene (POM) (score 0.75, due to poor ATR contact).

Degradation signs include slight stickiness on the collar and sleeves, indicating active plasticizer loss, a common p-PVC issue3,33,34. An inner translucent reinforcement, identified as polyethylene terephthalate (PET, score 0.97), was also present. The PET element is not part of the original structural lining but a conservation insert added at the time of the raincoat’s acquisition, intended to help maintain the garment’s shape. However, a visible weeping effect occurs between PET and PVC (Fig. 2b): PET traps migrating plasticizer, leading to accumulation. This aligns with literature noting PET-PVC contact accelerates plasticizer migration35.

A Tube Chair designed by Joe Colombo in 1969, from the Department of Modern and Contemporary Design, was selected as the second case study (Fig. 3a). Catalogue records described it as made of PVC, metal, synthetic rubber and fabric. The modular armchair consists of four hollow cylinders of varying sizes, joined by metal hooks with rubber caps. These cylinders can be arranged according to the user’s preference, allowing for a customisable seating configuration. Each cylinder is padded with foam and wrapped in a red leather-like fabric.

ATR-FTIR analyses on both sides of a detached red film fragment identified polyurethane (PU) (score 0.83). Both sides appeared identical under a binocular magnification using visible and UV lights, possibly indicating the absence of a varnish layer. Additional analyses identified unplasticised PVC (score 0.88) for the cylinders and styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR, score 0.72) for the caps (Fig. 3b).

Degradation is severe on the leather-like fabric, which shows large cracks and white efflorescence (Fig. 3c). The ATR-FTIR spectrum recorded directly on a sufficiently thick layer of efflorescence shows only the characteristic bands of adipic acid (score 0.94), without interference from the underlying PVC or substrate. This acid is a product of ester-based thermoplastic PU depolymerisation and is now considered a diagnostic marker of PU degradation36. In contrast, the PVC tubes exhibit only scratches and handling dents, while the caps have hardened with age.

The figurine Margote (Fig. 4a), a character from Le Manège Enchanté, a French animated TV series first broadcast in the mid-60s, is preserved in the Toy Department. In the museum database, it is described as ‘hard plastic’. All parts are fixed except the articulated arms. The surface is painted, except for the head and hands. Arms and hands are made of a foam-like material, with the arms coated in blue paint. ATR-FTIR analyses on one foot—at spots without white paint (Fig. 4b)— and on one cheek, indicate polyethylene (PE, score 0.96). The absence of C=O and C-O-C bands at 1725 and 1185 cm⁻1, respectively, suggests non-oxidised PE. Numerous large yellowish liquid droplets are visible on the arms (Fig. 4c), made of a flexible material unlike the rigid body. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis identified the liquid as a mixture of compounds derived from adipic acid and various hydroxyesters (Supplementary Fig. 1), while the foam is a PU elastomer. Thus, although exudation is often linked to PVC, this case shows it is not a reliable indicator of composition.

Two Swatch-style plastic watches—one black, one transparent (Fig. 5)—from the Advertising and Graphic Design Collection, catalogued simply as ‘plastic’, were examined.

ATR-FTIR identified clasps as polycarbonate (PC, score 0.98) and straps as p-PVC (score 0.97). The black watch case is either acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS, score 0.99) or styrene acrylonitrile (SAN, score 0.98), as ATR-FTIR analysis does not allow for a reliable distinction between the two (reference spectra differ by only one band out of 25). The transparent watch case is polycarbonate (PC, score 0.98). Both watches are stored in transparent polystyrene (PS) boxes (score 0.99).

Degradation is visible as sweating on the PVC straps, while the boxes show no current alterations. However, long-term risks are significant: p-PVC plasticizer migration can dissolve PS, sometimes causing partial fusion37. For the black watch, this raises conservation concerns, requiring either isolation using an inert barrier material or removal from the boxes—though the latter risks losing contextual information about their original presentation as sets.

These four examples studied as illustration show that identifying plastics based only on curators’ practices and acquisition records is unreliable (three of the four objects were not predominantly PVC). Moreover, out of the 142 objects analysed, 113 (e.g. 80% of the corpus) were found to have unknown or incorrectly recorded compositions. This reveals a lack of material knowledge, which hinders understanding of collections, given the multiplicity of plastics and their varied processing methods. Such limits inevitably affect the assessment of degradation behaviours. To address this, a dedicated object corpus was established for further study.

Elaboration of a corpus of objects for the condition assessment and degradation atlas construction

The qualifier ‘plastic material’ was used to identify an initial set of objects, as listed in the S-Museum database (SKINsoft). Other tested qualifiers proved biased or unreliable. This selection was refined through several criteria:

-

Department focus: Objects were drawn from the Department of Modern and Contemporary Design (Design Department), the Advertising and Graphic Design Collection (Advertising Department), the Toy Collection (Toys Department) and the Fashion and Textile Department (Fashion Department), which hold the largest number of plastics, spanning from the late nineteenth century to today. This yielded 9197 objects: Advertising Department: 2563; Fashion Department: 1517; Design Department: 721; Toys Department: 4396 (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for proportions).

-

Statistical sampling: Using Keene’s framework for collection audits14 at a 90% confidence level, a statistically representative sample of 285 items was selected from the 9197 previously identified objects, corresponding to the sample size required for this confidence level and a 5% margin of error. The distribution across departments is as follows: Advertising Department: 77; Fashion Department: 45; Design Department: 30; Toys Department: 133 (Fig. 6).

-

Object diversity: As objects were stored in varied arrangements, the sample was refined to ensure diversity of plastic forms (foams, flexible plastics, coated canvas, moulded hard plastics, multi-material objects…). A temporal criterion was also applied, limiting manufacturing dates to 1910 onward— corresponding to the decade of the first fully synthetic plastic (Bakelite)—in order to avoid including non-plastic materials.

-

Degradation focus: Particular attention was given to object series or items from the same brand produced at different times, to compare condition. An additional 10 degraded objects were included: Design (3), Fashion (6) and Toys (1).

Ultimately, 142 objects were thoroughly analysed (Advertising: 13; Fashion: 41; Design: 30; Toys: 58), including the 10 objects added specifically for their degraded condition. Their inclusion did not compromise representativeness, and overall distribution remained consistent with theorical statistical sampling (Fig. 6), though the Fashion and Design departments were slightly overrepresented.

Material identification

To create the degradation atlas, material identification was required. Among the 142 objects studied, 13 could not be identified—mainly flexible objects from the Toys (8) and Fashion (5) departments. For these, ATR-FTIR yielded no plausible result, either directly on the object or through recto-verso micro-sample analysis. An object’s material was considered identified when the ATR-FTIR spectrum produced a score >0.85 without micro-sampling. Identified materials are summarised in Fig. 7a. Objects were classified as either ‘mono-material’ or ‘multi-material’ (composite). An object is mono-material if composed of a single piece or if analyses at different points indicate the same polymer. When several materials are present and each covers more than 15% of the surface, the object is classified as composite.

PVC is the most prevalent material, identified in 50 objects (including 4 added specifically for degradation), nearly half of which are composites. Its proportion in the corpus (35%) exceeds that of the POPART project (13%, 2008–2012)8, confirming PVC’s ubiquity in twentieth-century heritage collections due to flexibility and low cost. Thanks to coated PVC references in our ATR-FTIR database, five coated objects were identified: four with acrylic-based layers (varnish or paint) and one with Shellac, a varnish used since the seventeenth century38. Other main polymers include PU (28 objects), PE (25), PS (17), ABS (8) and polyamide (PA, 8). Cellulose nitrate (CN) was mostly found in older items (e.g. toys, fashion accessories), while melamine-formaldehyde (MF) and polybutylene terephthalate (PBT) were rare, as expected in a corpus of flexible or degraded plastics. PMMA, ABS, SAN, and SBR appeared only in mono-material objects, reflecting structural or aesthetic uses, which do not favour association. Certain materials were specific to a single collection, due to their historical use: ABS only in Toys (Legos® since the 1960s), MF in Design (kitchenware)39,40. The study focused on the four main polymers—PVC, PU, PE, and PS—whose distribution across departments reflects typical applications (Fig. 7b): PVC, PS and PE predominate Toys Department (inexpensive, short service life41), while PU, mainly coated fabrics, dominates Fashion Department (e.g. footwear), valued as a ‘high-quality’ leather substitute42. PU-based varnishes could also appear, which may bias analyses when the layer is thick enough to be detected as bulk material.

Overall, 75% of the objects are mono-material and 25% multi-material (Fig. 7a). PU occurs mostly as mono-material (23 objects, 82% of PU-containing objects), reflecting its versatility, which often eliminates the need for combination to achieve specific shapes or textures42. In contrast, PVC, PE and PS show a more balanced distribution: PVC (48% mono-material/52% composite), PE (40%/60%), PS (35%/65%).

We also examined material associations in composite objects containing one of the four main polymers (Fig. 8). PVC (Fig. 8a) is most frequently combined with polyolefins (PE, PP)—notably, PE + PVC in 12 objects—and with styrenic polymers (PS, ABS, SAN, SBS), consistent with twentieth century industrial and heritage formulations aimed at improving PVC’s mechanical or thermal properties. PVC is also often coated with vinyl acrylic varnishes (5 of 50 PVC objects). PS is the most common co-occurring polymer, present in 6 objects with PVC and 7 with PE, including 4 objects containing all three (Fig. 8b). Figure 8c, for PE-containing objects, confirms its predominant association with PVC and PS, while Fig. 8d shows that PU, found in only eight composite materials (18% of PU-containing objects), has no preferred association within the studied dataset.

Some polymer combinations may accelerate differential aging in heritage objects. PVC is often central in such blends, frequently associated with PE and PS—polymers with poor physicochemical compatibility. Risks include plasticizer migration between PVC and PE or PS, and mechanical fragility at incompatible interfaces (e.g. PS-PE)8,9,35,37.

These findings demonstrate the diversity of polymers, particularly in composites, and confirm that visual identification alone is insufficient. PVC and PU dominate the studied collections, and their association deserves particular attention, as both undergo specific degradations (exudation and yellowing for PVC, efflorescence for PU, etc.). The prevalence of composites further complicates conservation, since polymer interactions may accelerate degradation. Condition assessment was therefore conducted at both object and material levels.

Condition assessment

The condition of the 142 analysed objects was assessed using four categories: ‘green’ (good), ‘yellow’ (fair), ‘orange’ (poor), and ‘red’ (severely degraded) (see Part ‘Condition assessment’ and Fig. 9). Overall, 46% are in good condition, while 54% exhibit varying degrees of degradation (Fig. 9a), a bias partly reflecting the focus on damaged samples. This distribution remains similar for mono-material and multi-material objects (Fig. 9b, c), despite the latter being expected to deteriorate faster due to interactions between polymers. Only two cases revealed such interactions: PVC plasticizer migration melting adjacent PS (Toys Department) and PU accelerating PVC discoloration (Design Department)37,43. Most severely degraded items (23/29 red) are mono-material Fashion accessories—mainly PU-based shoes and hats from 1960 to 1995. Among all objects, tears, transparency loss and blistering were rare (4, 5 and 7 cases), while discoloration (44), delamination (41), weeping (39), staining (36) and surface dirt (36) were the most frequent issues, independent of collection or period.

The condition of the objects varies across collections (Fig. 10). Since a large proportion of objects in the dataset comes from the Toys collection (40% of the corpus), the distribution pattern of this collection closely mirrors that of the overall dataset (Fig. 10a). In contrast, the Fashion collection is far more degraded, with 82% of objects classified as deteriorated (Fig. 10b). The Advertising and Design departments (Fig. 10c, d, respectively) contain the fewest severely degraded objects, likely because the studied items are relatively recent (average manufacturing dates: 2003 and 1988, respectively). To better understand these differences, condition data were analysed by polymer type (Fig. 11a, b) and by manufacturing date (Fig. 11c).

Among the 13 unidentified objects, 8 show signs of degradation, including 4 in critical condition (‘red’) (Fig. 11a). This is expected, as materials of unknown composition are harder to conserve without targeted strategies.

PU objects are the most degraded: 54% of mono-material (11/23) and 20% of composites (1/5) exhibit severe deterioration (Fig. 11a, b). This largely explains the poor condition of the Fashion collection, where PU is over-represented (49% of objects, 75% degraded). Typical alterations include sticky surfaces (39% overall, 55% in Fashion) and weeping (36% overall, 50% in Fashion), both linked to photo-oxidation and chain scission, producing adipic acid (‘blooming,’ observed in 14% of PU)44. Delamination and folds/creases affect 32% of PU objects (45% in Fashion). Packaging-related damage is less frequent (18%) but often severe, as sticky PU adheres irreversibly to packaging materials (Tyvek® or silk paper). Degraded PU objects span mainly from 1960 to 2015, showing that even relatively recent fashion items can deteriorate rapidly, likely due to shortened product lifespan.

PVC-based objects, whether mono- or multi-material, are evenly split between good and poor condition (Fig. 11a, b). The most frequent degradation is discoloration, particularly yellowing, seen in 30% of PVC objects and linked to dehydrochlorination17,45,46. Weeping, often with sticky surfaces, occurs in 22% of cases—affecting 30% of mono-material PVC but only 15% of composites. This alteration linked to plasticizer exudation3,4,47,48 likely contributes to the dirtiness observed in 24% of objects and may explain the hardening found in 12%. Folds and creases appear in 20% of PVC items, mostly in Fashion and Design collections, where PVC was used as plasticized films (e.g. raincoats, inflatable furniture).

By comparison, mono-material PE and PS objects are generally stable: 80% and 100% are rated green or yellow, respectively. However, only 40% of composites containing PE and PS are in good condition (green). For PE, discolouration affects 28% of objects, which can also accelerate pigment degradation49. Lifting and delamination occur in 20% of multi-material PE objects, mainly painted toys, due to poor adhesion to the substrate on thermoformed items50. Dirtiness (24%) and scratches (20%) are also frequent. For PS-containing objects, the main issue is scratching from repeated use (41%), followed by discolouration (35%), attributed to photo-oxidation51,52; among mono-material PS objects, 50% show such alterations.

The condition of the objects (green, yellow, orange, red) was also correlated to their manufacturing date (Fig. 11c). As expected, older objects tend to be in poorer condition than more recent ones, with most degraded items (yellow to red) dating between 1960 and 1990. Only three objects in the dataset predate 1950: two yellow-coded from 1910 and one red from 1920, their scarcity reflecting both limited early plastic production and severe degradation. Between 1950 and 1969, plastics appear gradually but often in degraded condition. For 1960 alone, objects range from green (n = 1) to yellow (n = 1) to red (n = 3), with additional red-coded items from 1965, 1966, and 1969, showing that many of the earliest plastics already display severe deterioration. From 1970 to the late 1980s, the number of plastic objects increases markedly, but their condition is uneven: while many remain stable, a significant share — especially from the early 1970s—shows degradation. From the 1990s onward, preservation improves sharply, with most items rated green, apart from a few red objects dated 1993 and 1995. This trend may reflect both their more recent manufacture and improvements in polymer formulations or conservation practices.

Overall, age is a major factor in condition, but not a strict predictor: composition, manufacturing quality, and storage conditions also play key roles in long-term stability.

Discussion

This study examined plastic objects from the Design, Toys, Fashion and Advertising departments of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs to establish a degradation atlas. A total of 142 objects were analysed using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy, with particular attention paid to degraded items. Two-thirds remain handleable, though condition varies greatly by collection: the Fashion collection is the most degraded, with 40% unhandlable, while 85% of Advertising objects are pristine.

Material analysis shows PVC as the most prevalent plastic, followed by PU, PE, and PS. Distribution differs by collection: PE and PS dominate Toys collection—often in with PVC, which alone accounts for over half of the Toys items; PU predominates in Fashion. Composite objects are frequent, with PVC, PE and PS often combined.

Cross-analysis of material and condition indicates PU is the most degraded, while ~ 40% of PE, PS, or PVC containing-objects remain in good condition.

Chronologically, few objects predate 1950. The 1960s–70s are critical decades, with many degraded items. The 1980s–90s show mixed preservation, while post-1995 items are generally stable. No strict correlation exists between manufacturing date and condition, pointing to factors such as composition, storage, and use.

All results, with photographs, are compiled into an Access database (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17855344), organised by material and degradation type, enabling conservators and restorers to consult the tool according to their needs. A complementary condition assessment tool further enriches the database. This system may eventually support plastic identification, as specific degradation patterns are systematically associated with particular materials. Nevertheless, given the diversity and ongoing evolution of plastic formulations, such identifications must remain cautious and hypothesis-driven.

Despite logistical challenges—particularly the need for staff to handle numerous objects in a limited timeframe and the difficulty of assembling interdisciplinary teams—collections surveys remain essential for advancing knowledge of plastics in heritage contexts. This is especially true for collections of mass-produced objects, where diversity in formulations, origin, date, and condition increases the likelihood of observing a wide range of degradation types. Such surveys also provide a basis for curative treatment research, as degradation patterns critically influence the range of feasible interventions. Ideally, selected objects should be regularly monitored. Ultimately, this work underscores the urgent need for new preventive and curative strategies to ensure the long-term preservation and transmission of plastic artefacts central to design and material history.

Data availability

Access database is provided at : https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17855344.

References

Plastics - The Facts 2022, Plastics Europe, 2022.

Keneghan, B. A survey of synthetic plastic and rubber objects in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Mus. Manag. Curatorsh. 19, 321–331 (2001).

Gassmann, P., Bohlmann, C. & Pintus, V. Towards the understanding of the aging behavior of p-PVC in close contact with minced meat in the artwork POEMETRIE by Dieter Roth. Polymers 15, 4558 (2023).

Rijavec, T. et al. Heritage PVC objects: understanding the diffusion-evaporation of plasticizers. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 235, 111270 (2025).

Rizzo, A. & Scaturro, S. Already Out of Fashion: The Fashionable Rise and Chemical Fall of Thermoplastic Polyurethane (Contemporary Art, 2021).

King, R., Grau-Bové, J. & Curran, K. Plasticiser loss in heritage collections: its prevalence, cause, effect, and methods for analysis. Herit. Sci. 8, 123 (2020).

Williams, R. S. Care of plastics: malignant plastics, https://cool.culturalheritage.org/waac/wn/wn24/wn24-1/wn24-102.html (accessed November 15, 2024).

Lavédrine, B., Fournier, A. & G. Martin, G. Preservation Of Plastic Artefacts (POPART) (CTHS, 2012).

Rijavec, T. Plastics in heritage collections: poly(vinyl chloride) degradation and characterization. ACSi 67, 993–1013 (2020).

van Oosten, T. B. Properties of Plastics: A Guide for Conservators. (Getty Publications, 2022).

Waentig, F. Plastics in Art: A Study From the Conservation Point of View (Imhof, 2008).

Keneghan, B. & Egan, L. (eds) Plastics: Looking at the Future and Learning from the Past, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1179/sic.2009.54.3.192 (accessed August 5, 2025).

Hendrickx, H., van der Velde, E. & Kockelkoren, G. Save the plastics! Identification and condition survey in Belgian museums, https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.104114. (2023).

Keene, S. Audits of care: a framework for collections condition surveys. in: S.Knell (ed.) Care of Collections 1st edn (Routledge, 1994).

Ankersmit, B. & Stappers, M. H. L. Managing Indoor Climate Risks in Museums (Springer International Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-34241-2 (2017).

Cosaert, A. et al. Tools for the Analysis of Collection Environments: Lessons Learned and Future Development (2022).

Rijavec, T., Strlič, M. & Kralj Cigić, I. Damage function for poly(vinyl chloride) in heritage collections. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 211, 110329 (2023).

Féau, E. & Le Dantec, N. Vade-mecum de Conservation Préventive, (2005). https://c2rmf.fr/vademecum-de-conservation-preventive (accessed September 12, 2024).

Plastic Identification Tool (n.d.). https://plasticidentificationtool.nl/ (accessed April 28, 2025).

Bell, J., Nel, P. & Stuart, B. Non-invasive identification of polymers in cultural heritage collections: evaluation, optimisation and application of portable FTIR (ATR and external reflectance) spectroscopy to three-dimensional polymer-based objects. Herit. Sci. 7, 95 (2019).

Keneghan, B. et al. 1.3. Chemical composition/structural characterisation using spectroscopic techniques. in: Lavédrine, B., Fournier, A., Martin, G. (eds) Preservation of Plastic Artefacts (POPART), CTHS 43–57 (UCL, 2012).s

Saviello, D., Toniolo, L., Goidanich, S. & Casadio, F. Non-invasive identification of plastic materials in museum collections with portable FTIR reflectance spectroscopy: reference database and practical applications. Microchem. J. 124, 868–877 (2016).

Klisińska-Kopacz, A. et al. Raman spectroscopy as a powerful technique for the identification of polymers used in cast sculptures from museum collections. J. Raman Spectrosc. 50, 213–221 (2019).

Lazzari, M. & Reggio, D. What fate for plastics in artworks? An overview of their identification and degradative behaviour. Polymers 13, 883 (2021).

Reggio, D., Saviello, D., Lazzari, M. & Iacopino, D. Characterization of contemporary and historical acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS)-based objects: pilot study for handheld Raman analysis in collections. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 242, 118733 (2020).

Rijavec, T., Ribar, D., Markelj, J., Strlič, M. & Kralj Cigić, I. Machine learning-assisted non-destructive plasticizer identification and quantification in historical PVC objects based on IR spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 12, 5017 (2022).

Saad, M., Bujok, S. & Kruczała, K. Non-destructive detection and identification of plasticizers in PVC objects by means of machine learning-assisted Raman spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 322, 124769 (2024).

La Nasa, J., Biale, G., Ferriani, B., Colombini, M. P. & Modugno, F. A pyrolysis approach for characterizing and assessing degradation of polyurethane foam in cultural heritage objects. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 134, 562–572 (2018).

Chu, C. et al. Surveys of plastics in post-1950 non-published book collections. Restaur. Int. J. Preserv. Libr. Arch. Mater. 44, 129–165 (2023).

Macro, N., Ioele, M. & Lazzari, M. A simple multi-analytical approach for the detection of oxidative and biological degradation of polymers in contemporary artworks. Microchem. J. 157, 104919 (2020).

Krieg, T., Mazzon, C. & Gómez-Sánchez, E. Material analysis and a visual guide of degradation phenomena in historical synthetic polymers as tools to follow ageing processes in industrial heritage collections. Polymers 14, 121 (2021).

Narcyz, A. Identification des plastiques dans les collections patrimoniales: analyse d’un outil numérique d’identification, le Plastic Identification Tool (2023).

Colliander, A. The conservation of a vinyl-upholstered chair: PVC degradation and conservation, in: Stichting Ebenist, 142–148 (Academia, 2017).

Shashoua, Y. R. Inhibiting the deterioration of plasticized poly (vinyl chloride) - a museum perspective, Technical University of Denmark, 2001. http://www.cwaller.de/didaktik_teil4/shashoua_2001.pdf (accessed May 3, 2024).

Royaux, A. et al. Conservation of plasticized PVC artifacts in museums: Influence of wrapping materials. J. Cult. Herit. 46, 131–139 (2020).

de, S. F. et al. A preliminary approach for blooming removal in polyurethane-coated fabrics. Conserv. Patrim. 47, 28–42 (2024).

Pedrosa, A., Río, M. D. & Fonseca, C. Interaction between plasticized polyvinyl chloride waterproofing membrane and extruded polystyrene board, in the inverted flat roof. Mater. Constr. 64, e037 (2014).

Barr, E. Degree of cure in thermosetting resins. Ind. Eng. Chem. 48, 72–74 (1956).

Sabatini, F. et al. A thermal analytical study of LEGO® bricks for investigating light-stability of ABS. Polymers 15, 3267 (2023).

Ebner, I. et al. Release of melamine and formaldehyde from melamine-formaldehyde plastic kitchenware. Molecules 25, 3629 (2020).

Cantin, S. & Fichet, O. Formulation et vieillissement des PVC plastifiés, in: Vieillissement des polymères industriels, ISTE Group, 2025:29–50. https://www.istegroup.com/produit/vieillissement-des-polymeres-industriels-2/ (accessed February 27, 2025).

Lu, S. et al. Preparation of flame-retardant polyurethane and its applications in the leather industry. Polymers 13, 1730 (2021).

Bowden, M. et al. Thermal degradation of polyurethane-backed poly(vinyl chloride) studied by Raman microline focus spectrometry. Polymer 35, 1654–1657 (1994).

Salinas, C. R. & Ferrazza, L. Real or faux leather? Luxury or ready-to-wear mass production? Characterization of three TPU shoe coatings (ca. 1970) from the Kunstmuseum Den Haag fashion collection. Conserv. Patrim. 47, 60–77 (2024).

Cruz, P. P. R., da Silva, L. C., Fiuza-Jr, R. A. & Polli, H. Thermal dehydrochlorination of pure PVC polymer: part I—thermal degradation kinetics by thermogravimetric analysis. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 138, 50598 (2021).

Sánchez-Jiménez, P. E., Perejón, A., Criado, J. M., Diánez, M. J. & Pérez-Maqueda, L. A. Kinetic model for thermal dehydrochlorination of poly(vinyl chloride). Polymer 51, 3998–4007 (2010).

Bujok, S. et al. Migration of phthalate plasticisers in heritage objects made of poly(vinyl chloride): mechanical and environmental aspects. J. Environ. Manag. 375, 124234 (2025).

Tüzüm Demir, A. P. & Ulutan, S. Degradation kinetics of PVC plasticized with different plasticizers under isothermal conditions. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 132 (2015).

Micheluz, A., Angelin, E. M., Lopes, J. A. & Melo, M. J. & Pamplona, M. Discoloration of historical plastic objects: new insight into the degradation of β-naphthol pigment lakes. Polymers 13, 2278 (2021).

Brewis, D. M. & Briggs, D. Adhesion to polyethylene and polypropylene. Polymer 22, 7–16 (1981).

Takimoto, K., Takeuchi, K., Ton, N. N. T. & Taniike, T. Exploring stabilizer formulations for light-induced yellowing of polystyrene by high-throughput experimentation and machine learning. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 201, 109967 (2022).

Angelin, E. M., Cucci, C. & Picollo, M. What about discoloration in plastic artifacts? The use of fiber optic reflectance spectroscopy in the scope of conservation. Cult. Sci. Del. Color Color Cult. Sci. 14, 87–93 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the collaborators from the MAD Paris, particularly the collection registrars, collections managers and conservators, which allowed us to perform our study seamlessly. The authors also thank Kamal MERGOUM, Research and Development director of Griffine Industries, who has provided the samples to enhance the ATR-FTIR Database. This work has benefited from State support managed by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche under the integrated investment program for the future included in France 2030, bearing the reference ANR-17-EURE-0021 Ecole Universitaire de Recherche Paris Seine Humanities, Creation, Heritage – Heritage Science Foundation (Eco-PVC project).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L. and H.T.: Conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, visualisation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. N.B.: Conceptualisation, funding acquisition, methodology, supervision, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, visualisation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. G.B., M.D., F.B., O.F., and S.C.: Conceptualisation, funding acquisition, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Larrieu, M., Tessier, H., Balcar, N. et al. Identification and degradation atlas of plastic objects in the collections of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris. npj Herit. Sci. 14, 70 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02337-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-026-02337-6