Abstract

Background

The basis for a high-performing and resilient healthcare system is having a common, precise, and scientifically accurate language used across all stakeholder groups. However, such a common language is lacking for obesity. Therefore, the European Association for the Study of Obesity undertook a taxonomy initiative to provide standardised language for obesity as commonly used from policy to practice for other major policy-prioritised non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

Methods

An online Delphi consensus study was conducted, involving a panel of experts representing stakeholder groups of policymakers, healthcare professionals, people with lived experience, and researchers. Based on the understanding of obesity as an adiposity-based chronic disease, 54 statements demarcated into definition, scope and contextual usage were developed across six themes: Definition of obesity, Causes, onset and progression, Obesity prevention, Screening and early diagnosis, Treatment and management, Obesity consequences.

Results

Of the 194 invited experts, 70 (36%), 63 (33%), and 58 (30%) experts participated in rounds one, two, and three, respectively. Consensus was achieved on 70% of the proposed definitions, scope, and contextual usage after round one, 94% after round two and 100% after round three. The Definition of Obesity theme included distinctions between population-level indicators and individual-level signs of obesity, and how pre-obesity was defined. The Causes, Onset and Progression theme characterised the timing of obesity development. The Obesity Prevention theme explicitly differentiated between health promotion and primary prevention. Both the Screening and Early Diagnosis, and the Treatment and Management themes defined concepts supporting a continuum of care model. The Consequences of Obesity theme encompassed health and socio-economic outcomes.

Conclusion

The taxonomy provides a contemporary evidence-based language about obesity that aligns with language used for policy-prioritised NCDs. The taxonomy is useful for education, advocacy, and communication and can be used by policymakers, healthcare professionals, people living with obesity, researchers, and health system users.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The basis for a high-performing and resilient healthcare system is one where there is a common, precise, understandable, and scientifically accurate language used amongst and across all stakeholder groups [1, 2]. However, such a common language is lacking for obesity. Although the World Health Organization (WHO) defines obesity as an “abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that can impair health,” the debate regarding the status of obesity as a disease is still polarising in modern medicine, policy and society [3]. An important ramification is that health service delivery systems do not have a chronic disease pathway for obesity embedded in them. The worldwide prevalence of obesity has nearly tripled since 1975, and it is estimated that by 2030 over one billion people globally will be living with obesity [4]. Despite the increasing prevalence and international recognition of obesity as a chronic disease, the language used to describe obesity is often inconsistent, inaccurate, and insufficiently person-centred, which can contribute to misunderstanding, stigma, and discrimination [5, 6].

The importance of language has been highlighted in the field of chronic disease management for obesity and diabetes, and it is a major determinant of the patient-provider relationship, as well as clinical outcomes [7]. The language used by healthcare professionals can impact people living with obesity and those who care for them [8, 9]. Studies indicate the use of inaccurate and inappropriate language can lead to physiological and behavioural changes that contribute to poor metabolic health and unfavourable shifts in body composition [6, 9]. There is a critical gap between the scientific evidence supporting obesity as a neurometabolic disease and a conventional understanding of obesity underpinned by a misconception that obesity is due to “lack of individual will power” and as just being someone’s body size [6, 10]. Misconceptions are further amplified by inaccurate sources of information about obesity from the internet, family, friends, media, and mobile applications [11]. Highlighting this, the Awareness, Care, and Treatment In Obesity maNagement–International Observation (ACTION‐IO) study revealed a need to increase understanding of obesity and to improve education concerning its physiological basis and clinical management [12].

Language used by other stakeholders such as policy makers and regulatory authorities can profoundly impact on how obesity is addressed in the healthcare system from primary prevention, through to diagnosis and screening, treatment, and long-term management. Through initial interaction within the extensive network of the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) [13] it became clear that the scientific evidence for obesity as a chronic disease is not widely circulated amongst stakeholder communities. Policies to date have largely focused on the primary prevention of obesity, but the resulting efforts have been generalised health promotion that crosses all dietary-related chronic diseases, namely cancer, cardiovascular disease and diabetes rather than specific obesity targeted actions [14]. However, there is a critical gap in the attention devoted to other essential aspects of addressing obesity, such as screening, early diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management. This observation aligns with the recommendations put forth by NCD frameworks, which underscores the need for a comprehensive approach. Shared language and a common meaning around key words in a discussion is fundamental to effective communication [15], building mutual understanding and implementation of obesity within the NCD framework. Therefore, the objective of this taxonomy project initiated by the EASO is to provide a common obesity language which can be used by all stakeholders from policy to practice and research.

Methods

Study design

We conducted an online Delphi consensus study. This method involved seeking the opinions of a group of experts to assess the extent of their agreement and resolve any disagreements on obesity related terms through discussion and level of consensus [16]. The Delphi-method has been used to establish consensus across a range of subject areas, with several in the field of obesity [17, 18].

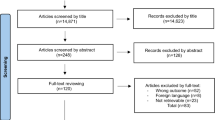

For each round of the Delphi survey, an instruction video was made to present the content to all participants. Afterwards, the participants received an email link to an online survey (Appendix 5) in which they were asked to rank the definitions based on their level of agreement with them using a visual analogue scale from (0 ‘not at all’ to 10 ‘very important’). A free-text box was added to each statement in the survey, providing the opportunity to elaborate upon or explain responses. In each round, basic participant demographics of the stakeholder group and country of residence were collected. After each round, the content was updated by incorporating the comments. Following this, each participant received an online survey which only included statements where consensus was not reached in the previous round. Revised statements were presented alongside the original statements from the previous round, the group’s response (percentage agreement/disagreement) and suggestions. For each round, there was an interval of 3 weeks to complete the survey. Delphi participants were invited to every round independent of their response(s) to previous rounds. The Delphi process was stopped for each statement when consensus was reached.

Research team and Delphi participants

A core research team comprised of EASO representatives, provided strategic input and practical management of the Delphi study, and two independent researchers, who conducted the study set-up, the data collection and performed the analyses. The core research team identified members of the sounding board and Delphi participants based on the following criteria: first, ensuring a broad range of different stakeholders from clinicians (general practitioners, surgeons, physicians), dietitians, industry, nurses, patient advocates, payor community, physiotherapists, policymakers, and researchers. Secondly, experts were invited from different geographical locations within Europe to ensure they were represented. Third, a combination of prominence in the field of obesity and the H-index was used to identify experts in research. Based on this, the sounding board included 14 experts who supported the development of the themes and statements and discussed the survey results. For the Delphi, in addition to the above criteria, leaders of national organisations who are part of EASO were included to ensure input from different national contexts and thus were also invited. We liaised with The European Coalition for People living with Obesity (ECPO) in order to include individuals with the lived experience of obesity in our Delphi survey panel. This process resulted in the identification of 194 experts who were eligible to participate in the Delphi panel.

Content development

Themes and concepts were derived from a literature review centred on the needs and challenges for various stakeholder groups in addressing obesity as a chronic disease [19,20,21], the “One Voice Exercise: Modified Delphi” among experts on the language and scope of obesity [22], and other NCD frameworks [23, 24]. The core research team developed the structure of the taxonomy based on this evidence and grounded it in the understanding of obesity as an adiposity-based chronic disease. The sounding board was presented with this structure during the first engagement meeting, and they provided feedback through group discussions guided by a decision tree scheme. Based on comments from the sounding board, the taxonomy structure reduced from seven to six themes (Fig. 1) which were: Definition of obesity; Causes, onset and progression factors, Obesity prevention, Screening and early diagnosis; Treatment and management; and Obesity consequences, were formed for the Delphi rounds. Across the themes, 18 concepts were developed, and each concept was further divided into a definition, scope, and context layer, resulting in 54 different statements that had to be ranked.

The EASO obesity taxonomy consists of six themes: Definition of obesity; Causes, onset and progression factors, Obesity prevention, Screening and early diagnosis; Treatment and management; and Obesity consequences. The themes are subdivided into concepts, with each concept further broken down into a definition, scope, and context layer.

Data acquisition and analysis

An online software system (SurveyMonkey) was used to build a secure, web accessible, questionnaire. We instructed the Delphi participants to reflect on their knowledge of obesity and rank each definition on level of agreement by using a visual analogue scale (from 0 ‘not at all’ to 10 ‘very important’). A free-text box was added within each statement of the survey, providing the opportunity to elaborate or explain responses. The six themes were presented in a random order generated by the survey software for the participants. The questionnaire could be completed over several sessions, and there was an option to amend ratings before submitting it. The level of agreement was assessed by quantitative analyses supplemented with a synthesis of the free text responses. The quantitative analysis was performed based on the answers from the scale of agreement (0 not at all to 10 completely agree) and calculated as the percentage of positive responses [7,8,9,10] divided by the total completed responses. The free text responses were synthesised by two independent researchers and evaluated for relevance and substance. In the case of disagreement, the core research team resolved this through group discussion.

Responses to the survey were categorised as follows:

-

Consensus was defined a priori as ≥75% rates 7–10 and <15% rates 0–3 agreement indicating consensus [25] and no dissenting or relevant comments based on an evaluation of the free text comments.

-

Approaching consensus was defined a priori as 60% ≤ x < 75% rates 7–10 OR ≥ 75% rates 7–10 AND > 15% rates 0–3 or dissenting or relevant comments in the free text.

-

Half consensus was defined a priori as 50% ≤ x < 60% rates 7 to 10 or dissenting and/or relevant comments in the free text.

-

No consensus was defined a priori as <50% rates 7 to 10 or dissenting and/or relevant comments in the free text.

Based on these criteria, the definitions kept being refined for the subsequent rounds of the Delphi study using the following principles:

-

If Consensus: include all statements without adjustments.

-

If Approaching: include all definitions in the next round, and check if they can be improved by adjusting them based on the rating and comments of statements.

-

If Half consensus: include consensus all definitions in the next round, and check if they can be improved by adjusting them based on the rating and comments related to statements.

-

If No consensus: create new definitions based on the input from the previous round and/or a new literature search.

Results

The Delphi survey was conducted between 14 March and 19 September 2023 in three phases. Of the 194 obesity experts who were invited to take part in this three-phase Delphi exercise, seventy (36% participated in round one 63 (33%) in round two and 58 (30%) in round three of the survey. More than 10 professions and 30 countries were represented (based on participants who completed at least one round of the Delphi) (Tables 1 and 2). Out of the 70 involved in round one, 63 and 58 participants participated in rounds, two and three, and 57 (81%), 48 (76%) and 51 (88%) completed the survey in each respective round.

Table 3 shows the panel’s aggregate rankings for each definition by round. Of the 54 proposed definitions in round one, consensus was reached for 51 (94%) of the definitions, and the remaining three were classified as approaching, half and no consensus per the predefined thresholds. Based on a synthesis of the comments, these three plus an additional 13 definitions did not reach consensus during round one. The absence of consensus was most apparent in Theme 1 (Definition of obesity) and Theme 2 (Causes, Onset and Progression factors) (Appendix Table 1). These comments centred on issues such as “incorrect tone”, “not sufficient”, “too complicated”, “defining the wrong concept”. The 16 definitions were revised by the core team and distributed for round two. The 63 members involved in round two reached consensus on 13 out of 16 definitions per the predefined thresholds, with the remaining three items classified as Approaching consensus. Based on the assessment of the comments, these same three definitions from round two did not obtain consensus (Appendix Table 2). These comments centred on issues such as “too vague”. Again, these definitions were revised by the core team. In round three, 58 members participated in evaluating the remaining 3 definitions and they reached consensus both in the rankings and the comments. Thus, after three rounds of the Delphi process 54 definitions reached consensus.

Achieving consensus proved most challenging for Theme 1 (Definition of Obesity) and Theme 2 (Causes, Onset, and Progression Factors) (Table 3). Three statements (concept of pre-obesity, context layer; concept of signs, definition layer; concept of progression factors, scope layer) required three rounds before reaching consensus. Six concepts (Obesity Definition, Health Promotion, Obesity Management, Obesity Treatment and Management Outcomes, Shared decision-Making, Obesity Health Complications) only required one round to reach consensus for their definition, scope, and context layers. Thirteen statements, which initially reached consensus through quantitative analyses (≥75% rates 7–10 and <15% rates 0–3) were rephrased and circulated for a second and/or third Delphi round, as they did not achieve consensus, based on the qualitative analyses (Table 3).

As a result of the process, some notable elements emerged. In the Definition of Obesity theme, it emerged that although there is agreement about the definition of obesity, the definition of pre-obesity (e.g. overweight) was more challenging. Even though the terminology aligns with that used for other policy-prioritised NCDs (e.g. diabetes), the shift in language, the subtleties of the shift in focus to adipose tissue rather than weight were not agreed as readily. In the Causes, Onset and Progression Factors theme, the concept of progression factors was most challenging for consensus agreement. Although the scope layer ultimately achieved 92% consensus, there was nuance and ambiguity related to the included factors that increase the severity of obesity. For the Obesity Prevention theme ultimately, a clear distinction was made between health promotion and primary prevention. It took two rounds of the Delphi to make the distinction for the scope layer of primary prevention, and even then, the definition only achieved an 84% consensus. The fourth theme of Screening and Early Diagnosis presented challenges for defining the scope of each of the concepts. Ultimately a compromise was reached between having a fully exhaustive list of elements versus having guiding principles. For the Treatment and Management theme, there was a focus on what treatment actually consists of. A 94% consensus was reached for a definition that used the broad term of “healthcare” delivered by a “healthcare professional”. For the theme of Obesity Consequences, although consensus was always high, there were concerns raised about potential misinterpretations of the wording that obesity places pressure on health care costs, but not the veracity of the statement.

Discussion

This Delphi survey achieved consensus on 54 statements, which results in a taxonomy that can be used to support and align the way we speak about obesity using the standard vocabulary of policy-prioritised NCDs.

The taxonomy was structured around six main themes which were derived from language frameworks used in other NCDs [23, 24]. Obtaining consensus was most challenging in Theme 1 (Definition of obesity) and Theme 2 (Causes, Onset and Progression factors) (Table 3). These results reflect the ongoing discussion regarding the status of obesity as a chronic disease [7]. The obesity taxonomy has a particular focus on bridging the gap between scientific knowledge and the conventional narrative around obesity, as there is a great need to increase the understanding of obesity and to improve education concerning its physiological basis [12]. The obesity taxonomy harmonises the language of obesity with that of other policy-prioritised NCDs to support the recognition of obesity as an adiposity-based chronic disease which is characterised by the function, total amount, and distribution of adipose tissue [19].

An important element of the taxonomy is that it makes a distinction between the individual level and the population level. For example, within theme 1, the concept of indicators applies to the presence of obesity at the population level whereas the concept of signs applies to the presence of obesity at the individual level. These concepts are useful when interpreting body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) which is a useful indicator for screening and epidemiological studies but is less useful at the individual level. Importantly, BMI on its own is insufficient for making a clinical diagnosis of obesity as the limitations of BMI in identifying adiposity at the individual level are well known [10]. These observations are reinforced in our study by a substantial consensus level of 95% regarding the following definition: “At the individual level, an investigation of signs of obesity includes more than just measuring weight or BMI”. To shift the emphasis away from weight and BMI, the terms “function” and “distribution” were included into the definition of pre-obesity and obesity (theme 1). By using the term “pre-obesity,” we harmonise the terminology of obesity with that used by other policy prioritised non-NCDs, such as the term “pre-diabetes” [23, 24, 26]. Further, this term aids in the important distinction that overweight (BMI ≥ 25) focuses on total weight and therefore cannot be used as a synonym for pre-obesity as it does not reflect the dysregulation of adipose tissue.

Within theme 3, obesity prevention, we highlight the critical difference between health promotion and primary prevention. Implementing these concepts into the obesity taxonomy addresses the misconception that health promotion, which is delivered to the general public and not only those who might be at risk of obesity, is the same thing as obesity primary prevention which targets risk factors for obesity to reduce the prevalence of obesity. As such, phrases such as ‘eat less, move more’ and “live a healthy lifestyle“ are often is seen as being primary prevention of obesity, but these are actually health promotion and applicable to all dietary-related chronic diseases. In a recent survey of 5623 respondents across four countries, 79% and 80% of people reported believing that obesity could be prevented and cured by adhering to a healthy lifestyle, reflecting a lack of understanding of obesity as an adiposity-based chronic disease [27]. Although a healthy lifestyle is beneficial for everyone, this ignores the scientific evidence of obesity being a neurometabolic disease that varies in its severity, thus requiring different levels of treatment that extend beyond just lifestyle changes [28].

Theme 4, screening and early diagnosis of obesity, and theme 5, treatment and management, addresses the importance of the continuum of care used in chronic diseases and aligns the language of obesity with the language and frameworks used in other policy prioritised NCDs [23, 24]. These themes focus on highlighting the importance of an obesity care cascade, where in the first step, populations are screened for obesity. When an individual is detected with signs of having obesity, the individual should be referred for an examination as to enable the early diagnosis of obesity. The early diagnosis of obesity refers to detecting an individual who is living with obesity as early as possible based on signs of this disease. Individuals who are diagnosed as living with obesity should get treatment where different actions are taken by individuals, families, communities, and healthcare professionals, to promote, maintain, control, and restore health in people living with obesity.

The obesity taxonomy underscores the imperative for a structured obesity vocabulary, given the lack of understanding about the scientific evidence of obesity as an adiposity-based chronic disease which is characterised by the function, total amount, and distribution of adipose tissue among various stakeholders involved in shaping and implementing health service delivery policies and practices and related regulatory implications. The confusion arises from the ambiguity surrounding whether obesity is viewed as an adiposity-based chronic disease and the prevalent use of terms like weight, weight management, overweight and BMI. This confusion permeates throughout research agendas, treatment protocols and policies, causing significant disruptions, particularly in health service delivery. As a result, policymakers are left with an insufficient understanding of what aspects they should legislate. The obesity taxonomy, derived through a rigorous three-round Delphi exercise, forms the basis for a common, precise, and scientifically accurate language related to obesity. The resulting taxonomy is relevant for educating as well as increasing awareness concerning obesity by delivering a tangible and searchable structured online lexicon that can be used by policymakers, health practitioners, patients, and health advocates. The taxonomy provides obesity terminology, that is consistent with other non-communicable diseases, is broken down into specific definitions, scope and context and is scientifically accurate. By establishing this clear framework, in a healthcare setting the taxonomy can facilitate clear communication among health care professionals and with health system users and may support collaboration and mutual understanding between health care professionals and policy makers. The use of appropriate language in the correct context is imperative in science and societal discussion in order to progress and deliver value for patients. Expert stakeholders consider that changes to language used at the point of care can support improved outcomes for both people living with obesity and for the functioning of the healthcare system itself [7].

This Delphi study had several strengths. Expert knowledge was gathered from a wide range of different stakeholders across different countries within the WHO Europe region. We reached experts from all relevant stakeholder groups across 30 different countries and sample size was more than four times the recommended lower limit threshold of 12 for a Delphi study. Given the extensive global reach of this field, the Delphi consensus technique, which can be executed online, was the fitting approach to gather these diverse viewpoints. Alongside identifying areas of consensus, the study highlighted areas where the field has some uncertainty, such as the theme of the definition of obesity, and the theme of causes, onset, and progression. These aspects might warrant further exploration and a broader interdisciplinary approach to effectively resolve these uncertainties. We used a panel of 14 experts specialising in obesity (the sounding board) to confirm the appropriateness of the Delphi methodology and to discuss the outcomes of the Delphi survey to verify the findings. Another notable strength of the study was the predetermined stringent definition of consensus, set a priori as agreement rates of 75% or higher for ratings 7–10, and agreement rates of less than 15% for ratings 0–3 [25] and no relevant comments based on a synthesis of free text responses. It is both a strength and a limitation that we accommodated free text responses. This invaluable input from the Delphi panellists shaped and improved the definitions, however, there remains the subjective nature of interpretation of the free text responses. Nevertheless, both core team members had to reach agreement in their interpretation, thus minimising the effects of subjectivity. While a strength of the study was its ability to access a network of colleagues in the field of obesity research, this may have introduced some response bias, as potentially only like-minded individuals participated in this study. However, the broad representation of stakeholders from different professional groups and countries counters this, but nonetheless we cannot preclude that the responses reflect a certain group of individuals. In this study, Delphi participants were invited to every round independent of response to previous rounds. However, an analysis of a previous Delphi study indicated that this invitation approach had no impact on the final results of this type of survey [29]. Another strength of our study is that, during rounds two and three, the group’s collective response to each statement and comments were presented to enable adequate reflection on group responses. This approach is considered optimal for achieving consensus [30]. Furthermore the statements were exclusively presented in English to the Delphi participants. We cannot preclude individuals less proficient in English may not have participated, thus resulting in less representation of views from non-English speaking populations. In addition, the distribution of stakeholders and countries may not have been evenly distributed across the three rounds of Delphi. There were lower rates of participation by individuals with the lived experience of obesity and individuals from Eastern European countries were observed across all three rounds of the Delphi process. Nonetheless, health care professionals and researchers were well-represented, as stakeholders from health literacy and other groups who can benefit from using the taxonomy were included.

Conclusion

The obesity taxonomy, derived through a rigorous three-round Delphi exercise, forms the basis for a common, precise, and scientifically accurate language related to obesity. The taxonomy initiative harmonises the language used in other policy prioritised NCDs and is relevant for all stakeholder groups involved. The obesity taxonomy delivers a tangible and searchable structured online lexicon for policymakers, health care professionals, people living with obesity, researchers, and health system users to use as the basis of discussions for their work and interactions and will align and educate stakeholders on the language of chronic disease through the lens of obesity.

Data availability

Information concerning data availability can be found in Appendix Table 4.

References

Hull M. Medical language proficiency: a discussion of interprofessional language competencies and potential for patient risk. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;54:158–72.

Meuter RF, Gallois C, Segalowitz NS, Ryder AG, Hocking J. Overcoming language barriers in healthcare: a protocol for investigating safe and effective communication when patients or clinicians use a second language. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:371.

Speakman JR, O’Rahilly S. Fat: an evolving issue. Dis Model Mech. 2012;5:569–73.

Lobstein T, Neveux M. World obesity atlas 2022. Ludgate House, 107-111 Fleet Street, London. World Obesity Federation; 2022.

Auckburally S, Davies E, Logue J. The use of effective language and communication in the management of obesity: the challenge for healthcare professionals. Curr Obes Rep. 2021;10:274–81.

Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity stigma: important considerations for public health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1019–28.

Albury C, Strain WD, Brocq SL, Logue J, Lloyd C, Tahrani A. The importance of language in engagement between health-care professionals and people living with obesity: a joint consensus statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:447–55.

Puhl R, Suh Y. Health consequences of weight stigma: implications for obesity prevention and treatment. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4:182–90.

Tomiyama AJ, Carr D, Granberg EM, Major B, Robinson E, Sutin AR, et al. How and why weight stigma drives the obesity ‘epidemic’ and harms health. BMC Med. 2018;16:123.

Rubino F, Puhl RM, Cummings DE, Eckel RH, Ryan DH, Mechanick JI, et al. Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nat Med. 2020;26:485–97.

Lim S, Oh B, Lee SH, Kim YH, Ha Y, Kang JH. Perceptions, attitudes, behaviors, and barriers to effective obesity care in South Korea: results from the ACTION-IO study. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2020;29:133–42.

Caterson ID, Alfadda AA, Auerbach P, Coutinho W, Cuevas A, Dicker D, et al. Gaps to bridge: misalignment between perception, reality and actions in obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:1914–24.

Tuzzio L, Berry AL, Gleason K, Barrow J, Bayliss EA, Gray MF, et al. Aligning care with the personal values of patients with complex care needs. Health Serv Res. 2021;56:1037–44.

Erixon F. ECIPE Policy Brief No. 7. 2016.

Bernell S, Howard SW. Use your words carefully: what is a chronic disease? Front Public Health. 2016;4:159.

Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:376–80.

Byrne S, Wake M, Blumberg D, Dibley M. Identifying priority areas for longitudinal research in childhood obesity: Delphi technique survey. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2008;3:120–2.

Faulkner GE, Grootendorst P, Nguyen VH, Andreyeva T, Arbour-Nicitopoulos K, Auld MC, et al. Economic instruments for obesity prevention: results of a scoping review and modified Delphi survey. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:109.

Frühbeck G, Busetto L, Dicker D, Yumuk V, Goossens GH, Hebebrand J, et al. The ABCD of obesity: an EASO position statement on a diagnostic term with clinical and scientific implications. Obes Facts. 2019;12:131–6.

Luli M, Yeo G, Farrell E, Ogden J, Parretti H, Frew E, et al. The implications of defining obesity as a disease: a report from the Association for the Study of Obesity 2021 annual conference. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;58:101962.

Yumuk V, Tsigos C, Fried M, Schindler K, Busetto L, Micic D, et al. European guidelines for obesity management in adults. Obes Facts. 2015;8:402–24.

Jepsen CH, Bowman-Busato J, Allvin T, Arthurs N, Goossens GH, Govers E, et al. Achieving consensus on the language of obesity: a modified Delphi study. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;62:102061.

Union E, editor. Healthier together: EU non-communicable diseases initiative. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2022.

World Health Organization. Health service delivery framework for prevention and management of obesity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023.

Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, Brook RH. Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:979–83.

Banasiak K, Cleary D, Bajurny V, Barbieri P, Nagpal S, Sorensen M, et al. Language matters—a diabetes Canada consensus statement. Can J Diabetes. 2020;44:370–3.

O’Keeffe M, Flint SW, Watts K, Rubino F. Knowledge gaps and weight stigma shape attitudes toward obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:363–5.

Heath L, Jebb SA, Aveyard P, Piernas C. Obesity, metabolic risk and adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviours: prospective cohort study in the UK Biobank. BMC Med. 2022;20:65.

Boel A, Navarro-Compán V, Landewé R, van der Heijde D. Two different invitation approaches for consecutive rounds of a Delphi survey led to comparable final outcome. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;129:31–9.

Iqbal S, Pipon-Young L. The Delphi method. Psychologist. 2009;22:598–601.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the sounding board members who served as scientific advisors for this project: Alina Constantin, Prof. Dr. Clare Llewellyn, Prof. Dr. Diane Levin-Zamir, Prof. Dr. Feray Akbaš, Prof. Dr. Kirsi Pietiläinen, Prof. Dr. Konstantinos Makris, Kristine Sørensen, Prof. Dr. Luca Busetto, Prof. Dr. Maria M. Malagon, Prof. Dr. Maria Hassapidou, Morgan Salmon, Prof. Dr. Robert Heine, Prof. Dr. Sarah Cuschieri, and Prof. Dr. Sylvain Sebert. The advisor’s contributions were on a voluntary basis and did not receive any payment for their involvement in this study.

Funding

This project has been funded by the European Association for the Study of Obesity. We acknowledge additional financial support from Eli Lilly and Company given to the European Association for the Study of Obesity. This funding source had no role in the design of this study and did not have any role during its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, preparation of the manuscript or the decision to submit results for publication. One member of the sounding board is affiliated with Eli Lilly and Company, yet it can be affirmed that this individual’s opinions held no greater influence than that of the other board members.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jacqueline Bowman-Busato: conceptualisation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, validation, visualisation, writing original draft, writing review & editing. Lucas Schreurs: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, project administration, methodology, resources, validation, visualisation, writing original draft, writing review & editing. Jason C. G. Halford: conceptualisation, investigation, project administration, resources, validation, visualisation, writing original draft, writing review & editing. Volkan Yumuk: conceptualisation, investigation, project administration, resources, validation, visualisation, writing original draft, writing review & editing. Grace O’Malley: conceptualisation, investigation, project administration, resources, validation, visualisation, writing original draft, writing review & editing. Euan Woodward: conceptualisation, investigation, project administration, resources, validation, visualisation, writing original draft, writing review & editing. Diederik De Cock: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, methodology, resources, validation, visualisation, writing original draft, writing review & editing. Jennifer L. Baker: conceptualisation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, validation, visualisation, writing original draft, writing review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JBB has no conflicts of interest related to this work, LS has no conflicts of interests related to this work. JCGH has no conflicts of interest related to this work and declares funding for consultancy and speaking from Novo Nordisk and Boehringer Ingelheim respectively. All monies are paid to the University of Leeds to support research. VY has no conflicts of interest related to this work and declares funding Eli Lilly, for providing single advisor activity and Novo Nordisk, for providing educational sessions or attending advisory boards. GOM has no conflicts of interest related to this work. EW has no conflicts of interest related to this work. DDC has no conflicts of interests related to this work. JLB has no conflicts of interest related to this work, and declares having received consulting fees from Novo Nordisk A/S.

Ethical approval

According to the Free University of Brussels (VUB) regulations where the study was conducted, ethics committee approval was not required for this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bowman-Busato, J., Schreurs, L., Halford, J.C.G. et al. Providing a common language for obesity: the European Association for the Study of Obesity obesity taxonomy. Int J Obes 49, 182–191 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01565-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01565-9

This article is cited by

-

Eating disorders across population groups with different weight status in Belgium: evidence for an integrative preventative approach

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

The non-linear relationships between fat mass and lean body mass with arthritis

Lipids in Health and Disease (2025)

-

Obesity competencies for healthcare professionals: a scoping review

BMC Medical Education (2025)

-

Systematic literature review on the awareness of obesity in adults and children living with obesity, the general public and healthcare professionals

International Journal of Obesity (2025)

-

Editorial on obesity: a 100-year journey—the past, present and future

International Journal of Obesity (2025)