Abstract

Background

This study aims to explore the association of childhood maltreatment with obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D) in adulthood, and whether obesity is a mediator of the latter.

Methods

In a retrospective cohort study using UK Biobank data, participants recalled childhood maltreatment. Linear regression, logistic regression, and Cox proportional hazard models were used to investigate the associations with body mass index (BMI), obesity, and T2D, adjusted for sociodemographic factors. Decomposition analysis was used to examine the extent to which T2D excess risk was attributed to BMI.

Results

Of the 153,601 participants who completed the childhood maltreatment questions, one-third reported some form of maltreatment. Prevalence of adult obesity and incidence of T2D were higher with the number of reported childhood maltreatment types. People who reported ≥3 types of childhood maltreatment were at higher risk of obesity (OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.47–1.63) and incident T2D (HR 1.65, 95% CI 1.52–1.80). Excess T2D risk among those reporting maltreatment could be reduced by 39% if their BMI was comparable to participants who had not been maltreated, assuming causality.

Conclusions

People who recalled maltreatment in childhood are at higher risk of T2D in adulthood, partly due to obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity has emerged as a global epidemic, contributing significantly to the disease burden in both developed and developing nations [1]. Over the past two decades, the prevalence of obesity has risen dramatically, doubling in adults and children, and tripling in adolescents [2]. Excessive body fat accumulation poses immediate health risks and can lead to severe long-term consequences. These include the development of type 2 diabetes (T2D), coronary heart disease, osteoarthritis, and certain cancers [3].

In the United Kingdom, obesity contributes to approximately 8.7% of all deaths, resulting in an estimated 9000 premature fatalities annually [4]. Due to its increasing prevalence and substantial economic and health-related costs, obesity is now recognised as a critical public health issue [5]. Obesity significantly impacts physical health, mental well-being, and health-related quality of life. It imposes considerable direct and indirect costs on both individuals and healthcare systems [6]. Notably, T2D stands out as one of the most financially burdensome public health consequences of obesity, especially in industrialised nations, as well as having a significantly negative impact on individuals health [7].

The complex determinants of obesity include individual factors, including genetics [8], and multifaceted interactions with our environment. These environmental factors encompass aspects like food supply, dietary behaviours, family-work dynamics, socioeconomic status, urban design, and public policies [6]. Importantly, a growing body of evidence [9] suggests a link between adverse childhood experiences and an increased risk of obesity and T2D in adulthood [10, 11]. Among these adverse experiences, childhood maltreatment, which includes abuse and neglect, is particularly severe. Each year 4–16% of children are physically abused and 10% are neglected or psychologically abused in high-income countries [12].

A recently proposed model for obesity development places focus on the impact of social adversity within the family, including abuse and maltreatment [9]. However, the associations between childhood maltreatment and T2D outcomes remain underexplored, with only limited research investigating this connection [13]. Methods differ for measuring childhood maltreatment, some focusing on the impact of specific maltreatment subtypes, rather than the potential cumulative impact. In addition, T2D is often a self-reported outcome in these studies [14, 15] increasing risk of information bias. Potential mediators between childhood maltreatment and T2D already explored in the literature, include mental ill-health such as depression [16], and altered neuroendocrine stress responsivity, caused by chronic trauma and stress [17, 18].

This study aims to investigate the associations of childhood maltreatment (which includes sexual abuse, physical, verbal, and emotional abuse, as well as emotional neglect) with obesity prevalence and risk of T2D in adulthood within the UK population. Crucially, this study will also examine whether obesity lies on the causal pathway between childhood maltreatment and T2D.

Methods

Study design and participants

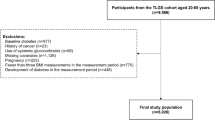

This retrospective cohort study utilised data from UK Biobank (baseline assessment in 2007–2010), with participants recalling child maltreatment in an online mental health questionnaire in 2017. Follow-up for type 2 diabetes incidence started from the completion of mental health questionnaire in 2017 till the end of 2022.

The UK Biobank is a large biomedical database established in 2007, with various follow-up (including mental health questions in 2017), and linkage to clinical data (e.g. hospital admission and death). The recruitment phase and baseline assessments spanned from 2007 to 2010 and enroled 502,506 participants aged 37–73 years from the general population who attended assessment centres across England, Scotland, and Wales. At the baseline assessment, participants engaged in a structured assessment process, which included the completion of a self-administered touch-screen questionnaire, face-to-face interviews, and physical measurements such as height, weight, and blood pressure, administered by trained personnel. Self-reported information included ethnicity, educational attainment, sleep duration, television viewing time, smoking status, and alcohol consumption. Height and weight assessments were conducted by trained staff, with height measured to the nearest centimetre using a Seca 202 stadiometer and weight recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg using a Tanita BC-418 body composition analyzer. Physical activity levels were self-reported using the validated International Physical Activity Questionnaire [19].

All participants provided written informed consent before enrolment in the UK Biobank, which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The UK Biobank study, and the sharing of anonymized data with the research community, was approved by the North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (REC reference: 12/NW/03820). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Childhood maltreatment

The assessment of childhood maltreatment was carried out through a web-based questionnaire in August 2017 [20]. The participants aged 45–80 (median 64) years when they completed the questionnaire. A total of 339,229 participants who had provided an email address were invited to participate, with approximately half of them (n = 157,348) completing the online questionnaire. The questionnaire covered various aspects of their thoughts and emotions, encompassing experiences from their formative years, such as instances of childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse by a family member, feelings of love during childhood, perceptions of being disliked by a family member during childhood, and whether they had someone available to accompany them to medical appointments when necessary.

Respondents who completed the questionnaire generally were younger, more likely to be female and of white ethnicity, and exhibited healthier lifestyles when compared to non-respondents [21]. The web-based questionnaire featured the Childhood Trauma Screener (CTS) [22]. This screener was derived from a condensed version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) [23]. The questionnaire did not specify the age at which maltreatment occurred but used general description (‘when I was growing up’) to ascertain childhood maltreatment. It consists of a 5-point Likert scale for each of five types of child maltreatment, physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and sexual abuse. The CTQ is a widely used instrument for measuring reported child maltreatment and has been validated against actual records of abuse and neglect [24]. For this study we used validated cut-off values to identify participants to have specific types of maltreatment [22]. Participants were then categorised according to the number of types of child maltreatment experienced (0, 1, 2 or ≥3) as the primary exposure. This approach allowed us to analyse the impact of the multiplicity of childhood maltreatment that individuals encountered. In addition, childhood maltreatment was also characterised as binary (0 vs. ≥1) and ordinal (exact number of types) variables in analyses.

Outcome ascertainment

Body mass index (BMI) and obesity were both computed from participants’ height and weight recorded at baseline assessment (2007–2010). For BMI, weight was divided by height squared. The study’s main outcome – obesity - was defined using the WHO BMI category ( ≥ 30.0 kg/m²).

T2D was measured over follow up by individually linking UK Biobank assessment data with death, hospital, and primary care records which included ICD-10 codes (E11) or READ codes. Details are published elsewhere [25]. The start of follow-up was the date of the first assessment visit. Hospital admission data and mortality data were available until October, August, and May 2022 for England, Scotland, and Wales respectively. There were 6289 participants who developed T2D prior to the start of follow-up and were excluded in the T2D analysis.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive characteristics for the cohort, by number of child maltreatment types, were firstly summarised. For continuous variables the mean and standard deviation (SD) was presented. Linear and logistic regression analyses were then used to examine the associations between child maltreatment and BMI and obesity respectively. For the outcome of BMI, the results were expressed as unstandardised coefficients (Beta) which represented the difference in BMI associated with each additional type of childhood maltreatment. We employed a logistic regression model to investigate the binary outcome of obesity. The odds ratios (OR) were calculated to determine the odds of having obesity for individuals who experienced specific types of childhood maltreatment compared to those who experienced none. To explore the relationship between childhood maltreatment and incident T2D, we used Cox proportional hazard models which consider both the event status and time-to-event. Hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. Our analyses adjusted for potential confounding variables, including age at baseline assessment, sex, ethnicity, deprivation index, and education level. We also additionally adjusted for the potential mediators, depression, and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), in a sensitivity analysis to determine if the associations were independent of clinical mental health conditions.

We then investigated the independent associations of different types of childhood maltreatment, including physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect, with the outcomes. These childhood maltreatment variables were mutually adjusted in the models.

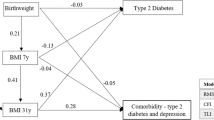

Lastly, we conducted a four-way decomposition analysis to examine the causal pathway from maltreatment, via BMI, to T2D. The formal definitions and formulas could be found in previous literature [26]. The analysis decomposes the excess risk of T2D in people who reported maltreatment into four components: pure mediation via BMI, interacted mediation via BMI, pure interaction with BMI, and unrelated to BMI. The primary metrics of interest are the proportion attributed to interaction and mediation (including interacted mediation and pure mediation). These two combined indicates the excess risk due to maltreatment that could be hypothetically eliminated if BMI could be equivalised. In addition to the sociodemographic covariates, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis to adjust for lifestyle factors (smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep duration) as exposure induced confounders (i.e. confounding between mediator and outcome originated from the exposure). The causal diagram for this is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

All analyses were conducted using R Statistical Software (version 4.3.1) with packages survival and CMAverse.

Results

This study included a cohort of 153,601 UK Biobank participants, with a mean (SD) age of 55.34 (7.74) years, and comprising 59.75% women at baseline. Among these individuals, one-third (n = 51,181) reported experiencing at least one form of child maltreatment, with 12.95% reporting multiple types. People who reported higher numbers of maltreatment types were younger, more likely to be female, less likely to be of white ethnicity, reported less physical activity, consumed more alcohol, spent more time watching television, and were less likely to be never smokers (Table 1). Of all types of maltreatments, emotional neglect was most prevalent (22.1%; Supplementary Table 1), followed by emotional abuse (9.3%), and sexual abuse (8.8%). Among people who reported multiple maltreatments, emotional neglect (88.0%) was also the most prevalent, followed by emotional abuse (58.8%) and physical abuse (47.1%).

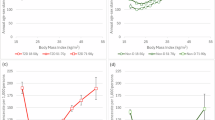

A higher number of maltreatments were associated with a higher odds of obesity (Table 2). Participants who reported more than three types of childhood maltreatment demonstrated the highest odds of obesity in adulthood (OR 1.55 [95% CI 1.47–1.63], P < 0.001), followed by those participants who reported two experiences (OR 1.31 [95% CI 1.25–1.37], P < 0.001) and one type of maltreatment (OR 1.12 [95% CI 1.08–1.16], P < 0.001) compared to those who did not report maltreatment. The risk of developing T2D in adulthood was also associated significantly with the number of types of childhood maltreatment ( ≥ 3 types: HR 1.65 [95% CI 1.52–1.80], P < 0.001; 2 types: HR 1.37 [95% CI 1.27–1.47], P < 0.001) (Table 2). These associations remained when the model was adjusted for depression and PTSD ( ≥ 3 types and obesity: OR 1.27 [95% CI 1.20–1.34], P < 0.001; ≥3 types and T2D: HR 1.28 [95% CI 1.16–1.48], P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 2).

Examining specific maltreatment types, participants who reported physical abuse (beta 0.94 [95% CI 0.84–1.0], P < 0.001) and physical neglect (beta 0.55 [95% CI 0.45–0.65], P < 0.001) during childhood exhibited a higher BMI (Table 3). The associations with obesity were larger for physical abuse (OR 1.42 [95% CI 1.36–1.49], P < 0.001) and neglect (OR 1.23 [95% CI 1.16–1.29], P < 0.001) than for sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect. Regarding T2D, participants who reported physical neglect (HR 1.45 [95% CI 1.33–1.57], P < 0.001), physical abuse (HR 1.36 [95% CI 1.26–1.47], P < 0.001), or emotional neglect (HR 1.10 [95% CI 1.04–1.17], P < 0.001) in childhood were at higher risk of T2D in adulthood.

Results of the four-way decomposition analysis is shown in Table 4. Consistent with the regression analyses, each additional type of childhood maltreatment was associated with 17% higher T2D risk (HR = 1.17) even after adjusted for exposure-induced confounders in Model 2. Of the excess risk, 8.4% was attributed to the interaction with BMI and 31.1% was attributed to mediation via BMI. Totally, 39.4% of the excess risk due to childhood maltreatment could be attributed to higher BMI.

Discussion

The findings presented in this study highlight people who have reported childhood maltreatment were more likely to have obesity and develop T2D in later adulthood. The analysis also shows that a considerable portion, almost 40%, of the association between childhood maltreatment and adult T2D, is mediated through obesity.

Comparison with existing literature

The findings of this study largely corroborated with existing literature [27] but also meaningfully extend our understanding on the relationship. A prospective longitudinal study investigating the influence of various childhood adversities on the development of obesity and T2D in adulthood showed that stressful emotional experiences during childhood were associated with an elevated risk of obesity and, consequently, increased susceptibility to T2D [28]. A UK-based cross-sectional study investigated the associations between the number of ACEs and self-reported T2D, showing a steep gradient in risk of T2D with 4 or more ACEs, as well as similar results with related conditions including cardiovascular disease and stroke [29].

There have been more studies on childhood maltreatment and obesity in childhood or adolescence, which showed complex differential associations by sex [30] and by types of maltreatment [31]. The literature on adulthood obesity is also heterogeneous. A retrospective cohort study explored reports of different forms of abuse, encompassing sexual, verbal, physical abuse, as well as the fear of physical abuse, and their associations with adult obesity. Associations were reported between all forms of abuse and higher body weight in adulthood. Consistent with our findings, physical abuse emerged as the most important contributor to a higher body weight and adult obesity [32]. Interestingly, the US CARDIA study has found no association between exposure to abuse in childhood and obesity [33]. The inconsistency could be, in part, be attributed to the measurements. The abuse questions of the CARDIA study focused on only physical and psychological abuse, while this study included also neglect and sexual abuse. That study also only focused on incidence of obesity between 18–30 years and 48–60 years. while this study examined prevalence at 37–70 years. There is, however, a small longitudinal study that also showed association between early life trauma and development of adult obesity [34]. Importantly, none of these studies explicitly modelled the mediation pathways via BMI, which provides useful insights in developing relevant leverage points for intervention.

Causal pathways

In this study we demonstrated a considerable mediating role of BMI between childhood maltreatment and T2D. Several studies have explored the mechanism linking childhood maltreatment and obesity. A sequence of models that tested mediation effects indicated that stress-induced overeating among respondents with problematic histories of violence explained, in part, their higher risk of adult obesity [35]. Other studies [17] suggest depression as a potential mediator, after demonstrating that the association between childhood maltreatment and T2D was stronger among those with depression [16]. Interestingly, our study has shown that even when clinical depression was adjusted, the association between maltreatment and T2D remained.

Limitations

The study had some limitations. The study relied on self-report of childhood maltreatment. This raises the possibility of recall bias, and underreporting given the sensitivity of the topic. However, abuse is often also underestimated by objective sources due to underreporting. Participants who had already developed T2D prior to the start of the study, were excluded. A recent study has shown maltreatment to affect T2D earlier in life, with participants aged 16 years at baseline [17]. Owing to the timing of the obesity measurement, it was necessary to exclude those participants. It should be noted that our studies finding could therefore be subject to truncation bias, leading to more conservative effect sizes. The study sample was obtained from UK Biobank, which is not representative of the general population, including a relatively healthy and more socioeconomically advantaged group. Nonetheless previous studies have shown that findings from UK Biobank were comparable to population representative studies [36]. Although the study takes into account several potential confounding variables, it may not consider all relevant factors that could influence the association between childhood maltreatment and obesity and T2DM, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [37]. Therefore, as with all observational studies, causality cannot be inferred even though it was assumed in the mediation analysis. Importantly, there was no information on the source of abuse, intensity, duration, and timing, as well as the onset of obesity, all of which could help further delineate the associations of childhood maltreatment with obesity and T2D better. Future studies should investigate these.

Implications

This study contributes to the increasing evidence linking childhood maltreatment to adverse metabolic health outcomes in adulthood. It highlights the need for a life-course approach to public health that considers early childhood experiences and their potential impact on health in adulthood [9]. Current literature on interventions to improve health outcomes is very limited with respect to neurobiological/physical outcomes, with most focus being on mitigating psychological harms [38]. Future research should cover a wide range of dimensions, from understanding the underlying mechanisms that include both environmental exposures and individual factors, to developing effective prevention and intervention strategies [39], including addressing neurobiological/physical health outcomes. Research should also ensure to include both environmental exposures and individual factors contributing to obesity, including neurodevelopment and appetite. In addition, research should be integrated into the development of health policies and strategies aimed at preventing childhood maltreatment and its long-term consequences. This may include addressing social determinants, strengthening access to mental health and domestic abuse services, and promoting safe, stable, and supportive environments and relationships for children and families.

Conclusions

Childhood maltreatment recall, especially physical abuse and neglect, was associated with obesity and T2D in adulthood. Prevention of childhood maltreatment could be an important element in managing obesity and T2D. Among people who were maltreated, obesity is a modifiable mediator of the association with T2D and therefore a potential intervention target.

Summary table

What is already known about this subject?

-

Obesity is known to be a multifactorial condition, where risk is not fully explained by established risk factors (e.g. genetics, lifestyle)

-

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) has postulated early life factors could explain obesity

-

Preliminary evidence has shown associations of early life adversity with obesity and type 2 diabetes.

What are the new findings in your manuscript?

-

Prevalence of adult obesity and incidence of T2D were higher in people who reported more childhood maltreatment types.

-

People who reported ≥3 types of childhood maltreatment were at higher odds of obesity (OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.47–1.63) and incident T2D (HR 1.65, 95% CI 1.52–1.80).

-

Excess T2D risk among those reporting maltreatment could be reduced by 39% if their BMI was comparable to participants who had not been maltreated, assuming causality.

How might your results change the direction of research or the focus of clinical practice?

-

Prevention of childhood maltreatment or intervention of people who had maltreatment could reduce risks of obesity and type 2 diabetes.

-

Adulthood obesity could be a consequence of early life adversity that leads to diseases later in life.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study were obtained from the UK Biobank, and these data are subject to certain restrictions regarding their availability. They were used under license for the specific purpose of the current study, which means that they are not publicly available for unrestricted use. However, data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the UK Biobank.

References

Dai H, Alsalhe TA, Chalghaf N, Riccò M, Bragazzi NL, Wu J. The global burden of disease attributable to high body mass index in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. PLoS Med. 2020;17:e1003198.

Bassett MT, Perl S. Obesity: the public health challenge of our time. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1477.

Agha M, Agha R. The rising prevalence of obesity: part A: impact on public health. Int J Surg Oncol. 2017;2:e17.

Kelly C, Pashayan N, Munisamy S, Powles JW. Mortality attributable to excess adiposity in England and Wales in 2003 and 2015: explorations with a spreadsheet implementation of the Comparative Risk Assessment methodology. Popul Health Metr. 2009;7:11.

Visscher TL, Seidell JC. The public health impact of obesity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:355–75.

Dixon JB. The effect of obesity on health outcomes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316:104–8.

Wolf AM, Colditz GA. Current estimates of the economic cost of obesity in the United States. Obes Res. 1998;6:97–106.

Elks CE, Den Hoed M, Zhao JH, Sharp SJ, Wareham NJ, Loos RJ, et al. Variability in the heritability of body mass index: a systematic review and meta-regression. Front Endocrinol. 2012;3:29.

Hemmingsson E, Nowicka P, Ulijaszek S, Sørensen TI. The social origins of obesity within and across generations. Obes Rev. 2023;24:e13514.

Hemmingsson E, Johansson K, Reynisdottir S. Effects of childhood abuse on adult obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2014;15:882–93.

Elsenburg LK, Bengtsson J, Rieckmann A, Rod NH. Childhood adversity and risk of type 2 diabetes in early adulthood: results from a population-wide cohort study of 1.2 million individuals. Diabetologia. 2023;66:1218–1222.

Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. lancet. 2009;373:68–81.

Davis WS. Association Between Psychological Trauma From Assault in Childhood and Metabolic Syndrome. 2015.

Shields ME, Hovdestad WE, Pelletier C, Dykxhoorn JL, O’Donnell SC, Tonmyr L. Childhood maltreatment as a risk factor for diabetes: findings from a population-based survey of Canadian adults. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1–12.

Clemens V, Huber-Lang M, Plener PL, Brähler E, Brown RC, Fegert JM. Association of child maltreatment subtypes and long-term physical health in a German representative sample. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2018;9:1510278.

Atasoy S, Johar H, Fleischer T, Beutel M, Binder H, Braehler E, et al. Depression mediates the association between childhood emotional abuse and the onset of type 2 diabetes: findings from German multi-cohort prospective studies. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:825678.

Deschênes SS, Graham E, Kivimäki M, Schmitz N. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of diabetes: examining the roles of depressive symptoms and cardiometabolic dysregulations in the Whitehall II cohort study. Diab Care. 2018;41:2120–6.

Berens AE, Jensen SK, Nelson CA. Biological embedding of childhood adversity: from physiological mechanisms to clinical implications. BMC Med. 2017;15:1–12.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–95.

Davis KAS, Coleman JRI, Adams M, Allen N, Breen G, Cullen B, et al. Mental health in UK Biobank: development, implementation and results from an online questionnaire completed by 157 366 participants. BJPsych Open. 2018;4:83–90.

Ho FK, Celis-Morales C, Gray SR, Petermann-Rocha F, Lyall D, Mackay D, et al. Child maltreatment and cardiovascular disease: quantifying mediation pathways using UK Biobank. BMC Med. 2020;18:143.

Glaesmer H, Schulz A, Häuser W, Freyberger HJ, Brähler E, Grabe HJ. The childhood trauma screener (CTS) - development and validation of cut-off-scores for classificatory diagnostics. Psychiatr Prax. 2013;40:220–6.

Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, Perkins C, Lowey H. National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC Med. 2014;12:72.

Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:340–8.

Boonpor J, Parra-Soto S, Petermann-Rocha F, Ho FK, Celis-Morales C, Gray SR. Combined association of walking pace and grip strength with incident type 2 diabetes. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2022;32:1356–65.

VanderWeele TJ. A unification of mediation and interaction: a 4-way decomposition. Epidemiology. 2014;25:749–61.

Zara S, Brähler E, Sachser C, Fegert JM, Häuser W, Krakau L, et al. Associations of different types of child maltreatment and diabetes in adulthood–the mediating effect of personality functioning: Findings from a population-based representative German sample. Ann Epidemiol. 2023;78:47–53.

Thomas C, Hyppönen E, Power C. Obesity and type 2 diabetes risk in midadult life: the role of childhood adversity. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1240–9.

Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, Hardcastle K, Perkins C, Lowey H. Measuring mortality and the burden of adult disease associated with adverse childhood experiences in England: a national survey. J Public Health. 2015;37:445–54.

Isohookana R, Marttunen M, Hakko H, Riipinen P, Riala K. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on obesity and unhealthy weight control behaviors among adolescents. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;71:17–24.

Schiff M, Helton J, Fu J. Adverse childhood experiences and obesity over time. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24:3205–9.

Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Anda RF, Dietz WH, Felitti V. Body weight and obesity in adults and self-reported abuse in childhood. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:1075–82.

Aguayo L, Chirinos DA, Heard‐Garris N, Wong M, Davis MM, Merkin SS, et al. Association of exposure to abuse, nurture, and household organization in childhood with 4 cardiovascular disease risks factors among participants in the CARDIA study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e023244.

D’Argenio A, Mazzi C, Pecchioli L, Di Lorenzo G, Siracusano A, Troisi A. Early trauma and adult obesity: is psychological dysfunction the mediating mechanism? Physiol Behav. 2009;98:543–6.

Greenfield EA, Marks NF. Violence from parents in childhood and obesity in adulthood: using food in response to stress as a mediator of risk. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:791–8.

Batty GD, Gale CR, Kivimäki M, Deary IJ, Bell S. Comparison of risk factor associations in UK Biobank against representative, general population based studies with conventional response rates: prospective cohort study and individual participant meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;368:m131.

Ouyang L, Fang X, Mercy J, Perou R, Grosse SD. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and child maltreatment: a population-based study. J Pediatrics. 2008;153:851–6.

Lorenc T, Lester S, Sutcliffe K, Stansfield C, Thomas J. Interventions to support people exposed to adverse childhood experiences: systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–10.

Mason SM, Austin SB, Bakalar JL, Boynton-Jarrett R, Field AE, Gooding HC, et al. Child maltreatment’s heavy toll: The need for trauma-informed obesity prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:646–9.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted under UK Biobank project 71392. UK Biobank was established by the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council, Department of Health, Scottish Government and Northwest Regional Development Agency. UK Biobank has also had funding from the Welsh Assembly Government and the British Heart Foundation. Shinya Nakada was funded by the MRC Precision Medicine Training Grant (MR/N013166/1-LGH/MS/MED25).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TN designed the study, analysed the data, and wrote the first draft of the paper. FKH designed the study, analysed the data, and critically revised the paper. DM designed the study, interpreted the data, and critically revised the paper. EW, IK, JB, ZZ, SN, IDR, CCM, JW, NHR, JPP, HM, and TH interpreted the data and critically revised the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nadaraia, T., Whittaker, E., Kenyon, I. et al. Childhood maltreatment, adulthood obesity and incident type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study using UK Biobank. Int J Obes 49, 140–146 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01652-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01652-x