Abstract

Background

Glucosylsphingosine (Lyso-GL-1), a glycosphingolipid formed by glucosylceramide hydrolysis, is known to be increased in Gaucher disease. Recently, increased ceramides and sphingolipids have been implicated in obesity, insulin resistance, and atherogenesis. However, limited data exists on serum Lyso-GL-1 level in children with obesity and its relation with insulin resistance, lipid dysfunction, and atherogenesis. Hence, this study aimed to assess Lyso-GL-1 level among children with obesity and correlate it with biomarkers of insulin resistance and atherogenic index of plasma (AIP).

Methodology

Sixty children with obesity with a mean age of 10.06 years (SDS ± 2.22) and 60 age- and sex-matched normal-weighed controls were assessed for anthropometric measures, mean blood pressure percentiles, serum Lyso-GL-1, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting insulin, triglycerides, cholesterol, low-density (LDL-C) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) with calculation of the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and the AIP.

Results

Children with obesity have significantly higher Lyso-GL-1 and AIP than controls. Lyso-GL-1 is significantly positively correlated with body mass index (BMI) z-score, waist/hip ratio z-score, systolic and diastolic blood pressure percentiles, LDL-C, HOMA-IR, and AIP (p < 0.05), being independently correlated with systolic blood pressure percentile, LDL-C, and AIP on multivariate regression analysis.

Conclusion

Serum Lyso-GL-1 is elevated in children with obesity, being closely correlated with hypertension, insulin resistance, and atherogenesis. This could provide a mechanistic insight on the role of Lyso-GL-1 in obesity and atherogenesis. Further studies are warranted to explore the potential role of Lyso-GL-1 as a biomarker and target for the prevention and treatment of obesity-related atherogenesis and insulin resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glucosylsphingosine (also called Lyso-GL-1 or lyso-Gb-1) is a glucosphingolipid primarily formed by the deacylation of glucosylceramide by lysosomal acid ceramidase [1]. This process occurs when glucosylceramide accumulates in lysosomes, particularly within macrophages, and is then converted to glucosylsphingosine, Fig. 1. This conversion is accelerated when glucosylceramide accumulates due to deficiency in the enzyme ß-glucocerebrosidase, a hallmark of Gaucher disease [2, 3]. However, recent studies have demonstrated increased in Lyso-GL-1 in other conditions, including Parkinsonism, hematological diseases, and inflammation [4].

Recently, alterations in lysosphingolipid metabolism has been implicated in the pathogenesis of common metabolic conditions, including obesity and related metabolic disorders [5]. One of these sphingolipids is glucosylceramide; a glycosphingolipid and the precursor of glycosylsphingosine [6]. Adipocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia in obesity lead to adipocyte dysfunction with accumulation of lipotoxic lipid metabolites and subsequent inflammasome activation, together with increased release of free fatty acids and cytokines [1]. In addition, lipid overloading of the adipocytes results in accumulation of ceramides and ceramide metabolites, including glucosylceramides, which, together with the pro-inflammatory state of adipose tissue, result in impaired insulin receptor signaling and metabolic derangements [7]. In vitro and human studies have shown that excessive consumption of fructose and glucose as in sugar-sweetened beverage is accompanied by significant alterion in the ceramides metabolism with accumulation of diacylglycerol, triacylgycerol and ceramides [8, 9]. In addition, pharmacological inhibition of sphingolipid synthesis was found to normalize ceramide profiles and improved sugar induced cardiometabolic risk [9]. Research suggests that increased levels of glucosylceramide and other sphingolipids in obesity contribute to insulin resistance and impaired adipocyte function. Inhibiting the synthesis of glucosylceramide can improve insulin sensitivity and reduce fat accumulation in animal models with obesity [10]. Meanwhile, ceramide accumulation in many metabolic tissues was found in obesity, causing numerous lipotoxic responses, including cell membrane dynamics modulation, endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial stress, and triggering an inflammasome in the endothelial cells and macrophages [11]. Moreover, elevated ceramides are increasingly recognized as a driver of atherosclerosis, being an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, with ceramides, recently named the “second cholesterol,” being elevated in the blood and within the atherosclerotic plaques in people with cardiovascular diseases [12].

The atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) is a valuable tool composed of triglycerides (TG) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) that is commonly used as an indicator of dyslipidemia and cardiovascular risk [13]. Even in children, AIP was found to be closely associated with cardiovascular risk [14].

Hence, this study aimed to assess the serum level of glucosylsphingosine (Lyso-GL-1) among children with obesity and correlate it with waist/hip ratio standard deviation score (SDS) and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) as indicators of insulin resistance, glycemic markers, namely glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and AIP as a biomarker of dyslipidemia and cardiovascular risk.

Materials and methods

Study population

Sixty children with obesity (Body mass index (BMI) ≥ 95th percentile, SDS ≥ 1.64) with a mean age of 10.06 years (SDS ± 2.22) were recruited from the Pediatric Diabetes and Endocrinology Unit, Pediatrics Hospital, Ain-Shams University during the period from January 2025 to April 2025, together with sixty age- and sex-matched healthy normal weighed siblings of children attending the outpatients clinic serving as controls (BMI between the 5th and 85th percentiles for age and sex) [15]. Participants were selected by simple random sampling. Exclusion criteria were family history of Gaucher disease or any hematological manifestations, presence of any cytopenia on complete blood picture, spleenegally by ultrasound, secondary obesity (e.g., Beckwith-Wiedemann, Prader-Willi), hypothyroidism, steroid-induced obesity, and the presence of comorbid chronic illnesses (e.g., diabetes mellitus).

Using the G*Power program for sample size calculation, setting power at 80% and alpha error at 5%, and assuming a medium effect size difference between children with obesity and normal-weight children (d = 0.3) regarding glucosylsphingosine level, based on this assumption, a sample size of at least 45 children with obesity and 45 normal-weight children will be needed.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University (FMASU REC), with an approval number of R 200/2021. Written informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians of each participant before enrollment after a full explanation of the study protocol. The study was done in line with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement 2010 according to the Declaration of Helsinki [16].

Study procedures

Clinical assessment

All participants participating in the study underwent:

(1) Complete history taking, including age, sex, age of onset of obesity, family history of obesity, and socioeconomic status assessed using the validated Arabic socioeconomic status scale for health research in Egypt. It is a scale with 7 domains with a total score of 84 [17].

(2) Physical examination including auxological assessment in the form of weight in kilograms (kg) using the Tanita scale, height in centimetres (cm) using the Harpendenstadiometer, and BMI in kg/m² with calculation of the SDS scores according to age and sex 10. Waist circumference was measured midway between the top of the iliac crest and the lowest rib, while hip circumference was measured in a horizontal plane at the extension of the buttocks, with calculation of the waist/hip ratio and comparison to normal references for age and sex according to Schwandt and colleagues till age 11 years and Mederico et al. above 11 years [18, 19].

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured manually using a mercury sphygmomanometer two consecutive times in the right arm while the patient was relaxed and seated, with calculation of the average and plotting the results on the age- and sex-matched percentiles [20]. Tanner staging was used to assess sexual maturity [21].

Biochemical measurements

About 5 mL of venous blood were withdrawn from each participant in the morning after a 10-h fast and left for complete clotting; then serum was separated by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min and then stored at −20 °C for assessment of:

-

Fasting blood glucose (intra- and inter-assay CVs, 2.3% and 3.5%; respectively) by Beckman Coulter AU 480 autoanalyzer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., 250 S. Kraemer Blvd., Brea, CA 92821, USA) and fasting insulin by immunometric, chemiluminescent assay on IMMULITE Autoanalyzer (Siemens Medical Solution Diagnostics, Los Angeles, USA).

-

Insulin sensitivity was calculated using the HOMA-IR as follows: HOMA-IR = fasting glucose in millimoles per liter × fasting insulin in milli-international units per liter / 22.5. A value of >2.7 was the cutoffused as an index of insulin resistance in children and adolescents [22].

-

Fasting serum TG (intra- and inter-assay CVs, 3.0% and 4.6%; respectively) and total cholesterol (TC) (intra- and inter-assay CVs, 2.8% and 4.2%, respectively) using quantitative enzymatic colorimetric technique by the Beckman Coulter AU 480 system (Beckman Coulter, Inc., 250 S. Kraemer Blvd., Brea, CA 92821, USA). Serum HDL-C (intra- and inter-assay CVs, 3.5% and 5.0%; respectively) by the phosphotungstate precipitation method (Bio Merieux kit, Marcyl’Etoile, Craponne, France). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level was calculated using the Friedewald formula [23]. Dyslipidemia was defined according to the American academiy of pediatrics (AAP) revised consensus statement from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), using the following cut-off levels: TC ≥ 5.2 mmol/L, LDL-C ≥ 3.4 mmol/L, and HDL-C < 1.03 mmol/l with TG ≥ 1.47 mmol/L in children and adolescents 10-19 years of age and ≥ 1.13 mmol/L in children <10 years of age [24].

-

AIP was calculated using the following formula: AIP = log10 (triglyceride/HDL cholesterol). A previously described cut-off of 0.27 in pediatrics was used as a predictor for cardiovascular risk [25].

-

Lyso-GL-1 was assessed using commercially available Human Lyso-GL-1 ELISA kits supplied by Sunlong Biotech Co., Ltd, Hangzhou, China (Catalog No.: SL-3480Hu) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance of each well was measured at 450 nm by using a microtiter plate ELISA reader (Biotek, USA). with a detection range of 3 - 160 ng/L. Biochemical measurements were performed using validated in-house protocol. The coefficient of variation (CV) values were determined in consistent with the manufacturer’s specifications, the intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was <10%, and the inter-assay CV was <12%, based on replicate analyses performed in our laboratory.

-

Another three mL of fresh whole blood were collected in EDTA and used for HbA1c analysis using turbidimetric inhibition immunoassay (TINIA) via the Tina-Quant® HbA1c kit supplied by Roche Diagnostics on the Cobas 6000 auto analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) expressed in percentage.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected, revised, coded, and entered into the Statistical Package for Social Science (IBM SPSS) version 27. The quantitative data were presented as mean, standard deviations, and ranges when their distribution was found to be parametric and median with interquartile range (IQR) when their distribution was found to be nonparametric. Also, qualitative data were presented as numbers and percentages. The comparison between groups with qualitative data was done by using the chi-square test, while the comparison between two independent groups with quantitative data and parametric distribution was done by using the independent t-test and with non-parametric distribution was done by using the Mann–Whitney test. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to assess the correlation between two quantitative parameters in the same group. Before multiple linear regression analysis, several variables were log-transformed to obtain (approximate) normal distribution. The multivariate analysis was adjusted for age, gender, height and socioeconomic scale. Simple regression analysis was first performed to screen potential associations for Lyso-GL-1, followed by a multivariate stepwise linear regression model to identify and determine significant associations for Lyso-GL-1 among children with obesity. Using the approach of stepwise variable selection, stepping up, only variables with a significance level of 0.05 were included in the model. The confidence interval was set to 95%, and the margin of error accepted was set to 5%. So, the p-value was considered significant at the level of < 0.05.

Results

Sixty children with obesity with a median BMI SDS of 3.45 (IQR 3.18–3.93) and a mean age of 10.06 years (SDS ± 2.22) were compared to 60 age- and sex-matched normal-weighed children (p > 0.05). Fifty four of the studied children with obesity were non pubertal (90%), 48 had a Tanner stage of 1 (80%), 6 had a Tanner stage of 2 (10%) and 6 were Tanner stage 5 (10%). Regarding dyslipidemia; 20 children with obesity had hypertriglyceridemia (36.6%), 12 had decreased HDL-C (20%), 10 had elevated TC (16.7%) and 10 had elevated LDL-C (16.7%).

Children with obesity showed significantly higher waist/hip ratios, systolic and diastolic blood pressure percentiles, HOMA-IR and HbA1c than normal-weight children. Moreover, they had significantly higher TC, LDL-C, and AIP with significantly lower HDL-C than normal-weighed children, Table 1 and Fig. 2.

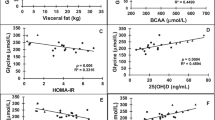

Glucosylsphingosine and obesity

The mean Lyso-GL-1 of the studied children with obesity was 17.25 ng/L, while that of normal-weight children was 7.10 ng/L (p < 0.01), Fig. 3. Lyso-GL-1 was found to be significantly correlated with BMI SDS and waist-hip ratio SDS (p < 0.01), Table 2. Regarding blood pressure, Lyso-GL-1 was found to be significantly correlated with both systolic and diastolic blood pressure percentiles (p < 0.001) among the studied children with obesity being independently associated with systolic blood pressure percentile using multivariate regression analysis (p = 0.040), Fig. 4. As for puberty, no significant relation was found between Lyso-GL-1 and Tanner staging (p = 0.569); however; this needs to be verified in further studies since the number of pubertal children in this study was small (only 6).

Glucosylsphingosine and glycemic markers

Although, no significant correlation was found between serum Lyso-GL-1 level and HbA1c (p = 0.891); it was significantly correlated with HOMA-IR (p < 0.01), Table 2.

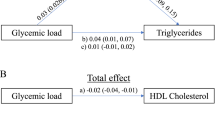

Glucosylsphingosine, dyslipidemia, and atherogenesis

Worth mentioning, Lyso-GL-1 was found to be significantly correlated with LDL-C (p < 0.001), HDL-C (p = 0.05), and AIP (p < 0.01) among children with obesity but not correlated in normal weighed normal weighed children; Table 2; being independently associated with LDL-C (p = 0.007) and AIP (p = 0.007) among children with obesity on multivariate regression analysis; suggesting a possible role for Lyso-GL-1 in the development of dyslipidemia and atherogenesis; Fig. 4.

Discussion

Obesity is characterized by a range of metabolic dysregulations, including insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and systemic inflammation, predisposing to atherogenesis and cardiovascular disease [26]. Despite the extensive research in that field, the exact pathophysiology of such metabolic derangements remains unclear.

Recently, alterations in the glucosylceramides metabolism are gaining attention being implicated in the pathophysiological consequences of obesity, including dyslipidemia, atherogenesis, and cardiometabolic diseases [27]. However, the role of Lyso-GL-1, a lysosphingolipid derivative of glucosylceramide, in obesity and obesity-related complications hasn’t been assessed.

In the current study, children with obesity were found to have significantly higher levels of Lyso-GL-1 than normal-weight children, with 83% of the studied children having Lyso-GL-1 levels above the previously described cut-off values [28]. This goes in line with Mamelli and colleagues, who demonstrated increased acid sphingomyelinase level (enzyme responsible for ceramides formation) in children with obesity [29]. This could be attributed to the chronic inflammatory state and altered lipid metabolism in obesity that contributes to increased turnover of complex sphingolipids, leading to elevated circulating lysolipids like Lysol-GL-1. Moreover, adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity can result in ectopic lipid accumulation and lysosomal stress, potentially enhancing sphingolipid degradation pathways [30]. In addition, increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in obesity may upregulate glucosylceramide synthase and downstream sphingolipid intermediates, further contributing to Lysol-GL-1 accumulation [31]. This observed elevation of Lysol-GL-1 in children with obesity suggests a potential role for this bioactive sphingolipid in obesity-related metabolic dysregulation and highlights the need for identifying new cut-off values for Lyso-GL-1 in people with obesity.

Accumulating evidence suggests a role for glycosphingolipids, including glucosylceramides and their lysolipid counterparts, in insulin resistance through interfering with insulin signaling by activating pro-inflammatory pathways, inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress, and disrupting insulin receptor substrate function [32]. This goes in line with the current study, where a significant positive correlation was found between Lyso-GL-1 and HOMA-IR, suggesting an important role of Lyso-GL-1 in the pathophysiology of insulin resistance among children with obesity. In the same context, a murine study showed that inhibiting glycosphingolipid synthesis can significantly improve insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis, representing a novel therapeutic approach for insulin resistance [33].

In parallel, elevated levels of glycosphingolipids, including glucosylceramide, were found to contribute to dyslipidemia and atherogenesis by interfering with normal lipid trafficking and promoting lipid accumulation in tissues such as the liver and adipose tissue, thereby increasing circulating levels of atherogenic lipids [34]. This goes in concordance with the current study where Lyso-GL-1 was found to be significantly and independently correlated with LDL-C and AIP. Glycosphingolipids have been shown to promote atherogenesis through accumulation in the intima of atherosclerotic plaques and have been shown to exist there at levels higher than any other sphingolipid [35]. Glycosphingolipids do not exist unbound in the plasma but rather are associated with circulating lipoproteins, chiefly LDL-C [36]. Furthermore, glucosylceramide is the greatest inducer of pro-inflammatory cytokines in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells [35]. Indeed, inhibition of glucosylceramide synthesis in mice reduced inflammatory gene expression and atherosclerotic plaque formation [37]. Moreover, recent studies suggest that glucosylsphingosine accumulation promotes vascular inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and macrophage foam cell formation, hallmarks of atherogenesis [38, 39]. Hence, Lyso-GL-1 may facilitate the progression of atherosclerotic lesions through enhancing oxidative stress and activating Toll-like receptor pathways, especially in the context of obesity and metabolic syndrome [40]. Collectively, these findings support a multifaceted role for glucosylsphingosine in linking lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, and atherogenic risk. Further studies are warranted to delineate whether elevated Lysol-GL-1 is a cause or consequence of obesity and to explore its utility as a predictive biomarker or therapeutic target in pediatric metabolic disorders.

Strengths and limitations

This study is among the first to investigate serum Lyso-GL-1 in a pediatric population with obesity, exploring its pathomechanistic relationship with insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and atherogenesis, providing a comprehensive assessment of the potential pathophysiological role of Lyso-GL-1 in atherogenesis.

However, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits its ability to establish causality between Lyso-GL-1 level and atherogenic outcomes. In addition, the young age and prepubertal state of most of the studied children limits it’s ability to verify it’s relation to puberty. Hence, further longitudinal studies with wider age range are warranted to explore whether Lyso-GL-1 is a potential target for prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia and atherogenesis in children with obesity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, serum Lyso-GL-1 is elevated in children with obesity; this elevation is closely linked to insulin resistance and dyslipidemia. Hence, Lyso-GL-1 may serve as an early biomarker of dyslipidemia and vasculopathy, suggesting the need to further elucidate the potential role for Lyso-GL-1 in the prevention and management of dyslipidemia and atherogenesis among children and adolescents with obesity.

Data availability

Data will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Rakhshandehroo M, Van Eijkeren RJ, Gabriel TL, de Haar C, Gijzel SMW, Hamers N, et al. Adipocytes harbor a glucosylceramide biosynthesis pathway involved in iNKT cell activation. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2019;1864:1157–67.

Taguchi YV, Liu J, Ruan J, Pacheco J, Zhang X, Abbasi J, et al. Glucosylsphingosine promotes α-synuclein pathology in mutant GBA-associated Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2017;37:9617–31.

Murugesan V, Chuang W, Liu J, Lischuk A, Kacena K, Lin H, et al. Glucosylsphingosine is a key biomarker of Gaucher disease. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:1082–9.

Aerts JM, Ottenhoff R, Powlson AS, Grefhorst A, van Eijk M, Dubbelhuis PF, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of glucosylceramide synthase enhances insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2007;56:1341–9.

Chaurasia B, Summers SA. Ceramides in metabolism: key lipotoxic players. Annu Rev Physiol. 2020;83:303–30.

Langeveld M, Aerts JMFG. Glycosphingolipids and insulin resistance. Prog Lipid Res. 2009;48:196.

Green CD, Maceyka M, Cowart LA, Spiegel S. Sphingolipids in metabolic disease: The good, the bad, and the unknown. Cell Metab. 2021;33:1293–306.

Walker ME, Xanthakis V, Moore LL, Vasan RS, Jacques PF. Cumulative sugar-sweetened beverage consumption is associated with higher concentrations of circulating ceramides in the Framingham Offspring Cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111:420–8.

Schmiedhofer V, Sommersguter-Wagner J, Knittelfelder O, Jungwirth H, Rechberger G, Carmona-Gutierrez D, et al. Sugar accelerates chronological aging in yeast via ceramides. Cell Stress. 2025;9:158–73.

Giuffrida G, Markovic U, Condorelli A, Calafiore V, Nicolosi D, Calagna M, et al. Glucosylsphingosine (Lyso-Gb1) as a reliable biomarker in Gaucher disease: a narrative review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2023;18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-023-02623-7.

Turpin-Nolan SM, Brüning JC. The role of ceramides in metabolic disorders: when size and localization matters. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:224–33.

Fernández-Ruiz I Ceramides aggravate atherosclerosis via G protein-coupled receptor signalling. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-025-01149-8.

Jin K, Ma Z, Zhao C, Zhou X, Xu H, Li D, et al. The correlation between the atherogenic index of plasma and the severity of coronary artery disease in acute myocardial infarction patients under different glucose metabolic states. Sci Rep. 2025;15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90816-4.

Ali T, Helal R, Khaled R, Sabbour H, Lessan N. Atherogenic index of plasma associated cardiovascular risk in 10,241 pediatric patients. Endocrine Abstracts. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1530/endoabs.90.ep374.

El Shafie A, El-Gendy F, Allahony D, Omar Z, Samir M, El-Bazzar A, et al. Establishment of Z-score reference of growth parameters for Egyptian school children and adolescents aged from 5 to 19 years: a cross-sectional study. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:368.

Saint-Raymond A, Hill S, Martines J, Bahl R, Fontaine O, Bero L. CONSORT 2010. Lancet. 2010;376:229–30.

El-Gilany A, El-Wehady A, El-Wasify M. Updating and validation of the socioeconomic status scale for health research in Egypt. East Mediterranean Health J. 2012;18:962–8.

Schwandt P, Kelishadi R, Haas GM. First reference curves of waist circumference for German children in comparison to international values: the PEP Family Heart Study. World J Pediatr. 2008;4:259–66.

Mederico M, Paoli M, Zerpa Y, Briceño Y, Gómez-Pérez R, Martínez JL, et al. Grupo de trabajo CREDEFAR. Reference values of waist circumference and waist/hip ratio in children and adolescents of Mérida, Venezuela: comparison with international references. Endocrinolía Y Nutrición (Engl Ed). 2013;60:235–42.

Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, Blowey D, Carroll A, Danielset S, et al. Subcommittee on screening and management of high blood pressure in children. Clinical Practice Guideline for Screening and Management of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. PEDIATRICS. 2017;140. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-1904.

Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291–303.

Cuartero BG, Lacalle CG, Lobo CJ, Vergaz AG, Rey C, Villar MJ, et al. Índice HOMA y QUICKI, insulina y péptido C en niños sanos. Puntos de corte de riesgo cardiovascular. An De Pediatría. 2007;66:481–90.

Jolliffe CJ, Janssen I. Distribution of lipoproteins by age and gender in adolescents. Circulation. 2006;114:1056–62.

Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics. 2011;128:S213–56.

Dağ H, İncirkuş F, Dikker O. Atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) and its association with fatty liver in obese adolescents. Children. 2023;10:641.

Reilly MP, Rader DJ. The metabolic syndrome. Circulation. 2003;108:1546–51.

Hammerschmidt P, Brüning JC Contribution of specific ceramides to obesity-associated metabolic diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-022-04401-3.

Elstein D, Mellgard B, Dinh Q, Lan L, Qiu Y, Cozma C, et al. Reductions in glucosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb1) in treatment-naïve and previously treated patients receiving velaglucerase alfa for type 1 Gaucher disease: data from phase 3 clinical trials. Mol Genet Metab. 2017;122:113–20.

Mameli C, Carnovale C, Ambrogi F, Infante G, Biejat PR, Napoli A, et al. Increased acid sphingomyelinase levels in pediatric patients with obesity. Sci Rep. 2022:10996. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14687-9.

Holland WL, Summers SA. Sphingolipids, insulin resistance, and metabolic disease: new insights from in vivo manipulation of sphingolipid metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:381–402. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2007-0025.

Samad F, Badeanlou L, Shah C, Yang G. Adipose tissue and ceramide biosynthesis in the pathogenesis of obesity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011:67–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0650-1_5.

Langeveld M, Aerts JMFG. Glycosphingolipids and insulin resistance. Prog Lipid Res. 2009;48:196–205.

Zhao H, Przybylska M, Wu IH, Zhang J, Siegel C, Komarnitsky S, et al. Inhibiting glycosphingolipid synthesis improves glycemic control and insulin sensitivity in animal models of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:1210–8.

Dawson G, Kruski AW, Scanu AM. Distribution of glycosphingolipids in the serum lipoproteins of normal human subjects and patients with hypo- and hyperlipidemias. J Lipid Res. 1976;17:125–31.

Edsfeldt A, Dunér P, Ståhlman M, Mollet I, Ascuitto G, Grufman H, et al. Sphingolipids contribute to human atherosclerotic plaque inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:1132–40. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.116.305675.

Foran D, Antoniades C, Akoumianakis I. Emerging roles for sphingolipids in cardiometabolic disease: a rational therapeutic target?. Nutrients. 2024;16:3296.

Bietrix F, Lombardo E, Van Roomen CPAA, Ottenhof R, Vos M, Rensen P, et al. Inhibition of glycosphingolipid synthesis induces a profound reduction of plasma cholesterol and inhibits atherosclerosis development in APOE*3 Leiden and low-density lipoprotein receptor−/− mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:931–7.

Hornemann T, Worgall TS. Sphingolipids and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2012;226:16–28.

Hla T, Dannenberg AJ. Sphingolipid signaling in metabolic disorders. Cell Metab. 2012;16:420–34.

Borodzicz S, Czarzasta K, Kuch M, Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska A. Sphingolipids in cardiovascular diseases and metabolic disorders. Lipids Health Dis. 2015;14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-015-0053-y.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nouran Y Salah: conceptualization, data collection, paper writing, and submission. Dina Abdel Hakam: data collection and interpretation, investigation. Sara I. Taha: data collection and interpretation, investigation. Marwa Samir Hamza: data collection and interpretation, investigation. Eman Aly Ramadan: data collection and interpretation, investigation. Rana Mahmoud: data collection and interpretation, investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Ain Shams University with an approval number R 200/2021, and written informed consent was obtained from all cases and their legal guardians before participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salah, N.Y., Abdel Hakam, D., Abdullah, F.A. et al. Elevated serum glucosylsphingosine level in children with obesity: relation to plasma atherogenesis. Int J Obes (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-025-02016-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-025-02016-9