Abstract

Background

Traffic-related air pollutants lead to increased risks of many diseases. Understanding travel patterns and influencing factors are important for mitigating traffic exposures. However, there is a lack of national large-scale research.

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the daily travel patterns of Chinese adults and provide basic data for traffic exposure and health risk research.

Methods

We conducted the first nation-wide survey of travel patterns of adults (aged 18 and above) in China during 2011–2012. We conducted a cross-sectional study based on a nationally representative sample of 91, 121 adults from 31 provinces in China. We characterized typical travel patterns by cluster analysis and identified the associated factors of each pattern using multiple logistic regression and generalized linear regression models.

Results

We found 115 typical daily travel patterns of Chinese adults and the top 11 accounted for 94% of the population. The interaction of age, urban and rural areas, income levels, gender, educational levels, city population and temperature affect people’s choice of travel patterns. The average travel time of Chinese adults is 45 ± 40 min/day, with the longest travel time by the combination of walking and car (70 min/day). Gender has the largest effect on travel time (B = −8.94, 95% CI: −8.95, −8.93), followed by city GDP (B = −4.23, 95% CI: −4.23, −4.22), urban and rural areas (B = −3.62, 95% CI: −3.63, −3.61), age (B = −2.21, 95% CI: −2.21, −2.2), educational levels (B = −1.53, 95% CI: −1.53, −1.52), city area (B = −1.4, 95% CI: −1.4, −1.39) and temperature (B = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.2, 1.21).

Significance

This study was the first nation-wide study on traffic activity patterns in China, which provides basic data for traffic exposure and health risk research and provides the basis for the state to formulate transportation-related policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traffic-related air pollutants (TRAPs), including black carbon, PM10, PM2.5, NO2, NO, CO, and toxic trace pollutants (such as nitro Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, etc.), have adverse effects on human health [1,2,3,4]. For example, TRAPs accelerate aging-related declines in health [5], increase the risk and mortality of cardiovascular disease, asthma, eczema and tuberculosis [6,7,8] and the incidence of hypertension [9,10,11]. The health effects of TRAPs are determined by both traffic-related air pollution levels and travel patterns [12, 13]. Travel activity patterns include travel mode and travel time [14], which specify where and how individuals spend their time on travel [15], and small changes in travel activity patterns due to congestion could lead to significantly increased exposures and health risks attributable to TRAPs that vary largely at different locations [16]. Since the 1980s, time activity patterns have been used to estimate exposures to air pollutants and health risks [17, 18]. However, most of the current studies focus on the characteristics of traffic-related air pollution, and the evaluation of travel activity patterns has been a major weakness repeatedly found [19, 20].

Travel pattern refers to travel modes combination and the corresponding travel time of each mode. Many studies showed that social demographic variables, including age, sex, job, education, car ownership, driver license, family structure, family income, and so on, had a markedly impact on the choice of travel modes. For example, the study from Austin, Texas showed that age, driver license, family income had a markedly impact on the choice of travel modes through a mixed logic model [21]. A study in Korea found that the allocation of travel modes is mainly influenced by personal attributes such as gender, education level, marriage and household attributes based on a three stage least square estimation [22]. Similarly the study in Mumbai showed that type of job and family structure should also be considered [23]. In addition, Asensio [24] found that urban form, residential location, and residential type affected the commuting mode choice in Barcelona. Guo et al. [25] indicated that residents in big cities prefer private cars compared to those in small and medium-sized cities in China. Many studies showed that, even at the same ambient PM2.5 concentration level, personal exposures under different travel modes could be largely different. The primary reason is that the intake of air varies with activity intensity. Specifically, exposure under light-intensity activity (e.g., by car) is less than those under moderate-intensity activity (such as by walking and bicycle, [26]). Travel mode is changing with the development of society and the economy [27]. Before 2013, there were few studies on travel patterns in China. Most studies focused either on specific age groups or on occupational groups in limited regions [28, 29].

The U.S. Department of Transportation launched the first national personal travel survey in 1969, which was renamed as National Household Travel Survey 2001. The survey collected personal travel data, established the relationship between personal travel characteristics and demographics, and obtained travel patterns of the U.S. residents [30]. Japan started the residents’ travel survey in 1967, and then repeated the survey every 10 years to track the changes of travel patterns and the associated factors [31]. In addition, the exposure factors handbook issued by the US, South Korea, Australia and other countries all included traffic-related exposure factors and provided the recommended values of the travel time ([26, 32, 33]). In 2002, the survey of nutrition and health status of Chinese residents investigated travel modes nation wide, but systematic travel pattern data were still missing [34]. Thus we conducted the first nation-wide large sample survey to evaluate the daily travel patterns of Chinese adults. Each person’s specific travel pattern and travel time are provided, which laied the foundation for traffic exposure and health risk assessmentslay and provides the basis for the state to formulate transportation-related policies.

Methods

Subjects

This study is a part of Chinese Environmental Exposure-Related Human Activity Patterns Survey-Adults (CEERHAPS-A). We have 91,527 permanent residents (aged over 18 years) from 159 counties, 636 townships, 1908 villages and street committees in the 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities (excluding Hong Kong, Macao Special Administrative Region and Taiwan) in China. The samples were selected by multi-stage cluster random sampling method and national representative, the distribution of the research objects is shown in Table 1.

Statistical sources

Travel patterns are mainly obtained through questionnaire survey, which has been widely applied to obtain human behavior information in national surveys. For example, the National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS) [17], The German Environmental Survey for Children [35], and U.S. [26] Exposure Factors Handbook [26].

The questionnaires were delivered by specially trained investigators via one-to-one and face-to-face interviews. The questionnaire includes: (1) basic information of the respondents, such as gender, age, nationality, occupation, educational level, family economic status, etc. (2) daily travel mode and average daily travel time used for daily routines in the past 12 months before the survey day, such as going to school, work, or farming. fields. Travel pattern used by retirees and housewives going to fixed places for leisure activitiesare also included. Travel modes include walking, bicycle, electric bicycle, motorcycle, car, bus, subway, ship, and others. Travel time is the accumulated time of multiple trips throughout 1 day. If more than one transport mode was used each day, travel time of each route was listed one by one. The questionnaire was designed by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention of the Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Science. The National Center for Chronic and Noncommunicable Disease Control and Prevention of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention examined and approved the ethical aspects of the questionnaire and interview program.We collected the meteorological data of 159 survey counties in 2012 through the statistical yearbook of each provincial bureau of statistic, including annual average precipitation and annual average temperature, and the city data includes the area, GDP and population.

Statistical analysis

We performed the weighted statistical analysis results using the basic sampling weights and the post-stratified adjustment weights to represent the whole country using our samples [14]. The basic sampling weight calculated the sampling probability and sampling weight of the samples that the respondents belong to in each sampling stage in turn. In order to ensure that the survey sample is nationally representative in terms of important influencing factors such as region, urban and rural areas, gender and age, this survey conducted post stratification weight adjustment based on the 2010 national census data.The final weights were the product of the basic sampling weight and the post-stratified weight (see Supplementary Materials for details).

We identify travel patterns by cluster analysis. To identify the associated factors, we first tested whether each demographic variable has a significant influence on various travel modes using Pearson Chi-square statistics. We then use the nonparametric test for travel time, use Manny–Whitney U rank sum test for gender, urban and rural areas, ethnic group, and use Kruskal-Wallis test for multi-classification variables, such as district, age, education level, occupation type, marital status, housing type, and annual family income. We use multivariate logistic regression analysis to analyze the contribution of demographic variables (including gender, age, urban and rural areas, districts, educational level, occupation, and ethnic group), family attribute variables (including marital status, housing type, and annual income of families), regional attribute variables (including population, GDP, and area of the city), and natural attribute variables (including temperature and precipitation) to travel pattern choice. We use generalized linear regression analysis to identify major factors affecting travel time. The net effects are examined by contrasting the magnitude of coefficients between different variables (B values) of multiple regression analysis. All the analysis was performed in the Statistical Package for the Social and Sciences (SPSS, version 22, IBM Inc., Armonk, New York, NY). We use a two-sided F test with a statistical significance level of 0.05. The graphics were performed with the Origin 2018 (Origin, version 2018, OriginLab).

QA/QC

In this investigation, we formulated a unified quality control scheme and established a quality control network at national, provincial, and county/district levels in three key links: the pre-site investigation, the site investigation stage and the post-site investigation. In the pre-site investigation, all investigators were strictly trained and were required to pass an examination after the training program. Before the large-scale on-site investigation is officially carried out, a pre investigation is conducted on some urban and rural residents in Tianjin. We adjusted and improved the survey based on the results of the pre investigation. In the site investigation stage, we formulated the national three-level supervision scheme to control quality of the survey.

In the survey, the sample replacement rate was 5%, and the response rate was 95%. the questionnaire recovery rate is 100%. Among the 91527 questionnaires collected, province, county/district, urban and rural areas, gender and age were used as key variables for data cleaning. A questionnaire was considered invalid if any key variables had missing values or logical errors. The final number of samples used for analysis was 81,506, and the effective rate of the questionnaire was 90%. After testing the key variables one by one, the response rate of each variable is more than 80%. In the post-site investigation, the national and provincial steering groups selected 3% of the respondents to review and ask 10 questions in the questionnaire, and the consistency rate of the results was 99%. The valid questionnaires were used for subsequent analyses. There is no statistical difference between the sex and age structure of the sample population and the whole population of China, and it has good representativeness [14, 36].

Results

Most Chinese adults use eleven travel patterns

We find 115 travel patterns with a combination of different travel modes. About 75% of the Chinese population take single travel mode, and the rest combine two or more modes, with up to seven at most. We sort the travel patterns from high to low according to the number of people taking the travel pattern. The weighted number of people who take the top 11 travel patterns was 778,294,824, accounting for 94% of the entire population in China. The top 11 travel patterns include six single travel modes and five combined travel modes. Figure 1 shows that walking is the most popular travel pattern (33.2%), followed by motorcycle (14%), electric bicycle (10%), bicycle (7%), and walking+bus (6.2%). Table 2 shows that the median travel time of Chinese adults is 45 min/d. The travel time by car is 40 min/d, longer than those by walking, bicycle, electric bicycle, motorcycle, bus and subway (30 min/d). See the travel time of each travel pattern in Table S1.

Associated factors of travel pattern choice

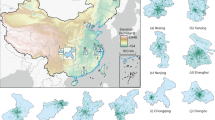

We find significant differences in travel patterns among different genders, ages, and regions. Table 3 shows that women are more likely to travel by walking, bicycle, electric bicycle, bus, and the combination of these travel modes, while men are more likely to use motorcycle and car (walking + motorcycle, walking + car). A similar pattern is observed in U.S. and South Korea, where the proportion of women driving a private car is lower than that of men [26, 32]. In China, people above 75 years are more likely to choose walking as travel mode (74%). In rural areas, the fraction of people who travel by motorcycles is twice of the fraction of the urban population (rural: 18%, urban: 9%). In contrast, the fraction of urban people travel by car (rural: 3%, urban: 6%) is twice of that of rural population. In addition, travel patterns differ among regions (Fig. 2a). For example, people in East China (Jiangsu, Anhui, Zhejiang, and Shanghai) prefer electric bicycles, while people in South China (Hainan, Guangxi, Guangdong, and Fujian) prefer motorcycles. A relatively larger fraction of residents in North China (Ningxia, Tianjin, and Beijing) travel by bicycle and walking + bus.

We find that age (B = −0.453, 95% CI: −0.454, −0.453) has the largest influence on travel patterns choice, followed by urban and rural areas (B = −0.204, 95% CI: −0.204, −0.203), income levels (B = 0.189, 95% CI: 0.189, 0.189), gender (B = −0.17, 95% CI: −0.17, −0.169), and educational levels (B = 0.169, 95% CI: 0.169, 0.17). According to Table S2, men aged 18–44, living in rural areas, with an annual family income of ¥15,000–25,000, with middle school education or above are more likely to travel by motorcycle (walking + motorcycle). Most people travel by electric bicycles (walking + electric bicycle) aged 18~44, living in urban areas, with an annual family income of ¥15,000–19,999, middle school graduate or above. Most people travel on a bicycle (walking + bicycle) aged 18–59, living in urban areas, with an annual family income is ¥5000–10,000. People are more likely to travel by car (walking + car) and bus with increasing in educational and economic level. We find that people with higher education level and higher income are more likely to travel by public transportation. Specifically, using college education level for reference, the odd ratio of people who take a bus with an education level below primary school is only ~0.4. Take annual income level above ¥30,000 for reference, the odd ratio of people take a bus with annual income below ¥5000 is ~0.6. See Table S2 for detailed data.

At city level, population has larger influence (B = 0.1, 95% CI: 0.09,0.1) on travel patterns than GDP (B = 0.01, 95% CI: 0.011, 0.012) and area (B = −0.06, 95% CI: −0.06, −0.06). Compared with cities of population less than 2.5 million, more people in cities with a population of 7.5–10 million travel by bus (walking + bus). Shen et al. [37] found that higher population density relates positively to the likelihood of traveling by subway. Luan et al. [38] found that in large cities, such as London, Paris, Tokyo, public transportation accounts for a larger proportion of commute, which is consistent with the fact that people in cities with higher GDP are more likely to travel by bus [39].

When precipitation is less than 500 mm, temperature significantly affects the choice of travel mode. People prefer to travel by bicycle and walking + bicycle (OR = 2.3–2.6) when temperature is in 5–10 °C, by car and walking + car (OR = 2.3–2.6) when temperature is in 15–20 °C, and by motorcycle and walk + motorcycle (OR = 1) when temperature is above 20 °C. This is different from the conclusion of a study in Norway [40], which showed that on rainy days, the likelihood of car use would increase compared to typical cloudy weather, and ice or snow also led to a slight increase in car preference.

Associated factors of travel time

The median travel time of Chinese adults is 45 ± 40 min/d. Figure 1 shows that the travel time of motorcycle, bicycle and electric bicycle is the shortest (30 min/d), and travel time of walking + car is the longest (70 min/d). In South Korea and Australia, car travel time is also longer than other travel modes [32, 33]. This national trend also applies to provinces, except in Tibet and Tianjin, where the travel time of walking and bus are the longest, respectively (Fig. 2b). In Tibet, a long walking time is possibly related to ethnic-religious habits. In Tianjin, the unique urban traffic structure is the major reason for the long travel time by bus. Three resident travel surveys in 1981, 1993, and 2000 in Tianjin also showed that travel time by bus is longer than that of other travel modes [41]. It is conceivable that the travel time of patterns with a combination of two modes is significantly longer than that of a single mode (P < 0.05).

For socioeconomic characteristics and demographic factors, gender (B = −8.94, 95% CI: −8.95, −8.93) has the largest impact on travel time, followed by urban and rural areas (B = −3.62, 95% CI: −3.63, −3.61), age (B = −2.21, 95% CI: −2.21, −2.2), educational levels (B = −1.53, 95% CI: −1.53, −1.52), occupation (B = −0.63, 95% CI: −0.63, −0.63), and income levels (B = −0.17, 95% CI: −0.17, −0.16). According to the results of the generalized linear model (Table S3), the travel time of men (50 ± 50 min/d) is longer than that of women (40 ± 30 min/d). Two studies in U.S. and South Korea also showed that the travel time of women is shorter than that of men in general [32, 42]. We also find that the travel time of rural people is shorter (Estimate = −2.93, 95% CI: −3.95, −1.91) than that of urban residents. Travel time decreases with the increase of education level and income (income < ¥20,000). A U.S. study showed similar results: people with incomes < $15,000 travel longer than those with incomes > $15,000 [43]. For different occupations, it is conceivable that drivers generally travel for much longer than other occupations (Estimate = 44.25, 95% CI: 41.12, 47.39).

For city parameters, population has a positive influence (B = 2.64, 95% CI: 2.63, 2.64) on travel time, while GDP (B = −4.23, 95% CI: −4.23, −4.22) and area (B = −1.4, 95% CI: −1.4, −1.39) show negative effects. According to Table S3, cities with population above 5 million show longer travel time. This is consistent with a recent study [43], which showed that mean walking times of people living in an area with population of <4000, 4000–9999, 10,000–24,999, and >25,000 per square mile are 18.8, 24.4, 24.5, and 26.4 min, respectively. Travel time decreases monotonically with GDP. Travel time increases with area when area is below 10,000 km2 (Estimate5000–9999.9 km2 = 3.76, 95% CI: 2.05,5.47), but decreases with increasing area (Estimate15,000–19,999 km2 = −2.61, 95% CI: −4.27, −0.95; Estimate>20,000 km2 = −2.96, 95% CI: −4.73, −1.2) when city area is above 15,000 km2.

We find that precipitation (<1500 mm) is negatively related to travel time (Table S3). Travel time decreases by 7–10 min when precipitation increases from 500 mm to 500–1000 mm, and by 3–7 min when precipitation increases from 500 mm to 1000–1500 mm.

Discussion

This study is the first systematic survey of travel patterns of Chinese adults nation wide with a large sample size, which represents the overall Chinese adults after weighting. It not only provides an important reference value for health research related to TRAPs, but also have important guiding significance for reducing human traffic exposure from the perspective of travel patterns.

The majority of Chinese (56%) choose to walk, and only 6.3% travel by private cars. In contrast, more than 90% of adults prefer to travel by car in the U.S. and South Korea [44]. A similar pattern is observed in the elderly in our study (>65 years old): 89.5% choose private cars in the U.S., while more than 60% of people with the same age in China prefer walking. This is possibly due to two reasons: First, car ownership in the U.S. and South Korea is much larger than that in China at the time of this survey; Second, residents in China live in compact communities, in which walking is the most convenient travel mode. Private car ownership rate in Japan is high (>50%), but only 6% of the whole population travel by car [31]. More than 90% of Japanese use public transportation [45]. A possible reason is the convenient public transportation developed in Japan, composed of ground express railway, underground express railway, trams, and ground buses, with convenient connections among these different travel modes. In contrast, the penetration rate of China’s subway in cities was <7% in 2011 and only 15.2% of the total population take public transportation system. The subway penetration rate increase to 13% in 2020 and will continue to increase in the future. Thus, this study might underestimate the proportion of public transport in China now and in the future. The development of different regions has changed a lot from 2011 to now, so we compared the data of city GDP/population/area from 2011 to now, and found that both urban area and population are not much different. For urban GDP, for example, we found that Shanghai in 2011 had the same GDP as Guangxi in 2019, and Guangdong in 2011 had the same GDP as Henan in 2011. Therefore the results of the study are still relevant today (Fig. 3).

The median travel time of Chinese adults (45 min/d) is lower than that of the United States (96 min/d), Australia (60 min/d), and South Korea (82.8 min/d). This is closely related to the different major travel modes in these countries. Travel time by car is in general longer than other modes. Different from China, the travel time of people living in rural areas is longer than those living in cities in the United States. This is possibly related to the different lifestyles in the two countries [32, 33, 42]. People in the U.S. usually live in a dispersed rural area and work in an urban center, thus the commute distance is usually longer than that in China, where people live in relatively compact communities in an urban area and also work inside the urban area. In addition, in China, the proportion of private cars owned by urban residents is larger than that in rural areas [46].

We have noticed similarities and discrepancies between this national survey and previous city-scale studies in China. A study in Beijing showed that adults’ average daily travel time was 70 min/d on working days, 120 min/d on weekends in summer, and 60 min/d in winter [47, 48]. Meng et al. [49] found that people over 60 years spent less time on transportation than young and middle-aged adults. These results are similar to our survey in Beijing. A study in Taiyuan, Shanxi province showed that travel time by walking and bus was 12 min/d, and 18 min/d by bicycle [29], shorter than the results of this study (walking: 35 min/d, bicycle: 30 min/d and bus: 40 min/d). A study in Shanghai showed that the proportion of buses is 25.2%, larger than that in this study (19.7%) in 2009 [50]. In contrast, the proportions of walking (26.2%), bicycle (13.5%), and electric bicycle (15.2%) are lower than those in our study (walking: 44.8%, bicycle: 16%, electric bicycle: 29.1%). The discrepancies can be explained by sample representativeness, survey methods, and temporal variation. The research in Taiyuan and Shanghai is mainly stratified sampling by urban and rural areas. However, our study and Wang’s study in Beijing adopt stratified sampling design based on urban and rural areas and gender, respectively.

In addition to gender, age, education, and economic levels, other factors such as residential types, ethnic, and marital status also influence the travel pattern choice of Chinese adults. We find that people living in unit buildings tend to choose to walk and travel by bus, people living in bungalows tend to choose motorcycles, bicycles, or cars to travel. Prillwitz et al. (2011) have found that married families with children have a higher dependence on cars. Our results also show that the daily travel time of married people is about twice of single people. We find that ethnic minorities people travel longer than Han nationality. In the U.S., minorities were more likely to spend more time (≥30 min) walking [51].

In addition to the top 11 travel patterns, we also analyzed some other representative travel patterns. People who choose ships for travel are women aged 50–54 years, living in urban South China with an income of ¥10,000–20,000. Among the people who used “others” travel modes, rural and male account for 67% and 74.6%, respectively. Thus, these “others” travel modes are possibly agricultural vehicles. Men in rural areas are the main social activists, while women rarely drive motorcycles, agricultural vehicles, and private cars alone (RENNE, 2005). We also study travel patterns in the 31 provinces (autonomous regions and municipalities) in China. As shown in Fig. S1, travel patterns of the 31 provinces are different from those of the whole country. Bicycles and electric bicycles are the most popular travel modes in Beijing and Shanghai, respectively. Subway has become one of the top 10 travel patterns in the two cities. Motorcycles are the most popular travel mode in Hainan Province, while the bus is most commonly used in Qinghai Province.

This is the first systematic survey of travel patterns of Chinese adults nation wide with a large sample size, which represents the overall level of Chinese adults after weighting. It provides a critical reference value for health research related to TRAPs However, this study has several limitations. Firstly, this is a cross-sectional study, and thus it is impossible to obtain a causal relationship. Secondly, this study is based on self-report surveys, which is objective. Thirdly, important influencing factors of travel mode, such as vehicle ownership or travelers’ psychological status, are not involved in the survey [52].

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, (XD), upon reasonable request.

References

Gan WQ, Davies HW, Koehoorn M, Brauer M. Association of long-term exposure to community noise and traffic-related air pollution with coronary heart disease mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:898–906. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr424.

Grigoratos T, Martini G. Brake wear particle emissions: a review. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2014;22:2491–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-014-3696-8.

Liang D, Golan R, Moutinho JL, Chang HH, Greenwald R, Sarnat SE, et al. Errors associated with the use of roadside monitoring in the estimation of acute traffic pollutant-related health effects. Environ Res. 2018;165:210–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.04.013.

Sunyer J, Esnaola M, Alvarez-Pedrerol M, Forns J, Rivas I, Lopez-Vicente M, et al. Association between traffic-related air pollution in schools and cognitive development in primary school children: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001792. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001792.

Weuve J, Kaufman JD, Szpiro AA, Curl C, Puett RC, Beck T, et al. Exposure to traffic-related air pollution in relation to progression in physical disability among older adults. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:1000–8. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1510089.

Huls A, Abramson MJ, Sugiri D, Fuks K, Kramer U, Krutmann J, et al. Nonatopic eczema in elderly women: Effect of air pollution and genes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:378–85.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2018.09.031.

Blount RJ, Pascopella L, Catanzaro DG, Barry PM, English PB, Segal MR, et al. Traffic-related air pollution and all-cause mortality during tuberculosis treatment in California. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp1699.

Bowatte G, Lodge CJ, Knibbs LD, Erbas B, Perret JL, Jalaludin B, et al. Traffic related air pollution and development and persistence of asthma and low lung function. Environ Int. 2018;113:170–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.01.028.

Fuks KB, Weinmayr G, Basagaña X, Gruzieva O, Hampel R, Oftedal B, et al. Long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and traffic noise and incident hypertension in seven cohorts of the European study of cohorts for air pollution effects (ESCAPE). Eur Heart J. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw413.

Fuks KB, Weinmayr G, Foraster M, Dratva J, Hampel R, Houthuijs D, et al. Arterial blood pressure and long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution: an analysis in the European Study of Cohorts for Air Pollution Effects (ESCAPE). Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:896–905. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1307725.

Alexeeff SE, Coull BA, Gryparis A, Suh H, Sparrow D, Vokonas PS, et al. Medium-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution and markers of inflammation and endothelial function. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:481–6. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1002560.

Chen Y, Ebenstein A, Greenstone M, Li H. Evidence on the impact of sustained exposure to air pollution on life expectancy from China’s Huai River policy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:12936–41. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1300018110.

Lubin JH, Moore LE, Fraumeni JF, Cantor KP. Respiratory cancer and inhaled inorganic arsenic in copper smelters workers: a linear relationship with cumulative exposure that increases with concentration. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1661–5. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.11515.

Duan XL. Exposure Factors Handbook of Chinese Population. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China, Beijing; 2013.

Zhang K, Batterman SA. Time allocation shifts and pollutant exposure due to traffic congestion: an analysis using the national human activity pattern survey. Sci Total Environ. 2009;407:5493–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.07.008.

Zhang K, Batterman SA. Air pollution and health risks due to traffic and congestion. Sci Total Environ. 2013;450-1:307–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.01.074.

Klepeis NE, Nelson WC, Ott WR, Robinson JP, Tsang AM, Switzer P, et al. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): a resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. J Exposure Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2001;11:231–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jea.7500165.

McCurdy T, Glen G, Smith L, Lakkadi Y. The National Exposure Research Laboratory’s consolidated human activity database. J Exposure Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2000;10:566–78. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jea.7500114.

AQEG. Particulate matter in the United Kingdom. Second Report (Draft) from the Air Quality Expert Group (AQEG). UK, 2004.

Suh H. Particulate matter. In: Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, editor. Exposure assessment in occupational and environmental epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Bhat CR, Sardesai R. The impact of stop-making and travel time reliability on commute mode choice. Transportation Res Part B Methodol. 2006;40:709–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trb.2005.09.008.

Jang TY. Causal relationship among travel mode, activity, and travel patterns. J Transport Eng ASCE. 2003;129:16–22. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)0733-947x(2003)129:1(16).

Patil GR, Basu R, Rashidi TH. Mode choice modeling using adaptive data collection for different trip purposes in Mumbai metropolitan region. Transport Dev Econ. 2020;6:9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40890-020-0099-z.

Asensio J. Transport mode choice by commuters to Barcelona’s CBD. Urban Stud. 2016;39:1881–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098022000003000.

Guo J, Luo MJ, Cui SS, Chen N. Research on urban residents’ travel mode choice based on structural equation model. Highways and Automotive Applications. CNKI:SUN:ZNQY.0.2020-02-009. 2020:30–35.

EPA. U.S. Exposure Factors Handbook. Washington, DC: USEPA; 2011.

Gong WT, Feng GY, Yuan F, Ding CC, Zhang Y, Liu AL. Analysis on the changing trends of transportation modes and time among Chinese non-agricultural professional population in 2002 and 2010-2. Acta Nutrimenta Sin. 2017;39:327–31. CNKI:SUN:YYXX.0.2017-04-007.

Li TT, Yan M, Liu JF, Zhang GS, Luo M, Huo MQ, et al. Air quality assessment in public transportation vehicles in Beijing. 2008:514–6. https://doi.org/10.16241/j.cnki.1001-5914.2008.06.024.

Wang BB, Duan XL, Jiang QJ, Huang N, Qian Y, Wang ZS, et al. Inhalation exposure factors of residents in a typical region in Northern China. Res Environ Sci. 2010;23:1421–7. CNKI: SUN: HJKX.0.2010-11-015.

Santos ANM, Nakamoto HY, Gray D, Liss S. Summary of Travel Trends: 2009. National Household Travel Survey; U.S., 2011.

Liu MJ. Traffic survey in Japan. Traffic and transportation. 2000:32–34. CNKI:SUN:YSJT.0.2000-02-017.

Jang JY-JS, Kim SY, Kim SJ, Cheong HK. Korea Exposure Factors Handbook. 2007.

Australia. (2012) Australia Exposure Factor Guide. Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Ma GS, Kong LZ. Survey report on nutrition and health status of Chinese residents: behavior and lifestyle in 2002. Beijing: People’s medical publishing house; 2002.

Conrad A, Seiwert M, Hunken A, Quarcoo D, Schlaud M, Groneberg D. The German Environmental Survey for Children (GerES IV): Reference values and distributions for time-location patterns of German children. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2013;216:25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2012.02.004.

Zou B, Li S, Lin Y, Wang B, Cao S, Zhao X, et al. Efforts in reducing air pollution exposure risk in China: State versus individuals. Environ Int. 2020;137:105504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105504.

Shen Q, Chen P, Pan H. Factors affecting car ownership and mode choice in rail transit-supported suburbs of a large Chinese city. Transportation Res Part A Policy Pract. 2016;94:31–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2016.08.027.

Luan X, Deng W, Cheng L, Chen XY. Mixed Logit model for understanding travel mode choice behavior of megalopolitan residents. Journal of Jilin University (Engineering and Technology Edition). 2018. https://doi.org/10.13229/j.cnki.jdxbgxb20170561.

Ling XJ, Yang T, Shi Q. Discussion on public transit mode share. Urban Transport of China. 2014:26–33. https://doi.org/10.13813/j.cn11-5141/u.2014.0505.

Christian AK, Friedrichsmeier T. A multi-level approach to travelmode choice—how person characteristics and situation specific aspects determine car use in a student sample. 2011;14:0–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2011.01.006.

Jiang Y, Zou Z. Impact of travel time consumption on Tianjin public transport travel and Its Improvement Countermeasures, Annual meeting and Symposium of China Urban Transport Planning Academic Committee. 2005. https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/conference/6130081.

USA. Exposure Factors Handbook: 2011 Edition. 2011.

Lilah M, Besser M, Andrew L, Dannenberg MD,MPH. Walking to public transit: steps to help meet physical activity recommendations. Am J Preven Med. 2005;29:273–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.010.

Collia DV, Sharp J, Giesbrecht L. The 2001 National Household Travel Survey: a look into the travel patterns of older Americans. J Saf Res. 2003;34:461–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2003.10.001.

Li ZY, Li C, Yin ZF. Development of transportation carbon emission in Germany and Japan and Its Enlightenment to China. Highways and Automotive Applications. 2014:35–8. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-2668.2014.01.011.

Pucher J, Renne JL. Rural mobility and mode choice: Evidence from the 2001 National Household Travel Survey. Transportation. 2005;32:165–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-004-5508-3.

Wang CM, Shi YP, Wei JR, Ma Y, Zhang Y. Characteristics of time-activity patterns of adult residents in Beijing in winter. Capital J Public Health. CNKI:SUN:SDGW.0.2017;05;19–23.

Wang CM, Zhao JH, Shi YP, Zhang Y, Su P, Li T. Characteristics of time-activity patterns of residents living in Beijing in summer. J Environ Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.16241/j.cnki.1001-5914.2019.08.015.

Meng B, Zheng LM, Yu HL. Commuting time change and its influencing factors in Beijing. Prog Geog. 2011;30:1218–24. https://doi.org/10.11820/dlkxjz.2011.10.003.

Lu XM, Gu XT. The fifth travel survey of residents in Shanghai and characteristics analysis. Urban Transp China. 2011;000:1–7. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-5328.2011.05.001.

Besser LM, Dannenberg AL. Walking to public transit: steps to help meet physical activity recommendations. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:273–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.010.

Jan P, Stewart B. Moving towards sustainability? Mobility styles, attitudes and individual travel behaviour. J Trans Geog. 2011;19:0–1600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.06.011.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the study participants and field investigators.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation [grant numbers 41977374].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NJ: Methodology, writing—review and editing, writing—original draft, visualization. LQ: Formal analysis, writing—review and editing. BW: Methodology, investigation, data curation. SC: Writing—review and editing. LW: Methodology, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing. BZ: Resources, data curation. KZ: Writing—review and editing. NQ: Writing—review and editing. XD: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, N., Qi, L., Wang, B. et al. Traffic related activity pattern of Chinese adults: a nation-wide population based survey. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 33, 482–489 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-022-00469-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-022-00469-y