Abstract

Background

The prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) pulmonary infection (NTM PI) varies geographically in the United States (US). Previous studies indicate that trace metals in environmental source water increase NTM PI risk.

Objective

To examine the effect of trace metals, chromium (Cr), cobalt (Co), molybdenum (Mo), strontium (Sr), and vanadium (V) in public distribution system water on NTM PI risk among susceptible persons in the US.

Methods

We studied NTM PI risk as a function of trace metal exposure from public distribution system water in two US patient populations: (1) The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry. (2) The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Patient data were extracted for the period 2010–2019. We obtained data on trace metal concentrations from the US Environmental Protection Agency, Third Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule dataset. We used logistic and negative binomial generalized linear models to estimate NTM PI risk as a function of trace metal exposure in treated drinking water at the county level. Our models were adjusted for patient demographics, source water type, climate variables, and the type of disinfectant used.

Results

Our cystic fibrosis (CF) population comprised 14,251 persons with CF, including 4020 NTM cases and 10,231 controls. Our Medicare population comprised 27,146,753 beneficiaries, including 84,075 NTM cases. In the Medicare analysis, V was associated with increased NTM PI risk in the Midwest, South, and West, while Mo increased NTM PI risk in the West. In the CF analysis, V increased NTM PI risk in the South, while Mo was associated with increased NTM PI risk in the West. In both the CF and Medicare populations, using chloramine as a disinfectant significantly increased NTM PI risk.

SIGNIFICANCE

Mo and V in treated water was associated with increased risk among persons susceptible to NTM PI. The effect of trace metals varies by geographic region

Impact

-

The incidence and prevalence of NTM, a waterborne pulmonary infection, have been increasing in the US and have been shown to vary geographically. Our study has shown that trace metals, specifically molybdenum and vanadium, in treated drinking water significantly increase the risk of NTM pulmonary infection across the US. Our study also shows that the effect of trace metals varies by geographic region. Our research may lead to the monitoring of trace metals in drinking water as well as in susceptible populations, and ultimately, may be incorporated into a framework for NTM prevention efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) pulmonary infection (NTM PI) has become an increasingly prevalent waterborne pulmonary infection in the United States (US) [1, 2]. The incidence of NTM PI has been increasing in the US in both the cystic fibrosis (CF) and non-CF populations [3, 4] and is increasingly becoming a public health concern [2]. Therefore, identifying risk factors for exposure is central to prevention efforts.

NTM have been isolated throughout the water supply system, including natural source water [5, 6], water treatment facilities [5, 6], water distribution systems [5,6,7], premise plumbing [8, 9], potable water taps [5, 6, 10], and showerheads [11, 12]. NTM infections have been found to be the leading cause of drinking water-associated illnesses, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations [13]. Though exposure to NTM is common, the environmental distribution of NTM and the prevalence of NTM PI vary geographically in the US [11, 14,15,16,17,18,19]. These geographic differences are not explained by host-related factors and are likely due to variation in regional environmental conditions. Specific water-related factors favoring NTM growth and persistence likely increase the risk of exposure in particular environments.

In recent studies, we examined the relationship of NTM PI and water-quality constituents in environmental water sources that supply public water systems. These studies, conducted in three US states (Colorado, Hawai’i, and Oregon) [20,21,22,23] and at a subnational level across eleven US states [24], demonstrated that the trace metals molybdenum (Mo) and vanadium (V) in surface water and groundwater were associated with increased risk of NTM PI in both CF and non-CF populations. This evidence suggests that trace metal exposure from natural water sources may contribute to the geographic variation of NTM PI.

To estimate the effect of trace metal exposure from treated water in public distribution systems, we obtained US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) data on trace metal measurements from public water systems (PWSs) collected under the Third Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 3) [25]. The US EPA uses the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR) to collect data on contaminants that are suspected to be present in drinking water and do not have health-based standards set under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) [25]. We associated data from the Third Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 3) with national CF patient data extracted from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry (CFFPR) [26] and from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) [27]. Here, we describe two population-based analyses to investigate the relationship between trace metals in treated water and the risk of NTM PI among susceptible persons in the US while controlling for patient demographic variables and water disinfectants, as well as environmental variables, including climate variables and source water type.

Materials and methods

Data collection

Patient data

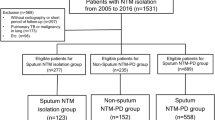

We obtained national NTM data from two sources: the CFFPR [26] and CMS [27]. Patient data from both sources were extracted for the study period 2010-2019.

The CFFPR includes data on >90% of persons with cystic fibrosis (pwCF) residing in the US. We included data on patients ≥ 12 years with a US zip code. We obtained data related to patient zip code, NTM pulmonary cultures, and patient demographics. Incident cases were defined as pwCF who had at least one positive NTM pulmonary culture preceded by two negative cultures during the study period and who lived in the same county for at least one year prior to their first positive culture. Controls were defined as pwCF who had at least two negative pulmonary cultures within a single county over a period of at least two years and had no history of positive cultures. Hereafter, we refer to this as the ‘CF analysis’. We also obtained patient data from the Medicare Part B claims dataset provided by CMS. Medicare Part B incident NTM cases were defined as Medicare beneficiaries aged >= 65 years who had (1) at least one claim associated with either ICD-9 031.0 (pulmonary diseases due to other mycobacteria) or ICD-10 A31.0 (pulmonary mycobacterial infections (other than tuberculosis)), (2) no prior claims associated with ICD-9 031.0 or ICD-10 A31.0 claims in the 24 months prior to the date of the incident claim, and (3) had a single reported county-level Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) code of residence for 24 months prior to the first claim. Hereafter, we refer to this as the ‘Medicare analysis’.

This study was classified as nonhuman subjects research by the National Institutes of Health, Office of Human Subjects Research Protection, because patient data were de-identified, and investigators could not link back to identifiable data.

Water-quality data

We obtained trace metal data from the US EPA UCMR 3 dataset [25]. The UCMR 3 required monitoring for 30 unregulated contaminants by public water systems (PWSs) between January 2013 through December 2015. Included in this dataset were all PWSs serving more than 10,000 people and 800 representative PWSs serving 10,000 or fewer people from across the fifty US states and the District of Columbia. Sampling points used in data collection occurred at entry points to the distribution system and at the distribution system's maximum residence time, indicating the point at which treated water has been in the distribution system for the maximum time.

We accessed the UCMR 3 data on 3 January 2023. While the majority of PWSs reported their service area zip codes, if a given PWS did not report the latitude/longitude coordinates or at least one zip code, their associated water data were eliminated from our dataset. Our dataset included 4915 PWSs with trace metal data available and at least one zip code or latitude/longitude coordinates reported. We geocoded the zip code or latitude/longitude coordinates of each PWS to their respective county using the United States Postal Service (USPS) zip code database. We restricted the data to include only the five trace metals that were measured in the UCMR 3: chromium (Cr), Cobalt (Co), Mo, Strontium (Sr), and V (Fig. 1). Trace metal county-level statistics by region are presented in Table 1. Supplementary Table 1 shows the correlation matrix for Cr, Co, Mo, Sr, and V. Data were cleaned and analyzed using R (version 4.2.1), and R packages MASS [28], corrplot [29], stats [30], effects [31, 32], car [31]. The cleaned dataset used in this analysis required identifying and reformatting zip codes or latitude/longitude coordinate data entry errors. Our data cleaning steps are detailed in Appendix 1.

We extracted data on source water type as reported by each PWS, which included surface water, groundwater, groundwater under the influence of surface water, and mixed water. Any county with all PWSs reporting the use of multiple water types was designated as mixed water use in our analysis. We also extracted data on the use of disinfectants reported by each PWS. We created four categories of disinfectants: Chlorine, Chloramine, Hypochlorite, and Other. The “Other” grouping was comprised of categories termed “chlorine dioxide”, “ozone”, “ultraviolet light”, “no disinfectant used”, and “all other types of disinfectants”, each of which was reported by only a small number of PWSs. Since most PWSs reported the use of multiple disinfectants, we used this variable in our analysis as follows: a given county was assigned to one or more disinfectant groups (i.e., Chlorine, Chloramine, Hypochlorite, Other), if the PWSs within that given county reported usage. Therefore, disinfectant categories were represented as present or absent for a given county.

Trace metal concentrations below the Minimum Reporting Level (MRL) were replaced by the MRL divided by the square root of two (this method was suggested in a personal communication with a United States Geological Survey (USGS) scientist, as well as having been used in previous studies [33]). For Cr, Co, Mo, Sr, and V, these MRL values were 0.141, 0.707, 0.707, 0.212, and 0.141 µg/L, respectively. The percent of trace metals that exceeded the MRL in each US region is shown in Table 1. We added 1 to individual trace metal measurements and then applied the natural log transformation to each value, so the transformed values were always greater than zero. We then aggregated all water samples by county and calculated the mean (average) trace metal measurement for each county. We next standardized the mean log concentrations to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 at the regional level (Midwest, Northeast, South, West). Every patient was assigned the mean value (transformed and standardized) of each trace metal for their respective county of residence.

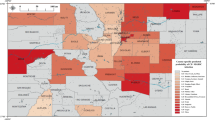

Our final datasets excluded counties without trace metal data and included only counties that had patient data with corresponding trace metal data. In the CF analysis, counties with at least one case or one control in residence were included, representing 1467 counties, or 46.7% of all US counties. In the Medicare analysis, counties with at least 1 beneficiary in residence were included, representing 1721 counties, or 54.7% of all US counties. We obtained measurements for Cr, Co, Mo, Sr, and V from PWSs across the US (sample sizes are shown in Fig. 1). Counties with both patient and trace metal data are shown in Fig. 2A, B. Maps were generated using ArcGIS Pro (Environmental Systems Research Institute (Esri). 2022. ArcGIS Pro 3.0.0. Redlands, CA).

A County-level NTM risk among persons with CF. Grey lines represent county line boundaries, orange lines represent state line boundaries in the US. State abbreviations are printed in black. White regions represent counties without patient and/or water data. B County-level NTM risk among Medicare recipients. Grey lines represent county line boundaries, orange lines represent state line boundaries in the US. State abbreviations are printed in black. White regions represent counties without patient and/or water data.

Climate data

To control for climate factors that influence risk, we selected climate predictors that are also associated with our exposures of interest. We obtained data on precipitation and floods for the study period, 2010–2019, from Weather Source, LLC. Precipitation was calculated as the mean of total yearly precipitation by county. Floods were the total number of Flood NWS Warnings for each county over the study period.

Statistical analysis

Generalized Linear Models

We used generalized linear models (GLMs) to model NTM PI risk as a function of trace metal exposure in distribution system water. County-level standardized mean values of each trace metal were included. We constructed two models, one for the CF analysis and one for the Medicare analysis, that each included Cr, Co, Mo, Sr, and V as explanatory variables. The correlation matrix for these trace metals is shown in the Supplement (Supplementary Table 1). Demographic variables (age, sex, median income), climate variables (precipitation, flood warnings), water disinfectants (chlorine, chloramine, hypochlorite, other disinfectants), and source water type (surface water, groundwater, mixed water) were also included as covariates in each model. To account for interaction between Mo and V and between precipitation and floods, we included interaction terms for Mo and V and for precipitation and floods in the regression models. To account for regional influence on each of the variables, we included interaction terms between each model variable (demographic variables, source water type, climate variables, disinfectants used, and trace metals) and each of the four US regions: Midwest, Northeast, South, and West. We used the glht() procedure in the multcomp package [34] in R to adjust for multiple comparisons. We estimated the odds of NTM PI among pwCF and the rate of NTM PI among Medicare recipients given exposure to varying trace metal concentrations in PWSs across the US. We report an adjusted odds ratio in the CF analysis, an adjusted rate ratio in the Medicare analysis, 95% confidence interval (CI), and p-value for each model variable. Finally, we estimate the county-specific risk of NTM PI among pwCF and Medicare recipients based on trace metal exposure in PWSs (Fig. 2A, B).

Results

Study population characteristics

In the CF population, 14,251 pwCF who met our case or control definitions and had corresponding county-level trace metal data were included in our analysis. This population comprised 4,020 NTM cases and 10,231 culture-negative controls. In the Medicare population, 27,146,753 Medicare beneficiaries, who met our inclusion criteria and had corresponding county-level trace metal data, were included in our analysis. This included 84,075 Medicare patients who met our NTM case definition. Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of CF cases and controls, as well as Medicare cases and beneficiaries residing in each US region (Midwest, Northeast, South, West).

Generalized linear models

The interpretation of final models assumes that additional variables in the model remain fixed while the value of the variable being interpreted changes. For pwCF living in Southern counties, the odds of NTM infection increased by 27% (95% CI 1.05, 1.54) for every unit increase in, V and in Western counties, the odds of NTM infection increased by 32% (1.09, 1.61) for every unit increase in Mo (Table 3A). While we did not observe any statistically significant associations in other regions, the effect of V in the Midwest was borderline significant and, with a larger sample size may have achieved significance (Table 3A). For Medicare recipients living in Midwestern counties, every 1- standardized log unit increase (hereafter referred to as ‘unit increase’) in V in public water increased the incidence rate of NTM PI by 13% (1.02, 1.24) (Table 3B). In Southern counties, the incidence rate of NTM PI decreased by 9% (0.85, 0.97) for every unit increase in Cr. We also observed a significant interaction effect between V and Mo for counties in the South (Table 3B). The risk of NTM PI increased by 15% (1.06, 1.24) for every unit increase in V when the concentration of Mo was at its mean value in Southern counties (Table 3B) and increased by 18% (1.07, 1.30) for every unit increase in V when Mo was at its minimum value in Southern counties (Supplementary Table 2B). In Western countries, the incidence rate of NTM infection increased by 10% (1.01, 1.19) for every unit increase in V and 12% (1.01, 1.25) for every unit increase in Mo (Table 3B). We did not observe significant associations for any metals in the Northeast in either the CF or Medicare analyses.

Among disinfectant types, chloramine usage showed a significantly increased risk of NTM PI among Medicare patients in the Midwest and South. We observed an increase of 32% (1.11, 1.57) in the Midwest, and 39% (1.23, 1.58) in the South, where PWSs reported chloramine usage as a disinfectant compared with those PWSs who did not (Table 3B). We also observed an increase of 18% (1.01, 1.36) in the Midwest, where PWSs reported chlorine usage compared with PWSs that did not, and an increase of 24% (1.01, 1.53) in the West, where PWSs reported hypochlorite usage. In the CF analysis, we observed a 35% (1.09, 1.67) increase in the odds of NTM infection in the South, where PWSs reported chloramine usage as a disinfectant compared with those who did not report such usage (Table 3A).

We also observed that increasing precipitation in the Midwest increased risk of NTM PI in both populations. The number of flood warnings was not significantly associated with NTM PI. Supplementary Table 3A & 3B show results for all model covariates, including demographic variables, climate variables, interaction terms, and source water type. Supplementary Table 4 describes Mycobacterium avium Complex (MAC) and Mycobacterium abscessus specific modeling results for pwCF.

Estimated county-level risk of NTM infection

We estimated the nationwide county-level risk of NTM infection among pwCF (Fig. 2A) and among Medicare recipients (Fig. 2B) based on our models (Table 3). For NTM PI among pwCF (Fig. 2A), we observed counties with the highest risk of infection in Western states, particularly in central and southern California, southern Nevada, southern Arizona, and throughout the Rocky Mountain states. We also observed a high risk of infection in certain counties in Kansas, and throughout the South, particularly in Florida, Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Louisiana, and along the Eastern Seaboard. For NTM infection among Medicare recipients (Fig. 2B), counties with the highest risk of infection were located throughout the South, particularly in Florida, Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and along the Eastern Seaboard, as well as in central and southern California, southern Nevada, and southern Arizona.

Discussion

In this study, we reported significant associations between Mo and V in PWSs and NTM PI risk in the US. Moreover, similar associations were observed in two high-risk yet distinct populations. In both the CF and Medicare populations, Mo concentrations in the West and V concentrations in the South were strongly associated with NTM PI. For Medicare, we observed that V was also a significant risk factor for NTM PI in the Midwest and the West. In the South, we observed that Cr was protective for NTM PI. For CF, while the significant associations were limited to the South and West, V in the Midwest had a borderline risk effect, and with a larger sample size, may have achieved statistical significance, which would have been consistent with the Medicare results in this region.

Earlier work has identified hot spots of NTM across the US [19]. In particular, counties in Louisiana were identified as hot spots for NTM pulmonary disease [19]. This finding was consistent with other reports showing that NTM are found in high numbers in samples of peat-rich soils and acidic, brown water coastal swamps that are prevalent in Louisiana [16]. Epidemiologic studies of NTM PI risk in Colorado [20, 21], Hawai’i [23], Oregon [22], and a subnational analysis of the US found that NTM PI risk was positively associated with Mo and/or V concentrations in source water (i.e., streams, rivers, reservoirs, springs, groundwater) which supply public drinking water systems.

In this study, we focused on public drinking water systems because the vast majority of the US population (86%) relies on public water supplies for their drinking water [35]. In the US, a population-based survey from the 1990s found that an estimated 87% of time was spent indoors [36], therefore, household water is an important source of exposure [8, 9, 37,38,39,40]. Drinking water, or ‘tap water’, originates from upstream bodies of water that are either surface water or groundwater, otherwise known as source water, which then becomes the water supply for PWSs. Between the source and the tap, distribution systems connect water treatment facilities to premise plumbing through miles of underground pipes, storage facilities, and pumps. In the UCMR 3 dataset, trace metals were measured at entry points to the distribution system as well as at the distribution system maximum residence time sampling locations (Fig. 3). Thus, we used distribution system water data, which directly represents the trace metal content of treated water that flows from household water taps.

Bull Run Water Treatment. Water Quality Report. West Slope Water District. 2019; http:www.wswd.org/document_center/Water%20Quality/2019%20Water%20Quality%20Report.pdf. Accessed 25 April 2020.

Trace metals, Cr, Co, Mo, Sr, and V, are naturally occurring and are abundant throughout the earth’s crust [41]. These metals are considered trace elements because they are present in the environment at trace concentrations, as well as being essential and nonessential elements for human, animal, and plant life [42]. While natural environmental changes, such as rock weathering, soil erosion, and volcanic eruptions, contribute to the release of trace metals into our waterways, anthropogenic activities are also a major source of environmental contamination and human exposure to trace metals. Industrial activities, such as mine drainage, oil/gas and coal combustion, metal-based industrial production, and agricultural runoff, release large amounts of trace metals into the environment. The release of trace metals from industrial sources may occur in localized areas where trace metal concentrations become elevated and ultimately travel downstream to nearby waterways.

Region-specific characteristics of soil and water, as well as engineered water systems, including biofilms that form in hospital and public drinking water supplies, contribute to increased concentrations of NTM, leading to greater potential for NTM exposure and infection. Herein, we document that the distribution of NTM PI risk across US counties is non-uniform, distinctive, and unique.

To better understand potential environmental influences on NTM PI risk, we examined selected counties from Fig. 2A, B with respect to probable geogenic (factors that originate from geological sources) and anthropogenic V or Mo sources. Previously we focused on the naturally occurring effects of V and Mo on NTM PI risk [24]. Here, we focus our discussion on the anthropogenic sources of Mo and V with the caveat that it is sometimes difficult to separate geogenic from anthropogenic sources of metals.

Case studies

The counties highlighted below represent the two highest categories of risk for NTM PI having elevated concentrations of V and Mo metals in their water sources. Two cases are examined as illustrated in Fig. 4A, B.

Selected high-risk counties in A Selected high-risk counties (parishes) in Louisiana are shown in solid green. Yellow patterns are mapped clay-rich bedrock and sediments (Horton, 2017) known or suspected to contain high transition metal contents. Blue polygons or patches are known oil fields and appear green where they coincide with clay-rich material. Large magenta dots are oil refineries, including several in nearby states. B A map of the Colorado River and major tributaries. Municipalities and unincorporated areas using Colorado River water are indicated in blue patterns (website below), along with high-risk counties in red, creating purple regions where they overlap. See text for discussion. https://coloradoriverbasin-lincolninstitute.hub.arcgis.com/. Accessed 22 Jan 2024. Horton JD, San Juan CA, Stoeser DB. The State Geologic Map Compilation (SGMC) geodatabase of the conterminous United States. Data Series 1052. Available from: https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/ds1052.

Louisiana & Oil Refineries

A cluster of high-risk counties for NTM was observed in southern Louisiana in the vicinity of the Mississippi River delta (Fig. 4A). Prominent near-surface geological features of the state are widespread clay deposits and a complex interconnected system of streams, wetlands, and lakes. Ho et al [43]. (2019) noted that groundwater discharge to the Gulf of Mexico locally influences V budgets, where releases of V and Mo were associated with reducing conditions [44, 45]. In addition, significant contamination of soils with V was reported due to flooding associated with Hurricane Katrina in 2007 [46].

Twenty-one oil refineries producing nearly half of the nation’s distillates are located in Louisiana [46]. Overall, more than 100 petrochemical plants are found along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans [47]. V is known to occur in elevated concentrations in certain types of oil products and their distillates [48] and is emitted from steel mills, power plants, and oil refineries as well as through fossil fuel combustion, sewage sludge,e and fertilizers. Most of the high-risk counties for NTM PI are in the vicinity of these refineries. Mo releases are associated with mining and smelting, fossil fuel combustion, waste incineration, and fertilizers [49, 50]. The controls on V and Mo levels in domestic water supplies are less clear but likely involve both natural and anthropogenic sources.

Colorado River drainage & water transport

Lipner et al. [24] noted that water transferred from one surface drainage system to another area can confound relationships of geogenic sources to disease, in particular, water from the Colorado River. Colorado is a major producer of Mo, and mines along with their tailings and spoil rock occur within drainages contributing to the Colorado River, as well as draining into the South Platte. As such, there may be both geogenic and anthropogenic sources of Mo from the extractive industries of Colorado.

Here, we examine the case of water exports through water development projects. Instead of local geogenic or anthropogenic sources of V and Mo being important, imported sources of potable water may control the risk. Figure 4B illustrates the spatial relationship between high-risk counties and areas where Colorado River water is both exported and used within the basin.

The high-risk county (Yuma) in extreme southwest Arizona is adjacent to the Colorado River and has a major tributary (Gila River) that transects it. Yuma City, Arizona, for example, obtains its water from the Colorado River [51]. Las Vegas, Nevada, in Clark County imports the large majority of its water from the Colorado River [52] through a system of tunnels from Lake Mead [53], a large reservoir on the Colorado River. Elsewhere, water exported from the Colorado River basin is clearly associated with elevated risk in heavily populated southern California. Indeed, it is unclear how much of the hazard along the Arkansas River corridor is due to local geogenic sources, urbanization (Denver metropolitan area), and agriculture versus how much is due to exported Colorado River water.

Trace metals and NTM infection hypotheses

We propose two hypotheses to explain the observed distribution of NTM PI risk and suggest potentially causal mechanisms.

Exposure to Mo and V increase the abundance of NTM in public drinking water

We hypothesize that NTM numbers in public drinking water are influenced by the concentration and availability of metal ions. Specifically, water from counties with a high risk of NTM PI would also have high concentrations of Mo or V. Mo would serve as an essential metal because public drinking water is nutrient-poor and low in organic nitrogen but has available nitrate. MAC can use nitrate as a sole source of nitrogen (i.e., nitrate assimilation), due to the presence of the enzyme nitrate reductase, a Mo-dependent enzyme. We hypothesize that the enzyme may also use V to replace Mo. Nitrate reductase reduces nitrate to nitrite, and that pathway ultimately leads to the formation of ammonia, which is used to aminate fatty acids, producing amino acids used for protein synthesis [54]. The presence of Mo or V in public drinking water may provide the metal-cofactor for the use of nitrate as the sole nitrogen source.

If environmental source water in certain regions has elevated trace metal concentrations and PWSs draw water from that location, it will introduce a higher abundance of NTM into the water distribution system, thereby increasing the risk of infection. We hypothesize that environmental source water with a high abundance of NTM could initiate the presence of NTM in the water distribution system compared with PWSs drawing from source water with low NTM abundance. This effect may explain why certain counties have a greater infection risk than others.

Water distribution pipework may have little effect on the supplied drinking water trace metal concentrations. Smedley et al. [55] compared old and new houses, pre-flush and post-flush samples, tap water, and water samples from their respective source water in England and Wales, and found a negligible effect on the Mo concentrations of the water samples. As a result, the observed Mo concentrations in public drinking water systems are likely due to the concentrations of Mo in the source water. We did not find literature to assess the potential changes of V concentrations due to pipework materials.

Exposure to Mo and V via water consumption increases human susceptibility to NTM PI

Mo and/or V may also influence host susceptibility by altering the ability of the human host to respond to or contain infection. A Korean study [56] reported that pulmonary NTM patients had significantly higher Mo concentrations in their blood serum compared with control patients. In a Sicilian study [57], authors examined trace metal concentrations in drinking water and in urine of residents living in basaltic volcanic regions (with naturally occurring elevated V concentrations) compared with non-volcanic regions. They reported that mean V concentrations in drinking water were significantly correlated with mean urinary V concentrations of residents in volcanic areas compared with non-volcanic areas. Thus, patients who live in regions with elevated Mo and/or V levels in their drinking water may be chronically exposed and could have increased susceptibility to infection and/or rapid progression of disease.

Interaction effect

Importantly in the Medicare analysis, a significant interaction effect between Mo and V was observed in the South, where at high fixed Mo concentrations (> 90th percentile), the rate of NTM cases decreased as V concentrations increased. However, at lower fixed Mo concentrations (minimum molybdenum concentration to 90th percentile), the rate of NTM cases increased as V concentrations increased (Supplementary Table 2B; Fig. 5). Importantly, out of 848 counties in the South, 491 counties had molybdenum values below the MRL and were therefore assigned the 0.707 μg/L value (Supplementary Table 2B). Previous literature has shown that NTM growth was stimulated by low concentrations of heavy metal salts, while growth was inhibited by high concentrations of some metals, and tolerated by high concentrations of other metals, including mercury and cadmium [58]. Although Mo and V were not among the metals examined in Falkinham et al. [58], we hypothesize, as described above, that in conditions where Mo is at low availability, NTM may use V in place of Mo as an essential co-factor for metabolism [59]. For this reason, we included an interaction term for Mo and V in our regression models, which proved to be statistically significant in the South of the Medicare analysis. No significant interaction effects were observed in the CF analysis. Further research is needed to more fully explore the relationship between Mo, V, and NTM PI risk.

Lines on the plot represent fixed low, moderate, and high molybdenum concentrations in the distribution system water. The corresponding-colored regions represent confidence intervals for each line. The x-axis represents increasing vanadium concentrations in the distribution system water. The y-axis represents the expected number of NTM cases among Medicare recipients in the South.

Disinfectant use

Chloramine use showed a consistent risk effect for NTM PI in multiple U.S. regions. These results are in line with the current literature. King et al. [6] reported that MAC detection frequencies were higher in chloramine-treated surface water than in chlorine-treated surface water. Donohue et al. [60] reported higher M. avium detection frequencies in chloramine-treated water than chlorine-treated water. Pfaller et al. [61] also reported that MAC was detected more frequently in surface water samples that were treated with chloramine than in those that were treated with chlorine. This association may be a manifestation of nitrification to produce nitrate in water treatment plants, where Mo (or potentially V as a substitute), as a cofactor of nitrate reductase, would then stimulate NTM numbers. While we also observed that chlorine use in the Midwest and hypochlorite use in the West were significant risk factors for NTM PI among Medicare recipients, the effect estimates were not as strong as those of chloramine use.

Our study had several limitations. The study population included patients over a longer time frame (2010–2019) than the years in which data collection for trace metals had occurred (2013–2015). However, when we analyzed the concentrations of trace metals by year, we did not find much fluctuation. Therefore, to maximize power, we used all available patient data and proceeded under the assumption that trace metal concentrations would remain fairly constant over the nine-year span. In addition, upon examining the raw data, we became aware that PWSs did not always report all the zip codes served. As a result, some counties may not have been included in our analysis because of a lack of trace metal data. However, rather than exclude disinfectants from our analysis, we retained the disinfectant variable in our models since it represents the real-world scenario of drinking water treatment. Supplementary Table 5 shows the results when disinfectant type was excluded from our analysis.

Our study also had several strengths. First, by using two high-risk populations for NTM PI, we had greater statistical power to identify exposures associated with NTM PI. Second, while previously we observed these associations using environmental source water, most people are not directly exposed to environmental water except through recreation. So, the question remained: would we observe these associations when using treated water from the distribution systems that serve residential homes, office buildings, hospitals, and industry? As a result, the trace metal variables in our models are measured from treated water, which people have direct exposure to in their homes, lending further support for a potentially causal relationship.

Another strength of our study comes from incorporating precipitation and flood data into our analysis. We controlled for these variables because they are likely to affect the trace metal content in the water supply, since greater precipitation and flooding can easily transport labile metals in soil and sediment into streams. Precipitation and floods have also been linked to increased risk of NTM PI [62, 63].

While our findings underscore a potential causal relationship between trace metals in the water supply and NTM PI risk, our work has raised important research questions. First and foremost, this study cannot differentiate between the influence of trace metals on bacterial growth and/or pathogenicity versus their influence on infection susceptibility and/or disease progression in the human host. Further, we have not examined a dose-response relationship between metals and infection. Environmental investigations of well and stream waters, urban runoff, irrigation return, and oil refinery emissions in selected high- and low-risk counties may permit estimation of the contribution of geogenic and anthropogenic sources to NTM infection. Finally, our research may lead to the monitoring of selected trace metals in both drinking water and susceptible populations, which could ultimately be incorporated into a framework for NTM prevention efforts.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under a Data Use Agreement for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

References

Prevots DR, Marshall JE, Wagner D, Morimoto K. Global epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: a review. Clin Chest Med. 2023;44:675–721.

Collier SA, Deng L, Adam EA, Benedict KM, Beshearse EM, Blackstock AJ, et al. Estimate of burden and direct healthcare cost of infectious waterborne disease in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:140–9.

Marshall JE, Mercaldo RA, Lipner EM, Prevots DR. Incidence of nontuberculous mycobacteria infections among persons with cystic fibrosis in the United States (2010-2019). BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23:489.

Bents SJ, Mercaldo RA, Powell C, Henkle E, Marras TK, Prevots DR. Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM PD) incidence trends in the United States, 2010-2019. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24:1094.

Glassmeyer ST, Furlong ET, Kolpin DW, Batt AL, Benson R, Boone JS, et al. Nationwide reconnaissance of contaminants of emerging concern in source and treated drinking waters of the United States. Sci Total Environ. 2017;581-2:909–22.

King DN, Donohue MJ, Vesper SJ, Villegas EN, Ware MW, Vogel ME, et al. Microbial pathogens in source and treated waters from drinking water treatment plants in the United States and implications for human health. Sci Total Environ. 2016;562:987–95.

Falkinham JO 3rd, Norton CD, LeChevallier MW. Factors influencing numbers of Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other Mycobacteria in drinking water distribution systems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:1225–31.

Lande L, Alexander DC, Wallace RJ Jr., Kwait R, Iakhiaeva E, Williams M, et al. Mycobacterium avium in Community and Household Water, Suburban Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, 2010-2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25:473–81.

Falkinham JO 3rd. Nontuberculous mycobacteria from household plumbing of patients with nontuberculous mycobacteria disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:419–24.

Haig SJ, Kotlarz N, LiPuma JJ, Raskin L. A high-throughput approach for identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria in drinking water reveals relationship between water age and mycobacterium avium. mBio. 2018;9.

Gebert MJ, Delgado-Baquerizo M, Oliverio AM, Webster TM, Nichols LM, Honda JR, et al. Ecological analyses of mycobacteria in showerhead biofilms and their relevance to human health. mBio. 2018;9.

Shen Y, Haig SJ, Prussin AJ 2nd, LiPuma JJ, Marr LC, et al. Shower water contributes viable nontuberculous mycobacteria to indoor air. PNAS Nexus. 2022;1:pgac145.

Gerdes ME, Miko S, Kunz JM, Hannapel EJ, Hlavsa MC, Hughes MJ, et al. Estimating Waterborne Infectious Disease Burden by Exposure Route, United States, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:1357–66.

Falkinham JO, 3rd. Ecology of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria. Microorganisms. 2021;9.

George KL, Parker BC, Gruft H, Falkinham JO 3rd. Epidemiology of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. II. Growth and survival in natural waters. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;122:89–94.

Kirschner RA Jr., Parker BC, Falkinham JO 3rd. Epidemiology of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and Mycobacterium scrofulaceum in acid, brown-water swamps of the southeastern United States and their association with environmental variables. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:271–5.

Strollo SE, Adjemian J, Adjemian MK, Prevots DR. The burden of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in the United States. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1458–64.

Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Seitz AE, Holland SM, Prevots DR. Prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in U.S. Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:881–6.

Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Seitz AE, Falkinham JO 3rd, Holland SM, et al. Spatial clusters of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:553–8.

Lipner EM, French J, Bern CR, Walton-Day K, Knox D, Strong M, et al. Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease and Molybdenum in Colorado Watersheds. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17.

Lipner EM, Crooks JL, French J, Strong M, Nick JA, Prevots DR. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection and environmental molybdenum in persons with cystic fibrosis: a case–control study in Colorado. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology. 2021.

Lipner EM, French JP, Falkinham JO, 3rd, Crooks JL, Mercaldo RA, et al. NTM Infection Risk and Trace Metals in Surface Water: A Population-Based Ecologic Epidemiologic Study in Oregon. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021.

Lipner EM, French JP, Nelson S, Falkinham III JO, Mercaldo RA, Blakney RA, et al. Vanadium in groundwater aquifers increases the risk of MAC pulmonary infection in O’ahu, Hawai’i. Environ Epidemiol. 2022;6:e220.

Lipner EM, French JP, Mercaldo RA, Nelson S, Zelazny AM, Marshall JE, et al. The risk of pulmonary NTM infections and water-quality constituents among persons with cystic fibrosis in the United States, 2010-2019. Environ Epidemiol. 2023;7:e266.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. The Third Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 3). In: Office of Water, editor. 2016.

Knapp EAFA, Goss CH, Sewall A, Ostrenga J, Dowd C, Elbert A, et al. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry: Design and Methods of a National Observational Disease Registry. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;3:1173–9.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2024 [Available from: https://www.cms.gov/data-research.

Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied Statistics with S. Fourth ed. New York: Springer; 2002.

Wei T, Simko V. R package ‘corrplot’: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix. 2024. Version 0.95

Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2022.

Fox J, Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd edition. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. 2019.

Fox J. Effect Displays in R for Generalised Linear Models. J Stat Softw. 2003;8:1–27.

Ravalli F, Yu Y, Bostick BC, Chillrud SN, Schilling K, Basu A, et al. Sociodemographic inequalities in uranium and other metals in community water systems across the USA, 2006-11: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Planet Health. 2022;6:e320–e30.

Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J. 2008;50:346–63.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Hydraulic Fracturing for Oil and Gas: Impacts from the Hydraulic Fracturing Water Cycle on Drinking Water Resources in the United States. Executive Summary. In: Development Office of Research and Development, editor. Washington DC2016.

Klepeis NE, Nelson WC, Ott WR, Robinson JP, Tsang AM, Switzer P, et al. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): a resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2001;11:231–52.

Nishiuchi Y, Maekura R, Kitada S, Tamaru A, Taguri T, Kira Y, et al. The recovery of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAC) from the residential bathrooms of patients with pulmonary MAC. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:347–51.

Thomson R, Tolson C, Carter R, Coulter C, Huygens F, Hargreaves M. Isolation of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) from household water and shower aerosols in patients with pulmonary disease caused by NTM. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:3006–11.

Thomson R, Tolson C, Sidjabat H, Huygens F, Hargreaves M. Mycobacterium abscessus isolated from municipal water - a potential source of human infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:241.

Thomson RM, Carter R, Tolson C, Coulter C, Huygens F, Hargreaves M. Factors associated with the isolation of Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) from a large municipal water system in Brisbane, Australia. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:89.

Taylor SR, McLennan SM. The geochemical evolution of the continental crust. Rev Geophys. 1995;33:241–65.

Mehri A. Trace Elements in Human Nutrition (II) - An Update. Int J Prev Med. 2020;11:2.

Ho P, Shim MJ, Howden SD, Shiller AM. Temporal and spatial distributions of nutrients and trace elements (Ba, Cs, Cr, Fe, Mn, Mo, U, V and Re) in Mississippi coastal waters: Influence of hypoxia, submarine groundwater discharge, and episodic events. Cont Shelf Res. 2019;175:53–69.

Shaheen SM, Rinklebe J, Frohne T, White JR, DeLaune RD. Redox effects on release kinetics of arsenic, cadmium, cobalt, and vanadium in Wax Lake Deltaic freshwater marsh soils. Chemosphere. 2016;150:740–8.

Telfeyan K, Breaux A, Kim J, Kolker AS, Cable JE, Johannesson KH. Cycling of oxyanion-forming trace elements in groundwaters from a freshwater deltaic marsh. Estuar, Coast Shelf Sci. 2018;204:236–63.

Su T, Shu S, Shi H, Wang J, Adams C, Witt EC. Distribution of toxic trace elements in soil/sediment in post-Katrina New Orleans and the Louisiana Delta. Environ Pollut. 2008;156:944–50.

Meaders JS. Health impacts of petrochemical expansion in Louisiana and realistic options for affected communities. Tulane Environ Law J. 2021;34:113–47.

Hopke PK, Dai Q, Li L, Feng Y. Global review of recent source apportionments for airborne particulate matter. Sci Total Environ. 2020;740:140091.

Moreno T, Querol X, Alastuey A, Gibbons W. Identification of FCC refinery atmospheric pollution events using lanthanoid-and vanadium-bearing aerosols. Atmos Environ. 2008;42:7851–61.

Putman AL, Jones DK, Blakowski MA, DiViesti D, Hynek SA, Fernandez DP, et al. Industrial particulate pollution and historical land use contribute metals of concern to dust deposited in neighborhoods along the Wasatch Front, UT, USA. Geohealth. 6:e2022GH000671.

COY (City of Yuma) 2023 [Available from: https://www.yumaaz.gov/government/utilities/water-conservation.

SNWA (Southern Nevada Water Authority) 2023 [Available from: https://www.snwa.com/water-resources/where-water-comes-from/index.html.

Hurt J, Cimiotti C. Lake Mead Intake No. 3. Engineering. 2017;3:880–7.

Luque-Almagro VM, Gates AJ, Moreno-Vivian C, Ferguson SJ, Richardson DJ, Roldan MD. Bacterial nitrate assimilation: gene distribution and regulation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:1838–43.

Smedley PL, Cooper DM, Lapworth DJ. Molybdenum distributions and variability in drinking water from England and Wales. Environ Monit Assess. 2014;186:6403–16.

Oh J, Shin SH, Choi R, Kim S, Park HD, Kim SY, et al. Assessment of 7 trace elements in serum of patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2019;53:84–90.

Malandrino P, Russo M, Ronchi A, Minoia C, Cataldo D, Regalbuto C, et al. Increased thyroid cancer incidence in a basaltic volcanic area is associated with non-anthropogenic pollution and biocontamination. Endocrine. 2016;53:471–9.

Falkinham JO 3rd, George KL, Parker BC, Gruft H. In vitro susceptibility of human and environmental isolates of Mycobacterium avium, M. intracellulare, and M. scrofulaceum to heavy-metal salts and oxyanions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;25:137–9.

Darnajoux R, Magain N, Renaudin M, Lutzoni F, Bellenger JP, Zhang X. Molybdenum threshold for ecosystem scale alternative vanadium nitrogenase activity in boreal forests. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:24682–8.

Donohue MJ, Vesper S, Mistry J, Donohue JM. Impact of Chlorine and Chloramine on the Detection and Quantification of Legionella pneumophila and Mycobacterium Species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2019;85.

Pfaller S, King D, Mistry JH, Donohue M. Occurrence revisited: Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare in potable water in the USA. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022;106:2715–27.

Foote SL, Lipner EM, Prevots DR, Ricotta EE. Environmental predictors of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) sputum positivity among persons with cystic fibrosis in the state of Florida. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0259964.

Mejia-Chew C, Chavez MA, Lian M, McKee A, Garrett L, Bailey TC, et al. Spatial epidemiologic analysis and risk factors for nontuberculous mycobacteria infections, Missouri, USA, 2008-2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:1540–6.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation for the use of CF Foundation Patient Registry data to conduct this study. Additionally, we would like to thank the patients, care providers, and clinic coordinators at CF Centers throughout the United States for their contributions to the CF Foundation Patient Registry.

Funding

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The contributions of the NIH authors were made as part of their official duties as NIH federal employees, are in compliance with agency policy requirements, and are considered Works of the United States Government. However, the findings and conclusions presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Open access funding provided by the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: EML, DRP; Methodology: EML, CP, JRF, JPF; Data acquisition: EML, CP, SN, RAM; Statistical analysis: CP, JRF, JPF; Drafting of the manuscript: EML, JOF, SN; Critical revision of the manuscript: JRF, JPF, RAM, DRP.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations by the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) Office of Human Subjects Research Protection (OHSRP). The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the NIH follows all international ethics rules, regulations, and standards. This research was reviewed by the NIH OHSRP, which determined that analyses of CF and CMS data was “not human subjects research”, under the 2018 HHS Common Rule (45 CFR 46.102(e) [1](ii), 45 CFR 46.116(b)[9](i)), because of the use of deidentified data and, accordingly, exempt from IRB review.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lipner, E.M., Powell, C., Nelson, S. et al. The risk of NTM pulmonary infection associated with trace metal exposure from public distribution system water in the United States. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-025-00807-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-025-00807-w