Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is a highly prevalent disease. Chemical exposures may contribute to breast cancer risk, though most chemicals to which humans are exposed remain understudied in breast cancer research.

Objective

This study tested the hypothesis that environmental chemicals present in households of women who do and do not develop breast cancer will have differential abundance, and that chemical profiles relate to self-reported sources of exposures.

Methods

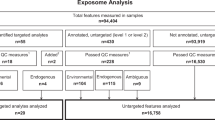

Household dust wipe samples were collected at enrollment in the Sister Study cohort in 2003–2009. We evaluated a subsample of Sister Study participants who developed hormone receptor positive breast cancer within 10 years after enrollment (N = 40, “cases”) and who remained breast cancer free during the same period (N = 40, “controls”). Dust wipes were analyzed via liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry coupled with database mining approaches. Participants self-reported personal care product usage and proximity to environmental pollution sources. Frequent itemset mining (FIM) was used to evaluate chemical occurrence and associations with questionnaire data.

Results

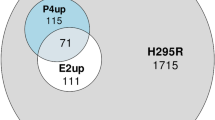

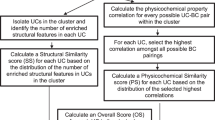

In the dust wipe samples, there were 189 features annotated to potential chemicals that significantly differed (adjusted p < 0.1) in abundance between cases and controls. Example chemicals included suspected endocrine disruptors 23-(Nonylphenoxy)-3,6,9,12,15,18,21-heptaoxatricosan-1-ol, triethanolamine, and thiabendazole. Analysis of questionnaire data identified the chemical 6-benzyl-2-[bis[(2S)-2-aminopropanoyl]amino]-3-methylphenyl] (2S)-2-[[(2S)-2-(3-hydroxyhexanoylamino)-3-methylbutanoyl]amino]-3-methylbutanoate to be of high interest due to its link, derived through FIM, to 45 exposure scenarios, largely described by elevated personal care product usage habits.

Significance

Overall, this study builds the evidence base for understudied chemicals in everyday household environments that may alter breast cancer risk. Coupling chemical analysis results with participant survey data highlighted behaviors and environmental factors that may influence exposures to these chemicals, informing the design of future investigations to better understand sources of breast cancer risk in women.

Impact

-

There is much to understand about household exposures that can affect breast cancer risk. This study aimed to generate a novel household exposomic dataset leveraging dust wipe samples from the Sister Study cohort. A subset of the detected chemicals was found to be differentially detected in the houses of women who developed breast cancer. Additional analysis of self-reported questionnaire data demonstrated linkages between increased personal care product usage and elevated chemical abundance. The results of this study lend important insights into understudied chemicals in the home that may alter breast cancer risk and possible sources of exposure to these substances.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data, analysis scripts, and results from this analysis are publicly available. Analysis scripts, datasets, and results are organized on the Rager lab Github site (https://github.com/Ragerlab) and Dataverse (https://dataverse.unc.edu/dataverse/ragerlab).

References

Smolarz B, Nowak AZ, Romanowicz H. Breast cancer—Epidemiology, classification, pathogenesis and treatment (review of literature). Cancers. 2022;14:2569.

Apostolou P, Fostira F. Hereditary breast cancer: the era of new susceptibility genes. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:747318.

IBCERCC. Breast Cancer and the Environment: Prioritizing Prevention. Report of the Interagency Breast Cancer and Environmental Research Coordinating Committee (IBCERCC) 2013 [Available from: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/about/assets/docs/ibcercc_full_508.pdf.

IOM. Breast Cancer and the Environment: A Life Course Approach: The Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academies; 2012 [Available from: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/13263/breast-cancer-and-the-environment-a-life-course-approach.

Gray JM, Rasanayagam S, Engel C, Rizzo J. State of the evidence 2017: an update on the connection between breast cancer and the environment. Environ Health. 2017;16:94.

Hiatt RA, Brody JG. Environmental determinants of breast cancer. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:113–33.

Rodgers KM, Udesky JO, Rudel RA, Brody JG. Environmental chemicals and breast cancer: an updated review of epidemiological literature informed by biological mechanisms. Environ Res. 2018;160:152–82.

Schmeisser S, Miccoli A, von Bergen M, Berggren E, Braeuning A, Busch W, et al. New approach methodologies in human regulatory toxicology - Not if, but how and when!. Environ Int. 2023;178:108082.

Wambaugh JF, Bare JC, Carignan CC, Dionisio KL, Dodson RE, Jolliet O, et al. New approach methodologies for exposure science. Curr Opin Toxicol. 2019;15:76–92.

Wambaugh JF, Rager JE. Exposure forecasting - ExpoCast - for data-poor chemicals in commerce and the environment. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2022;32:783–93.

Johnson KS, Conant EF, Soo MS. Molecular subtypes of breast cancer: a review for breast radiologists. J Breast Imaging. 2021;3:12–24.

Tsang JYS, Tse GM. Molecular classification of breast cancer. Adv Anat Pathol. 2020;27:27–35.

Eve L, Fervers B, Le Romancer M, Etienne-Selloum N. Exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals and risk of breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:9139.

Rager JE, Strynar MJ, Liang S, McMahen RL, Richard AM, Grulke CM, et al. Linking high resolution mass spectrometry data with exposure and toxicity forecasts to advance high-throughput environmental monitoring. Environ Int. 2016;88:269–80.

Han Q, Liu Y, Feng X, Mao P, Sun A, Wang M, et al. Pollution effect assessment of industrial activities on potentially toxic metal distribution in windowsill dust and surface soil in central China. Sci Total Environ. 2021;759:144023.

Dong T, Zhang Y, Jia S, Shang H, Fang W, Chen D, et al. Human indoor exposome of chemicals in dust and risk prioritization Using EPA’s ToxCast database. Environ Sci Technol. 2019;53:7045–54.

Whitehead T, Metayer C, Buffler P, Rappaport SM. Estimating exposures to indoor contaminants using residential dust. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2011;21:549–64.

Dubocq F, Kärrman A, Gustavsson J, Wang T. Comprehensive chemical characterization of indoor dust by target, suspect screening and nontarget analysis using LC-HRMS and GC-HRMS. Environ Pollut. 2021;276:116701.

Barupal DK, Baygi SF, Wright RO, Arora M. Data processing thresholds for abundance and sparsity and missed biological insights in an untargeted chemical analysis of blood specimens for exposomics. Front Public Health. 2021;9:653599.

Di Minno A, Gelzo M, Stornaiuolo M, Ruoppolo M, Castaldo G. The evolving landscape of untargeted metabolomics. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;31:1645–52.

Sandler DP, Hodgson ME, Deming-Halverson SL, Juras PS, D’Aloisio AA, Suarez LM, et al. The Sister Study Cohort: baseline methods and participant characteristics. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125:127003.

Moschet C, Anumol T, Lew BM, Bennett DH, Young TM. Household dust as a repository of chemical accumulation: new insights from a comprehensive high-resolution mass spectrometric study. Environ Sci Technol. 2018;52:2878–87.

Najdekr L, Blanco GR, Dunn WB. Collection of untargeted metabolomic data for mammalian urine applying hilic and reversed phase ultra performance liquid chromatography methods coupled to a Q exactive mass spectrometer. In: Bhattacharya SK, editor. Metabolomics: methods and protocols. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2019. p. 1–15.

Hsiao YC, Matulewicz RS, Sherman SE, Jaspers I, Weitzman ML, Gordon T, et al. Untargeted metabolomics to characterize the urinary chemical landscape of E-cigarette users. Chem Res Toxicol. 2023;36:630–42.

Hsiao YC, Yang Y, Liu CW, Peng J, Feng J, Zhao H, et al. Multiomics to characterize the molecular events underlying impaired glucose tolerance in FXR-knockout mice. J Proteome Res. 2024;23:3332–41.

Hsiao YC, Johnson G, Yang Y, Liu CW, Feng J, Zhao H, et al. Evaluation of neurological behavior alterations and metabolic changes in mice under chronic glyphosate exposure. Arch Toxicol. 2024;98:277–88.

Cheema AK, Li Y, Girgis M, Jayatilake M, Fatanmi OO, Wise SY, et al. Alterations in tissue metabolite profiles with amifostine-prophylaxed mice exposed to gamma radiation. Metabolites. 2020;10:211.

Chambers MC, Maclean B, Burke R, Amodei D, Ruderman DL, Neumann S, et al. A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:918–20.

Wei R, Wang J, Jia E, Chen T, Ni Y, Jia W. GSimp: a Gibbs sampler based left-censored missing value imputation approach for metabolomics studies. PLoS Comput Biol. 2018;14:e1005973.

Wei R, Wang J, Su M, Jia E, Chen S, Chen T, et al. Missing value imputation approach for mass spectrometry-based metabolomics data. Sci Rep. 2018;8:663.

Hickman E, Frey J, Wylie A, Hartwell HJ, Herkert NJ, Short SJ, et al. Chemical and non-chemical stressors in a postpartum cohort through wristband and self report data: links between increased chemical burden, economic, and racial stress. Environ Int. 2024;191:108976.

Hao L, Wang J, Page D, Asthana S, Zetterberg H, Carlsson C, et al. Comparative evaluation of MS-based metabolomics software and its application to preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9291.

Pence HE, Williams A. ChemSpider: an online chemical information resource. J Chem Educ. 2010;87:1123–4.

Vinaixa M, Schymanski EL, Neumann S, Navarro M, Salek RM, Yanes O. Mass spectral databases for LC/MS- and GC/MS-based metabolomics: State of the field and future prospects. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. 2016;78:23–35.

Cole SR, Frangakis CE. The consistency statement in causal inference: a definition or an assumption? Epidemiology. 2009;20:3–5.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57:289–300.

EPA US. CompTox Chemicals Dashboard Batch Search 2024 [Available from: https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/batch-search.

Luna JM, Fournier-Viger P, Ventura S. Frequent itemset mining: a 25 years review. WIREs Data Min Knowl Discov. 2019;9:e1329.

Oki NO, Edwards SW. An integrative data mining approach to identifying adverse outcome pathway signatures. Toxicology. 2016;350-352:49–61.

Kapraun DF, Wambaugh JF, Ring CL, Tornero-Velez R, Setzer RW. A Method for identifying prevalent chemical combinations in the U.S. population. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125:087017.

Naulaerts S, Meysman P, Bittremieux W, Vu TN, Vanden Berghe W, Goethals B, et al. A primer to frequent itemset mining for bioinformatics. Brief Bioinform. 2015;16:216–31.

Hahsler M, Grün B, Hornik K. arules - A computational environment for mining association rules and frequent item sets. J Stat Softw. 2005;14:1–25.

Schymanski EL, Jeon J, Gulde R, Fenner K, Ruff M, Singer HP, et al. Identifying small molecules via high resolution mass spectrometry: communicating confidence. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:2097–8.

Sumner LW, Amberg A, Barrett D, Beale MH, Beger R, Daykin CA, et al. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis Chemical Analysis Working Group (CAWG) Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI). Metabolomics. 2007;3:211–21.

EPA US. 3,6,9,12,15,18,21,24,27-Nonaoxanonacosane-1,29-diol 5579-66-8 | DTXSID50204354. Product Use and Categories 2024 [Available from: https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/chemical/product-use-categories/DTXSID50204354.

NCBI. National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem 2-Acetamido-2-deoxy-alpha-D-glucopyranose (compound) 2024 [Available from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/82313.

ECHA. European Chemicals Agency. Substance InfoCard 23-(nonylphenoxy)-3,6,9,12,15,18,21-heptaoxatricosan-1-ol 2023 [Available from: https://echa.europa.eu/substance-information/-/substanceinfo/100.043.888.

Sandrine AD, V. S109 | PARCEDC | List of 7074 potential endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) by PARC T4.2. In: Zenodo, editor. NORMAN-SLE-S109.0.1.0 ed2024.

Tighe M, Knaub C, Sisk M, Ngai M, Lieberman M, Peaslee G, et al. Validation of a screening kit to identify environmental lead hazards. Environ Res. 2020;181:108892.

Phillips KA, Wambaugh JF, Grulke CM, Dionisio KL, Isaacs KK. High-throughput screening of chemicals as functional substitutes using structure-based classification models. Green Chem. 2017;19:1063–74.

EPA US. 3,3’-(Phenylazanediyl)di(propane-1,2-diol) 57302-22-4 | DTXSID70972821. Exposure - Collected and Predicted Data on Functional Use 2024 [Available from: https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/chemical/chemical-functional-use/DTXSID70972821.

EPA US. 3-(propylcarbamoyl)propanoic Acid 61283-60-1 | DTXSID40398670. Exposure - Collected and Predicted Data on Functional Use 2024 [Available from: https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/chemical/chemical-functional-use/DTXSID40398670.

Meijer J, Lamoree M, Hamers T, Antignac J-P, Hutinet S, Debrauwer L, et al. An annotation database for chemicals of emerging concern in exposome research. Environ Int. 2021;152:106511.

Layland J, Carrick D, Lee M, Oldroyd K, Berry C. Adenosine: physiology, pharmacology, and clinical applications. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:581–91.

Hasko G, Pacher P. Regulation of macrophage function by adenosine. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:865–9.

Spicuzza L, Di Maria G, Polosa R. Adenosine in the airways: implications and applications. Eur J Pharm. 2006;533:77–88.

Marucci G, Buccioni M, Varlaro V, Volpini R, Amenta F. The possible role of the nucleoside adenosine in countering skin aging: a review. BioFactors. 2022;48:1027–35.

von der Ohe P, Aalizadeh, R. S13 | EUCOSMETICS | Combined Inventory of Ingredients Employed in Cosmetic Products (2000) and Revised Inventory (2006). In: Zenodo, editor. NORMAN-SLE-S13.0.1.3 ed2020.

Merighi S, Mirandola P, Milani D, Varani K, Gessi S, Klotz KN, et al. Adenosine receptors as mediators of both cell proliferation and cell death of cultured human melanoma cells. J Investig Dermatol. 2002;119:923–33.

Gessi S, Merighi S, Borea PA. Targeting adenosine receptors to prevent inflammatory skin diseases. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:553–4.

Oura H, Iino M, Nakazawa Y, Tajima M, Ideta R, Nakaya Y, et al. Adenosine increases anagen hair growth and thick hairs in Japanese women with female pattern hair loss: a pilot, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Dermatol. 2008;35:763–7.

EPA US. CompTox Chemicals Dashboard v2.5.3. Thiabendazole 148-79-8 | DTXSID0021337 2025 [Available from: https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/chemical/invitrodb/DTXSID0021337.

Fiume MM, Heldreth B, Bergfeld WF, Belsito DV, Hill RA, Klaassen CD, et al. Safety assessment of triethanolamine and triethanolamine-containing ingredients as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2013;32:59S–83S.

Chang C-J, O’Brien KM, Keil AP, Goldberg M, Taylor KW, Sandler DP, et al. Use of personal care product mixtures and incident hormone-sensitive cancers in the Sister Study: a U.S.-wide prospective cohort. Environ Int. 2024;183:108298.

Eberle CE, Sandler DP, Taylor KW, White AJ. Hair dye and chemical straightener use and breast cancer risk in a large US population of black and white women. Int J Cancer. 2020;147:383–91.

Terry MB, Michels KB, Brody JG, Byrne C, Chen S, Jerry DJ, et al. Environmental exposures during windows of susceptibility for breast cancer: a framework for prevention research. Breast Cancer Res. 2019;21:96.

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) training grant (T32ES007018) and the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) (Z01 ES 044005 to DPS and Z1AES103332 to AJW). Additional support was provided by the Institute for Environmental Health Solutions at the Gillings School of Global Public Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LEK: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, review and editing; YH: Formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, validation, writing—review and editing; EJ: Formal analysis, investigation, software, validation, writing—review and editing; LAE: Investigation, methodology, software, validation, visualization, writing—review and editing; DPS: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, writing—review and editing; HBN: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, writing—original draft, review and editing; KL: Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, software, validation, writing—review and editing; AJW: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, writing—original draft, review and editing, JER: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All participants provided written informed consent. All study activities were approved by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Institutional Review Board and performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Koval, L.E., Hsiao, YC., Jiang, E. et al. Environmental factors influencing hormone receptor positive breast cancer incidence: integrating chemical signatures from dust wipes with self-reported sources of exposure. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-025-00819-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-025-00819-6