Abstract

The association between remnant cholesterol (RC) and the risk of developing hypertension remains poorly elucidated. We analyzed China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study data (CHARLS, 2011–2020). RC was categorized into baseline RC, cumulative RC, and RC change. In Cohort 1 (n = 7474), baseline RC was measured at Wave 1, with incident hypertension identified during Waves 2–5. In Cohort 2 (n = 3956), cumulative RC was calculated using Waves 1 and 3 data, with hypertension assessed during Waves 4–5. Participants were divided into quartiles. Logistic regression was used to assess the association between RC and hypertension. Restricted cubic splines explored non-linear relationships. During follow-up, 2366 (31.7%) and 805 (20.3%) hypertension cases occurred in Cohorts 1 and 2, respectively. A non-linear association was found between baseline RC and hypertension, with an inflection point at 1.16 mmol/L. The highest RC quartile showed increased hypertension risk, with adjusted odds ratios (OR) of 1.52 (p < 0.001) for baseline RC and 1.39 (p = 0.004) for cumulative RC. RC change suggested potential increased risk, though not statistically significant. BMI and HbA1c partially mediated the RC-hypertension relationship, accounting for 36.94 and 7.2% of the total effect, respectively. These findings indicate that elevated baseline and cumulative RC levels are associated with an increased risk of new-onset hypertension in middle-aged and older adults, and that baseline RC levels and hypertension are non-linearly related, with an inflection point of 1.16 mmol/L. Additionally, this study found that BMI and HbA1c mediated the association between RC and incident hypertension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, the prevalence of hypertension among adults aged 30 to 79 has increased significantly over the past three decades, from 650 million to 1.28 billion, according to the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration analysis [1]. Hypertension is responsible for more than 8.5 million deaths worldwide each year and is a major risk factor for ischemic heart disease, stroke and kidney disease [1]. Furthermore, in China, the prevalence of hypertension has also risen markedly in recent years. The weighted prevalence among adults reached 31.6% in 2021–2022, representing an absolute increase of 8.4% compared with 2012–2015. Nevertheless, awareness, treatment, and control rates remain low at only 43.3, 38.7, and 12.9%, respectively [2, 3]. These findings underscore that hypertension continues to pose a serious public health challenge. Therefore, the early identification of risk factors and the timely implementation of interventions are of critical importance in the prevention of hypertension [4].

Previous observational studies and Mendelian randomization studies have shown associations between lipids and blood pressure [5, 6]. However, most of these studies have focused on the relationship between traditional lipid markers (e.g. total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)) and peripheral blood pressure or hypertension [6,7,8,9,10]. Remnant cholesterol (RC), defined as the cholesterol content of triglyceride-rich remnant lipoproteins, contains substantially more cholesterol per particle than LDL-C [6], and may contribute to hypertension through a variety of mechanisms including vascular dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammatory response, renin-angiotensin system and insulin resistance [11,12,13]. Recent cross-sectional studies investigated the potential association between RC and hypertension, but due to design limitations, a clear temporal relationship could not be established [14, 15]. Two cohort studies have also found a positive association between RC and the risk of developing hypertension, and have shown that RC has a greater impact than traditional risk factors [16, 17]. Although the non-linear relationship between RC and the risk of developing hypertension has been assessed in some of these studies, they did not use piecewise linear regression to perform a threshold effect analysis to find the inflection point, which may be the clinically needed intervention value. Furthermore, because these studies only had data from a single measurement, they were unable to assess the effect of RC on hypertension over time. In conclusion, previous studies have failed to adequately elucidate the complex relationship between RC and hypertension because of the use of cross-sectional designs, the lack of analyses of threshold effects, the failure to assess the effects of temporal changes, and the lack of analyses of mediated effects.

To fill the gap in this area of research, we plan to use data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a nationwide prospective cohort study, to analyze in depth the association between RC and new-onset hypertension in middle-aged and elderly populations, and to explore the dose-response relationship between RC levels and the risk of hypertension and its possible threshold. We also examined the association between RC levels over time and the incidence of hypertension. Finally, our study sought to elucidate the potential mediating role of body mass index (BMI) in the association between RC and hypertension.

Methods

Study population

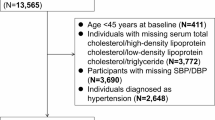

This study analyses a middle-aged and elderly population from the CHARLS database to investigate the relationship between RC levels and new-onset hypertension. CHARLS is a nationwide cohort study designed to be representative of the Chinese population [18]. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015), and all participants provided written informed consent before enrolment. A total of 17,708 participants were included in the study, recruited from 150 counties or districts and 450 villages in 28 provinces of China between 1 June 2011 and March 2012. The participants were selected through a multistage stratified probability proportional to size sampling technique. The response rate for the Wave 1(2011) was 80.5%, with subsequent follow-up assessments conducted at two-year intervals. These included Wave 2 (2013), Wave 3 (2015), Wave 4 (2018), and Wave 5 (2020). All baseline characteristics data were collected in Wave 1 from 2011 to 2012, and blood samples were also collected at baseline and Wave 3. Participants had to be at least 45 years old and have complete data including triglycerides (TG), LDL-C, HDL-C and TC to be included in the study. Two discrete cohorts were extracted from the CHARLS study, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1. Cohort 1 comprised 17,708 participants at the initial visit (Wave 1). Follow-up commenced on the date of their initial enrolment and continued until the onset of new-onset hypertension or the fifth visit (Wave 5), whichever occurred first. After excluding participants who met the exclusion criteria, 7474 individuals were included in the cohort 1 analysis. Cohort 2 had additional exclusion criteria, resulting in the further exclusion of individuals with fewer than two valid TC, LDL-C and HDL-C measurements in the initial three visits (Wave 1 to Wave 3) and individuals with hypertension in both Wave 2 and Wave 3. In conclusion, A total of 3956 participants in Cohort 2 were included in the analysis. In Cohort 2, participants were further stratified based on their cumulative RC measurements from 2011 and 2015. The median follow-up duration was 115 months for Cohort 1 and 67 months for Cohort 2. Participants were instructed to fast overnight prior to blood sample collection. The collected samples were initially stored at local hospitals and then transported to Peking University in Beijing, where they were preserved at −80 °C for subsequent analysis. Triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, and glucose were determined using an enzymatic colorimetric method on the Olympus Automatic Biochemical Analyzer (Hitachi 747). BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared (kg/m²), based on in-person measurements obtained by trained personnel during health examinations.

Assessment of RC

The RC was calculated using the following formula: TC – HDL-C – LDL-C. We calculated the cumulative RC using the formula: (RC2011 + RC2015)/2 × time (2015 − 2011) [19, 20]. RC change was calculated using RC measurements from 2011 and 2015. Based on these two time points, K-means clustering (guided by the elbow method) was used to classify participants into four distinct RC-change trajectory groups.

Assessment of incident hypertension events

In this study, the following criteria were used to classify participants as hypertensive or normotensive at baseline and follow-up (2013, 2015, 2018 and 2020): (i) patient self-report of a physician diagnosis of hypertension; (ii) patient self-report of recent use of antihypertensive medication; and (iii) mean systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg on three measurements [21].

Covariate

Trained interviewers employed standardized questionnaires to collate data pertaining to socio-demographic and lifestyle factors, as well as health-related information, from participants. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is defined as a self-reported history of heart disease: Have you been diagnosed with [Heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, congestive heart failure, or other heart problems by a doctor? Dyslipidemia is defined as a self-reported history of dyslipidemia. The patient reported a diagnosis of dyslipidemia by a physician. The participants were analyzed by staff using standard methods for the following parameters: HDL-C, LDL-C, TC, TG, Serum Uric Acid (SUA), hemoglobin (Hb), fasting blood glucose (FPG), C-reactive protein (CRP), HbA1c, and serum creatinine (Scr).

Statistical analysis

In our study, we leveraged R 4.3.0 software for a thorough statistical analysis, with significance level at p < 0.05 for two-tailed tests. Baseline characteristics were detailed, with continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as number (percentage). We used independent t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical ones, with one-way ANOVA and Chi square tests for group comparisons. Logistic regression was key to assessing the link between RC, cumulative RC and RC change and new-onset hypertension risk, providing ORs and 95% CIs. Multivariable logistic regression models were adjusted for confounders, ensuring accurate relationship estimation. Restricted Cubic Splines (RCS) analysis with the ‘plotRCS’ package explored non-linear relationships, fitting and connecting cubic polynomials at knots (with 4 knots at the 5th, 35th, 65th, 95th.) to capture data trends. We used a two-piecewise linear regression model to examine the threshold effect of RC on incident hypertension. The turning point was identified by maximizing model likelihood across predefined intervals. A log-likelihood ratio test compared the piecewise model with a simple linear model, and bootstrap resampling was used to calculate the 95% CI for the turning point. Furthermore, the change in RC was categorized using the K-means clustering method. The elbow method was employed to ascertain the optimal number of clusters. Mediation analysis, using the ‘mediation’ package in R, centered on BMI and HbA1c as mediators, offered insights into RC’s impact on hypertension risk.

Sensitivity analysis

To evaluate the robustness of our findings, we performed sensitivity analyses by excluding participants on lipid-lowering medications and those with a history of cardiovascular disease at baseline. To further assess the robustness of the results, an additional clustering analysis of RC change was performed using the K-means algorithm, and the elbow method identified three optimal clusters. These three classes represented distinct baseline levels and longitudinal trajectories of RC, defined as low–increase, moderate–increase, and high–decrease. The results from this three-class model were compared with those from the main four-class model to evaluate the influence of classification strategy on the study findings. Initially, Cox proportional hazards regression models were planned to assess the association between RC and incident hypertension. However, because the variables age, DM, and CVD violated the proportional hazards assumption (p < 0.05), a time-dependent Cox regression model was applied instead to ensure model validity and robustness of the results. We further performed causal mediation analyses using the mediation package (version 4.5.0) within a parametric survival model (‘ survreg’) framework to evaluate the potential mediating roles of BMI and HbA1c in the association between RC and incident hypertension. Because the mediation package currently provides limited support for Cox-type outcome models with continuous exposures, the parametric survival model was used to decompose the total, direct, and indirect effects.

Supplemental analysis

In the Supplemental analysis, participants with available RC and blood pressure data in both 2011 and 2015 were included. Changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure were calculated as ΔSBP = SBP2015 – SBP2011 and ΔDBP = DBP2015 − DBP2011. Multivariable linear regression models were constructed with RC trajectory class (Class 1–4) as the independent variable, adjusting for age, sex, alcohol using, smoking status, SUA, CRP, creatinine, DM, CVD, lipid-lowering drug use, and baseline BP. Because RC trajectories were based on two discrete time points, this analysis represents a cross-sectional difference comparison reflecting between-group mean changes rather than continuous longitudinal trends. To maintain temporal consistency, analyses were restricted to the 2011–2015 window corresponding to the RC trajectory definition.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

As shown in Table 1, this cohort study included 7474 Chinese middle-aged and older adults with a mean age of 58.69 ± 9.30 years, 47.5% of whom were male. Participants in the highest RC quartile were younger than the rest of the group, had a higher proportion of females, and had a higher mean BMI compared to participants in the lowest RC quartile. The subjects were more likely to have additional medical conditions, including Diabetes Mellitus, and CVD. Baseline characteristics of cumulative RC and RC change are shown in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2.

Baseline RC and hypertension

A total of 2366 (31.7%) hypertension events were identified following a median follow-up period of 115 months in cohort 1. Table 2 illustrates that in the unadjusted model, the Q4 group exhibited the highest risk of new-onset hypertension in comparison to the Q1 group (OR 95%CI: 1.62 (1.41–1.86); p < 0.001). In Model 1, adjusted for age and gender, the OR of the Q4 group was 1.65 (95% CI: 1.44–1.90, p < 0.001). In Model 2, which was further adjusted for potential confounding factors including education level, alcohol consumption, smoking status, SUA, CRP, Scr, Diabetes Mellitus (DM), CVD and lipid-lowering drugs, the risk of new-onset hypertension in the Q4 group remained significant (OR:1.52, 95% CI: 0.98–1.31, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the risk OR in Model 2 were 1.13 (95% CI: 0.98–1.31, p = 0.10) and 1.18 (95% CI: 1.02–1.36, p = 0.03) for the Q2, Q3 and Q4 groups, respectively, in comparison to the Q1 group.

Cumulative RC and hypertension

The present study has demonstrated that cumulative RC, which reflects fluctuating RC levels, is significantly associated with the risk of new-onset hypertension (Table 2). The logistic regression analysis indicated that an increase in cumulative RC was associated with an increased risk of new-onset hypertension (OR 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01–1.08, p = 0.02). Further adjustment in model 2 revealed that group Q4 remained significantly associated with the development of hypertension (OR 1.39, 95% CI: 1.11–1.75, p = 0.004). The test for trend indicated a statistically significant upward trend in the risk of hypertension with increasing cumulative RC levels (p for trend = 0.003). These findings indicate that cumulative RC level is an independent risk factor of hypertension and that the risk of new-onset hypertension increases with rising cumulative RC levels.

RC change and new-onset hypertension

In order to ascertain the optimal number of clusters for changes in RC, the elbow method was employed (Fig. 1 A). The transition of RC from 2011 to 2015 was categorized into four classes using K-means clustering (Fig. 1 B). In particular, the mean RC value for Class 1 (0.36 in 2011 to 0.60 in 2015, indicating the lowest level of RC with a persistent increase) and Class 2 (0.83 in 2011 to 1.57 in 2015, indicating a lower level of RC with a high level of increase) is noteworthy. Class 3 (1.03 in 2011 to 0.75 in 2015), indicating a higher level of RC with a persistent decrease, Class 4 (2.75 in 2011 to 1.62 in 2015), indicating a higher level of RC with a high level of decrease (Fig. 1 C), respectively. The results demonstrated that the remaining three categories (Class 2, 3 and 4) did not exhibit statistically significant differences in risk of new-onset hypertension compared to the reference category (Class 1) in multivariable analyses (Table 2). The OR for Class 2, Class 3, and Class 4 were 1.28, 1.10, and 1.14, respectively. However, none of these reached statistical significance (p values of 0.07, 0.32, and 0.54, respectively). Figure 1 D illustrates the distribution of the four RC classes.

Identification of nonlinear relationship between baseline variables and hypertension

In this study, we used the RCS method to assess whether there is a nonlinear dose response relationship between RC and new-onset hypertension in the middle-aged and elderly population (Fig. 2 and Table 3). Using RCS analyses, we found that there was a non-linear relationship between RC and new-onset hypertension in the middle-aged and elderly population after adjustment for educational level, alcohol consumption, smoking status, SUA, CRP, creatinine, DM, CVD and lipid-lowering medication (baseline RC: p for overall <0.001, p for nonlinear = 0.004; RC cumulative: p for overall <0.001, p for nonlinear = 0.003). Using a two piecewise linear regression model, we identified an inflection point for RC of 1.16 mmol/L. When RC ≤ 1.16 mmol/L, increasing RC levels were associated with an elevated risk of incident hypertension (OR: 1.63, 95% CI: 1.39 to 1.92, p < 0.001). However, when RC > 1.16 mmol/L, the results showed that higher RC values may be associated with an increased risk of new-onset hypertension, but this association was not statistically significant (OR: 1.06, 95% CI: 0.93–1.20, p = 0.39).We also compared the difference in effect between the two intervals of RC below and above 1.16 mmol/L and found a significant difference (OR: 0.65, 95% CI: 0.51- 0.83, p < 0.001). The results of the log-likelihood ratio test also supported the superiority of the segmented model over the single model (log-likelihood ratio test p < 0.001).

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses by age, gender, BMI ( < 24 kg/m2 or ≥24 kg/m2), smoking, CVD and DM were also performed to investigate the impact of different subpopulations on the relationship between RC and risk of new-onset hypertension, as shown in Fig. 3.

Mediation analysis

The mediation effect analysis indicated that both BMI and HbA1c exerted a partial mediating influence on the relationship between RC and hypertension. As illustrated in Fig. 4, there was a direct influence of RC on hypertension (β = 0.0318, p < 0.001). Moreover, the results indicated that RC exerted an indirect effect on hypertension (β = 0.0186, p < 0.001) through BMI. Thus, BMI, as a mediating variable, accounted for 36.94% of the total effect of RC on hypertension. In another pathway, RC exerted a direct influence on hypertension (β = 0.0285, p < 0.001). Additionally, RC had an indirect effect on hypertension (β = 0.002, p = 0.006) through HbA1c. Therefore, HbA1c played a mediating role in the relationship between RC and hypertension, accounting for 7.2% of the total effect.

Sensitivity analyses

The results of the sensitivity analyses, as presented in Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4, demonstrated that the relationship between baseline RC and its cumulative exposure with the risk of hypertension remained consistent across the various models. Furthermore, the observed association between RC and the risk of hypertension was not influenced by the exclusion of patients on lipid-lowering medications or with a history of cardiovascular disease. In the sensitivity analysis based on the three-class model, the results were generally consistent with those from the main four-class analysis. The direction and magnitude of the associations showed minimal variation across groups. The results of the time-dependent Cox regression model were generally consistent with those of the primary logistic regression analysis, with no substantial changes in the direction or magnitude of the associations between remnant cholesterol–related indicators and incident hypertension (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 5). In the causal mediation analysis based on the parametric survival model, the proportion mediated by BMI was approximately 29.9% (95% CI: 22.2–42.5%), whereas the proportion mediated by HbA1c was 7.8% (95% CI: 4.3–13.1%).

Supplemental analysis

Mean ΔSBP ranged from 0.3 to 1.9 mmHg (p = 0.389) and mean ΔDBP from 0.1 to 2.0 mmHg (p = 0.044) across the four RC trajectory groups, with minimal differences (Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Table 7). After multivariable adjustment, neither the mildly declining Class 3 nor the markedly declining Class 4 trajectory showed a decrease in BP. Instead, Class 4—characterized by the highest baseline RC—showed slightly higher ΔSBP (β = 3.96, p = 0.003) and ΔDBP (β = 2.08, p = 0.016), likely reflecting baseline heterogeneity rather than a causal BP reduction.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the relationship between RC and cumulative RC and RC change and the new-onset of hypertension in middle-aged and older Chinese people, as well as the possible mechanisms of RC-induced hypertension through mediation analysis. The findings of the study indicated a notable correlation between baseline RC levels and cumulative RC exposure with the risk of developing hypertension. Furthermore, the relationship between baseline RC and hypertension exhibited a nonlinear dose-response relationship. Further mediation analyses demonstrated that BMI and HbA1c played a partial mediating role between RC and hypertension, explaining 36.94 and 7.2% of the total effect, respectively. In subsequent subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses, the association between baseline RC and cumulative residual cholesterol with new-onset hypertension remained unchanged when the data were stratified by age, sex, drinking habits, smoking status, history of DM, and history of CVD, and when patients on lipid-lowering drugs or with CVD were excluded.

Our findings are in accordance with those of previous studies examining the relationship between RC and hypertension. Previous studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of hypertension in the middle-aged and elderly population ranges from 13.2% to 44.5% [16, 17]. Additionally, these studies have indicated that the global burden of the disease is predominantly concentrated in low- and middle-income countries, particularly among the middle-aged and elderly population [22]. A prospective cohort study of middle-aged and older adults in China revealed that the prevalence of hypertension at follow-up was 31.7% [23]. Furthermore, an association between RC and the risk of hypertension has been demonstrated [16]. Guo et al. observed a 27% increase in the risk of developing hypertension for every 1 mmol/L increase in baseline RC levels, a finding that is consistent with the results of our study on baseline residual cholesterol and new-onset hypertension [16]. A further cross-sectional study, based on a Chinese community-based population, demonstrated that RLP-C blood levels were significantly associated with higher central systolic blood pressure, a result that was independent of other lipid levels [24]. While the aforementioned studies demonstrated a robust correlation between residual cholesterol and the risk of hypertension, they primarily focused on baseline residual cholesterol levels, neglecting to investigate cumulative exposure and RC change trajectories in depth. The absence of time-series data in cross-sectional studies constrains the scope for dynamic analyses.

In contrast to previous studies that employed baseline RC data at a single time point, our study not only considered newly diagnosed hypertension cases over approximately 10 years of follow-up, but also investigated the impact of cumulative residual cholesterol, analyzed the relationship between baseline RC and new-onset hypertension, and determined the threshold for the relationship between RC and new-onset hypertension by segmented linear regression analysis. The findings of our study indicate a significant correlation between baseline RC levels and the risk of new-onset hypertension. Those participants with baseline RC in the fourth quartile exhibited a 27% increased risk of new-onset hypertension in comparison with the first quartile. The use of cumulative measurements of RC enabled a more accurate assessment of its long-term effects, with the result that individuals with cumulative RC concentrations in the fourth quartile exhibited a 39% increased risk of new-onset hypertension in comparison with the first quartile. The follow-up of two groups of middle-aged and older adults without hypertension at baseline demonstrated the impact of baseline and cumulative RC exposure on the risk of new-onset hypertension, with an increased risk of 39%. This approach not only enhances the reliability of the results, but is also more aligned with the complexities of real-world clinical scenarios, as it considers the fluctuations in RC levels over time. Furthermore, a k-mean cluster analysis was employed to facilitate a systematic classification of alterations in RC. Despite the absence of a significant association between RC changes and the risk of new-onset hypertension, this may be attributed to insufficient statistical efficacy due to the limited sample size. Furthermore, the correlation between new-onset hypertension and the RC level was more pronounced when the RC level was below 1.16 mmol/L. The identification of this threshold provides a potential target for RC interventions in clinical practice. The non-significant association observed when RC exceeded 1.16 mmol/L may be partly attributable to the limited number of participants with RC values above this threshold (about 11%), resulting in reduced statistical power in the higher range. Additionally, this plateau phenomenon may indicate that once RC levels surpass a certain level, further increases exert a diminishing effect on hypertension risk.

In this study, through mediation effect analysis, we discovered the partial mediating role of BMI and HbA1c in the relationship between RC and the risk of new-onset hypertension by mediation effect analysis. Specifically, the mediating effect was 0.0186 when BMI was used as a mediating variable, which explained 36.94% of the total effect of RC on hypertension. This finding may be related to the role of BMI as an indicator of obesity, which is itself associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. It is possible that obesity may result in an elevation of the level of inflammation within the body, which may subsequently affect vascular endothelial function and, in turn, increase the risk of developing hypertension. Conversely, when HbA1c was employed as a mediating variable, the mediating effect was 0.002, representing 7.2% of the total effect. The association between HbA1c and hypertension may be explained by a number of mechanisms, including direct damage to the vascular wall from elevated blood glucose levels and indirect effects through influencing insulin sensitivity and metabolic pathways that affect blood pressure. The discovery of these mediating effects provides new insights into our understanding of how RC affects new-onset hypertension. BMI and HbA1c, as modifiable risk factors, may be potential targets for hypertension prevention and management.

The present study has the following strengths. Firstly, it is the first study to demonstrate an association between high cumulative RC exposure and the risk of new-onset hypertension. The longitudinal association between baseline RC levels and cumulative exposure and new-onset hypertension in a middle-aged and elderly population was further confirmed with the follow-up data from the cohort study. Furthermore, a mediated effects analysis was conducted, which indicated that BMI and HbA1c may act as mediating variables affecting the risk of RC and new-onset hypertension. This finding increases the credibility of our results and provides additional evidence for the potential of RC as a predictor of new-onset hypertension. The present study also has limitations. Firstly, the study did not involve any interventions, so we could not assess the potential impact of changing RC levels on the risk of hypertension. Secondly, it proved impossible to distinguish accurately between primary and secondary hypertension in each individual, and the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the effect of RC abnormalities on new-onset hypertension in the middle-aged and elderly population could not be subjected to careful exploration. Thirdly, there may be unidentified confounders, such as genetic susceptibility within the participating population. Therefore, we adjusted for possible confounders in the regression model as much as possible, utilizing relatively large sample sizes and long follow-up periods. Furthermore, we conducted sensitivity analyses, which should ensure the reliability of the results. Future studies should consider collecting RC data at additional time points to enhance the understanding and analysis of the relationship between RC and hypertension.

Conclusion

The present study showed a significant association between RC levels and the incidence of new-onset hypertension in the middle-aged and elderly population. Individuals with higher baseline RC and cumulative RC exhibited a higher risk of hypertension. Furthermore, BMI and HbA1c partially mediated the association between RC and hypertension, explaining 36.94% and 7.2% of the effect, respectively.

Summary

What is known about the topic

-

Remnant cholesterol (RC) is a lipoprotein particle with high cholesterol content and is associated with cardiovascular disease.

-

Prior studies have shown associations between RC and cardiovascular events, but its link to new-onset hypertension remains unclear.

-

While traditional lipid markers are well-studied in relation to hypertension, the role of RC and its dynamic changes over time are less explored.

What this study adds

-

Comprehensive Assessment of RC Exposure: Utilized three distinct measures of RC exposure - baseline, cumulative, and change patterns - providing a comprehensive temporal assessment that has not been previously reported.

-

Non-linear Relationship and Therapeutic Target: Through restricted cubic spline analysis, we discovered a non-linear relationship between RC and hypertension with an inflection point at 1.16 mmol/L, providing a potential therapeutic target that could inform clinical decision-making.

-

Mediation Analysis Insights: Mediation analysis revealed that BMI and HbA1c partially mediated the RC-hypertension relationship, accounting for 36.94 and 7.2% of the total effect respectively. This finding provides new insights into the mechanisms linking RC to hypertension development.

Data availability

The data used in this study were obtained from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) and are available upon reasonable request from the CHARLS project, subject to their data access policies (http://charls.pku.edu.cn).

References

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet (London, England) 2021;398:957-80.

Cao X, Wang X, Tian Y, Tuerdi N, Zheng C, Li W, et al. Trends and sociodemographic patterns in hypertension prevalence and treatment in China. Med. 2025;6:100808.

Li Y, Yang L, Wang L, Zhang M, Huang Z, Deng Q, et al. Burden of hypertension in China: A nationally representative survey of 174,621 adults. Int J Cardiology. 2017;227:516–23.

Yan J, Zhang M, He Q. Association of changes and cumulative measures of triglyceride-glucose index-body mass index with hypertension risk: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:2652.

Borghi C, Veronesi M, Bacchelli S, Esposti DD, Cosentino E, Ambrosioni E. Serum cholesterol levels, blood pressure response to stress and incidence of stable hypertension in young subjects with high normal blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2004;22:265–72.

Liu W, Yang C, Lei F, Huang X, Cai J, Chen S, et al. Major lipids and lipoprotein levels and risk of blood pressure elevation: a mendelian randomisation study. EBioMedicine. 2024;100:104964.

Ferrara LA, Guida L, Iannuzzi R, Celentano A, Lionello F. Serum cholesterol affects blood pressure regulation. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16:337–43.

Wilkinson IB, Prasad K, Hall IR, Thomas A, MacCallum H, Webb DJ, et al. Increased central pulse pressure and augmentation index in subjects with hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1005–11.

Halperin RO, Sesso HD, Ma J, Buring JE, Stampfer MJ, Gaziano JM. Dyslipidemia and the risk of incident hypertension in men. Hypertension. 2006;47:45–50.

Mancia G, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, Polo Friz H, Grassi G, Giannattasio C, et al. Relationship of office, home, and ambulatory blood pressure to blood glucose and lipid variables in the PAMELA population. Hypertension. 2005;45:1072–7.

Guzik TJ, Touyz RM. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and vascular aging in hypertension. Hypertension. 2017;70:660–7.

Zheng X, Liu L. Remnant-like lipoprotein particles impair endothelial function: direct and indirect effects on nitric oxide synthase. J OF LIPID Res. 2007;48:1673–80.

Dinh QN, Drummond GR, Sobey CG, Chrissobolis S. Roles of inflammation, oxidative stress, and vascular dysfunction in hypertension. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:406960.

Wang J, Sun Q, An Y, Liu J, Leng S, Wang G. The association of remnant cholesterol (RC) and interaction between RC and diabetes on the subsequent risk of hypertension. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:951635.

Chen MM, Huang X, Xu C, Song XH, Liu YM, Yao D, et al. High remnant cholesterol level potentiates the development of hypertension. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:830347.

Guo DC, Gao JW, Wang X, Chen ZT, Gao QY, Chen YX, et al. Remnant cholesterol and risk of incident hypertension: a population-based prospective cohort study. HYPERTENS Res. 2024;47:1157–66.

Kasahara A, Adachi H, Hirai Y, Enomoto M, Fukami A, Yoshikawa K, et al. High level of plasma remnant-like particle cholesterol may predispose to development of hypertension in normotensive subjects. AM J OF HYPERTENS. 2013;26:793–8.

Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the china health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:61–8.

Huo R, Zhai L, Liao Q, You X. Changes in the triglyceride glucose-body mass index estimate the risk of stroke in middle-aged and older Chinese adults: a nationwide prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:254.

Zheng X, Han W, Li Y, Jiang M, Ren X, Yang P, et al. Changes in the estimated glucose disposal rate and incident cardiovascular disease: two large prospective cohorts in Europe and Asia. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:403.

Liu T, Xuan H, Yin J, Wang L, Wang C, Xu X, et al. Triglyceride glucose index increases significantly risk of hypertension development in chinese individuals aged ≥45 years old: analysis from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2023;16:63–73.

Lawes CMM, Vander Hoorn S, Rodgers A. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet. 2008;371:1513–8.

Rajaeieh G, Takian A, Kalantari N, Mohammadi-Nasrabadi F. Analysis for policy to overcome barriers to reducing the prevalence of vitamin a deficiency among children (15–23 months) in Iran. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1234.

Li K, Fan F, Zheng B, Jia J, Liu B, Liu J, et al. Associations between remnant lipoprotein cholesterol and central systolic blood pressure in a Chinese community-based population: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 2021;20:60.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62172288).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: All authors. Manuscript drafting: Yuanyuan Zhao, Dongjie Du. Statistical analysis: Yuanyuan Zhao, Dongjie Du. The acquisition of data: Dongjie Du. Yuanyuan Zhao and Dongjie Du assisted with data collection and interpretation. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Supervision: Zhi Liu. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, Y., Du, D. & Liu, Z. Cumulative exposure to remnant cholesterol and new-onset hypertension in middle-aged and older adults: a nationwide prospective cohort study with mediation analysis. J Hum Hypertens (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-025-01108-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-025-01108-3