Abstract

Objective

Compare Eat, Sleep, Console (ESC) and limited opioid treatment on birth length of stay (LOS), postnatal opioid exposure, and 30-day re-hospitalizations in opioid-exposed newborns (OENs) in two hospital systems.

Study design

Quality improvement teams supported change from scheduled methadone using Finnegan scores to standardized non-pharmacologic support using ESC. Intermittent morphine was used only if needed. Statistical process control charts examined changes over time.

Result

Between 2017 and 2019 we treated 280 OENs ≥35 weeks’ gestation, 101 and 179 per hospital. Post-ESC, LOS decreased 51.2% (16.8–8.2 days), postnatal opioid treatment decreased from 64.1 to 29.9%; percent decline in both hospitals was similar. 30-day re-hospitalizations were 5/103 (4.8%) pre-ESC, and 7/177 (4.0%) post-ESC (p = 0.72, NS). Multiple substance co-exposures were common (226/280, 80.7%).

Conclusion

ESC and as needed morphine decreased LOS and postnatal opioid exposure for OENs in two hospital systems without increasing 30-day readmissions. ESC appears effective in OENs with multiple co-exposures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Opioid use during pregnancy has risen substantially throughout the United States over the past two decades, leading to over a 300% increase in fetal opioid exposure [1, 2]. During the same period, neonatal opioid withdrawal increased nearly fivefold, ranging from 8 to 14.4/1000 live births [2, 3]. In 2014, nearly 1% of all births in the United States were complicated by neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS), also referred to as neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Hospitals in Colorado have seen similar dramatic growth in the incidence of NOWS and NAS, particularly in southern counties with the highest rates of opioid use disorder and opioid deaths [4]. For example, rates of NOWS were reported as high as 20.8 per 1000 live births in Pueblo, Colorado in 2012 compared to the statewide rate of 3.2 per 1000 [5]. Increasing rates of NAS have led to prolonged birth hospitalizations, rising costs of newborn care and increased use of hospital resources [6].

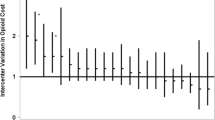

With increased rates of NOWS/NAS, substantial variation has been identified in approaches to infant screening and treatment during the birth hospitalization [7,8,9]. Pharmacologic management of NOWS includes methadone, morphine, and buprenorphine with varying claims of benefit, but without a single clear medication-based treatment recommendation [8, 10, 11]. Quality improvement (QI) projects aimed at standardizing care have reduced lengths of birth hospitalizations and identified potentially improved practices to care for newborns with NOWS [6, 8, 12, 13]; several emphasize non-pharmacologic approaches [12, 13].

El Paso county had reported the most fatal heroin overdoses in Colorado in 2016 [14], and Pueblo county the highest rates of prenatal opioid exposure [5]. In 2017, the Colorado Hospital Substance Exposed Newborn Quality Improvement Collaborative (CHoSEN QIC) began a statewide QI effort to standardize care of opioid-exposed newborns (OENs) using the “Eat, Sleep, and Console” (ESC) pathway reported by Grossman et al. [12, 13, 15, 16]. The primary aims of this QI project were to reduce length of stay (LOS) and postnatal opioid treatment by 20% from baseline [15]. University of Colorado Health (UCHealth) Memorial Hospital (El Paso county) and Parkview Medical Center (Pueblo county) each joined CHoSEN QIC. One Neonatology group worked in both hospital systems; due to this there was historically a high-level of guideline sharing despite the two different systems. Through CHoSEN QIC additional education and information sharing occurred among hospitals. We were interested in evaluating the impact of ESC in these differing hospital systems and communities: a large tertiary referral Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) and a smaller community special care nursery (SCN), specifically looking at LOS and postnatal opioid exposure. In addition to the QI project aims, after implementing the ESC pathway, changing the approach to postnatal opioid treatment and reducing LOS at both hospitals, we examined 30-day hospital readmissions before and after the interventions as a balancing measure. Due to our experience and patient populations, we were able to apply the ESC approach in the setting of multiple in utero substance exposures in addition to opioids.

Methods

Hospital system characteristics

UCHealth Memorial in Colorado Springs (“Memorial”) included two Level I newborn nurseries, a 53-bed Level IV NICU and a 6-bed Level II SCN and cares for about half of the births in El Paso county, or 4500–5000 newborns per year. Rooming-in was available in the mother–baby unit and to a much more limited extent in small private NICU rooms. Prior to implementing ESC there was not a standardized approach to supporting rooming-in and non-pharmacologic care for OENs. If an OEN in the newborn nursery was started on methadone treatment based on Finnegan scores they were transferred to the NICU for monitoring and ongoing care. In addition, newborns experiencing NOWS were transported to the NICU from outlying facilities for methadone treatment.

Parkview Medical Center (“Parkview”) includes a Level I newborn nursery, a ten-bed Level II SCN, and a small pediatric unit where newborns were occasionally hospitalized. In 2018, Pueblo’s other hospital’s obstetrical services closed, and Parkview became the only hospital providing delivery services in the county with about 2000 births per year. Parkview had supported rooming-in and use of some non-pharmacologic care approaches for OENs prior to starting the ESC pathway approach to care. If an OEN started on scheduled methadone during initial treatment they were moved to the SCN for monitoring and rooming-in was not available. Once methadone weaning was established, patients were moved to the pediatric floor for rooming-in as possible.

Each hospital system had separate QI teams and provider staff, other than the neonatologists.

ESC assessment and care standardization

ESC uses a simplified behavioral assessment tool focusing on specific early non-pharmacologic interventions to support newborns experiencing symptoms of narcotic withdrawal [12]. CHoSEN QIC provided educational support to help hospital teams develop and implement an ESC care pathway. Non-pharmacologic interventions began at birth and included providing a low stimulation environment, clustering infant cares, swaddling, holding and gently rocking the infant, and on demand feedings. Parents or other caregivers were encouraged to room-in with the newborn whenever possible. Options for rooming-in differed by hospital. At Memorial, rooming-in occurred in postpartum rooms or more limited spaces in the NICU. At Parkview, parents/caregivers roomed-in on postpartum or the general pediatric floor in a private room. Breastfeeding was supported when appropriate (e.g., mothers not using illicit substances, or in treatment programs). When a parent was not available, both hospitals trained volunteer “cuddlers” to participate in the care pathway. If foster or kinship placement was anticipated, those caregivers were included as much as possible.

The ESC assessment regularly evaluated whether the baby could Eat appropriately for their age, Sleep undisturbed for at least 1 h between feedings, and be Consoled or soothed within 10 min using specific interventions [8, 12]. When an infant did not meet these goals, a team huddle evaluated whether the environment of care was optimal, if other non-pharmacologic interventions could be helpful, and whether medication (morphine infant drops) was needed [12].

Use of medication to treat NOWS

Prior to this QI effort, both hospital systems used the same generally accepted management guideline using Finnegan scores to assess NOWS and treatment with scheduled methadone for elevated scores [17]. Once methadone treatment began, patients were moved into a monitored room separate from the mother: the NICU at Memorial and the SCN or Pediatric floor at Parkview. Methadone was tapered per protocol based on subsequent Finnegan scoring [17]. If scores remained persistently elevated despite methadone treatment, a second pharmacologic agent was added, typically clonidine. As part of the ESC project, pharmacologic treatment was changed to an “as needed” or intermittent basis using oral morphine sulfate drops, in part due to its shorter half-life. Both hospital systems changed to “as needed” morphine dosing for symptoms of NOWS during the second quarter 2018.

Project management

Both hospitals joined CHoSEN QIC in early 2018 and transitioned to the ESC pathway in the second quarter 2018, although specific elements of ESC varied slightly by site. For example, at Memorial, ESC started as a pilot program in the NICU, where most patients with NOWS were treated. NICU nursing staffs, NNPs, and neonatologists were first trained in the ESC pathway, and OENs in the well newborn nursery were transferred to the NICU early if they demonstrated opioid withdrawal symptoms. Rooming-in was continued in the NICU when possible. Nursing staffing ratios were adjusted to provide more opportunities for staff to educate family caregivers or provide consoling interventions when a caregiver could not stay with the newborn. Volunteer cuddlers were trained to provide standardized consoling interventions, and foster parents or kinship caregivers were identified early to room-in with infants when possible. After starting ESC in the NICU, nursing staff in the well newborn nursery and mother–baby units were trained to follow the ESC pathway, and hospital care was later provided in these locations or the NICU.

At Parkview, all nursing staff working in the well newborn nursery, SCN, or pediatric floor were trained in ESC assessment and the ESC pathway was implemented throughout all locations of newborn care at the same time in the second quarter of 2018. Rooming-in was not available in the SCN but could be provided on the pediatric or postpartum floors.

Each hospital updated its electronic health record (EHR) to allow nursing charting of ESC, engaged with hospital and community providers to explain the ESC approach to care, and attended CHoSEN QIC conferences and education sessions. Multidisciplinary teams at each hospital met regularly to direct process change as part of QI cycles. In addition, Parkview team leads initially participated in monthly multidisciplinary meetings at Memorial. Written educational materials for providers and parents were shared between the two sites. Clinical practice change was supported with site-specific education and charting tools and mandated computer-based-training for nursing staff.

Data collection and analysis

After joining CHoSEN QIC, all OENs admitted to the hospitals were prospectively identified and tracked based on maternal history, maternal drug screening, maternal symptoms, newborn symptoms, newborn urine drug screens, and/or umbilical cord screening. Each hospital determined its own criteria for initial screening and both hospitals obtained umbilical cord samples for confirmation of fetal drug exposures. At Memorial Hospital, EHR reports of ICD-10 codes P04.4× (newborn affected by maternal use of drugs of addiction) and P96.1 (neonatal withdrawal symptoms from maternal use of drugs of addiction) were periodically retrieved to help ensure any affected newborns were identified.

Baseline data were collected by retrospective chart review using ICD-10 codes (P04.4× and P96.1) and search of each hospital’s EHR. CHoSEN QIC underwent Institutional Review Board assessment and was deemed exempt as a QI project. Data were collected using REDCap hosted at the University of Colorado [18]. As a de-identified database, collected information was entered and reported by birth quarter. Data elements included limited maternal sociodemographic characteristics, maternal treatment with buprenorphine or methadone to indicate participation in Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT), other maternal substance use during pregnancy (e.g., nicotine and marijuana), prescribed substances (e.g., SSRIs, benzodiazepines), illicit drugs such as methamphetamine/amphetamine and non-prescribed opioids. Infant clinical characteristics included birth hospitalization LOS, and exposure to postnatal opioid treatment. Data reports were prepared by the CHoSEN QIC Quality Improvement Specialist to track progress and included statistical process control analysis using X-bar S charts for the primary outcome measure of average LOS. Standard rules were used to identify special cause variation [19]. Process changes were identified by sustained special cause variation on the control charts.

After data entry through 2019 was completed, each site separately reviewed its hospital’s EHR using birth medical record numbers to evaluate readmissions within 30 days of discharge.

Results

Patient characteristics

There were 310 OENs gestational age 35 weeks or greater at birth from both hospitals identified from the first quarter of 2017 through the fourth quarter of 2019. Of these, 288 had no other diagnoses contributing to increased LOS. Complete data were available for analysis on 280 patients, including 101 patients from UCHealth Memorial and 179 patients from Parkview Medical Center. The majority (54%) of patients in the cohort were born to White mothers, 34% were born to Hispanic mothers. Almost all (93%) mothers had public insurance. Overall, 80.7% of the full cohort had exposures in addition to opioids (226 of 280), with 53.9% of mothers (151 of 280) reported as receiving MAT (Table 1).

Primary outcomes

Length of stay (LOS)

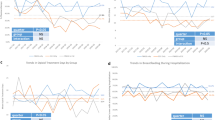

Average LOS decreased by 51.2% for the entire cohort, from 16.8 days at baseline to 8.2 days after implementation of ESC (Fig. 1a). The percent decrease in LOS before and after ESC was similar in both hospital systems, from 23.2 to 10.9 days (53%) at UCHealth Memorial (Fig. 1b) and from 14.8 to 7.6 days (48.6%) at Parkview Medical Center (Fig. 1c). Postnatal treatment with opioids prolonged hospital stay, but to a less extent after implementing ESC and as needed morphine dosing. Average LOS for the cohort in OEN who received pharmacotherapy decreased 53.7%: from 23.1 days at baseline to 10.7 days for morphine-treated patients after ESC, with similar percent declines in LOS at each hospital.

Pharmacologic treatment

Use of postnatal opioids for pharmacotherapy significantly decreased after ESC, from 66 of 103 patients (64.1%) at baseline to 53 of 177 (29.9%) patients treated with pharmacotherapy after implementation of ESC (Table 2, p < 0.0001 chi square). There were similar reductions in numbers of infants exposed to postnatal opioids in both hospitals: after ESC, pharmacologic treatment of NOWS decreased 58% at UCHealth Memorial and 51% at Parkview Medical Center (Table 2). Prior to ESC, clonidine as a second agent was infrequently added as treatment to control symptoms of NOWS, after ESC a second agent was never used.

In addition to exposing fewer patients to postnatal opioids, using ESC and changing to intermittent “as needed” morphine pharmacotherapy dramatically lowered the average length of treatment in the cohort from 19.0 days in the first quarter of 2017 to 2.5 days in the last quarter of 2019, a reduction of 86.8% (Fig. 2). Patient treatment days at Memorial Hospital were 81% lower, from a baseline average of 17.4 days of treatment to 3.3 days after ESC. Treatment days at Parkview decreased 76.1%, from 18 to 4.3 days if medication was used.

Hospital readmissions

Neither hospital had any 30-day readmissions directly related to NOWS; however, the characteristics of patients readmitted varied between the two hospitals (Table 3). Of note, after ESC there were three readmissions in Parkview for brief, resolved, unexplained events (BRUE), with none at Memorial. The single admission for non-accidental trauma occurred at Memorial before implementation of ESC, following a 2-month birth hospitalization for NOWS. Because 30-day hospital readmission was a rare event, we combined data for the full cohort. The overall readmission rate before and after ESC was unchanged, from 4.9% pre implementation (5 of 103 patients) to 4.0% post implementation (7 of 177 patients) (NS, p = 0.72, chi square).

Discussion

The ESC assessment tool and clinical care pathway emphasizes standardizing non-pharmacologic interventions to support newborns experiencing opioid withdrawal and avoiding use of medication as the first-line approach to treat NOWS. As part of a multi-hospital effort in two different hospital systems in two counties with a large burden of maternal opioid use during pregnancy, LOS and postnatal opioid exposure were rapidly and substantially decreased without evidence of short-term increases in hospital readmissions. ESC was successfully applied in varied hospital settings (NICU, well baby nursery, pediatric floor), with varied providers (Neonatologists, NNPs, Pediatric hospitalists) and with multiple maternal substance exposures.

Reasons for success

Staff engagement and buy-in

Prior to implementing ESC, both hospitals experienced increasing numbers and prolonged stays for infants with NOWS treated using a Finnegan scoring system and standardized methadone treatment and weaning algorithm. At Memorial, over 10% of NICU admissions in 2017 were for treatment of NOWS using methadone. At Parkview, infants required transfer from the SCN to the pediatric floor for prolonged hospitalizations. As numbers of OENs and LOS increased, variations in staff use of Finnegan scores, disengagement of parents during prolonged hospital stay and provider and staff fatigue were observed. The ESC approach was quickly embraced by the majority of staff as a way to engage parents and families when available, and the simplified assessment tool was easily adopted. Staff “buy-in” was critical to early success, and the prompt decreases in LOS maintained over time contributed to ongoing staff enthusiasm for the ESC approach. Parents also voiced appreciation for ESC which supported staff.

Lactation support

While only a small number of mothers were eligible to breastfeed their infants, supporting maternal lactation and breastfeeding likely made some contribution to success. Mothers eligible to breastfeed their infants were encouraged to perform skin-to-skin care and feed their infant on demand. Lactation support specialists were consulted for all breastfeeding women and a manual or electric pump was provided to support maternal lactation.

Providing non-pharmacologic infant care

In many cases parents or other family caregivers were not available to help support their infants while hospitalized. To address this, both hospital systems expanded the use of trained volunteer cuddlers, and reduced staffing ratios to allow bedside nurses to feed, hold and comfort newborns experiencing withdrawal symptoms as needed. At Memorial Hospital, rooming-in could occur in the NICU with an identified family member or surrogate if a parent was not available. Efforts were made to identify a guardian or foster placement as quickly as possible to participate in care. At Parkview Hospital, rooming-in could occur on the Pediatric floor after maternal discharge.

Care location

The location of care for most newborns changed over the course of the project. With decreased postnatal opioid treatment, patients rarely required cardiorespiratory monitoring. Therefore, at Memorial the large majority of patients could remain on the mother–baby unit after ESC and were no longer transferred to the NICU. At Parkview patients were moved to the Pediatric floor where mothers could stay with the newborn when beds were available, and occasionally infants and their mothers roomed-in on the postpartum floor after mothers’ discharge from the hospital. Parent education and staff satisfaction were supported by these locations of care.

Reduced postnatal opioid therapy

Both hospitals changed from scheduled methadone dosing to intermittent “as needed” oral morphine when pharmacologic treatment was used, similar to Grossman et al. [12]. At baseline, Memorial hospital had a greater proportion of patients treated with opioids for NOWS compared to Parkview. This was in part due to the NICU setting which included both inborn patients and outborn infants transferred for medical treatment. Also, at Parkview, rooming-in was more available and non-pharmacologic care approaches were already more widely in use. Nonetheless, at both hospitals the number of patients exposed to postnatal opioids and the number of days of exposure declined to a similar extent. Emphasizing avoiding medication as first-line treatment and training staff to focus on specific newborn behaviors (rather than a numerical score) were key elements to our success transforming care. We believe that the type of postnatal opioid used (methadone or morphine) is less important than a focus on optimizing non-pharmacologic interventions and avoiding scheduled dosing. While data are limited, postnatal outcomes do not appear to differ by type of postnatal opioid exposure [20, 21]. Nonetheless, long-term effects of limiting postnatal opioid exposure are unknown. Clearly, studies of infant and childhood outcomes over longer periods of time will improve our understanding of the impact of in utero and postnatal opioid exposure on long-term neurodevelopment as well as social risk to this vulnerable population of newborns.

Co-exposures and ESC

Importantly, multiple substance exposures were common in this patient cohort, with 80.7% of mothers using other substances along with opioids at any point during pregnancy (226 of 280), and only 19.3% using opioids alone (54 of 280). Thus, the ESC approach appears successful in treating multiple co-exposures that might include elements of abstinence and discontinuation syndromes, suggesting that various exposures occurring in addition to opioids can be assessed with ESC and treated non-pharmacologically.

Slightly more than half of pregnant women with opioid use in our cohort were receiving MAT. Of those, 61% were using other opioids or illicit substances, such as methamphetamine, amphetamines, or cocaine. As a result, we recommend screening for other exposures continue even for women in MAT programs at the time of delivery. Because of multiple substance exposures, most newborns in the cohort were not eligible to receive their mother’s own milk.

Limitations

This project has several limitations. First, while hospital readmission rates in our cohort did not increase, it is possible that patients were admitted elsewhere after discharge from their birth hospital. We believe this to be unlikely, as patterns of hospital use in both counties tended to stay within the original system of care. Also, both counties had only one other hospital where an infant might be hospitalized, and primary care providers aware of the CHoSEN QIC project and potential concerns about the impact of earlier discharge on the community did not report other readmissions. Second, while there were no readmissions directly related to NOWS in the post-implementation period, it is possible that some readmissions were indirectly related. For instance, in the Parkview cohort, patients with BRUE as the principal diagnosis raise the question of adequacy of family support, education and discharge preparation. Finally, this project reports only the short-term outcome of 30-day readmissions. It is unclear if greater burdens related to infant care are being placed on families who already bear significant social and economic stressors or on primary care providers in these communities. Moreover, we lack data on utilization and experiences of other community and social services or child welfare agencies.

Despite these limitations, we demonstrate that implementing a simplified assessment tool for OENs focusing on normal newborn behaviors and adopting as needed intermittent postnatal opioid treatment can rapidly transform care and significantly decrease length of birth hospitalization and postnatal treatment with opioid medication. The ESC approach can be successfully applied in both Level II and Level IV, larger- and smaller-volume hospital settings to standardize care. In addition, the ESC approach appears to be effective in newborns with multiple prenatal substance exposures in addition to opioids. Readmissions related to neonatal opioid withdrawal do not appear to be increased using this approach. Longer term outcome studies are needed to identify the full impact of these interventions at birth.

References

Haight SC, Ko JY, Tong VT, Bohm MK, Callaghan WM. Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization—United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:845–9. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6731a1.

Winkelman TNA, Villapiano N, Kozhimannil KB, Davis MM, Patrick SW. Incidence and costs of neonatal abstinence syndrome among infants with medicaid: 2004–2014. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20173520.

Sanlorenzo LA, Stark AR, Patrick SW. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: an update. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2018;30:182–6.

Heroin Response Work Group. Heroin in Colorado 2018: Law Enforcement Public Health Treatment Data 2018;2011–6. http://www.corxconsortium.org/heroin-response-work-group.

Brown J. Colorado grapples with 80 percent jump in newborns going through opioid withdrawal: Pueblo hospital’s number of drug-addicted babies makes others “shudder.” Denver Post; November 29, 2017.

Strahan AE, Guy GP, Bohm M, Frey M, Ko JY. Neonatal abstinence syndrome incidence and health care costs in the United States, 2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:200–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4791.

Bogen DL, Whalen BL, Kair LR, Vining M, King BA. Wide variation found in care of opioid-exposed newborns. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17:374–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.10.003.

Wachman EM, Schiff DM, Silverstein M. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2018;319:1362–74. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2640.

Clemans-Cope L, Holla N, Lee HC, Shufei Cong A, Castro R, Chyi L, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome management in California birth hospitals: results of a statewide survey. J Perinatol. 2020;40:463–72. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-019-0568-6.

Davis JM, Shenberger J, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Hudak M, Wachman EM, et al. Comparison of safety and efficacy of methadone vs morphine for treatment of neonatal abstinence syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:741–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1307.

Taleghani AA, Isemann BT, Rice WR, Ward LP, Wedig KE, Akinbi HT. Buprenorphine pharmacotherapy for the management of neonatal abstinence syndrome in methadone‐exposed neonates. Paediatr Neonatal Pain. 2019;1:33–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pne2.12008.

Grossman MR, Berkwitt AK, Osborn RR, Xu Y, Esserman DA, Shapiro ED, et al. An initiative to improve the quality of care of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20163360. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3360.

Grossman MR, Lipshaw MJ, Osborn RR, Berwitt AK. A novel approach to assessing infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Hosp Pediatr. 2018;8:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0128.

Colorado Health Institute report. Drug overdoses deaths in colorado increase. 2018. https://www.coloradohealthinstitute.org/research/death-drugs. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

Hwang SS, Weikel B, Adams J, Bourque SL, Cabrera J, Griffith N. et al. The colorado 407 hospitals substance exposed newborn quality improvement collaborative:408 standardization of care for opioid-exposed newborns shortens length of stay and 409 reduces number of infants requiring opiate therapy.Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10:783–291. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2020-0032.

Colorado Hospital Substance Exposed Newborns Quality Improvement Collaborative, CHoSEN QIC. https://www.chosencollaborative.org. Accessed 16 June 2020.

Johnson MR, Nash DR, Laird MR, Kiley RC, Martinez MA. Development and implementation of a pharmacist-managed, neonatal and pediatric, opioid-weaning protocol. J Pediatr Pharm Ther. 2014;19:165–73. https://doi.org/10.5863/1551-6776-19.3.165.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81.

Provost LP, Murray SK. The health care data guide: learning from data for improvement. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2011.

Xiao F, Yan K, Zhou W. Methadone versus morphine treatment outcomes in neonatal abstinence syndrome: a meta-analysis. J Paediatr Child Health. 2019;55:1177–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.14609.

Czynski AJ, Davis JM, Dansereau LM, Engelhardt B, Marro P, Bogen DL, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of neonates randomized to morphine or methadone for treatment of neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Pediatr. 2020;219:146–51.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.12.018.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff and providers at both hospitals for their enthusiastic support of the project and excellent patient care, and the QI teams for their leadership, particularly Victoria Del Valle, RNC, CNS at Memorial and Stephanie Shaver, RNC at Parkview for their work on project implementation.

Funding

University of Colorado School of Medicine Upper Payment Limit Program; Custodial Funds from the Colorado Attorney General’s Office; The COPIC Foundation; The Caring for Colorado Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SFT conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted data, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. CDH conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted data, critically reviewed and edited the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. BW carried out the analysis, interpreted the data, critically reviewed and edited the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. SSH conceptualized and designed the study, supervised the data analysis and interpreted data, critically reviewed and edited the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests or conflicts of interest. The Colorado Multiple Institutions Review Board (COMIRB) reviewed the study, and approved as exempt as a QI project. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Townsend, S.F., Hodapp, C.D., Weikel, B. et al. Shifting the care paradigm for opioid-exposed newborns in Southern Colorado. J Perinatol 41, 1372–1380 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-020-00900-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-020-00900-y