Abstract

Objective

Shared decision-making (SDM) between parents facing extremely preterm delivery and the medical team is recommended to develop the best course of action for neonatal care. We aimed to describe the creation and testing of a literature-based checklist to assess SDM practices for consultation with parents facing extremely preterm delivery.

Study design

The checklist of SDM counseling behaviors was created after literature review and with expert consensus. Mock consultations with a standardized patient facing extremely preterm delivery were performed, video-recorded, and scored using the checklist. Intraclass correlation coefficients and Cronbach’s alpha were calculated.

Result

The checklist was moderately reliable for all scorers in aggregate. Differences existed between subcategories within classes of scorer, and between scorer classes. Agreement was moderate between expert scorers, but poor between novice scorers. Internal consistency of the checklist was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93).

Conclusion

This novel checklist for evaluating SDM shows promise for use in future research, training, and clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parents facing extremely preterm delivery (before 25 weeks gestation) partner with neonatologists and obstetricians to make decisions for the care of their children. Antenatal counseling in the setting of extreme prematurity serves to provide information to those parents to support them in making resuscitation choices for their infant [1]. The key components for counseling a parent facing extremely preterm delivery vary based on the individual circumstances surrounding the pregnancy and expected delivery. How these components are addressed during the consultation may change depending on patient characteristics, health professional preferences, and clinical circumstances surrounding the encounter [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Sometimes the topics that seem essential to the counseling physician may be irrelevant, at best, or harmful, at worst, in the view of the expectant parent. As such, no single approach to antenatal counseling will be effective for all families. Shared decision-making (SDM) is therefore recommended to facilitate integration of parental values with the medical knowledge and experience of physicians during the antenatal consultation.

While widely accepted as the appropriate approach to making difficult decisions with unclear consequences, SDM is difficult to define and enact in routine practice [8, 9]. Implementation of SDM presents a unique set of challenges in counseling for extremely preterm delivery, including uncertainty about survival and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes, need for emergent delivery precluding consultation, environmental factors such as hospital resources, and healthcare professional attitudes toward SDM [1, 4, 7, 10]. Discussions may also be shaped more by local policy than patient characteristics. Many institutions have implemented formal policies regarding antenatal counseling; however, the evidence for how to ensure that SDM between physicians and expectant parents occurs during these consultations remains weak [3, 7, 11,12,13]. Further complicating this practice is the variability of education and training that neonatologists undergo regarding antenatal counseling in general [10, 14, 15]. Training in communication has been reported by neonatal-perinatal fellows to be a priority, but often not given much dedicated time in a busy didactic calendar [10].

Little is known about how neonatologists perform SDM in antenatal counseling for extremely premature deliveries. Counseling tools often target the provision of information rather than the more holistic the process of SDM. Instruments that have been used to assess the process of SDM have previously been found to lack evidence regarding measurement quality [16]. Several tools have been proposed to aid in the assessment of SDM by health professionals and patients, but these have largely been unvalidated for use in counseling parents facing extremely preterm delivery [17,18,19]. Information on what components of SDM are important to parents facing extremely preterm birth are lacking, in part due to the challenges of assessing components of SDM in this setting.

Several approaches exist for investigating the validity of an assessment. A dominant framework that is commonly cited is that described by Messick [20]. This framework, which defines five sources of validity evidence for assessment, was utilized in the development of the checklist. The purpose of this study was to develop and test a checklist to assess discrete components of SDM during antenatal consultation encounters for parents facing extremely preterm delivery.

Methods

Checklist development

This SDM checklist was developed and assessed for validity using Messick’s framework [20]. This framework evaluates five sources of validity evidence: content, response process, internal structure, relations to other variables, and consequences. Specifically, this phase of the checklist development and testing focused on the first three sources of validity evidence. To address the content source of validity, a review of the literature was performed to understand what is known about SDM for neonates born extremely premature. A search of the literature was performed using the PubMed database for English language publications from 2009 to 2019 with search terms “shared decision making + neonatology;” “shared decision making + obstetrics + prematurity;” and “shared decision making + obstetrics + periviable.”

References from the returned articles were cross-checked for additional relevant sources. Study team members reviewed the returned titles/abstracts for relevance and selected articles related to antenatal consultation for inclusion in the review. A deductive qualitative thematic analysis using a priori constructed categories was conducted on the remaining articles, and extracted themes were sorted into three primary categories related to SDM - setting up the consult, conveying information, and decision-making components [21]. Informed by these themes, the research team developed 34 discrete components of SDM to be included in the checklist. Component items were grouped by theme and ordered in a sequence in which they may be encountered during a consultation for ease of use. The checklist and reference articles for each item are found in Fig. 1.

Revised checklist with articles referenced in development of each [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109] checklist component.

Checklist evaluation

To further refine and evaluate the reliability of the checklist, a prospective cohort of neonatologists consented to provide antenatal consultation during video-recorded simulated encounters between June 2021 and May 2022. Neonatologists at four participating centers within the United States were eligible for inclusion in the study. This study operated under the individual Institutional Review Boards and with cooperative agreements between NorthShore University HealthSystem Evanston Hospital and the other participating centers. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

A standardized patient was conceptualized depicting a woman facing possible premature delivery at 22 0/7 weeks gestation after preterm, premature rupture of membranes. Throughout the video-recorded consultations, one of two actors portrayed the standardized patient, providing consistency in the role. Prior to the consultation, participants were given basic information about the patient and were encouraged to prepare for the session as they would in their standard practice. They were asked to assume that their center had no set guidelines regarding resuscitation of infants at 22 weeks gestational age.

Checklist validation and statistical analysis

Checklist consistency and internal validity were assessed in an iterative process by eight independent scorers using the tool to score the video-recorded mock consultations. Scorers consisted of four attending neonatologists who participated in the initial development of the SDM checklist (experts) and four additional scorers who did not participate in checklist development (novices). Novices consisted of one attending neonatologist, two neonatology fellows, and one pediatric resident. Each scorer underwent standardized training with the study team leads. Training consisted of viewing a video-recorded consultation that was not part of the study sample and using the checklist to assess the components of that consultation as a group with direct feedback provided by one of the checklist developers. Additional examples were discussed to further clarify the intent of the items. This allowed for further clarification of the scoring process and for standardization of the interpretation of each item, following the response process of Messick’s framework [20]. Using the checklist, each scorer assessed all video-recorded mock consultations and entered scores into a REDCap electronic data capture tool hosted at the coordinating center [22, 23].

Aligning with the internal structure source of Messick’s validity framework, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated using a two-way random-effects model to assess inter-rater agreement for each item, subcategory, and the checklist in its entirety. A range of ICC values between 0.5 and 0.75 represented moderate reliability, which was a priori deemed to be acceptable for this relatively “moderate stakes” evaluation tool [24]. Internal consistency, or the extent of inter-relatedness of the items within the test, was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha [25]. Calculations were performed using Excel (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA).

Following the first round of scoring, individual checklist components with low ICC were further evaluated for clarity and reworded or removed as necessary based on study team consensus. Redundant items were eliminated or combined to further simplify the checklist. Additional training to familiarize scorers was performed. The revised checklist was then utilized to re-score the 14 original mock consultations and applied to score 8 new mock consultations.

Results

Ultimately, 88 articles were reviewed and used to create 33 checklist items. Items were divided between three primary categories - setting up the consult, conveying information, and decision-making components. Six items were removed based on feedback from the rating team and analysis that showed poor agreement between scorers on certain items after the first round of scoring. Five items were from the “conveying information” category (addresses bias, options/choices, quality of life, parent role in the NICU, and family needs); the final item was from the “decision making” category (decision aid). The finalized checklist containing 27 items and supporting references are found in Fig. 1.

Mock consultation videos performed by 22 neonatologists were independently scored by the eight scorers, yielding 176 sets of consultation scores. Participant neonatologists represented 4 centers total. Demographic information of neonatologists providing mock consultations is reported in Table 1. Median duration of practice was 9 years (range 0–40 years). Fifty percent were male. Most (n = 12) performed consultations for expected extremely preterm delivery a few times per year.

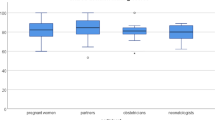

The results of mock consultation evaluation with the revised checklist are shown in Table 2. Component ICCs for the checklist were calculated. Following data analysis of the initial modified checklist, individual component item performance was assessed. The six items deemed most difficult to assess based upon lowest ICCs were removed and data analysis was repeated. Expert (ICC = 0.68) and novice (ICC = 0.52) scorers demonstrated moderate inter-rater reliability for the checklist, in keeping with the pre-defined acceptable level of reliability. Setting up components were most reliable among both expert and novice scorers, while decision making components were least reliable. Internal consistency of the checklist was high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93).

Discussion

In this study we describe the development and testing of a checklist for assessment of the SDM process in counseling parents facing extremely preterm delivery. Using the framework described by Messick, we produced a checklist of items with a strong construct validity that demonstrated moderate reliability for the overall process of SDM in such encounters [20]. This novel checklist shows promise for helping to evaluate the shared decision-making process in future research and clinical practice.

Our initial checklist consisted of 33 items grouped into 3 primary categories - setting up the consult, conveying information, and decision-making components. Following initial testing and review with feedback from the checklist developers and scorers, five items from the “conveying information” category were removed. “Addresses bias” was determined to be difficult to assess. “Options/choices” and “parent role in the NICU” were determined to be information items, and not related to the actual practice of conveying information (included in another checklist performed concurrent to this study). “Quality of life” was felt to be included in the “uncertainty” item, as well as in the “Goals/fears for baby” and was therefore redundant. “Family needs” was similarly incorporated into the “individualizes information” item. From the “decision making” category the “decision aid” item was removed, as there was disagreement among the scorers as to what constituted a decision aid vice an information aid; the items were therefore combined. While still considered to be important and possibly included in antenatal consultations, the difficulty in assessment of these items led to their modification or exclusion from the final checklist.

Shared decision-making supports parents in making decisions with unclear consequences and when no clear answer exists, such as in the case of extreme prematurity [1]. Essential components of SDM include recognizing and acknowledging that a decision is required, knowing and understanding the best available evidence, and incorporating the patient's/family’s values and preferences into the decision [26]. It is important to consider that the parents’ expectations of the purpose of the consultation may differ from that of the counseling physician and should be assessed to ensure effective collaboration. Despite the recommendation to include SDM in antenatal counseling, no established methods have previously existed for assessing this process. Thus, this validated checklist for evaluating the discrete components of this process may serve as a valuable tool for assessing which components of SDM are most important to parents. While clinical tools exist for assessing the extent to which patients are involved in the process of decision-making, (e.g., the SDM-Q-9 and SDM-Q-Doc, and the OPTION scale) [18, 19], evaluation of these rating scales has been performed primarily in the outpatient setting and most commonly in the adult population. While they contain many similar components to our checklist, they lack some of the specificity to the antenatal consult that are uniquely important to decision making for extremely preterm infants.

This checklist may be immediately helpful in the clinical setting. Levels of instruction in communication skills are variable in neonatology training, despite its importance in caring for extremely preterm infants [11]. A validated checklist for evaluating the use of SDM when conducting antenatal consultations could improve the content of those consultations, increase the level of comfort of those providing consultations, and improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the antenatal consultation process. By providing an objective tool, learners and experienced clinicians alike can be observed conducting consultations with real or mock patients and given specific feedback related to performance.

Our study consisted of a cohort of neonatologists from four geographically distinct institutions. This geographic variation in practice sites and neonatologist characteristics may increase the generalizability of our study. Additionally, recruiting physicians with differing clinical and demographic backgrounds mirrors the circumstances often encountered in clinical practice. The use of a mock patient during simulated encounters has been shown to closely mimic real-world behavior, further adding to the strength of our findings [27,28,29,30]. The purpose of this study was not to promote a prescriptive, “how-to” plan for conducting antenatal consultations for parents facing extremely preterm delivery. Rather, the objective was to describe the creation of a checklist that may reliably assess the SDM components present in an observed consultation to aid in future research and clinical teaching efforts.

While based on literature which included studies of parental perspectives, the next steps to test the validity of this checklist involve examining if presence of behaviors in the checklist correlate to parental satisfaction. Understanding what components of antenatal consultation are important to parents facing extremely preterm birth will afford clinicians the opportunity to focus on those aspects to optimize the delivery of counseling to those families. To this end, we plan to evaluate parental attitudes toward satisfaction with SDM as it relates to extremely preterm delivery by having parents view the same video-recorded consults and provide feedback. This will allow for further validity of the tool as it will address the element of “relationship to other variables” within Messick’s framework [20]. By allowing parents to view these same mock consultations, their feedback can be compared to overall scores and individual checklist items to assess which elements of SDM are most meaningful for parents in being able to make decisions for their children. Since the goal of the antenatal consultation is to adapt to parental needs and empower them through a personalized decision-making process, ensuring that healthcare providers focus on components that are demonstrated to be more important to parents is key to effective consultations [3]. Additional studies are planned to assess parental attitudes related to satisfaction with the SDM process, preparedness to make a decision following consultation, and feelings of inclusion in the decision-making process and integration into the healthcare team (Messick’s “consequences”) [20]. Through incorporation of validated observations of counseling components using our checklist, it may be possible to better generalize what constitutes a meaningful consultation for parents facing extremely preterm birth.

Conclusion

This novel checklist to evaluate the SDM process in antenatal counseling for parents facing extremely preterm delivery demonstrates moderate reliability among scorers of different experience levels. This may serve as a useful tool to objectively assess perinatal consultations for components that are important to parents facing extremely preterm delivery and can be used to guide training in conducting these consultations. Future investigation includes parental assessments of the same video-recorded mock consultations to provide external validation of the checklist items, and parent opinions on the quality of the consultations.

Data availability

All data used in this study and in the creation of this manuscript are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Cummings J.Committee on Fetus and Newborn Antenatal counseling regarding resuscitation and intensive care before 25 weeks of gestation. Pediatrics. 2015;136:588–95. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2336.

Duffy D, Reynolds P. Babies born at the threshold of viability: attitudes of paediatric consultants and trainees in South East England. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:42–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01975.x.

Geurtzen R, van Heijst A, Draaisma J, Ouwerkerk L, Scheepers H, Woiski M, et al. Professionals’ preferences in prenatal counseling at the limits of viability: a nationwide qualitative Dutch study. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176:1107–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-017-2952-6.

Geurtzen R, Van Heijst A, Hermens R, Scheepers H, Woiski M, Draaisma J, et al. Preferred prenatal counselling at the limits of viability: a survey among Dutch perinatal professionals. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1644-6.

Geurtzen R, van Heijst AFJ, Draaisma JMT, Kuijpers LJMK, Woiski M, Scheepers HCJ, et al. Development of nationwide recommendations to support prenatal counseling in extreme prematurity. Pediatrics. 2019;143. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3253.

Haward MF, Gaucher N, Payot A, Robson K, Janvier A. Personalized decision making: practical recommendations for antenatal counseling for fragile neonates. Clin Perinatol. 2017;44:429–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2017.01.006.

Raju TN, Mercer BM, Burchfield DJ, Joseph GF Jr. Periviable birth: executive summary of a joint workshop by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:406–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.02.027.

Barton JL, Kunneman M, Hargraves I, LeBlanc A, Brito JP, Scholl I, et al. Envisioning shared decision making: a reflection for the next decade. MDM Policy Pract. 2020;5:2381468320963781. https://doi.org/10.1177/2381468320963781.

Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JC. Shared decision making: concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:1172–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.022.

Boss RD, Hutton N, Donohue PK, Arnold RM. Neonatologist training to guide family decision making for critically ill infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:783–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.155.

Feltman DM, Williams DD, Carter BS. How are neonatology fellows trained for antenatal periviability counseling? Am J Perinatol. 2017;34:1279–85. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1603317.

Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, Das A, Hintz SR, Stoll BJ, et al. Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N. Engl J Med. 2015;372:1801–11. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1410689.

Krick JA, Feltman DM. Neonatologists’ preferences regarding guidelines for periviable deliveries: do we really know what we want? J Perinatol. 2019;39:445–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-019-0313-1.

Stokes TA, Watson KL, Boss RD. Teaching antenatal counseling skills to neonatal providers. Semin Perinatol. 2014;38:47–51. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2013.07.008.

Daboval T, Ferretti E, Moussa A, van Manen M, Moore GP, Srinivasan G, et al. Needs assessment of ethics and communication teaching for neonatal perinatal medicine programs in Canada. Paediatr Child Health. 2019;24:e116–e24. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxy108.

Légaré F, Adekpedjou R, Stacey D, Turcotte S, Kryworuchko J, Graham ID, et al. Interventions for increasing the use of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7:CD006732. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub4.

Kriston L, Scholl I, Hölzel L, Simon D, Loh A, Härter M. The 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9). Development and psychometric properties in a primary care sample. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:94–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.034.

Doherr H, Christalle E, Kriston L, Härter M, Scholl I. Use of the 9-item shared decision making questionnaire (SDM-Q-9 and SDM-Q-Doc) in intervention studies—a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0173904. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173904.

Edwards ElwynG, Wensing A, Hood M, Atwell K, Grol C. R. Shared decision making: developing the OPTION scale for measuring patient involvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:93–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.12.2.93.

Messick S Validity. In: Linn R, ed. Educational measurement. 3rd ed. New York: American Council on Education and Macmillan; 1989. p. 13–104.

Kiger ME, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med Teach. 2020;42:846–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42:377–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inf. 2019;95:103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208.

Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15:155–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012.

Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:53–5. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd.

Lemyre B, Daboval T, Dunn S, Kekewich M, Jones G, Wang D, et al. Shared decision making for infants born at the threshold of viability: a prognosis-based guideline. J Perinatol. 2016;36:503–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.81.

Boss RD, Urban A, Barnett MD, Arnold RM. Neonatal critical care communication (NC3): training NICU physicians and nurse practitioners. J Perinatol. 2013;33:642–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2013.22.

Meyer EC, Brodsky D, Hansen AR, Lamiani G, Sellers DE, Browning DM. An interdisciplinary, family-focused approach to relational learning in neonatal intensive care. J Perinatol. 2011;31:212–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2010.109.

Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, Fryer-Edwards KA, Alexander SC, Barley GE, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:453–60. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.5.453.

Flanagan OL, Cummings KM. Standardized patients in medical education: a review of the literature. Cureus. 2023;15:e42027. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.42027.

Janvier A, Barrington K, Farlow B. Communication with parents concerning withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining interventions in neonatology. Semin Perinatol. 2014;38:38–46. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2013.07.007.

Janvier A, Lantos J. Investigators P. Ethics and etiquette in neonatal intensive care. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:857–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.527.

Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5:302–11. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302.

Lantos JD. Ethical problems in decision making in the neonatal ICU. N. Engl J Med. 2018;379:1851–60. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1801063.

Miquel-Verges F, Woods SL, Aucott SW, Boss RD, Sulpar LJ, Donohue PK. Prenatal consultation with a neonatologist for congenital anomalies: parental perceptions. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e573–9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-2865.

Gorgos A, Ghosh S, Payot A. A shared vision of quality of life: partnering in decision-making to understand families’ realities. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2019;29:14–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prrv.2018.09.003.

Hasegawa SL, Fry JT. Moving toward a shared process: the impact of parent experiences on perinatal palliative care. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:95–100. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2016.11.002.

Grobman WA, Kavanaugh K, Moro T, DeRegnier RA, Savage T. Providing advice to parents for women at acutely high risk of periviable delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:904–09. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181da93a7.

Stokes TA, Kukora SK, Boss RD. Caring for families at the limits of viability: the education of Dr Green. Clin Perinatol. 2017;44:447–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2017.01.007.

Tucker Edmonds B, McKenzie F, Panoch JE, Barnato AE, Frankel RM. Comparing obstetricians’ and neonatologists’ approaches to periviable counseling. J Perinatol. 2015;35:344–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2014.213.

Warrick C, Perera L, Murdoch E, Nicholl RM. Guidance for withdrawal and withholding of intensive care as part of neonatal end-of-life care. Br Med Bull. 2011;98:99–113. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldr016.

Marty CM, Carter BS. Ethics and palliative care in the perinatal world. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;23:35–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2017.09.001.

French KB. Care of extremely small premature infants in the neonatal intensive care unit: a parent’s perspective. Clin Perinatol. 2017;44:275–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2017.01.008.

Daboval T, Shidler S. Ethical framework for shared decision making in the neonatal intensive care unit: Communicative ethics. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19:302–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/19.6.302.

Carter BS. More than medication: perinatal palliative care. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105:1255–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13529.

Kett JC. Prenatal consultation for extremely preterm neonates: ethical pitfalls and proposed solutions. J Clin Ethics. 2015;26:241–9.

Young E, Tsai E, O’Riordan A. A qualitative study of predelivery counselling for extreme prematurity. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;17:432–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/17.8.432.

D’Aloja E, Floris L, Muller M, Birocchi F, Fanos V, Paribello F, et al. Shared decision-making in neonatology: an utopia or an attainable goal? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:56–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2010.509913.

Kharrat A, Moore GP, Beckett S, Nicholls SG, Sampson M, Daboval T. Antenatal consultations at extreme prematurity: a systematic review of parent communication needs. J Pediatr. 2018;196:109–15.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.10.067.

Payot A, Gendron S, Lefebvre F, Doucet H. Deciding to resuscitate extremely premature babies: how do parents and neonatologists engage in the decision? Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1487–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.016.

Paulmichl K, Hattinger-Jurgenssen E, Maier B. Decision-making at the border of viability by means of values clarification: a case study to achieve distinct communication by ordinary language approach. J Perinat Med. 2011;39:595–603. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm.2011.066.

Stanak M, Hawlik K. Decision-making at the limit of viability: the Austrian neonatal choice context. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:204. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1569-5.

Guillén Ú, Mackley A, Laventhal N, Kukora S, Christ L, Derrick M, et al. Evaluating the use of a decision aid for parents facing extremely premature delivery: a randomized trial. J Pediatr. 2019;209:52–60.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.02.023.

de Wit S, Donohue PK, Shepard J, Boss RD. Mother-clinician discussions in the neonatal intensive care unit: agree to disagree? J Perinatol. 2013;33:278–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2012.103.

Hall SL, Hynan MT, Phillips R, Lassen S, Craig JW, Goyer E. The neonatal intensive parenting unit: an introduction. J Perinatol. 2017;37:1259–64. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2017.108.

Bohnhorst B, Ahl T, Peter C, Pirr S. Parents’ prenatal, onward, and postdischarge experiences in case of extreme prematurity: when to set the course for a trusting relationship between parents and medical staff. Am J Perinatol. 2015;32:1191–7. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1551672.

Daboval T, Ward N, Schoenherr JR, Moore GP, Carew C, Lambrinakos-Raymond A, et al. Testing a communication assessment tool for ethically sensitive scenarios: protocol of a validation study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8:e12039. https://doi.org/10.2196/12039.

Prentice TM, Gillam L, Davis PG, Janvier A. The use and misuse of moral distress in neonatology. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;23:39–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2017.09.007.

Tucker Edmonds B, McKenzie F, Fadel WF, Matthias MS, Salyers MP, et al. Using simulation to assess the influence of race and insurer on shared decision making in periviable counseling. Simul Health. 2014;9:353–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000049.

Tomlinson MW, Kaempf JW, Ferguson LA, Stewart VT. Caring for the pregnant woman presenting at periviable gestation: acknowledging the ambiguity and uncertainty. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:529.e1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.858.

Mercer BM, Barrington KJ. Delivery in the periviable period. Clin Perinatol. 2017;44:xix–xx. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2017.03.001.

Guillen U, Kirpalani H. Ethical implications of the use of decision aids for antenatal counseling at the limits of gestational viability. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;23:25–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2017.10.002.

Weiss EM, Magnus BE, Coughlin K. Factors associated with decision-making preferences among parents of infants in neonatal intensive care. Acta Paediatr. 2019;108:967–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14735.

Sidgwick P, Harrop E, Kelly B, Todorovic A, Wilkinson D. Fifteen-minute consultation: perinatal palliative care. Arch Dis Child Educ Pr Ed. 2017;102:114–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2016-310873.

Ruthford E, Ruthford M, Hudak ML. Parent-physician partnership at the edge of viability. Pediatrics 2017;139: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3899.

Barker C, Dunn S, Moore GP, Reszel J, Lemyre B, Daboval T. Shared decision making during antenatal counselling for anticipated extremely preterm birth. Paediatr Child Health. 2019;24:240–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxy158.

Boss RD, Hutton N, Sulpar LJ, West AM, Donohue PK. Values parents apply to decision-making regarding delivery room resuscitation for high-risk newborns. Pediatrics. 2008;122:583–9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-1972.

Tucker Edmonds B, McKenzie F, Panoch JE, Wocial LD, Barnato AE, Frankel RM. “Doctor, what would you do?”: physicians’ responses to patient inquiries about periviable delivery. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:49–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.09.014.

Superdock AK, Barfield RC, Brandon DH, Docherty SL. Exploring the vagueness of Religion & Spirituality in complex pediatric decision-making: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0360-y.

Haward MF, Janvier A. An introduction to behavioural decision-making theories for paediatricians. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:340–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12948.

Srinivas SK. Periviable births: communication and counseling before delivery. Semin Perinatol. 2013;37:426–30. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2013.06.028.

Janvier A, Lorenz JM, Lantos JD. Antenatal counselling for parents facing an extremely preterm birth: limitations of the medical evidence. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101:800–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02695.x.

Streiner DL, Saigal S, Burrows E, Stoskopf B, Rosenbaum P. Attitudes of parents and health care professionals toward active treatment of extremely premature infants. Pediatrics. 2001;108:152–7. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.1.152.

Janvier A, Farlow B, Verhagen E, Barrington K. End-of-life decisions for fragile neonates: navigating between opinion and evidence-based medicine. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017;102:F96–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2016-311123.

Janvier A, Farlow B, Baardsnes J, Pearce R, Barrington KJ. Measuring and communicating meaningful outcomes in neonatology: a family perspective. Semin Perinatol. 2016;40:571–7. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2016.09.009.

Shaw C, Stokoe E, Gallagher K, Aladangady N, Marlow N. Parental involvement in neonatal critical care decision-making. Socio Health Illn. 2016;38:1217–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12455.

Haward MF, Kirshenbaum NW, Campbell DE. Care at the edge of viability: medical and ethical issues. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38:471–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2011.06.004.

Albersheim SG, Lavoie PM, Keidar YD. Do neonatologists limit parental decision-making authority? A Canadian perspective. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:801–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.09.007.

Navne LE, Svendsen MN. Careography: staff experiences of navigating decisions in neonatology in Denmark. Med Anthropol. 2018;37:253–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2017.1313841.

Sorin G, Vialet R, Tosello B. Formal procedure to facilitate the decision to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining interventions in a neonatal intensive care unit: a seven-year retrospective study. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:76 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0329-x.

Hendriks MJ, Lantos JD. Fragile lives with fragile rights: Justice for babies born at the limit of viability. Bioethics. 2018;32:205–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12428.

Murray PD, Esserman D, Mercurio MR. In what circumstances will a neonatologist decide a patient is not a resuscitation candidate? J Med Ethics. 2016;42:429–34. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2015-102941.

Shapiro MC, Donohue PK, Kudchadkar SR, Hutton N, Boss RD. Professional responsibility, consensus, and conflict: a survey of physician decisions for the chronically critically ill in neonatal and pediatric intensive care units. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18:e415–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000001247.

Batton D. Resuscitation of extremely low gestational age infants: an advisory committee’s dilemmas. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:810–1. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01753.x.

Blumenthal-Barby JS, Loftis L, Cummings CL, Meadow W, Lemmon M, Ubel PA. Should neonatologists give opinions withdrawing life-sustaining treatment? Pediatrics. 2016;138: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2585.

Janvier A, Lantos J, Aschner J, Barrington K, Batton B, Batton D, et al. Stronger and more vulnerable: a balanced view of the impacts of the nicu experience on parents. Pediatrics. 2016;138: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0655.

Boss RD, Donohue PK, Roter DL, Larson SM, Arnold RM. “This is a decision you have to make”: using simulation to study prenatal counseling. Simul Health. 2012;7:207–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e318256666a.

Arnolds M, Xu L, Hughes P, McCoy J, Meadow W. Worth a try? Describing the experiences of families during the course of care in the neonatal intensive care unit when the prognosis is poor. J Pediatr. 2018;196:116–22.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.12.050.

Batton DG, Committee on F, Newborn. Clinical report-Antenatal counseling regarding resuscitation at an extremely low gestational age. Pediatrics. 2009;124:422–7. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-1060.

Moore GP, Lemyre B, Daboval T, Ding S, Dunn S, Akiki S, et al. Field testing of decision coaching with a decision aid for parents facing extreme prematurity. J Perinatol. 2017;37:728–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2017.29.

Guillén Ú, Suh S, Munson D, Posencheg M, Truitt E, Zupancic JA, et al. Development and pretesting of a decision-aid to use when counseling parents facing imminent extreme premature delivery. J Pediatr. 2012;160:382–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.070.

Howe EG. How to help parents, couples, and clinicians when an extremely premature infant is born. J Clin Ethics. 2015;26:195–205.

Wilkinson D, Truog R, Savulescu J. In favour of medical dissensus: why we should agree to disagree about end-of-life decisions. Bioethics. 2016;30:109–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12162.

Arora KS, Miller ES. A moving line in the sand: a review of obstetric management surrounding periviability. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2014;69:359–68. https://doi.org/10.1097/OGX.0000000000000076.

de Boer JC, van Blijderveen G, van Dijk G, Duivenvoorden HJ, Williams M. Implementing structured, multiprofessional medical ethical decision-making in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Med Ethics. 2012;38:596–601. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2011-100250.

Tucker Edmonds B, Krasny S, Srinivas S, Shea J. Obstetric decision-making and counseling at the limits of viability. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:248.e1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.11.011.

Tucker Edmonds B, McKenzie F, Panoch JE, White DB, Barnato AE. A pilot study of neonatologists’ decision-making roles in delivery room resuscitation counseling for periviable births. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2016;7:175–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/23294515.2015.1085460.

Prentice TM, Gillam L. Can the ethical best practice of shared decision-making lead to moral distress? J Bioeth Inq. 2018;15:259–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-018-9847-8.

Weiss EM, Barg FK, Cook N, Black E, Joffe S. Parental decision-making preferences in neonatal intensive care. J Pediatr. 2016;179:36–41.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.08.030.

Weiss EM, Xie D, Cook N, Coughlin K, Joffe S. Characteristics associated with preferences for parent-centered decision making in neonatal intensive care. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:461–68. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5776.

Navne LE, Svendsen MN. A clinical careography: steering life-and-death decisions through care. Pediatrics. 2018;142:S558–66. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0478G.

D’Souza R, Shah PS, Sander B. Clinical decision analysis in perinatology. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:491–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13264.

Bucher HU, Klein SD, Hendriks MJ, Baumann-Hölzle R, Berger TM, Streuli JC, et al. Decision-making at the limit of viability: differing perceptions and opinions between neonatal physicians and nurses. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18:81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1040-z.

El Sayed MF, Chan M, McAllister M, Hellmann J. End-of-life care in Toronto neonatal intensive care units: challenges for physician trainees. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2013;98:F528–33. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-303000.

Gillam L, Sullivan J. Ethics at the end of life: who should make decisions about treatment limitation for young children with life-threatening or life-limiting conditions? J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47:594–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02177.x.

Bastek TK, Richardson DK, Zupancic JA, Burns JP. Prenatal consultation practices at the border of viability: a regional survey. Pediatrics. 2005;116:407–13. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-1427.

Kukora SK, Boss RD. Values-based shared decision-making in the antenatal period. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;23:17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2017.09.003.

Einaudi MA, Simeoni MC, Gire C, Le Coz P, Condopoulos S, Auquier P. Preterm children quality of life evaluation: a qualitative study to approach physicians’ perception. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:122. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-122.

Donohue PK, Boss RD, Aucott SW, Keene EA, Teague P. The impact of neonatologists’ religiosity and spirituality on health care delivery for high-risk neonates. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:1219–24. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2010.0049.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JK conceptualized the project, developed, and refined the checklist, performed data collection and analysis, and edited the manuscript. DF conceptualized the project, developed, and refined the checklist, performed data collection and analysis, and edited the manuscript. UA developed the checklist. PM developed the checklist. CLW performed data analysis and refined the checklist. EO performed data analysis and refined the checklist. KM performed data analysis and refined the checklist. CM performed data analysis. MG participated in data collection and analysis, refined the checklist, drafted the manuscript, and refined final edits. All authors participated in the final review of the paper and have approved this version of the manuscript as submitted. We take full responsibility for the reported research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study operated under the individual Institutional Review Boards and with cooperative agreements between NorthShore University HealthSystem Evanston Hospital and the other participating centers, project number EH19-360. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guindon, M., Feltman, D.M., Litke-Wager, C. et al. Development of a checklist for evaluation of shared decision-making in consultation for extremely preterm delivery. J Perinatol 45, 732–738 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-024-02136-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-024-02136-6