Abstract

Neonatal transports are essential for providing access to advanced intensive care treatment for sick and premature neonates. There is a lack of consensus of which core physiological variables, clinical parameters and quality metrics to report for clinical guidance during transport and clinical governance of transport systems. We performed a systematic literature review to identify which data variables are reported during neonatal transports and assess whether these variables are uniform and transferable across studies. In the final data extraction and quality appraisal, 108 studies were included. The studies were heterogenous, presented a large variation of registered variables and frequently lacked uniform definitions. Reaching consensus on a set of defined variables for registration and implementation internationally will enhance the opportunity to improve the safety, effectiveness and quality of care for these vulnerable neonates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Following an increased centralization of neonatal intensive care, neonatal transport services have become an integral part of the chain of care for neonates in need of advanced intensive care treatment and surgery. Although neonatal transports are often essential for providing access to specialised care, the transportation of premature neonates, or neonates with other critical conditions may potentially increase the burden on the patient [1, 2]. Factors including discontinuation of treatment, the competence of transport personnel and environmental exposure may all adversely affect clinical outcomes and negatively impact on patient trajectories [3, 4].

In order for neonatal transport services to be an integrated part of the intensive care pathway of the neonate it is imperative to ensure that the quality of care provided during transport mirrors the standard of care in the neonatal intensive care units [5]. This requires not only high standards of competency among transport personnel, but also conscientious evaluation of clinical signs and close attention to physiological variables monitored during transport [6]. Neonatal transports are often challenged by limitations such as confined spaces, continuous movement, and fluctuating environmental conditions. The inherent risks associated with transporting premature infants and those with critical conditions underscores the need for systematic and consistent evaluation of transport services [7].

There is a lack of consensus regarding which core physiological variables, clinical parameters and quality metrics should be reported in order to help clinical guidance during transport and clinical governance of transport systems. Variation in study design and the absence of uniform templates to define core quality metrics within neonatal transport makes the interpretation of results and evaluation of transport services difficult [8]. Benchmarking is increasingly used as a governance tool within healthcare and may stimulate to quality improvement [9]. Identifying a core set of variables that can be repeatedly measured over time is an important first step in quality improvement initiatives [10].

In this study, we performed a systematic literature review to identify which variables that are most commonly reported during neonatal transports. Furthermore, we aimed to investigate whether the reported variables are consistent and transferable, to inform the development of a uniform, universally accepted template for data reporting of neonatal transport.

Methods

This review is based on a systematic literature search following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11]. For PRISMA 2020 Checklist, see Appendix 1.

Eligibility criteria

We included literature describing data variables reported during neonatal transports. Original manuscripts, written in English or any of the Scandinavian languages and published after 1990 were included. Papers were excluded if they were without an abstract, editorials, comments and letters to the editors and book chapters.

Literature search strategy

We conducted a systematic search of MEDLINE/Pubmed, Embase, The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, Cochrane Library, Nursing Reference Centre Plus and SveMed + . A librarian set up and performed the literature search. The most recent update to the search was performed January 6th, 2025.

The two Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) entry terms, “Infant, Newborn” and “Transport” was used and combined. The first and second set of entry terms were combined using the Boolean operator AND. Detailed search strategy is provided in Appendix 2.

Selection process

The records from the literature search were imported into Covidence (www.covidence.org) [12]. All titles and abstracts were screened independently by two of the authors (MB and TSO). Publications that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria based on title and abstract were excluded. Potentially eligible articles were subject to independent screening by two authors in random pairs (MB, TSO, AL and MR). These articles were evaluated in full text using the inclusion and exclusion list. Articles not meeting the inclusions criteria were excluded with a reason. Disagreements were solved through discussion until consensus was reached (MB, TSO and MR).

Data collection process and data items

Data extraction was performed in Covidence (www.covidence.org) by the first author (MB) [12]. The predefined variables were based on previous templates in prehospital medicine and customized for neonatal transport [13, 14]. In case of uncertainty, TSO and MR were consulted. Disagreements were solved through discussion until consensus. A list of all variables collected are presented in Appendix 3.

Quality appraisal

For quality appraisal, we used a predefined checklist imported into Covidence (www.covidence.org) [12]. The checklist was based on the authors assumptions of what is important to report in neonatal transport studies, inspired by previous literature studies in prehospital medicine, the quality appraisal checklist in Covidence and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklists [15]. Quality appraisal of the included articles was conducted by two authors (MB and JH, MB and TSO or MB and MR). Uncertainty was solved through discussion until consensus.

Bias assessment

To reduce risk of selection bias, two authors screened title, abstract and full text, and independently conducted quality appraisal.

The heterogeneity of the extracted data made them unsuitable for quantitative synthesis and meta-analysis was therefore not performed [16].

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interests.

Results

Study selection

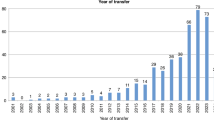

The literature search resulted in 2868 studies relevant for screening of title and abstract. Of these, 511 were selected for full text review. In total, 108 studies were included in the final data extraction and quality appraisal. The main reason for exclusion was lack of reported data from the transport phase (n = 219). Literature selection, including reasons for exclusion, are presented in the PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1). Included studies were conducted in Europe (n = 27, 25%), USA (n = 21, 19.4%), Australia (n = 16, 14.8%), Scandinavia (n = 13, 12%), UK (n = 11, 10.2%), Canada (n = 6, 5.6%) and 14 (12.7%) from other countries. They were published between 1991 and 2024. A complete reference list of all included studies is presented in Appendix 4.

Data extraction

Study characteristics

The most frequently used study design was cohort, with 101 (93.5%) studies. Cross sectional study designs were used in four studies, a randomized comparative study design in one study and a quantitative non-experimental design in one study. One randomized controlled trial met the inclusion criteria in this review. Most of the studies were retrospective (n = 80, 74%) while 28 (26%) were prospective. In 60 studies (55,6%) comparisons were made between two or more transported groups, whereas two studies (1.9%) compared transported neonates with inborn neonates. A complete list of all included studies and their characteristics is presented in Appendix 5.

Patients

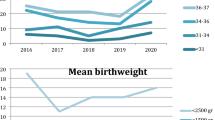

A total of 25,405 patients were included across the studies, with sample sizes ranging from 12 to 2402 patients. Baseline characteristics of the included patients were reported in 104 studies (96.3%), with gestational age being the most documented variable (n = 89, 82.4%). Diagnosis or medical problem were reported in 90 studies (83.3%). Other frequently reported variables were birth weight (BW), weight at day of transportation and gender (Fig. 2).

Transport characteristics and team composition

Among studies reporting on interhospital transports, the majority (n = 105, 97,2%) described transports to higher level of care. Transfers to lower level of care were reported in eleven studies (10.2%) and primary transfers were reported in six studies (5.6%). Of the 108 studies included, 98 (90.7%) reported the mode of transportation. In the remaining ten studies (9.3%), the type of transport vehicle was not specified.

Team composition was reported in 86 studies (79.6%). A physician was reported present in 71 (65.7%) studies and a nurse in 79 (73,1%). Fifteen studies reported transfers with a nurse and/or a paramedic present without a physician. Other professions reported to take part in neonatal transfers included respiratory therapist, paramedic, cardiopulmonary technician, medical technician, advanced nurse practitioners, neonatal nurse practitioners, transport specialist, surgery room or anaesthesiology technician, emergency technician, emergency care practitioners, fire rescue services and health care providers (unspecified).

Physiological data

Physiological data variables reported during transport were respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, end tidal CO2, transcutaneous CO2, heart rate, heart rate variability, blood pressure, and temperature (Fig. 3). How and how often a parameter is measured was heterogeneously reported. Ventilator settings were seldom reported in detail, except in studies focusing on different ventilator strategies during transport. Continuous automated data capture during transport was reported to be used in 10 studies, of which n = 5, (4.6%) reported on ventilator parameters.

Medications and procedures

Use of medication(s) was reported in 47 (43.5%) of the studies. Medications were reported both as pharmacological categories (n = 19, 17.6%) or as the specific drug (n = 9, 8.3%). Nineteen studies (17.6%) reported medications both as pharmacological categories and separate drugs. The most frequently reported pharmacological categories were sedation, analgesia, inotropes, vasopressors, neuromuscular blockers, antibiotics and anticonvulsants. Prostaglandin E and inhaled nitric oxide, reported in 13 studies (12%) and 6 studies (5.6%), respectively.

Medical procedures performed during transport were described with considerable heterogeneity across the included studies, with intubation being the most commonly reported procedure. Some studies reported procedures performed by the transport team but did not specify when they were done.

Scoring tools

Use of any scoring tool was reported in 14 (13%) of the included studies, and three studies reported using two scoring tools. A wide range of scoring tools were reported, with the Transport Risk Index of Physiologic Stability (TRIPS) being most frequently used (n = 6, 5.6%). Other scoring tools reported are presented in Table 1.

Time variables

One or more time variables were reported in 67 (62%) of the studies. The most frequent time variable reported was transportation time (n = 54, 50%). The other time variables reported were dispatch/reaction time (n = 13, 12%), mobilisation time (n = 7, 6.5%), stabilisation time (n = 29, 26.9%) and total time (n = 12, 11.1%) (Fig. 4). In 34 studies (31.5%) the time variables were clearly defined, yet these definitions were not uniform across studies.

Adverse events and complications

Adverse events were reported in 74 (68.5%) of the included studies. Clinical complications and clinical deterioration like temperature instability, hypo- or hyperthermia, desaturation, hypo- or hyperglycaemia, seizures, bradycardia, tachycardia, hypo- or hypertension, extubation, hypo- or hypercapnia, apnoea, and pneumothorax were reported in 63 (58.3%) studies. Equipment complications were reported in 31 (28.7%) studies, with the most frequent being ventilator complications. Other complications were related to oxygen supply, disconnections, battery failure or power loss. Transport complications like delay, vehicle problems, logistical and organisational problems were reported in 16 (14.8%) of the included studies. Included studies reported 10 deaths in total, during transport. This constitutes 0.04% of the 25,405 patients included in this review.

Quality appraisal

A summary of the results of the quality appraisal is depicted in Fig. 5. A clear aim or objective was reported in 107 (99.1%) of the included studies and 102 (94,4%) were considered to have a clearly described study design. Conflicts of interest were addressed in 71 (65.7%) of the studies, with 6 (5.6%) explicitly reporting a conflict. Seventy-four (68,5%) of the studies had either received approval from an ethics committee or were reported no to require an ethical approval according to the regulations. Handling of missing data were reported in 60 (55.6%) studies. None of the included studies used imputation techniques. Of the included studies, 90 (83.3%) studies we considered to be transferable to a high-income country setting. Those who did not meet these criteria were from low resource settings with a very different organisation of their services and equipment available. The full quality appraisal of all included studies is available in Appendix 6.

Discussion

This systematic literature review identified 108 studies reporting data variables during neonatal transports. Our main finding is that the studies are heterogenous, presenting a large variation of registered variables and frequently lack uniform definitions. This represents an obstacle when it comes to evaluating and comparing studies within this field.

Many transport studies only report data recorded before transport at the referring hospital and/or after arrival at the receiving hospital, 219 studies were excluded from the present analysis due to the absence of data from the actual transport phase. The absence of clinical data recorded during transport limits the ability to extract clinically relevant information for health care personnel involved in neonatal transport. Similarly, the opportunity to use the existing literature for clinical governance, evaluation and further development of the transport services is hampered by lack of uniformly reported and standardised data.

The majority of the studies included in this analysis reported baseline patient characteristics, which are essential for evaluating study transferability and external validity. The setting and organisation of the service, including description of transport vehicle and team composition were inconsistently described in the included studies. This can affect transferability of the results to other services and settings. Some studies did not report on type of transport vehicle or team composition. Service specific team composition, skills, equipment set-up, protocols, training and evaluation routines vary within each country and between countries [17,18,19,20,21]. The heterogeneous organisation of transport services complicates comparison of services and transports.

Transport of sick and preterm neonates is conducted within a challenging environment [22, 23]. Clinical assessment during transport can be difficult. Space and access to the neonate is limited and there are fewer health care personnel present than in the hospital. Clinical and physiological parameters are essential for the clinician to evaluate and guide treatment of the neonate and can also be used as a tool for clinical governance to see trends over time. Our study shows that physiological data during transport are not uniformly reported. There was variation in the level of detail provided regarding the frequency and the description of these physiological data, including both temperature and blood pressure. Consensus on standardised reporting of core physiological variables is essential to improve the evaluation of neonatal transports. To evaluate quality and identify areas for improvement within neonatal transport, it is imperative to measure data variables that are uniformly recorded throughout the entire trajectory, that is before transport at the delivering hospital, during transport and after transport at the receiving hospital. Transport should be considered an integrated part of clinical care, aiming for continuous treatment and consistent quality of documentation. To monitor trends in e.g. physiological parameters, a uniform set of valid variables with reliable data capture should be obtained.

Ten studies reported using automated data capture during transport, most of these were ventilator parameters. Automated data capture from ventilators and monitors has the potential to record continuous data more precisely than a human and is of particular importance when the clinician’s attention is focused on the care of the sick or preterm patient. The integration of artificial intelligence in patient monitoring has the potential for future improvement of both clinical guidance and governance.

Scoring tools are developed to evaluate the severity of the clinical condition of the neonate and to help predict morbidity and mortality at a group level [24,25,26]. Our review demonstrates infrequent and inconsistent use of these tools. Fourteen of the included studies reported using a scoring tool, but ten different scoring tools were identified.

Time variables for neonatal transport can provide important information in the evaluation of transport services yet need to be standardised to compare and merge data. Our review reveals great variation in the reporting of time variables. Furthermore, as previously described, these variables were heterogeneously defined, which further complicates comparison [21].

Adverse events are unwanted incidents or complications during transport ranging from minor organisational challenges to clinical deterioration of the neonate. It is important to thoroughly monitor these situations to be able to learn from them and aim for safer transports. Adverse events are previously reported to occur frequently on neonatal transports, both in hospital and out of hospital [4, 27, 28]. A wide spectrum of adverse events was reported during transport in the 74 (68.5%) studies who reported adverse events.

Neonates in need for transport represent a heterogenous case mix of patients [2]. Medical conditions and severity of illness vary, ranging from healthy neonates being returned to a lower level of care, to severely ill neonates in need of intensive care during transport. This variabilty represents an obstacle when comparing transport services. To avoid selection bias, case mix adjustment is pivotal. The neonatal patient population can be categorised into gestational age groups, by clinical condition or clinical risk indexes such as the CRIB score [29]. It has been suggested that neonatal transports can be stratified by level of care and categorised according to primary clinical and operational reason for transfer and required transfer timescale [30].

Several initiatives have aimed to establish a set of quality indicators and data variables for neonatal transport [31,32,33]. Evaluation and benchmarking transport services have been performed in some countries and show differences between the transport teams´ outcome [34]. Using a set of metrics to evaluate neonatal transports has been shown feasible [35]. Some transport services have addressed this issue by developing data sets to be reported by the included transport services, but to our knowledge, none of these templates are widely used outside the centres or countries where they were developed [30]. After development and consensus of data variables to be registered, we need to aim for implementing it internationally, across different transport services.

Limitations

This study, like most systematic reviews, carries inherent limitations. Despite independent screening of titles, abstracts, and full texts by two reviewers, some eligible studies may have been inadvertently excluded. Additionally, the development of the data extraction form and quality appraisal criteria, based on various sources and team discussions, may have led to the omission of relevant variables and reporting bias. Studies published in other languages than English or Scandinavian were excluded, which may have led to the omission of relevant studies published in other languages.

The studies included in this review span a prolonged time-period, which may have contributed to the heterogeneity observed across studies. We did not aim to assess temporal trends or convergence in the reporting of data variables over time.

Conclusions

Data variables reported in studies of neonatal transports are inconsistent and not uniformly defined. This lack of consistency represents an obstacle in the evaluation of the studies itself but also limits the ability to evaluate transport services and impose quality improvement initiatives. To agree on a set of defined variables to be registered and to implement such a template internationally would enhance the opportunity to learn from the transports and improve the safety, effectiveness and quality of care for these vulnerable neonates.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author upon request. A complete reference list of all included studies is presented in Appendix 4.

References

Moss SJ, Embleton ND, Fenton AC. Towards safer neonatal transfer: the importance of critical incident review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:729–32.

Schumacher S, Mitzlaff B, Mohrmann C, Fiedler KM, Heep A, Beske F, et al. Characteristics and special challenges of neonatal emergency transports. Early Hum Dev. 2024;192:106012.

Orr RA, Felmet KA, Han Y, McCloskey KA, Dragotta MA, Bills DM, et al. Pediatric specialized transport teams are associated with improved outcomes. Pediatrics. 2009;124:40–8.

Lim MT, Ratnavel N. A prospective review of adverse events during interhospital transfers of neonates by a dedicated neonatal transfer service. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9:289–93.

Whyte HE, Jefferies AL. The interfacility transport of critically ill newborns. Paediatr Child Health. 2015;20:265–75.

Ramnarayan P. Measuring the performance of an inter-hospital transport service. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:414–6.

Fenton AC, Leslie A, Skeoch CH. Optimising neonatal transfer. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F215–9.

Gray MM, Riley T, Greene ND, Mastroianni R, McLean C, Umoren RA, et al. Neonatal transport safety metrics and adverse event reporting: a systematic review. Air Med J. 2023;42:283–95.

Willmington C, Belardi P, Murante AM, Vainieri M. The contribution of benchmarking to quality improvement in healthcare. A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:139.

Rajapreyar P, Badertscher N, Willie C, Hermon S, Steward B, Meyer MT. Improving mobilization times of a specialized neonatal and pediatric critical care transport team. Air Med J. 2022;41:315–9.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj. 2021;372:n71.

Covidence. covidence.org Melbourne, Australia: Covidence; 2020 [cited 2020 11.05.20]. Available from: covidence.org.

Haugland H, Rehn M, Klepstad P. Kruger A. Developing quality indicators for physician-staffed emergency medical services: a consensus process. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2017;25:14.

Tønsager K, Krüger AJ, Ringdal KG, Rehn M. Template for documenting and reporting data in physician-staffed pre-hospital services: a consensus-based update. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2020;28:25.

(3V) OCfTVHL. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme 2020 [cited 2020 11.05.20]. Available from: casp-uk.net.

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5. In: Deeks J, JPT; H, Altman D, McKenzie J, Veroniki A, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 65. cochrane.org/handbook.: The Cochrane Collaboration; (2024).

Bellini C, De Angelis LC, Gente M, Bellù R, Minghetti D, Massirio P, et al. Neonatal air medical transportation practices in Italy: a nationwide survey. Air Med J. 2021;40:232–6.

Fenton AC, Leslie A. The state of neonatal transport services in the UK. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97:F477–81.

Heiring C, Zachariassen G, Christensen PS, Kjærgaard S, Nielsen HV, Hansen TG, et al. [Interhospital transport of sick newborns in Denmark]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2020;182.

Karlsen KA, Trautman M, Price-Douglas W, Smith S. National survey of neonatal transport teams in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128:685–91.

Lee KS. Neonatal transport metrics and quality improvement in a regional transport service. Transl Pediatr. 2019;8:233–45.

Bailey V, Szyld E, Cagle K, Kurtz D, Chaaban H, Wu D, et al. Modern neonatal transport: sound and vibration levels and their impact on physiological stability. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36:352–9.

Solvik-Olsen T, Bekkevold M, Heyerdahl F, Lang AM, Hagemo JS, Rehn M. Environmental factors and clinical markers of stress during neonatal transport: a systematic literature review. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2025;9:e003568.

Lee SK, Aziz K, Dunn M, Clarke M, Kovacs L, Ojah C, et al. Transport Risk Index of Physiologic Stability, version II (TRIPS-II): a simple and practical neonatal illness severity score. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30:395–400.

Qu W, Shen Y, Qi Y, Jiang M, Zheng X, Zhang J, et al. Comparison of four neonatal transport scoring methods in the prediction of mortality risk in full-term, out-born infants: a single-center retrospective cohort study. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181:3005–11.

Veloso FCS, Barros CRA, Kassar SB, Gurgel RQ. Neonatal death prediction scores: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2024;8:e003067.

Delacrétaz R, Fischer Fumeaux CJ, Stadelmann C, Rodriguez Trejo A, Destaillats A, Giannoni E. Adverse events and associated factors during intrahospital transport of newborn infants. J Pediatr. 2022;240:44–50.

van den Berg J, Olsson L, Svensson A, Hakansson S. Adverse events during air and ground neonatal transport: 13 years’ experience from a neonatal transport team in Northern Sweden. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1231–7.

Network TIN. The CRIB (clinical risk index for babies) score: a tool for assessing initial neonatal risk and comparing performance of neonatal intensive care units. Int Neonatal Netw Lancet. 1993;342:193–8.

Leslie A, Harrison C, Jackson A, Broster S, Clarke E, Davidson SL, et al. Tracking national neonatal transport activity and metrics using the UK Neonatal Transport Group dataset 2012-2021: a narrative review. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2024;109:460–6.

Bigham MT, Schwartz HP. Quality metrics in neonatal and pediatric critical care transport: a consensus statement. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:518–24.

Schwartz HP, Bigham MT, Schoettker PJ, Meyer K, Trautman MS, Insoft RM. Quality metrics in neonatal and pediatric critical care transport: a national delphi project. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16:711–7.

Bekkevold M, Solvik-Olsen T, Heyerdahl F, Lang AM, Hagemo J, Rehn M. Reporting interhospital neonatal intensive care transport: international five-step Delphi-based template. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2024;8:e002374.

Eliason SH, Whyte H, Dow K, Cronin CM, Lee S. Variations in transport outcomes of outborn infants among Canadian neonatal intensive care units. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30:377–82.

Marsinyach Ros I, Sanchez García L, Sanchez Torres A, Mosqueda Peña R, Pérez Grande MDC, Rodríguez Castaño MJ, et al. Evaluation of specific quality metrics to assess the performance of a specialised newborn transport programme. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;179:919–28.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Marie Isachsen, librarian at the Medical Library at Ullevål Hospital, University of Oslo, for excellent help in designing and performing the literature search.

Funding

The Norwegian Air Ambulance Foundation (SNLA) funded the study, but played no part in the study design, data collection, data analysis or manuscript preparation processes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Librarian Marie Isachsen constructed and performed the literature search. MB and TSO screened the papers on title and abstract. AL, MR, TSO and MB screened eligible papers in full text. MB conducted the data extraction. MB and JH/TSO/MR executed the quality appraisal. MB, TSO, AL, FH, JH and MR contributed to preparing the protocol and writing the manuscript. MB, TSO, AL, FH, JH and MR approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

No ethics approval is considered indicated, as this is a literature review only. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Registration and protocol The study protocol is registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews, PROSPERO (registration number CRD42020199020).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bekkevold, M., Solvik-Olsen, T., Lang, A.M. et al. Data variables reported during neonatal transport: a systematic literature review. J Perinatol 46, 6–11 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-025-02483-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-025-02483-y