Abstract

Families of infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) are at an increased risk for depression, anxiety, and trauma symptoms that often persist well beyond transition from the NICU. While NICU professionals provide vital medical care for high-risk infants, they also offer interdisciplinary support for families, including collaboration with psychosocial and psychiatric services in select settings. Despite psychosocial support systems often being present during NICU hospitalization, significant gaps remain in post-NICU mental health support for parents. Comprehensive discharge preparation and outpatient follow-up planning for infants, as well as their families, are essential to optimize both long-term outcomes and the well-being of the entire family unit. In this paper, we review current evidence regarding mental health risks for families during transitions of care and highlight practice recommendations and advocacy opportunities for enhanced family-centered, interdisciplinary follow-up care after transition from the NICU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An infant’s hospitalization in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is a potentially traumatic event (PTE), marked by fragmentation of the family unit [1]. Up to 50% of parents report emotional distress such as depression, anxiety, and acute stress or post-traumatic stress when their infants are hospitalized in the NICU [2]. Evidence suggests that these symptoms can persist for years after a NICU stay [3,4,5,6,7]. Yet, some parents may not recognize their evolving mental health needs nor be aware of available treatments unless this aspect is assessed during follow up care for their infant. In fact, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is highly prevalent in NICU parents, must be present for at least a month and takes time to diagnose, thereby increasing the importance of continued mental health screening and support after a NICU admission.

Family-infant separation was exacerbated in recent years in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting temporary restrictions on family presence in the NICU [8, 9]. Although these restrictions brought greater attention to the compounded trauma of family separation, a NICU hospitalization in and of itself had long been recognized to interrupt parent-infant bonding, create uncertainty regarding short- and long-term outcomes for the child, and alter parental roles [1]. The resulting stress contributes to negative downstream effects on both parents and infants [10], which may be reflected in lower cognitive performance in childhood, missed well-child visits and immunizations, and increased emergency department visits [11].

Family-centered developmental care (FCDC) programs within NICUs mitigate parental distress by improving parent-infant bonding. [12, 13] Examples of pertinent FCDC practices include shared decision-making with parents, incorporating parents into daily rounding, motivational interviewing, and encouraging parent ownership of responsibilities like skin-to-skin, human milk feeding, or daily infant care. When FCDC is not an integral, seamless component of NICU care, it can make the transition home from the NICU more stressful. Limited guidance is available regarding extending FCDC approaches beyond NICU discharge, whether to home or to another hospital unit, which has created a critical gap in provision of sustained support for the mental well-being of families impacted by a NICU hospitalization [7].

This gap is important to address because an infant’s transition from NICU to home is a highly stressful period for parents. While it brings family reunification, it is also marked by changes in relationships with members of the interdisciplinary care team, loss of interprofessional support, and social isolation, all while balancing other family and work responsibilities [14, 15]. In fact, NICU parents have described the transition home as a period of “pervasive uncertainty”, with worries surrounding their child, doubts about their parenting abilities, and relationship adjustments with partners and outpatient care teams [16]. Implementing strategies for comprehensive family support during and after care transitions, incorporating anticipatory guidance, follow-up appointments, and referrals to community resources, inclusive of appropriate family psychosocial support, is essential to effectively address these challenges [17].

In this paper, we outline factors that influence parental mental health outcomes during transition from NICU to home. We describe the current state of family psychosocial support after a NICU hospitalization and the challenges of optimizing well-being during transitions from the NICU. Finally, we provide recommendations to support family well-being during transitions from NICU based on current evidence, published expert opinions, and the expertise of parents and interdisciplinary NICU providers who developed the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Trainees and Early Career Neonatologists (TECaN) Carousel Care national advocacy campaign.

Factors influencing parental mental health outcomes during and after transitions

Awareness of perinatal mental health diagnoses and available treatments vary for parents impacted by the NICU. Some parents have received mental health diagnoses before a NICU admission and have existing treatment plans, but the majority of parents who are identified as experiencing mental health concerns during or after NICU admission have no prior history of mental health diagnoses [18]. This presents problems in access to mental healthcare during and after a NICU admission.

As a PTE, a child’s need for NICU care may naturally impact parent perceptions of their child’s future health and vulnerability [19]. Parents of children who have been hospitalized in the NICU rate their perceptions of child vulnerability (parental perception of child vulnerability, PPCV) much higher than parents of healthy term infants who do not require NICU admission. These perceptions can persist regardless of the illness severity of the child or the fact that the child might have stabilized enough to go home [20]. Altered parent perceptions of their child’s vulnerability and maladaptive parenting practices developed in response to trauma can result in the phenomenon of Vulnerable Child Syndrome (VCS) [21, 22]. VCS contributes to poor NICU graduate long-term health and developmental outcomes [21, 22]. A risk factor for VCS is having less family or social support [19].

Beyond VCS, health inequities have a detrimental effect on the mental health outcomes of families affected by the NICU. Disadvantaged families face additional stress during NICU admission and after transition to home, including barriers to parental involvement, which contribute to disparities in NICU graduate outcomes [23, 24]. Disparities in perinatal mental health outcomes are driven by four major themes: interpersonal, environmental or community, healthcare clinician, and institutional factors. Close consideration of the interplay of these factors and a deeper understanding of strategies to overcome these barriers are critical and deserve further investigation [23, 24].

Current state and challenges

The implementation of FCDC frameworks, including essential, evidence-based practices, such as skin-to-skin care and human milk feeding, has improved integration of families in their infant’s care during hospitalization with positive impacts for infants as well as parental well-being [13, 25,26,27,28]. Continuing FCDC after NICU discharge is especially challenging because our current healthcare system is fragmented rather than family-centered. The focus in pediatric settings generally shifts to the child [12, 29], while care for parents is largely siloed within adult settings. Thus, while the National Perinatal Association (NPA) recently called for NICU families to be “empowered and prepared” for homegoing [14] a minority of families feel their needs are met. A recent study found that 56% of NICU families needed information, support, and/or close follow-up in the days following discharge. Among these families, 21% of families had mental health concerns after discharge [30]. Further, even families who may have been well-adjusted during the NICU hospitalization are at risk for experiencing acute psychosocial distress during or after their transition home. Effective transitions of supportive interventions from inpatient to outpatient settings for NICU families should evolve to support the well-being of the entire family unit [14, 30].

Prior to discharge, recommended best practices include assessment by an interdisciplinary care team, in collaboration with families, to determine their medical and psychosocial readiness for the transition [27]. Strategies such as a checklist or a survey can be used to increase parental confidence [31, 32]. As parents are assessed for mental health symptoms in the NICU using validated screening tools, these results and follow-up recommendations should be incorporated into discharge planning [17, 32]. Team members who are assessing psychosocial readiness can communicate plans with parent permission through the provider who will be signing out to the child’s primary care provider or, where feasible, via warm hand offs to social workers or other similar psychosocial support providers within the child’s primary care clinic. As an alternative, communication could occur directly through a hospital’s electronic medical record system to ensure that both the primary care and specialized NICU follow-up providers are aware of a family’s psychosocial support planning, while protecting family privacy. Documentation practices will need to be adapted based upon hospital practices and state law in addition to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Many NICUs have systems in place for referrals to NICU graduate, or NICU follow-up, programs. These programs offer an opportunity for continuity of psychosocial care, yet there are barriers to realizing this potential. Currently, the primary focus of NICU follow-up clinics is often identification of infant neurodevelopmental impairment and facilitation of early intervention. While some follow-up programs incorporate specialized services to provide continuity of parent psychosocial support in the outpatient setting, this is not yet a universal, established standard of care [33]. In addition, many such clinics and medical homes that provide comprehensive care may have difficulty finding funding to continue their programs [34]. Presently, no guidelines exist to inform a standardized process for referrals of eligible parents to mental health services during follow-up visits after NICU discharge.

Universal mental health screening is a key component of ensuring parent well-being through the transition home. The role of primary care pediatricians in facilitating screening for maternal postpartum depression through infancy is well established. To promote both optimal infant outcomes and family well-being, the AAP recommends that pediatricians screen for maternal postpartum depression during 1-, 2-, 4-, and 6-month well-child visits and consider screening partners at 6 months [35, 36]. However, the current AAP guidelines are largely limited to depression screening for mothers. They do not address the emerging evidence that all parents who are impacted by the NICU, regardless of gender, gestational status, or severity of their infant’s illness, are at risk for heightened psychosocial distress that includes symptoms beyond depression, such as anxiety and trauma symptoms, and may persist beyond these recommended screening intervals. Inclusive, longitudinal perinatal mental health screening is therefore essential for families of infants discharged from the NICU [2, 15, 19, 37,38,39,40].

Practice recommendations

In line with the principles of FCDC, psychosocial and mental health support are recommended for all parents during their NICU hospitalization [1]. Given the downstream effects of stress related to a NICU hospitalization, we argue that structured family mental health support should continue after transition to home, a time of potentially increased stress and vulnerability of the family unit [17, 41, 42]. In this section, we discuss guiding principles in keeping with NPA recommendations for psychosocial program standards surrounding NICU discharge. We utilize these principles as the basis for our practice recommendations for follow-up care, which we suggest as follows [1, 17, 32]:

-

1.

Ensure individualized, family-centered, and culturally competent continuity of psychosocial support for families through effective transitions of care to outpatient medical teams and community resources.

-

2.

Offer comprehensive psychosocial support informed by universal mental health screening, with input from an interdisciplinary team and ongoing monitoring using validated tools after discharge.

-

3.

Prioritize effective communication, education, and trust-building by embedding the family within the interdisciplinary team during hospitalization and after discharge.

We support and reinforce calls for inclusion of family psychosocial assessments during NICU follow-up visits as an integral application of FCDC in the longitudinal care of families impacted by the NICU [38]. Parent mental health screening in follow-up clinics will augment the multilayered screening process already performed through the parents’ primary care providers and the infant’s primary pediatrician. Further, it is important to note that many parents do not have primary care providers [43], making it even more important that parent mental health screening occurs during pediatric visits.

Since parent mental health screening is not routinely a part of NICU follow-up care, it deserves further standardization. The process of mental health screening for parents of infants affected by the NICU ideally begins during pregnancy and continues in the NICU. It was established as an AAP neonatal standard of care in 2023 [44]. Mental health professionals have recommended that screening is performed using standardized, validated instruments [38]. Screening studies have found that factors such as parents’ subjective experience in the NICU, or perceived threat, is a more reliable predictor of mental health difficulties than the infant’s objective clinical status [15, 39]. Thus, it is critical that screening is implemented equitably and universally, and that all families can access individualized support that is tailored to their goals, values, and experiences.

In addition, longitudinal screening is essential. Families may fall into different risk categories during the NICU stay and after transitions because individual responses to the NICU stressors emerge along varying trajectories [1, 45]. Subsequently, repeating parent mental health screening before anticipated NICU discharge can inform a discharge assessment as well as FCDC post-discharge [38, 39, 46]. Anne Kazak’s Pediatric Psychosocial Preventative Health Model (PPPHM) categorizes families as (1) distressed but resilient, requiring universal screening and general support and resources, (2) in acute distress or with risk factors, requiring interventions and services specific to symptoms as well as monitoring, or (3) with persistent and/or escalating distress or high-risk factors, requiring consultation with a mental health specialist [47]. These categories can be determined through mental health screening in addition to clinical assessments by the psychosocial team in the NICU and used to identify the appropriate level of support for each family impacted by the NICU [47, 48].

Per AAP recommendations, high-risk hospitalized infants should have neurodevelopmental follow-up identified and all indicated subspecialty follow-up referrals made prior to discharge [49, 50]. In addition to infant medical risk, mental health screening at discharge can be used in combination with a psychosocial team’s clinical assessments to identify families that may benefit from NICU follow-up clinic. However, it is important that follow-up clinics are adequately equipped to meet the psychosocial needs of families [33, 35, 36]. To achieve this, we propose that NICU graduate programs include specialized staff and are structured as the standard of care to optimally support families’ psychosocial needs.

Similar to the billing strategies that have been recommended by AAP for perinatal mental health screening that occurs at pediatric well-child visits [35], appropriate billing codes can be incorporated when screening is performed at NICU follow up visits. Reimbursement, where applicable, may assist with financial sustainability of such efforts. Billing codes may vary by payor and state, thus billing guidelines will likely need to be created at an institutional or state level. Care is needed to ensure that the cost of psychosocial services is not translated to families, as this may add additional burden and create barriers to follow-up visits.

Potential strategies to improve long-term mental health outcomes

Several comprehensive program models and individual components of FCDC have shown success; however, evidence evaluating implementation of FCDC in intensive care units has been categorized as weak per GRADE methodology due to a paucity of rigorous supporting research [29]. Evidence for inpatient interventions incorporating developmentally supportive care initiatives like kangaroo care and randomized controlled trials evaluating programs such as Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment (COPE) and Family Nurture Intervention (FNI) demonstrate benefits that persist after discharge from the NICU [13, 51, 52]. Moreover, interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and counseling are evidence-based interventions for perinatal depression, anxiety, and PTSD [53], and manualized CBT in the NICU has demonstrated improvement in depression, anxiety, and trauma symptoms that persist through 6 months [54]. However, there is little evidence examining outpatient care models after NICU discharge, highlighting an ongoing need for further research. Where evidence is lacking, recommendations have been made based on published expert opinions.

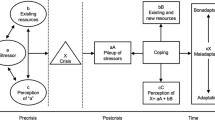

We propose a conceptual framework that highlights how family factors and structural inequities impact NICU family mental health outcomes (Fig. 1). We suggest incorporating targeted strategies to address modifiable risk factors based on a family’s identified level of psychosocial needs at discharge (Table 1).

Demonstrates factors that may influence long-term mental health outcomes of families impacted by neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Factors are categorized by level of support, including the family, NICU, outpatient healthcare system, and community. FCDC family-centered developmental care, PCP primary care provider, WIC Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Considerations for the future

There are opportunities at the local, state, and national levels to advocate for improved support for families impacted by the NICU in their long-term psychosocial needs [48] (Table 2). At a policy level, prime considerations include mandating paid family leave at a federal level and extending Medicaid programs at the state level to ensure coverage for parent health for a minimum of one year postpartum [55,56,57]. Additionally, increasing research funding for NICU family mental health is crucial for developing interventions that better address the unique challenges faced by these families and improve long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes for NICU graduates.

As the care of high-risk neonates continues to advance, it is imperative that we prioritize effective transitions of these infants and their families out of the NICU environment. To achieve this goal, we strongly reinforce calls to accept responsibility for the ongoing environmental factors and social determinants of health that impact the trajectories of the infants and families for whom we care [58]. We propose broadening the scope of NICU post-discharge follow-up care to systematically incorporate strategies to support the well-being of the entire family unit, including hiring staff with training and expertise in adult mental health. Further, integration of medical-legal partnerships in these interdisciplinary programs will be key to addressing issues of safe and secure housing as well as access to public programs, as lower levels of social support correlate with mental health symptoms [59]. By committing to these initiatives, we can ensure that families impacted by a NICU hospitalization receive the comprehensive, holistic care they deserve, and that their transition home is one of support, empowerment, and success long-term.

References

Hynan MT, Hall SL. Psychosocial program standards for NICU parents. J Perinatol. 2015;35:S1–S4.

Pace CC, Spittle AJ, Molesworth CM-L, Lee KJ, Northam EA, Cheong JLY, et al. Evolution of depression and anxiety symptoms in parents of very preterm infants during the newborn period. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:863.

Treyvaud K, Lee KJ, Doyle LW, Anderson PJ. Very preterm birth influences parental mental health and family outcomes seven years after birth. J Pediatr. 2014;164:515–21.

Roque ATF, Lasiuk GC, Radünz V, Hegadoren K. Scoping review of the mental health of parents of infants in the NICU. J Obstet, Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2017;46:576–87.

Shaw RJ, Givrad S, Poe C, Loi EC, Hoge MK, Scala M. Neurodevelopmental, mental health, and parenting issues in preterm infants. Children. 2023;10:1565.

Schecter R, Pham T, Hua A, Spinazzola R, Sonnenklar J, Li D, et al. Prevalence and longevity of PTSD symptoms among parents of NICU infants analyzed across gestational age categories. Clin Pediatr (Philos). 2020;59:163–9.

Shaw RJ, Lilo EA, Storfer-Isser A, Ball MB, Proud MS, Vierhaus NS, et al. Screening for symptoms of postpartum traumatic stress in a sample of mothers with preterm infants. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2014;35:198–207.

Broom M, Cochrane T, Cruickshank D, Carlisle H. Parental perceptions on the impact of visiting restrictions during COVID-19 in a tertiary neonatal intensive care unit. J Paediatr Child Health. 2022;58:1747–52.

Liu CH, Koire A, Erdei C, Mittal L. Unexpected changes in birth experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for maternal mental health. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021;306:687–97.

Erdei C, Liu CH, Machie M, Church PT, Heyne R Parent mental health and neurodevelopmental outcomes of children hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit. Early Hum Dev. 2021; 154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105278.

Minkovitz CS, Strobino D, Scharfstein D, Hou W, Miller T, Mistry KB, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms and children’s receipt of health care in the first 3 years of life. Pediatrics. 2005;115:306–14.

Gooding JS, Cooper LG, Blaine AI, Franck LS, Howse JL, Berns SD. Family support and family-centered care in the neonatal intensive care unit: origins, advances, impact. Semin Perinatol. 2011;35:20–28.

Craig JW, Glick C, Phillips R, Hall SL, Smith J, Browne J. Recommendations for involving the family in developmental care of the NICU baby. J Perinatol. 2015;35:S5–S8.

Padratzik HC, Love K. NICU discharge preparation and transition planning: foreword. J Perinatol. 2022;42:3–4.

Lefkowitz DS, Baxt C, Evans JR. Prevalence and correlates of posttraumatic stress and postpartum depression in parents of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17:230–7.

Garfield CF, Lee Y, Kim HN. Paternal and maternal concerns for their very low-birth-weight infants transitioning from the NICU to home. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2014;28:305–12.

Purdy IB, Craig JW, Zeanah P. NICU discharge planning and beyond: recommendations for parent psychosocial support. J Perinatol. 2015;35:S24–S28.

Gong J, Fellmeth G, Quigley MA, Gale C, Stein A, Alderdice F, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for postnatal mental health problems in mothers of infants admitted to neonatal care: analysis of two population-based surveys in England. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23:370.

Horwitz SM, Storfer-Isser A, Kerker BD, Lilo E, Leibovitz A, St. John N, et al. A model for the development of mothers’ perceived vulnerability of preterm infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2015;36:371–80.

Estroff DB, Yando R, Burke K, Synder D. Perceptions of preschoolers’ vulnerability by mothers who had delivered preterm. J Pediatr Psychol. 1994;19:709–21.

Green SL. The pediatrician and the maternal-infant relationship. Psychosomatics. 1964;5:75–81.

Hoge MK DLHSSDSR. Vulnerable Child Syndrome. In: Shaw RJ, Horwitz S (eds). Treatment of Psychological Distress in Parents of Premature Infants: PTSD in the NICU. 2021, pp 277–308.

Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389:1453–63.

Beck AF, Edwards EM, Horbar JD, Howell EA, McCormick MC, Pursley DM. The color of health: how racism, segregation, and inequality affect the health and well-being of preterm infants and their families. Pediatr Res. 2020;87:227–34.

Eidelman AI, Schanler RJ, Johnston M, Landers S, Noble L, Szucs K, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e827–e841.

Purdy IB, Singh N, Le C, Bell C, Whiteside C. Collins M. Biophysiologic and social stress relationships with breast milk feeding pre- and post-discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit. J Obstet, Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012;41:347–57.

Hall SL, Hynan MT, Phillips R, Lassen S, Craig JW, Goyer E, et al. The neonatal intensive parenting unit: an introduction. J Perinatol. 2017;37:1259–64.

Axelin A, Feeley N, Campbell-Yeo M, Silnes Tandberg B, Szczapa T, Wielenga J, et al. Symptoms of depression in parents after discharge from NICU associated with family-centred care. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78:1676–87.

Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, et al. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:103–28.

Lagatta J, Malnory M, Fischer E, Davis M, Radke-Connell P, Weber C, et al. Implementation of a pilot electronic parent support tool in and after neonatal intensive care unit discharge. J Perinatol. 2022;42:1110–7.

Gupta M, Pursley DM, Smith VC. Preparing for discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2019; 143. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2915.

Smith VC, Love K, Goyer E. NICU discharge preparation and transition planning: guidelines and recommendations. J Perinatol. 2022;42:7–21.

Litt JS, Campbell DE. High-risk infant follow-up after NICU discharge. Clin Perinatol. 2023;50:225–38.

Van Cleave J, Boudreau AA, McAllister J, Cooley WC, Maxwell A, Kuhlthau K. Care coordination over time in medical homes for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2015;135:1018–26.

Earls MF, Yogman MW, Mattson G, Rafferty J, Baum R, Gambon T et al. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2019; 143. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3259.

Walsh TB, Davis RN, Garfield C. A call to action: screening fathers for perinatal depression. Pediatrics. 2020; 145. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1193.

Hynan MT, Mounts KO, Vanderbilt DL. Screening parents of high-risk infants for emotional distress: rationale and recommendations. J Perinatol. 2013;33:748–53.

Hynan MT, Steinberg Z, Baker L, Cicco R, Geller PA, Lassen S, et al. Recommendations for mental health professionals in the NICU. J Perinatol. 2015;35:S14–S18.

Moreyra A, Dowtin LL, Ocampo M, Perez E, Borkovi TC, Wharton E, et al. Implementing a standardized screening protocol for parental depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Early Hum Dev. 2021;154:105279.

Soghier LM, Kritikos KI, Carty CL, Glass P, Tuchman LK, Streisand R, et al. Parental Depression Symptoms at Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Discharge and Associated Risk Factors. J Pediatr. 2020;227:163–.e1.

Shah AN, Jerardi KE, Auger KA, Beck AF. Can hospitalization precipitate toxic stress? Pediatrics. 2016; 137. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0204.

Pynoos RS, Steinberg AM, Layne CM, Liang L-J, Vivrette RL, Briggs EC, et al. Modeling constellations of trauma exposure in the national child traumatic stress network core data set. Psychol Trauma. 2014;6:S9–S17.

Wainwright S, Caskey R, Rodriguez A, Holicky A, Wagner-Schuman M, Glassgow AE. Screening fathers for postpartum depression in a maternal-child health clinic: a program evaluation in a midwest urban academic medical center. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23:675.

Stark AR, Pursley DM, Papile L-A, Eichenwald EC, Hankins CT, Buck RK et al. Standards for levels of neonatal care: II, III, and IV. Pediatrics. 2023; 151. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2023-061957.

Kim WJ, Lee E, Kim KR, Namkoong K, Park ES, Rha D. Progress of PTSD symptoms following birth: a prospective study in mothers of high-risk infants. J Perinatol. 2015;35:575–9.

Hoge M. Reduction of Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) Parental Perceptions of Child Vulnerability and Risk of Vulnerable Child Syndrome Utilizing Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Randomized Controlled Trial. Honolulu, 2025.

Kazak AE, Schneider S, Didonato S, Pai ALH. Family psychosocial risk screening guided by the Pediatric Psychosocial Preventative Health Model (PPPHM) using the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT). Acta Oncol (Madr). 2015;54:574–80.

Ashley D Osborne DYBTWKHTBEMCPMSDM-WRB; HPSL. Understanding and Addressing Mental Health Challenges of Families Admitted to the NICU.

Follow-up Care of High-Risk Infants. Pediatrics. 2004; 114: 1377-97.

Hospital Discharge of the High-Risk Neonate. Pediatrics. 2008; 122: 1119-26.

Melnyk BM, Feinstein NF, Alpert-Gillis L, Fairbanks E, Crean HF, Sinkin RA, et al. Reducing premature infants’ length of stay and improving parents’ mental health outcomes with the creating opportunities for parent empowerment (cope) neonatal intensive care unit program: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1414–e1427.

Welch MG, Hofer MA, Brunelli SA, Stark RI, Andrews HF, Austin J, et al. Family nurture intervention (FNI): methods and treatment protocol of a randomized controlled trial in the NICU. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:14.

Nillni YI, Mehralizade A, Mayer L, Milanovic S. Treatment of depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders during the perinatal period: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;66:136–48.

Shaw RJ, St John N, Lilo E, Jo B, Benitz W, Stevenson DK, et al. Prevention of traumatic stress in mothers of preterms: 6-month outcomes. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e481–e488.

Steenland MW, Trivedi AN. Association of medicaid expansion with postpartum depression treatment in Arkansas. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4:e225603.

Raphael JL, Patel M. Extending public insurance postpartum coverage: implications for maternal and child health. Pediatr Res. 2022;91:725–6.

Weber A, Harrison TM, Steward D, Ludington-Hoe S. Paid family leave to enhance the health outcomes of preterm infants. Policy Polit Nurs Pr. 2018;19:11–28.

Maitre NL, Duncan AF. The future of high-risk infant follow-up. Clin Perinatol. 2023;50:281–3.

VON for Health Equity. Potentially Better Practices for Follow Through. https://public.vtoxford.org/health-equity/potentially-better-practices-for-follow-through/ 2022.

Smith VC, Hwang SS, Dukhovny D, Young S, Pursley DM. Neonatal intensive care unit discharge preparation, family readiness and infant outcomes: connecting the dots. J Perinatol. 2013;33:415–21.

Melnyk BM, Crean HF, Feinstein NF, Fairbanks E. Maternal anxiety and depression after a premature infant’s discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit. Nurs Res. 2008;57:383–94.

Johnson AN. Engaging fathers in the NICU. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2008;22:302–6.

Arnold J, Diaz MCG. Simulation training for primary caregivers in the neonatal intensive care unit. Semin Perinatol. 2016;40:466–72.

Kynø NM, Ravn IH, Lindemann R, Smeby NA, Torgersen AM, Gundersen T. Parents of preterm-born children; sources of stress and worry and experiences with an early intervention programme – a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2013;12:28.

Placencia FX, McCullough LB. Biopsychosocial risks of parental care for high-risk neonates: implications for evidence-based parental counseling. J Perinatol. 2012;32:381–6.

Bowles JD, Jnah AJ, Newberry DM, Hubbard CA, Roberston T. Infants with technology dependence. Adv Neonatal Care. 2016;16:424–9.

Larsson C, Wågström U, Normann E, Thernström Blomqvist Y. Parents experiences of discharge readiness from a Swedish neonatal intensive care unit. Nurs Open. 2017;4:90–95.

Pilon B. Family reflections: hope for HIE. Pediatr Res. 2019;86:672–3.

Hall SL, Ryan DJ, Beatty J, Grubbs L. Recommendations for peer-to-peer support for NICU parents. J Perinatol. 2015;35:S9–S13.

Ahn YM, Kim MR. The effects of a home-visiting discharge education on maternal self-esteem, maternal attachment, postpartum depression and family function in the mothers of NICU infants. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2004;34:1468.

Vohr B, McGowan E, Keszler L, Alksninis B, O’Donnell M, Hawes K, et al. Impact of a transition home program on rehospitalization rates of preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2017;181:86–92.e1.

Griffith T, Singh A, Naber M, Hummel P, Bartholomew C, Amin S, et al. Scoping review of interventions to support families with preterm infants post-NICU discharge. J Pediatr Nurs. 2022;67:e135–e149.

Robinson C, Gund A, Sjöqvist B, Bry K. Using telemedicine in the care of newborn infants after discharge from a neonatal intensive care unit reduced the need of hospital visits. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105:902–9.

Garfield CF, Kerrigan E, Christie R, Jackson KL, Lee YS. A mobile health intervention to support parenting self-efficacy in the neonatal intensive care unit from admission to home. J Pediatr. 2022;244:92–100.

Nayak BS, Lewis LE, Margaret B, Bhat YR, D’Almeida J, Phagdol T. Randomized controlled trial on effectiveness of mHealth (mobile/smartphone) based Preterm Home Care Program on developmental outcomes of preterms: Study protocol. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75:452–60.

Globus O, Leibovitch L, Maayan-Metzger A, Schushan-Eisen I, Morag I, Mazkereth R, et al. The use of short message services (SMS) to provide medical updating to parents in the NICU. J Perinatol. 2016;36:739–43.

Garne Holm K, Brødsgaard A, Zachariassen G, Smith AC, Clemensen J. Parent perspectives of neonatal tele-homecare: a qualitative study. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25:221–9.

VON for Health Equity. https://public.vtoxford.org/health-equity/potentially-better-practices-for-follow-through/. 2023.

Fuller MG, Vaucher YE, Bann CM, Das A, Vohr BR. Lack of social support as measured by the Family Resource Scale screening tool is associated with early adverse cognitive outcome in extremely low birth weight children. J Perinatol. 2019;39:1546–54.

Williams DR, Jackson PB. Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Aff. 2005;24:325–34.

Bledsoe SE, Grote NK. Treating depression during pregnancy and the postpartum: a preliminary meta-analysis. Res Soc Work Pr. 2006;16:109–20.

Brandon AR, Ceccotti N, Hynan LS, Shivakumar G, Johnson N, Jarrett RB. Proof of concept: partner-assisted interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2012;15:469–80.

Grote NK, Swartz HA, Zuckoff A. Enhancing interpersonal psychotherapy for mothers and expectant mothers on low incomes: adaptations and additions. J Contemp Psychother. 2008;38:23–33.

Shaw RJ, Moreyra A, Simon S, Wharton E, Dowtin LL, Armer E, et al. Group trauma focused cognitive behavior therapy for parents of premature infants compared to individual therapy intervention. Early Hum Dev. 2023;181:105773.

Simon S, Moreyra A, Wharton E, Dowtin LL, Borkovi TC, Armer E, et al. Prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder in mothers of preterm infants using trauma-focused group therapy: Manual development and evaluation. Early Hum Dev. 2021;154:105282.

Thomas R, Abell B, Webb HJ, Avdagic E, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Parent-child interaction therapy: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017; 140. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0352.

Funding

None. This work product is a result of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Trainees and Early Career Neonatologists (TECaN) National Advocacy Campaign, Carousel Care (www.CarouselCare.org). Funding from the AAP was made available for continuing medical education (CME) credits for its webinar contents, which is reflected in this article. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS, RD, SV, MH, ZH, CC, KR, KM, CE contributed to the initial concept. SS, RD, SV, MH, ZH, CC, KR performed the literature review and drafted the initial manuscript. SV drafted Table 1 and Fig. 1. KM, CE, CL, MH provided expertise and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. SS, RD provided critical revisions to the final draft. All authors approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Swenson, S.A., Desai, R.K., Velagala, S. et al. From NICU to home: meeting the mental health needs of families after discharge. J Perinatol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-025-02503-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-025-02503-x