Abstract

Whether there is really a distinct accelerated phase (AP) at diagnosis in chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) in the context of tyrosine kinase-inhibitor (TKI)-therapy is controversial. We studied 2122 consecutive subjects in chronic phase (CP, n = 1837) or AP (n = 285) at diagnosis classified according to the 2020 European LeukemiaNet (ELN) classification. AP subjects with increased basophils only had similar transformation-free survival (TFS) and survival compared with CP subjects classified as ELTS intermediate-risk. Those with increased blasts only had worse TFS but similar survival compared with CP subjects classified as ELTS high-risk. AP subjects with decreased platelets only had similar TFS but worse survival compared with subjects classified as ELTS high-risk. Proportions of CP and AP subjects meeting the 2020 ELN TKI-response milestones were similar. However, worse TFS at 3-month and survival at 6- or 12-month were only in AP subjects failing to meet ELN milestones. Findings were similar using the 2022 International Consensus Classification (ICC) criteria for AP replacing decreased platelets with additional cytogenetic abnormalities. Our data support the 2022 WHO classification of CML eliminating AP. We suggest adding a very high-risk cohort to the ELTS score including people with increased blasts or decreased platelets and dividing CML into 2 phases at diagnosis: CP and acute or blast phases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is considerable recent controversy whether CML is a bi- or tri-phasic disease; chronic (CP) and blast phase (BP) with or without an intermediate accelerated phase (AP) [1,2,3]. From a biological perspective chronic phase CML is best considered a leukaemia but not a cancer lacking unregulated proliferation. CP cells differentiate normally and respond to normal physiological stimuli. CP bone marrow CD34-positive cells do not form colonies granulocyte/macrophage colonies in vitro without appropriate stimuli (like normal CD34-positive cells and they cannot easily reconstitute immune compromised mice). In untreated CP CML the concentration of blood granulocytes reaches an apogee without further increase [2,3,4,5]. It is estimated the abnormal granulocyte mass can be explained by as few as 2-4 extra late cell divisions. In gene expression profiling (GEP) the pattern of expression suggests 2 phases rather than 3 phases [6].

Clinically, CML was initially divided into 2 phases: CP versus terminal, blast or not chronic phases [7]. The suggestion of an AP was based on identifying co-variates associated with an increased risk of transforming to BP. These co-variates differ between different AP classifications [3, 8, 9]. Moreover, in the context of tyrosine kinase-inhibitor (TKI)-therapy this increased transformation risk is modest. Also, people classified as presenting in AP receive the same TKI-therapy as those presenting in CP. Based on these considerations AP was removed from the World Health Organization (WHO) 2022 CML classification [2]. However the 2020 European Leukaemia Net (ELN) recommendations, 2022 International Consensus Classification (ICC) and 2024 National Comprehensive Cancer Guidelines retain AP phase CML [3, 5].

We interrogated data from 2122 subjects with CML presenting in CP (n = 1837) or AP (n = 285) using definitions in the ELN 2020 criteria and 2053 subjects presenting in CP (n = 1748) or AP (n = 305) using the 2022 ICC criteria. We found most subjects classified as AP had outcomes like those of subjects in CP defined as intermediate- or high-risk in the European Treatment and Outcome Study (EUTOS) Long-Term Survival (ELTS) risk score. About 25 percent, those with increased blasts only or with decreased platelets had worse transformation-free survival (TFS) or survival but not both. However, these worse outcomes were only in subjects failing to meet the 2020 ELN TKI-therapy-response criteria. Proportions of CP and AP subjects meeting the 2020 ELN TKI-response milestones were similar. These data indicate co-variates used to identify AP do not identify a distinct phase but are predictors of the likelihood of response to TKI-therapy. Our conclusions support the 2022 WHO CML classification removing AP. We conclude CML should be divided into CP and terminal, acute or not chronic phases without an intermediate AP.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

We interrogated data from consecutive subjects ≥18 years with CML initially presenting with AP and CP at Peking University People’s Hospital from January, 2006 to June, 2023. Criteria of ELN 2020 for subjects initially presenting with AP included ≥1 of the followings: 1) blood or bone marrow blasts 15–29%; 2) blood basophils ≥20%; and 3) platelet concentration <100 × 10E + 9/L unrelated to therapy [5]. The ICC 2022 AP criteria include ≥1 of the followings: 1) bone marrow or blood blasts 10–19%; 2) blood basophils ≥20%; and 3) presence of additional clonal cytogenetic abnormalities in Ph-chromosome-positive cells (ACA) including second Ph-chromosome, trisomy 8, isochromosome 17q, trisomy 19, complex karyotype or abnormalities of 3q26.2 [3]. Demographic and clinical co-variates including age, sex, complete blood count (CBC) parameters, spleen size below costal margin, comorbidity(ies), ACA in Ph-positive cells including a 2nd Ph, trisomy 8, isochromosome 17q, trisomy 19, complex cytogenetics and/or abnormalities of 3q26.2. Outcomes were abstracted from the medical record. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University People’s Hospital and subjects gave written informed consent consistent with precepts of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Treatment, monitoring and evaluation

Treatment, monitoring and evaluation followed the ELN recommendations [5, 10, 11]. For persons in CP the ELTS score at diagnosis was calculated as described [12]. Bone marrow cytogenetic analyses used G-banding. Blood samples were used to analyse BCR::ABL1 transcript type at diagnosis. During TKI-therapy, BCR::ABL1 transcript levels were analysed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) with an ABL1 control and converted to international scales (BCR::ABL1IS) using our laboratory-specific conversion factor of 0.65 validated at the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science International Reference Laboratory when the value (IS) was < 10% [13]. Screening for BCR::ABL1 mutation was done in subjects with a sub-optimal, warning or failure responses according to the ELN recommendations [5, 10, 11]. The last follow-up was 30, September, 2023.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize co-variates. Categorical variables were reported as percentages and counts. Continuous variables were reported as medians and ranges or interquartile range (IQR). Pearson Chi-square test was used to analyse categorical variables. Student’s t (normal distribution) or Mann–Whitney U (non-normal distribution) tests were used to analyse continuous variables. Transformation was defined as blood or bone marrow blasts ≥30% (ELN criteria) or ≥20% (ICC criteria) [3, 5]. Transformation-free survival (TFS) was calculated from TKI-therapy start to the date of transformation, death or censored at a transplant or last follow-up. Survival was calculated from TKI-therapy start to death from any cause or censored at a transplant or last follow-up. Probabilities of TFS and survival were calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by log-rank test. Subjects were censored at a transplantation, death or last follow-up.

Uni- and multi-variable analyses were conducted to explore the co-variates associated with therapy responses and outcomes. Potentially prognostic co-variates included age, sex, WBC counts, haemoglobin concentration (HGB), disease phase, ACA in Ph-positive cells and co-morbidity(ies). Co-variates correlated at P < 0.20 were included in multi-variable analyses, and variance inflation factors (VIFs) was estimated to check for multi-collinearity amongst co-variates relevant to outcomes and responses to TKIs. 2-sided P < 0.05 was considered significant. SPSS 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and R version 4.0.2 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) were used for analysis and graphing.

Results

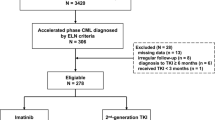

Subjects diagnosed by the ELN 2022 recommendations

Data from 2296 consecutive CP (n = 1991) and AP (n = 305) persons were interrogated (Fig. 1). 23 subjects were exclude because the age at diagnosis was <18 years old, 22 subjects with an interval from diagnosis to start of TKI therapy ≥6 months, 26 with a BCR::ABL transcript other than e14a2 or e13a2, 3 with the duration of TKI-therapy <3 months and 100 with irregular response monitoring and/or loss to follow-up. 2122 subjects (CP; n = 1837; AP; n = 285) were evaluable for analyses, 6 subjects with incomplete haematological data at diagnosis, and 13 with no cytogenetics data.

1133 (62%) CP subjects were male. Median age was 40 years (Interquartile Range [IQR], 30–52 years) (Table 1). 1209 (66%), 453 (25%) and 175 (10%) were classified as ELTS low-, intermediate- and high-risk. With a median follow-up of 53 months (IQR, 27–84 months), 101 (6%) subjects transformed to BP and 50 (3%) died. 7-year probabilities of TFS and survival were 91% (89, 92%) and 95% (93, 96%). At last follow-up 392 subjects (27%) receiving initial imatinib-therapy switched to 2nd-generation TKI (2G-TKI) (n = 333; 85%), 3rd-generation TKI (3G-TKI) (n = 53; 14%) or chemotherapy (n = 6; 2%). 99 subjects (26%) receiving initial 2G-TKI therapy switched to imatinib (n = 36; 36%), a 2G-TKI (n = 42; 43%), a 3G-TKI (n = 18; 18%) or chemotherapy (n = 3; 3%) because of therapy failure (n = 64, 65%), adverse events (n = 9; 9%) or subject preference (n = 26; 26%).

181 subjects (64%) classified as AP at diagnosis were male. Median age was 42 years (IQR, 31–54 years). 204 (71%), 37 (13%), 31 (11%) and 13 (5%) subjects were classified as AP based on increased basophils only, increased blasts only, decreased platelets only and ≥2 features (Table 1). With a median follow-up of 49 months (IQR, 25–96 months), 42 (15%) subjects transformed to BP and 25 (9%) died. 7-year probabilities of TFS and survival were 84% (79, 89%) and 91% (86, 95%). At last follow-up, 68 subjects (36%) receiving initial imatinib-therapy switched to a 2G-TKI (n = 63, 93%), a 3G-TKI (n = 3, 4%) or chemotherapy (n = 2, 3%). 33 subjects (34%) receiving initial 2G-TKI therapy switched to imatinib (n = 3, 9%), a 2G-TKI (n = 22, 67%), a 3G-TKI (n = 7, 21%) or chemotherapy (n = 1, 3%) because of therapy failure (n = 26, 79%), adverse events (n = 4, 12%) or subject preference (n = 3, 9%).

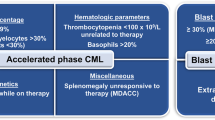

Comparison of outcomes

Comparisons by AP subjects at diagnosis by defining criteria and CP subjects by ELTS risk cohort are displayed in Fig. 2. (There were too few AP subjects defined by ≥ 2 criteria for this analysis). We used uni- and multi-variable analyses to explore co-variates associated with TFS and survival (Supplementary Table 1 and Table 2). There were no multi-collinearity interactions (VIFs = 1.0 ~ 1.8) between potential predictive co-variates including disease phase, sex, age, haemoglobin, WBC and platelet concentrations, ACA in Ph-chromosome-positive cells or co-morbidity(ies). In multi-variable analyses the ELTS low-, intermediate- and high-risk cohorts were used as the reference cohort. AP subjects with increased basophils only had comparable TFS and survival compared with CP subjects in the ELTS intermediate-risk cohort. AP subjects with increased blasts only had worse TFS (HR = 2.2 [1.1, 4.5]; P = 0.03) but similar survival (HR = 1.5 [0.5, 4.6]; P = 0.50) compared with CP subjects in the ELTS high-risk cohort. AP subjects with decreased platelets only had similar TFS (HR = 1.9 [0.9, 4.2]; P = 0.10) but worse survival (HR = 2.7 [1.0, 7.3]; P = 0.04) compared with ELTS high-risk cohort.

A Comparison of TFS between CP and AP; B comparison of survival between CP and AP; C comparison of TFS between CP subgroups (separated by ELTS risk category) and AP subgroups (separated by features presented in AP); D comparison of survival between CP subgroups (separated by ELTS risk category) and AP subgroups (separated by features presented in AP). CP chronic phase, AP accelerated phase, ELN European LeukemiaNet, TFS transformation-free survival, ELTS European Treatment and Outcome Study (EUTOS) Long-Term Survival.).

We did sensitivity analyses in subjects receiving initial imatinib therapy (n = 1638) or initial 2G-TKI therapy (n = 471) using the ELN criteria (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Subjects in the initial imatinib cohort AP with increased basophils only had similar outcomes compared with CP subjects in the ELTS intermediate-risk cohort. AP subjects with increased blasts only or decreased platelets only had similar outcomes compared with CP subjects in ELTS high-risk cohort. In the 2G-TKI cohort AP subjects with increased basophils only had similar outcomes compared with CP subjects in the ELTS low- and intermediate-risk cohorts. Subjects with increased blasts only had worse TFS HR = 3.4 [1.0, 11.3]; P = 0.05) but similar survival (HR = 0.0 [0.0, ∞]; P = 1.00; there was no death in this cohort) compared with CP subjects in ELTS high-risk cohort. AP subjects with decreased platelets only had worse TFS (HR = 4.6 [1.4, 15.3]; P = 0.01) and worse survival (HR = 9.0 [1.9, 41.5]; P = 0.01) compared with CP subjects in ELTS high-risk cohort. The model using the 3 AP and 3 CP categories is displayed in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5.

We analysed interactions in the Cox regression model including disease phase, and WBC and haemoglobin concentrations (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). There was an interaction between intermediate-risk CP and WBC concentration in the multi-variable Cox regression analysis for TFS but included the interaction term into the multi-variable model did not significantly improve model fit. We compared the models including and excluding the interaction term using Analysis of Deviance Table. Chi-square statistic for adding the interaction terms for TFS was 6.30 with 5 degrees of freedom corresponding to a P-value of 0.28.

Using revised ELN definitions of CP, AP and blast phase (BP) we found outcomes of revised-AP subjects (with 15-29% blasts and <100 × 10E + 9/L platelets) were similar to BP subjects (Supplementary Fig. 3). However, these subjects received different therapy; 3rd generation TKIs and transplants were more common in TKI-therapy BP cohort.

ELTS risk score predicts outcomes in AP subjects

241 evaluable AP subjects were classified as ELTS low- (n = 74), intermediate- (n = 74) and high-risk (n = 93). The distribution of ELTS risk category in AP subjects classified by increased basophils only, increased blasts only and decreased platelets only are displayed in Fig. 3. 73 subjects (41%) with increased basophils were classified as low-, 61 (34%) as intermediate- and 44 (25%) as ELTS high-risk. 2 subjects with increased blasts only were classified as ELTS intermediate- and 32 as high-risk. 1 subject with decreased platelets only was classified as low-, 11 as intermediate- and 17 as ELTS high-risk. There was significant difference in outcomes between the 3 risk cohorts (P = 0.01 ~ <0.001). ELTS scores of all subjects and correlations with TFS and survival are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 4. When we used the ELTS score in AP subjects we found it correlates with TFS and survival (Supplementary Table 8).

A The distribution of ELTS risk category in AP subjects; B comparisons of TFS between AP subgroups (divided by ELTS risk categories); C comparisons of survival between AP subgroups (divided by ELTS risk categories). ELTS European Treatment and Outcome Study (EUTOS) Long-Term Survival, AP accelerated phase, ELN European LeukemiaNet, TFS transformation-free survival.

Comparison of outcomes by ELN milestones

There was no difference in proportions of subjects meeting optimal, warning and failure at 3, 6 and 12 months according to the ELN response milestones criteria between CP and AP cohorts. However, AP subjects with increased blasts only or decreased platelets only had higher failure rate at 3 months (P = 0.03) and high non-optimal rates at 6 months (P = 0.06). When subjects with increased basophils only were re-classified into CP ELTS risk cohort the remaining AP subjects showed higher rate of meeting warning and/or failure response milestones at 3 (P = 0.01) and 6 (P = 0.08) months (Fig. 4). AP subjects achieving optimal and warning response showed similar outcomes to CP subjects. However, AP subjects with a failure milestone had significantly worse TFS (3-month, P = 0.027; 6-month, P = 0.204; 12-months, P = 0.189) and/or survival (3-month, P = 0.118; 6-month, P = 0.057; 12-months, P = 0.056) than CP subjects (Fig. 5).

A Comparison between CP and AP; B comparison between AP subgroups; C comparison between revised-CP (CP subjects and AP subjects with increased basophils) and revised-AP (AP subjects with increased blasts or decreased platelets). IS international scales, ELN European LeukemiaNet, CP chronic phase, AP accelerated phase.

A Comparison of TFS between CP and AP (separated by response to TKIs) at 3-month; B comparison of survival between CP and AP (separated by response to TKIs) at 3-month; C comparison of TFS between CP and AP (separated by response to TKIs) at 6-month; D comparison of survival between CP and AP (separated by response to TKIs) at 6-month; E comparison of TFS between CP and AP (separated by response to TKIs) at 12-month; F comparison of survival between CP and AP (separated by response to TKIs) at 12-month. CP chronic phase, AP accelerated phase, TKI tyrosine kinase-inhibitor, ELN European LeukemiaNet, TFS transformation-free survival.

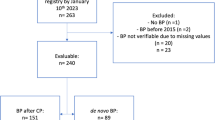

Subjects diagnosed by the ICC 2022 criteria

Data from 2052 consecutive CP (n = 1748) and AP (n = 305) persons were interrogated according to the ICC criteria. The above analyses were repeated in subjects classified as AP using the 2022 ICC criteria. Subject co-variates were shown in the Supplementary Figs. 5–11 and Supplementary Tables 9–12. Supplementary Table 13 showed the categorizations of patients diagnosed CP and AP due to ELN and ICC. In multi-variable analyses AP subjects with increased basophils only had comparable TFS and survival compared with CP subjects in the ELTS intermediate-risk cohort. AP subjects with increased blasts only had similar survival but worse TFS (HR = 2.0 [1.0, 3.7]; P = 0.04) compared with CP subjects in ELTS high-risk cohort. AP subjects with ACA only or ≥2 features had comparable TFS and survival compared with CP subjects in ELTS high-risk cohort.

There were significant differences in the proportion of subjects achieving 2020 ELN response milestones at 3 months but not at 6 months and thereafter between CP and AP subjects. Overall, the outcomes of AP subjects classified by the 2022 ICC 2022 criteria were like those classified by the 2020 ELN criteria.

Discussion

AP CML was previously defined by co-variates correlated with progression from CP to BP before TKIs were widely used to treat CML. With TKI-therapy few people progress from CP. Presentation of CML in AP is also uncommon, only 13 percent in our large consecutive series.

As the WHO expert panel discusses, transformation of CP CML is correlated with a failed response to TKI-therapy, usually from a TKI-resistant ABL1 kinase domain mutation, and/or additional chromosomal abnormalities [14, 15]. Moreover, therapies of AP and CP are similar. For these reasons AP was dropped from the 2022 WHO CML classification. This decision is supported by data of GEP indicating only 2 phases of CML, CP and BP. Others disagree [5].

We found AP subjects at presentation with increased basophils only had similar TFS and survival compared with CP subjects classified as ELTS intermediate-risk. Those with increased blasts only had worse TFS but similar survival compared with CP subjects classified as ELTS high-risk. AP subjects with decreased platelets only had similar TFS but worse survival compared with subjects classified as ELTS high-risk.

Furthermore, when we re-classified the subjects into revised-CP (ELN CP and ELN AP with increased basophils) and revised-AP (ELN AP with increased blasts and decreased platelets), the TFS and survival curves show a large difference between rCP and rAP. So, there is another possibility of establishing a bi-phasic definition of CML: splitting traditional AP into CP-like (AP with increased basophils only) and BP-like (ELN AP with increased blasts and decreased platelets), but this point requires more clinical and genetic evidence to be confirmed.

Proportions of CP and AP subjects meeting the 2020 ELN TKI-response milestones were similar. The few worse outcomes of AP subjects were only in those failing to meet ELN therapy-response milestones. These data indicate co-variates previously used to define AP are only predictors of TKI-therapy response and not a distinct phase of CML. Our findings were similar using the 2022 International Consensus Classification (ICC) criteria for AP (since the AP definition in WHO were expired, so we used the ICC definition which is near identical in our typescript instead).

Our study has limitations. First, it is single-centre and retrospective. 2nd, few subjects received initial 2G-TKI-therapy. 3rd, we had too few subjects to evaluate those meeting ≥2 AP criteria. 4th, we did not monitor therapy compliance in all subjects. We emphasize we studied subjects with AP at presentation. People presenting in CP and progressing to what is currently defined as AP are the subjects of our next study. However, we suggest our conclusions also apply here and that people developing prior AP features have failed TKI-therapy and no longer in CP.

Based on our data we suggest 2 changes to CML nomenclature. 1st, eliminating AP based on the biology of CML and our clinical data supporting the 2022 WHO CML classification. 2nd, updating the ELTS risk classification to consider a very high-risk cohort with increased blasts and/or decreased platelets. We acknowledge our conclusions and suggestions are controversial and welcome comments.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the local policy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Berman E, Shah NP, Deninger M, Altman JK, Amaya M, Begna K, et al. CML and the WHO: Why? J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:984–6.

Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, Akkari Y, Alaggio R, Apperley JF, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36:1703–19.

Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian RP, Borowitz MJ, Calvo KR, Kvasnicka HM, et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood. 2022;140:1200–28.

Kantarjian HM, Tefferi A. Classification of accelerated phase chronic myeloid leukemia in the era of the BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors: A work in progress. Am J Hematol. 2023;98:1350–3.

Hochhaus A, Baccarani M, Silver RT, Schiffer C, Apperley JF, Cervantes F, et al. European LeukemiaNet 2020 recommendations for treating chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2020;34:966–84.

Radich JP, Dai H, Mao M, Oehler V, Schelter J, Druker B, et al. Gene expression changes associated with progression and response in chronic myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2794–9.

Silver RT, Karanas A, Dear KB, Weil M, Brunner K, Haurani F, et al. Attempted prevention of blast crisis in chronic myeloid leukemia by the use of pulsed doses of cytarabine and lomustine. A Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Leuk Lymphoma. 1992;7:63–8.

Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–405.

Cortes JE, Talpaz M, O’Brien S, Faderl S, Garcia-Manero G, Ferrajoli A, et al. Staging of chronic myeloid leukemia in the imatinib era: an evaluation of the World Health Organization proposal. Cancer. 2006;106:1306–15.

Baccarani M, Deininger MW, Rosti G, Hochhaus A, Soverini S, Apperley JF, et al. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: 2013. Blood. 2013;122:872–84.

Baccarani M, Cortes J, Pane F, Niederwieser D, Saglio G, Apperley J, et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia: an update of concepts and management recommendations of European LeukemiaNet. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6041–51.

Pfirrmann M, Baccarani M, Saussele S, Guilhot J, Cervantes F, Ossenkoppele G, et al. Prognosis of long-term survival considering disease-specific death in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30:48–56.

Qin YZ, Jiang Q, Jiang H, Li JL, Li LD, Zhu HH, et al. Which method better evaluates the molecular response in newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia patients with imatinib treatment, BCR-ABL(IS) or log reduction from the baseline level? Leuk Res. 2013;37:1035–40.

Wang W, Cortes JE, Tang G, Khoury JD, Wang S, Bueso-Ramos CE, et al. Risk stratification of chromosomal abnormalities in chronic myelogenous leukemia in the era of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Blood. 2016;127:2742–50.

Soverini S, Bavaro L, De Benedittis C, Martelli M, Iurlo A, Orofino N, et al. Prospective assessment of NGS-detectable mutations in CML patients with nonoptimal response: the NEXT-in-CML study. Blood. 2020;135:534–41.

Acknowledgements

We thank medical staff and patients’ participants. RPG acknowledges support from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme.

Funding

Funded, in part, by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 81970140 and No. 82370161).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QJ and X-JH designed the study. QJ, SY and X-SZ collected and analysed the data. QJ, SY, X-SZ, RPG and X-JH prepared the typescript. All authors approved the final typescript, take responsibility for the content and agreed to submit for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

RPG is a consultant to BeiGene Ltd., Fusion Pharma LLC, LaJolla NanoMedical Inc., Mingsight Parmaceuticals Inc. and CStone Pharmaceuticals; advisor to Antegene Biotech LLC, Medical Director, FFF Enterprises Inc.; partner, AZAC Inc.; Board of Directors, Russian Foundation for Cancer Research Support; and Scientific Advisory Board: StemRad Ltd.

Ethics approval

Approve by the Ethics Committee of People’s Hospital Beijing compliant with precepts the Helsinki Declaration.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, S., Zhang, X., Gale, R.P. et al. Is there really an accelerated phase of chronic myeloid leukaemia at presentation?. Leukemia 39, 391–399 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-024-02486-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-024-02486-2