Abstract

Lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles enable upconversion stimulated emission depletion microscopy with high photostability and low-intensity near-infrared continuous-wave lasers. Controlling energy transfer dynamics in these nanoparticles is crucial for super-resolution microscopy with minimal laser intensities and high photon budgets. However, traditional methods neglect the spatial distribution of lanthanide ions and its effect on energy transfer dynamics. Here, we introduce topology-driven energy transfer networks in lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles for upconversion stimulated emission depletion microscopy with reduced laser intensities, maintaining a high photon budget. Spatial separation of Yb3+ sensitizers and Tm3+ emitters in 50-nm core-shell nanoparticles enhance energy transfer dynamics for super-resolution microscopy. Topology-dependent energy migration produces strong 450-nm upconversion luminescence under low-power 980-nm excitation. Enhanced cross-relaxation improves optical switching efficiency, achieving a saturation intensity of 0.06 MW cm−2 under excitation at 980 nm and depletion at 808 nm. Super-resolution imaging with a 65-nm lateral resolution is achieved using intensities of 0.03 MW cm−2 for a Gaussian-shaped excitation laser at 980 nm and 1 MW cm−2 for a donut-shaped depletion laser at 808 nm, representing a 10-fold reduction in excitation intensity and a 3-fold reduction in depletion intensity compared to conventional methods. These findings demonstrate the potential of harnessing topology-dependent energy transfer dynamics in upconversion nanoparticles for advancing low-power super-resolution applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy is a far-field super-resolution technique enabling nanoscale 3D imaging, widely applied in life sciences and nanophotonics1,2,3. It employs two overlapping lasers: a Gaussian-shaped laser to excite fluorophores and a donut-shaped laser to suppress fluorescence through stimulated emission, effectively confining emission to the center of the donut. By toggling fluorophores between “ON” and “OFF” states and fine-tuning laser intensities, STED microscopy achieves remarkable spatial resolution4,5. Recent advances in STED microscopy have achieved Ångström-level molecular localization with minimal photobleaching through advanced beam control and fluorophore switching6,7. Adaptive optics has extended these capabilities to deep 3D imaging with sub-50nm isotropic resolution in thick, aberrating tissues8. Integration with deep learning now enables isotropic super-resolution and synapse-level 3D reconstruction of living brain tissue9. Additionally, STED-image scanning microscopy reduces depletion intensity and background for gentle imaging of live, thick samples10, while event-triggered STED enables rapid, real-time capture of dynamic cellular events11. Despite its advantages and recent advancements in optics, computational methods, and probe design12,13,14, challenges such as limited probe photostability and reliance on high-intensity pulsed lasers hinder its broader application. Lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs)15,16, characterized by excited states with long lifetime, provide a promising platform for upconversion STED (U-STED) microscopy17,18, enabling stable upconversion luminescence (UCL) emission with low-intensity near-infrared (NIR) continuous-wave (CW) lasers.

Precise control of energy transfer dynamics in UCNPs19, which stem from complex photophysical transitions among lanthanide ions, is vital for enabling U-STED microscopy with minimal laser intensities and a high photon budget20. In Yb3+, Tm3+-doped UCNPs, increasing Tm3+ doping enhances upconversion and optical switching efficiency by shortening inter-emitter distances and promoting cross-relaxation (CR), a critical mechanism for population inversion21,22. This strategy reduces depletion laser intensity for U-STED microscopy by two orders of magnitude compared to traditional STED microscopy with fluorophores23,24. Additionally, the dynamic response of CR to excitation power further minimizes the required laser intensity25. Increasing Yb3+ doping boosts UCL emission and accelerates kinetics due to a concentrating effect26. However, excessive doping risks concentration quenching27. Similarly, raising excitation power increases the photon budget but elevates laser intensity28,29. Efficient optical switching is alternatively achievable through distinct upconversion pathways in Yb3+, Er3+-doped UCNPs with low lanthanide doping30, multi-step STED processes in Yb3+,Tm3+ systems with low lanthanide doping31, or a cascade-amplified depletion process targeting shared sensitizers in multichromatic UCNPs32. However, traditional methods focus on localized interactions between sensitizers and emitters via lanthanide combinations and concentrations, often neglecting the spatial distribution of lanthanide ions within UCNPs and its impact on energy transfer dynamics.

Recent advancements in UCNP architecture engineering enable precise control of energy transfer dynamics by leveraging distributed interactions between distal lanthanide ions through spatial adjustments within UCNPs, resulting in tunable and enhanced UCL emission33,34,35,36,37. These innovations support high-efficiency optical switching for super-resolution microscopy via surface migration-driven emission depletion38. Additionally, segregating sensitizers and emitters in core-shell UCNPs enhances UCL emission intensity through topology-dependent energy migration (EM) toward the core-shell interface39.

Here, we introduce a novel approach to topology-driven energy transfer networks (ETNs) within lanthanide-doped UCNPs for U-STED microscopy, enabling reduced laser intensities while maintaining a high photon budget. Our theoretical and experimental work shows that spatial separation of Yb3+ sensitizers and Tm3+ emitters within a 50-nm core-shell UCNP structure facilitates the formation of topology-driven ETNs that channel energy toward the core-shell interface, enhancing dynamics for U-STED microscopy. This approach leverages topology-dependent EM within the Yb3+-Yb3+ ETN to enhance energy transfer upconversion (ETU) within the Yb3+-Tm3+ ETN, resulting in strong 450-nm UCL emission under excitation at 980 nm with an intensity of 0.03 MW cm−2. Furthermore, this strategy boosts CR in the intermediate excited state of the Tm3+-Tm3+ ETN, promoting population inversion and improving optical switching efficiency. We achieve a saturation intensity of 0.06 MW cm−2 under excitation at 980 nm and depletion at 808 nm. We perform super-resolution imaging with a lateral resolution of 65 nm using intensities of 0.03 MW cm−2 for a Gaussian-shaped excitation laser at 980 nm and 1 MW cm−2 for a donut-shaped depletion laser at 808 nm. This design achieves a 10-fold reduction in excitation laser intensity and a 3-fold reduction in depletion laser intensity compared to state-of-the-art U-STED microscopy approaches21,22,25,26 (Table S1). These findings demonstrate the potential of exploiting energy transfer dynamics dependent on the topology of UCNPs to advance low-power super-resolution applications in life sciences and nanophotonics.

Results

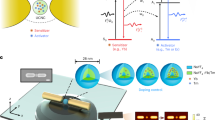

We developed a dual-beam optical system to investigate the impact of lanthanide ion spatial distribution in individual Yb,Tm-doped core-shell UCNPs with high lanthanide ion doping for U-STED microscopy, minimizing laser intensities while preserving a high photon budget (Fig. S1). We fabricated UCNPs with various core-shell structures: sensitizer+emitter@inert with thin core Yb,Tm@Y and thick core Yb,Tm@Y (a typical UCNP structure), sensitizer@emitter@inert with thin intermediate shell Yb@Tm@Y and thick intermediate shell Yb@Tm@Y, and emitter@sensitizer@inert with thin intermediate shell Tm@Yb@Y and thick intermediate shell Tm@Yb@Y configurations (Fig. S2).

Figure 1 illustrates the probing of UCL emission mediated by topology-driven ETNs in core-shell UCNPs under dual-beam irradiation for U-STED microscopy. Figure 1a shows schematics of 450-nm UCL emission from Yb,Tm@Y, Yb@Tm@Y, and Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs under two irradiation conditions: (left) low-power 980-nm CW irradiation and (right) low-power dual-beam irradiation with both 980-nm and 808-nm CW lasers. Under low-power 980-nm CW irradiation, typical Yb,Tm@Y UCNPs do not emit 450-nm UCL emission due to inefficient ETU via local energy transfer from Yb3+ to Tm3+ within the same core. However, low-power dual-beam irradiation with both 980-nm and 808-nm CW lasers results in weak 450-nm UCL emission, attributed to enhanced upconversion via direct 808-nm photon absorption by Tm3+. The UCL emission behavior in core-shell UCNPs with topology-driven ETNs differs from conventional systems. In Yb@Tm@Y UCNPs, Yb3+-Yb3+ networks in the core enhance light absorption under low-power 980-nm CW irradiation, but inefficient topology-driven ETU in the Yb3+-Tm3+ network limits 450-nm UCL emission. Under low-power dual-beam irradiation, Tm3+-Tm3+ networks in the intermediate shell facilitate intense CR processes, inducing population inversion in the intermediate excited state of Tm3+ and enabling efficient optical switching of 450-nm UCL emission. In Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs, Yb3+-Yb3+ networks in the intermediate shell enhance light absorption under low-power 980-nm CW irradiation, and efficient topology-driven ETU in the Yb3+-Tm3+ network results in strong 450-nm UCL emission. Additionally, low-power dual-beam irradiation promotes intense CR processes in Tm3+-Tm3+ networks in the intermediate shell, leading to population inversion and efficient optical switching of 450-nm UCL emission.

a Schematic of 450-nm UCL emission from Yb,Tm@Y, Yb@Tm@Y, and Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs under (left) irradiation with a CW laser at 980 nm and (right) dual-beam irradiation with CW lasers at 980 nm and 808 nm. b Illustration of the spatial separation of Yb3+ sensitizers and Tm3+ emitters within the Tm@Yb@Y UCNP structure, highlighting the formation of topology-driven ETNs. These networks channel energy toward the core-shell interface, enhancing energy dynamics for U-STED microscopy. c Confocal microscopy images showing 450-nm UCL emission from Yb,Tm@Y, Yb@Tm@Y, and Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs under (left) irradiation with a CW laser at 980 nm and (right) dual-becam irradiation with CW lasers at 980 nm and 808 nm. The UCL emission intensity profile across a single UCNP, measured along the dashed white line, is presented. The intensities of the CW lasers at 980 nm and 808 nm are 0.03 MW cm−2 and 1 MW cm−2, respectively. Pixel dwell time: 10 ms. Scale bar: 500 nm

Figure 1b depicts the spatial separation of Yb3+ sensitizers and Tm3+ emitters within the Tm@Yb@Y UCNP structure. The formation of ETNs40 is facilitated by the unique topology of these UCNPs39, channeling energy efficiently toward the core-shell interface, which enhances energy dynamics critical for U-STED microscopy, according to the proposed mechanism as follows. The Yb3+-Yb3+ networks in the intermediate shell strongly absorb 980-nm excitation photons15,16, driving topology-mediated EM toward the core-shell interface39,40,41,42. The Yb3+-Tm3+ networks at the interface induce efficient topology-driven ETU, exciting Tm3+ in the core and generating 450-nm UCL emission19,20. The Tm3+-Tm3+ networks within the core promote CR pathways, leading to population inversion in the intermediate Tm3+ excited state and enabling efficient optical switching of 450-nm UCL emission through STED under 808-nm depletion laser irradiation21,22,25,26. Evidence and arguments supporting the proposed mechanism are provided in the following sections.

We tested the three UCNP configurations under two irradiation conditions. Figure 1c presents confocal microscopy images of the 450-nm UCL emission from the UCNPs, captured under (left) low-power CW Gaussian-shaped excitation laser at 980 nm alone and (right) low-power dual-beam irradiation with an additional CW Gaussian-shaped depletion laser at 808 nm. A corresponding UCL emission intensity profile along the dashed white line illustrates the spatial resolution and intensity of 450-nm UCL emission under each condition. The CW excitation and depletion lasers at 980 nm and 808 nm were operated at intensities of 0.03 MW cm−2 and 1 MW cm−2, respectively, with a pixel dwell time of 10 ms. No 450-nm UCL emission is observed from typical Yb,Tm@Y UCNPs under low-power 980-nm CW irradiation, but weak 450-nm UCL emission is detected under low-power dual-beam irradiation with both 980-nm CW and 808-nm CW lasers. In Yb@Tm@Y UCNPs, 450-nm UCL emission is detected under low-power 980-nm CW irradiation, and it is suppressed under dual-beam 980-nm CW and 808-nm CW irradiation. In Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs, strong 450-nm UCL emission occurs under low-power 980-nm CW irradiation, and it is suppressed under low-power dual-beam 980-nm CW and 808-nm CW irradiation. These results demonstrate that our novel core-shell UCNP structure, which leverages topology-driven ETNs under dual-beam irradiation, optimizes energy interactions between lanthanide ions through a carefully engineered spatial distribution within the nanoparticles. This design enables lower laser intensities while maintaining a high photon budget, highlighting its significant potential for U-STED microscopy.

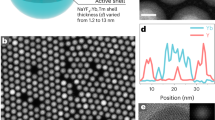

To investigate the relationship between the spatial distribution of lanthanide ions within UCNPs and the enhancement of U-STED microscopy performance, we design and characterize core-shell UCNPs driven by topology-based ETNs. In these designs, Yb3+ ions are used as sensitizers and Tm3+ ions as emitters, both doped at high concentrations. In the first structure (NaYF₄:25%Yb,5%Tm@NaYF₄ UCNPs), Yb3+ and Tm3+ are intermixed within a single core to facilitate local energy transfer. In the “core-to-shell” (NaYF₄:25%Yb@5%Tm@NaYF₄ UCNPs) and “shell-to-core” (NaYF₄:5%Tm@25%Yb@NaYF₄ UCNPs) configurations, Yb3+ forms the spherical core with Tm3+ in the shell, or vice versa. The core and shell volumes are kept equal, allowing for a direct comparison of energy transfer efficiencies between the two compartments (Table S2). The terms “core-to-shell” and “shell-to-core” indicate the direction of energy transfer, either from the core (sensitizer) to the shell (emitter) or in reverse. To minimize surface quenching effects and enhance upconversion efficiency, all three configurations include an outermost inert NaYF₄ shell. Structural analysis of the core-shell UCNPs is conducted using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which reveals their morphology. The core-shell UCNPs with thin cores and intermediate shells have a size of approximately 30 nm, while the core-shell UCNPs with thick cores and intermediate shells measure around 50 nm, both exhibiting a homogeneous size distribution (Fig. S3). X-ray diffraction analysis further confirms their hexagonal β-NaYF₄ phase (Fig. S4).

Figure 2 presents the characterization of UCL emission mediated by topology-based ETNs in core-shell UCNPs for U-STED microscopy under CW excitation at 980 nm. We compare the UCL emission spectra of UCNPs with thin cores and intermediate shells (Fig. 2a) and thick cores and intermediate shells (Fig. 2b) under CW laser excitation at 980 nm with power densities of 0.1 mW μm−2 (top, indicated as ①) and 10 mW μm−2 (bottom, indicated as ②). The proposed UCL emission mechanism involves the absorption of photons at 980 nm by Yb3+ ions, which then transfer energy to Tm3+ ions via ETU, facilitating upconversion from the 3H6 ground state to the 1D2 excited state of Tm3+. The UCL emission at 450 nm originates from the 1D2 to 3F4 transition, with additional emissions at 475 nm, 650 nm, and 808 nm (not shown), corresponding to the 1G4 to 3H6, 1G4 to 3F4, and 3H4 to 3H6 transitions of Tm3+, respectively (Fig. S5). Insets in both panels display high-resolution TEM images of the nanoparticles, illustrating their structural morphology.

a UCL emission spectra of core-shell UCNPs with thin cores and intermediate shells under CW laser excitation at 980 nm with power densities of 0.1 mW μm−2 (top) and 10 mW μm−2 (bottom). Exposure time: 2 s. Inset: high-resolution TEM images of the nanoparticles. Scale bar: 20 nm. b Same to (a), but for core-shell UCNPs with thick cores and intermediate shells. c Power-dependent 450-nm UCL emission spectra of core-shell UCNPs with thin cores and intermediate shells under CW laser excitation at 980 nm with increasing power densities. d Same to (c), but for core-shell UCNPs with thick cores and intermediate shells. e Power-dependent 450-nm UCL emission lifetime measurements for core-shell UCNPs with thin cores and intermediate shells under 980-nm CW laser excitation. f Same to (e), but for core-shell UCNPs with thick cores and intermediate shells

For 30-nm UCNPs, no UCL emission is observed under 0.1 mW μm−2 irradiation, but UCL emission appears at 10 mW μm−2, with the Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs showing the brightest UCL emission. In 50-nm UCNPs, UCL emission is detected at both 0.1 mW μm−2 and 10 mW μm−2, with Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs again exhibiting the brightest emission. These results indicate that the topological arrangement in core-shell UCNPs with ETNs enhances UCL emission via topology-dependent EM from Yb3+ sensitizers to Tm3+ emitters. This process favors UCL emission in the shell-to-core structure, leading to over an order of magnitude increase in UCL emission brightness compared to typical core-shell UCNPs. However, this enhancement is only observed in larger nanoparticles, suggesting efficient activation of ETNs for improved light absorption under low-power 980-nm CW irradiation43.

We illustrate the power-dependent 450-nm UCL emission spectra for core-shell UCNPs with thin cores or intermediate shells (Fig. 2c) and thick cores or intermediate shells (Fig. 2d) under increasing power densities of the CW laser excitation at 980 nm. The intensity of UCL emission IUCL typically follows a power-law relationship with excitation power P, expressed as IUCL∝Pn, where the exponent n represents the number of photons involved in the multiphoton absorption process44. For the 450-nm UCL emission attributed to the transition from 1D2 to 3F4 of the Tm3+ ions, this transition is typically described as a process involving three or four photons45,46. For core-shell UCNPs that do not exhibit topology-driven ETN behavior, the power-dependent 450-nm UCL emission measurement confirms conventional upconversion processes involving three photons, with slopes of 2.8 for Yb,Tm@Y, 2.5 for Yb@Tm@Y, and 2.4 for Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs. Similarly, larger core-shell UCNPs without topology-driven ETN behavior show a slope of 3.6 for Yb,Tm@Y UCNPs, corresponding to a four-photon upconversion process. In contrast, core-shell UCNPs exhibiting topology-driven ETN behavior display unconventional upconversion processes involving two photons. This is reflected in reduced slopes of 2.1 for Yb@Tm@Y and 1.8 for Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs. This deviation is attributed to the efficient ET mechanism in the shell-to-core UCNP structure, which minimizes back energy transfer by separating Yb3+ and Tm3+ ions39. This design enhances the population of excited Tm3+ intermediates and exhibits greater robustness to power density variations compared to core-to-shell structures. These findings underscore the importance of topology-driven ETNs in modulating UCL emission dynamics and offer valuable insights into the energy dynamics of upconversion processes for U-STED microscopy.

Understanding the origin of the 450-nm UCL emission behavior requires exploring the topology-driven formation of ETNs in core-shell UCNPs. To investigate this, we analyze the excited-state dynamics—key features of these complex systems—using time-resolved photoluminescence measurements. We report the power-dependent 450-nm UCL emission lifetimes for core-shell UCNPs with thin (Fig. 2e) or thick (Fig. 2f) cores and intermediate shells under 980-nm CW laser excitation, where lifetime is the time for an intensity drop by 1/e. Using time-resolved luminescence, we investigate the origins of ET dynamics and luminescence lifetimes in these UCNP structures. We find that the lifetimes of 450-nm UCL emission from core-shell UCNPs with thick cores or intermediate shells (44.8 µs for Yb,Tm@Y, 155.8 µs for Yb@Tm@Y, and 165.6 µs for Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs) under excitation at 980 nm with a power density of 1 mW μm−2 are shorter than those with thin cores or intermediate shells (358.6 µs for Yb,Tm@Y, 632.1 µs for Yb@Tm@Y, and 556.2 µs for Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs under excitation at 980 nm with a power density of 1 mW μm−2. This reduction is attributed to accelerated inter-ionic dynamics in larger nanoparticles, driven by the higher concentration of doped lanthanide ions21,22,25,26.

For 50-nm core-shell UCNPs with topology-dependent ETN behavior, the lifetimes of UCNPs with shell-to-core topology-driven dynamics are longer than those with local or core-to-shell topology-driven dynamics. The longer lifetime in the shell-to-core configuration may result from the interface that minimizes the quenching effect of back energy transfer from Tm3+ to Yb3+. In contrast, the reduced lifetime in the core-to-shell architecture likely arises from the proximity of Tm3+ ions to surface quenchers in the interior shell. Similar trend between luminescence and lifetime was observed in other lanthanide-based UCNP systems, where longer luminescent lifetimes typically indicate stronger emission intensity47,48,49,50. Furthermore, our results show that the luminescence lifetimes of 450-nm UCNPs exhibiting topology-driven ETNs decrease with increasing excitation power density, from 165.6 µs under excitation at 980 nm with a power density of 1 mW μm−2 to 96.5 µs under excitation at 980 nm with a power density of 8 mW μm−2. This behavior is attributed to the intrinsic relaxation rates of individual transitions, with the lifetime data interpreted by considering each core-shell UCNP as a complex ET network40. These power-dependent lifetimes reflect the collective effect of multiple minor relaxation pathways that depopulate and repopulate the Tm3+ emitting levels (Fig. S6). At higher excitation powers, Tm3+ states are dynamically modulated through the cumulative effect of multiple, seemingly minor ET processes rather than a single dominant route. This networked interaction leads to nonlinear changes in lifetime behavior, driven by feedback mechanisms—both positive and negative—within the ETN. Such complexity underpins the power-sensitive dynamics of UCNP luminescence and provides mechanistic insight into the lifetime variations observed. Our findings highlight the critical role of topology-driven ETNs in influencing UCL emission dynamics, providing valuable insights into the mechanisms governing upconversion behavior in core-shell UCNPs. These insights are crucial for optimizing their performance in U-STED microscopy.

Figure 3 illustrates the characterization of optical switching in UCL emission facilitated by topology-driven ETNs in core-shell UCNPs under dual-beam irradiation for U-STED microscopy. Figure 3a and S7 present schematic energy level diagrams of the core-shell UCNPs, depicting the optical switching mechanism of 450-nm UCL emission mediated by topology-driven ETNs under dual-beam irradiation. The key processes highlighted include EM within the Yb3+-Yb3+ network, ETU in the Yb3+-Tm3+ network, and CR pathways in the Tm3+-Tm3+ network. The diagrams compare two configurations: low-power irradiation with a CW excitation laser at 980 nm alone (left) and low-power dual-beam irradiation combining the CW excitation with depletion lasers at 980 nm and 808 nm, respectively (right). This comparison emphasizes the modulation of energy transfer pathways that control UCL emission and optical switching.

a Schematic energy level diagram of core-shell UCNPs illustrating the optical switching mechanism of 450-nm UCL emission mediated by topology-based ETNs under dual-beam irradiation. Key processes include EM within the Yb3+-Yb3+ network, ETU in the Yb3+-Tm3+ network, and CR in the Tm3+-Tm3+ network. The diagram compares two configurations: irradiation with a CW excitation laser at 980 nm (left) and dual-beam irradiation combining CW excitation and depletion lasers at 980 nm and 808 nm, respectively (right). b Depletion efficiency of 450-nm UCL emission from Yb,Tm@Y, Yb@Tm@Y, and Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs under dual-beam irradiation, using a CW excitation laser at 980 nm with varying power levels and a CW depletion laser at 808 nm at a fixed power of 10 mW. c Theoretical and experimental normalized intensity of 450-nm UCL emission from Yb,Tm@Y, Yb@Tm@Y, and Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs under dual-beam irradiation. Measurements were conducted with a CW excitation laser at 980 nm with power levels of 0.1 mW and 1 mW, combined with a CW depletion laser at 808 nm at varying power levels

We conducted theoretical modeling to understand UCL emission in core-shell UCNPs driven by topology-based ETNs under dual-beam irradiation. A set of rate equations was developed to analyze the time-dependent electronic population distribution in these UCNPs, with dual-beam irradiation involving CW excitation and depletion laser at 980 nm and 808 nm, respectively (Table S3). The power levels considered for the excitation laser at 980 nm are 0.1 mW and 1 mW, while the depletion laser at 808 nm operates at 10 mW. Our theoretical model accounts for the distinct upconversion processes in typical, core-to-shell, and shell-to-core UCNP structures, despite having identical sensitizer-activator interfaces and concentrations. The differences in EM processes are critical, with shell-to-core UCNPs exhibiting fewer EM steps from Yb3+ sensitizers to Tm3+ emitters, compared to other UCNP configurations34. This difference results in reduced energy losses and a higher population of Tm3+ ions at the 1D₂ level in shell-to-core UCNPs, which in turn leads to stronger 450-nm UCL emission under low-power irradiation with a CW laser at 980 nm.

Extending this study to low-power dual-beam irradiation with both 980-nm and 808-nm CW lasers, we conducted theoretical modeling of the time-dependent electronic population distribution in core-shell UCNPs driven by topology-based ETNs under dual-beam irradiation. The system was excited with a 980-nm beam at powers of 0.1 mW and 1 mW, switched on at t = 0 ms, while an 808-nm depletion beam at a power of 10 mW was activated at t = 5 ms (Fig. S8). We observe an enhancement in the electronic population at the 1D₂ level of Tm3+ ions in Yb,Tm@Y UCNPs when the 808-nm CW laser is activated. This enhancement is attributed to upconversion, where Tm3+ ions directly absorb 808-nm photons, resulting in increased 450-nm UCL emission intensity. In contrast, in Yb@Tm@Y UCNPs, the activation of the CW laser at 808 nm induces depletion of the 3H4 level of Tm3+ ions and a reduction in the 1D₂ level population. This decrease is due to intense CR processes that cause population inversion in the intermediate excited state of Tm3+, enabling efficient optical switching of the 450-nm UCL emission. A similar behavior is observed in Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs, where intense CR processes lead to population inversion and efficient optical switching of the 450-nm UCL emission when the 808-nm laser is activated.

Under high-power irradiation with the 980-nm CW laser, all three UCNP structures exhibit population buildup at the 1D₂ level of Tm3+ ions, leading to intense 450-nm UCL emission. When both 980-nm and 808-nm CW lasers are used in high-power dual-beam irradiation, depletion of the 3H4 level of Tm3+ ions are observed, along with intense CR processes that induce population inversion in the intermediate excited state of Tm3+. This results in efficient optical switching of the 450-nm UCL emission, in line with previous reports21,22. Additionally, we observe an overlap between n₁ (³H₆ ground state) and n₃ (³H₄ intermediate state) of Tm3+ when the 808 nm depletion is activated, indicating a dynamic balance between absorption and STED25. This interplay further supports the accuracy and reliability of our theoretical model in describing the system’s behavior.

Based on these findings, we propose a framework for engineering the electronic population dynamics in core-shell UCNPs driven by topology-based ETNs. Our theoretical model suggests that the emitter@sensitizer@inert UCNP structure offers distinct advantages for U-STED microscopy, primarily due to enhanced 450-nm UCL emission under low-power 980-nm CW excitation and efficient optical switching of 450-nm UCL emission under both low-power 980-nm and 808-nm depletion lasers. This advantage arises from the topology-based shell-to-core ETN dynamics, which incorporate the following processes: 1) Yb3+-Yb3+ networks based on high Yb3+ doping in the intermediate shell facilitate absorption under low-power 980-nm irradiation and intense EM among Yb3+ sensitizers41,42; 2) Yb3+-Tm3+ networks across the core-shell interface enable efficient topology-driven ETU from Yb3+ sensitizers to Tm3+ emitters, leading to intense 450-nm UCL emission39; and 3) Tm3+-Tm3+ networks based on high Tm3+ doping in the core support robust CR processes among Tm3+ emitters, promoting population inversion and enabling efficient optical switching via STED under 808-nm depletion laser irradiation21,22,25,26.

Next, we proceed with the experimental characterization of optical switching of UCL emission driven by topology-based ETNs in core-shell UCNPs under dual-beam irradiation. Figure 3b quantifies the depletion efficiency of 450-nm UCL emission from Yb,Tm@Y, Yb@Tm@Y, and Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs under dual-beam irradiation, with the CW excitation laser at 980 nm operating at varying power levels and the 808-nm CW depletion laser fixed at 10 mW. We achieve a depletion efficiency of the UCL emission at 450 nm of 91% from Yb,Tm@Y UCNPs under dual-beam irradiation with the CW excitation laser at 980 nm operating at 1 mW, and 85% and 92% from Yb@Tm@Y and Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs under dual-beam irradiation with the CW excitation laser at 980 nm at 0.1 mW. Figure S9 illustrates the theoretical modeling of depletion efficiency in core-shell UCNPs, driven by topology-based ETNs under dual-beam irradiation. Figure 3c presents the theoretical and experimental normalized intensities of 450-nm UCL emission from Yb,Tm@Y, Yb@Tm@Y, and Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs under dual-beam irradiation. The measurements were performed using a CW excitation laser at 980 nm with power levels of 1 mW and 0.1 mW for Yb,Tm@Y, Yb@Tm@Y, and Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs, combined with a CW depletion laser at 808 nm operating at varying power levels. The 450-nm UCL emission intensity from Yb,Tm@Y UCNPs decreased when irradiated with a 980-nm CW excitation laser at 1 mW and an 808-nm CW depletion laser at varying powers, attributed to STED of these UCNPs, consistent with previous reports25. In contrast, the intensity increased under irradiation with a 980-nm CW excitation laser at 0.1 mW and an 808-nm CW depletion laser at varying powers, attributed to direct excitation of these UCNPs by the 808-nm CW laser, in line with previous studies21,22. The 450-nm UCL emission intensity from Yb@Tm@Y and Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs decreased under dual-beam irradiation, demonstrating that topology-driven ETNs in these UCNPs enable reduced excitation laser powers down to 0.1 mW and improved optical switching efficiency via STED under irradiation of low-power excitation and depletion lasers. We achieve a saturation intensity of 0.06 MW cm−2 under excitation at 980 nm and depletion at 808 nm for Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs. The reduced saturation intensity observed in emitter@sensitizer@inert UCNPs under low-power dual-beam irradiation indicates that the topology-driven ETN effect in core-shell UCNPs mitigates the constraints of the square root law followed by conventional super-resolution microscopy techniques. Both theoretical modeling and experimental results confirm a 92% depletion efficiency of UCL emission at 450 nm from Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs under dual-beam irradiation, achieved with a CW 980 nm excitation laser at 0.1 mW. These results highlight the effectiveness of core-shell UCNPs with topology-driven ETNs in achieving high depletion efficiencies under low-power dual-beam irradiation.

Modulation cycles of the 808-nm depletion laser, controlled by an optical shutter, enable precise “ON” and “OFF” switching of the 450-nm UCL emission from core-shell UCNPs under 980-nm excitation, as shown in Fig. S10. This demonstrates efficient and robust optical switching with precise dynamic control over multiple irradiation cycles. To further confirm this capability, we performed confocal microscopy imaging under CW excitation and depletion laser irradiation at 980 nm and 808 nm, respectively, detecting the 450-nm UCL emission from the core-shell UCNPs (Fig. S11). This confirms the effective optical switching of 450-nm UCL emission from core-shell UCNPs driven by topology-based ETNs under low-power dual-beam irradiation with both 980-nm CW and 808-nm CW lasers.

Figure 4 highlights the application of U-STED microscopy for imaging core-shell UCNPs with topology-driven ETNs, specifically detecting the 450-nm UCL emission from Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs under dual-beam irradiation. The laser at 808 nm is spatially modulated to create a donut-shaped point spread function (PSF) that overlaps with the Gaussian PSF of the excitation laser at 980 nm at the focal plane (Fig. S12). This overlap selectively deactivates the UCNPs at the edges of the excitation laser, effectively shrinking the excitation spot size below the diffraction limit, consistent with STED microscopy principles.

a Comparison of the theoretical and experimental resolution under dual-beam irradiation. Resolution is measured using a CW Gaussian-shaped excitation laser at 980 nm with an intensity of 0.03 MW cm−2 and an CW donut-shaped depletion laser at 808 nm at increasing intensity levels. Insets: confocal and U-STED microscopy images of 450-nm UCL emission of core-shell Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs with topology-driven ETNs under dual-beam irradiation. b Confocal and U-STED microscopy images of 450-nm UCL emission from core-shell Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs with topology-driven ETNs under dual-beam irradiation using a CW Gaussian-shaped excitation laser at 980 nm and an CW donut-shaped depletion laser at 808 nm. Magnified views are shown (red and blue boxes). The measured intensities of the CW excitation and depletion lasers at 980 nm and 808 nm are 0.03 MW cm−2 and 1 MW cm−2, respectively. Pixel dwell time: 10 ms. Scale bar: 1 μm. c Normalized UCL emission intensity profiles corresponding to the dashed red and blue lines in (b). d Detection of 450-nm UCL emission from core-shell Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs with topology-driven ETNs under dual-beam irradiation for different duration. Inset: confocal and U-STED microscopy images of 450-nm UCL emission after 0 minutes, 30 minutes, and 60 minutes of dual-beam irradiation

Figure 4a compares the theoretical and experimental resolutions achieved under dual-beam irradiation. Measurements were conducted using a CW Gaussian-shaped excitation laser at 980 nm with an intensity of 0.03 MW cm−2 and an CW donut-shaped depletion laser at 808 nm with varying intensity levels. Insets provide representative confocal and U-STED microscopy images of the 450-nm UCL emission, illustrating significant resolution enhancement with increasing depletion laser intensity. Unlike conventional STED microscopy12,13,14, where excitation power is minimized to prevent nonlinear effects, U-STED systems require careful control of excitation intensity due to the nonlinear, multiphoton nature of the upconversion process44. Our theoretical simulations (Figs. S13 and S14), supported by experimental characterization, demonstrate that reducing the 980-nm excitation power results in a narrowing of the focal spot size51. This enhancement is primarily due to the suppression of nonlinear background emission and the avoidance of partial depletion saturation, both of which can broaden the effective PSF at higher excitation levels. These results highlight that operating below the excitation saturation threshold is essential for achieving optimal spatial resolution and contrast in U-STED imaging. Importantly, the simulations confirm that this low-excitation regime maintains sufficient upconversion efficiency for imaging, while significantly minimizing the resolution degradation associated with high excitation powers.

Figure 4b and S15 present comparisons of confocal and U-STED microscopy images of the 450-nm UCL emission. These images were captured using the same dual-laser setup, with measured intensities at the objective’s back aperture of 0.03 MW cm−2 for the excitation laser at 980 nm and 1 MW cm−2 for the depletion laser at 808 nm. Magnified views within the red and blue boxes emphasize the resolution improvements achieved with U-STED microscopy. Figure 4c shows normalized UCL emission intensity profiles corresponding to the dashed red and blue lines in Fig. 4b, quantitatively illustrating the spatial resolution improvement in U-STED imaging. Deconvolution and Gaussian fitting of the data reveal a full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of 65 nm, confirming the superior resolution achieved. We imaged two UCNPs separated by approximately 200 nm. Using conventional confocal microscopy, we obtained a diffraction-limited image in which the two particles could not be resolved—only a single emission peak was visible, with a FWHM of around 780 nm in the corresponding cross-section. In contrast, U-STED microscopy produced a super-resolution image where the two UCNPs were clearly distinguishable, each displaying a distinct emission peak. The corresponding cross-sections revealed FWHMs of approximately 68 nm and 71 nm. These results highlight the capability of our U-STED approach to overcome the diffraction limit and deliver significantly enhanced spatial resolution.

A current limitation of our approach is the long emission lifetimes of the UCNPs used, typically on the order of hundreds of microseconds, which necessitate extended pixel dwell times and thus reduce imaging speed. This trade-off between low illumination intensity and temporal resolution constrains present U-STED microscopy. Recent progress in compositional engineering, such as high Yb3+ doping, has been shown to enhance emission intensity while shortening lifetimes, enabling dwell times as brief as 10 μs25. Additionally, advances in upconversion superfluorescence (SF) have achieved lifetimes below 50 ns52 and down to 2.5 ns53, opening new avenues for fast, low-power, high-resolution U-STED imaging.

Figure 4d evaluates the temporal stability of UCL emission under dual-beam irradiation at 0, 30, and 60-minute intervals. The results demonstrate the durability of topology-driven ETNs for prolonged imaging applications, with particle emission intensity decreasing at a gradual rate of only 2% per hour. Notably, the imaging resolution remains consistent throughout the duration, achieving a diffraction-limited resolution of less than 400 nm in the confocal regime and under 70 nm in the super-resolution U-STED regime. Particle alignment relative to the beams was verified at regular intervals to maintain stable imaging conditions.

Discussion

Compared to conventional STED methods using molecular fluorophores, our U-STED approach presents distinct advantages. Recent developments in STED probes have enhanced imaging performance through greater brightness, photostability, spectral flexibility, and improved suitability for live-cell studies. Examples include monomeric NIR fluorescent proteins for multicolor imaging with reduced phototoxicity54, squaraine-based dyes for high-resolution mitochondrial visualization55, bright fluorophores with large Stokes shifts for improved nanoscopy56, and lipid-based probes enabling prolonged mitochondrial membrane imaging57. Despite these advances, traditional STED systems reliant on organic fluorophores still require high excitation and depletion power, which restricts their application in live or thick specimens due to increased photobleaching and phototoxicity.

The demonstrated reduction in excitation and depletion laser intensities is particularly impactful for biological imaging applications, where phototoxicity and photobleaching often limit live-cell and tissue studies. Our topology-driven ETNs in UCNPs enable super-resolution imaging with significantly reduced photodamage, making long-term and high-fidelity visualization of subcellular structures feasible. This advancement opens new opportunities for real-time imaging of dynamic biological processes at the nanoscale58,59, with potential applications ranging from neuroscience and cell biology to developmental and medical research60,61,62. Moreover, the NIR excitation wavelength used offers improved tissue penetration and minimal autofluorescence, further enhancing the suitability of our approach for in vivo imaging.

UCNPs offer several features beneficial for biological imaging63,64. Their surfaces can be engineered with antibodies, peptides, or oligonucleotides to enable selective targeting of proteins, nucleic acids, or organelles with high specificity65. Surface charge and hydrophilicity modulate cellular uptake pathways, allowing optimization for different cell types66. Although larger than small-molecule dyes, UCNPs can be synthesized with hydrodynamic diameters below 50 nm, facilitating endocytosis and minimizing steric interference. Their intrinsic NIR-excited luminescence enables label-free imaging, reducing autofluorescence and phototoxicity. Importantly, studies have demonstrated minimal cytotoxicity and negligible perturbation of cellular processes when UCNPs are properly coated and dosed67,68,69. Despite challenges in achieving efficient intracellular delivery and minimizing off-target effects, these attributes support the potential of UCNPs as viable probes for super-resolution imaging of biological structures.

Beyond life sciences, the ability to achieve efficient upconversion and optical switching at low laser powers through topology-engineered ETNs paves the way for integration of UCNPs into nanophotonic devices. These include energy-efficient nanoscale light sources70, optical modulators71, and switches72,73 essential for next-generation optical communication and computing technologies74,75. Moving forward, the employment of smaller and brighter lanthanide-doped UCNPs with robust optical stability is critical for expanding the applications of low-power U-STED microscopy based on our approach. Recent advances have introduced strategies to synthesize ultrasmall UCNPs (less than 10 nm in size) with enhanced brightness and stability. These methods include optimizing the host matrix, tailoring lanthanide ion doping concentrations, applying inert shell coatings, and precisely controlling surface interactions76,77,78.

Studying the energy transfer dynamics and directions within UCNPs, along with the spatial distribution, combinations, and concentration of lanthanide ions, is crucial for advancing super-resolution applications that rely on low laser intensities. These results provide deeper insights into these energy transfer mechanisms79,80 and underscore the significance of controlled synthesis methods81,82, especially for heterogeneous lanthanide-doped UCNPs83,84,85,86. Our findings open new avenues for advanced super-resolution techniques with multi-modality, leveraging lanthanide-doped UCNPs to enhance their versatility in state-of-the-art optical imaging systems87,88. The ability to engineer nanocrystals with tailored optical properties will pave the way for next-generation UCNPs, enhancing the efficiency of super-resolution imaging and characterization89,90,91. These advancements in topology-dependent energy transfer within UCNPs could significantly reduce laser intensity requirements, thereby expanding the potential of UCNPs for low-power super-resolution applications in life science92,93,94 and nanophotonics95,96,97,98,99,100.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

Lanthanide-doped core-shell UCNPs are synthesized following previously established protocols with minor modifications101. These UCNPs, obtained from Xi’an Ruixi Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (http://www.xarxbio.com), are used as received without additional processing. The nanoparticle compositions are as follows: 1) NaYF₄:25%Yb,5%Tm@NaYF₄, 2) NaYF₄:25%Yb@5%Tm@NaYF₄, and 3) NaYF₄:5%Tm@25%Yb@NaYF₄. Core-shell UCNPs with thin core and intermediate shells are referred to as Yb,Tm@Y, Yb@Tm@Y, and Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs, while those with thick core and intermediate shells are labeled as Yb,Tm@Y, Yb@Tm@Y, and Tm@Yb@Y UCNPs.

Sample slides containing individually distributed UCNPs are carefully prepared using a standardized procedure. A coverslip is first cleaned by ultrasonication in pure ethanol and Milli-Q water, then air-dried. A 20 μL droplet of UCNPs, diluted to a concentration of 0.01 mg/mL in cyclohexane, is applied to the surface of the coverslip. The sample is immediately rinsed twice with 500 μL of cyclohexane to ensure uniform distribution. Finally, the prepared slides are left to dry at room temperature for 24 hours before measurement.

Sample characterization

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was conducted using a JEOL JEM 2100 F, operating at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV and equipped with an 11-megapixel bottom-mounted Quemesa camera. High-resolution TEM imaging is conducted with a JEM-F200(URP) TEM, also at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) analysis is carried out using a Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer with a Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.54056 Å). Upconversion luminescence (UCL) emission spectra are acquired using an Andor Shamrock 500i imaging spectrometer, coupled with a Leica DFC295 digital color camera, and excited by a 980-nm continuous-wave (CW) laser (Thorlabs, BL976-PAG900).

Dual-beam super-resolution optical system setup

The dual-beam super-resolution optical system setup for U-STED microscopy is developed based on a custom-built confocal microscopy system. Samples are mounted on a computer-controlled, high-precision nanopositioning system utilizing a three-axis piezostage (Physik Instrumente, P-562.3CD). A CW laser at 980 nm (Micro Photons Technology Co., COBRITE-980-M) serves as the excitation source for the UCNPs. After collimation, the 980-nm CW laser passes through two long-pass dichroic mirrors and is focused onto the sample using an oil-immersion objective lens (Olympus, UPlanApo 100X/1.5 oil). The first dichroic mirror (DC1, Semrock, FF880-SDi01-t3-25×36) combines the CW laser at 980 nm with a collimated CW laser at 808 nm (Obis, OBIS-LX-808) for depletion.

The UCL emission from the UCNPs is collected by the same objective lens and separated from the 980-nm CW excitation and 808-nm CW depletion lasers using a second dichroic mirror (DC2, Semrock, Di03-R785-t3-25 × 36). The emission is then coupled into a multimode fiber (Thorlabs, FG050LGA) connected to a single-photon avalanche diode (SPAD, Laser Components, Count T100-FC). To isolate the desired UCL emission bands for imaging, a bandpass filter (Semrock, FF01-448/20-25) and a short-pass filter (Semrock, BSP01-785R-25) are placed in the detection pathway. For super-resolution imaging, a quarter-wave plate (Thorlabs, WPQ10M-808) converts the 808-nm CW laser into circularly polarized light. A half-wave plate (Thorlabs, WPH10M-850) is used in conjunction with Glan-Thompson prisms (Thorlabs, DGL10) to control laser power. Finally, a vortex phase plate (UPOLabs, LETO-808-C) is incorporated into the 808-nm CW laser path to generate a donut-shaped PSF in the focal plane.

UCL emission lifetime measurement system setup

For the measurement of UCL emission lifetime, a 980-nm CW laser (Thorlabs, BL976-PAG900) is employed. This laser is integrated into a commercial optical microscopy system setup (Leica DM2700M microscope) equipped with time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) equipment (Zolix, DCS900PC). The 980-nm CW laser is modulated using a waveform generator (RIGOL, DG5072) to produce 10-μs pulses at a frequency of 500 Hz, facilitating the excitation of UCL emission. Emitted photons are filtered through a bandpass filter (Semrock, SP01-785RU-25) and a short-pass filter (Semrock, FF01-448/20-25) before being detected by the TCSPC system. The effective UCL emission decay time (τeff) is then calculated using the collected data as follows:

where I(t) is the emission intensity as a function of time t and I0 are the maximum emission intensity.

Calculation of lanthanide ion quantity in core-shell UCNPs

Accurately determining the quantity of lanthanide ions in core-shell UCNPs is essential for analyzing their UCL emission, particularly for applications in U-STED microscopy. We calculate the number of Yb3+ and Tm3+ ions in core-shell UCNPs, considering particle geometry, crystal structure, and doping concentrations. The calculations are illustrated for three distinct core-shell UCNP configurations. We assume the UCNPs are spherical, with the volume Vucnp calculated as:

where r is the radius of the UCNP. For core-shell structures, the core volume Vcore and shell volume Vshell are calculated separately as:

For UCNP with β-phase consisting of hexagonal unit cells, the volume of a hexagonal unit cell μVhexagonal is given by:

Where a = 5.91 Å and c = 3.53 Å are lattice parameters describing hexagonal unit cells. Then, the number of unit cells in a UCNP is estimated by:

where is the volume of the core, shell, or total UCNP. Each hexagonal unit cell contains four formula units of NaYF₄. The number of formula units in a given region is:

Yb3+ ions and Tm3+ ions replace Y3+ ions in NaYF₄ formula units according to the doping percentage. For a doping ratio \(x\)%, the number of ions is:

The calculated ion quantities for three different UCNP configurations are reported in Table S2.

Theoretical modeling of UCL emission in core-shell UCNPs driven by topology-based energy transfer networks (ETNs) under dual-beam irradiation

The theoretical modeling of UCL emission in core-shell UCNPs driven by topology-based ETNs under dual-beam irradiation is conducted by developing a set of rate equations. These equations account for the topology-dependent energy migration (EM) within Yb3+-Yb3+ ETNs, energy transfer upconversion (ETU) within Yb3+-Tm3+ ETNs, and cross-relaxation (CR) processes within Tm³⁺-Tm³⁺ ETNs. This approach assumes rapid non-radiative decay for the transitions from 1H5 to 3F4 and from 3F2,3 to 3H4 in Tm3+ ions, effectively merging each pair of energy levels into a single level for simplification.

For Yb3+-Yb3+ ETNs:

• Yb3+ (2F7/2), ground-state nY1:

• Yb3+ (2F5/2), excited-state nY2:

For Yb3+-Tm3+ and Tm-Tm3+ ETNs:

• Yb3+ (2F7/2), ground-state nS1:

• Yb3+ (2F5/2), excited-state nS2:

• Tm3+ (3H6), ground-state n1:

• Tm3+ (3F4, 3H5), excited-state n2:

• Tm3+ (3H4, 3F2,3), excited-state n3:

• Tm3+ (1G4), excited-state n4:

• Tm3+ (1D2), excited-state n5:

where \({P}_{980}=\left(\frac{{\sigma }_{{Yb}}{\lambda }_{980}{I}_{980}}{{hc}}\right)\) is the excitation rate of Yb3+ ions under irradiation at the wavelength of 980 nm, and I980 is the intensity of the laser at the wavelength of 980 nm for excitation; \({P}_{808}=\left(\frac{{\sigma }_{{STED}}{\lambda }_{808}{I}_{808}}{{hc}}\right)\) is the absorption/stimulated emission rate of Tm3+ ions under irradiation at the wavelength of 808 nm, so that the term of \(\left(\frac{{\sigma }_{{STED}}{\lambda }_{808}{I}_{808}}{{hc}}\right)\left({n}_{1}-{n}_{3}\right)\) is the net effect of absorption/stimulated emission, and I808 is the intensity of the laser at the wavelength of 808 nm for depletion; σYb is the absorption cross-section of Yb3+ ions for a laser at 980 nm; σSTED is the absorption/stimulated emission cross-section of Tm3+ ions for a laser at 808 nm; λ980 is the wavelength of the laser for excitation; λ808 is the wavelength of the laser for depletion; h is the Planck’s constant; c is the light speed; WS is the intrinsic decay rate of the excited Yb3+ ions; ci is the upconversion coefficient between the excited Yb3+ ions and Tm3+ ions on level i; Wi is the intrinsic decay rate of Tm3+ ions on level i; bij is the branching ratio for Tm3+ ions decaying from level i to level j, satisfying \({\sum }_{j=1}^{i-1}{b}_{{ij}}=1\); kij is the CR coefficient between Tm3+ ions on level i and level j; EM is the EM coefficient between Yb3+ ions; and n is the electronic population in a specific energy level fulfilling the following conditions:

The theoretical model presented here involves parameters specific to the properties of core-shell UCNPs. The reaction constants are fixed, leaving only I980 and I808 as variables. To validate the theoretical model, the UCL emission driven by topology-based ETNs of core-shell UCNPs is simulated using the parameters in Table S3.

Characterizing UCL emission via power-law dependence

The intensity of UCL emission, IUCL, generally follows a power-law dependence on the excitation power density, P, expressed as IUCL ∝ Pⁿ, where the exponent n indicates the number of photons participating in the multiphoton absorption process44. To determine the exponent n, IUCL was measured at various levels of P. By applying a logarithmic transformation, this equation can be expressed in linear form as log (IUCL) = n log (P) + constant. A plot of log (IUCL) versus log (P) yields a straight line, where the slope of the fitted line corresponds to the exponent n. This value is determined through linear regression of the log-transformed data. In an ideal multiphoton excitation process, n is expected to be an integer, indicating the number of photons involved in excitation. However, deviations from integer values can occur due to factors such as saturation effects, energy transfer, or non-radiative relaxation mechanisms. By analyzing n, the excitation dynamics and energy transfer processes underlying UCL emission were characterized.

Simulated resolution for U-STED microscopy using core-shell UCNPs driven by topology-based ETNs

STED microscopy is a super-resolution imaging technique that combines UCL emission with STED principles to achieve spatial resolution beyond the light diffraction limit. Like conventional STED microscopy, it utilizes a dual-beam optical system consisting of a Gaussian-shaped excitation laser and a donut-shaped depletion laser. These lasers are spatially overlapped to confine the PSF to the nanoscale center of the donut, enabling precise super-resolution imaging. The established theoretical model of UCL emission driven by topology-based ETNs is applied to calculate the electron populations in the energy levels of core-shell UCNPs. By simulating the intensity distribution of the Gaussian-shaped excitation laser at 980 nm and the donut-shaped depletion laser at 808 nm in the focal region, the achievable resolution under dual-beam super-resolution irradiation is evaluated. This setup uses a circularly polarized excitation laser at 980 nm and a circularly polarized vortex depletion laser at 808 nm. The vortex beam is generated with a 2π vortex phase plate, which imposes a helical phase retardation from 0 to 2π, and is focused using a high numerical aperture (NA) objective lens. The resulting electric field distribution in the focal region is expressed as102:

Here, r, and z are the cylindrical coordinates, is the azimuthal angle of the incident laser, is the wave vector, f is the focal length of the high NA objective, α is the maximal NA angle, and θ is the NA angle that varies between 0 and α. Assuming that the optical system is in free space (i.e., the index of refraction n is 1), the maximal angle α is given by α = arcsin (NA/n), where n is the index of refraction of the material in the focal region. A(θ) is the pupil apodization function at the surface of the objective’s aperture, and exp(im\(\phi\)) is the vortex phase factor of the incident laser. For the excitation laser, m = 0, while for the depletion laser passing through the 2π phase plate, m = 1. The symbol relates to the handedness of the circularly polarized lasers. Right circularly polarized lasers are considered in this calculation. For the focal spot calculation, the considered NA for the objective lens is 1.5.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hell, S. W. & Wichmann, J. Breaking the diffraction resolution limit by stimulated emission: stimulated-emission-depletion fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Lett. 19, 780–782, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.19.000780 (1994).

Hell, S. W. Far-field optical nanoscopy. Science 316, 1153–1158, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1137395 (2007).

Sigal, Y. M., Zhou, R. B. & Zhuang, X. W. Visualizing and discovering cellular structures with super-resolution microscopy. Science 361, 880–887, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1137395 (2018).

Klar, T. A. et al. Fluorescence microscopy with diffraction resolution barrier broken by stimulated emission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 8206–8210, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.97.15.8206 (2000).

Westphal, V. & Hell, S. W. Nanoscale resolution in the focal plane of an optical microscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 143903. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.94.143903 (2005).

Weber, M. et al. MINSTED fluorescence localization and nanoscopy. Nat. Photonics 15, 361–366, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-021-00774-2 (2021).

Weber, M. et al. MINSTED nanoscopy enters the Ångström localization range. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 569–576, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01519-4 (2023).

Hao, X. et al. Three-dimensional adaptive optical nanoscopy for thick specimen imaging at sub-50-nm resolution. Nat. Methods 18, 688–693, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01149-9 (2021).

Velicky, P. et al. Dense 4D nanoscale reconstruction of living brain tissue. Nat. Methods 20, 1256–1265, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-023-01936-6 (2023).

Tortarolo, G. et al. Focus image scanning microscopy for sharp and gentle super-resolved microscopy. Nat. Commun. 13, 7723. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35333-y (2022).

Alvelid, J. et al. Event-triggered STED imaging. Nat. Methods 19, 1268–1275, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-022-01588-y (2022).

Vicidomini, G., Bianchini, P. & Diaspro, A. STED super-resolved microscopy. Nat. Methods 15, 173–182, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4593 (2018).

Lukinavičius, G. et al. Stimulated emission depletion microscopy. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 4, 56, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-024-00335-1 (2024).

Xu, Y. Z. et al. Recent advances in luminescent materials for super-resolution imaging via stimulated emission depletion nanoscopy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 667–690, https://doi.org/10.1039/D0CS00676A (2021).

Auzel, F. Upconversion and anti-Stokes processes with f and d ions in solids. Chem. Rev. 104, 139–174, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr020357g (2004).

Haase, M. & Schäfer, H. Upconverting nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 5808–5829, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201005159 (2011).

Jin, D. Y. et al. Nanoparticles for super-resolution microscopy and single-molecule tracking. Nat. Methods 15, 415–423, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-018-0012-4 (2018).

Zhu, X. H. et al. Recent progress of rare-earth doped upconversion nanoparticles: synthesis, optimization, and applications. Adv. Sci. 6, 1901358. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201901358 (2019).

Chan, E. M., Levy, E. S. & Cohen, B. E. Rationally designed energy transfer in upconverting nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 27, 5753–5761, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201500248 (2015).

Lamon, S. et al. Lanthanide ion-doped upconversion nanoparticles for low-energy super-resolution applications. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 252, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-024-01547-6 (2024).

Liu, Y. J. et al. Amplified stimulated emission in upconversion nanoparticles for super-resolution nanoscopy. Nature 543, 229–233, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21366 (2017).

Zhan, Q. Q. et al. Achieving high-efficiency emission depletion nanoscopy by employing cross relaxation in upconversion nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 8, 1058. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01141-y (2017).

Willig, K. I. et al. STED microscopy with continuous wave beams. Nat. Methods 4, 915–918, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth1108 (2007).

Hanne, J. et al. STED nanoscopy with fluorescent quantum dots. Nat. Commun. 6, 7127. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8127 (2015).

Liu, Y. T. et al. Population control of upconversion energy transfer for stimulation emission depletion nanoscopy. Adv. Sci. 10, 2205990. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202205990 (2023).

Peng, X. Y. et al. Fast upconversion super-resolution microscopy with 10 μs per pixel dwell times. Nanoscale 11, 1563–1569, https://doi.org/10.1039/c8nr08986h (2019).

Wen, S. H. et al. Advances in highly doped upconversion nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 9, 2415. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04813-5 (2018).

Zhao, J. B. et al. Single-nanocrystal sensitivity achieved by enhanced upconversion luminescence. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 729–734, https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2013.171 (2013).

Gargas, D. J. et al. Engineering bright sub-10-nm upconverting nanocrystals for single-molecule imaging. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 300–305, https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2014.29 (2014).

Shin, K. et al. Distinct mechanisms for the upconversion of NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+ nanoparticles revealed by stimulated emission depletion. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 9739–9744, https://doi.org/10.1039/c7cp00918f (2017).

Zhang, H. et al. Depleted upconversion luminescence in NaYF4:Yb3+,Tm3+ nanoparticles via simultaneous two-wavelength excitation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 17756–17764, https://doi.org/10.1039/c7cp00099e (2017).

Guo, X. et al. Achieving low-power single-wavelength-pair nanoscopy with NIR-II continuous-wave laser for multi-chromatic probes. Nat. Commun. 13, 2843. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30114-z (2022).

Wang, F. et al. Tuning upconversion through energy migration in core-shell nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 10, 968–973, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3149 (2011).

Zuo, J. et al. Precisely tailoring upconversion dynamics via energy migration in core-shell nanostructures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 3054–3058, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201711606 (2018).

Huang, D. et al. Inhibiting concentration quenching in Yb3+-Tm3+ upconversion nanoparticles by suppressing back energy transfer. Nat. Commun. 16, 4218 (2025).

Lei, Z. D. et al. An excitation navigating energy migration of lanthanide ions in upconversion nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 32, 1906225. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201906225 (2020).

Yan, L. et al. Spatiotemporal control of photochromic upconversion through interfacial energy transfer. Nat. Commun. 15, 1923. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46228-5 (2024).

Pu, R. et al. Super-resolution microscopy enabled by high-efficiency surface-migration emission depletion. Nat. Commun. 13, 6636. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33726-7 (2022).

Zhang, Y. X. et al. Enhancement of single upconversion nanoparticle imaging by topologically segregated core-shell structure with inward energy migration. Nat. Commun. 13, 5927. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33660-8 (2022).

Teitelboim, A. et al. Energy transfer networks within upconverting nanoparticles are complex systems with collective, robust, and history-dependent dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 2678–2689, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b00161 (2019).

Zhou, B. et al. NIR II-responsive photon upconversion through energy migration in an ytterbium sublattice. Nat. Photonics 14, 760–766, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-020-00714-6 (2020).

Mei, S. et al. Networking state of ytterbium ions probing the origin of luminescence quenching and activation in nanocrystals. Adv. Sci. 8, 2003325. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202003325 (2021).

Li, F. et al. Size-dependent lanthanide energy transfer amplifies upconversion luminescence quantum yields. Nat. Photonics 18, 440–449, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-024-01393-3 (2024).

Pollnau, M. et al. Power dependence of upconversion luminescence in lanthanide and transition-metal-ion systems. Phys. Rev. B 61, 3337–3346, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.61.3337 (2000).

Zhang, Z. & Zhang, Y. Orthogonal emissive upconversion nanoparticles: material design and applications. Small 17, 2004552. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202004552 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Multi-photon super-linear image scanning microscopy using upconversion nanoparticles. Laser Photonics Rev. 18, 2400746. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202400746 (2024).

Judd, B. R. Optical absorption intensities of rare-earth ions. Phys. Rev. 127, 750–761, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.127.750 (1962).

Ofelt, G. S. Intensities of crystal spectra of rare-earth ions. J. Chem. Phys. 37, 511–520, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1701366 (1962).

Tessitore, G. et al. The key role of intrinsic lifetime dynamics from upconverting nanosystems in multiemission particle velocimetry. Adv. Mater. 32, 2002266. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202002266 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Independent luminescent lifetime and intensity tuning of upconversion nanoparticles by gradient doping for multiplexed encoding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 7041–7045, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202015273 (2021).

Plöschner, M. et al. Simultaneous super-linear excitation-emission and emission depletion allows imaging of upconversion nanoparticles with higher sub-diffraction resolution. Opt. Express 28, 24308–24326, https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.400651 (2020).

Huang, K. et al. Room-temperature upconverted superfluorescence. Nat. Photonics 16, 737–742, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-022-01060-5 (2022).

Zhou, M. W. et al. Ultrafast upconversion superfluorescence with a sub-2.5 ns lifetime at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 15, 9880. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54314-x (2024).

Matlashov, M. E. et al. A set of monomeric near-infrared fluorescent proteins for multicolor imaging across scales. Nat. Commun. 11, 239. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13897-6 (2020).

Yang, X. S. et al. Mitochondrial dynamics quantitatively revealed by STED nanoscopy with an enhanced squaraine variant probe. Nat. Commun. 11, 3699. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17546-1 (2020).

Jiang, G. W. et al. A synergistic strategy to develop photostable and bright dyes with long Stokes shift for nanoscopy. Nat. Commun. 13, 2264. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29547-3 (2022).

Zheng, S. et al. Long-term super-resolution inner mitochondrial membrane imaging with a lipid probe. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 83–92, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-023-01450-y (2024).

Kim, S. et al. Near-infrared long lifetime upconversion nanoparticles for ultrasensitive microRNA detection via time-gated luminescence resonance energy transfer. Nat. Commun. 16, 7557 (2025).

Huang, G. et al. Upconversion nanoparticles for super-resolution quantification of single small extracellular vesicles. eLight 2, 20, https://doi.org/10.1186/s43593-022-00031-1 (2022).

Di, X. J. et al. Spatiotemporally mapping temperature dynamics of lysosomes and mitochondria using cascade organelle-targeting upconversion nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2207402119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2207402119 (2022).

Jin, S. et al. Instant noninvasive near-infrared deep brain stimulation using optoelectronic nanoparticles without genetic modification. Sci. Adv. 11, eadt4771. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adt4771 (2025).

Peng, Y. et al. Highly effective near-infrared to blue triplet–triplet annihilation upconversion nanoparticles for reversible photobiocatalysis. Nano Lett. 25, 5291–5298, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.5c00117 (2025).

Xu, R. et al. Lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles for biological super-resolution fluorescence imaging. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 3, 100922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrp.2022.100922 (2022).

Mettenbrink, E. M., Yang, W. & Wilhelm, S. Bioimaging with upconversion nanoparticles. Adv. Photonics Res. 3, 2200098, https://doi.org/10.1002/adpr.2022 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Engineered lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles for biosensing and bioimaging application. Microchim. Acta 189, 109, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00604-022-05180-1 (2022).

Liang, G. F. et al. Recent progress in the development of upconversion nanomaterials in bioimaging and disease treatment. J. Nanobiotechnol. 18, 154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-020-00713-3 (2020).

Gnach, A. et al. Upconverting nanoparticles: assessing the toxicity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 1561–1584, https://doi.org/10.1039/c4cs00177j (2015).

Sun, Y. et al. The biosafety of lanthanide upconversion nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 1509–1525, https://doi.org/10.1039/c4cs00175c (2015).

Oliveira, H. et al. Critical considerations on the clinical translation of upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs): recommendations from the European upconversion network (COST Action CM1403). Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8, 1801233. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.201801233 (2019).

Zhang, Q. Y. et al. Multi-photon polymerization using upconversion nanoparticles for tunable feature-size printing. Nanophotonics 12, 1527–1536 (2023).

Khosh Abady, K. et al. Enhancing the upconversion efficiency of NaYF4:Yb,Er microparticles for infrared vision applications. Sci. Rep. 13, 8408. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35164-x (2023).

Shan, X. C. et al. Sub-femtonewton force sensing in solution by super-resolved photonic force microscopy. Nat. Photonics 18, 913–921, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-024-01462-7 (2024).

Gu, W. Z. et al. Femtosecond laser melting upconversion nanoparticles for sub-micrometer optical patterning. Opt. Express 33, 16317–16327, https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.557532 (2025).

Lamon, S. et al. Neuromorphic optical data storage enabled by nanophotonics: a perspective. ACS Photonics 11, 874–891, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.3c01253 (2024).

Yu, H. Y. et al. Dual-material metastructure for simultaneous filtering and focusing of incoherent white light. ACS Photonics 11, 60–67, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.3c00944 (2024).

Li, C. X. et al. Current progress in the controlled synthesis and biomedical applications of ultrasmall (<10 nm) NaREF4 nanoparticles. Dalton Trans. 47, 8538–8556, https://doi.org/10.1039/c8dt00258d (2018).

Joshi, T., Mamat, C. & Stephan, H. Contemporary synthesis of ultrasmall (sub-10 nm) upconverting nanomaterials. ChemistryOpen 9, 703–712, https://doi.org/10.1002/open.202000073 (2020).

Xu, H. et al. Anomalous upconversion amplification induced by surface reconstruction in lanthanide sublattices. Nat. Photonics 15, 732–737, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-021-00862-3 (2021).

Schroter, A. & Hirsch, T. Control of luminescence and interfacial properties as perspective for upconversion nanoparticles. Small 20, 2306042. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202306042 (2024).

Wu, J. Z. et al. Upconversion nanoparticles based sensing: from design to point-of-care testing. Small 20, 2311729. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202311729 (2024).

Huang, F. H. et al. Suppression of cation intermixing highly boosts the performance of core-shell lanthanide upconversion nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 17621–17631, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.3c03019 (2023).

Xia, X. J. et al. Accelerating the design of multishell upconverting nanoparticles through Bayesian optimization. Nano Lett. 23, 11129–11136, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c03568 (2023).

Liu, D. M. et al. Three-dimensional controlled growth of monodisperse sub-50 nm heterogeneous nanocrystals. Nat. Commun. 7, 10254. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10254 (2016).

Liu, X. W. et al. Hedgehog-like upconversion crystals: controlled growth and molecular sensing at single-particle level. Adv. Mater. 29, 1702315. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201702315 (2017).

Chen, C. H. et al. Multi-photon near-infrared emission saturation nanoscopy using upconversion nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 9, 3290. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05842-w (2018).

Wen, S. H. et al. Nanorods with multidimensional optical information beyond the diffraction limit. Nat. Commun. 11, 6047. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19952-x (2020).

Denkova, D. et al. 3D sub-diffraction imaging in a conventional confocal configuration by exploiting super-linear emitters. Nat. Commun. 10, 3695. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11603-0 (2019).

Meng, Y. J. et al. Bright single-nanocrystal upconversion at sub 0.5 W cm−2 irradiance via coupling to single nanocavity mode. Nat. Photonics 17, 73–81, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-022-01101-z (2023).

Lu, Y. et al. Upconversion-based chiral nanoprobe for highly selective dual-mode sensing and bioimaging of hydrogen sulfide in vitro and in vivo. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 180, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-024-01539-6 (2024).

Tu, L. P. et al. Significant enhancement of the upconversion emission in highly Er3+-doped nanoparticles at cryogenic temperatures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202217100. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202217100 (2023).

Ma, Y. Q. et al. Mammalian near-infrared image vision through injectable and self-powered retinal nanoantennae. Cell 177, 243–255.e15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.038 (2019).

Chen, Y. W. et al. Noninvasive in vivo 3D bioprinting. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba7406. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba7406 (2020).

Zhang, P. et al. Upconversion 3D bioprinting for noninvasive in vivo molding. Adv. Mater. 36, 2310617. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202310617 (2024).

Shida, J. F. et al. Multicolor long-term single-particle tracking using 10 nm upconverting nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 24, 4194–4201, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.4c00207 (2024).

Lamon, S. et al. Millisecond-timescale, high-efficiency modulation of upconversion luminescence by photochemically derived graphene. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7, 1901345. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201901345 (2019).

Shang, Y. F. et al. Low threshold lasing emissions from a single upconversion nanocrystal. Nat. Commun. 11, 6156. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19797-4 (2020).

Huang, K. F. et al. Orthogonal trichromatic upconversion with high color purity in core-shell nanoparticles for a full-color display. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218491. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202218491 (2023).

Mun, K. R. et al. Elemental-migration-assisted full-color-tunable upconversion nanoparticles for video-rate three-dimensional volumetric displays. Nano Lett. 23, 3014–3022, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c00397 (2023).

Gu, W. et al. Thermo-optical sub-micrometer ultrahigh luminescence emission tuning in hybrid organic–inorganic upconversion nanocomposites for data stora ge and anticounterfeiting. Adv. Opt. Mater. 13, 2402248. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202402248 (2025).

Ye, Z. Y., Harrington, B. & Pickel, A. D. Optical super-resolution nanothermometry via stimulated emission depletion imaging of upconverting nanoparticles. Sci. Adv. 10, eado6268. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ado6268 (2024).

Wang, F., Deng, R. R. & Liu, X. G. Preparation of core-shell NaGdF4 nanoparticles doped with luminescent lanthanide ions to be used as upconversion-based probes. Nat. Protoc. 9, 1634–1644, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2014.111 (2014).

Gu, M. Advanced Optical Imaging Theory. (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2000).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development program of China (Grant No. 2022YFB2804301 and Grant No. 2021YFB2802000), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (Grant No. 21DZ1100500), the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project, the Shanghai Frontiers Science Center Program (2021-2025 No. 20), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61975123 and Grant No. 62205208), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (3722904001, 3722904006), and the Shanghai Super Postdoctoral Incentive Scheme (5B22904002, 5B22904006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. conceived the research concept and experimental design with guidance from Q.Z. and M.G. S.L. built the optical system setup. S.L. and W.G., a PhD student co-supervised by Q.Z. and S.L., conducted the material characterization, performed the optical experiments, and analyzed the data. S.L. wrote the initial manuscript draft. All authors reviewed and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Min Gu is an Editor for the journal, and no other author has reported any competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, W., Lamon, S., Yu, H. et al. Topology-driven energy transfer networks for upconversion stimulated emission depletion microscopy. Light Sci Appl 14, 395 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-025-02054-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-025-02054-y