Abstract

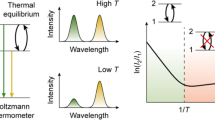

A new ratiometric Boltzmann thermometry approach is presented for the narrow-line red-emitting bright phosphor Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N. It relies on thermalization between the two excited states 2Eg(2G) and 2T1g(2G) of Cr3+ with an energy gap of 620 cm−1 for optimized thermometry at room temperature. It is shown that nonradiative coupling between these excited states is very fast, with rates in the order of several µs−1. Due to the comparably slow radiative decay (kr = 0.033 ms−1) of the lowest excited 2Eg(2G) state, the dynamic working range of this Boltzmann thermometer for the deep red spectral range is exceptionally wide, between <77 K and >873 K, even outperforming the classic workhorse example of Er3+. At temperatures above 340 K, also spectrally well-resolved broad-band emission due to the spin-allowed 4T2g(4F) → 4A2g(4F) transition is detectable, which simultaneously offers a possibility of very sensitive (Sr(500 K) > 2% K−1) ratiometric Boltzmann-type crossover thermometry for higher temperatures. These findings imply that Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N is a particularly robust and bright red luminescent thermometer with a record-breaking dynamic working range for a luminescent transition metal ion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Remote luminescence thermometers gained increasing attraction for applications in biomedical, physical, and technological fields in the last two decades1,2. Within that time, the field matured, and not only has it now been established how to specifically optimize the performance of luminescent thermometers, but also which artifacts can arise that may introduce systematic errors2,3,4,5. Various application areas have been explored for this technique, such as catalysis6, flow velocimetry6, or more selective applications as intracellular imaging7,8 or measurements of heat transfer at the nanoscale9,10,11,12. Among the various possibilities to perform luminescence thermometry, the purpose of narrow-line emission from two thermally coupled levels has become particularly attractive13. The intensity ratio of such luminescent thermometers obeys Boltzmann’s law and thus allows a simple and accurate temperature control with clear physical input14. The major representative emitters for this class of luminescence thermometers are the trivalent lanthanoids (Ln3+) with their rich 4fn energy level structure throughout the ultraviolet (UV), visible, and near-infrared spectral range13,15. Trivalent lanthanoids have many energy levels with definite splittings in the order of a few kBT for temperature ranges varying by the respective splitting energies and have characteristic narrow 4fn-4fn (n = 2 for Pr3+ to n = 13 for Yb3+) emission lines for accurate ratiometric luminescence thermometry.

Despite their promising features for this application area, trivalent lanthanoid ions generally suffer from small absorption cross sections of their 4fn ↔ 4fn transitions (10−20 to 10−21 cm2)16,17 that limits their overall brightness. This can pose problems for the precision of luminescent thermometers. Transition metal ions with dn-dn transitions usually show higher absorption cross sections (10−19 to 10−20 cm2)18,19,20,21 for a wide optical range22 than their lanthanoid congeners. In addition, the broad-band nature of the dn-dn transitions of transition metal ions additionally enhances the brightness as the integrated absorption cross section can then get enhanced by a factor of 102 to 103 compared to lanthanoid ions. However, it is difficult to transfer the appealing concept of Boltzmann thermometry using narrow-line emission from two thermally coupled excited levels to luminescent transition metal ions, as these typically show broad emission bands. This makes it difficult to accurately determine intensity ratios and the luminescence is also prone to thermal quenching by nonradiative crossover23,24. The exploitation of vibronic fine structure (Stokes and anti-Stokes lines) in the case of narrow-line emitting Mn4+ is a possible alternative that allows for combining stronger absorption strengths with narrow-line emission25. In addition, ratiometric thermometry is promising for the 3d3 ion Cr3+ in strong ligand fields using narrow line emission from the two excited states 2Eg(2G) and 2T1g(2G) in an octahedral ligand field. Absorption at higher energies can occur upon one-electron excitation into the more antibonding eg-type orbitals under spin conservation, thus giving rise to broad bands with higher absorption cross sections (and thus brightness) than for the trivalent lanthanoid ions.

A well-known representative for this type of phosphor is ruby, α-Al2O3:Cr3+. While it shows intense 4T2(g)(4F) ← 4A2(g)(4F)-based absorption in the green range, giving rise to its deep red color, the emission spectrum of ruby is dominated by two narrow 2E(g)(2G) → 4A2(g)(4F)-based so-called R lines. The two R lines arise from radiative transitions out of the two Kramers’ doublets \(\bar{\text{E}}\) and \(2\bar{\text{A}}\) as a consequence of weak spin-orbit coupling and the slight trigonal distortion at the Al sites in corundum-type α-Al2O3, allowing for luminescence thermometry at cryogenic temperatures by exploitation of the small energy gap (ΔE = 29 cm−1) between the two Kramers’ doublets26.

Robust ratiometric Boltzmann thermometry with Cr3+ at around room temperature would be possible by thermal coupling between the two excited spin-flip states 2E(g)(2G) and 2T1(g)(2G) with a mutual energy gap of 540 cm−1 for ruby and 620 cm−1 for AlB4O6N:Cr3+ (Topt ≈ 250 K–430 K)27. Both narrow-line transitions to the ground level are only visible in very strong ligand fields, in which no crossover between the 2E(g)(2G) and 4T2(g)(4F) states interferes that gives rise to a broad background due to the spin-allowed 4T2(g)(4F) → 4A2(g)(4F) emission. A strong crystal field also raises the luminescence quenching temperature of the 2E(g) and 2T1g(2G) emissions. While the energy gap of the two thermally coupled excited levels determines the optimum temperature range (Topt), the excited state dynamics have a strong impact on its dynamic working range. Only if the nonradiative transition rates (which increase with temperature) between the two levels become faster than the radiative decay rate from either of the two excited states, is a Boltzmann behavior of the luminescence intensity ratio (LIR) to be expected14,28. Conversely, analysis of the dynamic working range of a luminescence thermometer can be a useful tool for a better understanding of the intrinsic nonradiative coupling strength between excited states. Apart from the well-known energy-gap law stating that the intrinsic nonradiative transition rate becomes exponentially damped with an increasing number p of effective vibrational modes29,30, there are not many other factors known to have a significant impact on the nonradiative coupling strength. This is in strong contrast to radiative transitions, for which mechanisms for lifting selection rules, control over the local photonic density of states, and cavity quantum electrodynamics have been established for a long time already29,31,32,33. In the case of lanthanoid ions, some efforts have been made to theoretically describe nonradiative transitions in a similar way to radiative transitions by e.g. van Dijk and Schuurmans34,35, Orlovskii and Pukhov36,37,38as well as Macfarlane39. They demonstrated that multi-phonon nonradiative relaxation rates could also be described in an analogous framework to Judd-Ofelt theory, as they are proportional to the oscillator strength of the 4fn-4fn transition involved in the lanthanoid ion that transfers the energy to a vibrational overtone via Förster-type dipole-dipole interaction40. In line with those findings, some of us recently showed that this can have a significant impact on the dynamic working range of lanthanoid ions as luminescent Boltzmann thermometers41. In contrast, selection rules for nonradiative relaxation in organic emitters are much more established42,43,44, as internal (spin-allowed) conversion between excited spin singlet states is usually in the order of ps, while (spin-forbidden) intersystem crossing to excited spin triplet states typically occurs in the order of ns to µs. In addition to that, El-Sayed’s rules allow for estimating when intersystem crossing is expectedly to be faster depending on the change in the contributing orbital nature of the related excited states45.

Recently, we reported about Al0.97Cr0.03B4O6N as an analog of ruby with an even stronger ligand field for incorporated Cr3+ ions than in α-Al2O327. Its structure is homeotypic to swedenborgite (NaBe4SbO746) and the nitridosilicate BaYbSi4N747 with Al sites that are almost perfectly octahedrally coordinated by six O2- ions27,48. This structural feature gives rise to the observation of a single R line since the high symmetry does not split the 2Eg(2G) level even under the action of spin-orbit coupling, in contrast to ruby. The high symmetry of the Al sites in AlB4O6N provides an ideal test ground for selection rules of multi-phonon type nonradiative transitions for states that sensitively react to the surrounding ligand field. It was thus the purpose of this work to explicitly compare the thermometric performance of the 2T1(g)(2G)–2E(g)(2G) gap of Cr3+ in Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N (see Fig. 1a) and α-Al2O3:Cr3+ offering a robust ratiometric thermometry concept with a transition metal ion.

a Representative emission spectra of Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N at selected temperatures depicting both narrow-line 2T1g, 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F)- and broad-band 4T2g(4F) → 4A2g(4F)-based emission (break at y axis for better visualization of both emission bands). b Effective Tanabe-Sugano diagram based on estimated Racah parameters B and C for Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N. The vertical dashed line depicts the Dq/B ratio for Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N. The d3 micro-configurations in an octahedral crystal field related to the multielectron states are depicted on the right side of each diagram with the respective emission denoted as a colored arrow. c Structure of Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N with view along the crystallographic a axis emphasizing the octahedral coordination of the Al3+/Cr3+ ions (in grey) embedded in a condensed network of [BO3N]6- tetrahedra (O atoms in blue, N atoms in green)

Results

Structural and photoluminescence properties of Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N

The photoluminescence of AlB4O6N activated with 0.7 mol% Cr3+ indicates its potential as an alternative remote optical pressure calibration standard to ruby (for diffraction patterns and structural data, see Figs. S1–S3 and Tab. S1)27. CrB4O6N has been reported to have a light red body color49, while powdered Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N is colorless. The low concentration of Cr3+ is necessary to avoid quenching that usually occurs in phosphors at higher activator fractions and thus affects the decay kinetics of the relevant excited states investigated within this work. Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N shows red narrow-line luminescence based on the 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F) upon excitation at 365 nm, similar to ruby (see Fig. 1a). Upon temperature increase, however, a broad emission band related to the 4T2g(4F) → 4A2g(4F) transition of Cr3+ can be detected. Figure 1b depicts the Tanabe-Sugano diagrams for a d3 ion using the estimated Racah and ligand field parameters for Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N. Additional factors compared to α-Al2O3:Cr3+ as the absorption cross section for the excitation source, pressure stability, the temperature-dependent shift, and the relative sensitivity were discussed by some of us before27. Both compounds contain octahedrally coordinated Al3+ sites with a low distortion leading to a lowered site symmetry of C3v. These are favored for the incorporation of Cr3+ ions in 3d3 configuration. The average Al–O bond lengths for the Al site (see the gray colored octahedron in Fig. 1c) in AlB4O6N (1.89 Å) and α-Al2O3:Cr3+ (1.91 Å), based on single-crystal data matching with the spectrally resolved transition energies of Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N and α-Al2O3 (<1 ppm Cr3+) in the ligand field approach by the angular overlap model, suggest a slightly stronger ligand field acting on the 3d orbitals of the incorporated Cr3+ ions in AlB4O6N, which is beneficial for a high energy of the excited 4T2g(4F) state27.

In addition, the PLE spectra of AlB4O6N reveal the presence of the broad-band 4T2g(4F) ← 4A2g(4F) transition at 510 nm and 4T1g(4F) ← 4A2g(4F) transition at 393 nm (see Fig. S4). The emission spectrum is dominated by a strong narrow zero-phonon line related to the 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F) transition over the entire temperature course (see Fig. 1a), which does not split any further in an octahedral ligand field under the action of spin-orbit coupling as the 2Eg(2G) state retains its total degeneracy of 2 (spin degeneracy) x 2 (orbital degeneracy) = 4 (see also Figs. S5 for Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N and S6 for α-Al1.993Cr0.007O3).

Ratiometric Boltzmann-type luminescence thermometry in Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N

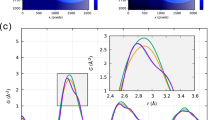

The experimental details for photoluminescence measurements of this work are provided in the Supplementary Information (Section S1.2). Figure 2a depicts the temperature-dependent emission spectra of Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N from 77 K to 848 K, which is compared with the temperature-dependent luminescence of classic ruby (α-Al1.993Cr0.007O3, Figs. S7 and S8). In both cases, dominant narrow-line, spin-forbidden emission from the 2Eg(2G) state is observed with a temperature-induced red-shift due to the thermal expansion and a consequently increasing Cr–O bond length, while the line broadening is based on stronger electron-phonon coupling (see Figs. 1a and 2a)27,50. Another transition based on the emission from the 2T1g(2G) state is also detectable at around 655 nm, which must be a consequence of thermalization with the 2Eg(2G) state. Since both the 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F) and 2T1g(2G) → 4A2g(4F) transitions are sufficiently narrow (FWHM < 30 cm−1), an energy gap of 614 cm−1 can be spectrally resolved – a situation that is otherwise typically only encountered for the trivalent lanthanoid ions with their narrow-line 4fn ↔ 4fn transitions. The LIR of the two observed radiative transitions indeed shows a clear Boltzmann-type behavior down to at least 77 K according to51

a Temperature-dependent normalized emission spectra of Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N in a semi-logarithmic scale. The integration ranges for the 2T1g(2G) → 4A2g(4F) and 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F) transitions are highlighted as grey areas, respectively. b Plot of the temperature-dependent LIR R21(T) between the integrated intensities of the 2T1g(2G) → 4A2g(4F) and 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F)-based emission lines against the inverse temperature. The red lines are the least-squares fit to Eq. 1. The errors in b were estimated assuming Poissonian photon counting statistics of the photomultiplier

with g2 = 6 and g1 = 4 as degeneracies of the 2T1g(2G) = |2〉 and 2Eg(2G) = |1〉 states, C = k2r/k1r as the electronic preexponential factor representing the ratio of radiative decay constants of the two excited states, ΔE21 as the energy gap, and kB as the Boltzmann constant. The fit of the experimentally observed intensity ratios to Eq. 1 (ref. 51) in Fig. 2b shows an excellent agreement over the full temperature range investigated (77 – 850 K) with an energy difference ΔE21 of (619 ± 2) cm−1 (see Figs. S5c, d and Table S4). This finding indicates an extraordinarily large dynamic working range for Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N as a luminescent thermometer. That type of ratiometric thermometry with Cr3+ has so far been scarcely considered, given the relatively rare scenario of a sufficiently strong ligand field in most inorganic compounds. A representative example was reported by Heinze et al. in the case of the complex [Cr(ddpd)2]3+ (ddpd = N,N′-dimethyl-N,N′-dipyridin-2-ylpyridine-2,6-diamine) known as “molecular ruby”52. Instead, the majority of reported works on luminescence thermometry with Cr3+ rely on the thermal crossover to the excited 4T2g(4F) state that gives rise to broad-band emission of Cr3+ 53,54,55,56,57. In the case of α-Al2O3:Cr3+, also ratiometric cryothermometry exploiting the small energy gap (ΔE21 = 29 cm−1) between the two Kramers’ doublets \(2\bar{{\rm{A}}}\) (Γ5,6) and \(\bar{{\rm{E}}}\) (Γ4) has been reported55,58. Finally, lifetime-based thermometry approaches were investigated both for Cr3+ and the isoelectronic Mn4+ ion59,60,61,62,63,64,65. Thermal occupation of the 4T2g(4F) excited state with a spin-allowed transition to the ground state gives rise to pronounced shortening of the luminescence decay time in a temperature range depending on the 2Eg(2G) – 4T2g(4F) energy gap.

A limitation to the presented new thermometric approach with Cr3+ at high temperatures is thermal crossover to the excited 4T2g(4F) state (see also Fig. 1b). Both in Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N and α-Al2O3:Cr3+, this quenching pathway only becomes significant at temperatures above T1/2 = 570 K (Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N) and T1/2 = 463 K (α-Al2O3: < 1ppm Cr3+) (see Fig. S9). The higher quenching temperature of Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N than in α-Al2O3:Cr3+ can be related to the stronger ligand field splitting 10Dq acting on the 3d orbitals of the Cr3+ activator in AlB4O6N. As a result of the large crystal field strength, the 4T2g(4F) excited state is at a very high energy, even much higher than in ruby, which makes it possible to observe both 2Eg(2G) and 2T1g(2G) narrow-line emission up to very high temperatures and can explain the record high quenching temperature for the Cr3+ emission. Overall, the use of the 2T1g(2G)- and 2Eg(2G)-based emission lines in Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N constitutes an example of a particularly robust ratiometric thermometer with a record dynamic working range between at least 77 K and 850 K.

Given the energy gap of ΔE21 = (619 ± 2) cm−1 between the 2Eg(2G) and 2T1g(2G) state in Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N, the optimum temperature range Topt defined by

is Topt ∈ [260 K, 445 K]14. The energy gap also matches the spectroscopically determined value from excitation spectra of 614 cm−1 at 20 K (see Fig. S4 and Table S3). Thus, ratiometric thermometry with the two radiative narrow-line transitions 2T1g(2G) → 4A2g(4F) and 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F) is suited for thermodynamically optimized, precise temperature sensing in a wide range, including room temperature. Within Topt, the relative sensitivity,

with all symbols as defined above, varies from Sr(260 K) = 1.32% K−1 to Sr(445 K) = 0.45% K−1 for Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N (see Fig. S10a). However, it should be stressed that the relative sensitivity alone does not determine the overall statistical precision of a ratiometric luminescent thermometer, but brightness is as important3. If photons are detected with a photon counting system, the relative statistical uncertainty of a ratiometric luminescent thermometer is given by14

with I10 as a given intensity of the lower energetic (typically more intense) emission, in this case the 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F)-based emission, and R21(T) as the temperature-dependent LIR. The temperature-dependent evolution of the relative statistical uncertainty of the presented thermometry concept with Cr3+ is schematically depicted in Fig. S10b for exemplary values of I10. If the integrated intensity of the 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F) exceeds 106 counts, theoretically expected minimum relative temperature readout uncertainties σT/T close to 0.1% are feasible within Topt with Cr3+-activated AlB4O6N. In fact, this thermometer performs better than classic α-Al1.993Cr0.007O3 (see Table 1 and Fig. S10). Cycling experiments for selected LIRs also demonstrate that both Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N and α-Al1.993Cr0.007O3 work as reproducible, robust thermometers (see Figs. S11–S13).

Characterization of the nonradiative transition between the 2 T 1g(2G) and 2 E g(2G) level in Cr3+-activated AlB4O6N and α-Al2O3

At sufficiently low temperatures, the LIR of Cr3+-activated AlB4O6N is expected to deviate from Boltzmann behavior14,28. This deviation can be related to the decoupling of the 2T1g(2G) and 2Eg(2G) states and offers information about the mutual intrinsic nonradiative coupling strength, knr(0), which determines the dynamic working range of a luminescent thermometer. At low temperatures, the nonradiative absorption rate, \({k}_{\text{nr}}^{\text{abs}}(T)\), from the lower excited state |1〉 to the higher excited one |2〉 may not be competitive to the total decay rate from the lower excited level |1〉, k1 = k1r + kquench = k1r/ϕ1(0) (with ϕ1(0) as the internal quantum yield from level |1〉), and thermal equilibrium between the two excited states cannot be sustained anymore. For resonant bridging of the two excited states by one vibrational quantum, this equilibrium leads to a kinetically defined onset temperature (Ton) for thermalization between the two excited states of41

with ΔE21 as the energy gap between the two excited states, kB as the Boltzmann constant, g2 as the degeneracy of the higher energetic excited state |2〉 (here: g2 = 6), and knr(0) as the intrinsic nonradiative transition rate constant. Formally, any deviation of the LIR from Boltzmann behavior or mutual deviation of the luminescent decay times of the two coupled excited states at sufficiently low temperatures can give an indication of the previously mentioned decoupling of the two excited states. Detection of the time-resolved luminescence from both the 2T1g(2G) and 2Eg(2G) state reveal similar decay times within statistical significance down to 80 K (see Fig. S14). This implies thermal coupling of the two excited states even at that low temperature. Additional confirmation can be gained from an estimate of the luminescence intensity of the 2T1g(2G) → 4A2g(4F)-related emission according to Boltzmann’s law (R21(77 K) ≈ 1.52 ∙ 10−5 based on Eq. 1), in close agreement to the experimentally estimated (height-based) LIR of 1.57 ∙ 10−5 (see Fig. 2a) at 77 K. Overall, the thermal coupling between the 2T1g(2G) and 2Eg(2G) states in Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N must be very fast and allows a rough estimate knr(0) > 1 µs−1 according to Eq. 5. It was not possible to derive a more accurate value as the determination relies on the measurable intensity of the 2T1g(2G) → 4A2g(4F)-based emission, which has a very low signal-to-noise ratio below 77 K. We can, however, anticipate that the value of knr(0) = 1 µs−1 in Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N is still severely underestimated, as transient absorption studies on ruby at liq. He temperatures (4.2 K) revealed a corresponding nonradiative transition rate of knr(0) = (400 ± 80) µs−1 66, while Hartree-Fock calculations even led to higher estimates (knr(0) ≈ 8 ps−1)56,67. Future pump-probe or photon echo experiments on Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N may help find a more accurate estimate of the nonradiative coupling rate constant knr(0) for the 2T1g(2G) → 2Eg(2G) transition and compare it to the rates known for the trivalent lanthanoid ions34,35. That concept of selection rules for nonradiative transitions is well-established for intersystem crossing in molecular emitters68,69 and has been recently indicated for the lanthanoid ions by Burshtein70, but is so far lacking a more general picture. Assuming a similarly high value of knr(0) ≈ 400 µs−1 as a nonradiative transition rate for the 2T1g(2G) → 2Eg(2G) transition in Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N, we estimate a kinetic Ton of 50 K according to Eq. 5. It should be noted, however, that at these temperatures the emission intensity from the 2T1g(2G) level is so weak that thermometry is practically not feasible in that temperature range.

It is interesting to compare the presented thermometry approach with the commonly used thermally coupled excited, green-emitting levels 2H11/2 and 4S3/2 (ΔE21 ≈ 650 cm−1) of Er3+ in inorganic upconversion (nano-) phosphors such as β-NaYF4:Er3+, Yb3+ 71,72. The energy gap ΔE21 is similar. The main advantage of the Cr3+-based thermometer is higher brightness because of the much stronger absorption for the spin-allowed absorption bands. Additionally, the internal photoluminescence quantum yield is generally higher for narrow-line emitting Cr3+ than for the green-emitting levels of Er3+ since they are prone to additional nonradiative relaxation to lower energetic 4F9/2 levels and also emission from the thermally coupled 2H11/2 and 4S3/2 levels to other 4f11 levels than the 4I15/2 ground state lowers the brightness for the emission used for LIR thermometry. Another example of robust background-free thermometry at room temperature was demonstrated with the 6P5/2 and 6P7/2 levels of Gd3+ (again with a similar energy gap ΔE21 ≈ 600 cm−1) that can be excited by blue light in an upconversion mechanism via an energy transfer from Pr3+ in YAl3(BO3)473. This mechanism involves the excited 4f15d1 configuration of Pr3+ in the UV range. Thus, thermal coupling between the 2T1g(2G) and 2Eg(2G) states of Cr3+ in AlB4O6N or α-Al2O3 constitutes a third example of a robust luminescent Boltzmann thermometer with the highest expected precision at around room temperature.

In order to better understand the underlying reason for the differences in performance as luminescent thermometers, it is insightful to analyze the excited state dynamics of the previously mentioned emitters (see Fig. 3). In β-NaYF4:Er3+, Yb3+, the radiative decay rate of the lower energetic 4S3/2 level of the Er3+ ions is around k1 ~ 1.6 ms−1 74. The nonradiative transition between the two excited 2H11/2 and 4S3/2 levels of Er3+ has a high probability because of the strong induced electric dipolar character, which is indicated by the relatively large values of the reduced matrix elements \({{||}\left\langle {U}^{\left(k\right)}\right\rangle {||}}^{2}\left({||}{\left\langle {U}^{\left(2\right)}\right\rangle {||}}^{2}=0.0000,{{||}\left\langle {U}^{\left(4\right)}\right\rangle {||}}^{2}=0.2002,{{||}\left\langle {U}^{(6)}\right\rangle {||}}^{2}=0.0097\right)\) for the 2H11/2 ↔ 4S3/2 transition75. Consequently, the nonradiative transition is orders of magnitude faster (knr(0) ~ 1 µs−1) than radiative decay from the 4S3/2 level, resulting in low Ton for thermal coupling of around 100 K (see Fig. 3) in β-NaYF4: 2% Er3+, 18% Yb3+ 76 or YVO4: 0.1% Er3+ 77.

In contrast, the Ton of UV-emitting Gd3+ ions exploiting a resonant one-phonon transition in complex oxide-based hosts such as vanadates, phosphates, or borates to nonradiatively bridge the energy gap between the excited 6P5/2 and 6P7/2 levels (ΔE21 ≈ 600 cm−1) is found to be higher (Ton ≈ 150 K, see Fig. 3) since both the radiative decay from the lower energetic 6P7/2 level and the nonradiative transition between these two excited levels of Gd3+ have strong magnetic dipolar character and are intrinsically slow. However, while the respective nonradiative coupling strength is much smaller (knr(0)~10 ms−1)51 compared to the anticipated value for Cr3+ in AlB4O6N, the radiative decay of the corresponding 6P7/2 → 8S7/2-based emission (λem~310 nm) of Gd3+ is much faster (k1~0.3 ms−1) than for the 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F)-based emission of Cr3+ in AlB4O6N. The observed onset temperature Ton for thermalization of excited states depends on the ratio of the nonradiative absorption and radiative decay rate (see Eq. 5). In Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N, the unusually strong ligand field and high local site symmetry of the Al sites together with the very effective nonradiative coupling strength between the 2T1g(2G) and 2Eg(2G) states leads to a hitherto unrealized wide dynamic working range of a luminescent Boltzmann thermometer based on Cr3+. Moreover, the broad-band and the related higher oscillator strengths for the spin-allowed absorption transitions compared to the trivalent lanthanoid ions together with the high internal quantum yield of the 2Eg(2G)-based radiative emission ensures a very high brightness, which is key to a high statistical precision of a luminescent thermometer2,3. Thus, next to a UV-emitting luminescent Boltzmann thermometer based on Gd3+ 73 and a green-emitting Boltzmann thermometer based on Er3+ 71,72, thermal coupling between the 2T1(g)(2G) and 2E(g)(2G) states of Cr3+ in AlB4O6N or α-Al2O3 constitutes a third example (see Fig. 3) of a robust ratiometric Boltzmann thermometer with highest expected precision in the range around room temperature and offers clear advantages over the other thermometers: emission in the deep red to near-infrared range (deeper penetration depth in biological samples), higher brightness (stronger absorption) and a wider dynamic temperature range as a result of faster nonradiative relaxation between thermally coupled states.

The underlying reason for the so much stronger nonradiative coupling between the 2T1g(2G) and 2Eg(2G) states of Cr3+ compared to the coupling between the 4fn spin-orbit levels of the trivalent lanthanoid ions must be related to the lateral extension of the outer 3d orbitals compared to the shielded inner 4f orbitals and the resulting higher electron-phonon coupling strength of the former orbitals. The stronger electron-phonon coupling is also reflected in the much stronger vibronic transitions observed for 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F) emission of Cr3+ compared to that for 4fn-4fn transitions of lanthanide ions78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86. Related theoretical ideas going towards this direction were reported by Kushida and Kikuchi67. Selection rules do not appear to play a significant role here as a symmetry analysis would imply a magnetic dipolar and thus, expectedly slow nonradiative 2T1g(2G) ↔ 2Eg(2G) transition. Overall, the ratiometric thermometry concept exploiting the two narrow emission lines based on the 2T1g(2G) → 4A2g(4F) and 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F) transitions of Cr3+ in AlB4O6N together with the very high thermal quenching temperature due to the unusually strong ligand field leads to an unprecedented dynamic working range of a red-emitting transition metal-based activator.

Nonradiative crossover between the 4 T 2g(4F) and 2 E g(2G) states in Cr3+-activated AlB4O6N

In both Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N and α-Al1.993Cr0.007O3, an additional broad emission band is observed above ~300 K or 200 K, respectively, which is assigned to the 4T2g(4F) → 4A2g(4F) transition (see Fig. 4 as well as Fig. S8). Up to 850 K, the intensity of this emission band increases accompanied by a simultaneous decrease of the narrow-line 2T1g(2G), 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F)-based emission. The observation of the broad-band emission and related thermalization between the 2Eg(2G) and 4T2g(4F) states of Cr3+ is in excellent agreement with the modeled temperature dependence of the luminescence decay times with thermally averaged decay times of 2.5 ms at 873 K for Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N and 675 µs at 598 K for α-Al2O3:Cr3+ (see Fig. S15). The luminescence decay times for Cr3+ in AlB4O6N are longer because of the high symmetry (closer to inversion symmetry than for Cr3+ in ruby) and start to decrease at higher temperatures related to the stronger ligand field in Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N, which shifts the 4T2g level to higher energies compared to ruby, giving rise to a larger energy gap between the 2Eg and 4T2g states. Accordingly, the temperature-dependent LIR between the 4T2g(4F) → 4A2g(4F)- and 2T1g(2G), 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4G)-based emission bands follows a Boltzmann behavior at sufficiently high temperature, which can be derived from the analytic steady-state solution,87,88

with αa3 the feeding ratio from the pumped 4T1g(4F) = |a〉 state to the g3 = 12-fold degenerate 4T2g(4F) = |3〉 state. It is a reasonable assumption that the nonradiative relaxation from the 4T1g(4F) to the energetically close 4T2g(4F) state is much faster than to the energetically lower g1 = 4-fold degenerated 2Eg(2G) = |1〉 state (especially since the latter also involves a spin-flip) which means that αa3 ≈ 1. ΔEX1 denotes the barrier between the vibrational ground level of the 2Eg(2G) state to the crossover point X with the 4T2g(4F) potential energy curve, while ΔE3X is the respective (lower) barrier for the reverse crossover from the vibrational ground state of the 4T2g(4F) state to X.

a Temperature-dependent emission spectra of Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N between 323 K and 848 K. The integration ranges for the 4T2g(4F) → 4A2g(4F) and 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F) transition were varied due to the band-broadening and the red-shift of the emission bands by temperature, respectively. For absolute intensity spectra, see Fig. S16. b LIR R31(T) between the integrated intensities of the 4T2g(4F) → 4A2g(4F)- and 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F)-based emission bands in Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N with the least-squares fit to Eq. 7 with A → 0

Under the assumption of αa3 ≈ 1, Eq. 6 can be simplified to the more useful fitting equation

with β1,3 = knr(0)/k1,3r and ΔE31 = ΔEX1 – ΔE3X as the vertical (0–0) energy gap between the 4T2g(4F) and 2Eg(2G) state89. Since ΔE3X is only a small barrier (typically ≤ 500 cm−1), it can be estimated that A < 0.1 at temperatures above 77 K and is thus negligible for the regarded temperature range of T > 320 K (see Fig. 4, A(T = 320 K) ≈ 10−5 for ΔE3X ~ 500 cm−1). It should be noted that approximation (6) may imply an unusual increase of the 4T2g(4F)-based emission in the limit ΔE3X ≳ kBT (i.e., for very low temperatures), which is certainly not observed (see Fig. S4) and indicates that ΔE3X must be negligibly small.

Common radiative decay rate constants k3r of the 4T2g(4F) state in e.g., Cr3+-activated garnets are in the order of k3r ≈ 102 – 103 ms−1 (refs.49,60,79,80,81,82,83,90,91,92,93,94). From the temperature-dependent decay measurements (see Fig. S9), a value of k3r = αk1r = (161 ± 20) ms−1 is estimated for Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N, while the probed decay of the 4T2g(4F)-based emission at 873 K (see Fig. S15 and Eq. S4) allows an estimate of k3r = (36 ± 5) ms−1 exactly in the reported range mentioned above60,90,91,92,93,94. Additional confidence about the right order of magnitude can be gained from Herzberg’s perturbative mixing approach of electronic states93,95,96 (see Eqs. S2 and S3), which yields an estimate of k3r ≈ 60 ms−1.

With the knowledge of the radiative decay rate k3r of the 4T2g(4F) state of Cr3+ in AlB4O6N, it is possible to gain physical insight into the parameters A and B obtained from fitting Eq. (7) to the temperature-dependent LIR R31(T) (see Fig. 4). The value of C = k3r/k1r is expected to be 103 – 104, in excellent agreement with the fitted value (C = 1.88 ∙ 103). In contrast, A is dominated by the ratio between k3r and knr(0) and thus, expectedly much smaller than 1. In fact, the parameter A cannot be experimentally accurately determined given the very low relative intensity of the 4T2g(4F) → 4A2g(4F)-based emission in the range of 10-5 counts at temperatures below 320 K indicate that nonradiative relaxation from 4T2g to 2T1g and 2Eg is so much faster than radiative decay from the 4T2g level that no 4T2g emission is observed at low temperatures. Both values are, however, in the expected range. The fit of the temperature-dependent LIR to Eq. 7 (see Fig. 4b) yields an energy gap of ΔE31 = (3644 ± 52) cm−1, which agrees very well with the estimated energy gap between the 4T2g(4F) and 2Eg(2G) states from the temperature-dependent decay measurements (ΔE31 ≈ (3837 ± 103) cm−1, Fig. S9) and from the energy difference of 3728 cm−1 determined from the positions of the 2Eg and 4T2g zero-phonon lines at 20 K (see Table S3 and Figs. S4 and S5). Despite this large energy gap between the 4T2g(4F) and 2Eg(2G) states, the observed relative integrated intensity of the 4T2g(4F) → 4A2g(4F)-based emission (5.38 ∙ 10−4) at 320 K matches the expected value according to the fit to Eq. 7 in the limit A → 0 (R31(320 K) = 5.51 ∙ 10−4), which indicates that even at that comparatively low temperature, there is already thermalization between the 4T2g(4F) and 2Eg(2G) states. This finding indicates a very high intrinsic nonradiative coupling rate constant knr(0). Again, pioneering transient absorption data reported for other Cr3+-activated compounds are insightful here and nonradiative rates for the 4T2g(4F) → 2Eg(2G) transition of the order of 101 – 102 ns−1 were reported (knr(0) = 37 ns−1 for alexandrite and knr(0) = 142 ns−1 for ruby)60,91,97. These values are about six orders of magnitude faster than the 4T2g(4F) → 4A2g(4F) radiative decay rate, which explains why emission cannot be observed at low temperatures, also considering that the 4T2g(4F) → 4A2g(4F)-based emission gives rise to a broad-band compared to the sharp 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F)-based emission.

The huge energy gap of ΔE31 of around 3700 cm−1 might imply a very sensitive luminescence thermometer at high temperatures (see Figs. S12 and S13). However, the relatively low signal-to-noise of the broad-band 4T2g(4F) → 4A2g(4F)-based emission and the significant spectral overlap with the narrow-line 2Eg(2G) → 4A2g(4F)-based emission pose severe limitations to this crossover-based thermometry approach compared to the alternative way of classic ratiometric Boltzmann thermometry with the two narrow 2T1g(2G)- and 2Eg(2G)-related emission lines demonstrated above. The overall temperature-dependent color change of the luminescence of Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N can be represented in a CIE diagram (see Fig. S17).

Discussion

A new accurate, wide temperature range, robust, and bright ratiometric luminescence thermometer with Cr3+ in an exceptionally strong ligand field is demonstrated. The narrow-line red-emitting phosphor Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N with 2Eg(2G) and 2T1g(2G) states separated by around 600 cm−1 can be exploited for high-precision Boltzmann thermometry based on the temperature-dependent intensity ratio of the narrow emission lines from the two thermally coupled levels.

Luminescence studies at temperatures below room temperature reveal fundamental insights into the relevance of nonradiative coupling between excited states. The nonradiative transition rate between the 2Eg(2G) and 2T1g(2G) states of Cr3+ is very high (estimated in the order of 0.1 – 1 ns−1) and is based on a one-phonon transition between potential energy curves with similar equilibrium geometries. This value is much higher than for nonradiative coupling for similar energy gaps between the shielded inner 4fn spin-orbit levels of the trivalent lanthanoid ions and can be understood by the larger spatial extension of the outer 3d orbitals. Together with the unique high thermal quenching temperature T1/2 = 550 K (again explained by the high energy position of the 4T2g state for Cr3+ in AlB4O6N), the narrow emission lines of Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N offer an unprecedented ultra-wide dynamic working range between <77 K to >850 K as a simple, robust, and precise ratiometric luminescent thermometer emitting in the deep red range. Compared to workhorse lanthanoid ion thermometers based on, e.g., Er3+, the new Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N material offers a wider temperature range and higher brightness.

Above 340 K, also broad-band emission based on the 4T2g(4F) → 4A2g(4F) can be detected. Given the wide energy gap of ~3700 cm−1, such a low onset temperature Ton implies a very high intrinsic nonradiative transition rate (in the order of 10 ns−1). The large energy gap implies a high relative sensitivity (Sr(500 K) > 2% K−1) at elevated temperatures, but the relatively low signal-to-noise ratio of the broad-band 4T2g(4F) → 4A2g(4F)-based emission as well as the necessity for deconvolution of the emission spectra, limits its application for luminescent thermometry at high temperatures. In conclusion, Al0.993Cr0.007B4O6N is a bright LIR thermometer with a hitherto record-breaking dynamic working range emitting in the deep red range. It will be challenging (but rewarding) to find other Cr3+-doped materials with even stronger ligand fields to outperform this new luminescent thermometer.

References

Dramićanin, M. D. Trends in luminescence thermometry. J. Appl. Phys. 128, 040902. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0014825 (2020).

Brites, C. D. S. et al. Spotlight on luminescence thermometry: basics, challenges, and cutting-edge applications. Adv. Mater. 35, 2302749. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202302749 (2023).

van Swieten, T. P., Meijerink, A. & Rabouw, F. T. Impact of noise and background on measurement uncertainties in luminescence thermometry. ACS Photonics 9, 1366–1374, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.2c00039 (2022).

Zhou, J. et al. Advances and challenges for fluorescence nanothermometry. Nat. Methods 17, 967–980, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-0957-y (2020).

Pickel, A. D. et al. Apparent self-heating of individual upconverting nanoparticle thermometers. Nat. Commun. 9, 4907. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07361-0 (2018).

Geitenbeek, R. G. et al. Luminescence thermometry for in situ temperature measurements in microfluidic devices. Lab Chip 19, 1236–1246, https://doi.org/10.1039/c8lc01292j (2019).

Okabe, K. & Uchiyama, S. Intracellular thermometry uncovers spontaneous thermogenesis and associated thermal signaling. Commun. Biol. 4, 1377, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02908-2 (2021).

Okabe, K. et al. Intracellular temperature mapping with a fluorescent polymeric thermometer and fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. Nat. Commun. 3, 705. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1714 (2012).

Lu, K. et al. Intracellular heat transfer and thermal property revealed by kilohertz temperature imaging with a genetically encoded nanothermometer. Nano Lett. 22, 5698–5707, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c00608 (2022).

Filho, R. S. R. et al. Thermal diffusivity of nanofluids: a simplified temperature oscillation approach. Phys. Fluids 37, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0252044 (2025).

Maturi, F. E. et al. Deciphering density fluctuations in the hydration Water of brownian nanoparticles via upconversion thermometry. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 2606–2615, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.4c00044 (2024).

Gu, Y. et al. Local temperature increments and induced cell death in intracellular magnetic hyperthermia. ACS Nano 17, 6822–6832, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c00388 (2023).

Dramićanin, M. In Luminescence Thermometry: Methods Materials and Applications Woodhead Publishing Series in Electronic and Optical Materials (ed Dramićanin, M.) Vol. 6, 113-157 (Woodhead Publishing, 2018).

Suta, M. & Meijerink, A. A theoretical framework for ratiometric single ion luminescent thermometers—thermodynamic and kinetic guidelines for optimized performance. Adv. Theory Simul. 3, 2000176. https://doi.org/10.1002/adts.202000176 (2020).

Brites, C. D. S., Balabhadra, S. & Carlos, L. D. Lanthanide-based thermometers: at the cutting-edge of luminescence thermometry. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7, 1801239. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201801239 (2019).

Fu, L., Wu, Y. S. & Fu, T. R. Determination of absorption cross-section of RE3+ in upconversion powder materials: application to β-NaYF4: Er3+. J. Lumin. 245, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2022.118758 (2022).

von Seggern, H. et al. Physical model of photostimulated luminescence of x-ray irradiated BaFBr:Eu2+. J. Appl. Phys. 64, 1405–1412, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.341838 (1988).

Ratzker, B. et al. Optical properties of transparent polycrystalline ruby (Cr:Al2O3) fabricated by high-pressure spark plasma sintering. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 41, 3520–3526, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2021.01.022 (2021).

Cronemeyer, D. C. Optical absorption characteristics of pink ruby. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 56, 1703–1705, https://doi.org/10.1364/josa.56.001703 (1966).

Kenyon, P. et al. Tunable infrared solid-state laser materials based on Cr3+ in low ligand fields. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 18, 1189–1197, https://doi.org/10.1109/jqe.1982.1071692 (1982).

Struve, B. et al. Tunable room-temperature cw laser action in Cr3+:GdScGa-Garnet. Appl. Phys. B Photophys. Laser Chem. 30, 117–120, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00695465 (1983).

Elzbieciak-Piecka, K. & Marciniak, L. Optical heating and luminescence thermometry combined in a Cr3+-doped YAl3(BO3)4. Sci. Rep. 12, 16364. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20821-4 (2022).

Marciniak, L. et al. Luminescence thermometry with transition metal ions. A review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 469, 214671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214671 (2022).

Jaśkielewicz, J. et al. The role of host material in the design of ratiometric optical density meters based on Cr3+ luminescence in Y3Al5-xGaxO12:Cr3+. Adv. Opt. Mater. 13, 2402039. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202402039 (2025).

de Wit, J. W. et al. Increasing the power: absorption bleach, thermal quenching, and Auger quenching of the red-emitting phosphor K2TiF6:Mn4+. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11, 2202974. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202202974 (2023).

Back, M. et al. Pushing the limit of Boltzmann distribution in Cr3+-doped CaHfO3 for cryogenic thermometry. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 38325–38332, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c08965 (2020).

Widmann, I. et al. Real competitors to ruby: the triel oxonitridoborates AlB4O6N, Al0.97Cr0.03B4O6N, and Al0.83Cr0.17B4O6N. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2400054. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202400054 (2024).

Geitenbeek, R. G., de Wijn, H. W. & Meijerink, A. Non-Boltzmann luminescence in NaYF4:Eu3+: implications for luminescence thermometry. Phys. Rev. Appl. 10, 064006. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.10.064006 (2018).

Riseberg, L. A. & Moos, H. W. Multiphonon orbit-lattice relaxation of excited states of rare-earth ions in crystals. Phys. Rev. 174, 429–438, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.174.429 (1968).

Ermeneux, F. S. et al. Multiphonon relaxation in YVO4 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 61, 3915–3921, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.61.3915 (2000).

Riseberg, L. A. & Moos, H. W. Multiphonon orbit-lattice relaxation in LaBr3, LaCl3, and LaF3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 19, 1423–1426, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.19.1423 (1967).

Englman, R. & Jortner, J. The energy gap law for radiationless transitions in large molecules. Mol. Phys. 18, 145–164, https://doi.org/10.1080/00268977000100171 (1970).

Strek, W. & Ballhausen, C. J. The role of internal ligand modes in promoting radiationless transitions in metal complexes. Mol. Phys. 36, 1321–1327, https://doi.org/10.1080/00268977800102371 (1978).

van Dijk, J. M. F. & Schuurmans, M. F. H. On the nonradiative and radiative decay rates and a modified exponential energy gap law for 4f–4f transitions in rare-earth ions. J. Chem. Phys. 78, 5317–5323, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.445485 (1983).

van Dijk, J. M. F. Derivation of the relation between non-radiative and radiative decay rates in rare-earth ions with comparison to experimental energy gap, parameters and the consequences for non-radiative selection rules. J. Lumin. 24-25, 705–708, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2313(81)90074-0 (1981).

Orlovskii, Y. V. et al. Nonlinear mechanism of multiphonon relaxation of the energy of electronic excitation in optical crystals doped with rare-earth ions. Opt. Mater. 4, 583–595, https://doi.org/10.1016/0925-3467(95)00012-7 (1995).

Pukhov, K. K. & Sakun, V. P. Theory of nonradiative multiphonon transitions in impurity centers with extremely weak electron-phonon coupling. Phys. Status Solidi (B) 95, 391–402, https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.2220950209 (1979).

Pukhov, K. K., Basiev, T. T. & Orlovskii, Y. V. Radiative properties of lanthanide and transition metal ions in nanocrystals. Opt. Spectrosc. 111, 386–392, https://doi.org/10.1134/s0030400x11090219 (2011).

Grinberg, M. et al. The influence of substitutional disorder on non-radiative transitions in Cr3+-doped gallogermanate crystals. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 9, 2815–2829, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/9/13/021 (1997).

Ermolaev, V. L. & Sveshnikova, E. B. Non-radiative transitions as Förster’s energy transfer to solvent vibrations. J. Lumin. 20, 387–395, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2313(79)90009-7 (1979).

van Swieten, T. P. et al. Extending the dynamic temperature range of Boltzmann thermometers. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 343, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-022-01028-8 (2022).

Wang, Y., Ren, J. & Shuai, Z. Minimizing non-radiative decay in molecular aggregates through control of excitonic coupling. Nat. Commun. 14, 5056. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40716-w (2023).

Liu, S. et al. High-efficiency organic solar cells with low non-radiative recombination loss and low energetic disorder. Nat. Photonics 14, 300–305, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-019-0573-5 (2020).

Kim, T. et al. Molecular design leveraging non-covalent interactions for efficient light-emitting organic small molecules. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2412267. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202412267 (2025).

El-Sayed, M. A. Triplet state. Its radiative and nonradiative properties. Acc. Chem. Res. 1, 8–16, https://doi.org/10.1021/ar50001a002 (1968).

Pauling, L., Klug, H. P. & Winchell, A. N. The crystal structure of swedenborgite, NaBe4SbO7. Am. Min. 20, 492–501 (1935).

Huppertz, H. & Schnick, W. BaYbSi4N7– unexpected structural possibilities in nitridosilicates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 35, 1983–1984, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.199619831 (1996).

Widmann, I., Dubrovinsky, L. & Huppertz, H. Extended investigations on the pressure stability of AlB4O6N:Cr3+. Z. Naturforsch. B 80, 277–283, https://doi.org/10.1515/znb-2025-0024 (2025).

Fuchs, B. et al. The first high-pressure chromium oxonitridoborate CrB4O6N—an unexpected link to nitridosilicate chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 21801–21806, https://doi.org/10.1002/ANIE.202110582 (2021).

McCumber, D. E. & Sturge, M. D. Linewidth and temperature shift of the R lines in ruby. J. Appl. Phys. 34, 1682–1684, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1702657 (1963).

Netzsch, P. et al. Beyond the energy gap law: the influence of selection rules and host compound effects on nonradiative transition rates in Boltzmann thermometers. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2200059. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202200059 (2022).

Otto, S. et al. Thermo-chromium: a contactless optical molecular thermometer. Chem. – Eur. J. 23, 12131–12135, https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201701726 (2017).

Back, M. et al. Boltzmann thermometry in Cr3+-doped Ga2O3 polymorphs: the structure matters!. Adv. Opt. Mater. 9, 2100033. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202100033 (2021).

Back, M. et al. Effective ratiometric luminescent thermal sensor by Cr3+-doped mullite Bi2Al4O9 with robust and reliable performances. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8, 2000124. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202000124 (2020).

Back, M. et al. Ratiometric optical thermometer based on dual near-infrared emission in Cr3+-doped bismuth-based gallate host. Chem. Mater. 28, 8347–8356, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b03625 (2016).

Back, M. et al. Revisiting Cr3+-doped Bi2Ga4O9 spectroscopy: crystal field effect and optical thermometric behavior of near-infrared-emitting singly-activated phosphors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 41512–41524, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b15607 (2018).

Ristić, Z. et al. Triple-temperature readout in luminescence thermometry with Cr3+-doped Mg2SiO4 operating from cryogenic to physiologically relevant temperatures. Meas. Sci. Technol. 32, 054004, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6501/abdc9a (2021).

Mykhaylyk, V. B. et al. Multimodal non-contact luminescence thermometry with Cr-doped oxides. Sensors 20, 5259, https://doi.org/10.3390/s20185259 (2020).

Hu, Y. L. et al. Ruby-based decay-time thermometry: effect of probe size on extended measurement range (77–800 K). Sens. Actuators, A: Phys. 63, 85–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0924-4247(97)01523-9 (1997).

Zhang, Z. Y., Grattan, K. T. V. & Palmer, A. W. Temperature dependences of fluorescence lifetimes in Cr3+-doped insulating crystals. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter 48, 7772–7778, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.48.7772 (1993).

Sekulić, M. et al. Li1.8Na0.2TiO3:Mn4+: the highly sensitive probe for the low-temperature lifetime-based luminescence thermometry. Opt. Commun. 452, 342–346, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2019.07.056 (2019).

Dramićanin, M. D. et al. Li2TiO3:Mn4+ deep-red phosphor for the lifetime-based luminescence thermometry. ChemistrySelect 4, 7067–7075, https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.201901590 (2019).

Uchiyama, H. et al. Fiber-optic thermometer using Cr-doped YAlO3 sensor head. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 74, 3883–3885, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1589582 (2003).

Lesniewski, T. et al. Temperature effect on the emission spectra of narrow band Mn4+ phosphors for application in LEDs. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 32505–32513, https://doi.org/10.1039/c7cp06548e (2017).

Liu, S. Q. et al. Distinguishing between thermal coupling and spin interaction for Cr3+ NIR luminescence through temperature-dependent lifetime analysis. Laser Photon. Rev., https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202500568 (2025).

Champagnon, B. et al. 2T1 pumping of the R lines in ruby. Phys. Lett. A 93, 241–244, https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9601(83)90807-1 (1983).

Kushida, T. & Kikuchi, M. R. R’ and B absorption linewidths and phonon-induced relaxations in ruby. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 23, 1333–1348, https://doi.org/10.1143/jpsj.23.1333 (1967).

El-Sayed, M. A. Spin-orbit coupling and the radiationless processes in nitrogen heterocyclics. J. Chem. Phys. 38, 2834–2838, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1733610 (1963).

Marian, C. M. Understanding and controlling intersystem crossing in molecules. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 72, 617–640, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physchem-061020-053433 (2021).

Burshtein, Z. Radiative, nonradiative, and mixed-decay transitions of rare-earth ions in dielectric media. Opt. Eng. 49, 091005 (2010).

Martins, J. C. et al. Primary luminescent nanothermometers for temperature measurements reliability assessment. Adv. Photonics Res. 2, 2000169. https://doi.org/10.1002/adpr.202000169 (2021).

Maciejewska, K. et al. Correlation between the covalency and the thermometric properties of Yb3+/Er3+ codoped nanocrystalline orthophosphates. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 2659–2665, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c09532 (2021).

Yu, D. C. et al. One ion to catch them all: Targeted high-precision Boltzmann thermometry over a wide temperature range with Gd3+. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 236, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-021-00677-5 (2021).

Rabouw, F. T. et al. Quenching pathways in NaYF4:Er3+,Yb3+ upconversion nanocrystals. ACS Nano 12, 4812–4823, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.8b01545 (2018).

Carnall, W. T., Crosswhite, H. & Crosswhite, H. M. Energy level structure and transition probabilities in the spectra of the trivalent lanthanides in LaF₃ (Argonne National Lab., 1977).

Suta, M. What makes β-NaYF4:Er3+,Yb3+ such a successful luminescent thermometer? Nanoscale 17, 7091–7099, https://doi.org/10.1039/d4nr04392h (2025).

Capobianco, J. A. et al. Optical spectroscopy, fluorescence dynamics and crystal-field analysis of Er3+ in YVO4. Chem. Phys. 214, 329–340, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0301-0104(96)00318-7 (1997).

Hellwege, K. H. Über die Fluoreszenz und die Kopplung zwischen Elektronentermen und Kristallgitter bei den wasserhaltigen Salzen der Seltenen Erden. Ann. Phys. 432, 529–542, https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.19414320705 (1941).

Krupke, W. F. Optical absorption and fluorescence intensities in several rare-earth-doped Y2O3 and LaF3 single crystals. Phys. Rev. 145, 325–337, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.145.325 (1966).

De Mello Donega, C., Meijerink, A. & Blasse, G. Vibronic transition probabilities in the excitation spectra of the Pr3+ ion. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 4, 8889–8902, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/4/45/021 (1992).

Blasse, G. Vibronic transitions in rare earth spectroscopy. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 11, 71–100, https://doi.org/10.1080/01442359209353266 (1992).

Sytsma, J. & Blasse, G. Vibronic transitions in the excitation spectra of the Gd3+ emission. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 53, 561–563, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3697(92)90101-i (1992).

Blasse, G. The intensity of vibronic transitions in the spectra of the trivalent europium ion. Inorg. Chim. Acta 167, 33–37, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-1693(00)83935-3 (1990).

Ellens, A. et al. The variation of the electron-phonon coupling strength through the trivalent lanthanide ion series. J. Lumin. 66-67, 240–243, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2313(95)00145-x (1995).

Ellens, A. et al. Spectral-line-broadening study of the trivalent lanthanide-ion series.I. Line broadening as a probe of the electron-phonon coupling strength. Phys. Rev. B 55, 173–179, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.55.173 (1997).

Ellens, A. et al. Spectral-line-broadening study of the trivalent lanthanide-ion series.II. The variation of the electron-phonon coupling strength through the series. Phys. Rev. B 55, 180–186, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.55.180 (1997).

Bendel, B. & Suta, M. How to calibrate luminescent crossover thermometers: a note on “quasi”-Boltzmann systems. J. Mater. Chem. C. 10, 13805–13814, https://doi.org/10.1039/d2tc01152b (2022).

Yamaga, M., Henderson, B. & O’Donnell, K. P. Tunnelling between excited 4T2 and 2E states of Cr3+ ions with small energy separation-the case of GSGG. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 1, 9175–9182, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/1/46/010 (1989).

Suta, M. Performance of Boltzmann and crossover single-emitter luminescent thermometers and their recommended operation modes. Opt. Mater.: X 16, 100195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omx.2022.100195 (2022).

Chen, D. et al. Cr3+-doped gallium-based transparent bulk glass ceramics for optical temperature sensing. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 35, 4211–4216, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2015.08.005 (2015).

Gayen, S. K. et al. Picosecond excite-and-probe absorption measurement of the 4T2 state nonradiative lifetime in ruby. Appl. Phys. Lett. 47, 455–457, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.96145 (1985).

Sharma, S. et al. Temperature sensing using a Cr:ZnGa2O4 new phosphor. Proceedings of SPIE 9749, Oxide-Based Materials and Devices VII. San Francisco: SPIE, 2016, 229-235

Struve, B. & Huber, G. The effect of the crystal field strength on the optical spectra of Cr3+ in gallium garnet laser crystals. Appl. Phys. B Photophys. Laser Chem. 36, 195–201, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00704574 (1985).

Walling, J. et al. Tunable alexandrite lasers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 16, 1302–1315, https://doi.org/10.1109/jqe.1980.1070430 (1980).

Wojtowicz, A. J., Grinberg, M. & Lempicki, A. The coupling of 4T2 and 2E states of the Cr3+ ion in solid state materials. J. Lumin. 50, 231–242, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2313(91)90047-y (1991).

Herzberg, G. Molecular Spectra and Molecular Structure. Volume I: Spectra of diatomic molecules. 2nd edn. New York: van Nostrand, 280-298 https://archive.org/details/molecularspectra0001herz (1963).

Gayen, S. K. et al. Nonradiative transition dynamics in alexandrite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 49, 437–439, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.97135 (1986).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Michael Seidl for the single-crystal diffraction measurement. M.S. is grateful for a materials cost allowance of the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie e.V. and financial support by the “Young College” of the North-Rhine Westphalian Academy of Science, Humanities, and the Arts. Generous funding by the German National Science Foundation (DFG, SU 1156/5-1, project no. 554302036) and the Strategic Research Fund of the HHU Düsseldorf is also gratefully acknowledged. I.W. thanks the Vice Rectorate for Research of Innsbruck for a PhD scholarship.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kinik, G., Widmann, I., Bendel, B. et al. Ratiometric Boltzmann thermometry with Cr3+ in strong ligand fields: Efficient nonradiative coupling for record dynamic working ranges. Light Sci Appl 14, 388 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-025-02082-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-025-02082-8