Abstract

Photonic crystal fibers have significantly advanced optoelectronics, enabling a wide range of applications from communications to sensing and imaging. A long-standing challenge in these areas has been achieving pure single-polarization single-mode (SPSM) waveguiding for high-quality information transmission. Traditional approaches, however, inevitably introduce polarization dispersion and operate within a narrow bandwidth. Recent advancements in topological phases offer a promising opportunity to access previously unattainable mode properties, though experimental demonstrations remain scarce. In this work, we present the first experimental observation of a topologically protected photonic Dirac vortex mode that supports pure SPSM propagation in terahertz fibers. Utilizing terahertz scanning near-field microscopic spectroscopy, we map the temporal, spectral, and spatial characteristics of the topological mode, providing insights into its mode profile, dispersion, effective area, and numerical aperture. We demonstrate a single linearly dispersed Dirac vortex mode with a single vortex polarization and a broad 85.7% fractional bandwidth. This breakthrough fills a crucial gap in the development of SPSM fibers and introduces a comprehensive methodology for exploring mode properties, paving the way for advancements in terahertz optoelectronics, topological photonics, and specialty optical fibers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topologically protected photonic Dirac vortex modes (DVMs) reside in the mid-gap region and exhibit full spectral isolation from bulk states throughout the Brillouin zone in topological photonic vortex cavities with Kekulé phase modulation and disclination cavities1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. These photonic DVMs are fundamentally linked to the mid-gap Jackiw-Rossi zero-energy states12,13, which solve the 2D Dirac equation with a topologically protected vortical mass term. Recent implementations of photonic DVMs in topological vortex cavities have enabled lasing functionality14,15,16,17. Significantly, introducing a nonzero out-of-plane wavevector component (kz ≠ 0) triggers a transformation of DVMs from localized to propagating modes (Fig. 1, see Supplementary Section 15), a phenomenon theoretically predicted in photonic crystal fibers (PCFs) that maintain single-polarization single-mode (SPSM) operation18.

SPSM characteristic proves particularly advantageous in communication systems by effectively suppressing mode and polarization-dependent crosstalk. PCF-based SPSM implementations have demonstrated superior performance owing to their unique structure, guiding mechanism, and tunable optical properties19,20,21,22,23. High birefringence remains a prevalent strategy for realizing SPSM fibers, typically achieved either by engineering fundamental mode cutoff frequencies or suppressing undesired modes through selective attenuation. Established implementations exploit structural asymmetry24,25, index matching coupling technique26, anisotropic materials27,28, and anti-resonant fiber architectures29,30,31 to induce such birefringence. These methods, however, inherently sustain two non-degenerate polarization states, leading to residual modal coupling and polarization-mode dispersion that degrade signal integrity through pulse broadening and polarization crosstalk. Furthermore, the reliance on cutoff-frequency-based mode selection fundamentally restricts the operational bandwidth of SPSM fibers.

In next-generation wireless networks, terahertz (THz) waves emerge as a cornerstone technology offering unparalleled advantages in transmission capacity, sub-millisecond latency, and massive device connectivity. Nevertheless, free-space THz propagation faces inherent limitations involving pronounced atmospheric attenuation, which severely constrains effective communication distances. Significant progress has been made in utilizing traditional photonic crystal line defect waveguides32 and topological valley-Hall photonic crystals33,34,35 for THz wave guided transmission. Besides, waveguided THz transmission through specially designed fibers presents a viable strategy to overcome these challenges, and precise control over modal characteristics and polarization states with SPSM properties is essential for nondestructive imaging, sensing, and communications.

In this work, we experimentally demonstrate the pure single-polarization, single-mode characteristics of DVMs in PCFs using time-resolved terahertz scanning near-field microscopic spectroscopy (THz-SNMS). Unlike conventional time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS), THz-SNMS enables direct spatial mapping of mode profiles while integrating spectrally resolved characterization capabilities36. By incorporating the short-time Fourier transform (STFT) algorithm, we reconstruct the mode dispersion, propagation dynamics, effective area, and numerical aperture, collectively revealing a linearly dispersed DVM with an extensive 85.7% fractional bandwidth. Additionally, we estimate the low confinement loss of the DVM, an intrinsic property at the Γ point in the absence of an in-plane wavevector, where all bulk states undergo exponential decay into free space. The single-vortex polarization state is further confirmed through the observed electric field vector distributions.

Results

Theoretical realization

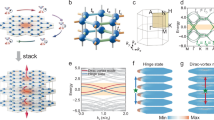

A photonic crystal with a hexagonal superlattice structure is considered, consisting of air holes drilled into a host medium, where the period is d and the radius of identical air holes is R0 = 0.46 d (see Supplementary Section 13). A quadra-degenerate Dirac point arises due to in-plane inversion symmetry and band folding at Γ point in the Brillouin zone (inset in Fig. 2a at kzd/2π = 2, see Supplementary Section 1). Projection of the two-dimensional band diagram at varied propagation constants (kz) assembles a nodal line with a collection of Dirac points. The nodal line can be transformed into a complete bandgap by applying a Kekulé superlattice modulation, where the radii of the air holes comply with\(R={R}_{0}+\varDelta R\,\cos ({{\bf{K}}}_{\mathrm{int}}\cdot {{\bf{r}}}_{0}+\theta )\). Here, ΔR and θ represent the Kekulé modulation amplitude and phase, respectively. \({{\bf{K}}}_{\mathrm{int}}=K-K^{\prime} =(8\pi /3d,0)\) implies the inter-valley coupling between K and \(K^{\prime}\) valleys, and r0 is the coordinate position relative to the lattice center. At \(\theta =\pi\), the nodal-line-gapped band structure is shown in Fig. 2b, and a complete bandgap opens, as shown in the inset.

a Projected band structure of the primitive superlattice uniformly extended in the out-plane direction at different propagation constants. The side length d is 1.82 mm, and the nodal line, marked by the black solid line, consists of Dirac points in the inset 2D band structures. b Projected band structure of the Kekulé modulation superlattice with ΔR = 0.02 d and θ = π. The nodal line is lifted, forming a complete bandgap due to broken inversion symmetry. The blue dashed line represents the light line. Inset: lattice structures and in-plane band structures at kzd/2π = 2. c 2π vortex bandgap obtained by modulating θ at kzd/2π = 2. The rainbow color represents the modulation phase. d Modulation of air-hole radii in the photonic structure, varying from R0 − ΔR to R0 + ΔR, and R0 = 0.46 d and ΔR = 0.02 d. e The band structure of the PCF near the bandgap where DVM exists. f Mode profiles of the normalized x-polarized electric fields for DVM

Interestingly, the bandgap acquires a 2π vortex through continuous tuning of the phase θ, as illustrated in Fig. 2c at kzd/2π = 2. A topological phase transition occurs at \(\theta =\pi\), shifting the system from a topologically nontrivial to a trivial state (see Supplementary Section 1). To induce this transition, we apply a vortex Kekulé phase modulation by introducing a position-dependent air hole radius distribution (Fig. 2d)

where \({\bf{r}}(x,y)\) denotes the position of the hole center, \(\theta ({\bf{r}})=w{\tan }^{-1}(y/x)\) is a position-dependent modulation phase with winding number w = +1, and r0 is a w-dependent core center conserving a C3 symmetry (see Supplementary Section 2 and Section 21). As a result of the topological phase transition, a topologically protected defect mode, identified as the DVM in the PCF, emerges (see Supplementary Section 17). This mode is spectrally localized within the bandgap and spatially confined at the core, as shown in Fig. 2e, f. Additionally, the field remains localized around the fiber center along the propagating direction (see Supplementary Section 14). At the edge of the bandgap, local-defect modes appear as a result of noncontinuous variation of geometric parameters (grey in Fig. 2e, see Supplementary Section 3), which will not exert impact on the DVM.

Experimental observation of DVM

The properties of the DVM are experimentally investigated by fabricating a PCF using high-temperature resin with a refractive index 1.631 + i0.009 in the THz regime via 3D printing (see Methods). The cross-sectional structure, shown in Fig. 3a, features air holes arranged according to the Kekulé modulation. The spatial profile of the DVM is characterized using THz-SNMS (see Methods), wherein near-field information is captured by a THz microprobe with spatial (10 μm) and spectral (0.1–1.5 THz) resolution across the fiber cross-section. Orthogonal scanning paths are defined along AA and BB as illustrated in Fig. 3a.

a Microscopic images of the 3D-printing PCF cross-section. The coordinate system is defined based on symmetry with the origin at the center of the PCF. Scanning paths along AA and BB are illustrated. b Measured time-domain x-polarized electric field distribution along path AA. c Experimentally reconstructed band structure of the DVM with a corresponding fitting line. The linear band structure exhibits excellent agreement with simulation results. Inset: temporal-spectral distributions obtained by performing STFT at the origin along the dashed path in (b). d Temporal-spatial distributions at 0.3 THz along path AA. The right panel shows the spatial electric field distribution at tw = −0.53 ps, with the dashed line indicating the position where Ex drops to e-1 of its maximum value. e Spatial distributions of the DVM at 0.3 THz

Figure 3b presents the directly measured x-polarized time-domain signals along path AA, excited by a focused THz pulse from the opposite fiber end. The results reveal strong energy confinement around the core. To further analyze the spatial, spectral, and temporal characteristics, near-field distributions are reconstructed using the STFT, where a sliding time window decomposes the temporal signal into a two-dimensional time-frequency representation (see Supplementary Section 4). The inset of Fig. 3c illustrates the spectral dynamics, revealing a series of propagating dispersion relations for the DVM derived from STFT analysis of the time-domain distributions. The phase evolution of the dispersion appears as a series of striations, resembling the propagation of a dynamic band structure. The dispersion relation of the DVM is indirectly determined by analyzing the dynamic phase evolution of its frequency-dependent modal components (see Supplementary Section 5). As evidenced in Fig. 3c, the experimentally reconstructed band structure closely agrees with numerical results. Additionally, the phase velocity exhibits a consistent trend between experimental observations and theoretical predictions, where higher (lower) frequencies correspond to slower (faster) phase velocities (see Supplementary Section 6).

Temporal-spatial distributions reveal the dynamic evolution of the DVM as shown in Fig. 3d (at 0.3 THz as an example, see Supplementary Section 5). The mode is tightly confined around the origin, with a decay length of ~1 mm, as observed from the electric field along path AA at tw = −0.53 ps (Fig. 3d). By incorporating field distributions along path BB, complete 2D mode patterns are reconstructed (Fig. 3e at 0.3 THz, and see Supplementary Sections 7 and 8). The experimentally observed mode patterns closely match theoretical predictions, with only a slight expansion in the measured distribution, which can be attributed to the half-wavelength propagating divergence between the PCF cross-section and the microprobe during measurements.

Performance characterization

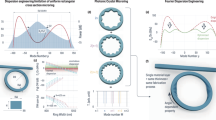

The DVM dispersion is extracted from the measured temporal-spectral distributions, exhibiting an exceptionally linear relationship akin to the light line, with a group velocity of 0.5848c. This dispersion is characterized by directly measuring the time delay of THz pulses propagating through both air and the PCF over an identical distance of 1 cm. During measurements, the microprobe is precisely positioned at the mode maximum. As shown in Fig. 4a, the group delay of pulse peaks is determined to be 23.5 ps, aligning well with the estimation based on group velocity (Fig. 4b). The overall pulse shape remains preserved due to the linear dispersion, with slight broadening attributed to the narrower bandwidth of the DVM compared to that of the incident THz pulse.

a The group delay of the DVM is determined by measuring the time delay between pulses propagating through an equal distance (1 cm) in air and the PCF. b DVM dispersion extracted from the data in Fig. 3c, exhibiting a perfectly linear dispersion and a group velocity of 0.5848c as compared with the light line in free space. c Effective area for the mode confinement and numerical aperture. d Total loss, material loss, and confinement loss

The spatial confinement of the DVM is characterized by its effective area (Aeff). The effective mode area is calculated from the electric field distribution as

where the integral is taken over the PCF cross-section. As shown in Fig. 4c, the effective mode area rapidly decreases to 2.7 mm2 within the DVM band from 0.3 to 0.5 THz. This value is two orders of magnitude smaller than state-of-the-art PCFs37,38,39,40,41, occupying only 0.0537% of the total cross-sectional area (Table 1). Such extreme confinement facilitates the dense integration of functional components in chip-scale THz photonic systems. The strong mode confinement also results in a large numerical aperture (NA), estimated using the relation42

At 0.3 THz, the NA is approximately 0.32 as shown in Fig. 4c, which falls within the conventional range for THz fibers (NA: 0.2–0.5)43,44,45.

In terms of the total losses (αtot), we separately evaluate the material loss (αmat) and the confinement loss (αcon = αtot − αmat). The total loss is determined using the cutback measurement technique, in which transmission signals are measured from two PCFs of different lengths. The difference in transmission accounts for the total losses induced by length variation while excluding coupling attenuation (see Supplementary Sections 9 and 18). The frequency-dependent total losses of the DVM are presented in Fig. 4d. By utilizing the imaginary part of the effective refractive index of the material (around 0.004 at 0.3 THz, see Supplementary Section 10), the confinement loss of the DVM is extracted, revealing a minimum value of 0.198 cm−1 at 0.225 THz. The overall confinement loss remains around 0.275 cm−1 in the 0.2–0.375 THz range. Beyond 0.4 THz, significant fluctuations appear in the confinement loss values, which are attributed to the degraded signal-to-noise ratio of the DVM under high-frequency excitation (see Supplementary Section 9).

Vortex polarization

Another key characteristic of the DVM is its vector electric field distribution, which exhibits a vortex-like polarization governed by the Kekulé modulation of the vortex phase, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. To experimentally verify this vector polarization, we analyze the mode pattern under excitation by a linearly polarized incident wave with varying orientations. A dipole-like mode pattern emerges, with the nodal line consistently aligning parallel to the incident linear polarization vector, as confirmed by simulations in Fig. 5b1–f1. In THz-SNMS experiments, the same field patterns are observed (Fig. 5b2–f2), with the nodal lines rotating in accordance with the orientation of the incident linear polarization vector at 0.3 THz. This direct experimental evidence unambiguously confirms the vortex polarization property of the DVM and polarization alignment-free (see Supplementary Section 20) SPSM operation for the THz PCF.

a Simulated electric field vector distribution of the DVM mode, indicating a vortex property. b1–f1 Simulated mode patterns excited by linear polarization at varied angles at 0.3 THz within the region marked by the square in (a). b2–f2 Corresponding experimental demonstration of the DVM mode patterns

Discussion

DVMs exhibit core photonic properties essential for fiber applications: pure SPSM operation, broad bandwidth, linear dispersion, and small mode volume. We fabricated Kekulé-phase-modulated photonic crystal fibers via 3D printing, experimentally demonstrating 85.7% bandwidth SPSM operation with a mode area occupying merely 0.0537% of the fiber cross-section, as characterized by time-resolved THz-SNMS. In the current design, mode propagation is primarily limited by material absorption in the polymer components. This limitation could be overcome by employing low-loss THz materials, such as methyl pentene copolymer (TPX) and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), which exhibit near-zero absorption below 0.5 THz, in combination with high-precision femtosecond laser direct writing techniques46,47. Theoretically, materials with zero absorption coefficients combined with flawless fabrication techniques would minimize the confinement losses of the SPSM PCF to negligible levels, thereby significantly enhancing transmission distance (see Supplementary Section 11). Notably, DVMs completely eliminate polarization-mode dispersion inherent in conventional PCFs by exclusively sustaining vortex-polarized topological states from 0.2 THz to 0.5 THz, achieving the broadest operational bandwidth reported to date (Table 2).

By incorporating the flexibility of PCFs, we foresee even more unique mode properties for specific applications, such as extreme mode volume through high-order topological corner states48 or Moiré lattice49, and reduced confinement loss with miniaturized BIC50. This advancement positions THz PCFs as pivotal components for integrated systems, enabling breakthroughs in quantum cascade laser architectures, sensing, distributed quantum networks, and sub-wavelength resolution imaging.

Methods

Fabrications and materials

The photonic crystal fiber (PCF) was fabricated using stereolithography-based 3D printing technology (Form 3+ from Formlabs), which provides a laser spot size of 85 μm and an axis resolution of 25 μm. For the printing material, we selected high-temperature resin due to its relatively low absorption in the THz regime, with a refractive index of 1.631 + i0.009 (see Supplementary Section 19). This material offers several benefits, such as excellent mechanical properties, with a post-cured temperature tolerance of up to 238 °C at 0.45 MPa and an ultimate tensile strength of 49 MPa, ensuring the structural integrity and durability of the fabricated fibers. Two prototypes of 1 cm and 2 cm lengths were fabricated to characterize the near-field profiles and total loss, respectively. The 3D printing process, while highly precise, does have inherent limitations, such as potential deformation of the air holes during the curing process and residual material left in the holes. These challenges were addressed through post-processing, including cleaning and precision machining. The material selection and the 3D printing process, while optimal for this study, are not without trade-offs, such as absorption losses and minor dimensional variations due to the fabrication process. However, the results demonstrate that these factors do not significantly impair the fiber’s performance in the THz regime (Supplementary Section 16).

Measurements

THz-SNMS was used to measure the transmission field dynamics through the PCF, and the optical setup is shown in Supplementary Section 12. A femtosecond laser (800 nm, 38 fs, 80 MHz) was split into two coherent paths: pump and probe. The pump beam excites linearly polarized THz radiation from the photoconductive antenna. In the probe path, dispersion is compensated using a pair of gratings before the probe beam is coupled into an optical fiber, ensuring an output pulse width of 70 fs. A near-field photoconductive antenna, driven by the probe beam, covers a spectral range from 0.1 to 1.5 THz.

Time-domain terahertz pulses were obtained by moving the delay stage to adjust the difference between the pump and probe paths. Spatial information was acquired by performing a point-by-point scan in two dimensions (step size 50 µm, scan rate: 3 Hz). The DVM is effectively coupled by a focused THz beam to ensure sufficient overlap. During polarization measurements, the PCF was rotated relative to the polarization vector of incidence.

Numerical method

Numerical simulations were carried out using finite element methods. A simplified 2D model of the fiber cross-section was modeled in the xy-plane. With continuous translational symmetry along the z-axis, an external out-of-plane wavevector was introduced into the model. The refractive indices of the resin and air were set to 1.631 + i0.009 and 1, respectively. In the simulations, a Floquet periodic boundary condition was applied to the unit cell of the periodic lattices, while a scattering boundary condition was applied to the cladding of the PCF with Kekulé modulation. The in-plane projected band diagrams are obtained by scanning the in-plane Bloch wavevectors while fixing the out-of-plane wavevector. Similarly, the out-plane projected band diagrams are constructed by calculating the eigenfrequencies corresponding to various out-of-plane wavevector values at high-symmetry points of the Brillouin zone and then assembling these data to generate the complete projected dispersion.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Menssen, A. J. et al. Photonic topological mode bound to a vortex. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 117401 (2020).

Gao, P. L. et al. Majorana-like zero modes in Kekulé distorted sonic lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 196601 (2019).

Chen, C. W. et al. Mechanical analogue of a Majorana bound state. Adv. Mater. 31, 1904386 (2019).

Noh, J. et al. Braiding photonic topological zero modes. Nat. Phys. 16, 989–993 (2020).

Gao, X. M. et al. Dirac-vortex topological cavities. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 1012–1018 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Bulk-disclination correspondence in topological crystalline insulators. Nature 589, 381–385 (2021).

Lin, Z. K. et al. Topological phenomena at defects in acoustic, photonic and solid-state lattices. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 483–495 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Structured light meets machine intelligence. eLight 5, 26 (2025).

Yu, Z. et al. A spatial-frequency patching metasurface enabling super-capacity perfect vector vortex beams. eLight 4, 21 (2024).

Jo, J. et al. Spin-orbit coupling in van der Waals materials for optical vortex generation. Light Sci. Appl. 14, 277 (2025).

Wang, L. et al. Photoswitchable exceptional points derived from bound states in the continuum. Light Sci. Appl. 14, 377 (2025).

Jackiw, R. & Rossi, P. Zero modes of the vortex-fermion system. Nucl. Phys. B 190, 681–691 (1981).

Hou, C. Y., Chamon, C. & Mudry, C. Electron fractionalization in two-dimensional graphenelike structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 186809 (2007).

Yang, L. C. et al. Topological-cavity surface-emitting laser. Nat. Photonics 16, 279–283 (2022).

Ma, J. W. et al. Room-temperature continuous-wave topological Dirac-vortex microcavity lasers on silicon. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 255 (2023).

Han, S. et al. Photonic Majorana quantum cascade laser with polarization-winding emission. Nat. Commun. 14, 707 (2023).

Liu, J. H. et al. High-power electrically pumped terahertz topological laser based on a surface metallic Dirac-vortex cavity. Nat. Commun. 15, 4431 (2024).

Lin, H. & Lu, L. Dirac-vortex topological photonic crystal fibre. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 202 (2020).

Hou, Y. & Wang, G. Z. Broadband tunable single-mode single-polarization fiber. Opt. Commun. 351, 91–95 (2015).

Lu, D. K. & Liu, J. Broadband single-polarization single-mode operation in photonic crystal fibers with hexagonally latticed circular airholes. J. Lightwave Technol. 34, 2452–2458 (2016).

Li, X. et al. A novel single-polarization single-mode photonic crystal fiber with circular and elliptical air-holes arrays. Optoelectron. Lett. 9, 120–123 (2013).

Zhong, Z. et al. Study on crosstalk-free polarization splitter based on square lattice single-polarization photonic crystal fibers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 52, 7000107 (2016).

Shen, Y. T. et al. A double-cladding single polarization photonic crystal fiber and its structure deviation tolerance. IEEE Photonics J. 10, 7204310 (2018).

He, M. H. et al. Design, fabrication, and characterization of a single-polarization single-mode flexible hollow waveguide for low loss millimeter wave propagation. Opt. Express 30, 10178–10186 (2022).

Chen, H. B. et al. A terahertz single-polarization single-mode photonic crystal fiber with a rectangular array of micro-holes in the core region. Opt. Commun. 285, 3726–3729 (2012).

Hou, Y. et al. Terahertz single-polarization single-mode hollow-core fiber based on index-matching coupling. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 24, 637–639 (2012).

Yang, T. Y. et al. A terahertz (THz) single-polarization-single-mode (SPSM) photonic crystal fiber (PCF). Materials 12, 2442 (2019).

Yang, T. Y. et al. An epsilon-near-zero (ENZ) based, ultra-wide bandwidth terahertz single-polarization single-mode photonic crystal fiber. J. Lightwave Technol. 39, 223–232 (2021).

Ankan, I. M. et al. Polarization-maintaining and polarization-filtering negative curvature hollow core fiber in THz regime. In Proc. IEEE Region 10 Symposium (TENSYMP) 612–615 (IEEE, 2020).

Mollah, A., Rana, S. & Subbaraman, H. Polarization filter realization using low-loss hollow-core anti-resonant fiber in THz regime. Results Phys. 17, 103092 (2020).

Xue, L. et al. Single-polarization low loss terahertz hollow-core anti-resonant fiber with high polarization loss ratio. Opt. Commun. 537, 129460 (2023).

Tsuruda, K., Fujita, M. & Nagatsuma, T. Extremely low-loss terahertz waveguide based on silicon photonic-crystal slab. Opt. Express 23, 31977–31990 (2015).

Yang, Y. H. et al. Terahertz topological photonics for on-chip communication. Nat. Photonics 14, 446–451 (2020).

Wang, W. H. et al. On-chip topological beamformer for multi-link terahertz 6 G to XG wireless. Nature 632, 522–527 (2024).

Jiale, C. et al. Spin-dependent edge detection and imaging enabled by optical circularly polarised states. Light Adv. Manuf. 6, 8 (2025).

Li, H. S. et al. Terahertz fiber devices. APL Photonics 10, 021101 (2025).

Dash, S. et al. Terahertz wave propagation characteristics in graded Teflon-based solid-core photonic crystal fibre. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2426, 012021 (2023).

Islam, S. et al. A novel Zeonex based oligoporous-core photonic crystal fiber for polarization preserving terahertz applications. Opt. Commun. 413, 242–248 (2018).

Yadav, S., Lohia, P. & Dwivedi, D. K. A novel approach for identification of cancer cells using a photonic crystal fiber-based sensor in the terahertz regime. Plasmonics 18, 1753–1769 (2023).

Almawgani, A. H. M. et al. Identification of four detrimental chemicals using square-core photonic crystal fiber in the regime of THz. J. Appl. Phys. 133, 243103 (2023).

Ferdous, A. H. M. I. et al. Innovative refractive index sensor utilizing terahertz spectrum for early cancer detection: a photonic crystal fiber approach. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 83, 489–505 (2025).

Mortensen, N. A. Effective area of photonic crystal fibers. Opt. Express 10, 341–348 (2002).

Hamid, N. I. B. et al. High birefringent slotted core slotted cladding, porous core PCF for THz waveguide. Opt. Commun. 574, 131120 (2025).

Eid, M. M. A. et al. Hollow core photonic crystal fiber (PCF)–based optical sensor for blood component detection in terahertz spectrum. Braz. J. Phys. 51, 1017–1025 (2021).

Islam, A. et al. Wheel structured Zeonex-based photonic crystal fiber sensor in THz regime for sensing milk. Appl. Phys. A 127, 311 (2021).

Zhao, J. et al. Review of femtosecond laser direct writing fiber-optic structures based on refractive index modification and their applications. Opt. Laser Technol. 146, 107473 (2022).

Huang, H., Yang, L. M. & Liu, J. Femtosecond fiber laser based metal blackening. In Proc. SPIE 8876, Nanophotonics and Macrophotonics for Space Environments VII (SPIE, 2013).

Gong, R. R. et al. Topological photonic crystal fibers based on second-order corner modes. Opt. Lett. 46, 3849–3852 (2021).

Ouyang, Y. H. et al. Singular dielectric nanolaser with atomic-scale field localization. Nature 632, 287–293 (2024).

Chen, Z. H. et al. Observation of miniaturized bound states in the continuum with ultra-high quality factors. Sci. Bull. 67, 359–366 (2022).

Xue, L. et al. Single polarization single mode THz hollow-core anti-resonant waveguide with multi-size semi-elliptical tubes and high-resistance silicon layer. Results Phys. 58, 107523 (2024).

Liu, Q. et al. Negative curvature fiber (NCF) polarization filter with large polarization loss ratio and ultralow loss in the terahertz range. Opt. Commun. 568, 130736 (2024).

Linsie, A. A., Mondal, S. & Prince, S. Highly birefringent terahertz PCF using epsilon-near-zero (ENZ) material for polarization maintaining applications. In Proc. 10th International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication (ICSC) 110–113 (IEEE, 2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Award No.: 62335011), National Key R&D Program of China (Award No.: 2024YFA1410100), Guangdong Provincial Quantum Science Strategic Initiative (Award No.: GDZX2406003), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (Award No.: JCYJ20241202125300002, JCYJ20230807093617036), and high level of special funds from Southern University of Science and Technology (G030230001, G03034K004). The authors acknowledge the assistance from Jiankun Wang.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L. Cong conceived the idea and supervised the project with P. Shum. H. Xing fabricated the samples, conducted the experiments, simulations, and calculations, and drafted the manuscript. Z. Xue supported the THz-SNMS experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Perry Ping Shum serves as an editor for the journal, the other authors declare no competing interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xing, H., Xue, Z., Shum, P.P. et al. Experimental observation of topological Dirac vortex mode in terahertz photonic crystal fibers. Light Sci Appl 15, 97 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-026-02197-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-026-02197-6