Abstract

The workup of the vast majority of brain tumors is initiated at intraoperative consultation. These fresh tumor samples are often quite small and given the nature of the “prime real estate” being sampled, there is never a guarantee that additional tissue will be provided to the responsible pathologist upon request. The 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Central Nervous System (CNS) Tumors introduced the concept of “integrative diagnoses,” many diagnostic entities now requiring molecular testing in addition to the more routine pathologic workup. Molecular testing relative to targeted therapeutics may also be requested in many circumstances. That said, appropriate preparation for and handling of any potential brain tumor sample at intraoperative consultation is crucial to (1) provide diagnostic information to the operating neurosurgeon that can influence the course of the procedure, and (2) best allow for any necessary ancillary studies purposed for diagnosis and patient care. This review highlights best practices in handling brain tumor intraoperative consultations in this era of expanding required molecular testing. Included is a high-yield overview of ancillary/molecular testing commonly utilized in the workup of infiltrative gliomas, CNS embryonal tumors, and ependymomas, as well as molecular testing to aid in determination of targeted therapeutic options.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For numerous decades, the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) has relied exclusively on findings from microscopy, supplemented with additional ancillary studies (immunohistochemistry (IHC) and electron microscopy) as needed. Research has led to an expanding list of brain tumor-associated (and sometimes tumor-specific) genetic alterations, though the clinical application of genetic testing by way of cytogenetics, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and various molecular platforms has until recently been limited. The advent of high-throughput/high-resolution (epi)genetic and transcriptomic testing has uncovered numerous important prognostic and predictive determinants, and likewise several brain tumor “molecular signatures” with diagnostic utility. The most recent edition of the WHO classification (WHO 2016) introduced the concept of “integrative diagnoses,” many diagnostic entities now requiring molecular testing to supplement the more routine pathologic workup [1, 2]. Several brain tumor categories have undergone a major restructuring, particularly diffuse gliomas, ependymomas, and CNS embryonal tumors. Requests by clinicians for molecular testing relative to targeted therapeutics are also becoming commonplace. That said, the appropriate preparation for and handling of any potential brain tumor sample at intraoperative consultation (intraop consult) has become even more crucial. It is at the time of intraop consult when a pathologist can (1) provide diagnostic information to the operating neurosurgeon that can influence the course of the procedure, and (2) handle the tissue in such a way as to best allow for any necessary ancillary studies (including molecular) for diagnosis and patient care. What follows is a summation of the best practices in handling brain tumor intraoperative consultations in this era of expanding required molecular testing. Included is a high-yield overview of ancillary/molecular testing commonly utilized in the workup of infiltrative gliomas, CNS embryonal tumors, and ependymomas, as well as molecular testing to aid in determination of targeted therapeutic options.

Preparation for brain tumor intraoperative consultation

To prepare for any intraoperative consultation (here we are focusing on neuropathology cases), pathologists and pathology trainees are behooved to arm themselves with as many tools as they have at their disposal. The goal here is to not only provide the best possible diagnosis to their neurosurgical colleagues but also to handle/process tissue in such a way as to ensure any necessary ancillary testing can be performed. To that end, there are quite a few important pieces of information that one should seek out regarding the patients who are the subjects of impending neuropathology intraop consults. It is crucial to examine clinical patient demographics and history as well as neuroimaging studies to best formulate a potential differential diagnosis. It is this differential that will guide intraop consult specimen-handling strategies to minimize misdiagnosis and maximize tissue available for necessary ancillary testing.

A plethora of different neoplasms arise in the CNS, ranging from the low-grade and generally benign-behaving pilocytic astrocytoma to the highly aggressive glioblastoma and atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT). Several excellent textbooks and atlases are available as references for this topic [3, 4]. It is important to remember however that not every neurosurgical specimen will turn out to be a primary brain tumor. Metastases from neoplasms elsewhere in the body, infections (meningitis, encephalitis, or abscess), demyelinative (multiple sclerosis), and other inflammatory processes (sarcoid, infarct, hemorrhage, etc.) may all be biopsied by neurosurgeons, and therefore could all potentially be encountered by pathologists for intraop consult. Knowing as many clinical and radiographic details pertaining to a case as possible is crucial in minimizing diagnostic inaccuracies. Herein we will focus specifically on clinical and neuroimaging details helpful in the workup of brain tumor intraop consults.

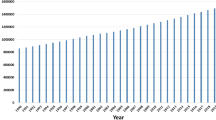

Patient demographics and clinical history

One of the most crucial pieces of clinical information that should be considered in preparation for a brain tumor intraop consult is patient age. Children and older adults are the two main age groups that develop brain tumors. Although numerically the incidence of primary brain tumors in adults is much higher than that of children, a significantly larger proportion of pediatric brain tumors are malignant. According to the most recent Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States statistical report on primary CNS tumors, the most common tumors arising in children age 0–4 years are the embryonal “small round blue cells tumors” (including medulloblastoma (MB)), followed by pilocytic astrocytoma, malignant gliomas, and ependymomas [5]. Throughout childhood, pilocytic astrocytoma is common, and subsequently pituitary adenoma and meningioma become more common into adolescence and early adulthood. Overall, meningioma remains the most common primary CNS tumor from age 35 years through old age. Though glioblastoma is uncommon in children, from middle age on glioblastoma is second only to meningioma in terms of its incidence. Although in most circumstances there is no huge difference between the genders in terms of their incidence of CNS tumors overall, certain tumor types tend to segregate strongly by gender. These include meningiomas, which are much more common in women, and germ cell tumors (particularly germinomas), arising mainly in the pineal region/midline structures of young boys.

Many heritable disorders carry with them a predilection for one or more CNS lesions. For instance, pilocytic astrocytomas (especially those involving optic pathway structures) may be encountered in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Although bilateral vestibular schwannomas of the cerebellopontine angle are the hallmark of neurofibromatosis type 2, meningiomas are common as well, often arising in multiplicity and/or in childhood. Li-Fraumeni syndrome predisposes to a variety of brain tumors including astrocytomas, embryonal tumors, and choroid plexus carcinoma. MBs may arise in the context of Gorlin and Turcot 2 syndromes, whereas Turcot 1 carries with it an increased risk for astrocytomas. Rhabdoid predisposition syndrome and Schwannomatosis are both heritable disorders associated with SMARCB1 (INI1) alterations, but with quite different phenotypes: AT/RT is the signature brain tumor of the former, whereas multiple schwannomas are typical of the latter. Lastly, Von Hippel-Lindau disease (hemangioblastoma), tuberous sclerosis (subependymal giant cell astrocytoma—SEGA), and Cowden disease (dysplastic gangliocytoma of the cerebellum) each infer a propensity to develop very specific brain tumors [3, 4]. Knowing that a given patient has one of these disorders should alert the pathologist to specific tumors to look out for at the time of intraop consult.

Neuroimaging 101

A great number of clues to a brain tumor’s possible identity can be gleaned from neuroimaging studies. This information can be obtained through conversation with the neurosurgeon or reading neuroradiology reports; better still is actually looking at available computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging studies. When reviewing neuroimaging studies, one of the first things to determine is whether there is more than one lesion. Lesional multiplicity tends to equate with either metastases from elsewhere in the body or a destructive/demyelinative or infectious process. Key exceptions to this rule would be (1) CNS dissemination/“drop mets” from a CNS embryonal tumor or ependymoma; (2) multiple intracranial schwannomas or meningiomas, often arising in the context of cancer-predisposition syndromes as noted above; and (3) primary CNS lymphoma arising in an elderly or immunocompromised patient. If the latter is suspected based on intraoperative assessment, it is imperative to submit tissue upfront for additional hematopathologic studies including flow cytometry and touch preparations for FISH analysis. A word of caution: any of the above pathologies that tend toward lesional multiplicity may also present as a solitary lesion.

It is essential to determine the specific neuroanatomic location of a potential brain tumor as this can greatly focus the differential diagnoses. For example, choroid plexus and ependymal tumors, MB, as well as SEGA, central neurocytoma, and an occasional meningioma will arise in association with the ventricular system (intraventricular/paraventricular), whereas the vast majority of infiltrative astrocytomas and oligodendroglial tumors arise within the cerebral hemispheres. Meningiomas are by far the most common dura-based tumors, however solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma (SFT/HPC) may pose a significant diagnostic challenge by closely mimicking both fibrous meningioma and a variety of other mesenchymal non-meningothelial dural-based tumors. Although not definitionally required for diagnosis, the WHO 2016 nonetheless highly recommends demonstration of either the NAB2:STAT6 fusion or nuclear STAT6 expression to confirm the diagnosis of SFT/HPC [6, 7]. Thankfully, there are also a number of special locations in the CNS that when mentioned, should bring on a knee-jerk response of only a single or very limited number of tumors. These include: sella—pituitary adenoma and craniopharyngioma; suprasellar/hypothalamic—germ cell tumor, craniopharyngioma, and pilocytic/pilomyxoid astrocytoma; pineal region—germinoma/germ cell tumors and pineal parenchymal tumors; and the cerebellopontine angle—schwannoma, meningioma, choroid plexus tumors, and AT/RT (in infants). The posterior fossa also houses a limited list of tumors, some of which display prototypical imaging features as discussed below.

A variety of other lesional neuroimaging qualities can provide important clues to potential diagnoses. One particularly helpful neuroimaging feature is whether a given lesion is infiltrative or demarcated/circumscribed. Astrocytomas (WHO grades II through IV) and oligodendroglial tumors are typically infiltrative brain tumors, including the recently codified entity diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27M-mutant. The latter may present either as a diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) (Fig. 1a) or an infiltrative lesion arising within other midline structures (thalamus and spinal cord). The vast majority of other brain neoplasms are circumscribed, however other imaging characteristics may help separate them one from another. For instance, only a few specific tumors present as cystic lesions with contrast-enhancing mural nodule(s): pilocytic astrocytoma (Fig. 1b), ganglion cell tumors, pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, and hemangioblastoma. A ring enhancement pattern tends to connote high-grade glioma such as glioblastoma (Fig. 1c), though ring enhancement may be seen with other neoplastic (metastases and primary CNS lymphoma) and non-neoplastic (abscess, toxoplasma, radiation necrosis, or demyelination) conditions.

Neuroimaging findings. a (T2 MRI) A typical infiltrative glioma, in this case a diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG). Pilocytic astrocytoma (b) frequently presents as cystic lesion with contrast-enhancing mural nodule(s) (T1 post contrast MRI), while ring-enhancing lesions (c) are often glioblastomas (T1 post contrast MRI)

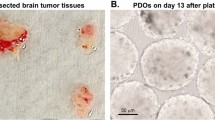

Best practices for brain tumor specimen handling: preparing high-quality cytologic and frozen section slides

Once the pathologist is armed with as much pertinent information as can be obtained (clinical history and neuroimaging findings), they are ready to tackle the technical portion of the brain tumor intraop consult. Tissue handling for these neuropathology specimens is often different when compared to more routine surgical pathology samples. It is common to receive extremely tiny tissue fragments for analysis; these could easily be lost in the process of cutting a frozen section. This reason alone emphasizes the need for pathologists responsible for these intraop consults to become proficient in performing and interpreting various cytology preparations (preps). They should likewise be familiar with which of these techniques to use in specific circumstances/specimen work-ups. What cytology preps are ultimately utilized will depend upon several factors, particularly lesion location/differential diagnosis and texture of tissue submitted (firm versus soft). Irrespective of the preps used, the findings of cytology testing are complementary to (and in some cases equally or even more diagnostic then) the frozen section findings.

Cytology for neuropathology intraoperative consultations

Cytology can be performed on even the tiniest of samples. It provides excellent cellular detail, often superior to that of frozen sections, with no freezing artifacts. It can provide extremely rapid results (particularly when using the Diff-Quik staining method). It even allows for recognition of some major tissue architectural features. The only downside to cytology is that it takes practice: practice in preparing interpretable cytology slides and practice mastering cytology-based diagnoses. To get the most out of cytology in the realm of working up neuropathology intraop consults, it is always a good idea to utilize more than one prep type as each may give complementary and different information. A good example of this is pairing a touch/drag with a smear preparation.

Touch (imprint) cytology preps can (and should) be used on all tissue samples, of any size and type. They are excellent for detecting processes with cellular dyscohesion; inflammatory processes, hematologic processes, pituitary adenomas, germinomas, small round blue cell tumors (Fig. 2a), and metastatic tumors (especially melanoma). Touch/drag preps provide similar utility and are excellent for dealing with necrotic/hemorrhagic tissue to try to sample for rare tumor cells. Smear/squash/crush preps are all variations on the central theme of putting a small bit of tissue between two glass slides and applying some pressure and movement to spread out the tissue/cells into very thin layers. Just how much pressure is used is dependent upon the density of the sample. Always start with the least amount of pressure and workup to increased pressure but be careful not to crack the slides!! Proficiency will come with experience. These preparations are best for samples of a size that allows you to cut it with a scalpel blade. They are excellent for showing tissue architecture and for determining glial (processes) (Fig. 2b) versus non-glial lesions. Other pertinent architectural features (papillary structures, perivascular and other rosettes, microvascular proliferation, Rosenthal fibers, and eosinophilic granular bodies) can be seen in smear preps (Fig. 2b). In the scrape prep technique, a scalpel blade is used to scrape off cells from a firm/hard tissue sample. This is especially useful for firm, fibrous, bony, or calcified samples, all of which may not cut well for frozen section.

Intraoperative consult cytology. a Touch preparations are excellent for demonstrating lesions with cellular dyscohesion, such as this medulloblastoma (Diff-Quik). This hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained smear of a pilocytic astrocytoma (b) demonstrated both processes (a feature typical of gliomas) as well as multiple densely eosinophilic Rosenthal fibers

In terms of stains for cytology preps, some pathologists choose to use the old reliable hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain for cytology preparations, others prefer the rapid Diff-Quik stain, while still other prefer to do both. Both stains have their own strengths and weaknesses, and often preference and confidence with using one or another depends upon a pathologist’s prior cytology training and experience. In the context of neuropathology cases, it never hurts to do both stains if the tissue allows. H&E is familiar to surgical pathologists, therefore allowing a more direct cellular comparison with frozen sections. It affords excellent nuclear detail. On the downside, it takes longer to perform than Diff-Quik, requires tissue fixation prior to application, and often causes loss of some intracytoplasmic features/vacuoles. Diff-Quik is a modified Wright Giemsa stain, is extremely rapid to perform (<30 s), and affords excellent cytoplasmic detail, including mucin and lipid. It is also good for staining extracellular substances (mucin, colloid, and ground substances) and offers familiar staining patterns to those of routinely processed blood and bone marrow smear samples. Unfortunately, nuclear detail is not as crisp as with H&E, and there may be air-drying artifacts.

Neuropathology frozen sections

Once a sample is processed for cytology, a frozen section may be the next diagnostic procedure (if necessary). An extremely important rule to remember for all neuropathology intraop consults: NEVER freeze all the tissue received. You may not get any more sample to evaluate, and you frequently will need to do ancillary studies. For tiny samples, don’t automatically freeze any tissue; cytology is often sufficient to determine that “lesional tissue is present” or even make a firmer diagnosis, and you are better off preserving as much uncorrupted tissue as possible for fixed sections and other studies. If you receive multiple cores or pieces, sample grossly different areas for frozen section, particularly soft mucoid areas and anything that does not look like typical light tan brain tissue. Freeze the sample as rapidly as possible to avoid artifact (don’t slow freeze/avoid using heat sinks). If the sample is received wet, attempt to dry it off before freezing the tissue.

Neurosurgeons are obviously interested in receiving a speedy and accurate diagnosis, but they are also a source of pertinent information relative to an intraop consult. They can inform the pathologist about additional clinical history, radiology findings, and their impression of the lesion at the time of surgery. Whether the surgical procedure is a biopsy versus a possible resection plays heavily into how specific of a diagnosis needs to be rendered by the pathologist. In the former situation, the surgeon is solely focused on obtaining diagnostic tissue from the lesion in question, and therefore “lesional tissue present” is an appropriate intraop consult diagnosis. If a tumor resection is being considered, a more specific tumor classification is typically expected. For any neurosurgical intraop consult, the pathologist must determine if lesional tissue is present; if that is not straightforward, or if the sample looks like necrosis or normal tissue only, let the neurosurgeon know. They may need to submit more tissue for intraop consult, and they may not be in the actual lesion.

Once lesional tissue is identified, the following determinations should be attempted, in order of increasing complexity and specificity: reactive/inflammatory versus neoplasm, metastases versus primary CNS neoplasm, glioma versus non-glial, and if glial low grade versus high grade. Depending upon many factors, on any given case you may or may not be able to get very far down this diagnostic ladder, but at the very least you’ll need to be able to determine if a sample contains “lesional tissue”. This basically means that what you’re seeing on the slides is not normal CNS tissue, and it appears to coincide with other information available about the patient, including clinical history, radiology findings, and the neurosurgeon’s impression. If you can get that far, you’ve done your job. Determining between entities further along this diagnostic ladder takes practice but can be accomplished in a high percentage of cases if one comes fully prepared to the intraoperative consultation with as much clinical and neuroimaging data as possible and using the available techniques discussed above. Being familiar with the histologic features of the most common CNS tumors will clearly provide for more specific diagnoses at intraop consult. These details are beyond the scope of this review, and the reader is referred to pertinent CNS tumor textbooks for reference [1, 4].

Putting it into practice: maximal utilization of brain tumor tissue for ancillary molecular testing

Armed with pertinent patient clinical and neuroimaging information and the ability to prepare superb cytology preps and frozen sections, the pathologist should be in fine shape to provide an accurate and appropriate intraop consult diagnosis to the operating neurosurgeon. That is only the first part of the workup however; now (s)he will need to handle the submitted tissue in such a way as to best allow for any necessary ancillary studies purposed for diagnosis and patient care. To do that effectively, one needs to be familiar with the concept of “integrative diagnosis” and the fact that several diagnostic entities within the 2016 WHO classification of CNS tumors now require molecular testing in addition to the more routine pathologic workup [1, 2, 8]. Molecular testing relative to targeted therapeutics may also be requested by clinicians. As noted earlier, these brain tumor samples are often minute, and there is never a guarantee that additional tissue will be provided past what is received for the intraop consult. What follows is a high-yield overview of ancillary/molecular testing commonly utilized in the workup of infiltrative gliomas, CNS embryonal tumors, and ependymomas, as well as molecular testing to aid in determination of targeted therapeutic options.

Infiltrative gliomas

The WHO 2016 introduced a major restructuring of several brain tumor groups, particularly diffuse gliomas. This diverse group of tumors includes the diffuse astrocytomas (grades II through IV), oligodendroglial tumors (grades II and III), and the newly codified entity diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27M-mutant (WHO grade IV) [1]. The workup for all of these infiltrative gliomas includes a combined assessment of (1) histologic features for determination of phenotype (astrocytic versus oligodendroglial) and grade, and (2) assessment of genotype. To complicate matters, it is well known that many pediatric gliomas, though histologically resembling their adult counterparts, carry strikingly different molecular signatures/driver mutations. At present however, the core molecular workup of infiltrative gliomas, irrespective of patient age, follows a standard algorithm for assessment of key driver mutations [1, 2]; diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27M-mutant (K27M-DMG) is a notable exception, as described below.

Historically, diffuse astrocytomas have been graded based on specific histologic criteria. WHO grade II diffuse astrocytomas are notable for moderate nuclear pleomorphism, while high-grade astrocytomas harbor in addition elevated mitotic activity (grade III—anaplastic astrocytoma) together with microvascular proliferation and/or palisading necrosis (grade IV—glioblastoma). This holds true in WHO 2016, but an additional phase of assessment is determination of mutation status of IDH1 and IDH2. All grades of diffuse astrocytoma are further divided into IDH-mutant or IDH-wildtype. The not otherwise specified (NOS) category is reserved for rare instances in which a full workup of IDH status cannot be performed [1]. Mutant-specific IHC using antibodies for protein resultant from IDH1 R132H mutation (the most common of glioma-associated IDH mutations) should be the initial step in this molecular workup [9, 10]. This can be performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections, and if positive, the lesion is designated as IDH-mutant. (Fig. 3a) If IHC testing is negative, IDH assessment proceeds to sequencing of IDH1 codon 132 and IDH2 codon 172; this too can be performed on FFPE tissue, though multiple scrolls with high tumor content are generally required. Fresh-frozen tumor tissue is an alternative, though often not available. If sequencing is negative, the tumor is deemed IDH-wildtype. The majority of grade II and III astrocytomas in adults will harbor IDH mutations, these tumors carrying a better prognosis then their IDH-wildtype counterparts. The vast majority of glioblastomas will be IDH-wildtype (90%) corresponding to de novo glioblastomas arising after age 55 years; IDH-mutant glioblastomas predominate in younger adults, have lower-grade precursor lesions, and have comparably prolonged survival [11]. Note that mutant-specific IHC alone may suffice for determination of IDH mutation status in glioblastomas arising in older patients (>55 years) [12].

Diffuse gliomas. Immunohistochemistry utilizing mutant-specific antibody targeting the IDH1 R132H mutation product decorates the lesional cells of this IDH-mutant anaplastic astrocytoma (a). This diffuse glioma was detected within bilateral thalami at diagnosis (b; T2 MRI); H3 K27M mutant-specific IHC of the biopsy sample demonstated strong nuclear staining of the tumor cells (c), thus this tumor qualified for the diagnosis of diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27M-mutant

Oligodendrogliomas are handled in much the same way as diffuse astrocytomas, first by histologic assessment for grade determination followed by molecular workup. The well-established association of codeletion of whole arm chromosomes 1p and 19q (1p/19q codel) with the oligodendroglial phenotype [13,14,15,16] has been embraced by the WHO 2016 as a diagnostic requirement (along with demonstration of IDH mutation) for the diagnosis of oligodendroglioma or anaplastic oligodendroglioma [1]. In the pediatric age group, both of these alterations are extremely uncommon in diffuse gliomas of any grade or histology prior to age 10 years [16,17,18], although at present IDH mutation and 1p/19q codel testing is still required. Because of this, most pediatric oligodendrogliomas end up in the “oligodendroglioma, NOS” category. In terms of a testing algorithm for infiltrative gliomas in general, the reader is directed to the article by Reuss et al. [10], which summarizes a cost-effective step-wise schema for utilizing combined IDH1 and ATRX testing (ATRX loss and 1p/19q codel are virtually mutually exclusive) [10, 19], followed by 1p/19q assessment and IDH1/2 sequencing as needed. A word of caution relative to test selection for 1p/19q analysis: the current commercially available FISH probes used for 1p/19q codel assessment were designed to identify the regions of common deletion across glioma subtypes; although they are quite sensitive, they are by no means 100% specific for identifying whole arm 1p and 19q loss. 1p/19q FISH can be confidently utilized in the context of a typical oligodendroglioma phenotype, but in pediatric oligodendrogliomas, gliomas with equivocal morphology, or high-grade lesions in which glioblastoma is a consideration, 1p/19q codel should be assessed by loss of heterozygosity or single-nucleotide polymorphism array/array comparative genomic hybridization platforms. Unstained slides can be used for IHC and FISH, while FFPE scrolls (or fresh-frozen tissue) are required for the later assays.

Diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27M-mutant, WHO grade IV (K27M-DMG) is a newly recognized entity, defined in WHO 2016 as an “infiltrative midline high-grade glioma with predominantly astrocytic differentiation and a K27M mutation in either H3F3A or HIST1H3B/C″ [1]. The K27M mutation defining this entity interferes with EZH2/PRC2 methyltransferase activity, resulting in a globally hypomethylated state and derepression of PRC2 target genes [1]. H3 K27M mutations are found in approximately 80% of DIPGs, and nearly half of diffuse gliomas arising at other midline locations (thalamus, spinal cord, cerebellum, and pineal region) [1]. (Fig. 3b) The majority arise in children, though occasional adult examples have been described. K27M-DMGs are quite heterogeneous, both from a radiographic and histologic standpoint. Classically, DIPGs present as expansile pontine lesions often with locoregional infiltration, although a variety of other imaging findings can be encountered such as intratumor contrast enhancement, hemorrhage, necrosis, gliomatosis-like diffuse parenchymal involvement, or leptomeningeal and/or intraventricular spread. Their histologic appearance is widely variable, ranging from a bland hypocellular infiltrative astrocytoma to a highly pleomorphic glioma with features typical of glioblastoma. In the context of DIPG, it is the K27M signature that is most closely associated with aggressive biologic behavior, independent of the histologic appearance [1]. A number of case reports/series describe H3 K27M mutation found in the context of other histologies (ganglioglioma and pilocytic astrocytoma), however the general consensus is that the K27M-DMG diagnosis should be reserved for midline infiltrative gliomas bearing the K27M mutation [20,21,22]. It should be emphasized that not all infiltrative gliomas arising in the midline qualify for the pathologic diagnosis of K27M-DMG. To be designated as such requires demonstration of the defining H3 K27M mutation. This may be accomplished by direct sequencing but is also readily demonstrated via IHC. Mutant-specific IHC antibodies targeting the product of the H3 K27M mutation (note both H3.3 and H3.1 alterations are detected) will show diffuse nuclear positivity in K27M-DMGs (Fig. 3c) while H3K27me3 (trimethylation) antibody will show loss of nuclear staining, reflecting hypomethylation [23, 24]. The workup of midline gliomas found lacking of H3 K27M mutation should follow the infiltrative glioma algorithm noted above, with histomorphologic classification and grading, followed by assessment of IDH mutation/codeletion 1p/19q status as appropriate based on histologic findings.

Embryonal tumors

Medulloblastoma

MB is both the most common CNS embryonal tumor and most common malignant pediatric brain tumor. The management of these patients has traditionally focused on clinical variables (patient age, metastatic disease at presentation, and tumor remaining following surgical debulking) and histology for patient risk stratification [25, 26]. This strategy unfortunately does not take genetic heterogeneity of these tumors into account. Multiple independent groups have determined that MBs cluster into (epi)genetically defined subgroups [27,28,29], ultimately leading to the consensus designation of four major molecular subgroups of MB: WNT-activated, SHH-activated, and non-WNT/non-SHH (groups 3 and 4) [30]. Each of these groups has distinct genetic/gene expression and methylome profiles, and corresponding typical patient demographics, histologic features, and prognosis [30, 31].

Taking this into account, the WHO 2016 now includes both genetic and histologic classifications of MBs, the latter retained for its ability to provide relevant clinical information in cases where molecular evaluation is not feasible [1, 32]. The genetically defined subgroups of the WHO 2016 parallel those of the consensus statement listed above [1, 30], and are assessed in parallel to histology. Note that the SHH-activated MBs are further separated into TP53-wildtype and TP53-mutant subgroups: poor clinical outcomes have been associated with the TP53-mutant signature, whereas TP53-wildtype SHH-activated MBs are currently considered low risk [33,34,35]. WNT-activated, the least common genetically defined MB, are likewise considered low risk [36,37,38]. Group 3 MBs carry the worst prognosis and frequently harbor MYC amplification and isochromosome 17q [29, 30]. Group 4 MBs, the most common of MB genetic subgroups, likewise frequently have copy number alterations on chromosome 17 or MYCN amplification.

The pathologic workup of MBs thus currently takes on two steps: histologic assessment and genetic subgrouping. The histologically defined MB classification retains the well-defined microscopic definitions of prior WHO classifications, to include classic, desmoplastic/nodular (DN), large cell/anaplastic (LCA), and extensively nodular MBs [39]. Of note, DN and extensively nodular MBs correspond exclusively to the SHH-activated genetic subgroup, whereas LCA MB are mainly group 3 or SHH-activated [32]. IHC using antibodies targeting β-catenin, GAB1, YAP1, and p53 can provide a rapid cost-effective surrogate workup for genetic subgrouping. YAP1 positivity and nuclear β-catenin staining (Fig. 4a) correspond well to the WNT-activated MB subgroup, though the WHO 2016 advocates for “detection of monosomy 6 or CTNNB1 mutation” as an optimal evaluation [1, 32, 38]. MBs that are found immunopositive for GAB1 (Fig. 4b) and YAP1 correspond with the SHH-activated MB subgroup; these tumors should be subjected to addition workup with p53 IHC as diffuse nuclear p53 accumulation correlates well with the presence of TP53 mutation [32, 35]. Unfortunately, these IHC assays cannot effectively differentiate group 3 from group 4 MB, and thus methylation or gene expression profiling remains the gold standard for MB genetic subgroup identification. Both assays can generally be performed on FFPE tissue scrolls (though fresh-frozen tissue is preferable), methylation array profiling having the additional ability to asses copy number variations (such as gene amplifications, deletions, and isochromosome status) across the genome. Similarly, definitive assessment of TP53 (or CTNNB1) mutation status requires gene sequencing, which can be accomplished through Sanger or targeted next-generation sequencing platforms. Like methylation profiling, both require either FFPE tissue scrolls or preferably fresh-frozen tissue (if available).

CNS embryonal tumors. Nuclear staining with β-catenin (a) or cytoplasmic GAB1 (b) by IHC are found in WNT-activated and SHH-activated medulloblastoma genetic subgroups, respectively. This AT/RT shows a characteristic loss of nuclear staining with IHC antibody for INI1; note blood vessels acting as positive internal control, showing strong INI1 staining (c). C19MC FISH assay performed on an ETMR, C19MC-altered demonstraing tumor cell nuclei with evidence of C19MC amplification (multiple red C19MC signals versus two green-labeled 19p control probes per nucleus) (d)

Other embryonal tumors

The WHO 2016 made additional updates relative to CNS embryonal tumors, including requiring demonstration of inactivation of either SMARCB1 (INI1) or SMARCA4 (BRG1) genes for the diagnosis of AT/RT [1]. IHC on routinely processed tumor samples with antibodies targeting the respective nuclear proteins can easily accomplish this task (Fig. 4c), although sequencing methods may be required in some circumstances. Tumors lacking these genetic features but otherwise resembling AT/RT are now categorized as “CNS embryonal tumor with rhabdoid features.” Three aggressive embryonal tumors, including tumors previously classified as ependymoblastoma, medulloepithelioma, and embryonal tumor with abundant neuropil and true rosettes, have now been combined under the new WHO 2016 entity termed embryonal tumor with multilayered rosettes (ETMR), C19MC-altered. These aggressive tumors of infancy may arise throughout the CNS, and have been found to share a unifying genetic signature, specifically amplification (or uncommonly, fusions) involving the C19MC microRNA cluster [40,41,42,43]. In fact, any CNS embryonal tumor bearing a C19MC alteration should be assigned this diagnosis as per WHO 2016 criteria [1]. FISH assays can readily identify these C19MC alterations (Fig. 4d) and should be utilized judiciously when ETMR enters the differential diagnosis. Although ETMR tends to show increased expression of LIN28A by IHC, only demonstration of the characteristic C19MC alteration guarantees diagnostic certainty as LIN28A expression is by no means specific for this entity [43, 44]. The WHO 2016 chose to also include ETMR, NOS and Medulloepithelioma for those lesions lacking demonstrable C19MC abnormalities but with pathology otherwise typical of these diagnoses [1]. After ruling out all of the aforementioned entities, the term CNS embryonal tumor, NOS would apply for the rare non-descript embryonal tumor; CNS primitive neuroectodermal tumor no longer is a recognized entity. There is evidence already mounting that this last group of tumors may in fact contain molecularly definable subgroups, though additional experience is needed to more clearly delineate specific diagnostic criteria and/or prognostic significance [45].

Ependymomas

Historically, the focus for ependymoma classification has centered upon delineating an accurate objective histologic definition for anaplasia. Unfortunately, correlation between the various proposed histologic variables (hypercellularity, mitotic rate/proliferation, microvascular proliferation, and necrosis) and patient outcomes has been inconsistent [46,47,48,49,50]. Similar to MBs, ependymomas do not share a singular molecular signature; instead, there appears to be multiple genetically distinct subgroups of ependymoma, each with its own anatomic location and age of occurrence, histologic features, and biologic potential [51,52,53]. In a recent large multi-institutional study, supratentorial ependymomas harboring RELA fusions were found to be significantly more biologically aggressive then supratentorial subependymomas and ependymomas with Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1) fusions [51].

To that end, the WHO 2016 codified ependymoma, RELA fusion-positive as a new entity [1]. This genetically defined ependymoma accounts for upwards of 70% of supratentorial pediatric ependymomas. It is rare in adults and does not occur at other anatomic locations [54, 55]. Chromothripsis results in the C11orf95-RELA fusion, the most commonly demonstrated alteration, though occasionally C11orf95 or RELA end up fusing with alternate partners [54,55,56]. Although clear-cell morphology and branching capillaries are often present (Fig. 5a), RELA fusion-positive ependymomas may resemble other conventional ependymomas, and grading is based on given criteria within the WHO 2016 and not assigned simply by molecular status [56]. L1CAM expression (detectable by IHC) (Fig. 5b) is a useful surrogate marker for the presence of RELA fusion [55], however it is not entirely specific, and staining may be encountered in other settings. Because of this, definitive diagnosis requires demonstration of signature fusions, which can be readily accomplished using break-apart FISH probe sets around both RELA and C11orf95 region; split red and green signals would demonstrate the positive fusion status as seen in Fig. 5c.

Ependymomas. Ependymoma, RELA fusion-positive can present with a clear-cell morphology and branching vasculature (a). Strong diffuse immunopositivity for antibodies targeting L1CAM is often detected (b), however direct assessment of RELA fusion status by dual-color break-apart FISH assay is needed for diagnosis of RELA fusion-positive ependymoma (c; note nuclei with singular yellow and split red and green signals, indicative of RELA fusion). d A posterior fossa ependymoma-group A with diffuse loss of nuclear staining for H3K27me3 (trimethylation) by IHC

The WHO 2016 does not prescribe molecular testing to diagnose or subgroup other ependymal tumors, however there is mounting evidence that there exist molecularly and biologically distinct subgroups of pediatric posterior fossa ependymomas (PFEs) [51]. PFE-group A tumors are biologically aggressive (similar to RELA fusion-positive ependymomas), arising in infants/young children, whereas PFE-group B are tumors of older children and are less aggressive then their group A counterparts [57,58,59]. H3K27me3 (trimethylation) staining by IHC has recently been proposed as a useful surrogate marker to differentiate PFE-group A from group B ependymomas, with loss of nuclear staining typical of group A tumors (Fig. 5d) [60, 61]. It is likely this and/or additional molecular subgroup analyses will become required testing for ependymomas in the near future.

Molecular testing to aid in determination of targeted therapeutic options

Table 1 summarizes the currently available molecular assays necessary to address the WHO 2016 CNS categories outline above. In addition to these entity or subgroup-defining classifiers, additional genetic testing may be requested in several tumor categories for determination of therapeutic options. For instance, virtually all pilocytic astrocytomas, and a significant proportion of gangliogliomas and pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas harbor demonstrable alterations involving the mitogen-activating protein kinase pathway, including BRAF V600E mutations and BRAF-KIAA1549 fusions [62,63,64,65]. As both are potentially targetable, either by V600E-specific or MEK inhibitors, oncologists are increasingly requesting confirmatory testing for these alterations. Both BRAF V600E mutations and BRAF fusions can be detected utilizing FFPE tissue samples, the former by either mutant-specific IHC antibodies or sequencing and the latter by FISH assays. MGMT promotor methylation status is routinely used for treatment planning for adult glioblastomas, with a variety of assays available through commercial labs (also utilizing FFPE tissue) [66]. As additional research and clinical trial data are amassed, a variety of new (epi)genetic tumor signatures/subgroupings and therapeutic targets are being identified, the testing of which will eventually make its way into the clinical laboratory [45, 67]. It therefore behooves every pathologist who handles brain tumor samples to be judicious in preserving as much tissue as possible (fresh-frozen and fixed) for potential future molecular testing.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this review has outlined best practices for the processing of brain tumors at the time of intraoperative consultation. Pathologists should strive to utilize all available tools (clinical and radiographic data) and appropriate cytologic/frozen section techniques to not only reach an appropriate intraoperative consultation diagnosis, but to utilize the available tissue in such a way as to ensure that all necessary tumor-specific ancillary molecular testing can be performed. Familiarity with the above-referenced entities and molecular techniques is key. For very small samples, it is advisable to cut additional upfront unstained slides (for potential IHC and FISH testing) and scrolls if possible (for sequencing/array-based assays). Larger specimens allow for a portion of sample to be frozen and preserved for similar purpose. With the continued exploration into the (epi)genetic and transcriptomic factors influencing brain tumorigenesis, it is clear that what is outlined above is but a glimpse of the clinical molecular testing yet to come.

References

Louis, DN, Ohgaki, H, Wiestler, OD, et al. (eds) World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Revised 4th Edition. Lyon, FRANCE: IARC Press, 2016.

Louis DN, Perry A, Burger P, Ellison DW, Reifenberger G,von Deimling A, et al. International Society Of Neuropathology—Haarlem consensus guidelines for nervous system tumor classification and grading. Brain Pathol. 2014;24:429–35.

Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Rodriguez FJ, Tihan T. (eds) Diagnostic Pathology: Neuropathology. 2nd Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2016.

Adesina A, Tihan T, Fuller CE, Poussaint TY. (eds) Atlas of pediatric brain tumors. 2nd edition. New York: Springer; 2016.

Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, Vecchione-Koval T, Wolinsky Y, Kruchko C, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2010-2014. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19:v1–88.

Schweizer L, Koelsche C, Sahm F, Pisa R, Capper D, Reuss D, et al. Meningeal hemangiopericytoma and solitary fibrous tumors carry the NAB2-STAT6 fusion and can be diagnosed by nuclear expression of STAT6 protein. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:651–8.

Berghoff AS, Kresl P, Bienkowski M, Koelsche C, Rajky U, Hainfellner JA, et al. Validation of nuclear STAT6 immunostaining as a diagnostic marker of meningeal solitary fibrous tumor (SFT)/hemangiopericytoma. Clin Neuropathol. 2017;36:56–9.

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–20.

Mellai M, Piazzi A, Caldera V, Monzeglio O, Cassoni P, Valente G, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations, immunohistochemistry and associations in a series of brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 2011;105:345–57.

Reuss DE, Sahm F, Schrimpf D, Schrimpf D, Wiestler B, Capper D, et al. ATRX and IDH1-R132H immunohistochemistry with subsequent copy number analysis and IDH sequencing as a basis for an “integrated” diagnostic approach for adult astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma and glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:133–46.

Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. The definition of primary and secondary glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:764–72.

Chen L, Voronovich Z, Clark K, Hands I, Mannas J, Walsh M, et al. Predicting the likelihood of an isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 or 2 mutation in diagnoses of infiltrative glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:1478–83.

Cairncross JG, Ueki K, Zlatescu MC, Lisle DK, Finkelstein DM, Hammond RR, et al. Specific genetic predictors of chemotherapeutic response and survival in patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1473–9.

Smith JS, Perry A, Borell TJ, Lee HK, O'Fallon JR, Hosek SM, et al. Alterations of chromosome arms 1p and 19q as predictors of survival in oligodendrogliomas, astrocytomas, and mixed oligoastrocytomas. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:636–45.

Perry A, Fuller CE, Banerjee R, Brat D, Scheithauer BW. Ancillary FISH analysis for 1p and 19q status: preliminary observations in 287 gliomas and oligodendroglioma mimics. Front Biosci. 2003;8:a1–9.

Rodriguez FJ, Tihan T, Lin D, McDonald W, Nigro J, Feuerstein B, et al. Clinicopathologic features of pediatric oligodendrogliomas: a series of 50 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1058–70.

Korshunov A, Ryzhova M, Hovestadt V, Bender S, Sturm D, Capper D, et al. Integrated analysis of pediatric glioblastoma reveals a subset of biologically favorable tumors with associated molecular prognostic markers. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:669–78.

Lassaletta A, Zapotocky M, Bouffet E, Hawkins C, Tabori U. An integrative molecular and genomic analysis of pediatric hemispheric low-grade gliomas: an update. Childs Nerv Syst. 2016;32:1789–97.

Liu XY, Gerges N, Korshunov A, Sabha N, Khuong-Quang DA, Fontebasso AM, et al. Frequent ATRX mutations and loss of expression in adult diffuse astrocytic tumors carrying IDH1/IDH2 and TP53 mutations. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:615–25.

Solomon DA, Wood MD, Tihan T, et al. Diffuse midline gliomas with histone H3-K27M mutation: a series of 47 cases assessing the spectrum of morphologic variation and associated genetic alterations. Brain Pathol. 2015;26(5):569–80.

Louis DN, Giannini C, Capper D, Paulus W, Figarella-Branger D, Lopes MB, et al. cIMPACT-NOW update 2: diagnostic clarifications for diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27M-mutant and diffuse astrocytoma/anaplastic astrocytoma, IDH-mutant. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;135:639–42.

Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Mulcahy Levy JM. H3 K27M-mutant gliomas in adults vs. children share similar histological features and adverse prognosis. Clin Neuropathol. 2018;37:53–63.

Bechet D, Gielen GG, Korshunov A, Pfister SM, Rousso C, Faury D, et al. Specific detection of methionine 27 mutation in histone 3 variants (H3K27M) in fixed tissue from high-grade astrocytomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:733–41.

Venneti S, Santi M, Felicella MM, Yarilin D, Phillips JJ, Sullivan LM, et al. A sensitive and specific histopathologic prognostic marker for H3F3A K27M mutant pediatric glioblastomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:743–53.

Eberhart CG, Kepner JL, Goldthwaite PT, Kun L, Duffner PK, Friedman HS, et al. Histopathologic grading of medulloblastomas: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. Cancer . 2002;94:552–460.

Zeltzer PM, Boyett JM, Finlay JL, Albright AL, Rorke LB, Milstein JM, et al. Metastasis stage, adjuvant treatment, and residual tumor are prognostic factors for medulloblastoma in children: conclusions from the Children’s Cancer Group 921 randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:832–45.

Pomeroy SL, Tamayo P, Gaasenbeek M, Sturla LM, Angelo M, McLaughlin ME, et al. Prediction of central nervous system embryonal tumour outcome based on gene expression. Nature. 2002;415:436–42.

Cho YJ, Tsherniak A, Tamayo P, Santagata S, Ligon A, Greulich H, et al. Integrative genomic analysis of medulloblastoma identifies a molecular subgroup that drives poor clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1424–30.

Kool M, Korshunov A, Remke M, Jones DT, Schlanstein M, Northcott PA, et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: an international meta-analysis of transcriptome, genetic aberrations, and clinical data of WNT, SHH, Group 3, and Group 4 medulloblastomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:473–84.

Taylor MD, Northcott PA, Korshunov A, Remke M, Cho YJ, Clifford SC, et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: the current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:465–72.

Northcott PA, Jones DT, Kool M, Robinson GW, Gilbertson RJ, Cho YJ, et al. Medulloblastomics: the end of the beginning. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:818–34.

Ellison DW, Dalton J, Kocak M, Nicholson SL, Fraga C, Neale G, et al. Medulloblastoma: clinicopathological correlates of SHH, WNT, and non-SHH/WNT molecular subgroups. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:381–96.

Zhukova N, Ramaswamy V, Remke M, Pfaff E, Shih DJ, Martin DC, et al. Subgroup-specific prognostic implications of TP53 mutation in medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2927–35.

Rutkowski S, von Hoff K, Emser A, Zwiener I, Pietsch T, Figarella-Branger D, et al. Survival and prognostic factors of early childhood medulloblastoma: an international meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4961–8.

Tabori U, Baskin B, Shago M, Alon N, Taylor MD, Ray PN, et al. Universal poor survival in children with medulloblastoma harboring somatic TP53 mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1345–50.

Pietsch T, Schmidt R, Remke M, Korshunov A, Hovestadt V, Jones DT, et al. Prognostic significance of clinical, histopathological, and molecular characteristics of medulloblastomas in the prospective HIT2000 multicenter clinical trial cohort. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:137–49.

Ellison DW, Onilude OE, Lindsey JC, Lusher ME, Weston CL, Taylor RE, et al. beta-Catenin status predicts a favorable outcome in childhood medulloblastoma: the United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group Brain Tumour Committee. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7951–7.

Fattet S, Haberler C, Legoix P, Varlet P, Lellouch-Tubiana A, Lair S, et al. Beta-catenin status in paediatric medulloblastomas: correlation of immunohistochemical expression with mutational status, genetic profiles, and clinical characteristics. J Pathol. 2009;218:86–94.

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK. WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Lyon: IARC; 2007.

Korshunov A, Remke M, Gessi M, Ryzhova M, Hielscher T, Witt H, et al. Focal genomic amplification at 19q13.42 comprises a powerful diagnostic marker for embryonal tumors with ependymoblastic rosettes. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:253–60.

Kleinman CL, Gerges N, Papillon-Cavanagh S, Sin-Chan P, Pramatarova A, Quang DA, et al. Fusion of TTYH1 with the C19MC microRNA cluster drives expression of a brain-specific DNMT3B isoform in the embryonal brain tumor ETMR. Nat Genet. 2014;46:39–44.

Korshunov A, Sturm D, Ryzhova M, Hovestadt V, Gessi M, Jones DT, et al. Embryonal tumor with abundant neuropil and true rosettes (ETANTR), ependymoblastoma, and medulloepithelioma share molecular similarity and comprise a single clinicopathological entity. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:279–89.

Spence T, Sin-Chan P, Picard D, Barszczyk M, Hoss K, Lu M, et al. CNS-PNETs with C19MC amplification and/or LIN28 expression comprise a distinct histogenetic diagnostic and therapeutic entity. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:291–303.

Weingart MF, Roth JJ, Hutt-Cabezas M, Busse TM, Kaur H, Price A, et al. Disrupting LIN28 in atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors reveals the importance of the mitogen activated protein kinase pathway as a therapeutic target. Oncotarget. 2015;6:3165–77.

Sturm D, Orr BA, Toprak UH, et al. New brain tumor entities emerge from molecular classification of CNS-PNETs. Cell. 2016;164:1060–72.

Korshunov A, Golanov A, Sycheva R, Timirgaz V. The histologic grade is a main prognostic factor for patients with intracranial ependymomas treated in the microneurosurgical era: an analysis of 258 patients. Cancer. 2003;100:1230–7.

Tihan T, Zhou T, Holmes E, Burger PC, Ozuysal S, Rushing EJ. The prognostic value of histological grading of posterior fossa ependymomas in children: a Children’s Oncology Group study and a review of prognostic factors. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:165–77.

Zawrocki A, Izycka-Swieszewska E, Papierz W, Liberski PP, Zakrzewski K, Biernat W. Analysis of the prognostic significance of selected morphological and immunohistochemical markers in ependymomas, with literature review. Folia Neuropathol. 2011;49:94–102.

Ernestus RI, Schroder R, Stutzer H, Klug N. The clinical and prognostic relevance of grading in intracranial ependymomas. Br J Neurosurg. 1997;11:421–8.

Figarella-Branger D, Civatte M, Bouvier-Labit C, Gouvernet J, Gambarelli D, Gentet JC, et al. Prognostic factors in intracranial ependymomas in children. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:605–13.

Pajtler KW, Witt H, Sill M, Jones DT, Hovestadt V, Kratochwil F, et al. Molecular classification of ependymal tumors across all CNS compartments, histopathological grades, and age groups. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:728–43.

Palm T, Figarella-Branger D, Chapon F, Lacroix C, Gray F, Scaravilli F, et al. Expression profiling of ependymomas unravels localization and tumor grade-specific tumorigenesis. Cancer. 2009;115:3955–68.

Taylor MD, Poppleton H, Fuller CE, Su X, Liu Y, Jensen P, et al. Radial glia cells are candidate stem cells of ependymoma. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:323–35.

Pietsch T, Wohlers I, Goschzik T, Dreschmann V, Denkhaus D, Dorner E, et al. Supratentorial ependymomas of childhood carry C11orf95-RELA fusions leading to pathological activation of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127:609–11.

Parker M, Mohankumar KM, Punchihewa C, Weinlich R, Dalton JD, Li Y, et al. C11orf95-RELA fusions drive oncogenic NF-kappaB signalling in ependymoma. Nature. 2014;506:451–5.

Figarella-Branger D, Lechapt-Zalcman E, Tabouret E, et al. Supratentorial clear cell ependymomas with branching capillaries demonstrate characteristic clinicopathological features and pathological activation of nuclear factor-kappaB signaling. Neuro Oncol. 2016:Jul;18(7):919–27.

Witt H, Mack SC, Ryzhova M, Bender S, Sill M, Isserlin R, et al. Delineation of two clinically and molecularly distinct subgroups of posterior fossa ependymoma. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:143–57.

Wani K, Armstrong TS, Vera-Bolanos E, Raghunathan A, Ellison D, Gilbertson R, et al. A prognostic gene expression signature in infratentorial ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:727–38.

Hoffman LM, Donson AM, Nakachi I, Griesinger AM, Birks DK, Amani V, et al. Molecular sub-group-specific immunophenotypic changes are associated with outcome in recurrent posterior fossa ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127:731–45.

Mack SC, Witt H, Piro RM, Gu L, Zuyderduyn S, Stutz AM, et al. Epigenomic alterations define lethal CIMP-positive ependymomas of infancy. Nature. 2014;506:445–50.

Bayliss J, Mukherjee P, Lu C, Jain SU, Chung C, Martinez D, et al. Lowered H3K27me3 and DNA hypomethylation define poorly prognostic pediatric posterior fossa ependymomas. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:366ra161.

Collins VP, Jones DT, Giannini C. Pilocytic astrocytoma: pathology, molecular mechanisms and markers. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:775–88.

Dahiya S, Haydon DH, Alvarado D, Gurnett CA, Gutmann DH, Leonard JR. BRAF(V600E) mutation is a negative prognosticator in pediatric ganglioglioma. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:901–10.

Dias-Santagata D, Lam Q, Vernovsky K, Vena N, Lennerz JK,Borger DR, et al. BRAF V600E mutations are common in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17948.

Dougherty MJ, Santi M, Brose MS, Ma C, Resnick AC, Sievert AJ, et al. Activating mutations in BRAF characterize a spectrum of pediatric low-grade gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:621–30.

Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, Weller M. et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:997–1003.

Touat M, Idbaih A, Sanson M, Ligon KL. Glioblastoma targeted therapy: updated approaches from recent biological insights. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1457–72.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fuller, C. A little piece of mind: best practices for brain tumor intraoperative consultation. Mod Pathol 32 (Suppl 1), 44–57 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0147-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0147-y