Abstract

Collapsing glomerulopathy has been described in settings of viral infections, drug, genetic, ischemic, renal transplant, and idiopathic conditions. It has a worse prognosis than other morphologic variants of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and may be treated with aggressive immunosuppression. In this study, we sought to characterize the clinical and morphologic findings in older adults with collapsing glomerulopathy. Renal biopsies and associated clinical data from patients aged 65 or older with a diagnosis of collapsing glomerulopathy were retrospectively reviewed at 3 academic institutions. Patients (n = 41, 61% male, median age 71) usually had hypertension (88%), nephrotic range proteinuria (91%), and renal insufficiency (median serum creatinine 2.5 mg/dL). A likely precipitating drug (5%) or vascular procedure (5%) was identified in a minority of cases; viral infections were infrequent. Renal biopsies contained a median of 40% globally and 16% segmentally sclerotic glomeruli. Approximately 60% of cases had moderate or severe arteriosclerosis, arteriolar hyalinosis, and/or tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis; 7% had atheroembolic disease and 5% had thrombotic microangiopathy. In 28 patients with available follow-up information, eight (19%) were treated with immunosuppressives, which were not tolerated by 2. At a median interval of 14 months, 5 (18%) patients had died, 12 (43%) had end stage renal disease, and 12 were alive with renal insufficiency and proteinuria. Treatment with immunosuppressive therapy did not have a significant benefit with regard to the primary outcome of overall or renal survival. One steroid-treated patient with diabetes died 6 weeks after biopsy, with invasive rhinoorbital Rhizopus infection. In conclusion, collapsing glomerulopathy in older patients is usually not associated with viral infections, and is accompanied by significant chronic injury in glomeruli, vasculature, and tubulointerstitium. Aggressive immunosuppression likely contributed to one death in a patient with diabetes, and did not yield an overall or renal survival advantage in this cohort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

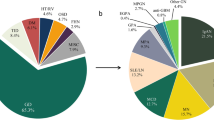

Collapsing glomerulopathy is a morphologic pattern of injury characterized by glomerular capillary tuft collapse, severe podocyte injury and epithelial cell proliferation; it is seen in the setting of infection, genetic conditions, and in physical or chemical-related injury [1, 2]. The collapsing variant of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis represents ~4.7% of biopsies with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis [3], and classically presents with nephrotic syndrome [4, 5] and renal insufficiency [1]. Collapsing glomerulopathy was described in association with human immunodeficiency virus [6, 7] and is increasingly recognized in the setting of other viral infections [8], genetic variants including APOL1 high-risk alleles [9, 10], drugs such as interferons [11] and bisphosphonates [12], thrombotic microangiopathy [13], atheroembolic disease [14], superimposed on diabetic nephropathy [15], and other glomerulopathies such as lupus nephritis [16]. In the renal allograft, collapsing glomerulopathy may be a recurrent or de novo disease [17,18,19,20], seen with significant vascular injury [21, 22] and/or regionally associated with segmental allograft infarction [23] (Table 1).

The pathologic diagnosis of collapsing glomerulopathy is based on the Columbia classification of at least one glomerulus with segmental collapse of the capillary tuft with associated hypertrophy and/or hyperplasia of the overlying podocytes and/or parietal epithelial cells [24,25,26]. Collapsing glomerulopathy has a poorer prognosis than other morphologic variants of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis [2, 27], and thus the inclination may be to treat with immunosuppressive therapy based on prior studies that show better renal outcomes for those in remission [28, 29]. Collapsing glomerulopathy has been reported in patients of a wide age range (13–77), yet patients tend to be young or middle age adults (age 30–40) at presentation [5]. Data regarding renal biopsies in older patients are limited [30, 31], and the clinical characteristics, histologic features, treatment, and outcome of older patients with collapsing glomerulopathy are not well-categorized. Herein, we sought to characterize the clinical and pathologic characteristics of collapsing glomerulopathy in older adults, aged 65 and above. Given the potentially different underlying etiology and risks associated with immunosuppression in the elderly, we also retrospectively analyzed outcomes by immunosuppression status.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at University of Washington, Oregon Health & Science University, and Stanford University, and adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki. Native kidney biopsies and associated clinical data from patients aged 65 or older with a renal biopsy diagnosis of collapsing glomerulopathy or focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with collapsing features from 2000 through 2016 were retrospectively reviewed. Nearly all cases with concurrent nephropathies were excluded except as follows: 1. two cases which also had features of acute and chronic endothelial injury/thrombotic microangiopathy were included; 2. seven cases of diabetic nephropathy with basement membrane thickening and diffuse mesangial sclerosis were included. Those with advanced diabetic nephropathy with nodular glomerulosclerosis were excluded. All biopsies had multiple levels cut and stained with Jones methenamine silver, periodic acid Schiff, hematoxylin and eosin, and trichrome for clinical purposes. For immunofluorescence microscopy, frozen tissue was stained with antibodies against IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, C1q, fibrin/fibrinogen, kappa light chain, lambda light chain, and albumin. Glomerular immunofluorescence staining intensity was scored on a scale of 0 to 4+ (University of Washington and Oregon Health & Science University) or 0–3+ (Stanford University). Electron microscopy was attempted in all cases and performed in 34, due to a lack of patent glomeruli in the remaining 7. In general, 2–4 glomeruli were examined ultrastructurally per case. Clinical data was procured from patient records and communication with nephrologists. Nephrotic-range proteinuria was defined as >3.5 g/day. Hypertension was based on clinical documentation of the word hypertension. Glomerular filtration was calculated using Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation [32]. Patients with no available follow-up information (n = 13, 32%) were excluded from the survival analyses, but included in the summary of biopsy findings. Primary outcome was overall or renal survival (time to dialysis or transplant). Statistical analyses were performed in Graphpad Prism 7 using non-parametric analyses and are provided as medians and ranges.

Results

Renal biopsies from 41 patients age 65 years or older (25 men, 16 women) were retrospectively identified. The median age was 71 (range 65–90) years, 88% had a history of hypertension, 91% had nephrotic range proteinuria, median serum creatinine at biopsy was 2.5 (range 1–5.9 mg/dL), with median estimated glomerular filtration rate of 22.7 (range 7.5–139.8 ml/min/1.72 m2). Of 24 patients with available ethnicity data, 15 (63%) were white, 4 (17%) were African American, 3 (13%) were Native American, and 2 (8%) were of Asian ancestry. Complete medication lists were unavailable for most patients at time of biopsy. Seven patients (17%) had a history of diabetes. Three patients (7%) had a history of infection including hepatitis C (n = 1), hepatitis B (n = 1), and recurrent urinary tract infections (n = 1). No patient had a diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus prior to biopsy, nor was this discovered on any patient with available follow-up information. Five patients (12%) had a diagnosis of malignancy, including prostate cancer (n = 2), hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 1), renal cell carcinoma status post nephrectomy (n = 1), and non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma (n = 1). Three patients (7%) had prior organ transplants (heart = 2, liver = 1 due to primary sclerosing cholangitis) and were on immunomodulating agents including cyclosporine, azathioprine, tacrolimus and/or mycophenolate mofetil. Two patients (5%) had drug exposure which may have contributed to collapsing glomerulopathy, including pamidronate (n = 1), and prior treatment with a vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor (n = 1). Two patients (5%) had a recent vascular surgical intervention which consisted of abdominal aortic aneurysm repair and stenting for renal artery stenosis (Table 2).

Renal biopsies contained a median of 15 (range 3–50) glomeruli for light microscopy, with a median of 40% global glomerulosclerosis (range 0–88%) and 16% segmentally sclerotic glomeruli (range 3–58%) (Table 3). At least one of the segmentally sclerotic glomeruli in each case had features of collapsing glomerulopathy (Fig. 1a). Nine biopsies also showed diffuse mesangial sclerosis, 7 (17%) of which represented at least mild diabetic glomerulopathy. Three biopsies (7%) had evidence of atheroembolic disease (Fig. 1b), including one from a patient with recent stenting for renal artery stenosis. Two biopsies (5%) showed a glomerular endothelial injury process consistent with thrombotic microangiopathy (Fig. 1c). One of these patients had been treated with a vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor, and the other had had a heart transplant and also had hyaline arteriolopathy consistent with calcineurin inhibitor toxicity. Immunofluorescence studies showed non-specific, focal and segmental staining in sclerotic glomeruli for IgM, C3 and/or C1q in 12 of the cases, and were otherwise without specific staining. By electron microscopy, 12 cases had diffuse podocyte foot process effacement (greater than 50% in all examined glomeruli), while 22 cases (65%) showed segmental glomerular podocyte foot process effacement. Eleven cases (27%) had histologic features of acute tubular injury. Moderate to severe interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy involved 68% of biopsies (Table 3). Moderate or severe arterial intimal sclerosis (59%) or arteriolar hyalinosis (54%) were common. Vasculitis was not identified in any of the cases.

a Collapsing glomerulopathy with segmental collapse of the capillary tuft and prominence of the overlying epithelial cells (400×, Jones stain), b cholesterol emboli in a larger caliber artery in a patient with atheroembolic disease (200×, Jones stain), and c chronic endothelial injury with subendothelial accumulation of electron lucent material, new matrix formation, and cellular interposition (transmission electron microscopy, 7100× )

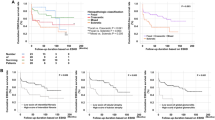

Follow up information was available in 28 (68%) patients. Eight (29%) were treated with immunosuppressive agents—including steroids [8], cyclosporine [2], and rituximab [1]. Steroids were not tolerated by 2 patients, one of whom experienced psychosis. In the single patient on pamidronate, the drug was discontinued. The three patients with prior organ transplants did not receive additional immunosuppression to treat collapsing glomerulopathy. Median time to last follow-up or primary outcome of overall or renal survival was 14 months (range 1–87). Five (18%) patients had died and 12 (43%) had end stage renal disease on dialysis (n = 10) or had received a transplant (n = 2). There was no significant difference in overall or renal survival between patients who were treated with immunosuppressive agents vs. those who were not (Fig. 2a). There were no statistically significant differences between patients who had reached the primary outcome vs. those who had not with regard to any of the evaluated clinical, laboratory, or renal biopsy findings—including degree of podocyte foot process effacement—nor in length of follow-up time (Mann–Whitney U tests). Nine of the 12 patients with diffuse podocyte foot process effacement by electron microscopy had available follow-up; of these, 6 reached the primary outcome and 3 were alive and not on dialysis. Of the 12 living patients who reached end stage renal disease, there was no significant difference in time to dialysis or transplant between those who had been treated with immunosuppressive agents vs. those who had not (Fig. 2b). Twelve patients (43%) were alive with renal insufficiency and proteinuria but without end stage renal disease. One patient with diabetes who received high dose steroids died 6 weeks after kidney biopsy, with invasive rhinoorbital Rhizopus infection. Other patients died of multifactorial or unknown causes.

a In 28 patients with collapsing glomerulopathy aged 65 and above, there were no differences in overall or renal survival between those who had been treated with immunosuppressives vs. those who had not. At median time to follow up or primary outcome (death or end stage renal disease) of 14 months, five (18%) patients had died and 12 (43%) had end stage renal disease on dialysis (n = 10) or had received a transplant (n = 2). b Of the 12 who were alive with end stage renal disease, there was no significant difference in time to dialysis or transplant between those who had been treated with immunosuppressives vs. those who had not

Discussion

This study is the largest cohort of older adults (age 65 and above) with collapsing glomerulopathy, and delineates the clinicopathologic features and outcomes of this renal biopsy finding. In summary, patients usually had a history of hypertension, nephrotic-range proteinuria, renal insufficiency, and advanced chronic injury in the glomeruli, vasculature, and tubulointerstitium. Unlike younger clinical cohorts of collapsing glomerulopathy, significant vascular injury was common and viral infections were infrequent. Aggressive immunosuppression likely contributed to one death in a patient with diabetes, and did not yield an overall or renal survival advantage in this cohort.

The findings from our study lend further support to the association between vascular disease and role of hemodynamics and ischemia in the pathogenesis of collapsing glomerulopathy in some patients. In a study of patients with proteinuria and antecedent vascular instrumentation who had biopsy proven cholesterol atheroembolic disease (n = 24), Greenberg et al. [14] found that 63% of these patients had focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; in those with nephrotic range proteinuria, this most often represented the collapsing variant. In study of 53 renal biopsies with thrombotic microangiopathy [13], 35.8% also had features of collapsing segmental sclerosis, and the authors suggested a critical role for endothelial injury as well as endothelial-podocyte crosstalk in the development of collapsing glomerulopathy in the setting of thrombotic microangiopathy. Collapsing glomerulopathy was also described in a study of severe diabetic nephropathy with advanced vascular disease in which the authors postulated a role for podocyte ischemia in the development of collapsing segmental sclerosis [15]. Similarly, de novo collapsing glomerulopathy in renal allografts has been associated with significant vascular disease [18, 21] and may have a regional distribution associated with vascular changes [22], and segmental allograft infarction [23]. These clinical observations are further supported by murine models of collapsing glomerulopathy which may be initiated and/or mediated by oxidative stress and podocyte autocrine/paracrine functions, in addition to human immunodeficiency virus-1 and immunoglobulins [2]. Our study expands on prior literature by demonstrating that in adults aged 65 and older with collapsing glomerulopathy, more than half have significant vascular disease in the form of moderate or severe arterial intimal sclerosis, and 12% had acute arterial vessel injury in the form of atheroembolic disease (7%) or thrombotic microangiopathy (5%).

The degree to which vascular and other chronic parenchymal injury is a cause of, contributor to, or result of collapsing glomerulopathy in older patients cannot be established in this observational study. Underlying arterionephrosclerosis is a common finding in biopsies from older patients; compared with one study of 109 patients aged 65 and older with acute post-infectious glomerulonephritis [33], biopsies in our cohort had a greater degree of global glomerulosclerosis (40 vs. 22%) and more patients had moderate or severe tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis (68 vs. 23%), akin to those previously reported in collapsing glomerulopathy [34]. A similar degree of moderate or severe arteriosclerosis and arteriolar hyalinosis were seen in both studies (61 vs. 66%). The incidence of atheroembolic disease and thrombotic microangiopathy observed in this study are also comparable to those reported in larger series of older patients who underwent renal biopsy [31, 35, 36]. It is plausible that the advanced tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis observed in our cohort predisposed the patients to glomerular injury [37], and that collapsing glomerulopathy in older patients represents a multifactorial phenomenon due at least in part to vascular injury/hemodynamic factors and tubuloglomerular interactions.

In older patients who generally have more comorbid conditions, there is very limited data to guide the use of immunosuppressive therapy in collapsing glomerulopathy. In the largest renal biopsy series of patients aged 80 years and older (n = 235), only 7.6% were diagnosed with secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis [31], and none with the collapsing variant. In younger patients, collapsing glomerulopathy has a poorer prognosis than other morphologic variants of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis [2, 27], and may be treated with aggressive immunosuppression which attenuates the poor prognosis [28], especially in those who achieve remission [29]. A review of multiple studies of human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients with collapsing glomerulopathy revealed a dismal complete remission rate of 9.6% and partial remission of 15.2% with immunosuppression [2], although remission rates as high as 65% have been reported [28]. In older adults, in a 1994 study Nagai et al. [38] assessed high-dose alternate day steroid therapy in a group of 61–78-year-old patients (n = 17) with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (subtypes not provided), followed for 30 months. Nine patients were treated with steroids or combination of glucocorticoids and cytotoxic therapy, 4 of whom went into remission. A recent case report documents an 81-year-old Japanese woman with collapsing glomerulopathy who was treated with steroids and cyclosporine; she experienced steroid-induced psychosis and died 3 months later [39]. In the current investigation, there was no overall or renal survival advantage with immunosuppressive therapy, and many of these cases likely represent a secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Pathologically, 65% of cases had segmental podocyte foot process effacement by ultrastructural studies, which has been associated with a “secondary” podocyte injury process/secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis [40], although the degree of reported podocyte foot process effacement in collapsing glomerulopathy varies from a mean of 80% [34] to only 38% [5] of cases showing diffuse podocyte foot process effacement. There were no statistically significant differences in outcomes based on degree of podocyte foot process effacement in our study. Thus our findings provide a rationale for not using immunosuppression in older adults with collapsing glomerulopathy. The small number of patients in this study—reflective of the low frequencies of both renal biopsies in older adults and collapsing segmental sclerosis—is not sufficient to identify those who may benefit from immunosuppressives vs. those who will not. In some clinical scenarios, such treatment may be beneficial.

Weaknesses of this study include the lack of complete clinical information regarding chronic diseases in these older patients, such as duration of diabetes, severity of hypertension, or presence of coronary artery or peripheral vascular disease, and complete medication histories. We do not have data regarding the exact timing or crescendo of clinical symptoms or signs and cannot retrospectively determine specific changes in the degree of proteinuria or renal insufficiency which prompted the biopsy. Finally, race and ethnicity were not well-documented for all archival cases, and we are unable to evaluate for the potential role of APOL1 risk alleles, which are an important mediator of collapsing glomerulopathy [9] and chronic kidney disease [41] in African Americans. However, of patients with available ethnicity data, 63% were white and 17% were African American, suggesting that APOL1 risk alleles may play a smaller epidemiologic role in collapsing glomerulopathy in patients aged 65 or older in the Pacific Northwest. These systemic factors would likely have contributed to a multifactorial pathogenesis of the collapsing glomerulopathy, and would also have influenced clinical treatment decisions in this cohort.

In conclusion, collapsing glomerulopathy in older patients is usually not associated with viral infections, and may be seen in the settings of morphologically advanced arterionephrosclerosis, recent invasive vascular procedures and/or atheroembolic phenomena, thrombotic microangiopathy, diabetic nephropathy, and drug exposure. It is accompanied by significant chronic injury in glomeruli, vasculature, and tubulointerstitium, and represents a secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in many cases. Aggressive immunosuppression likely contributed to one death, and did not yield an overall or renal survival advantage.

References

Haas M. Collapsing glomerulopathy: many means to a similar end. Kidney Int. 2008;73:669–71.

Albaqumi M, Soos TJ, Barisoni L, Nelson PJ. Collapsing glomerulopathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2854–63.

Haas M, Spargo BH, Coventry S. Increasing incidence of focal-segmental glomerulosclerosis among adult nephropathies: a 20-year renal biopsy study. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;26:740–50.

Detwiler RK, Falk RJ, Hogan SL, Jennette JC. Collapsing glomerulopathy: a clinically and pathologically distinct variant of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 1994;45:1416–24.

Laurinavicius A, Hurwitz S, Rennke HG. Collapsing glomerulopathy in HIV and non-HIV patients: a clinicopathological and follow-up study. Kidney Int. 1999;56:2203–13.

Rao TK, Filippone EJ, Nicastri AD, Landesman SH, Frank E, Chen CK, et al. Associated focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:669–73.

Cohen AH, Nast CC. HIV-associated nephropathy. A unique combined glomerular, tubular, and interstitial lesion. Mod Pathol. 1988;1:87–97.

Chandra P, Kopp JB. Viruses and collapsing glomerulopathy: a brief critical review. Clin Kidney J. 2013;6:1–5.

Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, Lecordier L, Uzureau P, Freedman BI, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329:841–5.

Larsen CP, Beggs ML, Saeed M, Walker PD. Apolipoprotein L1 risk variants associate with systemic lupus erythematosus-associated collapsing glomerulopathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:722–5.

Markowitz GS, Nasr SH, Stokes MB, D’Agati VD. Treatment with IFN-{alpha}, -{beta}, or -{gamma} is associated with collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:607–15.

ten Dam MA, Hilbrands LB, Wetzels JF. Nephrotic syndrome induced by pamidronate. Med Oncol. 2011;28:1196–200.

Buob D, Decambron M, Gnemmi V, Frimat M, Hoffmann M, Azar R, et al. Collapsing glomerulopathy is common in the setting of thrombotic microangiopathy of the native kidney. Kidney Int. 2016;90:1321–31.

Greenberg A, Bastacky SI, Iqbal A, Borochovitz D, Johnson JP. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis associated with nephrotic syndrome in cholesterol atheroembolism: clinicopathological correlations. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:334–44.

Salvatore SP, Reddi AS, Chandran CB, Chevalier JM, Okechukwu CN, Seshan SV. Collapsing glomerulopathy superimposed on diabetic nephropathy: insights into etiology of an under-recognized, severe pattern of glomerular injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:392–9.

Salvatore SP, Barisoni LM, Herzenberg AM, Chander PN, Nickeleit V, Seshan SV. Collapsing glomerulopathy in 19 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus or lupus-like disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:914–25.

Clarkson MR, O’Meara YM, Murphy B, Rennke HG, Brady HR. Collapsing glomerulopathy-recurrence in a renal allograft. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:503–6.

Meehan SM, Pascual M, Williams WW, Tolkoff-Rubin N, Delmonico FL, Cosimi AB, et al. De novo collapsing glomerulopathy in renal allografts. Transplantation. 1998;65:1192–7.

Schachter ME, Monahan M, Radhakrishnan J, Crew J, Pollak M, Ratner L, et al. Recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in the renal allograft: single center experience in the era of modern immunosuppression. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74:173–81.

Stokes MB, Davis CL, Alpers CE. Collapsing glomerulopathy in renal allografts: a morphological pattern with diverse clinicopathologic associations. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33:658–66.

Swaminathan S, Lager DJ, Qian X, Stegall MD, Larson TS, Griffin MD. Collapsing and non-collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in kidney transplants. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2607–14.

Nadasdy T, Allen C, Zand MS. Zonal distribution of glomerular collapse in renal allografts: possible role of vascular changes. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:437–41.

Canaud G, Bruneval P, Noel LH, Correas JM, Audard V, Zafrani L, et al. Glomerular collapse associated with subtotal renal infarction in kidney transplant recipients with multiple renal arteries. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:558–65.

D’Agati V. Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Semin Nephrol. 2003;23:117–34.

D’Agati V. The many masks of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 1994;46:1223–41.

D’Agati VD, Fogo AB, Bruijn JA, Jennette JC. Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a working proposal. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:368–82.

Schwimmer JA, Markowitz GS, Valeri A, Appel GB. Collapsing glomerulopathy. Semin Nephrol. 2003;23:209–18.

Laurin LP, Gasim AM, Derebail VK, McGregor JG, Kidd JM, Hogan SL, et al. Renal survival in patients with collapsing compared with not otherwise specified FSGS. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:1752–9.

Chun MJ, Korbet SM, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in nephrotic adults: presentation, prognosis, and response to therapy of the histologic variants. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2169–77.

Sumnu A, Gursu M, Ozturk S. Primary glomerular diseases in the elderly. World J Nephrol. 2015;4:263–70.

Moutzouris DA, Herlitz L, Appel GB, Markowitz GS, Freudenthal B, Radhakrishnan J, et al. Renal biopsy in the very elderly. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1073–82.

Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–70.

Nasr SH, Fidler ME, Valeri AM, Cornell LD, Sethi S, Zoller A, et al. Postinfectious glomerulonephritis in the elderly. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:187–95.

Valeri A, Barisoni L, Appel GB, Seigle R, D’Agati V. Idiopathic collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a clinicopathologic study. Kidney Int. 1996;50:1734–46.

Bomback AS, Herlitz LC, Markowitz GS. Renal biopsy in the elderly and very elderly: useful or not? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2012;19:61–7.

Nair R, Bell JM, Walker PD. Renal biopsy in patients aged 80 years and older. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:618–26.

Lim BJ, Yang JW, Zou J, Zhong J, Matsusaka T, Pastan I, et al. Tubulointerstitial fibrosis can sensitize the kidney to subsequent glomerular injury. Kidney Int. 2017;92:1395–403.

Nagai R, Cattran DC, Pei Y. Steroid therapy and prognosis of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in the elderly. Clin Nephrol. 1994;42:18–21.

Yamazaki J, Kanehisa E, Yamaguchi W, Kumagai J, Nagahama K, Fujisawa H. Idiopathic collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in an 81-year-old Japanese woman: a case report and review of the literature. CEN Case Rep. 2016;5:197–202.

Deegens JK, Dijkman HB, Borm GF, Steenbergen EJ, van den Berg JG, Weening JJ, et al. Podocyte foot process effacement as a diagnostic tool in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1568–76.

Limou S, Nelson GW, Kopp JB, Winkler CA. APOL1 kidney risk alleles: population genetics and disease associations. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014;21:426–33.

Nicholas Cossey L, Larsen CP, Liapis H. Collapsing glomerulopathy: a 30-year perspective and single, large center experience. Clin Kidney J. 2017;10:443–9.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the histology, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy staff at University of Washington, Oregon Health & Science University, and Stanford University, and to the referring nephrologists, radiologists, and pathologists who allow us to participate in the care of their patients. This work was presented in abstract form at the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology meeting in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada in March 2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kukull, B., Avasare, R.S., Smith, K.D. et al. Collapsing glomerulopathy in older adults. Mod Pathol 32, 532–538 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0154-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0154-z

This article is cited by

-

Pamidronic acid

Reactions Weekly (2019)