Abstract

The knowledge of clinical features and, particularly, histopathological spectrum of EWSR1-PATZ1-rearranged spindle and round cell sarcomas (EPS) remains limited. For this reason, we report the largest clinicopathological study of EPS to date. Nine cases were collected, consisting of four males and five females ranging in age from 10 to 81 years (average: 49 years). Five tumors occurred in abdominal wall soft tissues, three in the thorax, and one in the back of the neck. Tumor sizes ranged from 2.5 to 18 cm (average 6.6 cm). Five patients had follow-up with an average of 38 months (range: 18–60 months). Two patients had no recurrence or metastasis 19 months after diagnosis. Four patients developed multifocal pleural or pulmonary metastasis and were treated variably by surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. The latter seemed to have little to no clinical benefit. One of the four patients was free of disease 60 months after diagnosis, two patients were alive with disease at 18 and 60 months, respectively. Morphologically, low, intermediate, and high-grade sarcomas composed of a variable mixture of spindled, ovoid, epithelioid, and round cells were seen. The architectural and stromal features also varied, resulting in a broad morphologic spectrum. Immunohistochemically, the following markers were most consistently expressed: S100-protein (7/9 cases), GFAP (7/8), MyoD1 (8/9), Pax-7 (4/5), desmin (7/9), and AE1/3 (4/9). By next-generation sequencing, all cases revealed EWSR1-PATZ1 gene fusion. In addition, 3/6 cases tested harbored CDKN2A deletion, while CDKN2B deletion and TP53 mutation were detected in one case each. Our findings confirm that EPS is a clinicopathologic entity, albeit with a broad morphologic spectrum. The uneventful outcome in some of our cases indicates that a subset of EPS might follow a more indolent clinical course than previously appreciated. Additional studies are needed to validate whether any morphological and/or molecular attributes have a prognostic impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recurrent gene fusions between the EWSR1 or FUS gene and various members of the ETS transcription factor family (most commonly FLI1 or ERG) represent the molecular underpinnings of classic Ewing sarcoma. In contrast, the group traditionally referred to as ‘Ewing-like sarcomas’ and formally as undifferentiated round cell sarcomas in the 2013 WHO classification included round cell sarcomas with EWSR1-non-ETS fusions as well as round cell sarcomas with CIC and BCOR gene fusions [1]. However, the latest 2020 WHO classification of soft tissue and bone tumors recognized CIC- and BCOR-rearranged sarcomas each as separate, stand-alone entities and the remaining round cell sarcoma category was renamed ‘round cell sarcomas with EWSR1-non-ETS fusions [2].’ Nonetheless, it continues to incorporate provisional molecular entities whose clinicopathological features are in the early stages of elucidation. It currently includes sarcomas with EWSR1-NFATC2 and FUS-NFATC2 gene fusions as well as spindle and round cell sarcomas with EWSR1-PATZ1 gene fusion [2]. While multiple clinicopathological reports have been published recently on neoplasms with NFATC2 rearrangements [3,4,5,6], due to their extreme rarity, knowledge of clinical and, particularly, histopathological features of EWSR1-PATZ1-rearranged sarcomas (EPS) remains very limited. To improve our collective understanding of these unusual neoplasms, we report herein the largest clinicopathological study on systemic site EPS to date.

Materials and methods

The nine cases described in this study were retrieved from the consultation files of six institutions. Clinical information was abstracted from medical records, and follow-up data were obtained when possible. Only primary soft tissue tumors were included, central nervous system (CNS) neoplasms with EWSR1-PATZ1 fusion [7] were not included in this study. Paraffin blocks (1–3 from each case) were available for three cases and a limited number of unstained reserve slides were available in the remaining cases. A punch biopsy and miniscule (4 × 1–3 mm) incisional biopsy were available for cases 6 and 9, respectively. In case 7, only the pulmonary metastasis was available for analysis. Case 3 was published previously [8] but a more extensive histological and immunohistochemical characterization as well as updated follow-up information are provided in the current report.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical results for cases 2, 5–7 and 9 were provided by the respective contributing institutions. In cases 1, 3, 4, and 8 the immunohistochemical analysis was performed at the Department of Pathology, Charles University, Faculty of Medicine in Plzen using a Ventana BenchMark ULTRA (Ventana Medical System, Inc., Tucson, Arizona). The primary antibodies used in cases 1, 3, 4, and 8, their clone, dilution, and manufacturer are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Positive staining results were divided into four groups based on the percentage of positive tumor cells (focal: scattered positivity of individual cells (up to 5%); 1+: 6–33% positive cells; 2+: 34–66%; 3+:67–100%)

Molecular genetic studies

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Previously reported procedures for the detection of EWSR1 gene rearrangement and for the analysis of MDM2 gene amplification were employed [9, 10]. For EWSR1 gene FISH studies, 100 nuclei were scored, using 10% positive nuclei as a cut-off. The analysis was performed agnostic of the intrachromosomal translocation previously detected by next-generation sequencing (NGS). For the detection of CDKN2A deletion, factory premixed ZytoLight® SPEC CDKN2A/CEP9 Dual Color Probe (ZytoVysion Gmbh, Bremerhaven, Germany) was used. The FISH procedure was performed as previously described [11]. Samples were considered to possess a heterozygous deletion when the ratio between green (CDKN2A) and orange (CEP9) was equal to or less than 0.7 [12]. For homozygous deletion, samples were considered positive when >29% of nuclei exhibited loss of both green signals [13]. In cases 1 and 8, all 3 FISH analyses were performed, whereas in case 5 only EWSR1 FISH was done.

Detection of EWSR1-PATZ1 fusion and NGS methods

Cases 1, 2, 5, 8, and 9 were analyzed using three different customized versions of Archer FusionPlex Sarcoma kit (ArcherDX, Boulder, CO, USA) at the respective contributing institutions. All steps were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the libraries were sequenced on an Illumina platform as described previously [14]. Cases 3 and 7 were tested by a commercial NGS platform (Foundation Medicine, Cambridge, MA, USA) as reported elsewhere [15]. Cases 4 and 6 were analyzed using TruSight RNA fusion panel (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and massively parallel NGS platform, respectively, as described previously in detail [16, 17].

Results

Clinical findings

The clinical features are summarized in Table 1. There were four male and five female patients who ranged in age from 10 to 81 years (average: 49 years; mean: 46 years). The anatomic location of the tumors was available for all cases and included abdominal wall soft tissues (n = 5), thorax (2 cases in thoracic soft tissues, one in the lung), and subcutis in the back of the neck. Tumor sizes ranged from 2.5 to 18 cm in the greatest dimension, with an average and mean size of 6.6 and 5.9 cm, respectively. Patients in cases 1, 3, and 4 were treated only by a complete tumor resection (marginal excision in cases 1 and 3). A small incisional or punch biopsy was available for cases 6 and 9 and further treatment information was lacking. Surgery was part of multimodal therapy in cases 5, 7, and 8. Complete excision was achieved in case 7, while a small residual tumor focus was left behind in case 8. The status of surgical margins was unknown in case 5 as well as in case 2. Five patients had available follow-up with an average of 38 months (range: 18–60 months). Cases 1 and 3 had no evidence of the disease 19 months after surgery. Besides the 19 months of detailed follow-up for case 3, according to available records, the patient was alive 32 months after the operation (with an unknown disease status). The 10-year-old child in case 5 had a tumor involving the chest wall with parietal pleural nodules and visceral pleural implants on the lung and pericardium. The patient was given a chemotherapy protocol for Ewing sarcoma, followed by debulking procedures and rib resection. No effect of the chemotherapy was noted by imaging or histology. However, presumably owing to the aggressive surgical treatment, the patient was without disease 5 years after therapy. In case 7, multiple pulmonary metastases were detected 3 and 4 years after the diagnosis of her abdominal wall primary, which was initially treated by adjuvant radiation and surgery. The patient underwent right upper and middle lobe wedge resection and right lower lobectomy. She also started on chemotherapy (for details on chemotherapy regimens see Table 1) 4 years after the diagnosis. The patient was alive with a stable 4 mm lung nodule at last follow-up 5 years after diagnosis. Multiple pulmonary metastases were also detected in case 8. The patient received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (with no effect), followed by surgery and another round of chemotherapy with concomitant radiotherapy. This approach initially resulted in stable disease, but progression ensued 4 months later. The patient was alive with disease 18 months after treatment initiation and continued with another chemotherapy regimen (response yet unknown). The patient in case 9 had pulmonary metastases at presentation with no further follow-up available. Follow-up was also lacking for the recent cases 2, 4, and 6.

Pathological findings

The gross pathology characteristics were available for two cases. Case 1 was macroscopically well-circumscribed and had a tan-yellow color, lacking obvious necrotic foci (Fig. 1a). In contrast, the cut surface in case 8 showed a widely infiltrative tumor centered at the interface between skeletal muscle and subcutis. The neoplasm was predominantly gray–white in color with areas of necrosis (Fig. 2b).

Case 1 was macroscopically well circumscribed and had a tan-yellow color, lacking obvious necrotic foci (a). In contrast, the cut surface in case 8 showed a widely infiltrative tumor centered at the interface between skeletal muscle and subcutis. The neoplasm was predominantly gray–white in color with some areas of necrosis (b).

Tumors in this group were composed of a variable mixture of spindled, ovoid, round, and epithelioid cells. The cellularity was highly variable in different areas but was predominantly moderate (a, e). The stroma of these tumors was hyalinized (a, b, e, g). Case 2 contained abundant ropey collagen bundles (f, g). Both cases also contained an admixture of adipocytes (a, b, e, f) and an inconspicuous vasculature, distinguished only by isolated hemangiopericytoma-like vessels (a). The neoplastic cells showed mostly moderate variation in size and shape and their nuclei had predominantly bland nuclear features with fine chromatin (b, c, f). Case 2 contained infrequent giant cells (f). Low amount of lightly eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm was seen in most cells (b, f). However, variably prominent epithelioid cell population with a more ample clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm and collagen accentuation around cytoplasmic membranes was present in case 1 (c). Purely spindle cell areas were occasionally present in this case as well (d). Both cases vaguely resembled solitary fibrous tumor. Case 2 had also some features of spindle cell/pleomorphic lipoma.

At low power microscopy, the tumor in case 8 was infiltrative, whereas cases 1, 3, and 4 were (in the available tissue sections) relatively well-circumscribed and at least partially encapsulated by a variably thick fibrous tissue. In cases 2, 5, 6, 7, and 9 this parameter could not be assessed. The neoplasms formed either a single tumor mass (n = 6) or were divided by variably thick sclerotic bands into multiple uneven lobules. Based on the histological assessment of the neoplastic cells’ shape and nuclear grade, the nine tumors could be roughly divided into three morphologic subgroups. However, overlapping features between cases from different subgroups were often seen, confirming that the morphologic spectrum is continuous, and no precise boundaries can be drawn. In addition to figures provided in the manuscript, all nine tumors are comprehensively illustrated in Supplementary figures available online.

Low-grade spindle/round cell tumors

Tumors from the first subgroup, encompassing cases 1–4, are illustrated in Fig. 2 (cases 1 and 2) and Fig. 3 (cases 3 and 4). It included tumors composed of a variable mixture of spindled, ovoid, round, and epithelioid cells. The cellularity varied greatly in different areas but was predominantly moderate. Cases 3 and 4 had hypercellular stroma-poor areas consisting purely of relatively bland round cells with a low mitotic activity. The stroma of these tumors was otherwise hyalinized or focally myxohyaline. Cases 2 and 3 contained ropey collagen bundles, while cases 1 and 2 showed an admixture of adipocytes. Large pseudocystic spaces, some of them filled with an eosinophilic substance as well as areas with microcystic/reticular change were present in cases 3 and 4. The vasculature in cases 1 and 2 was inconspicuous and only isolated hemangiopericytoma-like vessels could be detected, while hyalinized small vessels were found in cases 3 and 4. The neoplastic cells showed moderate variation in size and shape. Case 2 contained infrequent giant cells. The nuclei of all cases had predominantly bland nuclear features with fine chromatin and 0–1 mitoses/10 high-power fields (HPF). The nucleoli were either inapparent or pinpoint-sized. Large nucleoli were rare. Scant, lightly eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm was seen in most cells. However, a variably prominent epithelioid cell population with more ample clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm was present in all four cases. Three cases also showed conspicuous eosinophilic collagen accentuation around cell membranes within these epithelioid areas. No necrosis was evident in any of the tumors. Overall, the four cases gave the impression of at most a low-grade sarcoma.

These tumors were also composed of a variable mixture of spindled, ovoid, round, and epithelioid cells. The cellularity was highly variable in different areas but was predominantly moderate (a, b, e, h). The stroma of these tumors was hyalinized (a, b, e, h) or focally myxohyaline (f). Case 3 contained abundant ropey collagen bundles (a). Case 4 showed multiple fibrocollagenous stromal bands (g) as well as large macro/microcystic areas (f). Both depicted cases contained innumerable small hyalinized vessels (a, i). The neoplastic cells showed mostly moderate variation in size and shape and their nuclei had predominantly bland nuclear features with fine chromatin (a, b, d, h, i). Both cases also exhibited very cellular stroma-poor areas consisting purely of relatively bland round cells with low mitotic activity (c, d, i). Occasionally, predominantly spindle cell areas were present (e). Low amount of lightly eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm was seen in most cells (a, d, e, i). However, variably prominent epithelioid cell population with a more ample clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm and collagen accentuation around cytoplasmic membranes was present in each case (b, h). Only very low mitotic activity (0–1 mitoses/10 HPF) was observed in all four neoplasms included in this subgroup (b).

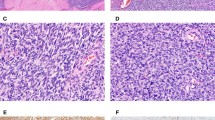

Predominantly round cell sarcomas

Cases 5–7 were included in the second subgroup and are illustrated in Fig. 4. They had predominantly round or ovoid cell morphology. In case 5, about two-thirds of the tumor showed minimal stromal matrix. Such foci consisted solely of solid sheets of round/ovoid cells that in some areas disintegrated to form minute empty spaces with a microcystic appearance or when more advanced, medium-sized pseudocysts similar to cases 3 and 4. The rest of the tumor showed more abundant hyaline stroma, focally with epithelioid cells again exhibiting a small amount of perimembranous collagen deposition. Most of the neoplastic cells were relatively uniform, had fine chromatin, small nucleoli and were thus akin to the round cells seen in the tumors from the first subgroup. However, a subset of cells in certain areas exhibited high-grade cytological features with hyperchromatic nuclei showing more variability in size and shape. Three mitoses per 10/HPF were identified. Necrosis was absent. Overall, case 5 was morphologically somewhere in between the low-grade tumors from the first subgroup and the high-grade round cell sarcomas in cases 6 and 7. Due to the scarcity of stromal matrix in case 6, only highly cellular sheets of relatively uniform round to oval cells with scant cytoplasm, hyperchromatic nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli were present. Spindle cells were rare. Five mitoses per 10 HPF were detected. Mildly hyalinized vessels occasionally with a staghorn shape were present. However, very little tissue was available and areas with a different appearance might have been unsampled. The pulmonary metastasis in case 7 exhibited an almost identical morphology, characterized by a monotonous proliferation of high-grade round cells with numerous small hyalinized vessels and one small necrotic focus. Six mitoses/10 HPF were present. A single markedly sclerotic area was the only other distinctive feature of this case.

All three cases had predominantly round or ovoid cell morphology. About two-thirds of the tumor in case 5 showed a very little stromal matrix (a, c, d). Such foci consisted only of solid sheets of round/ovoid cells (c, d) that in some areas disintegrated to form minute empty spaces with a microcystic appearance (c) or, when more advanced, medium-sized pseudocysts similar to cases 3 and 4 (a). The rest of the tumor showed more abundant hyaline stroma, focally with slightly epithelioid cells again exhibiting perimembranous collagen deposition (b). Most of the neoplastic cells were relatively uniform, had fine chromatin, small nucleoli and were thus akin to the round cells seen in the tumors from the previous subgroup (b, c). However, a subset of cells in certain areas exhibited high-grade cytological features with hyperchromatic nuclei and more variability in size and shape (d). Overall, this case was morphologically somewhere in between the low-grade tumors from the first subgroup and the high-grade round cell sarcomas in cases 6 and 7. Due to the scarcity of stromal matrix in case 6, only highly cellular sheets of relatively uniform round to oval cells with scanty cytoplasm, hyperchromatic nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli were present. Spindle cells were rare (e, f). Mildly hyalinized vessels, occasionally with a staghorn shape were present (e, f). The pulmonary metastasis in case 7 exhibited an almost identical morphology characterized by a monotonous proliferation of high-grade round cells with numerous small hyalinized vessels (g, i). A single markedly sclerotic area was the only other distinct feature found in this case (h).

High-grade spindle/round cell sarcomas

The third subgroup was represented by cases 8 and 9, which are illustrated in Fig. 5. Although the major cell type in both neoplasms was both spindle and round cells, the entire cellular population was relatively pleomorphic. The presence of variably thick sclerotic bands was a remarkable low power feature in both cases. They divided the tumors into multiple unevenly shaped neoplastic lobules or tumor nests. A small pre-treatment incisional biopsy was available for case 8. It showed abundant fibrocollagenous tissue infiltrated by a small round cell neoplasm (Supplementary figures, Fig. 8). In contrast, the post-chemotherapy resection specimen featured virtually all possible cell types including rhabdoid and epithelioid cells, the latter focally endowed with perimembranous collagen accentuation. Some areas again showed the microcystic/reticular change and hyalinized vessels. The cytologic features of both neoplasms were high-grade with pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei, including some bizarre multinucleated forms in case 8. The nucleoli of most cells were prominent in both cases. The mitotic rate was 6/10 HPF in the former and around 2–4/10 in the latter case but the smudged nuclei and low tissue amount in case 9 hampered accurate measurement. Case 8 showed a minor necrotic area which might, however, be attributable to neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Although the major cell type in both neoplasms in this group was a spindle and round cell, the whole cellular population was relatively pleomorphic (b–e, g). The presence of variably thick sclerotic bands was a remarkable low power feature in both cases. They divided the tumors into multiple unevenly shaped neoplastic lobules or tumor nests (a, f). Case 8 featured virtually all possible cell types including rhabdoid and epithelioid cells (b, e), the latter focally with perimembranous collagen accentuation as seen in the low-grade tumors (b). Some areas again showed microcystic/reticular change (c) and hyalinized vessels (d). The cytologic features of both neoplasms were high-grade with pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei (b-e, g). The nucleoli of most cells were prominent in both cases (b, e, g).

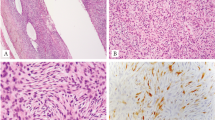

Immunohistochemical findings

The immunohistochemical results are summarized in Table 2 and illustrated in Fig. 6. In general, the staining was often heterogeneous among different portions of the tumors. As a result, areas with potentially positive staining might have been unsampled in cases 6 and 9 for which only limited tissue was available. The most consistent markers were S100-protein and GFAP, which were expressed at least focally in 7/9 and 7/8 cases, and skeletal muscle markers. Regarding the latter, the most reliable proved to be MyoD1, Pax-7, and desmin, which were positive in 8/9, 4/5, and 7/9 cases, respectively. In contrast, myogenin decorated a small percentage of cells in only 2/9 cases. Interestingly, broad-spectrum cytokeratins (AE1/3) showed a very discreet perinuclear staining of a subset of cells in 4/9 cases. Case 8 showed the same type of perinuclear expression and also exhibited cytoplasmic AE1/3 staining. OLIG2 showed diffuse, strong nuclear expression in 2/5 cases. While cytoplasmic WT1 staining was encountered 6/7 cases with the N-terminus antibody, nuclear expression was absent. The same staining pattern was present in 1 case tested with C-terminus antibody. One of three tested cases showed a near-complete loss of H3K27me2, one case showed partial loss, whereas intact expression was noted in the third case. CD34 and smooth muscle actin were mostly focally positive in 2/8 and 3/6 cases, respectively. Case 4 showed strong nuclear SOX-10 expression at the tumor periphery; all other six tested cases were negative. A minor subpopulation of neoplastic cells in 2/3 cases showed nuclear MDM2 staining. Synaptophysin and CD56 showed weak expression in 2/7 and 1/2 tested cases, respectively. Pan-TRK staining exhibited weak cytoplasmic positivity in 1/3 cases. H-caldesmon was diffusely positive in 1/2 cases. Conflicting results likely related to different antibodies and/or staining procedures employed were obtained for CD99. While all four cases stained at one institution were negative for CD99, results from other institutions ranged from negative, patchy membranous and/or cytoplasmic expression to diffuse and strong membranous staining detected in two cases. Negative results were obtained for all other tested markers which included EMA, 34ßE12, HMB45, BCOR, NKX2.2, NKX3.1, STAT6, SSX, SS18, chromogranin, calretinin, inhibin, ERG, CD31, TTF1, CD45, CD20, and CD3 (and some other markers tested in individual cases as listed Table 2). Ki-67 proliferation index ranged from 1% in cases 1 and 3 to 50% in case 8.

In general, the staining was very heterogeneous among different portions of the tumors (a, c). The most consistent markers were S100-protein (a), GFAP (b), desmin (c), MyoD1 (d), and Pax-7 (e). Interestingly, broad-spectrum cytokeratins (AE1/3) showed a very discreet perinuclear staining of a subset of cells in almost half of cases (g). Case 7 showed the same type of perinuclear expression and was the only case to also exhibit cytoplasmic AE1/3 staining (f). One of three tested cases showed a near complete loss of H3K27me2 (h). Strong diffuse nuclear OLIG2 staining (i).

Molecular genetic findings

FISH results

Three cases showed 8/100 nuclei with a break-apart signal using an EWSR1 break-apart probe and were rendered as negative for EWSR1 gene rearrangement. One case showed 9/100 nuclei with a break just falling short of the positive test result (10% cut-off) and was also rendered as negative. CDKN2A heterozygous and homozygous gene deletion were detected in cases 1 and 8, respectively. Both cases were negative for MDM2 gene amplification. A previously reported analysis of case 3 did not detect CDKN2A gene loss or MDM2 gene amplification [8].

Detection of EWSR1-PATZ1 fusion and NGS methods

Chromosome 22 harbored an intrachromosomal rearrangement between exon 8 (with or without part of intron 8 as noted previously [8]) and exon 1 of PATZ1 in all nine cases. Comprehensive DNA testing in case 6 also revealed a pathogenic TP53 (p.C275Y) gene mutation and low mutational burden (<5 mutations/Mb). Low tumor mutation burden was also detected in case 3 (2 mutation/Mb). NGS sequencing in case 7 detected CDKN2A/B gene loss, while cases 3, 4, and 6 were negative for this aberration. In cases 1, 2, 5, 8, and 9, these genes were not covered by the NGS panel used.

Discussion

Although the first case of this unique neoplasm was described 20 years ago [18], it was not until the recent advent of high-throughput NGS techniques when more cases of EPS began to appear in the literature. As of 2018, 18 more cases have been published [8, 19,20,21,22]. Combining our current data with those reported previously allows some general observations to be made.

Clinically, EPS have an equal gender distribution and occur over a very broad age range (1–81 years) with a mean age of 44 years. The most characteristic and diagnostically useful clinical feature of EPS is its marked predilection for soft tissues of the trunk, especially for thoracic soft tissues and/or lungs. In fact, 12 out of 25 reported cases with available data affected this anatomical area. Another eight cases occurred in the abdominal soft tissues (including both abdominal wall and intraabdominal sites) and 3 tumors involved the soft tissues of the head and neck. It is noteworthy that only 2/25 cases of EPS so far reported occurred on the limbs (thigh and shoulder) and none affected the skeleton [20, 23].

While a subset of EPS exhibits almost exclusively round cell morphology, similar to most other members within the most recent 2020 WHO classification category of “undifferentiated small round cell sarcomas of bone and soft tissue” (i.e., CIC-rearranged sarcoma, sarcoma with BCOR alterations, EWSR1/FUS-NFATC2-rearranged sarcomas) [2], EPS features variable mixture of spindled, ovoid, round, and epithelioid cells. The architectural and stromal features also vary and as a result, the morphologic spectrum is very broad. The nine cases in our cohort (and according to available figures probably all cases reported so far) could be roughly divided into three subgroups based on the predominant shape and nuclear grade of the neoplastic cells. While even then, the morphology within these subsets is not entirely homogeneous and the clinical impact of such subdivision is not known, we found this approach very useful for differential diagnostic purposes.

The first group included low-grade appearing tumors composed of spindled, ovoid, round, and epithelioid cells, which grew within predominantly hyaline stroma. These tumors were somewhat reminiscent of solitary fibrous tumors (when more spindled) or myoepitheliomas (when round/epithelioid cells predominated). The second group encompassed intermediate/high-grade tumors with a round or ovoid cell phenotype, few spindled cells and a less prominent stromal component. The differential diagnosis included other small round cell tumors. High-grade sarcomas with mixed spindled and round cell morphology were included in the last group. Rhabdomyosarcoma and sarcomas with BCOR and CIC gene rearrangements constitute the most likely differential diagnosis for these cases. It remains unclear whether the morphologically low-grade tumors can transform into the higher-grade variety or if the latter arise de novo. Two low-grade cases (cases 3 and 4) in our study showed areas with pure round cell morphology but the round cells were relatively bland and had low mitotic activity and a clear-cut transition to high-grade areas was not seen. However, the possibility of progression from lower-grade to higher-grade sarcoma with different morphology and prognosis cannot be excluded; albeit unusual it is a well-described feature of fusion-associated sarcomas and can be seen for example in myxoid/round cell liposarcomas. Despite the aforementioned differences, there were also several recurring traits shared by tumors across these categories, some of which were also noted previously [8, 19,20,21]. Besides the variability in cell shape, the most striking feature seen in six cases were variably thick bands of fibrocollagenous tissue, which divided the tumors into nests or lobules. Microcystic/macrocystic change and prominent hyalinized vessels represented another distinct feature and were found in 4 and 5 cases, respectively. A previously unreported feature present in 5 cases was situated in the epithelioid cell areas and consisted of perimembranous collagen accentuation, which emphasized the boundaries of individual cells. According to all available data, 9/14 cases had a mitotic count of less than 1 mitosis per 10 HPF, whereas the remaining cases showed 3–6 mitoses per 10 HPF [8, 19, 21]. In line with a predominantly low mitotic rate, necrosis was rare, with two cases showing a single small necrotic focus and only one reported case containing more prominent areas of necrosis [8].

The immunohistochemical features of EPS are unique and in contrast to morphology, they are much more consistent between individual cases. Our study corroborates findings of several previous reports, which found most EPS to stain with S100-protein, GFAP and with the myogenic markers desmin and MyoD1 [8, 19, 21]. A novel finding in this study was frequent Pax-7 expression detected in 4/5 analyzed cases. In contrast to a previous report, myogenin was the least sensitive skeletal muscle marker as it stained only 2/9 cases [19]. Another novel and diagnostically useful finding was dot-like perinuclear keratin expression detected with AE1/3 antibody in 4/9 cases. Only 1 other reported tumor was keratin positive, which is likely attributable to the great discreetness of this finding in most cases, as only 1 of the 4 positive tumors also showed more prominent cytoplasmic keratin staining [18].

EWSR1 and PATZ1 genes are both located on chromosome 22 only about 2 Mb apart and such a close genomic proximity results in significant visualization and interpretation difficulties of the break-apart FISH signals [2]. This was evidenced in our study by negative EWSR1 break-apart FISH results in all four cases tested. Therefore, other techniques such as NGS should be preferably used for molecular confirmation. The gene expression profiling analysis of small round cell sarcomas performed by Watson et al. showed EPS to form a distinct tight cluster, separate from all other tumors included in the study cohort [20]. These molecular data lend further support to suggest that EPS represents a unique entity, different from EWSR1/FUS-NFATC2 sarcomas or any other round cell tumor [19, 20]. However, the study did not include the recently described pediatric CNS tumors harboring an identical intrachromosomal fusion between exon 8 of EWSR1 and exon 1 of PATZ1 [7, 8, 24,25,26]. After reviewing the only two histologically documented cases of CNS tumors with EWSR1–PATZ1 fusion as well as one such case from our files, several similarities can be found [7]. The neoplastic cells also have spindled, round or epithelioid shape and are surrounded by hyalinized stroma and vessels. Co-expression of S100-protein and GFAP was found in 1/1 cases, and 2/2 cases showed staining with OLIG2 [7]. Since OLIG2 is a transcription factor involved in differentiation of cells in the oligodendroglial lineage, positive OLIG2 staining strongly suggests a primary CNS neoplasm [27]. Surprisingly, however, when stained with OLIG2, two out of five cases of EPS exhibited diffuse strong nuclear positivity as well. OLIG2 expression in sarcomas has not been investigated apart from a recent study reporting high OLIG2 specificity among rhabdomyosarcomas for alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas harboring PAX3/7-FOXO1 fusion [28, 29]. Nonetheless, along with other immunomorphological similarities, OLIG2 staining in some EPS supports the notion that the EWSR1-PATZ1 fusion event may give rise to identical neoplasms both in the CNS and elsewhere in the body, analogous to some other fusion-associated sarcomas such as Ewing sarcoma [30], CIC-rearranged sarcomas [31,32,33], or Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) [34]. However, further clinicopathological studies of the CNS neoplasms are necessary in this regard.

Due to variable spindle and/or round cell morphology with different levels of atypia, the complete list of differential diagnostic entities is extraordinarily broad. The co-expression of S100-protein, GFAP, desmin, and MyoD1 found in most cases of EPS is very unusual and therefore suggestive of the diagnosis. Nonetheless, some cases of EPS may lack this characteristic immunoprofile and in such cases, molecular detection of the fusion is required for diagnosis. Based on similar clinical, morphological, and/or immunohistochemical features, solitary fibrous tumor, myoepithelioma, desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT), Ewing sarcoma, BCOR or CIC-rearranged sarcomas, rhabdomyosarcoma and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) with skeletal muscle differentiation are among the entities most likely to be confused with EPS. Solitary fibrous tumor frequently arises on the pleura and may mimic low-grade examples of EPS. It also has a rare round cell variant that may be confused with the round cell subtype of EPS. Positivity with the above-mentioned markers in the absence of STAT6 expression strongly supports the diagnosis of EPS. Although typical Ewing sarcoma is composed of uniform round cells, the atypical variant may also show a partially spindle cell morphology [35]. EPS may occasionally show membranous CD99 expression but diffuse strong membranous expression typical for Ewing sarcoma is rare. While MyoD1 staining is absent in Ewing sarcoma, Pax-7 is consistently expressed [36]. Ewing sarcoma may also infrequently show focal expression of S100-protein or desmin but prominent co-expression of these two markers is not present [23, 35]. Both BCOR and CIC-rearranged sarcomas show variably spindled and round cell morphology. However, both are highly mitotically active tumors and do not generally express desmin and S100-protein, whereas BCOR sarcomas express BCOR and CIC-sarcomas show WT1 nuclear staining in most cases (with the N-terminus antibody) [37, 38]. It is not rare to encounter focal S100-protein expression in rhabdomyosarcomas but prominent co-expression of both S100-protein and GFAP in any rhabdomyosarcoma subtype would be very unusual [39]. Due to similarities in anatomical distribution, morphology and immunohistochemical features (desmin and keratin expression, including occasional dot-like expression of the latter [40]), DSRCT can closely mimic the morphologically high-grade subtype of EPS. Nevertheless, the fibrocollagenous bands in DSRCT are usually more prominent than in EPS. The tumor nests in DSRCT are also composed of more uniform cells, often with central necrosis, which is usually absent in EPS. Significant expression of S100-protein, GFAP, and of skeletal muscle markers such as MyoD1 is not present [41, 42]. The nuclear expression of the C-terminus WT1 antibody, which typifies DSRCT, was not present in the single case of EPS tested. Although exceedingly rare, MPNST with rhabdomyoblastic differentiation may look very similar to the high-grade spindle cell subtype of EPS, both morphologically and immunohistochemically. The history of type 1 neurofibromatosis, origin from a nerve or from a preexisting neurofibroma are features strongly favoring MPNST. Immunohistochemically, GFAP expression is rarely observed in MPNST [43, 44], whereas complete loss of histone H3K27me2 and/or H3K27me3 supports the diagnosis MPNST [19]. However, 1/3 EPS in our study showed almost a complete loss of H3K27me2 as well, questioning its reliability. Interestingly, Benini et al. recently reported a case of MPNST with rhabdomyosarcomatous and chondrosarcomatous differentiation harboring a novel EWSR1-VEZF1 fusion [45]. This case showed a mixed spindle and round cell morphology and immunohistochemical positivity with desmin, myogenin, SOX10, and EMA, while being negative with S100-protein, GFAP, and AE1/3 [45]. Akin to PATZ1, VEZF1 gene also encodes a Cys2/His2-type zinc finger protein with transcriptional regulatory function, has a similar structure, and is considered a paralogue of PATZ1 [46, 47]. Very recently, another case of EWSR1-VEZF1 sarcoma was included (lacking details) in a large study of round cell sarcomas [22]. Given the morphologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic similarities, we believe that rather than MPNST, EWSR1-VEZF1 fusion-associated sarcomas might represent another round cell sarcoma with skeletal muscle differentiation, closely related to EPS. Nevertheless, more cases of this exceedingly rare neoplasm are again needed to support this conjecture.

Previous reports suggested very aggressive clinical behavior in most cases of EPS as 4/5 patients with follow-up either died or experienced distant metastasis within 2–30 months. The only patient with follow-up (19 months) that was alive without any adverse event was an 81-year-old female in a study by Bridge et al. [8]. This case was also included in the current report (case 3) and although no further clinical examination has been performed since the previous study, per available data, the patient is alive at 32 months from the initial diagnosis. Importantly, Bridge et al. performed comprehensive DNA and RNA sequencing, which revealed copy number loss or deletion of CDKN2A/CDKN2B genes and MDM2 gene amplification in 2/2 and 1/2 cases with fatal outcome, respectively. In contrast, none of these changes were found in the single case with a favorable clinical course. In our study, the two high-grade sarcomas in cases 7 and 8 harbored CDKN2A/B gene loss (unknown whether homozygous or heterozygous) in case 7, whereas homozygous CDKN2A gene deletion was observed in case 8. However, a heterozygous gene deletion was also seen in the morphologically low-grade case 1 with 19 months of uneventful follow-up. Moreover, the 18 cm large and morphologically malignant case 6 lacked any CDKN2A/B gene aberrations by NGS. On the other hand, this case harbored TP53 gene mutation, which might also have a potential prognostic relevance.

Apart from secondary molecular abnormalities, our data indicate that certain morphological features might be associated with a more favorable prognosis. The above-discussed case 3 as well as case 1 were both well-circumscribed, partially encapsulated tumors with negligible mitotic activity and similar low-grade morphology. Both tumors were completely excised, and the patients were free of disease 19 months after initial diagnosis. Notably, neither of them received any adjuvant therapy. However, despite intermediate-grade morphology, higher mitotic activity (3 mitoses/10 HPF) and widespread parietal and visceral pleural involvement at presentation, the patient in case 5 was free of disease 5 years after tumor resection. Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered as well but no response was noted by imaging or histology. Similarly, chemotherapy in four other published cases and in the aggressive case 8 in the current study showed little to no clinical benefit [8, 19]. The role of chemotherapy remains unclear in case 7 where chemotherapy was administered after the resection of multiple lung metastases. The patient was alive with a single 4-mm nonprogressive pulmonary nodule after 1 year.

In summary, we have presented the largest clinicopathological analysis of EPS to date, which confirms these tumors to have a very wide morphological spectrum with recurrent microscopic features. They also have a characteristic immunophenotype distinguished mainly by the co-expression of neural (S100-protein, GFAP) and skeletal muscle (desmin, MyoD1, Pax-7) markers in most cases. Both findings, as well as gene expression data from previous studies confirm that EPS is a distinct clinicopathologic entity which may also include the CNS tumors harboring EWSR1-PATZ1 fusion. The uneventful outcome in some of our cases indicate that a subset of EPS might follow a more indolent clinical course than previously appreciated. Additional studies with comprehensive clinical, morphological and molecular data are needed to validate whether any morphological and/or molecular attributes have a prognostic impact and to confirm whether chemotherapy has no clinical benefit for the patients.

Change history

10 June 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-021-00740-x

References

Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F. WHO classification of tumors of soft tissue and bone. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC; 2013.

Antonescu CR, Bridge JA, Cunha IW, Dei Tos AP, Fletcher CDM, Folpe AL, et al. WHO Classification of soft tissue and bone tumors. 5th ed. Lyon: IARC; 2020.

Szuhai K, Ijszenga M, de Jong D, Karseladze A, Tanke HJ, Hogendoorn PC. The NFATc2 gene is involved in a novel cloned translocation in a Ewing sarcoma variant that couples its function in immunology to oncology. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2259–68.

Wang GY, Thomas DG, Davis JL, Ng T, Patel RM, Harms PW, et al. EWSR1-NFATC2 translocation-associated sarcoma clinicopathologic findings in a rare aggressive primary bone or soft tissue tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:1112–22.

Bode-Lesniewska B, Fritz C, Exner GU, Wagner U, Fuchs B. EWSR1-NFATC2 and FUS-NFATC2 gene fusion-associated mesenchymal tumors: clinicopathologic correlation and literature review. Sarcoma. 2019;2019:9386390.

Kinkor Z, Vanecek T, Svajdler M Jr., Mukensnabl P, Vesely K, Baxa J, et al. [Where does Ewing sarcoma end and begin—two cases of unusual bone tumors with t(20;22)(EWSR1-NFATc2) alteration]. Cesk Patol. 2014;50:87–91.

Siegfried A, Rousseau A, Maurage CA, Pericart S, Nicaise Y, Escudie F, et al. EWSR1-PATZ1 gene fusion may define a new glioneuronal tumor entity. Brain Pathol. 2019;29:53–62.

Bridge JA, Sumegi J, Druta M, Bui MM, Henderson-Jackson E, Linos K, et al. Clinical, pathological, and genomic features of EWSR1-PATZ1 fusion sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:1593–604.

Michal M, Berry RS, Rubin BP, Kilpatrick SE, Agaimy A, Kazakov DV, et al. EWSR1-SMAD3-rearranged fibroblastic tumor: an emerging entity in an increasingly more complex group of fibroblastic/myofibroblastic neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1325–33.

Michal M, Agaimy A, Contreras AL, Svajdler M, Kazakov DV, Steiner P, et al. Dysplastic lipoma: a distinctive atypical lipomatous neoplasm with anisocytosis, focal nuclear atypia, p53 overexpression, and a lack of MDM2 gene amplification by FISH; a report of 66 cases demonstrating occasional multifocality and a rare association with retinoblastoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1530–40.

Steiner P, Andreasen S, Grossmann P, Hauer L, Vanecek T, Miesbauerova M, et al. Prognostic significance of 1p36 locus deletion in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands. Virchows Arch. 2018;473:471–80.

Mohapatra G, Betensky RA, Miller ER, Carey B, Carey B, et al. Glioma test array for use with formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue: array comparative genomic hybridization correlates with loss of heterozygosity and fluorescence in situ hybridization. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:268–76.

Gerami P, Li G, Pouryazdanparast P, Blondin B, Beilfuss B, Slenk C, et al. A highly specific and discriminatory FISH assay for distinguishing between benign and malignant melanocytic neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:808–17.

Svajdler M, Michal M, Martinek P, Ptakova N, Kinkor Z, Szepe P, et al. Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of digits and myositis ossificans show consistent COL1A1-USP6 rearrangement: a clinicopathological and genetic study of 27 cases. Hum Pathol. 2019;88:39–47.

Frampton GM, Fichtenholtz A, Otto GA, Wang K, Downing SR, He J, et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:1023–31.

Agaimy A, Tögel L, Haller F, Zenk J, Hornung J, Märkl B. YAP1-NUTM1 Gene Fusion in Porocarcinoma of the External Auditory Canal. Head and Neck Pathol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-020-01173-9.

Vanderwalde A, Spetzler D, Xiao N, Gatalica Z, Marshall J. Microsatellite instability status determined by next-generation sequencing and compared with PD-L1 and tumor mutational burden in 11,348 patients. Cancer Med. 2018;7:746–56.

Mastrangelo T, Modena P, Tornielli S, Bullrich F, Testi MA, Mezzelani A, et al. A novel zinc finger gene is fused to EWS in small round cell tumor. Oncogene. 2000;19:3799–804.

Chougule A, Taylor MS, Nardi V, Chebib I, Cote GM, Choy E, et al. Spindle and round cell sarcoma with EWSR1-PATZ1 gene fusion: a sarcoma with polyphenotypic differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:220–8.

Watson S, Perrin V, Guillemot D, Reynaud S, Coindre JM, Karanian M, et al. Transcriptomic definition of molecular subgroups of small round cell sarcomas. J Pathol. 2018;245:29–40.

Park KW, Cai Y, Benjamin T, Qorbani A, George J. Round cell sarcoma with EWSR1-PATZ1 gene fusion in the neck: case report and review of the literature. Laryngoscope. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28554.

Tsuda Y, Zhang L, Meyers P, Tap WD, Healey JH, Antonescu CR. The clinical heterogeneity of round cell sarcomas with EWSR1/FUS gene fusions. impact of gene fusion type on clinical features and outcome. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2020;59:525–34.

Antonescu C. Round cell sarcomas beyond Ewing: emerging entities. Histopathology. 2014;64:26–37.

Alvarez-Breckenridge C, Miller JJ, Nayyar N, Gill CM, Kaneb A, D’Andrea M, et al. Clinical and radiographic response following targeting of BCAN-NTRK1 fusion in glioneuronal tumor. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2017;1:5.

Johnson A, Severson E, Gay L, Vergilio JA, Elvin J, Suh J, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of 282 pediatric low- and high-grade gliomas reveals genomic drivers, tumor mutational burden, and hypermutation signatures. Oncologist. 2017;22:1478–90.

Qaddoumi I, Orisme W, Wen J, Santiago T, Gupta K, Dalton JD, et al. Genetic alterations in uncommon low-grade neuroepithelial tumors: BRAF, FGFR1, and MYB mutations occur at high frequency and align with morphology. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:833–45.

Zhou Q, Wang S, Anderson DJ. Identification of a novel family of oligodendrocyte lineage-specific basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors. Neuron. 2000;25:331–43.

Kaleta M, Wakulińska A, Karkucińska-Więckowska A, Dembowska-Bagińska B, Grajkowska W, Pronicki M, et al. OLIG2 is a novel immunohistochemical marker associated with the presence of PAX3/7-FOXO1 translocation in rhabdomyosarcomas. Diagnostic Pathol. 2019;14:103.

Raghavan SS, Mooney KL, Folpe AL, Charville GW. OLIG2 is a marker of the fusion protein-driven neurodevelopmental transcriptional signature in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Hum Pathol. 2019;91:77–85.

Chen J, Jiang Q, Zhang Y, Yu Y, Zheng Y, Chen J, et al. Clinical features and long-term outcome of primary intracranial Ewing sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors: 14 cases from a single institution. World Neurosurg. 2019;122:e1606–e1614.

Bielle F, Zanello M, Guillemot D, Gil-Delgado M, Bertrand A, Boch AL, et al. Unusual primary cerebral localization of a CIC-DUX4 translocation tumor of the Ewing sarcoma family. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:309–11.

Ito M, Ishikawa M, Kitajima M, Narita J, Hattori S, Endo O, et al. A case report of CIC-rearranged undifferentiated small round cell sarcoma in the cerebrum. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:828–32.

Sturm D, Orr BA, Toprak UH, Hovestadt V, Jones DTW, Capper D, et al. New brain tumor entities emerge from molecular classification of CNS-PNETs. Cell. 2016;164:1060–72.

Lee JC, Villanueva-Meyer JE, Ferris SP, Cham EM, Zucker J, Cooney T, et al. Clinicopathologic and molecular features of intracranial desmoplastic small round cell tumors. Brain Pathol. 2020;30:213–25.

Folpe AL, Goldblum JR, Rubin BP, Shehata BM, Liu W, Dei Tos AP, et al. Morphologic and immunophenotypic diversity in Ewing family tumors: a study of 66 genetically confirmed cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1025–33.

Charville GW, Wang WL, Ingram DR, Roy A, Thomas D, Patel RM, et al. EWSR1 fusion proteins mediate PAX7 expression in Ewing sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:1312–20.

Yamada Y, Kuda M, Kohashi K, Yamamoto H, Takemoto J, Ishii T, et al. Histological and immunohistochemical characteristics of undifferentiated small round cell sarcomas associated with CIC-DUX4 and BCOR-CCNB3 fusion genes. Virchows Arch. 2017;470:373–80.

Antonescu CR, Owosho AA, Zhang L, Chen S, Deniz K, Huryn JM, et al. Sarcomas With CIC-rearrangements are a distinct pathologic entity with aggressive outcome: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 115 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:941–9.

Karamchandani JR, Nielsen TO, van de Rijn M, West RB. Sox10 and S100 in the diagnosis of soft-tissue neoplasms. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2012;20:445–50.

Thway K, Noujaim J, Zaidi S, Miah AB, Benson C, Messiou C, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: pathology, genetics, and potential therapeutic strategies. Int J Surg Pathol. 2016;24:672–84.

Ordonez NG. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: II: an ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study with emphasis on new immunohistochemical markers. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1314–27.

Mohamed M, Gonzalez D, Fritchie KJ, Swansbury J, Wren D, Benson C, et al. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: evaluation of reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization as ancillary molecular diagnostic techniques. Virchows Arch. 2017;471:631–40.

Kawahara E, Oda Y, Ooi A, Katsuda S, Nakanishi I, Umeda S. Expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in peripheral nerve sheath tumors. A comparative study of immunoreactivity of GFAP, vimentin, S-100 protein, and neurofilament in 38 schwannomas and 18 neurofibromas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:115–20.

Gray MH, Rosenberg AE, Dickersin GR, Bhan AK. Glial fibrillary acidic protein and keratin expression by benign and malignant nerve sheath tumors. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:1089–96.

Benini S, Gamberi G, Cocchi S, Righi A, Frisoni T, Longhi A, et al. Identification of a novel fusion transcript EWSR1-VEZF1 by anchored multiplex PCR in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Pathol Res Pract. 2020;216:152760.

Xiong JW, Leahy A, Lee HH, Stuhlmann H. Vezf1: a Zn finger transcription factor restricted to endothelial cells and their precursors. Dev Biol. 1999;206:123–41.

Genecards—the human gene database (database online). VEZF1 gene. 2020 https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=VEZF1.

Acknowledgements

Supported in parts by the National Sustainability Program I (NPU I) Nr. LO1503 and by the grant SVV-2020 No. 260 391 provided by the Ministry of Education Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic. The authors would like to thank Zuzana Špůrková M.D. for providing follow-up information on one of the patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics

The study was conducted following the rules set by the Faculty Hospital in Pilsen Ethics Committee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: There was an error in an author name.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Michal, M., Rubin, B.P., Agaimy, A. et al. EWSR1-PATZ1-rearranged sarcoma: a report of nine cases of spindle and round cell neoplasms with predilection for thoracoabdominal soft tissues and frequent expression of neural and skeletal muscle markers. Mod Pathol 34, 770–785 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-00684-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-00684-8

This article is cited by

-

Gene fusion–driven cutaneous mesenchymal neoplasms: An updated review emphasizing the emerging entities

Virchows Archiv (2026)

-

The role of the transcription factor PATZ1 in tumorigenesis and metabolic regulation

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2025)

-

Emerging round cell sarcomas in children

Virchows Archiv (2025)

-

Pediatric thyroid-like follicular renal cell carcinoma—a post-neuroblastoma case with comprehensive genomic profiling data

Virchows Archiv (2024)

-

A novel LARGE1-AFF2 fusion expanding the molecular alterations associated with the methylation class of neuroepithelial tumors with PATZ1 fusions

Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2022)