Abstract

JAK2, CALR, and MPL are myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN)-driver mutations, whereas SF3B1 is strongly associated with ring sideroblasts (RS) in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). Concomitant mutations of SF3B1 and MPN-driver mutations out of the context of MDS/MPN with RS and thrombocytosis (MDS/MPN-RS-T) are not well-studied. From the cases (<5% blasts) tested by NGS panels interrogating at least 42 myeloid neoplasm-related genes, we identified 18 MDS/MPN-RS-T, 42 MPN, 10 MDS, and 6 MDS/MPN-U cases with an SF3B1 and an MPN-driver mutation. Using a 10% VAF difference to define “SF3B1-dominant,” “MPN-mutation dominant,” and “no dominance,” the majority of MDS/MPN-RS-T clustered in “SF3B1-dominant” and “no dominance” regions. Aside from parameters as thrombocytosis and ≥15% RS required for RS-T, MDS also differed in frequent neutropenia, multilineage dysplasia, and notably more cases with <10% VAF of MPN-driver mutations (60%, p = 0.0346); MPN differed in more frequent splenomegaly, myelofibrosis, and higher VAF of “MPN-driver mutations.” “Gray zone” cases with features overlapping MDS/MPN-RS-T were observed in over one-thirds of non-RS-T cases. This study shows that concomitant SF3B1 and MPN-driver mutations can be observed in MDS, MPN, and MDS/MPN-U, each showing overlapping but also distinctively different clinicopathological features. Clonal hierarchy, cytogenetic abnormalities, and additional somatic mutations may in part contribute to different disease phenotypes, which may help in the classification of “gray zone” cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Philadelphia-negative [Ph(−)] myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are a heterogeneous group of bone marrow stem cell diseases characterized by overproduction of erythroid, myeloid, and/or megakaryocytic cells [1, 2]. In contrast, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis, defined by cytopenia(s) and dysplasia. Myeloid neoplasms with hybrid features of MDS and MPN are recognized as a separate category (MDS/MPNs), which first grouped together in the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of hematopoietic neoplasms [3].

The classification of myeloid neoplasms has traditionally relied on laboratory and cytogenetic features as well as bone marrow morphology. One hallmark of the Ph(−) MPNs is a proliferation of large, pleomorphic, and often clustered megakaryocytes in the bone marrow. In contrast, the megakaryocytes in MDS are typically small with hypolobated or completely dislocated nuclei. At least one hematopoietic lineage in MDS must show significant dysplasia, which includes presence of ring sideroblasts (RS) (the presence of five or more perinuclear siderotic granules surrounding at least one-third of the nucleus in erythroid precursors on Prussian blue iron staining). Conversely, dyserythropoiesis, dysgranulopoiesis, and MDS-type megakaryocytes are typically not observed in the MPN at the time of initial diagnosis [4].

With the advancement of next-generation sequencing (NGS) and its increased use in clinical practice, the mutational profiles of MDS, MPN, and MDS/MPN have been increasingly characterized [1, 5,6,7]. The mutation information has improved risk stratification and helped guide for therapies. Somatic mutations in the MPN-driver genes, JAK2, CALR, and MPL, are found in the majority of MPN cases and they are integrated into the current diagnostic criteria of Ph(−) MPN [8]. SF3B1 mutation has been strongly associated with the presence of RS in MDS as well as other myeloid neoplasms [9], and its presence has been incorporated into the WHO diagnostic criteria for MDS with RS (for cases with 5–14% RS).

MDS/MPN with RS and thrombocytosis (MDS/MPN-RS-T, henceforth RS-T) was first introduced as the provisional MDS/MPN entity and was named as refractory anemia with RS and marked thrombocytosis in the 2008 WHO classification scheme under the disease category of MDS/MPN, unclassifiable (MDS/MPN-U). It is now an official MDS/MPN entity in the 2016 revised 4th edition WHO classification. A diagnosis of RS-T requires the presence of anemia, ≥15% RS, persistent thrombocytosis (platelet count ≥450 × 109/L), no increase in blasts in peripheral blood or bone marrow, and lack of BCR-ABL1, PCM1-JAK2, rearrangement of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGFR1, t(3;3)(q21.3;q26.2), inv(3)(q21.3q26.2), or isolated del(5q). The recent discovery of frequent co-mutations of SF3B1 and JAK2 in RS-T were important in recognizing it as an official entity in the 2016 WHO Classification. The reported rate of SF3B1 in RS-T is 80–90% [10,11,12,13], while a JAK2 p.V617F, MPL, or CALR mutation is present in 50–60% [12, 14], 5–10%, and 5–10% [11, 12, 14, 15], respectively. Co-mutation of SF3B1 with JAK2, CALR, or MPL is frequent (~50% of cases) in RS-T [11, 12, 16]. According to the WHO Classification, a prior diagnosis of MPN, MDS, or other MDS/MPN excludes a diagnosis of RS-T, with the exception of evolution from previous MDS with RS (most often upon acquisition of mutations in JAK2, CALR, or MPL) [8]. Patients with RS-T tend to have a superior prognosis to MDS with RS as well as to the three other MDS/MPN that affect adults (MDS/MPN-U, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) and atypical CML, BCR-ABL1 negative) [17,18,19]. Thus, accurate diagnosis of this entity and distinction from other myeloid neoplasms is clinically relevant.

SF3B1 mutations are uncommon in Ph(−) MPN, with a reported rate of only 2–10% [5, 20, 21]. In one series, SF3B1 mutations occurred mainly in PMF and in the fibrotic phases of ET and PV [20]. Likewise, JAK2, CALR, or MPL mutations are extremely uncommon in MDS, being present in <5% of MDS cases and are also uncommon in MDS/MPN other than RS-T [6, 9, 22, 23]. The relationship of myeloid neoplasms bearing co-mutation of one of the MPN-driver genes with SF3B1 mutation to RS-T is uncertain; we questioned whether some cases that do not meet the strict WHO Classification criteria for RS-T may nevertheless lie within the biologic spectrum of this entity. To address this issue, we comprehensively reviewed SF3B1 and one of MPN-driver genes co-mutated myeloid neoplasms, including the clinical, laboratory, genetic, and bone marrow histopathological features. The mutation data were further analyzed by variant allele frequency (VAF) and correlated with clinicopathological characteristics.

Material and methods

Patients

We collected cases from the pathology archives at nine medical centers from 2016 to 2019: MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, University of Chicago, University of Utah/ARUP Laboratories, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Cleveland Clinic, Mayo Clinic, Weill-Cornell Medical College, and Massachusetts General Hospital. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of MDS, MPN, or MDS/MPN (including RS-T) with mutations in either JAK2, CALR, or MPL in addition to SF3B1 mutation. In order to appropriately compare to RS-T, we limited the study cohort to cases with no increase in BM (<5%) and/or PB (<2%) blasts. Due to their distinctive biologic characteristics, therapy-related myeloid neoplasms were excluded from this study. Cases of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), either de novo or secondary to previous MDS, MPN, or MDS/MPN, were also excluded. Clinical information was collected from the electronic medical records. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions.

Bone marrow morphology

Routine hematoxylin and eosin histologic sections of BM trephine biopsy specimens and well-prepared Wright–Giemsa-stained bone marrow aspirate smears were reviewed at participating institutions. A 500-nucleated cell differential cell count was performed in most cases. Perls’ reaction for iron was performed on BM aspirate smears in most of the cases, and RS were counted as the proportion of total nucleated red cells. Dysplasia was determined using the International Working Group on Morphology of MDS guidelines [24]. MDS-like megakaryocytes were megakaryocytes that were small, with either hypolobated/nonlobated nuclei or with completely dislocated/separated nuclear lobes. MPN-like megakaryocytes were those that exhibited clustering, large size, hyperchromatic nuclei, or were of variable sizes with bulbous/hypolobated and/or hyperlobulated/staghorn-shaped nuclei. When both MDS-like and MPN-like features were present (at least 30% of each), the megakaryocytes were considered as to have mixed MDS-like and MPN-like features. Myelofibrosis grade was assessed on reticulin-stained bone marrow biopsy sections according to the European Bone Marrow Fibrosis Consensus criteria [25]. The morphological criteria used had been standardized through prior discussion among the reviewers, including microscopic group review of selected sample cases to establish the definitions of each criterion. The cases were reviewed by the participants at their respective institutions, using a template to record the morphologic features and verified by CYO and SAW. Discrepancies/clarifications in a few cases were resolved by microscopic review at meetings or sharing digital images.

Disease classification

The classification of these neoplasms was performed in accordance with the 2016 WHO criteria based on the available clinical, pathologic, and genetic data, and verified by two authors (SAW and CYO). Per WHO guidelines, cases with a documented history of MDS or MPN were not classified as MDS/MPN except in the case of RS-T developing in the setting of prior MDS with RS. An MDS diagnosis required the presence of significant dysplasia (involving at least 10% of cells, at least 1 hematopoietic lineage), at least one cytopenia, and no cytosis, with the exception for MDS with isolated del(5q), in which thrombocytosis is considered within the scope of the disease. On the other hand, a diagnosis of MPN requires characteristic morphology of each specific entity, and does allow cytopenia(s) provided there is no significant dysplasia. Of note, the presence of RS, in the absence of dyserythropoiesis, was not used as a criterion to exclude cases that otherwise fulfilled the criteria of MPN. Diagnosis of CMML was per 2016 WHO Classification criteria, while other MDS/MPN required a WBC ≥ 13 × 109/L and/or a platelet count ≥450 × 109/L to define their MPN features; and dysplasia (with or without a concomitant cytopenia) to define their MDS features.

Cytogenetics

Conventional cytogenetic analysis was performed on G-banded metaphase cells prepared from unstimulated BM aspirate cultures using standard techniques. Twenty metaphases were analyzed and the results were reported using the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature.

Targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS)

Targeted NGS was performed to detect gene mutations commonly found in hematologic malignancies in each participating institution as described previously [26, 27]. The NGS panels were variable at each institution, but all panels interrogated a minimum of 42 commonly mutated genes by myeloid sequencing across >90% of the gene coding regions.

Treatment and follow-up

Treatment and outcome for all patients were determined from the medical record. The treatments were categorized as cytoreduction with hydroxyurea, JAK inhibitor, hypomethylating agents (HMA), or small molecule inhibitors, lenalidomide/thalidomide, observation/supportive care, and allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT).

Statistical analyses

Comparison among categorical variables and numerical variables was carried out by using the Fisher’s exact test and Mann–Whitney test, respectively. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or the last date of follow-up, whichever occurred earlier. Patients who underwent hematopoietic SCT were censored at the time of the procedure. Survival probability was determined using the Kaplan–Meier method, with differences compared by the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA) with significance set at a p value < 0.05 (two-sided).

Results

Patient cohort

This multi-institutional study identified 76 patients over a 3-year period with a diagnosis of MDS, MPN, or MDS/MPN (including 18 RS-T) that harbored both MPN-driver mutations and SF3B1 mutations, with no increase in blasts. There were 46 men and 30 women with a median age of 70 years (range, 35–95 years). NGS performed at the time of initial diagnosis in 41 (54%) and later in the course of disease in 35 (46%) patients.

Of note, although neither SF3B1 nor MPN-driver mutations are required for a diagnosis of RS-T, in this study, we only included the subset of cases with mutations involving SF3B1 as well as one of JAK2/MPL/CALR mutations, in order to appropriately compare to the non-MDS/MPN-RS-T (henceforth non-RS-T) cases. While all 18 RS-T had thrombocytosis and ≥15% RS at the time of initial diagnosis, at the time of NGS study (performed at initial diagnosis in 14 patients and later in the course of disease in 4 patients), 2 had a normal platelet count; all 17 with available BM aspirate smears showed ≥15% RS. Of the 16 patients with adequate bone marrow biopsy, abnormal karyotype was only seen in 2 patients (13%), one with del(13q) and the other one with +8.

Of the 58 non-RS-T patients, 42 (72%), 10 (17%), and 6 (11%) were considered to have MPN, MDS, and MDS/MPN other than RS-T, respectively. The MPN diagnoses at the time of NGS testing were polycythemia vera (PV, n = 5, including 3 post-PV MF), essential thrombocythemia (ET, n = 10, including 6 post-ET MF), primary myelofibrosis (PMF, n = 25, including 6 early/prefibrotic and 19 overt fibrotic phase), and MPN, unclassifiable (MPN-U, n = 2). Of note, NGS testing was performed after initial diagnosis on all PV and ET patients (n = 15) and in 12 PMF/MPN-U patients (median 81.5 months, range 35.7–377.4 months). In contrast, NGS was performed at the time of initial diagnosis in seven of ten (70%) MDS and five of six (83%) MDS/MPN patients. The MDS subtypes were MDS with RS and multilineage dysplasia (MDS-RS-MLD, n = 6), MDS with multilineage dysplasia (MDS-MLD, n = 1), MDS-MLD with unknown RS status (iron stain not performed, n = 1); and MDS with isolated del(5q) (n = 2). Non-RS-T MDS/MPN subtypes were MDS/MPN, unclassifiable (MDS/MPN-U, n = 6). Karyotype information at the time of NGS testing was available and adequate in 55 non- RS-T patients. An abnormal karyotype was seen in 14/40 (35%) MPN patients including a complex karyotype (≥3 abnormalities) in 3; del(20q) in 5, del(13q) in 3, and other random abnormalities. An abnormal karyotype was seen in 4/9 (44%) MDS patients including isolated del(5q) (n = 2), t(1;7) (n = 1) and one with dup(18). An abnormal karyotype was seen in 3/6 (50%) MDS/MPN, including complex karyotype (n = 1), del(7q) (n = 1), and one del(13q) (n = 1).

The CBC data, clinical information, and BM histopathological features obtained at the time of NGS are shown for MDS, MPN, or MDS/MPN in comparison to RS-T in Table 1.

Clinicopathological comparisons between different diagnostic groups and RS-T

There were no differences in age or gender distribution between any of the subgroups and RS-T. Due to the defining criteria of RS-T, the platelet count and cases with ≥15% RS were higher than any of the subgroups of the non-RS-T patients. MDS cases differed significantly from RS-T in frequent neutropenia, more frequent dysgranulopoiesis and dysmegakaryopoiesis; while splenomegaly and bone marrow fibrosis were relatively infrequent in both groups. In contrast, MPN differed from RS-T by significantly more frequent BM fibrosis (grade MF2 or MF3), splenomegaly, but less frequent dyserythropoiesis and dysmegakaryopoiesis (Table 1). Similar to MDS, the MDS/MPN cases had more frequent dysgranulopoiesis, but overall more heterogeneous. Comparing to RS-T, MDS, MPN, and MDS/MPN-U all showed a trend for more frequent abnormal karyotype; however, due to small sample size, the p values > 0.05.

Mutation data and mutation dominance

Of the 18 RS-T patients, JAK2, CALR, and MPL mutations were detected in 14 (78%), 3 (17%), and 1 (5%) patients, respectively, not significantly different from any of the other myeloid neoplasm subgroups (Table 1). However, CALR was notably absent in the MDS group. The median VAF of SF3B1 mutation was 35.0% (range 10.2–48.7%) in RS-T patients, not significantly different from any of the non-RS-T groups (Table 1). Although a VAF of SF3B1 < 10% was not observed in any of the RS-T or MDS/MPN patients, however, this was seen in 2/10 MDS and 4/42 MPN patients. Interestingly, none of the six patients with a SF3B1 VAF < 10% had RS. The median VAF of the MPN-driver mutations was 26.2% (range 5.5–45.2%) in RS-T, significantly lower than that of MPN patients (median 44.7%, range 5–98.6%, p = 0.0006). Although the median VAF of MPN-driver mutations in MDS was not statistically different from RS-T, cases with VAF of <10% was more common, including both cases of isolated del(5q), in MDS compared to RS-T (6/10 and 3/18 patients, respectively) (p = 0.0346). No difference in VAF of MPN-driver mutations was observed between RS-T and MDS/MPN patients.

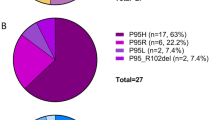

Using a 10% difference between these two mutation categories to define mutation dominance, the total cases were grouped into three clusters (Fig. 1a). In the “MPN-driver mutation dominance” cluster, the VAF of JAK2/CALR/MPL was ≥10% higher than SF3B1; in the “SF3B1 mutation dominance” cluster, the VAF of SF3B1 was ≥10% higher than JAK2/CALR/MPL; and in the “no dominance” cluster, the VAFs were similar between SF3B1 and JAK2/CALR/MPL (<10% difference). The majority of RS-T showed SF3B1 dominance or no dominance (Fig. 1a). In contrast, MDS cases had mostly showed “SF3B1 dominance,” whereas MPN cases more frequently showed MPN-driver mutation dominance (Fig. 1b and Table 1). Of note, 13 cases had MPN-driver mutation VAF ≥ 60%, which could be due to copy neutral loss of heterozygosity (CN-LOH) such as acquired uniparental disomy [28]. These 13 cases were exclusively of MPN cases, including 5 post-ET or PV myelofibrosis. If not considering these 13 cases with a VAF > 60%, the remaining 29 MPN showed no dominance in 13 (45%), MPN-driver mutation dominance in 9 (31%), and SF3B1 dominance in 7 (24%), and the difference became not statistically significant from RS-T (p = 0.108). There was no specific mutation dominance pattern for MDS/MPN; however, the assessment was based on a small number of cases.

a Clustering by mutation dominance between SF3B1 and MPN-driver mutations (JAK2, CALR, and MPL). MDS/MPN-RS-T cases showed either no dominance or SF3B1 dominance. b Overlapped mutational profiles with WHO diagnoses/classification. MPN-driver mutation dominance: (MPN-driver mutation VAF-SF3B1 mutation VAF) > 10%, SF3B1 dominance: (SF3B1 mutation VAF-MPN-driver mutation VAF) > 10%, no dominance: (MPN-driver mutation VAF-SF3B1 mutation VAF < 10%).

The mutation dominance patterns were separately analyzed on 41 cases in which NGS was performed at the time of the initial diagnosis (Fig. S1). Interestingly, while RS-T and MDS still showed a similar distribution of either SF3B1 dominance or no dominance, most newly diagnosed MPN patients fell into the “no dominance” category (n = 8, 53%), while four had MPN-driver mutation dominance and three SF3B1 dominance. This contrasted to patients with a history of MPN in whom NGS was performed after the initial diagnosis, who predominantly showed MPN-driver mutation dominance (n = 18, 67%), with only four and five patients with SF3B1 dominance and no dominance, respectively (p = 0.0321 compared to distribution of dominance in newly diagnosed cases).

Mutations in other genes were present in 11/18 (61%) of RS-T, including DNMT3A (4, 22%), TET2 (3, 17%), and TP53, SETBP1, ETV6, DDX41 one of each. In non-RS-T patients, additional mutations were detected in 34 (57%) patients, including TET2, ASXL1, DNMT3A, EZH2, IDH1/2, KRAS, RUNX1, SRSF2, SETBP1, and TP53 mutations; there were no significant differences in the distribution of other mutations between MDS, MPN, and other MDS/MPN (Table 1). However, mutations in ASXL1, EZH2, IDH1, RUNX1, and SRSF2 were absent in RS-T cases (Fig. 2). There were no differences in frequency of additional co-mutations between MPN patients who were tested at initial diagnosis or tested later in the course of their disease (7/15 vs 14/27, respectively, p > 0.05).

Overlapping “gray zone” cases

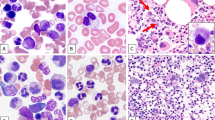

We assessed for disease features potentially overlapping with RS-T in the 27 cases in which NGS had been performed at or within 1 year of initial diagnosis. These cases were classified as MPN (n = 15, 13 PMF, fibrotic stage, 1 PMF, prefibrotic, and 1 MPN-U, no PV or ET); MDS (n = 7) and MDS/MPN-U (n = 5). One type of overlap was the presence of thrombocytosis together with anemia, but with <15% RS. These combination features were observed in four patients, including one with 7% RS, one with 2% RS, two with no RS. Two were diagnosed with PMF and two with MDS/MPN-U (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Based on relative VAFs, two patients had MPN-driver mutation dominance, including one with a mutation VAF > 60% suggesting possible CN-LOH; SF3B1 dominance and no dominance were observed in each of the remaining patients. The second type of overlap was the presence of >15% RS and anemia, but no thrombocytosis, including three MDS-RS-MLD, five fibrotic PMF, and one MPN-U. The classification was relatively straightforward in three MDS-RS-MLD; interestingly, none of these MDS-RS-MLD had thrombocytopenia (platelet counts 158–366 × 109/L). In these three patients, SF3B1 dominance and MPN-driver mutation dominance were seen in two and one patients, respectively. The six cases classified as MPN had typical MPN features (Table 2 and Fig. 3), albeit the presence of RS (range 15–70%). MPN-driver mutation dominance, no dominance and SF3B1 dominance were seen in three (including two with possible CN-LOH based on MPN-driver VAF), two, and one patient, respectively.

Upper panel: a case (Pt 9) resembling RS-T histopathologically with a proliferation of large pleomorphic megakaryocytes, dyserythropoiesis, and rare ring sideroblasts (7%). NGS showed SF3B1 36.2%, MPL 53.3%, and SRSF2. The case was classified as MDS/MPN-U. Lower panel: a patient (Pt2) with anemia requiring transfusion and splenomegaly, history of pulmonary embolism. Bone marrow biopsy shows a proliferation of large hyperchromatic megakaryocytes and MF2 fibrosis (not shown) but with marked erythroid predominance and 70% ring sideroblasts. NGS showed SF3B1 45.4%, JAK2 V617 23.3%, and DNMT3A. The case demonstrated hybrid clinical, morphological, and molecular features of MDS and MPN; however, due to the absence of cytosis, a classification of MDS/MPN could not be made by the WHO criteria, but instead, a diagnosis PMF with overt fibrosis and dysplastic-type progression was rendered. A diagnosis of MDS with fibrosis was considered, but the overall megakaryocyte morphology and topography and presence of splenomegaly were felt to be more in keeping with PMF.

Treatment and follow-up information

Treatment and follow-up information was available in 57/68 non-RS-T and 17/18 RS-T patients. JAK inhibitor was more frequently administered to MPN patients than to RS-T patients (p = 0.0032), while HMAs were more frequently used to treat MDS compared to RS-T (50% vs 8%, respectively, p = 0.0152).

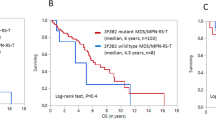

The median follow-up time from initial diagnosis was 45.8 months (range 1.0–403.1 months), and from NGS testing was 12.7 months (range 0–56.1 month) for the entire group. Specifically, the median follow-up was 24.3 months (1.1–106.7 month) for RS-T, 28.3 months (1.6–123.0) for MDS, 30.6 months (6.4–75.6) for MDS/MPN and 63.1 months (2.1–403) for MPN. The median OS from the time of initial diagnosis for RS-T patients was not reached in any of the groups, and not significantly different between RS-T from any of the subgroup of non-RS-T patients. There was also no difference when OS was calculated from the time of NGS testing.

Discussion

With this largest cohort of patients (n = 76) with myeloid neoplasms with <5% blasts and concomitant SF3B1 and JAK2/MPL/CALR mutations, we compared the cases classified as MDS/MPN-RS-T to those categorized as other myeloid neoplasms. Of these patients, 18 (24%), 42 (55%), 10 (13%), and 6 (8%) fulfilled the criteria for MDS/MPN-RS-T (RS-T), MPN, MDS, and MDS/MPN, respectively. The age, gender, severity of anemia, and requirement for transfusion were not statistically different when each of other diagnostic categories was compared to RS-T. RS-T patients had a higher platelet count and higher number of RS in BM, in part reflecting the diagnostic criteria defining RS-T. Additional differences observed in MDS included more frequent neutropenia and dysplasia involving the granulocytic and megakaryocyte lineages. In contrast, MPN cases showed more frequent MF2-3 bone marrow fibrosis and splenomegaly. The non-RS-T MDS/MPN cases were heterogeneous, and the comparison was further hampered by the small number of cases. An abnormal karyotype showed a trend less frequent in RS-T as compared to MDS, MPN, and MDS/MPN.

The molecular genetic data were further analyzed by the types of mutations, mutation dominance, and additional mutations. The distribution of JAK2, MPL, and CALR mutations was overall similar between RS-T and non-RS-T cases, being predominantly JAK2 p.V617F. CALR was notably absent in MDS cases, confirming its previously reported rarity in MDS as compared to MPN and MDS/MPN [29,30,31,32]. SF3B1 mutations are well-known to be associated with RS in MDS. In the study by Malcovati et al. [33], about 85% of low-grade MDS with SF3B1 mutations had ≥15% RS and conversely, SF3B1 mutation was detected in about 81% patients with a diagnosis of MDS-RS [34]. Interestingly, unlike SF3B1-mutated RS-T cases (which by definition had ≥15% RS), only 44% of SF3B1-mutated non-RS-T cases had ≥15% RS and 15% had 5–15% RS. Although the median VAF of SF3B1 in RS-T was not different from any other diagnostic groups, cases with SF3B1 mutation VAF of <10% was absent in the RS-T group but was seen in six non-RS-T patients, including both MDS and MPN cases. None of the latter cases had RS, underscoring the correlation of SF3B1 mutation VAF with the presence of RS [33]. On the other hand, the VAFs of MPN-driver mutations were significantly different among the diagnostic categories, being higher in MPN and lower in MDS compared to RS-T. In fact, a VAF of MPN-driver mutations <10% was observed in six out of ten (60%) MDS patients, including both cases of MDS with isolated del(5q). JAK2 mutations have been reported in a subset of MDS with isolated del(5q) cases [22, 35] and these cases often have a very high platelet count; in our series, the two MDS with isolated del(5q) patients had platelet counts of 354 and 369 × 109/L.

When assessing clonal dominance by VAFs of SF3B1 and MPN-driver mutations, acquired UPD (aUPD) must be taken into account. aUPD is relatively common in MPNs, being seen in 50–80% of PV, 50% of PMF, and 6–18% of ET by SNP array study [28]. While aUPD is nearly ubiquitous in patients with JAK2 VAF ≥ 60%, it may also occur in up to 30% of patients with a JAK2 VAF < 50%. Occurrence of aUPD or LOH of SF3B1 is largely unknown in myeloid neoplasms. Since we did not perform SNP array on our cases, we were unable to determine aUPD with certainty in our patients. However, 13 MPN cases had an MPN-driver mutation VAF ≥ 60% and thus likely displayed aUPD. On the other hand, there no consensus in the definition of clonal dominance. Mossner et al. [36] defined “clonal and subclonal” mutation in a cohort of MDS and CMML patients as the difference of VAFs of the two mutations ≥10% and their sum VAFs ≥55%. We examined our 14 cases with a VAF of <10% for either SF3B1 or MPN-driver mutations, and found only one case meeting the Mossner definition of “subclone,” and the rest 13 did not due to a sum VAF of <55%. However, we assigned clonal dominance in 11/14 patients due to a marked difference (15–50.1%) between the MPN-driver and SF3B1 VAF; whereas 3 patients had low VAFs in both mutations. With the above considerations and caveats, we used a 10% difference between SF3B1 and MPN-driver mutations to examine our cases. The RS-T cases displayed either an SF3B1 dominance or no dominance. This mutation dominance profile supports the suggestion [11, 12] that SF3B1mut is the founding mutation in most cases of RS-T. MDS cases most frequently displayed SF3B1 dominance. Similar patterns were also observed in cases where NGS was performed at the time of diagnosis, substantiating our findings (Supplementary Fig. 1). The mutation dominance profile was heterogeneous in the other MDS/MPN, with similar numbers of cases falling into each cluster. On the other hand, the MPN cases were more heterogeneous. In patients with a prior history of MPN in which NGS was performed after the initial diagnosis, there was a striking MPN-driver mutation dominance (two-thirds), suggesting that the MPN-driver mutation was the founding mutation and SF3B1 might be sublcone. Our data suggest a variable acquisition of mutations in some of these co-mutated cases, especially in MDS and in progressed MPNs (such as post-PV and post-ET MF), in which, either a SF3B1 or an MPN-driver mutations occurs first, followed by a subsequent, often subclonal mutation of the other gene. This variable clonal hierarchy may contribute at least in part to the different disease phenotypes leading to different disease subcategorizations at presentation. Of note, we also observed considerable numbers of cases, in both the MDS and MPN categories and in RS-T, showing no mutation dominance as well as minor subsets of cases having reversed dominance (i.e., SF3B1 dominance in MPN and MPN-driver dominance in MDS), indicating that clonal hierarchy alone may not drive disease phenotype in some cases.

We also examined for any association with additional somatic mutations with the disease category. Although the frequency of additional mutations in RS-T did not differ from any of the non-RS-T groups, certain mutations were notably absent in RS-T including ASXL1, EZH2, IDH1/2, RUNX1, and SRSF2. Additional somatic mutations reported in RS-T [11, 12] include TET2 (~25%), ASXL1 (15–20%), DNMT3A (~15%), and SETBP1 (~10%). Jeromin et al. (n = 92) further analyzed the additional mutations in RS-T by the status of SF3B1 and JAK2V617F; and they found that the most common additional mutations in SF3B1mut/JAK2V617Fmut were DNMT3A and TET2 while ASXL1 was mostly detected in the SF3B1wt or JAK2wt cases. It is known that ASXL1 is an adverse risk factor in patients with RS-T [11]. The restriction of our study to co-mutated RS-T cases may have accounted for the lack of ASXL1 mutations. It is generally agreed that spliceosome mutations are mutually exclusive; in over 2000 consecutive NGS tests at one of the participating institutions, co-mutations in two spliceosome-related genes (SF3B1 + SRSF2 or SF3B1 + U2AF1) were only seen in 0.4% myeloid neoplasms (data not shown). However, in our cohort of patients, five (8.6%) patients, including three MDS, one MDS/MPN-U and one MPN-U, had SRSF2 or U2AF1 mutations in addition to the SF3B1 mutation. Four of the five were in patients tested at the time of diagnosis, suggesting that the second spliceosome mutation did not appear to be secondarily acquired. The significance of the relatively high frequency of spliceosome co-mutations in our series of SF3B1 and MPN1-dirver mutated cohort is unknown. Nonetheless, it is possible that the overall types of additional somatic mutations might have contributed to the differences observed between MDS, MPN, MDS/MPN, and RS-T.

In the review of these cases, we became aware that the classification was difficult in some cases and the boundary between different entities was not so clear. There were cases with ≥15% RS and a proliferation of large MPN-like megakaryocytes reminiscent of RS-T but being classified either as MDS-RS or PMF due to a platelet count less than 450 × 109/L. The other overlap included cases with thrombocytosis and anemia resembling RS-T, but with either no or <15% RS, mandating classification as MDS/MPN-U. Of note, in the presence of SF3B1 mutation, the requirement of RS was lowered to 5% for a diagnosis of MDS-RS in the 2016 WHO Classification, but this change has not been applied to RS-T. Another type of “gray” cases was between PMF and MDS-fibrosis. Similar to the series by Boiocchi et al. examining MPN with SF3B1 mutations [20], many of the cases in our series were classified as overt fibrotic PMF. Clinically, many of these PMF patients had unusual severe anemia and some required frequent transfusions. Interestingly, of the 15 MPN patients who had both mutations detected at the time of diagnosis, none of them were PV or ET: 14 were classified as PMF (1 prefibrotic and 13 overt fibrotic) and 1 MPN-U. Furthermore, more than two-thirds of these “MPN” patients showed either no clonal dominance or SF3B1 dominance, suggesting that the SF3B1 mutation was not secondarily acquired in these newly presenting patients. On the other hand, some MDS cases, despite a lack of thrombocytosis, carried other MPN features such as a proliferation of pleomorphic large megakaryocytes and splenomegaly and some with MF2-3 fibrosis. The presence of an MPN-driver mutation at a high VAF raised the question if these cases would be more appropriately classified as MDS/MPN or MPN with dysplastic-type progression.

The treatments for these patients included JAK inhibitors, cytoreduction, lenalidomide/thalidomide, HMAs, small molecule inhibitors, and/or SCT. A significant high proportion of MPN patients received JAK inhibitor, and more MDS patients received HMA. SF3B1 mutations in MDS are known to be associated with prolonged survival and a lower risk for AML progression. In addition, it has been shown that SF3B1, not the presence of RS, correlates with the favorable outcome in MDS patients [34, 37]. In RS-T, both SF3B1 and JAK2 mutations have been identified as independent factors for a favorable prognosis [16]. The median OS of our patients was not reached in any of the groups. However, the median follow-up was relatively short, except in MPN patients who had a median follow-up of 63.1 months. It is uncertain if, like in RS-T, the combination of SF3B1 and JAK2 (or other MPN-driver mutations) mutations may confer a survival benefit in MDS, MPN, or other MDS/MPN; this would require comparisons with noncomutated cases and a longer follow-up.

In summary, co-mutations of MPN-driver genes and SF3B1 mutation do occur in myeloid neoplasms other than RS-T; while most such cases are classified as MPN, some are MDS and some are categorized as MDS/MPN-U. These cases, as categorized by the current WHO criteria, show some overlap, but also distinct clinical and histopathological features that separate them from RS-T. The mutation dominance of SF3B1 vs the MPN-driver sheds light into the clonal hierarchy and may in part explain the different disease manifestations. Additional somatic mutations as well as cytogenetic abnormalities may also influence the disease phenotype. One limitation of this study was a lack of mutation profile at the time of initial diagnosis in half of the cases; sequential genetic evaluation may help determine the order of mutations and their association with changes in the disease phenotype over time. Nevertheless, our data suggest that the molecular genetic differences might contribute to observed heterogeneity in disease phenotypes leading to the different WHO categorizations. Within this group of co-mutated myeloid neoplasms, some “gray zone” cases showed hybrid MDS and MPN features, but could not be classified either as RS-T or another MDS/MPN due to a lack of cytosis, sufficient number of RS, or a lack of dysplasia; in some cases, the latter was due to an inability to confirm possible dysplasia in the aspirate smear due to marked fibrosis. Further study is needed to determine if the mutation profile (including the mutation hierarchy) may contribute to categorization of MDS, MPN, or MDS/MPN in addition to the well-established features of blood counts and morphology, may contribute to categorization of myeloid neoplasms as MDS, MPN, or MDS/MPN.

References

Grinfeld J, Nangalia J, Green AR. Molecular determinants of pathogenesis and clinical phenotype in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Haematologica. 2017;102:7–17.

Rumi E, Cazzola M. Diagnosis, risk stratification, and response evaluation in classical myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2017;129:680–92.

Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114:937–51.

Yoshida K, Sanada M, Shiraishi Y, Nowak D, Nagata Y, Yamamoto R, et al. Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature. 2011;478:64–9.

Grinfeld J, Nangalia J, Baxter EJ, Wedge DC, Angelopoulos N, Cantrill R, et al. Classification and personalized prognosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1416–30.

Haferlach T, Nagata Y, Grossmann V, Okuno Y, Bacher U, Nagae G, et al. Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2014;28:241–7.

Meggendorfer M, Jeromin S, Haferlach C, Kern W, Haferlach T. The mutational landscape of 18 investigated genes clearly separates four subtypes of myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Haematologica. 2018;103:e192–5.

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al. In: Bosman FT, Jaffe ES, Lakhani SR, Ohgaki H, editors. WHO Classification of tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Revised 4th ed. Lyon: IARC; 2017.

Patnaik MM, Lasho TL, Finke CM, Hanson CA, Hodnefield JM, Knudson RA, et al. Spliceosome mutations involving SRSF2, SF3B1, and U2AF35 in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: prevalence, clinical correlates, and prognostic relevance. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:201–6.

Visconte V, Rogers HJ, Singh J, Barnard J, Bupathi M, Traina F, et al. SF3B1 haploinsufficiency leads to formation of ring sideroblasts in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;120:3173–86.

Patnaik MM, Lasho TL, Finke CM, Hanson CA, King RL, Ketterling RP, et al. Predictors of survival in refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts and thrombocytosis (RARS-T) and the role of next-generation sequencing. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:492–8.

Jeromin S, Haferlach T, Weissmann S, Meggendorfer M, Eder C, Nadarajah N, et al. Refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts and marked thrombocytosis cases harbor mutations in SF3B1 or other spliceosome genes accompanied by JAK2V617F and ASXL1 mutations. Haematologica. 2015;100:e125–7.

Raya JM, Arenillas L, Domingo A, Bellosillo B, Gutierrez G, Luno E, et al. Refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts associated with thrombocytosis: comparative analysis of marked with non-marked thrombocytosis, and relationship with JAK2 V617F mutational status. Int J Hematol. 2008;88:387–95.

Broseus J, Lippert E, Harutyunyan AS, Jeromin S, Zipperer E, Florensa L, et al. Low rate of calreticulin mutations in refractory anaemia with ring sideroblasts and marked thrombocytosis. Leukemia. 2014;28:1374–6.

Nangalia J, Massie CE, Baxter EJ, Nice FL, Gundem G, Wedge DC, et al. Somatic CALR mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms with nonmutated JAK2. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2391–405.

Broseus J, Alpermann T, Wulfert M, Florensa Brichs L, Jeromin S, Lippert E, et al. Age, JAK2(V617F) and SF3B1 mutations are the main predicting factors for survival in refractory anaemia with ring sideroblasts and marked thrombocytosis. Leukemia. 2013;27:1826–31.

Broseus J, Florensa L, Zipperer E, Schnittger S, Malcovati L, Richebourg S, et al. Clinical features and course of refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts associated with marked thrombocytosis. Haematologica. 2012;97:1036–41.

Patnaik MM, Tefferi A. Refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts (RARS) and RARS with thrombocytosis: “2019 Update on Diagnosis, Risk-stratification, and Management”. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:475–88.

Wang SA, Hasserjian RP, Loew JM, Sechman EV, Jones D, Hao S, et al. Refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts associated with marked thrombocytosis harbors JAK2 mutation and shows overlapping myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic features. Leukemia. 2006;20:1641–4.

Boiocchi L, Hasserjian RP, Pozdnyakova O, Wong WJ, Lennerz JK, Le LP, et al. Clinicopathological and molecular features of SF3B1-mutated myeloproliferative neoplasms. Hum Pathol. 2019;86:1–11.

Lasho TL, Finke CM, Hanson CA, Jimma T, Knudson RA, Ketterling RP, et al. SF3B1 mutations in primary myelofibrosis: clinical, histopathology and genetic correlates among 155 patients. Leukemia. 2012;26:1135–7.

Ingram W, Lea NC, Cervera J, Germing U, Fenaux P, Cassinat B, et al. The JAK2 V617F mutation identifies a subgroup of MDS patients with isolated deletion 5q and a proliferative bone marrow. Leukemia. 2006;20:1319–21.

Wang SA, Hasserjian RP, Fox PS, Rogers HJ, Geyer JT, Chabot-Richards D, et al. Atypical chronic myeloid leukemia is clinically distinct from unclassifiable myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2014;123:2645–51.

Mufti GJ, Bennett JM, Goasguen J, Bain BJ, Baumann I, Brunning R, et al. Diagnosis and classification of myelodysplastic syndrome: International Working Group on Morphology of myelodysplastic syndrome (IWGM-MDS) consensus proposals for the definition and enumeration of myeloblasts and ring sideroblasts. Haematologica. 2008;93:1712–7.

Thiele J, Kvasnicka HM, Facchetti F, Franco V, van der Walt J, Orazi A. European consensus on grading bone marrow fibrosis and assessment of cellularity. Haematologica. 2005;90:1128–32.

Weinberg OK, Hasserjian RP, Baraban E, Ok CY, Geyer JT, Philip J, et al. Clinical, immunophenotypic, and genomic findings of acute undifferentiated leukemia and comparison to acute myeloid leukemia with minimal differentiation: a study from the bone marrow pathology group. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:1373–85.

Wang SA, Tam W, Tsai AG, Arber DA, Hasserjian RP, Geyer JT, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing identifies a subset of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome with features similar to chronic eosinophilic leukemia, not otherwise specified. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:854–64.

Wang L, Swierczek SI, Lanikova L, Kim SJ, Hickman K, Walker K, et al. The relationship of JAK2(V617F) and acquired UPD at chromosome 9p in polycythemia vera. Leukemia. 2014;28:938–41.

Klampfl T, Gisslinger H, Harutyunyan AS, Nivarthi H, Rumi E, Milosevic JD, et al. Somatic mutations of calreticulin in myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2379–90.

Malcovati L, Rumi E, Cazzola M. Somatic mutations of calreticulin in myeloproliferative neoplasms and myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Haematologica. 2014;99:1650–2.

Liu YC, Illar GM, Bailey NG. Clinicopathologic characterisation of myeloid neoplasms with concurrent spliceosome mutations and myeloproliferative-neoplasm-associated mutations. J Clin Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2020-206495 2020.

Della Porta MG, Travaglino E, Boveri E, Ponzoni M, Malcovati L, Papaemmanuil E, et al. Minimal morphological criteria for defining bone marrow dysplasia: a basis for clinical implementation of WHO classification of myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2015;29:66–75.

Malcovati L, Papaemmanuil E, Bowen DT, Boultwood J, Della Porta MG, Pascutto C, et al. Clinical significance of SF3B1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2011;118:6239–46.

Malcovati L, Karimi M, Papaemmanuil E, Ambaglio I, Jadersten M, Jansson M, et al. SF3B1 mutation identifies a distinct subset of myelodysplastic syndrome with ring sideroblasts. Blood. 2015;126:233–41.

Sangiorgio VF, Geyer JT, Margolskee E, Al-Kawaaz M, Mathew S, Tam W, et al. Myeloid neoplasms with isolated del(5q) and JAK2 V617F mutation: a grey zone combination of myelodysplastic and myeloproliferative features? Haematologica. 2020;105:e276–9.

Mossner M, Jann JC, Wittig J, Nolte F, Fey S, Nowak V, et al. Mutational hierarchies in myelodysplastic syndromes dynamically adapt and evolve upon therapy response and failure. Blood. 2016;128:1246–59.

Xiong B, Xue M, Yu Y, Wu S, Zuo X. SF3B1 mutation but not ring sideroblasts identifies a specific group of myelodysplastic syndrome-refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20:329–39.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ok, C.Y., Trowell, K.T., Parker, K.G. et al. Chronic myeloid neoplasms harboring concomitant mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasm driver genes (JAK2/MPL/CALR) and SF3B1. Mod Pathol 34, 20–31 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-0624-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-0624-y

This article is cited by

-

Myelodysplastic syndrome/myeloproliferative neoplasm overlap syndromes: a practical guide to diagnosis and management

Leukemia (2025)

-

Predicting survival in patients with myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms with SF3B1 mutation and thrombocytosis

Leukemia (2024)

-

Association of JAK2V617F allele burden and clinical correlates in polycythemia vera: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Annals of Hematology (2024)