Abstract

The social deficits following chronic stress conditions are linked to synaptic dysfunction in the brain. Complement system plays a critical role in synapse regulation. Although complement has been implicated in chronic stress-induced behavior deficits the cellular substrates and mechanisms underlying complement-mediated behavior changes under chronic stress conditions are not known. In the present study, we investigated the role of complement component 3a receptor (C3ar1) in microglia and monocytes/macrophages (Mo/MΦ) in chronic unpredictable stress (CUS)-induced synapse loss and behavior deficits in mice. We found that deletion of microglial C3ar1 attenuated stress-induced social behavior deficits and changes in neuroinflammatory as well as synaptic markers in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). RNA sequencing data revealed that microglial C3ar1 deletion attenuates CUS-mediated changes in the expression of immediate-early genes such as Fos and Nuclear Receptor Subfamily 4 Group A Member 1 (Nr4a1) in the PFC. In contrast, lack of C3ar1 in Mo/MΦ induced social behavior deficits. Together, these findings indicate opposite functions of C3ar1 signaling in microglia and Mo/MΦ under chronic stress conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic stress is associated with an increased risk for neuropsychiatric conditions. Exposure to chronic stress has been shown to result in abnormalities in social behavior [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. The social behavior deficits following chronic stress conditions are associated with immune dysfunction in the brain [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Increases in the levels of proinflammatory cytokines have been reported in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), a key brain region implicated in social and cognitive behavior as a result of chronic stress [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Abnormal microglial engulfment of synaptic terminals results in synaptic loss, disrupting synaptic activity and impairing the function of neuronal circuits [30,31,32,33]. Significant reductions in synaptic proteins and altered neuronal connectivity have been reported in rodents following chronic stress exposure [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Moreover, microglia isolated from the frontal cortex of mice exposed to CUS show elevated CSF1 receptor expression and increased phagocytosis of neuronal elements [42]. These findings suggest that synaptic loss contributes to behavioral abnormalities seen in chronic stress conditions. However, the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood.

Complement system is part of the innate immune system and plays a critical role in synapse regulation [43,44,45,46]. Although earlier studies have extensively focused on the immune regulatory functions of complement system recent studies indicate their roles in phagocytosis of synaptic molecules in the CNS. Specifically, synaptic stripping of neuronal connections has been demonstrated to occur via a complement-dependent mechanism [29, 32, 47,48,49,50,51]. Microglia express complement component receptors and previous studies have shown the role of microglial complement signaling in synaptic pruning during development [52, 53], and in neurodegenerative conditions [54,55,56,57]. Complement activation occurs via three pathways- classical, lectin and alternative, all of which lead to cleavage of the central complement component 3, C3. C3a, the activated C3 fragment, signals via its receptor C3ar1 in stimulating a number of signaling pathways to induce both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects [58,59,60]. Mice with C3 deletion showed significant reductions in chronic stress-induced synaptic pruning and alleviation of disrupted functional connectivity in medial PFC [61]. Using C3ar1 global knockout mice recent studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that C3ar1 promotes chronic stress-induced behavioral abnormalities [62]. Interestingly, C3ar1 is expressed on both types of myeloid cells- microglia and peripheral monocytes/macrophages (Mo/MΦ) [63,64,65], and both these cell types are implicated in chronic stress-induced neuroinflammation [21, 23, 66,67,68,69,70,71]. However, myeloid cell-specific function of C3ar1 in chronic stress-induced behavior deficits is unknown. Using conditional knockout models, the present study examined the role of C3ar1 in these cell types in stress-associated behavioral abnormalities.

We demonstrated that C3ar1 expression in Mo/MΦ is protective, whereas its expression in microglia promotes stress susceptibility. Deletion of microglial C3ar1 attenuated stress-induced social behavior deficits and reduced neuroinflammatory and synaptic marker changes in the PFC, whereas the absence of C3ar1 in Mo/MΦ induces social behavior deficits. Together, these findings indicate opposite functions of C3ar1 signaling in microglia and Mo/MΦ under chronic stress conditions.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6J male mice at 6–8 weeks old were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. C3ar1 floxed mice (C3ar1fl) were generated by the University of Rochester Mouse Genome Editing Resource (Fig. S1). To restrict C3ar1 ablation to microglia, Cx3cr1CreER mice (B6.129P2(Cg)-Cx3cr1tm2.1(cre/ERT2)Litt/WganJ ; #021160; The Jackson Laboratory) were crossed with C3ar1fl mice. Treating the progeny (6–8 weeks old) intraperitoneally with tamoxifen (75 mg/kg body weight; T5648, Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in corn oil (C8267, Sigma) every 24 h for 5 consecutive days generated C3ar1MGKO mice (C3ar1 deleted in microglia). For all experiments, littermates of Cx3cr1CreER:C3ar1fl receiving corn oil were used as controls (hereafter C3ar1MGWT). Similarly, to restrict C3ar1 ablation to Mo/MΦ, CCR2CreER mice (C57BL/6-Ccr2em1(icre/ERT2)Peng/J; # 035229; The Jackson Laboratory) were crossed with C3ar1fl mice. Treating the progeny with tamoxifen every 24 h for 5 consecutive days generated mice C3ar1MφKO (C3ar1 deleted in Mo/MΦ). Littermates of CCR2CreER:C3ar1fl receiving corn oil were used as controls (hereafter C3ar1MφWT). Both C3ar1MGKO and C3ar1MφKO were viable, fertile and normal in size. Animals were housed (5 mice per standard polypropylene cages in a 12-h light-dark cycle) in the animal facility of The University of Texas Health Science Center (UTHealth) at Houston in compliance with the US National Institute of Health guidelines, which was approved by UTHealth Houston animal welfare guidelines. Assignment of experimental mice were based on their genotype and were randomly selected in a blinded manner for the experiments. The details of the PCR primers used for genotyping are provided in Table S1. C3ar1 deletion was confirmed by qRT-PCR and flow cytometry analysis.

Chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) protocol

At the preclinical level, the chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) model is one of the most used paradigms in rodents to study the effects of chronic stress on brain plasticity [41, 72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79]. The paradigm includes exposures to variable unpredictable, and uncontrollable stressors. CUS was performed according to our previously published procedure [62, 80, 81]. Mice were housed individually under standard housing conditions three weeks before the CUS began. The stress regimen was mixed such that the same stressor never occurred consecutively within a day. The unstressed (naïve) mice were exposed to the same temporal and spatial sequence of habituation and behavior tests days, similar to the stressed mice. Stressors were presented in a random order in an unpredictable fashion for three weeks where mouse was singly housed (Table S2).

Behavioral tests

Mouse behavior were tested in a room with ambient light, temperature, sound, and pressure. Mice were habituated in the behavior room for an hour prior to the behavior testing. Behavioral tests were performed and scored in a blinded manner. Mice were tested during the light cycle. Mice were between 12 and 14 weeks old during the behavioral tests.

Three-chamber test

A clear Plexiglas® apparatus with the dimension of 19 cm × 45 cm × 22 cm was used for the three-chamber test. For free access, each chamber had openings for the other two chambers. Identical ventilated wire mesh containers were placed in the mouse and empty chambers. For the habituation test, mouse was placed in the center chamber and allowed to move freely for 5 min. After that, a stranger mouse (similar age, sex, and background) was introduced in wire mesh container of the mouse chamber. Ventilation of the wire mesh containers allowed air exchange but restricted direct physical contact. The test mouse was video recorded for 5 min for the time spent in the stranger mouse, empty, and center chambers. Absolute time was used to report sociability test results [82,83,84].

Reciprocal social interaction test

Reciprocal social interaction test occurred after the Three-chamber test on the same day. We used the same stranger mouse in both 3-chamber test and reciprocal interaction test. The stranger mouse was of the same age, sex and background of the test mouse. The stranger mouse was temporarily marked using non-toxic markers or dyes (e.g., Sharpie or fur dye) to distinguish from the test mouse. The test mouse was allowed to interact physically with the stranger mouse for 5 min. The close physical contact was considered and scored for the nose-to-nose sniffing, grooming and anogenital sniffing. Only the interactions initiated by test mouse were considered in this test.

Y-maze test

We used Y-maze (Maze Engineers) to perform a continuous spontaneous alternation test measuring spatial working memory deficits. There are three arms in Y-maze at 120° and each arm of the Y-maze is 32 cm long, 6 cm wide, and 20 cm high with visual distal cues around. The test mouse was monitored and recorded by web camera (C920, Logitech, Newark, CA) for 7 min, and the data were analyzed by Any-Maze software (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL). Entry of the mouse in the arm was considered if the whole body entered the arm, except for the tail. The same rule applied to the exit. Consecutive entry to the three different arms was counted as an alternating triad. The maximum number of triads is the total number of arm entries minus 2; the score of alternation is calculated as the number of alternating triads/(the total number of arm entries −2).

Flow cytometry

The PFC and hippocampus tissues were collected after perfusion with PBS according to a mouse brain atlas [62]. Single-cell suspension was prepared by cutting brain tissue into smaller pieces using a sharp blade. The tissue pieces were gently triturated in cold PBS using a fire-polished glass pipette or a plastic Pasteur pipette to dissociate it into smaller fragments. Repeated, gentle pipetting was performed until the tissue was sufficiently broken down into a uniform suspension followed by sieving through a 100-μM cell strainer (BD Biosciences) and centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 10 min. Care was taken to avoid over-trituration, as excessive pipetting could damage cells and reduce viability. In a separate set of mice, blood was collected in heparin tube (#366667; BD, NJ, USA) after decapitation under anesthesia. RBC lysis buffer was added to lyse RBC from the whole blood according to manufacturer’s protocol (#420301; BioLegend, CA, USA). Cells were washed with PBS. Cells were incubated with surface marker antibodies, CD11b (#101228), CD45 (#103138), Ly6C (#128022) (all purchased from BioLegend) and C3aR (# sc-133172, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Cells were washed with cold PBS and fixed with Fixation/Permeabilization buffer (Affymetrix eBioscience). Stained samples were run in flow-cytometer instrument (BD FACSAriaII). Flow data were analyzed using BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Positive cell populations for each marker were identified by using the Fluorescence Minus One (FMO) controls. A percentage of the gated events were used to report specific markers on the cells. Median fluorescence intensity derived from a fluorescence graph was used to study the level of cell surface expression.

Single cell type isolation from the PFC

The PFC tissue samples were collected after perfusion with PBS. The tissues were rinsed in D-PBS containing 0.5% BSA, sliced into 4 sagittal sections, and placed into gentle MACS C-tubes (#130-093-237, Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA), and processed for generating single-cell suspensions, using the Adult Brain Dissociation Kit (#130-107-677, Miltenyi Biotec) and Gentle MACS Octo Dissociator system (#130-095-937, Miltenyi Biotec). Following debris removal (#130-109-398, Miltenyi Biotec), cells were resuspended in 1 mL of 0.5% BSA in 1XPBS. The MACS (Miltenyi Biotec) assay was used to positively select microglia, astrocytes and neurons. Approximately 1 × 107 viable cells were incubated with CD11b (Microglia) MicroBeads (#130-093-634, Miltenyi Biotec). The cell suspension was then applied to an MS separation column (Miltenyi Biotec) fitted into a Quadro MACS cell separator (Miltenyi Biotec). Unlabeled cells were allowed to pass through the column while labeled cells remained captured in the magnetic field. After washing the column with MACS buffer, the column was then removed from the magnetic separator and flushed with 5 mL MACS buffer to collect the purified microglial population. The flow through was collected and used for isolating the astrocytes using Anti-ACSA-2 MicroBead Kit (#130-097-678, Miltenyi Biotec) and neuronal population using neuron isolation kit (#130-115-389, Miltenyi Biotec), following the kit protocol. An aliquot of cells was retained as cell input for flow cytometric and Real-time PCR analyses.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR)

For the mRNA analysis by qRT-PCR, we purified RNA from the PFC tissues using SV RNA Isolation kit from Promega. qRT-PCR was performed by using iTaqTM Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) with QuantStudio™ 3 Real-Time PCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Integrated DNA Technologies synthesized specific primers for the genes. Beta2-microglobulin (B2m) was used a housekeeping gene to normalize the gene of interest. The detail of primers used is provided in Table S1.

Western blotting

PFC tissues were lysed using a radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (#78443, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein concentration was quantified using Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (#23227) from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Samples were electrophoresed in a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions and then transferred to PVDF membranes (#IPVH00010, Millipore). After the transfer, PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in 1 × TTBS buffer (1.21 g Tris [BP152-5, Fisher Scientific], 8.77 g NaCl [#BP358-212, Fisher Scientific], 500 μL Tween-20 [#BP337-500, Fisher Scientific], pH 7.6 for 1 L). Then, the membranes were incubated with anti-PSD95 antibody (#2507, Cell signaling technology) and anti-synaptophysin antibody (#5461, Cell signaling technology) at 4 °C overnight. Beta-actin (ACTB; A5441; Sigma-Aldrich) was used to normalize the loading protein. After washing, the membranes were incubated the secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) for 1 h followed by washing and detection using Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (#34078, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Golgi staining

Golgi staining was carried out according to manufacturers’ guidelines (FD Rapid Golgi Stain Kit, FD Neurotechnologies, Baltimore, MD, USA). Briefly, the mouse brains were separated, rinsed with PBS and were placed in impregnation solution and stored in the dark for two weeks at room temperature. Then, the brains were transferred to a second impregnation solution and incubated for another week at room temperature. 100 μm PFC sections were prepared using a cryotome and mounted on gelatin-coated slides. Sections were rinsed in distilled water followed by dehydration in absolute alcohol. Sections were cleared with xylene, and mounted with mounting medium and coverslips.

Dendritic spine imaging and quantification

Golgi-stained PFC sections were imaged by confocal microscopy using a 63X oil lens to generate Z-stacks with a step-size of 0.2 μm to obtain detailed 3D structures of spines. Dendrites which were free from overlapping structures, were selected for analysis. Images were processed using Fiji/ImageJ, where dendritic segments were traced, and spines were quantified. Spine density was calculated as the number of spines per 10 micrometer of dendrite length [85, 86].

Bulk mRNA sequencing

To examine mRNA, the quality of total RNA from the whole PFC tissues was assessed using the Agilent RNA 6000 Pico kit (#5067–1513) with the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). RNA samples with an integrity number greater than 7 were selected for library preparation (Table S3). Library construction involved the use of the NEBNext Ploy(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (E7490L, New England Biolabs), NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for ILLumina (E7760L, New England Biolabs), and NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (E6609S, New England Biolabs), following the manufacturer’s protocols. Final library quality was assessed using the Agilent High Sensitive DNA Kit (#5067–4626) with the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA), and library concentrations were determined using qPCR with the Collibri Library Quantification kit (#A38524500, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The libraries were uniformly pooled and subjected to paired-end 75-cycle sequencing using an Illumina NextSeq 550 System (Illumina, Inc., USA) with the High Output Kit v2.5 (#20024907, Illumina, Inc., USA). In alignment with our study objectives, we employed a standard sequencing depth of 20–30 million reads per sample, as this is widely recommended for reliable differential expression analysis, particularly in mammalian transcriptomes. The FASTQ reads were processed for quality control using Fastqc (v 0.11.9) [87], underwent a trimming process to eliminate low-quality bases and adapter sequences using Fastp (v 0.23.2) [88] (Table S3). Subsequently, the high-quality FASTA reads were aligned to the mouse (GRCm39) genome using STAR (v 2.7.10b) [89]. The high-quality mapped reads were binarized and sorted using STAR to be ready for generating gene count matrices using feature counts [90]. The downstream analysis was conducted using R (version 4.2.2) along with the DESeq2 package [91]. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were detected by setting the log2 (fold change) > 1 and adjusted p-value < 0.05 to obtain the upregulated and downregulated genes, then subsequently visualized in heatmap.

Statistical analysis

Results were presented as mean ± SEM. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size, but our sample sizes were similar to those reported in previous study [80]. Statistical analysis was done using two-tailed Student’s t-tests to compare two groups, and Two-way (stress x genotype) or Three-way (stress x genotype x chamber) Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for the multiple-group comparisons. Bonferroni’s posthoc test was performed for the comparison using GraphPad Prism (Version 10). The bulk RNA-seq analysis was performed using R (version 4.2.2) and the DEGs were called by DESeq2 package for subsequent analysis.

Results

Deletion of C3ar1 in microglia attenuates chronic stress-induced social behavior deficits

C3ar1 is robustly expressed in the brain in early postnatal development and during adulthood (Fig. 1A). Microglia/macrophages (Cd11b+ve), astrocytes (GFAP+ve) and neurons (NeuN+ve) were isolated from the PFC tissues of adult (10-week-old) male mice exposed to NS or CUS using cell type-specific antibodies. RT-PCR analysis of isolated cells showed a significant increase in C3ar1 mRNA in the microglia/macrophages of CUS-exposed mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 1B). No change in C3ar1 expression was found in astrocytes or neurons following CUS (Fig. 1B). Using flow cytometry analysis (Fig. S2A), we further show that C3ar1 was widely expressed in microglia in the PFC of adult male mice following CUS (p < 0.05; Fig. S2B). No significant change in the expression of C3ar1 was found in the hippocampus following CUS (Fig. S2C). To delete C3ar1 in microglia, we crossed Cx3cr1CreER mice with C3ar1fl mice. The daily tamoxifen administration for five days followed by a 28-day waiting period resulted in C3ar1 depletion in microglia in the adult C3ar1MGKO mice (Fig. S3A, B). PCR analysis of isolated CD11b+ cells from the PFC of tamoxifen injected C3ar1MGKO mice showed significant reduction in C3ar1 expression as compared to C3ar1 expression in CD11b- cells from C3ar1MGKO mice and CD11b+ cells from C3ar1MGWT control group (p < 0.05; Fig. S3C). To examine whether C3ar1 deletion in microglia results in abnormalities in social behavior, we examined social behavior in naïve C3ar1MGKO and control mice. Three-chamber sociability test showed no abnormal social behavior in naïve C3ar1MGKO mice (Fig. 1C). In addition, social interaction in naïve C3ar1MGKO mice was found comparable to control mice (Fig. 1D). Exposure to chronic stress induced significant deficits in social behavior in control group as evidenced by no preference by stress-exposed control mice for either chamber in the three-chamber test (Fig. 1C). However, stress-induced C3ar1MGKO mice spent more time in the chamber housing stranger mouse than the empty cage chamber (p < 0.05; Fig. 1C). In the reciprocal social interaction test, stress-exposed control mice showed decreased interaction with a stranger mouse when compared with no stress control group (p < 0.05; Fig. 1D). Interestingly, chronic stress failed to induce any significant change in the interaction time in C3ar1MGKO mice (Fig. 1D). Analysis with Y-maze test showed no change in spatial working memory in naïve C3ar1MGKO mice (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, CUS did not result in any significant working memory deficits in controls and C3ar1MGKO mice (Fig. 1E).

A Expression profile of C3ar1 in the PFC and hippocampus of male C57BL/6 mice. B C3ar1 mRNA levels in the microglia/macrophages (Cd11b+ve), astrocytes (GFAP+ve) and neurons (NeuN+ve) of PFC samples from adult male mice exposed to no stress (NS) or chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) (Student’s t test; p < 0.05 vs NS; n = 4 per group). C Time in chamber in the three-chamber test. Three-way ANOVA (stress X genotype X chamber), chamber [F (2, 105) = 138.7, p < 0.0001]; chamber x stress [F (2, 105) = 4.050, p = 0.0202]; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (mouse chamber vs empty chamber); n = 9–10 per group. D Reciprocal social interaction test; Two-way ANOVA, stress [F (1, 31) = 5.266, p = 0.0287]; interaction (stress x genotype) [F (1, 31) = 5.051, p = 0.0319]; *p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-NS); n = 8–10 per group. E Y-maze test. Two-way ANOVA, n = 8–10 per group.

Deletion of C3ar1 in microglia attenuates chronic stress-induced immune dysfunction in the PFC

Since infiltration of peripheral monocytes/macrophages into the PFC has been previously reported in mice following chronic stress exposure [67, 92], we analyzed the number of infiltrating monocytes/macrophages in the PFC of C3ar1MGKO and control mice (Fig. 2A). We found no significant difference in the number of infiltrating peripheral macrophages (CD11b+CD45high) in the PFC of naïve C3ar1MGKO mice compared to control group (Fig. 2B). We found a significant increase in the number of infiltrating peripheral macrophages in the PFC of control mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 2B), but not in C3ar1MGKO mice following CUS. No significant change in the number of microglia (CD11b+CD45low) was found in the PFC of naïve male C3ar1MGKO mice compared to control group (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, CUS did not result in any significant change in the number of microglia in the PFC of control and C3ar1MGKO mice (Fig. 2C).

A–C Flow cytometry analysis of infiltrating monocytes and resident microglia in the PFC of mice (C3ar1MGWT and C3ar1MGKO) exposed to NS or CUS. A Flow cytometry gating strategy showing CD11b+ve cells were analyzed using CD45 to differentiate infiltrating macrophages (CD45high) from resident microglia (CD45low). B % of CD11b+ve cells expressing CD45high in the PFC of C3ar1MGWT and C3ar1MGKO mice exposed to NS or CUS. Two-way ANOVA, stress [F (1, 22) = 10.98, p = 0.0032]; *p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-NS); n = 6–7 per group. C % of CD11b+ve cells expressing CD45low in the PFC of C3ar1MGWT and C3ar1MGKO mice exposed to NS or CUS. Two-way ANOVA, n = 6–7 per group. D mRNA levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the PFC of C3ar1MGWT and C3ar1MGKO mice exposed to NS or CUS. iNOS; Two-way ANOVA, stress [F (1, 18) = 12.47, p = 0.0024]; genotype [F (1, 18) = 24.30, p = 0.0001] and interaction (stress x genotype) [F (1, 18) = 14.27, P = 0.0014]; ***p < 0.001 (vs C3ar1MGWT-NS) and ###p < 0.001 (vs C3ar1MGWT-CUS), n = 5–6 per group. TNFα; Two-way ANOVA, genotype [F (1, 19) = 8.283, p = 0.0096] and interaction (stress x genotype) [F (1, 19) = 7.876, p = 0.0113]; *p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-NS) and ##p < 0.01 (vs C3ar1MGWT-CUS), n = 5–6 per group. IL4Rα; Two-way ANOVA, stress [F (1, 17) = 23.47, p = 0.0002]; genotype [F (1, 17) = 14.05, p = 0.0016] and interaction (stress x genotype) [F (1, 17) = 13.01, p = 0.0022]; ***p < 0.001 (vs C3ar1MGWT-NS) and ###p < 0.001 (vs C3ar1MGWT-CUS), n = 5–6 per group. IL1Rn; Two-way ANOVA, n = 5–6 per group. Arg1; Two-way ANOVA, stress [F (1, 17) = 96.68, p < 0.0001] and interaction (stress x genotype) [F (1, 17) = 31.65, p < 0.0001]; ***p < 0.001 (vs C3ar1MGWT-NS) and ##p < 0.01 (vs C3ar1MGWT-CUS); n = 5–6 per group. E mRNA levels of chemokines in the PFC of C3ar1MGWT and C3ar1MGKO mice exposed to NS or CUS. CCL2; Two-way ANOVA, stress [F (1, 18) = 5.144, p = 0.0359]; genotype [F (1, 18) = 16.53, p = 0.0007] and interaction (stress x genotype) [F (1, 18) = 7.654, p = 0.0127]; *p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-NS) and ##p < 0.01 (vs C3ar1MGWT-CUS); n = 5–6 per group. CXCL10; Two-way ANOVA, genotype [F (1, 18) = 31.98, p < 0.0001] and interaction (stress x genotype) [F (1, 18) = 5.347, p = 0.0328]; *p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-NS) and ###p < 0.001 (vs C3ar1MGWT-CUS); n = 5–6 per group. CCL8; Two-way ANOVA, stress [F (1, 18) = 4.582, p = 0.0463] and genotype [F (1, 18) = 26.42, p < 0.0001]; n = 5–6 per group. CXCL1; Two-way ANOVA, genotype [F (1, 18) = 10.43, p = 0.0047] and interaction (stress x genotype) [F (1, 18) = 4.763, p = 0.0426]; p = 0.0624 (vs C3ar1MGWT-NS) and ##p < 0.01 (vs C3ar1MGWT-CUS); n = 5–6 per group. CXCL2; Two-way ANOVA, genotype [F (1, 18) = 11.72, p = 0.0030]; ##p < 0.01 (vs C3ar1MGWT-CUS); n = 5–6 per group. F–J Microglial C3ar1 deletion attenuated CUS-induced decrease in synaptic markers in the PFC. F Representative western blot images of PSD95, synaptophysin and actin. G Quantification of PSD95 protein levels. Two-way ANOVA, interaction (stress x genotype) [F (1, 17) = 10.88, p = 0.0042]; genotype [F (1, 17) = 8.909, p = 0.0083]; *p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-NS); #p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-CUS); n = 5–6 per group. H Quantification of synaptophysin protein levels. Two-way ANOVA, genotype [F (1, 16) = 8.688, p = 0.0095]; #p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-CUS); n = 5 per group. I Representative images of high-magnification z-stack projections of secondary branches of apical dendrites in the superficial layer and deep layers of PFC. J Spine density (number of spines per 10 μm of dendrite). One-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-NS); #p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-CUS); n = 5 per group.

Microglia function depends on the inflammatory cues and pathophysiological conditions [93, 94]. To examine whether C3ar1 deletion in microglia results in changes in microglia function, we examined the expression of key proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory markers in the PFC of C3ar1MGKO mice (Fig. 2D). Although we did not find any significant change in the mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory (iNOS and TNFa) and anti-inflammatory (IL4Ra, ILR1n and Arg) markers in the PFC of C3ar1MGKO mice, significant increases in iNOS, TNFa and IL4Ra mRNA levels, but decrease in Arg mRNA levels were found in the PFC of control mice following CUS (p < 0.05; Fig. 2D). However, C3ar1 deletion in microglia attenuated CUS-induced changes in the above markers (p < 0.05; Fig. 2D). Collectively, these findings indicate that microglial C3ar1 plays a critical role in mediating CUS-induced social behavior deficits, and proinflammatory phenotype in the PFC.

Deletion of C3ar1 in microglia attenuates CUS-induced increases in chemokines in the PFC

Given the significant macrophage infiltration into the PFC following CUS and the critical role of chemokine signaling in this process [16, 95, 96], we examined the expression of chemokines and their receptors in the PFC of mice with microglia C3ar1 deletion. We found increased levels of Ccl2, Cxcl10, and Cxcl1 in the PFC of control mice following CUS, while microglial C3ar1 deletion attenuated these stress-induced changes in chemokine levels (p < 0.05; Fig. 2E).

Deletion of C3ar1 in microglia attenuates CUS-induced reduction in synaptic proteins in the PFC

Chronic stress is known to induce decreases in the levels of synaptic proteins in the PFC [41, 81]. To assess whether microglial C3ar1 is essential for mediating stress-induced synaptic changes, we analyzed the expression levels of the presynaptic marker protein synaptophysin and the postsynaptic marker protein PSD-95 in the PFC. We found that microglial C3ar1 depletion attenuates CUS-induced decreases in PSD95 protein levels in mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 2F, G). No significant change in synaptophysin protein levels was observed in control mice following CUS (Fig. 2F, H). However, a significant increase in synaptophysin levels was found in C3ar1MGKO mice following CUS as compared to CUS-exposed C3ar1MGWT mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 2F, H). Dendritic spines, which are often indicative of synapse structure and plasticity, acts as a marker for changes reflecting neural dysfunction. Golgi staining was used to examine whether the changes in PSD95 were accompanied by changes in the spine density in the PFC (Fig. 2I). Dendritic spine numbers were reduced in CUS-exposed control mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 2I, J), consistent with the immunoblot results on PSD95. However, no significant change in the spine numbers were found in C3ar1MGKO mice following CUS (Fig. 2I, J).

Transcriptional profiling identifies potential molecular targets of microglial C3ar1 signaling under chronic stress conditions

To identify molecular changes resulting from of microglial C3ar1 deletion, we conducted whole-transcriptome gene expression analysis of the PFC in control and C3ar1MGKO mice exposed to CUS (Fig. 3A). For DEG analysis, log2Fold change cut off was set to 1 and adjusted p-value cut off was set to 0.05. Accordingly, we obtained 90 upregulated and 19 downregulated genes (Fig. 3A). Among DEGs that were modulated by CUS, we identified reduced expression of Nr4a1, Fos and Egr2 in the PFC (p < 0.05; Fig. 3A). Interestingly, these reductions were attenuated in C3ar1MGKO mice. The changes in the expression of the above genes were further confirmed by RT-PCR experiments (p < 0.05; Fig. 3B–E).

A Heatmap showing expression of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from PFC bulk RNA sequencing. (B–E) Validation of key genes by qRT-PCR. B mRNA expression of Egr1 in the PFC. One-way ANOVA, n = 3–4 per group. C mRNA expression of Egr2 in the PFC. One-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-NS); n = 3–4 per group. D mRNA expression of Fos in the PFC. One-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-NS); #p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-CUS); n = 3–4 per group. E mRNA expression of Nr4a1 in the PFC. One-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-NS); #p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MGWT-CUS); n = 3–4 per group.

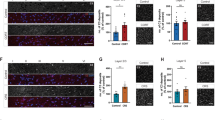

Deletion of C3ar1 in Mo/MΦ induces social behavior deficits

To delete C3ar1 in Mo/MΦ (C3ar1MφKO), we treated Ccr2Cre: C3ar1fl mice with tamoxifen, while control mice received corn oil (Fig. S4A). Flow cytometry analysis showed efficient recombination, with complete absence of C3ar1 in Ly6+ cells in C3ar1MφKO mice (p < 0.01; Fig. S4B,C). To assess the role of C3ar1 in Mo/MΦ on social behavior, we conducted a three-chamber test in control and C3ar1MφKO mice (Fig. 4A). Under naïve (no stress exposure) conditions, C3ar1MφKO showed sociability deficits as compared to their controls (Fig. 4A). To determine the effects of C3ar1 deletion in Mo/MΦ on stress-induced social behavior deficits, control and C3ar1MφKO mice were exposed to CUS for three weeks. CUS induced deficits in social behavior in control mice in the three-chamber test (Fig. 4A). In contrast to the findings from C3ar1MGKO mice, we observed no significant protective effect of in C3ar1 ablation in Mo/MΦ on CUS-induced social behavior deficits (Fig. 4A). Although we did not find a significant difference in interaction time between NS-exposed C3ar1MφWT and CUS-exposed C3ar1MφWT mice, the interaction time was significantly lower in CUS-exposed C3ar1MφKO mice as compared to NS-exposed C3ar1MφWT mice (Fig. 4B). Also, we did not find any significant difference in spatial working memory between C3ar1MφKO and controls in the Y-maze test (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that in contrast to the role of C3ar1 in microglia, C3ar1 in Mo/MΦ is critical for sociability in naïve mice.

A Time in chamber in the three-chamber test. Three-way ANOVA (stress x genotype x chamber), chamber [F (2, 96) = 74.45, p < 0.0001]; **p < 0.01 (mouse chamber vs empty chamber); n = 9 per group. B Reciprocal social interaction test. Two-way ANOVA, genotype [F (1, 32) = 5.871, p = 0.0212]; stress [F (1, 32) = 8.273, P = 0.0071]; $p < 0.01 (vs C3ar1MφWT -NS); n = 9 per group. C Y-maze test. Two-way ANOVA, n = 9 per group.

Deletion of C3ar1 in Mo/MΦ fails to attenuate CUS-induced changes in inflammatory and synaptic markers

To determine whether the deficits in social behavior in naïve C3ar1MφKO mice are associated with immune dysregulation, we examined the status of infiltrating immune cells and the resident microglia in the PFC of control and C3ar1MφKO mice (Fig. 5A). Flow cytometry analysis showed no significant difference in the number of infiltrating peripheral macrophages (CD11b+CD45high) (Fig. 5B) or microglia (CD11b+CD45low) (Fig. 5C) in the PFC of naïve C3ar1MφKO mice compared to their control groups. CUS increased the number of infiltrating peripheral macrophages in the PFC of control mice (p = 0.0537), but the CUS-induced increases in the number of infiltrating peripheral macrophages was not attenuated in C3ar1MφKO mice (Fig. 5B). We found significant increase in the number of microglia in the PFC of CUS-exposed C3ar1MφKO mice as compared to CUS-exposed control mice (Fig. 5C).

A–C Flow cytometry analysis of infiltrating monocytes and resident microglia in the PFC of C3ar1MφWT and C3ar1MφKO mice exposed to NS or CUS. A Flow cytometry gating strategy showing CD11b+ve cells were analyzed using CD45 to differentiate infiltrating macrophages (CD45high) from resident microglia (CD45low). B % of CD11b+ve cells expressing CD45high in PFC of C3ar1MφWT and C3ar1MφKO mice exposed to NS or CUS. Two-way ANOVA, stress [F (1, 14) = 9.311, p = 0.0086]; p = 0.0537 vs C3ar1MφWT -NS; n = 4–5 per group. C % of CD11b+ve cells expressing CD45low in the PFC of C3ar1MφWT and C3ar1MφKO mice exposed to CUS or NS. Two-way ANOVA; genotype [F (1, 14) = 15.71, p = 0.0014], #p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MφWT -CUS); n = 4–5 per group. D mRNA levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the PFC of C3ar1MφWT and C3ar1MφKO mice exposed to NS or CUS. iNOS; Two-way ANOVA, stress [F (1, 20) = 9.158, p = 0.0067, **p < 0.01 (vs C3ar1MφWT -NS); n = 6 per group. TNFα; Two-way ANOVA, stress [F (1, 20) = 10.62, p = 0.0039), ***p < 0.001 (vs C3ar1MφWT -NS) n = 6 per group. IL4Rα; Two-way ANOVA, n = 6 per group. IL1Rn; Two-way ANOVA, n = 6 per group. Arg1; Two-way ANOVA, n = 6 per group. E mRNA levels of chemokines in the PFC of C3ar1MφWT and C3ar1MφKO mice exposed to NS or CUS. CCL2; Two-way ANOVA, n = 5–6 per group. CXCL10; Two-way ANOVA, stress [F (1, 17) = 4.854, p = 0.0417] and interaction (stress x genotype) [F (1, 17) = 8.531, p = 0.0095], *p < 0.05 (vs C3ar1MφWT -NS) and n = 5–6 per group. CCL8; Two-way ANOVA, stress [F (1, 19) = 13.02, p = 0.0019) and genotype (F (1, 19) = 4.612, p = 0.0449), p = 0.07 (vs C3ar1MφWT -NS) n = 5–6 per group. CXCL1; Two-way ANOVA, stress [F (1, 19) = 16.22, p = 0.0007], **p < 0.01 (vs C3ar1MφWT -NS), n = 5–6 per group. CXCL2; Two-way ANOVA, stress [F (1, 19) = 16.77, p = 0006), **p < 0.01 (vs C3ar1MφWT -NS), n = 5–6 per group. F Representative western blot images of PSD95, synaptophysin and actin proteins in the PFC. G Quantification of PSD95 protein levels. Two-way ANOVA, interaction (stress x genotype) (F (1, 8) = 6.930, p = 0.0301); p = 0.0660 (vs C3ar1MφWT -NS), n = 3 per group. H Quantification of synaptophysin protein levels. Two-way ANOVA, n = 3 per group.

Two-way ANOVA found no significant changes in the mRNA levels of iNOS, TNFα, IL4Ra, ILR1n and Arg in the PFC of naïve C3ar1MφKO mice (Fig. 5D). However, significant increase in iNOS and TNFa mRNA levels were found in the PFC of control mice following CUS (p < 0.05; Fig. 5D). C3ar1 deletion in Mo/MΦ failed to attenuate the above increases in proinflammatory markers (Fig. 5D). Similarly, increases in the mRNA levels of chemokines, Cxcl10, Cxcl1 and Cxcl2 in the PFC of control mice following CUS were not attenuated by C3ar1 deletion in Mo/MΦ (Fig. 5E). In addition, CUS-induced decrease in PSD-95 protein levels (p = 0.066) were not attenuated in C3ar1MφKO mice (Fig. 5F, G). We did not find any change in synaptophysin protein levels between the groups (Fig. 5H). Together, these results indicate that deletion of C3ar1 in Mo/MΦ fails to attenuate CUS-induced changes in inflammatory and synaptic markers.

Discussion

Deficits in synaptic function and altered neuronal connectivity have been reported in rodents following chronic stress exposure [34,35,36,37]. Although the contribution of synaptic loss to behavioral abnormalities in chronic stress conditions is well established, the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown. We found that complement signaling via C3ar1 plays a critical role in chronic stress-induced changes in synaptic density and social behavior. Furthermore, our findings show opposite roles of microglial versus monocyte/macrophagic C3ar1 on social behavior. The data show that lack of microglial C3ar1 attenuates CUS-induced social behavior deficits and neuroinflammation whereas lack of C3ar1 in Mo/MΦ induces social behavior deficits.

Microglia known as the resident macrophages of the CNS are critical regulators of synaptic circuits in the brain [30, 97]. In addition to microglia, the Mo/MΦ also play key roles in CNS homeostasis and disease. Recent studies examining the signature genes to differentiate microglia from Mo/MΦ have indicated that CX3CR1 is found in microglia whereas CCR2 is expressed exclusively in Mo/MΦ [98]. We used Cx3Cr1CreER + / and CCR2 CreER + / mouse lines to dissect the role of C3ar1 in microglia and Mo/MΦ, respectively on social behavior. Because C3ar1 is expressed on microglia in the brain and microglial dysregulation has been shown to mediate stress-induced behavioral abnormalities, we hypothesized that microglial C3ar1 could be the mediator of chronic stress-induced social behavior deficits. In support of this hypothesis, deletion of C3ar1 in microglia in C3ar1MGKO mice attenuated social behavior deficits following chronic stress.

To understand the mechanisms underlying microglial C3ar1-mediated social behavior, we examined the status of infiltrating macrophages as well as gene expression of immune markers. Our data show that C3ar1 in microglia plays a key role in promoting the microglial dysfunction under stress conditions as evidenced by increases in iNOS and TNFα mRNA levels in the PFC following CUS. Also, we found significant upregulation of chemokines in the PFC after stress. The increased chemokine production by chronic stress could contribute to the increased infiltration of peripheral immune cells in the PFC. Chronic stress is known to promote the infiltration of peripheral macrophages into the brain areas [67, 92] implicated in social behavior. The increases in the proinflammatory markers in the PFC could be produced by several cells including microglia. We cannot rule out the possibility of infiltrating peripheral macrophages as the contributing sources of proinflammatory cytokines under chronic stress conditions.

RNA seq analysis of PFC tissues revealed significant decreases in Nr4a1, Fos and Egr2 in the stress-exposed mice. Nr4a1 is an immediate early gene, which plays an important role in synaptic function [99, 100]. Inhibition of Nr4a1 has been shown to decrease spine density in neurons whereas neuronal Nr4a1 rescue blocked synapse removal by complement-dependent microglial phagocytosis [100]. Accordingly, we found a decrease in spine density in the PFC following chronic stress exposure which was attenuated in C3ar1MGKO mice. These results suggest that under chronic stress conditions, synapses are phagocytosed by microglia through a complement-dependent mechanism leading to synapse loss. It is not known whether complement tagging of synapses is Nr4a1-dependent and how microglial C3ar1 is involved in this regulatory mechanism of chronic stress-induced synapse loss. Fos and Fosl1 belong to the Fos family, which consists of four members, Fos, FosB, FosL1 and FosL2 [101]. They act as subunits of the AP-1 transcription factor, which plays a role in synaptic plasticity and memory [102]. Moreover, c-fos acts as a marker for the adaptive capabilities of the brain under stress conditions [103, 104]. Taken together, these data suggest that immediate early genes regulated by microglial C3ar1 are mediators of stress-induced synaptic plasticity.

To further understand the role of C3ar1 in mediating stress-induced social behavior deficits, we next examined the role of C3ar1 in Mo/MΦ, for which we used C3ar1MφKO mice. Since chronic stress is known to promote infiltration of macrophages into the brain and C3ar1 is expressed on Mo/MΦ [62], we expected the role of C3ar1 in Mo/MΦ similar to microglia, attenuating stress-induced social behavior deficits as in C3ar1MGKO mice. However, we found opposite effects with naive C3ar1MφKO mice showing abnormalities in social behavior. In addition, C3ar1MφKO mice are susceptible to chronic stress-induced social behavior deficits. The impairments in social behavior in naïve C3ar1MφKO mice were not accompanied with any significant changes in the infiltration of macrophages in the PFC. Together, these findings provide causal evidence that lack of C3ar1 signaling in Mo/MΦ results in changes in neuroinflammatory markers and social behavior in mice.

Although complement activation has been shown to promote inflammatory response [62, 105, 106] and synaptic changes [43, 46, 107, 108], normal functioning of complement pathway is important for combating infections. In addition to myeloid cells, non-myeloid cells including endothelial cells, astrocytes and neurons also express C3ar1 [63, 65, 109, 110]. Since growing evidence indicate that chronic stress conditions alter immune system and changes in innate immune signaling impact brain plasticity [14, 111,112,113], our current study focused on the role of C3ar1 on myeloid cells in stress-induced social behavior. The underlying mechanism by which stress regulates complement signaling is yet to be determined. Increases in C3 have been found in the PFC following chronic stress conditions [62]. Previous studies indicate that NF-κB activation leads to increases in C3 release [114,115,116,117]. Interestingly, NF-κB signaling is a critical mediator of the anti-neurogenic and behavioral actions of chronic stress [118]. Also, NF-κB controls the activity of numerous genes crucial for inflammation and stress responses including iNOS and TNFα. These findings suggest a potential role for NF-κB in chronic stress induced C3ar1 signaling.

The complement activation products, C3a and C3b regulate microglia function through distinct receptor pathways. C3b interacts with complement receptor 3 (CR3) on microglia, facilitating synaptic pruning by opsonization in the developing brain, where weak synapses are marked for elimination [119, 120]. This C3b/CR3 pathway is well-established as a key mechanism for microglial-driven synaptic refinement. On the other hand, C3a binds to its receptor, C3aR1, which plays a dual role in inflammatory signaling and microglia function. Recent studies indicate that the C3a/C3aR1 pathway is also involved in synaptic pruning, particularly in pathological conditions like neurodegeneration. For instance, inhibiting C3aR1 has been shown to reduce microglial palmitoylation cycle hyperactivation, limit excessive synaptic pruning, and promote synaptogenesis in the PFC [121]. Additionally, C3aR1 knockout protects excitatory synapses by preventing microglial phagocytic signaling in models of postoperative cognitive dysfunction [122]. Our results align with the above findings by highlighting the critical role of C3aR1 in microglia function and synaptic pruning in pathological conditions. We suggest that while C3b/CR3 is the primary mediator of synaptic pruning under normal conditions, C3a/C3aR1 contributes to aberrant pruning and inflammatory signaling in disease contexts. This emphasizes the dual role of C3aR1 in driving inflammation and shaping synaptic connections.

Our study has a few limitations. First, the effects of microglial C3ar1 deletion on stress susceptibility vs. resilience are not known. Since microglia can adapt to their environment and change their function and physiological states it is important to understand the role of C3ar1 in microglial response to psychological stress resilience [123]. Second, RNA-seq analysis was not conducted in naïve C3ar1MGKO group to examine the effects of C3ar1 deletion in microglia on gene expression at the baseline. Third, Cre- littermates injected with tamoxifen were not included as controls to evaluate the potential off-target adverse effects. Fourth, the present study was conducted only in male mice. Because microglia display sex-dependent structural and functional differences [124], future experiments including both sexes are essential in understanding the sex-specific effects of microglial C3ar1 on chronic stress-induced social behavior deficits.

In summary, using cell-specific C3ar1 deletion models, our study suggested that C3ar1 signaling in microglia and Mo/MΦ have opposite roles in stress-induced social behavior deficits. C3ar1 expressed in Mo/MΦ is protective while that expressed in microglia is involved in promoting stress susceptibility. We found that stress-induced behavior deficits were associated with changes in neuroinflammatory and also synaptic markers in the PFC suggesting that myeloid cell C3ar1-dependent changes in immune-neuron interaction following stress regulates social behavior. Future studies designing complement-based therapeutics must consider the opposite functions of C3ar1 signaling depending on the location in central or peripheral myeloid cells.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Sandi C, Haller J. Stress and the social brain: behavioural effects and neurobiological mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:290–304.

Beery AK, Kaufer D. Stress, social behavior, and resilience: insights from rodents. Neurobiol Stress. 2015;1:116–27.

Von Dawans B, Trueg A, Kirschbaum C, Fischbacher U, Heinrichs M. Acute social and physical stress interact to influence social behavior: the role of social anxiety. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0204665.

Ceccato S, Kettner SE, Kudielka BM, Schwieren C, Voss A. Social preferences under chronic stress. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0199528.

Sabanovic M, Liu H, Mlambo V, Aqel H, Chaudhury D. What it takes to be at the top: the interrelationship between chronic social stress and social dominance. Brain Behav. 2020;10:e01896.

Buchanan TW, Preston SD. Stress leads to prosocial action in immediate need situations. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:5.

Borrow AP, Bales NJ, Stover SA, Handa RJ. Chronic variable stress induces sex-specific alterations in social behavior and neuropeptide expression in the mouse. Endocrinology. 2018;159:2803–14.

Takahashi A, Flanigan ME, McEwen BS, Russo SJ. Aggression, social stress, and the immune system in humans and animal models. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:56.

Schneiderman N, Ironson G, Siegel SD. Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:607–28.

Gasser BA, Kurz J, Senn W, Escher G, Mohaupt MG. Stress-induced alterations of social behavior are reversible by antagonism of steroid hormones in C57/BL6 mice. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2021;394:127–35.

Jeon D, Choi J, Yang AR, Yoo JS, Kim S, Lee SK, et al. Chronic social stress during early development elicits unique behavioral changes in adulthood. Encephalitis. 2022;2:45–53.

Si L, Xiao L, Xie Y, Xu H, Yuan G, Xu W, et al. Social isolation after chronic unpredictable mild stress perpetuates depressive-like behaviors, memory deficits and social withdrawal via inhibiting ERK/KEAP1/NRF2 signaling. J Affect Disord. 2023;324:576–88.

van Boxelaere M, Clements J, Callaerts P, D’Hooge R, Callaerts-Vegh Z. Unpredictable chronic mild stress differentially impairs social and contextual discrimination learning in two inbred mouse strains. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0188537.

Haykin H, Rolls A. The neuroimmune response during stress: a physiological perspective. Immunity. 2021;54:1933–47.

Tong RL, Kahn UN, Grafe LA, Hitti FL, Fried NT, Corbett BF. Stress circuitry: mechanisms behind nervous and immune system communication that influence behavior. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1240783.

Ishikawa Y, Furuyashiki T. The impact of stress on immune systems and its relevance to mental illness. Neurosci Res. 2022;175:16–24.

Shimo Y, Cathomas F, Lin HY, Chan KL, Parise LF, Li L, et al. Social stress induces autoimmune responses against the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2023;120:e2305778120.

Bergamini G, Mechtersheimer J, Azzinnari D, Sigrist H, Buerge M, Dallmann R, et al. Chronic social stress induces peripheral and central immune activation, blunted mesolimbic dopamine function, and reduced reward-directed behaviour in mice. Neurobiol Stress. 2018;8:42–56.

Goodman EJ, DiSabato DJ, Sheridan JF, Godbout JP. Novel microglial transcriptional signatures promote social and cognitive deficits following repeated social defeat. Commun Biol. 2024;7:1199.

Grizzell JA, Clarity TT, Rodriguez RM, Marshall ZQ, Cooper MA. Effects of social dominance and acute social stress on morphology of microglia and structural integrity of the medial prefrontal cortex. Brain Behav Immun. 2024;122:353–67.

Wang YL, Han QQ, Gong WQ, Pan DH, Wang LZ, Hu W, et al. Microglial activation mediates chronic mild stress-induced depressive- and anxiety-like behavior in adult rats. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15:21.

Mittli D. Inflammatory processes in the prefrontal cortex induced by systemic immune challenge: focusing on neurons. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2023;34:100703.

Schramm E, Waisman A. Microglia as central protagonists in the chronic stress response. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;9:e200023.

Couch Y, Anthony DC, Dolgov O, Revischin A, Festoff B, Santos AI, et al. Microglial activation, increased TNF and SERT expression in the prefrontal cortex define stress-altered behaviour in mice susceptible to anhedonia. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;29:136–46.

Woodburn SC, Bollinger JL, Wohleb ES. The semantics of microglia activation: neuroinflammation, homeostasis, and stress. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:258.

Bollinger JL, Horchar MJ, Wohleb ES. Diazepam limits microglia-mediated neuronal remodeling in the prefrontal cortex and associated behavioral consequences following chronic unpredictable stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:1766–76.

de Pablos RM, Villaran RF, Arguelles S, Herrera AJ, Venero JL, Ayala A, et al. Stress increases vulnerability to inflammation in the rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5709–19.

Pan Y, Chen XY, Zhang QY, Kong LD. Microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation mediates IL-1beta-related inflammation in prefrontal cortex of depressive rats. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;41:90–100.

Tillmon H, Soteros BM, Shen L, Cong Q, Wollet M, General J, et al. Complement and microglia activation mediate stress-induced synapse loss in layer 2/3 of the medial prefrontal cortex in male mice. Nat Commun. 2024;15:9803.

Yamada J, Hayashi Y, Jinno S, Wu Z, Inoue K, Kohsaka S, et al. Reduced synaptic activity precedes synaptic stripping in vagal motoneurons after axotomy. Glia. 2008;56:1448–62.

Ding X, Wang J, Huang M, Chen Z, Liu J, Zhang Q, et al. Loss of microglial SIRPalpha promotes synaptic pruning in preclinical models of neurodegeneration. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2030.

Hong S, Beja-Glasser VF, Nfonoyim BM, Frouin A, Li S, Ramakrishnan S, et al. Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science. 2016;352:712–6.

Werneburg S, Jung J, Kunjamma RB, Ha SK, Luciano NJ, Willis CM, et al. Targeted complement inhibition at synapses prevents microglial synaptic engulfment and synapse loss in demyelinating disease. Immunity. 2020;52:167–82.e7.

Woo E, Sansing LH, Arnsten AFT, Datta D. Chronic stress weakens connectivity in the prefrontal cortex: architectural and molecular changes. Chronic Stress. 2021;5:24705470211029254.

Page CE, Coutellier L. Prefrontal excitatory/inhibitory balance in stress and emotional disorders: evidence for over-inhibition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;105:39–51.

Liston C, Miller MM, Goldwater DS, Radley JJ, Rocher AB, Hof PR, et al. Stress-induced alterations in prefrontal cortical dendritic morphology predict selective impairments in perceptual attentional set-shifting. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7870–4.

Chen Y, Zheng Y, Yan J, Zhu C, Zeng X, Zheng S, et al. Early life stress induces different behaviors in adolescence and adulthood may related with abnormal medial prefrontal cortex excitation/inhibition balance. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:720286.

Csabai D, Wiborg O, Czeh B. Reduced synapse and axon numbers in the prefrontal cortex of rats subjected to a chronic stress model for depression. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:24.

Rodrigues B, Leitao RA, Santos M, Trofimov A, Silva M, Inacio AS, et al. MiR-186-5p inhibition restores synaptic transmission and neuronal network activity in a model of chronic stress. Mol Psychiatry. 2025;30:1034–46.

Rodrigues D, Santa C, Manadas B, Monteiro P. Chronic stress alters synaptic inhibition/excitation balance of pyramidal neurons but not PV interneurons in the infralimbic and prelimbic cortices of C57BL/6J mice. eNeuro. 2024;11:ENEURO.0053-24.2024.

Woodburn SC, Bollinger JL, Wohleb ES. Synaptic and behavioral effects of chronic stress are linked to dynamic and sex-specific changes in microglia function and astrocyte dystrophy. Neurobiol Stress. 2021;14:100312.

Wohleb ES, Terwilliger R, Duman CH, Duman RS. Stress-induced neuronal colony stimulating factor 1 provokes microglia-mediated neuronal remodeling and depressive-like behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83:38–49.

Gomez-Arboledas A, Acharya MM, Tenner AJ. The role of complement in synaptic pruning and neurodegeneration. Immunotargets Ther. 2021;10:373–86.

Fourgeaud L, Boulanger LM. Synapse remodeling, compliments of the complement system. Cell. 2007;131:1034–6.

Presumey J, Bialas AR, Carroll MC. Complement system in neural synapse elimination in development and disease. Adv Immunol. 2017;135:53–79.

Wen L, Bi D, Shen Y. Complement-mediated synapse loss in Alzheimer’s disease: mechanisms and involvement of risk factors. Trends Neurosci. 2024;47:135–49.

Soteros BM, Sia GM. Complement and microglia dependent synapse elimination in brain development. WIREs Mech Dis. 2022;14:e1545.

Kettenmann H, Kirchhoff F, Verkhratsky A. Microglia: new roles for the synaptic stripper. Neuron. 2013;77:10–8.

Cornell J, Salinas S, Huang HY, Zhou M. Microglia regulation of synaptic plasticity and learning and memory. Neural Regen Res. 2022;17:705–16.

Shi Q, Chowdhury S, Ma R, Le KX, Hong S, Caldarone BJ, et al. Complement C3 deficiency protects against neurodegeneration in aged plaque-rich APP/PS1 mice. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaaf6295.

Wilton DK, Mastro K, Heller MD, Gergits FW, Willing CR, Fahey JB, et al. Microglia and complement mediate early corticostriatal synapse loss and cognitive dysfunction in Huntington’s disease. Nat Med. 2023;29:2866–84.

Hong S, Dissing-Olesen L, Stevens B. New insights on the role of microglia in synaptic pruning in health and disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2016;36:128–34.

Schafer DP, Lehrman EK, Kautzman AG, Koyama R, Mardinly AR, Yamasaki R, et al. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron. 2012;74:691–705.

Gao C, Jiang J, Tan Y, Chen S. Microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:359.

Mordelt A, de Witte LD. Microglia-mediated synaptic pruning as a key deficit in neurodevelopmental disorders: hype or hope? Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2023;79:102674.

Butler CA, Popescu AS, Kitchener EJA, Allendorf DH, Puigdellivol M, Brown GC. Microglial phagocytosis of neurons in neurodegeneration, and its regulation. J Neurochem. 2021;158:621–39.

Rajendran L, Paolicelli RC. Microglia-mediated synapse loss in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2018;38:2911–9.

Dunkelberger JR, Song WC. Complement and its role in innate and adaptive immune responses. Cell Res. 2010;20:34–50.

Ruan CC, Gao PJ. Role of complement-related inflammation and vascular dysfunction in hypertension. Hypertension. 2019;73:965–71.

Gao S, Cui Z, Zhao MH. The complement C3a and C3a receptor pathway in kidney diseases. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1875.

Wang J, Chen HS, Li HH, Wang HJ, Zou RS, Lu XJ, et al. Microglia-dependent excessive synaptic pruning leads to cortical underconnectivity and behavioral abnormality following chronic social defeat stress in mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2023;109:23–36.

Crider A, Feng T, Pandya CD, Davis T, Nair A, Ahmed AO, et al. Complement component 3a receptor deficiency attenuates chronic stress-induced monocyte infiltration and depressive-like behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;70:246–56.

Harder JM, Williams PA, Braine CE, Yang HS, Thomas JM, Foxworth NE, et al. Complement peptide C3a receptor 1 promotes optic nerve degeneration in DBA/2J mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17:336.

Gasque P, Singhrao SK, Neal JW, Wang P, Sayah S, Fontaine M, et al. The receptor for complement anaphylatoxin C3a is expressed by myeloid cells and nonmyeloid cells in inflamed human central nervous system: analysis in multiple sclerosis and bacterial meningitis. J Immunol. 1998;160:3543–54.

Quell KM, Karsten CM, Kordowski A, Almeida LN, Briukhovetska D, Wiese AV, et al. Monitoring C3aR expression using a floxed tdTomato-C3aR reporter knock-in mouse. J Immunol. 2017;199:688–706.

Hassamal S. Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1130989.

Wohleb ES, McKim DB, Sheridan JF, Godbout JP. Monocyte trafficking to the brain with stress and inflammation: a novel axis of immune-to-brain communication that influences mood and behavior. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:447.

Weber MD, Godbout JP, Sheridan JF. Repeated social defeat, neuroinflammation, and behavior: monocytes carry the signal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:46–61.

Hu H, Yang X, He Y, Duan C, Sun N. Psychological stress induces depressive-like behavior associated with bone marrow-derived monocyte infiltration into the hippocampus independent of blood-brain barrier disruption. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19:208.

Barrett TJ, Corr EM, van Solingen C, Schlamp F, Brown EJ, Koelwyn GJ, et al. Chronic stress primes innate immune responses in mice and humans. Cell Rep. 2021;36:109595.

Chen O, Luo X, Ji RR. Macrophages and microglia in inflammation and neuroinflammation underlying different pain states. Med Rev (2021). 2023;3:381–407.

Radley J, Morilak D, Viau V, Campeau S. Chronic stress and brain plasticity: mechanisms underlying adaptive and maladaptive changes and implications for stress-related CNS disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;58:79–91.

Vyas A, Mitra R, Shankaranarayana Rao BS, Chattarji S. Chronic stress induces contrasting patterns of dendritic remodeling in hippocampal and amygdaloid neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6810–8.

Li F, Wang Y, Wang X, Zhao Y, Xie F, Qian LJ. Dynamic effects of chronic unpredictable mild stress on the hippocampal transcriptome in rats. Mol Med Rep. 2022;25:110.

Wang SE, Ko SY, Jo S, Jo HR, Han J, Kim YS, et al. Downregulation of SIRT2 by chronic stress reduces expression of synaptic plasticity-related genes through the upregulation of Ehmt2. Exp Neurobiol. 2019;28:537–46.

Cerqueira JJ, Mailliet F, Almeida OF, Jay TM, Sousa N. The prefrontal cortex as a key target of the maladaptive response to stress. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2781–7.

Horchar MJ, Wohleb ES. Glucocorticoid receptor antagonism prevents microglia-mediated neuronal remodeling and behavioral despair following chronic unpredictable stress. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;81:329–40.

Dioli C, Patricio P, Sousa N, Kokras N, Dalla C, Guerreiro S, et al. Chronic stress triggers divergent dendritic alterations in immature neurons of the adult hippocampus, depending on their ultimate terminal fields. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9:143.

Bath KG, Russo SJ, Pleil KE, Wohleb ES, Duman RS, Radley JJ. Circuit and synaptic mechanisms of repeated stress: perspectives from differing contexts, duration, and development. Neurobiol Stress. 2017;7:137–51.

Pandya CD, Hoda N, Crider A, Peter D, Kutiyanawalla A, Kumar S, et al. Transglutaminase 2 overexpression induces depressive-like behavior and impaired TrkB signaling in mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:745–53.

Tripathi A, Bartosh A, Mata J, Jacks C, Madeshiya AK, Hussein U, et al. Microglial type I interferon signaling mediates chronic stress-induced synapse loss and social behavior deficits. Mol Psychiatry. 2025;30:423–34.

Lo SC, Scearce-Levie K, Sheng M. Characterization of social behaviors in caspase-3 deficient mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:18335.

Park MJ, Seo BA, Lee B, Shin HS, Kang MG. Stress-induced changes in social dominance are scaled by AMPA-type glutamate receptor phosphorylation in the medial prefrontal cortex. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15008.

Punt AM, Judson MC, Sidorov MS, Williams BN, Johnson NS, Belder S, et al. Molecular and behavioral consequences of Ube3a gene overdosage in mice. JCI Insight. 2022;7:e158953.

Lin YJ, Huang TN, Hsueh YP. Quantification of the density and morphology of dendritic spines and synaptic protein distribution using Thy1-YFP transgenic mice. STAR Protoc. 2023;4:102290.

Roy ER, Wang B, Wan YW, Chiu G, Cole A, Yin Z, et al. Type I interferon response drives neuroinflammation and synapse loss in Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:1912–30.

Wingett SW, Andrews S. FastQ screen: a tool for multi-genome mapping and quality control. F1000Res. 2018;7:1338.

Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:i884–i90.

Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21.

Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–30.

Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550.

Medina-Rodriguez EM, Han D, Lowell J, Beurel E. Stress promotes the infiltration of peripheral immune cells to the brain. Brain Behav Immun. 2023;111:412–23.

Butovsky O, Weiner HL. Microglial signatures and their role in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19:622–35.

Paolicelli RC, Sierra A, Stevens B, Tremblay ME, Aguzzi A, Ajami B, et al. Microglia states and nomenclature: a field at its crossroads. Neuron. 2022;110:3458–83.

Murugan M, Ravula A, Gandhi A, Vegunta G, Mukkamalla S, Mujib W, et al. Chemokine signaling mediated monocyte infiltration affects anxiety-like behavior following blast injury. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:340–52.

Ramesh G, MacLean AG, Philipp MT. Cytokines and chemokines at the crossroads of neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and neuropathic pain. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:480739.

Graeber MB, Bise K, Mehraein P. Synaptic stripping in the human facial nucleus. Acta Neuropathol. 1993;86:179–81.

Kohno H, Koso H, Okano K, Sundermeier TR, Saito S, Watanabe S, et al. Expression pattern of Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 in inherited retinal degeneration. J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:188.

Chen J, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Huang L, Liu Y, Yang D, et al. Progressive reduction of nuclear receptor Nr4a1 mediates age-dependent cognitive decline. Alzheimers Dement. 2024;20:3504–24.

Han X, Xu T, Ding C, Wang D, Yao G, Chen H, et al. Neuronal NR4A1 deficiency drives complement-coordinated synaptic stripping by microglia in a mouse model of lupus. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:50.

Renaud SJ, Kubota K, Rumi MA, Soares MJ. The FOS transcription factor family differentially controls trophoblast migration and invasion. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:5025–39.

Alberini CM. Transcription factors in long-term memory and synaptic plasticity. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:121–45.

Perrotti LI, Hadeishi Y, Ulery PG, Barrot M, Monteggia L, Duman RS, et al. Induction of deltaFosB in reward-related brain structures after chronic stress. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10594–602.

Machida M, Lonart G, Sanford LD. Effects of stressor controllability on transcriptional levels of c-fos, Arc, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in mouse amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex. Neuroreport. 2018;29:112–7.

Markiewski MM, Lambris JD. The role of complement in inflammatory diseases from behind the scenes into the spotlight. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:715–27.

Sierra DP, Tripathi A, Pillai A. Dysregulation of complement system in neuropsychiatric disorders: a mini review. Biomark Neuropsychiatry. 2022;7:100056.

Carpanini SM, Torvell M, Bevan RJ, Byrne RAJ, Daskoulidou N, Saito T, et al. Terminal complement pathway activation drives synaptic loss in Alzheimer’s disease models. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2022;10:99.

Stevens B, Johnson MB. The complement cascade repurposed in the brain. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:624–5.

Pekna M, Pekny M. The complement system: a powerful modulator and effector of astrocyte function in the healthy and diseased central nervous system. Cells. 2021;10:1812.

Propson NE, Roy ER, Litvinchuk A, Kohl J, Zheng H. Endothelial C3a receptor mediates vascular inflammation and blood-brain barrier permeability during aging. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e140966.

Bains JS, Sharkey KA. Stress and immunity - the circuit makes the difference. Nat Immunol. 2022;23:1137–9.

Ravi M, Miller AH, Michopoulos V. The immunology of stress and the impact of inflammation on the brain and behavior. BJPsych Adv. 2021;27:158–65.

Dvorak NM, Domingo ND, Tapia CM, Wadsworth PA, Marosi M, Avchalumov Y, et al. TNFR1 signaling converging on FGF14 controls neuronal hyperactivity and sickness behavior in experimental cerebral malaria. J Neuroinflammation. 2023;20:306.

Lian H, Yang L, Cole A, Sun L, Chiang AC, Fowler SW, et al. NFkappaB-activated astroglial release of complement C3 compromises neuronal morphology and function associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2015;85:101–15.

Nitkiewicz J, Borjabad A, Morgello S, Murray J, Chao W, Emdad L, et al. HIV induces expression of complement component C3 in astrocytes by NF-kappaB-dependent activation of interleukin-6 synthesis. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:23.

Liu M, Wang H, Zhang J, Yang X, Li B, Wu C, et al. NF-kappaB signaling pathway-enhanced complement activation mediates renal injury in trichloroethylene-sensitized mice. J Immunotoxicol. 2018;15:63–72.

Gui D, Huang J, Guo Y, Chen J, Chen Y, Xiao W, et al. Astragaloside IV ameliorates renal injury in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats through inhibiting NF-kappaB-mediated inflammatory genes expression. Cytokine. 2013;61:970–7.

Koo JW, Russo SJ, Ferguson D, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Nuclear factor-kappaB is a critical mediator of stress-impaired neurogenesis and depressive behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:2669–74.

Ayyubova G, Fazal N. Beneficial versus detrimental effects of complement-microglial interactions in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Sci. 2024;14:434.

Lenz KM, Nelson LH. Microglia and beyond: innate immune cells as regulators of brain development and behavioral function. Front Immunol. 2018;9:698.

Zhang MM, Guo MX, Zhang QP, Chen XQ, Li NZ, Liu Q, et al. IL-1R/C3aR signaling regulates synaptic pruning in the prefrontal cortex of depression. Cell Biosci. 2022;12:90.

Li S, Liu H, Lv P, Yao Y, Peng L, Xia T, et al. Microglia mediate memory dysfunction via excitatory synaptic elimination in a fracture surgery mouse model. J Neuroinflammation. 2024;21:227.

Gonzalez Ibanez F, VanderZwaag J, Deslauriers J, Tremblay ME. Ultrastructural features of psychological stress resilience in the brain: a microglial perspective. Open Biol. 2024;14:240079.

Han J, Fan Y, Zhou K, Blomgren K, Harris RA. Uncovering sex differences of rodent microglia. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:74.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the funding support from US National Institutes of Health (MH120876, MH121959, MH128771), and the Merit Review Award (BX004758) from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development to AP. The contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. AP acknowledges the funding support from Louis A Faillace Endowed Chair in Psychiatry. ZZ was partially supported by NIH grants (R01LM012806, U01AG079847). FL was partially supported by NIH grants (R01 MH095995 R01MH111107, R01ES031823). The authors thank the lab members of the Bioinformatics Systems Medicine Laboratory (BSML) for the valuable help. The RNA-seq data was generated by the UTHealth Cancer Genomics Core funded by Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT RP180734 and RP240610). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors thank Dr. Lin Gan (Rochester Mouse Genome Editing Resource Core) for generating C3ar1fl mice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AP designed the research. AT, AB, DJ, and JM performed the experiments and analyzed the data. UH and ZZ performed RNA-seq analysis. FL participated in the data interpretation and manuscript editing. AT prepared the initial manuscript draft. AP edited the manuscript. All authors had an opportunity to review and provide input on the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animal studies were approved (#AWC-20-0148) by the Animal Welfare Committee (AWC) of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth Houston). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tripathi, A., Bartosh, A., Jose, D. et al. Opposing roles of microglial and macrophagic C3ar1 signaling in stress-induced synaptic and behavioral changes. Mol Psychiatry 30, 5137–5149 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03097-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03097-8