Abstract

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been recognized as a valuable tool for achieving ‘reification of clinical diagnosis’ of major depressive disorder (MDD). However, the reliability and validity of MRI results are often compromised by genetic, environmental, and clinical heterogeneity within test samples. Here, we combined MRI with other clinical findings using multimodal MRI fusion algorithm to construct a data-driven, bottom-up diagnostic approach. The covariation patterns between the multimodal MRI features and differential expression of exosomal microRNA (miRNA) were identified on a subset of 70 MDD patients and 71 healthy controls (HCs) (served as a training set) as classification features, whereas data from the other 45 MDD patients and 43 HCs served as a test set. Furthermore, longitudinal data from 28 MDD patients undergoing antidepressant treatment for six months were utilized to validate the identified biomarkers, and related signaling pathways were initially explored in depression-like mice. Plasma exosome-derived miR-151a-3p levels were found to be significantly lower in MDD patients compared to HCs and correlated with abnormal changes in functional MRI (fMRI) metrics in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), visual cortex, and default mode network, etc. Then, these multimodal MRI features associated with miR-151a-3p expression distinguished MDD patients from HCs with high classification accuracy of 92.05% in support vector machine (SVM) model, outperforming the diagnostic rate when only multimodal MRI features with intergroup differences were entered (70.45%). Furthermore, 10 out of 28 MDD patients exhibited a clinically significant response to the treatment (a reduction of over 50% in Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) score). The significant upregulation of plasma exosomal miR-151a-3p levels and changes of fMRI indicators were also observed in these 10 patients after treatment of six months. Animal experiments have shown that reducing the expression of miR-151-3p in ACC induces depression-like behaviors in mice, while elevating hsa-miR-151a-3p expression in ACC alleviates the depression-like behaviors of mice exposed to chronic unpredictable mild stress. Our study proposed an innovative diagnostic model of MDD by combining the plasma exosome-derived miR-151a-3p expression with its associated multimodal MRI patterns, potentially serving as a novel diagnostic tool.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the most common mental disorder worldwide, characterized by persistent sadness and a lack of interest, frequently accompanied by cognitive and somatic symptoms. It is estimated that about 5% of adults worldwide suffer from MDD, which severely affects individuals, families and society and results in a significant economic burden [1,2,3]. However, limited by the lack of etiology and biomarkers, current classifications, such as the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10), are generated in a top-down manner [4, 5]. Consequently, interviews and scale assessments are still commonly used as key means of recognizing MDD. Yet, this approach is susceptible to subjectivity and recall bias, making it less diagnostically valid and stable [6]. In particular, the MDD taxonomy shows minimal agreement among psychiatrists [7], which severely limits early identification of MDD and subsequent standardization and precision of treatment.

Current diagnostic criteria for MDD based on DSM-5 and ICD-10 classifications are much less reliable due to the limited application of deductive reasoning [4]. Consequently, pan-omics and precision psychiatry suggest the use of data-driven bottom-up approaches to compute biosignatures consisting of molecular pathways, networks, symptoms and environmental features [8], thus linking causal factors, protective elements, adverse output pathways (AOPs, i.e., biological, molecular, pan-omics and brain-imaging signatures) and phenome (cognitome, symptomatome and phenomenome) feature sets, ultimately striving to achieve the ‘reification of clinical diagnosis’ goal [4]. In recent years, benefiting from the continuous advances in multimodal neuroimaging techniques and sophisticated analytical methods, there are even stronger expectations for the realization of this objective [9]. For example, emerging evidence suggests that depressive symptoms may be associated with disruptions in abnormal functional network connectivity within multiple sub-networks of the brain, and modulating the functional connectivity of these aberrant sub-networks through different interventions may ameliorate the corresponding symptoms [9]. Li et al. observed a widespread reduction in cortical thickness among MDD patients, particularly in the anterior dorsolateral frontal cortex, lateral temporal cortex and parietal regions, which were associated with elevated structural covariances, functional synchronization, gene co-expression and chemical-structural covariances [10]. Structural and functional neuroimaging studies have revealed various alterations in brain regions involved in basic sensory processing, like visual cortex, as well as higher-order cognitive functions including the medial prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, temporal cortex, amygdala, insula and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) within MDD patients [11, 12]. However, diametrically opposed findings have emerged, with some resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI)-based studies identifying hyperconnectivity of the default mode network (DMN) in depressed individuals [13, 14], whereas other studies reported hypoconnectivity of the DMN [15]. Accordingly, genetic, environmental, and clinical heterogeneity of MDD samples and variability in analytical methods may lead to fluctuating reliability of MRI outcomes, resulting in their unconvincing translation into clinical practice [16]. Therefore, it is necessary to combine MRI with other clinical data (e.g., pan-omics) to construct a methodology based on a bottom-up approach that includes both vertical and horizontal interpretations [9].

The exploration of valuable biomarkers that can serve as diagnosis or differential diagnosis of MDD may require the application of multimodal and interdisciplinary approaches, including structural and functional MRI (sMRI and fMRI), genome sequencing and other advanced technologies to explore cellular molecular mechanisms, neuroinflammatory pathways, etc [17]. MicroRNAs (miRNAs), particularly crucial epigenetic regulatory factors, play a role in modulating the post-transcriptional expression of more than 60% of genes [18], affecting almost all cellular processes [19]. Extensive researches have substantiated the differential expression of some miRNAs in MDD [20]. Currently, a number of candidate miRNAs with differential expressions have been screened in brain tissues of MDD patients or animal models of depression, with mounting evidence supporting their potential as diagnostic indicators [21]. Notably, investigations on postmortem human samples have unveiled atypical miRNA expression in critical brain regions like the prefrontal cortex, amygdala and ACC in MDD individuals compared to healthy subjects [21, 22]. Overexpressing miR-323-3p in the ACC using adenoviruses led to depression-like behaviors in mice, which were mitigated upon downregulation of the miR-323-3p [21]. Moreover, previous studies have identified elevated levels of miR-144-3p and miR-451a in the plasma of MDD patients compared to healthy controls (HCs), with implications linked to the underlying mechanisms of ketamine [23, 24]. These studies hold great promise for identifying miRNAs as biomarkers associated with MDD, but the constraints of invading target brain tissue, or the isolation effect of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), result in peripheral blood miRNAs not convincingly representing the brain microenvironment, thereby compromising their causal validity.

Brain-derived exosomes, small vesicles released by various cell types including neurons and glial cells, solve above dilemmas well. That’s because exosomes are free to cross the BBB and readily detected in biofluids such as plasma, saliva and urine through circulation [25, 26], making it easy to obtain brain-derived exosomes through peripheral sampling in a representative manner [27]. MiRNAs are enriched in exosomes and their expression can be influenced by pathological changes in MDD [28, 29]. For instance, microglia-derived exosomal miR-146a-5p is exported to neurons [29], binding to KLF4 to inhibit CDKL5 expression, thereby inhibiting the formation of new granule neurons and ultimately inducing depression-like behaviors [30]. These properties render the exosomes and their cargoes, particularly miRNAs, as promising biomarkers for MDD. However, limited research data suggest that differential expression of exosomal miRNAs is not unique to MDD, and they are also present in a number of central nervous system (CNS) and psychiatric disorders that genetically overlap with MDD, including anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, etc. [31], limiting their specificity as biomarkers of MDD in the clinical setting. To address this issue, combining candidate miRNAs with specific multimodal brain imaging data as a diagnostic biomarker for MDD holds promise as an effective strategy to enhance confidence and validity [32]. As found in recent studies, the expression level of exosomal miR-134 affects the clinical manifestations of MDD by regulating ACC-related functional dysconnectivity [33].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the pioneering endeavor to estimate biomarkers for the diagnosis of MDD and explore molecular mechanisms by jointly mining characteristic multimodal MRI data guided by differentially expressed exosome-derived miRNAs in peripheral blood. To test this hypothesis, we first identified a candidate plasma exosome-derived miRNA based on cross-sectional data from our case-control study (plasma exosome-derived miR-151a-3p levels were significantly lower in MDD patients than in HCs). Subsequently, we used a multimodal MRI fusion algorithm known as ‘Multisite canonical correlation analysis with reference plus joint independent component analysis (MCCAR+jICA)’ to analyze how the abnormally altered expression levels of miR-151a-3p derived from plasma exosomes affected the covariation of multimodal brain imaging data [34]. Further, we collected peripheral blood and MRI data from MDD patients after treatment of six months to perform a follow-up validation of the target biomarkers using longitudinal data from our depression-specific cohort study, and the signaling pathways were initially explored in model animals.

Materials and methods

Human studies

Human samples

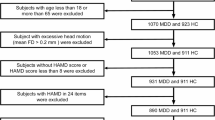

In this study, 115 unmedicated patients with MDD and 114 HCs matched for age and gender were recruited from Department of Psychology at Qilu Hospital of Shandong University between June 2022 and June 2023. Supplementary Fig. 1 illustrates the initial number of participants and those excluded for various reasons. All participants underwent clinical interviews with two certified psychiatrists and fulfilled the detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in Supplementary Table 1. All procedures of this study have been approved by the Ethical Committee of School of Basic Medical Sciences, Shandong University (No. ECSBMSSDU2022-1-61) and registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2200060261). All subjects voluntarily enrolled in the study and provided written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The assessors were blinded to the experimental groups in all outcome measures, including molecular assays.

All multimodal MR scans, encompassing diffusion MRI (dMRI), rs-fMRI and sMRI, were performed using a 3.0 T MR scanner (Discovery MR750W, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) at Qilu Hospital of Shandong University. The detailed imaging parameters and preprocessing procedures are presented in the Supplementary Material.

Plasma-derived exosome isolation, total RNA extraction and miRNA sequencing

Each subject provided a 5 ml whole blood sample, from which 2 ml of plasma was extracted. Then exosomes were isolated from the plasma using the extraction and purification reagent kit (UR52151, Umibio, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The morphologies of exosomes were observed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with a HITACHI HT-7800 instrument. Particle size distribution of exosomes was assessed using Nano flow cytometry (NanoFCM) (Flow NanoAnalyzer). Meanwhile, the presence of specific exosomal surface markers such as CD9 (BioLegend, 555371), CD63 (BioLegend, 556019) and CD81 (BioLegend, 551108) was determined, using the NanoFCM. Next, total RNAs, including miRNA, were isolated from exosomes using the TRIzol reagent (Catalog No. 15596018, Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocols. In summary, 1 mL of TRIzol reagent was added to dissolve exosomes and release RNA. Then, chloroform was added to create a mixture through centrifugation, resulting in the separation of the aqueous phase (containing RNA), the interphase (containing protein and DNA) and the organic phase. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new centrifugal tube, and isopropanol was added to precipitate the RNA. Subsequently, RNA was purified through ethanol washing to remove contaminants. Finally, total RNA from every individual was utilized for the following miRNA library construction and sequencing, performed by the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) (Shenzhen, China). Differentially expressed miRNAs (DEmiRs) between 5 MDD patients and 4 HCs were identified using DEseq2 on the Dr. Tom network platform of BGI (https://biosys.bgi.com) with filtering criteria: |log2 fold change (FC)| > 2 and Qvalue < 0.001. Additionally, 70 MDD individuals and 71 HCs voluntarily contributed venous blood for a subsequent real-time quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) test to measure and validate the expression levels of DEmiRs based on prior bioinformatics analysis. Demographic data for these 141 samples were depicted in Supplementary Table 2. The detailed operational steps for qRT-PCR were described in the Supplementary Material.

Multimodal MRI feature fusion with reference

Four representative MRI features, structural connectivity strength (SCS) from dMRI, functional connectivity strength (FCS) from rs-fMRI, fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (fALFF) from rs-fMRI and grey matter volume (GMV) from sMRI, were jointly analyzed using the ‘MCCAR+jICA’ algorithm. Based on the miRNA sequencing and qRT-PCR results from the previous section, the expression levels of plasma exosome-derived miR-151a-3p served as the reference to guide the fusion of multimodal data. ‘MCCAR + jICA’ is a supervised fusion model which maximizes correlations between different MRI features. Moreover, it accurately identifies covarying multimodal components most strongly associated with the reference information, specifically the expression levels of miR-151a-3p [34]. Our objective was to identify a reference guided joint independent component (ICref) from multiple components that are significantly correlated with the expression levels of miR-151a-3p. This component should exhibit covariation across SCS, FCS, fALFF and GMV features, showing significant inter-group differences and the ability to distinguish between the MDD and HC groups. Statistical tests involved two-sample t-tests to compare mixing coefficients of each component for every MRI feature. Multiple comparison correction was performed using the false discovery rate (FDR) method. The detailed calculation of MRI metrics and fusion procedures (Supplementary Fig. 2) are presented in the Supplementary Material.

Support vector machine for classification

Based on the ‘MCCAR + jICA’ algorithm employed in the previous section, the miR-151a-3p-associated multimodal components were identified and exhibited significant differences between the MDD and HC groups. Subsequently, we categorized these multimodal components into positive (Z > 0) and negative (Z < 0) feature masks and clustered these masks. Several clusters were obtained for each modality and then used as regions of interest (ROIs) to extract features from each participant. Mean values of multimodal indicators within each ROI, along with the age and gender information for each participant, were computed, resulting in a feature matrix with dimensions Nsubj×M(roi+2). Here, multimodal MRI data from 70 MDD patients and 71 HCs, concurrently available for blood data, were used as the training set. While the remaining 45 MDD patients and 43 HCs were allocated to the testing set. Demographic data for the latter dataset is available in Supplementary Table 3. Therefore, the dimension of this feature matrix is 229 × M(roi+2). The 229 × M(roi+2) miR-151a-3p-associated brain features were input into the support vector machine (SVM) model utilizing a radial basis kernel to predict the diagnostic status of individuals (either MDD patients or HCs). To find the optimal hyper-parameters during the training process, a 10-fold cross validation strategy with grid search was used, which was repeated 5 times to get a robust estimate. The hyper-parameters (i.e., C and gamma) were chosen from 10−5 to 105 times the default values. The e1071 (v1.7-8) package in the R environment was used for SVM modeling. For individual-level classification, we defined a multimodal feature abnormalities (MFA) score measuring the deviation in an individual’s multimodal features from the HC group. The index was calculated as the distance of each individual from the separating hyperplane using hyperparameters corresponding to the optimal classification results. The inspiration for proposing this new metric primarily stems from the previous study by Li et al [35].

In addition, with the same training and testing data, we employed 170 ROIs from the automated anatomical labelling atlas 3 (AAL3) to extract mean values of multimodal indicators (FCS and fALFF features) within each ROI for each participant [36], and then performed inter-group statistical analysis. Subsequently, K multimodal components showing significant differences between the MDD and HC groups were obtained. Furthermore, we integrated age and gender information for each subject, creating a feature matrix with dimensions of 229 × M(K+2). Similarly, we input this matrix into the SVM model with the same parameters, conducted subject classification and diagnosis, and calculated the MFA score. Lastly, we calculated the area under the curve (AUC), optimal diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity (true positive rate), specificity (true negative rate), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) for the classification results obtained from the two different feature matrices and performed a comparison.

Alterations of miR-151a-3p and multimodal MRI patterns after antidepressant treatment

To determine whether the expression levels of plasma exosomal miR-151a-3p and related fMRI patterns in MDD patients improve following effective treatment, a longitudinal observation of half year was conducted in conjunction with antidepressant therapy. During this period, 28 participants voluntarily participated in the follow-up and received naturalistic treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), including paroxetine and escitalopram. The type of medication was allocated by the psychiatrist according to the patients’ physical condition. Blood, MRI and clinical data were collected from the 28 participants at the end of the six-month treatment period. According to previous research, a reduction exceeding 50% in Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) score was defined as an effective response to treatment [37]. Consequently, 28 participants were categorized into either the treatment-effective or treatment-ineffective groups. Statistical comparisons were separately performed on the expression levels of plasma exosomal miR-151a-3p and related fMRI indicators before and after treatment of six months in patients for each group.

Animal studies

Sixty male C57BL/6J mice (aged 6 weeks, weight 20 ± 2 g) were purchased from the animal center at Shandong University (Jinan, Shandong) for the animal experiments. Detailed housing information for the mice is available in the Supplementary Material.

Experimental design

Among the clusters of ICref that were used for MDD and HC classification and correlated with miR-151a-3p, the ACC emerges as the most homologous region between human and mice [38, 39]. Consequently, our animal experiments primarily focused on the ACC region in mice to validate our earlier observations in human subjects. At the beginning, some of the mice were randomly divided into two groups. The negative control (NC) group (n = 10), in which the mice were raised for 7 days under normal conditions with food and water supply, and then adeno-associated virus (AAV) 9-U6-NC-enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) virus, which is a blank control virus, was injected into the ACC region of the mice. The miR-151-3p knock-down (KD) group (n = 10), in which the mice were also raised for 7 days under normal conditions, and then AAV9-U6-miR-151-3p-sponge-eGFP virus was injected into the ACC region of the mice, significantly reducing the expression levels of miR-151-3p in the ACC. The AAV9-U6-miR-151-3p-sponge-eGFP vector was constructed by WZ Biosciences Inc. (Jinan, China). The sequence of the AAV9-U6-miR-151-3p-sponge-eGFP was GCGATCGCCCTCAAGGAGAGGAGTCTAGGGGTCCCCCTCAAGGAGAGGAGTCTAGGGGTCCCCCTCAAGGAGAGGAGTCTAGGGGTCCCCCTCAAGGAGAGGAGTCTAGACGCGT. The remaining mice were randomly assigned to four groups: chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS)-NC group (n = 10), in which the mice were exposed to CUMS for consecutive 21 days and then injected with AAV9-U6-NC-eGFP in the ACC; CUMS-miR-151a-3p overexpression (OE) group (n = 10), in which the mice were exposed to CUMS for consecutive 21 days and then injected with AAV9-U6-miR-151a-3p-eGFP in the ACC to overexpress hsa-miR-151a-3p; Control-NC group (n = 10), in which the mice were housed under normal conditions during the 21 days and then injected with AAV9-U6-NC-eGFP in the ACC; Control-miR-151a-3p OE group (n = 10), in which the mice were not subjected to any treatment for 21 days, but later underwent viral injection into the ACC to overexpress hsa-miR-151a-3p. The AAV9-U6-miR-151a-3p-eGFP and AAV9-U6-NC-eGFP vectors were constructed by WZ Biosciences Inc. (Jinan, China). The sequence of the AAV9-U6-miR-151a-3p-eGFP was CCTCAAGGAGCTTCAGTCTAGTTCAAGAGACTAGACTGAAGCTCCTTGAGGTTTTTT. While the meaningless sequence of the AAV9-U6-NC-eGFP vector was TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTTCAAGAGAACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAATTTTTT. The overall experimental procedure was illustrated in Fig. 1 and the 21-day CUMS modeling was outlined in Supplementary Table 4. The detailed process of stereotactic surgery was described in the Supplementary Material. Following the completion of above experimental procedures, behavioral tests, including Tail Suspension Test (TST), Forced Swim Test (FST), Open Field Test (OFT) and Sucrose Preference Test (SPT), were conducted on the mice. For a comprehensive understanding of the behavioral tests and subsequent qRT-PCR, please consult the Supplementary Material.

A Extraction of RNA from plasma exosomes and miRNA sequencing analysis. B Collection and process of multimodal MRI data. C Significant multimodal MRI patterns associated with miR-151a-3p expression were identified using the ‘MCCAR+jICA’ algorithm and input into an SVM model to classify individuals into MDD or HC groups. D After regulating the expression of miR-151a-3p in the ACC of mice using AAV, the behavioral changes and alterations in downstream gene expression in mice were investigated. miRNA microRNA, qRT-PCR quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction, MCCAR+jICA multisite canonical correlation analysis with reference plus joint independent component analysis, SVM support vector machine, MDD major depressive disorder, HC healthy control, MFA multimodal feature abnormalities, ACC anterior cingulate cortex, AAV adeno-associated virus, NGS next generation sequencing. The Fig. 1 was created in BioRender. Liang, W. (2025) https://BioRender.com/s0uplic.

RNA sequencing of mouse ACC and analysis

The ACC tissues of mice were extracted for RNA sequencing after completing the behavioral tests. Firstly, total RNAs were isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Catalog No. 15596018, Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocols. Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) was used to assess the quality of the total RNA. Then, a library was constructed using the NEB Next Ultra RNA Kit. The detailed RNA-seq library construction and sequencing work were carried out by CapitalBio Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the CUMS-miR-151a-3p OE group and CUMS-NC group were identified using DEseq2 in the R package (v3.3.1, https://www.r-project.org/) with the filtering criteria, |log2FC | > 1 and Qvalue < 0.05. Subsequent gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis and Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) were performed using the OmicShare tools, a free online platform for data analysis (https://www.omicshare.com/tools).

Statistical analysis

In our analysis, the normality of distributions was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test before further statistical detection, and standard parametric statistics were used to draw statistical inferences only when a Gaussian distribution was confirmed for each dependent variable. The statistical methods employed for MRI data in this study were elaborated in the respective sections. Differences of demographic data, like age, body mass index (BMI), years of education, HAMD, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAMA) between MDD and HC groups were tested using a two-sample t-test. For intergroup differences in gender and other behavioral information, such as self-injury behavior (yes/no), suicidal thoughts (yes/no), suicidal behavior (yes/no) and childhood trauma (yes/no), Chi-square or Chi-square with Yates’ correction statistical methods were employed for testing. A two-sample t-test was employed to examine the expression levels of plasma exosomal miR-151a-3p between the MDD and the HC groups in the qRT-PCR test. A paired t-test was utilized to compare the plasma exosomal miR-151a-3p expression levels between post-treatment and baseline levels in MDD patients. Similarly, changes in fMRI metrics of some brain regions associated with the miR-151a-3p expressions before and after treatment were also analyzed using paired t-test. Threshold levels of significance for paired t-test were adjusted for multiple comparisons by Bonferroni–Dunn method.

In relation to the results of animal behavioral tests, the analysis entailed the utilization of two-sample t-test or two-way analysis of variance (2-way ANOVA) coupled with Tukey’s multiple comparison correction. The threshold for statistical significance was set at a P < 0.05. Detailed statistical analyses were conducted by an independent investigator, blinded to the experimental conditions, using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Demographic and clinical data for 115 unmedicated patients with MDD and 114 age- and gender-matched HCs were presented in Table 1, all of whom underwent multimodal MR scans. Among them, 70 MDD patients and 71 HCs underwent venous blood collection simultaneously with MR scans, with participant information available in Supplementary Table 2. There were no significant differences in basic information such as age, gender, and BMI between the MDD and HC groups. Nevertheless, significant intergroup differences were observed in years of education and clinical scales including HAMD, HAMA, BDI and others.

Expression levels of miR-151a-3p in the plasma exosomes of MDD patients were decreased

MiRNAs can be released from neurons into the extracellular environment, and can be further disseminated into the humoral circulation through binding with RNA-binding proteins or transportation via exosomes and microvesicles [40]. MiRNAs are very stable and easy to detect in peripheral blood, even after repeated freezing and thawing of the sample, making them a candidate for an ideal biomarker [41]. We firstly extracted exosomes from the plasma and conducted identification of the morphology, size distribution and specific protein markers of exosomes. TEM results showed that exosomes had a relatively intact spherical morphology with double-membrane structures (Fig. 2A), consistent with previous studies. NanoFCM measurements indicated that the diameter of these particles ranged from 30 to 150 nm (Fig. 2B), similar to previous findings on exosome size distribution. Furthermore, the presence of exosomal marker proteins, CD9, CD63, and CD81, were confirmed using NanoFCM technology (Fig. 2C). All these characteristics supported that the extracted particles were indeed exosomes. Then, miRNA sequencing was employed to analyze the differential expression of miRNAs in plasma exosomes between MDD and HC groups. The results revealed five DEmiRs, comprising four upregulated and one downregulated miRNAs, meeting the criteria of |log2FC | > 2 and Qvalue < 0.001 (Fig. 2D). Notably, miR-151a-3p consistently exhibited lower expressions in MDD sequencing samples and higher expressions in HC sequencing samples compared to the other four DEmiRs (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, subsequent qRT-PCR experiments were conducted to compare the relative expression levels of miR-151a-3p in plasma exosomes between 70 MDD patients and 71 HCs confirming this finding (Fig. 2F). Accordingly, the differentially expressed plasma exosome-derived miR-151a-3p was identified as a candidate miRNA for MDD.

A Representative transmission electron microscopy images of human plasma-derived exosomes. B Representative particle size diagram of exosomes derived from human plasma. C Representative protein (CD9, CD63 and CD81) fluorescence detection diagrams using nanoscale flow cytometry in human plasma-derived exosomes. D Four upregulated and one downregulated miRNAs with the criteria of |log2FC | > 2 and Qvalue < 0.001 between MDD and HC groups. E In sequencing samples, miR-151a-3p exhibited consistently lower expressions in MDD subjects and higher expressions in healthy subjects compared to other differential miRNAs. F The expression level of miR-151a-3p in plasma-derived exosomes of MDD patients was significantly lower than that in healthy subjects in the results of qRT-PCR. MDD, n = 70; HC, n = 71. miRNAs microRNAs, FC fold change, MDD major depressive disorder, HC healthy control, qRT-PCR quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction.

Covarying multimodal imaging patterns associated with miR-151a-3p expressions

A reference guided joint independent component, ICref, was identified through multimodal fusion. Spatial maps were transformed into Z scores in the Fig. 3A–D. ICref exhibited correlations with miR-151a-3p expression levels (r = 0.2222**, −0.1992*, −0.1843* (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, FDR-corrected for multiple comparisons)) for FCS, fALFF and SCS, respectively. Notably, significant inter-group differences were observed exclusively in the fMRI metrics (****P < 0.0001, **P = 0.0055, P = 0.6549 and P = 0.3895 for FCS, fALFF, SCS and GMV, respectively) (see Fig. 3E–H for details). The mean loading parameters were adjusted as HC subjects > MDD participants for FCS, meaning that the positive Z-values (red brain regions) represent areas where FCS values of HC group were higher than those of MDD group. In contrast, negative Z-values (blue brain regions) indicate areas where the FCS values of the MDD group were higher than those of the HC group (Fig. 3A). While for fALFF metric, the mean loading parameters were adjusted as MDD subjects > HC participants. This implies that red brain regions indicate areas where the fALFF values of the MDD group were higher than those of the HC group, while blue brain regions correspond to areas where the fALFF values of the HC group were higher than those of the MDD group (Fig. 3B). The positive correlation between the expression levels of miR-151a-3p and FCS_ICref loadings was illustrated in Fig. 3E, with lower levels of miR-151a-3p in the MDD group corresponding to lower loadings. On the contrary, a significant negative correlation existed between the expression levels of miR-151a-3p and the loadings of fALFF_ICref and SCS_ICref (Fig. 3F, G), with lower levels of miR-151a-3p in the MDD group corresponding to higher loadings.

A The spatial maps for FCS metric, where red brain regions in the spatial maps indicate higher FCS values in HC subjects than MDD participants, and the blue brain regions indicate higher FCS values in MDD subjects than HC participants. B The spatial maps for fALFF metric, where the red brain regions mean MDD > HC subjects and the blue brain regions mean HC > MDD subjects. C, D The spatial maps for SCS and GMV metrics. There were no statistically significant inter-group differences for the SCS and GMV metrics. E The loadings of FCS_ICref that were adjusted as HC subjects > MDD. Besides, loadings of FCS_ICref and miR-151a-3p levels were positively correlated. Thus, MDD correspond to lower miR-151a-3p expression levels and lower loading weights of FCS_ICref compared to HC subjects. F The loadings of fALFF_ICref that were adjusted as MDD subjects > HC. Besides, loadings of fALFF_ICref and miR-151a-3p levels were negatively correlated. Thus, MDD correspond to lower miR-151a-3p expression levels and higher loading weights of fALFF_ICref compared to HC subjects. G, H There were no significant group differences in SCS and GMV metrics. The expression levels of miR-151a-3p were significantly negatively correlated with the loadings of SCS_ICref, while no correlation was observed for the GMV_ICref. FCS functional connectivity strength, fALFF fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations, SCS structural connectivity strength, GMV grey matter volume, ICref reference guided joint independent component, MDD major depressive disorder, HC healthy control, MCCAR+jICA Multisite canonical correlation analysis with reference plus joint independent component analysis.

Overall, lower miR-151a-3p levels in MDD were associated with reduced FCS and increased fALFF in the visual cortex. In contrast, higher FCS and lower fALFF were observed in the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), precuneus, inferior parietal lobule (IPL) and other regions, which mainly belong to the DMN. while ACC, a key node of salience network (SN), should be divided into three distinct regions, supracallosal ACC, pregenual ACC and subgenual ACC for separate observations. Decreased miR-151a-3p levels were linked with increased FCS in the supracallosal ACC of MDD patients (Supplementary Fig. 3). Notably, lower miR-151a-3p levels were associated with decreased fALFF values in the pregenual ACC, but increased fALFF in the subgenual and supracallosal ACC regions of MDD subjects (Supplementary Fig. 4). In terms of structural metrics, although inter-group differences in SCS did not reach statistical significance, the statistical values for the correlation with miR-151a-3p remained significant (Fig. 3G). The miR-151a-3p expression levels were associated with the SCS values in the supracallosal ACC. In addition, SCS values in brain regions such as the MPFC, cuneus, precuneus and insula were also associated with the miR-151a-3p expressions (Fig. 3C, Supplementary Fig. 5). However, there were no statistically significant correlations or inter-group differences for the GMV metric (Fig. 3D, H).

The multi-modal MRI features related to miR-151a-3p generated better classification between MDD and HC groups

Features (FCS and fALFF) associated with miR-151a-3p expressions were categorized into positive and negative networks according to the Z-scored brain maps. Subsequently, we computed the mean values of each feature within the positive and negative networks, resulting in a total of four features associated with miR-151a-3p expressions (Fig. 4A). Two-sample t-tests showed significant group differences between MDD and HC for all four features (Fig. 4B, C), except for the ‘fALFF_neg’ feature in the test dataset, where intergroup differences did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4C). Then, the positive and negative components of each feature underwent separate cluster analyses, with each cluster serving as a mask. These masks were combined with the whole-brain feature maps to obtain the average feature values within the mask regions. Ultimately, each participant obtained 32 feature masks, augmented with age and gender information, constituting a feature matrix with dimensions of 229×34. This matrix served as input for an SVM model to classify MDD patients and HCs. Furthermore, using hyperparameters of SVM based on the optimal classification results, we calculated the distance of each individual to the separating hyperplane, yielding the MFA score for each participant of testing set. If this score exceeded 0, the individual was classified as an MDD patient. Conversely, when the MFA score falls below 0, the individual was categorized as HC. From the Fig. 4D, it is evident that the majority of individuals were clearly classified correctly. Moreover, this score exhibited a significant positive correlation with psychological scales, including HAMD and BDI. Finally, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the classification results between MDD and HC on the testing set was also plotted. The optimal diagnostic accuracy of the test dataset reached 92.05%. The area under the curve was 0.96 (95% confidence interval: 0.92–0.99), and the specificity, sensitivity, PPV and NPV values were 0.86, 0.98, 0.88 and 0.97, respectively (Fig. 4D).

A Four multimodal MRI features associated with miR-151a-3p expressions were identified. B Group differences in miR-151a-3p-associated positive and negative patterns between MDD and HC groups were assessed using independent training dataset (MDD: n = 70; HC: n = 71). A two-tailed two-sample t-test was used for statistical analysis and the results were as follows: ***P = 0.0005, *P = 0.0441, **P = 0.0047, ****P < 0.0001. C Group differences in miR-151a-3p-associated positive and negative patterns between MDD and HC groups were assessed using independent test dataset (MDD: n = 45; HC: n = 43). A two-tailed two-sample t-test was used for statistical analysis and the results were as follows: P = 0.1382, **P = 0.0049, ****P < 0.0001. D When MFA score was more than 0, the individual was considered as an MDD patient. Conversely, a subject was classified as HC when the MFA score falls below 0. From the bar chart, it is evident that the majority of individuals were clearly classified correctly. This MFA score exhibited a significant positive correlation with psychological scales, including HAMD and BDI. ROC curves depicting the classification results between MDD and HC groups revealed that the area under the curve was 0.96 and the accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, PPV and NPV values were 0.92, 0.86, 0.98, 0.88 and 0.97, respectively, ****P < 0.0001. fALFF_neg fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations negative features, fALFF_pos fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuations positive features, FCS_neg functional connectivity strength negative features, FCS_pos functional connectivity strength positive features, MDD major depressive disorder, HC healthy control, MFA multimodal feature abnormalities, HAMD Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, BDI Beck Depression Inventory, ACC accuracy, AUC area under the curve, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value, ROC receiver operating characteristic.

On the other hand, employing the AAL3 atlas, we extracted mean values of multimodal indicators (FCS and fALFF features) within each ROI for participants from the same training and test datasets. Subsequently, through inter-group statistical analysis and neglecting the correlations with the expression of miR-151a-3p, 75 multimodal feature ROIs were identified that exhibited significant differences between the MDD and HC groups. By incorporating gender as well as age information for each participant, we ultimately input a feature matrix with dimensions of 229 × 77 into the SVM model with consistent parameters, leading to different classification outcomes. The optimal diagnostic accuracy of the test dataset reached 70.45%. Then, we generated an ROC curve for the classification results between MDD and HC on the test set, which exhibited an area under the curve of 0.83 (95% confidence interval: 0.74–0.92). The specificity, sensitivity, PPV, and NPV values were 0.88, 0.53, 0.83 and 0.64, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6A). It is evident that inputting the multimodal feature matrix with dimensions of 229 × 34 related to the expression levels of miR-151a-3p produced a better classification result in the same SVM model. Nevertheless, we also computed the MFA score for this feature matrix with dimensions of 229 × 77, considering an individual as an MDD patient if this score exceeded 0 (Supplementary Fig. 6B). This score also exhibited a significant positive correlation with psychological scales, such as HAMD and BDI (Supplementary Fig. 6C, D).

Alterations of miR-151a-3p and multimodal MRI indicators after antidepressant treatment

Out of the 115 MDD participants, 28 (24.3%) patients consistently took antidepressant medication and attended regular follow-up visits at the hospital. Among these, only 10 patients met the criteria for having an effective response to drug treatment (a reduction of 50% in HAMD score compared to baseline). A significant difference in HAMD scores was observed before and after treatment in the treatment-effective group of 10 individuals (Supplementary Fig. 7A). Conversely, the ineffective treatment group of 18 patients showed no statistical difference in HAMD scores between pre-treatment and post-treatment (Supplementary Fig. 7B). Similarly, the plasma exosomal miR-151a-3p expressions of MDD patients in the treatment-effective group increased after treatment of six months (Supplementary Fig. 7C). While the miR-151a-3p expression levels of subjects in the treatment-ineffective group did not exhibit statistically significant changes compared to baseline (Supplementary Fig. 7D).

We further conducted statistical comparisons of fMRI indicators (fALFF and FCS) in the ACC subdivisions (supracallosal ACC, pregenual ACC and subgenual ACC), DMN regions (MPFC, PCC, precuneus, IPL, etc.) and selected visual areas before and after treatment in both groups. As shown in the Fig. 5, the fALFF values of left supracallosal ACC and right middle occipital gyrus decreased compared with the baseline. However, some DMN regions such as left PCC and bilateral precuneus, the post-treatment fALFF values were higher than pre-treatment levels. In addition, the FCS values of some DMN regions, like bilateral supramarginal gyrus, were lower than the baseline levels. The FCS values in areas such as left calcarine and bilateral lingual gyrus increased after treatment. No corresponding changes were found in the treatment-ineffective group after Bonferroni’s correction (Supplementary Fig. 8).

A The fALFF values of post-treatment in left supracallosal ACC were lower than baseline measurement, ***P = 0.0004. B–D In the left posterior cingulate cortex and bilateral precuneus, the fALFF values of post-treatment were higher than those of pre-treatment, ****P < 0.0001. E The fALFF values of post-treatment in right middle occipital gyrus decreased compared with the baseline, ****P < 0.0001. F, G The FCS values of post-treatment in bilateral supramarginal gyrus were lower than the baseline levels, ****P < 0.0001, **P = 0.0014. H–J The FCS values of post-treatment in the left calcarine and bilateral lingual gyrus increased compared with pre-treatment, ****P < 0.0001. Error bars denote t values. ACC_sup_L left supracallosal anterior cingulate cortex, Cingulate_Post_L left posterior cingulate cortex, Occipital_Mid_R right middle occipital gyrus, SupraMarginal_L left supramarginal gyrus, SupraMarginal_R right supramarginal gyrus.

Behavioral effects of knockdown of miR-151-3p and overexpression of hsa-miR-151a-3p in mouse ACC

To investigate the causal relationship between the abnormal expression of miR-151a-3p and the occurrence of MDD, we respectively reduced miR-151-3p and overexpressed hsa-miR-151a-3p in the ACC of mice. AAV9-U6-miR-151-3p-sponge-eGFP was used to reduce the expressions of miR-151-3p in the ACC of mice. Another blank control vector was constructed as a negative control. As shown in the Supplementary Fig. 9A, the mice will be normally housed for 7 days. Subsequently, a series of behavioral tests were conducted on the mice to detect their depression-like behaviors after bilateral stereotaxic infusion into the ACC for 21 days. Then, qRT-PCR results demonstrated that the viruses significantly reduced the expression of miR-151-3p in the ACC of mice (****P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Fig. 9B). The results of behavioral tests also confirmed that knocking down the expression of miR-151-3p in the ACC of mice can induce depression-like behaviors. In the TST and FST experiments, the immobility time of mice in the miR-151-3p KD group was significantly higher than that of the mice in NC group (*P = 0.017 for TST; *P = 0.0182 for FST) (Supplementary Fig. 9C, D). In the SPT experiment, compared with the mice in the NC group, the sucrose preference rate of the miR-151-3p KD group was significantly lower (*P = 0.0201) (Supplementary Fig. 9E). The results of OFT experiment showed that there were no statistically significant differences in the movement distance and average movement speed between the two groups of mice (Supplementary Fig. 9F, G), indicating that injecting the virus into the ACC of mice to reduce the expression of miR-151-3p did not affect the motor ability of mice. However, the time that the mice of miR-151-3p KD group spent in the central area of the open field was significantly lower than that of the NC group (*P = 0.0156) (Supplementary Fig. 9H).

On the contrary, the AAV9-U6-miR-151a-3p-eGFP was constructed to upregulate the expressions of hsa-miR-151a-3p in the ACC of mice. As shown in the Fig. 6A, B, behavioral tests were also conducted after the virus injection into the bilateral ACC for 21 days. The results of qRT-PCR showed that the expression levels of hsa-miR-151a-3p in the ACC of CUMS-miR-151a-3p OE group and Control-miR-151a-3p OE group were significantly increased (**P = 0.0069, *P = 0.0344; Fig. 6C). In the TST experiment, mice with elevated hsa-miR-151a-3p levels of ACC in the CUMS-miR-151a-3p OE group exhibited significantly reduced immobility time compared to the mice of CUMS-NC group (*P = 0.0212; Fig. 6D). Similarly, in the FST experiment, mice in the CUMS-miR-151a-3p OE group displayed significantly lower immobility time compared to mice in the CUMS-NC group (*P = 0.0246; Fig. 6E). In the SPT experiment, upregulation of hsa-miR-151a-3p significantly increased the sugar intake in the CUMS-miR-151a-3p OE group compared to the CUMS-NC group (*P = 0.0241; Fig. 6F). In the OFT experiment, we measured the locomotor activity of mice to examine whether there were intergroup differences resulting from a decrease in nonspecific motor activity. The results indicated that there were no differences in movement distance and average movement speed among the four groups (Fig. 6G, H), suggesting that CUMS exposure and hsa-miR-151a-3p expression did not affect the motor abilities of the mice. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the time spent in the central zone of the open field area between two CUMS groups (Fig. 6I).

A Procedure of stereotactic surgery and behavioral tests. B eGFP staining of ACC cells infected by AAVs. C Validation of hsa-miR-151a-3p expression in the ACC of mice. Only mice receiving the hsa-miR-151a-3p viruses injection expressed it. D In CUMS mice, the overexpression of hsa-miR-151a-3p in the ACC reduced the percentage of immobility time during the TST. E In CUMS mice, the overexpression of hsa-miR-151a-3p in the ACC reduced the percentage of immobility time during the FST. F In CUMS mice, the overexpression of hsa-miR-151a-3p in the ACC increased the percentage of sucrose preference in the SPT. G There was no difference in total movement distance traveled by mice among the four groups in the OFT. H There was no difference in average movement speed traveled by mice among the four groups in the OFT. I There was no difference in the time spent by mice in the central zone between the two CUMS groups during the OFT. The data represent the mean ± SD. ns not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ACC anterior cingulate cortex, AAVs adeno-associated viruses, eGFP enhanced green fluorescent protein, NC negative control, CUMS chronic unpredictable mild stress, OE overexpression, TST tail suspension test, FST forced swim test, SPT sucrose preference test, OFT open field test. The Fig. 6A was created in BioRender. Liang, W. (2025) https://BioRender.com/kteazpl.

Overexpressing miR-151a-3p in the mouse ACC may alleviate depression-like behaviors by upregulating genes in the negative regulation of MAPK pathway

After injecting the AAVs in the ACC of mice and completing behavioral experiments, we extracted the ACC tissue and conducted mRNA sequencing to further explore the potential mechanism of improving the depression-like behaviors of CUMS-exposed mice by increasing the expression level of miR-151a-3p in ACC. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 10, we compared the DEGs of Control-miR-151a-3p OE group and Control-NC group (Supplementary Fig. 10A), as well as CUMS-miR-151a-3p OE group and CUMS-NC group (Supplementary Fig. 10B) respectively, and found that there were 83 overlapping DEGs between them (Supplementary Fig. 10C). After removing these 83 intersection genes, there were 255 DEGs between the CUMS-miR-151a-3p OE group and CUMS-NC group (Supplementary Fig. 10D). We conducted subsequent GO enrichment analysis, KEGG enrichment analysis on these 255 genes, and the results of GO indicate that these DEGs are primarily involved in synapse, neuron projection, and neuron part (Supplementary Fig. 10E), regulating biological processes such as synaptic transmission and trans-synaptic signaling (Supplementary Fig. 10F). Additionally, at the molecular level, these DEGs play crucial biological functions in protein binding, receptor binding, and so on (Supplementary Fig. 10G). The KEGG pathway predominantly identified some inflammatory pathways, like cAMP signaling pathway, Axon guidance, MAPK signaling pathway, TGF-beta signaling pathway, Oxytocin signaling pathway and mTOR signaling pathway (Supplementary Fig. 10H). It is noteworthy that the results of GSEA revealed the enrichment of genes in the ‘Negative regulation of MAPK pathway’ with a normalized enrichment score (ES) greater than 0 (Supplementary Fig. 10I). This suggests that in CUMS-miR-151a-3p OE group, when the expression level of hsa-miR-151a-3p in the ACC was elevated, the downstream genes, specifically those associated with the ‘Negative regulation of MAPK pathway’, were upregulated. This upregulation leads to the inhibition of MAPK pathway activity, resulting in the suppression of related inflammatory responses and, consequently, the alleviation of depression-like behaviors.

Discussion

In this study, we conducted a joint analysis of miR-151a-3p, which exhibits abnormally low expression in plasma exosomes of individuals with MDD, and human multimodal MRI data. We identified a set of multimodal neuroimaging patterns associated with the expression levels of miR-151a-3p in plasma exosomes and used them as features input into an SVM model, which could effectively classify individuals into the MDD and HC groups with high accuracy of 92.05%. However, when we neglected the correlations with the miR-151a-3p expression and input only the multimodal MRI features with inter-group differences, the diagnostic rate was only 70.45%. Further, we found upregulated expression of plasma exosomal miR-151a-3p levels and changes in fMRI indices in patients with significant improvement in depressive symptoms (more than 50% reduction in HAMD score) after 6 months of SSRI medication. Animal studies also showed that reducing the expression of miR-151-3p in target brain region (ACC) induces depression-like behaviors in mice, while increasing the hsa-miR-151a-3p expression in the ACC significantly improved depression-like behaviors in mouse models. Accordingly, our study proposed an innovative diagnostic model of MDD by combining the exosome-derived miR-151a-3p expression with its associated multimodal MRI patterns, potentially serving as a novel diagnostic tool.

To date, a few reports imply a direct link between miR-151a-3p and MDD [42, 43]. For example, a pilot study recruiting five patients with MDD indicated that plasma miR-151a-3p was downregulated in depressed patients following a 12-week escitalopram treatment [44]. Additionally, a genome-wide expression analysis of human lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) from healthy adult donors revealed a 6.7-fold higher basal expression of miR-151-3p in paroxetine-sensitive LCLs [43], and miR-151a-3p increases the sensitivity of LCL cells to the antidepressant paroxetine by down-regulating CHL1 expression [45]. MiR-151a-3p is widely expressed in various tissues and can affect neuronal function by influencing cell cycle and inflammatory pathways. For example, microglia-derived exosomal miR-151-3p has been found to attenuate neuronal apoptosis by regulating the p53 pathway and has been associated with altered cognitive function [46, 47]. However, aforementioned prior studies have suggested that the potential use of miR-151a-3p as an MDD biomarker is constrained by several limitations. Firstly, the expression of miR-151a-3p in cells is hindered by difficulties in obtaining clinical samples, limiting its application. While miR-151a-3p derived from plasma or serum is not convincingly indicative of the CNS microenvironment. To get out of this dilemma, we utilized plasma exosomes. Previous studies have shown that exosome-derived miRNAs in biofluids are more stable than free miRNAs in the circulation [48]. Secondly, the small sample size in some studies may introduce significant bias into the results. Thirdly, the reliance on cross-sectional data in many studies restricts the ability to draw causal inferences. Finally, the lack of specificity is evident as abnormal miR-151a-3p expression is also observed in other CNS and neuropsychiatric disorders with genetic overlaps with MDD, including anxiety disorders, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [49, 50]. To address our primary hypothesis, we evaluated miRNAs that can achieve interactive effects with the CNS microenvironment, and the results showed direct evidence of an association between differentially expressed exosome-derived miR-151a-3p and MDD. Specifically, miR-151a-3p was significantly down-regulated in plasma exosomes of MDD patients compared with HCs, and the changes were reversed after remission of depressive symptoms with SSRIs treatment of six months.

In this study, we found correlations between the expression levels of miR-151a-3p in human plasma exosomes and the FCS, fALFF and SCS values in multiple brain regions. In particular, decreased miR-151a-3p of plasma exosome in MDD was associated with increased fALFF and decreased FCS values in the visual cortex. While the visual cortex is an undervalued brain region with relatively fewer related studies of MDD, there are also reports supporting our findings. For example, Ries et al. found that the decreased degree centrality (DC) values in MDD patients were concentrated in the occipital cortex (visual cortex) at low frequencies [51]. The increase of fALFF values in the visual cortex was also observed in Qi’s study [32]. The exact role and underlying molecular mechanisms of visual cortex dysfunction in MDD remain uncertain, but it may emerge as a new frontier for diagnosing and treating patients with MDD [52, 53]. Additionally, higher FCS and lower fALFF values in DMN regions, like MPFC, PCC, precuneus, IPL, etc., were likewise correlated with decreased levels of miR-151a-3p in our results. A study by Scalabrini et al. suggests that the increased resting state functional connectivity (rsFC) within the DMN primarily originates from sources outside the DMN [13]. In line with this conclusion, our results suggest that the increased FCS in DMN brain regions may primarily result from enhanced abnormal connections between non-DMN areas and the DMN. Meanwhile, the decrease in fALFF in DMN brain regions merely reflects a reduction in local spontaneous neural activity.

A very interesting finding is that the functional MRI metrics of the three different subregions of the ACC showed different changes in MDD, which may be related to differences in their respective functions [13]. From our results, we observed that lower miR-151a-3p level was associated with both higher FCS and fALFF values in supracallosal ACC, but lower fALFF values in the pregenual ACC. As for the subgenual ACC region, it only exhibited increased fALFF values associated with reduced miR-151a-3p levels in MDD. Previous studies have demonstrated that neurons in supracallosal and subgenual ACC in humans can respond to unpleasant stimuli and may be overactive in depression [54,55,56], which is consistent with our finding of increased fALFF in these two regions at rest in MDD patients compared to the HCs. On the other hand, positively affective (pleasant) stimulation most strongly activated the pregenual ACC [57, 58], which may, to some extent, explain the reduced fALFF values in this region of MDD patients. Besides, the lateral orbitofrontal cortex and inferior frontal gyrus has strong functional connectivity with the supracallosal ACC in MDD [59], supporting the increased FCS values in the supracallosal ACC as observed in our results. Recent animal experiments have also revealed the role of the ACC in empathy and reward devaluation, among other aspects [60, 61]. These experiments confirmed a strong correlation between the ACC and the onset and development of MDD. At present, both of our structural indices, SCS and GMV, showed no statistically significant intergroup differences between the MDD and HC groups. This suggests that the impact of MDD on the brain of the study population we included appears to be primarily related to functional signals and has not significantly affected brain structure, which may be due to the relatively young age and shorter disease duration of the subjects. This also indicates that early diagnosis and intervention for MDD should be considered to prevent irreversible damage to brain structure. Taking into consideration our multimodal joint analysis results, in the process of exploring early neuroimaging biomarkers for MDD, the functional performance of the ACC and its related subregions deserves our particular attention.

Another significant contribution of the current study is the proposal of MFA score, a novel neuroimaging biomarker that is strongly associated with the expression level of miR-151a-3p in human plasma exosomes and can effectively classify MDD and HC. To be a reliable diagnostic biomarker, a specific parameter must have sensitivity and specificity values of at least 60%, with values above 70% being preferable [62]. In this study, the portion of the dataset containing blood data was used as the training set, while the remaining data was used as the testing set. Under strict separation of the training and testing sets, SVM and ROC analysis showed that in the testing set, the accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC values for identifying MDD patients and HCs were 92.05%, 0.98, 0.86, and 0.96, respectively. Therefore, the MFA scores calculated based on the SVM model have potential utility as a neuroimaging biomarker to assist in the diagnosis of MDD. In addition, MFA scores exhibited a strong correlation with HAMD and BDI, suggesting that MFA scores can effectively predict the severity of MDD. On the other hand, in this study, MFA scores were calculated based on multimodal imaging features that were correlated with the expression levels of miR-151a-3p in plasma exosomes. The expression level of miR-151a-3p also serves as a critical basis for classifying MDD patients and HCs. Therefore, MFA scores carry profound molecular biological significance. Prior studies on diagnostic neuroimaging biomarkers for MDD have primarily relied on single imaging data-driven outcomes, often ignoring the benefits of their association with other clinical findings. The etiology of MDD involves biological, psychological, and social factors, yet there is a scarcity of studies that have investigated the combination of these factors within a single study. Exploring interactions between biomarkers and adopting a more holistic perspective on MDD can facilitate further determination of MDD and improve the accuracy of diagnostic models [63], which has also been validated in our study. When we only input multimodal features with intergroup differences, the obtained diagnostic accuracy (70.45%) is much lower than when inputting the multimodal feature matrix related to miR-151a-3p expressions (92.05%). Moreover, the latter, while ensuring higher accuracy, involves a relatively smaller number of features, thus improving the efficiency of classification diagnosis.

To further validate the causal relationship between the abnormal expression of miR-151a-3p and the occurrence of MDD, we elevated the expression of hsa-miR-151a-3p in the ACC of mice using the AAV vector. Then, we observed a significant improvement of depression-like behaviors in CUMS-exposed mice. Next, the results of GSEA showed that the downstream genes of miR-151a-3p, especially those associated with the ‘Negative regulation of MAPK pathway’, were upregulated. This upregulation may inhibit the activity of MAPK pathway, leading to suppressed inflammatory responses and, consequently, the alleviation of depression-like behaviors. However, the efficacy of SSRIs drug treatment for MDD patients in our follow-up cohort is relatively lower compared with the therapeutic efficacy of overexpressing miR-151a-3p in the animal experiment. The latter embodies the advantages of high precision, rapid efficacy and long-lasting effects of gene therapy [64], providing references for the future treatment of MDD.

This study had several limitations. First, the MRI results are derived from a single-center study with a limited sample size, and the follow-up data only present the treatment effects of six months later. Second, due to equipment limitations, MR scans were not conducted on mice in the animal experiments. Next, we will proceed to complete these two aspects of the work.

In conclusion, we first observed a significant reduction in the expression of miR-151a-3p in plasma exosomes of MDD patients, as collected from clinical blood samples. Subsequently, we employed the ‘MCCAR+jICA’ algorithm to extract neuroimaging patterns associated with the miR-151a-3p expressions. Based on this, we defined an individualized metric, the MFA score, which can effectively diagnose MDD with a high accuracy rate of 92.05%. Animal experiments have further confirmed the causal relationship between the abnormal expression of miR-151a-3p and the occurrence of MDD. All above results suggest the potential of identified miR-151a-3p-associated multimodal MR patterns to function as a gene-mediated brain signature specific to MDD.

Data availability

The data and code generated or analysed during the study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

WHO. Depression. 2020. https://www.who.int/health-topics/depression#tab=tab_1.

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:137–50.

Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A, Cornett J, Whiteford H, Saxena S. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394:240–8.

Stoyanov D, Maes MH. How to construct neuroscience-informed psychiatric classification? Towards nomothetic networks psychiatry. World J Psychiatry. 2021;11:1–12.

Stoyanov D. The reification of diagnosis in psychiatry. Neurotox Res. 2020;37:772–4.

Nestler EJ, Barrot M, Dileone RJ, Eisch AJ, Gold SJ, Monteggia LM. Neurobiology of depression. Neuron. 2002;34:13–25.

Regier DA, Kuhl EA, Kupfer DJ. The DSM-5: classification and criteria changes. World Psychiatry. 2013;12:92–8.

Maes M, Nowak G, Caso JR, Leza JC, Song C, Kubera M, et al. Toward omics-based, systems biomedicine, and path and drug discovery methodologies for depression-inflammation research. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:2927–35.

Poirot MG, Ruhe HG, Mutsaerts HMM, Maximov II, Groote IR, Bjørnerud A, et al. Treatment response prediction in major depressive disorder using multimodal MRI and clinical data: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2024;181:223–33.

Li J, Wang R, Mao N, Huang M, Qiu S, Wang J. NeuroImage multimodal and multiscale evidence for network-based cortical thinning in major depressive disorder. Neuroimage. 2023;277:120265.

Xia M, Liu J, Mechelli A, Sun X, Ma Q, Wang X, et al. Connectome gradient dysfunction in major depression and its association with gene expression profiles and treatment outcomes. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:1384–93.

Zhou E, Wang W, Ma S, Xie X, Kang L, Xu S, et al. Prediction of anxious depression using multimodal neuroimaging and machine learning. Neuroimage. 2024;285:120499.

Scalabrini A, Vai B, Poletti S, Benedetti F, Northoff G. All roads lead to the default-mode network — global source of DMN abnormalities in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:2058–69.

Yu M, Linn KA, Shinohara RT, Oathes DJ, Cook PA, Duprat R. Childhood trauma history is linked to abnormal brain connectivity in major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:8582–90.

Yan C, Chen X, Li L, Xavier F, Bai T, Bo Q, et al. Reduced default mode network functional connectivity in patients with recurrent major depressive disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:9078–83.

Chai Y, Sheline YI, Oathes DJ, Balderston NL, Rao H, Yu M. Functional connectomics in depression: insights into therapies. Trends Cogn Sci. 2023;27:814–32.

Todeva-radneva A, Aryutova K, Kandilarova S, Paunova R, Stoyanov D. The translational potential of non-coding RNAs and multimodal MRI Da- ta sets as diagnostic and differential diagnostic biomarkers for mood dis- orders. Curr Top Med Chem. 2021;21:949–63.

Friedman RC, Farh KKH, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105.

Krol J, Loedige I, Filipowicz W. The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:597–610.

Lopez JP, Lim R, Cruceanu C, Crapper L, Fasano C, Labonte B, et al. MiR-1202 is a primate-specific and brain-enriched microRNA involved in major depression and antidepressant treatment. Nat Med. 2014;20:764–8.

Fiori LM, Kos A, Lin R, Théroux JF, Lopez JP, Kühne C, et al. miR-323a regulates ERBB4 and is involved in depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:4191–204.

Roy B, Dunbar M, Agrawal J, Allen L, Dwivedi Y. Amygdala-based altered mirnome and epigenetic contribution of mir-128-3p in conferring susceptibility to depression-like behavior via wnt signaling. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;23:165–77.

Camkurt MA, Acar Ş, Coşkun S, Güneş M, Güneş S, Yılmaz MF, et al. Comparison of plasma MicroRNA levels in drug naive, first episode depressed patients and healthy controls. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;69:67–71.

van der Zee YY, Eijssen LMT, Mews P, Ramakrishnan A, Alvarez K, Lardner CK, et al. Blood miR-144-3p: a novel diagnostic and therapeutic tool for depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:4536–49.

Lakhal S, Wood MJA. Exosome nanotechnology: an emerging paradigm shift in drug delivery: exploitation of exosome nanovesicles for systemic in vivo delivery of RNAi heralds new horizons for drug delivery across biological barriers. BioEssays. 2011;33:737–41.

Li X, Tsibouklis J, Weng T, Zhang B, Yin G, Feng G, et al. Nano carriers for drug transport across the blood–brain barrier. J Drug Target. 2017;25:17–28.

Deng Y, Gong P, Han S, Zhang J, Zhang S, Zhang B, et al. Reduced cerebral cortex thickness is related to overexpression of exosomal miR-146a-5p in medication-free patients with major depressive disorder. Psychol Med. 2023;53:6253–60.

Wei Z, Xie G, Mao X, Zou X, Liao Y, Liu Q, et al. Exosomes from patients with major depression cause depressive-like behaviors in mice with involvement of miR-139-5p-regulated neurogenesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:1050–8.

Fan C, Li Y, Lan T, Wang W, Long Y, Yu SY. Microglia secrete miR-146a-5p-containing exosomes to regulate neurogenesis in depression. Mol Ther. 2022;30:1300–14.

Fuchs C, Trazzi S, Torricella R, Viggiano R, De Franceschi M, Amendola E, et al. Neurobiology of disease loss of CDKL5 impairs survival and dendritic growth of newborn neurons by altering AKT / GSK-3 β signaling. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;70:53–68.

Honorato-Mauer J, Xavier G, Ota VK, Chehimi SN, Mafra F, Cuóco C, et al. Alterations in microRNA of extracellular vesicles associated with major depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity and anxiety disorders in adolescents. Transl Psychiatry. 2023;13:47.

Qi S, Yang X, Zhao L, Calhoun VD, Perrone-Bizzozero N, Liu S, et al. MicroRNA132 associated multimodal neuroimaging patterns in unmedicated major depressive disorder. Brain. 2018;141:916–26.

Lou J, Liu K, Wen J, He Y, Sun Y, Tian X, et al. Deciphering the neural mechanisms of miR-134 in major depressive disorder with population-based and person-specific imaging transcriptomic techniques. Psychiatry Res. 2023;329:115551.

Qi S, Calhoun VD, Van Erp TGM, Bustillo J, Damaraju E, Turner JA, et al. Multimodal fusion with reference: searching for joint neuromarkers of working memory deficits in schizophrenia. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2018;37:93–105.

Li A, Zalesky A, Yue W, Howes O, Yan H, Liu Y, et al. A neuroimaging biomarker for striatal dysfunction in schizophrenia. Nat Med. 2020;26:558–65.

Rolls ET, Huang CC, Lin CP, Feng J, Joliot M. Automated anatomical labelling atlas 3. Neuroimage. 2020;206:116189.

Davis AK, Barrett FS, May DG, Cosimano MP, Sepeda ND, Johnson MW, et al. Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:481–9.

Heukelum, van S, Mars RB, Guthrie M, Buitelaar JK, Beckmann CF, et al. Where is cingulate cortex? A cross-species view. Trends Neurosci. 2020;43:285–99.

Vogt BA, Paxinos G. Cytoarchitecture of mouse and rat cingulate cortex with human homologies. Brain Struct Funct. 2014;219:185–92.

Haqqani AS, Delaney CE, Tremblay TL, Sodja C, Sandhu JK, Stanimirovic DB. Method for isolation and molecular characterization of extracellular microvesicles released from brain endothelial cells. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2013;10:4.

Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10513–8.

Liu X, Su X, Xu S, Wang H, Han D, Li J, et al. MicroRNA in vivo precipitation identifies miR-151-3p as a computational unpredictable miRNA to target Stat3 and inhibits innate IL-6 production. Cell Mol Immunol. 2018;15:99–110.

Oved K, Morag A, Pasmanik-Chor M, Oron-Karni V, Shomron N, Rehavi M, et al. Genome-wide miRNA expression profiling of human lymphoblastoid cell lines identifies tentative SSRI antidepressant response biomarkers. Pharmacogenomics. 2012;13:1129–39.

Enatescu VR, Papava I, Enatescu I, Antonescu M, Anghel A, Seclaman E, et al. Circulating plasma micro RNAs in patients with major depressive disorder treated with antidepressants: a pilot study. Psychiatry Investig. 2016;13:549–57.

Oved K, Farberov L, Gilam A, Israel I, Haguel D, Gurwitz D. MicroRNA-mediated regulation of ITGB3 and CHL1 is implicated in SSRI action. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:1–19.

Mengel-From J, Feddersen S, Halekoh U, Heegaard NHH, McGue M, Christensen K, et al. Circulating microRNAs disclose biology of normal cognitive function in healthy elderly people – a discovery twin study. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26:1378–87.

Li C, Qin T, Liu Y, Wen H, Zhao J, Luo Z, et al. Microglia-derived exosomal microRNA-151-3p enhances functional healing after spinal cord injury by attenuating neuronal apoptosis via regulating the p53/p21/CDK1 signaling pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;9:783017.

Lee Y, El Andaloussi S, Wood MJA. Exosomes and microvesicles: extracellular vesicles for genetic information transfer and gene therapy. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:R125–34.

Gámez-Valero A, Campdelacreu J, Vilas D, Ispierto L, Reñé R, Álvarez R, et al. Exploratory study on microRNA profiles from plasma-derived extracellular vesicles in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Transl Neurodegener. 2019;8:1–17.

Mundalil Vasu M, Anitha A, Thanseem I, Suzuki K, Yamada K, Takahashi T, et al. Serum microRNA profiles in children with autism. Mol Autism. 2014;5:1–9.

Ries A, Hollander M, Glim S, Meng C, Sorg C, Wohlschläger A. Frequency-dependent spatial distribution of functional hubs in the human brain and alterations in major depressive disorder. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019;13:1–17.

Wu F, Lu Q, Kong Y, Zhang Z. A comprehensive overview of the role of visual cortex malfunction in depressive disorders: opportunities and challenges. Neurosci Bull. 2023;39:1426–38.

Song XM, Hu XW, Li Z, Gao Y, Ju X, Liu DY, et al. Reduction of higher-order occipital GABA and impaired visual perception in acute major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:6747–55.

Hamani C, Mayberg H, Stone S, Laxton A, Haber S, Lozano AM. The subcallosal cingulate gyrus in the context of major depression. BPS. 2010;69:301–8.

Rolls ET. The cingulate cortex and limbic systems for emotion, action, and memory. Brain Struct Funct. 2019;224:3001–18.

Rolls ET, O’Doherty J, Kringelbach ML, Francis S, Bowtell R, McGlone F. Representations of pleasant and painful touch in the human orbitofrontal and cingulate cortices. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:308–17.

Lindgren L, Westling G, Brulin C, Lehtipalo S, Andersson M, Nyberg L. Pleasant human touch is represented in pregenual anterior cingulate cortex. Neuroimage. 2012;59:3427–32.

Grabenhorst F, Rolls ET. Value, pleasure and choice in the ventral prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:56–67.

Rolls ET, Cheng W, Gong W, Qiu J, Zhou C, Zhang J, et al. Functional connectivity of the anterior cingulate cortex in depression and in health. Cereb Cortex. 2019;29:3617–30.

Yuan Z, Qi Z, Wang R, Cui Y, An S, Wu G, et al. A corticoamygdalar pathway controls reward devaluation and depression using dynamic inhibition code. Neuron. 2023;111:3837–53.e5.

Smith ML, Asada N, Malenka RC. Anterior cingulate inputs to nucleus accumbens control the social transfer of pain and analgesia. Science. 2021;371:153–9.

SWETS JA. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science. 1988;240:1285–93.

Kennis M, Gerritsen L, van Dalen M, Williams A, Cuijpers P, Bockting C. Prospective biomarkers of major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:321–38.

Dunbar CE, High KA, Joung JK, Kohn DB, Ozawa K, Sadelain M. Gene therapy comes of age. Science. 2018;359:eaan4672.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32471207), Youth Project of National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 23CSH047), Youth Project of Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2021QH346), and the Independently Cultivate Innovative Teams of Jinan, Shandong Province (No. 202228079). We thank Yufei Li and Wen Liu, from School of Public Health, Shandong University, for valuable support of data collection during the volunteer recruitment period. We appreciate the technical support of Fan Yang, PhD, from Advanced Medical Research Institute, Shandong University. We also express our gratitude to Feifei Xu and Xiaotian Zhao from our Principal Investigator (PI) team for their valuable guidance on the research’s methodology. Some figures were created with biorender.com and have been granted Academic Publication License. We would like to express our sincere gratitude for this.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wenjia Liang and Shuwei Liu designed the research. Wei Wang and Lejin Yang recruited the patients at hospital. Wenjia Liang, Lanwei Hou, Wenjun Wang, Bao Wang, Chenxi Sun and Yuan Zhang collected the MRI and clinical data. Zhuoran Li, Rong Shi, Wenjuan Zhou and Yuchun Tang provided the methodological instruction. Wenjia Liang performed the data analysis and wrote the paper. Shuwei Liu and Lejin Yang substantively revised the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods used in this study were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. All studies involving human subjects have been approved by the Ethical Committee of School of Basic Medical Sciences, Shandong University (No. ECSBMSSDU2022-1-61) and registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2200060261). All animal care and experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health for the care and use of laboratory animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of School of Basic Medical Sciences, Shandong University (No. ECSBMSSDU2022-2-106). All participants voluntarily enrolled in the study and provided written informed consent. Additionally, all participants also signed the informed consent forms for the MR scan and agreed to the publication of the MR images.

Additional information