Abstract

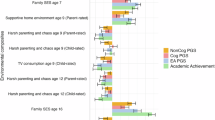

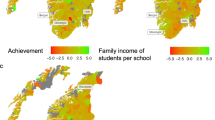

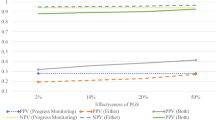

Polygenic score (PGS) predictions of educational achievement are sizeable at the population level. Yet, population-level PGS predictions are environmentally confounded, due to gene-environment correlations, assortative mating, and population stratification. This confounding complicates the interpretation and application of PGS predictions of educational achievement. Here, we charted the variability of PGS predictions in N = 8115 dizygotic twins from UK, US, Swedish, and German samples aged 7 to 19 years. Population-level PGS predictions of educational achievement ranged from β = 0.16 to β = 0.37 across ages and countries. Discerning within- and between-family level estimates, we found that 10 to 65% of the population-level PGS predictions were due to environmental confounding, of which 29 to 100% were accounted for by family socioeconomic status. Variability in within-family and population-level PGS predictions was largely unsystematic across countries’ school systems (multi-tiered vs. comprehensive) and children’s ages. Therefore, interpretations regarding the sources of environmental confounding effects on educational achievement remain, at present, speculative.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets used for this study are not openly available due to privacy and ethical requirements, yet data access can be requested for research purposes from the respective data owners. TEDS data are available upon request (https://www.teds.ac.uk/researchers/teds-data-access-policy). Details on measurement and sample characteristics are available in the TEDS data dictionary (https://www.teds.ac.uk/datadictionary/home.htm). E-Risk data are available upon request (https://www.eriskstudy.com/data-access/). To access the MTFS data, external researchers can request to collaborate with MTFS researchers [69]. The Swedish sample comprises use individual-level register data provided by Statistics Sweden, combined with data from the STR, which is administered by the Steering Committee of the Swedish Twin Registry. To access the data, researchers they must obtain approval from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority and from the Steering Committee of the Swedish Twin Registry. STR data are available upon request (https://ki.se/en/research/swedish-twin-registry-for-researchers). In this study, TwinLife data release 7.1.0 was used (https://doi.org/10.4232/1.14186). Data are available upon request (https://search.gesis.org/research_data/ZA6701). Information on measurement and sample characteristics are available via the TwinLife data documentation website (https://www.twin-life.de/documentation/downloads).

Code availability

No custom code was used for the analyses in this study. Data analyses were conducted in R (version 4.4.0) [48] and RStudio (version 2024.04.1) [70]. The analysis code can be obtained here: https://osf.io/jzp7c/?view_only=10fd9c9885844b519339de63c5a485fe.

Notes

Polygenic scores are also referred to as genome-wide score, polygenic index (PGI), or polygenic risk score/genetic risk score (in the context of medical risk).

References

de Zeeuw EL, de Geus EJC, Boomsma DI. Meta-analysis of twin studies highlights the importance of genetic variation in primary school educational achievement. Trends Neurosci Educ. 2015;4:69–76.

Eifler EF, Starr A, Riemann R The genetic and environmental effects on school grades in late childhood and adolescence. Meyre D, editor. PLOS ONE. 2019;14:e0225946.

Rimfeld K, Malanchini M, Krapohl E, Hannigan LJ, Dale PS, Plomin R. The stability of educational achievement across school years is largely explained by genetic factors. Npj Sci Learn. 2018;3:16.

Shakeshaft NG, Trzaskowski M, McMillan A, Rimfeld K, Krapohl E, Haworth CMA, et al. Strong genetic influence on a UK nationwide test of educational achievement at the end of compulsory education at age 16. Ansari D, editor. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80341.

Allegrini AG, Selzam S, Rimfeld K, von Stumm S, Pingault JB, Plomin R. Genomic prediction of cognitive traits in childhood and adolescence. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:819–27.

Lee JJ, Wedow R, Okbay A, Kong E, Maghzian O, Zacher M, et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1112–21.

Okbay A, Wu Y, Wang N, Jayashankar H, Bennett M, Nehzati SM, et al. Polygenic prediction of educational attainment within and between families from genome-wide association analyses in 3 million individuals. Nat Genet. 2022;54:437–49.

Wilding K, Wright M, von Stumm S. Using DNA to predict education: a meta-analytic review. Educ Psychol Rev. 2024;36:102.

Selzam S, Ritchie SJ, Pingault JB, Reynolds CA, O’Reilly PF, Plomin R. Comparing within- and between-family polygenic score prediction. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;105:351–63.

Demange PA, Hottenga JJ, Abdellaoui A, Eilertsen EM, Malanchini M, Domingue BW, et al. Estimating effects of parents’ cognitive and non-cognitive skills on offspring education using polygenic scores. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4801.

Howe LJ, Nivard MG, Morris TT, Hansen AF, Rasheed H, Cho Y, et al. Within-sibship genome-wide association analyses decrease bias in estimates of direct genetic effects. Nat Genet. 2022;54:581–92.

Veller C, Coop GM. Interpreting population- and family-based genome-wide association studies in the presence of confounding. Moorjani P, editor. PLoS Biol 2024;22:e3002511.

Malanchini M, Allegrini AG, Nivard MG, Biroli P, Rimfeld K, Cheesman R, et al. Genetic associations between non-cognitive skills and academic achievement over development. Nat Hum Behav [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 27]; Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-024-01967-9.

Bates TC, Maher BS, Medland SE, McAloney K, Wright MJ, Hansell NK, et al. The nature of nurture: Using a virtual-parent design to test parenting effects on children’s educational attainment in genotyped families. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2018;21:73–83.

Kong A, Thorleifsson G, Frigge ML, Vilhjalmsson BJ, Young AI, Thorgeirsson TE, et al. The nature of nurture: Effects of parental genotypes. Science. 2018;359:424–8.

Wang B, Baldwin JR, Schoeler T, Cheesman R, Barkhuizen W, Dudbridge F, et al. Robust genetic nurture effects on education: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on 38,654 families across 8 cohorts. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108:1780–91.

Plomin R, DeFries JC, Loehlin JC. Genotype-environment interaction and correlation in the analysis of human behavior. Psychol Bull. 1977;84:309–22.

Wertz J, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Barnes JC, Boivin M, Corcoran DL, et al. Genetic associations with parental investment from conception to wealth inheritance in six cohorts. Nat Hum Behav. 2023;7:1388–401.

Abdellaoui A, Hugh-Jones D, Yengo L, Kemper KE, Nivard MG, Veul L, et al. Genetic correlates of social stratification in Great Britain. Nat Hum Behav. 2019;3:1332–42.

Morris TT, Davies NM, Hemani G, Smith GD. Population phenomena inflate genetic associations of complex social traits. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaay0328.

Yengo L, Robinson MR, Keller MC, Kemper KE, Yang Y, Trzaskowski M, et al. Imprint of assortative mating on the human genome. Nat Hum Behav. 2018;2:948–54.

Brumpton B, Sanderson E, Heilbron K, Hartwig FP, Harrison S, Vie GÅ, et al. Avoiding dynastic, assortative mating, and population stratification biases in Mendelian randomization through within-family analyses. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3519.

Pingault J, Allegrini AG, Odigie T, Frach L, Baldwin JR, Rijsdijk F, et al. Research review: how to interpret associations between polygenic scores, environmental risks, and phenotypes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2022;63:1125–39.

Zhou Q, Gidziela A, Allegrini AG, Cheesman R, Wertz J, Maxwell J, et al. Gene-environment correlation: the role of family environment in academic development. Mol Psychiatry [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 24]; Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-024-02716-0.

Kendler KS, Baker JH. Genetic influences on measures of the environment: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2007;37:615.

van Hootegem A, Rogne AF, Lyngstad TH. Heritability of class and status: implications for sociological theory and research. Res Soc Stratif Mobil. 2024;92:100940.

von Stumm S, Smith-Woolley E, Ayorech Z, McMillan A, Rimfeld K, Dale PS, et al. Predicting educational achievement from genomic measures and socioeconomic status. Dev Sci. 2020;23:e12925.

Haworth CMA, Wright MJ, Luciano M, Martin NG, De Geus EJC, Van Beijsterveldt CEM, et al. The heritability of general cognitive ability increases linearly from childhood to young adulthood. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:1112–20.

Ruks M, Starr A, Dierker P. Investigating the heritability of school grades from age 10 to 16 using biometric growth curve models [Internet]. PsyArXiv; 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 18]. Available from: https://osf.io/vecy9.

Tucker-Drob EM, Briley DA, Harden KP. Genetic and environmental influences on cognition across development and context. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22:349–55.

Wößmann L. The importance of school systems: evidence from international differences in student achievement. J Econ Perspect. 2016;30:3–32.

Borghans BL, Diris R, Smits W, De Vries J. Should we sort it out later? The effect of tracking age on long-run outcomes. Econ Educ Rev. 2020;75:101973.

Burger K. Intergenerational transmission of education in Europe: Do more comprehensive education systems reduce social gradients in student achievement? Res Soc Stratif Mobil. 2016;44:54–67.

Engzell P, Raabe IJ. Within-school achievement sorting in comprehensive and tracked systems. Sociol Educ. 2023;96:324–43.

Freeman RB, Viarengo M. School and family effects on educational outcomes across countries. Econ Policy. 2014;29:395–446.

Terrin É, Triventi M. The effect of school tracking on student achievement and inequality: A meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res. 2023;93:236–74.

van de Werfhorst HG. Early tracking and social inequality in educational attainment: Educational reforms in 21 European countries. Am J Educ. 2019;126:65–99.

Dumont H, Klinge D, Maaz K. The many (subtle) ways parents game the system: mixed-method evidence on the transition into secondary-school tracks in Germany. Sociol Educ. 2019;92:199–228.

Stull JC. Family socioeconomic status, parent expectations, and a child’s achievement. Res Educ. 2013;90:53–67.

Esping-Andersen G. Welfare regimes and social stratification. J Eur Soc Policy. 2015;25:124–34.

Young AI. genome-wide association studies have problems due to confounding: are family-based designs the answer? PLoS Biol. 2024;22:e3002568.

Young AI, Benonisdottir S, Przeworski M, Kong A. Deconstructing the sources of genotype-phenotype associations in humans. Science. 2019;365:1396–400.

Cumming G, Finch S. inference by eye: confidence intervals and how to read pictures of data. Am Psychol. 2005;60:170–80.

Gelman A, Stern H. The difference between “significant” and “not significant” is not itself statistically significant. Am Stat. 2006;60:328–31.

Paternoster R, Brame R, Mazerolle P, Piquero A. Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology. 1998;36:859–66.

Fisher RA. On the ’probable error’ of a coefficient of correlation deduced from a small sample. Metron. 1921;1:1–32.

Eid M, Gollwitzer M, Schmitt M. Statistik und Forschungsmethoden. 2nd ed. Weinheim: Beltz; 2011. 1024 p.

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Internet]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2024. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/.

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2023 Oct 23];67. Available from: http://www.jstatsoft.org/v67/i01/.

Polderman TJC, Benyamin B, de Leeuw CA, Sullivan PF, van Bochoven A, Visscher PM, et al. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat Genet. 2015;47:702–9.

Silventoinen K, Jelenkovic A, Sund R, Latvala A, Honda C, Inui F, et al. Genetic and environmental variation in educational attainment: an individual-based analysis of 28 twin cohorts. Sci Rep. 2020;10:12681.

Esping-Andersen G. The three political economies of the welfare state. Int J Sociol. 1990;20:92–123.

Osberg L. Long run trends in income inequality in the United States, UK, Sweden, Germany and Canada: A birth cohort view. East Econ J. 2003;29:121–41.

Gregg P, Jonsson JO, Macmillan L, Mood C. The role of education for intergenerational income mobility: A comparison of the United States, Great Britain, and Sweden. Soc Forces. 2017;96:121–52.

Heisig JP, Elbers B, Solga H. Cross-national differences in social background effects on educational attainment and achievement: absolute vs. relative inequalities and the role of education systems. Comp J Comp Int Educ. 2020;50:165–84.

Johnson W, Deary IJ, Silventoinen K, Tynelius P, Rasmussen F. Family background buys an education in Minnesota but not in Sweden. Psychol Sci. 2010;21:1266–73.

Ross NA, Dorling D, Dunn JR, Henriksson G, Glover J, Lynch J, et al. Metropolitan income inequality and working-age mortality: a cross-sectional analysis using comparable data from five countries. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2005;82:101–10.

Ehrenberg RG, Brewer DJ, Gamoran A, Willms JD. Class size and student achievement. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2001;2:1–30.

López-Martín E, Gutiérrez-de-Rozas B, González-Benito AM, Expósito-Casas E. Why do teachers matter? A meta-analytic review of how teacher characteristics and competencies affect students’ academic achievement. Int J Educ Res. 2023;120:102199.

Buckingham J, Wheldall K, Beaman-Wheldall R. Why poor children are more likely to become poor readers: The school years. Aust J Educ. 2013 Nov;57:190–213.

Tan CY, Lyu M, Peng B. Academic benefits from parental involvement are stratified by parental socioeconomic status: A meta-analysis. Parenting. 2020;20:241–87.

Coldron J, Cripps C, Shipton L. Why are english secondary schools socially segregated? J Educ Policy. 2010;25:19–35.

Cullinane C, Hillary J, Andrade J, McNamara S. SELECTIVE COMPREHENSIVES 2017 Admissions to high-attaining non-selective schools for disadvantaged pupils [Internet]. The Sutton Trust; 2017. Available from: https://www.suttontrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Selective-Comprehensives-2017.pdf.

Hamnett C, Ramsden M, Butler T. Social background, ethnicity, school composition and educational attainment in East London. Urban Stud. 2007;44:1255–80.

Moerenhout K, van den Berg D, de Wit M, Peyrot W, Abdellaoui A. Migration, assortative mating, and educational attainment. In London, UK; 2024.

Hällsten M, Kolk M. The shadow of peasant past: Seven generations of inequality persistence in Northern Sweden. Am J Sociol. 2023;128:1716–60.

Nivard MG, Belsky DW, Harden KP, Baier T, Andreassen OA, Ystrøm E, et al. More than nature and nurture, indirect genetic effects on children’s academic achievement are consequences of dynastic social processes. Nat Hum Behav [Internet]. 2024 Jan 15 [cited 2024 Apr 18]; Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-023-01796-2.

Singh C. A comparative analysis of attrition in household panel studies. (Research Papers on Comparative Analysis of Longitudinal Data; No. 10) [Internet]. CEPS/INSTEAD; 1995. Available from: https://liser.elsevierpure.com/files/11791910/Working%20Paper%20n%C2%B010.

Iacono WG, McGue M. Minnesota twin family study. Twin Res. 2002;5:482–7.

Posit team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. [Internet]. Boston, MA: Posit software, PBC; 2024. Available from: http://www.posit.co/.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participating families and many contributors to the Twins Early Development Study (TEDS), the Minnesota Twin Family Study, the Swedish Twin Registry (STR), and TwinLife. We are grateful to the Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study mothers and fathers, the twins, and the twins’ teachers for their participation. Our thanks to Professors Terrie Moffitt and Avshalom Caspi, the founders of the E-Risk Study, and to the E-Risk team for their dedication, hard work and insights. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the ESRC or King’s College London.

Funding

TEDS is supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MR/V012878/1 and previously MR/M021475/1), with additional support from the US National Institutes of Health (AG046938). The Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Study is funded by grants from the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) [G1002190; MR/X010791/1]. Additional support for E-Risk was provided by the US National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [HD077482] and the Jacobs Foundation. The Minnesota Twin Family Study was supported in part through grants from the National Institutes of Health R01 DA 042755, R01HG011035, R01 DA 054087, R01 DA 044283. The Swedish Twin Registry (STR) is managed by the Karolinska Institute and receives additional funding through the Swedish Research Council (2017-00641). Additional funding for STR comes from the Ragnar Söderberg Foundation (E9/11), and the Swedish Research Council (421-2013-1061). TwinLife is funded by grants from the German Research Foundation (DFG; project number: 220286500 and 428902522). SvS held fellowships from the Jacobs Foundation (2022-2027) and the Paris Institute of Advanced Study (2023-2024) during the writing of this manuscript. HLF was supported by the UK ESRC Centre for Society and Mental Health at King’s College London [ES/S012567/1]. The position of CP is funded by the DFG (funding number 428902552). OP, RA, and SO were supported by the Swedish Research Council (2019-00244; 2023-01343).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: AS and SvS, Methodology: AS and MR, Formal analysis: AS, MR, AG, OP, and CKLP, Resources: RA, LA, HLF, AJF, CK, MM, MMN, SO, FMS, SV, JW, and SvS, Data curation: AS, MR, AG, EW, OP, CKLP, CM, and AA, Writing – Original draft: AS and SvS, Writing – Review & Editing: All authors, Visualization: AS, Supervision: RA, LA, HLF, AJF, CK, MM, MMN, SO, FMS, SV, JW, and SvS, Funding acquisition: RA, LA, HLF, AJF, CK, MM, MMN, SO, FMS, SV, and SvS, All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Starr, A., Ruks, M., Giannelis, A. et al. Within- and between-family genetic effects on educational achievement vary across countries and ages. Mol Psychiatry (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03342-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03342-0