Abstract

Novel treatment evaluation for youth with alcohol use disorder (AUD) is needed. Cannabidiol (CBD), a constituent of the Cannabis sativa plant, may be a promising candidate pharmacotherapy due to its potential therapeutic properties and preclinical research suggesting it decreases alcohol use. Due to limited data in humans, rigorous screening of the acute neural, psychophysiological, and alcohol-related effects of CBD is indicated to assess its viability as a potential treatment for youth AUD. Using a within-subjects, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design, we tested acute multi-modal effects of CBD (600 mg) in non-treatment seeking youth with AUD (N = 36; ages 17–22; 69% female). Outcomes included (1) glutamate+glutamine (Glx) and GABA levels in the anterior cingulate cortex measured with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy; (2) whole-brain and a priori region-of-interest neural alcohol cue-reactivity measured with functional MRI; (3) psychophysiological response to alcohol olfactory cues measured by self-reported acute alcohol craving, heart rate variability, and skin conductance; and (4) alcohol use. No CBD-associated adverse events were observed. There were no effects of acute CBD administration, compared to placebo, on any outcomes of interest. This is the first adequately powered medication screening study for the use of CBD in youth with AUD. We did not detect significant effects of CBD on neurometabolic, neurobehavioral, psychophysiological, or alcohol use outcomes in this sample. Future studies may benefit from chronic administration to better understand substance-related effects.

Clinicaltrials.gov NCT05317546 https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05317546

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nearly 15% of adolescents meet diagnostic criteria for AUD by age 18 [1]. Current treatments for youth with AUD are primarily psychosocial, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, family-based therapy, and motivational interviewing [2]. Given the modest efficacy of current psychosocial treatments [3,4,5,6,7], pharmacotherapy has been explored as a complement to the standard of care [8]. There are limited data regarding the efficacy of pharmacotherapy in treating youth with AUD [9]. This calls for the evaluation of novel treatments specifically for youth to effectively intervene early in the AUD trajectory.

Cannabidiol (CBD) may be a promising candidate pharmacotherapy for youth with AUD. CBD is a constituent of the Cannabis sativa plant that has garnered attention as an alternative therapy [10]. A growing preclinical literature [11] indicates that CBD reduces alcohol consumption and motivation to drink [12,13,14,15], alcohol relapse and withdrawal [13, 16], and alcohol-related neurotoxicity [17, 18]. CBD is particularly intriguing as a treatment option for youth with AUD since it is non-intoxicating, is generally well-tolerated, and demonstrates no signal of abuse liability [19,20,21]. Further, young people tend to have a more positive attitude towards “natural” or “alternative” medicine [22, 23], making CBD a more appealing option than currently approved pharmacotherapies for adults with AUD.

CBD may affect alcohol consumption [24, 25] and AUD-like behaviors via its multiple brain targets that overlap with systems underlying AUD. CBD can act as an inverse agonist or negative allosteric modulator of cannabinoid receptors (CB1, CB2) [26,27,28,29] and can modulate endocannabidoid system signaling through inhibiting the enzymatic breakdown of anandamide, an endogenous cannabinoid ligand [30, 31]. CB1 and CB2 receptors are expressed throughout the mesocorticolimbic pathway, which is highly implicated in addictive behaviors (e.g., reward, decision-making, substance intake, motivation, withdrawal, and relapse) [32,33,34,35]. Thus, CBD may exert its effects on AUD symptoms through direct or indirect modulation of the endocannabinoid system. Beyond the endocannabinoid system, CBD has been shown to modulate glutamate [36, 37], gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) [38], dopamine [39], serotonin [40, 41], and opioid [42] neurotransmission, all of which are implicated in AUD and have each been proposed as treatment targets for adult AUD pharmacotherapies [43]. The proposed neural mechanisms of action for CBD provides biological plausibilty for its potential use in AUD.

Due to the lack of data in humans, and youth in particular, it is important to rigorously screen the acute neural, psychophysiological, and substance use effects of CBD in youth with AUD prior to large scale clinical trials [44, 45]. While there are limitations to assessing in vivo neural mechanims in humans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides non-invasive techniques, such as measuring neurochemistry with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) and alcohol cue-reactivity for a proxy of craving with functional MRI (fMRI) [46]. Along with other neurometabolites, 1H-MRS can measure glutamate and GABA levels in the brain, which are both affected by alcohol use [47], common targets for AUD medication development [48,49,50], and have been modulated by CBD in preclinical work [36,37,38]. Limited work in humans indicates that an acute dose of 600 mg of CBD can alter neurometabolite levels; individuals with psychosis [51] and austim spectrum disorder (ASD) [52] demonstrated increased glutmate levels with this 600 mg single-dose administration. Additionally, CBD adminstration resulted in decreased levels of GABA in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with ASD [52].

fMRI localizes and quantifies brain activity, allowing for a mechanistic understanding of the neural substrates affected by CBD. Specifically, fMRI alcohol cue-reactivity tasks are of interest in early medication screening studies as they can activate incentive salience and reward circuitry that underpin AUD symptomology [53]. Alcohol cue-reactivity tasks can correlate with alcohol craving [54], which is an important component to consider during AUD treatment development. Importantly, neural reactivity to alcohol cues has been modulated by previous pharmacological interventions [54, 55], making it a useful screening method during early translational studies.

Beyond the brain, CBD may exert effects on salient psychophysiological responses to alcohol cues. Psychophysiological effects of CBD can be assessed using an olfactory alcohol cue-reactivity task measuring heart rate, skin conductance, and subjective alcohol craving in response to a preferred beverage containing alcohol [56]. This in vivo task is appropriate for youth, given oral administration of alcohol to underage youth is unethical. Together, measuring the neural and the psychophysiological reactivity to alcohol using multiple sensory modalities (i.e., visual and olfactory) will help to provide a more comprehensive understanding of CBD’s mechanisms.

This study represents the first medication screening procedure designed to investigate the effects of CBD in youth with AUD. Using a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover design, we tested the acute neurometabolic, neurobehavioral, and psychophysiological effects of CBD in non-treatment seeking youth with AUD. We hypothesized that after CBD administration, youth with AUD would have: (1) increased glutamate (as glutamate + glutamine, or Glx) and GABA levels in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), indicating changes in two neurotransmitter systems involved in addictive behaviors [57,58,59] that have been proposed as therapeutic targets of CBD [36,37,38]; (2) decreased alcohol cue-reactivity in reward-related neural regions [60], indicating changes in craving which is a proposed therapeutic mechanism of CBD in substance use disorders [16, 61]; and (3) lower in vivo psychophysiological response to olfactory alcohol cues [62], which may be due to the anxiolytic effects of CBD [63]. As an exploratory analysis, we also assessed if CBD impacted alcohol use behaviors up to 7-days after administration, as compared to placebo. This multi-modal approach (neuroimaging, psychophysiological response, and alcohol use assessment) was intended to provide complementary insights into the potential effects and mechanisms of CBD in youth with AUD.

Methods

Participants

48 non-treatment seeking participants (17–22 years old) were recruited (Fig. 1) from September 2022 to April 2024, and data collection was completed in June 2024. For inclusion, all participants met criteria for AUD in the past year, had at least 1 AUD symptom in the past 30 days (besides craving), and drank alcohol within 2 weeks prior to screening. See supplemental materials for exclusion criteria. Participants were recruited using a mix of approaches, including social media campaigns and in-person events.

Consent and screening

All participants provided written informed consent/assent, and dual written permission was obtained from parents/guardians of individuals under the age of 18 years. All participants completed a centralized intake process for youth substance use studies at the Medical University of South Carolina to determine eligibility before consenting for this specific study [64]. The centralized intake process has been described in detail elsewhere [64]. In brief, the eligibility criteria for multiple studies enrolling a similar population are concurrently assessed using an IRB-approved protocol, and participants consent to share their screening data with the study in which they ultimately enroll. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) was administered to ascertain current or lifetime history of the major psychiatric disorders in DSM-5 and ICD-10 [65, 66], including past year AUD and any continuing symptoms in the 30-days per inclusion criteria. A medical clinician assessed health (e.g., current medication use) and safety to participate in the study during screening.

Procedures

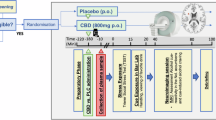

All procedures were approved by the local IRB and registered on Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05317546; Fig. 2). In counterbalanced order, participants received either 600 mg of CBD (Epidiolex) oral solution [51, 52, 67, 68] or a matched placebo (sesame oil with strawberry flavoring). All participants ate a high-fat snack (70% fat content) in the presence of study staff prior to medication administration to increase the bioavailability of CBD [60]. Human laboratory and imaging procedures were conducted between 2 and 3 h after medication administration to allow for peak plasma concentration [52, 69]. Of note, the olfactory cue-reactivity task [56], 1H-MRS [70, 71], and fMRI alcohol cue reactivity [55, 72] procedures have all been previously conducted in youth. There was a minimum 18-day washout between medication administration visits [73] (terminal half-life 18–32 h after acute oral dose [74]) and before the virtual follow-up visit. See supplemental materials for more details. Over the 18-day washout periods, participants were sent daily surveys to document substance use. REDCap was used for data collection and storage [75]. Participants met with a medical clinician at every medication visit who assessed medication use, general health, and adverse events.

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy

See minimum reporting standards for 1H-MRS data in Table S1 [76]. All scans were performed with a Siemens 3.0 T Prismafit MR scanner with actively shielded magnet and high-performance gradients (80 mT/m, 200 T/m-sec) with a 32-channel head coil. The dorsal ACC (dACC) voxel for 1H-MRS was placed on midsagittal T1-weighted images (Fig. S1), anterior to the genu of the corpus callosum, with the ventral edge of the voxel aligned with the dorsal edge of the genu [63], with a voxel size of (30 × 25 x 25) mm3 [63, 64]. Following FAST(EST)MAP shimming [65], single-voxel water-suppressed (water suppression bandwidth 50 Hz for Glx or 100 Hz for GABA + , spectral bandwidth 2000 Hz, 1024 spectral points) 1H-MRS spectra is acquired with the following sequences: (1) glutamate and other metabolites: SIEMENS Point Resolved Spectroscopy (PRESS) sequence: Repetition Time (TR) = 2000 ms; Echo Time (TE) = 40 ms; number of averages = 256; and (2) GABA + : SIEMENS WIP MEGA-PRESS sequence: Edit ON(OFF) = 1.90 (7.46) ppm; TR = 2000 ms, TE = 68 ms; number of averages= 160. Example spectrums are shown in Figs. S2, S3. Unsuppressed water spectra were co-acquired and scaled for partial volume effects and relaxation and used as a concentration reference. Six saturation bands (41 mm thickness) were placed 0.8 mm from each voxel face for outer volume suppression. MRS data were processed using Osprey [67], described in more detail in the supplemental materials.

fMRI cue-reactivity task

For the alcohol cue-reactivity task [77], participants were shown pseudo-randomly interspersed images of alcohol (i.e., beer, wine, and hard liquor) and non-alcohol (e.g., soft drink, juice) beverages, visual control images (i.e., blurred images), and a fixation cross. See supplemental materials for more task details.

Functional and anatomical preprocessing was performed using FSL FEAT (v6.00, FMRIB’s Software Library), described in more detail in the supplemental materials. First-level statistical analysis was performed using the general linear model (GLM) to model task-related activity. Experimental conditions (alcohol beverage, non-alcohol beverage, blurred images, rest, and rating blocks) were modeled as explanatory variables (EVs), each convolved with a double-gamma hemodynamic response function. The main contrasts of interest were the alcohol beverage block and alcohol – non-alcohol beverage contrast. Lower-level FEAT directories were used for higher level mixed-effects analysis (FLAME 1) to estimate group-level effects (CBD vs. placebo). For whole brain analyses, cluster-based correction for multiple comparisons was performed using Gaussian random field theory with a cluster-forming threshold of Z > 3.1 and a corrected significance threshold of p < 0.05. For region of interest (ROI) analyses, FEATQuery was used with Z > 3.1 and a corrected significance threshold of p < 0.05. ROIs of interest included: the midline dACC and bilateral amygdala, caudate, insula, nucleus accumbens, and putamen [70, 78].

Psychophysiological olfactory cue-reactivity task [56]

All participants underwent an in vivo, olfactory alcohol cue exposure procedure before the neuroimaging session. As many participants were under the legal drinking age in the United States, olfactory cues were used rather than taste cues. Prior to the task, all participants were asked to smell a candle and identify the scent (cinnamon) to ensure their ability to complete the olfactory task. Participants smelled water followed by the participant’s preferred beverage containing alcohol and apple juice (as this is not typically used as a mixer with alcohol) in a counterbalanced order for three minutes each, with a three-minute rest period in between each liquid. The contents were poured into a cup in the participant’s presence. After each beverage exposure, self-reported alcohol craving was collected via the PhenX Toolkit Alcohol Urges Questionnaire (AUQ). The AUQ consists of eight statements about the participant’s feelings and thoughts about drinking as they are completing the questionnaire (i.e., right now). The participant was asked to respond to each statement about alcohol craving via a 7-item Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Electrocardiogram (ECG), skin conductance data, and breathing rate via respiration belt were continuously recorded throughout the task using the AcqKnowledge data acquisition system (Biopac Systems, Inc., Goleta, CA). See supplemental materials for more details. The ECG data were used to create the heart rate variability (HRV) outcomes related to the sympathetic response, vagal response, their ratio (sympathetic: vagal), respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD), standard deviation of successive differences (SDSD), and percentage of NN50 intervals (pNN50). See Table S2 for definitions.

Substance use

Substance use histories were assessed using a modified Timeline Follow-Back [79] (TLFB) to obtain information on typical use of alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, and other substances at screening. TLFB was completed for the 60 days prior to the screening visit to establish eligibility for the study and used as baseline covariates (details below). The following substance use variables were calculated: (1) total number of standard drinks, (2) average number of standard drinks on drinking days, (3) total number of alcohol use days, (4) binge drinking episodes (4+ drinks for females, 5+ drinks for males per day), (5) nicotine use days, and (6) cannabis use days (summed over various methods of use for nicotine and cannabis).

Over the two medication washout periods, participants reported daily substance use (i.e., alcohol, cannabis, nicotine, and other substances) through secure REDCap surveys sent via text message each morning [75, 80, 81]. See supplemental materials for more details.

To assess the acute effects of CBD, we analyzed self-reported alcohol use in the 7-days after CBD/placebo administration, inclusive of medication dose day. We selected this timeframe considering several factors. First, medication-related effects following a 1-time dose of CBD are anticipated to be short-term (e.g., half-life estimated at 18–32 h after acute oral dose). Second, youth typically engage in episodic binge drinking often occurring on or before weekends. Thus, we selected a short timeframe that would also allow for weekends to be captured, regardless of which weekday medication was administered to prevent any confounding factors. One participant was excluded, as only one daily report was completed before dropout.

Adverse events

A thorough evaluation was conducted by a licensed medical clinician at each visit, and adverse events were coded using MedDRA terminology by body system, severity, and relatedness to study treatment.

Statistical analysis

An a priori power analysis was conducted to ensure power to detect differences in neurometabolite levels in the dACC and fMRI alcohol cue-reactivity. See supplemental materials for more details. Given limited literature in this area, we were not able to run a power analysis for the psychophysiological olfactory task nor the substance use outcomes; this study will provide data to power future trials.

All analyses were conducted in R Statistical Software (v4.4.2; R Core Team 2024), except for the fMRI cue-reactivity models detailed above. Significance was set at alpha <0.05. The distribution of each variable was evaluated with Shapiro Wilks tests, and non-parametric tests were used for those that were not normally distributed. For 1H-MRS data quality, two sample t-tests or Wilcoxon tests were completed to assess for medication differences.

We used linear mixed effects models (lme4 package [82]), containing the main effect of medication (CBD vs. placebo), visit (visit 1 vs. visit 2), and sequence (CBD/placebo vs. placebo/CBD) to ensure the crossover design and washout period were successful. Random intercepts were included to account for individual differences. Model assumptions were checked with Performance package [83] and DHARMa package [84]. When needed, robust standard errors were used for models with heteroscedasticity [85,86,87,88]. The following covariates were considered: age, sex, 1-year AUD symptom count, 1-year AUD severity (2-3 symptoms = mild, 4-5 symptoms = moderate, and 6 or more = severe), drinks per drinking day (DPDD), total drinking days, and total binge drinking days. Covariates were tested using the likelihood-ratio test (lrtest package [89]) and included if they significantly improved model fit. For 1H-MRS models, brain tissue composition [Gray Matter: Brain Matter or GM:BM defined as GM/(GM + WM)] was included as a covariate.

For the olfactory task, models for AUQ, HRV, and SCR were first run as described above with additional cue (water, apple juice, or alcohol) and cue-by-medication interaction terms. The interaction term was included for AUQ models, but not for HRV or SCR, as cues did not elicit significantly different responses in HRV and SCR.

Exploratory daily diary analyses focused on alcohol use collected between medication doses. For the outcome, daily number of drinks, a mixed-effects, zero-inflated negative binomial regression model was used instead (glmmTMB package) due to a substantial number of zeros (i.e., non-drinking days).

Our registered main outcomes were 1H-MRS levels of Glx and GABA + ; fMRI alcohol cue-reactivity; and the physiological outcomes from the olfactory cue-reactivity lab-based paradigm. Thus, the daily diary analyses and additional neurometabolites (tNAA, tCho, tCr, and mI) were exploratory (NCT05317546).

Results

Participants

36 participants were randomized (age 17.6–22.8). Almost 70% of the participants reported being biologically female at birth, 66.7% of the full sample identified as being a woman, and 86% of participants reported being white. For past 1-year AUD severity criteria, 55.6% met for mild AUD, 27.8% met for moderate AUD, and 16.7% met for severe AUD. A lower number of participants met for cannabis use disorder (44.4%). Over half the sample reported current medication use at screening (66.1%), and there were 13 reports of changes to medication use at Visit 1 (n = 5), Visit 2 (n = 6), or Visit 3 (n = 2). Medication additions were mainly antibiotics, cold medicine, or allergy medicine (53.4%), ADHD (15.4%), skin conditions (7.7%), weight loss medication (7.7%), or changes to dosing of medications already reported (15.8%). See Table 1 for complete participant demographics.

1H-MRS

There were no significant medication-related differences for any neurometabolite levels in the dACC (Fig. S4, Table 2). There were significant effects for past 1-year AUD symptom count, where high symptom counts related to lower levels of Glx (B = −0.23; p < 0.01) and tCho (B = −0.07; p < 0.01). More past-60-day binge drinking days at screening corresponded with lower levels of GABA+ (B = −0.02; p = 0.02). Finally, tNAA was related to brain tissue composition (defined by GM:BM; B = −8.86; p < 0.001). Tables S3, S4 show the metabolite descriptives, tissue composition, and data quality metrics. The data quality metrics were high and the CoV was low, indicating overall good data quality. There were no significant differences between CBD compared to placebo for any data quality or tissue composition outcomes, indicating consistency between CBD and placebo scans.

fMRI alcohol cue-reactivity task

Neither whole brain analyses nor ROI analyses indicated any difference in neural reactivity to alcohol cues (alcohol cues alone, alcohol – non-alcohol beverage cues) during acute CBD administration compared to placebo (Z > 3.1, p > 0.05).

Psychophysiological olfactory cue-reactivity task

For the AUQ models assessing acute alcohol craving during the olfactory cue-reactivity task (descriptives in Table S5), the cue term was significant and retained in the model (Table S6). There were no significant effects of CBD on AUQ scores, nor was there a significant cue-by-medication interaction (Fig. 3). This indicates the olfactory alcohol cues were associated with higher reported acute craving, which was not affected by CBD as compared to placebo.

For the HRV and SCR models assessing physiological response during the olfactory cue-reactivity task, the cue term was insignificant and not retained in the model. Instead, HRV and SCR across the full task was assessed. There were no significant medication effects for any HRV (Table S7-8, Fig. S5) or SCR outcomes (Table S9-10, Fig. S6).

Alcohol Use 7-days after CBD/placebo administration

On average, participants consumed alcohol on 30% of days in the week following each medication dose (descriptives in Table S11). Medication condition did not significantly predict daily number of drinks consumed (p = .261). The covariate, baseline DPDD was associated with greater daily drinking (p < .001) (Table S12).

Safety

No adverse events or serious adverse events were reported in relation to CBD during the study, supporting CBD’s safety profile in youth with AUD.

Discussion

CBD is often marketed and purported to treat psychiatric disorders, including alcohol and other substance use disorders, despite a lack of randomized controlled trials supporting this claim [63]. The present study is the first medication screening procedure investigating the neurometabolic, neurobehavioral, psychophysiological, and alcohol use effects of an acute dose of CBD (600 mg) compared to placebo in youth with AUD. Consistent with previous studies, the safety profile of CBD was supported. We hypothesized that CBD would impact glutamatergic and GABAergic systems, two neurotransmitters involved in addictive behaviors [57,58,59] that have been proposed as therapeutic targets of CBD [36,37,38]; decrease alcohol-cue reactivity in reward-related neural regions through reductions in craving [16, 61]; and lower in vivo psychophysiological response to olfactory alcohol cues, possibly due to the anxiolytic effects of CBD [63]. However, there were no significant effects of CBD, compared to placebo, across the multi-modal methods (neural, psychophysiological, and alcohol use). The null effects should be interpreted within the constraints of the study design and can help inform future research assessing more clinically relevant effects of CBD in youth with AUD, such as chronic dosing, inter-individual variability of CBD’s bioavailability, and the use of more salient cue-reactivity tasks.

Overall, our results contradict recent CBD studies in samples of adults with AUD. Zimmermann et al. [60] found that a single 800 mg dose of CBD in adults with AUD (N = 28, average age = 35.8) resulted in lower alcohol-cue activation in the nucleus accumbens and lower self-reported craving compared to placebo [60]. Similarly to the present study, their procedures were conducted 3 h after CBD or placebo administration. However, their parallel group design utilized a combined stress- and alcohol- cue exposure task that took place outside of the scanner and before the fMRI alcohol cue-reactivity task, which may have primed craving and neural reactivity. They also used a different formulation of CBD ( > 99.8% synthetic CBD) at a slightly higher dose and assessed blood levels of CBD, which was importantly related to outcomes. Hurzeler et al. found significant effects of 3-days of 800 mg of CBD compared to placebo (N = 22, average age = 29.0) on psychophysiological, anxiety, and alcohol craving to alcohol cues (compared to juice) outside the scanner and neural response to visual alcohol cues inside the scanner [62, 90]. Both studies implemented the outside scanner cue reactivity tasks in a bar setting, which might increase response due to environmental cues. The differences from our study may be a result of methods (e.g., dosing, stimuli, setting), age, AUD severity/duration, or other demographics.

The lack of neural effects of CBD may be indicative of sample characteristics, such as age and AUD severity. Our previously published work suggests that youth who use alcohol may not incur, or at least not at the same degree, the neurometabolic effects that are seen in adults with alcohol misuse or AUD [47, 70]. Specifically, we previously did not find differences in neurometabolites within the ACC of youth who use alcohol, or in the sub-sample of youth with AUD, compared to youth who did not use alcohol [70]. This contradicts findings in adults that suggests lower levels of both GABA and NAA in the ACC related to alcohol use [47]. Our previously reported sample [68] was younger (17–19 years old; average age 18.8) than the currently reported sample (17–22 years old; average age 20.5) and was not required to meet criteria for AUD for inclusion. The differing sample characteristics are of interest considering the current study found lower levels of Glx and tCho are related to higher past 1-year AUD symptom count and lower GABA+ levels were related to higher binge drinking days. The latter has also been shown in college students who report binge drinking [91]. This suggests that alterations in neurometabolite levels may begin to develop in early adulthood (e.g., after the age of 19). If this alcohol-related developmental effect is true, then 1H-MRS may not be granular enough to capture the effects of CBD, or other medications [71], on neurometabolite levels in youth.

The fMRI alcohol-cue reactivity task has a more established literature in youth who use alcohol; however, the findings have been mixed in terms of the neural effects of alcohol use [55, 70, 72, 92,93,94,95,96] and the potential to use this task in medication screening paradigms [78, 97]. We did not see an effect of CBD on neural reactivity to alcohol cues or the contrast of alcohol – non-alcohol beverage cues using both a whole-brain approach and an a priori ROI approach focused on brain regions known to underpin AUD. Our null fMRI alcohol cue-reactivity findings and self-reported alcohol craving via the AUQ contradict the above mentioned Zimmermann et al. trial [60]. It is possible that the images presented in the alcohol-cue reactivity task do not elicit strong enough craving or appetitive responses in youth with AUD, contributing the null findings. Future studies may want to investigate these effects in a larger sample that covers a broader age range, explores different doses of CBD, and employs stimuli that may be more relevant for modern day youth.

The physiological response (HRV and SCR) during the olfactory cue-reactivity task was not impacted by CBD administration. This may be due to the lack of task effects for HRV and SCR, where there were no physiological differences noted between baseline, water, apple juice, or alcohol exposure. Even though the task presented in this study has been conducted in youth populations previously [56], and the task was individualized to the participant based on their preferred alcoholic beverage, our findings suggests that the olfactory cues presented were not salient enough to illicit a physiological response in youth with AUD. Tasks with multi-system or more salient cues, such as taste [98], may be better situated to measure changes in physiological responses due to medication. Given the sample included youth under the legal drinking age for the US, we were not able to incorporate taste cues, which might be the most salient cues for this age. Taste cues have been associated with increased craving, desire to drink, reactivity to olfactory cues, and neural activation [99, 100]. Interestingly, we did see cue-induced changes in self-reported acute alcohol craving via the AUQ, where alcohol cues were related to higher craving. Previous work has also shown increases in self-reported craving after olfactory exposure to beer cues in adolescents with AUD [101]. It is unclear if this is a true response or a demand characteristic [102, 103]. Adaptations to the olfactory cue-reactivity task should be considered before utilizing it in future youth AUD studies.

The findings presented need to be interpreted within the strengths and weakness of this study. In terms of strengths, this study was a rigorously designed within-subjects crossover design that allows for stronger statistical power. We employed a strict time-lock protocol to collect data when CBD’s bioavailability should have been peaking [52, 69]. We carefully chose the acute 600 mg dose of CBD based on existing literature showing neural and clinical effects in a variety of populations, including schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder, anxiety, and healthy control groups [20, 51, 63, 67, 68, 104,105,106,107,108,109]. We used up-to-date acquisition, processing, and analysis techniques (e.g., Osprey) that allowed for thorough visual and data-driven quality checks for all data. Consequently, our data were very high quality, and few participants had to be excluded from analyses (with exception of the olfactory cue-reactivity task SCR outcomes). We also used multi-modal methods that allowed for the investigation of several neural, biological, and behavioral factors that influence AUD symptomology. Importantly, the safety profile of CBD in this study was excellent, with no reported adverse events related to the medication. This will be important for future studies utilizing chronic dosing of CBD.

In terms of weaknesses, there is limited research in this area which made concluding power and sample size difficult. We based our power analysis on extant research that administered an acute dose 600 mg of CBD in samples that were clinically and demographically different from the present study (e.g., schizophrenia for 1H-MRS) [51] or used different fMRI procedures (e.g., resting state or task based) [20, 51, 67, 68, 104,105,106,107,108,109], which may inform the null findings. The data presented on each outcome can now be used to calculate well-powered sample sizes in youth with AUD. Unlike the Zimmermann CBD study [60], we did not quantify blood CBD levels to confirm bioavailability. This may be critical in future CBD research, as other studies have reported high levels of inter-participant variability in CBD plasma levels which were not related to physical characteristics [60]. We did carefully plan and time-lock the protocol to peak CBD time window according to existing data [52, 69] and used a standardized high-fat snack in maximize bioavailability of CBD [110]; however, confirmation of blood CBD levels would be ideal. Future work will benefit from a dose-response study in youth with AUD. We also focused on an acute dose (600 mg) of CBD rather than longitudinal dosing, which might be critical in this age range to detect substance use or other clinically meaningful effects [11, 111]. Additionally, the cue-reactivity tasks used may present ineffective cues for youth, who may be more reactive to mood enhancement, social cues, or environmental stimuli related to alcohol [103]. The fMRI alcohol cue-reactivity task relies on standard images that may not induce craving or appetitive responses in youth, limiting the ability to observe medication effects. Indeed, previous work from our group using this task has shown minimal differences in neural reactivity between youth who use alcohol heavily and a sub-group with AUD compared to controls [70], while other work has shown neural reactivity using this task in youth [72]. The olfactory cues were also not salient enough to induce physiological changes between beverage types; however, we did see increases in self-reported craving that were not impacted by CBD. Taste may be a more impactful cue [98,99,100], so future studies should try to power their samples to allow for taste reactivity assessment in individuals who can legally consume alcohol. Finally, our sample was very homogenous with high representation of white females which may limit the generalizability to more diverse youth or those with higher severity of AUD. This warrants further research.

Conclusion

This medication screening study was a first attempt at understanding the acute effects of CBD, compared to placebo, in non-treatment seeking youth with AUD. While we employed a variety of methods, CBD was not related to any neural, physiological, psychological, or behavioral change. These findings should not be interpreted as conclusive regarding of CBD’s potential therapeutic role within this population. Rather, longitudinal studies that incorporate biological markers of CBD absorption and studies designed to capture potential changes in substance use behaviors may provide critical additional insights in the overall effort to rigorously develop and evaluate candidate treatments for youth with AUD.

Data availability

All data are available through the NIAAA Data Archive.

References

Swendsen J, Burstein M, Case B, Conway KP, Dierker L, He J, et al. Use and abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs in US adolescents: Results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:390–8.

Kirkland AE, Gex KS, Bryant BE, Squeglia LM Treatment of Adolescents. Alcohol and Alcoholrelated Diseases: Springer; 2023. p. 309-28.

Jensen CD, Cushing CC, Aylward BS, Craig JT, Sorell DM, Steele RG. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing interventions for adolescent substance use behavior change: A meta-analytic review. J Consulting Clin Psychol. 2011;79:433–40.

Tripodi SJ, Bender K, Litschge C, Vaughn MG. Interventions for reducing adolescent alcohol abuse: A meta-analytic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:85–91.

Chung T, Maisto SA. Relapse to alcohol and other drug use in treated adolescents: Review and reconsideration of relapse as a change point in clinical course. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:149–61.

Tanner-Smith EE, Lipsey MW. Brief alcohol interventions for adolescents and young adults: A systematic meta-anlysis. J. Substance Abuse Treat. 2015;51:1–18.

Winters KC, Stinchfield RD, Opland E, Weller C, Latimer WW. The effectiveness of the Minnesota Model approach in the treatment of adolescent drug abusers. Addiction. 2000;95:601–12.

Squeglia LM, Fadus MC, McClure EA, Tomko RL, Gray KM. Pharmacological treatment of youth substance use disorders. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2019;29:559–72.

Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, Barbe RP, Birmaher B, Pincus HA, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007;297:1683–96.

Prud’homme M, Cata R, Jutras-Aswad D. Cannabidiol as an intervention for addictive behaviors: a systematic review of the evidence. Substance abuse: research and treatment. 2015;9:SART. S25081.

Nona CN, Hendershot CS, Le Foll B. Effects of cannabidiol on alcohol-related outcomes: A review of preclinical and human research. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2019;27:359.

Viudez‐Martínez A, García‐Gutiérrez MS, Fraguas‐Sánchez AI, Torres‐Suárez AI, Manzanares J. Effects of cannabidiol plus naltrexone on motivation and ethanol consumption. Br. J. pharmacology. 2018;175:3369–78.

Viudez‐Martínez A, García‐Gutiérrez MS, Navarrón CM, Morales‐Calero MI, Navarrete F, Torres‐Suárez AI, et al. Cannabidiol reduces ethanol consumption, motivation and relapse in mice. Addiction Biol. 2018;23:154–64.

Maccioni P, et al. Reducing effect of cannabidiol on alcohol self-administration in Sardinian alcohol-preferring rats. Cannab Cannab Res. 2022;7:161–69.

Viudez‐Martínez A, García‐Gutiérrez MS, Manzanares J. Gender differences in the effects of cannabidiol on ethanol binge drinking in mice. Addiction Biol. 2020;25:e12765.

Gonzalez-Cuevas G, Martin-Fardon R, Kerr TM, Stouffer DG, Parsons LH, Hammell DC, et al. Unique treatment potential of cannabidiol for the prevention of relapse to drug use: preclinical proof of principle. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:2036–45.

Hamelink C, Hampson A, Wink DA, Eiden LE, Eskay RL. Comparison of cannabidiol, antioxidants, and diuretics in reversing binge ethanol-induced neurotoxicity. J. Pharmacology Exp. Therapeutics. 2005;314:780–8.

Liput DJ, Hammell DC, Stinchcomb AL, Nixon K. Transdermal delivery of cannabidiol attenuates binge alcohol-induced neurodegeneration in a rodent model of an alcohol use disorder. Pharmacology Biochem. Behav. 2013;111:120–7.

ElSohly MA, Radwan MM, Gul W, Chandra S, Galal A. Phytochemistry of Cannabis sativa L. Phytocannabinoids. 2017:1-36.

Bhattacharyya S, Morrison PD, Fusar-Poli P, Martin-Santos R, Borgwardt S, Winton-Brown T, et al. Opposite effects of Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol on human brain function and psychopathology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:764–74.

Organization WH. Cannabidiol (CBD) Critical Review Report. Geneva Dependence ECoD; 2018.

O’Callaghan FV, Jordan N. Postmodern values, attitudes and the use of complementary medicine. Complementary therapies Med. 2003;11:28–32.

Balog-Way DH, Evensen D, Löfstedt RE Pharmaceutical benefit–risk perception and age differences in the USA and Germany. Drug. Saf. 2020;10.

Freeman T, Hindocha C, Baio G, DC N, editors. Cannabidiol for the treatment of cannabis use disorder: Phase IIa double-blind placebo-controlled randomised adaptive Bayesian dose-finding trial. Int J Behav Med. 2021. Springer, New York, United States.

Karoly H, Mueller R, Andrade C, Hutchison K. THC and CBD effects on alcohol use among alcohol and cannabis co-users. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2021.

Laprairie R, Bagher A, Kelly M, Denovan‐Wright E. Cannabidiol is a negative allosteric modulator of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Br. J. pharmacology. 2015;172:4790–805.

Tham M, et al. Allosteric and orthosteric pharmacology of cannabidiol and cannabidiol‐dimethylheptyl at the type 1 and type 2 cannabinoid receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019;176:1455–69.

Thomas A, Baillie G, Phillips A, Razdan R, Ross RA, Pertwee RG. Cannabidiol displays unexpectedly high potency as an antagonist of CB1 and CB2 receptor agonists in vitro. Br. J. pharmacology. 2007;150:613–23.

Pertwee R. The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: Δ9‐tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and Δ9‐tetrahydrocannabivarin. Br. J. pharmacology. 2008;153:199–215.

Elmes MW, Kaczocha M, Berger WT, Leung K, Ralph BP, Wang L, et al. Fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs) are intracellular carriers for Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:8711–21.

Ligresti A, De Petrocellis L, Di Marzo V. From phytocannabinoids to cannabinoid receptors and endocannabinoids: pleiotropic physiological and pathological roles through complex pharmacology. Physiological Rev. 2016;96:1593–659.

Colombo G, Serra S, Vacca G, Carai MA, Gessa GL. Endocannabinoid system and alcohol addiction: pharmacological studies. Pharmacology Biochem. Behav. 2005;81:369–80.

Manzanares J, Cabañero D, Puente N, García-Gutiérrez MS, Grandes P, Maldonado R. Role of the endocannabinoid system in drug addiction. Biochemical pharmacology. 2018;157:108–21.

Ishiguro H, Iwasaki S, Teasenfitz L, Higuchi S, Horiuchi Y, Saito T, et al. Involvement of cannabinoid CB2 receptor in alcohol preference in mice and alcoholism in humans. pharmacogenomics J. 2007;7:380–5.

López-Moreno JA, González-Cuevas G, de Fonseca FR, Navarro M. Long-lasting increase of alcohol relapse by the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 during alcohol deprivation. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:8245–52.

Gobira PH, Vilela LR, Gonçalves BD, Santos RP, de Oliveira AC, Vieira LB, et al. Cannabidiol, a Cannabis sativa constituent, inhibits cocaine-induced seizures in mice: possible role of the mTOR pathway and reduction in glutamate release. Neurotoxicology. 2015;50:116–21.

Linge R, Jiménez-Sánchez L, Campa L, Pilar-Cuéllar F, Vidal R, Pazos A, et al. Cannabidiol induces rapid-acting antidepressant-like effects and enhances cortical 5-HT/glutamate neurotransmission: role of 5-HT1A receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2016;103:16–26.

Bakas T, Van Nieuwenhuijzen P, Devenish S, McGregor I, Arnold J, Chebib M. The direct actions of cannabidiol and 2-arachidonoyl glycerol at GABAA receptors. Pharmacol. Res. 2017;119:358–70.

Pandolfo P, Silveirinha V, dos Santos-Rodrigues A, Venance L, Ledent C, Takahashi RN, et al. Cannabinoids inhibit the synaptic uptake of adenosine and dopamine in the rat and mouse striatum. Eur. J. pharmacology. 2011;655:38–45.

Sales AJ, Crestani CC, Guimarães FS, Joca SR. Antidepressant-like effect induced by Cannabidiol is dependent on brain serotonin levels. Prog. Neuro-psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;86:255–61.

Abame MA, He Y, Wu S, Xie Z, Zhang J, Gong X, et al. Chronic administration of synthetic cannabidiol induces antidepressant effects involving modulation of serotonin and noradrenaline levels in the hippocampus. Neurosci. Lett. 2021;744:135594.

Kathmann M, Flau K, Redmer A, Tränkle C, Schlicker E. Cannabidiol is an allosteric modulator at muand delta-opioid receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. pharmacology. 2006;372:354–61.

Karoly HC, Mueller RL, Bidwell LC, Hutchison KE. Cannabinoids and the microbiota–gut–brain axis: emerging effects of cannabidiol and potential applications to alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism: Clin. Exp. Res. 2020;44:340–53.

Seyhan AA. Lost in translation: the valley of death across preclinical and clinical divide–identification of problems and overcoming obstacles. Transl. Med. Commun. 2019;4:1–19.

Ray LA, Bujarski S, Roche DJO, Magill M. Overcoming the “Valley of Death” in medications development for alcohol use disorder. Alcoholism: Clin. Exp. Res. 2018;42:1612–22.

Grodin EN, Ray LA. The use of functional magnetic resonance imaging to test pharmacotherapies for alcohol use disorder: A systematic review. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2019;43:2038–56.

Kirkland AE, Browning BD, Green R, Leggio L, Meyerhoff DJ, Squeglia LM. Brain metabolite alterations related to alcohol use: a meta-analysis of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:3223–36.

Chen T, Tan H, Lei H, Su H, Zhao M. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in substance use disorder: Recent advances and future clinical applications. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2020;63:170101.

Kalivas PW, Volkow ND. New medications for drug addiction hiding in glutamatergic neuroplasticity. Mol. Psychiatry. 2011;16:974–86.

Roberts-Wolfe DJ, Kalivas PW. Glutamate transporter GLT-1 as a therapeutic target for substance use disorders. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug. Targets. 2015;14:745–56.

O’Neill A, Annibale L, Blest-Hopley G, Wilson R, Giampietro V, Bhattacharyya S. Cannabidiol modulation of hippocampal glutamate in early psychosis. J. Psychopharmacol. 2021;35:814–22.

Pretzsch CM, Freyberg J, Voinescu B, Lythgoe D, Horder J, Mendez MA, et al. Effects of cannabidiol on brain excitation and inhibition systems; a randomised placebo-controlled single dose trial during magnetic resonance spectroscopy in adults with and without autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:1398–405.

Zilverstand A, Huang AS, Alia-Klein N, Goldstein RZ. Neuroimaging impaired response inhibition and salience attribution in human drug addiction: A systematic review. Neuron. 2018;98:886–903.

Miranda R, Ray L, Blanchard A, Reynolds EK, Monti PM, Chun T, et al. Effects of naltrexone on adolescent alcohol cue reactivity and sensitivity: an initial randomized trial. Addiction Biol. 2014;19:941–54.

Courtney KE, Schacht JP, Hutchison K, Roche DJ, Ray LA. Neural substrates of cue reactivity: association with treatment outcomes and relapse. Addiction Biol. 2016;21:3–22.

Thomas SE, Drobes DJ, Deas D. Alcohol cue reactivity in alcohol-dependent adolescents. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:354–60.

Hermann D, Weber-Fahr W, Sartorius A, Hoerst M, Frischknecht U, Tunc-Skarka N, et al. Translational magnetic resonance spectroscopy reveals excessive central glutamate levels during alcohol withdrawal in humans and rats. Biol. psychiatry. 2012;71:1015–21.

Liang J, Olsen RW. Alcohol use disorders and current pharmacological therapies: the role of GABA A receptors. Acta Pharmacologica Sin. 2014;35:981–93.

Mon A, Durazzo TC, Meyerhoff DJ. Glutamate, GABA, and other cortical metabolite concentrations during early abstinence from alcohol and their associations with neurocognitive changes. Drug. alcohol. dependence. 2012;125:27–36.

Zimmermann S, Teetzmann A, Baeßler J, Schreckenberger L, Zaiser J, Pfisterer M, et al. Acute cannabidiol administration reduces alcohol craving and cue-induced nucleus accumbens activation in individuals with alcohol use disorder: the double-blind randomized controlled ICONIC trial. Mol. Psychiatry. 2024; 1–8.

Hurd YL, Spriggs S, Alishayev J, Winkel G, Gurgov K, Kudrich C, et al. Cannabidiol for the reduction of cue-induced craving and anxiety in drug-abstinent individuals with heroin use disorder: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2019;176:911–22.

Hurzeler T, Logge W, Watt J, McGregor IS, Suraev A, Haber PS, et al. Cannabidiol alters psychophysiological, craving and anxiety responses in an alcohol cue reactivity task: A cross‐over randomized controlled trial. Alcohol: Clin. Exp. Res. 2025;49:448–59.

Kirkland AE, Fadus MC, Gruber SA, Gray KM, Wilens TE, Squeglia LM. A scoping review of the use of cannabidiol in psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2022;308:114347.

Davis CN, Markowitz JS, Squeglia LM, Ellingson JM, McRae-Clark AL, Gray KM, et al. Evidence for sex differences in the impact of cytochrome P450 genotypes on early subjective effects of cannabis. Addictive Behav. 2024;153:107996.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33.

Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH, Shytle RD, Janavs J, Bannon Y, Rogers JE, et al. Reliability and validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID). J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2010;71:313–26.

O’Neill A, Wilson R, Blest-Hopley G, Annibale L, Colizzi M, Brammer M, et al. Normalization of mediotemporal and prefrontal activity, and mediotemporal-striatal connectivity, may underlie antipsychotic effects of cannabidiol in psychosis. Psychol Med. 2021;51:596–606.

Pretzsch CM, Voinescu B, Mendez MA, Wichers R, Ajram L, Ivin G, et al. The effect of cannabidiol (CBD) on low-frequency activity and functional connectivity in the brain of adults with and without autism spectrum disorder (ASD). J. Psychopharmacol. 2019;33:1141–8.

Agurell S, Carlsson S, Lindgren J, Ohlsson A, Gillespie H, Hollister L. Interactions of Δ 1 1-tetrahydrocannabinol with cannabinol and cannabidiol following oral administration in man. Assay of cannabinol and cannabidiol by mass fragmentographywith cannabinol and cannabidiol following oral administration in man. Assay. cannabinol cannabidiol mass. fragmentography. Experientia. 1981;37:1090–2.

Kirkland AE, Green R, Browning BD, Aghamoosa S, Meyerhoff DJ, Ferguson PL, et al. Multi-modal neuroimaging reveals differences in alcohol-cue reactivity but not neurometabolite concentrations in adolescents who drink alcohol. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2024:111254.

Kirkland AE, Browning BD, Green R, Liu H, Maralit AM, Ferguson PL, et al. N-acetylcysteine does not alter neurometabolite levels in non-treatment seeking adolescents who use alcohol heavily: A preliminary randomized clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2023:1-10.

Courtney KE, Li I, Tapert SF. The effect of alcohol use on neuroimaging correlates of cognitive and emotional processing in human adolescence. Neuropsychology. 2019;33:781.

McCartney D, Kevin RC, Suraev AS, Sahinovic A, Doohan PT, Bedoya‐Pérez MA, et al. How long does a single oral dose of cannabidiol persist in plasma? Findings from three clinical trials. Drug. Test. Anal. 2023;15:334–44.

Hawksworth G, McArdle K. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of cannabinoids. In: The Medicinal Uses of Cannabis and Cannabinoids (Guy GW, Whittle BA, Robson PJ, eds.). Pharmaceutical Press: London, 2004, pp. 205–28.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009;42:377–81.

Lin A, Andronesi O, Bogner W, Choi IY, Coello E, Cudalbu C, et al. Minimum reporting standards for in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRSinMRS): experts’ consensus recommendations. NMR Biomedicine. 2021;34:e4484.

Schacht JP, Anton RF, Myrick H. Functional neuroimaging studies of alcohol cue reactivity: a quantitative meta‐analysis and systematic review. Addiction Biol. 2013;18:121–33.

Green R, Kirkland AE, Browning BD, Ferguson PL, Gray KM, Squeglia LM. Effect of N‐acetylcysteine on neural alcohol cue reactivity and craving in adolescents who drink heavily: A preliminary randomized clinical trial. Alcohol: Clin. Exp. Res. 2024;48:1772–83.

Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back. Measuring alcohol consumption: Springer; 1992. p. 41-72.

Tomko RL, Gray KM, Oppenheimer SR, Wahlquist AE, McClure EA. Using REDCap for ambulatory assessment: Implementation in a clinical trial for smoking cessation to augment in-person data collection. Am. J. drug. alcohol. abuse. 2019;45:26–41.

Carpenter RW, Squeglia LM, Emery NN, McClure EA, Gray KM, Miranda R Jr, et al. Making pharmacotherapy trials for substance use disorder more efficient: Leveraging real-world data capture to maximize power and expedite the medication development pipeline. Drug. alcohol. dependence. 2020;209:107897.

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015;67:1–48.

Lüdecke D, Ben-Shachar MS, Patil I, Waggoner P, Makowski D. Performance: An R package for assessment, comparison and testing of statistical models. J. Open. Source Softw. 2021;6:3139.

Hartig F. DHARMa: residual diagnostics for hierarchical (multi-level/mixed) regression models. R Packag version 020, 2018.

Zeileis A, Hothorn T. Diagnostic checking in regression relationships. Vol. 2. 2002: na.

Zeileis A, Köll S, Graham N. Various versatile variances: an object-oriented implementation of clustered covariances in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2020;95:1–36.

Zeileis A. Object-oriented computation of sandwich estimators. J. Stat. Softw. 2006;16:1–16.

Zeileis A. Econometric computing with HC and HAC covariance matrix estimators. 2004.

Kunzetsova A, Brockhoff P, Christensen R. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effect models. J. Stat. Softw. 2017;82:1–26.

Hurzeler T, Logge W, Watt J, McGregor I, Suraev A, Haber PS, et al. Cannabidiol attenuates precuneus activation during appetitive cue exposure in individuals with alcohol use disorder. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2025; 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-025-01983-4.

Silveri MM, Cohen‐Gilbert J, Crowley DJ, Rosso IM, Jensen JE, Sneider JT. Altered anterior cingulate neurochemistry in emerging adult binge drinkers with a history of alcohol‐induced blackouts. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2014;38:969–79.

Tapert SF, Brown GG, Baratta MV, Brown SA. fMRI BOLD response to alcohol stimuli in alcohol dependent young women. Addict. Behav. 2004;29:33–50.

Tapert SF, Cheung EH, Brown GG, Frank LR, Paulus MP, Schweinsburg AD, et al. Neural response to alcohol stimuli in adolescents with alcohol use disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2003;60:727–35.

Brumback T, Squeglia LM, Jacobus J, Pulido C, Tapert SF, Brown SA. Adolescent heavy drinkers’ amplified brain responses to alcohol cues decrease over one month of abstinence. Addict. Behav. 2015;46:45–52.

Nguyen-Louie TT, Courtney KE, Squeglia LM, Bagot K, Eberson S, Migliorini R, et al. Prospective changes in neural alcohol cue reactivity in at-risk adolescents. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018;12:931–41.

Dager AD, Anderson BM, Stevens MC, Pulido C, Rosen R, Jiantonio‐Kelly RE, et al. Influence of alcohol use and family history of alcoholism on neural response to alcohol cues in college drinkers. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2013;37:E161–E171.

Sangchooli A, Zare-Bidoky M, Fathi Jouzdani A, Schacht J, Bjork JM, Claus ED, et al. Parameter space and potential for biomarker development in 25 Years of fMRI drug cue reactivity: a systematic review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81:414–25.

Thibodeau M, Pickering GJ. The role of taste in alcohol preference, consumption and risk behavior. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019;59:676–92.

Courtney KE, Ghahremani DG, Ray LA. The effect of alcohol priming on neural markers of alcohol cuereactivity. Am. J. Drug. Alcohol. Abus. 2015;41:300–8.

Jasinska AJ, Stein EA, Kaiser J, Naumer MJ, Yalachkov Y. Factors modulating neural reactivity to drug cues in addiction: a survey of human neuroimaging studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014;38:1–16.

Cousijn J, Mies G, Runia N, Derksen M, Willuhn I, Lesscher H. The impact of age on olfactory alcohol cue‐reactivity: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study in adolescent and adult male drinkers. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2023;47:668–77.

Meredith LR, Burnette EM, Nieto SJ, Du H, Donato S, Grodin EN, et al. Testing pharmacotherapies for alcohol use disorder with cue exposure paradigms: A systematic review and quantitative synthesis of human laboratory trial methodology. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2023;47:1629–45.

Miranda R Jr, MacKillop J, Treloar H, Blanchard A, Tidey JW, Swift RM, et al. Biobehavioral mechanisms of topiramate’s effects on alcohol use: an investigation pairing laboratory and ecological momentary assessments. Addict. Biol. 2016;21:171–82.

Grimm O, Löffler M, Kamping S, Hartmann A, Rohleder C, Leweke M, et al. Probing the endocannabinoid system in healthy volunteers: Cannabidiol alters fronto-striatal resting-state connectivity. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28:841–9.

Davies C, Wilson R, Appiah-Kusi E, Blest-Hopley G, Brammer M, Perez J, et al. A single dose of cannabidiol modulates medial temporal and striatal function during fear processing in people at clinical high risk for psychosis. Transl. Psychiatry. 2020;10:1–12.

Winton-Brown TT, Allen P, Bhattacharrya S, Borgwardt SJ, Fusar-Poli P, Crippa JA, et al. Modulation of auditory and visual processing by delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol: an FMRI study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1340–8.

Borgwardt SJ, Allen P, Bhattacharyya S, Fusar-Poli P, Crippa JA, Seal ML, et al. Neural basis of Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol: effects during response inhibition. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;64:966–73.

Fusar-Poli P, Crippa JA, Bhattacharyya S, Borgwardt SJ, Allen P, Martin-Santos R, et al. Distinct effects of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol on neural activation during emotional processing. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2009;66:95–105.

Bhattacharyya S, Crippa JA, Allen P, Martin-Santos R, Borgwardt S, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Induction of psychosis byδ9-tetrahydrocannabinol reflects modulation of prefrontal and striatal function during attentional salience processing. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2012;69:27–36.

Taylor L, Gidal B, Blakey G, Tayo B, Morrison G. A phase I, randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled, single ascending dose, multiple dose, and food effect trial of the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of highly purified cannabidiol in healthy subjects. CNS Drugs. 2018;32:1053–67.

Turna J, Syan SK, Frey BN, Rush B, Costello MJ, Weiss M, et al. Cannabidiol as a novel candidate alcohol use disorder pharmacotherapy: a systematic review. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2019;43:550–63.

Funding

This project was funded by NIAAA (R21AA030114). Dr. Kirkland is funded through the NIAAA K01 (K01AA031745), Drs. Brittney Browning and Lindsay Meredith are funded through the NIDA T32 (DA007288), and Dr. Lindsay Squeglia is funded through an NIAAA K24 (AA031052). This project was supported, in part, by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Grant Number UL1 TR001450. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. REDCap at SCTR is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Grant Number UL1 TR001450. Open access funding provided by the Carolinas Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made significant contributions to this work. The project was conceived by LMS, KMG, RMT, AEK. LMS received funding for this project. AEK, BDB, CH, ER acquired data. AEK and LRM analyzed the data and conducted the analyses. The manuscript was written by AEK, BDB, LRM, and LMS, and revised by all authors. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Kevin Gray reports having received consultation fees from Achieve Life Sciences and Indivior, and research support from Aelis Farma. All other authors report no potential competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kirkland, A.E., Browning, B.D., Meredith, L.R. et al. The neural and psychophysiological effects of cannabidiol in youth with alcohol use disorder: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacol. 50, 1482–1492 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-025-02141-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-025-02141-z

This article is cited by

-

High hopes, hard realities: cannabidiol shows no acute effects in youth with alcohol use disorder

Neuropsychopharmacology (2025)