Abstract

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a severe mental disorder, characterized by episodes of mania and depression. The longitudinal neurobiological impact of BD episodes on brain structure remains largely unknown. In 124 age-sex-matched participants (62 BD patients; 62 healthy controls; HCs), aged 20-62 years, we investigated the longitudinal relationship between BD episodes and whole-brain gray matter volume (GMV) changes (3 Tesla MRI) during a two-year interval, using voxel-based morphometry in SPM12/CAT12. We compared GMV trajectories between BD patients with at least one depressive or manic episode during the two-year interval, BD patients without an episode, and HCs. We explored associations between GMV changes and clinical variables, like the number and duration of depressive or manic episodes both during the two-year interval and before baseline assessment. BD patients showed GMV increases in the right exterior cerebellum with an increasing number of depressive episodes during the two-year interval. BD patients without recurrence showed GMV reductions in this area, relative to BD patients with recurrence and HCs. Notably, BD patients without recurrence exhibited greater GMV reductions during the two-year interval, the longer they had spent in a manic episode before baseline. Our findings underscore the dynamic nature of brain changes in BD. GMV increases in BD patients with recurrence may be due to acute neuroinflammatory mechanisms including glial cell proliferation, whereas GMV reductions in BD patients without recurrence may result from abnormal synaptic refinement or pruning, as a consequence of past neuroinflammation during BD episodes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a complex mental disorder characterized by episodes of mania and depression, affecting ~1% of the global population [1]. Such episodes disrupt social and occupational functioning [2] and may alter brain structure [3].

Cross-sectional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies show that BD patients have decreased gray matter volumes (GMVs) in the insula, thalamus, anterior cingulate cortex, fusiform gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, and inferior, middle, and superior frontal gyri, and increased GMVs in the putamen, precuneus, and posterior cingulate cortex, compared to healthy controls (HCs), according to recent meta-analyses [4,5,6,7]. Longitudinal MRI research extends these findings by demonstrating progressive GMV reductions over time in the frontal and temporal lobes and anterior cingulate cortex, compared to HCs [3, 8]. Longitudinal studies are crucial to determine whether GMV changes are a precursor to or a consequence of BD. However, longitudinal evidence from BD patients is scarce, inconsistent, and limited by small sample sizes, with different brain regions being affected, ranging from GMV decreases to increases [9], and in some cases no significant changes at all compared to HCs [10].

This inconsistency in brain structural findings may be due to several factors such as aging, genetics, pharmacological treatment, and the number and timing of mood episodes relative to scanning [3, 9]. Within the neuroprogression framework [11], particularly, mood episodes exert cumulative effects on brain structure through mechanisms like low-grade inflammatory processes [9], as indicated by markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) [12, 13]. Low-grade peripheral inflammation may lead to neuroinflammation, excitotoxicity, and oxidative stress [14], particularly in areas critical for emotion regulation [14,15,16], which may sensitize the system to future stressors, triggering more frequent BD episodes [17], and leading to more GMV changes over time [14, 15]. During remission, these brain changes stabilize, leading to fewer GMV changes over time, similar to the age-related decline observed in HCs [9, 17]. These findings suggest a dynamic interplay between episodes, disease progression, and recovery in influencing GMV trajectories in BD.

Recent longitudinal studies have begun to explore the impact of recurrent BD episodes on brain structural changes over time. First-episode BD patients with at least one depressive or manic episode during the scanning interval showed GMV reductions in frontal, temporal, and parietal regions, compared to those without an episode and HCs [17]. BD patients with manic episodes during the interval showed gray matter decreases in frontal regions compared to those without an episode [18] and HCs [19]. In contrast, BD patients with an increasing number of depressive episodes showed gray matter increases in the cingulate gyrus, thalamus, and lenticular nuclei [20], alongside decreases in the temporal lobe [21, 22]. Notably, BD patients with an increasing number of manic episodes during the interval showed gray matter decreases in the cerebellum [21], while gray matter increases in the cerebellum were observed with an increasing number of depressive episodes [20]. These findings suggest a dynamic interplay between the episode polarity and GMV changes, even within the same region.

However, these previous studies often did not compare brain structural changes in BD patients with recurrence to those without recurrence or HCs, nor did they explore the impact of episode type (manic vs. depressive), or considered patients’ baseline episode history on brain structural changes. Investigating these factors is crucial to determine, whether the observed brain changes during a longer interval (years) reflect adaptive versus maladaptive neurobiological responses to recurrent BD episodes. By comparing GMV changes in BD patients with recurrence to those without recurrence and HCs, we could determine whether the observed brain changes resulted from BD episodes.

Therefore, for the first time, we elucidate GMV changes in groups of BD patients with and without a depressive or manic episode and HCs during a two-year follow-up interval within the neuroprogression framework. We hypothesized that BD patients with an episode during the two-year interval would show GMV decreases associated with manic episodes or GMV increases associated with depressive episodes, consistent with the existing literature. We also hypothesized that BD patients without an episode would not show such GMV changes during the two-year interval, similar to HCs.

Furthermore, to elucidate the effects of previous mood episodes – i.e., those that occurred before our baseline assessment – on brain changes during the two-year interval, we explored the relationships between GMV changes during the two-year interval and the number and duration of depressive or manic episodes prior to baseline. We also explored potential predictive associations between baseline CRP levels and GMV changes during the two-year interval, to better understand the neuroimmunology behind the observed GMV changes. Lastly, we explored the influence of potential confounders on GMV changes, including the number and duration of hospitalizations during the two-year interval, changes in symptom severity, global psycho-social functioning, familial genetic risk, comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, and medication use.

Materials and methods

Participants

124 age-sex-matched participants (n = 62 HC; n = 62 BD) were included in this analysis from the ongoing Marburg–Münster Affective Disorder Cohort Study (MACS) [23], which is part of the FOR2107 consortium investigating the neurobiology of major psychiatric disorders. All available data relevant to our research question were included in this analysis. Some of this data was previously analyzed in cross-sectional studies investigating GMV alterations in BD patients relative to HCs [24,25,26,27]. All participants underwent T1-weighted MRI scans and clinical assessments at both baseline (T1) and follow-up (T2) time points, approximately two years apart (mean = 2.18 years, SD = 0.26, range: 1.96–3.28 years). Assessments were conducted at the University of Marburg and the University of Münster in Germany. Inclusion criteria required that participants were between 18 and 65 years of age at baseline (T1) time point. Exclusion criteria were a history of neurological or general medical conditions, substance dependence, and verbal IQ ≤ 80. HCs were further excluded if they met the criteria for current or past mental disorders as per Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID-I) [28], or if they had a lifetime intake of psychotropic medication (for details, see ref. [23]). To minimize potential overlaps in brain structural variance between BD patients and HCs, HCs were further excluded with a positive family history of BD and those with subsyndromal depressive or manic symptoms during the two-year follow-up interval (T2-T1) (Supplementary Materials and Methods S1). To ensure a balanced comparison between groups, HCs were matched 1:1 to BD patients by age and sex using the MatchIt package in R (version 4.3.1) [29], to avoid any confounding effects from these variables [30, 31]. This study was approved by the ethics committees of the medical faculties at the University of Marburg (AZ: 07/14) and the University of Münster (AZ: 2014-422-b-S) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants provided written informed consent and received financial compensation after receiving a full description of the study.

Assessment of clinical variables

Clinical variables were assessed through semi-structured interviews at both baseline (T1) and follow-up (T2) time points, including the course of illness (number and duration of depressive or manic episodes, number and duration of hospitalizations), current remission status (partially or fully remitted, according to SCID-I criteria), psychopathology (17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HAM-D], Young Mania Rating Scale [YMRS]) [32, 33], global psycho-social functioning (Global Assessment of Functioning; GAF) [34], familial risk (first-degree relative had been treated for BD, or treated for major depressive disorder [MDD], schizophrenia [SCZ], or schizoaffective disorder [SZA], considered together), body mass index (BMI), and current medication use, amongst others. Descriptive statistics of the study participants are presented in Table 1.

MRI acquisition and pre-processing

MRI acquisition

MRI data were acquired at both baseline (T1) and follow-up (T2) time points using a 3 Tesla MRI scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with standardized pulse sequence parameters and extensive quality assurance protocols [35]. Details on acquisition parameters are provided in Supplementary Materials and Methods S2.

MRI preprocessing

T1-weighted scans were preprocessed using the longitudinal pipeline of the CAT12 toolbox (v1742; Structural Brain Mapping Group, Jena, Germany) in SPM12 (Institute of Neurology, London, UK) running under MATLAB (vR2017a, The MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts, USA). Default preprocessing steps included realignment, bias correction, tissue classification, and spatial normalization using the Geodesic Shooting template. Images were segmented into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid, and smoothed with an 8 mm FWHM Gaussian kernel. Total intracranial volume (TIV) was calculated, and data were normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space. Individual quality control included visual inspection and outlier identification using the check homogeneity function in CAT12.

Harmonization of imaging data

Imaging data from two sites (Marburg and Münster) and two body coil changes in Marburg were harmonized using the ComBat tool (v1.0.1) in MATLAB R2017a to correct for site- and scanner-related variations while preserving biological variability in the data (Supplementary Materials and Methods S3).

Statistical analyses

Whole-brain analyses for longitudinal data

To investigate the effects of recurrent episodes in BD patients and GMV changes over time, and to compare these GMV changes with BD patients without episodes and HCs, we performed a 3 × 2 repeated measures Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) using the flexible factorial design in SPM12/CAT12. Subject, scanning time point (baseline [T1] and follow-up [T2]), and group (BD recurrence, BD non-recurrence, HCs) were included as main factors in the model. Age, sex, and interscan interval (time in days between baseline [T1] and follow-up [T2] scans) were included as covariates of no interest at follow-up (T2) time point, and set to zero at baseline (T1), to account for their known association with BD recurrences and GMV changes [30, 31]; TIV was not included as a covariate because each subject served as their own control. We applied a threshold of 0.1 to the absolute gray matter values as recommended by the CAT12 manual (https://neuro-jena.github.io/cat12-help/#stat_options). Cluster-level significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed), with an initial cluster-forming threshold of p < 0.001, family-wise error (FWE) corrected for multiple comparisons. Weighted means of significant cluster values were extracted using the eigenvariate function in SPM as proxies for GMV, for further visualization and statistical analyses in Jamovi software (version 2.3.28) [36].

Exploratory and control analyses for longitudinal data

Different sets of exploratory and control analyses were performed to investigate factors associated with longitudinal GMV changes. First, to investigate the impact of BD episodes on GMV changes, we employed partial Pearson correlations (or Spearman’s rho for non-normal data) to assess relationships between the cluster value changes and the number and duration of depressive or manic episodes during the two-year interval (T2-T1). Second, to identify predictive indicators of different GMV trajectories between BD recurrence groups, we examined the associations between the number and duration of depressive or manic episodes prior to baseline (T1) and cluster value changes during the two-year interval (T2-T1). Third, we examined the predictive role of baseline (T1) high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) on cluster value changes during the two-year interval (T2-T1) [37], considering the potential relationship between low-grade inflammation and brain structural changes associated with BD (Supplementary Materials and Methods S4) [14, 15]. Fourth, to assess the influence of potential confounders, we also explored the relationships between cluster value changes and variables related to disease course and severity, including the number and duration of hospitalizations [38], as well as changes in HAM-D, YMRS, GAF scores [27], and BMI [39] between baseline (T1) and follow-up (T2) in BD patients. Fifth, using ANCOVAs, we explored the influence of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses (anxiety disorder, eating disorder, alcohol abuse, cannabis abuse), remission status (according to SCID-I), familial risk (having a first-degree relative with BD, or with MDD, SCZ, or SZA considered together) on cluster value changes. Sixth, using ANCOVAs, we also explored the influence of medication use (antipsychotic, anticonvulsant, antidepressant, lithium) [9], and, seventh, medication load (using Medication load index, Sackeim scores, and chlorpromazine equivalents [CPZ]) [40,41,42,43].

Each set of analyses was performed at a significance level of p < 0.05 (two-tailed), Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons. To account for the variation in the duration between scans, variables related to events occurring during the two-year interval (T2-T1), like the number of depressive episodes, were divided by the interscan interval (in days). Data normality and homoscedasticity were assessed using Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s or Breusch–Pagan tests, and visually inspected using Q-Q- and residual plots for standardized and fitted residuals, respectively.

Whole-brain analyses for cross-sectional data

To explore cross-sectional associations between GMV and BD recurrence groups (BD recurrence, BD non-recurrence, HCs), ANCOVAs were performed using a full factorial design in SPM at both baseline (T1) and follow-up (T2) time points separately. These analyses assessed whether baseline (T1) GMV could predict future BD episodes or if such episodes influenced cross-sectional GMV changes (T2). Age, sex, and TIV were included as covariates. Cluster-level significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed), with an initial cluster-forming threshold of p < 0.001, FWE corrected for multiple comparisons.

Results

Longitudinal association between BD recurrence groups and GMV change

Whole-brain analyses

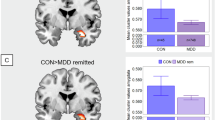

A 3 × 2 repeated measures ANCOVA with recurrence groups (BD recurrence, BD non-recurrence, HCs) as between-subjects factor and time (baseline, follow-up) as within-subjects factor revealed one significant cluster in the right exterior cerebellum, indicating differential GMV changes across the three groups over the two-year follow-up interval (T2-T1) (k = 517 voxels, x/y/z = 50/-60/-50, F2,118 = 12.25 FWE cluster-level, η2p = 0.172, p = 0.033; for results with TIV included as covariate in the model, see Supplementary Results S1).

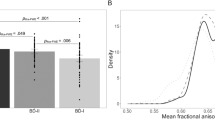

Post-hoc t-tests of whole-brain analysis

During the two-year (T2-T1) interval, BD patients without an episode during the two-year interval (T2-T1) showed significant GMV decreases in the right exterior cerebellum (t(118) = −4.24, Cohen’s d = 0.78, p < 0.001). Conversely, BD patients with a depressive or manic episode showed non-significant GMV increases (t(118) = 1.93, Cohen’s d = 0.35, p = 0.056), whereas HCs did not show significant GMV changes (t(118) = 0.72, Cohen’s d = 0.13, p = 0.471; see Fig. 1).

Exploratory correlation analyses in BD patients

The moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.35) of the observed non-significant GMV increase (T2-T1) in BD patients with recurrence prompted further investigation. So, we explored the associations between GMV changes in the right exterior cerebellum (T2-T1) and the number and duration of depressive or manic episodes during the two-year interval within the overall group of BD patients. Significant associations were found between the number of depressive episodes during the two-year interval (T2-T1) and GMV increases (T2-T1) in BD patients (rho(62) = 0.43, p < 0.001; see Fig. 2). No significant correlations were found between GMV changes (T2-T1) and the number of manic episodes or the duration of depressive or manic episodes during the two-year interval (T2-T1), after adjustment for multiple comparisons (Supplementary Table S1).

Exploratory correlation analyses in BD recurrence groups

In BD patients without an episode during the two-year interval (T2-T1), longer durations of manic episodes before baseline (T1) time point were associated with GMV decreases in the right exterior cerebellum during the two-year interval (T2-T1) (rho(20) = −0.59, p = 0.012). This association was not significant in BD patients with recurrence (rho(34) = 0.31, p = 0.087). The duration of depressive episodes or number of depressive or manic episodes prior to baseline (T1) did not significantly correlate with GMV changes (T2-T1) in either BD recurrence group (Supplementary Table S2).

Exploratory linear regression analyses in BD patients

Higher baseline (T1) hsCRP levels were associated with GMV increases within the right exterior cerebellum during the two-year interval (T2-T1) in BD patients (β = 0.35, t(24) = 2.13, p = 0.043; Supplementary Table S3), but not in HCs (β = 0.30, t(35) = 1.60, p = 0.119).

Control analyses in BD patients

GMV changes (T2-T1) in the right exterior cerebellum in BD patients were not associated with the number and duration of hospitalizations during the two-year interval (T2-T1) as well as changes in depressive symptoms (HAM-D), manic symptoms (YMRS), global functioning (GAF), or BMI between baseline (T1) and follow-up (T2) time points (Supplementary Table S4). Similarly, comorbid psychiatric diagnoses (anxiety disorder, eating disorder, alcohol abuse, cannabis abuse), familial risk (family history of BD, or family history of MDD, SCZ, or SZA considered together), remission status (Supplementary Table S5), and medication use or medication load did not significantly influence the observed GMV changes (Supplementary Tables S6 and S7).

Cross-sectional predictive and retrospective associations between BD recurrence groups and whole-brain GMV

No significant clusters emerged between recurrence groups and GMV at baseline (T1) and follow-up (T2) time points in the predictive and retrospective cross-sectional whole-brain analyses, respectively. This indicates that the observed GMV changes during the two-year interval (T2-T1) are likely a consequence of BD recurrences, rather than GMV alterations (T1) predicting future recurrences (T2-T1), or recurrences contributing to cross-sectional GMV alterations (T2).

Discussion

This two-year longitudinal study illuminates the impact of depressive and manic episodes on GMV changes in BD patients within the neuroprogression framework, revealing distinct patterns of GMV changes in the right exterior cerebellum associated with mood episodes. BD patients with depressive episodes during the two-year follow-up interval exhibited GMV increases in the right exterior cerebellum, whereas BD patients without an episode experienced GMV reductions in the same area, compared to HCs. Notably, the longer BD patients without an episode had spent in a manic episode before baseline, the larger were their GMV reductions in the right cerebellum during the two-year interval. Additionally, BD patients with higher baseline hsCRP levels, compared to those with lower levels, experienced more pronounced GMV increases in the right exterior cerebellum. Importantly, all associations were independent of the number and duration of hospitalizations during the two-year interval, changes in symptom severity or global functioning between baseline and follow-up, as well as familial genetic risk, comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, remission status, and medication.

Together our findings indicate a U-shaped trajectory of brain changes during the two-year interval (T2-T1) in the right exterior cerebellum in BD patients, associated with the longitudinal pattern of mood episodes. This trajectory is characterized by GMV increases during acute phases of depression and GMV decreases during periods of remission. The observed GMV decreases during remission are further intensified by past manic – but not, or to a lesser degree – past depressive episodes. The GMV increases during and/or shortly after acute depressive episodes aligned with the observed elevated baseline (T1) hsCRP levels in BD patients, suggesting an increased vulnerability of the brain to low-grade peripheral inflammation, which is linked to neuroinflammation [14, 15]. Such inflammatory processes may contribute to the observed GMV increases [44, 45], potentially through mechanisms like cellular swelling and recruitment of glial cells, particularly of microglia and astrocytes [45,46,47,48,49], to meet the heightened metabolic demands for maintaining brain health [50, 51]. During periods of remission, particularly in BD patients without recurrence, this glial cell proliferation may lead to maladaptive processes such as abnormal synaptic refinement or pruning [52,53,54,55], which may result in GMV reductions [56, 57]. These findings may clarify some of the contradictory findings of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies that reported GMV increases, decreases, or no changes at all in BD patients relative to HCs [9], which likely depended on the timing of the MRI data acquisition relative to the individual phase of the disorder (acute vs. remitted, manic vs. depressive, time since last episode, and duration and polarity of previous episodes). Together, these findings align with the neuroprogression model of BD, in which repeated mood episodes exert dynamic and cumulative effects on brain structure over time [11, 58]. For a visual representation of trajectory patterns across the different groups and disorder phases, see Fig. 3.

This diagram illustrates a simplified model of structural GMV changes in BD patients in relation to the timing of manic and depressive episodes, based on the findings from our study. The diagram depicts six time points (A, B, C, D, E, F) to represent potential occurrences or absences of manic or depressive episodes, with A, B, D, and F as hypothetical time points, and C and E as our actually measured MRI baseline and two-year follow-up time points, respectively. By having taken an extensive clinical history, we know the clinical states and course of illness from each patient during the times of A, B, and D. The trajectory of HCs is shown in green, individual BD patient trajectories in light blue, and the average trajectory for BD patients in dark blue. These trajectories represent expected localized brain volume change rates over time, expressed in arbitrary units to visualize approximate trends. The average patient trajectory suggests varying outcomes for different BD patient groups. Those without an episode during the T1-T2 interval might initially show increased GMV if they had experienced manic episodes before baseline, followed by a more rapid decline over the two-year interval in periods of remission compared to HCs. Conversely, those with an episode during the interval started with lower GMV at baseline but may exhibit temporary GMV increases during the T1-T2 interval. Later during remission, brain changes are thought to align with the trajectories of HCs, suggesting a normalization of previous brain changes. Over time, GMV declines more across all BD patients compared to HCs, suggesting a potential long-term impact of episodes on brain structure. This figure is adapted from and expands upon concepts of Abé et al. [9]. †Indicates MRI values directly observed in our study.

In support of this dynamic pattern, cross-sectional MRI studies demonstrated GMV increases in the cerebellum in first-episode BD patients, while GMV decreases were observed in BD patients with a history of multiple episodes and longer illness durations [59,60,61,62,63,64]. Furthermore, longitudinal studies revealed that an increasing number of depressive episodes during the study interval correlated with progressive GMV increases in the cerebellum [20], whereas an increasing number of manic episodes correlated with GMV decreases in this area [21]. While we did not observe GMV decreases with an increasing number of manic episodes during the two-year interval, we found that a longer duration of manic episodes prior to baseline was associated with more pronounced GMV decreases during the two-year interval in the cerebellum in BD patients without recurrence. This finding suggests that mania, relative to depression, may be linked to longer-lasting and/or more severe maladaptive changes in cerebellar structure that even persist into periods of remission, possibly due to the pronounced neurophysiological disruptions associated with manic episodes (see Fig. 3) [9].

These maladaptive processes may particularly occur in an area like the cerebellum [65, 66], a region increasingly recognized for its plasticity [67], critical role in emotion regulation [68, 69], and involvement in affective disorders [70]. The cerebellum is closely linked to the basal ganglia and receives input from various cortical areas, including the prefrontal and temporal cortex, to facilitate automatic behaviors [71]. The exterior part of the cerebellum is particularly involved in emotional processes [72]. Alterations in this area could disrupt functional connectivity networks of cortico-cerebellar circuits, particularly with the prefrontal cortex [73,74,75], which may contribute to the emotion dysregulation often observed in BD patients [64, 71, 76].

The observed GMV reductions in BD patients without recurrence contrast some previous longitudinal studies that reported no gray matter changes during periods of remission [17,18,19]. Beyond the timing of the MRI acquisition and the relative phase of the disorder (as illustrated in Fig. 3), these discrepancies may be due to different methodological approaches and participant characteristics. First, Abé et al. [18] did not include a control group [18], whereas our study used a matched group of HCs by age and sex to BD patients, which serves as a comparative baseline of normal age-related brain structural changes, allowing for more sensitive detection of disorder-specific brain structural changes that might otherwise be obscured in patient-only samples. Second, Abé et al. [18, 19] used Freesurfer to assess cortical thickness within larger, predefined regions-of-interest (ROIs) [18, 19], while our study utilized voxel-based morphometry to evaluate whole-brain GMV changes, allowing for the detection of subcortical and cerebellar changes that surface-based and ROI-based approaches may overlook. Third, Abé et al. [18, 19] and Kozicky et al. [17] did not account for familial genetic risk, medication load, number and duration of hospitalizations both before baseline (T1) and during the two-year interval (T2-T1), nor did they consider changes in global functioning and symptom severity (depressive or manic) during the two-year (T2-T1) interval [17,18,19], which are all potential risk factors for BD that may exert brain changes observed also in BD patients, that our study accounted for [27]. Fourth, our BD non-recurrence group exhibited a more severe illness course with an average of 3.6 manic episodes prior to the study, compared to 2.8 in Abé et al. [18], possibly predisposing our individuals to neuroprogressive changes even in the absence of episode recurrence during the follow-up interval. Fifth, the follow-up interval of Abé et al. [18, 19] was on average six years compared to our two-year interval [18, 19], potentially missing short-term and dynamic brain structural changes in their study. Sixth, Kozicky et al. [17] focused on first-episode BD patients [17], while our study included first- and multiple-episode BD patients, potentially exerting more pronounced neuroprogressive changes that may increase the likelihood of detecting GMV changes. Seventh, our participant demographics differed with an older average age of 40.9 years compared to 22.9 in Kozicky et al. [17], and a lower percentage of females with 52.2% compared to 61% Abé et al. [18], influencing episode recurrence and neurobiological vulnerability [30, 31]. Lastly, lower rates of medication intake with 35% on lithium in our study versus 83% in Abé et al. [18], and 48% on antipsychotics versus 75% in Kozicky et al. [17], could have exerted neuroprotective or neurotoxic effects, respectively, to stabilize or worsen GMV changes, which may have contributed to the observed brain structural differences.

Our study carefully accounted for potential confounding factors, including medication effects, familial genetic risk, substance use, and hospitalization frequency [9, 38]. Neither lithium, which is known for its neurotrophic effects and often associated with GMV increases, nor antipsychotics, which may be linked to GMV decreases, significantly influenced the observed GMV changes in our BD patients. Furthermore, familial risk, which might predispose to and modulate brain structural changes, and comorbid substance use, particularly cannabis abuse, which is associated with brain abnormalities and longitudinal brain changes, did not impact our outcomes [9]. The number of hospitalizations, as an indicator of disease severity, also showed no effect on the observed GMV changes [38]. Instead, BD episodes likely drove the observed brain changes.

Some limitations should be noted. First, while the relatively small sample size within the two BD subgroups might have limited the ability to detect modest but significant effects, large cohorts of BD patients are rare and the present study is the second largest and best characterized longitudinal MRI studies of BD patients to date [3, 9]. Second, although BD episodes were self-reported, which could introduce recall bias, we employed the life chart method to improve the reliability of the self-reported measures [77, 78]. Third, our HC group included “very healthy” participants without subclinical symptoms or familial risk for BD, which may limit the generalizability of our findings; however, the inclusion of such HCs is crucial to detect small yet significant effects, as often observed in psychiatric MRI studies. Fourth, although we accounted for several confounders, including current and past disease severity, medication, genetic familial risk, and comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, other factors such as subclinical symptoms may have influenced our findings, precluding causal inferences. Lastly, although the lack of findings in our cross-sectional, between-group predictive and retrospective analyses suggest that episode recurrence likely drove the observed GMV changes, we cannot ultimately determine the directionality of the relationship between episode recurrence and GMV changes using two imaging time points.

Our findings provide insights into the neurobiological consequences of BD episodes on gray matter over a two-year follow-up interval. The observed brain structural increases may reflect mechanisms like neuroinflammation during acute phases of BD, whereas brain structural decreases may be linked to processes like abnormal synaptic refinement or pruning during periods of remission, possibly induced by neuroinflammation from previous BD episodes. These findings underscore the dynamic nature of brain changes in BD and highlight the need for a longitudinal, comprehensive approach to better understand the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the observed brain changes in psychiatric disorders. Future studies should elucidate these relationships in larger samples and at multiple assessment points using inflammatory markers.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (FTO) upon reasonable request. MATLAB (version R2017a) code was used to generate batches for whole-brain analyses within the SPM12/CAT12 toolbox and are available from the corresponding author (FTO) upon reasonable request.

References

Grande I, Berk M, Birmaher B, Vieta E. Bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2016;387:1561–72.

McCraw S, Parker G, Graham R, Synnott H, Mitchell PB. The duration of undiagnosed bipolar disorder: effect on outcomes and treatment response. J Affect Disord. 2014;168:422–9.

Förster K, Horstmann RH, Dannlowski U, Houenou J, Kanske P. Progressive grey matter alterations in bipolar disorder across the life span – a systematic review. Bipolar Disord. 2023;25:443–56.

Chen G, Wang J, Gong J, Qi Z, Fu S, Tang G, et al. Functional and structural brain differences in bipolar disorder: a multimodal meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Psychol Med. 2022;52:2861–73.

Gong J, Wang J, Chen P, Qi Z, Luo Z, Wang J, et al. Large-scale network abnormality in bipolar disorder: a multimodal meta-analysis of resting-state functional and structural magnetic resonance imaging studies. J Affect Disord. 2021;292:9–20.

Lu X, Zhong Y, Ma Z, Wu Y, Fox PT, Zhang N, et al. Structural imaging biomarkers for bipolar disorder: meta-analyses of whole-brain voxel-based morphometry studies. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36:353–64.

Yu H, Meng Y, Li X, Zhang C, Liang S, Li M, et al. Common and distinct patterns of grey matter alterations in borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder: voxel-based meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;215:395–403.

Cahn AJ, Keramatian K, Frysch C, Yatham LN, Chakrabarty T. Longitudinal grey matter changes following first episode mania in bipolar I disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2021;291:198–208.

Abé C, Liberg B, Klahn AL, Petrovic P, Landén M. Mania-related effects on structural brain changes in bipolar disorder – a narrative review of the evidence. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28:2674–82.

Delaloye C, Moy G, de Bilbao F, Weber K, Baudois S, Haller S, et al. Longitudinal analysis of cognitive performances and structural brain changes in late‐life bipolar disorder. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:1309–18.

Serafini G, Pardini M, Monacelli F, Orso B, Girtler N, Brugnolo A, et al. Neuroprogression as an illness trajectory in bipolar disorder: a selective review of the current literature. Brain Sci. 2021;11:276.

Pereira AC, Oliveira J, Silva S, Madeira N, Pereira CMF, Cruz MT. Inflammation in bipolar disorder (BD): identification of new therapeutic targets. Pharm Res. 2021;163:105325.

Sayana P, Colpo GD, Simões LR, Giridharan VV, Teixeira AL, Quevedo J, et al. A systematic review of evidence for the role of inflammatory biomarkers in bipolar patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;92:160–82.

Saccaro LF, Crokaert J, Perroud N, Piguet C. Structural and functional MRI correlates of inflammation in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2023;325:83–92.

Long J-Y, Li B, Ding P, Mei H, Li Y. Correlations between multimodal neuroimaging and peripheral inflammation in different subtypes and mood states of bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2024;12:5.

Doney E, Cadoret A, Dion-Albert L, Lebel M, Menard C. Inflammation-driven brain and gut barrier dysfunction in stress and mood disorders. Eur J Neurosci. 2022;55:2851–94.

Kozicky J, McGirr A, Bond DJ, Gonzalez M, Silveira LE, Keramatian K, et al. Neuroprogression and episode recurrence in bipolar I disorder: a study of gray matter volume changes in first‐episode mania and association with clinical outcome. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18:511–9.

Abé C, Ekman C-J, Sellgren C, Petrovic P, Ingvar M, Landén M. Manic episodes are related to changes in frontal cortex: a longitudinal neuroimaging study of bipolar disorder 1. Brain. 2015;138:3440–8.

Abé C, Liberg B, Song J, Bergen SE, Petrovic P, Ekman CJ, et al. Longitudinal cortical thickness changes in bipolar disorder and the relationship to genetic risk, mania, and lithium use. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;87:271–81.

Lisy ME, Jarvis KB, DelBello MP, Mills NP, Weber WA, Fleck D, et al. Progressive neurostructural changes in adolescent and adult patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13:396–405.

Moorhead TWJ, McKirdy J, Sussmann JED, Hall J, Lawrie SM, Johnstone EC, et al. Progressive gray matter loss in patients with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:894–900.

Zak N, Bøen E, Boye B, Andreassen OA, Doan NT, Malt UF, et al. Mood episodes are associated with increased cortical thinning: a longitudinal study of bipolar disorder type II. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21:525–38.

Kircher T, Wöhr M, Nenadic I, Schwarting R, Schratt G, Alferink J, et al. Neurobiology of the major psychoses: a translational perspective on brain structure and function—the FOR2107 consortium. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;269:949–62.

Thiel K, Lemke H, Winter A, Flinkenflügel K, Waltemate L, Bonnekoh L, et al. White and gray matter alterations in bipolar I and bipolar II disorder subtypes compared with healthy controls – exploring associations with disease course and polygenic risk. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2024;49:814–23.

Thiel K, Meinert S, Winter A, Lemke H, Waltemate L, Breuer F, et al. Reduced fractional anisotropy in bipolar disorder major depressive disorder independent of current symptoms. Psychol Med. 2023;53:4592–602.

Brosch K, Stein F, Schmitt S, Pfarr J-K, Ringwald KG, Thomas-Odenthal F, et al. Reduced hippocampal gray matter volume is a common feature of patients with major depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:4234–43.

Thomas-Odenthal F, Stein F, Vogelbacher C, Alexander N, Bechdolf A, Bermpohl F, et al. Larger putamen in individuals at risk and with manifest bipolar disorder. Psychol Med. 2024:54:3071–81.

Wittchen H-U, Wunderlich U, Gruschwitz S, Zaudig M. SKID I. Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM-IV. Achse I: Psychische Störungen. Interviewheft und Beurteilungsheft. Eine deutschsprachige, erweiterte Bearbeitung der amerikanischen Originalversion des SKID I. Hogrefe; 1997.

Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J Stat Softw. 2011;42:1–28.

Taki Y, Kinomura S, Sato K, Goto R, Kawashima R, Fukuda H. A longitudinal study of gray matter volume decline with age and modifying factors. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:907–15.

Wang X, Tian F, Wang S, Cheng B, Qiu L, He M, et al. Gray matter bases of psychotic features in adult bipolar disorder: a systematic review and voxel‐based meta‐analysis of neuroimaging studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39:4707–23.

Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62.

Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–35.

Hall RCW. Global assessment of functioning: a modified scale. Psychosomatics. 1995;36:267–75.

Vogelbacher C, Möbius TWD, Sommer J, Schuster V, Dannlowski U, Kircher T, et al. The Marburg-Münster Affective Disorders Cohort Study (MACS): a quality assurance protocol for MR neuroimaging data. Neuroimage. 2018;172:450–60.

The jamovi project. Jamovi (Version 2.3.28) [Computer Software]. 2024. Available from: https://www.jamovi.org.

Thomas-Odenthal F, Ringwald K, Teutenberg L, Stein F, Alexander N, Bonnekoh LM, et al. Neural foundation of the diathesis-stress model: longitudinal gray matter volume changes in response to stressful life events in major depressive disorder and healthy controls. Mol Psychiatry. 2024;29:2724–32.

Förster K, Grotegerd D, Dohm K, Lemke H, Enneking V, Meinert S, et al. Association of hospitalization with structural brain alterations in patients with affective disorders over nine years. Transl Psychiatry. 2023;13:170.

McWhinney SR, Hlinka J, Bakstein E, Dietze LMF, Corkum ELV, Abé C, et al. Principal component analysis as an efficient method for capturing multivariate brain signatures of complex disorders-ENIGMA study in people with bipolar disorders and obesity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2024;45:e26682.

Hassel S, Almeida JR, Kerr N, Nau S, Ladouceur CD, Fissell K, et al. Elevated striatal and decreased dorsolateral prefrontal cortical activity in response to emotional stimuli in euthymic bipolar disorder: no associations with psychotropic medication load. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:916–27.

Flinkenflügel K, Meinert S, Hirtsiefer C, Grotegerd D, Gruber M, Goltermann J, et al. Associations between white matter microstructure and cognitive decline in major depressive disorder versus controls in Germany: a prospective case-control cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2024;11:899–909.

Leucht S, Samara M, Heres S, Davis JM. Dose equivalents for antipsychotic drugs: the DDD method: Table 1. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:S90–S94.

Sackeim HA. The definition and meaning of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:10–17.

Quidé Y, Bortolasci CC, Spolding B, Kidnapillai S, Watkeys OJ, Cohen-Woods S, et al. Systemic inflammation and grey matter volume in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: moderation by childhood trauma severity. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;105:110013.

Lizano P, Lutz O, Xu Y, Rubin LH, Paskowitz L, Lee AM, et al. Multivariate relationships between peripheral inflammatory marker subtypes and cognitive and brain structural measures in psychosis. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:3430–43.

Cathomas F, Holt LM, Parise EM, Liu J, Murrough JW, Casaccia P, et al. Beyond the neuron: role of non-neuronal cells in stress disorders. Neuron. 2022;110:1116–38.

Gritti D, Delvecchio G, Ferro A, Bressi C, Brambilla P. Neuroinflammation in major depressive disorder: a review of PET imaging studies examining the 18-kDa translocator protein. J Affect Disord. 2021;292:642–51.

Pasternak O, Kubicki M, Shenton ME. In vivo imaging of neuroinflammation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;173:200–12.

Femminella GD, Dani M, Wood M, Fan Z, Calsolaro V, Atkinson R, et al. Microglial activation in early Alzheimer trajectory is associated with higher gray matter volume. Neurology. 2019;92:e1331–e1343.

Uhlig M, Reinelt JD, Lauckner ME, Kumral D, Schaare HL, Mildner T, et al. Rapid volumetric brain changes after acute psychosocial stress. Neuroimage. 2023;265:119760.

Setiawan E, Wilson AA, Mizrahi R, Rusjan PM, Miler L, Rajkowska G, et al. Role of translocator protein density, a marker of neuroinflammation, in the brain during major depressive episodes. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:268.

Chaves‐Filho A, Eyres C, Blöbaum L, Landwehr A, Tremblay M. The emerging neuroimmune hypothesis of bipolar disorder: an updated overview of neuroimmune and microglial findings. J Neurochem. 2024;168:1780–816.

Li B, Yang W, Ge T, Wang Y, Cui R. Stress induced microglial activation contributes to depression. Pharm Res. 2022;179:106145.

Deng S, Chen J, Wang F. Microglia: a central player in depression. Curr Med Sci. 2020;40:391–400.

Ren F, Guo R. Synaptic microenvironment in depressive disorder: insights from synaptic plasticity. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:157–65.

Asan L, Falfán-Melgoza C, Beretta CA, Sack M, Zheng L, Weber-Fahr W, et al. Cellular correlates of gray matter volume changes in magnetic resonance morphometry identified by two-photon microscopy. Sci Rep. 2021;11:4234.

Green C, Shen X, Stevenson AJ, Conole ELS, Harris MA, Barbu MC, et al. Structural brain correlates of serum and epigenetic markers of inflammation in major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;92:39–48.

Berk M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza AC, Dean OM, Giorlando F, Maes M, et al. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:804–17.

Mills NP, DelBello MP, Adler CM, Strakowski SM. MRI analysis of cerebellar vermal abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1530–3.

DelBello MP, Strakowski SM, Zimmerman ME, Hawkins JM, Sax KW. MRI analysis of the cerebellum in bipolar disorder: a pilot study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:63–68.

Kim D, Byul Cho H, Dager SR, Yurgelun-Todd DA, Yoon S, Lee JH, et al. Posterior cerebellar vermal deficits in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:499–506.

Monkul ES, Hatch JP, Sassi RB, Axelson D, Brambilla P, Nicoletti MA, et al. MRI study of the cerebellum in young bipolar patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:613–9.

Adler CM, DelBello MP, Jarvis K, Levine A, Adams J, Strakowski SM. Voxel-based study of structural changes in first-episode patients with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:776–81.

Long J, Qin K, Wu Y, Li L, Zhou J. Gray matter abnormalities and associated familial risk endophenotype in individuals with first-episode bipolar disorder: evidence from whole-brain voxel-wise meta-analysis. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;74:103179.

Fatemi SH, Laurence JA, Araghi-Niknam M, Stary JM, Schulz SC, Lee S, et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein is reduced in cerebellum of subjects with major depression, but not schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;69:317–23.

Gruol DL. The neuroimmune system and the cerebellum. Cerebellum. 2023;23:2511–37.

D’Angelo E, Mapelli L, Casellato C, Garrido JA, Luque N, Monaco J, et al. Distributed circuit plasticity: new clues for the cerebellar mechanisms of learning. Cerebellum. 2016;15:139–51.

Baumann O, Mattingley JB. Cerebellum and emotion processing. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2022;1378:25–39.

Adamaszek M, D’Agata F, Ferrucci R, Habas C, Keulen S, Kirkby KC, et al. Consensus paper: cerebellum and emotion. Cerebellum. 2016;16:552–76.

Lupo M, Siciliano L, Leggio M. From cerebellar alterations to mood disorders: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;103:21–28.

Arleo A, Bareš M, Bernard JA, Bogoian HR, Bruchhage MMK, Bryant P, et al. Consensus paper: cerebellum and ageing. Cerebellum. 2023;23:802–32.

Pierce JE, Thomasson M, Voruz P, Selosse G, Péron J. Explicit and implicit emotion processing in the cerebellum: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Cerebellum. 2022;22:852–64.

Chen G, Zhao L, Jia Y, Zhong S, Chen F, Luo X, et al. Abnormal cerebellum-DMN regions connectivity in unmedicated bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:441–7.

Bostan AC, Dum RP, Strick PL. Cerebellar networks with the cerebral cortex and basal ganglia. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17:241–54.

Li H, Liu H, Tang Y, Yan R, Jiang X, Fan G, et al. Decreased functional connectivity of vermis-ventral prefrontal cortex in bipolar disorder. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021;15:711688.

Morimoto C, Uematsu A, Nakatani H, Takano Y, Iwashiro N, Abe O, et al. Volumetric differences in gray and white matter of cerebellar Crus I/II across the different clinical stages of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;75:256–64.

Schärer LO, Krienke UJ, Graf S-M, Meltzer K, Langosch JM. Validation of life-charts documented with the personal life-chart app – a self-monitoring tool for bipolar disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:49.

Denicoff KD, Leverich GS, Nolen WA, Rush AJ, McElroy SL, Keck PE, et al. Validation of the prospective NIMH-Life-Chart Method (NIMH-LCM-p) for longitudinal assessment of bipolar illness. Psychol Med. 2000;30:1391–7.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere gratitude goes to all the study participants and staff. Acknowledgments and consortium members by Work Package (WP) are detailed at https://for2107.de/acknowledgements/. Special thanks to Iryna Kondratiuk, Rebecca Cramer, Ammar Alkasm, and Svenja Dabringhausen (Department of Psychiatry, Philipps-University Marburg) for their exceptional support in data collection, and to Marc Molendijk for his ongoing inspiration.

Funding

This work is part of the German multi-center consortium “Neurobiology of Affective Disorders. A translational perspective on brain structure and function“, funded by the German Research Foundation (Research Unit FOR2107); the principal investigators are Tilo Kircher (speaker FOR2107; KI588/14-1, KI588/14-2, KI588/20-1, KI588/22-1), Udo Dannlowski (co-speaker FOR2107; DA1151/5-1, DA1151/5-2, DA1151/9-1, DA1151/10-1, DA1151/11-1), Igor Nenadić (NE2254/1-2, NE2254/2-1, NE2254/3-1, NE2254/4-1), Axel Krug (KR3822/5-1, KR3822/7-2), Andreas Jansen (JA1890/7-1, JA1890/7-2), Petra Pfefferle (PF 784/1-1, PF 784/1-2), Harald Renz (RE737/20-1, RE737/20-2), Tim Hahn (HA7070/2-2), Carsten Konrad (KO 4291/3-1), and Benjamin Straube (STR1146/18-1). This study was further supported by the German Research foundation (grant SFB/TRR 393, project grant no 521379614), and the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research (IZKF) of the medical faculty of Münster (grant Dan3/022/22 to UD). This study was partially supported by grants from UKGM and Forschungscampus Mittelhessen, awarded to Igor Nenadić. Additional financial backing was provided by the “Innovative Medizinische Forschung” of the medical faculty of the University of Münster, credited to Susanne Meinert (ME122205) and to Janik Goltermann (GO122301). Tilo Kircher, Nina Alexander, Benjamin Straube, and Igor Nenadić were further supported by the DYNAMIC center, which was funded by the LOEWE program of the Hessian Ministry of Science and Arts (Grant Number: LOEWE 1/16/519/03/09.001(0009)/98). Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contribution to conception and design: FTO, LT, FS, TK. Acquisition of the data: FTO, LT, FS, NA, LB, KB, KF, JG, DG, TH, AJ, EJL, SM, JP, HR, KR, NS, TS, BS, KT, PU, AK, IN, UD, TK. Analysis and interpretation of data: FTO, LT, FS, IN, TK. Drafting the article: FTO. Revising it critically for important intellectual content: LT, FS, NA, LB, KB, KF, JG, DG, TH, AJ, EJL, SM, JP, HR, KR, NS, TS, BS, KT, PU, AK, IN, UD, TK. All authors contributed to the article and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

TK received unrestricted educational grants from Servier, Janssen, Recordati, Aristo, Otsuka, and neuraxpharm. This funding is not associated with the current work. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas-Odenthal, F., Teutenberg, L., Stein, F. et al. Differential impact of manic versus depressive episode recurrence on longitudinal gray matter volume changes in bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol. 51, 703–711 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-025-02197-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-025-02197-x